Abstract

Early insults associated with cardiac transplantation increase the immunogenicity of donor microvascular endothelial cells (ECs), which interact with recipient alloreactive memory T cells and promote responses leading to allograft rejection. Thus, modulating EC immunogenicity could potentially alter T cell responses. Recent studies have shown modulating mitochondrial fusion/fission alters immune cell phenotype. Here, we assess whether modulating mitochondrial fusion/fission reduces EC immunogenicity and alters EC‐T cell interactions. By knocking down DRP1, a mitochondrial fission protein, or by using the small molecules M1, a fusion promoter, and Mdivi1, a fission inhibitor, we demonstrate that promoting mitochondrial fusion reduced EC immunogenicity to allogeneic CD8+ T cells, shown by decreased T cell cytotoxic proteins, decreased EC VCAM‐1, MHC‐I expression, and increased PD‐L1 expression. Co‐cultured T cells also displayed decreased memory frequencies and Ki‐67 proliferative index. For in vivo significance, we used a novel murine brain‐dead donor transplant model. Balb/c hearts pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 after brain‐death induction were heterotopically transplanted into C57BL/6 recipients. We demonstrate that, in line with our in vitro studies, M1/Mdivi1 pretreatment protected cardiac allografts from injury, decreased infiltrating T cell production of cytotoxic proteins, and prolonged allograft survival. Collectively, our data show promoting mitochondrial fusion in donor ECs mitigates recipient T cell responses and leads to significantly improved cardiac transplant survival.

Keywords: animal models: murine, basic (laboratory) research/science, heart transplantation/cardiology, immunobiology, immunosuppression/immune modulation, ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI), rejection: acute, rejection: T cell mediated (TCMR), translational research/science

Therapeutic promotion of endothelial mitochondrial fusion reduces allo‐reactive T‐cell responses and improves cardiac allograft survival. Mullan comments on page 337.

Abbreviations

- BD

brain death

- CS

cold storage

- CS‐IRI

cold storage‐ischemia reperfusion injury

- DRP1

dynamin‐related protein 1

- DRP1KD

dynamin‐related protein 1 knock‐down cell

- EC

endothelial cell

- IRI

ischemia‐reperfusion injury

- MCEC

microvascular cardiac endothelial cell

- mPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- MUSC

Medical University of South Carolina

- NAC

N‐acetylcysteine

- Tmems

memory T cells

- UW solution

University of Wisconsin solution

- VDAC‐1

voltage‐dependent anion channel‐1

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite the steady advancement of cardiac transplantation, long‐term survival has not significantly improved due to early factors in the transplant process. 1 , 2 , 3 Donor brain death (BD) activates multiple immunological components and predisposes a cardiac allograft to pro‐inflammation. 4 , 5 , 6 Subsequently, cold storage (CS) and ischemia‐reperfusion injury (IRI) further exacerbate the heightened immunogenicity of the allograft. 7 Sitting at the interface between the donor allograft and the recipient immune system are donor endothelial cells (ECs), which play a central role in an allograft's immunogenicity as semi‐professional antigen‐presenting cells. 8 Early injuries induced by BD, CS, and IRI activate and prime these cells to be immunogenic. Upon allograft implantation and reperfusion, ECs interact with recipient circulating alloreactive memory T cells (Tmems) which subsequently infiltrate the cardiac allograft and mediate allograft rejection. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15

Current standard‐of‐care immunosuppression prevents activation of naïve T cells but has minimal impact on Tmems, and thus Tmems are a barrier to transplant tolerance. 16 , 17 , 18 Since Tmems interact directly with ECs, 11 modulating the immunogenicity of donor ECs early in the transplant process could potentially reduce alloreactive Tmems responses. Also, treating a cardiac allograft prior to recipient implantation could potentially minimize side effects in the recipient.

Several studies have shown an important link between mitochondrial dysregulation and allograft rejection. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Mitochondrial fusion/fission plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial fitness and cellular health. Fusion is mediated by several key machinery proteins, including mitofusin‐1, mitofusin‐2, and optic atrophy‐1. Fission, on the other hand, is mediated by dynamin‐related protein 1 (DRP1) and other accessory proteins. 27 , 28 In transplantation, CS‐IRI affects expression and processing of fusion/fission machinery proteins, leading to mitochondrial injury and impaired graft function. 29 However, whether these alterations in donor graft mitochondrial fusion/fission has an impact on immunological outcomes remains unknown.

In non‐transplant settings, mitochondrial fusion/fission has been shown to regulate immune cell phenotype, including dendritic cell differentiation and migration, 30 and effector‐memory functional transformation in T cells. 31 Yet, whether mitochondrial fusion/fission regulates the immunological phenotype of ECs has not been reported. Furthermore, in the heart, modulating mitochondrial fusion/fission exhibits protective effects against focal IRI. In myocardial infarction mouse models, inhibiting mitochondrial fission stabilizes the cardiac microvasculature, maintains an intact endothelial barrier, and protects mitochondrial membrane potentials of ECs. 32 , 33 , 34 Yet, whether inhibiting mitochondrial fission/promoting mitochondrial fusion provides protection against injury in transplant has not been investigated.

We have previously shown that modulating mitochondrial bioenergetics in ECs reduces their immunogenicity and leads to a favorable T cell response. 35 Based on these observations, we hypothesized that modulating mitochondrial fusion/fission in donor ECs will provide protection from IRI and promote an EC immunological phenotype that decreases Tmems responses. In this study, using in vitro and in vivo models, we promote mitochondrial fusion/inhibit mitochondrial fission in donor ECs and assess the impact on EC‐T cell interactions and subsequent cardiac transplant outcomes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

Male Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice, 8–12 weeks old (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), were used for all co‐culture and in vivo experiments. Mice were housed under conventional conditions at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC, Charleston, SC). All procedures were performed accordingly to animal protocols approved by MUSC Committee for Animal Research in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Additional materials and methods

Details regarding cell lines and culture media, pharmacologic agents, confocal imaging, antibodies for immunoblotting and flow cytometry, oxygen consumption assay, memory CD8+ T cells generation and EC‐T‐cell co‐culture, CS and warm reperfusion model, normothermic activation model, live/dead cell staining and counting, brain‐death induction and heterotopic heart transplantation, primary cell isolation, transmission electron microscopy, trans‐endothelial electrical resistance assays, cardiac injury assessment, histological analysis, and statistical analysis can be found in the online Supporting Information.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Genetic alteration of mitochondrial fission machinery reduces cardiac microvascular EC immunogenicity

