ABSTRACT

Macrophages of the M2 phenotype in malignant tumors significantly aid tumor progression and metastasis, as opposed to the M1 phenotype that exhibits anti-cancer characteristics. Raising the ratio of M1/M2 is thus a promising strategy to ameliorate the tumor immunomicroenvironment toward cancer inhibition. We report here that tumor necrosis factor superfamily-15 (TNFSF15), a cytokine with anti-angiogenic activities, is able to facilitate the differentiation and polarization of macrophages toward M1 phenotype. We found that tumors formed in mice by Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells artificially overexpressing TNFSF15 exhibited retarded growth. The tumors displayed a greater percentage of M1 macrophages than those formed by mock-transfected LLC cells. Treatment of mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells with recombinant TNFSF15 led to augmentation of the phagocytic and pro-apoptotic capacity of the macrophages against cancer cells. Mechanistically, TNFSF15 activated STAT1/3 in bone marrow cells and MAPK, Akt and STAT1/3 in naive macrophages. Additionally, TNFSF15 activated STAT1/3 but inactivated STAT6 in M2 macrophages. Modulations of these signals gave rise to a reposition of macrophage phenotypes toward M1. The ability of TNFSF15 to promote macrophage differentiation and polarization toward M1 suggests that this unique cytokine may have a utility in the reconstruction of the immunomicroenvironment in favor of tumor suppression.

KEYWORDS: TNFSF15, macrophage, differentiation, polarization, cancer immunity, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in both men and women worldwide1. As the main cause of lung cancer mortality, metastasis is of great concern in cancer research. Increasing reports have indicated the correlation of tumor microenvironment with cancer progression and metastasis.2 In particular, tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), a major tumor-infiltrating immune cell population, are critical to tumor growth, invasion and metastasis.3 Macrophages are highly plastic cells that can respond to micro-environmental stimuli to become polarized as a classic (M1) or an alternative (M2) phenotype.4 A large body of evidence suggests that macrophages within the tumor microenvironment are educated by cancer cells to be M2 phenotype, which promote tumor progression and suppress anti-tumor immune response.3,5,6 Notwithstanding their tumor promoting effects, macrophages are actually capable of killing tumor cells by releasing inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as carrying out phagocytosis and activating other immune cells, which are considered as tumor killing M1 phenotype.7,8 Recently, many studies focus on depleting M2-like TAMs or blocking CCL2/CCR2 recruitment pathway, or interfering with M2-related signaling pathways such as CD47/SIRPα to develop strategy against cancers.9 However, there is a non-ignorable concern that elimination of tumor associated macrophages (TAM) often debilitate the anti-cancer effect of chemotherapy drugs because of the ineffective activation of the other immunological components.10,11 In human lung cancers, a higher density of the M1 macrophages and lower density of the M2 macrophages is associated with good clinical outcomes.12–14 Therefore, it is desirable to identify means to modulate the balance of M1/M2 populations toward M1 macrophages, with the purpose of restoring anti-cancer immunity in malignant tumors.

Tumor necrosis factor superfamily-15 (TNFSF15, also known as VEGI15 or TL1A16), a multifaceted cytokine, is mainly produced by endothelial cell in established blood vessels,17 and in turn inhibits angiogenesis.18–20 Our previous study demonstrated that raising TNFSF15 levels in tumors can inhibit tumor growth.15,21 Additionally, TNFSF15 has been shown to be involved in the maintenance of inflammatory homeostasis, which can both activate Th1/Th2 immune response in different inflammation diseases.22–24 Moreover, TNFSF15 plays a significant role in the modulation of the functions of immune cells, such as promoting T cells activation,16 dendritic cells maturation,25 NK cell toxicity enhancement,26 and antimicrobial ability of macrophages.27 Interestingly, TNFSF15 gene expression is nearly completely down-regulated in proliferating endothelial cells as well as in tumor vasculatures.19,28,29 In this study, we investigated plausible activities of TNFSF15 in the modulation of tumor microenvironment, with a focus on macrophage differentiation and polarization.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7, Lewis lung carcinoma cells LLC, and breast cancer cell line 4T1 were purchased from the Cell Resource Center (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China) and cultured in RMPI-1640 (Gibco), high glucose DMEM (Hyclone) or DMEM/F12 (Hyclone) medium, respectively. Mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested from the peritoneal fluid of mice five days after intraperitoneal injection of thioglycolate (BD) and cultured in RPMI 1640. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, BD) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS, Gibco). These cells were placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. TNFSF15 and 4–3 H were prepared in our laboratory.18,21 One unit of TNFSF15 activity is defined as the IC50 of the preparation on bovine aortic endothelial cell proliferation – namely, the concentration of TNFSF15 required for half-maximum inhibition of cell growth in culture. DR3 Fc chimera and cryptotanshinone were purchased from R&D Systems and MCE, respectively. SB203580, U0126, Sp600125 and Ly294002 were purchased from Beyotime.

Mouse models

All animal experiments were approved by the Institute Research Ethics Committee of Nankai University. C57BL/6 mice (6–8-week-old) were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Center (Beijing, China), and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to standard food and water.

Polarization model of peritoneal macrophage in vivo

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with recombinant TNFSF15 (5 mg/kg, every other day) or buffer for 7 days. Then peritoneal cells were recovered by lavage with PBS for FACS analysis.

LLC allograft models

The female C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5 × 105 LLC cells into the right flank and tumor size (length×width2 × π/6) were monitored every other day. (1) For LLC allograft model with recombinant TNFSF15 treatment for one week, the tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into two groups on day 11 and then para-tumorally injected recombinant TNFSF15 (5 mg/kg, every other day, or buffer for 7 days. (2) For LLC allograft model on the mice with tdTomato+ bone marrow transplantation, the tumor-bearing mice accepted tdTomato+ bone marrow transplantation were randomly divided into two groups, then para-tumorally injected recombinant TNFSF15 (5 mg/kg) or buffer every 3 days until retrieved tumors on day 18.

Isolation of single cells from murine tumors

The LLC tumors were minced and then enzymatically dissociated in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution containing 1 mg/mL Collagenase IV (Sigma), 0.1 mg/mL Hyaluronidase V (Sigma) and 5 μU/mL DNAse I (Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. Red blood cells were solubilized with red cell lysis buffer (Solarbio), and the resulting suspension was filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer again to produce a single cell suspension for flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry

For surface markers analysis, live cells were re-suspended in 1 × PBS and stained with anti-mouse CD45 (30-F11, Biolegend), CD11b (M1/70, R&D Systems), F4/80 (BM8, Biolegend), CD86 (GL-1, Biolegend), MHC-II (M5/114.15.2, Biolegend), CD117 (2B8, Biolegend), CD115 (AFS98, Biolegend), CD16/32 (93, Biolegend), CD34 (HM34, Biolegend), Sca1 (D7, Biolegend), SIRPα (P84, biolegend), Lin (Stem Cell), and APC-Cy7 Streptavidin (Biolegend) at 4°C for 30 min. The concentration at each antibody was used as the product protocol recommended. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fixation and Permeabilization Kit (eBioscience) at room temperature for 40 min and labeled with anti-mouse CD206 (C068C2, Biolegend). Multicolor FACS analysis was performed on an LSR Fortessa Analyzer (BD Biosciences). All data analysis was performed using the flow cytometry analysis program FlowJo-V10.

Immunofluorescence

The sections of tumor issues (5 μm) were fixed in 100% cold methanol for 20 min, then permeabilizated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Blocking with 5% BSA for 60 min at room temperature, tissue sections were incubated with anti-F4/80 (Biolegend) for 1 h at 37°C. Sections were washed three times with PBST and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies. Slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to identify nuclei. Images were analyzed on Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope.

