Abstract

Several different reporting biases cited in scientific literature have raised concerns about the overestimation of effects and the subsequent potential impact on the practice of evidence-based medicine and human health. Up to 7–8% of the population experiences neuropathic pain, and established treatment guidelines are based predominately on published, clinical trial results. Therefore, we examined published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of first-line drugs for neuropathic pain and assessed the relative proportions with statistically significant (i.e., positive) and non-significant (i.e., negative) results and their rates of citation. We determined the relationships between reported study outcome and the frequency of their citations with journal impact factor, sample size, time to publication after study completion, and study quality metrics. We also examined the association of study outcome with maximum study drug dosage and conflict of interest. We found that of 107 published RCTs, 68.2% reported a statistically significant outcome regarding drug efficacy for chronic peripheral and central neuropathic pain. Positive studies were cited nearly twice as often as negative studies in the literature (P=0.01), despite similar study sample size, quality metrics, and publication in journals with similar impact factors. The time to publication, journal impact factor, and conflict of interest did not differ statistically between positive and negative studies. Our observations that negative and positive RCTs were published in journals with similar impact at comparable time-lags after study completion are encouraging. However, the citation bias for positive studies could affect the validity and generalization of conclusions in literature and potentially influence clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Several different reporting biases [51] cited in scientific literature have raised concerns about the overestimation of effects and the subsequent potential influence on the practice of evidence-based medicine [7; 12]. Reporting bias refers to the influence of the direction of the results on the dissemination of research findings [5]. Various reporting bias, such as publication bias, outcome reporting bias, and citation bias, have received considerable attention in clinical medicine, including pain [9; 18; 42]. Citation bias occurs when studies with statistically significant results are cited more frequently than those with non-significant results [2; 8; 11]. Reporting bias may result in an over-appraisal of an intervention’s benefit [34] and may impact the results of pooled assessments in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [25; 29; 33; 53].

Reports suggest that publication bias is increasing in current literature. Fanelli [12] found that the frequency of papers indicating positive outcomes from most scientific disciplines increased by more than 20% between 1990 and 2007. Several explanations have been postulated for publication bias, including funding resources, assumed public interest, journal publication policies, and country culture [34]. Similarly, differential citation of positive results, or citation bias, has been reported in several fields and its potential influence on health policy studied [10; 13; 37]. Other related biases include time-lag bias (time from study completion to publication), language bias (favors journals in English), and location bias (results influencing the publication in journals with different levels of indexing) [17].

Although studies of reporting bias are ubiquitous in the biomedical literature, comprehensive studies of reporting bias in the pain field are lacking [9; 42]. We sought to determine whether reporting bias exists in the literature related to chronic neuropathic pain, defined as pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system [14; 23]. Epidemiological studies suggest that 7–8% of the adult population may experience neuropathic pain [54]. Central and peripheral neuropathic pain can result from nerve injuries or diseases. Important causes include lumbar radiculopathy, postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, HIV-related neuropathy, chronic postsurgical pain, post-stroke pain, spinal cord injury, and pain associated with multiple sclerosis. Traditionally, neuropathic pain is treated with several classes of medications, including gabapentin/pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, as monotherapy or in combination. These drugs have been evaluated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have clinically sufficient number needed to treat, and demonstrate tolerable side effect profiles. Evidence-based guidelines have recommended these drugs as first-line therapies for neuropathic pain [14]. We specifically examined if reporting biases were prevalent among medications commonly used for neuropathic pain. Therefore, we studied published RCTs for neuropathic pain with the following goals:

Determine the relationship between published statistically non-significant (negative) and significant (positive) RCTs for each of the drugs recommended as first-line therapy for chronic neuropathic pain and a) impact factor (IF) of journal in which study results were published, b) number of citations of the publication, c) time from study completion to publication, d) study quality metrics, e) maximum dosage of study drug, and f) conflict of interest.

Determine whether an association exists between frequency of citation and the IF of the journal where published, sample size, study quality metrics, and publication year for positive or negative studies.

2. Methods

We included full-text publications of double-blind RCTs that examined the efficacy of recommended first-line pharmacologic therapies for peripheral and central chronic neuropathic pain [14]. We excluded abstracts, case reports, and clinical observations. We assessed studies that included the following pharmacologic treatments: gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, and imipramine administered orally at any dose. Studies allowing breakthrough pain medications, including opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, were also included.

We included studies that identified adult participants aged 18 years or older who had one or more chronic neuropathic pain conditions, classified according to the IASP classification of chronic neuropathic pain for ICD-11 [44]. Conditions included: a) painful cancer-related neuropathy or chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, b) painful HIV neuropathy, c) painful diabetic neuropathy, d) phantom limb pain, e) postherpetic neuralgia, f) postoperative or traumatic neuropathic pain, g) painful polyneuropathy, h) lumbar radiculopathy, i) mixed neuropathic pain, j) spinal cord injury, k) post-stroke pain, and l) pain associated with multiple sclerosis (Appendix 1).

All standard subjective scales for pain intensity were accepted, including visual analog scale, numeric rating scale, brief pain inventory, and verbal descriptor scale. Studies addressing acute neuropathic pain were not considered. We also excluded studies that compared any of the above stated medications with an investigational drug only (i.e., no placebo comparator). If a study tested multiple investigational drugs, we compared the aforementioned medications of interest to the placebo only and excluded any additional experimental drug(s). We excluded studies that tested combination drugs of any of the medications of interest. Studies with administration routes other than oral, including intramuscular, topical, intranasal, rectal, or intravenous, were all excluded. Foreign language studies were excluded if we were unable to obtain an English translation.

We used PubMed as the primary database for the RCTs. Language and publication dates were not restricted. An expert librarian assisted with determining the appropriate search terms. The original search terms included meta-analyses pertaining to the drugs of interest and the clinical indications. The terms “meta-analysis” and “meta-analyses” were paired with the following terms: “AND duloxetine AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND gabapentin AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND pregabalin AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND TCA AND/OR neuropathic pain.” We then identified the RCTs in these studies and reviewed their corresponding reference pages for additional articles that matched our criteria. We also conducted an independent PubMed search of RCTs with the drugs of interest and clinical indications. For this query, the terms “randomized controlled trial” and “RCT” were paired with the following terms: “AND duloxetine AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND gabapentin AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND pregabalin AND/OR neuropathic pain,” “AND TCA AND/OR neuropathic pain.” The terms “pregabalin,” “gabapentin,” duloxetine,” “amitriptyline,” “nortriptyline,” “desipramine,” and “imipramine” were each paired with “painful diabetic neuropathy,” “herpetic neuralgia,” “traumatic neuropathy,” “HIV neuropathy,” “cancer-related neuropathy,” “phantom limb pain,” “post-mastectomy,” “breast cancer,” “taxane,” “vincristine,” “oxaliplatin,” “chemotherapy induced neuropathy,” “spinal cord injury,” “post-stroke pain,” and “multiple sclerosis.”

The RReACT databases [16; 48], which include treatment studies of neuropathic pain taken from various registries around the world, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were also searched for published RCTs [28]. The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was searched if a trial was not registered in clinicaltrials.gov [39].

We determined eligibility by reading the abstract of each study and eliminated those that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Full copies of the remaining articles were then obtained through our institution’s electronic library. Two reviewers read these studies independently and determined those to include based on discussion. The same two reviewers then extracted data independently based on the predetermined study parameters. If the two reviewers disagreed, a third independent reviewer was sourced to reach consensus about the study’s eligibility.

2.1. Proportion of positive and negative studies

For the purpose of this study, all RCTs were classified as either positive (statistical significance favoring the drug of interest) or negative (no statistical significance was achieved for the drug of interest). Designations were made based on the study’s primary outcome.

