Abstract

Background:

Mood and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent and comorbid with HIV/AIDS. However, there is a paucity of research on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural interventions (CBI) for common mental disorders in HIV-infected adults. The present study sought to review the existing literature on the use of CBI for depression and anxiety in HIV-positive adults and to assess the effect size of these interventions.

Methods:

We did duplicate searches of databases (from inception to 17–22 May 2012). The following online databases were searched: PubMed, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PsychArticles.

Results:

We identified 20 studies suitable for inclusion. A total of 2886 participants were enroled in these studies, of which 2173 participants completed treatment. The present review of the literature suggests that CBI may be effective in the treatment of depression and anxiety in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Significant reductions in depression and anxiety were reported in intervention studies that directly and indirectly targeted depression and/or anxiety. Effect sizes ranged from 0.02 to 1.02 for depression and 0.04 to 0.70 for anxiety.

Limitations:

Some trials included an immediate postintervention assessment but no follow-up assessments of outcome. This omission makes it difficult to determine whether the intervention effects are sustainable over time.

Conclusion:

The present review of the literature suggests that CBI may have a positive impact on the treatment of depression and anxiety in adults living with HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Depression, Anxiety, Cognitive therapy, Psychotherapeutic interventions

1. Background

With increased access to and use of highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART), HIV has become a more manageable chronic disease. Chronicity however, is coupled with an increase in the number of lifetime emotional and physical challenges faced by people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Crepaz et al., 2008). Common mental disorders (CMDs) such as depression and anxiety are highly prevalent and comorbid with HIV/AIDS. Compared to the general population and comparable HIV-negative individuals, evidence suggests that the prevalence of depression is two to four fold higher in HIV-infected individuals (Bing, 2001; Ciesla and Roberts, 2001; Morrison, 2002; Rabkin, 1997). Of a US sample of 2864 adults receiving care for HIV, nearly half received a clinical diagnosis of a psychiatric illness (Bing, 2001). Depression (36%) and generalised anxiety disorder (GAD, 16%) were the commonest disorders (Bing, 2001). However, despite current estimates, depression and anxiety may be under diagnosed and under treated in routine HIV medical care (Asch, 2003). Prevalence rates of depression in HIV-positive individuals range from 5% to 20% across a majority of studies (Cruess et al., 2003). Depression can predate an HIV diagnosis and be a side effect of medication. HIV disease can also exacerbate depressive episodes (Sherr et al., 2011). Evidence suggests that aside from depression being a secondary diagnosis to HIV/AIDS, depressive symptoms measured over time are associated with faster progression of the disease after five years (Leserman, 1999). Moreover, depression significantly worsens HAART adherence and HIV viral control (Horberg, 2008). In light of this evidence, untreated depression in PLWHA poses a public health problem and there is a need to understand what interventions work best to treat depression in PLWHA.

Similarly, anxiety can precede HIV infection but it can also be triggered by an HIV diagnosis and by the challenges faced by infected individuals over the course of infection (Clucas et al., 2011). Therefore, recognising and treating CMDs in HIV is important. Notably, there is a paucity of research assessing treatment for CMDs in low-and middle-income countries(LMICs), which have higher rates of HIV/AIDS. Untreated CMDs in PLWHA in these countries can therefore impede efforts to contain the epidemic.

Cognitive therapy (CT) and cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) were developed for treating specific psychiatric disorders more than forty years ago. Since then, empirical testing of these therapeutic approaches has progressed substantially (Beck, 2005). While the efficacy of other psychological interventions for the treatment of CMDs in the general population has been established, a growing body of research supports the effectiveness of CT/CBT in treating depression and, to a lesser extent, various anxiety disorders (Beck, 2005). Cognitive-behavioural interventions (CBIs) are one of the most widely used therapies to improve mental health in the general population (Beck, 2005). CBIs focus on the interaction of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Although there are various CBI techniques, the most common practices focus on altering irrational cognitions related to negative psychological states (e.g., depression, anger, anxiety), correctly appraising internal and external stressors, gaining stress management skills, and developing adaptive behavioural coping strategies (Crepaz et al., 2008). In a review of 16 high-quality meta-analyses of CBT covering 332 studies and 9138 participants, CBT was found to be very effective for unipolar depression, GAD, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder and childhood depressive and anxiety disorders (Butler et al., 2006). Beneficial effects were maintained for substantial periods (e.g. 12 months) across many disorders, including depression and anxiety. CBT has been shown to be superior to antidepressant therapies in the treatment of mild major depressive disorder in adults and was also shown to be at least moderately effective for a number of other psychiatric disorders (Butler et al., 2006). However, it must be noted that assumptions of uniformity across samples, both in the content of therapy and in the training and expertise of therapists, are among the limitations of meta-analytic approaches (Beck, 2005). Although randomized controlled trials provide evidence for the long-term effectiveness of CBT for depression and anxiety in populations that are not infected with HIV, it is unclear whether they are also effective in improving these mental health outcomes in HIV-infected adults and whether these intervention effects are sustained over time (Crepaz et al., 2008). This warrants investigation. In this paper we review the available literature on cognitive-behavioural interventions (CBI) for the treatment of depression and anxiety in HIV-positive adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion criteria

Intervention studies that met all of the following criteria were included:

Cognitive-behavioural interventions designed to assist HIV-infected individuals alter cognitions that aggravate irrational thoughts related to depression and anxiety, to gain skills required to manage and reduce stress, or develop adaptive behavioural coping strategies (Crepaz et al., 2008).

Cognitive-behavioural interventions that were not combined with psychopharmacologic interventions (e.g. antidepressants). Studies where comparator treatments were combined with a psychopharmalogic intervention were included.

Measurement of depression and/or anxiety outcomes using validated instruments.

Randomised controlled trials (RCT).

2.2. Exclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCT) where participants were allowed to self-select an intervention and uncontrolled trials were excluded.

2.3. Search strategy

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library (Central Register of Controlled Trials: CENTRAL) and PsychInfo (PsychArticles) between 17 to 22 May 2012. No limit on the time period was applied to the search. Reference lists of articles identified through database searches and bibliographies of systematic and non-systematic review articles were examined to identify further relevant studies. We included all English language clinical trials. The population included adult men and women already infected with HIV/AIDS. The following search terms were used: ‘cognitive therapy’ and ‘HIV’. The PsychInfo search was implemented using ‘cognitive therapy’ and ‘HIV’ as index terms and in all fields. The PubMed search was implemented using standardised search terms (medical subject search terms; Mesh). By searching for the term ‘cognitive therapy’, all logical subsets or entry terms (synonyms) were included in the search. Some of these terms included: ‘cognitive psychotherapy’ and ‘cognitive behaviour therapy’. No filters were included to ensure that all relevant papers were retrieved. An initial search of titles was undertaken by the reviewer (GS). Studies were included irrespective of sample size and period of follow-up.

