Abstract

HIV disparities among Young, Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) persist despite concerted efforts to increase uptake of prevention tools like HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We conducted in-depth interviews with 25 YBMSM (aged 18–29 years old) to understand factors contributing to PrEP access in Birmingham, Alabama. We identified that one major barrier to PrEP uptake was intersectional stigma related to their multiple identities and contributed to lack of feeling able to accept their sexual identities. Facilitators of validation and acceptance of sexual identity were strong social support networks, which participants reported consisted of, not only other gay and bisexual Black men, but also Black women, an unexplored social support group among YBMSM networks. However, participants felt that internal, perceived and experienced homophobia were exacerbated in Southern, Black communities due to perceived values surrounding masculinity, which were reinforced by religious doctrine. Looking forward, public health officials will need to add additional resources to support interventions that have meso-level impact to effectively change social norms as a critical determinant of individual-level prevention practices within this at-risk group and their social networks.

Keywords: Prexposure prophylaxis, HIV, sexual identity

Introduction

The United States (US) HIV epidemic is facing a turning point. There is now the potential to end the epidemic, with one key tool to do so being highly effective biomedical prevention strategies like HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The larger Ending the HIV Epidemic (EtHE) plan has prioritized protecting people at risk for HIV through increased utilization of PrEP in areas of the US disproportionately impacted by the epidemic.1 Specifically, high HIV incidence rates are seen among young, Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) in the Southern US, who face high rates of discrimination, HIV-related stigma, homophobia and overall disenfranchisement.2–4 PrEP, a daily pill that can reduce risk of HIV acquisition by up to 95%, has been underutilized by those populations who could benefit most, including YBMSM.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently estimate that over 1.1 million people in the US have an indication for PrEP, with almost half being Black men and women. However, Black men and women receive approximately only 11% of PrEP prescriptions.6 And little over a quarter of PrEP prescriptions are written in the South, which not only has the highest HIV rates but also the highest AIDS-related mortality.6,7 If PrEP can be scaled up among at-risk groups like YBMSM, as a part of a cohesive plan to improve engagement in the HIV care continuum, modeling studies suggest that two-thirds of HIV infections may be averted in ten years-time, essentially attenuating health inequities.8

To inform these efforts, we need a holistic understanding of how the lived experiences of YBMSM in the South shape their health beliefs and attitudes towards PrEP. Numerous studies have found that intersectional stigma (the synergistic, co-occurring associations between social identities), related to sexual orientation and race, predicts higher risk sex and decreased access to HIV testing among BMSM.9–12 These multiple identities often result in minority stress, which is strongly linked to life stress as well as poorer mental health.13 Prior research with YBMSM living in Birmingham, AL, supported these findings where we found several barriers to PrEP uptake, including: stigma related to their intersecting identities within a perceived repressive Southern environment and community that idealizes masculinity; silence in the Black community around sexual health; PrEP stigma; medical distrust; and low perceived PrEP need.14 Even more so, internalized, perceived and experienced homophobia was experienced by all participants and prevented some from fully accepting their sexuality (i.e. their sexual identity and sexual attractions). As one participant aptly reported, “If you can accept your sexuality no matter what comes against you or whatever circumstances you face, I feel like this is the first step into being, into living and having a healthier sex life.” Many participants emphasized this sentiment, describing the many obstacles YBMSM face in in accepting their sexual identity and that acceptance is a crucial first step needed for them to be open to sexual health prevention strategies like PrEP. Given these findings, we sought to further explore facilitators and barriers to acceptance of sexual identity in this group by conducting a secondary analysis of these interviews, as a means to understand how to better develop tailored HIV prevention strategies related to PrEP in vulnerable Southern communities. To do this, we examined individual, interpersonal and meso-level (i.e. groups in a community, including schools, workplaces and churches) experiences and interactions that effect intersectional stigma as well as contribute to acceptance of sexuality.