2.2. Journal IF

Journal IFs were obtained from InCites Journal Citation Reports (JCR) published by Clarivate Analytics. IF data were collected from the time of JCR inception to 2020. The search engine was accessed via our institutional website. The journal within which each RCT was published was determined and the subsequent IF recorded. Two independent reviewers searched for each journal that corresponded to the included RCTs. On the respective journal page, the key indicators for all years were found. The IF selected corresponded to the year of publication for each individual RCT.

2.3. Citations

We obtained the number of citations from both Google Scholar and PubMed. Two independent reviewers accessed each search engine and queried the title of each individual RCT. The number of citations was available on the resulting electronic page. In this manner, we determined the total number of citations as well as average number of citations, calculated as the average number of citations per year starting from the year of publication.

2.4. Time to publication

Two reviewers independently read each RCT and noted study start and completion dates. The time to publication was defined as the difference in years between the study completion date and the year of publication. If the RCT did not report the time period for data collection, we queried the study on clinicaltrials.gov (or the corresponding national database) to collect this information.

2.5. Conflict of interest

To determine conflict of interest, we evaluated each RCT for reported pharmaceutical company funding or provision of study drug, author affiliation, no conflict of interest, or no information reported. Author affiliation was described as any association with organizations that had direct or indirect financial interest in the study matter discussed in the manuscript. Final conflict of interest designations included positive conflict of interest, no conflict of interest, and no information reported. Either pharmaceutical funding or author affiliation was considered a conflict of interest. Two reviewers independently read each RCT and discerned its conflict-of-interest designation.

2.6. Jadad scoring

The Jadad scoring system, or the Oxford Scoring System, is used to assess the methodological quality of RCTs and determine the effectiveness of blinding [21]. The scoring system includes five questions that earn a single point each: a) was the study described as randomized, b) was the study described as double blind, c) was there an explanation of withdrawals and dropouts, d) was the method of randomization described, and e) was the method of blinding described?

Two reviewers independently read each RCT and determined a score between 0 (poor) and 5 (rigorous). Each reviewer was instructed to take no more than 10 minutes reviewing each article. Both reviewers scored each RCT, and the values were averaged.

2.7. Maximum study dosages

Two reviewers independently read each RCT and identified the maximum study dosage delineated by the authors. If divided dosing was described in the trial, the sum total daily dose was determined and used in our assessment.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median or mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All data were subjected to a test of normality (Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogorov-Smirnov), and either parametric (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction) or nonparametric (Mann-Whitney test) analysis was conducted. Drugs were first assessed individually and combined thereafter. Statistical analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). The median absolute deviation (MAD), a robust measure of the spread of a dataset that is non-normal in distribution, was used to detect journal IF outliers [41]. Journals with IFs deviating more than the standard cutoff of 3 were excluded [27]. This cutoff corresponds to an IF value of 10.4, which was rounded to the nearest whole number. The Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease was not found in the JCR database and as such, no IF was obtained for the Simpson et al. publication dated 2001 regarding gabapentin [46]. All other IFs for the journal publications were available and included in the analysis. All tests were two-tailed, and the criterion of statistical significance was a probability less than 5%. We used a linear regression model when assessing correlation between any two variables.

3. Results

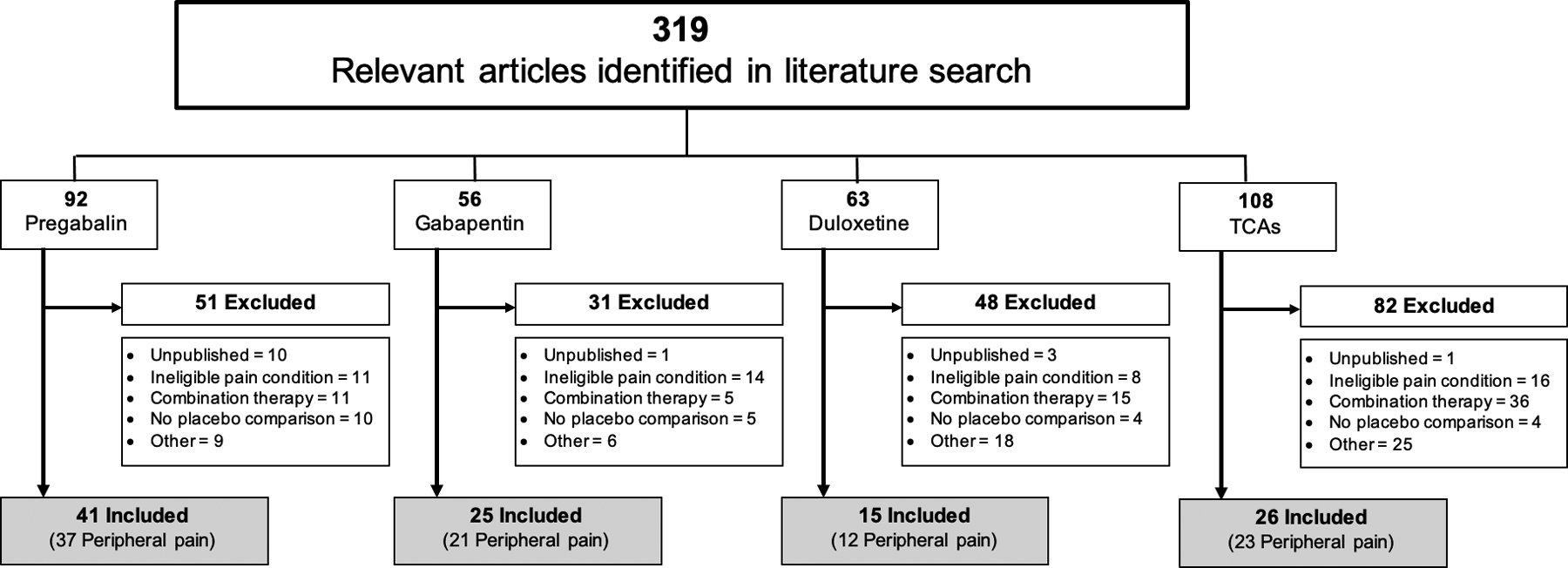

A search of the PubMed database through August 2020 identified 319 potentially relevant studies. Based on the aforementioned inclusion criteria, 212 studies were excluded, and 107 studies were included (41 pregabalin, 25 gabapentin, 15 duloxetine, 26 TCA; Fig. 1). Among the 107 studies, 93 were trials for peripheral neuropathic pain and 14 were trials for central neuropathic pain (see Fig. 1 for details of studies related to each drug).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Other indicates open label, confounding intervention, alternate primary outcome, population does not meet >18 years of age criteria, or non-English publication. NP, neuropathic pain; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

