ABSTRACT

Food sustainability, e.g., fruit and vegetables, is a major agricultural problem that requires monitoring. Rhizosphere microbiomes’ abundance and functionality are essential in promoting tomato plants’ growth and health. We selected farms in South Africa’s North West Province and present the metagenomes of their tomato rhizospheres and associated functional potentials.

ANNOUNCEMENT

The North West Province is a semiarid region with high temperatures. The soil in this region is populated by important microorganisms, with essential characteristics that promote the planting of tomatoes (1). Tomatoes produce annual crops of about 600,000 tonnes and find their way to South Africa through Europe and South American countries like Peru and Ecuador (2). The availability of these fruits in South Africa will enhance food production for human consumption because of their richness in essential vitamins and carotenoids (3). Three main cultivars of tomatoes are predominant in South Africa, namely, round or fresh tomatoes, Roma tomatoes, and cherry tomatoes, contributing about 24% of the total vegetable production in South Africa (4). Tomatoes are cultivated in open fields under irrigation in the following South African provinces: Eastern Cape, Western Cape, northern Kwazulu-Natal, North West, Mpumalanga, and Limpopo.

We collected the soil samples used in this study from the root region of Roma tomato plants at the experimental farm of the North-West University, Mafikeng (26°019′36.9″S, 26°053′19.0″E; 25°47′19.1″S, 25°37′05.1″E; 25°47′17.0″S, 25°37′03.2″E; altitude, 159 km). The site has a 450-mm annual rainfall record and regional temperatures ranging from 25°C to 37°C (5). The experimental soil samples were collected from the rhizosphere of healthy and diseased tomato plants and the bulk soil. Bulk soil, which served as the control soil, was collected from a natural grassland with no tomato plantation, 20 m from the tomato plantation field. We took rhizosphere soil from the Roma tomato plants from three different areas of a site. Fifteen samples were put in separate sterile polyethene bags, kept in a cold box at −4°C, and transported to the laboratory. All collected soil samples were then stored at a temperature of −20°C before extraction of DNA for shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

From the stored rhizosphere soil, 5 g from each sample was measured using a calibrated scale. DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Soil kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). The quality of the extracted DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

The libraries were prepared with 50 ng DNA using a Nextra DNA Flex kit, undergoing fragmentation and the ligation of adapter sequences. The final concentrations of the libraries were measured using the Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) HS assay kit (Life Technologies), and the mean lengths of the DNA fragments were ascertained using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The libraries were then monitored, combined at 0.6 nM, and sequenced using a NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina) with 300 cycles.

SolexaQA v1.6 was used to conduct the quality control (QC) of raw data, reduce low-quality reads, and remove replicate data (6). Duplicate read inferred sequencing error estimation (DRISEE) enables us to assess the error of sequenced samples caused by artificial replicated sequenced data (7). We employed the default settings of the MG-RAST v4.0.3 server to perform analytical processing downstream (8, 9) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sequence reads for the rhizosphere soil samples analyzed

| Samplea | Data before QC |

Data after processing |

Data after QC |

Data after alignment |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | No. of sequence reads | Mean GC content (%) | Mean sequence length (bp) | No. of artificial duplicate read sequences | No. of known proteins predicted | No of RNA features predicted | Size (bp) | No. of sequence reads | Mean GC content (%) | Mean sequence length (bp) | No. of known proteins identified | No of RNA features identified | |

| HT21 (HR) | 2,152,004,650.3 | 13,739,258.3 | 64 ± 10 | 154 ± 32 | 836,435 | 7,850,484.3 | 28,853 | 765,041,235.3 | 12,665,143.7 | 63 ± 9 | 155 ± 33 | 3,985,525.7 | 5,962.7 |

| HT21 (DR) | 1,409,528,303.3 | 19,765,082 | 64 ± 10 | 155 ± 32 | 757,641.7 | 4,208,873.7 | 30,027 | 1,352,124,415 | 11,966,279.7 | 64 ± 9 | 156 ± 39 | 4,178,206.3 | 7,656.7 |

| HT21 (BR) | 1,477,197,003 | 138,145,859.3 | 65 ± 9 | 155 ± 32 | 374,748 | 11,448,097.3 | 25,322.7 | 1,385,218,693 | 5,247,459 | 64 ± 9 | 156 ± 34 | 2,515,439.7 | 5,439.3 |

HR, healthy rhizosphere; DR, diseased rhizosphere; BR, bulk rhizosphere.