Phagocytosis assays

Flow-cytometry-based phagocytosis assay. RAW264.7 cells were treated with or without TNFSF15 for 24 h and target cells were fluorescently labeled with Calcein AM (Invitrogen) for 15 min as per the manufacturer’s instructions. 400,000 target cells and 200,000 macrophages were co-cultured for 2 h in ultra-low-attachment 24-well U-bottom plates (Corning) in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Then these cells were placed on ice, and stained with APC-labeled anti-F4/80 to analyze by flow cytometry. Phagocytosis was measured as the number of F4/80+GFP+ macrophages, quantified as a percentage of the total F4/80+ macrophages.

Fluorescence microscopy–based phagocytosis assay. RAW264.7 cells (2 × 105, with or without TNFSF15 treatment) labeled with CFSE were cultured in 35-mm glass-bottom confocal dishes along with pHrodo-SE (Introvigen) labeled LLC and 4T1 cancer cells at a ratio of 1:2, respectively. After co-incubation for 5–6 h at 37°C, cells were washed several times with basic PBS to remove unengulfed pHrodo-labeled tumor cells. Phagocytosis (%) was calculated according to the following formula: the number of RAW264.7 cells phagocytosing cancer cells/total number of RAW264.7 cells × 100.

Cell proliferation assay

Bone marrow cells were incubated with 5 μΜ CFSE (5, 6- carboxyfluorescein diacetate, MCE) for 10 min in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The cells were collected and cultured in RPMI 1640 with 15% FBS to further experiment.

STAT1 knockdown

RAW264.7 cells were plated in 12-well plates and then transfected with 100 nM STAT1 siRNA (Santa Cruz) using Lipo3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The indicated scrambled siRNAs were chemically synthesized by Ruibo.

NO and ROS assays

For NO assay, total nitrite/nitrate was measured in cell supernatant by Griess reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For ROS assay, macrophages were incubated with 50 μΜ DCFDA (MCE) for 10 min in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, then washed three times with ice cold PBS for FACS analysis.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA (1 μg) was extracted from cells or tumor tissues with TRIzol reagent (CWBIO) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA by TransZol UP Plus RNA Kit (TransGen Biotech). The cDNA was amplificated by the TransStart Tip Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech) on Real-Time PCR System (Life technology). The mRNA levels were normalized by β-actin. The primer sequences are shown at Table S1.

Western blot analysis

All cell lysates were separated by 10% or 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Then, they were transferred to PVDF membranes. Blocking with 5% skimmed milk powder (BD Pharmingen) for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with specific anti-Arg1 (1: 1,000), anti-TNFα (1: 500), anti-IL1β (1: 1,000), anti-TNFSF15 (1: 1,000) from Abcam, anti-p-p38 MAPK (1: 1,000), anti-p38 MAPK (1: 1,000), anti-p-JNK (1: 1,000), anti-JNK (1: 1,000), anti-p-Erk1/2 (1: 2,000), anti-Erk1/2 (1: 2,000), anti-p-Akt (1: 1,000), anti-Akt (1: 1,000), anti-p-STAT1 (1: 1,000), anti-STAT1 (1: 1,000), anti-p-STAT6 (1: 1,000), anti-STAT6 (1: 1,000), anti-p-STAT3 (1: 1,000), anti-STAT3 (1: 1,000), anti-GADPH (1: 2,000) from Cell Signaling Technology, anti-iNOS (1: 1,000, Introvigen) or anti-β-actin (1: 2,000, ZSGB-BIO) overnight at 4°C. Then the membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Then, protein bands were visualized by ECL Western blot reagent (Bioworld Technology).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software 8.0. Statistical analyses were carried out by using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for univariate and two-way ANOVA for bivariate. Statistical significance is presented as follows: * for P values <.05, ** for P values <.01, and *** for P values <.001.

Results

TNFSF15 promotes M1-like macrophage infiltration into tumors

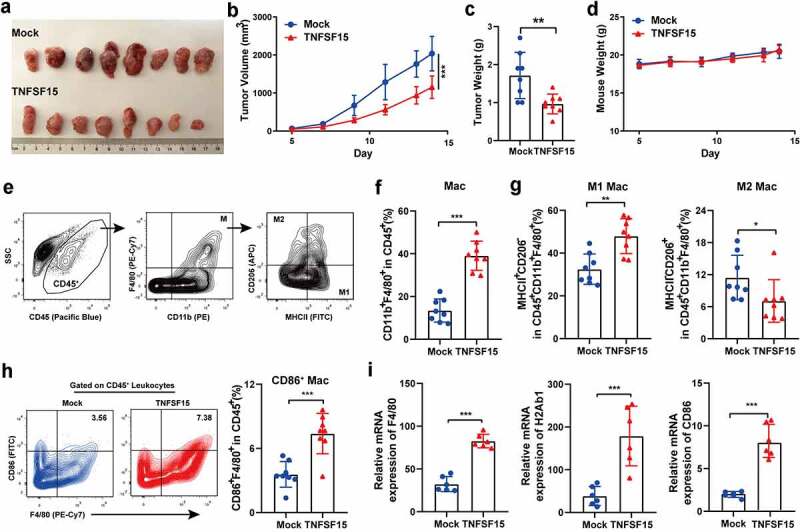

As TNFSF15 gene expression profiles vary in tumors under clinical conditions as well as in experimental models, and appear to be subject to modulations by angiogenic factors or oncogenes,28–30 we prepared murine Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells that stably expressed TNFSF15 and used the cells to establish a tumor model in C57BL/6 mice to investigate the impact of TNFSF15 on tumor-infiltrating macrophages (Fig. S1A-B). In good agreement with previous reports,15,21 TNFSF15-overexpressing tumors exhibited markedly retarded growth, while TNFSF15-overexpression showed little impact on the proliferation rate of the cells in culture (Figure 1a-d and S1C). We then analyzed the macrophage population in the tumors by flow cytometry and found that a 2.9-fold increase of the total macrophages marked as CD11b+F4/80+/CD45+ in TNFSF15-overexpressing tumors (Figure 1e-f). At the same time, to further quantify and distinguish the phenotype of these macrophages, we examined M1 macrophage-related phenotypic markers MHCII, CD86, and M2 macrophage-related phenotypic marker CD20631 (Figure 1e). Remarkably, macrophages in TNFSF15 overexpressing tumors biased M1 phenotype, evident from a 1.5-fold increase in M1 macrophages (MHCII+CD206−), as well as a 40% reduction in M2 macrophage (MHCII−CD206+) compared to those in the control group (Figure 1g). Moreover, macrophages co-expressing CD86 in TNFSF15 overexpressing tumors also increased by 2.1-fold, as compared with that in the control tumors (Figure 1h). In addition, the qPCR data showed that the gene expression levels of F4/80, H2Ab1 (MHCII), and CD86 in the tumor tissues were elevated as the result of TNFSF15 overexpression in the cancer cells; the identities of the individual cells in the tumor microenvironment were not yet discerned at this stage of the investigation, however (Figure 1i). We further determined the expression of a representative inflammatory cytokine, TNFα in macrophages in LLC tumor tissues by immunofluorescence staining. The results showed that the total F4/80 positive macrophage and the TNFα-positive macrophages in TNFSF15 overexpressing tumors increased by 2.5- and 1.8-fold, respectively, as compared to those in the vehicle-treated control group (Fig. S1D). These findings indicate that elevated TNFSF15 level in this tumor model is strongly correlated to a marked increase of the infiltration of M1 macrophages.

Figure 1.