3.1. Proportion of positive and negative studies

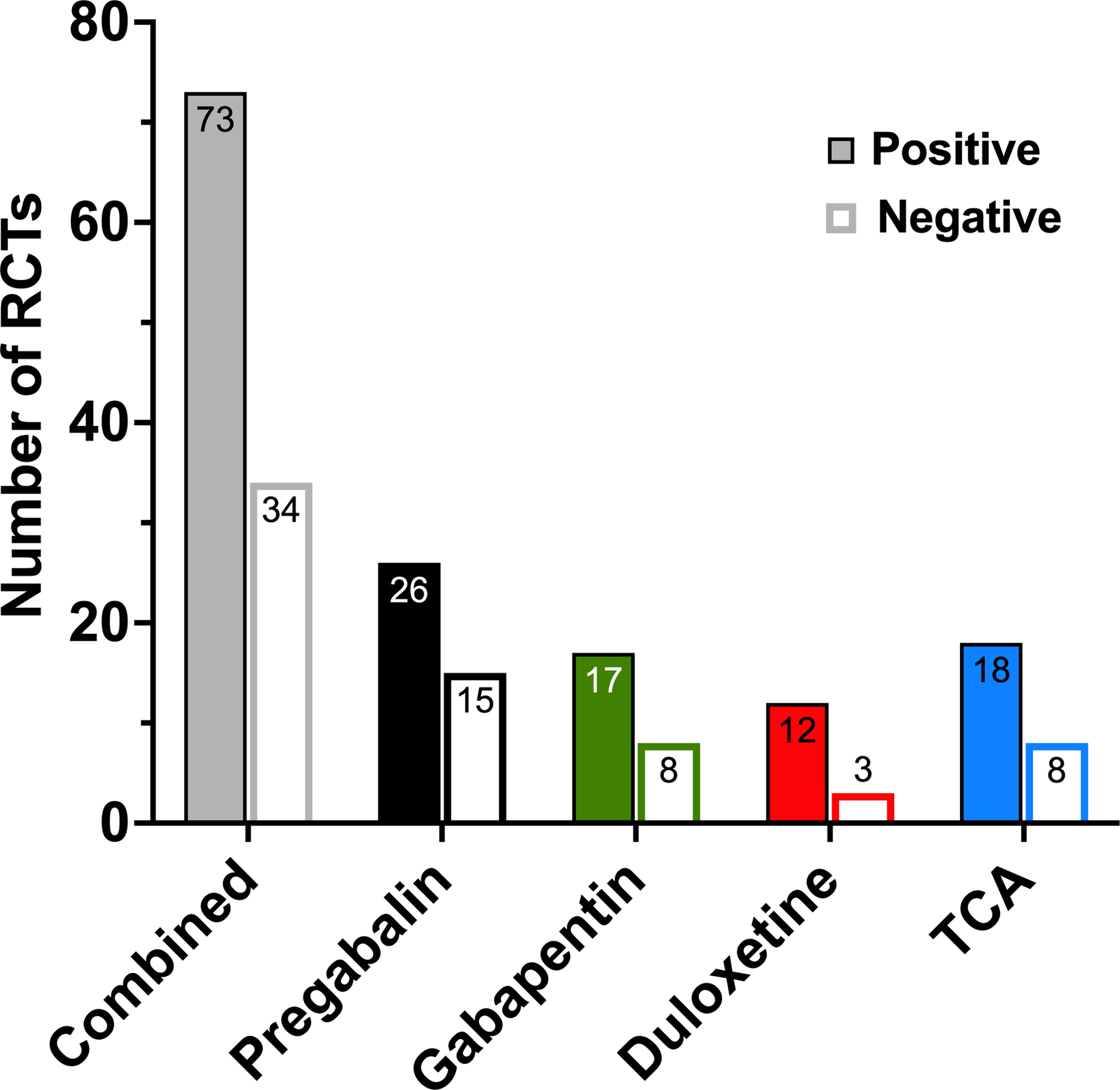

Seventy-three of the 107 evaluated RCTs (68.2%) reported positive outcomes. When we considered each medication or class of medication individually, the percent of positive studies was 63.4% (26/41) for pregabalin, 68% (17/25) for gabapentin, 80% (12/15) for duloxetine, and 69.2% (18/26) for the TCA group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of reported statistically significant and non-significant studies. Positive and negative randomized controlled trials (RCTs) according to drug or drug class. TCA, tricyclic antidepressants.

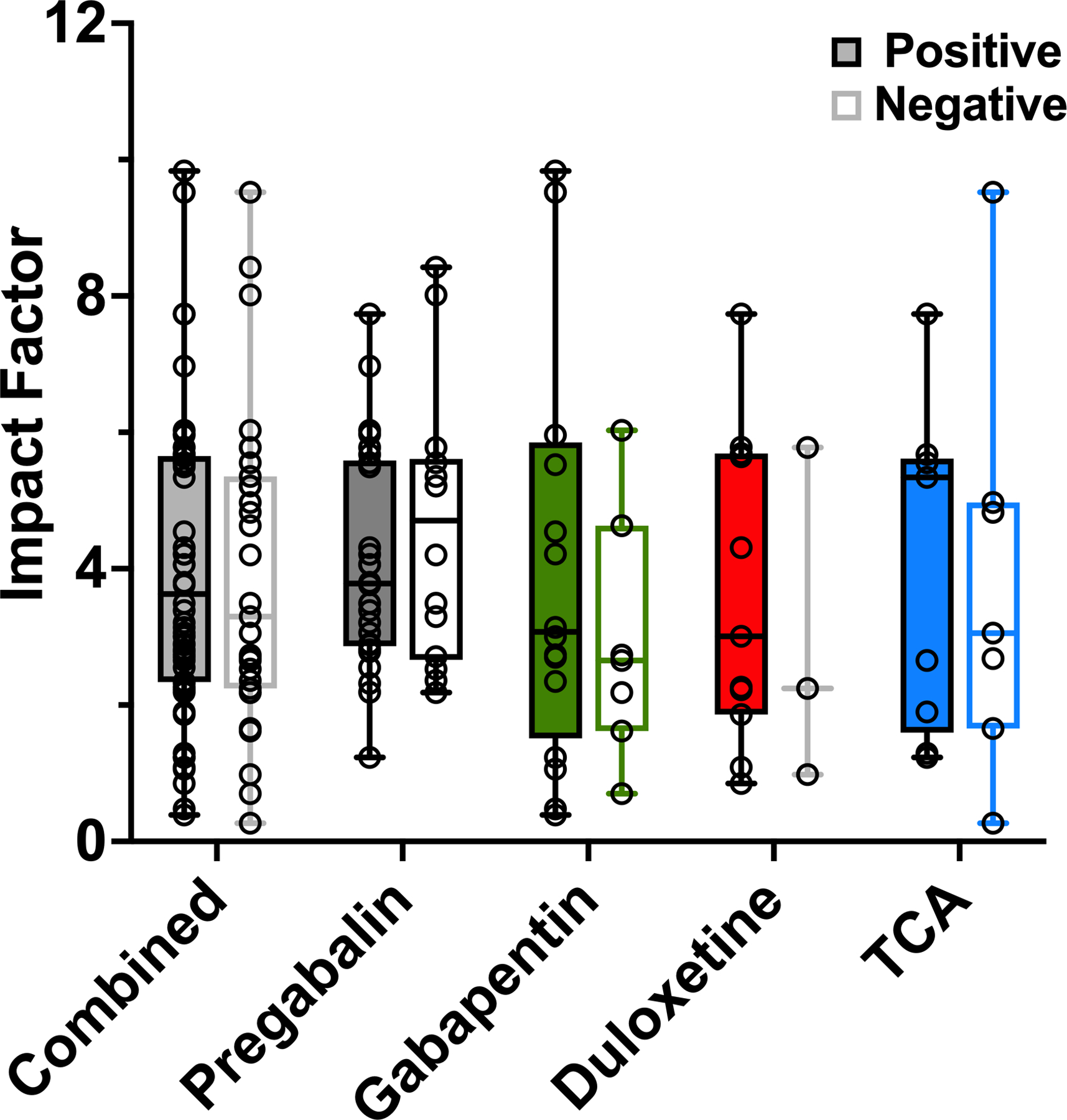

3.2. Journal IF

Collectively, positive studies were published in journals with a mean IF of 4.03 ± 0.28, and negative studies in journals with a mean IF of 3.90 ± 0.41 (P=0.79). Individually, the mean IFs of positive trials for pregabalin, gabapentin, duloxetine, and TCAs were 4.09 ± 0.32, 4.14 ± 0.79, 3.68 ± 0.69, and 4.11 ± 0.79, respectively. The corresponding mean IFs for negative studies were 4.60 ± 0.53, 2.94 ± 0.69, 3.00 ± 1.44, and 3.86 ± 1.13, and did not differ significantly from those of the positive studies (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Impact factor (IF) of journals in which positive and negative randomized controlled trials were published. Positive-outcome and negative-outcome trials and the respective journal IFs are presented, with scatter plot overlay of individual studies. The median absolute deviation technique was used to calculate and exclude outliers. Whiskers reflect the range of values from minimum to maximum IF. Box (hinges) extends from the 25th to 75th percentile. TCA, tricyclic antidepressants.

