Abstract

Hospital ownership of physician practices has grown across the US, and these strategic decisions seem to drive higher prices and spending. Using detailed physician ownership information and a universe of Florida discharge records, we show novel evidence of hospital-physician integration foreclosure effects within outpatient procedure markets. Following hospital acquisition, physicians shift nearly 10% of their Medicare and commercially insured cases away from ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) to hospitals and are up to 18% less likely to use an ASC at all. Altering physician choices over treatment setting can be in conflict with patient and payer cost, convenience, and quality preferences.

Keywords: physician, vertical integration, health care competition, ambulatory surgery center, hospital outpatient department

JEL: I11, I18, L44

1. Introduction

A long-running trend affecting hospitals is the shift from inpatient to outpatient sites of care. This shift more frequently allows patients to avoid a multiple day hospital course and instead receive a same-day discharge following their care. According to recent and national figures from the American Hospital Association, hospitals’ aggregate annual revenue of nearly $1 trillion is now almost evenly split between inpatient and outpatient hospital services (Bannow 2019). The momentum away from inpatient-delivered care has implications for a wide variety of hospitals’ clinical business lines but has been especially pronounced for surgical procedures, which also account for roughly a third of all US health care expenditures (Muñoz, Muñoz, and Wise 2010). Outpatient delivery for surgery increasingly substituted for inpatient options starting in the early 1980s and has culminated in the majority of all hospital cases performed on an outpatient basis at this time.1

Hospitals, however, are not solely responsible for the redirection toward outpatient settings for surgical as well as other types of procedural care, such as colonoscopies, endoscopies, and therapeutic injections. While inpatient care is limited to intra-industry competition (i.e., hospital-versus-hospital), outpatient procedures have rival industries competing for the same cases—namely, hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and free-standing ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). ASCs are smaller and more specialized firms, in comparison to hospitals, and typically include direct ownership stakes by physicians. ASCs also try to differentiate themselves from competing hospitals by offering greater convenience and lower price points, which is widely believed to benefit commercially and publicly insured health care consumers (Paquette et al. 2008; Grisel et al. 2009; Hair, Hussey, and Wynn 2012; Munnich and Parente 2014; Weber, 2014; Munnich and Parente 2018; Aouad, Brown, and Whaley 2019; Sood and Whaley 2019).

There are currently more than 5,000 ASCs in the US, and within the Medicare market alone, more than 6 million outpatient services have been annually performed in ASCs during recent years. In 2017, specifically, ASC facilities captured $4.6 billion in total Medicare payments, and the rate of growth in ASC Medicare case volumes outpaced HOPDs for the first time (MedPAC 2019). Unsurprisingly, hospitals are known to suffer weaker consumer demand and profitability when facing greater ASC competition (Bian and Morrisey 2007; Courtemanche and Plotzke 2010; Carey, Burgess, and Young 2011), and recent work demonstrates that hospitals may be forced to reduce their service prices in markets experiencing increased patient demand for ASCs (Whaley and Brown 2018). These previous empirical findings, along with some industry perceptions, imply that market forces have at least partially disciplined hospitals through the threat and experience of losing profitable cases to ASCs. However, hospitals’ responses to business stealing by ASCs are not necessarily confined to consumer welfare promoting actions (e.g., offering more outpatient services, increasing quality, and/or accepting smaller markups). Instead, hospitals may seek to relax the degree of competition between these otherwise rival firms.

One plausible mechanism to do so is through regulation, such as Certificate of Need (CON) legislation, which can restrain the expansion of incumbent ASCs and/or erect barriers to entry for new ones (Hollenbeck et al. 2014; Whaley 2018). However, lobbying for favorable (i.e., anticompetitive) state laws is costly, with uncertain time horizons and outcomes. Moreover, the likelihood of a slow policymaking process, even for advantageous changes, makes regulatory intervention a challenging and perhaps unprofitable strategic response for hospitals concerned with increasing ASC competition.

An alternative approach with potentially more immediate impact is simply to purchase the upstream supplier that both HOPDs and ASCs rely upon: physicians. Unlike many other markets where firms sell directly to consumers, patients access HOPDs and ASCs through physicians. Thus, HOPDs and ASCs need to attract physicians and their accompanying procedural cases in order to receive the facility component of payment attached to a given case. Physicians, on the other hand, face equivalent reimbursements when performing a surgery or procedure in either setting. Hospitals can either engage in costly effort to match ASCs in terms of physician-patient amenity and convenience offerings, or instead, make a lump-sum purchase in order to exercise more control over where the acquired physician’s cases are performed. In other words, the ability of hospitals to vertically integrate with physicians creates a strategic opportunity to deny cases to competing ASCs and reallocate those cases to the owning hospitals’ HOPDs. Doing so avoids direct horizontal competition between hospitals and ASCs and is similar to “exclusive dealing” actions studied outside of health care markets (e.g., see Bernheim and Whinston 1998).2

Vertical integration between hospitals and physicians is of course not restricted to surgical care and has been on the rise in health care markets across the US (Gaynor, Ho, and Town 2015; Nikpay, Richards, and Penson 2018; Post, Buchmueller, and Ryan 2018). Currently, over a third of all US physicians are employed by a hospital or work within a practice owned by a hospital or health system—an increase of 5 percentage points since 2012.3 Existing research indicates that this form of vertical integration is associated with higher care utilization, service prices, medical spending, and insurance premiums—with little evidence of efficiency or quality gains (Baker, Bundorf, and Kessler 2014; Carlin, Dowd, and Feldman 2015; Neprash et al. 2015; Koch, Wendling, and Wilson 2017; Capps, Dranove, and Ody 2018; Koch, Wendling, and Wilson 2018; Post et al. 2018; Scheffler, Arnold, and Whaley 2018; Jung, Feldman, and Kalidindi 2019; Noel Short and Ho 2019). While these studies are documenting important and policy-relevant outcomes, foreclosure effects have received comparatively less empirical attention to date.

Previous economics research remarks that vertical integration broadly (Hart et al. 1990; Ordover, Saloner, and Salop 1990; Rasmusen, Ramseyer, and Wiley 1991; Segal and Whinston 2000) and as applied to hospital-physician alignment narrowly (Gaynor and Vogt 2000; Gaynor et al. 2015; Post et al. 2018), has the potential to exclude competitors from the market. Yet, we are aware of only three published studies that explicitly examine the role of vertical integration on physicians’ choice of care setting. Baker, Bundorf, and Kessler (2016) use discrete choice estimation to show that physicians are much more likely to admit a given patient to their acquiring hospital and that these same hospitals tend to be higher cost, less convenient, and lower quality than nearby options—suggesting negative consumer welfare effects. Carlin, Feldman, and Dowd (2016) similarly find patients to be redirected toward acquiring hospitals for inpatient admissions and hospital-owned imaging facilities following three multispecialty physician practices being vertically integrated with two health systems in the Twin Cities Minnesota market. And finally, Koch et al. (2017) also observe some declines in physician inpatient claims in competing (non-owning) hospitals post-vertical integration for the 27 practices involved in their study; however, the predominant effect that the authors document is the redistribution of physician office-based claims to hospital outpatient-based care, rather than inpatient hospital switching. Each of these three studies raise key issues for regulatory and payment policy debates, especially as they pertain to hospital-to-hospital competition, but none of them speak to anticompetitive effects across industries where hospitals have private incentives to foreclose non-hospital rivals (e.g., ASCs).

In this paper, we investigate the presence and extent of anticompetitive effects from hospital acquisitions of physician practices in contested outpatient procedure markets. Using detailed physician practice ownership information from 2009–2015 linked to the universe of outpatient discharge records in Florida over this same period, we employ difference-in-differences (DD) and event study estimation to quantify how physicians’ treatment setting choices and related outcomes respond to being newly acquired by a local hospital or health system.

We find that physicians consistently integrated with hospitals are 65% less likely to use an ASC at all when compared to physicians that are never vertically integrated over our study period. Physicians that experience a hospital or health system acquisition within our analytic sample reduce the number of ASCs they rely upon by 13% and are 9% less likely to perform any procedures within an ASC. The negative ASC extensive margin effect we observe also grows over time, with an approximately 18% reduction four years out from the acquisition event. Consequently, physicians’ share of Medicare and commercially insured outpatient procedures taking place within ASCs falls abruptly by 8–9% once they are vertically integrated with a hospital. Although hospitals do not induce acquired physicians to perform more cases or more procedures per case, these physicians report charging considerably more for their outpatient services—approximately 29% over their baseline levels by the end of our study period. The increase in reported total charges is also most pronounced for traditional Medicare (i.e., fee-for-service) cases. There is little evidence that competing hospitals experience business stealing following a hospital’s acquisition of a physician practice; instead, the foreclosure effects appear concentrated on the non-hospital rival industry.

Taken together, our findings offer a novel insight that augments the growing literature on the economic consequences of vertical integration between hospitals and physician practices. They also suggest risks of incentive misalignment between physicians and patients following the acquisition event. Vertical integration appears to distort physicians’ treatment setting choices by favoring HOPDs over ASCs, which may be in conflict with patient and payer preferences over cost, convenience, and quality dimensions. Subsequent weakening of competition can also negatively affect allocative efficiency in these markets. Antitrust authorities should bear in mind that hospitals’ strategic merger and acquisition (M&A) behavior can negatively impact firms outside of the hospital industry. These more diffuse market ramifications should therefore be a part of any regulatory scrutiny attached to a proposed hospital acquisition of a physician practice or group.

2. Vertical integration in outpatient procedure markets

There are a variety of strategic benefits from vertical alignment between hospitals and physicians that have been proposed and investigated in the literature, including bargaining advantages with commercial insurers (Gal-Or 1999; Cuellar and Gertler 2006; Peters 2014; McCarthy and Huang 2018) and exploiting profitable site of care classification rules (e.g., see Koch et al. 2017; Capps et al. 2018; Dranove and Ody 2019).4 As previously noted, with respect to outpatient procedure markets, hospitals can have an additional motivation in the form of alleviating competitive pressure from ASCs.

Over 90% of ASCs are estimated to have some form of physician ownership (Dyrda 2017). Reimbursement for a give outpatient procedure largely consists of two separate payments: a physician-specific payment for her effort and a facility-specific payment to cover supporting infrastructure and personnel. An ownership stake therefore makes a physician the residual claimant on a share of profits from all services performed within the ASC via the collected facility revenues. Moreover, ASC ownership financially rewards a physician’s clinical effort more than in the non-owner state because, in the absence of an ownership share, she would not receive income from the facility fee component belonging to her personally performed procedures.5 Empirical evidence suggests that physicians’ choices over treatment settings is at least partially linked to personal financial interests and case profitability (Lynk and Longley 2002; David and Neuman 2011; Plotzke and Courtemanche 2011; Munnich et al. 2020). Hospitals relatedly argue that ASCs limit their services to those that are highly profitable, while hospitals must offer both profitable and unprofitable (but socially beneficial) care (Casalino, Devers, Brewster 2003; Voelker 2003; Vogt and Romley 2009). Because of the high-powered incentives for ASC-use facing physicians and the perceived threats to financial performance facing hospitals, hospitals tend to resent the ASC industry and support efforts to restrain its expansion.

