Abstract

Background

Communities of color have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. We explored barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 vaccine uptake among African American, Latinx, and African immigrant communities in Washington, DC.

Methods

A total of 76 individuals participated in qualitative interviews and focus groups, and 208 individuals from communities of color participated in an online crowdsourcing contest.

Results

Findings documented a lack of sufficient, accurate information about COVID-19 vaccines and questions about the science. African American and African immigrant participants spoke about the deeply rooted historical underpinnings to their community’s vaccine hesitancy, citing the prior and ongoing mistreatment of people of color by the medical community. Latinx and African immigrant participants highlighted how limited accessibility played an important role in the slow uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in their communities. Connectedness and solidarity were found to be key assets that can be drawn upon through community-driven responses to address social-structural challenges to COVID-19 related vaccine uptake.

Conclusions

The historic and ongoing socio-economic context and realities of communities of color must be understood and respected to inform community-based health communication messaging to support vaccine equity for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

Keywords: COVID-19; Vaccine equity; Communities of color; Washington, DC

Introduction

Communities of color in the USA have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of vulnerability to infection, hospitalizations, and deaths. Black and Latinx populations are significantly more likely to acquire, get seriously ill, and die from COVID-19 compared with Whites in the USA [1–4], with age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates nearly 3 times that of Whites and COVID-19 death rates twice that of Whites for both Black and Latinx individuals [5]. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on people of color in the USA reflects long-standing and deeply rooted structural inequalities related to race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status that have resulted in dramatic health inequities [6–9].

Among the complex interplay of social and structural factors that drive elevated risk for COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths among Blacks and Latinxs is the disproportionate representation of racial and ethnic minorities in low-wage and essential services [10, 11]. Black and Latinx adults are overrepresented in high contact occupations in food, retail, services, transportation, and health industries that have been categorized as “essential.” [12] Beyond the working conditions that place them at greater risk of exposure and limit their ability to practice physical distancing, [13] many Blacks and Latinxs must continue working outside the home despite outbreaks in their communities due to economic necessity, increasing their risk of exposure [12]. Additional social and structural factors further exacerbating disparities include more crowded living conditions among racial and ethnic minorities, both by neighborhood and household assessment [14], implicit provider bias in the healthcare system [15, 16], and lower quality of COVID care by type of hospital and insurance status [17].

As COVID-19 vaccines became available, uptake and intention to vaccinate in Black and Latinx communities lagged [18]. Early examinations of what was driving vaccine hesitancy among communities of color identified mistrust of the safety and efficacy of the vaccines [19, 20]. However, there was also an important shift in the framing and examination of these lower vaccinations rates and what was driving them. The narrow focus on vaccine hesitancy was criticized for implicitly blaming communities of color for their lower vaccination rates and putting the onus on Black and Latinx individuals to develop better attitudes around vaccination [21]. This framing was recognized as problematic because it obscured the role of vaccine access as a major barrier to vaccination in these communities [17] and ignored the underlying social context, including historic and ongoing structural racism, contributing to reasons for reluctance to vaccinate among these populations [22].

Improving intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 and engagement with vaccine mandate initiatives as they begin to roll out will require targeted health communication strategies that effectively reach the subpopulations most likely to decline COVID-19 vaccination and those that specifically ameliorate the primary concerns driving their reluctancy [23, 24]. Given the multidimensional and unique reasons for vaccine hesitancy within different racial and ethnic groups, there have been calls for community-driven strategies to increase uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among Black and Latinx communities [25]. Research tailored to specific communities is needed to better understand how public health communication and messaging can better connect with the nuanced perspectives of key populations to address vaccine hesitancy, support equitable uptake and encourage participation in relevant vaccination requirements.

We set out to develop community-informed health messaging and vaccine uptake promotion approaches tailored to the context, questions, and concerns of communities informed by their own voices and experiences. We conducted a mixed-methods study to explore potential barriers and facilitators to the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines among communities of color in the Washington, DC, area. We focused on three specific communities of color with significant populations in Washington DC (i.e., African American, Latinx, and African immigrant including Ethiopian/Eritrean). While there is limited data on COVID-19 in relation to immigrant groups in the USA, research has found that monolingual Spanish speakers, potentially reflecting less time in the country among more recent immigrants, have an increased COVID-19 mortality rate [33]. We further focused our efforts on groups at higher risk of exposure to and acquisition of COVID-19 (i.e., healthcare workers, essential workers, and the elderly). The elderly have been shown to have an increased rate of COVID-19 related mortality across geographic settings [34]. The purpose of the study was to inform programmatic efforts to support and promote COVID-19 vaccine awareness and equitable access and uptake. This work was carried out collaboratively by the Washington, D.C. Department of Health (DC Health), researchers from the George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health (GWU), and three community-based organizations serving these specific communities in Washington, DC.

Methods

Study Design

We employed a mixed-methods approach [26] combining four sources of data collection for this study using a cross-sectional, exploratory design. We first conducted key informant interviews (KIIs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs), followed by focus groups discussions (FGDs) and then a community crowdsourcing contest. The KIIs were conducted with opinion leaders and program and policymakers, while the IDIs were conducted with a diverse group of community members from each key population. The IDIs and KIIs allowed us to understand potential concerns and motivators in-depth, and FGDs helped us assess the potential relevance and acceptability of health communication messages, materials, and media to promote awareness and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines. We used an innovative open contest (crowdsourcing) strategy [27–29] to allow community members more broadly to vote on their preferred vaccine awareness and uptake slogans and strategies. This community-engaged approach recognizes and values the insights of the focal population beyond expert opinions and centers campaign development around these insights [27, 29]. Through the crowdsourcing contest, the public voted on communication slogans and approaches that were best suited to their communities’ preferences, priorities, and needs.

Recruitment and Sample Overview

A total of 76 individuals were sampled from the African American, African immigrant (specifically Eritrean/Ethiopian and West African), and Latinx communities for the IDIs, KIIs, and 5 FGDs (40 IDIs and KIIs, 36 FGD participants) and 208 Washington, DC residents participated in the online crowdsourcing contest (197 participated in English and 11 participated in Spanish). Community-based organization (CBO) partners recruited individuals from their networks and aimed to include a diverse range of ages and balanced representation of men and women. CBO staff screened potential participants to confirm that they were members of relevant communities prior to their participation in the study. Participants were informed that the interviews and focus groups would take place over Zoom via video or phone-in and be recorded. Participants were not required to have their camera on in the interest of maintaining confidentiality in the focus groups and to avoid excluding individuals who did not have the ability to use video conferencing but could call in by phone. Oral informed consent was obtained from all interview and focus group participants prior to data collection and participants were compensated for their time with a $50 Visa gift card. Individuals were recruited to participate in the online crowdsourcing contest via social media promotion by DC Health, GWU, and CBO partners, via email listservs and at in-person vaccination events held throughout DC. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health and DC Health.