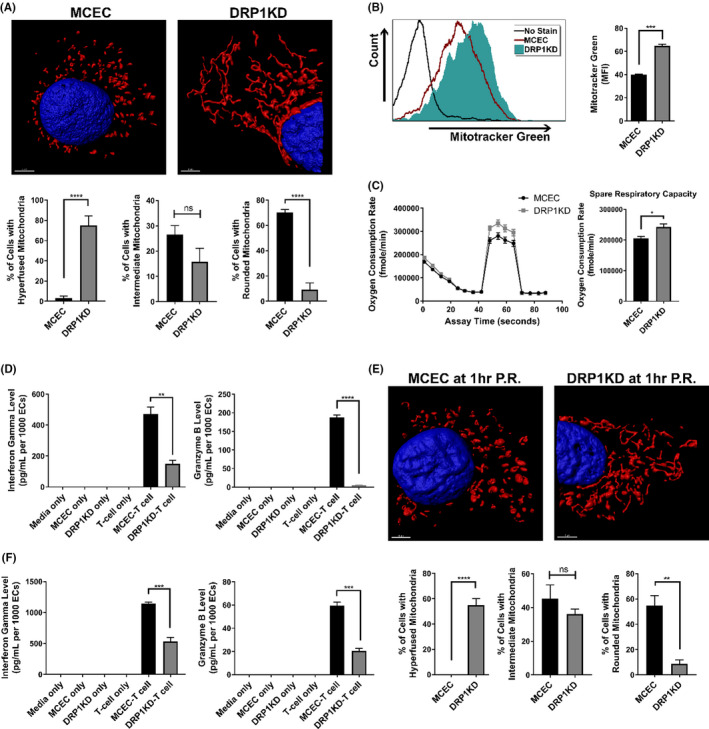

With previous reports indicating that inhibiting mitochondrial fission to promote fusion can modulate the immunological phenotypes of T cells and mast cells, 31 , 36 we reasoned that inhibiting mitochondrial fission in ECs would alter their immunogenicity. To determine the impact of mitochondrial fission inhibition in ECs, we generated DRP1 knock‐down cells (DRP1KDs) by stably transfecting mouse microvascular cardiac endothelial cells (MCECs) with shRNAi plasmid, and subsequently maintained selection media. Fission machinery knock‐down was validated by DRP1KD mitochondrial morphology imaging, which revealed significant elongation of the mitochondria as compared to wildtype MCECs (Figure 1A). Additionally, DRP1 levels in DRP1KDs were reduced compared to wildtype MCECs, as determined by Western blotting (Figure S1). To determine what other impact DRP1 knock‐down had on the mitochondria, we assessed mitochondrial mass of DRP1KDs, with Mitotracker Green as previously described. 37 Inhibiting fission was known to increase mitochondrial mass in immune cells, 31 and consistent with this study, we found that DRP1KDs had a significantly increase in mitochondrial mass compared to wildtype MCECs (Figure 1B). To determine whether these mitochondrial structural changes affected function, we utilized Seahorse bioenergetic flux assays and demonstrated that mitochondrial fitness, represented by spare respiratory capacity, in DRP1KDs was significantly increased as compared to wildtype controls (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Genetic alteration of mitochondrial fission machinery reduces EC immunogenicity. (A) Representative 3D confocal images showing mitochondrial elongation in ECs that have dynamin‐related protein 1 (DRP1) knocked down (referred to as DRP1KDs) (red: mitochondria, blue: nuclei), and quantification of mitochondrial morphology in cells (hyperfused: at least one mitochondria ≥5 μm in length, intermediate: at least one mitochondria between 5 and 2 μm but none more than 5 μm, rounded: none longer than 2 μm) (n = 4 with 80 cells/group). (B) Mitochondrial mass of DRP1KD versus MCEC (the wildtype control) quantified by flow cytometry for mean fluorescence intensity of Mitotracker Green (n = 3). (C) Mitochondrial fitness of DRP1KD versus MCEC assessed by Seahorse flux assay (n = 4). (D) Immunogenicity of DRP1KD versus MCEC when being co‐cultured with allogeneic CD8+ T cells, demonstrated by supernatant levels of interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels after 7 days of coculturing (n = 3). (E) Representative 3D confocal images showing mitochondrial elongation is unchanged at 1 h post‐reperfusion in DRP1KDs that were subjected to static cold storage for 6 h prior to reperfusion with warm media (red: mitochondria, blue: nuclei), and quantification of mitochondrial morphology performed as in Figure 1A (n = 4 with 80 cells/group). (F) Immunogenicity of DRP1KD versus MCEC that were subjected to cold storage for 6 h prior to reperfusion with warm media and co‐cultured with allogeneic CD8+ T cells, demonstrated by supernatant levels of interferon gamma and granzyme‐B after 7 days of coculturing (n = 3). (****p < .0001, ***p < .005, **p < .01, *p < .05. Differences between DRP1KD versus MCEC were analyzed using Student's t‐test. In panels D and F, granzyme‐B and interferon gamma levels were normalized to the number of ECs at the initiation of co‐culture to account for target differences)

We next sought to determine whether knocking down DRP1 altered EC immunogenicity, and specifically whether these changes altered EC‐T‐cell interactions. We utilized a previously reported EC‐T cell co‐culture system in which T cells were procured from mice that had been pre‐sensitized to donor ECs, thus recapitulating the in vivo scenario of pre‐sensitized Tmems. 35 , 38 We have shown that co‐cultures using T cells from non‐sensitized animals showed little to no alloreactivity (Figure S2). Using this normothermic co‐culture model with pre‐sensitized allogeneic CD8+ T cells, in which DRP1KDs or wildtype MCECs were co‐cultured with CD8+ T cells for 7 days, DRP1 knock‐down was associated with a marked reduction in secreted IFNγ and granzyme‐B (Figure 1D). In the clinical setting, cold storage‐ischemia reperfusion injury (CS‐IRI) associated with cardiac hypothermic preservation exacerbates EC immunogenicity. 7 Thus, we subsequently examined whether an EC immunogenicity reduction would be similarly observed in the setting of hypothermic preservation. Using a clinically relevant CS‐IRI model described previously, 35 we first assessed DRP1KD mitochondrial morphology at 1 h post‐reperfusion following CS in UW solution, and found mitochondrial morphology was unaltered by CS (Figure 1E). To dissect the impact of EC immunogenicity, after 6 h of CS and upon reperfusion, DRP1KDs or wildtype MCECs were co‐cultured with pre‐sensitized allogeneic CD8+ T cells for 7 days, as described above. In keeping with our normothermic data, IFNγ and granzyme‐B were significantly reduced in DRP1KD versus wildtype MCEC co‐cultures (Figure 1F).

3.2. Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission prior to pro‐inflammatory cytokine insult reduces EC immunogenicity

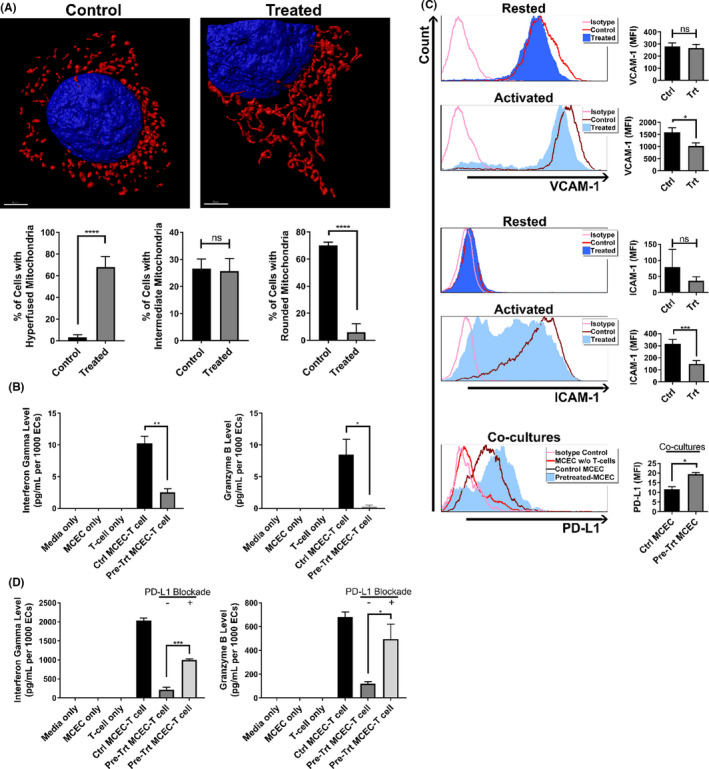

For clinical relevance, we determined whether pharmacological modulation of mitochondria in MCECs could recapitulate outcomes seen in DRP1KDs. Here, MCEC mitochondrial fusion was forced using M1, a mitochondrial fusion promoter, and Mdivi1, a mitochondrial fission inhibitor that blocks the self‐assembly of DRP1. This combination has been reported to maximally skew mitochondrial fusion/fission toward fusion. 31 , 32 When MCECs were treated with M1/Mdivi1 for 24 h, mitochondria were significantly elongated compared to untreated controls, as determined by confocal microscopy analysis (Figure 2A). To similarly determine the impact of mitochondrial therapy on MCEC immunogenicity, we repeated the co‐culture experiments with pre‐sensitized allogeneic CD8+ T cells. In keeping with our DRP1KD data, secretion of IFNγ and granzyme‐B were significantly decreased in co‐cultures where MCECs were pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 compared to untreated controls (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission prior to pro‐inflammatory cytokine insult reduces EC immunogenicity. (A) Representative 3D confocal images showing mitochondrial elongation in M1/Mdivi1‐treated MCECs (red: mitochondria, blue: nuclei), and quantification of mitochondrial morphology performed as in Figure 1A (n = 4 with 80 cells/group). (B) Immunogenicity of M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated cells versus untreated control co‐cultured with allogeneic CD8+ T cells, demonstrated by supernatant interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels after 7 days of coculturing (n = 3). (C) VCAM‐1, ICAM‐1 adhesion molecules expression on the surface of MCECs pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 for 24 h versus untreated control prior to activation by TNFα/IFNγ (n = 4), and PD‐L1 expression on the surface of M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs after 4 days co‐cultured with CD8+ T cells (n = 3). (D) Abrogation of tolerogenic effect induced by M1/Mdivi1 when PD‐L1 is blocked, demonstrated by supernatant interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels after 7 days of co‐culturing in the presence of anti‐PD‐L1 blocking antibodies (n = 3). (****p < .0001, ***p < .005, **p < .01, *p < .05. Differences between untreated control and M1/Mdivi1‐treated groups, as well as between PD‐L1‐unblocked control and PD‐L1‐blocked groups, were analyzed using Student's t‐test. In panels B and D, granzyme‐B and interferon gamma levels were normalized to the number of ECs at the initiation of co‐culture to account for target differences)