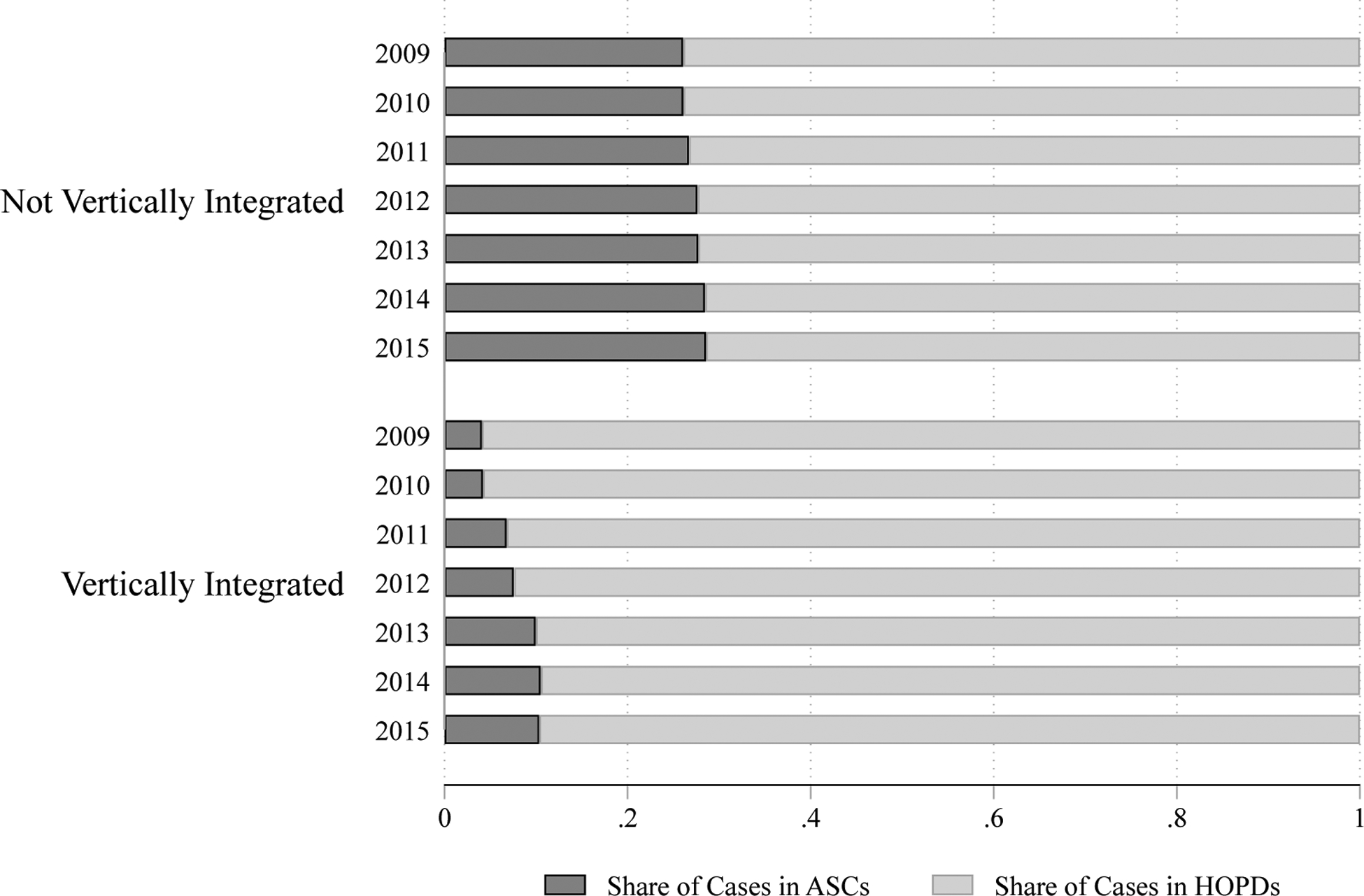

One way for hospitals to directly exercise greater control over the market is to vertically integrate with upstream physicians in order to foreclose ASC rivals (as remarked in Section 1). Since firms from both industries rely on physician referrals (i.e., physicians bringing their surgical and other procedural cases to the facility), this strategic action is a way for hospitals to blunt any business stealing effects by ASCs as well as raise costs for their ASC competitors. We can see prima facie evidence of such behavior in Figure 1 (using our analytic data fully described in Section 3). While roughly a third of all outpatient procedures (all payers) are performed within an ASC in a given year (2009–2015) among non-integrated physicians, only about 5–10% take place within an ASC among physicians that are vertically integrated with hospitals and health systems. Of course, cross-sectional differences could be explained by other factors (e.g., geographic and patient population differences across physician organizational structures), so within-physician variation in vertical integration status is necessary for causal interpretations (detailed in Section 4).

Figure 1:

Treatment Setting Balance by Physician-Hospital Integration Status, All Payers 2009–2015

Notes: Analytic data are from the universe of outpatient procedure discharge records in Florida. “HOPDs” are hospital outpatient departments. “ASCs” are ambulatory surgery centers.

Once relevant physicians have been acquired by a local hospital, affected ASCs may need to generate new business to offset the resulting case losses. Doing so could require a given ASC to invest more in amenities, technology, or other physical capital to attract new (non-owner) physicians to the facility. Separately (or perhaps in conjunction), the ASC may need to offer more generous ownership opportunities to prospective physicians—and thereby redistribute future incomes from existing owners—in order to better align the physicians’ financial interests with its own. For either response type, the ASC would be forced to bear additional costs to target previously inframarginal physicians, which could then diminish some of the (lower) operational cost advantages ASCs tend to enjoy vis-à-vis hospitals. Importantly, hospital-physician integration not only affects incumbent ASCs in contested markets, but it can also serve as an entry deterrent for new ASCs, which further erodes the risk of future case losses for the integrating hospital. And, in the extreme, if ASC competition is eventually foreclosed completely (i.e., incumbents exit and entry ceases), the integrating hospital can benefit from a captive upstream supplier without having to make further acquisitions—i.e., physicians will have no choice but to opt for HOPD delivery.6

It is unclear that such outpatient procedure market dynamics would be social welfare enhancing, and in fact, the opposite could prove true. For procedures common to both treatment settings (i.e., HOPDs and ASCs), there is the possibility of excluding a more efficient rival and redirecting the marginal case to the higher cost option, without commensurate quality gains or other consumer benefits. For these reasons, we argue that hospitals have strong private incentives to limit ASC-delivered care through vertical integration with physicians; however, quantifying the existence and degree of any anticompetitive integration effects in these markets ultimately requires new empirical investigation.

3. Data

3.1. Vertical integration status for physicians

Our first source of data is from the SK&A database.7 SK&A is a commercial research firm that conducts an annual phone survey of physician offices across the US. The survey approximates a near-universe of (office-based) physician practices and collects detailed information on practice size, individual physicians working within the practice (including their associated National Provider Identification (NPI) number), specialization, and crucially, the ownership structure pertaining to the practice. Specifically, the database documents if a practice is independently owned, part of a larger physician group (i.e., horizontally integrated), or owned by a hospital or health system (i.e., vertically integrated). A variety of recent studies have also relied on SK&A data resources for examining the effects of vertical alignment between hospitals and physicians (e.g., see Baker, Bundorf, and Kessler 2016; Richards, Nikpay, and Graves 2016; Koch et al. 2017, 2018; Nikpay, Richards, and Penson 2018).

3.2. Encounter data for outpatient procedures

Our encounter-level data encompass the universe of outpatient (ambulatory) procedure discharge records from the state of Florida, which we obtained from the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA). We use the administrative data over a relatively long time series, starting in the first quarter of 2009 and ending in the fourth quarter of 2015. Unlike many other data resources, the data also capture all payers in Florida markets over this seven-year period. The detailed records include a rich set of variables, such as diagnosis and procedure codes, type of insurance, patient demographic information, the specific facility (e.g., ASC versus HOPD) where the procedure was performed, and provider charges for the care belonging to a given case.

For our primary analyses, we use the discharge records to examine physician-level changes in treatment setting choices as well as treatment behavior following integration with a hospital or health system. The former focuses on the use of ASC facilities (along extensive and intensive margins) and captures our foreclosure effect of interest. The latter investigates total outpatient procedure output, number of procedures performed per encounter, and total charges for outpatient procedural care. We view the aggregate procedure output and number of procedures per case outcomes as measuring any changes in physicians’ treatment intensity after being vertically integrated. We consider charges as a potential (though limited) proxy for changes in billing behavior—consistent with shifting care to higher cost (HOPD) settings post-integration. At times, we also explicitly restrict to the traditional (i.e., fee-for-service) Medicare discharge records or the commercially insured (i.e., non-Medicare, private coverage) discharge records to estimate payer-specific changes in ASC allocations and charges for the supplied outpatient services. Nationally, more than 80% of ambulatory (outpatient) surgeries are estimated to have either commercial insurance or Medicare as the main payer (Hall et al. 2017).

Although the data are from a single state, Florida is home to a large share of the nation’s Medicare population (3–4 million beneficiaries in recent years), which is second only to California in terms of size.8 Florida also has an accommodating regulatory environment toward ASCs (e.g., ASCs are not bound by any existing certificate of need laws), and in terms of ASCs per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, Florida falls in the middle of the distribution—ranking 24th in the country (MedPAC 2019). These contextual features are helpful when considering the generalizability of our Florida-specific findings and additionally suggest that Florida markets can be worthy of independent investigation due to its Medicare spending relevance and accompanying implications for federal fiscal outlays.

4. Empirical strategy

Our analytic approach is the standard two-way fixed effects difference-in-differences (DD) research design. We begin by constructing a balanced panel of Florida physicians (2009–2015) from the SK&A data. We then use the practice ownership information to classify a given physician as never vertically integrated, always vertically integrated, or newly vertically integrated—including the exact year of integration—based on the reported ownership of the practice in each year of data.9 To ensure that we observe sufficient pre- and post-integration years for the newly integrating physicians, we also exclude those who vertically integrate in 2010, 2014, or 2015 from the analytic sample since integration events occurring during these years would have limited pre-period or post-period data to contribute to the analyses. We next combine the resulting physician-year ownership panels with the Florida discharge records after creating an analogous physician-year panel for aggregate outpatient procedure activity.10 Balancing the dataset in this manner results in 5,329 unique physicians who each performed roughly 200 outpatient procedure cases per year, on average, for our main estimation. The DD specification with two-way fixed effects is as follows:

| (1) |

Equation (1) has a full vector of physician (θ) and year (λ) fixed effects. The (δ) parameter is our DD estimate of interest and is identified by physicians newly acquired by a hospital during our study period. Our primary outcome variables (Yit) include any ASC use in a given year (i.e., the ASC extensive margin), the number of unique ASCs used per year, total outpatient procedure cases per year, average number of procedures performed per outpatient case per year, summed total reported charges for all cases per year, share of Medicare (commercial) cases performed within ASCs per year, and total reported charges for Medicare (commercial) patients per year.

The main underlying assumption for the DD research design is parallel trends across the treatment and control groups prior to the arrival of treatment. For our specific DD design to be valid, we need the physicians with stable integration status from 2009–2015 (i.e., the aforementioned ‘never’ and ‘always’ groups) to serve as sufficient counterfactuals for the behavior of physicians that are acquired by a hospital or health system during our study period. While this assumption is not directly testable, patterns in the outcomes during the years leading up to the vertical integration event can lend support to this identifying assumption, particularly if they demonstrate no differential changes prior to vertical integration for those who will eventually be acquired by a hospital or health system. We consequently leverage our precise timing of integration changes for a given physician to formally test for differential behavior changes among the treated physicians during the lead up to the vertical integration event—consistent with related research in this area (e.g., Baker et al. 2016; Koch et al. 2017; Capps et al. 2018) as well as broader health economics literatures relying on DD designs. We accomplish this by adapting our DD design to an event study framework in order to add credence to our DD estimates and inferences from the simpler two-way fixed effects model in Equation (1).

