Abstract

Characterizing seasonal trend in lung function in individuals with chronic lung disease may lead to timelier treatment of acute respiratory symptoms and more precise distinction between seasonal exposures and variability. Limited research has been conducted to assess localized seasonal fluctuation in lung function decline in individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) in context with routinely collected demographic and clinical data. We conducted a longitudinal cohort study of 253 individuals aged 6–22 years with CF receiving care at a pediatric Midwestern US CF center with median (range) of follow-up time of 4.7 (0–9.95) years, implementing two distinct models to estimate seasonality effects. The outcome, lung function, was measured as percent-predicted of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). Both models showed that older age, being male, using Medicaid insurance and having Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection corresponded to accelerated FEV1 decline. A sine wave model for seasonality had better fit to the data, compared to a linear model with categories for seasonality. Compared to international cohorts, seasonal fluctuations occurred earlier and with greater volatility, even after adjustment for ambient temperature. Average lung function peaked in February and dipped in August, and FEV1 fluctuation was 0.81 % predicted (95% CI: 0.52 to 1.1). Adjusting for temperature shifted the peak and dip to March and September, respectively, and decreased FEV1 fluctuation to 0.45 % predicted (95% CI: 0.08 to 0.82). Understanding localized seasonal variation and its impact on lung function may allow researchers to perform precision public health for lung diseases and disorders at the point-of-care level.

Keywords: lung disease, medical monitoring, nonlinear, seasonality, sine wave, temperature

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Environmental exposures and community characteristics can profoundly influence lung disease progression in cystic fibrosis (CF), a lethal autosomal disease marked by progressive loss of lung function (1). Extant geographical markers of environment like warmer climates have been associated with rapid lung function decline and more severe pulmonary exacerbations in individuals with CF (2). An estimated 70,000–100,000 individuals worldwide live with this chronic lung disease (3). Although CF is caused by dysfunction in a membrane protein and chloride channel known as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, non-genetic influences have been estimated to explain 50% of the variation in lung function among CF patients (4). A significant portion of the North American, Western European and Australian CF populations contributes clinical/demographic data to national patient registries (range of coverage: 88–95%) (5), which has enabled various epidemiologic studies of risk factors for accelerated lung function decline. Risk factors commonly identified include Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections, pancreatic insufficiency and lower socioeconomic status (6) (7) (8).

Environmental/external exposures are also believed to impact lung function, and it has been hypothesized that there may be seasonal influences. Only two studies have examined the relationship between ambient air temperature or seasonality and rate of lung function decline in CF. The first study found that warmer ambient air temperatures were associated with lower lung function in individuals with CF who live in the US and Australia (2). This study found similar associations between air temperature and lung function in the two countries but did not examine the statistical interaction between temperature and rate of decline. In addition, longitudinal lung function measurements were annualized rather than using the observed value at each clinical encounter. Another study of Northern European CF populations, the UK and Denmark, using patient registries found relatively low variation in lung function according to season (9). This study applied a sine wave model to estimate the phase and amplitude of seasonal variation in lung function; however, seasonality effects were not adjusted for temperature. The authors utilized different analytic methods to fit longitudinal lung function data, compared to the US/Australian replication study, making it difficult to compare seasonal fluctuations among the international populations. Although both studies had broad coverage through use of registries, neither study examined seasonal variation on a local or regional level. This could be because UK and Denmark are both small countries with similar geographic conditions. By contrast, the US and Australia are both large countries but do not share geographic conditions.

The replicability of findings on seasonal variation in CF lung function at the local level is unknown, and the extent to which temperature impacts this relationship is largely unexplored. Understanding seasonal differences could offer additional explanation for lung function variability, be used to inform local care and facilitate precision public health efforts for lung diseases at the point-of-care level. This study sought to examine the impact of seasonal variation and adjustment for temperature on CF lung function by implementing novel and previously published models, enabling comparison of seasonal fluctuations between local and international cohorts and an assessment of impacts at the local/regional level in pediatric populations with CF.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and cohort

We performed a retrospective longitudinal cohort study of individuals with a diagnosis for CF who received care at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Cystic Fibrosis Center located in Cincinnati, OH, USA, between 2012 and 2017. Demographic and clinical data from each encounter were acquired on individuals aged 6 years and older, in order to obtain lung function measurements from pulmonary function tests. The maximum age at this pediatric center was 22 years. The outcome of interest was lung function, measured as percent-predicted of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); this measure is adjusted using standard reference equations (10) (11). The demographic and clinical covariates included 1) time-invariant variables: sex, Medicaid insurance use, genotype (F508del homozygous, heterozygous or neither/unknown), and pancreatic insufficiency (defined as taking pancreatic enzymes), and 2) time-varying variables, including age at encounter (years), and culturing positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. These covariates were selected based on prior literature review of longitudinal CF FEV1 studies (6) and inputs used in the aforementioned international studies (2) (9).

2.2. Seasonality and temperature assessments

We employed two models that account for seasonality in different ways. One uses a categorical variable for season, which allows estimating rate of change in lung function by seasons over time. The other uses a sine wave, which allows estimating amplitude and shift of the seasonal variation and was used in the previous UK/Danish study (9). A four-level categorical variable was created according to when a given clinical encounter occurred. December, January and February were coded as winter; March, April and May corresponded to spring; June, July and August corresponded to summer; September, October and November corresponded to autumn. Another variable was created to label the encounter day according day of a given year, with January 1st being day zero and December 31st being day 364/365. Daily mean air temperature (Kelvin) was obtained from the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR), taken as the value from the 32 × 32 sq km grid that most overlapped the geographic study region (12). Additional details are provided in a methodologic article (Section 1) (13). Temperature adjustment was made to the final model by including daily temperature as a covariate.

2.3. Models with categorized seasonality

We implemented a linear mixed effects model to assess the potential impact of association between seasonality and FEV1. The model was adapted from a prior study (14) by adding the categorical variable for seasonality as a main effect and including its interaction with the time variable (visit age). The general form of the model has been provided as Equation (1) of the aforementioned reference (13). The main and interaction effects for the categorical variable season were included in the model through a series of indicator variables to represent the different categories, where the reference category was winter. The interaction between season and encounter time term allows for distinct FEV1 trajectories over age according to season. A subject-specific random intercept term was included, allowing fluctuation from an individual FEV1 trajectory relative to the population-level trajectory; also included was a stochastic process function accounting for within-subject correlation assuming an exponential covariance function; that is, the covariance matrix for repeated measures within an individual follows an exponentially decaying correlation with increasing time difference. A single term for measurement error and residual variation were included.

