Abstract

We developed reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR assays for the detection of mRNA from three spliced genes of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), the immediate-early genes U16/U17 and U89/U90 and the late gene U60/U66. Sequence analysis determined the splicing sites of these genes. The new assays may be instrumental in investigating the association between HHV-6 and disease.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is the causative agent of exanthema subitum (10). High HHV-6 viral loads have been demonstrated in the settings of allograft rejection, immunodeficiencies, malignancies, and multiple sclerosis, although an etiological correlation is still uncertain (1). This is primarily due to the lack of sensitive diagnostic tools specific for active infection. PCR detection of viral DNA in plasma has been proposed as a marker of active infection, but its sensitivity is low (9). The aim of the present work was to develop HHV-6 reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR assays, since the expression of viral mRNA constitutes an unambiguous marker of active infection. To discriminate mRNA from genomic DNA, we focused on the detection of spliced gene expression; here we report on RT-PCR assays for the immediate-early genes U16/U17 and U89/U90 and the late gene U60/U66, as well as on the splicing patterns of these genes for both HHV-6A and HHV-6B.

HHV-6A(GS) strain was propagated in the human T-cell line HSB-2; HHV-6B(PL1) strain was propagated in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). mRNA was extracted using oligo(dT)25-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads mRNA direct kit; Dynal, Oslo, Norway), and total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Primers (Table 1) were designed based on the HHV-6(U1102) sequence (4).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR of the U89/U90, U16/U17, and U60/U66 HHV-6 genes and splice junction sites found

| Genes | Primer pair | Primer genome position | Primer sequence | Splice junction | cDNA amplimer (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate-early | |||||

| U89/U90 | HHV6 C1 | 135568–135591a | ACTTAATTAATTTGTCTTCCATGT | 135663–135771a | 120 |

| HHV6 C2 | 135771–135794a | ATGGAGAGTTGAAAACTTTAGCTG | |||

| HHV6 C1bis | 135598–135614a | GTTCCTGTTTCATGGCA | 135663–135771a | 115 | |

| 137672–137688b | |||||

| 137867–137883c | 137737–137848b | 115 | |||

| HHV6 C2bis | 135800–135819a | TCCAGTAATGTGGAAGAAGGd | |||

| 137877–137896b | 137932–138043c | 115 | |||

| 138072–138091c | |||||

| U16/U17 | HHV6 C5 | 26781–26804a | AATTTTCGTTAGAAAGCGAATGTCe | 27034–27121a | 424 |

| 27694–27717b | |||||

| 27852–27875c | 27947–28035b | 424 | |||

| HHV6 C6 | 27267–27290a | GCTAAACGATATAAAAATTGCAGTf | |||

| 28181–28204b | 28105–28193c | 424 | |||

| 28339–28362c | |||||

| Late | |||||

| U60/U66 | HHV6 C3 | 98092–98114a | GGCCGTTTTTTTAACTTCGGCGT | 98415–101614a | 442 |

| 99216–99238b | |||||

| 99381–99403c | 99539–102747b | 442 | |||

| HHV6 C4 | 101709–101731a | GTTTAAATGCCGCCGAATGTTTC | |||

| 102842–102864b | 99704–102912c | 442 | |||

| 103007–103029c |

Nucleotide positions based on the HHV-6A(U1102) strain genome.

Nucleotide positions based on the HHV-6B(HST) strain genome.

Nucleotide position based on the HHV-6B (Z29) strain genome.

Identical sequence for the HHV-6B(Z29) and HHV-6B(HST) strains. Sequence for 100% alignment in HHV-6A(U1102) strain: TCCAATAATGTAGAAGAAGG.

Identical sequence for the HHV-6A(U1102) and HHV-6B(Z29) strains. Sequence for 100% alignment in HHV-6B(HST) strain: AATTTTTGTTAAAAAGCGAATGTC.

Identical sequence for the HHV-6A(U1102) and HHV-6B(Z29) strains. Sequence for 100% alignment in HHV-6B(HST) strain: TTTAAACGATATAAAAATTGCAGT.

Poly(A)+ RNA was treated with the Access RT-PCR kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Except for primers C1bis and C2bis, initial denaturation (94°C for 2 min) was followed by 35 amplification cycles (94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min) and by final elongation (72°C for 10 min). For primers C1bis and C2bis, initial denaturation (95°C for 15 min) was followed by 40 amplification cycles (95°C for 20 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 30 s) and by final elongation (72°C for 2 min).

