Abstract

Introduction

Khat is a flowering plant with stimulant effect on the nervous system and produce psychological dependence. Despite its harmful effects, the ingestion of khat has been part of cultural norms and the legality of khat varies by region.

Objective

This systematic review aimed at critically evaluating the available evidence on the risk factors of khat chewing among adolescents.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted on published research studies from five databases Scopus, PubMed, Science-direct, Ovid and google scholar using keywords khat chewing OR qat chewing AND associated factors OR risk factors OR contributing factors AND adolescents OR teenagers. Articles included were either cross-sectional, cohort, case-control or qualitative studies which were published between the year 1990 till present. Excluded articles were the non-English written articles, descriptive studies and irrelevant topics being studied.

Results

Out of 2617 records identified and screened, six were included for the analysis and interpretation of the data. All included studies were cross-sectional study design. All six studies reported having family members who chewed khat significantly predict khat chewing among adolescents, followed by five articles for friends or peers who also chewed khat and four articles for male gender. Smoking was also found to have the highest odds (OR = 18.2; 95% CI: 12.95–25.72) for khat chewing among adolescents.

Conclusion

The review highlights the crucial role of family members, friends or peers and male gender to predict khat chewing among adolescents. Effectiveness of health promotion programs to educate and reduce khat chewing among adolescents will require active participation of family members and friends.

Introduction

Khat is also called qat, jaad or qaad is a flowering plant native to Ethiopia which produces effects analogous to those of amphetamine causing raising concerns about the health and social consequences. Khat chewing has been a common practice for many years in the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula where the khat plant is widely cultivated and known by a variety of names, including qaat and jaad in Somalia, and chat in Ethiopia [1] ((Al-Mugahed, 2008).

High prevalence of khat chewing has been reported in several countries, between 23.1% and 30.3% in Saudi Arabia [2] (Mahmoud et al., 2017) and from 6.95% to 64.9% in Oromia and Amhara regions respectively in the Ethiopia [3] (Astatkie et al., 2015), which was mainly related to spiritual [4] (Sikiru Lamina, 2010) and cultural [5] (Armstrong, 2008). Increasing intake among younger age groups as part of daily habit has also been reported [6] ((Mathewson et al., 2013). The beliefs that khat may enhance concentration [7] (Richard Hoffman & Mustafa al’Absi, 2011), performance motivation and strengthen their socialization, attract many adolescents of high schools and secondary school students to consume khat [8] (Meressa Kalayu et al., 2009).

The amphetamine-rich nature of khat leaves resulted in symptoms such as tachycardia, hyperthermia, dryness of the month, tachypnoea, mydriasis, and restlessness [9] (Dhaifalah & Santavý, 2004). Chronic ingestion of khat exposes the chewers to thrombocytosis, which may lead to myocardial infarction [10] (Al-Motarreb et al., 2002), ischemic heart disease, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmia [11] (Mega & Dabe, 2017), manic-like schizophrenia and distress secondary to withdrawal [12] (Alemu et al., 2020). Other reported adverse effects include erectile dysfunction [13] (Hassan, Gunaid & Murray Lyon, 2007), involvement in unsafe sex [14] (Lifson et al., 2017), psychotic experiences [15] (Odenwald & Khatkonsum, 2008), oesophageal cancer [16] (Bozzuto, Ruggieri & Molinari, 2010), low birth weight [17] (Khawaja Al-Nsour & Saad, 2008) among pregnant mother chewers, and lactation problem [18] (Glenice & Hagen, 2003) postnatally. Diverse risk factors have been observed across studies reflecting the cultural components to the risks of khat chewing among adolescents, with better understanding on the underlying risks needed in order for effective preventive and promotive intervention to be implemented. In view of its potential health, social and economic risks as well as the worrying prevalence among adolescents age group, this review is aimed to determine the risk factors of khat chewing among adolescents.

