Abstract

Background

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a cognitive test that is commonly used as part of the evaluation for possible dementia.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) at various cut points for dementia in people aged 65 years and over in community and primary care settings who had not undergone prior testing for dementia.

Search methods

We searched the specialised register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), PsycINFO (OvidSP), LILACS (BIREME), ALOIS, BIOSIS previews (Thomson Reuters Web of Science), and Web of Science Core Collection, including the Science Citation Index and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Thomson Reuters Web of Science). We also searched specialised sources of diagnostic test accuracy studies and reviews: MEDION (Universities of Maastricht and Leuven, www.mediondatabase.nl), DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, via the Cochrane Library), HTA Database (Health Technology Assessment Database, via the Cochrane Library), and ARIF (University of Birmingham, UK, www.arif.bham.ac.uk). We attempted to locate possibly relevant but unpublished data by contacting researchers in this field. We first performed the searches in November 2012 and then fully updated them in May 2014. We did not apply any language or date restrictions to the electronic searches, and we did not use any methodological filters as a method to restrict the search overall.

Selection criteria

We included studies that compared the 11‐item (maximum score 30) MMSE test (at any cut point) in people who had not undergone prior testing versus a commonly accepted clinical reference standard for all‐cause dementia and subtypes (Alzheimer disease dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia). Clinical diagnosis included all‐cause (unspecified) dementia, as defined by any version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM); International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the Clinical Dementia Rating.

Data collection and analysis

At least three authors screened all citations.Two authors handled data extraction and quality assessment. We performed meta‐analysis using the hierarchical summary receiver‐operator curves (HSROC) method and the bivariate method.

Main results

We retrieved 24,310 citations after removal of duplicates. We reviewed the full text of 317 full‐text articles and finally included 70 records, referring to 48 studies, in our synthesis. We were able to perform meta‐analysis on 28 studies in the community setting (44 articles) and on 6 studies in primary care (8 articles), but we could not extract usable 2 x 2 data for the remaining 14 community studies, which we did not include in the meta‐analysis. All of the studies in the community were in asymptomatic people, whereas two of the six studies in primary care were conducted in people who had symptoms of possible dementia. We judged two studies to be at high risk of bias in the patient selection domain, three studies to be at high risk of bias in the index test domain and nine studies to be at high risk of bias regarding flow and timing. We assessed most studies as being applicable to the review question though we had concerns about selection of participants in six studies and target condition in one study.

The accuracy of the MMSE for diagnosing dementia was reported at 18 cut points in the community (MMSE score 10, 14‐30 inclusive) and 10 cut points in primary care (MMSE score 17‐26 inclusive). The total number of participants in studies included in the meta‐analyses ranged from 37 to 2727, median 314 (interquartile range (IQR) 160 to 647). In the community, the pooled accuracy at a cut point of 24 (15 studies) was sensitivity 0.85 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74 to 0.92), specificity 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.95); at a cut point of 25 (10 studies), sensitivity 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.93), specificity 0.82 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.92); and in seven studies that adjusted accuracy estimates for level of education, sensitivity 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00), specificity 0.70 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.85). There was insufficient data to evaluate the accuracy of the MMSE for diagnosing dementia subtypes.We could not estimate summary diagnostic accuracy in primary care due to insufficient data.

Authors' conclusions

The MMSE contributes to a diagnosis of dementia in low prevalence settings, but should not be used in isolation to confirm or exclude disease. We recommend that future work evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of tests in the context of the diagnostic pathway experienced by the patient and that investigators report how undergoing the MMSE changes patient‐relevant outcomes.

Plain language summary

Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in people aged over 65

The term 'dementia' covers a group of brain problems that cause gradual deterioration of brain function, thinking skills, and ability to perform everyday tasks (e.g. washing and dressing). People with dementia may also develop problems with their mental health (mood and emotions) and behaviour that are difficult for other people to manage or deal with. The process that causes dementia in the brain is often degenerative (due to brain damage over time). Subtypes of dementia include Alzheimer's disease dementia, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia.

We aimed to assess the accuracy of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is commonly used as part of the process when considering a diagnosis of dementia, according to the definition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The MMSE is a paper‐based test with a maximum score of 30, with lower scores indicating more severe cognitive problems. The cut point established for the MMSE defines 'normal' cognitive function and is usually set at 24, although theoretically it could fall anywhere from 1 to 30. We searched a wide range of resources and found 24,310 unique citations (hits). We reviewed the full text of 317 academic papers and finally included 70 articles, referring to 48 studies in our review. We included community studies (by which we mean people living in the community who have ) and primary care studies (by which we mean studies that had an office‐based first contact care with a non specialist clinician ‐ which would often be a GP).

Two of the studies had serious design weaknesses with regard to their methods for selecting participants, three with regard to the application of the test (MMSE), and nine with regard to the presentation of flow and timing. We were able to do a combined statistical analysis (meta‐analysis) on 28 studies in the community setting (44 articles) and 6 studies in primary care (8 articles), but we could not extract usable data for the remaining 14 community studies. Two of the six studies in primary care were conducted in people who had symptoms of possible dementia. We were able to calculate the summary diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE at three cut points in community‐based studies, but we didn't have enough data to do this in the primary care studies. A perfect test would have sensitivity (ability to identify anyone with dementia) of 1.0 (100%) and specificity (ability to identify people without dementia) of 1.0 (100%). For the MMSE, the summary accuracy at a cut point of 25 (10 studies) was sensitivity 0.87 and specificity 0.82. In seven studies that adjusted accuracy estimates for level of education, we found that the test had a sensitivity of 0.97 and specificity of 0.70. The summary accuracy at a cut point of 24 (15 studies) was sensitivity 0.85 and specificity 0.90. Based on these results, we would expect 85% of people with dementia to be correctly identified with the MMSE, while 15% would be wrongly classified as not having dementia; 90% of those tested would be correctly identified as not having dementia whilst 10% would be false positives and might be referred for further testing.

Our results support the use of the MMSE as part of the process for deciding whether or not someone has dementia, but the results of the test should be interpreted in broader context of the individual patient, such as their personality, behaviour and how they are managing at home and in daily life.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Summary of findings table.

| What is the accuracy of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) for diagnosing current dementia compared to clinical diagnosis of dementia? | ||||

|

Index test: Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) administered to the patient. We restricted inclusion to the original 30 item MMSE but did not restrict by language. Reference test: clinical diagnosis of dementia made using any recognised classification system Studies: cross‐sectional studies but not case‐control studies Limitations: there were too few studies to perform meta‐analysis at each cut point. We could not perform bivariate meta‐analysis on studies in primary care as there were too few. Population: adults resident in the community Setting: community | ||||

| Test | Summary accuracy (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies); median (IQR) | Dementia prevalence median (IQR) | Quality, Implications and Comments |

| MMSE at cut point 24 indicating normal | Sensitivity 0.85 (0.74, 0.92) specificity 0.90 (0.82, 0.95) |

10969 (15); 435 (272 to 737) |

7.4% (5.5% to 20.1%) | Studies were generally at low risk of bias (none were at high or unclear risk in more than 1 domain). In a group of 1000 people where 7 have dementia, 105 test positive, 6 of whom have dementia, and 895 test negative, 1 of whom has dementia. A large number of people would need to be evaluated further to identify the people with dementia. 1 person with dementia is 'missed'. |

| MMSE at cut point 25 indicating normal | Sensitivity 0.87 (0.78, 0.93) specificity 0.82 (0.65, 0.92) |

5894 (10) 316 (246 to 713) |

8.4% (6.0% to 19.0%) | 1 study was high risk for patient selection and unclear risk in 2 others (Winblad 2010). 1 other study was high risk in patient flow (Eefsting 1997). Otherwise studies were at low risk of bias. In a group of 1000 people where 8 have dementia, 186 test positive, 7 of whom have dementia, and 814 test negative, 1 of whom has dementia. Impact is similar to use of the 24 cut point but more people require further evaluation. |

| MMSE at cut point adjusted for education | Sensitivity 0.97 (0.83, 1.00) specificity 0.70 (0.50, 0.85) |

8442 (7) 294 (120 to 947) |

13.8% (2.4% to 27.4%) | 2 studies were at high risk of bias for patient flow (Jacinto 2011; Lam 2008), otherwise studies were at low or unclear risk of bias. In a group of 1000 people where 14 have dementia, 309 test positive, 14 of whom have dementia, 691 test negative, none of whom have dementia. Many people need to be further evaluated to identify the people who have dementia but everybody with dementia is identified. |

CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range.

