Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to examine racial differences in patient portal activation and research participation among patients with prostate cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants were African American and White patients with prostate cancer who were treated with radical prostatectomy (n = 218). Patient portal activation was determined using electronic health records, and research participation was measured based on completion of a social determinants survey.

RESULTS

Thirty-one percent of patients completed the social determinants survey and enrolled in the study and 66% activated a patient portal. The likelihood of enrolling in the study was reduced with greater levels of social deprivation (odds ratio [OR], 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.98; P = .04). Social deprivation also had a signification independent association with patient portal activation along with racial background. African American patients (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.91; P = .02) and those with greater social deprivation (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.82; P = .002) had a lower likelihood of activating a patient portal compared with White patients and those with lower social deprivation.

CONCLUSION

Although the majority of patients with prostate cancer activated their patient portal, rates of patient portal activation were lower among African American patients and those who lived in areas with greater social deprivation. Greater efforts are needed to promote patient portal activation among African American patients with prostate cancer and address access to health information technology among those who live in socially disadvantaged geographic areas.

INTRODUCTION

Increased attention is being given to social determinants of health (SDOH) in clinical and research settings1-3; conceptual models of population health and health disparities now emphasize the contribution of these factors to health care and outcomes.4,5 As a result, studies are being conducted to examine the contribution of SDOH to clinical outcomes6,7 and identify barriers and best practices to obtaining self-reported data on social determinants.8 Furthermore, health care systems are now being held accountable for addressing social risk factors as part of population health management and health care providers are expected to understand the patient’s social background and how these factors contribute to health care outcomes.1,3,9

CONTEXT

Key Objective

A better understanding of the associations between patient portal activation, study enrollment, and social deprivation in patients with prostate cancer can help guide efforts to enhance the use health information technology to improve research efforts and health care delivery in these patients.

Knowledge Generated

There were modest levels of study enrollment and patient portal activation. Greater social deprivation was associated with a reduced likelihood of activating a patient portal and study enrollment among patients with prostate cancer.

Relevance

Greater efforts are needed to promote patient portal activation and improve access to health information technology among patients who live in areas with social disadvantage.

To develop effective strategies for population health management and implement evidence-based strategies for addressing unmet social needs, patients must be willing to provide self-reported data on social determinants as part of clinical and research protocols. Empirical data are emerging on efforts to obtain SDOH among patients10-12; one way that has been proposed to enhance collection of self-reported social determinants data is via patient portals. Patient portals have emerged as a strategy for improving patient engagement in their health care through greater interaction with providers.13,14 Patient portals are a core requirement of stage 2 of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)15; stage 2 requires implementation of patient portals to improve the exchange of patient information and allow patients access to their medical records.16 Efforts are now being made to develop portals to enhance the quality of cancer care and symptom monitoring among patients17; however, racial differences in activation of patient portals18 may exacerbate disparities in access to cancer care services. Patient portals can also be used to support research activities. However, Tabriz et al19 found that African American primary care patients who had an activated patient portal were less likely than Whites to open recruitment materials for a colorectal cancer screening trial that was delivered through the portal.