The event study specification takes the form:

| (2) |

Equation (2) maintains the two-way fixed effects (θ and λ) from Equation (1); however, we now allow the effect of hospital-physician integration to differ over one-year time intervals. The variable VI in Equation (2) is physician-specific and captures the year the physician becomes vertically integrated during our analytic period. A series of binary event-time variables are then constructed based on the difference between the specific year (t) and the value of VI for a given physician in the treatment group.11 The range of event-time indicator variables is [–4, 4] and reflects all possible pre- and post-integration time periods relevant to a given physician within our treatment group.12 Our omitted (or reference) time point is two years prior to a given physician becoming newly integrated with a hospital or health system (i.e., when t – VIi = −2, or put differently, when j = −2). The α parameters in Equation (2) provide our formal tests for parallel trends prior to the integration event. Coefficients that are statistically indistinguishable from zero are consistent with the parallel trends requirement being satisfied. The δ parameters flexibly allow for integration effects in each individual year from the year of integration (j = 0) up to four years following the integration event (j = 4). In other words, these estimates deconstruct the summary DD coefficient (which averages over the full post-period) into its constituent parts to examine the persistency of any integration effects on outcomes as well as any short- versus long-run dynamics in physician behavior changes. We estimate both Equation (1) and Equation (2) using ordinary least squares (OLS) and cluster the standard errors at the physician level throughout.

5. Results

5.1. Use of ASC treatment settings

Table 1 stratifies our analytic data by the three mutually exclusive physician groups according to their vertical integration status (i.e., ‘newly’, ‘never’, and ‘always’ classifications) and summarizes their baseline year (2009) characteristics. 81% of our observed physicians are never acquired by a hospital or health system from 2009–2015. 441 physicians are vertically integrated during our analytic window and therefore comprise our treatment group of interest.

Table 1:

Baseline (2009) Summary Statistics for Analytic Sample

| Become Vertically Integrated | Never Vertically Integrated | Always Vertically Integrated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Any ASC Use | 33.1 | 43.3 | 15.0 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Number of ASCs | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Share of Medicare Cases in ASCs | 0.17 (0.33) | 0.28 (0.40) | 0.04 (0.13) |

| Share of Commercial Cases in ASCs | 0.17 (0.32) | 0.30 (0.40) | 0.05 (0.16) |

| Total Cases | 212.0 (320.9) | 194.6 (345.0) | 197.8 (280.4) |

| Total Charges (‘000) | 2,068 (1,151) | 1,474 (2,083) | 1,573 (2,030) |

| Avg. Number of Procedures per Case | 3.4 (2.9) | 3.3 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.5) |

| Observations (N) | 441 | 4,321 | 567 |

Notes: Analytic data are from the universe of outpatient procedure discharge records in Florida. “Commercial” refers to privately insured, non-Medicare patients. “HOPDs” are hospital outpatient departments. “ASCs” are ambulatory surgery centers. All reported charges are in nominal dollars and are not deflated by any cost-to-charge discount factor.

Consistent with the patterns in Figure 1, only 15% of physicians persistently integrated with a hospital use an ASC at all and less than 5% of their Medicare and commercially insured cases take place within an ASC. Conversely, 43% of the never vertically integrated physicians rely on an ASC at some point, and they devote approximately 30% of their Medicare and commercial outpatient procedure business to ASC settings. Across most baseline metrics in Table 1, the physicians that will eventually become vertically integrated represent an intermediate group between the two extremes (i.e., the ‘never’ and ‘always’ integrated classifications). A notable exception is that the physicians targeted by hospitals during our study period actually perform more cases and have higher total reported charges ($2.07 million), on average, than either of the other groups in 2009. Though only suggestive, this could be indicative of strategic acquisition targeting by hospitals whereby more productive and higher revenue-generating physicians are sought out to be vertically integrated.

Table 2 provides our first set of DD estimates and specifically focuses on changes in ASC treatment setting utilization and allocations. In column 1, the DD estimate reveals a statistically significant and negative extensive margin effect for ASC use. Following vertical integration with a hospital, physicians are approximately 3-percentage points less likely to perform any outpatient procedure cases within an ASC, which is a 9% reduction from their baseline level (Table 1). The estimate in column 2 similarly shows a statistically significant and 13% relative decline for the number unique ASCs where cases are performed in a given year. Unsurprisingly, columns 3 and 4 of Table 2, show roughly 9% declines in the share of Medicare (column 3) and commercially insured (column 4) outpatient procedures devoted to ASCs. Importantly, the findings in Table 2 are collectively consistent with vertical alignment between hospitals and physicians engendering foreclosure effects on competing ASCs.

Table 2:

Vertical Integration Effects on Physicians’ Outpatient Procedure Allocations to ASCs

| Any ASC Use | Number of ASCs | Share of Medicare Cases in ASCs | Share of Commercial Cases in ASCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.029** (0.011) |

−0.051*** (0.017) |

−0.016** (0.008) |

−0.015** (0.007) |

|

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Physician FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 37,303 | 33,214 | 34,683 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,100 | 5,272 |

Analytic sample includes the universe of outpatient procedure discharge records in Florida from 2009–2015. “Vertically Integrated” is equal to one for physicians that report hospital or health system ownership of their practice in a given year. “Medicare” includes all patients in the traditional (fee-for-service) public insurance program. “Commercial” refers to privately insured, non-Medicare patients. “HOPDs” are hospital outpatient departments. “ASCs” are ambulatory surgery centers. Columns 1 and 2 capture the number of unique facilities where procedures are performed (by facility type) within a given year. All models include year and physician fixed effects (FE). Standard errors are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