Background

The protocol for this review was based on 'Neuropsychological tests for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias: a generic protocol for cross‐sectional and delayed‐verification studies' (Davis 2013a). This review forms part of a suite of reviews that address the accuracy of different neuropsychological tests for the cross‐sectional and delayed‐verification diagnosis of dementia in a range of populations, for example the the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and other dementia disorders (Davis 2013b), the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a general practice (primary care) setting (Quinn 2013); Mini‐Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a community setting (Fage 2013) and Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (Arevalo‐Rodriguez 2013).

This review addresses the use of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the cross‐sectional (current) diagnosis of Alzheimer's dementia and other dementias when used in the community and primary care, which are populations with a relatively low prevalence of dementia (approximately 7%; Matthews 2013) compared to memory clinics (around 60%; Banerjee 2007) and secondary or inpatient care. We included studies that examine the accuracy of the MMSE in previously unevaluated people with or without symptoms (akin to screening) because we aimed to address the accuracy of the MMSE when applied to the clinically relevant question of patients and clinicians, 'Does this person have dementia now?'. A separate review evaluates the accuracy of the MMSE for delayed verification of dementia diagnosis at some future point (addressing the question, 'Is the current level of cognition sufficiently poor that this person has a pre‐dementia syndrome?').

Target condition being diagnosed

Dementia is a progressive syndrome of global cognitive impairment that affects 6.5% of the UK population aged over 65 years (Matthews 2013). There is a significant global disease burden (36 million patients worldwide) that is predicted to increase to over 115 million by 2050, particularly in developing regions (Ferri 2005; Wimo 2010). Dementia encompasses a group of neurodegenerative disorders that are characterised by a progressive loss of cognitive function and ability to perform activities of daily living that can be accompanied by neuropsychiatric symptoms and challenging behaviours of varying type and severity. Prior ability is also important: someone could have a decline in their cognition over time and meet criteria for a diagnosis of dementia while still scoring above average on a cognitive test. The underlying pathology is usually degenerative, and subtypes of dementia include Alzheimer's disease dementia, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (pathological clusters of alpha‐synuclein protein; McKeith 2005), and frontotemporal dementia. There is considerable overlap in the clinical and pathological presentations; for example, Alzheimer's disease pathology may be present in people who have a clinical phenotype of vascular or Lewy body dementia, and vascular changes and Lewy bodies are common in the postmortem examination of brains of people with an Alzheimer's disease phenotype (CFAS 2001; Matthews 2009; Savva 2009). Some commentators have therefore advised against the use of neuropathological criteria as the gold standard for the diagnosis of dementia, including subtypes (Scheltens 2011).

The target condition in this review will be dementia or its subtypes (as defined by the reference standards described below), identified simultaneously with the administration of the index test.

Index test(s)

The Folstein Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) is an 11‐item assessment of cognitive function that assesses attention and orientation, memory, registration, recall, calculation, language and ability to draw a complex polygon (Folstein 1975). The MMSE is subject to copyright restrictions (De Silva 2010), and it takes around seven minutes to administer to a person with dementia and five minutes to a person with normal cognition (Borson 2000). Scores can range from 1 to 30; the conventional cut‐off is 24, with lower scores indicating increasing cognitive impairment (Mitchell 2009), although other cut‐off points have been suggested (Crum 1993; Kukull 1994). There is a wide spectrum in the severity of disease that people with dementia have, and this will affect the diagnostic properties of a diagnostic test such as the MMSE.

Clinical pathway

Dementia develops over several years, from a presumed initial asymptomatic period where pathological changes accumulate in the absence of clinical manifestations, through subtle impairments of recent memory or changes in personality or behaviour, until the disease has become more apparent, with multiple cognitive domains involved and a noticeable decline from previous abilities in planning and performing complex tasks.

Standard diagnostic practice

Standard diagnostic assessment relates to evaluating people for whom there is concern about possible dementia, particularly to exclude alternative diagnostic hypotheses, and it includes history, clinical examination (including neurological, mental state and cognitive examination) and an interview with a relative or other informant. Before diagnosing dementia, other physical and mental disorders that might be contributing to cognitive impairment, for example hypothyroidism or depression, should be identified and if possible treated. Most recent guidelines recommend a neuroradiological examination to scan the brain (Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)) to exclude structural causes for the clinical phenotype, for example a subdural haematoma (McKhann 2011; NICE 2006), but sometimes clinicians make the diagnosis on the history and presentation alone. Dementia diagnosis is defined by a deficit in more than two cognitive domains of sufficient degree to impair functional activities. These symptoms are usually progressive over a period of at least several months and should not be attributable to any other brain disorder. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD‐10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) general diagnostic criteria for dementia are detailed in Appendix 1 (APA 1994; WHO 1992).

Screening

Screening is the identification of unrecognised or asymptomatic disease by the administration of tests that can be applied quickly and are not intended to be diagnostic (Porta 2008). Recent UK health policy has encouraged opportunistic testing of older people attending primary care who have presented for reasons other than a memory complaint (Brunet 2012; Le Couteur 2013; Rasmussen 2013). GPs in the UK are encouraged to actively find people with dementia through routine annual questions in a Direct Enhanced Service (DOH recommendations; NICE 2013). In some cases, after further evaluation, the GP may then make a diagnosis of dementia, with or without a subtype (Ahmad 2010). Dementia screening is not recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (US Preventive Services 2003), but the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires an annual assessment of cognition for people who are enrolled in Medicare (Cordell 2013). The UK government has also encouraged case finding for dementia on acute admission to secondary care services (Dementia CQUIN).

Because people with dementia may not experience subjective memory problems, and a diagnosis of dementia often requires diagnostic evaluation by an experienced clinician, triage tests such as the MMSE are used in clinical practice to help rapidly identify people with a high likelihood of having normal cognition who do not require onward referral and investigation. Some investigations have blurred the distinction between the use of tests as a screening instrument in individuals without manifest disease and their use as clinical triage tools (Kamenski 2009).

Presentation to health services

In the UK people with memory problems usually present initially to their primary care practitioner, who may administer the MMSE to 'rule in' or confirm the possibility of dementia and potentially refer the patient to a specialist hospital memory clinic. Some people with dementia present much later in the disorder or follow a different pathway to diagnosis, for example, during an admission to general hospital for a physical illness. Diagnostic assessment pathways may vary in other countries, and a variety of clinicians including neurologists, psychiatrists and geriatricians, may make the diagnoses.

Role of the index test

Many countries in Europe and worldwide have been developing dementia strategies that emphasise the importance of accurate diagnosis to access appropriate health and social care services. Despite copyright restrictions, current experience is that the MMSE is still used extensively in clinical practice (Su 2014), including in the primary care setting, where clinicians may use it as either a screening test for dementia or as part of a more detailed evaluation of a person with suspected dementia. In some people, for example those who are particularly frail or unable to travel to a specialist clinic, the MMSE may be the only cognitive test used as part of the evaluation for possible dementia. A systematic evaluation of the diagnostic test accuracy of the instrument is needed to determine what confidence patients and clinicians can have in the clinical diagnosis of dementia based on the MMSE. A confirmed diagnosis of dementia is believed to offer opportunities for interventions, both social and medical, which may reduce the associated behavioural and psychiatric symptoms of dementia (Birks 2006; Clare 2003; McShane 2006), helping people with dementia, their families and potential caregivers to plan and avoid admissions to hospital or institutional care (Bourne 2007).

Prior tests

We anticipated the likelihood that no prior tests would have been performed before evaluating patients. In some settings, a two‐stage screening and assessment process takes place. Screening of people with suspected dementia usually requires a brief test of cognitive function, informant questionnaires or both, with a low score indicating a need for more in‐depth assessment (Boustani 2003). We anticipated that some studies carried out in the community and in primary care may have administered a very brief, high sensitivity instrument before applying the MMSE and investigating all of those who screened positive and a subsample of those who screened negative. In this eventuality, we planned to include the study and consider the prior test as a potential source of heterogeneity. However, no study used a test prior to the MMSE. Other tests are available to screen for dementia in primary care (Tsoi 2015), but we limited our review to the MMSE.

