Abstract

Background

Post-acute coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome is now recognized as a complex systemic disease that is associated with substantial morbidity.

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence of persistent symptoms and signs at least 12 weeks after acute COVID-19 at different follow-up periods.

Data sources

Searches were conducted up to October 2021 in Ovid Embase, Ovid Medline, and PubMed.

Study eligibility criteria, participants and interventions

Articles in English that reported the prevalence of persistent symptoms among individuals with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and included at least 50 patients with a follow-up of at least 12 weeks after acute illness.

Methods

Random-effect meta-analysis was performed to produce a pooled prevalence for each symptom at four different follow-up time intervals. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic and was explored via meta-regression, considering several a priori study-level variables. Risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for prevalence studies and comparative studies, respectively.

Results

After screening 3209 studies, a total of 63 studies were eligible, with a total COVID-19 population of 257 348. The most commonly reported symptoms were fatigue, dyspnea, sleep disorder, and difficulty concentrating (32%, 25%, 24%, and 22%, respectively, at 3- to <6-month follow-up); effort intolerance, fatigue, sleep disorder, and dyspnea (45%, 36%, 29%, and 25%, respectively, at 6- to <9-month follow-up); fatigue (37%) and dyspnea (21%) at 9 to <12 months; and fatigue, dyspnea, sleep disorder, and myalgia (41%, 31%, 30%, and 22%, respectively, at >12-month follow-up). There was substantial between-study heterogeneity for all reported symptom prevalences. Meta-regressions identified statistically significant effect modifiers: world region, male sex, diabetes mellitus, disease severity, and overall study quality score. Five of six studies including a comparator group consisting of COVID-19–negative cases observed significant adjusted associations between COVID-19 and several long-term symptoms.

Conclusions

This systematic review found that a large proportion of patients experience post-acute COVID-19 syndrome 3 to 12 months after recovery from the acute phase of COVID-19. However, available studies of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome are highly heterogeneous. Future studies need to have appropriate comparator groups, standardized symptom definitions and measurements, and longer follow-up.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, PACS, Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

A significant number of patients who have recovered from acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection are reporting lasting symptoms resulting in impairment of everyday activities beyond the initial acute period. These post–COVID-19 patients suffer from a phenomenon known as ‘long’ or ‘chronic’ COVID-19, or more recently, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 or post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS) [1,2].

The terms ‘long COVID-19’ and ‘post-acute COVID-19 syndrome’ lack a unified definition. The definition endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the WHO is a set of ‘signs and symptoms that emerge during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, persist for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis’ [3,4]. Many experts, including the NICE panel, also agree with subdividing into two categories: a post–COVID-19 subacute phase of ongoing symptoms that lasts 4–12 weeks after the onset of illness, and a chronic-phase or long COVID-19, defined as symptoms and abnormalities that last more than 12 weeks after the onset of illness and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis [2,4].

This time-frame distinction is important because it differentiates between the acute illness and the possible sequelae of irreversible tissue damage, with varying degrees of dysfunction and symptoms involving several possible conditions as suggested by some experts: post–intensive care syndrome, post-thrombotic or haemorrhagic complications, acute-phase immune-mediated complications, and/or multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children or adults [5]. Globally, the number of patients recovering from COVID-19 infection continues to grow at an unprecedented rate. Therefore, we sought to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature to estimate the prevalence of persistent symptoms and signs at least 12 weeks after acute COVID-19 at different follow-up periods.

Methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline for study design, search protocol, screening, and reporting [6,7].

Literature search and study selection

The literature was searched by a medical librarian for studies of long-term symptoms in patients with COVID-19. Search strategies were created using a combination of keywords and standardized index terms. Searches were originally run in November 2020 and updated in January and September 2021 in Ovid Embase, Ovid Medline (including publication ahead of print, in-process, and other nonindexed citations), and PubMed.gov, which includes preprints. Results were limited to English-language and primarily adult studies. All citations were exported to EndNote, where 4539 duplicates were removed, leaving 3921 citations. Search strategies are provided in the supplementary material (Supplement 1).

Articles were considered eligible for inclusion if they (a) were written in the English language; (b) were peer-reviewed cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies that reported the prevalence of persistent symptoms among individuals with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection; (c) included at least 50 patients; (d) had follow-up of at least 3 months after symptom onset (as per the NICE definition); (e) included only patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; and (f) reported follow-up as mean, median, or a set interval after symptom onset, diagnosis, acute illness, or initial CT chest imaging. Where studies had overlapping investigated populations, studies with larger sample sizes were prioritized, with the remainder excluded [8]. We subsequently identified a subgroup of these eligible studies that included studies with a comparator group consisting of non–COVID-19 cases.

Identification of studies

Six reviewers (OO, MSA, MO, NAF, RA, BAS) examined the titles and abstracts of articles in pairs, using the aforementioned predefined selection criteria. This was followed by a full text review of each article to confirm meeting the eligibility criteria. Disagreements regarding inclusion of a full-text article were discussed and resolved with the senior reviewer (IMT).

Data collection

Data were extracted simultaneously by six reviewers in duplicate (OO, NAF, BAS, RA, MSA, MO) into a prespecified data collection form, with any discrepancies resolved in consultation with the senior reviewer (IMT). Data were collected across the following domains: study characteristics, follow-up method, baseline demographics, and symptom prevalence. Full details of the data collation variables can be found in the supplementary material (Supplement 2).

Quality assessment

The reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies. The critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence consists of nine topics: (a) sample frame suitability, (b) sampling method appropriateness, (c) sample size adequacy, (d) proper description of study subjects and setting, (e) sufficient coverage of the identified sample, (f) usage of valid methods for identification of the condition, (g) standard and reliable way of measuring the condition for all participants, (h) appropriate statistical analysis, and (i) adequate response rate [9]. Each study was assessed across each of these areas, with results reported as Yes, No, or Unclear. Studies were assigned an overall score, reflecting the number of questions with a Yes response.

Studies with a comparator group consisting of non–COVID-19 cases were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [10], which rates observational studies based on three parameters: selection, comparability between exposed and unexposed groups, and exposure and outcome assessment. These three domains can have a maximum score of 4, 2, and 3 stars, respectively. Studies with <5 stars are considered low quality, 5–7 stars moderate quality, and >7 stars high quality.

Data synthesis

Our outcome of interest was prevalence of symptoms at follow-up across four different intervals: 3 to <6 months, 6 to <9 months, 9 to <12 months, and ≥12 months. Due to varying definitions of ‘day 0’ across the literature, we accepted definitions that include COVID-19 symptom onset, COVID-19 diagnosis, or hospital discharge after acute illness. We further categorized studies according to the severity of COVID-19, which was defined in this context as patient setting during acute illness, including outpatient, general inpatient ward, or intensive care unit (ICU) settings. Where symptom prevalence at follow-up was not reported separately based on COVID-19 severity, studies were described as ‘mixed’ (e.g. ‘mixed inpatient/ICU’).