In the clinical setting, IRI promotes the secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines by innate immune cells, and within this pro‐inflammatory microenvironment, ECs are activated to become immunogenic. 39 To investigate whether promoting fusion/inhibiting fission prior to such pro‐inflammatory cytokine insult could prevent EC immunogenicity, we pretreated MCECs with M1/Mdivi1, activated them with TNFα/IFNγ, and performed flow cytometry for EC surface markers (gating strategy and live/dead staining shown in Figure S3A). While M1/Mdivi1 treatment induced no changes when cells were in their resting state, pre‐treating cells with the mitochondrial drugs prior to TNFα/IFNγ activation reduced surface expression of the adhesion molecules VCAM‐1 and ICAM‐1 compared to untreated controls (Figure 2C). Other EC activation and T cell inhibition markers, including P‐selectin, CD80, PD‐L1 did not show any discernable differences following TNFα/IFNγ activation. Given these basal data, we next determined whether T cell co‐culture altered EC activation markers after 4 days co‐cultured with allogeneic CD8+ T cells. We found that PD‐L1 was significantly up‐regulated in the M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs compared to the untreated controls (Figure 2C). Since PD‐L1 inhibits T cell function, 40 we investigated whether PD‐L1 expression changes were responsible for the observed inhibition of T cell activity. Using our co‐culture model, M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs were co‐incubated with allogeneic CD8+ T cells in the presence of anti‐PD‐L1 blocking antibodies, which resulted in the previously observed effect being partially abrogated (Figure 2D).

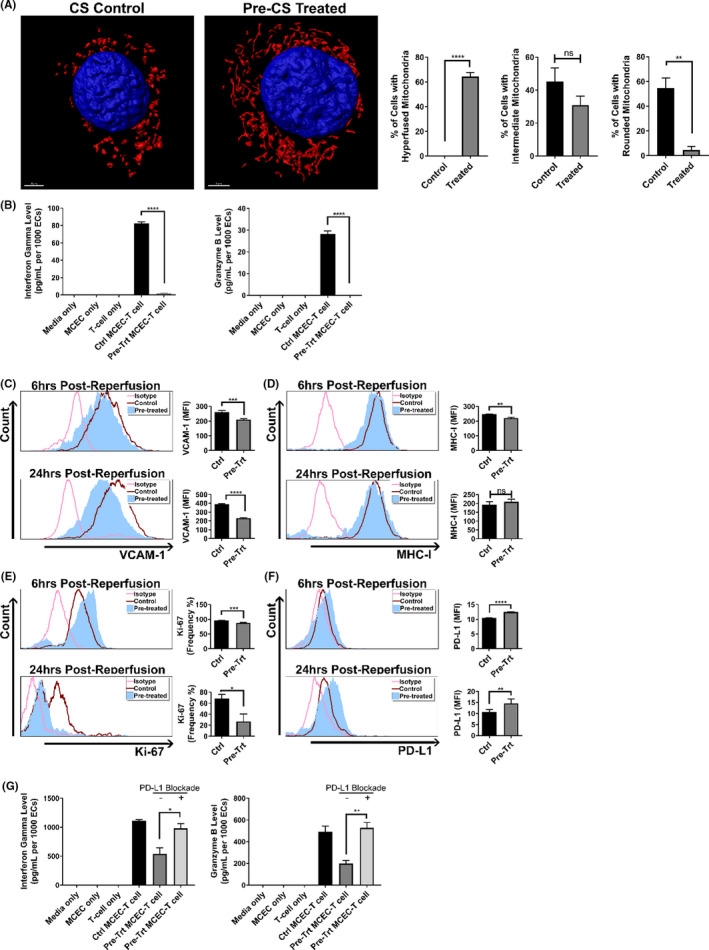

3.3. Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission prior to cold storage reduces EC immunogenicity after reperfusion

As M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment reduced EC immunogenicity to allogeneic T cells, we next investigated whether the same effects could be observed, for clinical translational relevance, in a CS‐IRI setting. In this clinically relevant model, we pretreated MCECs with M1/Mdivi1 for 6 h in warm culture media, withdrew the drugs, then subjected the cells to CS‐IRI. 35 As a means of validation, at 1‐h post‐reperfusion, we imaged MCEC mitochondria and found that mitochondria in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated cells retained an elongated morphology compared to CS controls (i.e., untreated cells undergoing CS‐IRI) (Figure 3A). To assess immunogenicity, upon reperfusion, we co‐incubated M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs or untreated controls with pre‐sensitized allogeneic CD8+ T cells for 7 days. At the end of the co‐culture, we found the levels of secreted IFNγ and granzyme‐B were significantly reduced in pretreated cells compared to untreated controls (Figure 3B). Of note, IFNγ and granzyme‐B levels in the control groups in the more translationally relevant CS‐IRI model were higher, as compared to those in the control groups of the normothermic cytokine‐insult model. Yet, M1/Mdivi1 EC pretreatment still significantly reduced IFNγ and granzyme‐B secretion by T cells to similar extents (Figures 2B and 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission prior to cold storage reduces EC immunogenicity after reperfusion. (A) Representative 3D confocal images showing mitochondrial elongation is still retained at 1 h post‐reperfusion in MCECs pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 normothermically prior to 6‐h cold storage and warm reperfusion (red: mitochondria, blue: nuclei), and quantification of mitochondrial morphology performed as in Figure 1A (n = 4 with 80 cells/group). (B) Immunogenicity of MCECs pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 normothermically prior to 6‐h cold storage and warm reperfusion, followed by co‐culture with allogeneic CD8+ T cells, demonstrated by supernatant interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels after 7 days of coculturing (n = 3). Surface expression of VCAM‐1 (C), MHC‐I (D), intracellular expression of Ki‐67 (E), and surface expression of PD‐L1 (F) at 6 h (top) and 24 h (bottom) post‐reperfusion in MCECs pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 normothermically prior to 6‐h cold storage and warm reperfusion (n = 3–6). (G) Abrogation of tolerogenic effect induced by pre‐cold storage M1/Mdivi1 treatment when PD‐L1 is blocked, demonstrated by supernatant interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels after 7 days of coculturing in the presence of anti‐PD‐L1 blocking antibodies (n = 3). (****p < .0001, ***p < .005, **p < .01, *p < .05. Differences between untreated control and M1/Mdivi1‐treated groups, as well as between PD‐L1‐unblocked control and PD‐L1‐blocked groups, were analyzed using Student's t‐test. In panels B and G, interferon gamma and granzyme‐B levels were normalized to the number of ECs at the initiation of co‐culture to account for target differences)

As promoting fusion/inhibiting fission with M1/Mdivi1 was observed to alter MCEC surface markers in the normothermic model, we sought to determine whether the same effects occurred in the CS‐IRI model. Since we have previously shown that following CS‐IRI, mitochondrial physiology and the associated immunological changes of ECs occur during the first 24 h post‐reperfusion, 35 we chose 6 and 24 h post‐reperfusion as our main focus. We performed flow cytometry on a panel of surface markers and the proliferative index Ki‐67 (gating strategy and live/dead staining shown in Figure S3A), and found that at 6 h post‐reperfusion, VCAM‐1, MHC‐I, Ki‐67 were significantly decreased, while PD‐L1 was significantly increased. These effects were more pronounced at 24 h post‐reperfusion, except that MHC‐I levels returned to normal at this time point (Table 1; Figure 3C–F). There were no significant changes associated with other markers, including ICAM‐1, P‐selectin, CD80 (Table 1). Of note, M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment did not impact MCEC viability, as shown by fluorescent cell counts with acridine orange/propidium iodide differential staining (Figure S3B). We further delineated PD‐L1 implication in our model with PD‐L1 blockade experiments using the co‐culture model described above in Figure 3B, in which following reperfusion we co‐incubated pretreated MCECs and allogeneic CD8+ T cells in the presence of anti‐PD‐L1 antibodies. We found that PD‐L1 blockade completely abrogated M1/Mdivi1 effects (Figure 3G). Given MCECs at baseline have some PD‐L1 expression, and to control for any direct impact of PD‐L1 blockade on EC‐T cell interactions, we treated control MCECs in simulated CS‐IRI model with PD‐L1 blockade. As anticipated, we could not demonstrate any impact of PD‐L1 blockade on EC immunogenicity in our control MCEC‐T cell co‐cultures (Figure S4).