2.4. Study selection and data extraction

GS scanned all titles and abstracts that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria of the review and assessed the full text of relevant articles for eligibility. Information was extracted from included studies regarding the population characteristics and sample size, trial design, outcomes measured and main findings.

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Measures of intervention effect

Outcomes (i.e. depression and anxiety) were measured using different scales across the included studies and as a result, outcomes were combined by standardising them based on their standard deviations. We therefore calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) using means and standard deviations for the outcome measures across treatments. However, only SMDs for CBIs were calculated. Effect sizes for studies reporting non-CBI interventions were not calculated. If means and standard deviations were not provided, SMDs were not computed, unless other data were provided. For example, if standard errors were provided, data were still utilised to calculate SMDs. SMDs are useful when there is a lack of direct comparability across studies and outcome measures. A computer programme called Review Manager (Rev-Man 5.1) was used to generate SMDs, 95% confidence intervals, and forest plots (The Nordic Cocharane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011). Posttest or follow-up scores of the active treatments were compared with those of the control group. This calculation expresses the magnitude of a specific treatment effect as compared to alternative treatments or control conditions. This was calculated by subtracting the posttest mean of the control condition from the posttreatment mean of the treatment group and dividing by the pooled standard deviation. The overall effect (Z) and probability value were also computed for all studies.

2.5.2. Assessment of heterogeneity

In order to assess how comparable studies in the meta-analysis were, we assessed heterogeneity using a Chi2 statistical test, and also by I2. These tests describe the percentage of variability in study effects that is due to real heterogeneity rather than chance.

2.5.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias within each included study based on the following five domains, with review authors’ judgments of low risk of bias, high risk of bias and uncertain risk of bias: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and other sources of bias.

3. Results

3.1. Description of studies

The reviewed trials are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Cognitive Behavioural Interventions (n=20).

| Study | Sample characteristic (Enroled/completed) | Evaluation design | Description of intervention | Main outcomes assessed | Other measured outcomes | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||||||

| Carrico et al. (2005) * a | HIV+ART-naïve males (129/44). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBSM/WLC. Follow-up: IP, 6-months | Group CBSM. Duration: weekly for 10 weeks (135 min). Deliverer: clinical health psychology graduates | Depression (BDI) | Health status, life events, social support | Men in the CBSM group reported significant decreases in depression over 6-month follow-up compared to controls |

| Carrico et al. (2005) * b | HIV+ males on ART (129/49). No group differences in demographics. 47% on ART | Randomised CBSM/WLC. Follow-up: IP, 6-, 12-months | Group CBSM. Duration: weekly for 10 weeks (135 min). Deliverer: clinical health psychology graduates | Depression (POMS; BDI) | Social support, immune status | Men in the CBSM group experienced significant reductions in depression through the 6- to 12-month follow-up |

| Carrico (2006) | HIV+ males on ART (130/98). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBSM-MAT/MAT only comparative trial. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM-MAT. Duration: weekly for 10 weeks (135 min). Deliverer: clinical health psychology graduates | Depression (POMS). |

Coping, medication adherence | Men in the CBSM group reported significant decreases in depression after 10 weeks compared to the MAT only group |

| Chan (2005) | HIV+ males (16/13). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBT/WLC trial. Follow-up: IP | Group CBT. Duration: weekly for 7 weeks (2 h). Deliverer: clinical psychologist | Depression (CES-D) |

Health related quality of life | Men in the CBT group showed significant reductions in depression compared to control condition |

| Eller (1995) | HIV+ males and females on ART (81/69). No group differences in demographics | Randomised guided imagery/PMR/WLC trial. Follow-up: 6-weeks post intervention | Individual guided imagery/PMR. Duration: 6 weeks. Deliverer: audio tapes used at home | Depression (CES-D) |

Cellular immunity, fatigue | PMR and guided imagery showed reductions in depression. PMR resulted in CD4 enhancement |

| Jones et al. (2010) | HIV+ women (451/387) | Randomised CBSM/control information-education intervention trial. Follow-up: IP, 12-months | Group CBSM. Duration: 10 weeks (90 min). Deliverer: not reported | Depression (BDI); Anxiety (STAI) | Cognitive behavioural self-efficacy | CBSM showed reductions in depression and anxiety postintervention and long-term in comparison with controls |

| Kraaij (2010) | HIV+ males and females on ART (73/55). 52.3% on ART | Randomised CBS/SWI/WLC. Follow-up: IP, 2-months | Individual self-help CBT. Duration: weekly for 4 weeks (60 min). Deliverer: workbook and CD-Rom | Depression (HADS) | Health characteristics (time since diagnosis, CD 4 cell count, viral load, use of medication | CBS showed significant improvements in depression compared to SWI and WLC |

| Markowitz (1998) | HIV+ males and females (101/69). Predominantly MSM. No group differences in demographics | Randomised IPT/CBT/SP/SWI trial. Follow-up: IP | Individual IPT/CBT/SP. Duration: 8–16 sessions (30–50 min). Deliverer: professional therapists | Depression (BDI; Ham-D) | CD 4 T-lymphocyte count, physical functioning, medication adverse effects | All interventions reduced depression. IPT and SWI showed greater improvement than CBT & SP |

| Safren (2009) | HIV+ males and females on ART (45/36) | Randomised CBT/single session intervention control comparative trial. Follow-up: IP; 3-, 6-, 12-months | Individual CBT. Duration: 10–12 sessions (50 min). Deliverer: clinical psychologists | Depression (BDI; HAM-D and independent-assessor rated Clinical Global Impression) | Medication adherence, HIV plasma RNA concentration | Individuals who received CBT showed improvements in depression relative to the comparison group at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments |

| Safren et al. (2012) | HIV+ male and female injection drug users on ART (89/89) | Randomised CBT/single session intervention control comparative trial. Follow-up: IP, 3-, 6-, 12 months | Individual CBT. Duration: 10–12 sessions (50 min). Deliverer: clinical psychologists | Depression (MADRS and independent-assessor rated Clinical Global Impression) | Medication adherence, HIV plasma RNA concentration | CBT showed greater improvement in depression than controls. After treatment discontinuation, depression gains were maintained at follow-up assessments |

| Depression and anxiety | ||||||

| Antoni (1991) | HIV+ ART-naïve MSM (47/47). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBSM/assessment only control condition trial. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM. Duration: twice weekly for 10 weeks. Deliverer: clinical psychologists | Anxiety, depression (POMS) | Trait anxiety, stressful life events, physical activity, sleep, high-risk sexual activities, immunologic status | CBSM did not show any pre-post test changes in depression or anxiety but did result in CD4 enhancement |