TNFSF15 promotes M1 macrophages infiltration into the tumor. A The picture of TNFSF15-overexpressing LLC tumors (TNFSF15) and the control tumors (Mock) on day 14, n = 8. The volume (b) and weight (c) measurement of TNFSF15 and Mock tumors, n = 8. D The weight of mice was monitored from day 5 to day 14, n = 8. E Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+), M1 macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+MHCII+CD206−), M2 macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+MHCII−CD206+) in tumor. Quantification of the percentages of macrophages within CD45+ fraction (f), M1 macrophages, and M2 macrophages within CD45+CD11b+F4/80+ fraction (g) in TNFSF15 and Mock tumors, n = 8. H Flow cytometric analysis and quantification of CD86+ macrophages within CD45+ fraction in TNFSF15 and Mock tumors, n = 8. I qPCR analysis of gene expression of F4/80, H2Ab1 (MHCII) and CD86 in TNFSF15 and Mock tumor tissues, n = 6. The data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

TNFSF15 augments the phagocytic and pro-apoptotic capacity of the macrophages against cancer cells

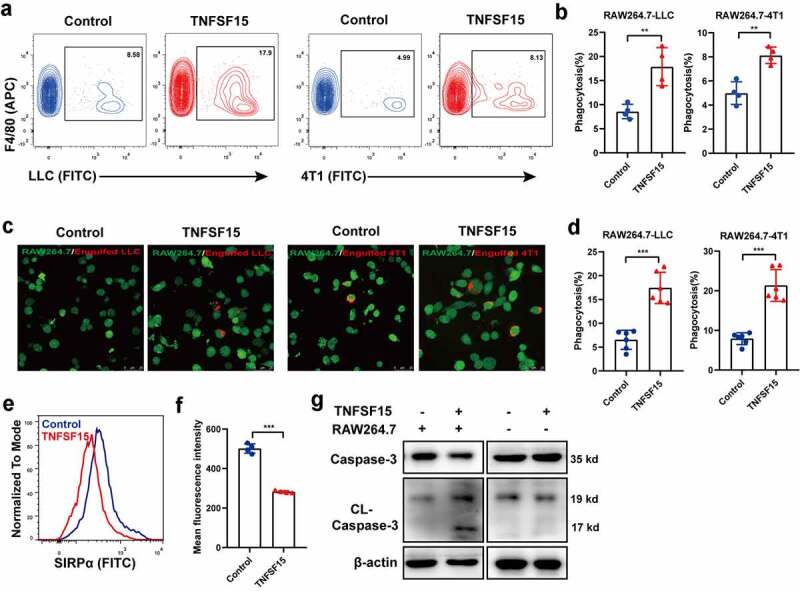

To explore the influence of TNFSF15 on macrophage function, we determined the ability of macrophage phagocytosis to cancer cells. We co-cultured recombinant TNFSF15 (0.5 U) treated murine macrophage cell-line RAW264.7 cells with either LLC or 4T1 (a mouse breast cancer cell line). Flow cytometric results showed that TNFSF15 treatment led to an enhancement of phagocytosis of LLC cells or 4T1 cells by 2.1-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively (Figure 2a-b; the gating strategy for in vitro phagocytosis is given in supplementary Fig. S2A). Moreover, fluorescence microscopic analysis of LLC and 4T1 cancer cells by macrophages demonstrated that TNFSF15-treated macrophages were more capable of engulfing cancer cells, as compared with the capability the vehicle-treated cancer cells (Figure 2c-d). As a number of known phagocytosis “checkpoint”32–34 genes were involved in the modulation of macrophage phagocytosis against cancer cells, we tested the impact of TNFSF15 on SIRPα, PD1 and Siglec-G expression in RAW264.7 cells. We found that TNFSF15-treatment resulted in an inhibition of the gene expression of SIRPα in RAW264.7 cells, but not that of PD1 or Siglec-G (Fig. S2B). We further examined the cell surface levels of SIRPα in RAW264.7 live cells by using flow cytometric analysis, and found that SIRPα protein levels decreased by about 43% following TNFSF15 treatment (Figure 2e-f). Furthermore, we treated LLC cells with either the conditioned media of recombinant TNFSF15-treated RAW264.7 cells, or directly with recombinant TNFSF15, and found that the former treatment gave rise to increased levels of activated caspase-3 in the cancer cells, whereas the latter treatment had no such effect (Figure 2g), indicating an ability of TNFSF15 to promote macrophage-mediated cancer cell apoptosis. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that TNFSF15 treatment leads to an augmentation of the phagocytic and pro-apoptotic capacity of macrophages against cancer cells.

Figure 2.

TNFSF15 augments the phagocytic and pro-apoptotic capacity of the macrophages against cancer cells. Flow cytometric analysis (a) and quantification (b) of the phagocytosis of LLC cells and 4T1 cells by RAW264.7 treated with or without TNFSF15, n = 4. Typical images of phagocytosis of LLC and 4T1 cells by RAW264.7 cells treated with or without TNFSF15 at dedicated time (c) and quantification of image analysis data (d). Scale bar: 25 μm; Green: RAW264.7; Red: Engulfed LLC or 4T1 cells, n = 6. Flow cytometric analysis (e) and quantification (f) of the cell surface levels of SIRPα in RAW264.7 treated with or without TNFSF15, n = 4. G Western blot analysis of caspase3 activation in LLC cells with different treatments. The data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