Rationale

Policy for dementia diagnosis is developing rapidly and has changed since the publication of the generic protocol for neuropsychological tests (Davis 2013a). There is a great need for a systematic appraisal of the diagnostic accuracy of neuropsychological tests, including the MMSE, in unselected (clinically unevaluated) populations.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) at various cut points for dementia in people aged 65 years and over in community and primary care settings who had not undergone prior testing for dementia.

Secondary objectives

To investigate the heterogeneity of test accuracy in the included studies. We anticipated that there would be many potential sources of heterogeneity in this review, which Davis 2013a covered fully. In this review we expected that the most important sources of heterogeneity would be the characteristics of the study populations, the way investigators used the MMSE and the reference standard employed.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The inclusion criteria for studies in this review were based on the generic protocol for neuropsychological tests in dementia (Davis 2013a). We reviewed the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE when used in people aged over 65 years in non‐specialist settings, including community settings (population‐based screening) and primary care settings (where people may be screened opportunistically or present to the primary care practitioner with memory problems). We included studies that examined the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE in people considered to have a memory problem (by patient, informant or clinician), as well as screening studies that examined the diagnostic accuracy in people regardless of a memory complaint (asymptomatic people). We analysed studies separately based on whether they were screening studies or not, as described in Investigations of heterogeneity. We included a diagnosis of dementia at any stage of disease (as long as the dementia was not previously identified by a specialist), as we considered that this pragmatic approach was most likely to be useful in informing current health policy and clinical practice. We did not examine the accuracy of MMSE for the diagnosis of pre‐clinical dementia (Sperling 2011), as this will be the subject of a separate review.

We included cross‐sectional studies that administered the index test and the reference standard(s) within a short time span (less than six months). We excluded case‐control studies because of the risk of bias (Whiting 2013). We did not include delayed verification studies, as these will be examined in a separate review, as described in the Background. We included studies where we anticipated 2 x 2 data would be available even if it was not reported in the original paper, and we contacted the authors to obtain it where necessary. Figure 1 outlines the process that we used for including articles in the review; further details are given in Selection of studies.

1.

Inclusion of studies

Participants

We included all participants who met the criteria for inclusion in community‐based or primary care described above. We defined primary care as non‐specialist, office‐based care with a first‐contact healthcare provider. We excluded studies where the MMSE was administered in a secondary care population, for example an emergency department, neurology ward or memory clinic.

We excluded studies of participants with previous or current substance abuse, central nervous system trauma (e.g. subdural haematoma), tumour or infection. Similarly, we excluded studies that recruited participants solely on the basis of disease state (for example; Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, brain injury, motor neurone disease) or residence (for example; residential home, nursing home, prison), as they are not applicable to the general population. We considered that studies that recruited participants conditional on these criteria would have a different prevalence of dementia than the general population. We included studies that recruited participants from retirement communities (defined as non‐nursing elderly person independent facilitated living communities but not residential homes where multiple elderly people from different families lived in a single building with resident carers), as we considered that residents in these settings are likely to be similar to the population in terms of cognition and co‐morbidities.

Our intention was that the findings of this review would have relevance to clinicians in community health and primary care, and be applicable to people with 'usual dementia' (Brayne 2012). We therefore excluded studies that investigated specific clinical groups. For example, participants with a family history of Alzheimer's dementia may be more readily diagnosed with dementia, perhaps leading to verification bias. On this basis, we excluded studies that exclusively investigated people with a known genetic predisposition from this review and studies specifically investigating early‐onset dementia.

Examples of applicable studies for this review include the following.

Participants selected regardless of suspicion of cognitive disorder. This would be an unselected cross‐sectional survey that administered the MMSE to all participants and then evaluated all participants (or a random sample), regardless of MMSE result, with a full assessment for the presence or absence of the target disorder. These studies are analogous to screening and could be conducted in:

the community;

people attending primary care, as defined in Participants section, though we considered these studies would be uncommon as they would involve screening people for cognitive disorder in a doctor's office waiting room, and the ethics of this are not established.

-

Participants selected as being suspected of having cognitive disorder. These studies could be conducted in:

the community, though we anticipated these studies would be uncommon, as many people who are suspected of having cognitive disorder will seek evaluation in a healthcare setting;

primary care.

Thus, we anticipated that we might find studies using the MMSE in two different ways (evaluating people with and without suspicion of cognitive disorder) in two different clinical settings (community, before seeking diagnostic evaluation; and primary care, at the point of seeking diagnostic evaluation). We expected the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE to differ between studies based in community and in primary care populations (and particularly in primary care participants selected on the basis of memory symptoms), and we planned to conduct separate analyses in these four potential study populations if appropriate.

Index tests

The index test is the 11‐item (maximum score 30) MMSE test (Folstein 1975). We recognised that other versions of the test exist (Grace 1995; Harrell 2000; Haubois 2012; Kabir 2000; Molloy 1991; Tschanz 2002), but we considered that these were best investigated in separate studies because of the substantial heterogeneity in the diagnostic test performance of these instruments. We also judged that including these index test variants would create an unfeasible workload for this review. However, we did not exclude studies on the basis of language, and we included studies that reported, for example, the diagnostic test accuracy of the Korean version of the 11‐item MMSE. Because education is associated with dementia (Fratiglioni 1991), some studies adjust the MMSE score for educational attainment (e.g. Liu 1996a).

Target conditions

The target condition was all‐cause dementia and any dementia subtype. We expected to find studies that focused on all‐cause dementia, Alzheimer disease dementia, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia. We planned to appraise findings separately if we could extract included studies examining dementias of differing aetiologies or differing stages.

Reference standards

In this review, the target condition was dementia or its subtypes as defined by the clinical reference standards described in Davis 2013a and outlined below. We excluded studies that used neuropathological criteria as the only reference standard, as this review seeks to determine a cross‐sectional diagnosis of dementia. Clinical diagnosis included all‐cause (unspecified) dementia, as defined by any version of the DSM, which when conducting the review was most recently the fourth edition (APA 1994); any version of ICD, which when conducting the review was most recently ICD, 10th edition (WHO 1992) (see Appendix 1); or the Clinical Dementia Rating (Morris 1993). In studies in which a reference standard refers to different criteria for dementia (for example McKhann 1984: unlikely, possible, probable, definite), we considered people as having the disease if they were classified as having either probable or definite dementia.

Alzheimer's dementia

The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA) have proposed the best ante‐mortem, clinical consensus 'reference standard' for Alzheimer's disease, defining three ante‐mortem groups: probable, possible, and unlikely Alzheimer's dementia (McKhann 1984). Newer criteria for Alzheimer's disease introduced in 2011 include the use of biomarkers (such as brain imaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis) to contribute to diagnostic categories (McKhann 2011). We planned to present any studies that used these (biomarker) criteria in a separate category and to test the findings in a sensitivity analysis.

Lewy body dementia

The reference standard for Lewy body dementia is the McKeith criteria or their revision (McKeith 1996; McKeith 2005).

Frontotemporal dementia

The reference standard for frontotemporal dementia is the Lund criteria (Lund 1994).

Vascular dementia

The reference standard for vascular dementia is the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINCDS‐AIREN) criteria (Román 1993).