| Antoni (2000) * a | HIV+ MSM (74/73). No group differences in demographics. 30 men on ART | Randomised CBSM/WLC. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM. Duration: Once a week for 10 weeks (135 min each). Deliverer: clinical health psychology postdoctoral students | Anxiety and overall mood (POMS; Ham-D; HARS) | Anger, 24 h urinary norepinephrine, immunologic status | CBSM participants showed significantly lower anxiety and overall mood scores than controls |

| Antoni (2000) * b | HIV+ MSM (59/59). No group differences in demographics. 29 men on ART | Randomised CBSM/WLC. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM. Duration: Once a week for 10 weeks (135 min each). Deliverer: clinical health psychology postdoctoral students | Depression, anxiety (Ham-D; POMS) | Gross neurocognitive dysfunction, anger, fatigue, vigour, confusion, 24 h urinary cortisol, immunologic status | CBSM participants showed significantly lower depressed affect and anxiety than controls |

| Berger (2008) | HIV+ males and females on ART (104/77). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBSM/standard care only control trial. Follow-up: 1-, 6-, 12-months | Group CBSM. Duration: 12 sessions (2 h). Deliverer: psychotherapist | Depression and anxiety (MOS-HIV; HADS) | CD4 lymphocyte cell Count, HIV-1 RNA, health related quality of life, medication adherence | CBSM showed alleviation of depressive and anxiety symptomatology at baseline and 12 month follow-up |

| Carrico (2009) | HIV+ males and females (936/624). No group differences in demographics. 69% on ART | Randomised CBT/WLC. Follow-up: IP; 5-, 10-, 15-, 20-, 25-months | Individual CBT. Duration: 15 sessions (90 min). Deliverer: facilitators | Depression and anxiety (BDI; STAI) | Burn out, perceived stress, positive affect, positive states of mind, coping self-efficacy, perceived social support | No intervention-related reductions in depression or anxiety were evident across the follow-up period |

| Cruess (2000) | HIV+ MSM (65/57). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBSM/WLC condition trial. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM. Duration: Once a week for 10 weeks (2.5 h). Deliverer: clinical health psychology postdoctoral students | Depression, anxiety (POMS) | Anger, fatigue, vigour, confusion, free testosterone, cortisol | CBSM participants showed significantly lower depression and anxiety scores than controls |

| Inouye et al. (2001) | HIV+ males and females on ART (40/39). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBS-M/WLC condition trial. Follow-up: IP | Individual CBS-M. Duration: 14 (60–90 min) sessions over 7 weeks. Deliverer: clinicians | Depression, anxiety (POMS) | Physical health status, coping, health attitudes, anger, vigour, confusion, fatigue, overall mood | CBS-M significantly improved depression, anxiety and overall mood compared to controls |

| Kelly (1993) | HIV+ ART-naïve men (115/68). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBT/SP/assessment only control condition trial. Follow-up: IP; 3-months | Group CBT/SP. Duration: 8 sessions (90 min each). Deliverer: psychologists, counsellors or psychiatry residents | Depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety (CES-D; SCL-90-R) | Global psychiatric distress, illicit drug use, somatisation, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility | CBT and SP groups showed reductions in depression and anxiety. CBT resulted in less frequent drug use at follow-up |

| Lutgendorf (1997) | HIV+ MSM (52/39). No group differences in demographics. 21 men on ART | Randomised CBSM/WLC. Follow-up: IP | Group CBSM. Duration: 10 sessions (135 min each). Deliverer: clinical psychologists | Depression, anxiety (BDI; POMS) | Total mood disturbance, clinical variables (immunology) | The intervention showed reductions in anxiety, depression and total distress |

| Molassiotis et al. (2002) | HIV+ males and females on ART (46/36). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBT/PSC/assessment only comparison group trial. Follow-up: IP; 3-;6-months | Group CBT/PSC. Duration: 12 sessions over 3 months (2 h). Deliverer: clinicians | Depression; anxiety (POMS) | Quality of life, anger, vigour, confusion, fatigue | CBT and PSC improved depression, anxiety and overall mood |

| Mulder et al. (1994) | HIV+ ART-naïve MSM (39/27). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBT/ET/WLC comparative trial. Follow-up: IP, 3-, 6-months | Group CBT/ET. Duration: 17 sessions over a 15 week period. Deliverer: trained therapists | Depression, anxiety. psychiatric symptoms/distress (POMS; BDI; GHQ) | Anger, fatigue, vigour, psychiatric symptoms, coping strategies, emotional expression, social support | CBT and ET groups showed reductions in depression, psychiatric distress, and in total POMS scores IP only |

| Sikkema et al. (2004) | HIV+ males and females (268/235). No group differences in demographics | Randomised CBT/individual therapy on request comparative trial. Follow-up: 2 weeks PI | Group CBT. Duration: 12 weeks (90 minutes). Deliverer: therapists | Depression, anxiety, overall psychological distress (SCL-90-R; SIGH-AD) | AIDS-related bereavement | The group intervention demonstrated reductions in depression and psychiatric distress |

Note: ART=antiretroviral therapy; CBSM=cognitive-behavioural stress management; CBT=cognitive-behavioural therapy; SP=supportive psychotherapy; ET=experiential group psychotherapy; WLC=wait-list control; PMR=progressive muscle relaxation; IPT=interpersonal psychotherapy; SWI=imipramine with SP; CBS-M=cognitive-behavioural self-management; PSC=peer support/counseling; CBSM-MAT: CBSM combined with medication adherence training; CBS=cognitive-behavioural self-help program; SWI=structured writing intervention; MSM=men who have sex with men; IP=immediate postintervention assessment; POMS=Profile of Mood States; CES-D=The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCL-90-R=The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; GHQ=General Health Questionnaire; HAM-D=Hamilton depression rating scale; HARS=Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; STAI=State/Trait Anxiety Inventory; SIGH-AD=structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression and anxiety scales; SCID-IV=structured clinical interview for DSM-IV); MOS-HIV=the HIV Medical Outcome Study questionnaire; HADS=the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MADRS=Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

Antoni (2000)a,b and Carrico et al. (2005)a,b are both single studies reported in separate publications.