Among all positive pregabalin RCTs, the highest journal IF was 7.735, whereas the highest journal IF among negative pregabalin RCTs was 79.26. For gabapentin, the highest recorded IF was 9.84 for positive RCTs and 44.02 for negative RCTs. For duloxetine RCTs, the highest IF was 30.39 for positive studies and 2.24 for negative studies. Lastly, for the TCA group, the highest IF for positive studies was 7.74, and the highest IF among the negative studies was 9.52 (Appendix 2).

3.3. Citations

3.3.1. Study outcome and frequency of citations

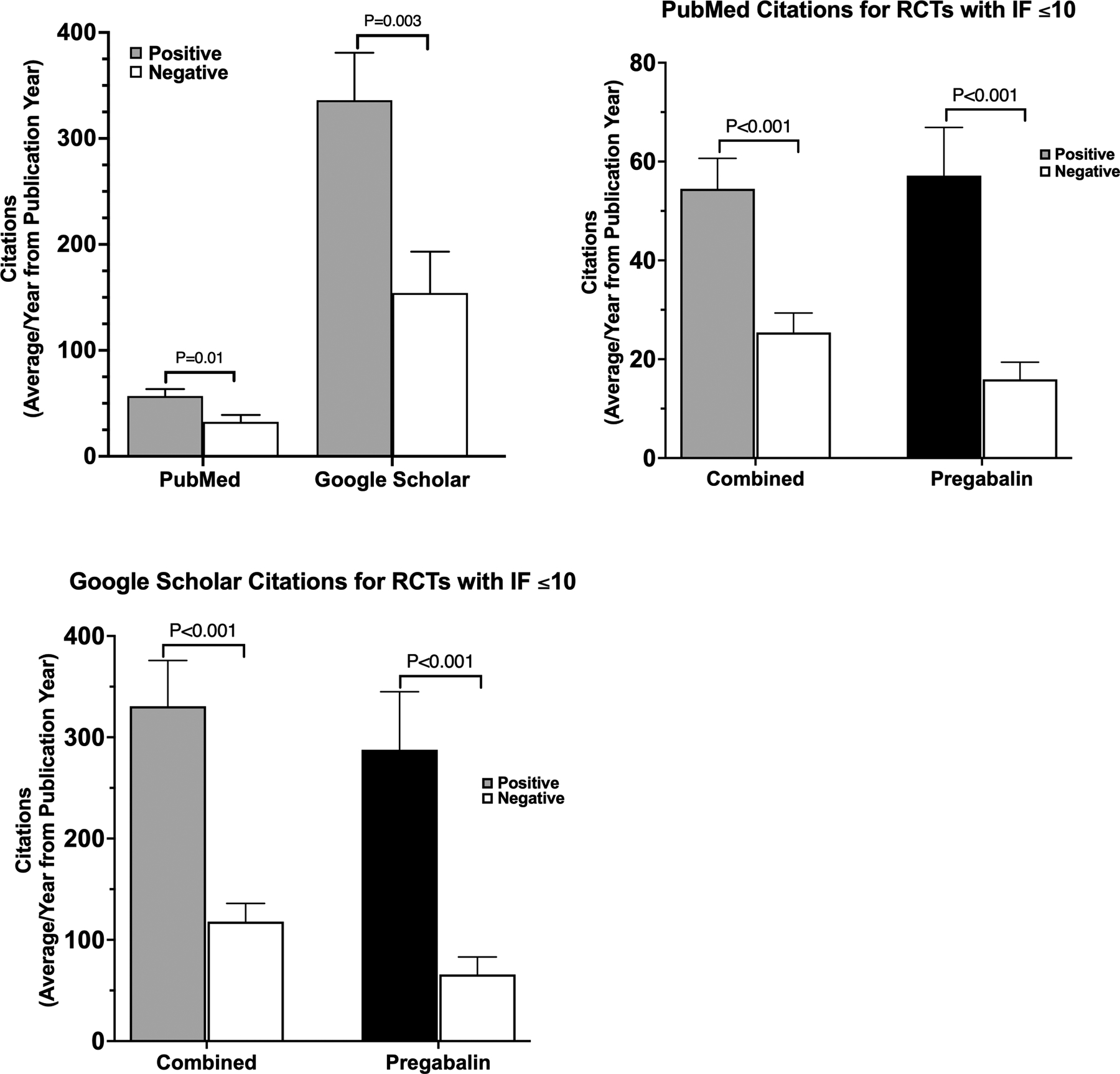

Positive RCTs had a significantly higher average number of citations per year since publication (336.0 ± 44.9 on Google Scholar and 56.9 ± 6.5 on PubMed) than did negative RCTs (154.2 ± 39.0 on Google Scholar [P=0.003] and 32.5 ± 6.6 on PubMed [P=0.01]; Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Citations of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). (A) Average number of PubMed and Google Scholar citations for positive and negative RCTs. Number of PubMed (B) and Google Scholar (C) citations for RCTs published in journals with an impact factor (IF) of ≤10 for all drug trials combined and for pregabalin alone. Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean.

3.3.2. IF and citations

Because outlier publications may have a disproportionate influence on the citations of positive and negative studies, we calculated MAD to identify them. The MAD for IF was found to be 2.55. Accordingly, three RCTs were deemed to be major outliers: Smith 2013 (duloxetine) published in The Journal of the American Medical Association with an IF of 30.387 (deviation of 10.5), Maher 2017 (pregabalin) published in The New England Journal of Medicine with an IF of 79.26 (deviation of 29.7), and Gilron 2005 (gabapentin) also published in The New England Journal of Medicine with an IF of 44.016 (deviation of 15.8) [15; 32; 47]. Hence, we examined the relationship between citations and IF with the exclusion of these three RCTs.

With all drugs combined, our findings showed that for RCTs in journals with an IF ≤10, the number of citations for studies with positive outcomes was significantly higher than the number of citations for studies with negative outcomes. Collectively, positive-outcome RCTs had an average of 54.5 ± 6.2 PubMed citations, whereas negative-outcome RCTs had a significantly lower mean of 25.4 ± 4.0 citations (P<0.001; Fig. 4B). Similarly, for the Google Scholar database, positive-outcome RCTs had a mean of 330.6 ± 45.2 citations, whereas negative-outcome studies had a lower average of 117.9 ± 18.0 citations (P<0.001; Fig. 4C). This effect was also observed with pregabalin-only RCTs, which had the most published studies. Positive pregabalin trials had a significantly higher mean number of citations relative to negative trials (Google Scholar: 287.6 ± 57.3 vs 65.9 ± 17.2, P<0.001; PubMed: 57.2 ± 9.7 vs 15.9 ± 3.5, P<0.001). Although RCTs of other drugs showed a similar trend, the sample sizes were small and lacked the power to determine a statistical significance.

A regression model was used to determine if a relationship (or correlation) exists between number of citations and IF. A significant relationship (P<0.001) was found between positive RCT citations and journal IFs. We did not find a statistically significant relationship in negative RCTs between these variables for any of the first-line drugs used to treat neuropathic pain (Supplemental Fig. 1).

