Abstract

Purpose:

Delivering bad news (DBN) to a patient or patient’s family is one of the most difficult tasks for physicians. As a complicated task, DBN requires better than average communication skills. This study investigated trainee’s attitude and awareness of DBN based on a self-assessment of their experiences and performance in practice. Survey subjects were also asked to assess their perception and the need for education in conducting DBN.

Methods:

A survey was carried out on their experiences with DBN, how they currently deal such situations, how they perceive such situations and the need for education and training programs. A SPIKES protocol was used to assess how they currently deal with DBN.

Results:

One hundred one residents and fellows being trained in a teaching hospital participated in the survey. Around 30% had bad experiences due to improperly delivered bad news to a patient. In terms of self-assessment of how to do DBN, over 80% of trainees assessed that they were doing DBN properly to patients, using a SPIKE protocol. As for how they perceived DBN, 90% of trainees felt more than the average level of stress when they do DBN. About 80% of trainees believed that education and training is much needed during their residency program for adequate skill development regarding DBN.

Conclusion:

We suggest that education and training on DBN may be needed for trainees during the residency program, so that they could avoid unnecessary conflict with patients and reduce stress from DBN.

Keywords: Bad news, Disclosure, Communication, Education

INTRODUCTION

Delivering bad news (DBN) is used as the term to describe the situation when unfavorable information must be disclosed to patients about their illness [1]. At some point during their careers, most physicians have to deliverbad news to patients or the patients’ family and almost always feel a burden in such situations. It is very difficult to deliver bad news, especially when it comes to talking about diseases that may result in devastating outcomes.In order to give bad news properly, good communication skills are required [2]. Good communication skills are composed of various components such as exhibiting proper speaking skills, providing satisfactory information, and showing emotional support. It is actually a complex communication task because it also requires other skills beyond the verbal component. These skills include howto respond to the patients’ emotional response, involving the patient in the decision-making process, coping with stress caused by the patients’ anticipations for treatment,the relationhip with multiple family members, and the dilemma of how to give hope properly [1]. Suchcomplexities in DBN can sometimes cause miscommunication and lead to conflict with patients or their families.Actually, several studies reported that poor communication has potentially negative outcomes for doctor-patient relationship, including discontent with care, misunderstanding of disease status and prognosis and furthermore may bring out distrust of their doctor [3,4,5].

Since Baile et al. [1,3] suggested a six–step protocol for DBN (The SPIKES protocol) in 1999, it has become a standard protocol for DBN. The SPIKES protocol consists of the following: 1) S: setting up the interview; 2) P:assessing the patient’s perception; 3) I: obtaining the patient’s invitation; 4) K: giving knowledge and information to the patient; 5) E: addressing the patient’s emotion with empathic responses; and 6) S: strategy and summary.Recently, medical ethics have become a part of the medical school curriculum and DBN is included in this curriculum.Also, some medical students learn how to deal with DBN from clinical performance examination. Until now, we have mostly focused on educating medical students, rather than trainees who actually perform DBN in practice.However, there is a continuing need for residents to learn or be trained in these skills. We don’t know how they are dealing with DBN or what they think about it. One inappropriate, unkind, or insensitive word from the doctor can be hurtful to the patient. And more recently, thereis greater emphasis on human rights, especially one’s right to know and to protect privacy. Better communication skills are becoming more significant to fulfill such standards and requirements.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate residents’ and fellows’ attitude and awareness of DBN,through a self-assessment of their experiences, and performance in DBN situations. Furthermore, we wanted to find out whether trainees would like the opportunity for education to improve communication skills for DBN.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A survey was conducted on residents and fellows in one teaching hospital located in an urban area of Korea between April and May 2013. All trainees except interns were asked to participate in the survey and the participation was voluntary without use of enforcement. Interns were excluded in this study because they have little to no experience with DBN. Consisting of six sections, the survey asked questions on the participants’ general characteristics,their experiences with DBN, how they are aware of DBN how they currently deal with DBN, how they perceive such situations and the need for education and training programs. The six-step protocol (SPIKES protocol) was used to evaluate how residents and fellows assess their own performance of DBN. Delivery style of DBN was assessed by providing them with medical scenarios that would occur.Blunt style was defined as DBN without preamble,forecasting style as preparing the patient for DBN, and stalling style as avoiding DBN [6]. The survey used a 5 scale system for paicipants to give their answers to the questions. The data from each survey were pooled into an Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) to be reported descriptively in terms of percentage for all the answers for each question. The study protocol was approved by the hospitals’ Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board. SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used to generate univariate statistics for categorical measures. Between group analyses were performed by t-tests and one-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