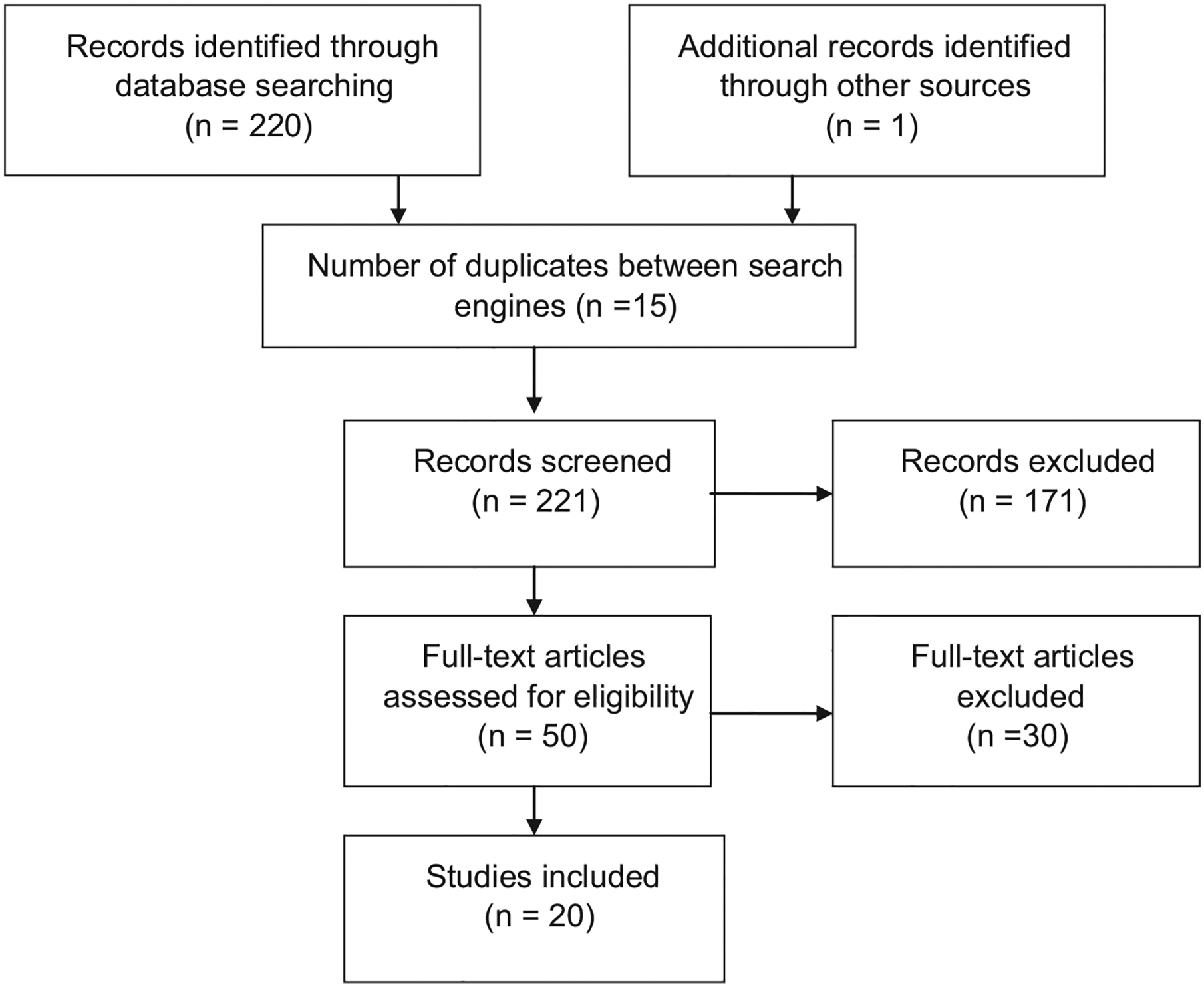

3.2. Results of the search

All databases searched yielded abstracts, and there were 15 duplicates between the databases. All the studies had been published in peer-reviewed journals. Two hundred and twenty one abstracts were identified and reviewed through the search (including duplicates). One article was sourced from reference lists of other manuscripts. Of the 221 abstracts identified, 50 passed the first screening of titles and abstracts. The full text of these 50 articles were examined and 20 studies were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Studies were excluded if they were: the same study reporting outcomes in multiple publications, of no relevance to the present review, systematic or nonsystematic review articles, not conducted in the population of interest, were in a language other than English or did not meet all of the inclusion criteria for trial selection outlined in the methods section of this paper.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of review process.

3.3. Participants

A total of 3089 participants were enroled in these studies, of which 2290 participants completed treatment. Nine studies included male participants only (Antoni, 1991, 2000; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2006; Chan, 2005; Cruess, 2000; Kelly, 1993; Lutgendorf, 1997; Mulder et al., 1994). Ten studies included a mix of men of women (Berger, 2008; Carrico, 2009; Eller, 1995; Inouye et al., 2001; Kraaij, 2010; Markowitz, 1998; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012; Sikkema et al., 2004). Only one study included female participants only (Jones et al., 2010). Not all studies reported the number of men and women at baseline and some only reported the number of men and women who completed treatment. However, a total of 1978 males and 827 females were reported across all studies.

3.4. Location of studies

The majority of trials were conducted in the USA. However, two studies were conducted in the Netherlands (Kraaij, 2010; Mulder et al., 1994) and two in Hong Kong (Chan, 2005; Molassiotis et al., 2002). One study was conducted in Switzerland (Berger, 2008).

3.5. Interventions

The majority of studies (n=13) were group interventions, with only 7 studies reporting on individual interventions. The literature search revealed four studies that specifically targeted depression and had a mood disorder as an inclusion criterion (Kelly, 1993; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012). Of these four studies, only one reported on anxiety outcomes (Kelly, 1993). However, a specific severity score for anxiety was not an entry criterion for this study. A total of 350 participants were enroled in these studies, of which 262 completed treatment.

There were 16 studies that did not have a mood or anxiety disorder as an inclusion criterion, but reported on depression and/or anxiety outcomes as part of an intervention (Antoni, 1991, 2000; Berger, 2008; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2006, 2009; Chan, 2005; Cruess, 2000; Eller, 1995; Inouye et al., 2001; Jones et al., 2010; Kraaij, 2010; Lutgendorf, 1997; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Mulder et al., 1994; Sikkema et al., 2004). A total of 2536 participants were enroled in these studies, of which 1911 completed treatment.