Characteristics of IDI, KII, and FGD participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of IDI, KII, and FGD sample (n = 76)

| African American (n = 35) | ||||||||

| In-depth interview community participants | n = 16 | % | Key informant interview participants | n = 3 | % | Focus group community participants | n = 16 | % |

| FGD #1 (n = 11) | FGD #2 (n = 5) | |||||||

| Gender | Gender | Gender | ||||||

| Male | 5 | 31% | Male | 2 | 67% | Male | 3.28% | 1.20% |

| Female | 11 | 69% | Female | 1 | 33% | Female | 8.72% | 4.80% |

| Age (median, range) | 52 | 19–92 | Age (median, range) | 70 | 59–81 | Age (median, range) | 37 (23–89) | 51 (38–57) |

| Latinx (n = 29) | ||||||||

| Community members | n = 10 | % | Key informants | n = 3 | % | Focus group participants | n = 16 | |

| FGD #1 (n = 8) | FGD #2 (n = 7) | |||||||

| Gender | Gender | Gender | ||||||

| Male | 5 | 50% | Male | 3 | 100% | Male | 2.25% | 1.14% |

| Female | 5 | 50% | Female | 0 | 0% | Female | 6.75% | 6.86% |

| Age (median, range) | 37 | (22, 47) | Age (median, range) | 33 | (31, 48) | Age (median, range) | 23 (19–30) | 44 (31–47) |

| African immigrant (n = 12) | ||||||||

| Community members | n = 5 | % | Key informants | n = 2 | % | Focus group participants | n = 5 | % |

| Gender | Gender | Gender | ||||||

| Male | 2 | 40% | Male | 0 | 0% | Male | 1 | 20% |

| Female | 3 | 60% | Female | 2 | 100% | Female | 4 | 80% |

| Age (median, range) | 41 | (29, 43) | Age (median, range) | 27 | (27, 28) | Age (median, range) | 51 | (38–54) |

Data Collection and Management

We developed semi-structured, in-depth interview guides for community members and key informant interviews containing a series of open-ended questions aimed at exploring vaccine awareness, decision-making, and uptake strategies. Inputs from CBO partners were incorporated, and guides were translated into Spanish for use with the Latinx community. Findings from IDIs and KIIs were incorporated into the focus group discussion guides subsequently developed for use with each community. The key slogans preferred by FGD participants were then used in the community crowdsourcing contest.

CBO staff members were trained in obtaining informed consent, ethics, and confidentiality in qualitative research data collection and qualitative interviewing techniques by the GWU research team and practiced in pilot sessions prior to the start of data collection. They then carried out all IDIs with community members from their respective communities, and in the next phase of the study, conducted the FGDs with community members. Qualitative researchers from the GWU research team conducted the KIIs. Interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish, depending on participant preference. All interviews and focus groups were voice recorded on Zoom and transcribed. Interviews lasted approximately 45 min, and FGDs lasted between 60 and 90 min. The study team assigned unique identifiers to all study participants, which were used to label forms and recordings. Interviews were completed between December 2020 and February 2021, FGDs were completed in March 2021, and the crowdsourcing contest ran from May to July 2021. Focus group participants were asked to participate in a design challenge to brainstorm slogan ideas using a digital interactive whiteboard, asked for their reactions to and thoughts on slogans generated in the IDIs, and asked general questions about vaccine access and acceptability in their communities. The online crowdsourcing contest was open to anyone 18 or older from a community of color in Washington DC. The most salient health promotion messages, in English and Spanish, respectively, related to COVID-19 vaccine uptake were identified in the qualitative work (KIIs/IDIs/FGDs) and were placed into a voting template where participants could vote on their 1st, 2nd and 3rd most preferred message.

Data Analysis

Two English–Spanish bilingual members of the GWU research team with extensive backgrounds in qualitative research conducted data analysis with ongoing inputs from the principal investigator. At the completion of each phase of the research, study findings were shared with CBO partners for validity checking to ensure results resonated with their understanding of the perceptions and ideas coming from their communities. All interview and focus group transcripts were analyzed in the language in which they were conducted to ensure the accuracy of nuanced descriptions, which can get lost in translation. Salient quotes included in the results of this paper were translated from Spanish to English. The GWU researchers developed an analytic summary for each interview and focus group completing a template pertaining to the research questions and key insights sought from the communities [30]. They then compiled a synthesis of key findings from each community developing a core narrative encapsulating commonalities between participants [30]. These core narratives pulled on the global themes across interviews per community, teasing out broader reflections on the community at large from key informant interviews and from personal perceptions of community members provided in in-depth interviews. Simple tabulations were utilized to document the most preferred health messages based on the crowdsourcing contest.

Results

Socio-structural Context and Constraints

All participants interviewed spoke about the intense impact of COVID-19 on their communities, underscoring how communities of color have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. While participants represented diverse communities, there were several commonalities in their perspectives related to the impact of COVID-19 in their communities, current social conditions in the USA, and hesitancy around the COVID-19 vaccines. These global themes included historical mistreatment of their communities, lack of trust in government, experiences of social and economic oppression, feelings of being “othered” and made to feel like they do not have the same rights to healthcare as others, and experiences of being essential workers and not having jobs that allow for work from home during the pandemic.

Government and Medical Mistrust

A prominent theme among African American participants was distrust in government and the medical establishment at large based on historical mistreatment of Black communities in clinical trials. One African American key informant described its impact on perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine as follows:

Vaccine hesitancy is deep and it’s real. You’d like to, but you can’t erase the memory of what happened that easily…We started talking immediately about vaccine hesitancy, we understand how our community responds to vaccines based on the Tuskegee experiment, based on Henrietta Lacks, based on our whole history of how, in many instances, we have not been fairly dealt with and how that lingers with us and it will. (African American key informant, female, age 70)

Another key informant from the African American community described his own initial skepticism, which aligned with what he was seeing around him in his community:

At first, I was skeptical, and reflected what the African American community has and is feeling – we don’t trust government, so much that the government that either was a part of or was negligent of…so trust of government and trust of White people is a major factor. There have been several advances in society, what happened at Tuskegee could never happen again. Too many good people and African Americans in science to let that happen again would be very difficult for that to happen again. Given it’s not 1930; we need to shed our fear in that paranoia and follow the science. As I followed the science, I became more comfortable with the idea of taking the vaccine. (African American key informant, male, age 59)

This participant’s acknowledgment of differences in the current context in which the COVID-19 vaccine was developed from the previous mistreatment of his community was echoed by other African American participants. Other participants noted the importance of ensuring members of their community were aware of the involvement of Black scientists in the development and approval of the COVID-19 vaccines to garner more trust and acceptance.