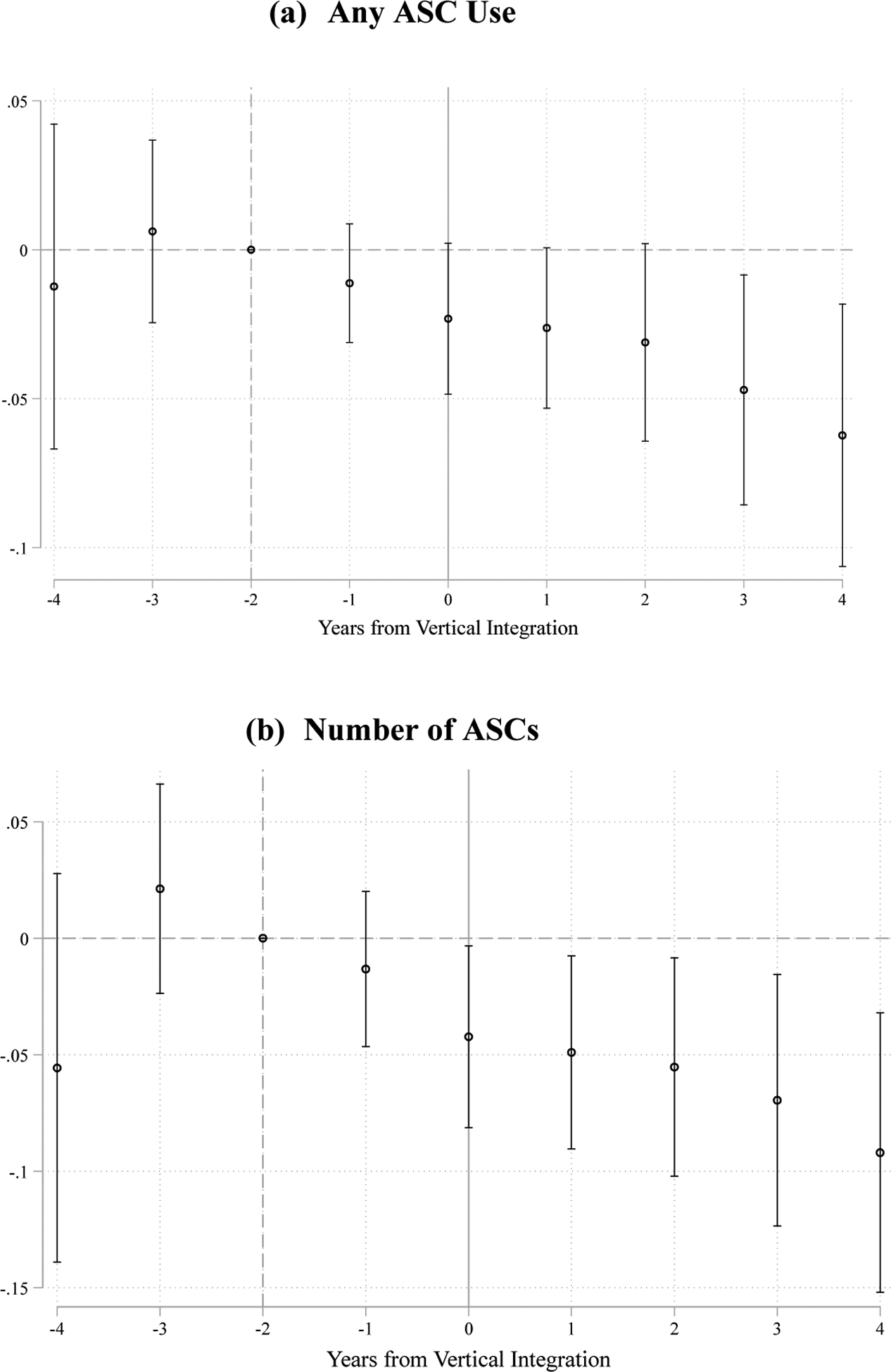

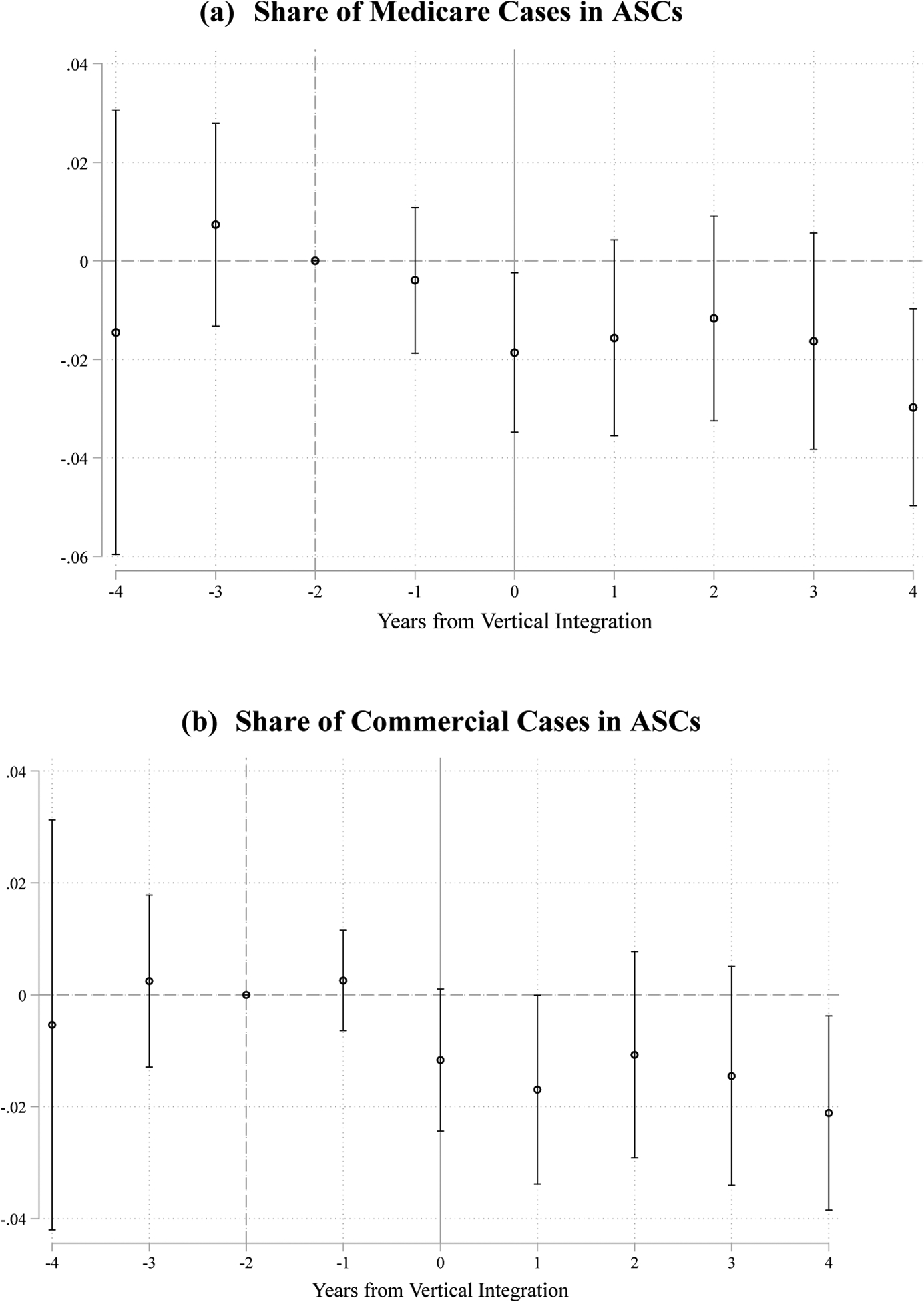

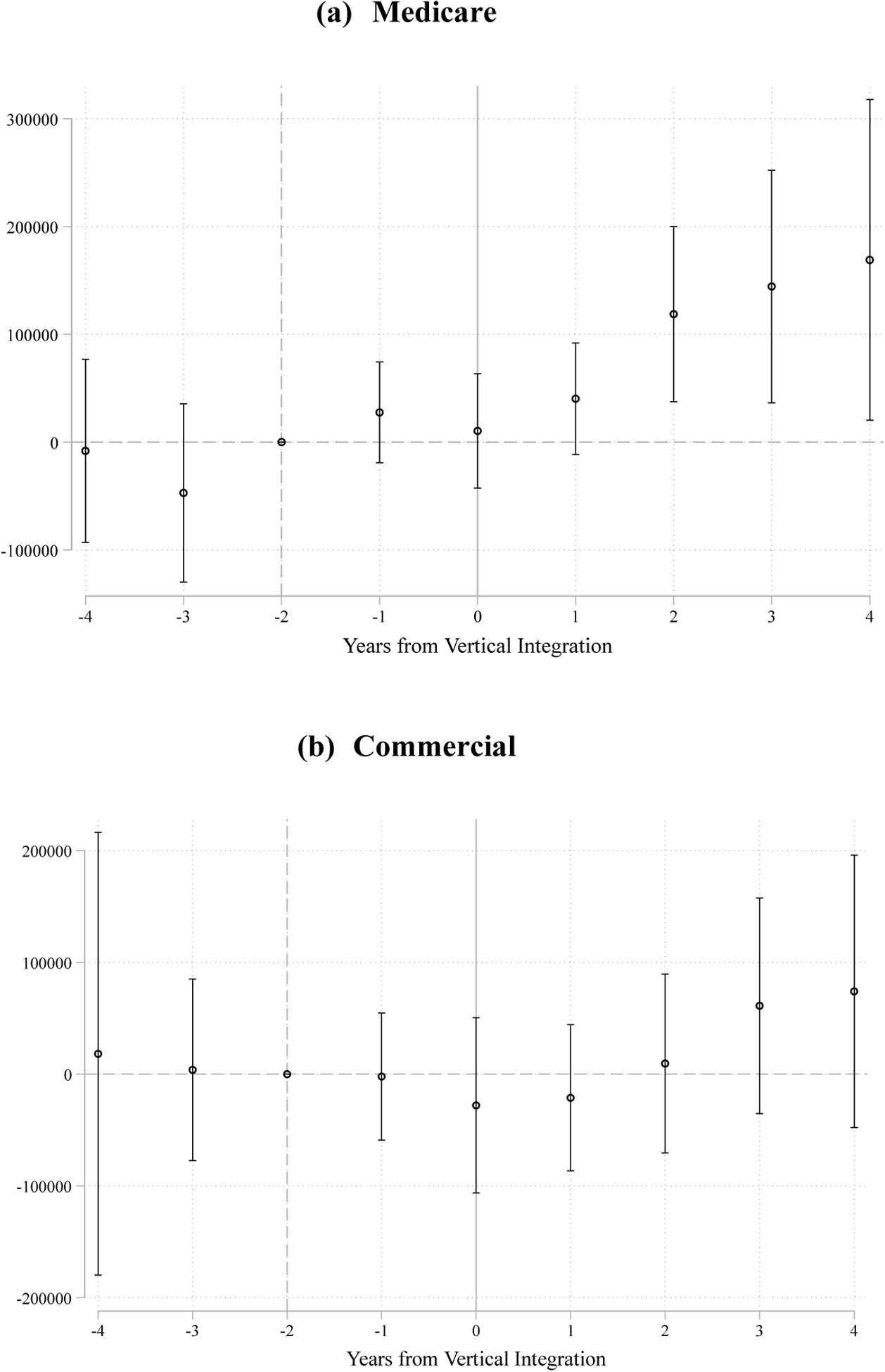

We examine these effects further with the corresponding event study results presented in Figures 2 and 3. The pre-integration estimates in Figure 2 with respect to the ASC extensive (Panel A) and intensive (Panel B) margins are reasonably well-behaved. The coefficients oscillate around zero and are never statistically different from zero, which aligns with the parallel trends requirement for the DD research design.13 Following a hospital acquisition (at time t = 0), however, the affected physicians demonstrate restrained ASC use. The vertical integration effects in Panels A and B also grow over time—approximately doubling from the year of integration (t = 0) to four years after integration (t = 4). Specifically, the newly integrated physicians are roughly 6-percentage points less likely to perform any procedures within an ASC in the fourth year following integration with a hospital or health system (Panel A, Figure 2), which is an 18% reduction over their baseline level (Table 1). Similar to Figure 2, Figure 3 shows no differential trending for the treatment group in terms of ASC allocations for Medicare and commercially insured cases (analyzed in isolation) prior to the year of vertical integration (Panels A and B), but an abrupt and persistent drop emerges during the year of integration (t = 0) with some growth in magnitude by the fourth and final year post-integration. More specifically, the declines in ASC use by the final post-integration year translate to approximately 18% and 12% relative changes (Medicare and commercial cases, respectively) from baseline for these newly acquired physicians (Table 1).

Figure 2:

Event Study Results for Effects on Physicians’ Outpatient Procedure Allocations to ASCs

Notes: Analytic sample and variable definitions are the same as those belonging to Table 2.

Figure 3:

Event Study Results for Effects on Physicians’ ASC Use by Payer Type

Notes: Analytic sample and variable definitions are the same as those belonging to Table 2.

5.2. Treatment output and reported charges

Table 3 moves to vertical integration effects on physicians’ supply of outpatient services and associated charges. With respect to physician output and effort, it is at least theoretically possible that any prior financial interests in ASCs could have led these physicians to over-supply patients with elective procedures—consistent with other work demonstrating physicians’ profit opportunities can distort agency on the behalf of patients (e.g., see Afendulis and Kessler 2007; Iizuka 2012). In this way, the weakening, if not severing, of such financial motives tied to ASCs could lower outpatient procedural intensity at the physician level. On the other hand, hospitals could exercise their own pressure on newly acquired physicians to increase effort and hence revenues, so any a priori prediction is ambiguous, which necessitates empirical investigation.

Table 3:

Vertical Integration Effects on Physicians’ Outpatient Procedure Output and Charges

| Total Cases | Avg. Procedures Per Case | Total Charges (‘000) | Total Medicare Charges (‘000) | Total Commercial Charges (‘000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| −3.121 | −0.095 | 214.4*** | 76.3** | 4.3 | |

| (5.505) | (0.139) | (71.8) | (32.3) | (32.9) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Physician FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 |

Analytic sample includes the universe of outpatient procedure discharge records in Florida from 2009–2015. “Vertically Integrated” is equal to one for physicians that report hospital or health system ownership of their practice in a given year. “Medicare” includes all patients in the traditional (fee-for-service) public insurance program. “Commercial” refers to privately insured, non-Medicare patients. The procedures per case outcome captures the total number of Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes listed on a given outpatient discharge record. All reported charges are in nominal dollars (in thousands) and are not deflated by any cost-to-charge discount factor All models include year and physician fixed effects (FE). Standard errors are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

The estimates in columns 1 and 2 of Table 3 do not reveal any effect of becoming vertically integrated on physicians’ annual case volume nor the average number of procedures performed per case. The DD coefficients are negatively signed, small in relative magnitude (compared to Table 1 baseline levels), and nowhere near statistically significant at conventional levels. There is therefore no evidence of inducing greater outpatient procedure output; instead, the hospital-physician integration effects are confined to charges in Table 3. Across all cases and payers, acquired physicians increase their total annual charges by over $200,000 (nominal dollars), on average, which is approximately 10% above their baseline levels in 2009 (Table 1). When examining Medicare and commercial charges in isolation (columns 4 and 5, respectively), we can further see that Medicare charges, specifically, account for over a third of the integration effect evident in column 3. Commercial charges are largely unchanged following physician practice acquisition by a hospital or health system.

