Abstract

Background:

Therapy services can support developmental needs, improve social emotional outcomes, and reduce persistent health inequities for children with developmental disabilities (DD). Receipt of therapy services may be especially timely when children with DD are school-aged, once diagnosis has often occurred. Yet limited knowledge exists on geographic variability and determinants of therapy use among school-aged U.S. children with DD.

Objectives:

We aimed to (1) determine if therapy use varies significantly by state and (2) examine associations of health determinants with therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD.

Methods:

This was a secondary analysis of 2016 and 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health data. The sample included 9984 children with DD ages 6e17 years. We obtained odds ratios and predicted margins with 95% confidence intervals from multilevel logistic regression models to examine therapy use variation and determinants.

Results:

Overall, 34.6% of children used therapy services. Therapy use varied significantly across states (σ2 = 0.11, SE = 0.04). Younger age, public insurance, functional limitations, individualized education program, frustration accessing services, and care coordination need were associated with higher adjusted odds of therapy access. In states with Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services waivers, higher estimated annual waiver cost was associated with lower adjusted odds of therapy use.

Conclusions:

Results highlight geographic disparities in therapy use and multilevel targets to increase therapy use for school-aged children with DD.

Keywords: children, developmental disabilities, geographic variation, health determinants, therapy

Introduction

One in six U.S. children has a developmental disability.1 Developmental disabilities (DD) are chronic conditions due to mental and/or physical impairments, including conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).2 This heterogeneous group of conditions commonly affect children early in life, and without the necessary services and supports, may have more proximal effects on language and learning contributing to multiple impacts on behavior and independent living in the longer term. Children with DD often require more prescription medication, therapies, special education, and medical support than other children.3 Therapy services (e.g., behavioral therapy) are especially critical to helping improve functional skills for many children with DD. Therapy services are often accessed following diagnosis, which commonly does not occur until children with DD are school-aged.2 Still, knowledge is limited on state variation and determinants of therapy use among school-aged children with DD.

Child and family characteristics including poverty, insurance coverage, and race and ethnicity have been associated with therapy use among children with DD. For example, children in low income families are less likely to access early diagnosis services, which is critical to early therapy use.4 Not having health insurance is related to increased unmet therapy need for children with DD.5 Children with DD, particularly those with ASD, who identify as racial and ethnic minorities may also have poor access to therapy services.6,7 Healthcare access and quality (e.g., patient-centered medical home including effective care coordination) may further affect therapy use for children with DD, at times by way of programs such as early intervention.8,9

State context including policies, such as the Medicaid 1915(c) Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waivers, have been used to transform services for individuals with DD. Under the Social Security Act section 1915 (c), 23 states and the District of Columbia adopted Medicaid HCBS waivers designated for children with DD by 2016.10 Certain Medicaid HCBS waivers only target children with ASD.11 Waivers targeting children with ASD are positively associated with health outcomes.12,13 Leslie and colleagues found that Medicaid HCBS waiver characteristics (e.g., cost limit) were associated with parents’ workforce participation and unmet healthcare needs among children with ASD.12,13 Although these studies show promising results of the Medicaid HCBS waivers for children with ASD and their parents, better understanding remains needed for children with DD.

Other aspects of state context affect services use for children with DD. Children with DD ages 3–5 years living in states with less income inequality are, for instance, more likely to participate in early childhood special education compared to children in states with higher income inequality.14 Similarly, narrower versus broader scope state early intervention eligibility criteria are associated with lower early intervention services use among children with special health care needs ages 0–3 years.15 Moreover, school-aged children with special health care needs including those with DD in states with school policies requiring case management for students with disabilities are less likely to repeat a grade than children in states without such policies.16 Yet, little research has comprehensively examined other aspects of state context (e.g., income inequality) along with policy for children with DD.

Greater knowledge on the state variation and determinants of therapy use will benefit health initiatives targeting school-aged children with DD. That is, clinicians, researchers, and advocates may use study findings to advance state policies (e.g., more generous Medicaid HCBS waivers) reducing health inequities stemming from inadequate access to therapy services. This study, therefore, sought to (1) determine if therapy use varies significantly by state and (2) examine associations of ecological factors with therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD. From past research showing considerable state variation in child health services,14,17–19 we hypothesized significant state variation in therapy use among children with DD. We further hypothesized certain factors previously associated with services use such as race and ethnicity,20 household income,4,9 insurance coverage,18,21 income inequality,14 and Medicaid HBCS waiver status12,13 would have significant associations with therapy use among children with DD.

Methods

Design

This was a secondary analysis of data combined from the 2016 and 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). Data on state context were included from the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in 2017, the Department of Education (ED) in 2016–2017, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2016. All data were publicly accessible.

NSCH data

The NSCH is a parent-reported survey about healthcare and health for a nationally representative sample of children ages 0–17 years. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration sponsored, and the U.S. Census Bureau conducted the NSCH. State-level samples were allocated to produce an approximately equal number of completed questionnaires across states (range = 1070–1784 completed questionnaires). The NSCH methodology has been previously detailed.22,23

ACS, HRSA, and ED data

We obtained state income inequality data from the 2017 ACS.24 Data on the number of medically underserved areas in 2017 were obtained through HRSA.25 Data on the percentage of children with disabilities who received Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part B (ages 6–21 years) in 2016–2017 were obtained from the U.S. Department of Education.26

Medicaid HCBS waiver data

Data on Medicaid HCBS waivers active in 2016 were primarily collected from waiver applications and renewal documents available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Waivers needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) the waiver served children with DD, ASD, and/or complex medical conditions; and (2) the waiver specified children be < 23 years. For waivers that could not be located on the CMS website, investigators searched individual state Medicaid websites and contacted state Medicaid administrators. Information on several ASD-specific waivers was additionally obtained from a past study.11

Sample

The sample included 9984 U S. children with DD ages 6–17 years. All children currently had one or more parent-reported DD. We used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list2 to determine which DD conditions were asked about in the 2016 and 2017 NSCH. The following 12 conditions were used: ADHD, learning disability, developmental delay, speech and language disorder, ASD, blindness, ID, deafness, epilepsy, CP, Tourette syndrome, and Down syndrome.