This model is commonly utilized for CF longitudinal FEV1 analysis (15), but it assumes a linear evolution for lung function (corresponding to the same rate of change across all ages) and does not account for natural ordering of seasons. The impact of seasonality in the model was assessed using a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to compare the model formulated in Equation (1) with a model that excluded the main and interaction effects of seasonality. Details of each model output are provided in Table 2.

Table 2:

Parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for models (1) and (2) of lung function and seasonality for the Cincinnati Cystic Fibrosis Cohort*

| Season as a categorical variable (Model 1) | Sine wave for seasonality (Model 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Main effects | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) |

| Intercept | 96.45 (86.16, 106.73) | 96.01 (85.78, 106.23) |

| Time | 1.15 (0.21, 2.09) | 1.17 (0.22, 2.09) |

| Male sex | −8.57 (−12.61, −4.52) | −8.53 (−12.57, −4.48) |

| Birth cohort | ||

| Cohort 1989–1994 | 37.74 (27.15, 48.24) | 38.19 (27.59, 48.78) |

| Cohort 1995–1998 | 10.4 (1.44, 19.36) | 10.58 (1.62, 19.54) |

| Cohort 1999–2005 | 8.25 (1.15, 15.35) | 8.35 (1.25, 15.45) |

| Cohort 2006 (ref) | ||

| CFRD | 0.81 (−4.63, 6.25) | 0.74 (−4.70, 6.18) |

| Not using Medicaid insurance | 5.53 (1.47, 9.59) | 5.50 (1.44, 9.56) |

| Pa | 3.41 (0.91, 5.91) | 3.45 (0.95, 5.95 |

| MRSA | −2.44 (−4.94, 0.06) | −2.54 (−5.04, −0.04) |

| F508del | ||

| Heterozygous | 1.58 (−2.85, 6) | 1.37 (−3.06. 5.79) |

| None | −2.29 (−12.2, 7.62) | −2.49 (−12.40, 7.42) |

| Homozygous (ref) | ||

| On pancreatic enzymes | 5.01 (−2.7, 12.73) | 5.08 (−2.63, 12.79) |

| Season | ||

| Autumn | 0.4 (−1.61, 2.41) | |

| Spring | −2.25 (−4.32, −0.19) | |

| Summer | 0.6 (−1.46, 2.65) | |

| Winter (ref) | ||

| Sine | 0.48 (0.19, 0.77) | |

| Cosine | 0.66 (0.36, 0.95) | |

| Interaction with time | ||

| Male sex | 0.51 (0.24, 0.78) | 0.50 (0.23, 0.77) |

| Birth cohort | ||

| Cohort 1989–1993 | −3.23 (−4.09, −2.37) | −3.28 (−4.13, −2.42) |

| Cohort 1994–1998 | −1.78 (−2.56, −1) | −1.83 (−2.61, −1.04) |

| Cohort 1999–2005 | −1.45 (−2.21, −0.7) | −1.49 (−2.25, −0.73) |

| Cohort 2006 (ref) | ||

| CFRD | −0.76 (−1.06, −0.46) | −0.77 (−1.07, −0.47) |

| Not using Medicaid insurance | 0.24 (−0.03, 0.50) | 0.23 (−0.03, 0.50) |

| Pa | −0.34 (−0.51, −0.17) | −0.34 (−0.51, −0.17) |

| MRSA | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.24) | 0.07 (−0.11, 0.25) |

| F508del | ||

| Heterozygous | −0.08 (−0.37, 0.22) | −0.07 (−0.36, 0.23) |

| None | −1.04 (−1.78, −0.29) | −1.05 (−1.80, −0.31) |

| Homozygous (ref) | ||

| On pancreatic enzymes | −1.21 (−1.81, −0.62) | −1.21 (−1.80, −0.61) |

| Season | ||

| Autumn | −0.107 (−0.25, 0.036) | |

| Spring | 0.124 (−0.02, 0.271) | |

| Summer | −0.11 (−0.255, 0.035) | |

| Winter (ref) |

Models (1)-(2) refer to the two main statistical models applied to the cohort (see Methods section). Reference category included as “ref” for main and interaction effects.

Abbreviations: CFRD = cystic fibrosis related diabetes; MRSA = Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; Pa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa

2.4. Sine wave models for seasonality

In the second approach, to model seasonal effect, we fit a harmonic seasonal model, which uses a sine or cosine function to describe the pattern of fluctuations seen across periods. Specifically, we modeled smooth changes in lung function according to season using a sine wave where the period is one year (365.25 days) and the amplitude and horizontal shift are model parameters to be estimated from the data. We adapted this model from the previously described European CF seasonality study (9). We compared published estimates of coefficients of the sine wave models in this study to our findings by reconstructing the estimated confidence regions for Denmark and the UK. The description, adaptation and calculations to perform comparisons to other cohorts are developed in the methods article (13). Similar to model (1), the impact of seasonality in model (2) was assessed using a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to compare the model formulated in Equation (2) with a model that excluded the sine wave. Additionally, fits of model (1) and model (2) were compared by using AIC, BIC, -2LL, RMSE and MAE which are provided in Table S1 in the Appendix. Model parameter estimates are reported with 95% confidence interval (CI) in Table 2. P-values below 0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant.

We used the ’nlme’ package (version 3.1–140) in R software (version 3.6.1) to fit each of the models. The model coefficients are estimated using maximum likelihood. The R code to produce the results presented in this article is provided with detailed steps in the methods article (13).

