INTRODUCTION

The Medicare Advantage (MA) program now enrolls over 34% of all Medicare Beneficiaries 1. MA contracts may define provider networks, while the TM program does not restrict access to any provider. While setting narrow networks may help a plan control costs, MA enrollees are more likely to receive care from lower quality providers compared to TM,2 which may be driven in part by network design. Research on MA networks has been restricted to a limited number of markets or states or to a single specialty.3,4 National data across multiple specialties are lacking.

METHODS

We used 2019 MA provider network files from Vericred, a company that compiles and maintains network data for MA nationally.5 We linked the network data to publicly available MA service area, contract, and enrollment data. To compare MA networks to the overall supply of providers, we used a 20% random sample of Medicare Part B carrier claims from 2017 to identify providers who treated at least one TM enrollee. We linked these providers to their primary office location in the NPI database. We aggregated the counts of providers included within each contract’s network and the total number of providers in that service area and calculated the percent of providers of a given specialty in a contract’s service area that were included in network. We defined narrow networks as less than 25% of available providers included in network5, and used univariate regression to compare contract and enrollee characteristics by breadth.

RESULTS

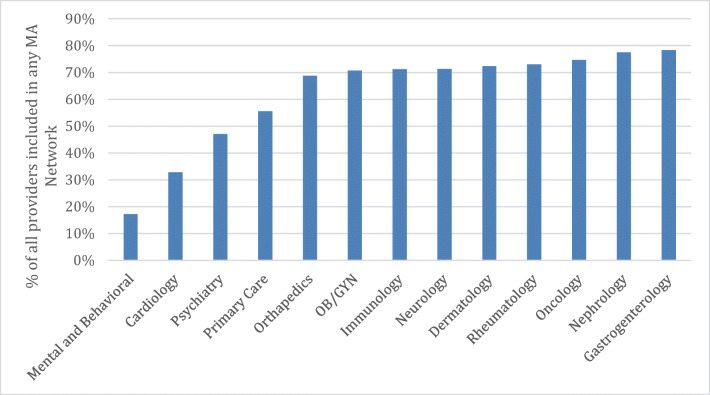

Our sample of 421 contracts accounted for 20,401,060 enrollees, or 89.2% of MA enrollees in 2019. When comparing the proportion of providers included in at least one network, we find that 18.2% of mental health professionals, 34.4% of cardiologists, 50.0% of psychiatrists, and 57.9% of primary care providers were included in at least one MA contract’s network (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percent of providers included in any Medicare Advantage network by specialty type. Notes: Each bar represents the percentage of providers that see any Traditional Medicare enrollee based on carrier claims that are included in at least one MA network. Provider specialties are defined by taxonomy codes. Mental and Behavioral includes providers such as counselors, psychologists, and social workers and does not include psychiatrists. Primary Care includes geriatricians. Pediatricians and pediatric specialists are excluded from each classification. Providers include individual MDs, NPs, PA’s, psychologists, and others who are required to register for an NPI.

In general, for-profit contracts with higher premiums, higher enrollment, and higher market share tended to have wider networks (Table 1). Higher quality contracts had narrower networks (20% in 2–2.5-star and 23.6% in 3–3.5-star contracts had a narrow primary care network compared to 50.1% of enrollees in 5-star contracts). Hispanic and Asian enrollees were more frequently enrolled in narrow networks.

Table 1.

Narrow Networks by Contract and Enrollee Characteristics

| Primary Care | Psychiatry | Mental and Behavioral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plan characteristics | % Narrow | p value | % Narrow | p value | % Narrow | p value |