Racial and Economic Injustice

As participants across the different communities described current social conditions of their own lived experiences and those around them, there were several commonalities to the context that shaped perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine. These included systemic racism, economic vulnerability, social oppression, and immigration status. For example, one African American focus group participant stated:

Certain populations of people don’t give a damn about a COVID shot because their everyday walk is a pandemic. So the message is going to be lost because they can’t receive it. They’re still trying to heal from wounds that happened before last year [referring to ongoing racial injustices experienced by people of color prior to the pandemic]. (African American focus group participant, female)

A key informant from the Ethiopian community described how the Black Lives Matter movement and increasing consciousness of the historical and ongoing injustices against Black people in the USA has affected her community’s perceptions of their own sense of safety and vulnerability. She said:

There's definitely a sense of like what if in the past the American medical system has experimented with its Black people and we are Black immigrants that are coming here. We also have to be careful they're not experimenting with us. I think that's the other part of that hesitancy to what I'm hearing more and more now from people. So there's the mistrust like whoa, this medical system has done people wrong before, and we look, we're pretty similar looking to those people. (Ethiopian key informant, female, age 27)

A Latinx interview participant described concerns about economic and racial justice in vaccine distribution as follows:

I appreciate the vaccine; I’m happy many people will receive it. My concern is that many rich people will receive it first. Before the people who are working in the stores, before the people who work where they have a lot of contact with other people, and these are many Latino people and many African Americans, many poor people, many people who are right now affected by it [COVID-19]. The rich people have more access to services, unfortunately, this is how it is. (Latinx interview participant, female, age 59)

Other Latinx participants spoke candidly about the additional stress and challenge of being undocumented and the “otherness” they experience as a result, particularly during the pandemic given their inability to access formal assistance due to immigration status. As one key informant said, “[Undocumented families] they're the ones that are being infected at a higher rate, they’re the ones that are being evicted. They're the ones that are being rounded up by ICE” (Latinx key informant, male, age 33).

Essential Workers

Ethiopian participants spoke about feeling conflicted because, while they may have understood they were putting themselves at risk through their work, they felt stuck as they had no other way to provide for their families if they did not continue working through the pandemic. One participant described it as follows:

Working is a huge thing in our community because that’s how people are surviving – they don’t have the luxury of working from home, a lot of them are essential workers or they feed their kids by driving an Uber or a taxi so they didn’t have the opportunities to be able to work from home or try to be safe. A lot of the times they had to put themselves at risk to put food on the table. So I see that a lot of people who felt very conflicted and didn’t know what they were supposed to do. (Eritrean interview participant, female, age 28)

Participants from the Latinx community also described how, as essential workers, they have been a key group affected by the pandemic due to exposure through their work. As one participant described:

I think that we [Latinos] have been the ones who have been showing up the most to our work areas. Because, for example, those who are White, they are working and they are earning their money, their paycheck, but they are doing it from home...We cannot miss a day because there we have to be disinfecting, cleaning, providing maintenance, and we are the ones who have had to put our face in front of this [pandemic]. (Latinx interview participant, female, age 36)

Leveraging Community Assets to Build a Trusted Response

Within the context of these socio-structural constraints, participants also discussed community assets and how leveraging their community’s strengths could help build a trusted response. Within the African American community, participants focused on resiliency. Ethiopian participants spoke about the tight-knit nature of their community. The Latinx participants focused on the solidarity they feel within their community. Participants’ perspectives on dissemination channels, messengers, and the content of the messaging around COVID-19 vaccines were directly tied to both the socio-structural context and constraints they experienced as well as these community assets.

African American participants spoke about pulling on resilience and community support through the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. A key informant described the history and evolution of this community asset as follows:

There’s a level of resilience in communities, African American, and other communities of color, which comes ironically from years of negligence due to racism and White supremacy – we’ve had to be resilient even though it hasn’t led to a thriving community, we’ve had to find ways to get around and provide, even though the services weren’t always there – sharing resources about services, informing about where to get services, etc. (African American key informant, male, age 59)

Ethiopian/Eritrean participants stressed the tight-knit nature of the community and the strong levels of trust they feel with neighbors, friends, family, and church congregations within their community. One key informant underscored that this influences who people will listen to and follow guidance from saying, “The community is extremely tight-knit. We’re more likely to heed advice from within the community. Trusted leaders have a key role in delivering accurate information” (Eritrean key informant, female, age 28).

Among Latinx participants, a salient theme was solidarity and the community coming together to help one another. Participants described this as including everything from neighbors helping those infected with COVID-19 and holding food drives to community-based organizations providing rent assistance. As one interview participant described:

It’s been a very good response within our community for those of us who have been infected, we are helping those we can, those who I have asked to support or help someone else, no one has ever refused, they have always lent a hand. (Latinx interview participant, male, age 47)

Participants across groups spoke with pride and gratitude about their community’s response to supporting one another through the pandemic. Many individuals highlighted how these community-specific assets provided them, or those they know, with needed support when facing the greatest challenges of the pandemic.

Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance

Questioning the Science

On a backdrop of deep-seated mistrust of government, a key barrier to vaccine acceptance was skepticism of the safety and science behind the development of the vaccines. Members of all communities stressed that skepticism of the vaccine was largely rooted in how quickly it was produced and the perception that it was done under the pressure of having to produce something quickly. The sentiment that development was rushed, and the vaccine was not sufficiently tested came up with a number of participants, and several linked this concern to fear that there will be long-term effects of the vaccines that are not yet known. As one Latinx participant said:

I never thought it could be so fast to find a vaccine for the coronavirus. There are so many illnesses for which years and years pass without them finding a vaccine for it. This is why I don’t trust it. They got it out on the market so fast. As I see it, they didn’t have a lot of time to test it. This is the distrust I have in the vaccine. (Latinx interview participant, male, age 47)

An Eritrean participant described his perspective as follows:

I was a little weary of the vaccine because of the matter of time they needed to get this thing out, the pressure that people were put under to get this vaccine out – I was just a little weary and I didn’t know if I was going to take the vaccine. (Eritrean interview participant, male, age 41)

Many participants argued that addressing this fear and skepticism would be an effective angle from which to approach vaccine messaging. Participants suggested specifically explaining how it was possible that it was developed so quickly when vaccines are not available for other viruses that have been around far longer than COVID-19.