TABLE 1.

Summary of MFI of surface markers and proliferative index at 6 and 24 h post‐reperfusion in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs or untreated controls (n = 3, ****p < .0001, ***p < .005, **p < .01, *p < .05)

| Molecule name | 6 h post‐reperfusion | 24 h post‐reperfusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control (MFI) | Pretreated cells (MFI) | Untreated control (MFI) | Pretreated cells (MFI) | |

| VCAM‐1 | 262.60 ± 9.97 | 210.70 ± 4.92*** | 391.10 ± 5.72 | 232.20 ± 5.50**** |

| ICAM‐1 | 20.16 ± 1.84 | 27.68 ± 8.37 | 14.73 ± 0.15 | 15.29 ± 0.31 |

| P‐selectin | 18.20 ± 0.06 | 18.85 ± 0.20 | 12.54 ± 0.38 | 13.51 ± 0.08 |

| CD80 | 50.58 ± 0.18 | 50.95 ± 0.85 | 29.76 ± 0.81 | 28.92 ± 0.78 |

| MHC‐I | 246.50 ± 1.40 | 221.60 ± 4.56** | 191.90 ± 17.16 | 208.90 ± 14.61 |

| PD‐L1 | 10.46 ± 0.09 | 12.47 ± 0.13**** | 10.68 ± 1.18 | 14.64 ± 1.92** |

| Ki‐67 | 95.73 ± 0.15 | 88.04 ± 0.73*** | 68.32 ± 7.56 | 26.98 ± 13.33* |

Mdivi1 has been reported to protect the mitochondria from oxidative stress, 41 and therefore the observed T cell immunomodulation induced by M1/Mdivi1 could be due to its antioxidant property rather than fusion/fission‐specific effects. To address this, we performed a series of experiments using N‐acetylcysteine (NAC), an antioxidant that protects cardiac allografts against IRI. 42 First, to verify the antioxidant property M1/Mdivi1 might possess in our model, we subjected control MCECs, M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs, NAC‐pretreated MCECs, or DRP1KDs to CS‐IRI. Upon reperfusion, we stained the cells with MitoSOX Red to detect mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Our results revealed that M1/Mdivi1 exhibited an antioxidant effect similar to NAC, a property that was not associated with fission inhibition by DRP1 knock‐down (Figure S5A). Subsequently, we co‐cultured these cells with allogeneic T cells upon reperfusion to determine their immunogenicity. Levels of secreted IFNγ and granzyme‐B at the end of co‐cultures demonstrated that the antioxidant property and the anti‐inflammatory property were independent of each other, as NAC‐pretreated MCECs had similar immunogenicity to control MCECs, while DRP1KDs, which were susceptible to mitochondrial oxidative stress, displayed decreased immunogenicity to allogeneic T cells (Figure S5B).

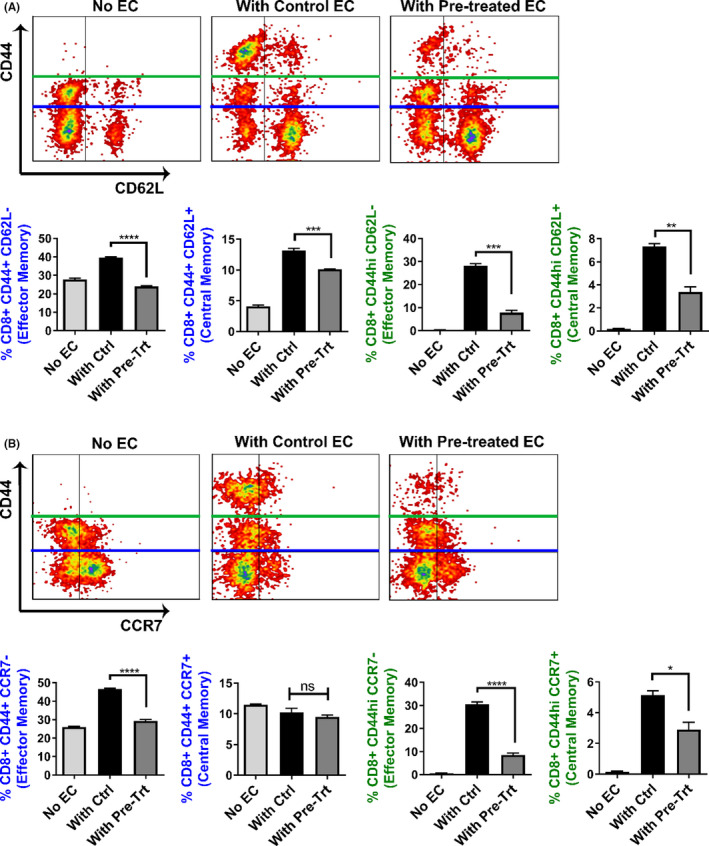

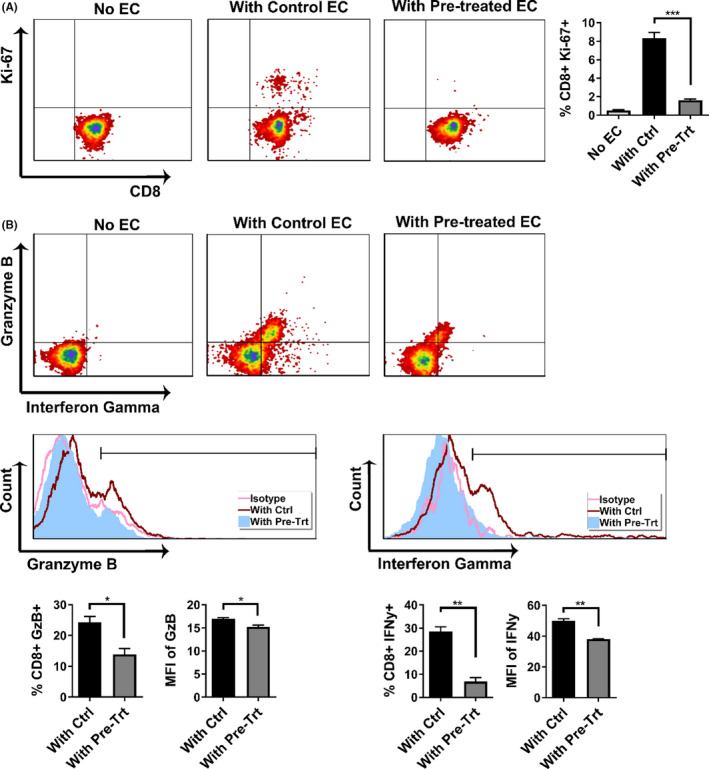

3.4. Pharmacologic modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission in ECs mitigates the alloimmune response of co‐cultured T cells

Since pre‐treating MCECs with M1/Mdivi1 prior to CS significantly reduced their immunogenicity to allogeneic CD8+ T cells and altered the expression of their surface markers and proliferative index, we next investigated whether changes in EC immunological phenotype could alter the T cell response. Using the CS‐IRI model with pre‐CS M1/Mdivi1 treatment, upon reperfusion we again co‐cultured pretreated MCECs or untreated controls with pre‐sensitized allogeneic CD8+ T cells. After 48 h of co‐culture, we performed flow cytometry on CD8+ T cells for markers of memory phenotype, proliferative index, and intracellular cytotoxic protein production. Flow analyses showed that total populations of effector memory (CD44+ CD62L− or CD44+ CCR7−) and central memory (CD44+ CD62L+) were significantly reduced in T cells co‐cultured with M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated MCECs compared to untreated controls (Figure 4, blue gating). Given that CD44 expression correlates to T cell activation and Tmems highly expressing CD44 (CD44hi) contribute significantly to alloimmune rejection, 43 , 44 we gated on the CD44hi populations, and found both effector memory (CD44hi CD62L− or CD44hi CCR7−) and central memory (CD44hi CD62L+ or CD44hi CCR7+) were significantly reduced in T cells co‐cultured with pretreated MCECs compared to untreated controls (Figure 4, green gating). Additionally, we noted that the proliferative index was lower in T cells co‐cultured with pretreated MCECs compared to untreated controls, as indicated by Ki‐67 expression (Figure 5A). Furthermore, fewer T cells producing granzyme‐B and IFNγ (represented by percentage of cells) as well as less granzyme‐B and IFNγ production (represented by MFI) were noted in pretreated MCEC co‐cultures compared to untreated controls (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 4.

Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission in ECs alters the memory phenotype of co‐cultured T cells. Blue gating: Flow cytometry analyses showing the percentages of both effector memory population, with phenotype CD44+ CD62L− (A) or CD44+ CCR7− (B), and central memory population, with phenotype CD44+ CD62L+ (B), are lower in CD8+ T cells co‐cultured with pre‐cold storage M1/Mdivi1‐treated MCECs versus untreated controls (n = 3). Green gating: Flow cytometry analyses with a focus on the CD44hi populations showing that both effector memory population, with phenotype CD44hi CD62L− (A) or CD44hi CCR7− (B), and central memory population, with phenotype CD44hi CD62L+ (A) or CD44hi CCR7+ (B), are lower in CD8+ T‐cells co‐cultured with pre‐cold storage M1/Mdivi1‐treated MCECs versus untreated controls (n = 3) (****p < .0001, ***p < .005, **p < .01, *p < .05. Differences between untreated control and M1/Mdivi1‐treated groups were analyzed using Student's t‐test)

FIGURE 5.

Pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission in ECs mitigates the alloimmune response of co‐cultured T cells. (A) Flow cytometry analyses showing the percentages of proliferative CD8+ T cells, marked by Ki‐67 expression, are lower in T cells co‐cultured with pre‐cold storage M1/Mdivi1‐treated MCECs versus untreated controls (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometry analyses showing that both percentages of CD8+ T cells expressing the two cytotoxic proteins granzyme‐B and interferon gamma, and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cytotoxic proteins are lower in T cells co‐cultured with pre‐cold storage M1/Mdivi1‐treated MCECs versus untreated controls (n = 3). (**p < .01, *p < .05. Differences between untreated controls and M1/Mdivi1‐treated groups were analyzed using Student's t‐test)

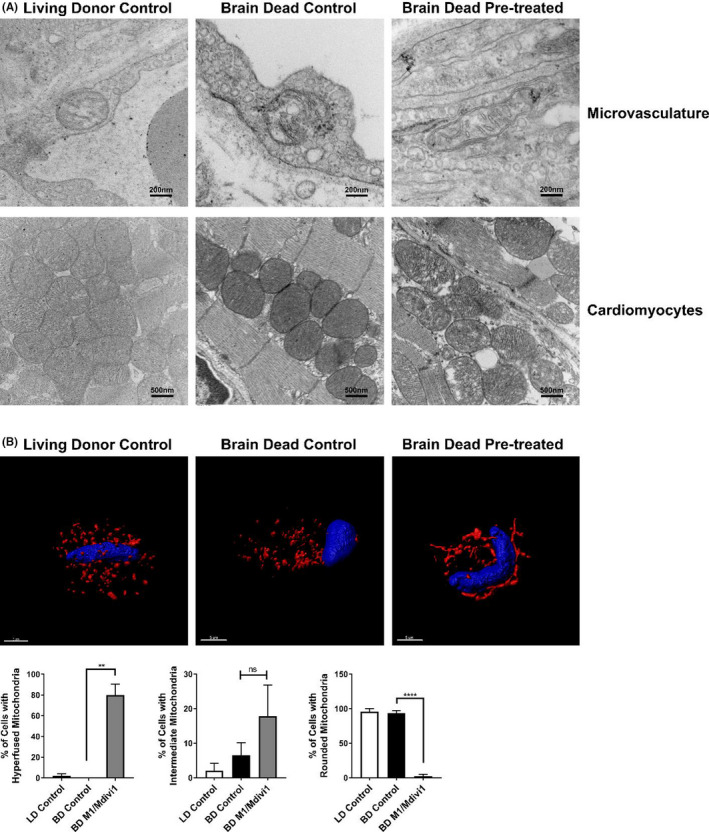

3.5. Donor pre‐treatment with M1/Mdivi1 exerts mitochondria‐elongating effects on cardiac ECs but not cardiomyocytes

Our in vitro results indicated that promoting fusion/inhibiting fission in ECs altered allogeneic T cell responses. Building on these novel observations, we utilized a novel murine brain‐dead donor cardiac transplant model. 4 Donor BD was induced, and upon confirmation of donor BD, a bolus of 2.4 mg/kg M1 and 1.2 mg/kg Mdivi1 or PBS control was infused via a carotid catheter. The donor was then ventilated further for 3 h. At the end of this brain‐death period, the donor heart was procured. No significant differences in blood pressure, body temperature, or heart rate where seen between the treatment or control groups. Electron microscopy on brain‐dead M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated donor hearts demonstrated elongated mitochondria, as compared to brain‐dead untreated controls or living donor controls, only in the ECs and not in the cardiomyocytes (Figure 6A). As further validation and comparison to our in vitro studies, we isolated ECs from donor hearts and performed confocal imaging. Three‐dimensional rendering demonstrated clear elongation of mitochondria in M1/Mdivi1 brain‐dead donor ECs compared to controls. Quantification of these images further demonstrated significant differences between the brain‐dead treated groups and the brain‐dead untreated controls (Figure 6B). The effects of mitochondria elongation by M1/Mdivi1 appeared to be confined to ECs, as no mitochondrial elongation was noted in cardiomyocytes. Since our in vitro data showed M1/Mdivi1 treatment was associated with reduced EC activation, we assessed whether the treatment impacted endothelial barrier functions using in vitro trans‐endothelial electrical resistance assays. We found the integrity of the endothelial monolayer pretreated with M1/Mdivi1 prior to CS was significantly improved at 18‐ and 24‐h post‐reperfusion compared to non‐treated CS and normal monolayer controls (Figure S6).

FIGURE 6.

Donor pre‐treatment with M1/Mdivi1 exerts mitochondria‐elongating effects on cardiac ECs but not cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy images showing mitochondria in ECs but not in cardiomyocytes are morphologically elongated at the end of donor pre‐treatment with M1/Mdivi1. (B) Representative 3D confocal images showing mitochondria in ECs isolated from M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated donor hearts are elongated, and quantification of mitochondrial morphology performed as in Figure 1A (n = 3 mice/group with 50 cells/group, ****p < .0001, **p < .01. Differences between BD control and BD M1/Mdivi1 groups were analyzed using Student's t‐test)

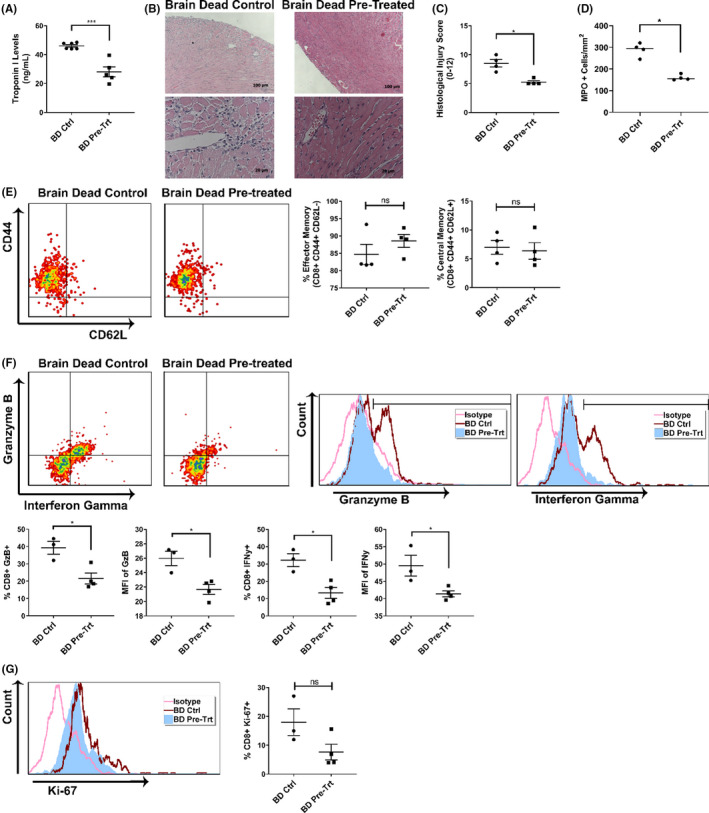

3.6. Donor pre‐treatment with mitochondrial fusion promoter/fission inhibitor protects cardiac allografts from injury and mitigates T cell alloimmune response

With our imaging studies supporting the efficacy of M1/Mdivi1 donor pre‐treatment in vivo, we next determined whether the mitochondrial therapy impacted posttransplant outcomes. Brain‐dead donor hearts from M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated and untreated donors were heterotopically transplanted into allogeneic recipients. Forty‐eight hours posttransplant, serum levels of cardiac troponin‐I, a marker for cardiac injury, were found to be significantly reduced in the recipients receiving brain‐dead M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated hearts compared to brain‐dead untreated controls (Figure 7A). Further, semi‐quantitative scoring demonstrated a significant reduction in histological evidence of injury in the brain‐dead M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated hearts compared to brain‐dead untreated controls (Figure 7B,C). IRI is characterized by innate immune cell infiltration, and therefore, we quantified myeloperoxidase immune cell infiltrates using immunohistochemistry. In keeping with our histological injury scores, M1/Mdivi1 donor pre‐treatment significantly reduced immune cell infiltration (Figure 7D).