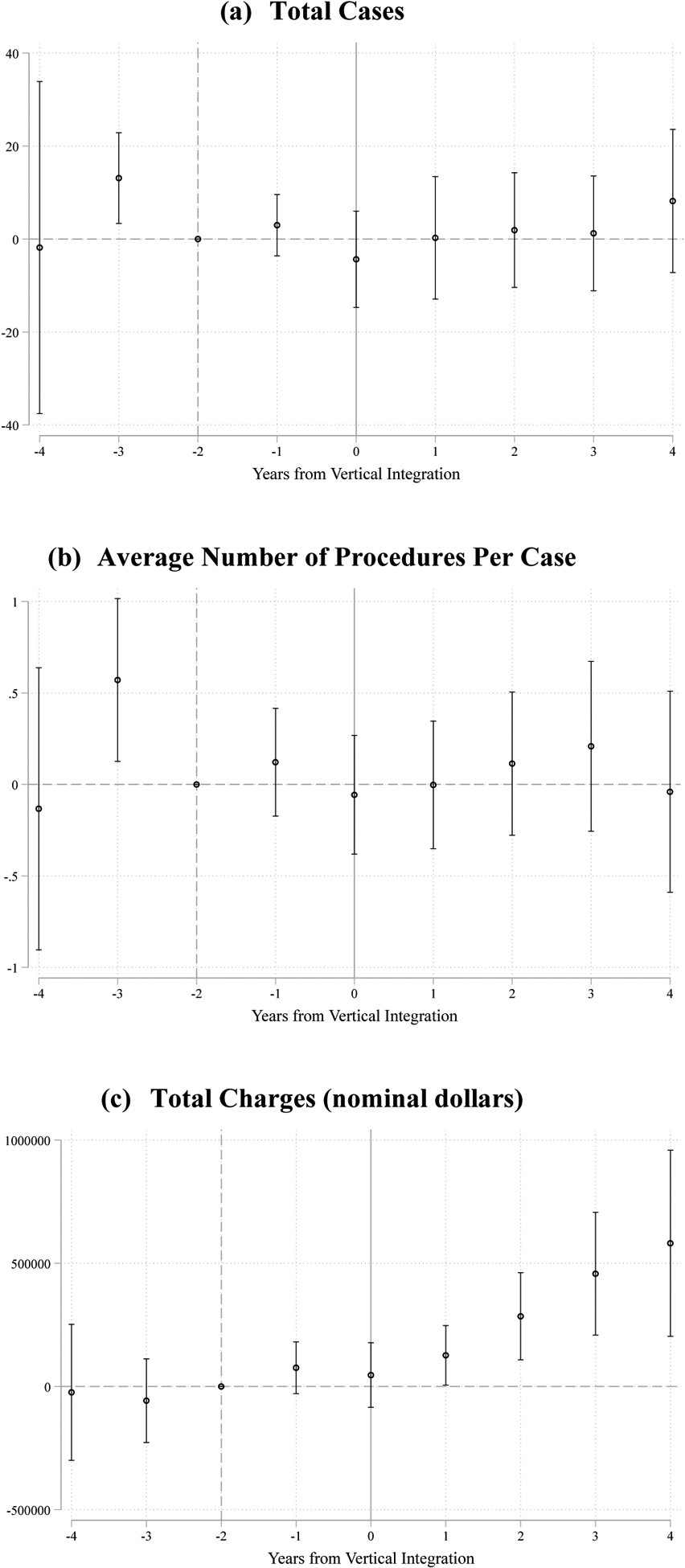

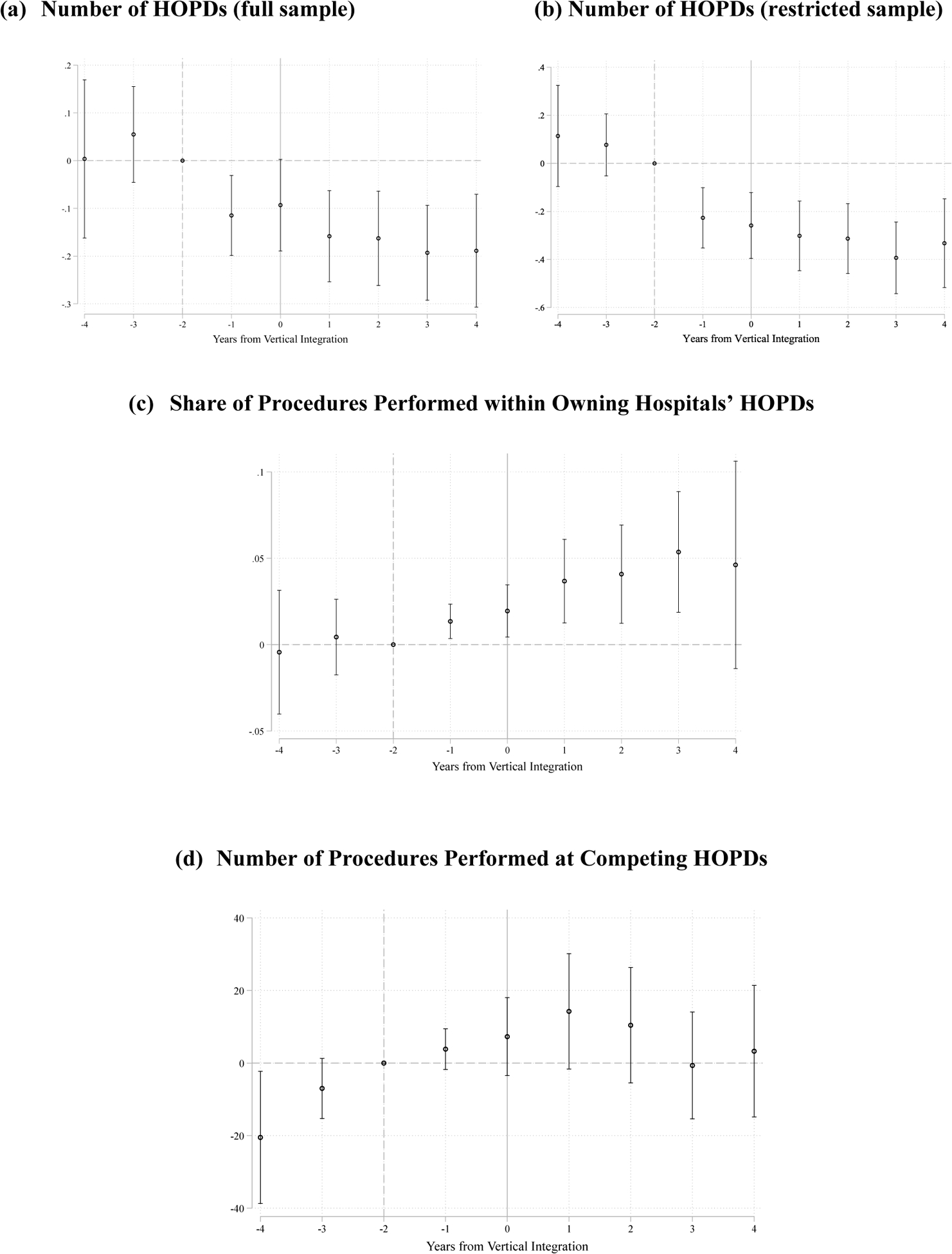

The event study results in Figures 4 and 5 support the inferences from the DD estimates in Table 3. Physicians vertically integrated with a hospital show no meaningful differential behavior related to aggregate outpatient cases or average number of procedures per case in the years prior to integration or after being vertically integrated (Panels A and B, Figure 4). The only statistically significant estimate in Panel A or Panel B in Figure 4 is for the (t = −3) period, and it appears to be an aberration. The fourteen other event-time estimates in Panels A and B of Figure 4 are near zero and not statistically different from zero. Within Panel C of Figure 4, the event study coefficients fluctuate around zero and are not statistically different from zero over the (t = −4) through the (t = 0) event-time periods; however, staring at one year post-integration (t = 1), a statistically significant differential pattern for annual total charges (across all payers) begins to emerge and culminates in a roughly 25% increase over the baseline (2009) level by the end of the post period (t = 4). The event study for Medicare charges (Panel A, Figure 5) demonstrates an analogous pattern; meanwhile, the commercial charges only begin to suggestively increase at three and four years out from the initial integration year (Panel B, Figure 5).

Figure 4:

Event Study Results for Effects on Physicians’ Outpatient Procedure Output and Charges

Notes: Analytic sample and variable definitions are the same as those belonging to Table 3.

Figure 5:

Event Study Results for Effects on Physicians’ Outpatient Procedure Charges by Payer Type

Notes: Analytic sample and variable definitions are the same as those belonging to Table 3.

Admittedly, reported charges are not the same as true transaction prices, so appropriate caveats do apply when interpreting the results from the charge-related outcomes in Figures 4 and 5. We do note, however, that charges often serve as a basis for provider-payer contracting (e.g., see Cooper et al. 2019; Weber, Floyd, Kim, and White 2019) and that our estimates are necessarily capturing within-physician changes over time.14 Put differently, our estimates reveal that these physicians’ total reported charges demonstrate no differential behavior compared to their peers over a roughly 5-year interval spanning the four years before and the first year of being vertically integrated but then show marked and statistically significant changes during subsequent years following vertical integration with a hospital or health system. This pattern is at least consistent with a causal link between hospital acquisitions and altered physician behavior tied to outpatient procedure costs and/or pricing.

We also acknowledge the possibility that acquiring hospitals induce physicians to substitute toward more complex—and thus higher billing—outpatient services while leaving the aggregate quantity of services supplied to the market unchanged. However, it is unclear why the acquired physicians would have refrained from doing so prior to integration since any foregone opportunities to deliver higher complexity care would have sacrificed earnings from the physician fee component as well (i.e., such behavior would be inconsistent with physicians’ own profit-maximizing objective). The contrast between the Medicare and commercial payers in Figure 5 also seems to align with traditional Medicare billing rules. Namely, as a matter of federal law, the Medicare program is statutorily required to pay ASCs no more than 59% of the prevailing HOPD facility fee for an otherwise identical outpatient procedure—see Munnich and Parente (2018) for details. Other studies document the reallocation of physician services from physician office locations to hospital facility sites is, at least partially, driven by the ability to exact higher payments from the Medicare program (Song et al. 2015; Koch et al. 2017; Dranove and Ody 2019). The effects we observe, particularly for Medicare charges in Table 3 and Figure 5, are at least consistent with similar circumstances, whereby existing Medicare payment policy tied to outpatient site differentials creates an opportunity to capture larger reimbursements for delivering the same care once newly acquired physicians begin substituting HOPD settings for ASCs.

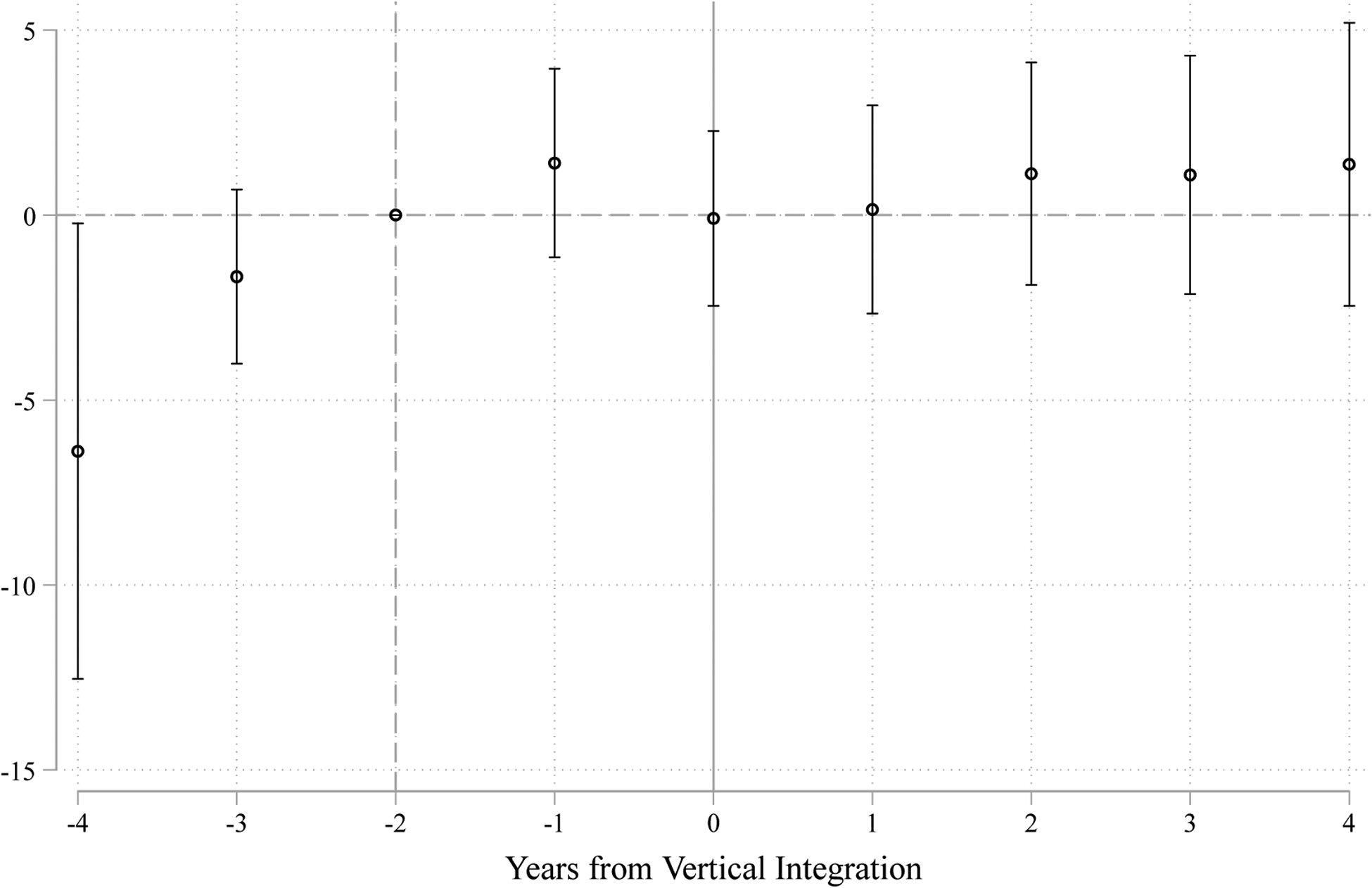

Within Appendix Figures 1 and 2, we display the event study results for two additional outcomes of potential interest. The former captures the total volume of Medicaid outpatient procedure cases. Although an association has been found between vertical integration and physician practice participation in the Medicaid program (e.g., see Richards et al. 2016; Haddad, Resnick, and Nikpay 2020), we find no effect on the number of outpatient procedures performed for Medicaid patients (Appendix Figure 1). As another potential implication for consumer welfare, we examined the distance between the patient’s residential zip code (centroid) and the outpatient facility’s zip code (centroid) belonging to a given outpatient procedure discharge record. We again do not observe any effect along this margin, on average, which is perhaps not surprising since ASC firms are commonly found in urban areas where the market size effect is likely to encourage colocation by ASCs and HOPDs within the same geographic area. Foreclosing on ASC competitors through vertical integration with upstream physicians would consequently shift affected patients to a potentially higher cost but not necessarily more distant treatment setting.