The range of persistent COVID-19 symptoms reported to date was then identified and categorized. Given the interchangeable terminology to refer to symptoms across studies, the following terms were grouped: ‘sleep disturbance’ to refer to insomnia, daytime sleepiness, sleep difficulties, and/or sleep disorders; ‘concentration difficulties’ to refer to confusion, change in level of consciousness, and/or concentration; ‘cognitive impairment’ to refer to cognitive dysfunction, brain fog, and/or cognition difficulties; ‘loss of taste’ to refer to taste dysfunction, alteration of taste, dysgeusia, and parageusia; and ‘loss of smell’ to refer to smell dysfunction, alteration of smell, anosmia, hyposmia, smell blindness, and olfactory disorders. Signs and symptoms were divided into seven main systems: mental health, respiratory system, cardiovascular system, musculoskeletal system, nervous system, gastrointestinal system, and other.

Statistical analyses

The total cohort number and the number of patients with different symptoms or complaints at different follow-up times were extracted from each study and sorted into four intervals: 3 to <6 months, 6 to <9 months, 9 to <12 months, and ≥12 months. We performed separate meta-analyses for the aforementioned follow-up intervals where ≥3 studies reported symptom prevalence at that follow-up interval. The arcsine transformation was used to obtain a pooled estimate of the prevalence of each symptom. Because conventional meta-analysis models assume normally distributed data, arcsine-based transformations are applied to the proportion data to yield better approximations to the normal distribution; they have the important advantage of stabilizing variances [11,12]. We used a DerSimonian and Laird random effect model with the inverse variance method to pool prevalence [13]. We performed subgroup meta-analyses by severity of acute COVID-19 in the included studies, allowing a visual display of heterogeneity due to differences in the severity of illness in reporting studies. We evaluated between-study heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which estimates the variability percentage in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance [14]. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We performed meta-regression to explore between-study heterogeneity. We considered several a priori chosen study-level variables based on clinical plausibility (Supplement 3). Meta-regression was performed for each symptom where ≥10 studies reported prevalence at any given follow-up interval, as per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [15]. The regression coefficients obtained from the meta-regression analyses describe how the outcome variable (the pooled prevalence) changes with a unit increase in the continuous explanatory variable and changes for the category of interest compared to a reference category for a categorical variable. The statistical significance was p < 0.01 for the results of the meta-regression, and we reported if a variable was found to be a significant contributor to heterogeneity. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) [16].

Results

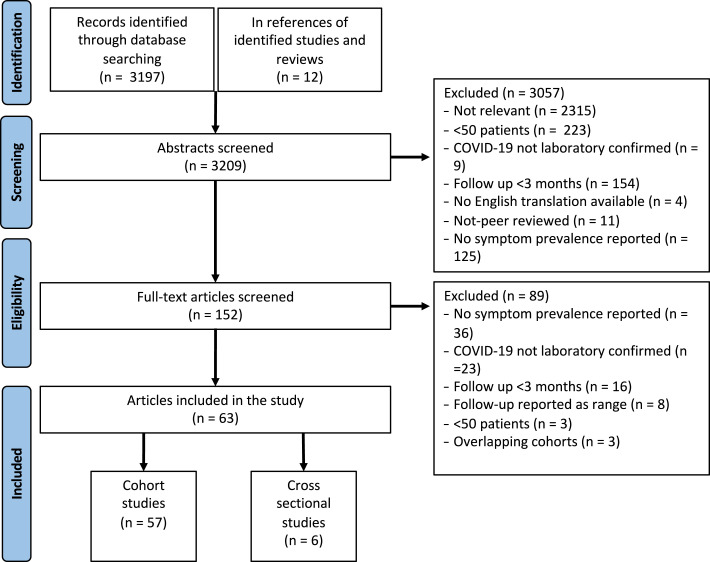

Of the 3209 abstracts screened, 152 full-text articles were reviewed, with 63 included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 ) [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]], [[50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79]]. After full article review, the most common reason for exclusion was absence of reported data on symptom prevalence at the stated follow-up (n = 36), followed by the inclusion of COVID-19 patients without laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 (n = 23). Of the 63 included studies (total COVID-19 population = 257 348), 6 were from North America (COVID-19 sample size = 237 261), 12 from East Asia (COVID-19 sample size = 10 162), 37 from Europe (COVID-19 sample size = 8998), and 8 from North Africa, the Middle East, or South Asia (COVID-19 sample size = 927) (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Summary of all included studies in descending order by sample size

| Study | Study design | Location | Sample size | Day zero | Follow-up (d) | Assessment method | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taquet et al. [26] | Nationwide | USA | 236 379 | Diagnosis date | 180 | EMR | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Mei et al. [51] | Multicentre | China | 3677 | Hospital discharge | 144 | In person | IP |

| César Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. [21] | Multicentre | Spain | 1950 | Hospital discharge | 340 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Chaolin Huang et al. [45] | Single centre | China | 1733 | Hospital discharge | 186 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Huang et al. [24] | Single centre | China | 1276 | Symptom onset | 185, 349 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. [46] | Multicentre | Spain | 1142 | Hospital discharge | 213 | Telephone, EMR | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Kim et al. [42] | Single centre | South Korea | 822 | Symptom onset or diagnosis date | 195 | Online | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Shang et al. [31] | Multicentre | China | 796 | Hospital discharge | 180 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Søraas et al. [62] | Multicentre | Norway | 676 | Diagnosis date | 132 | Online | OP |

| Qin et al. [49] | Single centre | China | 647 | Hospital discharge | 90 | In person | IP |

| Maestre-Muñiz et al. [20] | Single centre | Spain | 543 | Hospital discharge | 365 | In person | Mixed OP/IP |

| Qu et al. [54] | Multicentre | China | 540 | Hospital discharge | 90 | Telephone, online | IP |

| Knut Stavem et al. [55] | Multicentre | Norway | 458 | Symptom onset | 117.5 | Online, postal/mail | OP |

| Menges et al. [27] | Nationwide | Switzerland | 431 | Diagnosis date | 220 | Online | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Shoucri et al. [28] | Single centre | USA | 364 | Diagnosis date | 158 | In person, telephone | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Zayet et al. [18] | Single centre | France | 354 | Diagnosis date | 289.1 | Telephone, online | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Augustin et al. [36] | Single centre | Germany | 353 | Symptom onset | 207 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Yin et al. [34] | Single centre | China | 337 | Symptom onset | 203.4 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Sigfrid et al. [33] | Multicentre | United Kingdom | 327 | Hospital discharge | 222 | Telephone, in person, postal | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Boscolo-Rizzo et al. [23] | Multicentre | Italy | 304 | Symptom onset | 365 | Telephone | OP |

