Abstract

Introduction:

The diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) on fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimens can be challenging because of morphologic overlap with other pancreatic neoplasms, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNET). SRY-related high-mobility group box 11 (SOX11) is a recently described sensitive and specific marker for SPN diagnosis. However, SOX11 immunocytochemistry (ICC) on cytologic smears has not been reported. We evaluated the utility of SOX11 for diagnosis of SPN on cytologic preparations.

Methods:

SOX11 ICC was performed on Papanicolaou-stained smears and/or corresponding CBs, on SPN and PanNET FNA cases identified between 2005–2020. Findings were compared with that of beta-catenin ICC, which is frequently used as a diagnostic marker for SPN.

Results:

This study included 7 SPN and 10 PanNET cases. Six smears and 6 CB from SPN cases and 8 smears and 10 CB from PanNET cases were available for immunostaining. Nuclear staining for SOX11 was seen in 6 of 6 (100%) SPN smears and 5 of 6 (83%) SPN CBs, with equivocal staining in 1 CB. In contrast, 7 of 8 (88%) PanNET smears and 9 of 10 (90%) PanNET CBs were negative for SOX11, with equivocal staining seen in 1 case. Beta-catenin ICC showed nuclear staining in 6 of 7 (86%) SPN cases and no staining in all 10 (100%) PanNET cases.

Conclusions:

SOX11 detected by ICC can serve as a useful diagnostic marker for SPN, in addition to beta catenin, and can be performed on cytological smears in cases without a CB preparation.

Keywords: solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, pancreas, immunocytochemistry, cytology, smears

Graphical Abstract

SOX11 is a sensitive and specific marker for the diagnosis of SPN on cytological FNA samples and can be performed on both direct smears and cell block preparations. This is especially useful in specimens with limited amounts of tissue, in which the morphology is not definitive, and the cell block is inadequate for an extensive IHC work-up.

Introduction

Initially characterized by Franz et al,1 solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas is a relatively rare entity that comprises 2% to 3% of all pancreatic neoplasms. SPN of the pancreas have characteristic cytomorphologic features that include polygonal, bland tumor cells with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, often with variable-sized clear perinuclear vacuoles or cytoplasmic eosinophilic hyaline globules, admixed with delicate vessels surrounded by hyalinized or myxoid stroma, giving the tumor a pseudopapillary appearance. 2, 3 SPN often occurs in young women and typically has low malignant potential and is associated with a good prognosis.2, 3 Local surgical excision of SPN is usually curative; metastases are reported in 5% to 15% of cases.4, 5

EUS FNA is a critical step in diagnosing SPN and guiding management of the disease and may obviate the need for extensive surgery and chemotherapy.6, 7 Despite the described characteristic morphologic features, the diagnosis of SPN of the pancreas can sometimes be challenging, particularly on cytology specimens, in which the amount of tumor may be limited.6, 7 For instance, the differential diagnosis of SPN on cytology specimens often include pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNET) because of overlap in morphologic features. Both tumors can display singly dispersed and loosely cohesive clusters of small uniform cells with fine chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and numerous small blood vessels.8 Differentiation of SPN from PanNET is especially important as the treatment of PanNET is vastly different from that of SPN and usually involves a selection or combination of surgery, hormone therapy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.2,3,9 Immunocytochemistry (ICC) can be useful in such difficult cases for a definitive diagnosis.

Nuclear expression of beta-catenin by ICC has been widely used for the diagnosis of SPN. However, other tumors in the pancreas, such as PanNET and acinar cell carcinomas, can occasionally exhibit nuclear expression of beta-catenin, which reduces the specificity of the marker.3, 7, 10 Furthermore, in some SPN cases, background cytoplasmic/membranous staining by beta-catenin may prevent the pathologist from performing an accurate assessment of the expression of the marker in tumor cells.10 In addition, staining for neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin is occasionally observed in SPN tumors, causing further issues in differentiating between SPN and PanNET.8

Recently, SRY-related high-mobility group box 11 (SOX11) mRNA was found to be upregulated and increased in SPN compared to other pancreatic tumors and normal tissue.11 Furthermore, recent immunohistochemical studies for SOX11 have reported it to be a highly sensitive and specific marker for SPN.12, 13 These studies evaluating SOX11 in SPN were performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) surgical pathology and cytology cell block specimens. However, EUS-FNA specimens frequently have limited yield, with neoplastic cells present only on the direct smears, and not within the FFPE cell block preparation. While using SOX11 ICC for diagnosing SPN on cell block preparation appears to be effective, the feasibility and utility of SOX11 immunostaining on cytology materials from EUS-FNA smears, have not been reported. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the utility of SOX11 for the diagnosis of SPN on cytologic direct smears and FFPE cell blocks.

