Abstract

Background

Despite substantial research on medical student mistreatment, there is scant quantitative data on microaggressions in US medical education.

Objective

To assess US medical students’ experiences of microaggressions and how these experiences influenced students’ mental health and medical school satisfaction.

Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional, online survey of US medical students’ experiences of microaggressions.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was a positive depression screen on the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). Medical school satisfaction was a secondary outcome. We used logistic regression to model the association between respondents’ reported microaggression frequency and the likelihood of a positive PHQ-2 screen. For secondary outcomes, we used the chi-squared statistic to test associations between microaggression exposure and medical school satisfaction.

Key Results

Out of 759 respondents, 61% experienced at least one microaggression weekly. Gender (64.4%), race/ethnicity (60.5%), and age (40.9%) were the most commonly cited reasons for experiencing microaggressions. Increased microaggression frequency was associated with a positive depression screen in a dose-response relationship, with second, third, and fourth (highest) quartiles of microaggression frequency having odds ratios of 2.71 (95% CI: 1–7.9), 3.87 (95% CI: 1.48–11.05), and 9.38 (95% CI: 3.71–26.69), relative to the first quartile. Medical students who experienced at least one microaggression weekly were more likely to consider medical school transfer (14.5% vs 4.7%, p<0.001) and withdrawal (18.2% vs 5.7%, p<0.001) and more likely to believe microaggressions were a normal part of medical school culture (62.3% vs 32.1%) compared to students who experienced microaggressions less frequently.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the largest study on the experiences and influences of microaggressions among a national sample of US medical students. Our major findings were that microaggressions are frequent occurrences and that the experience of microaggressions was associated with a positive depression screening and decreased medical school satisfaction.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06786-6.

KEY WORDS: diversity and inclusion, medical education, mental health, microaggressions, physician workforce, physician burnout

INTRODUCTION

Discrimination is a particularly detrimental manifestation of bias1, 2 that harms medical students both personally and professionally.3–7 Discriminatory behavior includes being passed over for recognition, receiving poor evaluations, and being ridiculed, ostracized, or intimidated because of one’s race, gender, or other marginalized identities.1–7 Recently, researchers have been increasingly interested in less overt forms of bias called “microaggressions.”8, 9 Defined by psychiatrist Chester Pierce to describe the daily derogatory slights experienced by Black Americans,10 microaggressions are debasements of minoritized groups encompassing “everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership.”11 Examples include addressing a female physician as a nurse or a White person clutching their purse when passing a Black person.9

While overt discrimination experienced by medical students has been described previously,12–14 there is a paucity of literature on microaggressions in undergraduate medical education (UME). Approximately 27% of medical students have been reported to demonstrate depressive symptoms,15 and the association between discrimination and diminished well-being among medical students is well established.16 Women trainees who reported experiencing discrimination were more likely to manifest unhealthy alcohol use and depressive symptoms compared to women without these experiences.3 Minority medical students who experienced discrimination were more likely to suffer burnout and depressive symptoms compared to minorities who did not report discrimination.17 Examining less overt forms of discrimination, such as microaggressions, is necessary to fully understand how bias affects trainee mental health.

Furthermore, microaggressions may contribute to underrepresentation of women and minoritized groups in academic medicine.18, 19 Existing literature has shown an association between discrimination, job satisfaction, and job turnover.20–22 Physicians who experienced discrimination reported lower job satisfaction23 and were more likely to contemplate career change than physicians without these experiences.24 It is therefore imperative to understand whether microaggressions may similarly affect career satisfaction and retention beginning in UME.

In this study, we conducted a national survey of diverse US medical students on their experiences of microaggressions perpetrated by fellow students, residents, and faculty. We investigated the relationships between the experience of microaggressions and medical student well-being, their perceptions of institutional climate, and satisfaction with their medical school.

METHODS

Study Design

We implemented a cross-sectional, internet-based, anonymous survey of medical students in the USA. The study was approved by the Yale Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Boards. Online consent included a description of the study, including potential harm.

The survey was distributed between July 2016 and October 2017 via email listservs of the Student National Medical Association (SNMA), the Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA), the Association of Native American Medical Students (ANAMS), and the Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA). While these groups represent the largest organizations designed to support minoritized MD and DO students in the USA, all medical students are eligible for membership regardless of racial identity/ethnicity. Because minority medical students report disproportionate rates of discriminatory experiences,12 these organizations were selected in order to oversample minority medical students. Individuals could also independently forward the survey to peers outside these organizations. Participants received no monetary incentives and were not required to fill out all questions.

Questionnaire Design

The survey email discussed the questionnaire’s intent to characterize the experience of microaggressions among US medical students with the goal of improving diversity and inclusion in medical education. Questions regarding microaggressions were adapted from the validated Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS).25 Questions on institutional climate and response to microaggressions were adapted from the Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire (IBQ).26 Questions were adapted to the academic medical center environment and pilot tested among 20 diverse medical students from the Yale School of Medicine.