FIGURE 7.

Donor pre‐treatment with mitochondrial fusion promoter/fission inhibitor protects cardiac allografts from injury and mitigates T cell alloimmune response. (A) Cardiac injury, reflected by serum cardiac troponin I levels at 48 h posttransplant, is significantly reduced in mice receiving M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts. (B) Histological staining and (C) quantification analysis showing significantly less cardiac injury and immune infiltration in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts versus untreated controls. (D) Brain‐dead donor delivery of M1/Mdivi1 significantly reduces innate immune cell infiltrates as demonstrated by myeloperoxidase immunohistochemistry in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts versus untreated controls. (E) Flow cytometry analyses showing no changes in effector memory (CD44+ CD62L−) and central memory (CD44+ CD62L+) compartments of CD8+ T cells in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts versus untreated controls. (F) CD8+ T cells infiltrating cardiac allografts have significantly lower granzyme‐B and interferon gamma production in M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts compared to those infiltrating untreated controls, reflected by both frequencies of T cells producing these cytotoxic proteins and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the proteins in T cells. (G) Flow cytometry analyses showing no changes in proliferative index (Ki‐67) in infiltrating CD8+ T cells (***p < .005, *p < .05. Differences between untreated controls and M1/Mdivi1‐treated groups were analyzed using Mann‐Whitney test for histological analysis and Student's t‐test for the remaining analyses)

Our in vitro data showed that M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment reduced allogeneic T cell activity, and therefore, we next examined T cell responses in vivo. Flow cytometry analyses on CD8+ T cells isolated from allografts at 48 h posttransplant revealed that, while there were no changes in effector memory (CD44+ CD62L−) and central memory (CD44+ CD62L+) frequencies in brain‐dead pretreated versus control groups (Figure 7E), there were significantly fewer T cells producing granzyme‐B and IFNγ as well as less granzyme‐B and IFNγ production in brain‐dead pretreated compared to untreated control groups (Figure 7F). We also examined proliferative index in the infiltrating T cells (represented by Ki‐67 expression), and surprisingly we could not detect any significant differences between groups (Figure 7G).

Furthermore, ECs were also isolated from the cardiac allografts at 48 h posttransplant, and flow cytometry analyses revealed no significant differences in surface expression of adhesion molecules, costimulatory ligands, MHC‐I, or coinhibitory ligands in ECs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of MFI of surface markers and proliferative index at 48 h posttransplant in ECs isolated from brain‐dead control or pretreated hearts (n = 4 mice/group)

| Molecule name | BD control | BD pretreated |

|---|---|---|

| VCAM‐1 | 104.80 ± 10.16 | 106.60 ± 15.61 |

| P‐selectin | 215.20 ± 170.10 | 65.79 ± 11.83 |

| CD80 | 230.50 ± 75.34 | 186.10 ± 43.43 |

| MHC‐I | 83.77 ± 6.81 | 85.71 ± 17.30 |

| PD‐L1 | 54.96 ± 9.40 | 62.18 ± 6.22 |

| Ki‐67 | 24.79 ± 6.39 | 22.44 ± 5.46 |

3.7. Donor pre‐treatment with mitochondrial fusion promoter/fission inhibitor significantly prolongs cardiac allograft survival

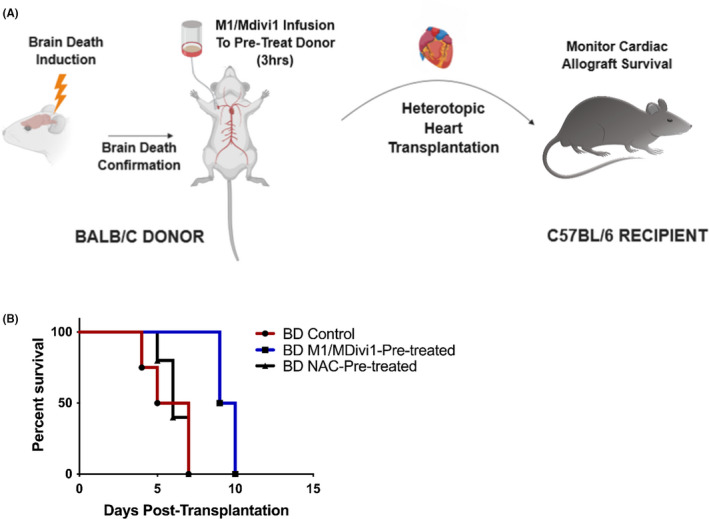

Finally, to assess the impact of mitochondrial therapy on allograft survival, allogeneic heterotopic transplants of Balb/c brain‐dead M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated hearts or brain‐dead control hearts into C57BL/6 recipients were performed (illustrated in Figure 8A). Brain death has been shown to significantly reduce allograft survival compared to that from living donors. 4 Here, M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment of brain‐dead donor hearts was associated with significant prolongation of median allograft survival (9.5 days) compared to untreated brain‐dead controls (6 days, p = .0091 by log‐rank test) (Figure 8B). To determine whether M1/Mdivi1’s protective effect is all mediated through an antioxidant pathway, we performed direct comparisons of M1/Mdivi1 versus NAC brain‐dead donor pre‐treatment. Consistent with our in vitro data (Figure S5), this protective effect was not seen with antioxidant therapy alone, as NAC pre‐treatment resulted in similar outcomes to untreated controls (Figure 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Donor pre‐treatment with mitochondrial fusion promoter/fission inhibitor significantly prolongs cardiac allograft survival. (A) Schematics of the brain‐dead murine transplant model. (B) Percent survival of transplanted cardiac allografts showing donor pre‐treatment with M1/Mdivi1 after brain death leads to significantly improved survival outcomes (n = 4, p = .0091 by Mantel‐Cox test), an effect that is not observed with pre‐treatment of the antioxidant, N‐acetylcysteine, alone

4. DISCUSSION

In cardiac transplantation, donor ECs play a pivotal role in allograft immunogenicity by interacting with recipient alloreactive Tmems. We have previously shown that modulating EC mitochondrial bioenergetics after reperfusion reduced their immunogenicity to allogeneic T cells. 35 This led us to reason that modulating other aspects of EC mitochondrial physiology, such as mitochondrial fusion/fission, could alter Tmems responses and could potentially be clinically translated. In this study, we modulated mitochondria prior to CS and investigated the impact of such donor pre‐treatment on immunological outcomes.

Since inhibiting mitochondrial fission in the heart is protective against focal IRI, 32 we knocked down DRP1 in ECs to skew mitochondrial dynamics toward fusion. In addition to less DRP1 protein levels and elongated mitochondrial morphology in DRP1KDs, our data indicate that DRP1KDs have higher mitochondrial fitness and mass. These characteristics are consistent with previous reports that promoting fusion is associated with increased oxidative phosphorylation efficiency and higher mitochondrial mass, thus supporting the validity of our knock‐down model. 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 Also, less supernatant cytotoxic proteins were detected in co‐cultures between DRP1KDs and allogeneic T cells compared to wildtype controls and allogeneic T cells, in both normothermic and CS‐IRI settings. These findings demonstrate that promoting fusion reduces EC immunogenicity to T cells.

The fusion promoter M1 and the fission inhibitor Mdivi1 have been shown to effectively skew mitochondrial dynamics toward fusion when utilized in combination. 31 In our studies, we employed them as tools to promote fusion/inhibit fission in ECs. We acknowledge a disadvantage of utilizing pharmacologic agents as mechanistic tools is the potential confounding off‐target effects. 41 However, our initial findings using the genetic knock‐down model suggest that reduced EC immunogenicity is mediated specifically by skewed fission‐to‐fusion.