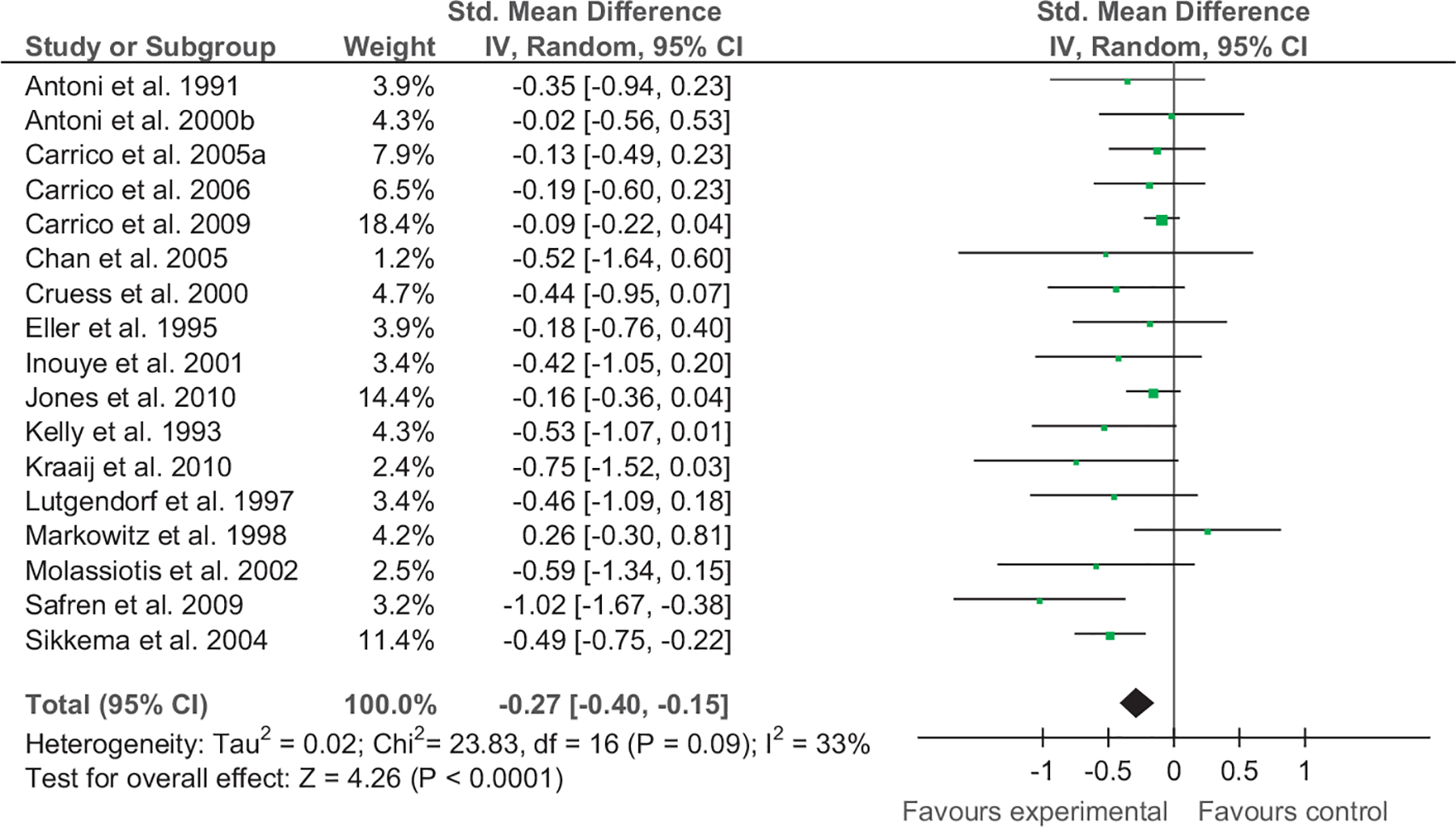

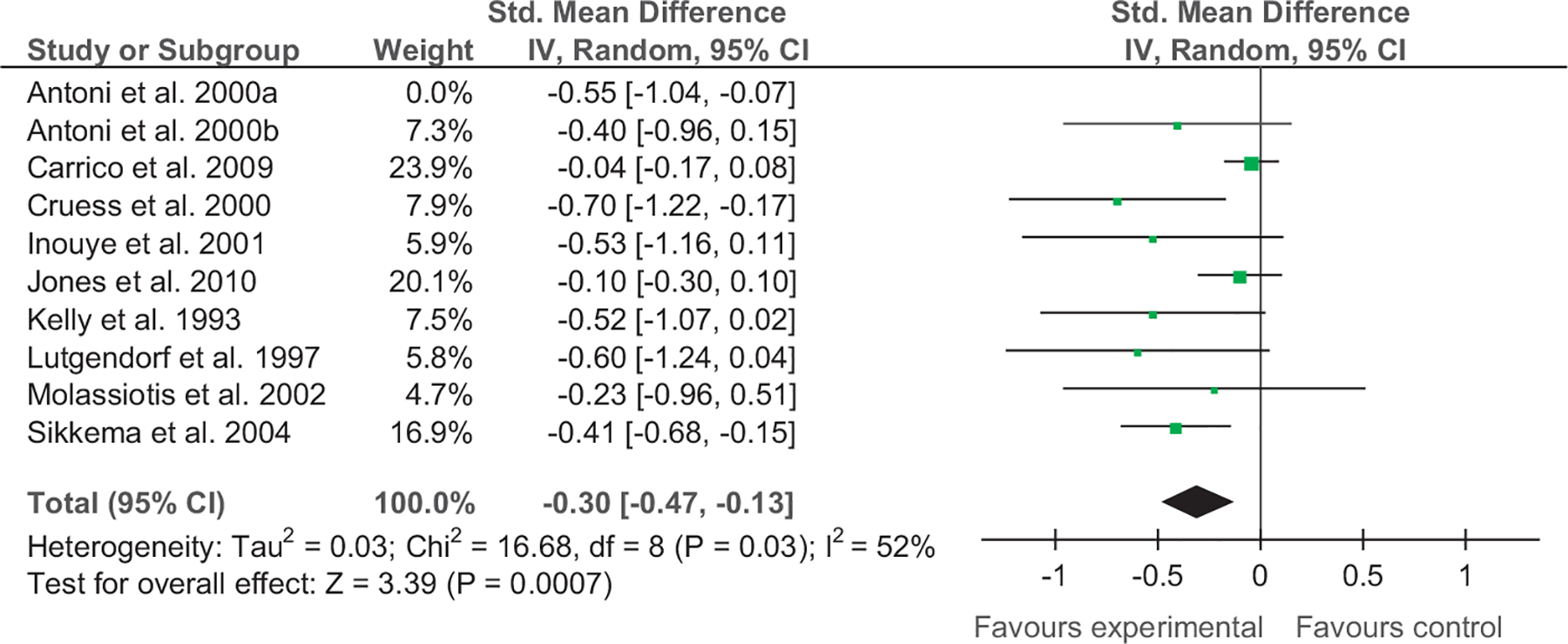

Calculation of SMDs revealed that results ranged from −0.02 to −1.02 for depression immediately postintervention and −0.04 to −0.70 for anxiety immediately postintervention. The overall weighted mean effect size for depression was −0.27 [−0.40, −0.15] and for anxiety −0.30 [−0.47, −0.13]. The test for overall effect for depression was Z=4.26, p<.001 and for anxiety Z=3.39, p<.001. The majority of studies assessed depression and anxiety immediately postintervention. SMDs and 95% confidence intervals for these studies can be seen in Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of CBI vs. comparison for depression (immediate postintervention).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of CBI vs. comparison for anxiety (immediate postintervention).