Questions adapted from the REMS measured whether the participant had experienced any of 16 microaggressions without directly mentioning racism, prejudice, or demographics such as race, gender, or sexual orientation (Table 2). Participants were instructed to include microaggressions committed by fellow students, residents, and faculty. Respondents indicated how often they experienced each type of microaggression (0=never; 1=less than once a year; 2=a few times a year; 3=at least once monthly; 4=at least once weekly; and 5=almost daily). Responses were scored and summed across the 16 items (range=0–80), resulting in a “microaggression frequency score” for each respondent. Higher scores indicated greater frequency of exposure to microaggressions. Similar methods have been used to measure exposure frequency in surveys of self-reported discrimination.27–29

Table 2.

Prevalence and Frequency of Experiences of Microaggressions Among Survey Respondents

| Microaggression | Frequency Number of respondents (% of total respondents) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Less than once a year | A few times a year | At least once a month | At least once a week | Almost everyday | |

| People trivialize my ideas in classroom discussions. | 145 (19.1) | 141 (18.6) | 201 (26.5) | 131 (17.3) | 95 (12.5) | 44 (5.8) |

| People devalue my opinion on patient care. | 211 (27.8) | 138 (18.2) | 174 (22.9) | 125 (16.5) | 82 (10.8) | 25 (3.3) |

| My ideas in the classroom are met with hostility. | 344 (45.3) | 164 (21.6) | 125 (16.5) | 79 (10.4) | 30 (4) | 16 (2.1) |

| People mistake me for someone else who shares an aspect of my identity. | 140 (18.4) | 96 (12.6) | 192 (25.3) | 173 (22.8) | 104 (13.7) | 52 (6.9) |

| People imply that I was admitted to medical school for reasons other than academic merit. | 379 (49.9) | 137 (18.1) | 152 (20) | 43 (5.7) | 20 (2.6) | 28 (3.7) |

| People are surprised by how well I speak English. | 450 (59.3) | 78 (10.3) | 117 (15.4) | 51 (6.7) | 27 (3.6) | 35 (4.6) |

| In clinical settings or at my medical school, I am mistaken for auxiliary staff. | 308 (40.6) | 88 (11.6) | 137 (18.1) | 107 (14.1) | 65 (8.6) | 48 (6.3) |

| People seem surprised by my intelligence. | 233 (30.7) | 134 (17.7) | 166 (21.9) | 109 (14.4) | 61 (8) | 55 (7.2) |

| I am made to feel unwelcome in a group. | 228 (30) | 154 (20.3) | 182 (24) | 98 (12.9) | 61 (8) | 34 (4.5) |

| People are cautious with their personal belongings around me. | 570 (75.1) | 87 (11.5) | 52 (6.9) | 24 (3.2) | 10 1.3) | 14 (1.8) |

| I am reluctant to ask questions because I feel I will be judged. | 117 (15.4) | 66 (8.7) | 151 (19.9) | 148 (19.5) | 136 (17.9) | 140 (18.4) |

| My ideas are ignored but other people are applauded when they say the same thing. | 173 (22.8) | 142 (18.7) | 158 (20.8) | 139 (18.3) | 88 (11.6) | 59 (7.8) |

| I feel socially isolated at my medical school. | 196 (25.8) | 124 (16.3) | 143 (18.8) | 113 (14.9) | 98 (12.9) | 83 (10.9) |

| Faculty discourage me from pursing a medical field I am interested in. | 467 (61.5) | 115 (15.2) | 87 (11.5) | 47 (6.2) | 22 (2.9) | 19 (2.5) |

| People assume that I could be violent. | 589 (77.6) | 63 (8.3) | 47 (6.2) | 27 (3.6) | 17 (2.2) | 15 (2) |

| I feel invisible at my medical school. | 289 (38.1) | 149 (19.6) | 119 (15.7) | 83 (10.9) | 66 (8.7) | 53 (7) |

Cronbach’s α for scale is 0.91

Respondents who reported experiencing microaggressions were asked why they believed they had experienced the microaggression. Participants could choose multiple attributions for each microaggression, including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, shade of skin, sexual orientation, age, height, weight, disability, socioeconomic status (SES), and unknown. Participants could also enter sources of attribution via free text.

Participants’ demographic characteristics were also assessed. These included racial identity (White, Asian, Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Other, and Multiracial), Hispanic/Latinx(a/o) ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, year of birth, sexual orientation, gender identity, year in medical school, clinical experience, self-reported socioeconomic class, religious affiliation, name of medical school, and nativity (Table 1) (see Appendix 1 for full survey).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents (N=759)

| Demographic | Overall N=759 (100% of total respondents) |

High microaggression exposure group N=462 (61% of total respondents) |

Odds ratio (CI) for high microaggression exposure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| White | 238 (31.4) | 116 (25.1) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Asian | 179 (23.6) | 115 (24.9) | 1.89 (1.27, 2.82) |

| Black | 222 (29.2) | 160 (34.6) | 2.71 (1.85, 4.02) |

| Other* | 26 (3.4) | 16 (3.5) | 1.68 (0.74, 3.98) |

| Multiracial | 79 (10.4) | 49 (10.6) | 1.72 (1.03, 2.91) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Non-Hispanic | 663 (87.4) | 403 (87.2) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Hispanic | 9112 | 56 (12.1) | 0.97 (0.61, 1.51) |