Lack of Information

Participants from all communities stressed that a sheer lack of information and misinformation was holding their communities back from vaccine acceptance. Many African American participants described the need for more information about the vaccines and the vaccine trials. One participant stated, “More information on the vaccine, in general – tell me how it was made, what’s in it” (African American interview participant, male, age 26). Another individual said:

If I had more information about the trials, I don’t think I’d be so hesitant. I want education. If someone could provide me with some sort of detailed packet, education, even if it’s an app “this is the latest on the vaccine”, “this is the evidence that’s here” just so I could feel comfortable with what the possibilities could be. (African American interview participant, female, age 36)

Several participants from across the different communities detailed long lists of the information they felt they needed and were not being provided with, including what is in the vaccine, what the side effects are, where it came from, how it works in the body, where they could get it, and information about vaccine dosing and schedule. Many participants suggested a hotline model where individuals could call a phone number to get their questions answered.

Latinx community members asserted that their community was in need of COVID-19 vaccine information that was complete, reliable, and from trusted sources, describing that lack of information as a key reason the Latinx community is not ready for COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Lack of information was also linked to not trusting the vaccine, as described here by one Latinx key informant:

I will be honest. I have heard that it [the vaccine] is not good. That some have gotten side effects and get it [COVID-19] worse, they get the disease with more intensity. And from others, I have heard that the injection is to help kill the population. (Latinx interview participant, female, age 38)

Expressing a common concern about what was in the vaccine; other Latinx participants more broadly stated, “People need to know what they are putting in their bodies.” (Latinx interview participant, female, age 37) and another commented: “We all want to be protected [from COVID-19]. But at the same time, we don’t really know what they will be putting in us [through the vaccine]” (Latinx interview participant, female, age 44).

Participants across the communities described several ways in which elements of governmental distrust clouded community views of the COVID-19 vaccines. Within the Ethiopian/Eritrean community, participants cited a general mistrust of the US medical system as a major barrier to vaccine acceptance. One key informant described it as follows:

There is a huge mistrust of the medical community and I can understand why. The U.S. medical system is very different from what’s practiced at home. The idea of insurance, deductibles, premiums – those things all seems like a money-making scheme to people. Similarly, with the COVID vaccine, I am hearing hesitations like ‘what if this is something the doctors are doing as another way to make money? What if it’s going to cost me money but it won’t actually work? How can we trust something that’s so new?’ (Ethiopian key informant, female, age 27)

Others in the Ethiopian/Eritrean community noted that the vaccine being free raises skepticism for some people in the community. Similarly, Latinx participants simultaneously expressed it should be made clear to their community that the vaccines were free but also that given underlying mistrust, this would raise skepticism. One Latinx key informant reported that many community members were saying, “How could you trust a vaccine that you don’t have to pay for, and why do you think they are giving it to you for free?” (Latinx key informant, male, age 33). However, as in the Ethiopian community, the predominant concern was ensuring that Latinx community members without health insurance and living under financial constraints would not see cost as a barrier to getting vaccinated.

Trusted Channels

Grassroots Mobilizing

Across individual interviews and FGDs, there was a strong emphasis placed on the importance of grassroots mobilizing to reach communities on the streets of their own neighborhoods. Several African American participants spoke about strategies such as canvassing a community, as is done during voter registration drives and by political candidates, to provide each household with literature and answer questions about the vaccine. Others stressed the importance of mobile outreach, including vans equipped with medical staff administering vaccines and providing information to community members parked in front of local grocery stores and churches. As one African American FGD participant described it:

Old-school door-to-door community outreach…with masks…to build rapport with people rather than just shoving information at them…This is personal, it requires a personal approach. (African American focus group participant, female)

Other members of this same focus group supported this idea, adding that the most effective approach to reaching the community is to “set up on street corners with signs so people can come to ask questions” and to “be available in the neighborhood, walk around engaging people, give out information and answer questions.” Citing the historical and cultural importance of this, one group member articulated, “As a community, that’s how we operate” (African American focus group participant, female).

Vaccine Drives with Healthcare Providers from the Community

Ethiopian/Eritrean participants suggested organizing COVID-19 vaccine drives, following the model of flu drives, with all Ethiopian/Eritrean healthcare workers to help ensure the trust of medical personnel administering the shots. Similarly, a West African key informant proposed using the Cameroonian Nurses Association and Nigerian Doctors Association as the medical providers administering the shots to help build trust stating, “working with the community, you can get more things done.” (West African key informant, female, age 68).

Participants from the Latinx community also stressed the need to foster direct conversations between Latinx healthcare workers and people throughout Latinx neighborhoods. Focus group participants suggested having tables in the community where Latinx people can go to speak with someone in Spanish, specifically focusing on ensuring the diversity of the community is reflected and community members can approach individuals who they are able to relate to linguistically and culturally.

The idea of reaching people in their own communities was salient across participants from all groups. Latinx participants stressed the importance of not just delivering information in person but also ensuring vaccine coverage in their neighborhoods, particularly given rigid work schedules and jobs with little flexibility to be able to go somewhere to get vaccinated. As one Latinx key informant said, “People want convenience and for things to be easy” (Latinx key informant, male, age 31). For many, this sentiment also applied to needing to make vaccine registration more accessible for the members of their communities for whom computer literacy was not high, particularly older populations. As a West African key informant said,

Expecting people to ‘log in’ to schedule appointments is not reasonable – you’ve lost them at ‘login’. Give them a number to call. They will call, and they will keep calling until they get through to make an appointment. (West African key informant, female, age 68)

Nearly all participants spoke about the importance of using diverse channels of distribution to reach different subgroups within their communities. For example, using social media and smartphone applications to reach younger generations while pamphlets sent by postal mail, TV news and radio, flyers in grocery stores, pharmacies, and apartment buildings, and church outreach would reach older generations. Other popular ideas included text messages directing people to a phone number where they could ask questions and using informational YouTube videos that could be shared within the community to debunk myths circulating about the vaccine and explain how the vaccine works once inside the body.