TNFSF15 promotes bone marrow cell differentiation into M1 macrophage

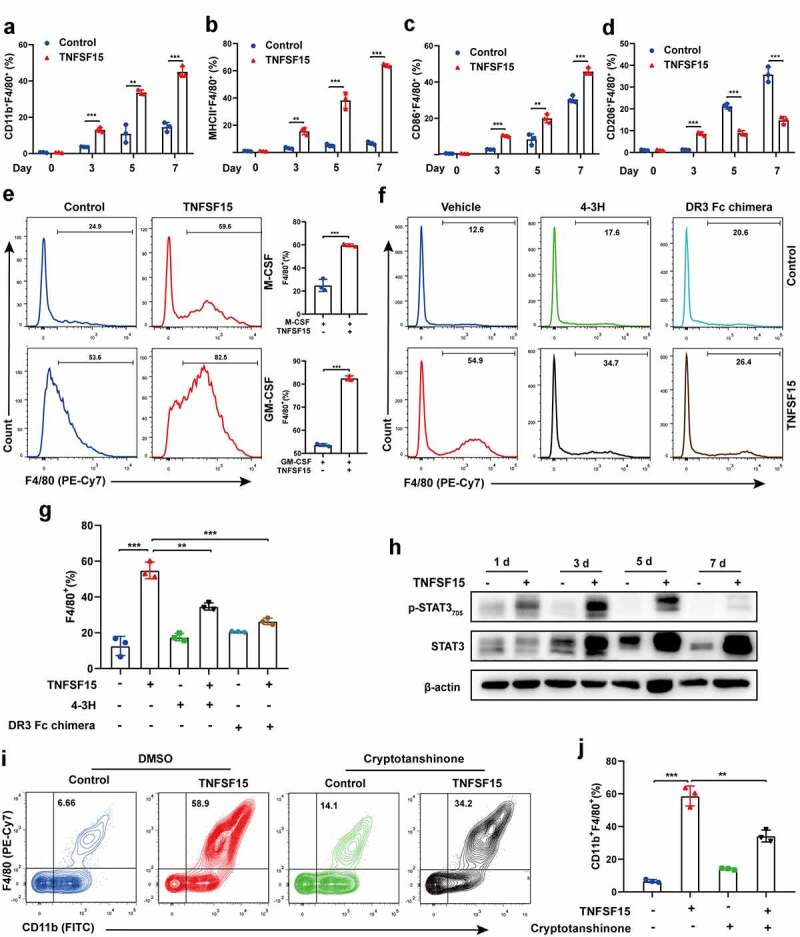

Bone marrow derived macrophage is a critical component of TAM.35 To determine whether bone marrow cells contributed to TNFSF15-mediated M1 macrophages accumulation in tumor, we analyzed the bone marrow cell population in TNFSF15-overexpressing LLC tumor bearing mice. We found that raising TNFSF15 levels in the tumors resulted in significant decreases in the populations of HSC (Lin−-c-Kit+-Sca-1+ hematopoietic stem cell), GMP (granulocyte-macrophage progenitor), and CD115+CD11b+ precursor cells in bone marrow (Fig. S3A). We further implanted LLC tumors on mice that had red fluorescent bone marrow (tdTomato+) and para-tumorally injected the tumors with recombinant TNFSF15 (5 mg/kg, every 3 days). Remarkably, there was a nearly twofold increase of infiltration of the tdTomato+ macrophages in TNFSF15 treated tumors than in the control tumors (Fig. S3B), suggesting an enhancement of TNFSF15 on bone marrow-derived macrophage differentiation and mobilization into tumor. To confirm it, we treated freshly isolated mouse bone marrow cells with recombinant TNFSF15 and found that TNFSF15 treatment resulted in a dose- and time-dependent increase of the percentage of macrophages from bone marrow cells (Figure 3a and S3C), especially that of M1 macrophages such as F4/80+ macrophages co-expressing either MHCII or CD86, up to 9.5-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively, compared to that in the control groups on day 7 (Figure 3b-c). In sharp contrast, the percentage of F4/80+-CD206+ macrophages in TNFSF15-treated group decreased by 59% compared with that in control group on day 7 (Figure 3d). For reasons not yet apparent to us, the percentage of the bone marrow-derived F4/80+-CD206+ cells on day 3 were not as responsive as were the cells on day 5 and day 7 to the inhibitory effect of TNFSF15-treatment, possibly because the cells on day 3 were at an early stage of differentiation toward macrophages under the experimental conditions. Collectively, these results indicate that TNFSF15 is able to induce bone marrow cells to differentiate into M1 macrophages, but not M2 macrophages.

Figure 3.

TNFSF15 induces bone marrow cells to differentiate into M1 macrophages, but not M2 macrophages. Flow cytometric analysis and quantification of the percentages of CD11b+F4/80+ (a) cells, MHCII+F4/80+ cells (b), CD86+F4/80+ cells (c), and CD206+F4/80+ cells (d) differentiated from bone marrow cells with or without TNFSF15 treatment at indicated time points, n = 3. E TNFSF15 and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) or GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) co-cultured bone marrow cells for 5 days. Flow cytometric analysis and quantification of the percentage of F4/80+ cells, n = 3. Flow cytometric analysis (f) and quantification (g) of the percentage of F4/80+ cells differentiated from vehicle- or TNFSF15-treated bone marrow cells in the presence or absence of 4–3 H (0.2 mg/mL) or DR3-Fc chimera (50 μg/mL), n = 3. H Western blotting analysis of STAT3 activation in bone marrow cells following TNFSF15 treatment at indicated time points. Flow cytometric analysis (i) and quantification (j) of the percentage of CD11b+F4/80+ cells differentiated from vehicle- or TNFSF15-treated bone marrow cells in the presence or absence of STAT3 inhibitor, cryptotanshinone, n = 3. The data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Generally, macrophages differentiation and function require colony stimulating factors.36,37 Thus, we further treated bone marrow cell cultures with TNFSF15 in combination with either macrophage colony stimulating factors (M-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factors (GM-CSF). As shown in Figure 3e, the combination treatment resulted in a 2.4-fold and a 1.5-fold increase, respectively, of the percentage of F4/80+ macrophages compared with that treated with M-CSF or GM-CSF alone. We then labeled bone marrow cells with fluorescent CFSE, and found that the fluorescence intensity of TNFSF15-treated macrophages was lower than that of the control cells, suggesting a faster proliferation rate of the former (Fig. S3D). These findings are consistent with the view that TNFSF15 facilitates bone marrow cells-to-macrophage differentiation.

To corroborate these findings, we used two inhibitors of TNFSF15, namely, a TNFSF15 neutralizing antibody 4–3 H,18 and a preparation of DR3 Fc chimera protein containing the extracellular portion of DR3,38 a cell surface receptor of TNFSF15 known to be expressed on bone marrow cells,18 to see if they can block TNFSF15 activities. We found that the presence of either 4–3 H or DR3-Fc chimera in the culture media resulted in an about 50% less increase of the percentage of the differentiated F4/80+ macrophages induced by TNFSF15 (figure 3f-g). Additionally, since we found previously that TNFSF15 is able to activate the transcription activator STAT3 in mouse bone marrow-derived immature dendritic cells,25 we analyzed TNFSF15-treated bone marrow cells and found that STAT3 was also highly activated (Figure 3h). Furthermore, cryptotanshinone, an inhibitor of STAT3 activation, when added to the culture media, inhibited TNFSF15-induced CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages to an extent similar to those achieved with 4–3 H and DR3 Fc chimera (Figure 3i-j). In addition, we found that TNFSF15 activated STAT1, not STAT6 during the process of macrophage differentiation (Fig. S3E). These data support the view that the recombinant TNFSF15 protein has an intrinsic activity to promote macrophage differentiation, and that it is likely that, to a considerable extent, DR3 and STAT-1/3 signaling pathways are involved, giving us a lead into the molecular mechanisms of TNFSF15 actions on macrophages differentiation.

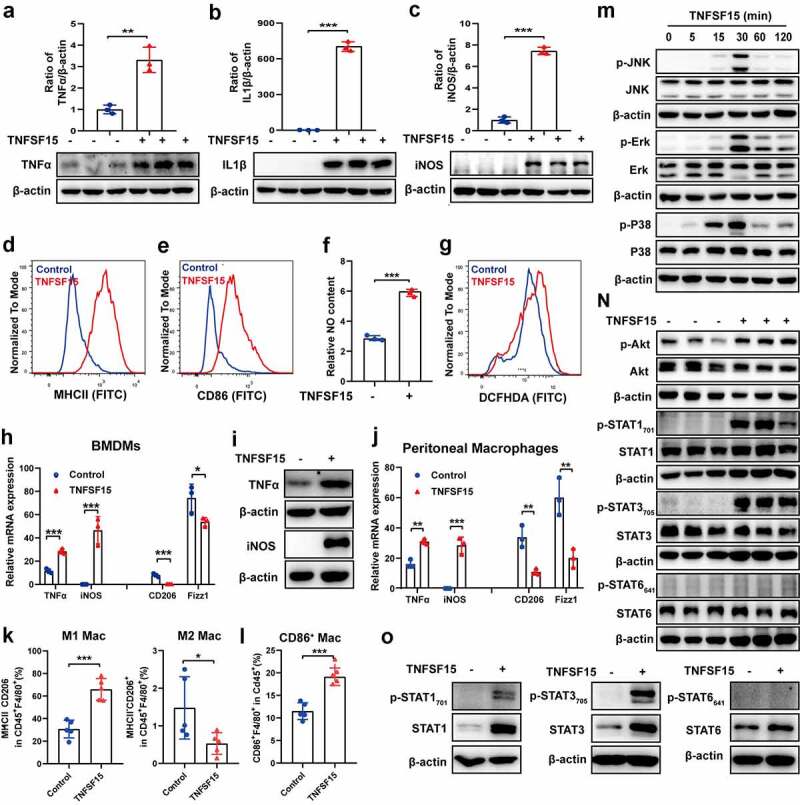

Naive macrophages treated with TNFSF15 polarize toward M1 phenotype

Next, we determined if TNFSF15 was capable of modulating the polarity of mature macrophage toward M1. It was known that RAW264.7 cells assumed as naive macrophages (M0 macrophages)39 and were confirmed in our study (Fig. S4A). To assess the impact of TNFSF15 on naive macrophage, we performed gene transcription level detection and found that TNFSF15 treatment led to an enhancement of M1 markers, including NOS2, TNFα, IL23a, IL1β, MCP-1, IL6, CD80, CD86, NLRP3, Siglec-1 (Fig. S4B). Moreover, we further determined the hallmarks of M1 macrophages in RAW264.7 cells after TNFSF15 treatment. As shown in Figure 4a-E, TNFSF15-treated RAW264.7 cells displayed up-regulated expression of inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL1β and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), accompanied by upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules MHCII, and CD86, consistent with M1 phenotype.4 At the same time, NO in the culture media and ROS inside RAW264.7 cells increased markedly upon TNFSF15 (figure 4f-g). Additionally, we examined iNOS expression in a human monocyte-macrophage cell line, THP-1. We found that, similar to the findings from the mouse cells, TNFSF15 treatment gave rise to markedly enhanced iNOS expression in THP-1 cells (Fig. S4C). These data demonstrate that TNFSF15 is able to facilitate the polarization of naive macrophages toward the M1 phenotype.

