INTRODUCTION

Over 25 million Americans have limited English proficiency (LEP) and are particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes due to language barriers.1 Professional interpreter use is associated with improved clinical care for patients with LEP.2 By contrast, the use of untrained interpreters puts patients and providers at risk for communication errors and may jeopardize patient safety.3 In 2013, the Department of Health and Human Services’ released the enhanced National Cultural and Linguistically Appropriate Service (CLAS) Standards which mandate that all healthcare organizations that receive federal funding provide language assistance from trained interpreters and translated vital documents.4 Real-world provision of these services in the ambulatory setting is unknown.5 We used national survey data to assess physician-reported use of professional interpreters in US ambulatory care practices and to compare differences between health care organizations and solo and group practices, which are exempt from CLAS standards.

METHODS

We analyzed the National CLAS Physician Survey, a cross-sectional survey of non-federally employed, office-based physicians conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from August to December 2016.6 The survey was administered to a stratified sample of physicians eligible for the 2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). The National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board approved NAMCS with waivers of informed consent.

The CLAS survey uses the same multistage estimation procedure used by NAMCS to produce national estimates. The procedure has three components: inflation by reciprocals of the selection probabilities, adjustment for nonresponse, and a ratio adjustment to fixed totals. Adjustments for nonresponse were made by shifting the weights of non-respondent physicians to those who were deemed respondents within the same census region, specialty type, and practice type as the non-respondents.6

We examined responses to three questions: (1) Do you use interpreters when working with patients who have limited English proficiency?” (2) “How often do you use each type of interpreter?” (3)“What types of materials, in language(s) other than English, are available to your patients?”

We compared characteristics of respondents who did and did not report regular use of professional interpreters using chi-squared tests. Regular use was defined as “often” using professional interpreters when working with patients who have LEP. We then examined the use of other interpreter types and the availability of translated materials. All analyses were weighted to produce national estimates and conducted using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

The weighted analytic sample included 273,796 outpatient physicians. The majority of respondents reported using interpreters when working with patients with LEP (78.7%; 95% CI, 71.9%, 85.5%), but only 29.5% (95% CI 22.9%, 36.1%) reported regularly using professional interpreters (Table 1). Female physicians were more likely to regularly use professional interpreters than male physicians (39.3% vs. 24.8%, P = .02). Compared to other practice settings, physicians working in solo or group practices were less likely to regularly use professional interpreters (21.2% vs. 47.8%, P < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Physicians Who Often, Ever, and Never Use Interpreters when Working with Patients who Have Limited English Proficiency

| Often use professional interpreters when working with patients who have limited English proficiency * | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value | |

| Weighted, N (%) | 80,717 (29.5) | 193,079 (70.5) | |

| Physician characteristics, weighted % | |||

| Age | |||

| Under 50 | 38.5 | 61.5 | 0.06 |

| ≥ 50 years | 24.8 | 75.2 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 39.3 | 60.7 | 0.02 |

| Male | 24.5 | 75.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity † | |||

| White | 33.2 | 66.8 | 0.36 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 27.8 | 72.2 | |

| Other ‡ | 20.4 | 79.6 | |

| Did not answer | 30.4 | 69.6 | |

| Multilingual | |||

| Yes | 29.8 | 70.2 | 0.94 |

| No | 29.6 | 70.4 | |

| Did not answer | 24.6 | 75.4 | |

| Specialty | |||

| Primary care | 26.5 | 73.5 | 0.60 |

| Surgical specialty | 30.7 | 69.3 | |

| Medical specialty | 33.2 | 66.8 | |

| Practice characteristics, weighted % | |||

| Practice type | |||

| Solo or group practice | 21.2 | 78.8 | < 0.001 |

| Healthcare organizations § | 47.8 | 52.2 | |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 28.7 | 17.1 | 0.97 |

| Midwest | 32.2 | 67.8 | |

| South | 29.5 | 70.5 | |

| West | 27.8 | 72.2 | |

*Unweighted denominator of 365 respondents includes 340 respondents who completed the full National Physician CLAS survey and 25 partial respondents who completed the language portion of the National Physician CLAS survey