Trusted Messengers

Community Leaders

When thinking about effective messengers for vaccine information, participants focused on local religious, political, and civic leaders whom people in their community feel they can trust. As one key informant from the Latinx community described them, “people working for the community” (Latinx key informant, male, age 31), specifically local trusted CBOs. Many Ethiopian/Eritrean participants stressed the importance of recognizing that their community is not homogenous. Particularly, given current political divisions and tumult in Ethiopia, they urged that it was critical to understand the community is not one; there are differences in language and culture that must be acknowledged to ensure communicating in the right way. Echoing the sentiment expressed by many Ethiopian and Eritrean participants about the diversity of the community, one key informant described the role of community leaders in reaching each of the subgroups:

Habesha communities are a close-knit group of people, communication between leaders and people is the best way to get messaging out. Each [Amhara, Oromo, Tigray] has their own leaders and their own means of communication…need to use appropriate social media platform and TV and media channels they have for reaching their communities. (Eritrean KII, female, age 28)

Religious Leaders and Houses of Worship

The church, other houses of worship, and faith groups repeatedly came up as important channels and messengers of vaccine information from participants across the communities represented in the sample, particularly among African Americans and African immigrants. As one African American key informant said, “there is no more formidable messaging that you can do beyond communications through the faith community, the church. However people feel about the church, however they care about the church, it raises their attention to another level” (African American key informant, male, age 81). He went on to say:

Train, educate, and convince pastors. Equip them with the knowledge and allow them to do the talking. It’s worth it to invest in the education of the clergy persons with the idea of him making a responsible decision and presentation to his people. They will believe it better, and so will he. (African American key informant, male, age 81)

Participants suggested mobilizing community partnerships through local churches, such as using church space for vaccination sites and church vans for bringing people to sites to get vaccinated. Other participants spoke about the importance of online sermons during COVID-19 lockdowns frequently viewed on YouTube by congregation members and the opportunity this presented for informational videos on the vaccines and guest speakers hosted by pastors at the end of services to reach individuals watching at home with key information. As an Ethiopian key informant simply stated, “Church leaders have a huge influence on the community.” (Eritrean key informant, female, age 28).

Medical Professionals from the Community

Considering trusted messengers within their own communities, many participants expressed a strong interest in medical professionals from their communities. Participants discussed wanting to hear medical professionals they could trust speaking in layman’s terms about the vaccine. African American participants, in particular, highlighted the importance of hearing from Black doctors. Focus group participants discussed the effectiveness of a video they had seen of Black doctors answering common questions about the vaccines highlighting the importance of feeling that they were not trying to make you take it but rather that they were available to answer questions. Among younger participants, medical professionals were not as often seen as effective messengers, as noted by one younger African American participant who said, “A person with a medical background could be good too, but people in my age group don’t always listen to them.” (African American interview participant, female, 19 years old).

Peers, Neighbors, Friends, Family/ “Representation Matters”

Building on the importance of individuals perceived as trusted within and by their own communities, a prominent and salient point made by numerous participants from each community was that representation matters in delivering vaccine messaging. African American participants stressed that people need to see individuals in vaccine messaging who look like them and with whom they can relate to getting the vaccine and talking about the vaccine. As one participant described: “If I’m a Black man from the inner city, I don’t want to hear some yogi person telling me that it’s safe” (African American interview participant, male, age 27).

A West African key informant echoed this sentiment saying, “People who look like them saying ‘I’ve received the vaccine; you can talk to me about it’’” (West African key informant, female, age 68). Ethiopian/Eritrean participants also felt it would be effective for people to see someone who looks like them and is of their age group talking about the vaccine and their experience getting vaccinated. Participants went on to stress that in order for it not to become politicized in this particularly sensitive time given current political dynamics in Ethiopia, such efforts must reflect truly multi-ethnic, bipartisan campaigns encouraging the community to vaccinate. A critical component of this, which several participants stressed, is the need to have materials in the three main languages spoken in the community: Amharic, Oromo, and Tigrinya.

Latinx participants focused on the need for inclusivity of all Latinx communities living in Washington, DC urging that people depicted in campaigns should represent the diversity of people from the Latinx community and highlight the different accents heard among the Spanish spoken throughout the city. Participants stressed that making information culturally and linguistically appropriate included ensuring materials are disseminated in Spanish, English, and Spanglish to appeal to different age groups within the community. One participant spoke about the role of stigma in the language being a barrier to vaccine information within the Latinx community saying that when information is not available in Spanish, “we even feel shame to ask questions, because people may think we are ignorant” (Latinx interview participant, male, age 22).

Interestingly, there were some cultural distinctions by the community in terms of how information is passed along. Some Ethiopian participants spoke of the potential effectiveness of a “respect your elders” approach of having older family members educate the younger generations because they are seen as wiser and more knowledgeable. Among Latinx participants, some individuals spoke about the opportunity for younger people to educate older adults in their community, potentially overcoming language, cultural, or technological barriers to reaching the elderly in their community. As one Latinx participant described, “Many young people could help older adults. It may be worthwhile to educate young people and have them educate their parents, their uncles and aunts” (Latinx interview participant, male, age 22).

Trusted Content

Given the rich and complex context of the perspectives and views within their communities on the COVID-19 vaccines, participants developed the types of messaging, and specific slogans they felt would be particularly effective in encouraging vaccine uptake within their communities.

During in-depth interviews, participants from the African American community proposed messaging around two main approaches: stressing the severity of COVID-19 infections and getting to the other side of the pandemic (slogans proposed by participants for each are shown in Table 2). In focus group discussions, these messages were largely considered appropriate, but the slogans were revised by the participants, resulting in the most popular/well-received being added to the final slogans included in the crowdsourcing contest (see Table 2). Some of the criticism focus group participants had of the slogans proposed by interview participants included dislike of fear tactics and strongly worded and/or overly directive messaging. Instead, there was a preference for “feel-good” messaging and praise for more universal messaging like “getting our lives back to normal,” but urged caution about generalizing about a singular way of life when there are many different ways of life within the community. Participants also stressed that effective messaging should convey the element of choice, specifically, that no one is being forced, such that you can choose to vaccinate so as to not further push people away by coming off too aggressively.

Table 2.