We recognised that different iterations of reference standards over time may not be directly comparable (e.g. DSM‐III‐R versus DSM‐IV, ICD‐9 versus ICD‐10) and that the validity of diagnoses may vary with the degree or manner in which the criteria have been applied (e.g. individual clinician versus algorithm versus consensus determination). We collected data on the method and application of the reference standard, and we planned to examine this as a source of heterogeneity if we considered it to be a source of bias. Although it is unlikely that a specific reference standard might favour particular index tests, there is the more general issue of incorporation bias, in which the reference standard is applied with knowledge of the index test because neuropsychological deficits are integral to the definition of dementia. This is less problematic in cross‐sectional studies because the index test and the reference standard may be administered completely independently.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's specialised register (via the Cochrane Register of Studies); MEDLINE (OvidSP) (January 1946 to May 2014); EMBASE (OvidSP) (January 1972 to May 2014); BIOSIS previews (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) (January 1922 to May 2014); Web of Science Core Collection, including the Science Citation Index and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) (January 1945 to May 2014); PsycINFO (OvidSP) (January 1806 to May 2014) and LILACS (BIREME). See Appendix 2 for the search strategies. Where appropriate, we used controlled vocabulary such as MeSH terms (in MEDLINE) and EMTREE (in EMBASE) and other controlled vocabulary in other databases, as appropriate. We did not use search filters designed to retrieve diagnostic test accuracy studies (collections of terms aimed at reducing the number needed to screen by filtering out irrelevant records and retaining only those that are relevant) as a method to restrict the search overall, because available filters have not yet proved sensitive enough for systematic review searches (Beynon 2013; Whiting 2011). We did not apply any language restriction to the electronic searches; we used translation services as necessary during the screening stages. A single researcher with extensive experience in systematic reviews performed the searches. We first performed the searches on 21 November 2012 and then again on 20 May 2014.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all relevant papers for additional studies. We also searched:

Meta‐analyses van Diagnostisch Onderzoek (MEDION database) (www.mediondatabase.nl);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (www.cochranelibrary.com);

Health Technology Assessments Database (HTA Database) in The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com);

Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility (ARIF database) (www.arif.bham.ac.uk).

We attempted to contact authors where necessary to obtain details of unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Figure 1 shows a flowchart that we used when considering whether to include studies in the review.

The inclusion criteria were:

population is either community or primary care (see 'Types of studies');

reference standards as described above;

MMSE was used as an index test (alone or with other tests) and was administered to all study participants;

study design is cohort or nested case‐control.

Exclusion criteria were:

classic case‐control study design (subject to spectrum bias);

index test administered to only cases or controls, rather than to both groups (cannot calculate diagnostic accuracy).

We selected studies based on the title and abstract screening undertaken by a team of trained assessors. Two assessors independently reviewed all citations retrieved by the searches and classified them as relevant or not. Pairs of authors then assessed the full‐text papers of studies classified as possibly relevant, and we resolved any disagreements by discussion with a third, senior author. We show the process of study selection in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2.

2.

PRISMA Flow diagram of included studies.

Data extraction and management

Two senior authors simultaneously extracted data on study characteristics and 2 x 2 data directly into Review Manager (RevMan 2014). We resolved disagreements by reaching consensus with a third, senior author.

Assessment of methodological quality

We assessed the risk of bias of each study using the QUADAS‐2 tool in duplicate (Whiting 2011), as recommended by Cochrane (see Appendix 4 for QUADAS 2 statements and Appendix 5 for anchoring statements). The 'Assessment of methodological quality table' helps the reader to evaluate the strength of evidence to support the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We expected the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE to differ between studies based in community and in primary care settings (and particularly in primary care participants selected on the basis of memory symptoms), and we planned to conduct separate analyses in the four potential study populations (see Types of studies above). We also planned to conduct separate analyses as required for each subtype of dementia.

For all included studies, the data in the 2 x 2 tables (showing the binary test results cross‐classified with the binary reference standard) was used to calculate the sensitivities and specificities, with 95% confidence intervals. We present a summary of the included studies in Table 2 and Table 3. If studies reported more than one cut point, we presented the findings for all cut points reported.

1. Summary of included community studies.

| Study | Number of citationsa | Sample size | Number of people with dementia | Prevalence of dementia | Reference standard | Reported MMSE cut points indicating normal |

| Studies where 2 x 2 data was available | ||||||

| Aevarsson 2000 | 1 | 428 | 117 | 27.3% | DSM‐III | 24 |

| Baker 1993 | 1 | 55 | 1 | 1.8% | DSM‐III‐R | 24 |

| Burkart 2000 | 1 | 256 | 23 | 9.0% | DSM‐III‐R | 24, 25, 29 |

| Callahan 2002 | 1 | 344 | 15 | 4.6% | DSM‐III‐R | 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 |

| Correira 2001 | 1 | 109 | 15 | 13.8% | DSM‐IV | Adjusted for education |

| Eefsting 1997 | 1 | 2151 | 123 | 5.7% | DSM‐III‐R | 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 |

| Heun 1998 | 1 | 287 | 37 | 12.9% | DSM‐III‐R | 24, 25, 26 |

| Iavarone 2006 | 1 | 294 | 75 | 25.5% | DSM‐IV | Adjusted for education |

| Jacinto 2011 | 1 | 58 | 17 | 29.3% | DSM‐IV | Adjusted for education |

| Jeong 2004 | 1 | 235 | 46 | 19.6% | DSM‐IV | 19 |

| Kahle‐Wrobleski 2007 | 1 | 435 | 157 | 36.0% | DSM‐IV | 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 |

| Kathriarachchi 2005 | 1 | 37 | 17 | 38.0% | CDR | 17, 20, 23 |

| Kungsholmen Study 1992 | 7 | 668 | 314 | 47.0% | DSM‐III‐R | 24 |

| Macedo Montano 2005 | 1 | 156 | 34 | 21.8% | DSM‐IV‐R | 26 |

| Mackinnon 2003 | 1 | 646 | 36 | 5.6% | DSM‐III‐R | 24, 27 |

| Maki 2000 | 1 | 662 | 49 | 7.4% | DSM‐III‐R | 24 |

| MoVies Study 1993 | 5 | 1119 | 76 | 6.8% | DSM‐III‐R | 24, 25 |

| Lam 2008 | 1 | 5957 | 143 | 2.4% | DSM‐IV | Adjusted for education |

| Liu 1996a | 1 | 130 | 45 | 34.6% | DSM‐III | Adjusted for education |

| Pandav 2002 | 1 | 806 | 43 | 5.3% | DSM‐III‐R | 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 |

| PAQUID Study | 5 | 2730 | 101 | 3.7% | DSM‐III | 24 |

| Phantumchinda 1991 | 1 | 500 | 9 | 1.8% | DSM‐III | 10, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22 |

| Ramlall 2013 | 1 | 140 | 11 | 7.9% | DSM‐IV‐R | 24, 25 |

| Rosselli 2000 | 1 | 693 | 13 | 1.9% | DSM‐IV | Adjusted for education |

| Schultz‐Larsen 2007 | 1 | 242 | 69 | 28.5% | DSM‐IV | 24, 25, 26, 27 |

| Tang 1999 | 1 | 1201 | 29 | 2.4% | DSM‐III‐R | Adjusted for education |

| West Beijing Study 1989. | 2 | 99 | 10 | 10.1 | DSM‐III | 18 |

| Winblad 2010 | 1 | 114 | 24 | 21.1% | DSM‐IV | 25 |

| Studies where 2 x 2 data was not available | ||||||

| ADAMS Study 2007 | 3 | 509 | 129 | 25.3% | DSM‐IV | — |

| AMSTEL Study 1997 | 4 | 4123 | 261 | 6.3% | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Fichter 1995 | 1 | 402 | 85 | 21.2% | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Fillenbaum 1990 | 1 | 4164 | 26 | 0.6% | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Frank 1996 | 1 | 380 | 56 | 14.7% | NINCDS‐ADRDA | — |

| Helsinki Aging Study 1994b | 2 | 656 | 93 | 14.2% | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Keskinoglu 2009 | 1 | 490 | 63 | 12.9% | DSM‐III | — |

| Lee 2002 | 1 | 643 | 40 | 6.2% | DSM‐III | — |

| Li 2006 | 1 | 144 | 19 | 13.1% | DSM‐III | — |

| Lindesay 1997 | 1 | 297 | Not reported | Not reported | DSM‐III | — |

| Mingyuan 1998 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Rummans 1996 | 1 | 201 | 21 | 10.4% | DSM‐III‐R | — |

| Scazufca 2009 | 1 | 1933 | 84 | 4.3% | DSM‐IV | — |

| Wilder 1995 | 1 | 795 | Not reported | — | DSM‐III | — |

CDR: clinical dementia rating; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; NINCDS‐ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association. aRefers to the number of citations that we retrieved that refer to the same study and are listed in Included studies. bStudy reported sensitivity only and so could not be included in meta‐analysis in absence of paired data.