Materials and methods

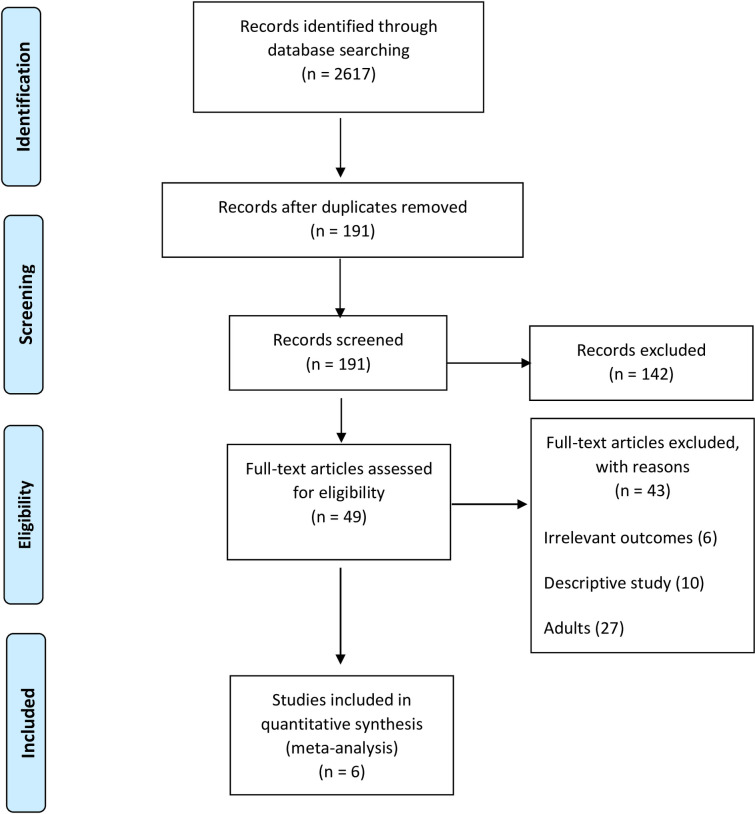

The review was conducted and reported in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Fig 1) [19] (Moher et al., 2009).

Fig 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Eligibility criteria

Articles included were observational studies either cross-sectional, cohort or case-control studies and qualitative studies with publication period from the year 2010 to 2020. We excluded studies conducted among the non-adolescents age group, non-English language, descriptive studies, and protocols. Articles with irrelevant topics being studied and official reports from government agencies were also excluded. Khat chewing refers to the consumption of the leaves and stem tips of a flowery plant known as khat, which produced stimulating effect due to its amphetamine like effects [20] (Teferra, Hanlon & Jacobsson, 2011).

Data sources and search strategy

We systematically searched for relevant articles published using five electronic databases from inception to June 2020, which included Scopus, PubMed, Science-direct, Ovid, and Google Scholar to retrieve studies of potential interest. The literature search was undertaken from five different databases using a combination of keywords of khat chewing OR qat chewing AND associated factors OR risk factors OR contributing factors AND adolescents OR teenagers.

Study selection

Four researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each study was recorded as include, exclude, or unclear. The full articles were retrieved for those recorded as include or unclear for further assessment, and the decision was made accordingly. Any discrepancies in the assessment were resolved by discussion leading to a consensus. According to the extensive basic and advance search of five databases with regards to the restricted inclusion and exclusion criteria, only these articles were found to be eligible to this study.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction from all potential studies was documented in a table. The table included information on study design, study location, sample size, objective of the studies and major findings–risk factors associated with khat chewing among adolescents. Results selected to be included in the review had to possess specific measure estimates either calculated crude odds ratio, adjusted odds ratio, relative risk ratio, standardized beta coefficient with 95% confidence interval that does not include one or a p-value of less than 0.05 to have a significant factor included. Since the inclusion criteria of this study was to use multivariate.

The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) was used to assess the methodological quality of the selected articles. The CCAT examined the study based on eight criteria which included preliminaries, introduction, design, sampling, data collection, ethical matters, result, discussion, and conclusion. The total score was then converted into percentage whereby the following categories were assigned to allow for comparison; poor quality (≤50%), acceptable quality (51–74%), high quality (≥75%) [21] (Crowe, Sheppard & Campbell, 2011).