Suggested health messaging focus and slogans generated through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions

| Messaging focus | Community | Slogans from IDIs and FGDs |

|---|---|---|

| Financial aspects | Ethiopian/Eritrean | “It’s free health care, which is rare in America, that will save your life.” (IDI) |

| “Protect your family. Protect your business. Vaccinate.” (IDI) | ||

| Latinx | “I got my vaccine, and you, what are you waiting for? ITS FREE!” (¿Yo recibí mi vacuna, y tú que esperas? ¡ES GRATIS!) | |

| Getting to the other side of the pandemic | African American | WINNING SLOGAN: “Vaccinate so we can celebrate!” (FGD) |

| “We are on our way!” (FGD) | ||

| “Vax to normal.” (FGD) | ||

| “In this time of social isolation, take the vaccine so your life can change again.” (IDI) | ||

| “This is the safeguard of our lives, our way of life.” (IDIs) | ||

| Latinx | “Let’s get vaccinated so we could celebrate!” (¡Vacunémonos para poder celebrar!”) (IDIs) | |

| “To be able to get together again. Vaccinate.” (“Poder reunirnos nuevamente. vacúnate”) (FGD) | ||

| Science, information, and debunking myths | African American | “Science has come a long way.” (FGD) |

| “If you’re unsure, ask a question.” (FGD) | ||

| “Do your own research.” (FGD) | ||

| Ethiopian/Eritrean | “We’re Christians but we can trust the science here. Get the vaccine.” | |

| “You won’t become a mutant if you get this shot. Here’s the science behind why…”(IDI) | ||

| Latinx | “To be informed is to prevent.” (“Informarse es prevenir”) (IDI) | |

| "Being well informed is prevention." (“Estar bien informado es prevenirse.”) (IDI) | ||

| Social responsibility/altruism/solidarity | Ethiopian/Eritrean | Love they neighbor. Get the vaccine. (IDI) |

| “I’m a mom and I got the vaccine so my kids could go back to school.” (FGD) | ||

| Latinx | “Help your community, get vaccinated!” (¡Ayuda a tu comunidad, vacúnate!) (IDI) | |

| “I got my vaccine, did you?” (“¿Yo recibí mi vacuna, y tu?”) (IDI) | ||

| WINNING SLOGAN: “Por mi salud y por tu salud, ¡vacúnate!” (“For my health and for your health, vaccinate!”) (IDI) |

African American key informants urged that messaging had to acknowledge history, recognizing what has happened in the past and use that as a starting place for why the COVID-19 vaccines are different. As one key informant said:

“…to have some understanding and appreciation for the reluctance of persons who have to make the decision – that it is with good reason that many people in our community are fearful, that’s men and women who have been abused in experiments and what have you…Messages need to respect the thinking, attitudes, the history, have an appreciation for it and then can communicate the difference today, have something to say about the appreciation for the development of science and the recognition that the scientific development of this vaccine was done by people of color as well – that’s a big help in the whole process.” (African American key informant, male, age 81)

Latinx interview participants focused on messages targeting vaccine information and tapping into social responsibility and altruism. Key sentiments expressed by Latinx focus group participants included: messages that emphasize community work better for this population, messaging must convey that many members of the Latinx community are essential workers and in need of the vaccine, and the Latinx community deals with a language barrier, messaging must address this. Participants felt strongly that messaging focused on altruism, which highlights protecting family, loved ones, and the community at large would be most effective with the Latinx community. Another main focus among Latinx participants was on the importance of messaging specifically aimed at debunking widely circulating myths about the vaccines (e.g., the vaccines turn people into zombies).

The main approaches to messaging proposed by Ethiopian/Eritrean interview participants included focusing on protecting family and business by getting vaccinated, debunking widely circulating myths with facts and science, and making it clear that the vaccines are free. Many Ethiopian/Eritrean participants thought it was important to ensure that messaging emphasized the vaccines were being provided for free to counter the belief that doctors were profiting off the vaccine and, importantly, because many in their community do not have health insurance, so cost was considered a concern. Participants described business and family as particularly compelling motivators, saying everyone in the community either owns a business or knows someone who does so, can relate to this motivation, and supporting family is of utmost importance within the community. A key informant articulated this point by saying:

The ability to go back to work and earn a living and support the family unit here, but also the extended families back home that are relying on them is probably the biggest motivation that I can think of. (Ethiopian key informant, female, age 27)

Ethiopian/Eritrean focus group participants were mostly satisfied with the slogans proposed by interview participants; however, they identified the need to include a religious aspect to vaccine messaging in an effort to appeal broadly to the community given how prevalent a role religion plays (the group came up with “Love thy neighbor. Get the vaccine.”, for example).

Finally, there were members of the FGDs who felt that due to the close-knit nature of the community and the levels of trust from peers, it would be more likely to increase vaccine acceptance through word-of-mouth than through any of the slogans or other channels being discussed. Several participants agreed that, with many members of the Ethiopian community working in nursing homes and hospitals, having them talk to friends, family, and neighbors about their experiences seeing COVID-19 patients and getting vaccinated against it would be more effective than any of the messaging slogans discussed.

The crowdsourcing contest winners reflected themes raised throughout the qualitative research. As seen in Table 2, the winning English slogan, with 27% of the votes, was “Vaccinate, so we can celebrate!”, reflecting the emphasis study participants placed on a positive focus on moving past the pandemic. The winning Spanish slogan, with 36% of the votes, was “Por mi salud y por tu salud, ¡vacúnate!” (“For my health and for your health, vaccinate!”) reflecting themes of altruism and the importance of protecting the community that arose throughout the interviews and focus groups.

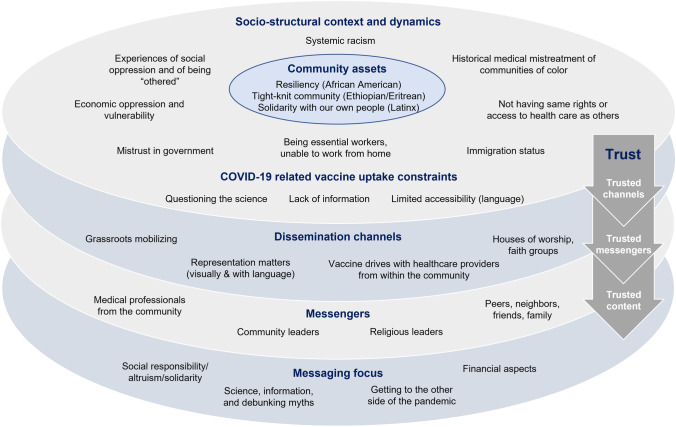

In an effort to synthesize and recognize both the socio-economic constraints and community assets and suggestions regarding effective health communication messaging, Fig. 1 offers a conceptual model that underscores the critical importance of trusted channels, messengers, and content utilized to promote engagement with COVID-19 and other vaccination efforts.

Fig. 1.