6. Exploring Effects on Competing Hospitals

6.1. Approach

We conclude our empirical analyses by examining vertical integration effects on HOPD-specific care delivery outcomes. Our previous findings reveal cross-industry foreclosure effects on ASCs following the vertical integration of physician practices, but a second consolidation channel remains possible. Specifically, the acquiring hospital could redirect case referrals to itself that would have otherwise gone to other, non-affiliated (i.e., competing) HOPDs.

We begin with a simple measure of the total number of unique HOPDs used by a given physician in a given year—which is analogous to our intensive margin measure for ASC use in Table 2 and Figure 2. This analysis incorporates the same 5,329 unique physicians that belong to the previous estimations and results from Section 5 and uses Equations (1) and (2) as the corresponding DD regression specifications.

We then move to a more detailed and supplementary exercise that examines the allocation of HOPD cases between owning and non-owning hospitals and health systems. To do so, we restrict our estimation sample to physicians that are either always vertically integrated or newly integrated during our study period. This step is necessary to classify a given procedure as taking place within an owning or non-owning HOPD. Such a classification does not apply to the physicians that are never vertically integrated over our study period and is therefore infeasible for that subset of physicians. Next, we use information provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to assign Florida HOPDs to their respective individual hospital or health system (i.e., multiple hospital) parent companies insofar as the reported HOPD facility name allowed for such a classification.15 For each individual physician, we use the reported owning hospital or health system in the SK&A data to match to the corresponding always owning (with respect to the always vertically integrated group) or eventually owning (with respect to the newly integrated group) entity, again, insofar as the reported name is sufficiently accurate and specific to make a credible assignment. We are able to successfully complete these two stages of mapping (i.e., HOPD facility to owning hospital and physician to owning hospital) for 57% of our potential analytic sample. All HOPD-delivered procedures in a given physician-year are subsequently allocated to one of two categories: the owning hospital or competing hospitals. Following this classification, we create a physician-quarter-year measure for the share of HOPD cases performed within a HOPD that is part of the always or eventually owning hospital or health system. We then examine the quantity of cases performed at HOPDs belonging to competing hospitals in order to understand if greater consolidation of cases among the owning hospital’s or health system’s HOPDs is at the expense of competing (non-owning) hospitals’ case volumes. We again implement Equation (1) and Equation (2) on this subset of physicians to formally test for such post-vertical integration effects.

6.2. Supplementary Findings

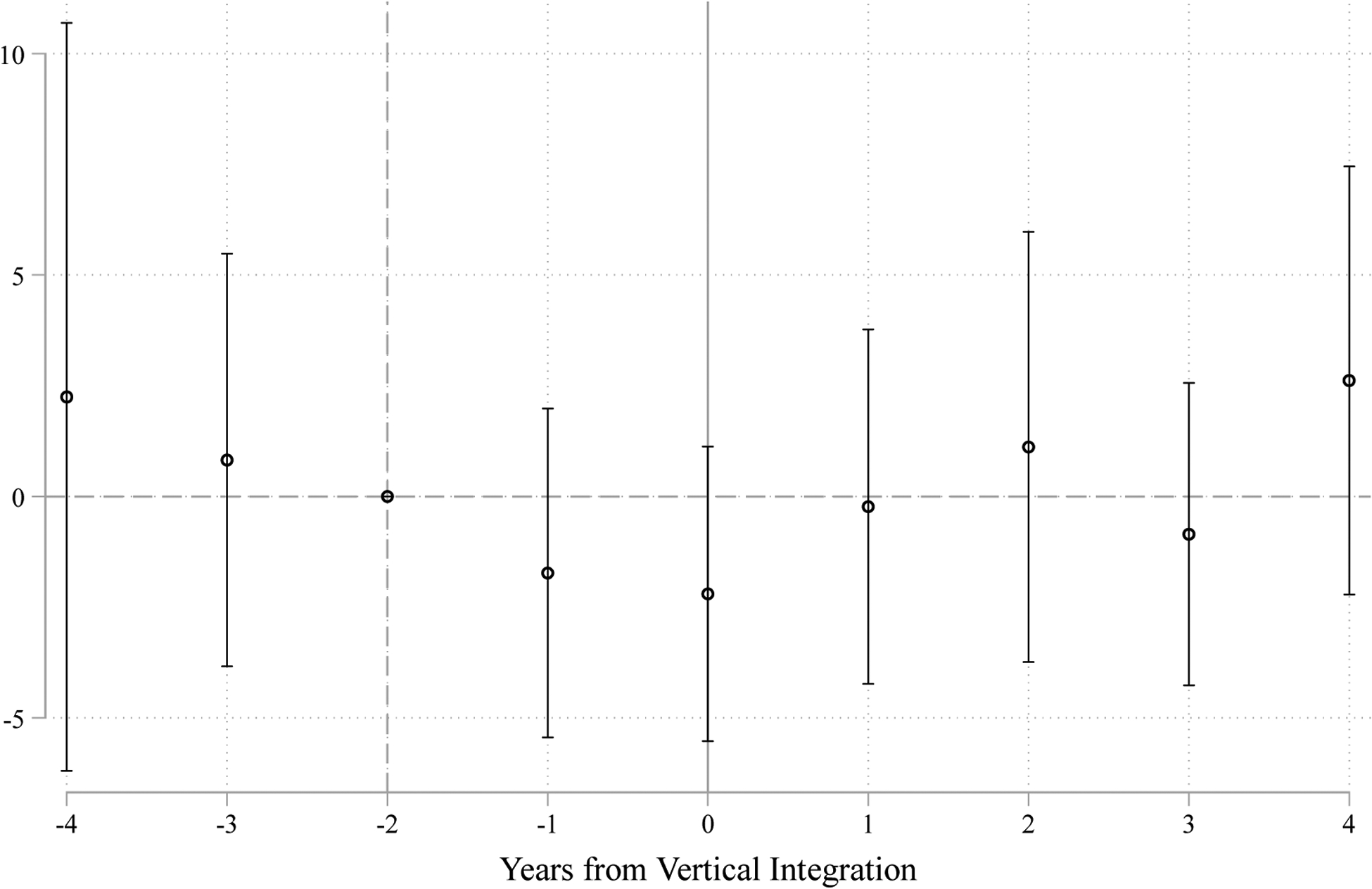

Column 1 of Table 4 suggests that becoming newly integrated with a hospital lowers the number of unique HOPDs the physician relies on a given year. The effects are statistically significant, and relative to the treatment group’s baseline level (Table 1), it translates to a 6% decline, on average. However, the corresponding event study results in Panel A of Figure 6 reveal a statistically significant decrease for intensive margin HOPD use occurring in the year immediately preceding the vertical integration event (i.e., when j = −1). The decline then grows over subsequent years, with the negative effect nearly twice as large by the third and fourth post-vertical-integration years (Panel A, Figure 6).

Table 4:

Vertical Integration Effects on Physicians’ HOPD Procedure Allocations

| Restricted Analytic Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of HOPDs | Number of HOPDs | Share of Procedures Performed within Eventually Owning Hospitals’ HOPDs | Number of Procedures Performed at Competing HOPDs | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.115*** (0.035) |

−0.211*** (0.051) |

0.027*** (0.010) |

8.611 (6.334) |

|

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Physician FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 3,997 | 3,997 | 3,997 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 571 | 571 | 571 |

| Baseline Mean (2009) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.51 | 75.4 |

Column 1 analytic sample is the same as Tables 2 and 3. Within columns 2–4, the analytic sample is restricted to the newly vertically integrated and the always vertically integrated subgroups of Florida physicians during the 2009–2015 period. For both groups, we partition individual physicians’ total HOPD procedures by two settings: owning hospitals and competing (non-owning) hospitals. For the physicians being newly integrated during our study period, we use the hospital/health system that will eventually acquire their practice to create their panel of procedure allocations. “Vertically Integrated” is equal to one for physicians that report hospital or health system ownership of their practice in a given year. “HOPDs” are hospital outpatient departments. All models include year and physician fixed effects (FE). Standard errors are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Figure 6:

Event Study Results for Effects on Physicians’ HOPD Procedure Allocations

Notes: Analytic samples and variable definitions are the same as those belonging to Table 4.

Although the decline prior to vertical integration could suggest pre-trending issues between the treatment and control physicians for this specific outcome, the estimates for the previous three pre-integration years do not align with a clear, general trend. Specifically, there is no differential trending between treatment and control physicians over the three-year interval from j = −4 through j = −2.16 The coefficients are also nearly identical in magnitude between the year of integration (j = 0) and the previous year (j = −1), as opposed to following a smooth decline over the entire pre- and post-integration periods. Taken together, the event study findings in Panel A of Figure 6 are at least consistent with anticipatory behavior whereby the physician reduces the number of HOPDs used to perform procedures before vertically integrating with a local hospital or health system. Such behavior seems plausible since both parties in the transaction may want to signal interest in and/or test out the potential alignment before acquisition terms are finalized and executed (i.e., during the j = 0 period). The presence of the behavior change beginning in the (j = −1) period will also lead the DD estimate for this outcome in column 1 of Table 4 to be understated since the change is in the same direction as the estimates belonging to the full post-integration period (j = 0 through j = 4).

Next, we examine the findings for the supplementary analyses using our further restricted sample of Florida physicians. We first demonstrate in column 2 of Table 4 and Panel B of Figure 6 that the results are qualitatively similar for the number of HOPDs outcome when making this sample restriction. Reassuringly, the DD estimates and event-time estimates for the restricted sample align well with those from the full analytic sample. Turning our attention to just the restricted sample, we observe in column 3 of Table 4 that, at baseline (2009), approximately half of all HOPD procedures were performed within the hospital or health system that would eventually acquire the physician. The share of HOPD cases flowing to the parent hospital or health system also increases with integration (column 3, Table 4). The event study findings further indicate that there are dynamics in the effects—representing as much as a 10% increase during the years following hospital acquisition (Panel C, Figure 6). There is also evidence of behavior change occurring during the year immediately prior to becoming vertically integrated, which aligns with the pattern observed in Panels A and B of Figure 6. Importantly, there is no indication in Table 4 or Figure 6 that the owning hospital’s gains in case shares are the result of business stealing from competing hospitals. The quantities of procedures flowing to these other (non-owning hospital HOPDs) show no compelling change in the aftermath of the physician being vertically integrated. When coupled with the findings from Table 2 and Figures 2–3, vertical integration’s effect on outpatient procedure redirection seems to localize to ASCs in contested markets. In other words, the underlying increase in case volumes for owning hospital HOPDs that create the observed increase in their respective shares of cases seems to rely on capturing outpatient procedures that would have otherwise gone to ASCs. This suggests that the vertical integration strategy appears to matter more for across industry, rather than within-industry, competition in this health care delivery context.