To our knowledge, prior research has not examined enrollment rates in studies that are designed to obtain patient-reported data on SDOH. In this study, we examined enrollment rates in an observational study that is obtaining self-reported data on SDOH among patients with prostate cancer. We also examined activation of the patient portal among these patients based on their race, clinical characteristics, and social deprivation. Social deprivation is a composite measure of disadvantage that is based on socioeconomic factors at the census tract level20; among primary care patients who actively declined to participate in telehealth trials for depression or cardiovascular disease risk, the most important reason for declining enrollment was lack of access to resources for health information technology (HIT).21 Furthermore, technology barriers were important reasons for declining enrollment among patients who received medical care in practices that were located in socially deprived areas.21 In the United States, approximately 20% of adults do not have broadband access22 and African American households are less likely than White households to have a desktop, laptop, or handheld device that has broadband access.23 A better understanding of the association between study enrollment, patient portal activation, and social deprivation in patients with prostate cancer can help guide efforts to enhance the use of HIT to improve research efforts and health care delivery in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The participants in this study were patients with prostate cancer who provided a tissue sample to the Biorepository and Tissue Analysis Shared Resource (BTA) at MUSC’s Hollings Cancer Center as part of having a radical prostatectomy. A total of 351 patients were identified from the BTA and of these, 16 were removed from the recruitment list by their physician, two were deceased, six invitation letters were returned as undeliverable, and eight were pending contact. These 32 patients were excluded from the statistical analysis. Of the remaining 319 patients, those who were missing a disposition on patient portal activation (eg, their portal activation status in EPIC was not categorized as being active, inactivated, declined, or pending activation) (n = 32) were also excluded from the analysis. The patients who were not African American or White (n = 4) and those who did not have an address that could be geocoded to determine social deprivation (n = 65) were also excluded; thus, the study sample included 218 patients with prostate cancer who had a tissue sample available in the BTA when study recruitment was initiated in 2016 and had a definitive enrollment outcome.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at MUSC. First, information on sociodemographics, prostate cancer variables, and comorbidities was abstracted from patient’s medical records. Next, the patients were contacted by mailed invitation to enroll in a social determinants survey (SDS) that measured SDOH, quality of life, and health behaviors for cancer control. The patients could decline to participate in the SDS by contacting a research specialist at MUSC by telephone or electronic mail. Those who did not decline were contacted to complete the SDS. The patients were contacted to complete the SDS by telephone for a 2-month period or 15 call attempts. If they did not complete the survey during this time, they were maxed out for study enrollment.

Measures

The following clinical data elements were abstracted from the electronic health record for each patient: race, year of birth, date of diagnosis, prostate-specific antigen at diagnosis, and pathologic stage. Comorbidities (eg, hypertension and diabetes) were obtained from the patient’s problem list as recorded in the electronic health record. The patients who had at least one of these conditions were categorized as having a chronic condition and those who did not have any of these conditions were categorized as not having any comorbidities. Stage was recoded into a binary variable of T2/T2b versus T2c or higher. The amount of time since diagnosis was calculated based on the date of diagnosis. We recoded time since diagnosis into a binary variable of being diagnosed within the past 2 years or more recently, or being diagnosed more than 2 years from the date study recruitment was initiated. Social deprivation was determined by geocoding residential street addresses to spatial coordinates using the geocoder in ESRI’s ArcGIS geographic information systems. Census tract level identifiers were then assigned to the patients by using spatial overlay analyses that joined geocoded residential locations with census boundary files from the US Census. Finally, census tract identifiers were used to link the patient’s residential address to social deprivation scores from the Robert Graham Center.20 Scores for social deprivation could range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater social deprivation.

The primary outcome variables were study enrollment and patient portal activation. Study enrollment was based on the completion of the SDS. The patients who completed the SDS were categorized as having enrolled in the study. The patients who declined to be contacted about participating in the SDS, those who declined to complete the survey when they were contacted, and the patients who could not be reached after multiple attempts were categorized as study enrollment decliners. The participants were given $15 following enrollment and completion of the SDS. Activation of the patient portal was determined based on whether the patients set up an Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) MyChart account to access portions of their medical record. Specifically, the patients were categorized as having activated the patient portal if their status was activated. The patients whose activation status in Epic was inactivated, declined, or pending activation were categorized as not having activated their patient portal.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated to characterize the study sample and to describe study enrollment rates and activation of the patient portal. Chi square tests of association and T-tests were performed to examine the association between study enrollment, race, prostate cancer variables, and patient portal activation. This same strategy was used to examine bivariate associations with patient portal activation. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors having significant independent associations with study enrollment and patient portal activation. The fully adjusted regression model for each of these outcomes included factors that are clinically relevant to prostate cancer (eg, prostate-specific antigen and stage), regardless of their bivariate association with study enrollment or patient portal activation, and those that had a bivariate association of P < .10 with each of these variables.