Community perspectives on achieving COVID-19 vaccine access and uptake equity among communities of color in Washington, DC

Discussion

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected communities of color in the USA, and while there is significant diversity within and across these communities, the qualitative findings presented here demonstrate how social and structural factors, including shared experiences of historic and ongoing socio-economic oppression and exclusion, have not only placed them at higher risk for COVID-19 infection and negative health outcomes but how they also underlie some community members’ hesitancy to get vaccinated. These findings mirror previous research, mostly quantitative in nature, on both COVID-19 related risk and vaccine uptake dynamics. [35–39].

Our results, however, also bring forth important community-based perspectives and solutions regarding how to effectively promote COVID-19 vaccine uptake including reliance on trusted messengers, channels, and messaging, which acknowledges the socio-economic context in which these communities live and work, as well as their collective strengths, assets, and resilience. Qualitative insights from the current study provide an important understanding of why and how misinformation spreads so easily when specific communities feel and experience a sense of marginalization and mistreatment, leading to a lack of trust in information associated with governmental and non-governmental structures that are linked to these feelings and experiences. The relationship between historic discrimination and mistrust in healthcare institutions has been documented in research from multiple contexts and population groups [40].

When engaging communities who have experienced historical oppression, it, in turn, becomes even more important to ensure that those delivering the messages are known and trusted within that community. An example of this is the critical role that the church has historically played, particularly among African Americans and African immigrants, serving as a place of refuge and a meeting place for community organizing within social movements. As seen here, trusted institutions such as churches have a critical role to play in COVID-19 vaccine awareness and uptake. Public health researchers, officials, and program implementation specialists need to actively seek partnership and learn from institutions that have served marginalized communities for decades and have in turn earned their trust. Such institutions have been key partners in the rollout of other types of vaccines (e.g., HPV)[31] as well as testing and screening efforts including HIV testing. [32].

Most importantly, the social and structural determinants of health underscored by study respondents in the current analysis must be fundamentally challenged and these root causes of health inequities addressed so that what has occurred during COVID-19 is not perpetuated. Calls for greater attention to social determinants related to COVID-19 and other forms of vaccine uptake are increasing in the literature in both domestic and global settings [41, 42]. By using community-informed and community-based participatory research approaches such as those utilized here we are able to make visible these forces so that appropriate strategies can be developed and communities can be mobilized in their implementation. Moving forward, African Americans, African immigrants, Latinx, and other disproportionately affected community members, groups, and institutions must be fully engaged and treated as equal partners in the process of ensuring that accurate and trusted public health messages are widely disseminated and that access to current and future vaccines for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases is secured. Examples of tailored community-based interventions among African-American and Latinx populations are beginning to emerge [43, 44]. These examples also emphasize the need for multi-component and multi-level approaches that tackle social-structural, as well as individual-level factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake within a given population group [45].

This study is not without limitations. For example, we employed a cross-sectional design, limiting our understanding of complex social dynamics to one point in time. Vaccine attitudes and uptake have also continued to evolve and shift during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in a rapidly changing scientific and political environment. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine how these contextual factors may shift over time and influence changes in perspectives and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, including in the context of the roll-out of a greater number of vaccine mandates and requirements across settings and work environments. Despite such limitations, these findings were able to be immediately utilized by DC Health in their health communications and messaging to support vaccine uptake among communities of color. Additionally, the community-based approach to message development offers a model for future vaccine and public health messaging development.

Conclusion

Communities of color in the USA have both unique and shared historical and current social and economic conditions and experiences that shaped their views regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. These realities and perspectives must be understood and respected, while community connectedness and solidarity can be leveraged to inform trusted and effective health communication messaging and create vaccine equity for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease of 2019

- CBO

Community based organization

- DC Health

Washington, DC Department of Health

- FGD

Focus group discussions

- GWU

George Washington University

- ICE

Immigration and customs enforcement

- IDI

In-depth interview

- KII

Key informant interview

- USA

United States of America

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to study conception and design, or data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Deanna Kerrigan, Andrea Mantsios, Tahilin Sanchez Karver, Wendy Davis, Tamara Taggart, Sarah K. Calabrese, Allison Mathews, Kimberly Henderson, and Kimberly Harris contributed to the study’s conception and design. Sullivan Robinson, Regretta Ruffin, Geri Feaster-Bethea, Lupi Quinteros-Grady, Carmen Galvis, Rosa Reyes, Gabriela Martinez, Mesgana Tesfahun, Ambrose Lane, and Shanna Peeks contributed to data collection and interpretation. Andrea Mantsios and Tahilin Sanchez Karver conducted the data analysis. All authors read, provided feedback, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by DC Health.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DK, upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health and DC Health.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/11/2022

The current version of this article includes institutional names for the research being discussed throughout the article that were missing from the article as originally published.

Contributor Information

Deanna Kerrigan, Email: dkerrigan@gwu.edu.

Andrea Mantsios, Email: amantsios@phiaconsulting.org.

Tahilin Sanchez Karver, tkarver@email.gwu.edu.

Wendy Davis, wendywdavis@email.gwu.edu.

Tamara Taggart, ttaggart@email.gwu.edu.

Sarah K. Calabrese, Email: skcalabrese@gwu.edu

Allison Mathews, Email: info@communityexpertsolutions.com.

Sullivan Robinson, Email: sullivanrobinson@msn.com.

Regretta Ruffin, Email: pastorrbj@msn.com.

Geri Feaster-Bethea, Email: feastg9142@verizon.net.

Lupi Quinteros-Grady, Email: lupi@layc-dc.org.

Carmen Galvis, Email: carmen@layc-dc.org.

Rosa Reyes, Email: rosar@layc-dc.org.

Gabriela Martinez Chio, Email: gabrielam@layc-dc.org.

Mesgana Tesfahun, Email: mesgana@layc-dc.org.

Ambrose Lane, Email: ambrose@healthalliancenetwork.net.

Shanna Peeks, Email: s_peeks@yahoo.com.

Kimberly M. Henderson, Email: Kimberly.Henderson@dc.gov

Kimberly M. Harris, Email: kmharris1@gmail.com

References

- 1.Romano SD, Blackstock AJ, Taylor EV, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations, by Region — United States, March–December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:560–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackey K, Ayers C, Kondo K, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19–related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021;174(3):362–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mude W, Oguoma VM, Nyanhanda T, Mwanri L, Njue C. Racial disparities in COVID-19 pandemic cases, hospitalisations, and deaths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:05015. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelner J, Trangucci R, Naraharisetti R, et al. Racial disparities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality are driven by unequal infection risks. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(5):e88–e95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. July 16, 2021 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed July 22 2021).