Methods

Following approval by the institutional review board, a retrospective search of our institutional pathology database was performed to identify EUS-FNA cases at our institution during 2005–2020 where SPN was included in the initial differential diagnosis. The cytology and subsequent surgical pathology specimens (when available) were reviewed, including ICC and immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains that had been performed as part of the clinical work-up.

For this study, SOX11 ICC was performed on alcohol-fixed Papanicolaou-stained direct smears and/or the corresponding cell blocks, as available. Cell blocks were prepared by centrifuging the aspirate rinse at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes and mixing the centrifugate with equal amounts of 95% ethanol and 10% formalin, followed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for another 10 minutes. The cell button formed was wrapped in a filter paper, placed into a tissue cassette, and fixed in 10% formalin for tissue processing. Following formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, tissue sections were cut at 4–5 micron thick sections onto slides. All the cases in this study were collected between 2007 to 2020.

We performed ICC on smears that were on positively charged and/or non-frosted glass slides. If tumor material was present only on a fully frosted glass slide, we excluded the case from SOX11 ICC, as these slides tend to show high background staining and are not optimal for immunostaining. In cases where there were limited numbers of tumor cells on the smear slides, the cells were marked by etching with a diamond-tip pen on the back of the cytology smear slides prior to immunostaining, to enable identification of the neoplastic cells after SOX11 ICC. Immunochemistry studies was performed with anti-Sox11 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:200, Clone MRQ-58, Cell Marque) on a Leica Bond III Autostainer (Lecia Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). The immunostained smears and cell block sections were evaluated independently by all the pathologists involved in this study, and results were correlated with the cytologic diagnosis, the final histologic diagnosis, and any available immunostains that were performed as part of the clinical work-up of the cases. Positive staining for SOX11 on cell block and smear was defined as diffuse and strong nuclear staining in tumor cells, while negative SOX11 was interpreted when there was no nuclear staining at all. Cases where the SOX11 staining was weak and focal were considered as equivocal staining.