3.3.3. Sample size, quality metrics, and citations

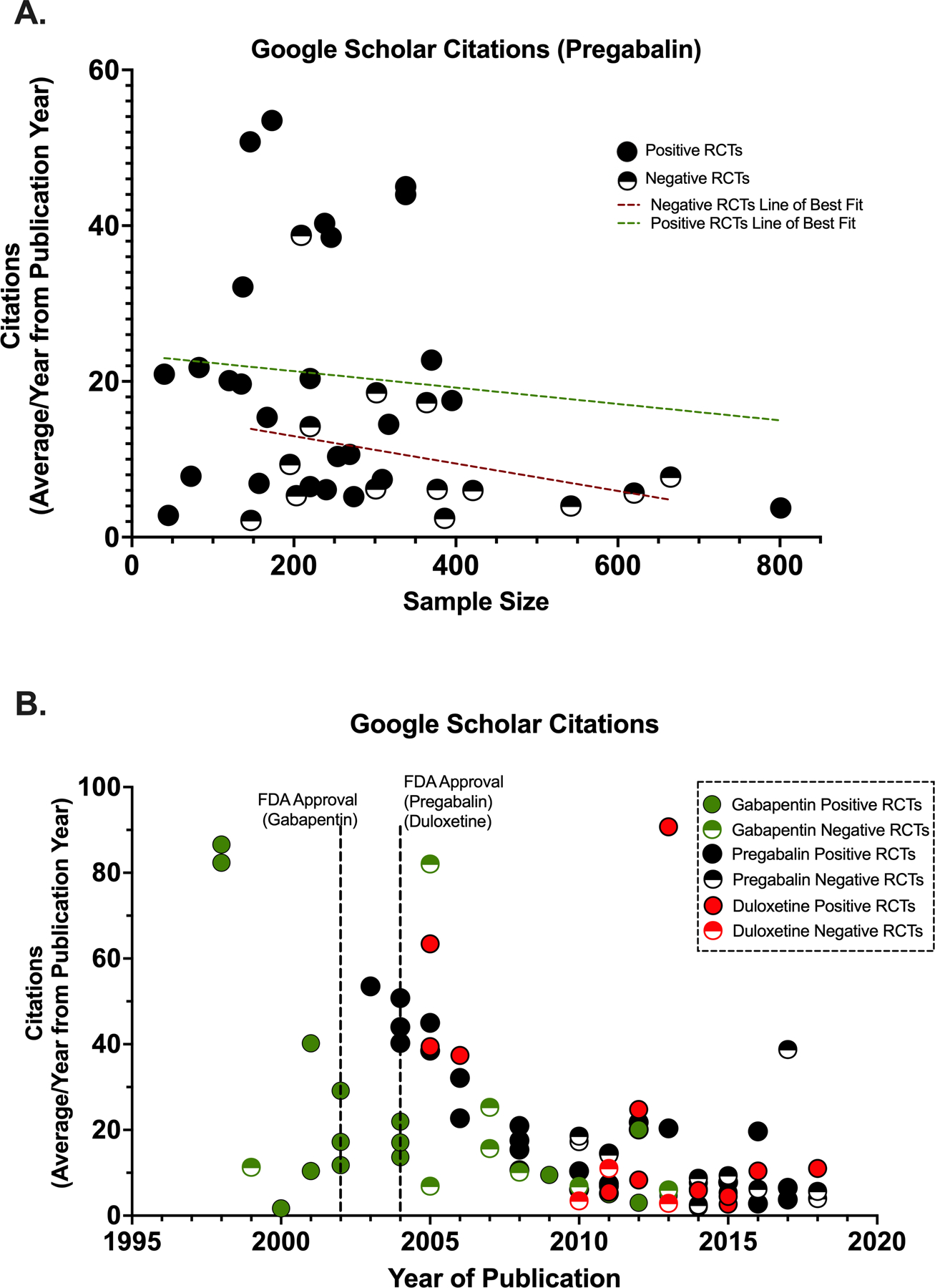

We also used a regression model to assess for a correlation between number of citations and sample size. We did not find a statistically significant relationship between these variables for any of the RCTs included (Supplemental Fig. 2). RCTs of pregabalin predominated among those included in our investigation; therefore, we conducted a separate analysis of pregabalin studies for the aforementioned variables. However, we failed to identify any correlation between sample size and frequency of citation (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Effects of sample size and publication year on citation frequency. (A) Correlation between pregabalin randomized controlled trial (RCT) sample sizes and frequency of citation in Google Scholar from year of publication. (B) Correlation between RCT publication year and frequency of citation in Google Scholar from year of publication. Dashed lines represent best fit.

To determine if the number of citations for the positive and negative RCTs was associated with study quality metrics, we determined the correlation between Jadad score and citation number. The slope of the simple linear regression between average citation number of positive RCTs and the Jadad score was statistically significant (P=0.03). Negative studies failed to demonstrate a significant correlation between these variables (Supplemental Fig. 3).

3.3.4. Year of publication and average citations per year

The average number of Google Scholar citations per year was examined against the year of publication for each RCT. The first positive RCTs published in the years around the FDA approval of the drug trended toward being cited more often than the subsequent positive and negative RCTs (Fig. 5B). Similar findings were observed with citations from the PubMed database. TCAs were not included in this analysis because they are not currently approved by the FDA for neuropathic pain conditions.

3.4. Time-lag Bias

3.4.1. Time to publication

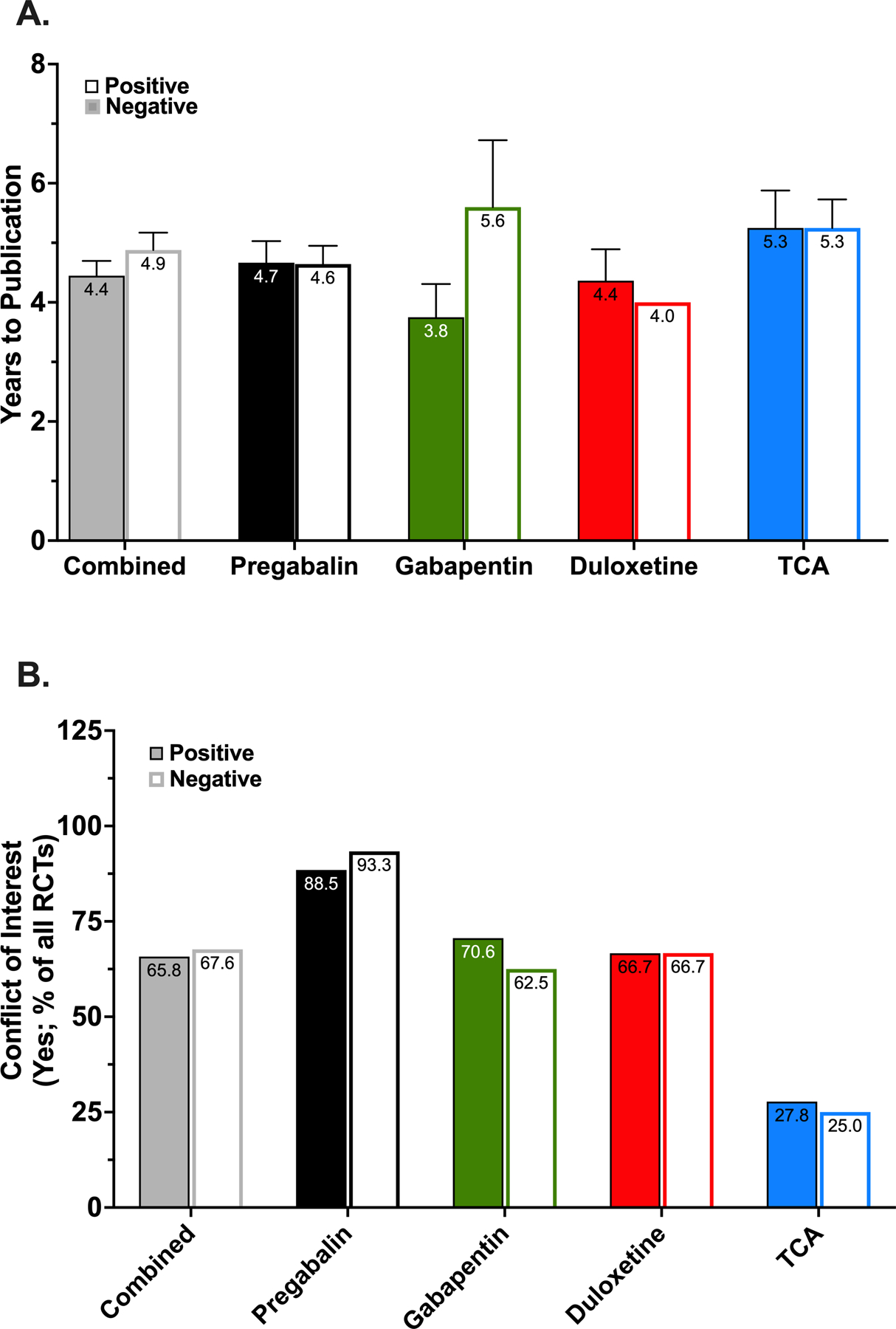

We found no statistically significant difference in the years to publication between studies with positive and negative outcomes. On average, positive-outcome RCTs took 4.45 ± 0.25 years to publish, and negative-outcome RCTs required an average of 4.88 ± 0.29 years (P=0.78; Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Time to publication and conflict of interest in published randomized controlled trials. (A) Association between positive and negative studies and time to publication for each drug or drug class. Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. (B) Percentage of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for each drug or drug class with positive and negative outcomes that reported a conflict of interest. TCA, tricyclic antidepressants.