2.5. Sensitivity analyses

Given that prior analyses of the US and Australian CF cohorts indicated that Pseudomonas aeruginosa and MRSA pathogens mediated the association between temperature and FEV1 (16), we examined available data on these two pathogens for the selected primary model. The encounter-level measures for MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were each coded as binary for presence or absence. Mediation modeling and implementation steps are described in Section 4 of the methods article (13). Analyses were performed using the mediation package (version 4.5.0) in R (17), which provides estimated average casual mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), total effect (direct effect + indirect effect), and the proportion of mediated effects by using a three-step procedure (18). The ACME, which is the indirect effect of the mediator, was used to evaluate statistical significance of the mediating impact of each infection type on the relationship between seasonality and FEV1.

Another sensitivity analysis of the primary model focused on association between occurrence of a “red zone” event and FEV1 decline, while accounting for temperature and seasonality. Red zone refers to the clinical status of having an acute drop in lung function, occurring when an individual’s observed FEV1 at an encounter is below 10% predicted of their maximum FEV1 within the prior year of encounters. This rule has been used in published quality improvement studies to uniformly treat pulmonary exacerbation and/or rapid lung-function decline through a standardized care algorithm (19). We estimated the impact of these acute pulmonary function drops by including the number of red zone occurrences within the year prior as a rolling covariate.

3. Results

3.1. Seasonality and cohort characteristics

The analysis cohort data was comprised of 6593 FEV1 observations on 253 patients with data from 2008 to 2017. Additional exploratory plots of the seasonal fluctuation in FEV1, for representative patients and summarized over the cohort, are in the Appendix (Figures S1–S2). Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical summaries for the study cohort stratified by birth cohort as presented in the prior European study (9). The median (range) number of FEV1 observations per individual patient was 24 (1–106), with a median (range) of follow-up time of 4.7 (0–9.95) years. The youngest cohort had no reported CFRD diagnoses.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the Cincinnati Cystic Fibrosis Cohort

| Patient Characteristics | Birth cohort | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989–1994 | 1995–1998 | 1999–2005 | 2006–2011 | ||

| N | 57 | 38 | 93 | 65 | 253 |

| Male, % | 36 (63.2) | 20 (52.6) | 39 (41.9) | 30 (46.2) | 125 (49.41) |

| Genotype (F508del), % | |||||

| Heterozygous | 24 (42.1) | 18 (47.4) | 34 (36.6) | 19 (29.2) | 95 (37.55) |

| Homozygous | 30 (52.6) | 19 (50.0) | 53 (57.0) | 42 (64.6) | 144 (56.92) |

| No copies | 3 (5.3) | 1 (2.6) | 6(6.5) | 4 (6.2) | 14 (5.53) |

| On pancreatic enzymes, % | 53 (93.0) | 34 (89.5) | 83 (89.2) | 56 (86.2) | 226 (89.33) |

| Medicaid insurance use, % | 19 (33.3) | 15(39.5) | 48 (51.6) | 29 (44.6) | 111 (43.87) |

| Pa, % | 45 (78.9) | 27 (71.1) | 69 (74.2) | 25 (38.5) | 166 (65.61) |

| MRSA, % | 28 (49.1) | 18 (47.4) | 52 (55.9) | 26 (40) | 124 (49.01) |

| CFRD, % | 20 (35.1) | 13 (34.2) | 19 (20.4) | 0 (0) | 52 (20.55) |

| Average (range) follow up time (years) | 4.13 (0–8.2) | 7.17 (0–9.72) | 6.48 (0–9.95) | 2.26 (0–5.55) | 4.97 (0 – 9.95) |

Abbreviations: CFRD = cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; MRSA = Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus; Pa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa

3.2. Models with categorized seasonality

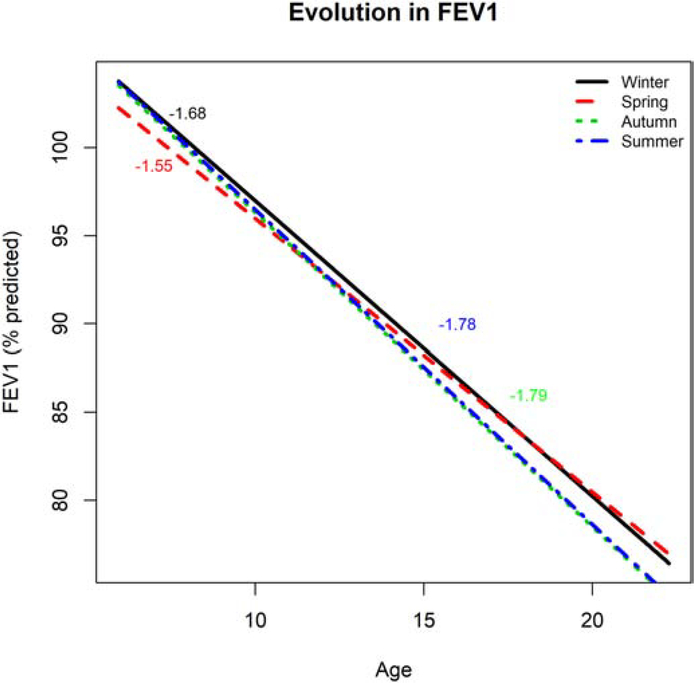

Parameter estimates from model (1) are provided in Table 2. Comparing model (1) with a model of the same form but excluding the season terms gave a LRT p-value of 0.0001, indicating strong evidence of an association between season and FEV1 (Table S1). Based on our analyses, lung function was estimated to be significantly lower during the spring (−2.25 % predicted, 95% CI: −4.32 to −0.19) compared to winter. Figure 1 shows the population-level mean evolution - with rate of change in lung function by seasons over time for US data. As we have assumed a linear evolution, the left figure shows straight lines, corresponding to a linear estimated fit. The rate of change is calculated by taking the first derivative of the model equation with respect to time. This model estimates the rate of change in FEV1 as constant over different ages was estimated to be −1.68 (95% CI: −2.05, −1.39) for winter, −1.78 (95% CI: −2.17, −1.51) for autumn, −1.55 (95% CI: −1.86, −1.13) for spring and −1.79 (95% CI: −2.15, −1.49) for summer, and these were assumed to be the same at all ages. By performing pairwise comparison for seasons, we examined whether the estimated rates of change differ between seasons. The estimated rate of change was statistically not different between autumn and summer (p-value=0.964) but differed between spring and summer (p-value=0.0012) and spring and autumn (p-value=0.0019). Furthermore, rate of change did not significantly differ for winter compared to other seasons (p-values=0.143, 0.097, and 0.139 for autumn, spring, and summer, respectively). Rates of change in autumn and summer were relatively higher than in spring and winter.