1. Participants’ characteristics

One hundred one out of a total of 128 trainees (79%)in the hospital participated (Table 1). Fifty-nine were male, and the remaining 42 were female. Thirty-nine participants were between the ages of 20 to 29, while 62 participants were between 30 and 39 years old.Ninety-two out of 101 participants (91%) were educated in medical school, and the remaining 9 of them (9%) were educated at the graduate school of medicine.Ninety-two percent of participants were in the residency and the rest of them were in the fellowship program.Trainees in all departments participated except for the department of radiology, laboratory medicine, pathology,anesthesiology, and plastic surgery.

Table 1.

Participants’ Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 59 (58.2) |

| Female | 42 (41.8) |

| Median age (range) (yr) | |

| 25-30 | 39 (38.6) |

| 30-35 | 62 (61.4) |

| Medical educations | |

| College of Medicine | 92 (91.1) |

| Graduate School of Medicine | 9 (7.9) |

| Training department | |

| Dermatology | 4 (3.9) |

| Emergency Medicine | 5 (4.9) |

| Family Medicine | 9 (8.9) |

| General Surgery | 6 (5.9) |

| Gynecology/Obstetrics | 2 (1.9) |

| Internal Medicine | 27 (26.7) |

| Neurology | 4 (3.9) |

| Neuropsychiatry | 8 (7.9) |

| Neurosurgery | 4 (3.9) |

| Ophthalmology | 7 (7.8) |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 9 (8.9) |

| Otolaryngology | 4 (3.9) |

| Pediatrics | 7 (7.8) |

| Rehabilitation Medicine | 5 (4.9) |

| Level of training | |

| The first year | 26 (25.7) |

| The second year | 24 (23.8) |

| The third year | 24 (23.8) |

| The fourth year | 19 (18.8) |

| The fellowship | 8 (7.9) |

2. Education and experience in DBN

Participants were asked about their education and experiences in DBN (Table 2). Trainees who ever received any education for DBN were 63.4% and the majority of them (95%) had received it from the medical ethicscurriculum in medical school. Ninety-four trainees (93.1%)had actual experience DBN to patients or their families.Among them, 29.7% had undergone bad experiences due to improperly delivered bad news to a patient.

Table 2.

Education and Experience of Delivering Bad News

| A. Questions | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Have you ever received any education for “delivering bad news”? | |

| Yes | 64 (63.4) |

| No | 37 (36.6) |

| 2. Where did you receive education for “delivering bad news”? | |

| 1) In medical school, while learning about medical ethics | 60 (95) |

| 2) During seminars or education programs for residents | 1 (0.015) |

| 3) On the internet or through mass media | |

| 4) By senior residents or staff | |

| 5) Other | 2 (0.03) |

| 3. Have you ever delivered bad news to patients or patients’ family? | |

| Yes | 94 (93.1) |

| No | 7 (6.9) |

| 4. Do you have any bad experiences due to improperly delivered bad news? | |

| Yes | 30 (29.7) |

| No | 71 (70.3) |

3. How are trainees aware of DBN?

Eighty–eight percent of trainees preferred to talk to the patient’s family, instead of talking to the patient directly.Fifty-eight percent of trainees believed that bad news should be delivered directly to a patient; however, the remaining 42% believed that it should not be delivered directly to the patient (Table 3). We could not find any difference in awareness between male and female trainees. And we did not notice any difference in awareness between age range in 20s and 30s.