Measures

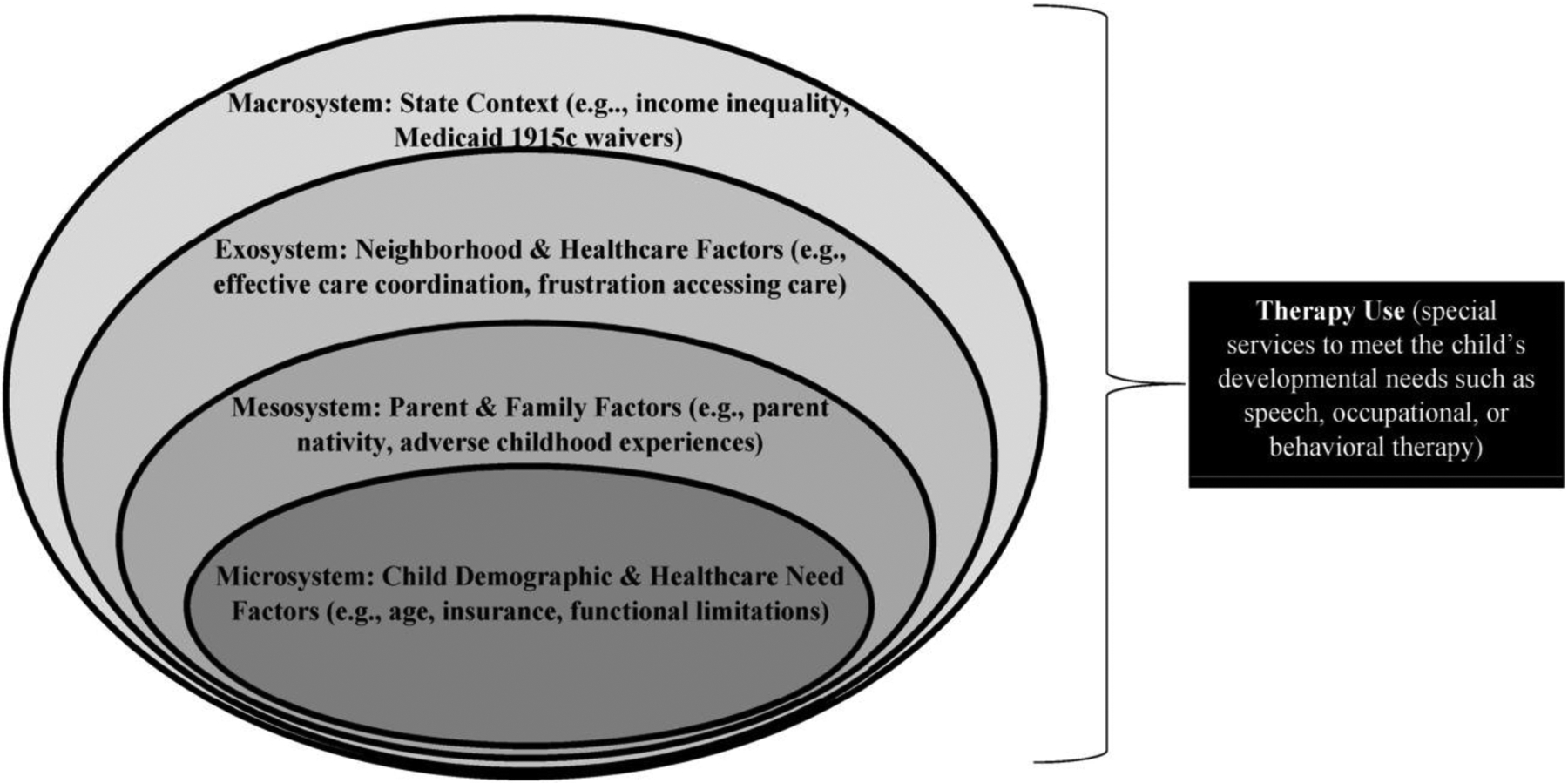

We used ecological systems theory27 to comprehensively determine factors that may affect therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD (Fig. 1). The selection of factors at each ecological level was determined by our literature review and the accessible data. The microsystem (system closest to the individual) involved the child’s characteristics. The mesosystem level (interaction between different aspects of an individual’s microsystem) included parent and family characteristics. The exosystem (environments the individual interacts with) consisted of neighborhood and healthcare factors. The macrosystem covered state context including policy. All variable categories are displayed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study Conceptual Framework using the Ecological Model to Understand Therapy Use Determinants for School-Aged Children with Developmental Disabilities.

Table 1.

Characteristics of U.S. Children with Developmental Disabilities Ages 6–17 years, by Therapy Use: Univariate and Bivariate Results.

| Overall (n = 9984) | No Therapy Use (n = 6744) | Therapy Use (n = 3240) | Therapy Use: OR (95% CI) | Predicted Margin (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Number (%) | 9,436,946 (19.0%) a | 6,175,432 (65.4%) | 3,261,513 (34.6%) | ||

| Child Factors | |||||

| Age, years | |||||

| 6–11 (n = 4167) | 48.6% | 41.3% | 62.7% | 1.00 | 0.45 (0.42–0.47) |

| 12–17 (n = 5817) | 51.4% | 58.8% | 37.3% | 0.42 (0.34–0.52)*** | 0.25 (0.22–0.28) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (n = 6400) | 63.9% | 61.1% | 69.1% | 1.00 | 0.37 (0.34–0.40) |

| Female (n = 3584) | 36.1% | 38.9% | 30.9% | 0.70 (0.56–0.88)** | 0.30 (0.26–0.33) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic (n = 7100) | 52.6% | 54.5% | 49.1% | 1.00 | 0.32 (0.30–0.34) |

| Hispanic (n = 1152) | 24.3% | 24.4% | 24.3% | 1.10 (0.80–1.52) | 0.34 (0.27–0.41) |

| Black, non-Hispanic (n = 696) | 15.3% | 13.8% | 18.0% | 1.45 (1.07–1.95)* | 0.41 (0.34–0.48) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic (n = 1036) | 7.8% | 7.4% | 8.6% | 1.30 (0.94–1.80) | 0.38 (0.31–0.46) |

| Health insurance coverage | |||||

| Public health insurance only (n = 2741) | 41.3% | 40.7% | 41.8% | 1.00 | 0.37 (0.33–0.42) |

| Private health insurance only (n = 5980) | 45.3% | 46.0% | 44.7% | 0.74 (0.59–0.93)* | 0.31 (0.28–0.33) |

| Private & public health insurance (n = 759) | 8.3% | 6.8% | 9.7% | 1.55 (1.05–2.30)* | 0.48 (0.40–0.57) |

| Uninsured (n = 365) | 5.0% | 6.5% | 3.7% | 0.60 (0.37–0.95)* | 0.26 (0.18–0.35) |

| Born preterm (gestational age<37 weeks) | |||||

| Not born preterm (n = 8123) | 81.6% | 81.7% | 81.5% | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.37) |

| Born preterm (n = 1654) | 18.4% | 18.3% | 18.5% | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | 0.35 (0.30–0.40) |

| Functional limitations | |||||

| No limitations (n = 7585) | 76.4% | 86.6% | 57.0% | 1.00 | 0.26 (0.23–0.28) |

| Functional limitations (n = 2399) | 23.6% | 13.4% | 43.0% | 4.89 (3.80–6.29)*** | 0.63 (0.58–0.68) |

| Current individualized education program (IEP) | |||||

| No IEP (n = 5434) | 55.7% | 74.9% | 19.4% | 1.00 | 0.12 (0.10–0.14) |

| IEP (n = 4485) | 44.3% | 25.1% | 80.6% | 12.40 (9.64–15.94)*** | 0.63 (0.59–0.66) |

| Parent or Family Factors | |||||

| Nativity | |||||

| Parent born in U.S. (n = 8001) | 71.7% | 73.3% | 68.6% | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.31–0.35) |

| Parent not born in U.S. (n = 1108) | 18.2% | 18.0% | 18.8% | 1.12 (077–1.62) | 0.36 (0.27–0.44) |

| Child born in U.S. parent birthplace unknown (n = 771) | 10.1% | 8.8% | 12.6% | 1.54 (1.06–2.24)* | 0.43 (0.34–0.52) |

| Primary household language | |||||

| English (n = 9551) | 90.7% | 89.9% | 92.1% | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) |

| Spanish or Other non-English Language (n = 363) | 9.3% | 10.1% | 7.9% | 0.77 (0.47–1.27) | 0.29 (0.19–0.39) |

| Highest parent education level | |||||

| High school or less (n = 1853) | 35.7% | 35.3% | 36.4% | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.30–0.40) |

| More than high school (n = 7974) | 64.3% | 64.8% | 63.6% | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 0.34 (0.32–0.37) |

| Family structure | |||||

| Two parents married (n = 6409) | 57.8% | 58.9% | 55.8% | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.30–0.36) |

| Two parents unmarried (n = 649) | 9.4% | 8.9% | 10.4% | 1.23 (0.79–1.92) | 0.38 (0.28–0.48) |

| Single mother (n = 1716) | 21.3% | 21.7% | 20.4% | 0.99 (0.78–1.26) | 0.33 (0.29–0.38) |

| Other family structure (n = 1021) | 11.5% | 10.5% | 13.3% | 1.34 (0.95–1.88) | 0.40 (0.33–0.48) |

| Household income level | |||||

| 0–99% FPL (n = 1464) | 27.1% | 25.1% | 30.9% | 1.00 | 0.39 (0.33–0.45) |

| 100–199% FPL (n = 1823) | 24.4% | 25.2% | 22.9% | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.32 (0.28–0.37) |

| 200–399% FPL (n = 2981) | 23.6% | 24.2% | 22.4% | 0.75 (0.56–1.01) | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) |

| ≥400% FPL (n = 3716) | 24.9% | 25.5% | 23.8% | 0.76 (0.57–1.01) | 0.33 (0.30–0.36) |

| Mother’s overall health status | |||||

| No biologic or adoptive mother (n = 1020) | 11.7% | 10.8% | 13.4% | 1.00 | 0.40 (0.32–0.47) |

| Health not very good or excellent (n = 4059) | 44.8% | 45.6% | 43.4% | 0.77 (0.54–1.09) | 0.33 (0.30–0.37) |

| Health very good or excellent (n = 4607) | 43.5% | 43.7% | 43.2% | 0.80 (0.56–1.13) | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) |

| Father’s overall health status | |||||

| No biologic or adoptive father (n = 2485) | 31.0% | 30.6% | 31.6% | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) |