SMDs for depression at the 3 month follow-up were as follows: −0.11 [−0.64, 0.42] (Kelly, 1993 p. 1679), −0.51 [−1.25, 0.23] (Molassiotis et al., 2002), and −0.54 [−0.98, −0.10] (Safren et al., 2012). The overall weighted mean effect size for depression at the 3 month follow-up was −0.39 [−0.70, −0.08]. The test for overall effect was Z=2.46, p=.01. SMDs for depression at the 6 month follow-up were as follows: −0.33 [−0.69, 0.03] (Carrico et al., 2005), and −0.47 [−0.94, −0.01] (Safren et al., 2012). The overall weighted mean effect size for depression at the 6 month follow-up was −0.38 [−0.67, −0.10]. The test for overall effect was Z=2.64, p<.01. SMDs for depression at the 12 month follow-up were as follows: 0.11 [−0.47, 0.69] (Carrico et al., 2005), −0.13 [−0.33, 0.07] (Jones et al., 2010), and −0.46 [−0.96, 0.03] (Safren et al., 2012). The overall weighted mean effect size for depression at the 12 month follow-up was −0.16 [−0.38, 0.06]. The test for overall effect for was Z=1.40, p=.16.

SMDs for anxiety at the 3 month follow-up were as follows: −0.12 [−0.66, 0.41] (Kelly, 1993), and −0.10 [−0.83, 0.63] (Molassiotis et al., 2002). The overall weighted mean effect size for anxiety at the 3 month follow-up was −0.11 [−0.54, 0.32]. The test for overall effect was Z=0.51, p=.61. Lastly, SMDs for anxiety at the 12 month follow-up were as follows: −0.07 [−0.27, 0.12] (Jones et al., 2010). The overall weighted mean effect size for anxiety at the 12 month follow-up was −0.07 [−0.27, 0.12]. The test for overall effect was Z=0.73, p=.46.

3.6. Number and content of sessions

The group-based therapy sessions ranged from 7 to 20 sessions while individual-based therapy sessions ranged from 4 to 16 sessions. Eight studies administered group cognitive behavioural stress management (CBSM) interventions (Antoni, 1991, 2000; Berger, 2008; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2006; Cruess, 2000; Jones et al., 2010; Lutgendorf, 1997). Five studies administered group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions (Chan, 2005; Kelly, 1993; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Mulder et al., 1994; Sikkema et al., 2004).

Five studies administered individual CBT interventions (Carrico, 2009; Kraaij, 2010; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012). Other individual-based therapies included guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation (Eller, 1995), and cognitive-behavioural self-management (CBS-M) (Inouye et al., 2001).

3.7. Control comparison groups

The majority of studies included a wait-list control condition (WLC) (Antoni, 2000; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2009; Chan, 2005; Cruess, 2000; Eller, 1995; Inouye et al., 2001; Kraaij, 2010; Lutgendorf, 1997; Mulder et al., 1994; Sikkema et al., 2004). Four studies included a control comparison group with no active intervention (i.e. an assessment only condition) (Antoni, 1991; Berger, 2008; Kelly, 1993; Molassiotis et al., 2002). Three studies included an active control comparison group (i.e. an alternative psychotherapy) (Carrico, 2006; Jones et al., 2010; Markowitz, 1998). In two studies, control subjects received a single session intervention (Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012).

3.8. Outcome measures

3.8.1. Depression

Eight different measures of depression were administered in the included studies. The majority (9 studies) assessed depression using the same measure, namely the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (Antoni, 1991, 2000; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2006; Cruess, 2000; Inouye et al., 2001; Lutgendorf, 1997; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Mulder et al., 1994). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was also a common outcome measure among studies (Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2009; Jones et al., 2010; Lutgendorf, 1997; Markowitz, 1998; Mulder et al., 1994; Safren, 2009). Three studies used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Ham-D) (Antoni, 2000; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009) and three studies utilised the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Chan, 2005; Eller, 1995; Kelly, 1993). Other outcome measures included the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (Kelly, 1993; Sikkema et al., 2004), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Berger, 2008; Kraaij, 2010), the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton depression and anxiety scales (SIGH-AD) (Sikkema et al., 2004), and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Safren et al., 2012).

3.8.2. Anxiety

Six different measures of anxiety were used in the included studies. The majority (6 studies) assessed anxiety using the same measure, namely the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (Antoni, 1991, 2000; Cruess, 2000; Inouye et al., 2001; Lutgendorf, 1997; Molassiotis et al., 2002). Other outcome measures included the State/Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Carrico, 2009; Jones et al., 2010), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Berger, 2008), the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (Kelly, 1993; Sikkema et al., 2004), and the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression and Anxiety scales (SIGH-AD) (Sikkema et al., 2004).

3.9. Heterogeneity

The test for heterogeneity for depression (immediately postintervention) revealed a Chi2 statistic of 23.83, p=0.09, I2=33%. In examining anxiety immediately postintervention, the test for heterogeneity revealed a Chi2 statistic of 16.68, p=0.03, I2=52%. For depression at the 3 month follow-up period, results revealed no heterogeneity between included studies, Chi2=1.59, p=0.45, I2=0%. Similar results were evident for anxiety at the 3 month follow-up period, Chi2=0.00, p=0.95, I2=0%. For depression at the 6 month follow-up period, results revealed no heterogeneity between included studies, Chi2=0.22, p=0.64, I2=0% and for depression at the 12 month follow-up period, results revealed a Chi2 statistic of 2.37, p=0.31, I2=16%.

3.10. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

With regards to reporting of methodological features (n=20), we found moderate bias in reporting of important methodological aspects. Nine studies reported using sequence generation (Antoni, 2000; Berger, 2008; Carrico, 2009; Eller, 1995; Jones et al., 2010; Kraaij, 2010; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012), three reported allocation concealment (Berger, 2008; Markowitz, 1998; Safren et al., 2012), four reported blinding of outcome assessors (Carrico, 2006; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012), and eight studies adequately addressed incomplete outcome data (Berger, 2008; Carrico et al., 2005; (Carrico, 2006, 2009; Markowitz, 1998; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012; Sikkema et al., 2004).

4. Discussion

Worldwide, by the end of 2010, an estimated 34 million individuals were living with HIV/AIDS. An estimated 2.7 million individuals were newly infected with HIV in 2010 (UNAIDS, 2012). Common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are highly prevalent and comorbid with HIV/AIDS. With the growing number of HIV infections every year, it is expected that the number of individuals with comorbid depression and anxiety will increase (Olatunji et al., 2006). Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders constitute 13% of the global burden of disease (Collins, 2011), with depression the third leading contributor to the global disease burden (Collins, 2011). Relative to the disease burden, there is a paucity of research around preventing and treating mental, neurological, and substance use disorders (Collins, 2011). “Where there are effective treatments, they are frequently not available to those in greatest need” (Collins, 2011). In turn, internationally established treatment guidelines for depression and anxiety in HIV are lacking (Olatunji et al., 2006). Future research should therefore focus on rigorous testing of interventions for depression and anxiety in the context of HIV/AIDS.