3.4.2. Years to publication and sample size

A secondary outcome assessed was the relationship between years to publication and sample size. We did not observe a statistically significant correlation between sample size (positive-outcome studies, N = 227.0 ± 23.9; negative-outcome studies, N = 271.0 ± 36.2, P=0.46) and number of years to publication for studies with positive (r2 = 4.4×10−4, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −34.43 to 30.40) or negative (r2 = 4.2×10−5, CI = −54.11 to 55.72) outcomes (Supplemental Fig. 4).

3.5. Conflict of interest

Of the 107 publications evaluated in this study, 71 (66.3%) disclosed a conflict of interest (pharmaceutical funding and/or author affiliation). Of these 71 studies, 48 (67.6%) were from the positive-outcome group and 23 (32.4%) from the negative-outcome group (P=0.003). Of the 48 positive RCTs, 23 were specific to pregabalin, 12 to gabapentin, 8 to duloxetine, and 5 to TCAs. Of the 23 negative RCTs with reported conflicts, 14 were for pregabalin, 5 for gabapentin, 2 for duloxetine, and 2 for TCA. No statistically significant differences were observed (Fig. 6B).

For those studies in which a conflict of interest was indicated, we assessed the difference in time to publication, amongst both positive and negative RCTs, for studies published within 5 years of FDA approval versus those published after this time. For pregabalin and duloxetine (approved in 2004), the time to publication of positive RCTs published between 2004–2009 (pregabalin: 3 years, n=10); duloxetine: 2.5 years, n=3) did not differ from those published in or after 2010 (pregabalin, 2.78 years, n=13; duloxetine, 2.5 years, n=7). There were no negative pregabalin or duloxetine studies published between 2004–2009. For gabapentin (approved in 2002), both positive and negative studies published between 2002–2007 demonstrated a tendency to be published in a shorter duration after study completion (positive: 1.5 years, n=8; negative: 2 years, n=4) as compared to RCTs published in or after 2008 (positive: 4.5 years, n=6; negative: 4.67 years, n=3).

3.6. Jadad scoring

Jadad scoring revealed similar study quality scores across all drugs, irrespective of study outcome (positive = 4.4 ± 0.1, negative = 4.5 ± 0.1; P=0.39). For pregabalin RCTs, positive-outcome studies averaged a score of 4.5 ± 0.1 whereas negative-outcome studies averaged a score of 4.5 ± 0.2 (P=0.82). For gabapentin, positive RCTs had an average score of 4.6 ± 0.2, relative to negative RCTs, which had an average score of 4.5 ± 0.4 (P=0.74). For duloxetine, positive RCTs scored an average of 3.8 ± 0.2, whereas negative RCTs scored an average of 4.7 ± 0.3 (P=0.11). For TCA studies, positive-outcome RCTs averaged a Jadad score of 4.3 ± 0.2 while negative-outcome studies had an average score of 4.4 ± 0.3 (P=0.76; Supplemental Fig. 5).

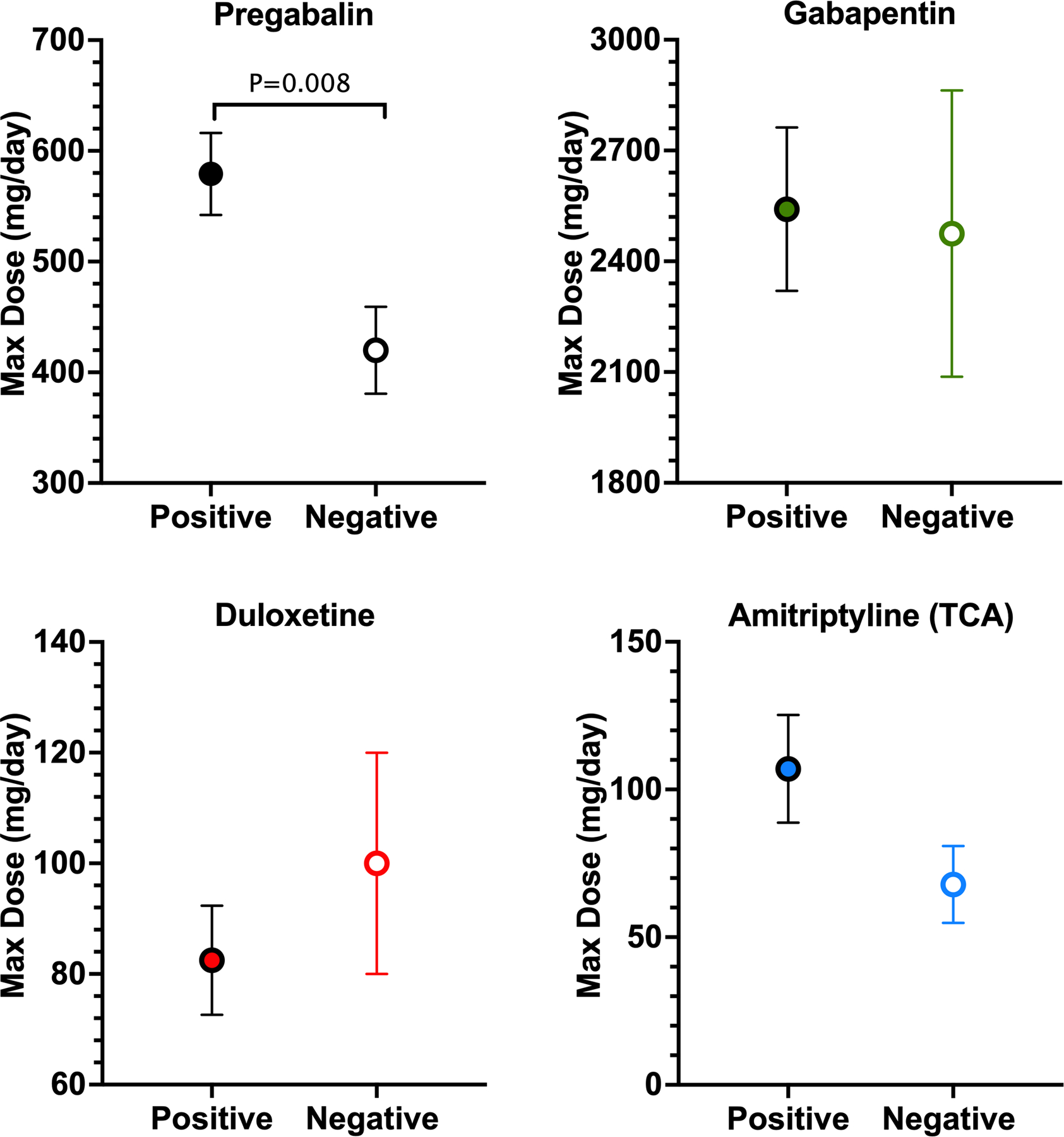

3.7. Maximum study dosages

For studies involving pregabalin, the mean maximum dose used was significantly higher for RCTs that reported a positive outcome than for RCTs that reported a negative outcome (P=0.008). No difference was found in mean maximum doses for gabapentin (P=0.93), duloxetine (P=0.63), or TCAs (P=0.10; Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Association between positive and negative studies and maximum drug dose used. Mean maximum dose used in studies that reported positive and negative outcomes for pregabalin, gabapentin, duloxetine, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA). Amitriptyline was chosen as the representative TCA sample because it had the most RCTs. Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean.