| Health not very good or excellent (n = 3004) | 29.5% | 29.2% | 30.1% | 1.00 (0.76–1.30) | 0.35 (0.31–0.40) |

| Health status very good or excellent (n = 4242) | 39.5% | 40.2% | 38.3% | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 0.33 (0.30–0.37) |

| Adverse childhood experiences | |||||

| No adverse childhood experiences (n = 3968) | 35.3% | 35.4% | 35.1% | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.30–0.38) |

| 1 adverse childhood experience (n = 2460) | 26.1% | 27.0% | 24.4% | 0.92 (0.70–1.19) | 0.32 (0.28–0.36) |

| ≥2 adverse childhood experiences (n = 3426) | 38.6% | 37.6% | 40.5% | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.36 (0.32–0.40) |

| Neighborhood Factors | |||||

| Supportive neighborhood | |||||

| Does not live in a supportive neighborhood (n = 4415) | 50.5% | 49.6% | 52.1% | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.32–0.39) |

| Lives in a supportive neighborhood (n = 5271) | 49.5% | 50.4% | 47.9% | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 0.33 (0.30–0.36) |

| Neighborhood amenities | |||||

| 2 or fewer amenities (n = 4143) | 41.2% | 42.8% | 38.0% | 1.00 | 0.32 (0.29–0.35) |

| 3 or more amenities (n = 5493) | 58.9% | 57.2% | 62.0% | 1.22 (1.00–1.49) | 0.36 (0.33–0.39) |

| Healthcare Factors | |||||

| Adequate insurance | |||||

| No adequate insurance (n = 3273) | 30.5% | 31.5% | 28.7% | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.29–0.37) |

| Adequate insurance (n = 6311) | 69.5% | 68.6% | 71.3% | 1.14 (0.91–1.42) | 0.36 (0.33–0.39) |

| Frustrated in efforts to get services | |||||

| Never frustrated in efforts (n = 6742) | 67.1% | 72.6% | 56.7% | 1.00 | 0.29 (0.26–0.32) |

| Sometimes frustrated in efforts (n = 2575) | 26.4% | 21.9% | 34.8% | 2.03 (1.60–2.59)*** | 0.46 (0.40–0.51) |

| Usually or always frustrated in efforts (n = 612) | 6.5% | 5.5% | 8.5% | 1.99 (1.43–2.76)*** | 0.45 (0.37–0.52) |

| Foregone healthcare | |||||

| No Foregone care (n = 9322) | 92.2% | 92.4% | 91.9% | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.37) |

| Foregone care (n = 640) | 7.8% | 7.6% | 8.1% | 1.06 (0.66–1.71) | 0.36 (0.25–0.46) |

| Preventative medical care | |||||

| No preventative care (n = 1257) | 14.9% | 16.9% | 11.3% | 1.00 | 0.26 (0.21–0.32) |

| Preventative care (n = 8654) | 85.1% | 83.2% | 88.7% | 1.59 (1.17–2.16)** | 0.36 (0.34–0.39) |

| Effective care coordination | |||||

| Did not need (n = 2534) | 29.1% | 32.7% | 22.4% | 1.00 | 0.26 (0.22–0.30) |

| Needed but did not receive (n = 2766) | 27.3% | 22.7% | 36.1% | 2.33 (1.78–3.04)*** | 0.46 (0.41–0.50) |

| Received all needed care coordination (n = 4640) | 43.6% | 44.6% | 41.5% | 1.36 (1.05–1.76)* | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) |

| Shared decision making | |||||

| No decisions needed (n = 5552) | 63.0% | 66.8% | 55.8% | 1.00 | 0.31 (0.28–0.34) |

| Never/Sometimes Shared Decision Making (n = 614) | 6.4% | 5.3% | 8.5% | 1.93 (1.28–2.91)** | 0.46 (0.36–0.56) |

| Usually/Always Shared Decision Making (n = 3741) | 30.6% | 28.0% | 35.7% | 1.53 (1.23–1.90)*** | 0.40 (0.36–0.44) |

| Use of complementary health approaches | |||||

| No use (n = 8585) | 89.3% | 90.2% | 87.6% | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.31–0.36) |

| Use of complementary health approaches (n = 1305) | 10.7% | 9.9% | 12.4% | 1.29 (0.97–1.72) | 0.40 (0.33–0.46) |

| State Factors | |||||

| Income Inequality (Gini coefficient quartiles) | |||||

| 0.4225–0.4524 (n = 2503) | 10.8% | 10.8% | 10.7% | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) |

| 0.4525–0.4668 (n = 2376) | 17.6% | 17.0% | 18.6% | 1.10 (0.88–1.38) | 0.37 (0.33–0.40) |

| 0.4669–0.4794 (n = 2427) | 31.4% | 33.4% | 27.7% | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | 0.30 (0.26–0.35) |

| 0.4795–0.5281 (n = 2505) | 40.3% | 38.9% | 43.0% | 1.11 (0.86–1.43) | 0.37 (0.32–0.41) |

| Medically Underserved Areas | |||||

| State below median (n = 4647) | 20.3% | 19.3% | 22.5% | 1.00 | 0.38 (0.35–0.41) |

| State at or above median (n = 5337) | 79.7% | 80.8% | 77.5% | 0.82 (0.69–0.98)* | 0.34 (0.31–0.37) |

| Percent of Children Receiving IDEA Part B Services | |||||

| State below median (n = 5053) | 63.5% | 66.4% | 58.6% | 1.00 | 0.32 (0.28–0.35) |

| State at or above median (n = 4931) | 36.6% | 33.6% | 41.4% | 1.39 (1.14–1.69)** | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) |

| State Medicaid HCBS Waiver Status | |||||

| No waiver (n = 5308) | 60.6% | 62.3% | 57.4% | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) |

| 1 waiver (n = 2880) | 20.4% | 19.8% | 21.5% | 1.18 (0.95–1.46) | 0.36 (0.33–0.40) |

| 2 or more waivers (n = 1796) | 19.0% | 17.9% | 21.2% | 1.29 (1.02–1.63)* | 0.38 (0.34–0.43) |

| Survey year | |||||

| 2016 (n = 6918) | 49.4% | 51.0% | 46.2% | 1.00 | 0.32 (0.30–0.35) |

| 2017 (n = 3066) | 50.6% | 49.0% | 53.8% | 1.21 (0.99–1.49) | 0.37 (0.33–0.41)_ |

Note. Analyses were weighted. Therapy use refers to special services received to meet the child’s developmental needs such as speech, occupational, or behavioral therapy.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; GED, general educational development; HCBS, home and community-based services; IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; IEP, individualized education program; U.S., United States.

This is the percent of U.S. children ages 6–17 years with current developmental disabilities and data on therapy use among all children ages 6–17 years in the dataset.

Microsystem: child factors

Child factors included age (years), sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, preterm birth status, functional limitations status assessed by the Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener,28 and if the child currently had an individualized education program (IEP).

Mesosystem: parent and family factors

Parent and family factors included parent nativity; primary household language; highest parent education level; family structure (two parents married, two parents unmarried, single mother, other family structure); household income level relative to the federal poverty level; overall maternal health status; overall paternal health status; and adverse childhood experiences. Nine adverse childhood experiences were assessed: (1) hard to get by on family’s income - cannot afford basics; (2) parent or guardian divorced or separated; (3) parent or guardian died; (4) parent or guardian served time in jail; (5) witnessed domestic violence; (6) victim or witness of neighborhood violence; (7) lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed; (8) lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs; and (9) treated or judged unfairly because of his/her race or ethnic group.

Exosystem: neighborhood and healthcare factors

Neighborhood factors included if the child lived in a supportive neighborhood and had neighborhood amenities (two or less versus three or more). Supportive neighborhood was measured with the following three items: (1) people in my neighborhood help each other out, (2) we watch out for each other’s children in this neighborhood, and (3) when we encounter difficulties, we know where to go for help. Neighborhood amenities included whether the child lived in a neighborhood with sidewalks and walking paths; a park or playground; recreation center, community center or boys’ and girls’ club; and a library or book mobile.