| Sex assigned at birth, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Male | 240 (31.6) | 126 (27.3) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Female | 518 (68.2) | 335 (72.5) | 1.66 (1.21, 2.26) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 2624–28 | 26 (24–28) | -- |

| First quartile | 178 (23.5) | 104 (22.5) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Second quartile | 214 (28.2) | 131 (28.4) | 1.12 (0.75, 1.69) |

| Third quartile | 153 (20.2) | 96 (20.8) | 1.2 (0.77, 1.87) |

| Fourth quartile | 127 (16.7) | 79 (17.1) | 1.17 (0.74, 1.87) |

| Sexual orientation, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Straight/heterosexual | 613 (80.8) | 383 (82.9) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Bisexual | 43 (5.7) | 23 (5) | 0.69 (0.37, 1.3) |

| Gay/lesbian | 51 (6.7) | 27 (5.8) | 0.68 (0.38, 1.21) |

| Queer | 37 (4.9) | 23 (5) | 0.99 (0.5, 2) |

| Unsure | 13 (1.7) | 6 (1.3) | 0.51 (0.16, 1.57) |

| Gender identity, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Cisgender man or cisgender woman | 738 (97.2) | 453 (98.1) | -- |

| Transgender woman | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | -- |

| Transgender man | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | -- |

| Genderqueer | 9 (1.2) | 4 (0.9) | -- |

| Unsure | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | -- |

| Year in medical school, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| First year | 222 (29.2) | 138 (29.9) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Second year | 189 (24.9) | 107 (23.2) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.18) |

| Third year | 163 (21.5) | 108 (23.4) | 1.2 (0.78, 1.83) |

| Fourth year | 146 (19.2) | 86 (18.6) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.34) |

| Fifth year or greater | 38 (5) | 23 (5) | 0.93 (0.46, 1.92) |

| Clinical experience, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Yes | 179 (23.6) | 112 (24.2) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| No | 579 (76.3) | 349 (75.5) | 0.91 (0.64, 1.28) |

| Economic class, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Lower | 85 (11.2) | 65 (14.1) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Lower middle | 138 (18.2) | 97 (21) | 0.73 (0.39, 1.34) |

| Middle | 235 (31) | 126 (27.3) | 0.36 (0.2, 0.62) |

| Upper middle | 251 (33.1) | 149 (32.3) | 0.45 (0.25, 0.78) |

| Upper | 40 (5.3) | 18 (3.9) | 0.25 (0.11, 0.55) |

| Religion, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Christian | 350 (46.1) | 226 (48.9) | -- |

| Buddhist | 8 (1.1) | 7 (1.5) | -- |

| Hindu | 19 (2.5) | 13 (2.8) | -- |

| Jewish | 42 (5.5) | 17 (3.7) | -- |

| Muslim | 28 (3.7) | 22 (4.8) | -- |

| No religious affiliation | 271 (35.7) | 149 (32.3) | -- |

| Other | 41 (5.4) | 28 (6.1) | -- |

| Geography, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Northeast | 251 (33.1) | 143 (31) | -- |

| South | 86 (11.3) | 56 (12.1) | -- |

| Midwest | 148 (19.5) | 98 (21.2) | -- |

| West | 178 (23.5) | 106 (22.9) | -- |

| Born in the USA, N (%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Yes | 606 (79.8) | 362 (78.4) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| No | 153 (20.2) | 100 (21.6) | 1.27 (0.88, 1.85) |

*The category “Other” includes two individuals who identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. There were no American Indian/Alaska Native respondents

Outcome Measures

The primary study outcome was a positive screen for depression, defined as a cutoff score of 3 on the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2).30 The PHQ-2 is a validated screening instrument for depression with comparable sensitivity and specificity to other measures of depression.30, 31

As a secondary outcome, medical school satisfaction was evaluated with six statements (Table 4). The first three statements evaluated students’ endorsement of their medical school: (1) “I would recommend my medical school to friends,” (2) “I would donate money to my medical school after graduation,” (3) “I would consider residency training at my current institution.” Responses to statements 1–3 were based on a 4-point scale: 1=yes, enthusiastically; 2=yes, possibly; 3=yes, reluctantly; 4=no. The last three statements on medical school satisfaction assessed if students’ experiences had affected their behavior or prompted them to reconsider their medical training: (4) “I have chosen to miss some classes in medical school because the environment was unwelcoming,” (5) “I have seriously considered transferring to another medical school,” and (6) “I have seriously considered withdrawing from medical school.” Responses to statements 4–6 were based on a 4-point scale: 1=strongly agree; 2=agree; 3=disagree; 4=strongly disagree. We examined institutional climate with 7 statements (Table 4): (1) "My medical school has adequate teaching about implicit bias,” (2) “My medical school has adequate curricular elements to help me identify microaggressions,” (3) “My medical school takes proactive steps to prevent microaggressions,” (4) “I know how to report microaggressions to leadership in my medical school,” (5) “If I reported a microaggression, school leadership would respond appropriately,” (6) “I would be punished if I reported a microaggression at my medical school,” and (7) “Microaggressions are a normal part of the culture at my medical school.” The first two items were scored yes or no, and the last five items were scored with a 4-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Table 4.