- 6.Morgan RC, Jr, Reid TN. On answering the call to action for COVID-19: continuing a bold legacy of health advocacy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn AV, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein RA, Ometa O. When public health crises collide: social disparities and COVID-19. Int J Clin Pract 2020; 74(9): e13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Fortuna LR, Tolou-Shams M, Robles-Ramamurthy B, Porche MV. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: the need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(5):443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantamneni N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marginalized populations in the United States: a research agenda. J Vocat Behav 2020; 119: 103439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Brown S. How COVID-19 is affecting Black and Latino families' employment and financial well-being. 2020. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-covid-19-affecting-black-and-latino-families-employment-and-financial-well-being (accessed July 22, 2021.

- 12.Garcia MA, Homan PA, García C, Brown TH. The color of COVID-19: structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older Black and Latinx adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(3):e75–e80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray R. Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19? 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/ (accessed July 22, 2021.

- 14.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milam AJ, Furr-Holden D, Edwards-Johnson J, et al. Are clinicians contributing to excess African American COVID-19 deaths? Unbeknownst to Them They May Be. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):139–141. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eligon J, Burch ADS. Questions of bias in COVID-19 treatment add to the mourning for Black families. NY Times. 2020;10:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbaro M, Pathak N, MItchel A, Mills A. The mistakes New York made. In: Barbaro M, editor. The Daily. New York: New York Times; 2020.

- 18.Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18–39 years - United States, March-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):928–933. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer research associates, UNIDOS US, NAACP, COVID collaborative. Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy in Black and Latinx Communities. 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f85f5a156091e113f96e4d3/t/5fb72481b1eb2e6cf845457f/1605837977495/VaccineHesitancy_BlackLatinx_Final_11.19.pdf (accessed July 22, 2021.

- 20.Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Lopes L, Kearney A, Sparks G, Brodie M. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) COVID-19 vaccine monitor: January 2021. 2021. https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-january-2021-vaccine-hesitancy/ (accessed July 22, 2021.

- 21.Boyd R. Black people need better vaccine access, not better vaccine attitudes. The New York Times. 2021.

- 22.Corbie-Smith G. Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210434. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, et al. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113638. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein S, MacDonald NE, Guirguis S. Health communication and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4212–4214. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khubchandani J, Macias Y. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in Hispanics and African-Americans: a review and recommendations for practice. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;15:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell J, Plano CV. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang W, Ritchwood TD, Wu D, et al. Crowdsourcing to improve HIV and sexual health outcomes: a scoping review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(4):270–278. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00448-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2018;15(8):e1002645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker JD, Fenton KA. Innovation challenge contests to enhance HIV responses. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(3):e113–e115. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohleder P, Lyons AC. Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahijani AY, King AR, Gullatte MM, Hennink M, Bednarczyk RA. HPV vaccine promotion: the church as an agent of change. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113375. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart JM, Thompson K, Rogers C. African American church-based HIV testing and linkage to care: assets, challenges and needs. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(6):669–681. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1106587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, Hall E, Honermann B, Crowley JS, Baral S, Prado GJ, Marzan-Rodriguez M, Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, Millett GA. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;52:46–53.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertsimas D, Lukin G, Mingardi L, Nohadani O, Orfanoudaki A, Stellato B, Wiberg H, Gonzalez-Garcia S, Parra-Calderón CL, Robinson K, Schneider M, Stein B, Estirado A, Beccara LA, Canino R, Dal Bello M, Pezzetti F, Pan A, Hellenic COVID-19 study group COVID-19 mortality risk assessment: an international multi-center study. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal R, Dugas M, Ramaprasad J, Luo J, Li G, Gao GG. Socioeconomic privilege and political ideology are associated with racial disparity in COVID-19 vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(33):e2107873118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107873118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardona S, Felipe N, Fischer K, Sehgal NJ, Schwartz BE. Vaccination disparity: quantifying racial inequity in COVID-19 vaccine administration in Maryland. J Urban Health. 2021;98(4):464–468. doi: 10.1007/s11524-021-00551-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes MM, Wang A, Grossman MK, Pun E, Whiteman A, Deng L, Hallisey E, Sharpe JD, Ussery EN, Stokley S, Musial T, Weller DL, Murthy BP, Reynolds L, Gibbs-Scharf L, Harris L, Ritchey MD, Toblin RL. County-level COVID-19 vaccination coverage and social vulnerability - United States, December 14, 2020-March 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(12):431–436. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7012e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel M, Critchfield-Jain I, Boykin M, Owens A. Actual racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality for the Non-Hispanic Black compared to Non-Hispanic White population in 35 US States and their association with structural racism. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;27:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01028-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Ristea A, Amiri M, Dooley D, Gibbons S, Grabowski H, Hargraves JL, Kovacevic N, Roman A, Schutt RK, Gao J, Wang Q, O'Brien DT. Vaccination intentions generate racial disparities in the societal persistence of COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19906. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99248-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sripad P, Ozawa S, Merritt MW, Jennings L, Kerrigan D, Ndwiga C, Abuya T, Warren CE. Exploring meaning and types of trust in maternity care in peri-urban Kenya: a qualitative cross-perspective analysis. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(2):305–320. doi: 10.1177/1049732317723585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ataguba OA, Ataguba JE. Social determinants of health: the role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1788263. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1788263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viswanath K, Bekalu M, Dhawan D, Pinnamaneni R, Lang J, McLoud R. Individual and social determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):818. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10862-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Casey S, Jews V, King A, Simmons K, Hogue MD, Belliard JC, Peverini R, Veltman J. A three-tiered approach to address barriers to COVID-19 vaccine delivery in the Black community. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e749–e750. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peteet B, Belliard JC, Abdul-Mutakabbir J, Casey S, Simmons K. Community-academic partnerships to reduce COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in minoritized communities. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;1:34. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marquez C, Kerkhoff AD, Naso J, Contreras MG, Castellanos Diaz E, Rojas S, Peng J, Rubio L, Jones D, Jacobo J, Rojas S, Gonzalez R, Fuchs JD, Black D, Ribeiro S, Nossokoff J, Tulier-Laiwa V, Martinez J, Chamie G, Pilarowski G, DeRisi J, Petersen M, Havlir DV. A multi-component, community-based strategy to facilitate COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Latinx populations: from theory to practice. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0257111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DK, upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.