| DM Lombrado et al. [22] | Single centre | Italy | 303 | Diagnosis date | 371 | Telephone, EMR | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Sathyamurthy P et al. [68] | Single centre | India | 279 | Hospital discharge | 90 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Blomberg et al. [32] | Single centre | Norway | 247 | Diagnosis date | 180 | In person | OP |

| Clavario et al. [25] | Single centre | Italy | 200 | Hospital discharge | 180 | In person | IP |

| Darcis et al. [35] | Single centre | Belgium | 199 | Hospital discharge | 94, 180 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Riestra-Ayora et al. [37] | Single centre | Spain | 195 | Diagnosis date | 180 | Telephone | Mixed OP/IP |

| Jennifer A. Frontera et al. [41] | Multicentre | USA | 192 | Symptom onset | 201 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Pablo Parente-Arias et al. [58] | Multicentre | Spain | 151 | Symptom onset | 100.5 | Telephone, EMR | Mixed OP/IP |

| Han et al. [43] | Multicentre | China | 144 | Symptom onset | 180 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Sonnweber et al. [78] | Multicentre | Austria | 135 | Symptom onset | 103 | In person | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Froidure et al. [52] | Single centre | Belgium | 134 | Hospital discharge | 95 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Suárez-Robles et al. [60] | Single centre | Spain | 134 | Hospital discharge | 90 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| González-Hermosillo et al. [64] | Single centre | Mexico | 130 | Hospital discharge | 90, 180 | Telephone | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Nguyen et al. [47] | Single centre | France | 125 | Symptom onset | 221.7 | Telephone | IP |

| Garrigues et al. [74] | Single centre | France | 120 | Hospital admission | 110.9 | Telephone | IP/ICU∗ |

| Mattioli et al. [59] | Single centre | Italy | 120 | Diagnosis date | 126 | In person | Mixed OP/IP |

| Tawfik et al. [79] | Multicentre | Egypt | 120 | Diagnosis date | 120 | In person | Mixed OP/IP |

| Leila Simani et al. [40] | Single centre | Iran | 120 | Hospital discharge | 180 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Jacobson et al. [61] | Single centre | USA | 118 | Diagnosis date | 119.3 | In person | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Caruso et al. [39] | Single centre | Italy | 118 | Initial CT chest | 180 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Motiejunaite et al. [69] | Single centre | France | 114 | Diagnosis date | 90 | In person | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Schandl et al. [50] | Single centre | Sweden | 113 | ICU discharge | 152 | In person | ICU |

| Aranda et al. [38] | Single centre | Spain | 113 | Diagnosis date | 240 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Mechi et al. [19] | Single centre | Iraq | 112 | Diagnosis date | 274 | In person | OP |

| Skala et al. [65] | Multicentre | Czech Republic | 102 | Diagnosis date | 90 | In person | Mixed OP/IP |

| T. J. M. Wallis et al. [67] | Single centre | United Kingdom | 101 | Hospital admission | 96 | Telephone, in person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Lindahl et al. [48] | Single centre | Finland | 101 | Hospital discharge | 180 | Online | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Biadsee et al. [29] | Single centre | Israel | 97 | Diagnosis date | 231 | Telephone | OP |

| Seeßle et al. [66] | Single centre | Germany | 96 | Symptom onset | 152, 365 | In person | Mixed OP/IP |

| Boari et al. [72] | Single centre | Italy | 91 | Hospital discharge | 120 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Taboada et al. [44] | Multicentre | Spain | 91 | ICU discharge | 180 | In person | ICU |

| Mumoli et al. [57] | Single centre | Italy | 88 | Hospital admission | 91 | In person | IP |

| Parry et al. [56] | Single centre | India | 81 | Initial CT chest | 100.6 | EMR | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Wong et al. [73] | Multicentre | Canada | 78 | Symptom onset | 91 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Dieter Munker et al. [70] | Multicentre | Germany | 76 | Diagnosis date | 120 | In person | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

| Liang et al. [71] | Single centre | China | 76 | Hospital discharge | 90 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Noel-Savina et al. [63] | Single centre | France | 72 | Diagnosis date | 129 | In person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Elkan et al. [17] | Single centre | Israel | 66 | Hospital discharge | 270 | Online, telephone | IP |

| Jessica González et al. [53] | Single centre | Spain | 62 | Hospital discharge | 90 | In person, EMR | ICU |

| Yiping Lu et al. [75] | Single centre | China | 60 | Symptom onset | 90 | In-person | Mixed IP/ICU |

| Fortini et al. [77] | Single centre | Italy | 59 | Hospital discharge | 123 | In-person, telephone | IP |

| Wu et al. [30] | Single centre | China | 54 | Hospital discharge | 180 | In person | IP |

| Seyed Mohammad Hossein Tabatabaei et al. [76] | Single centre | Iran | 52 | Initial CT chest | 91 | EMR | Mixed IP/OP/ICU |

IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; ICU, intensive care unit; EMR, electronic medical records.

ICU and IP results presented separately.

The majority of included studies were single centre (n = 43), followed by multicentre (n = 18), with two nationwide studies. Only 4 studies included follow-up of ≥365 days (sample size = 1246), with 5 studies with follow-up of 270 to 364 days (sample size = 3758), 25 studies with follow-up of 180 to 269 days (sample size = 243 576), and the majority of studies with follow-up of 90 to 179 days (n = 33, sample size = 9323).