Results

Study selection

A total of 2617 records were identified through five databases searching. After reviewing the titles and abstracts only 191 articles were included for further screening. Of those remaining, 142 articles were excluded due to non-English language, irrelevant outcomes, and study of substances other than khat. Forty-nine full text articles were screened, of which another 43 articles were excluded for the following reasons: non-adolescents study population, irrelevant outcomes, and descriptive studies. Finally, only six studies were included in this review [22–27] (Agili et al., 2018; Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013; Reda et al., 2012), upon strict evaluation based on the predetermined eligibility criteria. Fig 1 shows PRISMA flowchart.

Quality assessment

The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) was used to assess the methodological quality of observational studies. The CCA tool consists of eight categories which is Preliminary, introduction, design, sampling, data collection, ethical matters, results, discussion, and conclusion. Each item has multiple items that simplify to score. Each category had scored 0–5 points. The total score was converted into percentage [28] (Akinla, Hagan & Atiomo, 2018). Quality assessments for each study was conducted using Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool. An established instrument used in assessing the quality of observational studies. Four studies were reported to be high quality while the other two were reported as acceptable quality as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool quality assessment.

| Category | [25] | [23] | [22] | [27] | [24] | [26] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Preliminary | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. | Introduction | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3. | Design | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4. | Sampling | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 5. | Data Collection | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. | Ethics | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 7. | Results | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 8. | Discussion | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 9. | Total score (/40) | 29 | 34 | 27 | 33 | 31 | 35 |

| 10. | Percentage | 73% | 85% | 68% | 83% | 78% | 88% |

Characteristics of included studies

All articles included in this review were cross-sectional studies, with a total of 12157 participants were included in this study, dominated by high and secondary school students (Table 2). The studies were conducted between the year 2013 to 2018. Half of the included studies were conducted in Ethiopia while the other half were conducted in Saudi Arabia. All included articles employed probability sampling with randomization ensured during recruitment of respondents. Five out of six studies were only reporting the dependent and independent variables, except for a study by [25] (Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017) reported sex, living status during school age, and parental education level being the covariates involved in the study, with all included articles reported OR and 95% CI values.

Table 2. Factors associated with Khat chewing among adolescents.

| No. | Authors/ year | Study objective | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | [23] | To investigate the prevalence of Khat chewing and related factors among intermediate and high school students of Jazan region. | Study design = Cross-sectional | Male, OR = 10.1 (95% CI: 4.88–17.38); Smoking, OR = 18.2 (95% CI: 12.95–25.72); Friend chewing khat, OR = 4.43 CI (2.78–7.37); Fathers chewing khat, OR = 1.68 CI (1.22–2.31); Brother chewing khat, OR = 2.65 CI (1.93–3.65) |

| Population and size = 3764 intermediate or higher secondary school students during the academic year 2011/2012, aged13–21 years. | ||||

| Place = Jazan Region Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Study Instrument = A standardized questionnaire with pilot study of 160 students | ||||

| Analysis = Epi Info and SPSSV 17 Sampling = three-stage cluster random sampling | ||||

| Khat use measured using Lifetime and current use of Khat | ||||

| 2. | [27] | To assess khat chewing among school adolescents in Harar town, eastern Ethiopia | Study design = Cross-sectional study design | Male gender, OR = 2.10 (95% CI: 1.50–2.93); Muslim religion, OR = 1.88 (95% CI: 1.17–3.04); Having friends who chewed khat, OR = 7.93 (95% CI 5.40–11.64); Availability of someone with a similar habit in the family, OR = 1.50 (95% CI: 1.07–2.11) |

| Population = 1,890 secondary school students Place = Harar town Ethiopia | ||||