Figure 1:

Estimated population evolution in % predicted FEV1 (y-axis) over age (x-axis) by season (black, red, green and blues lines are for winter, spring, autumn, and summer, respectively) for the Cincinnati cohort for categorized seasonality (Model 1). The corresponding estimated rate of change in % predicted FEV1 are reported in text with color corresponding to a given season.

3.3. Sine wave models for seasonality

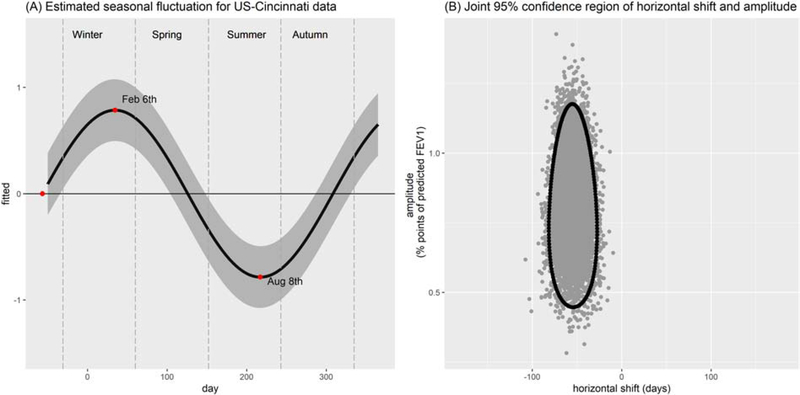

Parameter estimates from model (2) are shown in Table 2. Based on our analyses the overall effect of seasonality on lung function of individuals with CF improved model fit (LRT p-value=0.0001). According to the sine wave model, amplitude in seasonal variation was 0.81 % predicted (95% CI: 0.52, 1.10) while the estimated horizontal shift was −54.7 days (95% CI: −75.5, −33.8) (Table 3). These two quantities can be used to estimate the peak and dip of the sine wave fitted for seasonal fluctuations of lung function. As a result, average lung function was estimated to peak on the 6th of February and dip on the 8th of August (Figure 2–A). Based on the 95% CI for amplitude, we can also state that lung function peaked between January and March. Furthermore, the 95% CI for these dates only covers 41.7 days (see Figure 2–B). This model has yielded better fit and slightly improved prediction accuracies compared to the model (1) based on our analysis (Table S1). Table 2 provides covariate effect estimates for models (1)-(2). Table S2 includes the estimated variance-covariance parameters for both models.

Table 3:

Estimates (95% CIs) for Seasonality Patterns of International and Cincinnati Cohorts under Sine Wave Model

| Denmark | UK | Cincinnati | Cincinnati with temp adjustment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal shift (days) | 148.5 (−182.3, 182.6) | 66.2 (−182.3, 179.5) | −54.7 (−33.8, −75.5) | −15.2 (−106.2, 75.8) |

| Amplitude (% predicted) | 0.1 (0, 0.21) | 0.14 (0, 0.29) | 0.81 (0.52, 1.1) | 0.45 (0.08, 0.82) |

Figure 2:

(A) Estimated seasonal fluctuation in % predicted FEV1 (y-axis) over calendar day (x-axis) for the sine wave fit to Cincinnati data (Model 2). Zero on the x-axis represents January 1st. Shaded region is the 95% confidence region. (B) The joint 95% confidence region spans the horizontal shift (y-axis) and amplitude (x-axis) estimated from the data.

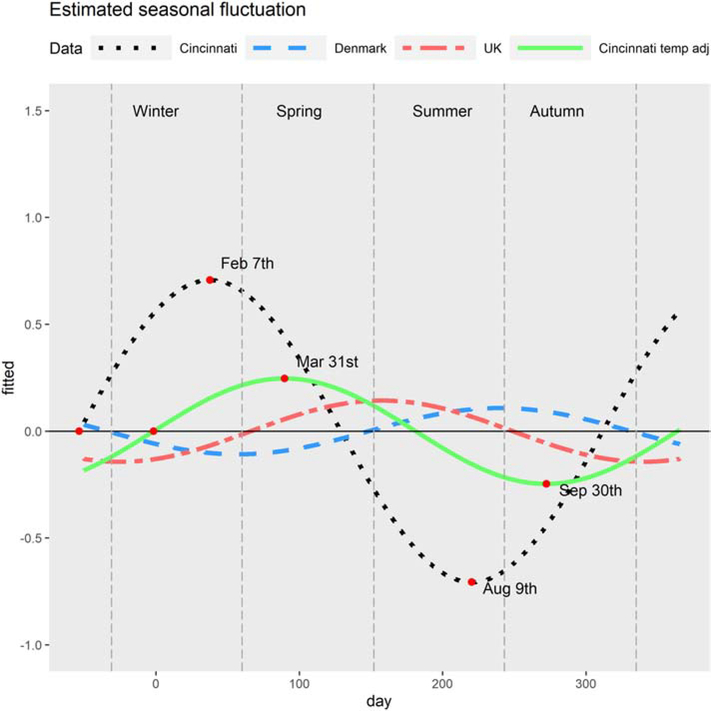

As a result of these findings on model fit, we employed the sine wave model to evaluate seasonal variation after temperature adjustment. We compared our findings for the US-Cincinnati data to the published results of the analyses for the UK and Denmark (9), which also employed a sine wave model.