Figure 4.

Naive macrophages treated with TNFSF15 polarize toward M1 phenotype. Western blotting analysis and quantification of the protein expression of TNFα (a), IL1β (b), and iNOS (c), as well as flow cytometric analysis of surface expression of MHCII (d) and CD86 (e) in RAW264.7 cells in response to TNFSF15 treatment, n = 3. The relative content of NO (f) and ROS inside RAW264.7 cells (g) with or without TNFSF15 treatment was assayed with Griess reagent and DCFH-DA, respectively, n = 3. qPCR analysis of mRNA levels of M1 markers (TNFα, iNOS) and M2 markers (CD206, Fizz1) (h) and Western blot analysis of protein levels of M1 markers (TNFα, iNOS) (i) in BMDMs in response to TNFSF15 treatment, n = 3. J: qPCR analysis of mRNA levels of M1 markers (TNFα, iNOS) and M2 markers (CD206, Fizz1) in peritoneal macrophages in response to TNFSF15 treatment, n = 3. Flow cytometric quantification of the percentages of M1 macrophages and M2 macrophage within CD45+F4/80+ fraction (k), F4/80+CD86+ peritoneal macrophages within CD45+ fraction (l) from vehicle- and TNFSF15-treated groups upon intra-peritoneal injection of TNFSF15, n = 5. M: Time course of JNK, Erk and P38 phosphorylation in RAW264.7 cells with TNFSF15 treatment. N: Western blot analysis of phosphorylation of Akt, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 in RAW264.7 cells treated with or without TNFSF15 for 24 h. O: Western blot analysis of phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 in BMDM cells treated with or without TNFSF15 for 24 h. The data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

To further assess TNFSF15 mediated M1 macrophage polarization, we carried out analyses of primary macrophages in both cellular and animal models. The in vitro results showed that TNFSF15 treatment resulted in an increase of 2.5- and 5435-fold, respectively, at mRNA levels for TNFα and iNOS in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Figure 4h). The protein levels of these two genes in BMDMs increased significantly as well (Figure 4i; Fig. S4D). Additionally, in peritoneal macrophages, TNFSF15 treatment led to an increase at mRNA levels of 1.9- and 376-fold for TNFα and iNOS, respectively (Figure 4j). On the other hand, the expression of CD206 and Fizz1 genes decreased by 95% and 28% in BMDMs, as well as 68% and 67% in peritoneal macrophages, respectively (Figure 4h, j). Peritoneal macrophages in vivo from wild type mice with intraperitoneal injection of recombinant TNFSF15 also showed a polarization to M1 phenotype, evident by increased MHCII and reduced CD206 expression, as well as a significant increase in CD86+ macrophage (Figure 4k-l and S4E). These findings indicate that the primary macrophages underwent polarization toward M1 upon TNFSF15 treatment.

It has been studied that macrophages express DR3.38,40 We found that, by using Western blotting analysis, DR3 was expressed in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. S4F). We further found that the DR3 Fc chimera was able to prevent TNFSF15-induced upregulation of the expression of iNOS, TNFα, and IL1β, markers associated with M1 macrophages (Fig. S4G). These findings indicate that TNFSF15-DR3 signals are critically involved in macrophage polarization toward M1 phenotype. To further gain insights into the signaling pathways involved in TNFSF15-driven naive macrophage polarization toward M1, we carried out Western blotting analysis in RAW264.7 cells. We found that the three members of MAPK, namely, JNK, Erk1/2, and p38, were phosphorylated within 30 min post TNFSF15 treatment (Figure 4m). P38, JNK, and Erk inhibitors of SB203580, SP600125, and U0126, respectively, were able to block TNFSF15-induced phosphorylation of these protein signals as well as subsequent iNOS and TNFα production (Fig. S4H). Analyses of Akt and STAT1, −3, and −6 signaling pathways were carried out 24 h post TNFSF15 treatment. We found that TNFSF15 treatment resulted in activation of Akt, STAT1, and STAT3, but not STAT6 (Figure 4n). A priori treatment of the cells with inhibitors of Akt or STAT3 inhibitors (either Ly294002 or cryptotanshinone), or STAT1 siRNA, resulted in inhibition of TNFSF15-induced Akt or STAT1/3 activation, and consequently the inhibition of iNOS and TNFα production (Fig. S4I). In addition, we carried out Western blotting analysis of STAT1, −3, and −6 signaling pathway in BMDMs. The results showed that TNFSF15 treatment of BMDMs gave rise to phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3, but not STAT6 (Figure 4o). These findings are consistent with those from RAW264.7 cells. Taken together, these data are consistent with the view that activation of the MAPK, Akt, and STAT1/3 signals is part of the underlying molecular mechanisms in TNFSF15-mediated M1 macrophage development.