Total RNA samples were treated (35°C for 15 min) with RNase-free DNase (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) and then subjected to reverse transcription (36°C for 90 min) using Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Promega). One-tenth of the RT reaction mixture was added to 50 pmol of each primer, 100 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1× Perkin-Elmer buffer II, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif). Initial denaturation (95°C for 15 min) was followed by 40 amplification cycles (95°C for 20 s, 60°C [50°C for primers C1bis and C2bis] for 45 s and 72°C for 30 s) and by final elongation (72°C for 2 min).

For sequencing, amplimers were purified using the Qiaquick spin extraction kit (Qiagen), amplified, and sequenced with the primers mentioned above (Table 1; Fig. 1). The nucleotide positions of the splice junction sites and the amplimer sizes (Table 1) differed in all cases from those predicted by Gompels at al. (4).

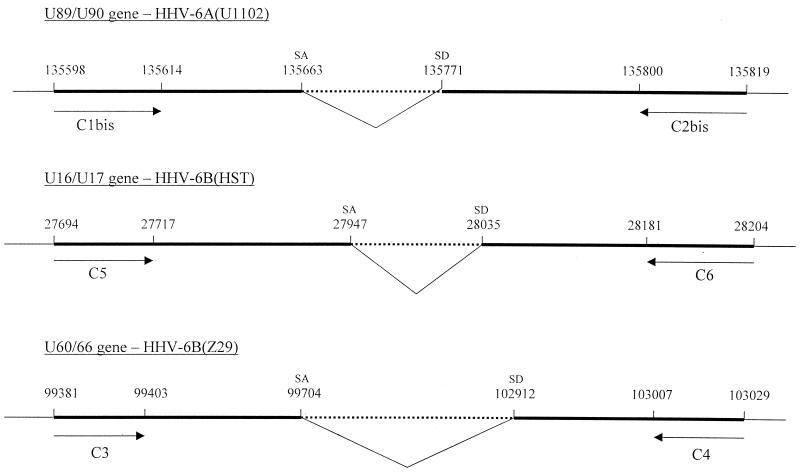

FIG. 1.

Position of the primers used for RT-PCR and of the splicing sites on the HHV-6 genome. The sequence of three different HHV-6 strains (U1102 [4], HST [5], and Z29 [2]) are aligned. The intronic sequence is indicated by a dotted line; the RT-PCR product is indicated by the bold lines. SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor (the mRNA sequence runs in the direction from SD to SA). The nucleotide positions, indicated above the lines, are not drawn to scale.

Using primers HHV6C1 and HHV6C2 for gene U89/U90, a 120-bp cDNA fragment was amplified from HHV-6A(GS) but not from HHV-6B(PL1) or uninfected cell mRNA. The observed splicing site at nucleotides 135663 to 135771 of HHV-6A(U1102) differs by 1 nucleotide from that postulated by Megaw et al. (6) at nucleotides 135664 to 135772. Our results were strengthened by the finding of the consensus GT and AG nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ boundary, respectively, of the spliced-out intronic sequence.

A second primer pair designed for U89/U90 RT-PCR, HHV6C1bis and HHV6C2bis, amplified both HHV-6A(GS) and HHV-6B(PL1) cDNA, with the same splicing pattern for both strains. In agreement with the postulated splicing pattern between exons 2 and 3 of U89/U90 (6) (exons 4 and 5 in reference 8), genomic DNA was 107 bp longer than cDNA. Mirandola et al. (7) and Flebbe-Rehwaldt et al. (3) also observed a 107-bp DNA-cDNA difference, but did not report cDNA sequence analysis.

Primer pair HHV6C5 and HHV6C6 and primer pair HHV6C3 and HHV6C4 amplified U16/U17 and U60/U66 cDNA, respectively, from both HHV-6A(GS) and HHV-6B(PL1) but not from uninfected cellular cDNA. The splicing patterns, similar for the two strains, corresponded to those proposed for U16/U17 and U60/U66 (6) and to that recently reported for HHV-6(GS) U16/U17 (3).