| Study instrument = A self-administered structured questionnaire | ||||

| Analysis = SPSS V15 | ||||

| Sampling = stratified sampling technique | ||||

| Khat use measure using history of khat use | ||||

| 3. | [24] | To establish the prevalence of khat chewing and associated factors among Ataye high school students and preparatory school students. | Study design = Cross-sectional | Male students, OR = 2.15 (95% CI: 1.02, 4.56); Peer chew Khat, OR = 3.14 (95% CI: 1.53, 6.41); Family chew Khat, OR = 2.68 (95% CI: 1.13, 6.37); Place of residency(urban), OR = 1.89 (95% CI: 1.0, 3.79) |

| Population and size = 378 Ataye high school students | ||||

| Population = Northern Shoa, Ethiopia | ||||

| Study instrument = self-administered structured questionnaire | ||||

| Analysis = Epi Info and SPSS V 17 | ||||

| Sampling = Multistage sampling | ||||

| Khat use measured using Lifetime and current use of Khat | ||||

| 4. | [26] | To reach reasonable estimate of the prevalence of khat chewing in the Jazan region and to investigate the different factors associated with this widespread habit. | Study design = observational cross-sectional | Smoking status, OR = 14.03 (95% CI; 10.76–18.30); Friend using khat, OR = 5.65 (95% CI; 3.92–8.14); Sister using khat, OR = 2.04 (95% CI; 1.11–3.74); Father using khat, OR = 1.45 (95% CI; 1.16–1.82); Brother using khat, OR = 1.56, 95% CI; 1.27–2.00) |

| Population and size = 4,100 school students at the intermediate and secondary school | ||||

| Place = Jazan Region SA | ||||

| Study instrument = A standardized, self-administered questionnaire | ||||

| Analysis = Epi Info and SPSS V 17 | ||||

| Sampling = three-stage cluster random sampling. | ||||

| Khat use measured using Lifetime and current use of Khat | ||||

| 5. | [25] | To establish prevalence of khat use, factors affecting students’ khat use, and also the effect of students’ khat use on their academic performance | Study design = cross-sectional in design | Smoking cigarette, AOR = 5.7 (95% CI: 2.3–14.3); Drinking alcohol, AOR = 3.0 (95% CI: 1.4–6.3); Having a family growing khat, AOR = 2.0 (95% CI: 1.1–2.5); Friend chewing khat, AOR = 3.1, (95% CI: 2.0–4.6); Male, AOR = 2.5, (95% CI: 1.6–3.8); Family Khat history, AOR = 2.0 (95% CI: 1.2–3.0); Ever practiced sex, AOR = 2.0 (95% CI: 1.3–3.0) |

| Population and size = 1,655 students | ||||

| Place = Sidama zone | ||||

| Study instrument = self-administered questionnaire | ||||

| Analysis = SPSS V 20 | ||||

| Sampling = Stratified sampling | ||||

| Khat use measured using Lifetime and current use of Khat | ||||

| 6. | [22] | To determine the prevalence and associated factors of Khat chewing among students of the high school in Jazan city, Saudi Arabia and to study its impact of on students’ academic performance. | Study design = Cross- sectional studies | Age 18 years, OR = 2.44, (95% CI: 1.12–5.33); Fathers use Khat, OR = 3.57, (95%CI: 1.98–6.46); Brothers use Khat, OR = 4.11, (95%CI: 2.28–17.64) |

| Population and size = 370 high school | ||||

| Place = Jazan City | ||||

| Study instrument = self-administered questionnaire | ||||

| Analysis = SPSS V 22 | ||||

| Sampling = simple random sampling | ||||

| Khat use measured using Lifetime and current use of Khat |

Risk factors of khat chewing among adolescents

Most of the studies included measured the lifetime and current use of khat (ever, current, and never) [22–26] (Agili et al., 2018; Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013), with only one study measured history of khat use [27] (Reda et al., 2012). Age, gender, religion, grade, living with who, having family/friend/brother/sister/mother chewers, living with chewer, residential area, living status during school age, smoking cigarette, drinking alcohol, having family growing khat, participating in khat production and marketing activities, amount of monthly pocket money, friend smoking, friend use tobacco, received probation during last year, and feel depressed, parents’ educational level, family income, family attitude were identified risk factors with khat chewing among adolescents in all the articles reviewed.