RESULTS

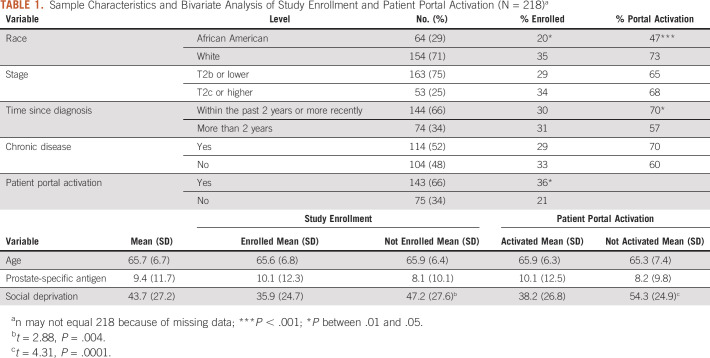

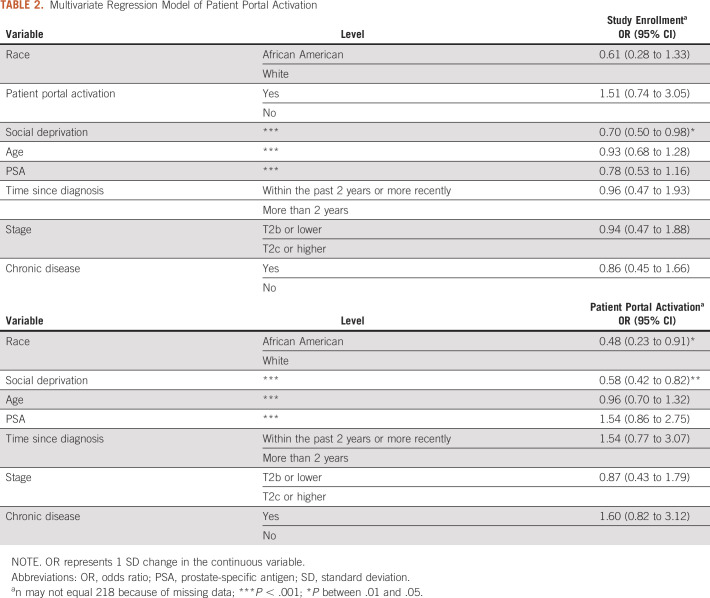

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample. Overall, 31% of patients enrolled in the study and completed the SDS. There were significant racial differences in study enrollment; 20% of African American patients completed the SDS and enrolled in the study compared with 35% of White men (Table 1). Study enrollment differed based on social deprivation; social deprivation was lower among patients who enrolled in the study compared with those who declined enrollment. Study enrollment also differed based on patient portal activation. Thirty-six percent of patients with an activated patient portal enrolled in the study compared with 21% of patients who did not have an activated patient portal. The results of the fully adjusted multivariate logistic regression model (P = .12 for model) for study enrollment are provided in Table 2. Only social deprivation had a significant independent association with study enrollment in the multivariate regression model; the likelihood of study enrollment was reduced with greater social deprivation (odds ratio [OR], 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.98; P = .04).

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics and Bivariate Analysis of Study Enrollment and Patient Portal Activation (N = 218)a

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Regression Model of Patient Portal Activation