2. Summary of included primary care studies.

| Study | Number of citations a | Sample size | Number of people with dementia | Prevalence of dementia | Reference standard | Reported MMSE cut points indicating normal |

| Setting: asymptomatic primary care | ||||||

| Brodaty 2002 | 1 | 176 | 82 | 46.6% | DSM‐IV | 25 |

| Lavery 2007 | 1 | 313 | 28 | 8.9% | CDR | 23 |

| Lourenco 2006 | 1 | 303 | 78 | 25.7% | DSM‐IV | 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 |

| Pond 1994 | 1 | 367 | 57 | 15.5% | DSM‐III‐R | 24, 26 |

| Setting: symptomatic primary care | ||||||

| Carnero‐Pardo 2013 | 3 | 360 | 77 | 21.4% | DSM‐IV‐R | 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 |

| Cruz‐Orduna 2012 | 1 | 160 | 15 | 9.4% | DSM‐IV‐R | 19 |

CDR: clinical dementia rating; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. aRefers to the number of citations that we retrieved that refer to the same study and are listed in Included studies.

In our main analysis, we performed meta‐analyses on pairs of sensitivity and specificity, stratified by setting (community and primary care) using the HSROC method, using only one estimate from each study (Macaskill 2010). Where reported, this was the standard MMSE cut point of 23/24, where 24 indicates normal cognition, and where unreported, we used either the only estimate that was reported, or the best estimate (from the top lefthand corner of the study ROC curve, acknowledging that this may overestimate diagnostic accuracy in that study). We used Stata software (Stata) to perform the analysis and used the data to plot the summary ROC curve. We then used a bivariate random‐effects model approach based on pairs of sensitivity and specificity (Chu 2006; Macaskill 2010; Reitsma 2005) to analyse the diagnostic accuracy at specific cut points in community‐based studies, where there appeared to be consensus that these were commonly reported cut points (24 and 25 indicating normal and MMSE adjusted for education).

Investigations of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity in the first instance through visual examination of forest plots of sensitivities and specificities. We pre‐specified factors that would potentially contribute to heterogeneity and attempted to adjust for these in the meta‐analysis for average age of participants (in categories: 65 to 74 years, 75 to 84 years, 85 to 94 years, 95 years or more, unclear), sex, conduct of the test (in categories: specialist, trained non‐specialist, or unclear) and reference standard. We used likelihood ratio tests to compare the fit of candidate models when assessing the effect of a covariate on test performance (Macaskill 2010).

Sensitivity analyses

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to determine the effect of excluding studies deemed to be at high risk of bias. However, as studies were generally at low risk of bias – no study had more than two of four QUADAS‐2 items assessed as having a high risk of bias – we did not do this as we did not pre‐specify a point at which we would deem a study to be at overall 'high risk of bias'.

Assessment of reporting bias

Quantitative methods for exploring reporting bias are not well established for studies of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) (Bossuyt 2013)

Results

Results of the search

The search yielded 47,807 records, and 24,310 remained after removing duplicates (Figure 2). We reviewed the full text of 317 records (referring to 270 studies) and excluded 245 (referring to 222 studies), most commonly because of ineligible study design. We were unable to classify eight records because they were only available as abstracts and we could not obtain sufficient information about them despite attempting to contact authors (Gungen 2002; Jianbo 2013; Kornsey; Kvitting 2013; Orsi; Shaaban 2013; Upadhyaya 2010; Yu 2012). We found one ongoing study that had no results on diagnostic accuracy (Guiata 2012). We attempted to contact the authors of 17 articles, received replies from the authors of 10 and were able to include additional unpublished data from one study (Carnero‐Pardo 2013). We included 70 articles, referring to 48 studies, in our synthesis. Table 2 and Table 3 give details of the studies in the community and primary care, respectively. Of the 48 studies that we reviewed, we were able to perform meta‐analysis on 28 community‐based studies (44 articles) and 6 studies in primary care (8 articles). Of the 28 community studies that we included in the meta‐analysis, 7 reported accuracy estimates for level of education (referred to as 'education adjusted') and 21 reported accuracy estimates at various cut points. We could not include the remaining 14 community studies in the meta‐analysis because paired 2 x 2 data was not available despite contacting authors. However, we include them in this report for transparent reporting, because we believe 2 x 2 data should exist based on the study design and characteristics. Two of the six studies in primary care were conducted in symptomatic people, selected to the study on the basis of a reported concern about cognition(Carnero‐Pardo 2013; Cruz‐Orduna 2012), whereas the other four primary care studies and all of the community studies were in asymptomatic people, for whom reported cognitive difficulty was not a criterion for inclusion in the study. Studies reported the target condition as all‐cause dementia syndrome, so we could not analyse diagnostic accuracy by subtype.

In the meta‐analysis there were 12,110 participants in community studies and 1681 participants in primary care studies. For community‐based studies we were able to perform meta‐analysis using the bivariate method at cut points of 24 and 25 and in studies that adjusted accuracy estimates for level of education (referred to as 'education adjusted'). The Table 1 presents these results. For studies in primary care, we could not perform meta‐analysis using the bivariate method due to heterogeneity in the cut points reported, and so we cannot report a summary sensitivity and specificity. We include further details of the studies, including the design, sampling, reference standard and population, in the Characteristics of included studies.

We found one prior systematic review on the same topic, which included five studies that were excluded by our methods (Mitchell 2009). Table 4 presents the details of these studies. Cullen 2005 and Huppert 2005, two of the five studies that we excluded, used AGECAT as the reference standard (Copeland 1986), and the other three studies used CAMDEX (Roth 1986). Two of the studies used a cut point of 22 to determine normal cognition (Brayne 1989; Clarke 1991), one used a cut point of 23 (Huppert 2005), and two used a cut point of 24 (Cullen 2005; O'Connor 1989).

3. Papers included in Mitchell 2009 review but not in this review.

| Citation | Setting and sample | Prevalence of dementia | Index Test | Cut point indicating normal | Reference Standard | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reason for exclusion from this review |

| Belle 2000 |

MoVies Study 1993 Community age‐stratified random sample |

68 dementia and 1110 no dementia | MMSE | 27 | Short and Sweet Screening Instrument | 96% | 78% | No mention of MMSE in abstract and wrong reference standard in this paper but data from study (from another paper) included in our review |

| Brayne 1989 | Community Stratified random sample of 365 women aged 70‐79 years |

29 dementia 336 no dementia | MMSE | 22 | CAMDEX | 83% | 87% | No mention of MMSE in abstract and wrong reference standard |

| Clarke 1991 | Community Total sample of all people aged over 75 years on 1 GP list |

265 dementia, 150 no dementia | MMSE | 22 | CAMDEX | 77% | 71% | Wrong reference standard |

| Cullen 2005 | Community Sample of people aged over 65 years from GP lists |

44 dementia 1071 no dementia | MMSE | 24 | AGECAT | 91% | 87% | Wrong reference standard |

| Hooijer 1992 |

AMSTEL Study 1997 All elderly patients of 1 Amsterdam GP |

13 dementia 345 no dementia | MMSE | 24 | CAMDEX | 77% | 97% | Wrong reference standard in this paper but data from study (from another paper) included in our review |

| O'Connor 1989 | Community Total sample of all people aged over 75 on 5 GP lists |

196 dementia 285 no dementia | MMSE | 24 | CAMDEX | 86% | 92% | Wrong reference standard |

| Wind 1997 |

AMSTEL Study 1997 Age stratified sample of participating practices in AMSTEL |

114 dementia 419 no dementia | MMSE | 24 | AGECAT | 69% | 89% | Wrong reference standard in this paper but data from study (from another paper) included in our review |

| Huppert 2005 | Community MRC‐CFAS study Random, age‐stratified sampling of people aged over 65 years |

795 dementia 11,885 no dementia | MMSE | 23 | AGECAT | 88% | 92% | Wrong reference standard, abstract makes no mention of diagnostic accuracy and diagnostic accuracy terms such as sensitivity and specificity do not appear in the paper. |