However, having family members either sister, brothers or father consumed khat [23–27] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013; Reda et al., 2012), friends or peers who are also chewed khat [22–27] (Agili et al., 2018; Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013; Reda et al., 2012), male gender [23–25, 27] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Lpha & Esaiyas, 2017; Reda et al., 2012), and smoker [23, 25, 26] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013) were frequently reported risk factors significantly influenced the act of khat chewing among adolescents, with history of smoking had the highest odd of 18.2 (95% CI: 12.95–25.72) [23] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013). High odds were also observed for male gender, ranging from 2.1 (95% CI: 1.50–2.93) [26] (Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013) to 10.1 (95% CI: 4.88–17.38) [23] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013). The significant association between having family members chewing khat and khat intake among adolescents were reported in all six articles, with one study reported only a small number of parents disagree with the use of khat among their adolescent children [26] (Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013). Meanwhile, five articles reported significant association between having friends or peers chewing khat and khat chewing among adolescents [23–27] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013; Reda et al., 2012), with four articles reported significant association between male gender and khat chewing among adolescents [23–25, 27] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Reda et al., 2012), indicating the important roles of the both risk factors to influence khat chewing among adolescents. The non-significant association between peer influence and gender with khat consumption reported in the other articles reflecting he cultural role of khat chewing which is dominant in certain communities in these regions. On the other hand, being a smoker was reported as a significant risk factor in three articles [23, 25, 26] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013) reviewed. Most of the studies included measured the lifetime and current use of khat (ever, current, and never) [22–26] (Agili et al., 2018; Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Lakew et al., 2014; Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017; Mahfouz, Alsanosy & Gaffar, 2013), with only one study measured history of khat use [27] (Reda et al., 2012).

Discussion

The review was conducted to identify the risk factors that significantly predict khat chewing among adolescents. Our review found, having family members and friends or peers who chewed khat, male gender and smoking frequently predicts khat chewing among adolescents, with the significant role of family members was reported in all six articles reviewed.

Numerous scholars reported khat as a malicious product that distracts the nation’s health, economy, and family dynamic as well as cultural or religious arguments [29] (Gudata, 2020). In certain society, khat consumption is accepted as an integral part of their culture, such as birth rituals, circumcision and marriage events. Additionally, among farmers, labourers and long-distance lorry drivers, chewing khat able to provide them energy for their labour-intensive daily activities, as well as for students when preparing for exams [30] (Laminal, 2010). Similarly, clan elders, and religious devotees were also frequently consumed khat for similar reason for all night sessions of prayer during Ramadan, which have been practiced over a long period of time [29] (Gudata, 2020) as cultural norms. Despite the reported scale of production and consumption, relatively little is known about the many ways in which khat interacts with lives, livelihoods, health, and economies, with attempts to legally prohibit khat use in some countries have been failed [30] (Laminal, 2010).

There has been substantial supporting evidence on the role of family members and peers in substance intake among adolescents, with peer and family use are direct correlates to use of substances by adolescents [31] (Tsering & Pal, 2009). Khat consumption is part of cultural norms in certain communities, which may also involve family interactions, parenting styles and practices, as well as family modelling and family backgrounds that can influence adolescents and youth behaviour [29] (Gudata, 2020). Its social and cultural norms was reflected by more than half of the female students and a quarter of the male students chewed khat with family members and relatives reported in one of the studies reviewed [29] (Gudata, 2020). Family and peer involve on both, the initiation and continuation of adolescent substance use, either due to poor parental behavior monitoring and control or acceptance towards the substance, manifested by their intake. Family particularly the parents serve as a role models and gatekeepers to both opportunities and barriers, for their children in imparting important health-related knowledge and appropriate behavior [32] (Al-Abed et al., 2014). Not only the vulnerability of adolescent age groups, but the social environment where the adolescent lives make him or her susceptible to use or disuse of various substances [31] (Tsering & Pal, 2009). The social acceptability towards khat chewing and socialization norms of this habit increase the likelihood of adolescents adopting the behavior [25] (Kassa, Loha & Esaiyas, 2017).