Methods

Design

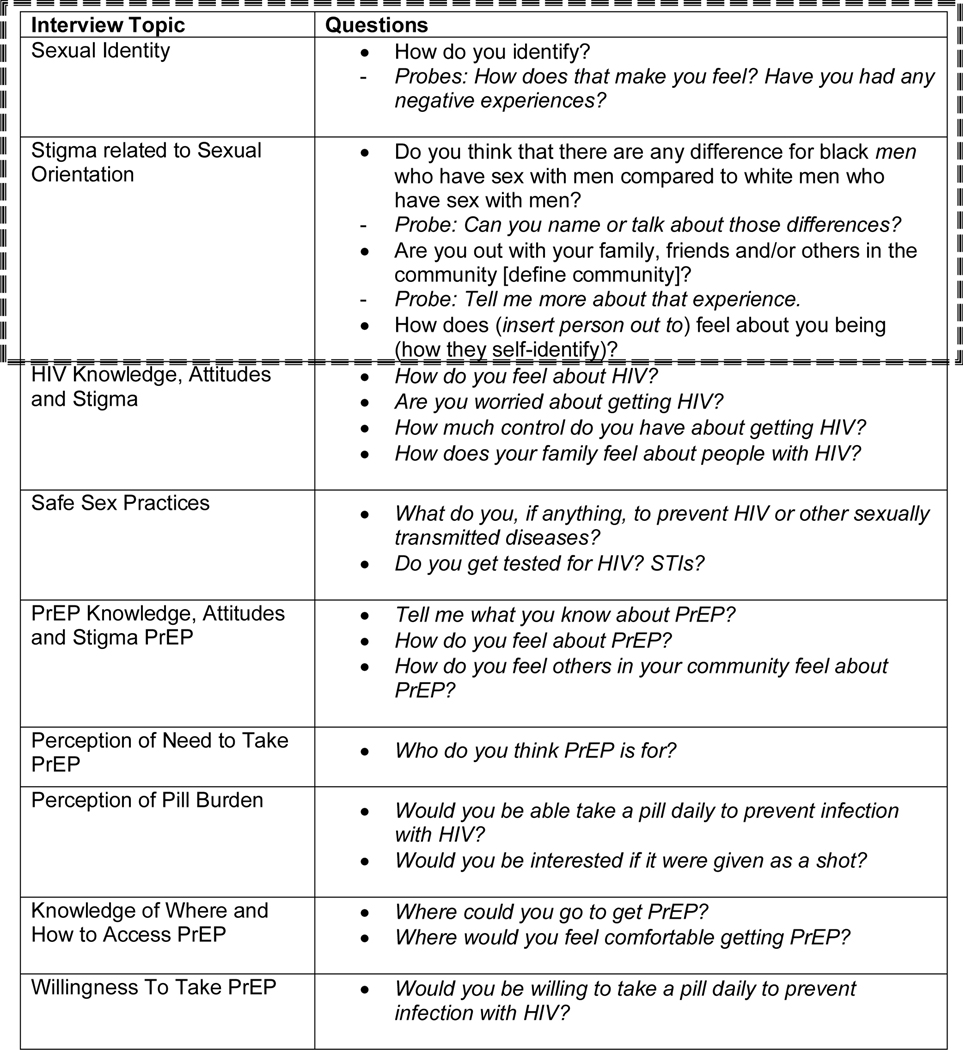

This was a qualitative study conducted in Birmingham, Alabama with the goal of understanding facilitators to uptake of PrEP utilizing a phenomenology approach by exploring past lived experiences of participants to better elucidate this health phenomenon on a deeper level.15 Questions included in the interview guide mapped to constructs within the Andersen and Newman Framework of Health Services Utilization.16 Specifically, questions with guided probes focused on understanding predisposing characteristics, defined as characteristics not directly related to the health behavior, enabling factors that positively or negative impact a health behavior and overall perceived need. To further explore the topic of acceptance of sexuality among participants, we conducted additional, second-level fine coding that involved axial coding focused on text related to sexual identity, coming out and social networks that either support or hinder acceptance.17 The majority of these codes mapped to four questions and related probes in our qualitative, in-depth interview guide (Figure 1). All transcripts of the twenty-five in-depth interviews, conducted between February and September of 2017, were reviewed in several iterations. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board approved study procedures. Prior to each interview, written informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1.

Interview Topics and Questions

Sample and Procedure

Twenty-five cis-gender, self-reported HIV-negative BMSM between the ages of 16–29 were recruited through convenience sampling. All participants were recruited from the Birmingham-Hoover metropolitan statistical area with the aid of AIDS Service Organizations. Interviewers for this study were a cis-gender, Black woman and cis-gender BMSM who prior to conducting interviews were trained on US HIV epidemiology, HIV prevention tools including PrEP, and qualitative interviewing techniques. Training included mock interviews with experienced UAB staff. A $30 incentive was given to each participant after completion of a brief demographic survey, and prior to completion of the interviews that lasted approximately one to one and a half hours.