Results

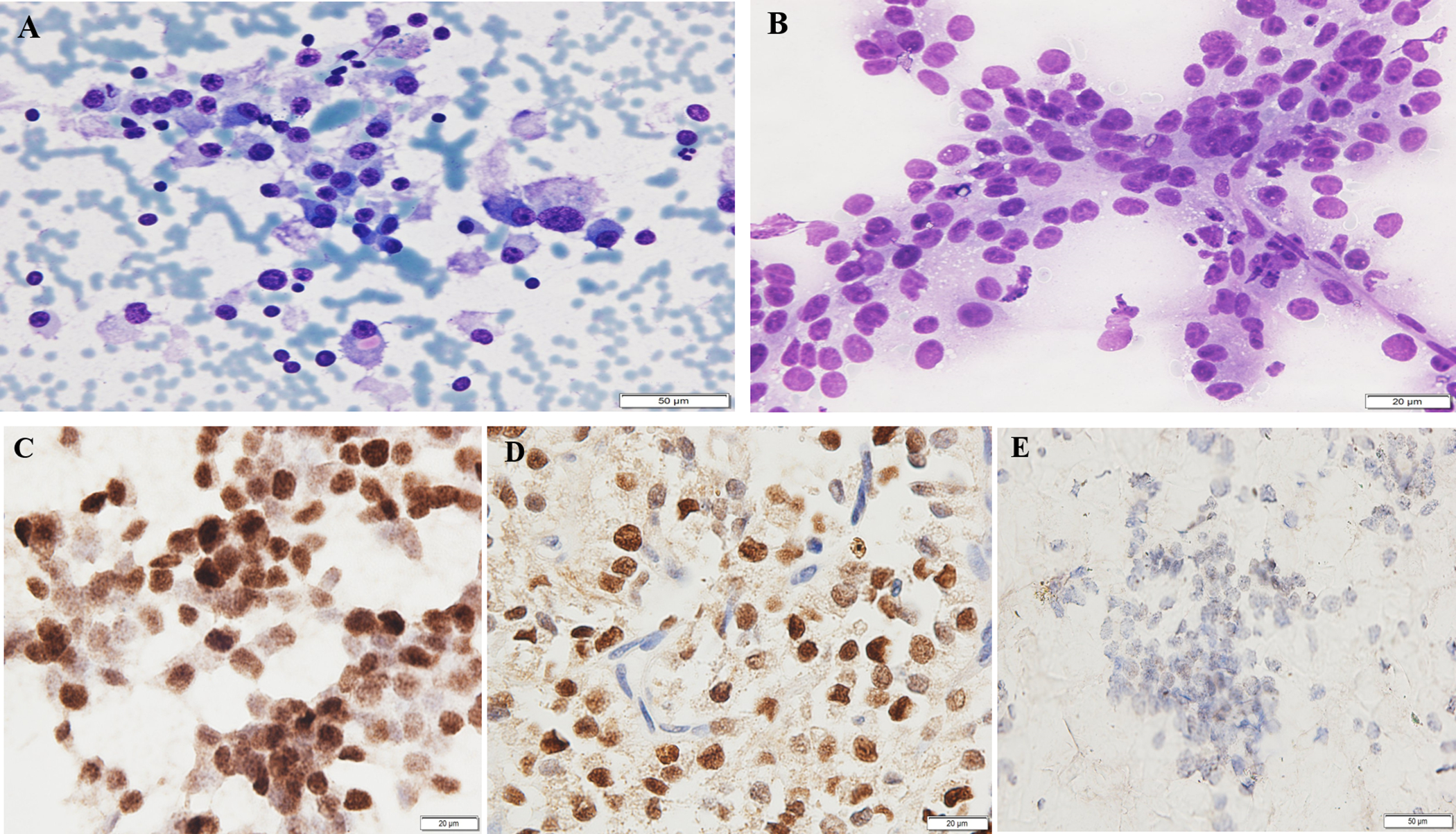

Seven cases of SPN and 10 cases of PanNET were identified for this study. All cases had rapid on-site evaluation with a preliminary differential diagnosis that included SPN and PanNET. The aspirates of the cases had moderate to high cellularity with cells arranged in loose clusters or singly dispersed, with a plasmacytoid appearance and absence of prominent nucleoli (Figure 1A and 1B). ICC was performed on cell block sections as part of the clinical work-up at the time of the initial diagnosis with a panel of immunostains, including beta-catenin (N=16), synaptophysin (N=15), and chromogranin (N=13). None of the cases had ICC performed on direct smears at the time of initial diagnosis. Sixteen of the 17 cases had surgical follow-up, and the final histologic diagnosis was concordant with the cytologic diagnosis in all 16 cases (Table 1). One case diagnosed as SPN by FNA did not have surgical follow-up.

Figure 1:

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) showing (A) Papanicolaou stained smears with moderate cellularity and singly dispersed bland cells with moderate amount of cytoplasm and cytoplasmic eosinophilic hyaline globules (200X); (B) Diff-Quik stained smears with delicate pseuodopapillary fronds containing bland and uniform neoplastic cells (400X); (C) SOX11 immunostain on alcohol-fixed Papanicolaou-stained direct smear demonstrating nuclear positivity (400X); (D) SOX11 immunostain of the corresponding cell block highlighting nuclear staining in the tumor cells (400X); (E) Equivocal staining of SOX11 on a cell block preparation with patchy weak staining in tumor nuclei (case 5) (200X).

Table 1.

Results of the immunocytochemistry performed on the study cases

| Case | Final Diagnosisa | SOX11 on Smear | SOX11 on Cell Block | Beta-Catenin | Synapto-physin | Chromo-granin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SPN | + | + | + | − | ND |

| 2 | SPN | + | + | + | − | − |

| 3 | SPN | + | + | + | ND | ND |

| 4 | SPN | + | NAb | ND | − | − |

| 5 | SPN | NAb | Equivocal | + | ND | ND |

| 6 | SPN | + | + | + | − | − |

| 7 | SPN | + | + | − | − | ND |

| 8 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 9 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 10 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 11 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 12 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 13 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 14 | PanNET | − | − | − | + | + |

| 15 | PanNET | NAb | − | − | + | + |

| 16 | PanNET | NAb | − | − | + | + |

| 17 | PanNET | Equivocal | Equivocal | − | + | + |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; ND, not done; PanNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; SPN, solid pseudopapillary neoplasm

Final cytologic and histologic diagnosis for all cases were concordant based on the surgical follow-up; case 7 did not have surgical follow-up.