When fusion is promoted/fission is inhibited by M1/Mdivi1 in ECs prior to pro‐inflammatory cytokine‐mediated activation or CS‐IRI insults, their immunogenicity is reduced, evidenced by less cytotoxic proteins in co‐cultures between M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated ECs and allogeneic T cells, a marked reduction in VCAM‐1, an important adhesion molecule for immune synapse formation and T cell adhesion, 49 and an increase in PD‐L1, a co‐inhibitory ligand inhibiting T cell function. 40 Of note, when PD‐L1 is blocked, the immuno‐protective effect of M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment is abrogated at least partially, suggesting this observed effect is dependent on PD‐L1 expression. PD‐1, the receptor of PD‐L1, has been shown to be highly expressed in certain types of functionally active Tmems, 50 and thus, M1/Mdivi1‐mediated PD‐L1 expression will offer significant immuno‐protection against these T cell populations.

In the clinically relevant CS‐IRI model, we focused on 6 and 24 h post‐reperfusion because EC mitochondrial changes and immunological phenotypes are the most strongly associated at these two timepoints. 35 T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within the first 24 h post‐reperfusion and start releasing cytotoxic proteins to mediate allograft rejection from 24–72 h post‐reperfusion. 10 , 51 In this context, a reduction of MHC‐I at 6 h post‐reperfusion, of VCAM‐1, Ki‐67 (a marker for cellular proliferative index) at 24 h post‐reperfusion, and an increase of PD‐L1 at 24 h post‐reperfusion, as shown by our data, can alter the T cell response significantly. Indeed, in vitro, at 48 h post‐reperfusion, CD8+ T cells co‐cultured with pretreated ECs display a significant reduction in both memory compartments, proliferative index, and intracellular production of cytotoxic proteins. In vivo, at 48 h posttransplant, CD8+ T cells isolated from M1/Mdivi1‐pretreated allografts display a significant reduction in intracellular cytotoxic protein production. These T cells, however, do not have any changes in memory phenotype and proliferative index. The discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo T cell responses can be attributed to the complexity of the in vivo microenvironment, such as the presence of complex cytokine milieu composition. 52

To assess transplant outcome, we used a murine cardiac transplant model incorporating donor BD, a clinically relevant phenomenon predisposing allografts to pro‐inflammatory states. 4 , 53 We demonstrated that promoting mitochondrial fusion/inhibiting fission in donor ECs reduces cardiac injury and significantly delays allograft rejection. Of note, the effects of M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment on cardiac allografts appear to be EC‐specific, as changes in mitochondrial morphology only occurred in ECs but not in cardiomyocytes. Given our adhesion molecule expression data, we speculated that M1/Mdivi1 abrogates EC activation, which promotes improved EC barrier functions, demonstrated with our trans‐endothelial resistance studies, and thus may limit exposure of cardiomyocytes to circulating M1/Mdivi1. Alternatively, given the high density of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes, a higher dose of M1/Mdivi1 may be required to mediate an effect on cardiomyocytes. Finally, the extracellular matrix separating ECs and cardiomyocytes may inhibit the diffusion of M1/Mdivi1 to the cardiomyocytes. Nevertheless, this selectivity may be a significant therapeutic benefit, and may well obviate any potentially confounding side‐effects of modulating cardiomyocyte metabolic functions.

How exactly modulating mitochondrial fusion/fission alters EC immunological phenotype remains unclear. Reports by other groups have indicated mitochondrial fusion can be induced through mTOR‐NFkB‐OPA1 signaling. 54 Since the NFkB pathway controls VCAM‐1 expression, 55 promoting fusion/inhibiting fission possibly induces a feedback inhibition that reduces NFkB activation, leading to reduced VCAM‐1 expression. Additionally, inhibiting mTOR in human ECs has been shown to increase PD‐L1, 56 and thus the same feedback inhibition potentially leads to PD‐L1 upregulation. Furthermore, in other cardiac IRI models, inhibiting mitochondrial fission in microvascular ECs leads to inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening by preventing voltage‐dependent anion channel‐1 (VDAC‐1) oligomerization. 34 As we have shown in our previous studies that post‐reperfusion mPTP inhibition reduces EC immunogenicity, 35 M1/Mdivi1 pre‐treatment prior to CS might alter VDAC‐1 oligomerization in ECs, leading to longer mPTP closure post‐reperfusion in our model. Future studies will be directed toward studying the exact mechanisms underlying the regulation of mitochondrial fusion/fission on EC immunological phenotype.

As therapeutics could be targeted to ECs using nanoparticles containing Arginine‐Glycine‐Aspartate sequence, demonstrated by previous in vitro and in vivo studies, 57 , 58 the same delivery modality could be utilized to enhance M1/Mdivi1 uptake in ECs and would be another potential future investigation.

In summary, we demonstrate through clinically relevant in vitro CS‐IRI models that promoting mitochondrial fusion/inhibiting fission in donor ECs reduces their immunogenicity and suppresses Tmems responses. We also describe a novel approach that improves transplant outcomes in vivo through modulating mitochondrial dynamics of donor cardiac allografts. These findings serve as a foundation for potential clinical translation in humans to potentially facilitate induction of transplant tolerance.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. DTT, CA, and SNN are inventors of a filed patent on M1/Mdivi1 utilization in transplant models.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Nancy Smythe for her expertise on transmission electron microscopy and Diana Fulmer for her insights into the IMARIS software. Additionally, the murine transplant schematics was created with BioRender.com.

Tran DT, Tu Z, Alawieh A, et al. Modulating donor mitochondrial fusion/fission delivers immunoprotective effects in cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant.2022;22:386–401. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16882