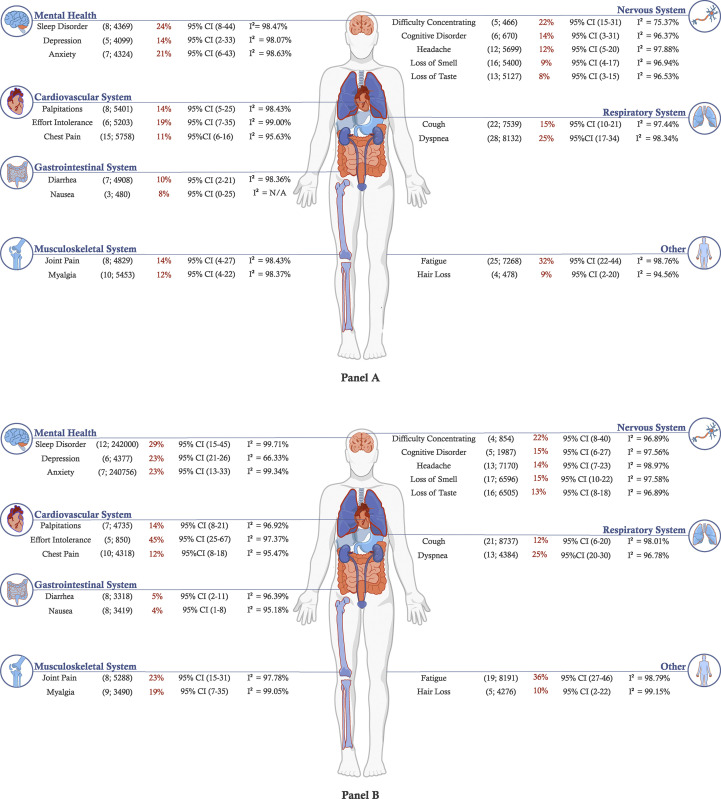

Meta-analyses of prevalence of symptoms at different follow-up periods

Meta-analysis highlighted the substantial heterogeneity in symptom prevalence reported across studies, with I2 statistics ranging from 75.4% (difficulty concentrating at 3- to <6-month follow-up) to 99.4% (fatigue at 9- to <12-month follow-up), with the vast majority of symptoms across all follow-up intervals producing an I2 ≥ 90%. The most commonly reported symptoms between 3 and < 6 months are fatigue (32%, 95% CI = 22%–44%, number of studies = 25, sample size = 7268), dyspnoea (25%, 95% CI = 17%–34%, number of studies = 28, sample size = 8132), sleep disorder (24%, 95% CI = 8%–44%, number of studies = 8, sample size = 4369), and concentration difficulty (22%, 95% CI = 15%–31%, number of studies = 5, sample size = 466).

At 6 to <9 months, the most common symptoms reported were effort intolerance (45%, 95% CI = 25%–67%, number of studies = 5, sample size = 850), fatigue (36%, 95% CI = 27%–46%, number of studies = 19, sample size 8191), sleep disorder (29%, 95% CI 15%–45%, number of studies = 12, sample size = 242 000), and dyspnoea (25%, 95% CI = 20%–30%, number of studies = 134 384).

In the 9- to <12-month period, the meta-analysis included nine symptoms, with the highest prevalence reported for fatigue (37%, 95% CI = 16%–62%, number of studies = 5, sample size = 3758) and dyspnoea (21%, 95% CI = 14%–28%, number of studies = 5, sample size = 3758), with loss of taste being the least reported (6%, 95% CI: 1%–13%, number of studies = 3, sample size = 1742). Similarly, fatigue was the most reported symptom (41%, 95% CI: 30%–53%, number of studies = 4, sample size = 1246) in the >12-month period. It is noteworthy that fatigue, dyspnoea, myalgia, and sleep disorder were most reported in the >12-month interval, while cough, headache, loss of taste, and loss of smell were most common at 6 to <9 months (Figs. 2 A, B; Supplement 6, Panels C, D).

Fig. 2.

Illustration of meta-analysis results with estimated prevalence of symptoms following acute COVID-19 infection across follow-up intervals of (A) 3 to <6 months and (B) 6 to <9 months (number of studies, size of population used to calculate point estimate).

Exploring heterogeneity

Due to a limited number of studies reporting symptom prevalence at 9 to <12 months or ≥12 months, meta-regression was performed for symptom prevalence at 3 to <6 months and 6 to <9 months (Supplement 6). Observed statistically significant effect modifiers included world region where the study was conducted; percentage of study participants who were male and those who had DM; disease severity categorym as defined earlier; and the overall study quality score.

Studies reporting results from Asian populations reported a lower prevalence of fatigue, dyspnoea, loss of smell, and loss of taste at 3–6-month follow-up and a lower prevalence of fatigue at 6–9-month follow-up. A higher proportion of male patients was found to be associated with a lower prevalence of cough and loss of smell at 6–9 months, whilst a higher proportion of diabetes mellitus as a comorbidity was associated with a lower prevalence of loss of smell and taste at 3–6 and 6–9 months. Studies investigating patients in ICUs were associated with a higher prevalence of dyspnoea compared to studies investigating an OP population at 3–6-month and 6–9-month follow-up intervals. Higher study quality was found to be associated with lower prevalence of dyspnoea at 3–6 months and cough at 6–9 months.

Studies with a COVID-19–negative comparator group

A total of six studies reporting symptom prevalence included a comparator group consisting of COVID-19–negative cases, with a summary of their findings presented in Table 2 [17,24,26,37,59,62]. Of these, two studies compared long-term symptom prevalence of COVID-19 cases to either influenza, pneumonia, or other respiratory tract infection cases [17,26]. Overall, all but one study reported a higher prevalence of symptoms or adverse events in cases after COVID-19 compared to respective comparator groups, with one negative study specifically assessing olfactory and gustatory dysfunction at 6 months [37]. Two of six studies were rigorously designed. One study observed that COVID-19 cases had a significantly higher hazard of mood disorder, anxiety, and insomnia when compared to matched cohorts with influenza or respiratory tract infection [26]. Another study observed that COVID-19 cases have a significantly higher prevalence of symptoms at 6- and 9-month follow-up when compared to community controls, including fatigue, sleep difficulties, hair loss, smell disorder, taste disorder, palpitations, chest pain, and headaches [45].

Table 2.

Summary of studies reporting long COVID-19 symptom prevalence with a comparator group

| Authors | Study design (average follow up in d) | COVID-19 group definition | Comparator group definition | Symptom/outcome assessment method | Newcastle-Ottawa scale | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [24] | Ambidirectional cohort (185 days and 349 days). | Patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 discharged from Jin Yin-tan Hospital (Wuhan, China) (n = 1164) | Community adults without COVID-19 from two districts of Wuhan city, matched with cases 1:1 by age, sex and comorbiditiesa (n = 1164) | Interview, physical examination, questionnaires | 7/9 | COVID-19 patients had significantly higher prevalence of any of the following symptoms and for each individual symptom: fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, hair loss, smell disorder, palpitations, joint pain, decreased appetite, taste disorder, dizziness, diarrhoea or vomiting, chest pain, sore throat or difficulty swallowing, skin rash, myalgia, headache, cough. COVID-19 patients had significantly higher mMRC dyspnoea scores and reported significantly more difficulty with mobility, personal care, pain or discomfort, anxiety or depression and overall quality of life. |

| Taquet et al. [26] | Retrospective cohort (180 d) | Patients with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, aged ≥10 y and alive at time of analysis; data collected using the TriNetX Analytics Network, consisting of anonymized data from 81 million patients, primarily in the USA (matched with influenza cases n = 105 579, matched with other RTI n = 236 038) | Propensity-matched patients from the same database, with COVID-19 cases matched separately with influenza or RTI, including influenza; matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity and co-morbiditiesb (influenza n = 105 579, RTI n = 236 038) | ICD-10 codes, EMR | 9/9 | COVID-19 had significantly higher hazard compared to both the matched influenza cohort and RTI cohort for mood disorder, anxiety disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, and insomnia |