Methodological quality of included studies

We used QUADAS‐2 to help determine the risk of bias for each study in order to determine the confidence that patients and clinicians can have in the results of each study (Appendix 4; Appendix 5). We summarise the main results below and in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

4.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

We judged Maki 2000 and Winblad 2010 to be at high risk of bias in the patient selection domain because Maki 2000 excluded people who lived alone and Winblad 2010 appeared to exclude people who were known to have dementia. We considered three studies to be at high risk of bias in the index test domain because it appeared that investigators did not specify the cut point before the analysis (Lindesay 1997; Lourenco 2006; Macedo Montano 2005). We identified nine studies that we considered to be at high risk of bias regarding flow and timing because we had concerns about partial verification of the index test: Eefsting 1997 administered the reference test to a proportion of each scoring band on the MMSE; Fillenbaum 1990 administered the reference standard to a sample of participants; Helsinki Aging Study 1994 only administered a reference standard to people who were diagnosed with possible dementia on the basis of an assessment by a GP; Jacinto 2011 did not describe the flow and timing; Kathriarachchi 2005, Lam 2008 and Macedo Montano 2005 partially verified the diagnosis with a sample of participants, but it was not clear how they selected the sample; Scazufca 2009 appeared to exclude people who were unable to answer items in the MMSE and said that 81 people were not approached but did not explain why. Finally, Maki 2000 administered the reference standard to a sample of people, but we could not reconcile the figures that were stated in the paper.

We assessed most studies as being applicable to the review question, though we had concerns that the selection of participants in six might reduce their applicability (Helsinki Aging Study 1994; Jacinto 2011; Li 2006; Maki 2000; Rosselli 2000; Winblad 2010). We had high concern that Li 2006 used a target condition (mild cognitive impairment and dementia) that was not applicable to our review question and were unable to include data on diagnostic accuracy from this study. As studies were generally at low risk of bias – no study had more than two of four QUADAS‐2 items that were assessed as high risk of bias – we did not exclude studies from the meta‐analysis based on the risk of bias as we did not pre‐specify a point at which we would deem a study to be at overall 'high risk of bias'.

Findings

Table 2 and Table 3 show that the accuracy of the MMSE for diagnosing dementia was reported at 18 cut points (MMSE score 10, 14 to 30 inclusive) in the community and 10 cut points (MMSE score 17 to 26 inclusive) in primary care studies. Table 1 presents the summary diagnostic accuracy in community studies: sensitivity 0.85 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74 to 0.92), specificity 0.90 (95% CI 0.8 to 0.95) at a cut point of 24 (15 studies); sensitivity 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.93), specificity 0.82 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.92) at a cut point of 25 (10 studies); and sensitivity 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00), specificity 0.70 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.85) when adjusted for education (7 studies). In primary care studies, each cut point was reported by a maximum of three studies, and we could not provide a summary of sensitivity and specificity.

Community studies

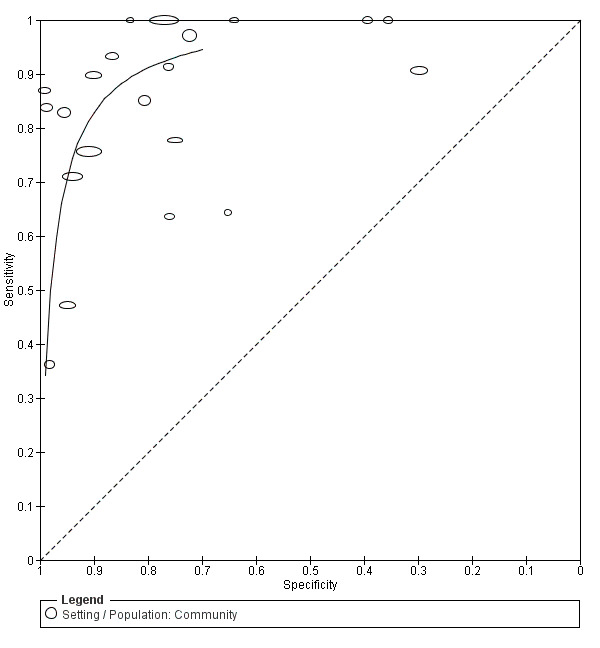

In community studies the accuracy of the MMSE for the diagnosis of dementia was available for 18 cut points (10, 14 to 30 inclusive) and also adjusted for education. At a cut point of 10, accuracy was sensitivity 0.11 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.48), specificity 0.95 (95% CI 0.93 to 0.97) (Phantumchinda 1991), and at a cut point of 30 accuracy was sensitivity 1.00 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.00), specificity 0.00 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.01) (Kahle‐Wrobleski 2007). Figure 5 presents the summary ROC curve for community studies in the main analysis, including all 21 studies that reported 2 x 2 data, and Figure 6 presents the linked forest plot.

5.

Summary ROC Plot of analysis 2 main community

6.

Forest plot of analysis 2 Main community

We were able to include seven community studies in the meta‐analysis of diagnostic accuracy in studies whose original investigators adjusted the MMSE for education. We present the summary ROC in Figure 7 and the forest plot in Figure 8. The pooled estimate for the diagnostic accuracy was sensitivity 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00), specificity 0.70 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.85). We were able to include 15 studies in the meta‐analysis of diagnostic accuracy at a cut point of 24; Figure 9 presents the summary ROC curve and Figure 10, the forest plot; the pooled estimate for the diagnostic accuracy was sensitivity 0.85 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.92), specificity 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.95). We were able to include 10 studies in the meta‐analysis of diagnostic accuracy at a cut point of 25; Figure 11 presents the summary ROC and Figure 12, the forest plot. The pooled estimate for the diagnostic accuracy was sensitivity 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.93), specificity 0.82 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.92).

7.

Summary ROC plot of analysis 3 community, education adjusted. The black filled dot indicates the summary point estimate of diagnostic accuracy, the smaller dotted bubble indicates the 95% confidence interval around the summary point (containing the 'true value' within that region 95% of the time on the basis of the available data) and the larger dashed bubble indicates the 95% prediction region (containing results from a new future study 95% of the time).

8.

Forest plot of analysis 3 MMSE community, education adjusted

9.

Summary ROC plot of analysis 4 MMSE at 24 normality (23/24). The black filled dot indicates the summary point estimate of diagnostic accuracy, the smaller dotted bubble indicates the 95% confidence interval around the summary point (containing the 'true value' within that region 95% of the time on the basis of the available data) and the larger dashed bubble indicates the 95% prediction region (containing results from a new future study 95% of the time).

10.

Forest plot of analysis 4 MMSE at 24 normality (23/24).

11.

Summary ROC plot of analysis 5 MMSE at 25 normality. The black filled dot indicates the summary point estimate of diagnostic accuracy, the smaller dotted bubble indicates the 95% confidence interval around the summary point (containing the 'true value' within that region 95% of the time on the basis of the available data) and the larger dashed bubble indicates the 95% prediction region (containing results from a new future study 95% of the time).

12.

Forest plot of analysis 5 MMSE at 25 normality.

Primary care studies

In symptomatic people the accuracy of the MMSE for the diagnosis of dementia was available for 9 cut points (17 to 25 inclusive). At a cut point of 19, accuracy was sensitivity 0.80 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.96), specificity 0.86 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.91) in Cruz‐Orduna 2012 and sensitivity 0.88 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.95), specificity 0.87 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.91) in Carnero‐Pardo 2013 .Carnero‐Pardo 2013 reported accuracy for cut points from 17 (sensitivity 0.70 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.80), specificity 0.93 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.96)), to 25 (sensitivity 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00), specificity 0.38 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.44)). At the traditional cut point of 24, the accuracy was sensitivity 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00), specificity 0.46 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.52).

In asymptomatic people the accuracy of the MMSE for the diagnosis of dementia was available for 9 cut points (18 to 26 inclusive). Lourenco 2006 reported that at a cut point of 18, accuracy was sensitivity 0.35 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.46), specificity 0.94 (95% CI 0.90 to 0.97), and at a cut point of 26 the accuracy was sensitivity 0.90 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.95), specificity 0.50 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.56). At the traditional cut point of 24, Lourenco 2006 found a sensitivity of 0.65 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.72) and specificity of 0.65 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.72), while Pond 1994 reported sensitivity 0.95 (95% CI 0.92 to 0.97) and specificity 0.95 (95% CI 0.92 to 0.97).