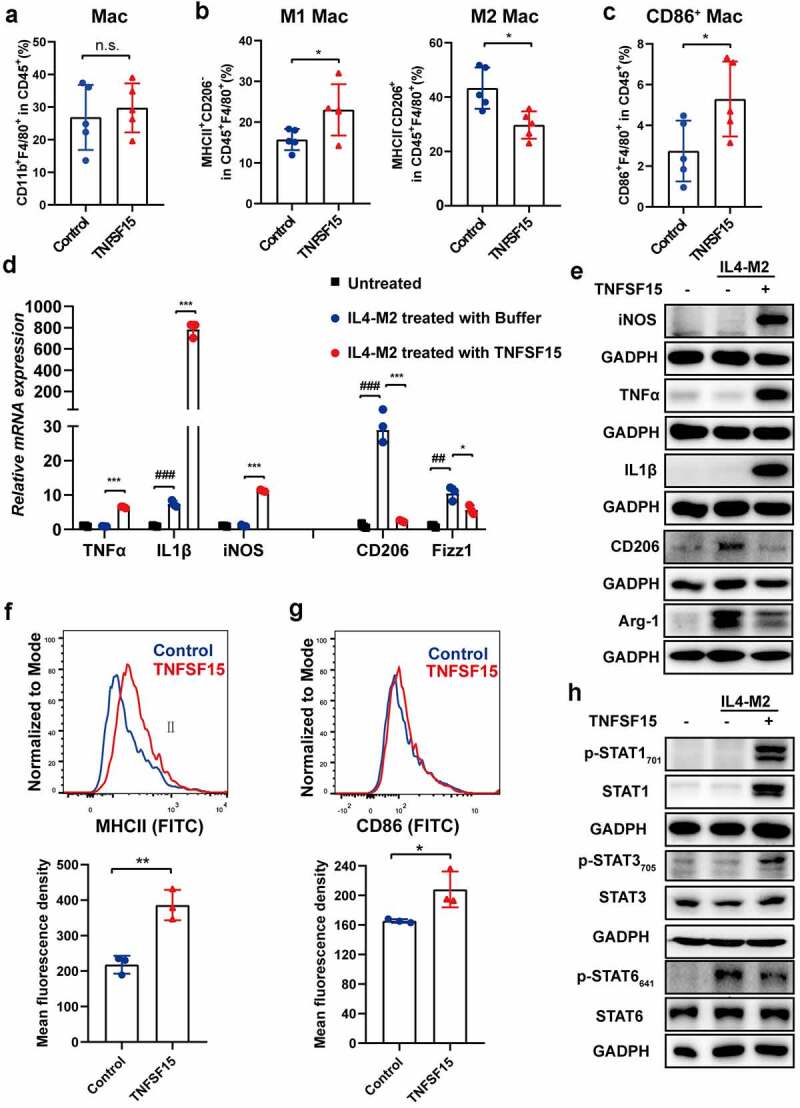

Transition of macrophages from M2 to M1 facilitated by TNFSF15

Tumor-associated macrophages are often domesticated into M2 phenotype.4,41 We further determined whether TNFSF15 was able to convert M2 to M1 phenotypes in tumor. To rule out the influence of TNFSF15-mediated entry of M1 macrophages into tumor, we treated later stage LLC tumor-bearing mice by para-tumoral injection of recombinant TNFSF15 (5 mg/kg, every other day) for a short time (7 days) prior to flow cytometric analyses of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. As expected, we observed that there was no change in the percentage of total macrophages between TNFSF15-treated group and vehicle-treated group (Figure 5a and S5A). Remarkably, M1 macrophages and M2 macrophages in macrophage population in TNFSF15-treated group exhibited a 1.5-fold increase and 31% reduction, respectively, over that in the controls (Figure 5b and S5B). Moreover, the percentage of F4/80+ macrophages co-expressing CD86 in TNFSF15 treated group was 1.9-fold of that in the control group (Figure 5c and S5C). These findings demonstrate that TNFSF15 is capable of facilitating a shift of tumor associated macrophages from M2 phenotype to M1 phenotype. As alternative M2 activation can occur in the presence of IL-4,42 we included this M2-like subtype in our experiments. We first simultaneously treated RAW264.7 cells with TNFSF15 and IL4 for 24 h. The qPCR results showed that TNFSF15 decreased the expression of the IL-4-induced CD206 and Fizz1 mRNA levels, as well as with a significant increase in the mRNA level of TNFα, IL1β and iNOS (Fig. S5D), implying an inhibition of TNFSF15 on M2 polarization of macrophages. Next, we treated RAW264.7 cells with IL4 to induce M2 macrophage (IL4-M2), then with TNFSF15 stimulation. We found that TNFSF15 treatment resulted in upregulation of the mRNA and protein expression of iNOS, TNFα, and IL1β in cells pre-treated with IL4, and at the same time gave rise to a suppression of the mRNA or protein expression of CD206, Arg-1, and Fizz1 (Figure 5d-e). Additionally, TNFSF15 treatment of IL4- conditioned M2 macrophages resulted in highly upregulated MHCII and CD86 expression (figure 5f-g), indicating restoration of antigen presentation ability in these cells.

Figure 5.

Transition of macrophages from M2 to M1 facilitated by TNFSF15. Flow cytometric quantification of the percentages of macrophages within CD45+ fraction (a), M1 macrophages, and M2 macrophages within CD45+F4/80+ fraction (b), as well as CD86+ macrophages within CD45+ fraction (c) in tumors from vehicle- and TNFSF15-treated groups upon para-tumoral injection of TNFSF15, n = 5. Changes of mRNA (d) or protein (e) levels of iNOS, TNFα, IL1β, CD206, Arg-1 and Fizz1 in IL4 induced M2 macrophages in response to TNFSF15 were determined by qPCR or Western blotting, n = 3. Flow cytometric analysis and quantification of surface expression of MHCII (f) and CD86 (g) in IL4 induced M2 macrophages with and without TNFSF15 treatment, n = 3. H Western blotting analysis of STAT1, STAT3 and STAT6 activation in IL4 induced M2 macrophages following TNFSF15 treatment. The data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, n.s. no significance, #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001.

Next, we explored the molecular mechanisms of TNFSF15 stimulation of M2 macrophage polarization toward M1. We found that TNFSF15 treatment gave rise to activation of STAT1 and STAT3 signal pathways as well as deactivation of STAT6 signal pathway in IL-4-conditioned M2 macrophages (Figure 5h). The data suggest that TNFSF15 be capable of re-directing macrophages from tumor-promoting M2 to tumor-inhibiting M1, and that alterations of STAT1, STAT3 and STAT6 signaling pathways be involved the regulations.

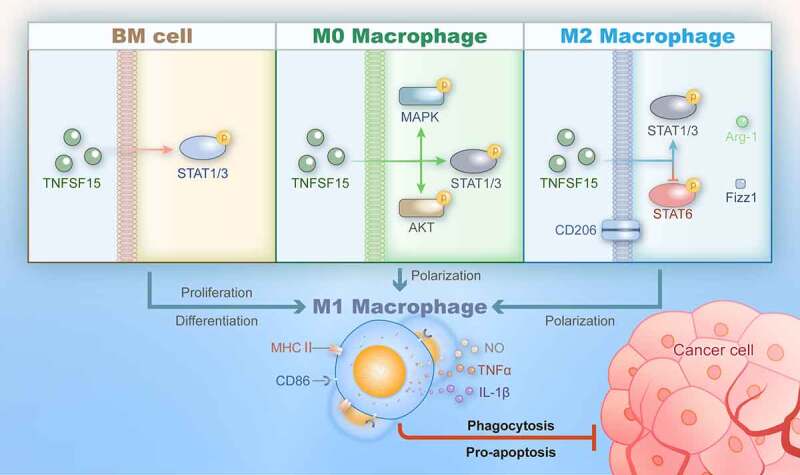

Discussion

Since the abundance of TAMs in tumor is correlated with poor cancer prognosis, significant attention has been drawn toward development of cancer immunotherapies targeting these TAMs.43,44 In present study, we found that TNFSF15 leads to an enrichment of M1 macrophages in tumors via various pathway, which in turn results in a reconstruction of the tumor immunomicroenvironment in favor of tumor inhibition (Figure 6). Specifically, TNFSF15 actions on macrophages are three folds: Firstly, it promotes bone marrow cells to differentiate into M1 macrophages, mediated by STAT1/3 activation. Secondly, it facilitates naive (M0) macrophages to differentiate and polarize into M1 macrophages, via activation of MAPK, Akt and STAT1/3 signaling pathways. Thirdly, it enables a conversion of M2 macrophages, including those associated with tumors, to polarize into M1 macrophages, mediated by the activation of STAT1/3 and deactivation of STAT6 signals.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of TNFSF15-facilitated differentiation and polarization of macrophages of various origins toward the M1 phenotype with tumor suppression activities.

Consistent with previous reports, we confirm the antitumor efficacy of TNFSF15 in Lewis lung carcinoma.15,21 Notably, our findings indicate that the anticancer activity of TNFSF15 also partly depends to an accumulation of M1 macrophages. Many studies suggest that re-programming M2 TAM to M1 TAM is accompanied by augmented recruitment and activation of CD8+ T cells with enhanced antitumor activities.14,45,46 Our finding demonstrates that TNFSF15 actions not only convert M2 TAMs into the M1 phenotype, but also facilitate M1 macrophages infiltration into tumors, which blocks TAMs pro-tumoral functions and enhances their tumoricidal properties.

TAM can descend from bone marrow derived monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages of embryonic origin.47,48 One report demonstrated that bone marrow-derived monocytes-preferentially replenish M1 macrophages with more potent ability of antigen presentation and inflammation response.49 We show here that TNFSF15 is able to facilitate bone marrow cells differentiation into M1 macrophages in cell cultures, as well as to promote bone marrow-derived macrophage infiltration into tumors. Generally, macrophages can undergo differentiation from bone marrow cells into naive macrophages, and are then stimulated by environmental factors to present the M1 or M2 phenotype. Our finding that TNFSF15 drives macrophages at different stages toward M1 phenotype may have important implications in cancer immunotherapy. Conceivably, one may be able to use TNFSF15 for ex vivo expansion of bone marrow-derived macrophages, or peritoneal macrophages from a cancer patient, to proliferate and polarize into M1 macrophages, and use the latter for the treatment of the same patient.

A complex signaling pathway are required to develop TNFSF15 mediated M1 macrophage. In some report, MAPK, and Akt are involved in TNFSF15 activities on myeloid-derived cells and human monocyte derived macrophages, giving a strong support for our study.27,38 STAT1 and STAT3 are the members of the STAT transcription factor family, which are keys to the regulation of macrophage activity.50 Moreover, the finding that TNFSF15 facilitated transition of macrophages from M2 to M1 via the activation of STAT1 and deactivation of STAT6 signals is in line with the role of STAT1 and STAT6 signals in macrophage polarization,51,52 indicating that TNFSF15 may act as an antagonist of M2 macrophage induction factor.