7. Discussion

A growing literature has documented deleterious health care price and spending influences from the recent trend in hospital-physician integration across the US. However, understanding the more diffuse consequences of these vertical alignments between providers as well as the various mechanisms underneath any observed price or spending rise requires empirical investigation into the anticompetitive (i.e., foreclosure) effects of these hospital acquisitions. A few existing studies (i.e., Baker et al. 2016; Carlin et al. 2016; and Koch et al. 2017) have shed light on vertical integration’s impact on hospital referral patterns. In this paper, we extend these findings by providing evidence of foreclosure effects across industries. Specifically, our DD and event study results show a reallocation of outpatient procedures from ASCs to HOPDs across payers and as much as an 18% reduction in the likelihood of a newly acquired physician using an ASC at all. At the same time, our supplementary analyses do not suggest that other competing hospitals are losing cases following the purchase of a common upstream supplier (i.e., physician). Acquired physicians are also charging more for their outpatient procedural care—especially within the traditional Medicare market—after becoming vertically integrated. Importantly, the relaxing of horizontal competition between ASCs and HOPDs for outpatient procedural care occurs without any horizontal consolidation activity; instead, it results from hospitals’ vertical integration with physicians.

Others have highlighted that more than a billion dollars of savings to patients and purchasers is left on the table due to Medicare’s disparate payments between HOPDs and ASCs for otherwise identical care (Sood and Whaley 2019). And more broadly, site of care differentials remain a source of elevated health care expenditures and hence key considerations for future policymaking (Song et al. 2015; Higgins, Veselovskiy, and Schinkel 2016; Koch et al. 2017; Capps et al. 2018; Dranove and Ody 2019; Jung, Feldman, and Kalidindi 2019). Our findings are consistent with these notions since, as a matter of federally mandated payment policy, every Medicare outpatient procedure redistributed from an ASC to a HOPD post-acquisition will generate at least a 69% increase in the corresponding facility fee. Furthermore, the potential for a for-profit (ASC) to not-for-profit (HOPD) facility setting substitution post-integration can lead to foregone tax revenue at the state and federal levels.17 According to a trade press article, the ASC industry made nearly $6 billion in tax payments in the year 2009 alone (Becker’s ASC Review 2017). By contrast, estimates suggest that not-for-profit hospitals received over $24 billion worth of tax exemptions in 2011 (Rosenbaum et al. 2015).

We do acknowledge that upsides from formal hospital-physician alignment are possible. For example, vertical integration has shown positive associations with health information technology adoption and use (e.g., see Lammers 2013; Everson, Richards, and Buntin 2019). Yet, our study demonstrates that hospitals can and do leverage physician acquisitions to foreclose on potentially more efficient rivals (i.e., ASCs). Moreover, recent research (Carey 2017; Whaley and Brown 2018; Baker, Bundorf, and Kessler 2019) finds that greater competitive pressure on hospitals from ASCs depresses prices within outpatient procedure markets. Foreclosing on ASCs through vertical integration is likely to undermine ASCs’ ability to discipline hospitals in this way and promote greater efficiency in the market. For these reasons, the anticompetitive consequences from hospitals acquiring physician practices that we document carry downstream risks of consumer welfare losses within affected markets. They can also strain public finances through existing site-of-care payment policies that lead to higher spending for the same basket of outpatient services. Taken together, greater scrutiny of hospital-physician integration by antitrust authorities and regulators is likely warranted.

Highlights.

Vertical integration between hospitals and physicians is increasing in the US

Negative consequences from vertical integration include changes in referrals

We show novel evidence of foreclosure effects across industries

Hospitals steal business from ASCs after acquiring physician practices

The effects we identify can worsen consumer welfare and market competition

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Florida Agency for Healthcare Administration (AHCA) and the RAND Corporation for providing excellent data resources. AHCA was not responsible for any data analyses or interpretations. Whaley would also like to thank the National Institutes on Aging (1K01AG061274) for its generous financial support. All views and errors belong solely to the authors.

APPENDIX RESULTS

Appendix Table 1:

| Any ASC Use | Number of ASCs | Share of Medicare Cases in ASCs | Share of Commercial Cases in ASCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.012 | −0.056 | −0.015 | −0.0054 | |

| (0.028) | (0.043) | (0.023) | (0.019) | |

| Time == −3 | 0.0062 | 0.021 | 0.0073 | 0.0025 |

| (0.016) | (0.023) | (0.010) | (0.0078) | |

| Time == −1 | −0.011 | −0.013 | −0.0039 | 0.0026 |

| (0.010) | (0.017) | (0.0075) | (0.0046) | |

| Time == 0 | −0.023 | −0.042** | −0.019** | −0.012 |

| (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.0082) | (0.0065) | |

| Time == 1 | −0.026 | −0.049** | −0.016 | −0.017** |

| (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.010) | (0.0086) | |

| Time == 2 | −0.031 | −0.055** | −0.012 | −0.011 |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.011) | (0.0094) | |

| Time == 3 | −0.047** | −0.070** | −0.016 | −0.015 |

| (0.020) | (0.028) | (0.011) | (0.0100) | |

| Time == 4 | −0.062*** | −0.092*** | −0.030*** | −0.021** |

| (0.022) | (0.031) | (0.010) | (0.0088) | |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 37,303 | 33,214 | 34,683 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,100 | 5,272 |

Standard errors in parentheses

All regressions are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Appendix Table 2:

| Total Cases | Avg. Procedures Per Case | Total Charges (‘000) | Total Medicare Charges (‘000) | Total Commercial Charges (‘000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| −1.82 | −0.13 | −23546.8 | −8182.9 | 18210.9 | |

| (18.2) | (0.39) | (140747.8) | (43390.5) | (100969.7) | |

| Time == −3 | 13.1*** | 0.57** | −57418.1 | −47198.1 | 3845.6 |

| (4.98) | (0.23) | (86561.8) | (42216.8) | (41415.3) | |

| Time == −1 | 2.99 | 0.12 | 76202.7 | 27596.3 | −2148.6 |

| (3.36) | (0.15) | (53545.5) | (23883.9) | (29030.1) | |

| Time == 0 | −4.36 | −0.057 | 46428.3 | 10325.8 | −27966.2 |

| (5.29) | (0.17) | (66803.1) | (27093.7) | (40023.1) | |

| Time == 1 | 0.27 | −0.0025 | 126695.5** | 40233.4 | −21174.9 |

| (6.71) | (0.18) | (61781.4) | (26421.7) | (33347.0) | |

| Time == 2 | 1.92 | 0.11 | 284877.0*** | 118764.7*** | 9497.3 |

| (6.28) | (0.20) | (90139.5) | (41438.2) | (40813.9) | |

| Time == 3 | 1.23 | 0.21 | 457833.3*** | 144425.2*** | 61144.7 |

| (6.29) | (0.24) | (127133.6) | (55044.2) | (49239.3) | |

| Time == 4 | 8.18 | −0.040 | 581368.0*** | 169058.6** | 73993.2 |

| (7.85) | (0.28) | (192643.8) | (75867.5) | (62174.2) | |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 | 37,303 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 | 5,329 |

Standard errors in parentheses

All regressions are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Appendix Figure 1:

Vertical Integration Effects on Medicaid Case Volumes

Appendix Figure 2:

Vertical Integration Effects on Patient-to-Facility Distance (in miles)

Appendix Table 3:

Event Study Estimates Corresponding to Figure 6

| Number of HOPDs (Full Sample) | Number of HOPDs (Restricted Sample) | Share of procedures Performed within Owning Hospitals’ HOPDs | Number of Procedures Performed at Competing HOPDs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Time == −4 | 0.0035 | 0.114 | −0.004 | −20.503** |

| (0.084) | (0.107) | (0.018) | (9.278) | |

| Time == −3 | 0.055 | 0.077 | 0.004 | −6.983 |

| (0.051) | (0.066) | (0.011) | (4.231) | |

| Time == −1 | −0.11*** | −0.227*** | 0.013*** | 3.844 |

| (0.043) | (0.064) | (0.005) | (2.858) | |

| Time == 0 | −0.093 | −0.259*** | 0.019** | 7.279 |

| (0.049) | (0.070) | (0.008) | (5.465) | |

| Time == 1 | −0.16*** | −0.301*** | 0.037*** | 14.256 |

| (0.049) | (0.074) | (0.012) | (8.098) | |

| Time == 2 | −0.16*** | −0.313*** | 0.041*** | 10.428 |

| (0.050) | (0.074) | (0.014) | (8.097) | |

| Time == 3 | −0.19*** | −0.393*** | 0.054*** | −0.655 |

| (0.051) | (0.076) | (0.018) | (7.490) | |

| Time == 4 | −0.19*** | −0.332*** | 0.046 | 3.275 |

| (0.060) | (0.094) | (0.031) | (9.226) | |

| Observations (N) | 37,303 | 3,997 | 3,997 | 3,997 |

| Unique Physicians | 5,329 | 571 | 571 | 571 |

Standard errors in parentheses

All regressions are clustered at the physician level.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

See these statistics from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, available here: https://www.ahrq.gov/news/newsroom/ambulatory-surgery.html.

We also note that hospital-to-physician vertical integration is distinct from other vertical integration strategies that involve the hospital industry, such as large tertiary or specialty hospitals acquiring smaller “feeder” hospitals to gain profitable referrals (e.g., see Huckman 2006; Nakamura, Capps, and Dranove 2007).

See these and related statistics tabulated by the American Medical Association here: https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/employed-physicians-outnumber-self-employed.

See Burns et al. (2013) and Post et al. (2018) for excellent reviews of the theoretical underpinnings of hospital-physician vertical integration strategies as well as related empirical evidence.

Put differently, her earnings would be restricted to the physician-specific (non-facility) component of payment tied to the cases she performed.

Potentially, the hospital could even consider divestures of existing practices—so long as doing so would not reintroduce the threat of ASC entry and/or sacrifice other profitable benefits from integration (e.g., insurance bargaining). Also, absent a monopoly position within the downstream hospital market, the hospital would still have to compete for physician referrals against other hospitals.

Note, SK&A was recently acquired by IQVIA, which has now combined their respective physician survey data repositories.

State-level statistics on aggregate Medicare populations can be found here: https://www.kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/total-medicare-beneficiaries.

For the minority of physicians that practice in more than one office, we use a hierarchical classification of ownership so that the highest degree of ownership across all practices tied to a given physician in a given year is assigned to that physician in that year.

We collapse the quarterly discharge data to the annual level since our physician ownership data are necessarily at that level (i.e., we cannot observe the precise timing of an ownership transition within a calendar year).

Note, the value of the event-time variables is necessarily zero for all physicians within our control comparison group (i.e., ‘never’ and ‘always’ integrated physicians).

For example, the maximum number of pre-periods observed would be four and only present among those vertically integrating in 2013. Likewise, the maximum number of post-periods observed would be four and only present among those vertically integrating in 2011. Recall, physicians being integrated in 2010, 2014, or 2015 are excluded from the analytic sample.

Of note, we have also included regression table versions of all the event study models for ease of viewing the exact estimates and accompanying statistical significance reporting. See Appendix Tables 1–3 for these results by outcome.

Provider reported charges have also been used as an input for constructing proxy price measures for provider panel estimation among recent economic studies (e.g., see Garmon 2017; Darden, McCarthy, and Barrette 2018; Dafny, Ho, and Lee 2019).

The AHRQ Compendium of US Health Systems data links hospitals and other providers to health systems, and is publicly available on AHRQ’s website: www.ahrq.gov/chsp/data-resources/compendium.html

Note, Appendix Table 3 contains the point estimates and significance reporting for the results underlying Figure 6 for ease of viewing.

Essentially half of our observed vertical integration events underlying our analyses are tied to not-for-profit hospitals in Florida, for example.