Medical School Satisfaction and Climate by Microaggression Exposure Level

| Low microaggression exposure | High microaggression exposure | p value* | Number and percent missing, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical student satisfaction | ||||

| Recommend (Yes) | 251/296 (84.8%) | 324/462 (70.1%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| Donate to school after graduation (Yes enthusiastically, yes possibly, and yes reluctantly) | 286/296 (96.6%) | 419/462 (90.7%) | 0.003 | 1 (0.1) |

| Stay at current school for residency (Yes enthusiastically, yes possibly, and yes reluctantly) | 273/296 (92.2%) | 377/462 (81.6%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| Missed class because environment unwelcoming (strongly agree or agree) | 31/297 (10.4%) | 158/462 (34.2%) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Considered medical school transfer (strongly agree or agree) | 14/297 (4.7%) | 67/461 (14.5%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| Considered medical school withdrawal (strongly agree or agree) | 17/297 (5.7%) | 84/462 (18.2%) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Institutional climate | ||||

| My medical school has adequate teaching about implicit bias (Yes) | 63/294 (21.4%) | 50/461 (10.8%) | <0.001 | 4 (0.5) |

| My medical school has adequate curricular elements to help me identify microaggressions (Yes) | 100/296 (33.8%) | 78/462 (16.9%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| My medical school takes proactive steps to prevent microaggressions (strongly agree or agree) | 156/297 (52.5%) | 143/462 (31%) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| I know how to report microaggressions to leadership in my medical school (strongly agree or agree) | 219/296 (74%) | 270/461 (58.6%) | <0.001 | 2 (0.3) |

| If I reported a microaggression, school leadership would respond appropriately (strongly agree or agree) | 169/297 (56.9%) | 173/461 (37.5%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| I would be punished if I reported a microaggression at my medical school (strongly agree or agree) | 15/297 (5.1%) | 85/461 (18.4%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.1) |

| Microaggressions are a normal part of the culture at my medical school (strongly agree or agree) | 95/296 (32.1%) | 287/461 (62.3%) | <0.001 | 2 (0.3) |

*Based on chi-squared test for independence

Statistical Analysis

Respondents’ microaggression frequency scores were converted into quartiles. We used logistic regression to model the association between respondents’ reported total microaggression frequency score and the likelihood of a positive PHQ-2 screen, adjusting for racial identity, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, US citizenship, year in medical school, clinical experience in medical school, economic class, and religion. For secondary outcome measures, we used the chi-squared statistic to test the associations between medical students’ microaggression exposure and medical school satisfaction. Approximately half our respondents experienced a microaggression at least once a week. Therefore, we compared respondents who experienced one or more microaggressions a week (the “higher exposure” group) with respondents who experienced microaggressions less frequently (the “lower exposure” group). To account for multiple comparisons, we used a Bonferroni adjustment of α=0.007 to determine statistical significance. Additionally, we tabulated responses to questions on institutional climate surrounding microaggressions. All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2.

RESULTS

Responses

In total, 939 respondents from 120 medical schools returned surveys. A formal response rate was not calculated because of the inability to ascertain how many medical students received the survey.32 Of those 939 returned surveys, 759 (80.8%) met final inclusion criteria of completing at least 90% of the survey and Table 1 shows their demographic characteristics. White respondents (31.4%) represented the largest group by racial identity. Black (29.2%) and Hispanic (12.0%) respondents were overrepresented relative to their percentages among US medical students (7.3% and 6.5%, respectively).33 Asian respondents (23.6%) were slightly overrepresented compared to the overall percentage of Asian medical students (22.5%).33 Women (68.2%) were also overrepresented compared to their percentage among US medical students (50.5%).33 The median age was 26, and the majority were born in the USA (79.8%).