Healthcare factors included adequate insurance, frustration accessing services, foregone healthcare, preventive medical care, effective care coordination, shared decision-making, and complementary health approaches use in the past 12-months. Adequate health insurance, foregone healthcare, effective care coordination, and shared decision-making were previously used composite measures each derived from multiple items (Appendix).8,9,16,21 Frustration accessing services was assessed by whether the parent answered always or usually versus sometimes or never to the following item: “During the past 12 months, how often were you frustrated in your efforts to get services for this child?” Preventive medical care was determined if parents reported one or more visit(s) in response to the following item: “During the past 12 months, how many times did this child visit a doctor nurse, or other health care professional to receive a preventive check-up?” Complementary health approaches use was assessed by the following binary (yes/no) item: “During the past 12-months, did this child use any type of alternative health care or treatment?”

Macrosystem: state factors

State factors included income inequality in 2017, medically underserved areas in 2017, percent of children with disabilities receiving services under IDEA Part B in 2016–2017, and one or more active Medicaid HCBS (1915c) waiver(s) targeting children with DD in 2016. State income inequality as a Gini coefficient was available in the 2017 ACS. The Gini coefficient is a value ranging from 0 to 1, with 0 representing complete income equality and 1 representing complete income inequality. Per related research, coefficients were broken into quartiles (McManus et al., 2011). Medically underserved areas are designated by HRSA as having too few providers, high infant mortality, high poverty, or a high elderly population.29 We used the median (73) of medically underserved areas to create a binary variable (below versus at or above median), per past research.19 The U.S. Department of Education provides the percentage of students ages 6–21 years with any disability who received services under IDEA Part B per state each school year.26 We used the median percentage of children ages 6–21 years with disabilities across states (9.28%) to create a binary variable (below versus at or above median).

Number of Medicaid HCBS waivers per state was determined by the three eligibility criteria (active in 2016, included DD, and applied to children). We included Katie Beckett waivers if they were part of state Medicaid HCBS waivers, and we did not include states (AZ and RI) that primarily used Medicaid 1115 waivers that may also cover home based services for children with DD. For states with one or more waiver(s), we examined the following characteristics: years since the waiver’s initial enactment, enrollment limit, cost limit, and estimated cost. Years since the waiver’s enactment was computed by subtracting the year when the waiver was first enacted from 2016. For states with more than one waiver, we used the years since the oldest waiver was enacted. The enrollment limit is the maximum number of children that can be served each year. For states with more than one waiver, the enrollment limit was computed by summing the enrollment limit for each waiver. The cost limit is the maximum amount that can be spent per individual through the waiver. For all waivers, the cost of services per individual must be lower than the costs of institutionalization. Thus, in waivers that indicated “no cost limit” or an “institutional cost limit,” the cost limit was whatever the waiver calculated the institutional costs to be. Estimated costs for each waiver is defined as the total annual estimated costs of waiver services per individual expected to participate in the waiver. To calculate the cost limit in states with more than one waiver, an average of the cost limits across all waivers was computed. The same method was used to compute estimated costs in states with more than one waiver. Per past research,12,13 we normalized waiver enrollment limit, cost limit, and estimated cost across states. This made it so each had a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, which allowed the estimated odds ratios to be interpreted as the effect of a one standard deviation change in the given measure.

Therapy use

Therapy services use was determined with two binary (yes/no) items. The first item was, “Has this child ever received special services to meet his or her developmental needs such as speech, occupational, or behavioral therapy?” If the child’s parent answered “Yes,” the following was asked: “Is the child currently receiving these special services?” If the child’s parent answered “Yes” to the second question, the child was determined to currently use therapy services.

Analysis

We first computed descriptive statistics to determine variable properties. We then computed descriptive univariate and bivariate statistics to determine the sample’s characteristics and differences in therapy use by each ecological factor. To determine state variation in therapy use and associations with select ecological factors, we fit four multilevel logistic regression models in which a random intercept for state was used and the variance of the random effect was assessed.30 The first model had no covariates and described overall state variation in therapy use. The second model included child, parent and family, and healthcare factors that had bivariate associations with therapy use significant at a two-sided p < .10 level. The third model included these same factors and the state factors that had bivariate associations with therapy use significant at a two-sided p < .10 level. The fourth model was only among children with DD living in states with one or more Medicaid HCBS waiver and included the factors in the prior two models and the waiver characteristics (e.g., estimated waiver costs). For each model, odds ratios (OR) or adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed along with p-values, state-level variance, and standard error of the state-level variance. To aid in the interpretation of model estimates, we additionally computed the predicted margins (probabilities) with their 95% CIs (i.e., the average probability of the outcome if everyone in the dataset was at the same variable level such as male or publicly insured). As a sensitivity analysis to better understand the effects that race and ethnicity may have on therapy use, we separately tested the following interaction terms as part of the third model: race and ethnicity by insurance status, race and ethnicity by IEP status, race and ethnicity by functional limitations status, and race and ethnicity by waiver status. For any statistically significant interaction, we computed and plotted the predicted margins. Given the complex survey sampling design and to reduce bias in estimates, we computed scaled design weights per guidance by Carle.31 All other analyses followed survey weighting guidance22 and were performed in Stata 16.0.32 A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance and mean variance inflation factors for each model were <2 suggesting that bias due to multicollinearity was not a major concern.

Results

Participant characteristics

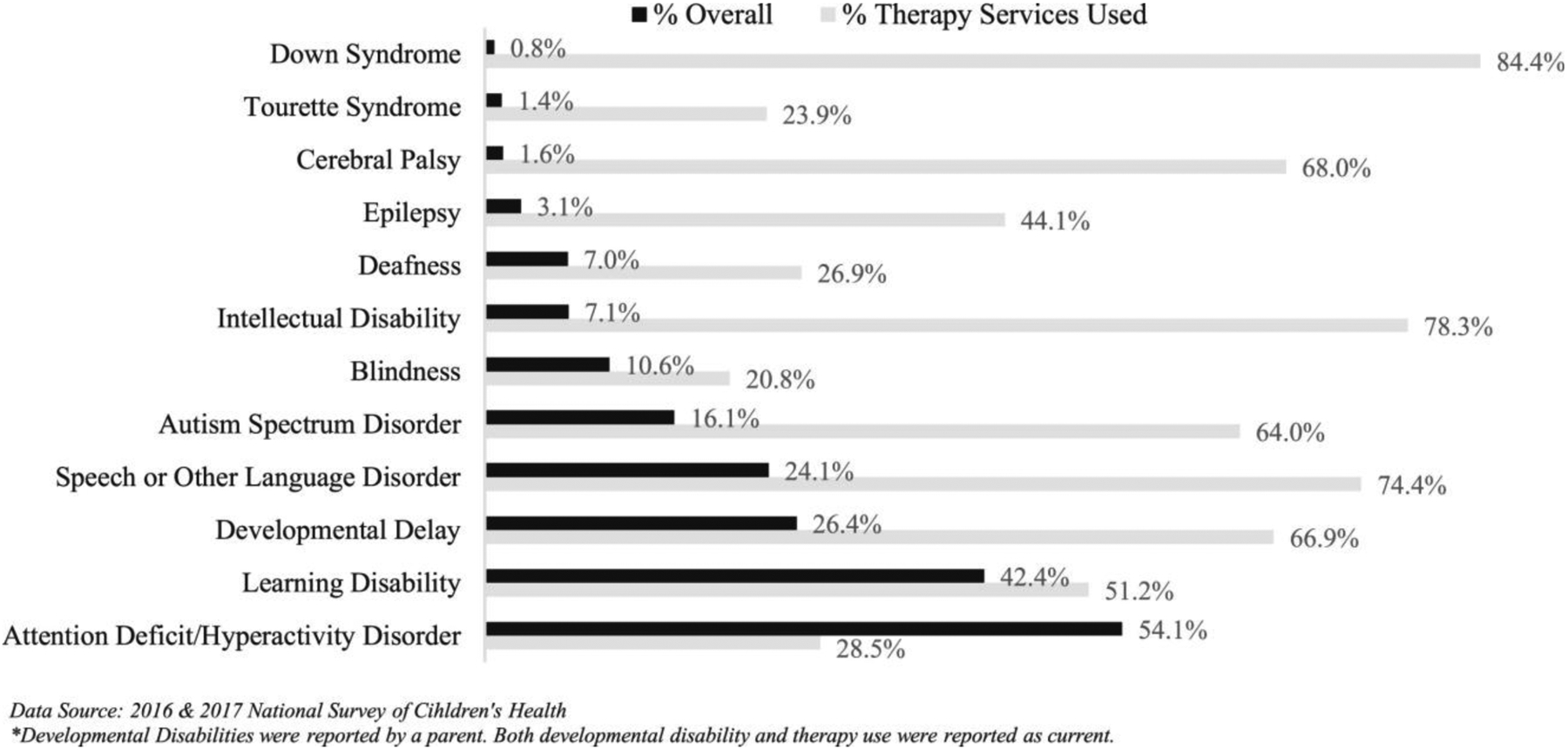

The sample represented an estimated 9,436,946 U S. children ages 6e17 years with DD. This accounted for approximately 19.0% of children with DD ages 6–17 years nationwide. Prevalence of DD conditions is shown in Fig. 2: ADHD was most prevalent (54.1%), and Down syndrome was least prevalent (0.8%). Table 1 shows all participant characteristics.