Khat chewing has been a common practice and traditionally accepted among the males and more culturally restricted in females [33] (Haile & Lakew, 2015), contribute to the lack of exposure among the females [34] (Gebrie et al., 2018). This significant difference may be due to the cultural acceptance of male practicing unusual things including khat chewing and other substances because khat generally considered “men’s thing” and viewed as unfavorable behavior for women [35] (Nakajima et al., 2013). The cultural taboo that excludes women for certain type of social [34] (Bebrie et al., 2018) activities may have contributed towards the role of gender as a risk factor for khat chewing [36] (Kassim, Rogers & Leach, 2014).

Majority of khat users also smoke tobacco but the temporal relationship or origin of this khat- tobacco use association is unknown. There has been argument on the similarity ways of consumption between khat and tobacco smoking [37] (Douglas & Hersi, 2010), and substance intake is frequently observed among men compared to women [38] (Becker, McClellan & Reed, 2017). Available evidence also showed that the habit of khat chewing reinforces the development of other habits such as cigarette smoking [39] (Birhane, 2014), as well as the effect of the khat consumption are enhanced mutually with cigarette smoking [12] (Alemu et al., 2020). The underlying psychobiological mechanisms of this link remain unclear, although it is possible that social cues and pharmacological priming associated with khat use may increase the likelihood and reinforcing effects of smoking [35] (Nakajima et al., 2013). Regional studies show that higher prevalence of cigarette smoking among khat and positive associations between levels of khat dependence and nicotine dependence [35] (Nakajima et al., 2013).

Many adverse effects have been linked with khat chewing which include impairment of mental [37–40] (Douglas & Hersi, 2010; Becker, McClellan & Reed, 2017; Birhane, 2014; Muluneh, 2018) and physical health such as myocardial infarction [10] (Al-Motarreb et al., 2002), ischemic heart disease [11] (Mega & Dabe, 2017), manic-like schizophrenia [12] (Alemu et al., 2020), erectile dysfunction [13] (Hassan, Gunaid & Murray Lyon, 2007), psychotic experiences [15] (Odenwald & Khatkonsum, 2008), oesophageal cancer [16] (Bozzuto, Ruggieri & Molinari, 2010), stroke, gastritis and hepatitis [40] (Muluneh, 2018). The urgent need to create better awareness on the potential negative consequences of khat chewing malpractice have been reported in several studies [23, 40–43] (Alsanosy, Mahfouz & Gaffar, 2013; Muluneh, 2018; Odenwald et al., 2007; Odenwald & Al’ansi, 2017; Wedegaertner et al., 2010).

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review assessing the risk factors of khat chewing among adolescents. The use of five common databases as well involvement of four authors, ensured the strength of the search strategy and minimization of bias during selection of articles and data extraction. The review is also dominated by high quality articles. However, all articles reported the factors as risks towards khat consumption with none exploring the potential mediating and moderating role of potential factors such as gender, smoking or even family influence, which should be considered in future related research. The limitation of this study was only restricted to articles written in English; the studies were cross-sectional design in nature so it cannot show causality.

Conclusions

The current review highlights the important risk of having family members and friends or peers who are also chewing khat, male gender and smoking to significantly predict khat chewing among adolescents. Health promotion program to educate adolescents on the harmful effects of khat chewing should target male adolescents and emphasize on the crucial participation of the family members and friends.

Supporting information

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for this research project.