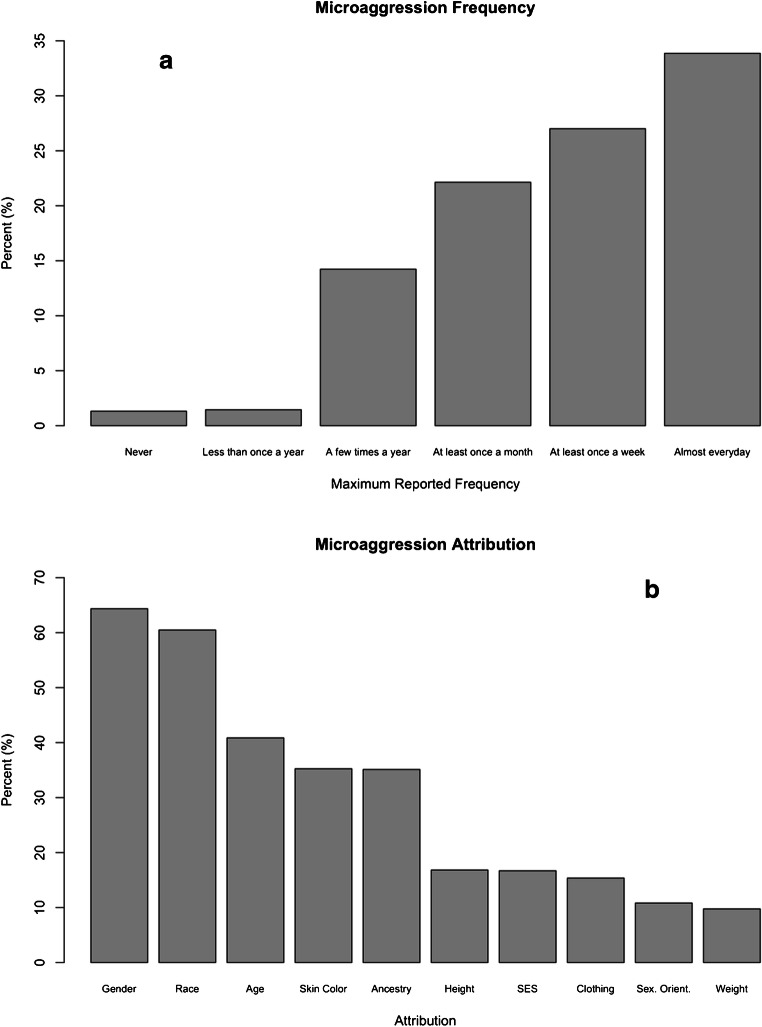

Microaggression Exposure

The experience of microaggressions was common: 98.7% (749/759) of participants reported experiencing at least one microaggression in medical school, and 33.9% reported experiencing a microaggression almost daily (Fig. 1). Gender (64.4%), race/ethnicity (60.5%), and age (40.9%) were the most common reasons cited for experiences of microaggressions (Fig. 1). Students who identified as Black (OR 2.71, 95% CI: 1.85–4.02), Asian (OR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.27–2.82), Multiracial (OR 1.72, 95% CI: 1.03–2.91), and being of female sex (OR 1.66, 95% CI: 1.21–2.26) were the most likely to report experiencing at least one microaggression a week (Table 1). Cronbach’s α for the microaggressions scale was 0.91 (Table 2). Year in medical school was not associated with the likelihood of being in the higher exposure group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

a Microaggression frequencies as reported by participants. b Microaggression attributions as reported by participants.

Because sex and race/ethnicity were the most common attributions for experiences of microaggressions, we tested for an interaction between student sex and race/ethnicity, which was not significant. White males reported the lowest average microaggression frequency scores (M=16.22, SD=12.44) and Black females reported the highest mean microaggression frequency scores (M=31.24, SD=15.72) (Table 3). White racial identity—regardless of gender—was associated with lower average microaggression frequency scores than any other racial or ethnic identity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cross-tabulation of Race/Ethnicity and Sex with Mean Microaggression Frequency Score

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (95% CI) | --Ref-- | 4.79 (2.58–7.01) | |

| Mean Microaggression Freq Score (SD) | Mean Microaggression freq Score (SD) | ||

| White | --Ref-- | 16.22 (12.44) | 19.87 (11.12) |

| Asian | 3.73 (0.95–6.51) | 17.51 (13.26) | 24.36 (12.97) |

| Black | 11.95 (9.31–14.59) | 29.41 (18.25) | 31.24 (15.72) |

| Other | 8.82 (2.92–14.72) | 25.7 (17.29) | 29.56 (14.07) |

| Multiracial | 6.56 (2.93–10.18) | 18.59 (14.94) | 29.8 (16.34) |

| Non-Hispanic | --Ref-- | 20 (15.69) | 25.83 (14.43) |

| Hispanic | 2.13 (−1.41 to 5.67) | 22.71 (15.14) | 25.5 (15.95) |

Depressive Symptoms

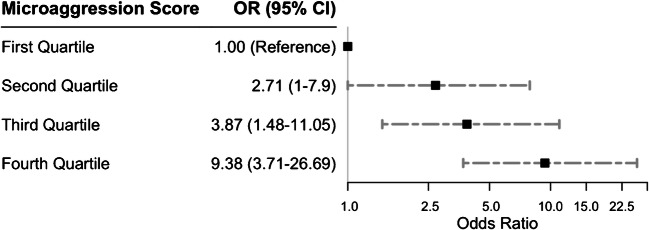

Among respondents, 14.2% (108/759) had a positive screen for depression. In our adjusted analysis, the experience of microaggressions was significantly associated with a positive screen for depression in a dose-response relationship (Fig. 2). As frequency of microaggressions increased, the likelihood of a positive depression screen increased accordingly, with second, third, and fourth (highest) quartiles of microaggression frequency scores having odds ratios of 2.71 (95% CI: 1–7.9), 3.87 (95% CI: 1.48–11.05), and 9.38 (95% CI: 3.71–26.69), relative to the first quartile (Fig. 2). As the frequency of microaggressions increased, the likelihood of a respondent having a positive screen for depression increased even after adjusting for race/ethnicity, sex, and other demographic factors including sexual orientation, US citizenship, gender identity, year in medical school, SES, religion, and clinical experience (Appendix 2).

Figure 2.

Microaggression frequency score quartiles and odds ratios for a positive depression screen.