Data Management and Analysis

Digital audio recordings from each session were securely uploaded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Audio recordings and transcripts were stored in encrypted drives. NVivo software version 12 (QSR International) was used to aid in coding. All transcripts of the twenty-five in-depth interviews, conducted between February and September of 2017, were reviewed in several iterations. Based on prior research illustrating the central role that internal and perceived homophobia plays in the ability of YBMSM to accept sexual health services like PrEP, the researchers focused on conducting inductive, thematic coding to understand the journey for YBMSM living in the South on the way to accepting and valuing their sexual identity.14 Initial theoretical saturation was based on the overarching study goal of understanding YBMSM perceptions around PrEP utilization, which was used to determine if further participant sampling was needed for the study. In this secondary analysis, coders used inductive thematic saturation to obtain a more refined understanding of acceptance of sexual identity among participants, since this was identified as a major barrier to PrEP utilization. Data sampling continued based on the development of new nodes or codes, which were discussed through an iterative process between two coders.18 A preliminary codebook was developed based on parallel coding of four transcripts, to determine initial inductive codes. Analytic memos were shared between coders and refinement of the codebook was continued through an iterative process to determine major themes.

Results

The median age of participants was 24 years old (range 18–29 years old) with the majority of participants identifying as gay, MSM or same gender loving (64%; Table I)). Of note, one participant identified as heterosexual, but reported sex with other men. All participants were aware of PrEP and 16% were current PrEP users who all reported acceptance of their sexual identity. The majority also reported having health insurance (84%) and a regular source of healthcare (72%). Of the 25 participants, 16 (64%) reported having positive feelings about their sexual identity, which were primarily discussed by participants when responding to the following questions in the interview guide: “How do you identify”, “Are you out with your family, friends and/or others in the community?” and “How does your (insert person out to) feel about you being ___ (how they self-identify)?”. (Table I)

Table I.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Characteristics | Total = 25 N (%) |

|---|---|

| Median Age | 24 |

| Has Health Insurance | |

| Yes | 21 (84) |

| No | 4 (16) |

| Regular Source of Healthcare | |

| Yes | 18 (72) |

| No | 7 (28) |

| Self-Described Sexual Identity | |

| Gay/MSM/Same gender loving | 16 (64) |

| Bisexual or Queer | 6 (24) |

| Gender Nonconforming | 2 (8) |

| Heterosexual | 1 (4) |

| Aware of PrEP | 25 (100) |

| On PrEP | 4 (16) |

| Positive Feelings about Sexual Identity | 16 (65) |

Common Emerging Themes

We identified three major themes when exploring barriers and facilitators for self-acceptance of sexual identity. These themes were the following: 1) Homophobia (internal, perceived and experienced); 2) Social-support networks facilitated self-validation of sexual identity and; 3) Key social support figures varied and consisted of Black MSM as well as Black women. Within each theme, we discovered several subthemes related to the journey of self-acceptance, elaborated below.

Homophobia

Many participants felt that homophobia influenced their journey to accepting their sexuality. Three types of homophobia (internalized, perceived and experienced) were reported by participants. Of note, internalized homophobia experiences described primarily during early adolescence appeared to have the greatest impact on participants’ ability to find “peace” with their sexuality.

Internalized homophobia

Internalized homophobia, defined as the personal negative feelings expressed by participants related to their sexual identity, was universally experienced among our participants with most feeling that this was worse at a younger age.

“I have always had attraction to guys. But, I felt like it was something that was wrong with me growing up. There has always been emotions, negative emotions connected to it.” (108)

One participant even reported attempted suicide at a younger age, due to his feelings of isolation and inability to accept his sexual identity.

“…now they don’t bother me as much, because I know who I am. The, I just wanted to get away. I tried to commit suicide more than one time just to try to escape. But as an adult, I mean, I deal with it now, but it doesn’t bother me as much.” (124)

A sub-theme emerged related to how the coming-out experience effected participants’ personal feelings about their sexuality, with a minority of participants reporting that with greater acceptance they no longer felt the need for “coming-out”.

“I kind of just live my life. I don’t feel the need to come out to anybody.” (120)

A few participants described how rejection from loved ones after coming out led to heightened internalized homophobia and self-loathing.

“… it’s like you go through a process of grief because it’s like I’ve lost a part of my relationship with my parents in a way, so I have to really figure out in myself how I can love myself and make up for not having a relationship with my parents in that way.” (109)

“… you should not have to be like, ‘Oh, I finally have somebody that accepts me.’ It should be… your family accepts you and this is just the person that you click with.” (118)

Some participants felt that the source of their stigma was their belief that their sexual identity was an affront to their religious values.