Funding information

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (NIAID R01 AI142079 01A1 to Dr. Satish Nadig, 1UO1AI132894‐01 to Dr. Carl Atkinson, NHLBI Predoctoral Fellowship Training Grant T32 HL007260 to Danh Tran, NIGMS MSTP Predoctoral Fellowship Training Grant T32 GM008716 to Danh Tran), funding from the Patterson Barclay Memorial Foundation, and funding grant USPHS S10 OD018113 “Confocal/Multiphoton Microscope Upgrade” to MUSC Imaging Core.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Toyoda Y, Guy TS, Kashem A. Present status and future perspectives of heart transplantation. Circ J. 2013;77(5):1097‐1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eisen HJ. Heart transplantation in adults: Diagnosis of acute allograft rejection. In: Dardas Todd F, ed. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Libby P, Pober JS. Chronic rejection. Immunity. 2001;14(4):387‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atkinson C, Floerchinger B, Qiao F, et al. Donor brain death exacerbates complement‐dependent ischemia/reperfusion injury in transplanted hearts. Circulation. 2013;127(12):1290‐1299. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.112.000784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilhelm MJ, Pratschke J, Laskowski IA, Paz DM, Tilney NL. Brain death and its impact on the donor heart‐lessons from animal models. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2000;19(5):414‐418. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00073-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilhelm MJ, Pratschke J, Beato F, et al. Activation of the heart by donor brain death accelerates acute rejection after transplantation. Circulation. 2000;102(19):2426‐2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Woude FJ, Schnuelle P, Yard BA. Preconditioning strategies to limit graft immunogenicity and cold ischemic organ injury. J Investig Med. 2004;52(5):323‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abrahimi P, Liu R, Pober JS. Blood vessels in allotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(7):1748‐1754. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Su CA, Iida S, Abe T, Fairchild RL. Endogenous memory CD8 T cells directly mediate cardiac allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(3):568‐579. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schenk AD, Nozaki T, Rabant M, Valujskikh A, Fairchild RL. Donor‐reactive CD8 memory T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within 24‐h posttransplant in naive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(8):1652‐1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02302.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Epperson DE, Pober JS. Antigen‐presenting function of human endothelial cells. Direct activation of resting CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 1994;153(12):5402‐5412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreisel D, Krasinskas AM, Krupnick AS, et al. Vascular endothelium does not activate CD4+ direct allorecognition in graft rejection. J Immunol. 2004;173(5):3027‐3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Balsara KR, et al. Mouse vascular endothelium activates CD8+ T lymphocytes in a B7‐dependent fashion. J Immunol. 2002;169(11):6154‐6161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Gelman AE, et al. Non‐hematopoietic allograft cells directly activate CD8+ T cells and trigger acute rejection: an alternative mechanism of allorecognition. Nat Med. 2002;8(3):233‐239. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krupnick AS, Kreisel D, Popma SH, et al. Mechanism of T cell‐mediated endothelial apoptosis. Transplantation. 2002;74(6):871‐876. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pearl JP, Parris J, Hale DA, et al. Immunocompetent T‐cells with a memory‐like phenotype are the dominant cell type following antibody‐mediated T‐cell depletion. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(3):465‐474. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trzonkowski P, Zilvetti M, Friend P, Wood KJ. Recipient memory‐like lymphocytes remain unresponsive to graft antigens after CAMPATH‐1H induction with reduced maintenance immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2006;82(10):1342‐1351. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000239268.64408.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ayasoufi K, Yu H, Fan R, Wang X, Williams J, Valujskikh A. Pretransplant antithymocyte globulin has increased efficacy in controlling donor‐reactive memory T cells in mice. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(3):589‐599. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duboc D, Abastado P, Muffat‐Joly M, et al. Evidence of mitochondrial impairment during cardiac allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1990;50(5):751‐755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fernandez D, Bonilla E, Mirza N, Niland B, Perl A. Rapamycin reduces disease activity and normalizes T cell activation‐induced calcium fluxing in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2983‐2988. doi: 10.1002/art.22085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin L, Xu HE, Bishawi M, et al. Circulating mitochondria in organ donors promote allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(7):1917‐1929. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pollara J, Edwards RW, Lin L, Bendersky VA, Brennan TV. Circulating mitochondria in deceased organ donors are associated with immune activation and early allograft dysfunction. JCI Insight. 2018;3(15): doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roedder S, Sigdel T, Hsieh S‐C, et al. Expression of mitochondrial‐encoded genes in blood differentiate acute renal allograft rejection. Front Med. 2017;4:185. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saba H, Munusamy S, Macmillan‐Crow LA. Cold preservation mediated renal injury: involvement of mitochondrial oxidative stress. Ren Fail. 2008;30(2):125‐133. doi: 10.1080/08860220701813327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Serviddio G, Bellanti F, Sastre J, Vendemiale G, Altomare E. Targeting mitochondria: a new promising approach for the treatment of liver diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(22):2325‐2337. doi: 10.2174/092986710791698530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zepeda‐Orozco D, Kong M, Scheuermann RH. Molecular profile of mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney transplant biopsies is associated with poor allograft outcome. Transplantation Proc. 2015;47(6):1675‐1682. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.04.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:79‐99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(12):872‐884. doi: 10.1038/nrm3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parajuli N, Shrum S, Tobacyk J, Harb A, Arthur JM, MacMillan‐Crow LA. Renal cold storage followed by transplantation impairs expression of key mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ryu SW, Han EC, Yoon J, Choi C. The mitochondrial fusion‐related proteins Mfn2 and OPA1 are transcriptionally induced during differentiation of bone marrow progenitors to immature dendritic cells. Mol Cells. 2015;38(1):89‐94. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buck M, O’Sullivan D, Klein Geltink R, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics controls T cell fate through metabolic programming. Cell. 2016;166(1):63‐76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2010;121(18):2012‐2022. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.109.906610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimizu Y, Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, et al. DJ‐1 protects the heart against ischemia‐reperfusion injury by regulating mitochondrial fission. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:56‐66. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou H, Hu S, Jin Q, et al. Mff‐dependent mitochondrial fission contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac microvasculature ischemia/reperfusion injury via induction of mROS‐mediated cardiolipin oxidation and HK2/VDAC1 disassociation‐involved mPTP opening. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3). doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.005328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tran DT, Esckilsen S, Mulligan J, Mehrotra S, Atkinson C, Nadig SN. Impact of mitochondrial permeability on endothelial cell immunogenicity in transplantation. Transplantation. 2018;102(6):935‐944. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang B, Alysandratos K‐D, Angelidou A, et al. Human mast cell degranulation and preformed TNF secretion require mitochondrial translocation to exocytosis sites: relevance to atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(6):1522‐1531.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Doherty E, Perl A. Measurement of mitochondrial mass by flow cytometry during oxidative stress. React Oxyg Species. 2017;4(10):275‐283. doi: 10.20455/ros.2017.839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Q, Chen Y, Fairchild RL, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. Lymphoid sequestration of alloreactive memory CD4 T cells promotes cardiac allograft survival. J Immunol. 2006;176(2):770–777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Laskowski I, Pratschke J, Wilhelm MJ, Gasser M, Tilney NL. Molecular and cellular events associated with ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ann Transpl. 2000;5(4):29‐35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Malley G, Treacy O, Lynch K, et al. Stromal cell PD‐L1 inhibits CD8(+) T‐cell antitumor immune responses and promotes colon cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(11):1426‐1441. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.cir-17-0443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bordt EA, Clerc P, Roelofs BA, et al. The putative Drp1 inhibitor mdivi‐1 is a reversible mitochondrial complex I inhibitor that modulates reactive oxygen species. Dev Cell. 2017;40(6):583‐594.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mei J, Zhu J, Ding F, Bao C, Wu S. N‐acetylcysteine improves early cardiac isograft function in a rat heterotopic transplantation model. Transpl Proc. 2009;41(9):3632‐3636. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schumann J, Stanko K, Schliesser U, Appelt C, Sawitzki B. Differences in CD44 surface expression levels and function discriminates IL‐17 and IFN‐gamma producing helper T cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang H, Zhang Z, Tian W, et al. Memory T cells mediate cardiac allograft vasculopathy and are inactivated by anti‐OX40L monoclonal antibody. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2014;28(2):115‐122. doi: 10.1007/s10557-013-6502-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mishra P, Carelli V, Manfredi G, Chan DC. Proteolytic cleavage of Opa1 stimulates mitochondrial inner membrane fusion and couples fusion to oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2014;19(4):630‐641. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yao CH, Wang R, Wang Y, Kung CP, Weber JD, Patti GJ. Mitochondrial fusion supports increased oxidative phosphorylation during cell proliferation. eLife. 2019;8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu LH, Chang HC, Ting PC, Wang DL. Laminar shear stress promotes mitochondrial homeostasis in endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(6):5058‐5069. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Teijeira A, Labiano S, Garasa S, et al. Mitochondrial morphological and functional reprogramming following CD137 (4–1BB) costimulation. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(7):798‐811. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.cir-17-0767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chakraborty S, Hu SY, Wu SH, Karmenyan A, Chiou A. The interaction affinity between vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 (VCAM‐1) and very late antigen‐4 (VLA‐4) analyzed by quantitative FRET. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blanc C, Hans S, Tran T, et al. Targeting resident memory T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1722. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. El‐Sawy T, Miura M, Fairchild R. Early T cell response to allografts occurring prior to alloantigen priming up‐regulates innate‐mediated inflammation and graft necrosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(1):147‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen J, Liu C, Liu B, Kong D, Wen L, Gong W. Donor IL‐6 deficiency evidently reduces memory T cell responses in sensitized transplant recipients. Transpl Immunol. 2018;51:66‐72. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takada M, Nadeau KC, Hancock WW, et al. Effects of explosive brain death on cytokine activation of peripheral organs in the rat. Transplantation. 1998;65(12):1533‐1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Parra V, Verdejo HE, Iglewski M, et al. Insulin stimulates mitochondrial fusion and function in cardiomyocytes via the Akt‐mTOR‐NFkappaB‐Opa‐1 signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2014;63(1):75‐88. doi: 10.2337/db13-0340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Milstone DS, Ilyama M, Chen M, et al. Differential role of an NF‐kappaB transcriptional response element in endothelial versus intimal cell VCAM‐1 expression. Circ Res. 2015;117(2):166‐177. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.117.306666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang C, Yi T, Qin L, et al. Rapamycin‐treated human endothelial cells preferentially activate allogeneic regulatory T cells. J Clin Investig. 2013;123(4):1677‐1693. doi: 10.1172/jci66204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nadig SN, Dixit SK, Levey N, et al. Immunosuppressive nano‐therapeutic micelles downregulate endothelial cell inflammation and immunogenicity. RSC Adv. 2015;5(54):43552‐43562. doi: 10.1039/c5ra04057d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhu P, Atkinson C, Dixit S, et al. Organ preservation with targeted rapamycin nanoparticles: a pre‐treatment strategy preventing chronic rejection in vivo. RSC Adv. 2018;8(46):25909‐25919. doi: 10.1039/c8ra01555d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.