Medical School Satisfaction

Sixty-one percent of respondents experienced at least one microaggression a week. These respondents were less likely to recommend their medical school to friends (70.1% vs 84.8%, p<0.001), less likely to donate money to their medical school after graduation (90.7% vs 96.6%, p=0.003), and less likely to want to stay at their institution for residency (81.6% vs 92.2%, p<0.001) compared to respondents who experienced microaggressions less frequently (Table 4). Higher exposure respondents were over three times more likely to miss class because the environment was unwelcoming (34.2% vs 10.4%, p<0.001) and nearly four times more likely to consider medical school transfer (14.5% vs 4.7%, p<0.001) and withdrawal (18.2% vs 5.7%, p<0.001) compared to lower exposure respondents (Table 4).

Institutional Climate

Table 4 also compares responses on institutional climate surrounding microaggressions in higher and lower microaggression exposure groups. Only 10.8% of participants in the higher exposure group felt their medical school provided adequate teaching about implicit bias. Even in the lower exposure group, fewer than a quarter (21.4%) felt implicit bias teaching was adequate (p<0.001). Higher exposure respondents were also less likely to report that their school had adequate curricular elements to help identify microaggressions (16.9% vs 33.8%, p<0.001) and less likely to believe their school was taking proactive steps to prevent microaggressions (31.0% vs 52.5%, p<0.001) than lower exposure respondents. The higher exposure group was less likely to respond that they knew how to report microaggressions (58.6% vs 74%, p<0.001), less likely to believe leadership would respond appropriately to reported microaggressions (37.5% vs 56.9%, p<0.001), more likely to believe they would be punished if they reported microaggressions (18.4% vs 5.1%, p<0.001), and more likely to believe that microaggressions were a normal part of their medical school’s culture (62.3% vs 32.1%, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study focused on the experiences, frequency, and effects of microaggressions among a national sample of US medical students. Our first major finding was that medical students frequently experience microaggressions. Our second major finding was that increased frequency of experiencing microaggressions was associated with a positive depression screening. This finding supports literature that has demonstrated an association between microaggression exposure and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in other populations.27, 34–37

Medical student exposure to microaggressions in our study was also associated with lower medical school satisfaction, decreased classroom attendance, and increased consideration of medical school transfer and withdrawal. This is consistent with research that has shown an association between experiences of discrimination and lower physician job satisfaction.20–24 Our data suggests that experiencing microaggressions in medical school may have similar effects to overt discrimination in the workplace.

Our results also show that higher exposure to microaggressions was associated with decreased satisfaction with curricular treatment of microaggressions, decreased confidence in institutional responses to reported microaggressions, and an increased sense that microaggressions were a normal part of medical school culture. This finding is congruent with prior literature describing microaggressions in higher education.34, 38, 39 Furthermore, most students reported that their medical schools did not offer sufficient teaching about microaggressions and did not take proactive steps to limit their occurrence.

Our test for an interaction between student sex and race/ethnicity was not significant. Therefore, individuals who experienced microaggressions at the intersection of minoritized sex and racial/ethnic background, based on our data, experienced at least an additive effect. The sex and race/ethnicity cross-tabulated means of microaggression frequency support this conclusion by showing that Black females reported the highest microaggression frequency scores and White males reported the lowest microaggression frequency scores. These findings imply that medical students who hold multiple marginalized identities are likely subject to higher rates of microaggressions than those who hold a single marginalized identity. Future directions for this research should include more detailed analysis of how intersectional identities affect the experience of microaggressions among medical students.

IMPLICATIONS

This study has several implications for leaders of academic medical centers, national medical societies, governing bodies of UME, and anyone working to combat bias and discrimination in medicine.

First, the prevalence and frequency of microaggressions reported in our study contrasts with evidence that overt bias and discrimination are declining in medical schools.9, 40, 41 This finding supports the idea that microaggressions may be supplanting more pronounced acts of bias10 and that, as social mores change, biases such as racism evolve and manifest in more socially acceptable, but similarly harmful ways.40, 41 Therefore, institutions seeking to address bias towards medical students should include microaggressions as a measure of institutional climate in addition to overt discrimination.

Second, the association between microaggression exposure and a positive screening for depression among students suggests that microaggressions may have a significant influence on medical students’ mental health. This finding may be relevant to academic administrators, training directors, and national organizations––such as the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) and the ACGME––seeking to address the alarmingly high rates of depression, suicidal ideation, and burnout among medical students.15, 42–47 Many medical school wellness interventions48–50 do not address the impact of microaggressions. Our findings suggest that they should, else they risk ignoring an issue that may profoundly affect the mental health of their medical students.