Fig. 2.

Specific conditions and therapy use among U.S. School-Aged children with developmental disabilities (n = 9984).

Therapy use results

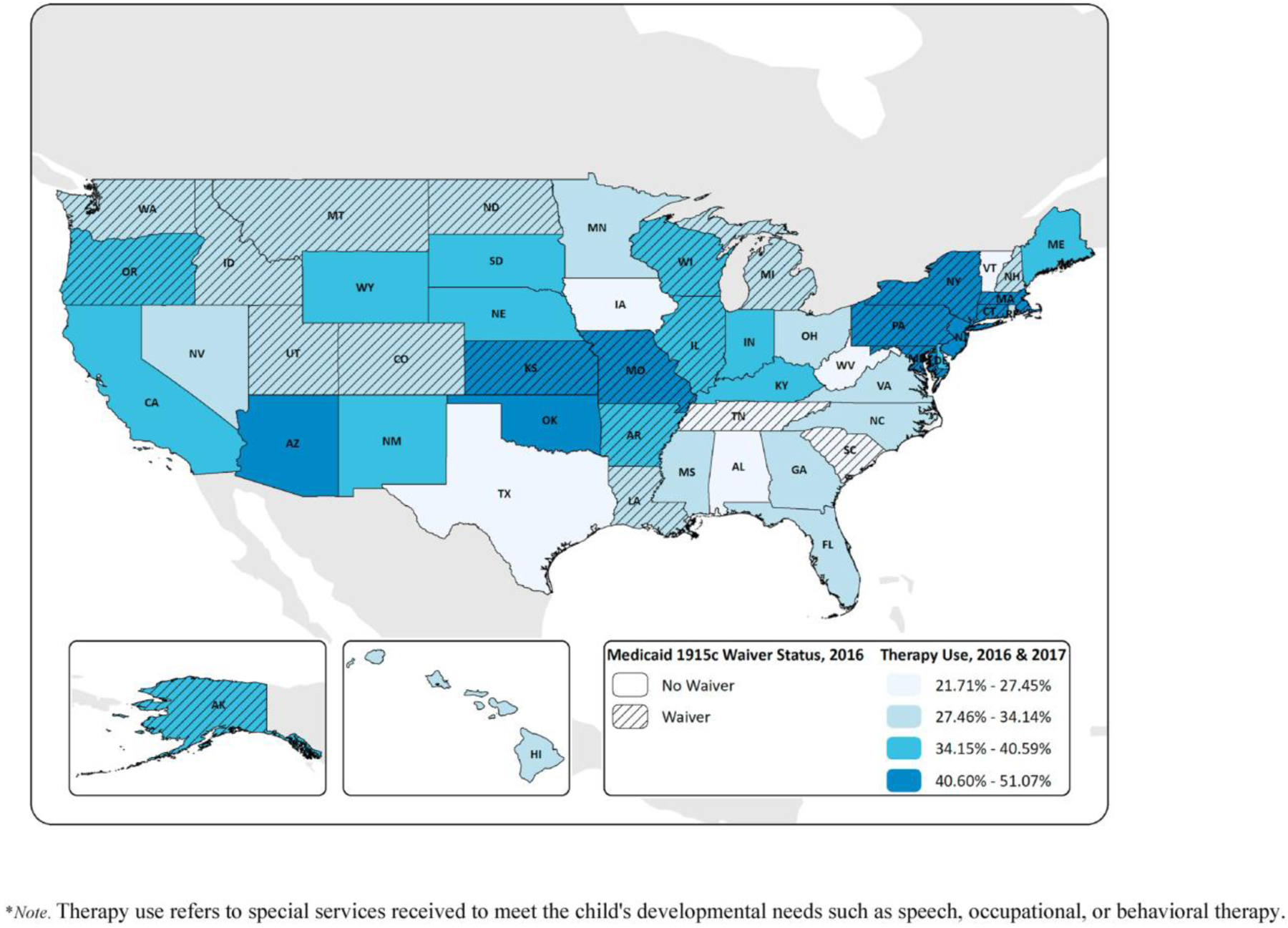

Overall, 34.6% of U.S. school-aged children with DD currently used therapy services and 54.6% ever used therapy services. The average child age at first use of therapy services was 5.1 years (SD = 2.9). Therapy use among school-aged children with DD varied considerably by condition (Fig. 2). Children with Down syndrome were most likely to use therapy services, while children with blindness, Tourette syndrome, or ADHD were least likely to use therapy services. Table 1 displays all other bivariate therapy use associations. Statistically significant variation in therapy use among children with DD was found across states (σ2 = 0.11, SE = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.06–0.22). Iowa had the lowest percentage of therapy use (21.7%), and the District of Columbia had the highest percentage of therapy use (51.1%) among school-aged children with DD. Fig. 3 displays therapy use variability and presence of Medicaid HCBS waivers across states.

Fig. 3.

Therapy use and medicaid HCBS waiver status among school-aged children with developmental disabilities across states.

Medicaid HCBS waiver characteristics

Of the 33 eligible Medicaid HCBS waivers, 10 specifically served children with ASD and the remaining 23 served children with DD and/or special needs generally. Overall, 39.4% of school-aged children with DD lived in a state with one or more Medicaid HCBS waiver. Table 2 summarizes key waiver characteristics.

Table 2.

Summary of medicaid HCBS waivers targeting children with developmental disabilities.

| Number of waivers (n = 33) | |

|---|---|

| 1 waiver | AK, AR, KA, LA, MA, MD, MI, MT, ND, NH, PA, SC, UT, WA |

| 2 or more waivers | CO, CT, ID, IL, MO, NY, OR, TN, WI |

| Mean years since first waiver enacteda (SD) | 13.7 (8.7) |

| Mean estimated costb (SD) | $30,809.8 (48,545.6) |

| Mean cost limitc (SD) | $149,375.6 (112,361.5) |

| Mean maximum number of children servedd (SD) | 1495.3 (1961.4) |

Note. Estimated Cost: this is listed in the appendix of every waiver and demonstrates the cost of each year of enacting the waiver per individual. Cost Limit: maximum amount of money that can be spent per individual on the waiver. Maximum Children Served: maximum number of participants who can be served by the waiver each year.

Abbreviations. AK, Alaska; AR, Arkansas; KA, Kansas; LA, Louisiana; MA, Massachusetts; MD, Maryland; MI, Michigan; MT, Montana; ND, North Dakota; NH, New Hampshire; PA, Pennsylvania; SC, South Carolina; UT, Utah; WA, Washington; CO, Colorado; CT, Connecticut; ID, Idaho; IL, Illinois; MO, Missouri; NY, New York; OR, Oregon; TN, Tennessee; WI, Wisconsin; HCBS, home and community-based services; SD, standard deviation.

Data sources: Waiver information was gathered systematically from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid, as well as individual state Medicaid websites. In some cases, waivers were collected through email from a state CMS employee, or from Dr. Dianna Velott. Data was collected directly from waiver applications and waiver renewal documents.