Not available because smear or cell block section not available for immunostaining.

SPN cases

SOX11 ICC was performed on direct smears of 6 SPN cases; 1 SPN case did not have a smear available for ICC (Table 1). All 6 smears showed strong nuclear staining in tumor cells (Figure 1C). Six SPN cases had cell blocks available for SOX11 immunostaining. Five cases showed strong nuclear staining (Figure 1D); 1 case showed equivocal staining with patchy weak staining in the tumor nuclei (Figure 1E). There was no background staining in inflammatory or normal pancreatic cells in either the smears or cell block preparations.

Six SPN cases had beta-catenin ICC performed on the cell block sections as part of the clinical work-up that were available for our review. Five cases showed nuclear expression in the tumor cells, while 1 case was negative for beta-catenin. Five of seven cases, including the one negative for beta-catenin, had additional immunostaining of either synaptophysin and/or chromogranin, and all were negative for these markers (Table 1).

PanNET cases

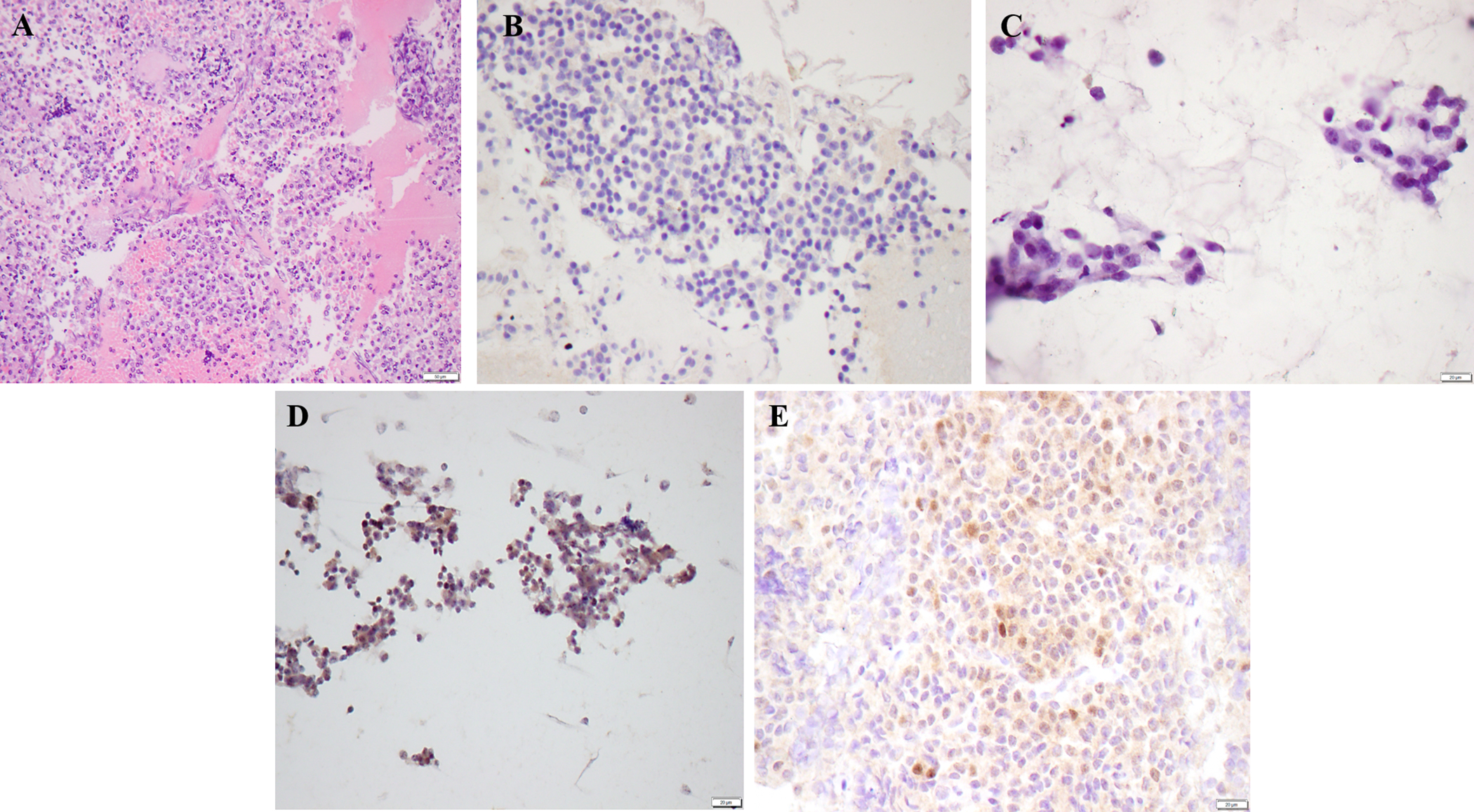

SOX11 ICC was performed on direct smears of 8 PanNET cases; 2 cases did not have an available smear for ICC (Table 1). Seven cases were negative for SOX11, and 1 showed equivocal staining. SOX11 ICC was performed on cell block sections in all 10 cases. Nine cases were negative for SOX11 (Figure 2), while 1 CB showed equivocal staining. Interestingly, the latter case had equivocal staining on both the cell block and the smear (Figure 2D and E).

Figure 2.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor showing (A) Hematoxylin & eosin stained section of the cell block preparation (100X); (B) Negative SOX11 ICC on cell block preparation (200X); (C) Negative SOX11 ICC on Papanicolaou-stained direct smear (400X); (D) Equivocal SOX11 immunostaining on Papanicolaou-stained direct smear showing predominantly non-specific cytoplasmic staining with focal staining in some tumor nuclei (case 17) (200X); (E) Equivocal SOX11 immunostaining on cell block preparation showing patchy weak staining in tumor nuclei (case 17) (400X).

All 10 PanNET cases had beta-catenin, synaptophysin, and chromogranin ICC performed on the cell block sections as part of the clinical work-up. All cases were negative for beta-catenin, while positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin, confirming the diagnosis of PanNET (Table 1).

Discussion