Sixty-six percent of patients had an activated patient portal. There were significant racial differences in activation of the patient portal; 47% of African American patients had a portal activated compared with 73% of White patients. There were also significant differences in patient portal activation based on the amount of time since diagnosis. The patients who were diagnosed with prostate cancer within the past 2 years or more recently of recruitment were significantly more likely to have an activated patient portal compared with those who had been diagnosed for a longer period. Patient portal activation also differed based on social deprivation; social deprivation was lower among patients who had activated the portal compared with those who had not activated the patient portal. Table 2 shows the results of the fully adjusted multivariate logistic regression model for patient portal activation (P = .001); race and social deprivation had significant independent associations with patient portal activation. African American patients had a significantly reduced likelihood of patient portal activation compared with White patients (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.91; P = .02). In addition, the likelihood of activating the patient portal was reduced with greater social deprivation (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.82; P = .002).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to characterize enrollment rates in a social determinants study and activation of a patient portal among African American and White patients with prostate cancer. Overall, 31% of patients enrolled in the study and provided self-reported data on their SDOH and quality of life. As greater emphasis is placed on understanding SDOH as part of medical care,24 it is important to identify patients who are most and least likely to provide this information as part of research protocols. Only about one third of patients enrolled in the study and completed the SDS; this may be because of lack of interest in completing the survey and competing priorities. Another possibility is that patients were asked to complete the SDS outside of a medical care visit. Enrollment rates, and provision of self-reported data on SDOH as part of completing the SDS, may be higher if patients are asked to provide this information as part of a medical visit related to their cancer care. However, key issues in implementing SDOH assessments into health care systems include length of surveys being disruptive to clinical workflows, patients may not complete these assessments, determining what actionable information will be obtained, and deciding who will capture SDOH data.25,26 HIT, which can include patient portals, is among the strategies that are being implemented to improve the quality of health care. Patient portals could be a mechanism for obtaining self-reported data on SDOH. In this study, 65% of patients had activated their patient portal, but there were significant racial differences in activation rates. African American patients had a significantly lower likelihood of activating their patient portal compared with White patients. This finding is consistent with the results from recent studies,27,28 but patient portal activation rates in this study were higher (65% of patients activated their MyChart account) relative to the rates observed in studies that examined patient portal activation during a specific period. We did not limit our analysis of patient portal activation to a specific period; rather, our measure of patient portal activation was determined based on the patient’s current activation status. This may explain the differences in activation rates in our study and other research.

Social deprivation had a significant association with both study enrollment and patient portal activation; the likelihood of enrolling in the study and activating a patient portal were reduced with greater social deprivation. Geographic factors are now incorporated into conceptual models of minority health and health disparities29; previous studies have shown that geographic factors such as travel distance can have an adverse effect on accrual to clinical trials and access to cancer care and treatment outcomes.30-33 In particular, travel distance and difficulty getting to the study site were among the reasons for declining participation in a physical activity randomized trial among patients with breast cancer.34 Notably, travel distance was not a component of enrolling in this study; however, the patients did have to have access to a telephone or HIT (eg, computer and smartphone) to complete the SDS and activate the patient portal, respectively. Social deprivation reflects the level of disadvantage in a geographic area25; our findings suggest that the overall disadvantage at the community level may be more important to study enrollment than individual-level factors such as race, but both individual- and community-level factors may play a role in patient portal activation. In the case of patient portal activation, geographic areas with high social deprivation may not have sufficient broadband access in their homes or community settings, and residents may not be able to afford internet subscriptions and the equipment that is needed to establish connections. In South Carolina, for instance, about one third of residents do not have a broadband internet subscription.35 Previous research has shown that nationally, African Americans are more likely than Whites to rely on smartphones to connect to the Internet and are more likely to have canceled or cut off this service because of financial hardships.36,37 With respect to study enrollment, recent research has shown that when asked to participate in a clinical trial, there are negligible differences in enrollment rates between minorities and nonminorities, but the availability of clinical trials at the health care system is an important determinant of clinical trial participation.38 Although all the patients in this study were treated for prostate cancer at the same academic medical center, enrollment in the research took place in their communities and households. The stress associated with managing financial hardships, poverty, and housing challenges and the priority placed on resolving these issues may reduce interest and ability to participate in a survey study among patients who live in areas with high social deprivation.

The following limitations should be considered in this study. First, enrollment rates were examined based on completion of a cross-sectional SDS among patients with prostate cancer who were identified from a tumor registry at one NCI-designated cancer center. Access to HIT and computer literacy were not measured in this study. We also did not examine the association between self-reported SDOH and study enrollment and patient portal activation. These are important areas for future research. Although the proportion of African American patients who were identified for study participation through the BTA was consistent with the proportion of African American residents in the cancer center’s catchment area, there is an important distinction between identifying a sample that is representative of the catchment area population and the percentage and absolute number of participants who are enrolled. There is room for improvement in the absolute number of African American patients who enrolled in the study and completed the SDS.