Therapy use determinants: multilevel model results

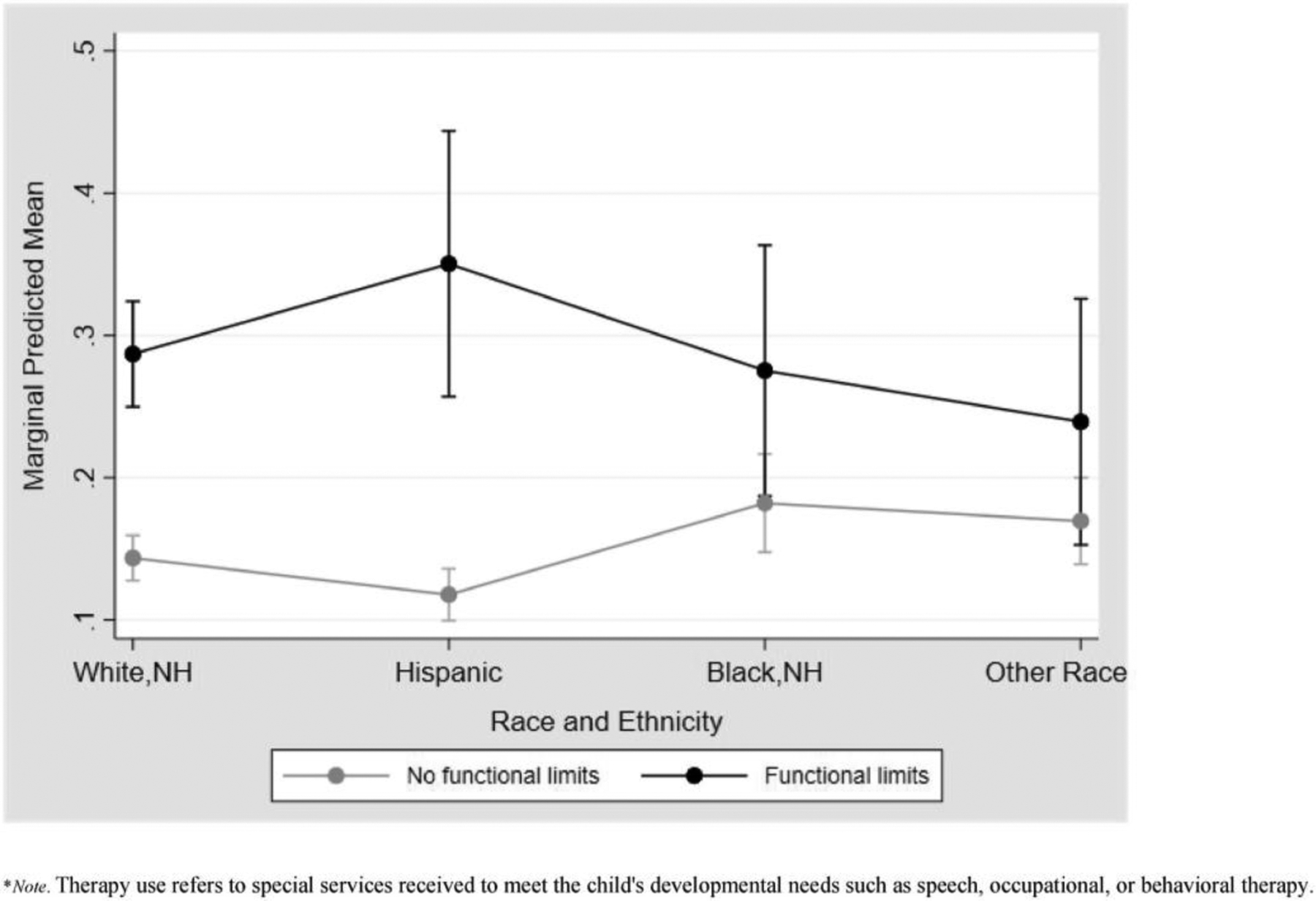

Multilevel model results for the full sample showed statistically significant associations of therapy use with younger versus older child age, having public versus private insurance, having versus not having functional limitations, having versus not having an IEP, being sometimes versus never frustrated in efforts getting services, and needing but not receiving or receiving all needed care coordination versus not needing care coordination (Model 3, Table 3). No state factors had statistically significant associations with therapy use. Sensitivity analysis results showed a statistically significant interaction for race and ethnicity and functional limitations status, specifically being Hispanic and having functional limitations (therapy use predicted probability: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.26–0.44) versus not having functional limitations (therapy use predicted probability: 0.12, 95% CI: 0.10–0.14). Fig. 4 displays a plot of all the predicted probabilities for this interaction.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations of child, family, healthcare, and state characteristics with therapy use among U.S. School-Aged children with developmental disabilities.

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 aOR (95% CI) | Model 2 Margin (95% CI) | Model 3 aOR (95% CI) | Model 3 Margin (95% CI) | Model 4 aOR (95% CI) | Model 4 Margin (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |||||||

| Child age, years | |||||||

| 6–11 | 1.00 | 0.43 (0.41–0.45) | 1.00 | 0.43 (0.41–0.45) | 1.00 | 0.45 (0.42–0.47) | |

| 12–17 | 0.34 (0.29–0.39)*** | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | 0.34 (0.29–0.40)*** | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | 0.32 (0.25–0.41)*** | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | |

| Sex of child | |||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.34–0.37) | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | |

| Female | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 0.34 (0.32–0.37) | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 0.34 (0.32–0.37) | 1.06 (0.85–1.33) | 0.37 (0.34–0.39) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.33–0.36) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.36) | 1.00 | 0.37 (0.35–0.38) | |

| Hispanic | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 0.33 (0.31–0.36) | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 0.33 (0.31–0.36) | 0.85 (0.62–1.16) | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.26 (0.97–1.63) | 0.38 (0.34–0.42) | 1.26 (0.97–1.65) | 0.38 (0.34–0.42) | 1.14 (0.78–1.67) | 0.39 (0.34–0.44) | |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) | 1.06 (0.79–1.43) | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) | 0.81 (0.47–1.37) | 0.34 (0.26–0.41) | |

| Health insurance coverage | |||||||

| Public health insurance only | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | 1.00 | 0.37 (0.35–0.40) | |

| Private health insurance only | 0.80 (0.68–0.94)** | 0.33 (0.31–0.34) | 0.80 (0.68–0.94)** | 0.33 (0.31–0.34) | 0.84 (0.65–1.07) | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | |

| Private & public health insurance | 1.40 (0.97–2.01) | 0.41 (0.36–0.46) | 1.40 (0.97–2.01) | 0.41 (0.36–0.46) | 1.27 (0.67–2.41) | 0.41 (0.32–0.49) | |

| Uninsured | 1.08 (0.75–1.55) | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) | 1.08 (0.79–1.43) | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) | 0.80 (0.42–1.49) | 0.34 (0.25–0.43) | |

| Functional limitations | |||||||

| No limitations | 1.00 | 0.30 (0.29–0.32) | 1.00 | 0.30 (0.29–0.32) | 1.00 | 0.31 (0.29–0.33) | |

| Functional limitations | 2.86 (2.29–3.58)*** | 0.47 (0.44–0.50) | 2.86 (2.29–3.58)*** | 0.47 (0.44–0.50) | 3.52 (2.54–4.88)*** | 0.51 (0.46–0.56) | |

| Current Individualized Education Program (IEP) | |||||||

| No IEP | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.13–0.16) | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.13–0.16) | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.12–0.17) | |

| IEP | 11.71 (9.81–13.97)*** | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) | 11.67 (9.78–13.92)*** | 0.59 (0.55–0.61) | 13.26 (10.40–16.90)*** | 0.60 (0.58–0.63) | |

| Parent or Family Factors | |||||||

| Nativity | |||||||

| Parent born in U.S. | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.33–0.36) | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.33–0.36) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.36) | |

| Parent not born in U.S. | 1.22 (0.93–1.61) | 0.37 (0.33–0.41) | 1.22 (0.93–1.61) | 0.37 (0.33–0.41) | 1.98 (1.34–2.93)** | 0.45 (0.39–0.50) | |

| Child born in U.S., parent birthplace unknown | 1.27 (0.93–1.74) | 0.38 (0.33–0.42) | 1.27 (0.93–1.74) | 0.38 (0.33–0.42) | 1.32 (0.75–2.35) | 0.39 (0.31–0.46) | |

| Healthcare Factors | |||||||

| Frustrated in efforts to get services | |||||||

| Never frustrated in efforts | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.35) | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.35) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | |

| Sometimes frustrated in efforts | 1.27 (1.03–1.61)* | 0.37 (0.35–0.40) | 1.27 (1.03–1.58) | 0.37 (0.35–0.40) | 1.28 (0.92–1.80) | 0.39 (0.35–0.42) | |