There is some evidence that treatment gains may be maximised by selecting psychosocial interventions such as CBT over pharmacologic interventions. In a study comparing a cognitive therapy (CT) intervention to continued use of antidepressant medication, it was found that depressed individuals withdrawn from CT were less likely to relapse during continuation than individuals withdrawn from medication (30.8% vs. 76.2%) and no more likely to relapse than individuals who continued taking medication (30.8% vs. 47.2%) (Hollon, 2005). The present review of the literature does suggest that cognitive-behavioural interventions (CBI) may be effective in the treatment of depression and anxiety in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Significant reductions in depression and anxiety were reported in intervention studies directly and indirectly targeting depression and/or anxiety. Individuals infected with HIV/AIDS who received an intervention, mainly cognitive restructuring and coping skills to reduce stress, showed a significant reduction in depressive and anxiety symptomatology compared to those who did not receive such an intervention.

Of all the studies reviewed, 9 studies revealed a significant intervention effect on depression and/or anxiety immediately postintervention. It is noteworthy that only nine studies assessed for intervention effects immediately postintervention. The duration of these studies ranged from 6 to 16 weeks of treatment, respectively (Antoni, 2000; Carrico, 2006; Chan, 2005; Cruess, 2000; Eller, 1995; Inouye et al., 2001; Lutgendorf, 1997; Markowitz, 1998; Sikkema et al., 2004). Eleven studies assessed for longer term effectiveness, of which 6 reported that depression and/or anxiety gains were maintained at follow-up. The duration of follow-up ranged from 2 to 25 months, (Berger, 2008; Carrico et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2010; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012). Interestingly, 3 out of the 7 studies that yielded treatment gains in the long term (6–12 months) administered stress management skills training (CBSM). It appears CBSM is an efficacious method of improving mental health (Berger, 2008; Carrico et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2010). This was also the case for immediate postintervention assessments (Antoni, 2000; Carrico, 2006; Cruess, 2000; Lutgendorf, 1997). All these CBSM studies involved a more intensive intervention period (10 or more sessions), perhaps providing these individuals with more opportunities to practice and reinforce the skills learnt. The remaining studies revealed significant CBI effects immediate postintervention, however, there was no evidence for longer term effectiveness at follow-up assessment. One possible explanation for this is that without booster sessions, there may be a gradual decline in the practice of skills to correctly assess irrational thoughts and improve coping and stress management skills (Crepaz et al., 2008). Findings of a previous meta-analysis of CBI in HIV-positive individuals suggest that coping with emotional stress over the course of HIV infection may require on-going behavioural reinforcement to prevent relapse (Crepaz et al., 2008).

Of all the studies reviewed, only two reported no significant intervention effects on depression and anxiety (Antoni, 1991; Carrico, 2009). In the study by Antoni and colleagues, results revealed that the group CBSM intervention did not show any pre-post test changes in depression. The CBSM group did, however, show increases in CD4 T lymphocyte counts (Antoni, 1991). The authors suggest that the findings may have been due to the small sample size and the large number of analyses conducted, thereby increasing the chance of a type I error (Antoni, 1991). In the study conducted by Carrico and colleagues, despite the large sample size (n=936), results revealed no intervention related reductions in depression or anxiety through the 25-month follow-up period (Carrico, 2009). Although the treatment focused on managing stress and implementing effective coping responses, it focused extensively on providing cognitive-behavioural skills training to decrease sexual risk taking and enhance self-care behaviours such as ART adherence. This may explain the lack of significant intervention effects on depression or anxiety observed at 5 months or across the 25-month follow-up period (Carrico, 2009). The authors conclude that more intensive mental health interventions may be necessary to improve depression and anxiety among HIV-positive individuals (Carrico, 2009).

Standardised mean differences (SMDs) could not be calculated for all studies as some studies did not report means and standard deviations (Mulder et al., 1994). However, for the studies that did report adequate data to calculate SMDs, results ranged from −0.02 to −1.02 for depression and −0.04 to −0.70 for anxiety, respectively. While small SMDs were found for some studies indicating that CBI were minimally effective in reducing depressive symptomatology (Antoni, 2000; Carrico et al., 2005; Carrico, 2006; Eller, 1995; Jones et al., 2010), a number of studies had SMDs in the small and medium range (Cruess, 2000; Inouye et al., 2001; Safren et al., 2012). Medium to large SMDs for treating depression were found close to half of all studies (Berger, 2008; Chan, 2005; Kelly, 1993; Kraaij, 2010; Lutgendorf, 1997; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012; Sikkema et al., 2004). Collectively, while the total SMD was small (−0.27, CI −0.40, −0.15), the test for overall effect was significant, Z=4.26, p<.001. Heterogeneity ranged from 0% to 33% for depression immediately postintervention to 12 month depression.

In treating anxiety, two studies were found to have very small SMDs (Carrico, 2009; Jones et al., 2010), while a number of studies had small to medium (Antoni, 2000; Inouye et al., 2001; Kelly, 1993; Molassiotis et al., 2002; Sikkema et al., 2004) or medium to large (Berger, 2008; Cruess, 2000; Kelly, 1993; Lutgendorf, 1997; Sikkema et al., 2004) SMDs. Collectively, the total SMD was small (−0.30, CI −0.47, −0.13) with the test for overall effect significant, Z=3.39, p<.001. Heterogeneity ranged from 0% to 52% for anxiety immediately postintervention to 3 month anxiety at follow-up.

In order to maximise treatment outcomes in HIV, high levels of adherence to antiretroviral therapies (ART) are necessary. Common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety can act as barriers to ART adherence (Mugavero, 2006; Safren, 2001). In assessing studies included in the present review, it became clear that the majority of studies included participants who were on ART. Only four studies included ART-naïve participants (Antoni, 1991; Carrico et al., 2005; Kelly, 1993; Mulder et al., 1994). The ART status of trial participants was not clearly specified in a number of studies (Chan, 2005; Cruess, 2000; Jones et al., 2010; Markowitz, 1998; Sikkema et al., 2004). However, despite the fact that the majority of HIV-infected trial participants were on ART, only four studies assessed and reported ART adherence outcomes (Berger, 2008; Carrico, 2006; Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012). While Berger, 2008 and Carrico, 2006 reported no significant changes in treatment adherence between experimental and control groups, two studies reported a significantly greater improvement in treatment adherence in the experimental condition relative to the comparison condition (Safren, 2009; Safren et al., 2012).