“I think most of my negative experience was internal. It all had to do with my religion. I wanted a good relationship with God. I wanted to be in right standing with God… for the greater part of my life, my spirituality and my sexuality could not co-exist.” (108)

One participant even described attempts to immerse himself in religious activities, because of his personal dislike of his sexual identity and the purported impact this may have on his soul.

“But I cannot change it. I tried. I really tried. I tried praying. I tried going to church. I tried all of this stuff. But it just something that I cannot change.” (106)

Perceived homophobia

Many participants expressed that members of their social networks had negative feelings related to the participant’s sexual identity. A source of these perceptions was the belief that being gay in the Black community did not reflect ideals around masculinity.

“I feel like Black people, they are more negative about it. The way that they go about it. The way that they raise their children who are heterosexual to act toward homosexual people.” (106)

“They use the word ‘sissy’ all the time and stuff like that. They are like – I mean I do not identify with…. If you tell someone you are gay, you are trying hard not to be feminine.” (114)

Experienced homophobia

Finally, a majority of participants described experiences of being treated poorly due to their identity, with a few reporting physical trauma usually in their early adolescence. These experiences happened among varied persons within their networks, including family, friends and members within their church.

“I had been coming to the church, but this particular day they just decided to put hands on me and pray about my sexuality. And I was like how are you just going to…I said even if I wasn’t, I said I never told anybody at the church that I was a homosexual male.” (112)

Physical trauma varied in intensity from small altercation, to one participant requiring hospitalization.

“….when I was in the tenth grade. I was jumped by eight boys because I was gay. It wasn’t something that anybody would want because it’s like I was hospitalized for three days after. It was a life-changing moment because it was like you don’t expect stuff like this to happen to you at school because you’re standing up for what you believe in or what you feel is right.” (105)

As a result of internalized, perceived and experienced homophobia, a few participants felt that they lived double lives, due to the need to keep their identity hidden within their community.

“Kind of conflicted sometimes because I feel like, not that I’m two different people, but I can’t bring my whole self to the table. I feel like there’s so much I have to offer, but it’s -- I always have to weigh it out in my mind if what I want to share is worth disturbing the peace.” 117

Social-support networks were important in validation of sexual identity

Many participants in the study explicitly stated the importance of social support networks on the journey to self-acceptance. Specifically, participants frequently discussed emotional support. Emotional support was felt to be critical for gaining self-acceptance, feeling love for themselves and validating their sexual identity. Participants reported validation from peers, family and friends when they received acceptance, encouragement and love from these social-support networks. There did not appear to be a difference in the intensity or necessity of this emotional support based on type of support group (e.g., family vs friends).

“My twin brother …was telling me the other day ‘Bro, you’ve got to live for you and really work on loving yourself because at the end of the day that’s all that matters.’” (109)

“And my family they love me and they treat me with respect and kindness and whatever I need they give.” (116)

A sub-theme also arose about the negative effects that occur when some participants felt a lack of social support from their network. Participants reported that if they felt unaccepted, judged or disrespected by their support networks, this led to feelings of invalidation of their sexual identity. Again, participants described multiple types of networks (including family and friends) when discussing these feelings of invalidation and emphasized lack of support as pervasive throughout the Black community.

“My parents know that I’m same gender loving but they don’t talk about it. That’s a type of rejection for me. Pretending like something doesn’t exist, that’s a different type of rejection.” (109)

“I think that’s why I think people have risky sex, really. Without them knowing it, they’re trying to act out the validation that they don’t get from people who they feel like they should get it from.” (109)

When discussing networks that were non-supportive, participants most frequently discussed reactions from male family members to their sexual identity. Although one participant described a father who surprised him with acceptance, several other participants described a lack of emotional support from fathers, or even outright hostility.

“It was kind of a negative experience with my father. We had that conversation at the age of 25. Now, I have always said prior to that, it was not that he did not know. It was that it was something that he did not want to acknowledge. Or, he was in denial about. It is pretty amazing how they work actually.” (108)

“I think my dad probably took it the hardest… My dad is like my best friend. I think when I told my dad, I did not talk to him for like two weeks. I mean, I was miserable. I do not know if my dad was miserable. But, I think he just was not ready for like that conversation. Even now, I am like dating someone. My dad like just refers to him as a friend.” (114)

One participant even reported that his father also had sex with men, but disowned him upon learning his sexual identity; this story illustrated the complexity of understanding acceptance and stigmatization for YBMSM in Southern communities.