| Usually or Always frustrated in efforts | 1.02 (0.67–1.55) | 0.34 (0.28–0.40) | 1.02 (0.67–1.54) | 0.34 (0.28–0.40) | 1.12 (0.72–1.72) | 0.37 (0.30–0.43) | |

| Preventative medical care | |||||||

| No preventative care | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.30–0.39) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) | 1.00 | 0.38 (0.33–0.44) | |

| Yes preventative care | 1.00 (0.73–1.37) | 0.35 (0.33–0.36) | 1.00 (0.73–1.36) | 0.35 (0.33–0.36) | 0.85 (0.55–1.32) | 0.36 (0.35–0.37) | |

| Effective care coordination | |||||||

| Did not need | 1.00 | 0.31 (0.29–0.34) | 1.00 | 0.31 (0.29–0.34) | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) | |

| Needed but did not receive | 1.57 (1.22–2.02)** | 0.38 (0.35–0.40) | 1.57 (1.22–2.03)** | 0.38 (0.35–0.40) | 1.63 (1.10–2.42)* | 0.40 (0.36–0.43) | |

| Received all care coordination | 1.31 (1.04–1.66)* | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.31 (1.04–1.66)* | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.32 (1.00–1.73) | 0.36 (0.34–0.39) | |

| Shared decision making | |||||||

| No decisions needed | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.39) | |

| Never/Sometimes Shared Decision Making | 0.93 (0.62–1.40) | 0.34 (0.28–0.39) | 0.93 (0.62–1.40) | 0.34 (0.28–0.40) | 0.84 (0.40–1.77) | 0.34 (0.25–0.43) | |

| Usually/Always Shared Decision Making | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 0.99 (0.70–1.39) | 0.36 (0.33–0.39) | |

| State Factors | |||||||

| Medically Underserved Areas | |||||||

| State below median | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.00 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | |||

| State at or above median | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) | 0.37 (0.35–0.39) | |||

| Percent of Children Receiving Services Under IDEA Part B | |||||||

| State below median | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.36) | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.39) | |||

| State at or above median | 1.09 (0.90–1.31) | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | |||

| State HCBS Waiver Status | |||||||

| No waiver | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.32–0.36) | |||||

| 1 waiver | 1.11 (0.90–1.36) | 0.35 (0.33–0.38) | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.34–0.37) | |||

| 2 or more waivers | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) | 0.36 (0.34–0.39) | 1.15 (0.95–1.41) | 0.37 (0.35–0.40) | |||

| Estimated Waiver Costs | 0.85 (0.81–0.90)*** | 0.29 (0.27–0.32) | |||||

| Waiver Cost Limits | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 0.30 (0.27–0.32) | |||||

| Waiver Enrollment Limits | 0.91 (0.81–1.01) | 0.36 (0.35–0.39) | |||||

| Length of time with waiver(s) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.29 (0.27–0.32) | |||||

| Intercept | 0.53 (0.48–0.58)*** | 0.13 (0.10–0.17)*** | 0.12 (0.08–0.16)*** | 0.14 (0.09–0.22)*** | |||

| State-level variability: variance (standard error) | 0.112 (0.037) | 0.108 (0.035) | 0.101 (0.034) | 0.015 (0.015) |

Note. Therapy use refers to special services received to meet the child’s developmental needs such as speech, occupational, or behavioral therapy. In model 4, the predicted probabilities (margins) for each continuous waiver characteristic variable were computed for the mean of each waiver characteristic variable (e.g., mean length of time since waiver enacted = 14 years).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Data source: 2016 & 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Fig. 4.

Predicted probabilities for interactions between race and ethnicity and functional limitations on therapy use among U.S. School-Aged children with developmental disabilities.

Multilevel model results only including children with DD living in states with one or more Medicaid HCBS waiver(s) demonstrated similar associations of therapy use with child factors (Model 4, Table 3). Differences included that having a parent not born versus born in the U.S. was associated with higher adjusted odds and predicted probability of therapy use among children with DD in waiver states (therapy use predicted probability not born in U.S. = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.39–0.50 versus born in U.S. = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.33–0.36). That is, 0.45 would be the average probability of therapy use if everyone in the data were treated as not born in the U.S. versus 0.35 if everyone in the data were treated as born in the U.S. For the healthcare factors, only needing but not receiving all needed care coordination versus not needing care coordination was associated with higher adjusted therapy use odds for children with DD in waiver states (therapy use predicted probability when care coordination needed but not received = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.36–0.43 versus when no care coordination needed = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.29–0.36). Estimated waiver costs was the only characteristic that had a statistically significant association with therapy use. Higher estimated waiver costs was associated with lower adjusted odds and predicted probability of therapy use (therapy use predicted probability with mean waiver costs ¼ 0.29, 95% CI: 0.27e0.32).

Discussion

This study is one of the first to examine geographic variability and determinants of therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD. In line with our first hypothesis, therapy use did substantially vary across states pointing to geographic disparities in therapy use. Study findings additionally demonstrated that certain child (e.g., IEP) and healthcare (e.g., care coordination need) factors were the most strongly associated with therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD. Results did not, however, show significant associations of certain state factors (e.g., income inequality, Medicaid HCBS waiver status) that have been previously linked to services use and other health-related outcomes for children with DD. Therapy use for children with DD living in states with Medicaid HCBS waivers was associated with higher estimated waiver costs.

Study findings regarding geographic variability in therapy use among U.S. school-aged children with DD mirror those of prior child health services research. That is, states in the Northeast and Northwest along with some states in the Midwest generally had the highest percentage of children with DD using therapy services. Studies on preschool special education participation,14 underinsurance,18 developmental screening and surveillance,33 and pediatric healthcare quality21 have shown similar geographic patterns insofar as states in the Southern region of the U.S. tend to have lower levels of services use and quality. Given the lack of significant association between therapy use and the state factors examined, future work is needed to further understand why geographic disparities in therapy use exist. This might involve key informant interviews to better understand organizational and state context factors affecting pathways to therapy use for children with DD.

Certain child factors (i.e., younger age) and healthcare factors (i.e., frustration accessing services) were significantly related to therapy use. Similar to past research,34 younger age was associated with higher odds and predicted probability of therapy use. Because many children are diagnosed with DD around the time they enter school, therapy use may be more common during middle childhood versus adolescence. Regarding public health insurance, past studies have similarly found that children with DD and public insurance may have higher services utilization.35,36 Particularly for ASD services, insurance reform and increased Medicaid HCBS waiver enactment may have helped reduce some insurance-based disparity in services use.12,37 Per past research,8,38,39 having functional impairment and an IEP were each expectedly associated with therapy use suggesting that children with DD and less impairment and/or no IEP are less likely to use therapy. This may be due in part to a child’s reduced need for therapy services or limited school resources to deliver services to children without an IEP or who have a 504 Plan. Children with DD who do not have an IEP may also be less likely to have a formal diagnosis, which may be required for insurance to cover certain outpatient therapy services. Additional research is warranted to better understand how children with DD and less impairment and/or no IEP use therapy services. The interaction between functional limitations and race and ethnicity was also significant for Latino children, suggesting that those with limitations may be most likely to use therapy services. Associations of therapy use with frustration accessing services and care coordination need are similar to some past research findings.40 That is, difficulty accessing services may be a marker of greater interaction with the healthcare system and ultimately services use despite the frustration endured. Care coordination need may also be somewhat indicative of greater healthcare need and/or condition severity, necessitating therapy use.

Contrary to our hypothesis, state factors were not significantly associated with therapy use overall among U.S. school-aged children with DD. Other studies have shown that certain state factors such as income inequality,14 Medicaid pediatric behavioral health managed care programs,19 and active Medicaid HCBS targeting children with ASD12,13 are associated with services use or unmet needs. This study’s findings did, however, show that among children with DD living in states with one or more Medicaid HCBS higher estimated waiver costs was associated with lower adjusted therapy use odds. This finding suggests that states with higher estimated waiver costs may have more barriers to therapy access for children with DD (e.g., less therapy availability). Other studies examining Medicaid HCBS waiver characteristics targeting children with ASD have shown significant effects of higher enrollment and cost limits but not estimated costs on parental employment and unmet needs.12,13 Estimated waiver costs are known to vary by state, DD condition (e.g., ASD versus intellectual disability), and age group (i.e., children versus adults)10; however, greater understanding of how waiver characteristics and other state context factors impact services use remains needed.