Pancreatic SPN can be diagnostically challenging on cytology, especially on limited EUS-FNA specimens.3 Fortunately, ICC can be performed on cytological tissue to aid in the diagnosis of SPN. Beta-catenin is frequently used as a diagnostic marker, and more recently, SOX11 has been described as a sensitive and specific marker for SPN. However, its feasibility and utility on cytology smears from EUS-FNA have not been reported. Our findings indicate that SOX11 ICC can be useful on both cytologic smears and cell block preparations for SPN diagnosis. In our study, all six SPN smears and 5 of 6 SPN cell block preparations had strong diffuse nuclear staining for SOX11. In addition, normal pancreatic cells and background inflammatory cells in the SPN cases were completely negative for SOX11. This is in contrast to beta-catenin, which has been reported to demonstrate background staining in normal pancreatic tissue.3, 7

One of the most common differential diagnosis for SPN in the pancreas is PanNET due to the cytomorphologic overlap. Almost all PanNET cases in our cohort were negative for SOX11 with 7 of 8 smears and 9 of 10 cell block sections tested. Interestingly, one case demonstrated equivocal weak and focal staining in both the smear and the cell block preparation. The reason for this staining pattern is unclear. However, this case stained positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin, while negative for beta-catenin and was confirmed as PanNET on a subsequent surgical diagnosis.

Majority of the SPN cases showed strong and diffuse nuclear staining for SOX11 whereas the PanNET cases were completely negative. Rare cases (SPN, n=1; PanNET, n=1) had weak patchy staining that was considered equivocal. Both these cases had additional immunostains (i.e. beta-catenin, synaptophysin, and chromogranin) that helped reach a definitive diagnosis (Table 1). Therefore, in cases with equivocal staining, additional immunostains can be helpful. Immunostains for several markers, including E-cadherin, CD99, and CD10, have been proposed and utilized to help differentiate SPN from other pancreatic tumors,2, 3 but none of these markers are specific for SPN, i.e., they can be positive in other pancreatic tumors.12, 15, 16 Further, most of the immunostains that have been tested are not optimal for use on smears because they either stain the background cells or have cytoplasmic/membranous staining that can be difficult to interpret. Beta-catenin, which is frequently used as a diagnostic IHC marker for SPN, is positive in only 90% of cases of SPN of the pancreas and can have variable specificity, with staining seen in approximately 3% of PanNET, up to 10% of acinar cell carcinomas, and 100% of pancreatoblastomas of the pancreas.2, 3, 16, 17 In our cohort, beta-catenin was positive in 83% (5 of 6) SPN cases and negative in 100% (10 of 10) PanNET cases.