Third, the association we found between increased microaggression exposure and decreased medical school satisfaction may affect the recruitment and retention of diverse medical students. Students who identified as Black, Asian, Multiracial, and female were the most likely to belong to the higher microaggression exposure group. Respondents in this group were less likely to recommend their medical school to friends, more likely to consider transfer and withdrawal, and less likely to want to stay at their institution for residency. These findings suggest a possible influence of microaggressions on the attrition of diverse medical trainees, which may be relevant to the Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) and NAM’s calls for increased physician workforce diversity.51, 52 They may also be pertinent to the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), a national accrediting body for MD-granting institutions whose accreditation standards require that medical schools make efforts to attract and retain diverse students.53

Fourth, our study implies that current institutional responses to microaggressions may be inadequate. Fewer than half our participants felt their medical school had adequate teaching, proactive prevention, or appropriate responses regarding microaggressions. This is consistent with research that has shown medical students’ lack of confidence in their schools’ handling of mistreatment. For instance, in a national survey conducted by the AAMC, two-thirds of medical students who experienced mistreatment did not report the incident because they feared reprisal or felt reporting would be ineffective.54 Research has shown that the negative effects of student mistreatment are exacerbated when educational institutions fail to respond adequately.26, 55, 56 Our data suggests that medical schools must improve their handling of reports of microaggressions to avoid compounding the negative effects of microaggressions on medical students.

Finally, our study suggests value in re-evaluating the word “microaggression.” Research has shown that reviewers of reports of discriminatory behavior were less likely to support mitigation of discriminatory acts associated with implicit rather than explicit bias.57 Therefore, the term “microaggression” itself, which is defined as a subtle, implicit form of bias, may unwittingly make medical schools less likely to take microaggressions seriously. Administrators may consider replacing the term “microaggression” with more specific terms, such as racism, sexism, and homophobia. In addition, the qualifier “micro” reflects the dominant-group perpetrator’s perception of the supposed innocuousness of microaggressions rather than the victim’s perspective.58, 59 Our findings, which show associations between microaggressions and serious outcomes for medical students (depressive symptoms, avoiding class, and contemplating withdrawing from medical school), suggest that the experience of microaggressions impacts medical students in ways that are not so “micro.”

LIMITATIONS

The associations reported here are correlational and need not imply a causal relationship between the experience of microaggressions and medical student outcomes. Another limitation is use of the PHQ-2. While the PHQ-2 is a validated screening tool, it cannot definitively diagnose depression. There is potential response bias, as students who had experienced microaggressions may have been more likely to participate. To minimize nonresponse bias, we sent three reminder emails and repeatedly promoted the survey in SNMA, LMSA, ANAMS, and APAMSA digital newsletters to capture students who did not respond on our first recruitment pass. In addition, students were able to share the survey with peers outside these organizations. Also, because very few respondents identified as non-binary gender minorities, the study is limited in conclusions on the impact of microaggressions in this subpopulation. Because racial and ethnic minority medical students and women were overrepresented in our study, our results may not be generalizable to all medical students, especially White men. We did not assess microaggressions perpetrated by patients, which likely resulted in an underreporting of total microaggressions experienced by respondents. In addition, there may have been less awareness of microaggressions among medical students in 2017. Nevertheless, these sources of potential underreporting would not negate the generalizability of our findings and would ultimately bias our results towards the null hypothesis. Another limitation of the study is its cross-sectional nature, which only provides data at the time of survey completion, and therefore cannot provide information about how microaggressions affect medical students over time.

CONCLUSION

Medical students in our study experienced microaggressions frequently. These experiences were associated with a positive screening for depression and lower medical school satisfaction. These findings have significant implications for medical students’ mental health, workforce diversity, and medical school satisfaction. Our findings also highlight the need for further study of microaggressions, improved interventions to prevent microaggressions in medical schools, and addressing the effects of microaggressions in medical school wellness and mental health initiatives.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 31 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable support of SNMA, LMSA, ANAMS, and APAMSA. EL and ENA would like to acknowledge the Black Health Scholars Network for their support. CJ would like to particularly acknowledge SNMA for their contributions to this study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ogden PE, Wu EH, Elnicki MD, et al. Do attending physicians, nurses, residents, and medical students agree on what constitutes medical student abuse? Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S80–83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orom H, Semalulu T, Underwood W., 3rd The social and learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students: a narrative review. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1765–1777. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7a3af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM, Christensen ML. Mental health consequences and correlates of reported medical student abuse. Jama. 1992;267(5):692–694. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480050096032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):817–827. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):749–754. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV, White K, Leibowitz A, Baldwin DC., Jr A pilot study of medical student ‘abuse’. Student perceptions of mistreatment and misconduct in medical school. Jama. 1990;263(4):533–537. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440040072031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. Bmj. 2006;333(7570):682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dovidio J, Gaertner S, Kawakami K, Hodson G. Why can’t we just get along? Interpersonal biases and interracial distrust. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2002;8(2):88–102. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;6(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce CM, Carew JV, Pierce-Gonzales D, Willis D. An experiment in racism: TV commercials. Education and Urban Society. 1977;10:61–87. doi: 10.1177/001312457701000105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sue DW. Microaggressions: More than just race. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/microaggressions-in-everyday-life/201011/microaggressions-more-just-race. Published 2010. Accessed.