There is a recent report that treatment of a mouse Hep1-6 tumor model with a preparation of recombinant human TNFSF15 (rhVEGI-251) results in elimination of TAM in about four weeks post cancer cell inoculation.40 It has been shown that, in a murine model of urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis, lung macrophages develop increased M1 macrophage marker expression during the first 2–3 weeks, follow by increased M2 markers expression by week 6.53 Since the time windows we used in this study was about two weeks, it would seem plausible that the suppression of M2 TAM by TNFSF15 that we observed is in agreement with the findings that TNFSF15 could suppress M2 TAM in later stages of tumor development.40 In addition, there is a remaining question worthy of further investigation. It has been reported that TNFSF15 promotes the co-activation of T cells,16 the maturation of DC cells,25 and the enhancement of the toxicity of NK cells.26 Considering that various types of cells in tumors can express DR3,54,55 it cannot at this stage of the investigation be definitely excluded that, in response to TNFSF15, signals from other cells in the tumor microenvironment are involved indirectly in the promotion of macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype.

We previously studied that the expression of TNFSF15 gene is nearly completely suppressed in tumors by angiogenesis-promoting genes such as VEGF.28 Some studies suggest that M2 TAMs contribute to establishment blood vessels,56,57 whereas the M1 subtype suppress angiogenesis.58 Therefore, depletion of anti-angiogenic TNFSF15 in tumors may have contributed considerably to unchecked predominance of M2 TAM and blood vessel. It makes sense if we can use various preparations of TNFSF15, whether they be recombinant proteins or genetic materials, to deliver active TNFSF15 into tumors to stimulate the transition of M2 TAM to M1 macrophages and inhibit angiogenesis, achieving dual suppression for tumor growth. In addition to cancers, our new findings that TNFSF15 acts to promote M1 macrophages may help to develop the treatment strategies for M2 macrophage-related diseases, such as asthma, fibrosis, and parasitic infections.

In summary, we demonstrate in this study that TNFSF15 is able to promote the differentiation and polarization of macrophages toward tumor-killing M1 phenotype. Additionally, we identify some of the signaling pathways that take part in the mediation of TNFSF15 actions. These findings may have important implications in the reconstruction of cancer immuno-microenvironment in favor of cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073233, 82073064, 81874167).

Abbreviations

TNFSF15: tumor necrosis factor superfamily-15; DR3: death receptor 3; LLC: Lewis lung cell; CM: conditioned medium; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; NO: nitric oxide; CD206: cluster of differentiation 206; Arg-1: Arginase-1; Fizz1: found in inflammatory zone 1; MHCII: major histocompatibility complex class II; CD86: cluster of differentiation 86; SIRPα signal-regulatory protein alpha; PD-1: Programmed cell death protein 1; Siglec-G: sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin G; TAMs: tumor-associated macrophages; BM: bone marrow; EPC: endothelial progenitor cells; DR3: Death receptor 3

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with the guides given by Institute Research Ethics Committee of Nankai University, for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