To evaluate sensitivity, RT-PCR was performed on total RNA extracted from serial dilutions of HHV-6(GS)-infected PBMC (8, 80, 800, 8,000, 80,000, or 800,000 cells) collected 8 days after infection (approximately 50% of cells expressed structural viral proteins) and mixed with 2 × 106 uninfected SUP-T1 cells. With all primer pairs, except HHV6C1bis and HHV6C2bis, spliced viral cDNA was detected at all dilutions of infected cells. Using primers HHV6C1bis and HHV6C2bis, spliced viral cDNA was detectable with 8,000 infected PBMC.

To assess the potential clinical usefulness of the RT-PCR assays, experiments were performed on PBMC from two cynomolgous monkeys experimentally infected with HHV-6(GS). Using the HHV6C1bis and HHV6C2bis primer pair, PBMC, taken 1, 2, and 5 weeks after infection were shown to express U89/U90 spliced mRNA. In parallel, cell-free HHV-6 DNA was detected in plasma, confirming the occurrence of active infection (data not shown). However, no U16/U17 or U60/U66 spliced mRNA could be demonstrated in the samples examined. Potential reasons for the lack of detectable mRNA from these genes include the following: (i) U16/U17 mRNA is expressed less abundantly than U89/U90 (3, 8) and (ii) rather than PBMC, the main site(s) of viral replication may be lymphoid tissue or other organs that were not sampled in this preliminary study.

In summary, we have developed RT-PCR systems for HHV-6 gene expression, which allowed us to conclusively demonstrate active infection. Furthermore, similarities in genome sequence and splicing patterns were demonstrated for the GS and U1102 strains of HHV-6A and for the PL1, Z29, and HST strains of HHV-6B (2, 5). These findings may be important in further investigations of the role of HHV-6 in the etiology and pathogenesis of human disease.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the HHV-6 cDNA sequences are as follows: HHV6A(GS) U60/U66, AF241838; HHV-6B(PL1) U60/U66, AF241837; HHV-6A(GS) U89/U90, AF241836; HHV-6B(PL1) U89/U90, AF241835; HHV-6A(GS) U16/U17, AF241839; and HHV-6B(PLI) U16/U17, AF241840.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, University of Antwerp, for technical advice and amplicon sequencing.

This work was supported by the European Commission Biomed 2 Shared Cost Project on ‘Viral Cofactors in AIDS’ (contract no. BMH4-CT96-1301 and by a grant (to P.L.) from the ISS-Rome.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campadelli-Fiume G, Mirandola P, Menotti L. Human herpesvirus 6: an emerging pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:353–366. doi: 10.3201/eid0503.990306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dominguez G, Dambaugh T R, Stamey F R, Dewhurst S, Inoue N, Pellett P E. Human herpesvirus 6B genome sequence: coding content and comparison with human herpesvirus 6A. J Virol. 1999;73:8040–8052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8040-8052.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flebbe-Rehwaldt L M, Wood C, Chandran B. Characterization of transcripts from human herpesvirus 6A strain GS immediate-early region B U16–U17 open reading frames. J Virol. 2000;74:11040–11054. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11040-11054.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gompels U A, Nicholas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson B J, Martin M E D, Efstathiou S, Craxton M, Macaulay H A. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology. 1995;209:29–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isegawa Y, Mukai T, Nakano K, Kagawa M, Chen J, Mori Y, Sunagawa T, Sashihara J, Zou P, Kosuge H, Yamanishi K. A comparison of the complete DNA sequences between human herpesvirus-6 variant A and B. J Virol. 1999;73:8053–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8053-8063.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Megaw A G, Rapaport D, Avidor B, Frenkel N, Davison A J. The DNA sequence of the RK strain of human herpesvirus 7. Virology. 1998;244:119–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirandola P, Menegazzi P, Merighi S, Ravaioli T, Cassai E, Di Luca D. Temporal mapping of transcripts in herpesvirus 6 variants. J Virol. 1998;72:3837–3844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3837-3844.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiewe U, Neipel F, Schreiner D, Fleckenstein B. Structure and transcription of an immediate-early region in the human herpesvirus 6 genome. J Virol. 1994;68:2978–2985. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2978-2985.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Secchiero P, Carrigan D R, Asano Y, Benedetti L, Crowley R W, Komaroff A L, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 in plasma of children with primary infection and immunosuppressed patients by polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:273–280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Kondo T, Asano Y, Kurata T. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthema subitum. Lancet. 1988;1:1065–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]