References

- 1.Al-Mugahed L. Khat chewing in Yemen: turning over a new leaf. Khat chewing is on the rise in Yemen, raising concerns about the health and social consequences. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008; 86(10): 741–742. doi: 10.2471/blt.08.011008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahmoud SS, Khamis KA, Mania KM, Darbashi SA, Doshi YA, Hefdhi AM, et al. (2017). Prevalence and Predictors of Khat Chewing among Students of Jazan University, Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal Of Preventive And Public Health Sciences. 2017; 2(6): 8–10. 10.17354/ijpphs/2016/51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astatkie A, Demissie M, Berhane Y, Worku A. Prevalence of and factors associated with regular khat chewing among university students in Ethiopia. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2015; 41. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S78773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sikiru L. Khat (Catha edulis): the herb with officio-legal, socio-cultural and economic uncertainty. South African Journal of Science.2010; 106(3): 2–5. 10.4102/sajs.v106i3/4.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong EG. Research note: Crime, chemicals, and culture: On the complexity of khat. Journal of Drug Issues.2008; 38(2): 631–648. 10.1177/002204260803800212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathewson H, James K, Schifano F, Sumnall H, Wing AAD. Khat: A review of its potential harms to the individual and. Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs.2013; 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman R, Al’Absi M. Khat Use and Neurobehavioral Functions: Suggestions forFuture Studies. Journal of Ethnopharmacol. 2011; 132(3): 554–563. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.033.Khat [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meressa K, Mossie A, Gelaw Y. (2009). Effect of Substance use on academic achievement of health officer and medical stuents of Jimma university, Southwest Ethopia. In Ethiopian journal of health sciences. 2009; 19 (3): 155–163 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhaifalah I, Santavý J. Khat habit and its health effect. A natural amphetamine. Iomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub.2004; 148(1): 11–15. 10.5507/bp.2004.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Motarreb A, Al-Kebsi M, Al-Adhi B, Broadley KJ. Khat chewing and acute myocardial infarction. Heart.2002; 87(3): 279–280. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mega TA, Dabe NE. Khat (Catha Edulis) as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal. 2017; 11: 146–155. doi: 10.2174/1874192401711010146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alemu WG, Zeleke TA, Takele WW, Mekonnen SS. Prevalence and risk factors for khat use among youth students in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis, 2018. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2020; 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12991-019-0254-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan NAGM, Gunaid AA, Murray Lyon IM(2007). Khat (catha edulis): health aspects of khat chewing. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2007; 13(3): 706–718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lifson AR, Workneh S, Shenie T, Ayana DA, Melaku Z, Bezabih L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with use of khat: a survey of patients entering HIV treatment programs in Ethiopia. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2017; 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13722-016-0069-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odenwald M, Khatkonsum C. (2008). Chronic khat use and psychotic disorders: A review of the literature and. Sucht. 2008; 53(2007): 9–22. 10.1463/2007.01.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozzuto G, Ruggieri P, Molinari A. Molecular aspects of tumor cell migration and invasion. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore Di SanitÃ. 2010; 46: 66–80. doi: 10.4415/ANN_10_01_09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khawaja M, Al-Nsour M, Saad G. Khat (Catha edulis) chewing during pregnancy in Yemen: Findings from a national population survey. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008; 12(3): 308–312. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glenice C, Hagen R. (2003). Adverse effects of khat: a review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003; 9(6): 456–463. 10.1192/apt.9.6.456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 21;6(7): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teferra S, Hanlon C, Jacobsson L. Khat chewing in persons with severe mental illness in Ethiopia: A qualitative study exploring perspectives of patients and caregivers. Transcultural Psychiatry.2011; 48(4), 455–472. doi: 10.1177/1363461511408494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A. Comparison of the effects of using the Crowe critical appraisal tool versus informal appraisal in assessing health research: A randomised trial. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2011; 9(4): 444–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agili AOB, Hakami IWA, Abu TA, Kariri R, Jaber A, Alhagawy E, et al. Determination of The Prevalence of Khat Chewing Among Students of The High School in Jazan City, Saudi Arabia. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2018; 7(3): 45–54. 10.20959/wjpps20183-11061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsanosy RM, Mahfouz MS, Gaffar AM. Khat Chewing Habit among School Students of Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakew A, Tariku B, Deyessa N, Reta Y. Prevalence of Catha edulis (Khat) Chewing and Its Associated Factors among Ataye Secondary School Students in Northern Shoa, Ethiopia. Advances in Applied Sociology. 2014; 4: 225–233. doi: 10.4236/aasoci.2014.410027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassa A, Loha E, Esaiyas A. Prevalence of khat chewing and its effect on academic performance in Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2017; 17(1):175–185. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v17i1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahfouz MS, Alsanosy RM, Gaffar AM. The role of family background on adolescent khat chewing behavior in Jazan Region. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2013; 12(1), 1. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reda AA, Moges A, Biadgilign S, Wondmagegn BY. Prevalence and determinants of khat (Catha edulis) chewing among high school students in eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE.2012; 7(3): 3–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students (BMC medical education (2018) 18 1 (98)). BMC Medical Education. 2018; 18(1): 167. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1273-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gudata ZG. (2020). Khat culture and economic wellbeing: Comparison of a chewer and non-chewer families in Harar city. Cogent Social Sciences. 2020; 6(1). 10.1080/23311886.2020.1848501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khat Laminal S. (Catha edulis): The herb with officio-legal, socio-cultural and economic uncertainty. South African Journal of Science. 2010; 106(3–4): 2–5. 10.4102/sajs.v106i3/4.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsering D, Pal R. Role of Family and Peers in Initiation and Continuation of Substance Use. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2009; 31(1), 30–34. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.53312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Abed AAA, Sutan R, Al-Dubai SAR, Aljunid SM. Family context and khat chewing among adult Yemeni women: A cross-sectional study. BioMed Research International. 2014; 2014: 505474. doi: 10.1155/2014/505474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haile D, Lakew Y. Khat chewing practice and associated factors among adults in Ethiopia: Further analysis using the 2011 demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(6): 1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebrie A, Alebel A, Zegeye A, Tesfaye B. Prevalence and predictors of khat chewing among Ethiopian university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13(4): 1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakajima M, al’Absi M, Dokam A, Alsoofi M, Khalil NS, Al Habori M. Gender differences in patterns and correlates of khat and tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(6):1130–5. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kassim S, Rogers N, Leach K. The likelihood of khat chewing serving as a neglected and reverse “gateway” to tobacco use among UK adult male khat chewers: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14(1): 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douglas H, Hersi A. Khat and islamic legal perspectives: Issues for consideration. Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. 2010; 42(62): 95–114. 10.1080/07329113.2010.10756651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker JB, McClellan ML, Reed BG. Sex differences, gender and addiction. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2017; 95(1–2): 136–147. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birhane BW. The Effect of Khat (Catha edulis) Chewing on Blood Pressure among Male Adult Chewers, Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Science Journal of Public Health. 2014; 2(5): 461. 10.11648/j.sjph.20140205.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muluneh BE. Economic and Social Impacts of Khat (Catha edulis Forsk) Chewing Among Youth in Sebeta Town, Oromia Ethiopia. Biomedical Statistics and Informatics. 2018; 3(2): 29. 10.11648/j.bsi.20180302.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odenwald M, Hinkel H, Schauer E, Neuner F, Schauer M, Elbert TR, et al. The consumption of khat and other drugs in Somali combatants: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine. 2007; 4(12): 1959–1972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odenwald M, Al’absi M. Khat use and related addiction, mental health and physical disorders: the need to address a growing risk املتنامية للمخاطر ي ِّالتصد رضورة:وبدنية ونفسية إدمانية اضطرابات من به يتصل وما القات تعاطي. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2017; 23(3):236–244 http://applications.emro.who.int/emhj/v23/03/EMHJ_2017_23_03_236_244.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 doi: 10.26719/2017.23.3.236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wedegaertner F, Al-Warith H, Hillemacher T, Te Wildt B, Schneider U, Bleich S, et al. Motives for khat use and abstinence in Yemen—A gender perspective. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10(1): 735. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.