Table 3.

How Are Trainees Aware of Delivering Bad News?

| B. Questions | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Do you prefer to talk with a patient or the family members when you deliver bad news? | |

| Patients | 11 (10.9) |

| Patients’ family | 89 (88.1) |

| 2. Do you believe that bad news should be delivered directly to the patient? | |

| Yes | 59 (58.4) |

| No | 42 (41.6) |

4. How do trainees assess their own performance on DBN?

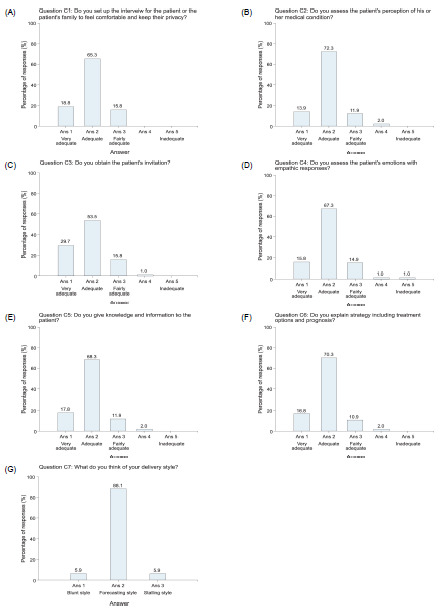

In order to evaluate how trainees assess their own performance on DBN, self-assessment was performed according to a SPIKES protocol (Table 4, Question C;Fig. 1). On whether they were setting up an appropriate environment for patient privacy and comfort, 19% responded that they were very adequate, with 65% responding adequate. In assessing the patient’s perception of his or her medical condition, 85% of trainees answered that they were very adequate or adequate. In obtaining the patient’s invitation to disclose the details of the medical condition, 30% of trainees replied that they were very adequate, with another 54%adequate. In assessing the patient’s emotions with mpathic responses, 83% replied as being very adequate to adequate. In providing knowledge and information to the patient, 86% of trainees responded that they were very adequate or adequate. On explaining future strategies including treatment options and prognosis, 88% answered as being very adequate to adequate. Three categories were given to desribe their style of delivery according to Shaw et al.’s publication [6]: blunt, forecasting, and stalling. Six percent of responders reported that they were blunt, while 6% were stallers and 88% were forecasters. Surprisingly, there was no difference in the percentage of adequacy in delivery skills between trainees with experience and those without, and between residents and fellows (data not shown). And, we could not find any difference in the percentage of adequacy in delivery skills between trainees who had received education and those without it (data not shown).

Table 4.

Survey Contents

| C. Questions on how bad news is being delivered (self-assessment) |

| 1. Do you set up the interview for the patient to feel comfortable and keep privacy? |

| 2. Do you assess the patient’s perception of his or her medical condition? |

| 3. Do you obtain the patient’s invitation? |

| 4. Do you assess the patient’s emotions with empathic responses? |

| 5. Do you give knowledge and information to the patient? |

| 6. Do you explain future strategy including treatment options and prognosis? |

| 7. What do you think of your delivery style? |

| D. Questions on how the situation of delivering bad news is perceived |

| 1. Do you feel stressful when you deliver bad news to the patient or the patients’ family? |

| 2. Do you believe that you can do better if you have more experience of delivering bad news? |

| 3. Do you believe that you can do better delivering bad news when you become a senior resident? |

| 4. Do you believe that you may be less stressed if you have more experience of delivering bad news? |

| E. Questions regarding the need for education/training program |

| 1. Do you feel that training is needed for adequate skill development in “delivering bad news” during your residency program? |

| 2. Are you willing to attend the training or education if you have the opportunity? |

Fig. 1. Survey Results: Questions on How Bad News Is Being Delivered.

(A) Question C1, (B) Question C2, (C) Question C3, (D) Question C4, (E) Question C5, (F) Question C6, (G) Question C7.