This study had limitations. Because the design was cross-sectional results must be interpreted as correlational. The sample was heterogeneous with respect to DD and had a wide age range. Older children may have had greater exposure to the model predictors (e.g., IEP receipt) potentially decreasing their current therapy use. The therapy use measure included special services to meet the child’s developmental needs such as speech, occupational, or behavioral therapy. Individual therapy types and delivery settings could, therefore, not be examined. Moreover, parents may have underreported therapy use that was not explicitly asked about in the question (e.g., physical therapy). Because DD status and therapy use were parent-reported, results may additionally be influenced by information bias (i.e., under- and/or over-reporting of DD status and/or therapy use). Institutionalized children who may have high therapy services use were not included in the sample. For this reason, therapy use may be underestimated. We also did not have information on overall waiver enrollment and whether children in this study sample were enrolled in a Medicaid HCBS waiver program. Finally, though a comprehensive variable set was examined, there may have been unaccounted for variables.

Conclusions

Significant variation in therapy use among school-aged children with DD by states was found. Therapy use determinants included child and healthcare factors. State factors were not significantly associated with therapy use. Higher Medicaid HCBS waiver cost was associated with reduced therapy use odds and predicted probability among children with DD in states with waivers. Findings highlight geographic disparities in therapy use that may be reduced through multi-level initiatives targeting children with DD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Steven R. Gehrke for his assistance creating Fig. 3.

Funding

Dr. Lindly’s effort was supported by grant #T32HS000063 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388), which is sponsored by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). Dr. Kuhlthau’s effort was supported by Autism Speaks and cooperative agreement UA3MC11054 through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Research Program to the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnotes

Presentation

This work was accepted as an oral presentation at the 2020 Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; however, due to the pandemic, only an abstract of this work was published in a Health Services Research compendium of abstracts accepted for presentation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101198.

Contributor Information

Olivia Lindly, Department of Health Sciences, Northern Arizona University, 1100 S Beaver St, Flagstaff, AZ 86011.

Megan C. Eaves, School of Social Work, Boston University, 264 Bay State Rd, Boston, MA, 02215.

Yue Xu, Department of Disabilities and Human Development, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1640 Roosevelt Rd, Chicago, IL 60608.

Chelsey L. Tarazi, Combined Counseling/School Psychology Program, Northern Arizona University, 801 Knoles Dr, Flagstaff, AZ 86011.

Sowmya R. Rao, Department of Global Health, Boston University School of Public Health, 715 Albany St, Boston, MA 02118.

Karen A. Kuhlthau, Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck St, Boston, MA 02115.

References

- 1.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner M, et al. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4), e20190811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facts About Developmental Disabilities | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019, September. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/facts.html.

- 3.Schieve LA, Gonzalez V, Boulet SL, et al. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey,. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):467e476, 2006–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1480. 10.1542/peds.2005-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benevides TW, Carretta HJ, Ivey CK, Lane SJ. Therapy access among children with autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and attention-deficitehyperactivity disorder: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(12):1291e1298. 10.1111/dmcn.13560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilaver LA, Sobotka SA, Mandell DS. Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in autism-related service use among medicaid-enrolled children. J Autism Dev Disord. Published online November. 2020;21. 10.1007/s10803-020-04797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilaver LA, Havlicek J. Racial and ethnic disparities in autism-related health and educational services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(7). https://journals.lww.com/jrnldbp/Fulltext/2019/09000/Racial_and_Ethnic_Disparities_in_Autism_Related.2.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindly O, Sinche BK, Zuckerman KE. Variation in educational services receipt among US children with developmental conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5): 534e543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross SM, Smit E, Twardzik E, Logan SW, McManus BM. Patient-centered medical home and receipt of Part C early intervention among young CSHCN and developmental disabilities versus delays: NS-CSHCN 2009e2010. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(10):1451e1461. 10.1007/s10995-018-2540-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman C A national analysis of Medicaid home and community based services waivers for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: FY 2015. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;55(5):281e302. 10.1352/1934-9556-55.5.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velott DL, Agbese E, Mandell DS, et al. Medicaid 1915(c) Home- and Community-Based Services waivers for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(4):473e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leslie DL, Iskandarani K, Dick AW, et al. The effects of Medicaid home and community-based services waivers on unmet needs among children with autism spectrum disorder. Med Care. 2017;55(1):57e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie DL, Iskandarani K, Velott DL, et al. Medicaid waivers targeting children with autism spectrum disorder reduce the need for parents to stop working. Health Aff. 2017;36(2):282e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus BM, Carle AC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Ganz M, Hauser-Cram P, McCormick MC. Social determinants of state variation in special education participation among preschoolers with developmental delays and disabilities. Health Place. 2011;17:681e690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McManus BM, Magnusson D, Rosenberg S. Restricting state part C eligibility policy is associated with lower early intervention utilization. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(4):1031e1037. 10.1007/s10995-013-1332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bethell CD, Forrest CB, Stumbo S, Gomvojav N, Carle A, Irwin CE. Factors promoting or potentially impeding school success: disparities and state variations for children with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(Suppl 1):S35eS43. 10.1007/s10995-012-0993-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher-Owens SA, Soobader MJ, Gansky SA, et al. Geography matters: statelevel variation in children’s oral health care access and oral health. Publ Health. 2016;134:54e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kogan MD, Newacheck PW, Blumberg SJ, et al. State variation in underinsurance among children with special health care needs in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):673e680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang MH, Hill KS, Bourdreau AA, Yucel RM, Perrin JM, Kuhlthau KA. Medicaid managed care and the unmet need for mental health care among children with special health care needs. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):882e900. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magana S, Parish SL, Son E. Have racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of ~ health care relationships changed for children with developmental disabilities and ASD? Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;120(6):504e513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bethell CD, Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Schor E, Robertson J, Newacheck PW. A national and state profile of leading health problems and health care quality for US children: key insurance disparities and across-state variations. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3 Suppl):S22eS33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The United States Census Bureau. Associate director of demographic programs, national survey of children’s health. National Survey of Children’s Health Methodology Report; 2016. Published online February 2018 https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/nsch/tech-documentation/methodology/2016-NSCH-Methodology-Report.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- 23.The United States Census Bureau. Associate Director of Demographic Programs, National Survey of Children’s Health. National Survey of Children’s Health Methodology Report; 2017. Published online August 2018 https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/nsch/tech-documentation/methodology/2017-NSCH-Methodology-Report.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- 24.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Information Guide; 2017. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/acs/about/ACS_Information_Guide.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 25.Health Resources and Services Administration. Shortage Areas. data.HRSA.Gov; 2019. Published https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 26.U.S. Department of Education. IDEA Section 618 Data Products: Static Tables; 2020. Published March 6 https://www2.ed.gov/programs/osepidea/618-data/static-tables/index.html. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- 27.Bronfenbrenner U Ecological models of human development. In: International Encyclopedia of Education. second ed. vol. 3. Elsevier; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):38e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health Resources & Services Administration. MUA find. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/mua-find. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- 30.Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carle AC. Fitting multilevel models in complex survey data with design weights: Recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(49). 10.1186/1471-2288-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirai AH, Kogan MD, Kandasamy V, Reuland C, Bethell CD. Prevalence and variation of developmental screening and surveillance in early childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;72(9):857e866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pringle BA, Colpe LJ, Blumberg SJ, Avila RM, Kogan MD. Diagnostic History and Treatment of School-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Special Health Care Needs. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. 2012:1e8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Mandell DS, Lawer L, Cidav Z, Leslie DL. Healthcare service use and costs for autism spectrum disorder: a comparison between Medicaid and private insurance. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(5):1057e1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Baranek G. The impact of insurance coverage types on access to and utilization of health services for U.S. Children with autism. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(8):908e911. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandell DS, Barry CL, Marcus SC, et al. Effects of autism spectrum disorder insurance mandates on the treated prevalence of autism spectrum disorder. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;170(9):887e893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindly O, Chan J, Levy SE, Parker RA, Kuhlthau KA. Service use classes among school-aged children from the autism treatment network registry. Pediatrics. 2020;145(Supplement 1):S140. 10.1542/peds.2019-1895Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payakachat N, Tilford JM, Kuhlthau KA. Parent-reported use of interventions by toddlers and preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatr Serv; 2017. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600524. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindly O, Zuckerman KE, Kuhlthau KA. Healthcare access and services use among US children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. Published online. 2018:1e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.