“…my dad disowned me… But my dad actually dates males as well, which is weird. But yeah and he doesn’t…his wife found out. That was one night he got drunk. But I’ve seen him before talk to another guy and yeah, he disowned me because of something he…I don’t know what it was. It was different. I said ‘Why would you disown me when you do the same thing?’ But he told me I wasn’t his son.” (112)

Key social support figures varied and consisted of Black MSM as well as Black women

Social-support networks described by the participants were usually small and often diverse, consisting of members within the LGBTQ community, heterosexual men as well as Black women. Some participants expressed a need to have a diverse group of friends that did not only include other YBMSM, suggesting they received different types of support from different people within their network.

“This is going to sound kind of weird, but I don’t really have a lot of gay friends that I’m close to like that. I have gay friends, but my best friends aren’t gay.” (120)

Seventeen of the 25 participants reported that BMSM friends were important sources of social support and, overall, described a loving brotherhood in this community. Many participants felt that when surrounded by other Black gay men, they felt more comfortable with their multiple stigmatized identities.

“The ones that like me, they proud of me. The one that’s in the community, in the LGBT community, they proud of me.” (103)

“It’s great to have people that I can relate to in more than one way. Besides being Black people, we also LGBTQ identified. So it’s just the more intersections that we had in common, the better I felt because I felt like I was around people who I didn’t know but we’re just like so relatable, it clicked. It was good having people that I was comfortable with all the way around me.” (121)

One participant described joining a “gay family”, a non-biological family formed of non-familial members within the gay community to provide bonds and support often missing in the household, and feeling acceptance for the first time from this group of BMSM.

“It feels good. It’s the best feeling in the world. The best feeling in the world. I joined a gay family, and it was like the best thing for me, to be myself around these people. So it was like really, really good.” (124)

A few participants also felt that their support groups included accepting members who were heterosexual men. While most participants reported acceptance among their heterosexual friends, they often felt that they had to explain their sexuality more around them.

“I have a home boy that’s actually still our friend. And people be like ‘How are you all friends and he’s straight?’ I was like all straight men don’t feel the same way you do.” (112)

“…with my straight friends, my frat brothers. I would even have conversations, like even when I’m in class I would even put it in.” (116)_

“My fraternity brothers and stuff, they know as well. And it’s a constant battle with them because you never know how you have to engage a situation. And I feel as though you constantly have to explain what your stance is.” (122)

Interestingly, almost two-thirds of participants (63%) also reported supportive Black women as key support figures within their social support networks. There were several different types of interpersonal relationships with women described by our participants, often times among different family members or friends.

“I told my grandma. She just hugged me. She said like ‘Jesus still loves you. I still love you. Do your thing.’” (114)

“…my friends are cool. There is actually, one in particular that kind of brought me out of my shell… she connected me with other people. And I don’t know. It’s just good. It’s good to be able to just be like, so let me tell you about this. That’s happening. Or this app, or this, and ask for advice.” (117)

“All of the men in my group are gay, but I also have a lot of women in my group. There is one that is bisexual; there are others that are straight. We are a different group of people.” (118)

A lot of participants reported key-female figures in their lives who they chose to “come out” to first, because they felt they needed their approval the most. These descriptions often related to mothers and grandmothers of the participants that acted as a major support figure prior to disclosing their sexual identity.

“It was like once I told her, I felt like I was able to tell anybody. Because I feel like if she was able to accept it, then why can’t everybody else.” (105)

One participant recalled that his positive and supportive “coming-out” experience with multiple female relatives provided the nurturement needed for him to fully accept his sexual identity, despite his religious values, and love himself.

“I think most of my negative experience was internal. It all had to do with my religion…It was not until I came out to my sister, and my mom, and my grand mom that I realized that I was. Also, why – and also, with her questioning why I had never felt comfortable to come to her and tell her. I realized that it was not from her. Again, it was not anything external. It was internal.” (108)

Participants also expressed that their first support systems as youths consisted of women, because of their initial reluctance to identify as gay and the ease in which they were able to navigate in social circles consisting of mostly women.

“Actually, the only person that I really knew was my female best friend. So, we went to college together and then I ended up meeting my roommate, who ended up being a really good friend.” (118)

When evaluating types of support received from the LGBT community versus Black women, participants described the same types of genuine empathy and compassion from both groups, but appeared to receive selective emotional support from each group due to differences in the type of relationships and ability to connect over shared lived experiences. While Black female support figures tended to be family members who provided initial support during coming out experiences, other Black men (either within the LGBT community or social networks) were typically not relatives and provided support in later stages of adolescence.