4. Discussion

Among drugs recommended for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain, positive RCTs comprise a greater proportion of the published literature than negative RCTs (Appendix 3). Positive studies were cited more often than negative studies, despite similar quality metrics, sample size, and publication in journals with similar IFs. The average citation number per year of positive RCTs correlated with the journal IF and the quality metric. In contrast, negative studies failed to demonstrate a significant correlation between these variables. Time to publication, sample size, and frequency of reported conflict of interest did not differ significantly between positive and negative studies.

4.1. Publication of positive and negative studies

4.1.1. Study outcome and frequency of citations

Negative neuropathic pain RCTs were cited less frequently than positive studies. On average, positive-outcome studies were cited in PubMed and Google Scholar about twice as often as negative studies for all therapies combined, and four to five times more frequently for pregabalin alone. These results are consistent with observations in recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of citation bias across scientific disciplines [10; 13]. The large discrepancy in number of citations between PubMed and Google Scholar may be explained by the sources used in each respective search engine. PubMed retrieves published literature from biomedical journals only, whereas Google Scholar includes literature from books, reports, theses, preprints, and journals and spans a larger range of disciplines.

4.1.2. Journal IF

Our study suggests that location bias is not evident in the chronic neuropathic pain literature. Our observations are similar to earlier reports that also showed no difference in median IF values between positive and negative trials [30; 52].

4.1.3. Time to publication

A time-lag bias for publication of negative studies has been recognized in the literature [19; 50]. Suñé et al. [52] prospectively followed all clinical drug trials approved by one hospital’s ethics committee and determined rate and time to publication based on publication status and direction of outcome. They found that positive outcomes had a shorter time to publication than negative outcomes. In contrast, our data did not reveal a time-lag bias. We also examined if study sample size predicted the time to publication. Our postulate that studies with a larger sample size would be published more quickly was not supported by our findings. In addition, our data did not support the hypothesis that larger, multi-center studies would be funded by industry and take less time to publish. As suggested by Jefferson et al. [22], our findings may reflect the impact of initiatives such as the AllTrials campaign, which advocates for all clinical trials to be registered and reported, regardless of outcome.

4.1.4. Maximum study dosages

We hypothesized that low experimental drug doses might explain the lack of effect in negative-outcome studies. Consistent with previous reviews showing a clear dose-response relationship, we identified a significant difference in the maximum dose between positive- and negative-outcome RCTs of pregabalin [45]. No such relationship was observed for the other drugs. Interestingly, patients with either painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy or HIV neuropathy accounted for more than half of all negative RCTs (Appendix 2). These two conditions account for 10 of the 14 negative pregabalin RCTs and all negative duloxetine studies.

4.1.5. Conflict of interest and Study Quality Metrics

Several reports and systematic reviews suggest that industry-sponsored drug studies are more likely to report favorable outcomes than are trials funded from other sources [3; 4; 26; 31]. We observed that among the studies that reported a conflict of interest, a significantly higher proportion were positive than negative. The evidence fails to indicate that this observation is a result of poor research quality of the negative studies, but more likely a result of data interpretation [19; 36]. Notably, similar to reports in other fields, 31% of the studies included in our analysis either did not report a conflict of interest or reported no conflict [24].

4.2. Factors that may influence the frequency of positive study citation

Several potential factors, such as study quality and sample size, could contribute to our finding that positive studies are cited more frequently than negative studies. Indeed, sample size is positively correlated with statistical power, when level of factors such as type I error, variance, and minimum detectable difference are comparable. However, we failed to demonstrate a significant relationship between sample size and citation number for positive or negative studies. Moreover, we failed to find a consistent difference in the Jadad scores of positive and negative studies, and previous systematic reviews have failed to demonstrate an association between citation frequency and research quality [1; 10; 38]. In addition, the mean IF for publications of positive and negative RCTs did not differ and no correlation between IF and average citations was observed.

A trend that we observed was that positive studies published in the initial years around the FDA approval of a drug were cited more frequently than subsequent studies. Negative and positive reports published six or more years after FDA approval were cited similarly. The data examined within these findings are unable to assess whether marketing efforts by pharmaceutical companies around the time of the drug approval influences the citation. For example, reports based on internal company documents (Pfizer and Parke-Davis), which include marketing assessments and email correspondence related to gabapentin, suggest that the company appears to have exerted control over the message delivered in published clinical trial results and selected where and when trial findings would be presented or published [56; 57].

4.3. Strategies to minimize reporting biases

Biases in the reporting of RCTs may have serious consequences in clinical practice as a result of over-interpretation of the conclusions from published literature [10; 14; 20]. Song et al. [49] recommended that systematic reviews and meta-analyses include published and unpublished trials to minimize the effects of publication bias on overall conclusions and magnitude of expected effects. This strategy is exemplified in the recent systematic review of drug treatments for neuropathic pain that included studies published in peer-reviewed journals and unpublished trials retrieved from ClinicalTrials.gov and pharmaceutical companies’ websites [14]. The authors observed that nearly 10% of trials were not published in peer-reviewed journals and that published studies reported greater effects than unpublished studies (OR=2.2, 95% CI=1.5–3.0). The mandate for prospective registration of clinical trials and the reporting of outcomes by most reputed journals helps to reduce dissemination bias in clinical research. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the biases observed in the presented findings do not refer to biases within the trials themselves, but rather to the publication and subsequent dissemination of their findings.

4.4. Limitations of our study

It is difficult to determine from our observations of an increased proportion of positive studies whether a reporting bias exists for neuropathic pain trials as we did not search the grey literature. Moreover, the challenges of creating a global database of all RCTs for multiple chronic pain states from the numerous trial registries have been highlighted in earlier reports [35]. Meta-analysis and evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of neuropathic pain indicate a higher proportion of published positive RCTs with statistically significant outcomes for gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine, and TCAs. However, previous reports indicate that the published literature represents only a fraction of all clinical studies conducted, with about half of completed studies reported within 4–5 years of completion [6]. Studies with positive results were more than twice as likely to be published than those with negative results [11; 43]. Many non-significant results go unpublished because investigators believe they have little prospect for publication, and not necessarily because journal editors evaluate them unfavorably [8].

Evidence for study publication bias, outcome reporting bias, and the practice of recasting negative results as positive have been reported for FDA-approved drugs, including gabapentin and antidepressants [40; 55; 57]. Similarly, considerable discrepancies between registered primary outcomes of analgesic clinical trials and outcomes reported in publications have been described [48].

Other limitations of our study include the heterogeneous etiology of neuropathic pain and the multiplicity of medications used for each pain condition. Many of these studies included multiple pain conditions within or between participants. Consequently, assessment of drug efficacy and effectiveness may be inaccurate. Our evaluation of varied RCTs necessitates cautious interpretation of the data and warrants additional research involving targeted patient populations and pain syndromes.