Figure 13 presents the summary ROC curve for primary care studies and Figure 14, the forest plot.

13.

Summary ROC plot of analysis 1 Main analysis primary care

14.

Forest plot of analysis 1 Main analysis primary care

Heterogeneity

We used additional models to explore potential heterogeneity in the diagnostic accuracy of the main analysis by age, sex, conduct and reference standard. Additionally we attempted to evaluate heterogeneity by education and mean MMSE score in the sample, but this was not possible because these data were poorly reported in the original studies. We found no evidence against the null hypothesis of no heterogeneity for age (P = 1.00 likelihood ratio (LR) Chi2(4) = − 9.49), sex (P = 1.00 LR Chi2(4) = − 20.68) or conduct (P = 0.0647 LR Chi2(4) = 8.85). There was some evidence against the null hypothesis of no heterogeneity by reference standard (P = 0.0342 LR Chi2(8) = 16.63).

Sensitivity analyses

We did not perform any sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In community studies of asymptomatic people, with a cut point of 24 indicating normal cognition, the MMSE had pooled diagnostic accuracy of sensitivity 0.85 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.92), specificity 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.95). The pooled diagnostic accuracy at a cut point of 25 was similar, whereas the MMSE adjusted for education was better for screening, at the cost of more false positives, with sensitivity 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00) and specificity 0.70 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.85). In primary care, a single study of symptomatic people reported that a cut point of 17 had higher specificity (0.93 95% CI 0.89 to 0.96) than a cut point of 24 (0.46 95% CI 0.40, 0.52), with some additional false negatives as the sensitivity fell from 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00) to 0.70 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.80) (Carnero‐Pardo 2013).

The risk of bias in the included studies is summarised in Figure 3. We generally had low concern about bias in the included studies. There were some differences between studies, but we found no evidence against the null hypothesis of no statistical heterogeneity by age, sex, or conduct of the index test. We found some evidence of heterogeneity by reference standard, but most of the studies used the clinical DSM definition for the target condition of all‐cause dementia. Some of the confidence intervals around the point estimates are wide, which indicates some uncertainty in our results because of the limitations of the underlying data.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

We used a comprehensive and sensitive search strategy that yielded substantially more results than a similar, earlier review that found only 775 articles and included a total of 21 studies in any setting (Mitchell 2009). We followed our pre‐specified peer‐reviewed protocol, which did not specify CAMDEX, CERAD or AGECAT as appropriate reference standards. Consequently we excluded studies that used these reference standards. We found few studies in primary care that used the references standards we specified and even fewer in participants selected on the basis of symptoms (symptomatic primary care). We found sufficient studies to perform meta‐analysis of test accuracy and to explore heterogeneity, but our evaluation was limited by poorly reported factors (education and mean MMSE score). On the other hand, assessing heterogeneity by factors that are not measured at the study level (e.g. education, severity of diagnosis or subtype diagnosis) is generally not recommended (Bossuyt 2013). We did not use a separate form (as we stated in the protocol), but we extracted data directly into RevMan after we set up the file using a set of pilot studies, as we pre‐specified (RevMan 2014). This was because we were concerned about introducing errors when copying data from an Access database into RevMan given the large number of studies. At least two authors, and usually three, performed data extraction and quality assessment, checking the accuracy of the extracted data in real time.

Applicability of findings to the review question

We consider that our findings are likely to be applicable to our review question. We had aimed to evaluate the strength of evidence for the accuracy of the MMSE for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias, but studies only reported all‐cause dementia, so we were not able to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy by subtype. Despite this, for clinicians and patients in primary care and community settings, the most important clinical question determining intervention and follow‐up is often, 'Does this person have a dementia now?', and our review addresses this.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In this section we present results using natural frequencies, but these do not take account of the confidence intervals and uncertainty in our results and so should be interpreted with caution.

If clinicians would like to use the MMSE in primary care to rule in a diagnosis of dementia in a symptomatic person, there is evidence from one study that a cut point of 17 to indicate normal cognition would have higher specificity than a traditional cut point of 24, with a slightly lower sensitivity: the median prevalence of dementia in primary care studies was 18.5%, so – rounding up to 20% for the sake of convenience – of 1000 people in this setting, with 200 expected to have dementia at a cut point of 17 indicating normal, clinicians could expect 196 to test positive, of whom 140 (71%) would truly have dementia; 804 would test negative, of whom 744 (93%) would not have dementia (Carnero‐Pardo 2013). If the test were being used to identify anybody who might have dementia regardless of concern about cognition, then there is evidence from seven community‐based studies that the accuracy of the MMSE adjusted for education has a higher sensitivity than when a cut point of 24 or 25 is used (based on the meta‐analytical estimates of 15 studies and 10 studies, respectively), although the specificity is lower and consequently there are more false positives, and this might mean unnecessary further evaluation for some people. Clinicians and patients can be confident that the MMSE is likely to be of some diagnostic value at cut points of 24, 25 and adjusted for education, though the uncertainty in the estimates does not allow us to confidently choose between these three approaches.

We consider that the evidence we present supports the use of the MMSE as part of a diagnostic evaluation for dementia, but it should not be used in isolation to confirm or exclude disease. Our review allowed for a diagnosis of dementia at any stage of disease; we did not explore heterogeneity by disease spectrum, and to do so would have been challenging and not recommended (Bossuyt 2013). However, we would advocate considering carefully how our results apply in the clinical context. When considering the studies that reported the highest cut point in asymptomatic people in the community and the lowest cut point in symptomatic people in primary care, then based on Burkart 2000 at a cut point of 29 indicating normal cognition in a sample of 1000 asymptomatic people in the community where 65 have dementia, we would expect that 367 people would have a normal result, of whom 2 would have dementia. Conversely, based on Carnero‐Pardo 2013, at a cut point of 17 indicating normal cognition in a sample of 1000 people in primary care, where 200 have dementia, we would expect that 196 test positive, of whom 56 would not have dementia. Thus, a diagnosis of dementia may still be possible even with high (normal) scores on MMSE, and people may not have dementia even with low (abnormal) MMSE scores. The use of the MMSE in the community will usually be followed up by further clinical evaluation of people who have abnormal scores.

Implications for research.

The MMSE is now protected by copyright and is likely to be used less in clinical practice in the future than it has been in the past, but these data may be useful for research studies. We were surprised to find so few studies in symptomatic people. Original study authors did not optimally report factors that might affect performance of the test.

Many of the studies that we included, particularly those in the community, are screening studies (see Clinical pathway). An ageing population is prompting policymakers to consider changes to the traditional clinical pathway, and in the future non‐specialist clinicians in primary care may be responsible for diagnosing straightforward cases of dementia (Barrett 2014). However, we found very few studies to inform policymaking in this area.

We recommend that future work evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of tests in the context of the diagnostic pathway experienced by the patient: that is, allowing for the presence or absence of subjective memory problems, symptoms and the view of caregivers and clinicians. We also suggest that in addition to testing accuracy alone,investigators report how undergoing the MMSE (or other similar cognitive test) changes outcomes that are relevant to patients and clinicians, such as time to diagnosis, initiation of treatment or care package, subsequent additional testing and place of care. We advocate the use of STARDEM reporting criteria to aid transparent reporting of future diagnostic test accuracy studies with dementia as the target condition (Noel‐Storr 2014).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 April 2016 | Amended | Error in plain language summary corrected |

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of original manuscripts who replied to correspondence and provided additional data.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Classification of dementia

World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases‐10

G1. Evidence of each of the following:

A decline in memory, which is most evident in the learning of new information, although in more severe cases, the recall of previously learned information also may be affected. The impairment applies to both verbal and nonverbal material. The decline should be objectively verified by obtaining a reliable history from an informant, supplemented, if possible, by neuropsychological tests or quantified cognitive assessments.