Discussion

This study expands our current knowledge in understanding the barriers to self-acceptance of sexual identity in Southern YBMSM, by allowing a deeper and more nuanced exploration of stigma related to their intersecting identities. For YBMSM living in the South, intersecting stigmas are severe due to living in repressive environments, which impede positive feelings and potentially irreconcilable beliefs surrounding race and its interplay with their sexual identity. More so, these negative feelings surrounding sexual identity have previously been shown to result in lower self-efficacy around HIV prevention strategies like condom use19 and, among this population, was found to be a major barrier to accessing PrEP.14 Internalized homophobic beliefs among this group may also contribute to PrEP-related stigma due to fear that taking PrEP may result in sexual freedom, free of internalized shame.20 In whole, prior studies evaluating barriers to PrEP uptake among BMSM have shown that multiple individual, interpersonal and meso-level (i.e. social networks and community) factors are associated with lack of PrEP utilization. These barriers include PrEP stigma, low perceived PrEP need, racism and medical distrust that are well described in the literature and was also present among our participants.3,14,21 This study uniquely attempts to explore and build upon prior literature by elucidating a barrier identified by our population as the crux for many YBMSM to be unable to access PrEP, acceptance of sexual identity. We found that major barriers to self-acceptance included internalized, perceived and experienced homophobia exacerbated by ideals in the Black community grounded in religious beliefs as well as ideals around masculinity. More so, strong social-support networks that varied in composition, facilitated self-acceptance of sexual identity, with the most commonly reported networks consisting of other BMSM and Black women, who were critical in the journey to acceptance.

YBMSM in this study frequently described having to endure an environment with persistent homophobia that prevented them from feeling emotionally supported or empowered to be comfortable to accept and love themselves. The ubiquitous endorsement of such beliefs speaks to the magnitude of the challenge faced by YBMSM navigating their sexual identities and engaging in HIV prevention practices. In other studies, BMSM specifically reported feeling marginalized both within predominantly white gay communities and their own (Black) communities, which was related to high levels of internalized homophobia.22 In this study, participants expressed feeling marginalized within Black communities due to views that they were not traditionally masculine, and/or based on religious beliefs. Historically, the Black Church has been a prominent force within the Black community that has provided hope and strength, especially during the civil rights movement.23 As such, Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to participate in church and other organized religious activities.24 Given the Church’s reach within the Black community, it has significant influence on accepted behaviors as well as social norms. As such, the rebuke of same-sex relationships in traditional church settings as well as promotion of heterosexism among church leaders may heavily impact community values.25 This may be related to our observations that most participants felt that traditional heterosexual masculinity was valued among their family and friends. The overwhelming need to be viewed as masculine among YBMSM has been reported in other studies located in the Southern US and resulted in outward facing “masks” put on by YBMSM to “role-flex” (i.e., behave in a more stereotypically masculine fashion) in an attempt to gain acceptance within their communities.26 Additionally, in early adolescence, negative effects associated with masculine expression like psychological distress, sexual risks and other negative effects (termed “gender role strain”) can also have heightened impact due to lack of required interpersonal contacts that promote mental and sexual health.27 Going forward, having more YBMSM leaders within Black communities may help facilitate change in heterosexist ideals among their networks and engender a more trusting environment for men to feel comfortable expressing themselves.

We found that social support networks were capable of providing a nuturing space for YBMSM to accept their sexual identity. Social networks by defiinition can vary in composition and generally represent any person with whom participants may interact. Supportive networks here were described as not being solely homogenous in make-up, but also including Black women. Particpants described complex networks, consisting of biological family members, chosen family members and friends, which were valued because of the emotional support participants received. These networks frequently were identified as sources of emotional, instrumental and material support and, in prior studies, these types of support often helped BMSM to engage in PrEP care.28 Our participants expressed how emotional support received from networks in regards to their sexual identity could be beneficial or, conversely, lack of support could negate positive framing around how they identified. When these networks are not supportive, which was described as expressions of judgements towards their sexual orientation, participants felt that many YBMSM may engage in high-risk sexual activity as a way to extend social network connections. This concept is supported in the literature, with evidence that social support mediates the relationship between not only high-risk sexual behavior for BMSM but also substance use.29 For YBMSM who do not feel supported in their daily lives, higher risk behavior may result in HIV infection.