5. How do trainees perceive DBN?

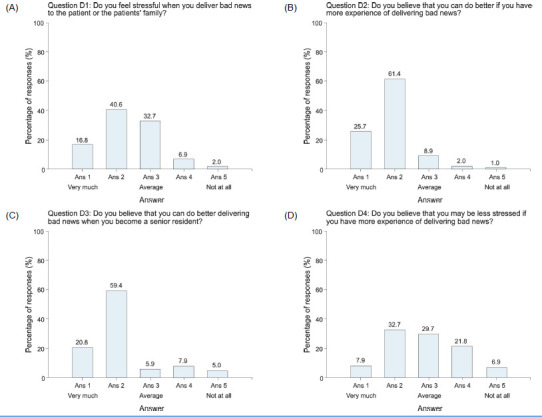

Questions were asked about how trainees perceive DBN (Table 4, Question D; Fig. 2). Ninety percent of trainees feel more than the average level of stress when they deliver bad news. Eighty-eight percent of them believed that they would do much better if they had more experience with DBN. Also, 81% of them thoughtthat they would be much better at DBN when they become senior residents. Forty-one percent of trainees believed that stress would be lessened with more experience with DBN; however, 30% of them still believed that stress would not be lessened with it. There was no difference in the level of stress between trainees with experience and those without experience (data not shown). Interestingly, there was slight difference in the level of stress between trainees who had received education and those without it, and there was a tendency to have less stress for trainees who had receivededucation than those without it, but, it was not statistically significant.

Fig. 2. Survey Results: Questions on How the Situation of Delivering Bad News Is Perceived.

(A) Question D1, (B) Question D2, (C) Question D3, (D) Question D4.

6. The need for an education and training program

Eight-one percent of trainees believed that a training program is needed to develop adequate skills for DBN during their residency program. Sixty-eight percent of them were willing to receive education and training if they have an opportunity (Table 4, Question E).

DISCUSSION

A six-step protocol (SPIKES protocol) was developed for the clinician to fulfill the four most important aims of an interview breaking bad news: collecting information from the patient, giving medical information,supporting the patient’s emotion, and deriving the patient’s cooperation in a future management plan [1]. In our study, over 80% of trainees assessed that they followed the SPIKES protocol. However, we need to pay attention to the result that 30% of trainees in this study have bad experiences due to improper DBN, suggesting that their current strategies for DBN may not be as adequate as they would like it to be. Interestingly, the majority of trainees were reluctant to give bad news to the patient directly, because most families of the patient don’t want to let the patient know before he or she is ready to hear it. In fact, more than half of the trainee believed that they don’t need to do DBN directly to the patient. We think this might have relevance to the cultural background. The concept of family in our society is that the family can deal with the patient’s situation and make decisions for him or her, while the patient’s own right to information and choices are regarded secondary. For delivery style, 88% of responders thought they were forecasters, suggesting that they at least let the patient prepare for DBN.

As experienced oncologists, DBN has been a difficult and stressful task. When cancer is diagnosed, relapsed,and progressed despite treatment, patients and their families are advised to prepare the next steps. Whenever we face these circumstances, we always feel stressed and think about ways to deliver the news properly to somehow make the experience less traumatic for the patient. Similarly, many trainees like residents and fellows are also challenged and stressed out about performing DBN. The reason for this may be that the clinician feels a sense of failure for not providing the patient’s expectations or is troubled by not knowing how to give hope in the circumstance of a poor prognosis [3].Our study also revealed that 90% of trainees feel more than the average level of stress when they do DBN. Can more experience help to do DBN better? In our study,88% of trainees believed that they can do much better with more experience. We also think that more experience is helpful, but that can’t solve everything.