The literature suggest that CBIs can be effective in improving depression and anxiety in HIV-infected individuals. There is a trend that CBI improves depression at 3-month and 6-month follow-up. However, there are few studies available to fully assess the long-term outcomes. There are limitations worth mentioning. Some trials included an immediate postintervention assessment but no follow-up assessments of outcome. This omission makes it difficult to determine whether intervention effects are sustainable over time. Multiple assessments over a longer duration would also be a valuable inclusion in future trials. In addition, studies in heterosexually infected samples are needed as most studies have been conducted in homosexual men and other high risk groups such as injection drug users. Only one study exclusively focused on women (Jones et al., 2010). Given that women (particularly minorities) are at increased risk for HIV particularly in developing countries (e.g. India, South Africa), future studies will need to focus more on HIV-positive women in low and middle income settings, especially given that HIV prevalence tends to be higher in these contexts.

There are several limitations of this review that warrant mention. First, no search strategy can guarantee the identification of all relevant research, and omission of important studies remains a possibility and may contribute to bias in inferences drawn. Second, selection or reviewer bias may be a possibility given that studies were not screened or abstracted in duplicate. However, despite these limitations, this review adds substantially to available evidence on CBI for mood and anxiety disorders and symptoms in HIV infected patients that could be useful for both clinical and research decision making.

5. Conclusion

The present review of the literature suggests that CBI may have a positive impact on the treatment of depression and anxiety in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Based on the assessment of risk of bias, an important recommendation for research in this area is for researchers to better document and report trial design and execution. Researchers should pay particular attention to gathering detailed histories and documenting exclusions, reasons for dropout, and the handling of missing data. Reporting of the methods of randomisation should also be given more attention in future studies. Studies should endeavour to follow up participants for at least one year rather than the short or no follow-up periods that characterise some studies in the field. Finally, there were no studies from LMICs in the present review. Given that HIV is more prevalent in LMICs, there is arguably a need for future studies in these countries.

Role of funding source

This work is based upon research supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation, the MRC Unit on Anxiety and Stress Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, University of Stellenbosch, Cape Town, South Africa and the Claude Leon Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

References

- Antoni MH, 1991. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention buffers distress responses and immunologic changes following notification of HIV-1 seropositivity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59, 906–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, 2000. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reduces distress and 24-hour urinary free cortisol output among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 22, 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch SM, 2003. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: who are we missing? Journal of General Internal Medicine 18, 450–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, 2005. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S, 2008. Effects of cognitive behavioral stress management on HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell counts and psychosocial parameters of HIV-infected persons. AIDS 22, 767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, 2001. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58, 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT, 2006. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review 26, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, 2006. Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-positive gay men treated with HAART. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 31, 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Pereira DB, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Lechner SC, Schneiderman N, 2005. Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on mood, social support, and a marker of antiviral immunity are maintained up to 1 year in HIV-infected gay men. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 12, 218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Lechner SC, Schneiderman N, 2005. Cognitive-behavioural stress management with HIV-positive homosexual men: mechanisms of sustained reductions in depressive symptoms. Chronic Illness 1, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, 2009. Randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for HIV-positive persons: an investigation of treatment effects on psychosocial adjustment. AIDS and Behavior 13, 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan I, 2005. Cognitive-behavioral group program for Chinese heterosexual HIV-infected men in Hong Kong. Patient Education and Counseling 56, 78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE, 2001. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 158, 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clucas C, Sibley E, Harding R, Liu L, Catalan J, Sherr L, 2011. A systematic review of interventions for anxiety in people with HIV. Psychology, Health and Medicine 16, 528–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, 2011. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature 475, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Crepaz N, Passin WF, Herbst JH, Rama SM, Malow RM, Purcell DW, Wolitski RJ, HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team., 2008. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions on HIV-positive persons’ mental health and immune functioning. Health Psychology 27, 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, 2000. Cognitive-behavioral stress management increases free testosterone and decreases psychological distress in HIV-seropositive men. Health Psychology 19, 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Evans DL, Repetto MJ, Gettes D, Douglas SD, Petitto JM, 2003. Prevalence, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of mood disorders in HIV disease. Biological Psychiatry 54, 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller LS, 1995. Effects of two cognitive-behavioral interventions on immunity and symptoms in persons with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 17, 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, 2005. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs. medications in moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horberg MA, 2008. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 47, 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye J, Flannelly L, Flannelly KJ, 2001. The effectiveness of self-management training for individuals with HIV/AIDS. Joint Army–Navy Assessment Committee 12, 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Ishii Owens M, Lydston D, Tobin JN, Brondolo E, Weiss SM, 2010. Self-efficacy and distress in women with AIDS: the SMART/EST women’s project. AIDS Care 22, 1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, 1993. Outcome of cognitive-behavioral and support group brief therapies for depressed, HIV-infected persons. American Journal of Psychiatry 150, 1679–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, 2010. Effects of a cognitive behavioral self-help program and a computerized structured writing intervention on depressed mood for HIV-infected people: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling 80, 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, 1999. Progression to AIDS: the effects of stress, depressive symptoms, and social support. Psychosomatic Medicine 61, 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, 1997. Cognitive-behavioral stress management decreases dysphoric mood and herpes simplex virus-type 2 antibody titers in symptomatic HIV-seropositive gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65, 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, 1998. Treatment of depressive symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 55, 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molassiotis A, Callaghan P, Twinn SF, Lam SW, Chung WY, Li CK, 2002. A pilot study of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and peer support/counseling in decreasing psychologic distress and improving quality of life in chinese patients with symptomatic HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS 16, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, 2002. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero M, 2006. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS 20, 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder CL, Emmelkamp PM, Antoni MH, Mulder JW, Sandfort TG, de Vries MJ, 1994. Cognitive-behavioral and experiential group psychotherapy for HIV-infected homosexual men: a comparative study. Psychosomatic Medicine 56, 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, 2006. Review of treatment studies of depression in HIV. Topics in HIV Medicine 14, 112–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, 1997. Psychopathology in male and female HIV-positive and negative injecting drug users: longitudinal course over 3 years. AIDS, 11; 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, 2009. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology 28, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH, 2012. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80, 404–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, 2001. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: life-steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research and Therapy 39, 1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, Catalan J, 2011. HIV and depression—a systematic review of interventions. Psychology, Health and Medicine 16, 493–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Tate DC, Difranceisco W, 2004. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a group intervention for HIV positive men and women coping with AIDS-related loss and bereavement. Death Studies 28, 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Nordic Cocharane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.1.

- UNAIDS, 2012. Worldwide HIV & AIDS statistics. [Online]. Available: 〈http://www.avert.org/worldstats.htm〉.