In many cases, negative reactions were from male relatives, with one participant markedly noting that even though his father also had sex with men he still disapproved of his son’s sexual identity. This type of reaction reinforces the perception that many participants voiced about not being able to identify as gay within their communities. This lack of reaffirming messages within social networks disallows open disclsoure of sexual identity for YBMSM. Remaining “in the closet” has been linked to lower awareneess and access to HIV prevention strategies like PrEP and post-exposure prophylaxis and our findings underscore the potential effect social support networks have in participants feeling comfortable to be open about their sexual identity.30

Most participants expressed that social networks that were supportive of their “outness” and sexual identity often consisted of other BMSM in their community as well as Black women, most commonly reported as members of their families such as mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts or cousins. It is known that members of the same social network often share similar social norms that can translate into common beliefs about HIV prevention and health promotion. As it relates to HIV beliefs, research has shown that members of the same network engage in similar sexual risk activities due to shared beliefs.31,32 This is especially true of YBMSM social networks that can be highly dense with racial homogeneity.33 When these networks include YBMSM engaging in high-risk sexual behavior or who stigmatize PrEP, this can affect the social norms within these groups. With this understanding, there is increasing interest in working to improve social support among YBMSM by creating virtual safe spaces for health promotion and discussion about HIV prevention strategies.34 However, few studies have explored how Black women naturally exist within social support networks for YBMSM and evaluated how to strengthen these relationships to facilitate changes in health behaviors. In one randomized control trial evaluating how dyadic relationships could positively impact adherence to antiretroviral therapy for YBMSM living with HIV, over half of participants’ chosen confidantes were female relatives (e.g. mothers, sisters, cousins) or friends.35 This trial also nicely illustrates the influence that Black women can play within YBMSM social support networks. Black women are an underexplored component of support and may be able to help, not only as allies in promoting sexual health, but also as ambassadors to the larger Black community who could facilitate changing social norms overall. Community-level interventions to improve internalized and experienced homophobia among BMSM through targeted media-campaigns has been shown to be an effective strategy in Black communities.36,37 Amplifying stories of YBMSM, supportive voices of Black women allies could influence acceptance of their sexual identity at a community-level and more distally improve inequities in HIV rates. These findings also support a potential role for network-level interventions for YBMSM that are inclusive of supportive Black women to enhance HIV prevention efforts for this highly vulnerable population. Based on results presented in this manuscript, these interventions may focus on strengthening bonds between key support figures like mothers and grandmothers to increase uptake and subsequent persistence in PrEP care. These interventions may incorporate semi-structured conversations and information tools for Black female support figures around sexuality, PrEP indications and resources. Interventions may also focus on supporting YBMSM in early adolescence in identifying key support figures in their networks to engage in discussions around their sexual identity as this appears to be a crucial element to them developing healthy self-images around their sexual identity. Furthermore, current PrEP health service programs that utilize BMSM peer navigation for linkage and persistence in PrEP care could evaluate the role Black women may also play as navigators and/or community health workers for this group.38 Additionally, by including Black women in interventions for YBMSM, Black women may gain more insight into the lived experiences of YBMSM, creating champions within Black communities who can facilitate change in heteronormative values.

This study has several limitations including the participant population, which was recruited in collaboration with two AIDS Service Organizations that provide HIV prevention services to the community, and thus participants may have been more favorable towards HIV prevention behaviors than those not connected with such organizations. Participants were also recruited from metropolitan areas within Alabama and, therefore, their beliefs may not be representative of YBMSM living in rural settings. Another sampling bias likely occurred secondary to this, with our participants largely reporting having stable healthcare and insurance. The lived experiences of YBMSM in the South with higher levels of poverty may therefore not be reflected in this data. Additionally, the authors did not report an intercoder reliability for their analysis and this was due to the epistemological framework used by coders to understand the multiple, lived experiences of participants illustrated above with thick descriptions and samples of the raw data presented in the manuscript.39 Lastly, this qualitative study focused on individual, interpersonal and meso-level relationships that facilitate or impeded acceptance of sexual identity. It did not include an examination of important structural factors linked to stigma, such as local policies, laws, and systems.

Conclusions

In conclusion, interventions for YBMSM to increase uptake of PrEP will require incorporation of complex, tailored and comprehensive strategies to abate stigma and facilitate self-acceptance of sexual identity. This may require working within YBMSM social support networks in an attempt to understand organic bonds that occur among its members, including Black women, especially as they may provide bridging destigmatizing messaging to the larger Black community and aid in changing community social norms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Research and Informatics Service Center for their valuable assistance with study recruitment and especially thank Eddie Jackson and Tammy Thomas for conducting interviews. We also would like to acknowledge AIDS Alabama and Birmingham AIDS Outreach for their help with development of key study materials and aid in recruitment.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Center for AIDS Research P30 AI027767. Latesha Elopre is currently funded through NIH/NIMH 1K23MH112417-01 and the Robert Wood Johnson Harold Amos fellowship.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Latesha Elopre is currently a consulted on the following continuing medication activities: “Building HIV Treatment Capacity in the Family Medicine Clinic,” provided by the North Carolina Academy of Family Physicians and Med-IQ, sponsored by Gilead as well as the Clinical Care Options’ HIV Now Program, entitled “Overcoming Barriers to PrEP Uptake in the United States” also funded by Gilead.