†We combined survey results on race and ethnicity into a combined race/ethnicity variable. Anyone who was categorized as “Yes, Hispanic, Latino/a, or Spanish origin” by the survey was considered “Latino/Hispanic” in our analyses. “White” respondents were those who were categorized as “white” and “No, Hispanic, Latino/a, or Spanish origin.” “Other” were those categorized as “other” and “No, Hispanic, Latino/a, or Spanish origin”

‡Other race, as grouped by the National Physician CLAS Survey, includes Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Other Asian, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, and Other Pacific Islander

§Healthcare organizations include freestanding clinics and urgent care centers, community health centers, non-federal government clinic, mental health center, family planning clinic, health maintenance organization or other prepaid practice, and academic medical center practices (faculty practice plans)

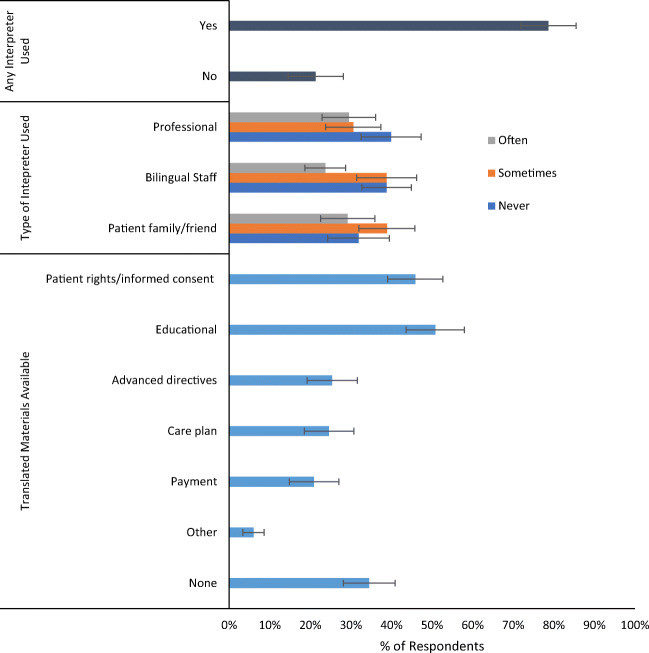

While physicians reported frequently using bilingual staff and patient family for interpretation, 39.9% of respondents reported never using professional interpreters (Fig. 1). Provision of translated written materials varied, with 50.8% providing educational materials, 25.4% providing advanced directives, 20.9% providing care plans, and 34.5% providing no translated materials.

Figure 1.

Use of interpreters and availability of translated materials. Note: Proportions are survey-weighted. Error bars represent 95% CIs. Survey participants could respond often, sometimes, rarely, never for use of staff/contractor trained as a medical interpreter, bilingual staff, and patient’s relative or friend. We combined sometimes/rarely to “sometimes.”

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that fewer than one-third of outpatient physicians reported regularly using a trained professional interpreter when communicating with patients with LEP, that 40% never used professional interpreters, and that translated materials were infrequently available. Providers in solo/group practices were less likely to report using professional interpreters compared to those in other practice settings, suggesting that the CLAS standards, which are mandatory for healthcare organizations and not solo or group practices, may have a modest impact on increasing access to linguistically appropriate services. Limitations of this study include reliance on physician self-report and lack of distinction on the provision of services for different languages.

Beyond the legal mandate, the use of professional interpreters has been associated with improved patient satisfaction, safety, and clinical outcomes.2 Our findings demonstrate that despite clinical evidence and legal requirements, professional interpreters remain greatly underused. Enforcement of CLAS requirements may improve uptake of professional interpreters. However, interpreter services are expensive, and penalties should be designed in such a way as to not further burden clinical settings that disproportionately care for LEP and other underserved populations.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board approved NAMCS with waivers of informed consent.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parker MM, Fernández A, Moffet HH, Grant RW, Torreblanca A, Karter AJ. Association of Patient-Physician Language Concordance and Glycemic Control for Limited-English Proficiency Latinos With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of Medical Interpretation and Their Potential Clinical Consequences: A Comparison of Professional Versus Ad Hoc Versus No Interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. Published online 2013.

- 5.Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA. Do Hospitals Measure up to the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services Standards? Med Care. 2010;48(12):1080–1087. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. 2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Supplement on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services for Office-based Physicians (National CLAS Physician Survey), Public-use data file and documentation. Published online 2016. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Datasets/NAMCS.