References

- 1.Torre L, Bray F, Siegel R, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A.. Global cancer statistics, 2012 [J]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–12. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinshaw D, Shevde L. The Tumor Microenvironment Innately Modulates Cancer Progression [J]. Cancer Res. 2019;79(18):4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chittezhath M, Dhillon M, Lim J, Laoui D, Shalova I, Teo YL, Chen J, Kamaraj R, Raman L, Lum J, et al. Molecular profiling reveals a tumor-promoting phenotype of monocytes and macrophages in human cancer progression [J]. Immunity. 2014;41(5):815–829. doi 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray P, Allen J, Biswas S, Fisher E, Gilroy D, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton J, Ivashkiv L, Lawrence T, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines [J]. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmall A, Al-Tamari H, Herold S, Kampschulte M, Weigert H, Wietelmann A, Vipotnik N, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Pullamsetti S, et al. Macrophage and cancer cell cross-talk via CCR2 and CX3CR1 is a fundamental mechanism driving lung cancer [J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(4):437–447. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1137OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruffell B, Coussens Lisa M. Macrophages and Therapeutic Resistance in Cancer [J]. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas [J]. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(3):787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Palma M, Lewis C. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies [J]. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNardo D, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy [J]. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(6):369–382. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Xie J, Fiskesund R, Dong W, Liang X, Lv J, Jin X, Liu J, Mo S, Zhang T, et al. Chloroquine modulates antitumor immune response by resetting tumor-associated macrophages toward M1 phenotype [J]. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):873. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travers M, Brown S, Dunworth M, Holbert C, Wiehagen K, Bachman K, Foley J, Stone M, Baylin S, Casero R, et al. DFMO and 5-Azacytidine Increase M1 Macrophages in the Tumor Microenvironment of Murine Ovarian Cancer [J]. Cancer Res. 2019;79(13):3445–3454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohri C, Shikotra A, Green R, Waller D, Bradding P. Macrophages within NSCLC tumour islets are predominantly of a cytotoxic M1 phenotype associated with extended survival [J]. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(1):118–126. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeni E, Mazzetti L, Miotto D, Cascio N, Maestrelli P, Querzoli P, Pedriali M, Rosa E, Fabbri L, Mapp C, et al. Macrophage expression of interleukin-10 is a prognostic factor in nonsmall cell lung cancer [J]. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(4):627–632. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00129306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrido-Martin E, Mellows T, Clarke J, Ganesan A-P, Wood O, Cazaly A, Seumois G, Chee SJ, Alzetani A, King EV, et al. M1 hot tumor-associated macrophages boost tissue-resident memory T cells infiltration and survival in human lung cancer. J Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000778. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhai Y, Jian N, Jiang G, LU J, Xing L, Lincoln C, Carter KC, Janat F, Kozak D, XU S, et al. VEGI, a novel cytokine of the tumor necrosis factor family, is an angiogenesis inhibitor that suppresses the growth of colon carcinomas in vivo. Faseb J Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biol. 1999;13(1):181–189. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Migone T, Zhang J, Luo X, Zhuang L, Chen C, Hu B, Hong JS, Perry JW, Chen S-F, Zhou JXH, et al. TL1A is a TNF-like ligand for DR3 and TR6/DcR3 and functions as a T cell costimulator [J]. Immunity. 2002;16(3):479–492. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew L, Pan H, Yu J, Tian S, Huang W, Zhang J, Pang S, Li L. A novel secreted splice variant of vascular endothelial cell growth inhibitor [J]. FASEB J. 2002;16(7):742–744. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0757fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi JW, Qin TT, Xu LX, Zhang K, Yang G-L, Li J, Xiao H-Y, Zhang Z-S, Li L-Y. TNFSF15 inhibits vasculogenesis by regulating relative levels of membrane-bound and soluble isoforms of VEGF receptor 1 [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(34):13863–13868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304529110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Tian S, Metheny-Barlow L, Chew L-J, Hayes AJ, Pan H, Yu G-L, Li L-Y. Modulation of Endothelial Cell Growth Arrest and Apoptosis by Vascular Endothelial Growth Inhibitor [J]. Circ Res. 2001;89(12):1161–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian F, Liang P, Li L. Inhibition of endothelial progenitor cell differentiation by VEGI [J]. Blood. 2009;113(21):5352–5360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou W, Medynski D, Wu S, Lin X, Li L. VEGI-192, a new isoform of TNFSF15, specifically eliminates tumor vascular endothelial cells and suppresses tumor growth [J]. Clinical Cancer Res. 2005;11(15):5595–5602. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagome S, Takeyama Y, Mano S, Sakisaka S, Matsui T, Kawamura S, Oota H. Population-specific susceptibility to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; dominant and recessive relative risks in the Japanese population [J]. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74(2):126–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassatella M, Pereira-da-silva G, Da Silva G, Facchetti F, Scapini P, Calzetti F, Tamassia N, Wei P, Nardelli B, Roschke V, et al. Soluble TNF-like cytokine (TL1A) production by immune complexes stimulated monocytes in rheumatoid arthritis [J]. J Immunology. 2007;178(11):7325–7333. Baltimore, Md: 1950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang L, Adkins B, Deyev V, Podack E. Essential role of TNF receptor superfamily 25 (TNFRSF25) in the development of allergic lung inflammation [J]. J Exp Med. 2008;205(5):1037–1048. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian F, Grimaldo S, Fujita M, Cutts J, Vujanovic NL, Li L-Y. The endothelial cell-produced antiangiogenic cytokine vascular endothelial growth inhibitor induces dendritic cell maturation [J. J Immunology. 2007, Baltimore, Md: 1950;179(6):3742–3751. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidemann S, Chavez V, Landers C, Kucharzik T, Prehn JL, Targan SR. TL1A selectively enhances IL-12/IL-18-induced NK cell cytotoxicity against NK-resistant tumor targets [J]. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(4):531–538. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun R, Hedl M, and Abraham C. TNFSF15 Promotes Antimicrobial Pathways in Human Macrophages and these are Modulated by TNFSF15 Disease-Risk Variants [J]. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021; 11(1): 249–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng W, Gu X, Lu Y, Gu C, Zheng Y, Zhang Z, Chen L, Yao Z, Li L-Y. Down-modulation of TNFSF15 in ovarian cancer by VEGF and MCP-1 is a pre-requisite for tumor neovascularization [J]. Angiogenesis. 2012;15(1):71–85. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9244-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang N, Sanders A, Ye L, Kynaston H, Jiang W. Vascular endothelial growth inhibitor, expression in human prostate cancer tissue and the impact on adhesion and migration of prostate cancer cells in vitro [J]. Int J Oncol. 2009;35(6):1473–1480. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang N, Sanders A, Ye L, Kynaston H, Jiang W. Expression of vascular endothelial growth inhibitor (VEGI) in human urothelial cancer of the bladder and its effects on the adhesion and migration of bladder cancer cells in vitro [J]. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosser D, Edwards J. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation [J]. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majeti R, Chao M, Alizadeh A, Pang W, Jaiswal S, Gibbs K, Rooijen N, Weissman I . CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells [J]. Cell. 2009;138(2):286–299 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon S, Maute R, Dulken B, Hutter G, George BM, McCracken MN, Gupta R, Tsai JM, Sinha R, Corey D, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity [J]. Nature. 2017;545(7655):495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barkal A, Brewer R, Markovic M, Kowarsky M, Barkal S, Zaro B, Krishnan V, Hatakeyama J, Dorigo O, Barkal L, et al. CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy [J]. Nature. 2019;572(7769):392–396. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laviron M, Boissonnas A. Ontogeny of Tumor-Associated Macrophages [J]. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1799. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mossadegh-Keller N, Sarrazin S, Kandalla P, Espinosa L, Stanley ER, Nutt SL, Moore J, Sieweke MH. M-CSF instructs myeloid lineage fate in single haematopoietic stem cells [J]. Nature. 2013;497(7448):239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helft J, Böttcher J, Chakravarty P, Zelenay S, Huotari J, Schraml B, Goubau D, Reis e sousa C. GM-CSF Mouse Bone Marrow Cultures Comprise a Heterogeneous Population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) Macrophages and Dendritic Cells [J]. Immunity. 2015;42(6):1197–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedl M, and Abraham C. A TNFSF15 disease-risk polymorphism increases pattern-recognition receptor-induced signaling through caspase-8-induced IL-1 [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(37): 13451–13456 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404178111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi Y, Luo P, Wang W, Horst K, Greven J, Relja B, Xu D, Hildebrand F, Greven J. M1 But Not M0 Extracellular Vesicles Induce Polarization of RAW264.7 Macrophages Via the TLR4-NFκB Pathway In Vitro [J]. Inflammation. 2020;43(5):1611–1619. doi: 10.1007/s10753-020-01236-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong X, Huang X, Yao Z, Wu Y, Chen D, Tan C, Lin J, Zhang D, Hu Y, Wu J, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages as a novel target of VEGI-251 in cancer therapy [J]. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(14):7884–7895. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cassetta L, Pollard J. Tumor-associated macrophages [J]. Current Biology: CB. 2020;30(6):R246–R8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Junttila I, Mizukami K, Dickensheets H, Meier-Schellersheim M, Yamane H, Donnelly R, Paul W . Tuning sensitivity to IL-4 and IL-13: differential expression of IL-4Ralpha, IL-13Ralpha1, and gammac regulates relative cytokine sensitivity [J]. J Exp Med. 2008;205(11):2595–2608. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ngambenjawong C, Gustafson H, and Pun S. Progress in tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-targeted therapeutics [J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;114:206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang I, Kim J, Ylaya K, Chung E, Kitano H, Perry C, Hanaoka J, Fukuoka J, Chung J, Hewitt S . Tumor-associated macrophage, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis markers predict prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer patients [J]. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):443. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cassetta L, Pollard J. Repolarizing macrophages improves breast cancer therapy [J]. Cell Res. 2017;27(8):963–964. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cassetta L, Pollard J. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer [J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(12):887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowman R, Klemm F, Akkari L, Pyonteck SM, Sevenich L, Quail DF, Dhara S, Simpson K, Gardner EE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al. Macrophage Ontogeny Underlies Differences in Tumor-Specific Education in Brain Malignancies [J]. Cell Rep. 2016;17(9):2445–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann D, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression [J]. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(1):20–27. doi: 10.1038/nn.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu Y, Herndon J, Sojka D, Kim K-W, Knolhoff BL, Zuo C, Cullinan DR, Luo J, Bearden AR, Lavine KJ, et al. Tissue-Resident Macrophages in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Originate from Embryonic Hematopoiesis and Promote Tumor Progression [J]. Immunity. 2017;47(3):597. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Watowich S. Innate immune regulation by STAT-mediated transcriptional mechanisms [J]. Immunol Rev. 2014;261(1):84–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varinou L, Ramsauer K, Karaghiosoff M, Kolbe T, Pfeffer K, Müller M, Decker T. Phosphorylation of the Stat1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity [J]. Immunity. 2003;19(6):793–802. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang H, Harris M, Rothman P. IL-4/IL-13 signaling beyond JAK/STAT [J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(1063–70):1063–1070. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.107604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaynagetdinov R, Sherrill T, Polosukhin V, Han W, Ausborn JA, McLoed AG, McMahon FB, Gleaves LA, Degryse AL, Stathopoulos GT, et al. A critical role for macrophages in promotion of urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis. J Immunology. 2011;187(11):5703–5711. Baltimore, Md: 1950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strizova Z, Snajdauf M, Stakheev D, Taborska P, Smrz D, Biskup J, Lischke R, Bartunkova J, Smrz D. The paratumoral immune cell signature reveals the potential for the implementation of immunotherapy in esophageal carcinoma patients [J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(8):1979–1992. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cavallini C, Lovato O, Bertolaso A, Zoratti E, Malpeli G, Mimiola E, Tinelli M, Aprili F, Tecchio C, Perbellini O, et al. Expression and function of the TL1A/DR3 axis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia [J]. Oncotarget. 2015;6(31):32061–32074. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qian B, Pollard J. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis [J]. Cell. 2010;141(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S, Kim J, Papadopoulos J, Kim S, Maya M, Zhang F, He J, Fan D, Langley R, Fidler I . Circulating monocytes expressing CD31: implications for acute and chronic angiogenesis [J]. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(5):1972–1980. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan A, Hsiao YJ, Chen HY, Chen H-W, Ho -C-C, Chen -Y-Y, Liu Y-C, Hong T-H, Yu S-L, and Chen JJW, et al. Opposite Effects of M1 and M2 Macrophage Subtypes on Lung Cancer Progression [J]. Sci Rep. 2015;5(14273). doi: 10.1038/srep14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.