| Riestra-Ayora et al. [37] | Prospective cohort† (180 d) | Health workers from a tertiary care hospital with suspected and symptomatic COVID-19, confirmed by PCR (n = 195) | Health workers from a tertiary care hospital with suspected COVID-19 with negative PCR, matched for sex and age (n = 125) | Interview | 5/9 | There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of recovery from olfactory dysfunction between those with positive PCR for COVID-19 and those with suspected COVID-19 with negative PCR |

| Mattioli et al. [59] | Prospective cohort (126 d) | Healthcare workers at University Hospital of Brescia (Italy) with previous confirmed diagnosis of mild-moderate COVID-19 (n = 120) | Healthcare workers from the same hospital not previously affected by COVID-19 (n = 30) | Interview, physical examination, questionnaires | 5/9 | COVID-19 cases did not differ significantly from non–COVID-19 controls in terms of neurological or cognitive deficits but had significantly higher scores for anxiety and depression |

| Elkan et al. [17] | Retrospective cohortc (270 d) | Adult patients discharged from Shamir Medical Center (Israel) with confirmed COVID-19 (n = 42) | Age- and sex-matched patients hospitalized during the same period as COVID-19 patients due to pneumonia or respiratory infection with negative COVID-19 PCR (n = 42) | Questionnaire | 6/9 | Although there are baseline differences between groups in terms of comorbidities, COVID-19 cases had significantly lower self-reported ‘health change’ compared to controls |

| Søraas et al. [62] | Prospective cohort (132 d) | Adults testing positive for COVID-19 across four laboratories in southeastern Norway, excluding participants later hospitalized (n = 676) | Adults testing negative for COVID-19 across the same sites, excluding participants later hospitalized (n = 6006) | Questionnaire | 9/9 | COVID-19–positive participants were significantly more likely to report a worsening of health compared to 1 y prior to follow-up when compared to COVID-19–negative participantsd |

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; RTI, respiratory tract infection.

Cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

Obesity, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, asthma, chronic lower respiratory diseases, nicotine dependence, substance use disorder, ischaemic heart disease and other forms of heart disease, socioeconomic deprivation, cancer, haematological cancer, chronic liver disease, stroke, dementia, organ transplant, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, psoriasis, and disorders involving an immune mechanism.

Study design was derived from manuscript method section and not author description.

Multivariate regression model including age, sex, chronic diseases, smoking, health professional occupation, income level, fitness, and time from COVID-19 testing to follow-up.

Quality assessment

Studies without comparator groups

The studies were generally assessed to have good quality, with a mean average critical appraisal score across all studies of 7.97 of 9. The question that affected the scores the most was ‘Was the sample size adequate?’; few studies demonstrated appropriate sample size calculations or represented a large enough sample to provide high external validity (Table S1).

Studies with comparator groups

Study quality was assessed via the NOS as moderate to high, ranging from 5 to 9 (maximum 9), with a number of studies using a nonrepresentative sample of healthcare workers [37,59] or having comparability concerns by not adequately matching cases with the comparator group [17,37,59,62] (Table S2).

Discussion

Summary of the findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 63 studies with a total of 257 348 COVID-19 patients from different world regions, we observed that patients report several clinically significant symptoms across many organs systems 3 months after acute COVID-19. In addition, we observed that the high between-study heterogeneity of reported symptom prevalence could be at least partially explained by clinically plausible effect modifiers such as acute COVID-19 severity and certain patients' demographics and comorbidities [26,45,80,81].

Our findings lend more support to the initiatives of several countries and organizations that have started to fund more research and disseminate guidelines to better understand, diagnose, and treat PACS [8,82,83].

Mechanisms

It remains unknown what proportion of these lingering symptoms are true sequalae of COVID-19 vs. the effects of underlying chronic diseases or pandemic effects on individuals and societies [84,85]. Although most studies did not have a control group, the association of certain symptoms with COVID-19 infection among the six studies that had appropriate comparator groups supports our findings of a significant burden of PACS. Recent rigorously conducted comparative studies that examined the risk of new clinical sequalae rather than persistent symptoms at 6-month follow-up have shown a higher risk of long-term complications and incident diagnoses after acute COVID-19 infection among nonhospitalized cases when compared to a matched non–COVID-19 cohort and among hospitalized COVID-19 cases when compared to matched hospitalized influenza cases or other non–COVID-19 viral lower respiratory tract illnesses. An increasing risk gradient of new sequalae was observed with increasing COVID-19 severity [86,87].

Nevertheless, the mechanisms that explain these chronic symptoms after COVID-19 are not yet fully understood. In addition to the direct effects of SARS-CoV-2, the immune response to the virus is believed to be partly responsible for the appearance of these lasting symptoms, possibly through facilitating an ongoing hyperinflammatory process [88]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the long-term outcomes of COVID-19 infection: (a) sequalae of COVID-19 organ involvement during acute infection; (b) COVID-19 patients with chronic symptoms may harbour the virus in several potential tissue reservoirs across the body, which may not be identified by nasopharyngeal swabs; (c) cross-reactivity of SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies with host proteins resulting in autoimmunity; (d) delayed viral clearance due to immune exhaustion resulting in chronic inflammation and impaired tissue repair; (e) mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired immunometabolism; and (f) alterations in microbiome leading to long-term health consequences of COVID-19 [[88], [89], [90], [91]].

Comparison to other studies

Our systematic review provides a rigorous and unique update of previous attempts by other investigators. First, a number of previous reviews either did not assess the included studies for risk of bias or used an inappropriate assessment tool, such as the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for noncomparative studies. We observed the quality of included studies to be a significant contributor to heterogeneity of reported symptoms prevalence, with lower-quality studies reporting higher prevalence of certain symptoms [92,93]. Second, other systematic reviews have included studies with short follow-up periods between 1 and 3 months after acute illness and hence do not provide an indication of persistent and chronic symptoms that are defined beyond 12 weeks as per NICE [[92], [93], [94], [95]]. Third, although previous studies have performed meta-analyses, with Michelen et al. performing meta-regression for variables of ICU admission and proportion of female patients and Iqbal et al. performing thorough subgroup analysis, no previous systematic review has separated symptom prevalence across different follow-up intervals or considered other important effect modifiers for meta-regression [96,97]. Finally, and importantly, we present the first attempt to identify and assess studies including an appropriate non–COVID-19 group to provide additional evidence on the association between COVID-19 and the high prevalence of symptoms at follow-up.