Our study of peripheral and central neuropathic pain trials illustrates some positive trends but reveals a citation bias. Well-conducted positive and negative studies are published in journals of equal impact without a significant time-lag bias. However, an unexplained citation bias exists in the literature pertaining to neuropathic pain wherein positive studies are cited more frequently than negative studies. Additional studies are warranted to determine the factors that contribute to this bias and its impact on clinical management of neuropathic pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Claire Levine, MS, ELS, scientific editor in the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, for her assistance in editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NS26363). SNR is a consultant for Allergan, Bayer, Aptinyx, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and is a co-investigator in a grant from Medtronic, Inc. NBF has received consultancy fees from Merck, Almirall, NeuroPN, Vertex, and Novartis Pharma, and has undertaken consultancy work for Aarhus University with remunerated work for Biogen, Merz, and Confo Therapeutics. She has received grants from IMI2PainCare, an EU IMI 2 (Innovative medicines initiative) public-private consortium and the companies involved are: Grunenthal, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Esteve, and Teva. SS and AB declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- [1].Akcan D, Axelsson S, Bergh C, Davidson T, Rosén M. Methodological quality in clinical trials and bibliometric indicators: no evidence of correlations. Scientometrics 2013;96(1):297–303. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Begg CB, Berlin JA. Publication Bias: A Problem in Interpreting Medical Data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A (Statistics in Society) 1988;151(3):419–463. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. Jama 2003;289(4):454–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bero L Industry sponsorship and research outcome: a Cochrane review. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(7):580–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boutron IPM, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hróbjartsson A. Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 62 (updated February 2021) Update 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, Krumholz HM, Ghersi D, van der Worp HB. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014;383(9913):257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dickersin K, Chalmers I. Recognizing, investigating and dealing with incomplete and biased reporting of clinical research: from Francis Bacon to the WHO. J R Soc Med 2011;104(12):532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dickersin K, Chan S, Chalmers TC, Sacks HS, Smith H Jr. Publication bias and clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1987;8(4):343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dufka FL, Munch T, Dworkin RH, Rowbotham MC. Results availability for analgesic device, complex regional pain syndrome, and post-stroke pain trials: comparing the RReADS, RReACT, and RReMiT databases. Pain 2015;156(1):72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Duyx B, Urlings MJE, Swaen GMH, Bouter LM, Zeegers MP. Scientific citations favor positive results: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;88:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337(8746):867–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fanelli D Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics 2012;90(3):891–904. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fanelli D Positive results receive more citations, but only in some disciplines. Scientometrics 2013;94(2):701–709. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Weaver DF, Houlden RL. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med 2005;352(13):1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Greene K, Dworkin RH, Rowbotham MC. A snapshot and scorecard for analgesic clinical trials for chronic pain: the RReACT database. Pain 2012;153(9):1794–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, VA W. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1. Cochrane, 2020.

- [18].Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ, Oxman AD, Dickersin K. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009(1):Mr000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ioannidis JP. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. Jama 1998;279(4):281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ioannidis JP. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q 2016;94(3):485–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jefferson L, Fairhurst C, Cooper E, Hewitt C, Torgerson T, Cook L, Tharmanathan P, Cockayne S, Torgerson D. No difference found in time to publication by statistical significance of trial results: a methodological review. JRSM Open 2016;7(10):2054270416649283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice ASC, Treede RD. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain 2011;152(10):2204–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Joksimovic L, Koucheki R, Popovic M, Ahmed Y, Schlenker MB, Ahmed IIK. Risk of bias assessment of randomised controlled trials in high-impact ophthalmology journals and general medical journals: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101(10):1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kicinski M, Springate DA, Kontopantelis E. Publication bias in meta-analyses from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Stat Med 2015;34(20):2781–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. Bmj 2003;326(7400):1167–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Leys C, Ley C, Klein O, Bernard P, Licata L. Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2013;49(4):764–766. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Library C. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

- [29].Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2018;74(3):785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Littner Y, Mimouni FB, Dollberg S, Mandel D. Negative Results and Impact Factor: A Lesson From Neonatology. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2005;159(11):1036–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:Mr000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Maher CG, Lin CWC, Mathieson S. Trial of Pregabalin for Acute and Chronic Sciatica. N Engl J Med 2017;376(24):2396–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mayo-Wilson E, Li T, Fusco N, Bertizzolo L, Canner JK, Cowley T, Doshi P, Ehmsen J, Gresham G, Guo N, Haythornthwaite JA, Heyward J, Hong H, Pham D, Payne JL, Rosman L, Stuart EA, Suarez-Cuervo C, Tolbert E, Twose C, Vedula S, Dickersin K. Cherry-picking by trialists and meta-analysts can drive conclusions about intervention efficacy. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;91:95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Montori VM, Smieja M, Guyatt GH. Publication bias: a brief review for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75(12):1284–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Munch T, Dufka FL, Greene K, Smith SM, Dworkin RH, Rowbotham MC. RReACT goes global: perils and pitfalls of constructing a global open-access database of registered analgesic clinical trials and trial results. Pain 2014;155(7):1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Naci H, Ioannidis JP. How good is “evidence” from clinical studies of drug effects and why might such evidence fail in the prediction of the clinical utility of drugs? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2015;55:169–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Newson R, Rychetnik L, King L, Milat A, Bauman A. Does citation matter? Research citation in policy documents as an indicator of research impact - an Australian obesity policy case-study. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nieminen P, Carpenter J, Rucker G, Schumacher M. The relationship between quality of research and citation frequency. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2006;6(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Organization WH. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

- [40].Roest AM, de Jonge P, Williams CD, de Vries YA, Schoevers RA, Turner EH. Reporting Bias in Clinical Trials Investigating the Efficacy of Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders: A Report of 2 Meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(5):500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rousseeuw PJ, Hubert M. Robust statistics for outlier detection. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2011;1(1):73–79. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rowbotham MC. The impact of selective publication on clinical research in pain. Pain 2008;140(3):401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Scholz J, Finnerup NB, Attal N, Aziz Q, Baron R, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Cruccu G, Davis KD, Evers S, First M, Giamberardino MA, Hansson P, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Nurmikko T, Perrot S, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rowbotham MC, Schug S, Simpson DM, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ, Barke A, Rief W, Treede RD. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic neuropathic pain. Pain 2019;160(1):53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Scholz J, Finnerup NB, Attal N, Aziz Q, Baron R, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Cruccu G, Davis KD, Evers S, First M, Giamberardino MA, Hansson P, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Nurmikko T, Perrot S, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rowbotham MC, Schug S, Simpson DM, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ, Barke A, Rief W, Treede RD, Classification Committee of the Neuropathic Pain Special Interest G. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic neuropathic pain. Pain 2019;160(1):53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Serpell M, Latymer M, Almas M, Ortiz M, Parsons B, Prieto R. Neuropathic pain responds better to increased doses of pregabalin: an in-depth analysis of flexible-dose clinical trials. Journal of pain research 2017;10:1769–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Simpson DA. Gabapentin and venlafaxine for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2001;3(2):53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, Fleishman S, Paskett ED, Ahles T, Bressler LR, Fadul CE, Knox C, Le-Lindqwister N, Gilman PB, Shapiro CL. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2013;309(13):1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Smith SM, Wang AT, Pereira A, Chang DR, McKeown A, Greene K, Rowbotham MC, Burke LB, Coplan P, Gilron I, Hertz SH, Katz NP, Lin AH, McDermott MP, Papadopoulos EJ, Rappaport BA, Sweeney M, Turk DC, Dworkin RH. Discrepancies between registered and published primary outcome specifications in analgesic trials: ACTTION systematic review and recommendations. Pain 2013;154(12):2769–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, Loke YK, Ryder J, Sutton AJ, Hing C, Kwok CS, Pang C, Harvey I. Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14(8):iii, ix–xi, 1–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ 1997;315(7109):640–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sterne JACEM, Moher D, Boutron I (editors). Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston MS (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 520 (updated June 2017) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Suñé P, Suñé JM, Montoro JB. Positive outcomes influence the rate and time to publication, but not the impact factor of publications of clinical trial results. PLoS One 2013;8(1):e54583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. Bmj 2000;320(7249):1574–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain 2014;155(4):654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Vedula SS, Bero L, Scherer RW, Dickersin K. Outcome reporting in industry-sponsored trials of gabapentin for off-label use. N Engl J Med 2009;361(20):1963–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vedula SS, Goldman PS, Rona IJ, Greene TM, Dickersin K. Implementation of a publication strategy in the context of reporting biases. A case study based on new documents from Neurontin® litigation. Trials 2012;13(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vedula SS, Li T, Dickersin K. Differences in Reporting of Analyses in Internal Company Documents Versus Published Trial Reports: Comparisons in Industry-Sponsored Trials in Off-Label Uses of Gabapentin. PLOS Medicine 2013;10(1):e1001378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.