Needless to say, DBN can be improved by education and training. Two workshops were held at the MD Anderson Cancer Center to teach about how to deliver bad news and how to handle difficult patients. Participants achieved positive results regarding “feeling morecompetent” about negotiating these encounters [7]. There was a report that the majority of attendees who were faculty and oncology fellows increased confidence in DBN and managing difficult situations after attending educational program [3]. There was a communication skills training workshop for Chinese oncologists and caretakers about DBN. In this workshop, training was performed through group discussion and role play in small groups. After the workshop, physician felts significantly better in talking about diagnosis, prognosis, and death with patient and family [8]. How to train communication skills effectively? A study was conducted to assess medical students’ individual versus group training in DBN. According to this study, active involvement throughsimulated patient interview is more effective to achieve training goal and there were markedly differences between students performing an interview and students observing interviews, indicating that observational education may not be sufficient to increase DBN skills [9]. A similar study was performed in Korea. It was a study on teaching DBN using the SPIKES protocol with standardized patients during clerkship of medical students. In this study, self–confidence for DBN was improved, but clinical performance was not improved after education program, suggesting that communication skills training must be repeatedly performed [10]. In our study, most of the residents and fellows responded that chances of learning about DBN were given in medical school as a part of the curriculum on medical ethics.After graduation, the subject of DBN is no longer discussed. Some trainees face conflict with patients or their families that would not have occurred with adequate communication skills. In our study, about 80% of traines believed that the training for adequate skills development in regards to DBN was much needed during their residency program. According to a report by Hebertet al. [2], an e-mail survey to all hematology/oncology fellowship program directors in the United States showed that 63% of program directors felt that extensive,formal training for oncology fellows is important for skill development in DBN. However, the situation in Korea may be different from the United States in that residents are in charge of primary care for hospitalized patients. This is why education and training is considered to be necessary for residents as well as fellows.

Our study has clear limitations. Based on a questionnaire in which trainees assessed their own performance,this study may not be appropriate to consider an objective assessment of DBN. In the future, we may need more objective analysis to assess trainees’ attitude and skills for DBN, using video observation or standardized patients or actual patients in practice, and perhaps have a third party observer’s assessment. And it may not be enough to say that trainees need to be educated with this survey as this represents the results of a survey at a single hospital. Therefore, a cohort study with more trainees may be needed to assess whether education or training for DBN is needed in the residency program and furthermore to develop the effective educational program for communication skills.

In conclusion, our study suggests that education and training may be needed for trainees during their residency programs to improve skills for DBN, and to help reduce their stress from DBN. However, further research is needed for a more objective assessment of the current situation in practice, and also in finding ways to provide trainees with education.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert HD, Butera JN, Castillo J, Mega AE. Are we training our fellows adequately in delivering bad news to patients? A survey of hematology/oncology program directors. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1119–1124. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baile WF, Kudelka AP, Beale EA, Glober GA, Myers EG, Greisinger AJ, Bast RC, Jr, Goldstein MG, Novack D, Lenzi R. Communication skills training in oncology: description and preliminary outcomes of workshops on breaking bad news and managing patient reactions to illness. Cancer. 1999;86:887–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lind SE, DelVecchio Good MJ, Seidel S, Csordas T, Good BJ. Telling the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:583–589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan A, Woodruff RK. Communicating with patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care. 1997;13:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw J, Dunn S, Heinrich P. Managing the delivery of bad news: an in-depth analysis of doctors' delivery style. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland JC, Almanza J. Giving bad news: is there a kinder, gentler way? Cancer. 1999;86:738–740. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990901)86:5<738::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wuensch A, Tang L, Goelz T, Zhang Y, Stubenrauch S, Song L, Hong Y, Zhang H, Wirsching M, Fritzsche K. Breaking bad news in China: the dilemma of patients' autonomy and traditional norms. A first communication skills training for Chinese oncologists and caretakers. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1192–1195. doi: 10.1002/pon.3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stiefel F, Bourquin C, Layat C, Vadot S, Bonvin R, Berney A. Medical students' skills and needs for training in breaking bad news. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:187–191. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SH, Choi YS, Lee YM, Kim DG, Kim JA. Teaching ‘breaking bad news’ based on SPIKES protocol during family medicine clerkship. Korean J Med Educ. 2006;18:55–64. [Google Scholar]