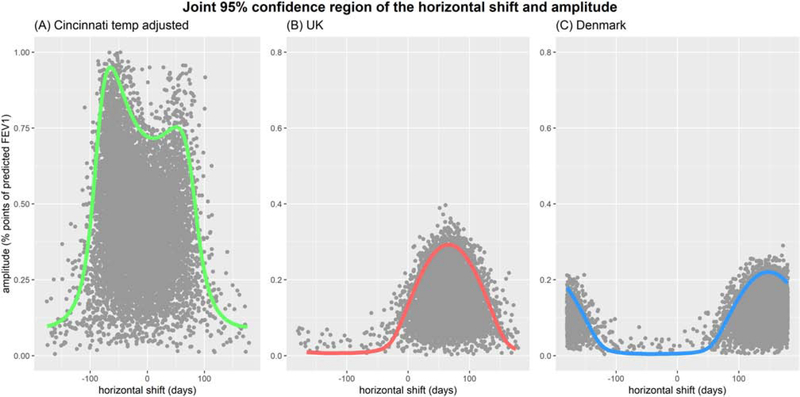

3.4. Temperature adjustment

The impact of temperature adjustment is assessed by including daily temperature (in Celsius) as covariate in model (2). All model parameter estimates and 95% CI are provided in Tables S3–S4 in the Appendix. After adjusting the model for temperature, average lung function was estimated to peak on the 12th March and dip on 11th September (Figure 3). Figure 4–A presents the joint confidence region of horizontal shift and amplitude. The amount of estimated seasonal variation for the US-Cincinnati decreased in magnitude, was no longer statistically significant, and peak timing occurred later, compared to the unadjusted estimates. Temperature adjustment did not substantially alter the coefficient estimates of clinical/demographic covariates in the model. Inclusion of an interaction effect for daily temperature and age worsened the model fit and was therefore excluded from the final model.

Figure 3:

The estimated seasonal variation in FEV1 (y-axis) over day of the year, beginning with January 1st (x-axis) for the sine wave (Model 2) fit to each cohort. Estimated fluctuations shown for the Cincinnati cohort (black dashed line) with temperature adjustment (solid green line) and published models (Denmark, in red; UK, in blue).

Figure 4:

Joint 95% confidence region of the amplitude (y-axis, % predicted) and horizontal shift in days from January 1st (x-axis) from the (A) Cincinnati sine wave model (adjusted for temperature); sine wave models from (B) the UK and (C) Denmark.

3.5. Comparison to international models

We compared the seasonal fluctuation in FEV1 for the US-Cincinnati sine wave model to results from the Denmark and UK cohorts (Table 3). Peak timing occurred earlier and with higher amplitude than either of the international cohorts. Figure 3 shows the sine waves for estimated seasonal variations of the US-Cincinnati, Denmark and UK cohorts. Estimated peak and dip dates for the US-Cincinnati cohort were February 6th and August 8th, respectively. These dates differed from the peak and dip dates for the UK (peak: Jun 7th; dip: Dec 6th) and Denmark (peak: Aug 28th; dip: Feb 27th). The figure 2–B presents the joint confidence region for horizontal shift and amplititude for USA-Cincinnati data (without temperature adjustment) which indicates that lung function is peaking between January and March. Similarly, Figure 4–A shows the joint confidence region for horizontal shift and amplititude for USA-Cincinnati data (with temperature adjustment) that implies that lung function would peak between September and March since the amplitude of the variation is high for horizontal shift between -106 and 76 days. Figure 4–B provides the joint confidence region for horizontal shift and amplititude for the UK where the upper 95% confidence limit for the amplitude was >0.05 only for horizontal shift from -26 and 157 days, implying that lung function peaks between March and September (as reported in (10) (11). In a similar vein, we can state that lung function peaks between June and October for Denmark based on figure 4–C.

Some of the estimated associations between clinical/demographic covariates and FEV1 differed between the US-Cincinnati and international cohorts. Being male was associated with more rapid decline in our model (−8.53% pred/yr; 95% CI is −12.57, −4.48) but was associated with less rapid decline in both the UK and Denmark models. Similarly, having the F508 heterozygous genotype was associated with less rapid decline in our model (1.37% pred/yr; 95% CI is −3.06, 5.79); meanwhile, it was associated with more rapid decline in the international models.

3.6. Sensitivity analyses of respiratory pathogens and acute FEV1 drops

Mediating effects of Pseudomonas were relatively small. Estimates (95% CI) for ACME, ADE, total effect, and the proportion of mediated effects were 0.00017 (−0.0153, 0.02; 0.964), −0.0416 (−0.089, 0; 0.076), −0.0414 (−0.0925, 0.01; 0.11), and 0.015 (−1.4, 0.91; 0.912), respectively (Figure S3). Similarly, the mediation analyses for MRSA estimated ACME, ADE, total effects, and proportion of mediated effects as −0.00027 (−0.01, 0.01; 0.964), −0.0398 (−0.0876, 0.01; 0.094), −0.04 (−0.088, 0.01; 0.104), and 0.0068 (−0.55, 0.73; 0.934), respectively (Figure S4).

There was no substantial change in findings for the primary model upon adjusting for the frequency of red zone events. The magnitude of the seasonal effect slightly decreased, compared to the primary model, and the seasonal variation estimates were similar. After adjusting the model for number of red zone events, average lung function was estimated to peak on the 2nd of March and dip on the 1st of September; therefore, peak timing occurred slightly earlier, compared to the model estimates adjusted only for temperature.

4. Discussion

In this study, we characterized the local seasonal variation of lung function in CF in a Midwest US cohort and estimated the impact of temperature on this variation. Knowing the extent to which lung function changes according to season at the center level may help clinicians to tailor clinical management in CF and other lung diseases. Higher FEV1 variability implies more rapid CF lung-function decline (20); thus, periods of time in which patients exhibit higher variability could offer an opportunity for proactive care, e.g., increasing frequency of clinic visits during late winter and summer (Figure 2). Morgan and colleagues found that straightforward markers of variability, such as median deviation from baseline FEV1, were predictive of lung-function decline. A center could evaluate these measures seasonally for timelier detection of changes in lung function.