Although our review included the most recent eligible studies with the largest sample size, there is a degree of consistency between the findings of symptom prevalence in our meta-analyses and others. We report a prevalence of fatigue of 32%, 36%, 47%, and 41% across follow-up periods from 3 to <6 months, 6 to <9 months, 9 to <12 months, and >12 months respectively, which is comparable to the findings of Michelen et al. [96] (30.1%) and Iqbal et al. [97] (37%). This similarity is also the case for dyspnoea, with previous meta-analysis reporting estimates of prevalence between 25% and 35%, as well as myalgia and hair loss.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is the largest and most comprehensive systematic review of persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 to date. However, it has a number of limitations inherent to the included studies and study design. As noted by previous systematic reviews on this topic, studies included in our review lacked uniform symptom terminology, standardized recording methods, and grouping of multiple symptoms under umbrella terms. This limited our ability to compare prevalence and frequency of these symptoms across the studies. Severity of illness was not described in numerous studies, with results presented for whole cohorts and not presented as subgroups. Thus, grouping all symptoms of various disease severity yield inaccurate estimates of symptom frequencies. The high observed statistical heterogeneity as measured by I2 limits the interpretation of the pooled frequencies, although our extensive meta-regression illuminates significant contributors to this heterogeneity, namely, severity as defined by highest level of medical care, geographic location, prevalence of diabetes, and method of assessing symptom at follow-up [98].

We agree with Nasserie et al. [94] in their recommendations about areas of improvement in future research of PACS, whether in the conduct of studies or reporting of the various characteristics of symptoms for such conditions, including the use of a standardized definition for symptoms and time-zero and including an objective measure of symptom severity and duration. There is a need for further rigorously conducted cohort studies to quantify the relative risk of developing long-term symptoms after acute COVID-19 infection in comparison to a non–COVID-19 comparator group, including healthy controls and those with other acute respiratory infections [94,97,99].

Conclusion

In this large systematic review, we observed, with high degree of between-study heterogeneity, that a large proportion of COVID-19 patients have persisting and varying symptoms for several months after the acute infection. Although many unanswered questions about PACS remain, our study brings more evidence from a large number of patients and across different worldwide populations on the prevalence of the long-term effects of COVID-19. Our data support the recent global efforts to conduct additional research to address the underlying mechanisms, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of PACS.

Transparency declaration

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. EFB receives a UTD honorarium <5 k per year and is a member of the advisory board for Debiopharm International S.A. No funding was received for this work.

Author contribution

MSA and OAO contributed equally as first authors. NAF, BAS, RA, and MR contributed equally as second authors. Conceptualization: IMT and TK; supervision: IMT and KMT; project administration: MSA and OAO; formal analysis: MR; data curation: BAS, DG, MSA, MO, NAF, OAO, RA, YO, and ZK; visualization: MR, and RMT; writing—original draft: BAS, MSA, NAF, OAO, and RA; writing—review and editing: EFB and IMT.

Editor: M. Paul

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sandler C.X., Wyller V.B.B., Moss-Morris R., Buchwald D., Crawley E., Hautvast J., et al. Long COVID and post-infective fatigue syndrome: a review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab440. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nalbandian A., Sehgal K., Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., McGroder C., Stevens J.S., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2021. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 [cited 2021 Dec 19]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) 2020. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 [cited 2021 Dec 19]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lledó G.M., Sellares J., Brotons C., Sans M., Antón J.D., Blanco J., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: a new tsunami requiring a universal case definition. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Sys Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivan M., Taylor S. NICE guideline on long covid. BMJ. 2020;371:m4938. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munn Z., Moola S., Lisy K., Riitano D., Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt G., Busse J. Methods commentary: risk of bias in cohort studies. https://www.evidencepartners.com/resources/methodological-resources/risk-of-bias-in-cohort-studies [cited 2021 Dec 18]. Available from:

- 11.Tleyjeh I.M., Kashour Z., AlDosary O., Riaz M., Tlayjeh H., Garbati M.A., et al. Cardiac toxicity of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. MCP:IQ&O. 2021;5:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barendregt J.J., Doi S.A., Lee Y.Y., Norman R.E., Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:974. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeks J., Higgins J.P., Altman D.G. Chapter 10: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10 [cited 2021 Dec 18]. Available from:

- 16.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkan M., Dvir A., Zaidenstein R., Keller M., Kagansky D., Hochman C., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures after hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey among COVID-19 and Non-COVID-19 patients. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:4829–4836. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S323316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zayet S., Zahra H., Royer P.-Y., Tipirdamaz C., Mercier J., Gendrin V., et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: nine months after SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of 354 patients: data from the first wave of COVID-19 in Nord Franche-Comté Hospital, France. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1719. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9081719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mechi A., Al-Khalidi A., Al-Darraji R., Al-Dujaili M.N., Al-Buthabhak K., Alareedh M., et al. Long-term persistent symptoms of COVID-19 infection in patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s13410-021-00994-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maestre-Muñiz M.M., Arias Á., Mata-Vázquez E., Martín-Toledano M., López-Larramona G., Ruiz-Chicote A.M., et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 at one year after hospital discharge. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2945. doi: 10.3390/jcm10132945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C., Guijarro C., Plaza-Canteli S., Hernández-Barrera V., Torres-Macho J. Prevalence of post-COVID-19 cough one year after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter study. Lung. 2021;199:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00450-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lombardo M.D.M., Foppiani A., Peretti G.M., Mangiavini L., Battezzati A., Bertoli S., et al. Long-term coronavirus disease 2019 complications in inpatients and outpatients: a one-year follow-up cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab384. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boscolo-Rizzo P., Guida F., Polesel J., Marcuzzo A.V., Capriotti V., D’Alessandro A., et al. Sequelae in adults at 12 months after mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11:1685–1688. doi: 10.1002/alr.22832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L., Yao Q., Gu X., Wang Q., Ren L., Wang Y., et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clavario P., de Marzo V., Lotti R., Barbara C., Porcile A., Russo C., et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in COVID-19 patients at 3 months follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2021;340:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menges D., Ballouz T., Anagnostopoulos A., Aschmann H.E., Domenghino A., Fehr J.S., et al. Burden of post-COVID-19 syndrome and implications for healthcare service planning: a population-based cohort study. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoucri S.M., Purpura L., DeLaurentis C., Adan M.A., Theodore D.A., Irace A.L., et al. Characterising the long-term clinical outcomes of 1190 hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in New York City: a retrospective case series. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biadsee A., Dagan O., Ormianer Z., Kassem F., Masarwa S., Biadsee A. Eight-month follow-up of olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions in recovered COVID-19 patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:103065. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Q., Zhong L., Li H., Guo J., Li Y., Hou X., et al. A follow-up study of lung function and chest computed tomography at 6 months after discharge in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Can Respir J. 2021;2021:6692409. doi: 10.1155/2021/6692409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shang Y.F., Liu T., Yu J.N., Xu X.R., Zahid K.R., Wei Y.C., et al. Half-year follow-up of patients recovering from severe COVID-19: analysis of symptoms and their risk factors. J Intern Med. 2021;290:444–450. doi: 10.1111/joim.13284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blomberg B., Mohn K.G.-I., Brokstad K.A., Zhou F., Linchausen D.W., Hansen B.-A., et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021;27:1607–1613. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigfrid L., Drake T.M., Pauley E., Jesudason E.C., Olliaro P., Lim W.S., et al. Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid-19: a prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Regional Health Europe. 2021;8:100186. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin X., Xi X., Min X., Feng Z., Li B., Cai W., et al. Long-term chest CT follow-up in COVID-19 Survivors: 102–361 days after onset. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:1231. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darcis G., Bouquegneau A., Maes N., Thys M., Henket M., Labye F., et al. Long-term clinical follow-up of patients suffering from moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection: a monocentric prospective observational cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;109:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Augustin M., Schommers P., Stecher M., Dewald F., Gieselmann L., Gruell H., et al. Post-COVID syndrome in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Lancet Regional Health Europe. 2021;6:100122. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riestra-Ayora J., Yanes-Diaz J., Esteban-Sanchez J., Vaduva C., Molina-Quiros C., Larran-Jimenez A., et al. Long-term follow-up of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19: 6 months case-control study of health workers. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021;278:4831–4837. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-06764-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aranda J., Oriol I., Martín M., Feria L., Vázquez N., Rhyman N., et al. Long-term impact of COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Infect. 2021;83:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caruso D., Guido G., Zerunian M., Polidori T., Lucertini E., Pucciarelli F., et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 pneumonia: six-month chest CT follow-up. Radiology. 2021;301:E396–E405. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simani L., Ramezani M., Darazam I.A., Sagharichi M., Aalipour M.A., Ghorbani F., et al. Prevalence and correlates of chronic fatigue syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder after the outbreak of the COVID-19. J Neurovirol. 2021;27:154–159. doi: 10.1007/s13365-021-00949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frontera J.A., Yang D., Lewis A., Patel P., Medicherla C., Arena V., et al. A prospective study of long-term outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without neurological complications. J Neurol Sci. 2021;426:117486. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y., Kim S.-W., Chang H.-H., Kwon K.T., Bae S., Hwang S. Significance and associated factors of long-term sequelae in patients after acute COVID-19 infection in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:463–476. doi: 10.3947/ic.2021.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han X., Fan Y., Alwalid O., Li N., Jia X., Yuan M., et al. Six-month follow-up chest CT findings after severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiology. 2021;299:E177–E186. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taboada M., Moreno E., Cariñena A., Rey T., Pita-Romero R., Leal S., et al. Quality of life, functional status, and persistent symptoms after intensive care of COVID-19 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:e110–e113. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C., Palacios-Ceña D., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Rodríuez-Jiménez J., Palacios-Ceña M., Velasco-Arribas M., et al. Long-term post-COVID symptoms and associated risk factors in previously hospitalized patients: a multicenter study. J Infect. 2021;83:237–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen N.N., Hoang V.T., Lagier J.-C., Raoult D., Gautret P. Long-term persistence of olfactory and gustatory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:931–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindahl A., Aro M., Reijula J., Mäkelä M.J., Ollgren J., Puolanne M., et al. Women report more symptoms and impaired quality of life: a survey of Finnish COVID-19 survivors. Infect Dis. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1965210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin W., Chen S., Zhang Y., Dong F., Zhang Z., Hu B., et al. Diffusion capacity abnormalities for carbon monoxide in patients with COVID-19 at 3-month follow-up. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:2003677. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03677-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schandl A., Hedman A., Lyngå P., Fathi Tachinabad S., Svefors J., Roël M., et al. Long-term consequences in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a prospective cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65:1285–1292. doi: 10.1111/aas.13939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mei Q., Wang F., Yang Y., Hu G., Guo S., Zhang Q., et al. Health issues and immunological assessment related to Wuhan’s COVID-19 survivors: a multicenter follow-up study. Front Med. 2021;8:617689. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.617689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Froidure A., Mahsouli A., Liistro G., de Greef J., Belkhir L., Gérard L., et al. Integrative respiratory follow-up of severe COVID-19 reveals common functional and lung imaging sequelae. Respir Med. 2021;181:106383. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.González J., Benítez I.D., Carmona P., Santisteve S., Monge A., Moncusí-Moix A., et al. Pulmonary function and radiologic features in survivors of critical COVID-19: a 3-month prospective cohort. Chest. 2021;160:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qu G., Zhen Q., Wang W., Fan S., Wu Q., Zhang C., et al. Health-related quality of life of COVID-19 patients after discharge: a multicenter follow-up study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:1742–1750. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stavem K., Ghanima W., Olsen M.K., Gilboe H.M., Einvik G. Prevalence and determinants of fatigue after COVID-19 in non-hospitalized subjects: a population-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2030. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parry A.H., Wani A.H., Shah N.N., Jehangir M. Medium-term chest computed tomography (CT) follow-up of COVID-19 pneumonia patients after recovery to assess the rate of resolution and determine the potential predictors of persistent lung changes. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Me. 2021;52:55. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mumoli N., Bonaventura A., Colombo A., Vecchié A., Cei M., Vitale J., et al. Lung function and symptoms in post-COVID-19 patients: a single-center experience. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcome. 2021;5:907–915. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parente-Arias P., Barreira-Fernandez P., Quintana-Sanjuas A., Patiño-Castiñeira B. Recovery rate and factors associated with smell and taste disruption in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:102648. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mattioli F., Stampatori C., Righetti F., Sala E., Tomasi C., de Palma G. Neurological and cognitive sequelae of Covid-19: a four month follow-up. J Neurol. 2021;268:4422–4428. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10579-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suárez-Robles M., Iguaran-Bermúdez M.D.R., García-Klepizg J.L., Lorenzo-Villalba N., Méndez-Bailón M. Ninety days post-hospitalization evaluation of residual COVID-19 symptoms through a phone call check list. Pan Afr Med. 2020;37:289. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.289.27110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacobson K.B., Rao M., Bonilla H., Subramanian A., Hack I., Madrigal M., et al. Patients with uncomplicated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have long-term persistent symptoms and functional impairment similar to patients with severe COVID-19: a cautionary tale during a global pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e826–e829. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Søraas A., Kalleberg K.T., Dahl J.A., Søraas C.L., Myklebust T.Å., Axelsen E., et al. Persisting symptoms three to eight months after non-hospitalized COVID-19, a prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noel-Savina E., Viatgé T., Faviez G., Lepage B., Mhanna L.T., Pontier S., et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: clinical, functional and imaging outcomes at 4 months. Respir Med Res. 2021;80:100822. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2021.100822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.González-Hermosillo J.A., Martínez-López J.P., Carrillo-Lampón S.A., Ruiz-Ojeda D., Herrera-Ramírez S., Amezcua-Guerra L.M., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 symptoms, a potential link with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a 6-month survey in a Mexican cohort. Brain Sci. 2021;11:760. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11060760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skala M., Svoboda M., Kopecky M., Kocova E., Hyrsl M., Homolac M., et al. Heterogeneity of post-COVID impairment: interim analysis of a prospective study from Czechia. Virol J. 2021;18:73. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seeßle J., Waterboer T., Hippchen T., Simon J., Kirchner M., Lim A., et al. Persistent symptoms in adult patients one year after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab611. ciab611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallis T.J.M., Heiden E., Horno J., Welham B., Burke H., Freeman A., et al. Risk factors for persistent abnormality on chest radiographs at 12-weeks post hospitalisation with PCR confirmed COVID-19. Respir Res. 2021;22:157. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01750-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sathyamurthy P., Madhavan S., Pandurangan V. Prevalence, pattern and functional outcome of post COVID-19 syndrome in older adults. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Motiejunaite J., Balagny P., Arnoult F., Mangin L., Bancal C., Vidal-Petiot E., et al. Hyperventilation as one of the mechanisms of persistent dyspnoea in SARS-CoV-2 survivors. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:2101578. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01578-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Munker D., Veit T., Barton J., Mertsch P., Mümmler C., Osterman A., et al. Pulmonary function impairment of asymptomatic and persistently symptomatic patients 4 months after COVID-19 according to disease severity. Infection. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01669-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liang L., Yang B., Jiang N., Fu W., He X., Zhou Y., et al. Three-month follow-up study of survivors of coronavirus disease 2019 after discharge. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e418. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boari G.E.M., Bonetti S., Braglia-Orlandini F., Chiarini G., Faustini C., Bianco G., et al. Short-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2-related pneumonia: a follow up study. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2021;28:373–381. doi: 10.1007/s40292-021-00454-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong A.W., Shah A.S., Johnston J.C., Carlsten C., Ryerson C.J. Patient-reported outcome measures after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2003276. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03276-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garrigues E., Janvier P., Kherabi Y., le Bot A., Hamon A., Gouze H., et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e4–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu Y., Li X., Geng D., Mei N., Wu P.-Y., Huang C.-C., et al. Cerebral micro-structural changes in COVID-19 patients - an MRI-based 3-month follow-up study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100484. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tabatabaei S.M.H., Rajebi H., Moghaddas F., Ghasemiadl M., Talari H. Chest CT in COVID-19 pneumonia: what are the findings in mid-term follow-up? Emerg Radiol. 2020;27:711–719. doi: 10.1007/s10140-020-01869-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fortini A., Torrigiani A., Sbaragli S., lo Forte A., Crociani A., Cecchini P., et al. COVID-19: persistence of symptoms and lung alterations after 3-6 months from hospital discharge. Infection. 2021;49:1007–1015. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01638-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sonnweber T., Sahanic S., Pizzini A., Luger A., Schwabl C., Sonnweber B., et al. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19: an observational prospective multicentre trial. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2003481. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03481-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tawfik H.M., Shaaban H.M., Tawfik A.M. Post-covid-19 syndrome in egyptian healthcare staff: highlighting the carers sufferings. Electron J Gen Med. 2021;18 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tleyjeh I.M., Saddik B., AlSwaidan N., AlAnazi A., Ramakrishnan R.K., Alhazmi D., et al. Prevalence and predictors of Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS) after hospital discharge: a cohort study with 4 months median follow-up. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stewart S., Newson L., Briggs T.A., Grammatopoulos D., Young L., Gill P. Long COVID risk - a signal to address sex hormones and women’s health. Lancet Regional Health Europe. 2021;11:100242. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lerner A.M., Robinson D.A., Yang L., Williams C.F., Newman L.M., Breen J.J., et al. Toward understanding COVID-19 recovery: National Institutes of Health workshop on postacute COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:999–1003. doi: 10.7326/M21-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rajan S., Khunti K., Alwan N., Steves C., Greenhalgh T., Macdermott N., et al. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; Copenhagen (Denmark): 2021. In the wake of the pandemic: Preparing for Long COVID [Internet]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK569598/ (Policy Brief, No. 39.) Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steinman M.A., Auerbach A.D. Managing chronic disease in hospitalized patients. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173:1857–1858. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fofana N.K., Latif F., Sarfraz S., Bilal, Bashir M.F., Komal B. Fear and agony of the pandemic leading to stress and mental illness: an emerging crisis in the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Psych Res. 2020;291:113230. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Aly Z., Xie Y., Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Daugherty S.E., Guo Y., Heath K., Dasmariñas M.C., Jubilo K.G., Samranvedhya J., et al. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Korompoki E., Gavriatopoulou M., Hicklen R.S., Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I., Kastritis E., Fotiou D., et al. Epidemiology and organ specific sequelae of post-acute COVID19: a narrative review. J Infect. 2021;83:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gavriatopoulou M., Korompoki E., Fotiou D., Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I., Psaltopoulou T., Kastritis E., et al. Organ-specific manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Clin Exp Med. 2020;20:493–506. doi: 10.1007/s10238-020-00648-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang T., Du Z., Zhu F., Cao Z., An Y., Gao Y., et al. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:e52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ramakrishnan R.K., Kashour T., Hamid Q., Halwani R., Tleyjeh I.M. Unraveling the mystery surrounding post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:686029. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.686029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayes L.D., Ingram J., Sculthorpe N.F. More than 100 persistent symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 (Long COVID): a scoping review. Front Med. 2021;8:2028. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.750378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Groff D., Sun A., Ssentongo A.E., Ba D.M., Parsons N., Poudel G.R., et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nasserie T., Hittle M., Goodman S.N. Assessment of the frequency and variety of persistent symptoms among patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lopez-Leon S., Wegman-Ostrosky T., Perelman C., Sepulveda R., Rebolledo P.A., Cuapio A., et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Michelen M., Manoharan L., Elkheir N., Cheng V., Dagens A., Hastie C., et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Iqbal F.M., Lam K., Sounderajah V., Clarke J.M., Ashrafian H., Darzi A. Characteristics and predictors of acute and chronic post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021:36. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Imrey P.B. Limitations of meta-analyses of studies with high heterogeneity. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1919325. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Amin-Chowdhury Z., Ladhani S.N. Causation or confounding: why controls are critical for characterizing long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:1129–1130. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01402-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.