Despite these potential limitations, this study provides novel empirical data about the recruitment of patients with prostate cancer to a translational study on racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes. Research on multilevel determinants of cancer health disparities is important for addressing the cancer burden in the catchment areas for NCI-designated cancer centers; this study shows that although the initial pool of patients identified from the tumor registry is representative of the racial diversity in the center’s catchment area population, only about one third of patients with prostate cancer enrolled in a study that had a relatively low participation burden. In contrast to previous studies that examined the association between individual-level variables (eg, race and income) and patient portal activation and research that measured patient portal activation specifically in minority patients,39,40 the results of this study show that aggregate levels of social disadvantage at the community level has an independent association with patient portal activation and study enrollment. The findings from this study and our previous research18 demonstrate that greater efforts are needed to enhance patient portal activation among African American patients and those who live in geographic areas with high social deprivation. Future studies are needed to examine the effects of recruitment interventions and methods that are developed to enhance enrollment rates in cancer research among African Americans using HIT.

Michael Lilly

Speakers' Bureau: Guardant Health

Research Funding: Bavarian Nordic, Bayer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities grant (Grant No. #U54MD010706) and National Cancer Institute grant (Grant No. #UG1CA189848).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Chanita Hughes Halbert, Stephen J. Savage, Jihad Obeid

Financial support: Chanita Hughes Halbert

Administrative support: Chanita Hughes Halbert

Collection and assembly of data: Chanita Hughes Halbert, Melanie Jefferson, Jihad Obeid

Data analysis and interpretation: Chanita Hughes Halbert, Caitlin Allen, Oluwole Babatunde, Richard Drake, Peggi Angel, Stephen J. Savage, Lewis Frey, Michael Lilly, Ted Obi, Jihad Obeid

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/cci/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Michael Lilly