Our novel application examined two different types of statistical models with 1) categorized seasonality and 2) sine wave whilst adjusting for clinical and demographic variables routinely collected in clinical settings. We observed that the sine wave model for seasonality had better fit to the data and showed slightly better prediction accuracy compared to the model with categories for seasonality. The sine wave model only has slightly better fit (Table S1), however, it allows for natural ordering of seasons and seems to be a better choice between these two types of models. It is worth noting that differences in fit between the two types of models were slight, although their conclusions appear divergent. Under Model (1), rate of decline in FEV1 was lowest during summer and fall, and overall FEV1 was lowest during spring (Figure 1). The sine wave approach in Model (2) estimated FEV1 as lowest in summer (Figure 2), partially corroborating the notion from Model (1) estimated rate of decline that average lung function achieves its minimum during summer. The linear restriction inherent in Model (1) is not responsible for the discrepancies, as sensitivity analyses suggested similar results when including spline coefficients unique to each season (results not shown). Clinical context suggests further that Model (2) is preferable to Model (1). A prior secondary analysis of pediatric patients from 20 CF centers found that adherence varied over time within the same group of patients as much as 50% (21). Although that particular analysis did not assess seasonality, another CF pediatric study on quality improvement at two centers suggested through descriptive analysis that median body mass index percentile at the center level may fluctuate seasonally (22). While our study focuses on lung function rather than nutrition, preliminary analyses suggest that median FEV1 exhibits minimal seasonal variation, but it is apparent in patient-specific trajectories (Figures S1–S2 in Appendix).

Based on our findings from the analysis of our cohort, regardless of which model is selected, we conclude that there is significant seasonal variation in lung function. Our analyses with the sine wave model, chosen based upon both clinical and statistical rationale, showed that lung function tended to be higher in winter (peak on the 6th February) and lower in summer (dipping on the 8th August). Fluctuations were identified with seasonality even after adjusting for temperature, but those fluctuations were no longer statistically significant after this adjustment. We performed residual regression (23), an alternative approach to adjusting for temperature, but the resulting estimates agreed with the unadjusted estimates (findings not shown). Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis results indicate that acute FEV1 drops do not influence seasonal fluctuations in FEV1, and that respiratory pathogens such as Pseudomonas and MRSA do not mediate these fluctuations although it has been demonstrated previously in larger national cohorts (16). Subgroup analyses were not performed in the prior study, which may have indicated that specific regions were driving mediation effects, such as areas with consistently warmer climates like the Southeastern US, compared to the regional climate of the Midwest US cohort presented in this study. Thus, it is possible that individuals with CF who live in other geographic areas experience warm temperatures but over a shorter time interval; thereby being less affected.

While each model suggests FEV1 varies a small amount seasonally, gains or maintenance in lung function are essential for survival in CF. For example, a clinical intervention could be constructed to observe lung function more frequently or institute other care algorithm components over summer months. While a past randomized controlled trial indicated that there was no meaningful difference when augmenting care with home monitoring (24), multiple quality improvement studies suggest increasing the number of in-person clinic visits as part of other ramp-up strategies is effective at maintaining lung function and decreasing the number of hospitalizations (19, 25–28). A retrospective longitudinal study of the US CF registry also found more frequent in-person clinic visits was associated with less rapid decline in lung function (29). Any increases or steadying of lung function are important, because acute or sustained drops in FEV1 can lead to a “reset” of an individual’s FEV1 trajectory, highlighted in the CF literature as a failure to recover baseline levels of lung function (30). Seasonality or temperature is not itself a modifiable risk factor, as both are exogeneous variables, but care algorithms instituted at certain periods of the year corresponding to dips in lung function, specifically those are driven by periods of warmer weather, could decrease or lessen severity of bouts of lung function decline.

In contrast to our findings, the study for the UK and Denmark populations found seasonal variation in lung function was lacking; however, their models did not adjust for temperature. Our results partly agree with previous findings from the US CF Twin-Siblings study (4), which reported that these patients had higher average lung function in January compared to July. The differences in findings between the US-Cincinnati and the UK and Denmark studies may be due to different climate conditions and other environmental factors.

Another reason for the differences between comparative cohorts may be attributable to the age ranges of the study. Our cohort was pediatric (age range 6–22 years), while UK and Danish cohorts included both children and adults. Qvist and colleagues (9), however, assessed differences in seasonal variation between pediatric and adult age ranges, and found both age ranges had similar seasonal fluctuation. Moreover, our model and the models used for the UK and Denmark are slightly different in terms of the set of covariates included. For example, the model for UK additionally had ethnicity as a covariate. We did not include this covariate due to a limited prevalence of non-White ethnicity in our local cohort. In addition, the interaction term of CFRD is formulated differently. The UK and Denmark analyses included time of onset of CFRD for each individual, while we modeled this as a static term according to CFRD diagnosis.

The model with categorized seasonality allowed us to estimate the rate of change in FEV1 by season and the estimated rate of change was the same for Autumn and Summer but was relatively lower for spring and winter (Figure 1). Our cohort study indicated that the model with the sine wave was preferable (Table S1), but we observed that older age, being male, using Medicaid insurance, and having Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection were significantly associated with accelerated FEV1 decline in both models (Table 2).

The estimated seasonal variation in lung function of individuals with CF decreased and shifted once the model was adjusted for temperature (Figure 3). Interestingly, the joint confidence region for horizontal shift (days) and amplitude (% points of predicted FEV1) became wider, similar to the UK and Danish cohorts. Iťs plausible that temperature adjustment accounts for aspects remaining beyond seasonal fluctuation. For example, the periodic increase in pollen count in this region of the US could be responsible for allergen-induced changes in lung function coinciding with season. Allergic episodes in asthma, marked through emergency department visits, occur more frequently during periods of high pollen counts in oak, birch and grass across the US (31). This may differentially affect people with CF who also have asthma, estimated to be roughly 19% of the CF population in the US and Canada (32). Environmental exposures like outdoor air pollution could contribute in a consistent fashion to CF lung function decline per annum that is exacerbated by warmer temperatures, as it has been shown to do in the general US population. The Framingham Heart Study, following the general population in the Northeastern US, demonstrated that living within a close proximity to a major roadway (within 100 m) and exposure to increased amounts of atmospheric particulate matter less than 2.5 m in diameter were risk factors for lower average FEV1 and more rapid FEV1 decline (33). Another study of adults in Taiwan corroborated these findings and showed this exposure correlated with heightened risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (34). Additional environmental health studies are necessary to characterize how each of these exposures contribute to CF separate from other lung disorders. Mechanistic differences among the disease processes may influence the acuity of lung function decline attributable to environmental exposures.