- 12.Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, et al. Assessment of the Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):653–665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, Moore E, Nunez-Smith M. Racial Disparities in Medical Student Membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(5):659–665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez-Smith M, Jordan A, Chekroud A, Moore EZ. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in Medical Student Performance Evaluations. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardeman RR, Przedworski JM, Burke S, et al. Association Between Perceived Medical School Diversity Climate and Change in Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students: A Report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2016;108(4):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2103–2109. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R, Chapman CH, Both S, Thomas CR., Jr Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706–1708. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackerman-Barger K, Boatright D, Gonzalez-Colaso R, Orozco R, Latimore D. Seeking Inclusion Excellence: Understanding Racial Microaggressions as Experienced by Underrepresented Medical and Nursing Students. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):758–763. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ensher EA, Grant-Vallone EJ, Donaldson SI. Effects of perceived discrimination on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and grievances. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2001;12(1):53–72. doi: 10.1002/1532-1096(200101/02)12:1<53::AID-HRDQ5>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madera JM, King EB, Hebl MR. Bringing social identity to work: the influence of manifestation and suppression on perceived discrimination, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(2):165–170. doi: 10.1037/a0027724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King EB, Dawson JF, Kravitz DA, Gulick LMV. A multilevel study of the relationships between diversity training, ethnic discrimination and satisfaction in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2012;33(1):5–20. doi: 10.1002/job.728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daugherty SR, Baldwin DC, Jr, Rowley BD. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship: a national survey of working conditions. Jama. 1998;279(15):1194–1199. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunez-Smith M, Pilgrim N, Wynia M, et al. Health care workplace discrimination and physician turnover. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1274–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadal KL. The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): construction, reliability, and validity. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(4):470–480. doi: 10.1037/a0025193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Dangerous safe havens: institutional betrayal exacerbates sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(1):119–124. doi: 10.1002/jts.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Keefe VM, Wingate LR, Cole AB, Hollingsworth DW, Tucker RP. Seemingly Harmless Racial Communications Are Not So Harmless: Racial Microaggressions Lead to Suicidal Ideation by Way of Depression Symptoms. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(5):567–576. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes LL, de Leon CF, Lewis TT, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Perceived discrimination and mortality in a population-based study of older adults. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1241–1247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown C, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT, Chang Y. The relation between perceived unfair treatment and blood pressure in a racially/ethnically diverse sample of women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(3):257–262. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altieri MS, Salles A, Bevilacqua LA, et al. Perceptions of Surgery Residents About Parental Leave During Training. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(10):952–958. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AAMC. AAMC Medical Education Facts Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity (Alone) and Sex, 2015-2016 through 2019-2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/2019-facts-enrollment-graduates-and-md-phd-data. Published 2019. Accessed 2020.

- 34.Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, Denny N. The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically White institution. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(1):45–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huynh VW. Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(7):831–846. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9756-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Leu J, Shoda Y. When the seemingly innocuous "stings": racial microaggressions and their emotional consequences. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37(12):1666–1678. doi: 10.1177/0146167211416130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, Rasmus M. The Impact of Racial Microaggressions on Mental Health: Counseling Implications for Clients of Color. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2014;92(1):57–66. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00130.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lilly F, Owens J, Bailey TC, et al. The Influence of Racial Microaggressions and Social Rank on Risk for Depression among Minority Graduate and Professional Students. College student journal. 2018;52:86–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levchak CC. Microaggressions and Modern Racism: Endurance and Evolution. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018.

- 40.Fields KE. 2012 Racecraft the soul of inequality in American life. London: Verso

- 41.Benjamin R. Innovating inequity: if race is a technology, postracialism is the genius bar. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2016;39(13):2227–2234. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1202423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520-1525. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Goebert D, Thompson D, Takeshita J, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: a multischool study. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):236-241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Meducation ACfGM. AWARE Well-Being Resources. https://acgme.org/What-We-Do/Initiatives/Physician-Well-Being/AWARE-Well-Being-Resources. Accessed 2020.

- 46.Paturel A. Healing the very youngest healers. AAMC News Web site. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/healing-very-youngest-healers. Published 2020. Accessed 2020.

- 47.Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/. Accessed 2020.

- 48.Erogul M, Singer G, McIntyre T, Stefanov DG. Abridged mindfulness intervention to support wellness in first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):350-356. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Drolet BC, Rodgers S. A comprehensive medical student wellness program--design and implementation at Vanderbilt School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):103-110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Slavin SJ, Schindler DL, Chibnall JT. Medical student mental health 3.0: improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):573-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, et al. 2002 Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press. [PubMed]

- 52.Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, Gampfer KR, Nivet MA. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1192. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.(LCME) LCoME. Functions and Structure of a Medical School.https://lcme.org/publications/2018. [PubMed]

- 54.Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):705-711. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Institutional betrayal. Am Psychol. 2014;69(6):575-587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Wright NM, Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Experience of a Lifetime: Study Abroad, Trauma, and Institutional Betrayal. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2017;26(1):50-68.

- 57.Daumeyer NM, Onyeador IN, Brown X, Richeson JA. Consequences of attributing discrimination to implicit vs. explicit bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2019;84:103812.

- 58.Minikel-Lacocque J. Racism, college, and the power of words: racial microaggressions reconsidered. American Educational Research Journal. 2013;50(3):432-465.

- 59.Grinnage-Cassidy W. Why, 2019. Microaggressions Aren’t So Micro [Video]. YouTube. TEDxYouth@UrsulineAcademy. https://youtube/Z7l194OXxYo. Published May 3 2019. Accessed 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 31 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)