A decline in other cognitive abilities characterised by deterioration in judgement and thinking, such as planning and organising, and in the general processing of information. Evidence for this should be obtained when possible by interviewing an informant, supplemented, if possible, by neuropsychological tests or quantified objective assessments. Deterioration from a previously higher level of performance should be established.

G2. Preserved awareness of the environment during a period long enough to enable the unequivocal demonstration of G1. When episodes of delirium are superimposed, the diagnosis of dementia should be deferred.

G3. A decline in emotional control or motivation, or a change in social behaviour, manifest as at least one of the following.

Emotional liability.

Irritability.

Apathy.

Coarsening of social behaviour.

G4. For a confident clinical diagnosis, G1 should have been present for at least six months; if the period since the manifest onset is shorter, the diagnosis can only be tentative.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision

A. The development of multiple cognitive deficits manifested by both:

memory impairment (impaired ability to learn new information or to recall previously learned information;

one (or more) of the following cognitive disturbances.

Aphasia (language disturbance).

Apraxia (impaired ability to carry out motor activities despite intact motor function).

Agnosia (failure to recognise or identify objects despite intact sensory function).

Disturbance in executive functioning (i.e. planning, organizing, sequencing, abstracting).

B. Each of the cognitive deficits in Criteria A1 and A2

Causes significant impairment in social or occupational functioning.

Represents a significant decline from a previous level of functioning.

C. The deficits do not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium.

D. The disturbance is not better accounted for by another Axis I disorder (e.g. major depressive disorder, schizophrenia).

Appendix 2. Sources searched and search strategies

| Source | Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| 1. MEDLINE In‐process and other non‐indexed citations and MEDLINE 1950‐present (Ovid SP) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

1. MMSE*.ti,ab. 2. sMMSE.ti,ab. 3. Folstein*.ti,ab. 4. MiniMental.ti,ab. 5. "mini mental stat*".ti,ab. 6. or/1‐5 |

Nov 2012: 10048 May 2014: 1657 |

| 2. EMBASE 1980‐2012 November 16 (Ovid SP) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

1. MMSE*.ti,ab. 2. sMMSE.ti,ab. 3. Folstein*.ti,ab. 4. MiniMental.ti,ab. 5. "mini mental stat*".ti,ab. 6. 3MS.ti,ab. 7. *mini mental state examination/ 8. or/1‐7 9. dement*.ti,ab. 10. alzheimer*.ti,ab. 11. exp *dementia/ 12. "vascular cognitive impair*".ti,ab. 13. ("lewy bod*" or DLB or LBD).ti,ab. 14. (AD or VaD or FTLD or FTD or DLB or LDB).ti,ab. 15. delirium/ 16. deliri*.ti,ab. 17. or/9‐16 18. exp *mild cognitive impairment/ 19. "cognit* impair*".ti,ab. 20. (forgetful* or confused or confusion).ti,ab. 21. MCI.ti,ab. 22. ACMI.ti,ab. 23. ARCD.ti,ab. 24. SMC.ti,ab. 25. CIND.ti,ab. 26. BSF.ti,ab. 27. AAMI.ti,ab. 28. LCD.ti,ab. 29. QD.ti,ab. 30. AACD.ti,ab. 31. MNCD.ti,ab. 32. MCD.ti,ab. 33. (nMCI or aMCI or mMCI).ti,ab. 34. ("N‐MCI" or "A‐MCI" or "M‐MCI").ti,ab. 35. "Petersen criteria".ab. 36. ((CDR adj2 "0.5") or ("clinical dementia rating" adj3 "0.5")).ab. 37. "cognit* declin*".ti,ab. 38. "cognit* deficit*".ti,ab. 39. or/18‐38 40. 17 or 39 41. 8 and 40 |

Nov 2012: 11675 May 2014: 2774 |

| 3. PsycINFO 1806‐November week 2 2012 (Ovid SP) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

1. exp Dementia/ 2. exp Delirium/ 3. exp Huntingtons Disease/ 4. exp Kluver Bucy Syndrome/ 5. exp Wernickes Syndrome/ 6. exp Cognitive Impairment/ 7. dement*.mp. 8. alzheimer*.mp. 9. (lewy* adj2 bod*).mp. 10. deliri*.mp. 11. (chronic adj2 cerebrovascular).mp. 12. ("organic brain disease" or "organic brain syndrome").mp. 13. "supranuclear palsy".mp. 14. ("normal pressure hydrocephalus" and "shunt*").mp. 15. "benign senescent forgetfulness".mp. 16. (cerebr* adj2 deteriorat*).mp. 17. (cerebral* adj2 insufficient*).mp. 18. (pick* adj2 disease).mp. 19. (creutzfeldt or jcd or cjd).mp. 20. huntington*.mp. 21. binswanger*.mp. 22. korsako*.mp. 23. ("parkinson* disease dementia" or PDD or "parkinson* dementia").mp. 24. or/1‐23 25. "cognit* impair*".mp. 26. exp Cognitive Impairment/ 27. MCI.ti,ab. 28. ACMI.ti,ab. 29. ARCD.ti,ab. 30. SMC.ti,ab. 31. CIND.ti,ab. 32. BSF.ti,ab. 33. AAMI.ti,ab. 34. MD.ti,ab. 35. LCD.ti,ab. 36. QD.ti,ab. 37. AACD.ti,ab. 38. MNCD.ti,ab. 39. MCD.ti,ab. 40. ("N‐MCI" or "A‐MCI" or "M‐MCI").ti,ab. 41. ((cognit* or memory or cerebr* or mental*) adj3 (declin* or impair* or los* or deteriorat* or degenerat* or complain* or disturb* or disorder*)).ti,ab. 42. "preclinical AD".mp. 43. "pre‐clinical AD".mp. 44. ("preclinical alzheimer*" or "pre‐clinical alzheimer*").mp. 45. (aMCI or MCIa).ti,ab. 46. ("CDR 0.5" or "clinical dementia rating scale 0.5").ti,ab. 47. ("GDS 3" or "stage 3 GDS").ti,ab. 48. ("global deterioration scale" and "stage 3").mp. 49. "Benign senescent forgetfulness".ti,ab. 50. "mild neurocognit* disorder*".ti,ab. 51. (prodrom* adj2 dement*).ti,ab. 52. "age‐related symptom*".mp. 53. (episodic adj2 memory).mp. 54. ("pre‐clinical dementia" or "preclinical dementia").mp. 55. or/25‐54 56. 24 or 55 57. mini mental state examination/ 58. "mini mental stat*".ti,ab. 59. MiniMental.ti,ab. 60. Folstein*.ti,ab. 61. sMMSE.ti,ab. 62. MMSE*.ti,ab. 63. or/57‐62 64. 56 and 63 |

Nov 2012: 5740 May 2014: 728 |

| 4. Biosis previews 1926 to present (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

Topic=(MMSE OR sMMSE OR "mini mental stat*" OR folstein* OR MiniMental) AND Topic=(detect* OR diagnos* OR predict* OR identify OR validity OR validation OR validate OR utility OR sensitivity OR specificity OR screen* OR preval* OR incidence) AND Topic=(dement* OR alzheimer* OR cognitive OR cognition OR memory OR MCI OR petersen) Timespan=All Years. Databases=BIOSIS Previews. Lemmatization=On |

Nov 2012: 5713 May 2014: 609 |

| 5. Web of Science Core Collection, including the Science Citation Index and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

Topic=(MMSE OR sMMSE OR "mini mental stat*" OR folstein* OR MiniMental) AND Topic=(detect* OR diagnos* OR predict* OR identify OR validity OR validation OR validate OR utility OR sensitivity OR specificity OR screen* OR preval* OR incidence) AND Topic=(dement* OR alzheimer* OR cognitive OR cognition OR memory OR MCI OR petersen) Timespan=1975‐01‐01 ‐ 2012‐11‐20. Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH. Lemmatization=On |

Nov 2012: 7337 May 2014: 992 |

| 6. LILACS (BIREME) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |

MMSE OR folstein OR "mini mental stat$" OR sMMSE OR MiniMental [Words] | Nov 2012: 224 May 2014: 28 |

| 7. ALOIS (CDCIG specialized register searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies) Most recent search: 20 May 2014 |