Speakers' Bureau: Guardant Health

Research Funding: Bavarian Nordic, Bayer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC.Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: An American College of Physicians position paper Ann Intern Med 168577–5782018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatef E, Predmore Z, Lasser EC, et al. Integrating social and behavioral determinants of health into patient care and population health at Veterans Health Administration: A conceptual framework and an assessment of available individual and population level data sources and evidence-based measurements AIMS Public Health 6209–2242019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice & Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records . Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Stoff DM, et al. Moving toward paradigm-shifting research in health disparities through translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary approaches Am J Public Health 100S19–S242010suppl 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: The National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities Am J Public Health 981608–16152008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, et al. Relationship between social determinants of health and processes and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: Validation of a conceptual framework. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, et al. Quantifying direct effects of social determinants of health on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes Diabetes Technol Ther 1780–872015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kazak AE, Deatrick JA, Scialla MA, et al. Implementation of family psychosocial risk assessment in pediatric cancer with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT): Study protocol for a cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Implement Sci. 2020;15:60. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01023-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss JL, Murphy J, Filiaci VL, et al. Disparities in health-related quality of life in women undergoing treatment for advanced ovarian cancer: The role of individual-level and contextual social determinants Support Care Cancer 27531–5382019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold R, Bunce A, Cowburn S, et al. Adoption of social determinants of health EHR tools by community health centers Ann Fam Med 16399–4072018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruß I, Bunce A, Davis J, et al. Initiating and implementing social determinants of health data collection in community health centers Popul Health Manag 2452–582020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kusnoor SV, Koonce TY, Hurley ST, et al. Collection of social determinants of health in the community clinic setting: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:550. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5453-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dendere R, Slade C, Burton-Jones A, et al. Patient portals facilitating engagement with inpatient electronic medical records: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e12779. doi: 10.2196/12779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman LV, Masterson Creber RM, Benda NC, et al. Interventions to increase patient portal use in vulnerable populations: A systematic review J Am Med Inform Assoc 26855–8702019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicare and Medicaid programs; electronic health record incentive program. Final rule Fed Regist 20107544313–44588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicare and Medicaid programs; electronic health record incentive program—Stage 2. Final rule Fed Regist 20127753967–54162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez ES.Using patient portals to increase engagement in patients with cancer Semin Oncol Nurs 34177–1832018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obeid JS, Shoaibi A, Oates JC, et al. Research participation preferences as expressed through a patient portal: Implications of demographic characteristics JAMIA Open 1202–2092018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabriz AA, Fleming PJ, Shin Y, et al. Challenges and opportunities using online portals to recruit diverse patients to behavioral trials J Am Med Inform Assoc 261637–16442019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler DC, Petterson S, Phillips RL, et al. Measures of social deprivation that predict health care access and need within a rational area of primary care service delivery Health Serv Res 48539–5592013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foster A, Horspool KA, Edwards L, et al. Who does not participate in telehealth trials and why? A cross-sectional survey. Trials. 2015;16:258. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0773-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Census Bureau . United States QuickFacts–Broadband Access, 2019. Population Estimates, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau . The Digital Divide: Percentage of Households by Broadband Internet Subscription, Computer Type, Race and Hispanic Origin. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/internet.html [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giuse NB, Koonce TY, Kusnoor SV, et al. Institute of Medicine measures of social and behavioral determinants of health: A feasibility study Am J Prev Med 52199–2062017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas-Henkel C, Schulman M. Screening for social determinants of health in populations with complex needs: Implementation considerations. 2017 https://www.chcs.org/media/SDOH-Complex-Care-Screening-Brief-102617.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundar KR.Universal screening for social needs in a primary care clinic: A quality improvement approach using the your current life situation survey Perm J 2218–0892018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mook PJ, Trickey AW, Krakowski KE, et al. Exploration of portal activation by patients in a healthcare system Comput Inform Nurs 3618–262018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oest SER, Hightower M, Krasowski MD. Activation and utilization of an electronic health record patient portal at an academic medical center-impact of patient demographics and geographic location. Acad Pathol. 2018;5:2374289518797573. doi: 10.1177/2374289518797573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities . NIMHD Research Framework. 2017. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework.html [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CC, Bruinooge SS, Kirkwood MK, et al. Association between geographic access to cancer care, insurance, and receipt of chemotherapy: Geographic distribution of oncologists and travel distance J Clin Oncol 333177–31852015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fletcher SA, Marchese M, Cole AP, et al. Geographic distribution of racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201839. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cary KC, Punnen S, Odisho AY, et al. Nationally representative trends and geographic variation in treatment of localized prostate cancer: The urologic diseases in America project Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 18149–1542015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fogel DB.Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review Contemp Clin Trial Commun 11156–1642018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gollhofer SM, Wiskermann J, Schmidt ME, et al. Factors influencing participation in a randomized controlled resistance exercise intervention study in breast cancer patients during radiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:186. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1213-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Census Bureau . South Carolina QuickFacts, 2019. Population Estimates, American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/SC [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrin A, Turner E. Smartphones Help Blacks, Hispanics Bridge Some–But Not All–Digital Gaps With Whites. Pew Research Center; 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/20/smartphones-help-blacks-hispanics-bridge-some-but-not-all-digital-gaps-with-whites/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith A. Chapter One: A Portrait of Smartphone Ownership. Pew Research Center; 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/01/chapter-one-a-portrait-of-smartphone-ownership/#cancel-phone [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation J Natl Cancer Inst 111245–2552019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallace LS, Angier H, Huguet N, et al. Patterns of electronic portal use among vulnerable patients in a nationwide practice-based research network: From the OCHIN Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) J Am Board Fam Med 29592–6032016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Sandberg JC, et al. Patient portal utilization among ethnically diverse low income older adults: Observational study. JMIR Med Inform. 2017;14:e47. doi: 10.2196/medinform.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]