References

- Afendulis Christopher C., and Kessler Daniel P.. 2007. “Tradeoffs from Integrating Diagnosis and Treatment in Markets for Health Care.” American Economic Review, 97 (3): 1013–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association. 2018. “Trendwatch Chartbook 2018: Trends affecting hospitals and health systems.” Available at https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2018-05-22-trendwatch-chartbook-2018l.

- Aouad Marion, Brown Timothy T., and Whaley Christopher M.. 2019. “Reference Pricing: The Case of Screening Colonoscopies.” Journal of Health Economics, 65, 246–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Laurence C., Bundorf M. Kate, and Kessler Daniel P.. 2014. “Vertical Integration: Hospital Ownership of Physician Practices is Associated with Higher Prices and Spending.” Health Affairs, 33 (5): 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Laurence C., Bundorf M. Kate, and Kessler Daniel P.. 2016. “The Effect of Hospital/Physician Integration on Hospital Choice.” Journal of Health Economics, 50: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Laurence C., Bundorf M. Kate, and Kessler Daniel P.. 2019. “Competition in Outpatient Procedure Markets.” Medical Care, 57 (1): 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannow Tara. 2019. “AHA Data Show Hospitals’ Outpatient Revenue Nearing Inpatient.” Modern Healthcare, Crain Communications, January 3rd 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Becker’s ASC Review. 2017. “51 Things to Know about the ASC Industry | 2017”. Becker’s Healthcare. February 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim B. Douglas and Whinston Michael D.. 1998. “Exclusive Dealing.” Journal of Political Economy, 106 (1): 64–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bian John, and Morrisey Michael A.. 2007. “Free-Standing Ambulatory Surgery Centers and Hospital Surgery Volume.” Inquiry, 44: 200–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns Lawton R., Goldsmith Jeff C., and Sen Aditi. 2013. “Horizontal and Vertical Integration of Physicians: A Tale of Two Tails.” Annual Review of Health Care Management: Revisiting the Evolution of Health Systems Organization. Advances in Health Care Management Volume 15. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; (pp. 39–117). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps Cory, Dranove David, and Ody Christopher. 2018. “The Effect of Hospital Acquisitions of Physician Practices on Prices and Spending.” Journal of Health Economics, 59: 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey Kathleen, Burgess James F. Jr., and Young Gary J.. 2011. “Hospital Competition and Financial Performance: The Effects of Ambulatory Surgery Centers.” Health Economics, 20: 571–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey Kathleen. 2017. “Ambulatory Surgery Centers and Prices in Hospital Outpatient Departments.” Medical Care Research and Review, 74 (2): 236–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin Caroline S., Dowd Bryan, and Feldman Roger. 2015. “Changes in Quality of Health Care Delivery after Vertical Integration.” Health Services Research, 50 (4): 1043–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin Caroline S., Feldman Roger, and Dowd Bryan. 2016. “The Impact of Hospital Acquisition of Physician Practices on Referral Patterns.” Health Economics, 25 (4): 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino Lawrence P., Devers Kelly J., and Brewster Linda R.. 2003. “Focused Factories? Physician- Owned Specialty Facilities.” Health Affairs, 22(6): 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Zack, Craig Stuart V., Gaynor Martin, and Van Reenen John. 2019. “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134 (1): 51–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche Charles and Plotzke Michael. 2010. “Does Competition from Ambulatory Surgical Centers Affect Hospital Surgical Output?” Journal of Health Economics, 29: 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar Alison E., and Gertler Paul J.. 2006. “Strategic Integration of Hospitals and Physicians.” Journal of Health Economics, 25 (1): 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny Leemore, Ho Kate, and Lee Robin S.. 2019. “The Price Effects of Cross-Market Mergers: Theory and Evidence from the Hospital Industry.” RAND Journal of Economics, 50 (2): 286–325. [Google Scholar]

- Darden Michael, Ian McCarthy, and Eric Barrette. 2018. “Who Pays in Pay-for-Performance? Evidence from Hospital Pricing.” NBER Working Paper No. w24304 [Google Scholar]

- Dranove David and Ody Christopher. 2019. “Employed for Higher Pay? How Medicare Payment Rules Affect Hospital Employment of Physicians.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11 (4): 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrda Laura. 2017. “39% of ASCs are 15+ years old, 92% have physician ownership: 14 statistics on ASCs.” Becker’s ASC Review, October 9. Available at https://www.beckersasc.com/benchmarking/39-of-ascs-are-15-years-old-92-have-physician-ownership-14-statistics-on-ascs.html. [Google Scholar]

- Everson Jordan, Richards Michael R., and Buntin Melinda B.. 2019. “Horizontal and Vertical Integration’s Role in Meaningful Use Attestation over Time.” Health Services Research, 54: 1075–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal-Or Esther. 1999. “The Profitability of Vertical Mergers between Hospitals and Physician Practices.” Journal of Health Economics, 18 (5): 623–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmon Christopher. 2017. “The Accuracy of Hospital Merger Screening Methods.” RAND Journal of Economics, 48 (4): 1068–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor Martin and Vogt William. 2000. Antitrust and Competition in Health Care Markets. In Cuyler and Newhouse (eds), Handbook of Health Economics, Volume 1B, Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor Martin, Ho Kate, and Town Robert. 2015. “The Industrial Organization of Health-Care Markets.” Journal of Economic Literature, 53 (2): 235–284. [Google Scholar]

- Grisel Jedidiah and Arjmand Ellis. 2009. “Comparing Quality at an Ambulatory Surgery Center and a Hospital-Based Facility.” Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 141(6): 701–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad Diane N., Resnick Matthew J., and Nikpay Sayeh S.. 2020. “Does Vertical Integration Improve Access to Surgical Care for Medicaid Beneficiaries?” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 230 (1): 130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Margaret J., Schwartzman Alexander, Zhang Jin, Liu Xiang, and Division of Health Care Statistics. 2017. “Ambulatory Surgery Data from Hospitals and Ambulatory Surgery Centers: United States, 2010.” National Health Statistics Reports, No. 102, 28 February 2017, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; US Department of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart Oliver, Tirole Jean, Carlton Dennis W., and Williamson Oliver E.. 1990. “Vertical Integration and Market Foreclosure.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics: 205–286. doi: 10.2307/2534783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Aparna, Veselovskiy German, and Schinkel Jill. 2016. “National Estimates of Price Variation by Site of Care.” American Journal of Managed Care, 22 (3): e116–e121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbeck Brent K., Dunn Rodney L., Suskind Anne M., Zhang Yun, Hollingworth John M., and Birkmeyer John D.. 2014. “Ambulatory Surgery Centers and Outpatient Procedure Use among Medicare Beneficiaries.” Medical Care, 52 (10): 926–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth John M., Krein Sarah L., Ye Zaojun, Kim Hyungjin Myra, and Hollenceck Brent K.. 2011. “Opening of Ambulatory Surgery Centers and Procedure Use in Elderly Patients: Data from Florida.” Archives of Surgery, 146(2): 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckman Robert S. 2006. “Hospital Integration and Vertical Consolidation: An Analysis of Acquisitions in New York State.” Journal of Health Economics, 25 (1): 58–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Toshiaki. 2012. “Physician Agency and Adoption of Generic Pharmaceuticals.” American Economic Review, 102 (6): 2826–2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Jeah, Feldman Roger, and Kalidindi Yamini. 2019. “The Impact of Integration on Outpatient Chemotherapy Use and Spending in Medicare.” Health Economics, 28: 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch Thomas G., Wendling Brett W., and Wilson Nathan E.. 2017. “How Vertical Integration Affects the Quantity and Cost of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries.” Journal of Health Economics, 52: 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch Thomas G., Wendling Brett W., and Wilson Nathan E.. 2018. “The Effects of Physician and Hospital Integration on Medicare Beneficiaries’ Health Outcomes.” Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics Working Paper (No. 337) Available here: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/effects-physician-hospital-integration-medicare-beneficiaries-health-outcomes/working_paper_337.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Lane and Gu Qian. 2013. “Growth of Ambulatory Surgical Centers, Surgery Volume, and Savings to Medicare.” American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers Eric. 2013. “The Effect of Hospital-Physician Integration on Health Information Technology Adoption.” Health Economics, 22 (10): 1215–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynk William J. and Longley Carina S.. 2002. “The Effect of Physician-Owned Surgicenters on Hospital Outpatient Surgery.” Health Affairs, 21(4): 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy Ian and Huang Sean S.. 2018. “Vertical Alignment between Hospitals and Physicians as a Bargaining Response to Commercial Insurance Markets.” Review of Industrial Organization, 53: 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- MedPAC. 2019. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Chapter 5 (Ambulatory Surgical Center Services). March 2019. Available here: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_ch5_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. [Google Scholar]

- Munnich Elizabeth L. and Parente Stephen T.. 2014. “Procedures Take Less Time at Ambulatory Surgery Centers, Keeping Costs Down and Ability to Meet Demand Up.” Health Affairs, 33(5): 764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnich Elizabeth L., and Parente Stephen T.. 2018. “Returns to Specialization: Evidence from the Outpatient Surgery Market.” Journal of Health Economics, 57: 147–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnich Elizabeth L., Richards Michael R., Whaley Christopher M., and Zhao Xiaoxi. 2020. “Raising the Stakes: Physician Facility Investments and Provider Agency.” RAND Working Paper Series, WR-A621–4, DOI: 10.7249/WRA621-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Eric, Muñoz William, and Wise Leslie. 2010. “National and Surgical Health Care Expenditures, 2005–2025.” Annals of Surgery, 251 (2): 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Syaka, Capps Cory, and Dranove David. 2007. “Patient Admission Patterns and Acquisitions of “Feeder” Hospitals.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16 (4): 995–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Neprash Hannah T., Chernew Michael E., Hicks Andrew L., Gibson Teresa, and McWilliams J. Michael. 2015. “Association of Financial Integration between Physicians and Hospitals with Commercial Health Care Prices.” JAMA Internal Medicine, 175 (12): 1932–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikpay Sayeh S., Richards Michael R., and Penson David. 2018. “Hospital-Physician Consolidation Accelerated in the Past Decade in Cardiology, Oncology.” Health Affairs, 37 (7): 1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short Noel, Marah, and Vivian Ho. 2019. “Weighing the Effects of Vertical Integration versus Market Concentration on Hospital Quality.” Medical Care Research and Review, online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordover Janusz A., Saloner Garth, and Salop Steven C.. 1990. “Equilibrium Vertical Foreclosure.” The American Economic Review, 80 (1): 127–42. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette Ian M., Smink Douglas, and Finlayson Samuel R.G.. 2008. “Outpatient Cholecystectomy at Hospitals Versus Freestanding Ambulatory Surgical Centers.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 206(2): 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters Craig. 2014. “Bargaining Power and the Effects of Joint Negotiation: The ‘Recapture Effect’”. Discussion Paper: Economic Analysis Group of the Antitrust Division, US Department of Justice, Washington DC. Available here: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2014/09/26/308877.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Plotzke Michael and Courtemanche Charles. 2011. “Does Procedure Profitability Impact Whether an Outpatient Surgery is Performed at an Ambulatory Surgery Center or Hospital?” Health Economics, 20(7): 817–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post Brady, Buchmueller Tom, and Ryan Andrew M.. 2018. “Vertical Integration of Hospitals and Physicians: Economic Theory and Empirical Evidence on Spending and Quality.” Medical Care Research and Review, 75 (4): 399–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusen Eric B., Ramseyer J. Mark, and Wiley John S. Jr. 1991. “Naked Exclusion.” American Economic Review, 81 (5): 1137–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Richards Michael R., Nikpay Sayeh S., and Graves John A.. 2016. “The Growing Integration of Physician Practices: With a Medicaid Side Effect.” Medical Care, 54 (7): 714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]