| % Enrollees | 30.5% | 43.1% | 83.2% | |||

| Type | ||||||

| HMO | 32.6 | 37.3 | 87.9 | |||

| PPO | 27.9 | 0.327 | 50.2 | 0.013 | 77.3 | 0.006 |

| Star rating | ||||||

| 2–2.5 | 20.0 | 62.0 | 91.2 | |||

| 3–3.5 | 23.6 | 0.952 | 29.6 | 0.608 | 84.6 | 0.89 |

| 4–4.5 | 32.3 | 0.834 | 47.3 | 0.816 | 84.0 | 0.88 |

| 5 | 50.1 | 0.624 | 50.1 | 0.856 | 50.8 | 0.415 |

| Unrated | 30.9 | 0.858 | 47.7 | 0.826 | 69.2 | 0.654 |

| Premium | ||||||

| < $10 | 31.9 | 35.6 | 86.9 | |||

| $10 to $40 | 31.1 | 0.879 | 51.3 | 0.016 | 82.4 | 0.358 |

| > $40 | 27.9 | 0.643 | 32.8 | 0.762 | 80.6 | 0.381 |

| Enrollment | ||||||

| Small (< 3000) | 47.1 | 48.8 | 79.5 | |||

| Medium (3000 to 20,000) | 34.4 | 0.83 | 38.5 | 0.948 | 76.2 | 0.923 |

| Large (> 20,000) | 39.4 | 0.702 | 43.2 | 0.95 | 83.3 | 0.689 |

| Contract age | ||||||

| Prior to 2006 | 32.7 | 39.3 | 79.4 | |||

| 2006–2013 | 25.3 | 0.156 | 50.9 | 0.039 | 95.2 | <0.001 |

| 2014–2019 | 35.0 | 0.808 | 41.3 | 0.847 | 61.5 | 0.019 |

| National | ||||||

| Single State | 36.5 | 43.5 | 83.8 | |||

| Multiple States | 26.7 | 0.045 | 42.8 | 0.902 | 82.7 | 0.789 |

| Profit | ||||||

| Non-profit | 42.2 | 43.2 | 95.2 | |||

| For-profit | 28.4 | 0.036 | 43.1 | 0.989 | 81.0 | 0.008 |

| Provider integration | ||||||

| Non-integrated | 30.5 | 43.1 | 83.2 | |||

| Integrated health system | 87.8 | < 0.001 | 89.4 | < 0.001 | 99.8 | < 0.001 |

| Contract penetration | ||||||

| 2.7 to 8.0% | 49.9 | 51 | 87.4 | |||

| 8.0 to 11.0% | 33.5 | 0.007 | 66.6 | 0.011 | 94.7 | 0.095 |

| 11.0 to 23.5% | 19.1 | < 0.001 | 29 | 0.001 | 96.2 | 0.063 |

| > 23.5% | 12.3 | < 0.001 | 11.6 | < 0.001 | 44.5 | < 0.001 |

| Primary Care | Psychiatry | Mental and Behavioral | ||||

| Enrollee characteristics | % Narrow | p value | % Narrow | p value | % Narrow | p value |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 22.8 | 32.3 | 79.4 | |||

| Black | 21.7 | 0.764 | 29.4 | 0.475 | 80.8 | 0.623 |

| Hispanic | 39.7 | 0.007 | 47.7 | 0.026 | 86.2 | 0.325 |

| Asian | 34.7 | 0.054 | 46.3 | 0.039 | 90.2 | 0.036 |

| NA/AI | 28.1 | 0.302 | 36.4 | 0.471 | 81.1 | 0.744 |

| Other | 26.5 | 0.037 | 36.8 | 0.042 | 83.9 | 0.02 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 25.7 | 34.8 | 81.29 | |||

| Male | 25.1 | 0.133 | 34.2 | 0.238 | 80.68 | 0.401 |

| Age | ||||||

| Under 65 | 25.4 | 35.5 | 80.8 | |||

| Over 65 | 24.8 | 0.828 | 28.3 | 0.036 | 91.6 | 0.89 |

| Dual eligibility | ||||||

| Not dual | 23.8 | 34.9 | 79.8 | |||

| Dual | 30.9 | 0.106 | 32.9 | 0.716 | 85.3 | 0.414 |

Percentages are row percentages and represent the % of enrollees in a contract of a given type that are in a narrow network. Narrow networks are defined as those that include less than 25% of available providers of a type in a given contracts service area. Only HMOs and PPOs are included in this analysis. p values are calculated using univariate regressions. Provider specialties are defined by taxonomy codes. Mental and Behavioral includes providers such as counselors, psychologists, and social workers and does not include psychiatrists. Primary Care includes geriatricians. Pediatricians and pediatric specialists are excluded from each classification. Integrated health systems are excluded from each row with the exception of the integrated health system percentages as they differ substantially from other contracts. Providers included individual MDs, NPs, PA’s, psychologists, and others who are required to register for an NPI

DISCUSSION

We find mental and behavioral health providers, cardiologists, psychiatrists, and primary care providers were the least likely to be included in any MA network. Contracts with higher market share tended to have larger networks, while the contracts with the highest star ratings more often had narrow primary care networks.

While one study found that primary care networks were generally broad for MA, our results may differ as we are not limited by the use of Part D data, and our data is more recent and representative of MA enrollment.3

The highest rated contracts tended to have the narrowest primary care networks. As primary care providers are often responsible for many of the quality measures that are included in the calculation of star ratings, our findings suggest that plans may contract with a narrow set of high-quality providers in order to maximize their quality ratings.

We also find substantial racial/ethnic disparities in access to wider MA networks for primary care, psychiatry, and mental and behavioral health among Hispanic and Asian enrollees. It’s well established that Black, Hispanic, and Asian enrollees experience poorer outcomes in the MA program than white enrollees6, and more research is needed to understand if network composition may contribute to these disparities.

Our findings have several key implications. First, there appears to be limited access to mental and behavioral health specialists in the MA program. Refinement may be needed to network adequacy standards to ensure that all enrollees have access to adequate mental health care. Second, there is large variation in network breadth across contracts and this variation may not be clear to enrollees at the time of their plan decisions as they try to balance provider choice with the cost of different plans. The inclusion of network breadth measures in the Medicare plan finder may help enrollees make plan decisions more in line with their healthcare needs.

Author’s contributors

There were no other contributors beyond those included as authors.

Funding

This work was funded by NIA 5P01AG027296-12.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

There are no prior presentations to report.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage Checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–2172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Rahman M. Comparison of the Quality of Hospitals That Admit Medicare Advantage Patients vs Traditional Medicare Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919310–e1919310. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feyman Y, Figueroa JF, Polsky DE, Adelberg M, Frakt A. Primary Care Physician Networks In Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):537–544. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haeder SF, Weimer D, Mukamel DB. A Consumer-Centric Approach To Network Adequacy: Access To Four Specialties In California’s Marketplace. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(11):1918–1926. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu JM, Zhang Y, Polsky D. Networks In ACA Marketplaces Are Narrower For Mental Health Care Than For Primary Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1624–1631. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trivedi ANZA, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Relationship between quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare health plans. JAMA. 2006;296(16):1998–2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]