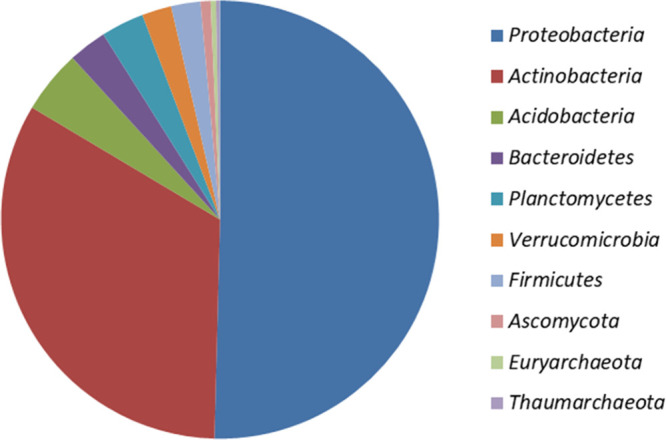

The domain or kingdoms obtained according to the taxonomic system are Bacteria, Eukaryota, and Archaea. The most abundant phyla belonged to the Bacteria domain; Proteobacteria (38.8 to 54%) and Actinobacteria (25.4 to 35.5%) were the most abundant, and others, such as Acidobacteria (2.3 to 5.2%), Bacteroidetes (3.0 to 3.9%), Planctomycetes (2.6 to 3.4%), Verrucomicrobia (2.2 to 2.3%), and Firmicutes (1.7 to 2.4%), were also significant. Moreover, reads for fungi (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) and archaea (Thaumarchaeota and Euryarchaeota) were also identified but at <1% relative abundance (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Abundant phyla obtained according to the taxonomic system.

Functional annotation after mapping with SEED subsystems (10) revealed the presence of the following important attributes: carbohydrates (13.2 to 14.8%), clustering-based systems (12.7 to 12.8%), amino acids and derivatives (10.1 to 10.3%), protein metabolism (8.2 to 8.3%), DNA metabolism (4.3 to 4.6%), cell wall and capsule (3.4 to 3.6%), RNA metabolism (3.3 to 3.5%), and stress response (2.5 to 2.7%).

Data availability.

The metagenomes of rhizosphere soil sequence reads were submitted to the NCBI with BioProject accession number PRJNA766489 and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers SRX12366062, SRX12366063, and SRX12366064 (healthy), SRX12366065, SRX12366066, and SRX12366067 (diseased), and SRX12366068, SRX12366069, and SRX12366070 (bulk).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O.O.B. acknowledges the National Research Foundation (South Africa) grants (UID123634 and UID132595) that support research in our laboratory.

Contributor Information

Olubukola Oluranti Babalola, Email: olubukola.babalola@nwu.ac.za.

John J. Dennehy, Queens College CUNY

REFERENCES

- 1.Babalola OO, Akinola SA, Ayangbenro AS. 2020. Shotgun metagenomic survey of maize soil rhizobiome. Microbiol Resour Announc 9:e00860-20. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00860-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manzanero-Medina GI, Vásquez-Dávila MA, Lustre-Sánchez H, Pérez-Herrera A. 2020. Ethnobotany of food plants (quelites) sold in two traditional markets of Oaxaca, Mexico. S Afr J Bot 130:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llauradó Maury G, Méndez Rodríguez D, Hendrix S, Escalona Arranz JC, Fung Boix Y, Pacheco AO, García Díaz J, Morris-Quevedo HJ, Ferrer Dubois A, Aleman EI, Beenaerts N, Méndez-Santos IE, Orberá Ratón T, Cos P, Cuypers A. 2020. Antioxidants in plants: a valorization potential emphasizing the need for the conservation of plant biodiversity in Cuba. Antioxidants 9:1048. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bontempo L, van Leeuwen KA, Paolini M, Holst Laursen K, Micheloni C, Prenzler PD, Ryan D, Camin F. 2020. Bulk and compound-specific stable isotope ratio analysis for authenticity testing of organically grown tomatoes. Food Chem 318:126426. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babalola OO, Enebe MC. 2020. Metagenomes of maize rhizosphere samples after different fertilization treatments at Molelwane Farm, located in North-West Province, South Africa. Microbiol Resour Announc 9:e00937-20. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00937-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox MP, Peterson DA, Biggs PJ. 2010. SolexaQA: at-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 11:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan BJ, Wong J, Heiner C, Oh S, Theriot CM, Gulati AS, McGill SK, Dougherty MK. 2019. High-throughput amplicon sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene with single-nucleotide resolution. Nucleic Acids Res 47:e103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer F, Paarmann D, D'Souza M, Olson R, Glass E, Kubal M, Paczian T, Rodriguez A, Stevens R, Wilke A, Wilkening J, Edwards R. 2008. The metagenomics RAST server: a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enagbonma BJ, Aremu BR, Babalola OO. 2019. Profiling the functional diversity of termite mound soil bacteria as revealed by shotgun sequencing. Genes 10:637. doi: 10.3390/genes10090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitra S, Rupek P, Richter DC, Urich T, Gilbert JA, Meyer F, Wilke A, Huson DH. 2011. Functional analysis of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes using SEED and KEGG. BMC Bioinformatics 12(Suppl 1):S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The metagenomes of rhizosphere soil sequence reads were submitted to the NCBI with BioProject accession number PRJNA766489 and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers SRX12366062, SRX12366063, and SRX12366064 (healthy), SRX12366065, SRX12366066, and SRX12366067 (diseased), and SRX12366068, SRX12366069, and SRX12366070 (bulk).