This study has several limitations. Our marker of socioeconomic status was limited to Medicaid insurance use, which we included in models as a covariate. Although use of Medicaid has historically served as a proxy for low socioeconomic status in US studies (35), it is not always synonymous with low income due to Medicaid expansion and choice to enroll to gain more comprehensive coverage. Medication use was not accounted for in these models or others implemented in the aforementioned US, Australian, Danish and UK models of seasonal influences on FEV1 (2, 9, 16). Models have not been adjusted for influenza season, which could alter local cohort results. Modeling was confined to a single center and, although distinctions were observed in seasonal influences on lung function compared to international cohorts, replication studies with other US centers are needed to determine impact of national policy differences when performing international comparisons. A prior cross-sectional study of the UK and US CF registries found that average FEV1 is higher in individuals living with CF in the US, compared to their UK counterparts (difference: 3.03 % predicted; 95% CI: 2.37 to 3.69) (36). Missing data arose in our study through longitudinal FEV1 measurements. Both models applied specifically assumed that FEV1 data were “missing at random” (37), which was found to be a reasonable assumption in CF pediatric cohorts wherein attrition due to death is low (e.g., 4.1%) (38).

Shedding light on these localized fluctuations in FEV1 contributes to the existing literature on CF seasonality, which has heretofore broadly examined the role of seasonality using national registries. For pediatric patients, changes in lifestyle patterns that occur in seasons are specific to activities such as school schedules or holidays. These changes can alter behavioral patterns, which in turn potentially affects adherence to treatments (25) (39). While seasonality may impact downstream outcomes, understanding its influence may lead to opportunities to perform precision public health for lung diseases and disorders at the point-of-care level.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

There exists seasonal variation in lung function, even after adjusting for local temperatures in a Midwest US cohort of children with cystic fibrosis.

Compared to international cohorts, their seasonal fluctuations occurred earlier and with greater volatility, even after adjustment for ambient temperature.

Later in summer and winter are key periods of time to calculate lung function variability and enact proactive measures of care at the center level.

Acknowledgments

DECLARATION OF COMEPTING INTERESTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01 HL141286 and K25 HL125954]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- ACME