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019; 231(9):844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrington-Sanders R, Wilson CM, Perumean-Chaney SE, Patki A, Hosek S. Brief Report: Role of Sociobehavioral Factors in Subprotective TFV-DP Levels Among YMSM Enrolled in 2 PrEP Trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2019;80(2):160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1351–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Preliminary); vol. 30. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2019. Accessed September 2, 2020.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2017 Update: clinical practice guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed September 2020.

- 6.Ya-lin AH, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(41):1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu H, Mendoza MC, Huang Y-lA, Hayes T, Smith DK, Hoover KW Uptake of HIV preexposure prophylaxis among commercially insured persons—United States, 2010–2014. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016;64(2):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley H, Rosenberg ES, Holtgrave DR. Data-Driven Goals for Curbing the US HIV Epidemic by 2030. AIDS and Behavior. 2019; 23: 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, Millett GA. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(S2):S242–S249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffries WL, Marks G, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Millett GA. Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1442–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ, Schuster MA. Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):875–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simien EM. Doing intersectionality research: From conceptual issues to practical examples. Politics & Gender. 2007;3(02):264–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong CF, Schrager SM, Holloway IW, Meyer IH, Kipke MD. Minority stress experiences and psychological well-being: the impact of support from and connection to social networks within the Los Angeles House and Ball communities. Prevention Science. 2014;15(1):44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elopre L, McDavid C, Brown A, Shurbaji S, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. Perceptions of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2018;32(12):511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merleau-Ponty M, Bannan JF. What is phenomenology? CrossCurrents. 1956;6(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(4). 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cope M. Coding Transcripts and Diaries 27. In: Clifford Nicholas, French Shaun, Valentine Gill, ed. Key methods in geography. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2010;440–451. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, Soto T. The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sexual Research. 2002;39(3):179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubov A, Galbo P Jr, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. Stigma and shame experiences by MSM who take PrEP for HIV prevention: A qualitative study. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2018;12(6):1843–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golub SA. PrEP stigma: implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2018;15(2):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraft JM, Beeker C, Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Finding the “community” in community-level HIV/AIDS interventions: Formative research with young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(4):430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black Church in the African American Experience. 13th ed. London. Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Jackson JS. Race and Ethnic Differences in Religious Involvement: African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. Ethn Racial Stud. 2009;32(7):1143–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valera P, Taylor T. “Hating the sin but not the sinner”: A study about heterosexism and religious experiences among Black men. Journal of black studies. 2011;42(1):106–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: how community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(12):730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. “I always felt I had to prove my manhood”: Homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(1):122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Philbin M, Hirsch JS. Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: insights for high-impact HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men. Health Education & Behavior. 2016;43(2):217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buttram ME, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL. Substance use and sexual risk mediated by social support among black men. Journal of Community Health. 2013;38(1):62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson RJ, Fish JN, Allen A, Eaton L. Sexual identity disclosure and awareness of HIV prevention methods among Black men who have sex with men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2018;55(8):975–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly JA, Amirkhanian YA, Seal DW, et al. Levels and predictors of sexual HIV risk in social networks of men who have sex with men in the Midwest. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(6):483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider J, Michaels S, Bouris A. Family network proportion and HIV risk among black men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999). 2012;61(5):627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amirkhanian YA. Social networks, sexual networks and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;11(1):81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Pike EC, et al. HealthMpowerment. org: building community through a mobile-optimized, online health promotion intervention. Health Education & Behavior. 2015;42(4):493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouris A, Jaffe K, Eavou R, et al. Project nGage: results of a randomized controlled trial of a dyadic network support intervention to retain young black men who have sex with men in HIV care. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21(12):3618–3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hull SJ, Davis CR, Hollander G, et al. Evaluation of the acceptance journeys social marketing campaign to reduce homophobia. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107(1):173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hull SJ, Gasiorowicz M, Hollander G, Short K. Using theory to inform practice: The role of formative research in the construction and implementation of the acceptance journeys social marketing campaign to reduce homophobia. Social Marketing Quarterly. 2013;19(3):139–155. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young LE, Schumm P, Alon L, et al. PrEP Chicago: A randomized controlled peer change agent intervention to promote the adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among young Black men who have sex with men. Clinical Trials. 2018;15(1):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2020;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]