Our study is limited by a relatively small sample size due to the rarity of SPN diagnosis and limited available tissue for ICC, precluding statistical analyses. Our sample search spanned 16 years of our institutional pathology database and identified only 7 cases with an EUS-FNA sample with a diagnosis of SPN. Cell block preparations were not available on all cases underscoring the importance of evaluating diagnostic ICC on cytological smear preparations. Further, our study demonstrated one SPN case that was negative for beta-catenin but showed strong SOX11 positivity on both the smear and cell block preparation. Therefore, in limited FNA samples where SPN is being considered, SOX11 ICC can be used as a valid diagnostic marker, used in isolation or in a panel.

In conclusion, our study shows that SOX11 is a useful marker for the diagnosis of SPN on cytologic EUS-FNA samples and can be performed on both direct smears and cell block preparations. This is especially useful in specimens with limited amounts of tissue, in which the morphology is not definitive, and the cell block is inadequate for an extensive IHC work-up. Used in isolation or in conjunction with other markers such as beta-catenin, SOX11 is an important addition to the cytopathologist’s ICC armamentarium.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Stephanie Deming, Scientific Editor, Research Medical Library, for editing this article.

Funding:

Supported by the National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA016672, which supports the MD Anderson Cancer Center Clinical Trials Office.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None

Data availability statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Chakhachiro ZI, Zaatari G. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm: a pancreatic enigma. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2009;133(12):1989–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinarvand P, Lai J. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a rare entity with unique features. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2017;141(7):990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Rosa S, Bongiovanni M. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: key pathologic and genetic features. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2020;144(7):829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai Y, Ran X, Xie S, et al. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: a large series from a single institution. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2014;18(5):935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Heffess CS. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a typically cystic carcinoma of low malignant potential. 2000:66–80. [PubMed]

- 6.Pitman M, Deshpande V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of the pancreas: a morphological and multimodal approach to the diagnosis of solid and cystic mass lesions. Cytopathology. 2007;18(6):331–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Layfield LJ, Ehya H, Filie AC, et al. Utilization of ancillary studies in the cytologic diagnosis of biliary and pancreatic lesions: the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology guidelines for pancreatobiliary cytology. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2014;42(4):351–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B-A, Li Z-M, Su Z-S, She X-L. Pathological differential diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm and endocrine tumors of the pancreas. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2010;16(8):1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yina Jiang M, Xie J, Yudong Mu M, Peijun Liu M. TFE3 is a diagnostic marker for solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sheikh ZA, Alali AA, Almousawi FA, Das DK. Solid pseudo-papillary tumor of the pancreas: Diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemistry. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P, Hu Y, Yi J, Li J, Yang J, Wang J. Identification of potential biomarkers to differentially diagnose solid pseudopapillary tumors and pancreatic malignancies via a gene regulatory network. Journal of translational medicine. 2015;13(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foo WC, Harrison G, Zhang X. Immunocytochemistry for SOX-11 and TFE3 as diagnostic markers for solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas in FNA biopsies. Cancer cytopathology. 2017;125(11):831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison G, Hemmerich A, Guy C, et al. Overexpression of SOX11 and TFE3 in Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasms of the Pancreas. American journal of clinical pathology. 2018;149(1):67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo JS, Jung W, Hong SW. Cytologic characteristics and β-catenin immunocytochemistry on smear slide of cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Acta cytologica. 2011;55(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohara Y, Oda T, Hashimoto S, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm: Key immunohistochemical profiles for differential diagnosis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016;22(38):8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka Y, Kato K, Notohara K, et al. Significance of aberrant (cytoplasmic/nuclear) expression of beta-catenin in pancreatoblastoma. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2003;199(2):185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss V, Dueber J, Wright JP, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2016;8(8):615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.