average casual mediation effect

- ADE

average direct effect

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- CI

confidence interval

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second of % predicted

- LL

log-likelihood

- RMSE

root mean square error

- LRT

likelihood ratio test

- MAE

mean absolute error

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- UK

United Kingdom

- US

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Szczesniak R, Rice JL, Brokamp C, Ryan P, Pestian T, Ni Y, Andrinopoulou ER, Keogh RH, Gecili E, Huang R, Clancy JP, Collaco JM. Influences of environmental exposures on individuals living with cystic fibrosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020:1–12. Epub 2020/04/09. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1753507. PubMed PMID: 32264725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaco JM, McGready J, Green DM, Naughton KM, Watson CP, Shields T, Bell SC, Wainwright CE, Group AS, Cutting GR. Effect of temperature on cystic fibrosis lung disease and infections: a replicated cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027784. PubMed PMID: 22125624; PMCID: PMC3220679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly J. Environmental scan of cystic fibrosis research worldwide. J Cyst Fibros 2017;16(3):367–70. Epub 2016/12/06. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.11.002. PubMed PMID: 27916551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collaco JM, Blackman SM, McGready J, Naughton KM, Cutting GR. Quantification of the relative contribution of environmental and genetic factors to variation in cystic fibrosis lung function. J Pediatr. 2010;157(5):802–7 e1–3, doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.018. PubMed PMID: 20580019; PMCID: PMC2948620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson AB, Goss CH Epidemiology of CF: How registries can be used to advance our understanding of the CF population. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2018;17(3):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harun SN, Wainwright C, Klein K, Hennig S. A systematic review of studies examining the rate of lung function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2016.03.002. PubMed PMID: 27259460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasenbrook EC, Merlo CA, Diener-West M, Lechtzin N, Boyle MP. Persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and rate of FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008; 178(8):814–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-3270C. PubMed PMID: 18669817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schechter MS, Shelton BJ, Margolis PA, Fitzsimmons SC. The association of socioeconomic status with outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(6):1331–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.9912100. PubMed PMID: 11371397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qvist T, Schluter DK, Rajabzadeh V, Diggle PJ, Pressler T, Carr SB, Taylor-Robinson D. Seasonal fluctuation of lung function in cystic fibrosis: A national register-based study in two northern European populations. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(3):390–5. Epub 2018/10/23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.10.006. PubMed PMID: 30343891; PMCID: PMC6559396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Dockery DW, Wypij D, Gold DR, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Ferris BG, Jr. Pulmonary function growth velocity in children 6 to 18 years of age. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(6 Pt 1):1502–8. Epub 1993/12/01. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1502. PubMed PMID: 8256891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. PubMed PMID: 9872837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesinger F DG, Kalnay E, Mitchell K, Shafran PC, Ebisuzaki W, Jovic D, Woollen J, Rogers E, Berbery EH, Ek MB. North American regional reanalysis. American Meteorological Society. 2006;87(3):343–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gecili E, Palipana A, Brokamp C, Huang R, Andrinopoulou ER, Pestian T, Rasnick E,, Keogh RH, Ni Y, Clancy JP, Ryan P, & Szczesniak RD Seasonality, mediation and comparison (SMAC) methods to identify influences on lung function decline. MethodsX. 2020;XX(XX):XX-XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szczesniak RD, McPhail GL, Duan LL, Macaluso M, Amin RS, Clancy JP. A semiparametric approach to estimate rapid lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(12):771–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.009. PubMed PMID: 24103586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heltshe SL, Szczesniak RD. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second variability in cystic fibrosis-has the clinical utility been lost in statistical translation? J Pediatr. 2016;172:228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.035. PubMed PMID: 26852182; PMCID: PMC4846543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaco JM, Raraigh KS, Appel LJ, Cutting GR. Respiratory pathogens mediate the association between lung function and temperature in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15(6):794–801. Epub 2016/06/15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.05.012. PubMed PMID: 27296562; PMCID: PMC5138086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, & Imai K Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 2014;59(5). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D, & Yamamoto T Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review. 2011;105:765–89. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPhail GLB PL; Chini BA; Weiland J; Hoberman-Martinez A; Fenchel M; VanDyke R; Clancy JP Improving Rapid FEV1 Decline through Quality Improvement. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012;47(S35):389. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan WJ, VanDevanter DR, Pasta DJ, Foreman AJ, Wagener JS, Konstan MW, Scientific Advisory G, Investigators, Coordinators of Epidemiologic Study of Cystic F. Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second Variability Helps Identify Patients with Cystic Fibrosis at Risk of Greater Loss of Lung Function. J Pediatr. 2016;169:116–21 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.042. PubMed PMID: 26388208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modi AC, Cassedy AE, Quittner AL, Accurso F, Sontag M, Koenig JM, Ittenbach RF. Trajectories of adherence to airway clearance therapy for patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(9): 1028–37. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq015. PubMed PMID: 20304772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savant AP, Britton LJ, Petren K, McColley SA, Gutierrez HH. Sustained improvement in nutritional outcomes at two paediatric cystic fibrosis centres after quality improvement collaborates. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23 Suppl 1:i81–9. Epub 2014/03/13. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002314. PubMed PMID: 24608554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freckleton RP. On the misuse of residuals in ecology: regression of residuals vs. multiple regression. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2002;71(3):542–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00618.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lechtzin N, Mayer-Hamblett N, West NE, Allgood S, Wilhelm E, Khan U, Aitken ML, Ramsey BW, Boyle MP, Mogayzel PJ, Gibson RL, Orenstein D, Milla C, Clancy JP, Antony V, Goss CH, e ICEST. Home Monitoring in CF to Identify and Treat Acute Pulmonary Exacerbations: elCE Study Results. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-21720C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siracusa CM, Weiland JL, Acton JD, Chima AK, Chini BA, Hoberman AJ, Wetzel JD, Amin RS, McPhail GL. The impact of transforming healthcare delivery on cystic fibrosis outcomes: a decade of quality improvement at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23 Suppl 1:i56–i63. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002361. PubMed PMID: 24608552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schechter M, Schmidt JH, Williams R, Norton R, Taylor D, Molzhon A Impact of a program ensuring consistent response to acute drops in lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cyst Fibros 2018. Epub July 15, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPhail GL, Acton JD, Fenchel MC, Amin RS, Seid M. Improvements in lung function outcomes in children with cystic fibrosis are associated with better nutrition, fewer chronic pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, and dornase alfa use. J Pediatr. 2008;153(6):752–7. Epub 2008/09/02. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McPhail GL, Weiland J, Acton JD, Ednick M, Chima A, VanDyke R, Fenchel MC, Amin RS, Seid M. Improving evidence-based care in cystic fibrosis through quality improvement. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(10):957–60. Epub 2010/10/06. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.178. PubMed PMID: 20921354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szczesniak RD, Su W, Brokamp C, Keogh RH, Pestian JP, Seid M, Diggle PJ, Clancy JP. Dynamic predictive probabilities to monitor rapid cystic fibrosis disease progression. Stat Med 2020;39(6):740–56. Epub 2019/12/10. doi: 10.1002/sim.8443. PubMed PMID: 31816119; PMCID: PMC7028099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders DB, Bittner RC, Rosenfeld M, Hoffman LR, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Failure to recover to baseline pulmonary function after cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbation. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2010;182(5):627–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-14210C. PubMed PMID: 20463179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann JE, Anenberg SC, Weinberger KR, Amend M, Gulati S, Crimmins A, Roman H, Fann N, Kinney PL. Estimates of Present and Future Asthma Emergency Department Visits Associated With Exposure to Oak, Birch, and Grass Pollen in the United States. Geohealth. 2019;3(1):11–27. Epub 2019/05/21. doi: 10.1029/2018GH000153. PubMed PMID: 31106285; PMCID: PMC6516486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan WJ, Butler SM, Johnson CA, Colin AA, FitzSimmons SC, Geller DE, Konstan MW, Light MJ, Rabin HR, Regelmann WE, Schidlow DV, Stokes DC, Wohl ME, Kaplowitz H, Wyatt MM, Stryker S. Epidemiologic study of cystic fibrosis: design and implementation of a prospective, multicenter, observational study of patients with cystic fibrosis in the U.S. and Canada. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28(4):231–41. Epub 1999/09/25. doi: . PubMed PMID: 10497371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice MB, Ljungman PL, Wilker EH, Dorans KS, Gold DR, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, Washko GR, O’Connor GT, Mittleman MA. Long-term exposure to traffic emissions and fine particulate matter and lung function decline in the Framingham heart study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(6):656–64. Epub 2015/01/16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-18750C. PubMed PMID: 25590631; PMCID: PMC4384780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo C, Hoek G, Chang LY, Bo Y, Lin C, Huang B, Chan TC, Tam T, Lau AKH, Lao XQ. Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) and Lung Function in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(12):127008. Epub 2019/12/25. doi: 10.1289/EHP5220. PubMed PMID: 31873044; PMCID: PMC6957275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schechter MS, Margolis PA. Relationship between socioeconomic status and disease severity in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1998;132(2):260–4. Epub 1998/03/20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70442-1. PubMed PMID: 9506638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goss CH, MacNeill SJ, Quinton HB, Marshall BC, Elbert A, Knapp EA, Petren K, Gunn E, Osmond J, Bilton D. Children and young adults with CF in the USA have better lung function compared with the UK. Thorax. 2015;70(3):229–36. Epub 2014/09/27. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205718. PubMed PMID: 25256255; PMCID: PMC4838510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molenberghs G, & Kenward M Missing data in clinical studies West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szczesniak RD, Su W, Brokamp C, Keogh RH, Pestian JP, Seid M, Diggle PJ, Clancy JP. Dynamic predictive probabilities to monitor rapid cystic fibrosis disease progression. Stat Med 2019. Epub 2019/12/10. doi: 10.1002/sim.8443. PubMed PMID: 31816119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grossoehme DH, Szczesniak RD, Britton LL, Siracusa CM, Quittner AL, Chini BA, Dimitriou SM, Seid M. Adherence Determinants in Cystic Fibrosis: Cluster Analysis of Parental Psychosocial, Religious, and/or Spiritual Factors. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12(6):838–46. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-379QC. PubMed PMID: 25803407; PMCID: PMC4590021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.