Abstract

The National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) is a database including health insurance claim and specific health checkup data. Observational studies using real-world big data attract attention because they have certain strengths, including external validity and a large sample size. This review focused on research using the dental formula of the NDB because the number of teeth is an important indicator of oral health. The number of teeth present calculated using the dental formula of periodontitis patients was similar to that from the Survey of Dental Diseases. In addition, the graphs of the presence rates of tooth types by 5-year age groups from the NDB were smoother and had less overlap than those from the Survey of Dental Diseases, and they could detect slight changes in the presence rate that reflected sugar consumption before and after World War II. Using the NDB, a low number of teeth was associated with high medical care expenditures, high risk of aspiration pneumonia, and high risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Although there are some restrictions on the use of the NDB, we hope that dental research using the NDB will be further promoted in the future.

Keywords: National Database, Administrative database, Health insurance claim, Dental formula, Number of teeth

1. Introduction

A universal healthcare system covering most citizens was established in Japan in 1961 [1]. Costs of the health service are largely covered by contributions from insurance societies or public funding, with copayment (up to 30% of the cost) that varies depending on age and income of beneficiaries and types of medical and dental services provided. Hospitals and clinics including dental clinics prepare health insurance claims for individual patients every month and send them to the corresponding insurers through the Health Insurance Claims Review and Reimbursement Services, thereby receiving appropriate reimbursement.

The National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) is a database that stores data of health insurance claims and of specific health checkups [2]. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) started operating the NDB together with passage of the “Act on Assurance of Medical Care for Elderly People” of 2008. The primary purpose of the establishment of the NDB was to obtain statistical data useful in formulating plans regarding medical care expenditure regulations. However, since 2011, the NDB has been used secondarily for research purposes and has become one of the most exhaustive healthcare databases of a national scale in the world.

The NDB includes almost all (≥95%) claims data regarding medical and dental treatments and specific health checkups and provides a complete picture of the real-world clinical situation in Japan [3]. Information contained in the NDB includes age, sex, diagnoses, inpatient medical data, outpatient medical data, dental service use, drug prescriptions, and health checkup data. Before obtaining NDB data for research purposes, researchers must submit their study protocols to the NDB expert council. After the protocols are approved, a contract with MHLW is made to use a dataset extracted from the NDB for the purpose of the study. Only researchers in national or local government agencies, universities, and other quasi-public entities can request access to the NDB. Data extracted from the NDB are provided to researchers after information about specific patients and medical facilities has been anonymized. Researchers must adhere to the guideline for the use of the NDB, based on which they are obligated to use the dataset only in a pre-specified secure room.

In recent years, the use of healthcare claims databases has been promoted to assess healthcare intervention utilization patterns or outcomes [3]. Observational studies using real-world big data have several strengths compared to randomized, controlled trials [4]. The strengths include external validity, a large sample size, and lower cost and shorter time period than interventional studies, including randomized, clinical trials [5]. Studies in the field of dentistry have been published using healthcare claims databases in the USA [6], Taiwan [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]], and South Korea [14]. Because the healthcare claims database includes information about treatment, the majority of the studies examined the effects of dental treatment.

We were the first in the field of dentistry to be provided access to the NDB for research in Japan and have focused on use of the dental formula to contribute to dental health policy. The aim of this review is to present the current state of research evidence using the dental formula from the NDB in Japan.

2. Study selection

A search for papers was conducted in PubMed and Ichushi-web (a search engine for medical studies in Japanese). Search terms and results were (“national claims database” OR “national health insurance claims database” OR “national database” OR “national insurance claims database” OR “nationwide health insurance claims data” OR “nationwide administrative claims database”) AND “Japan”. The academic output lists of the NDB reported by the MHLW from January 2011 to May 2020 were checked because the lists are thought be a complete record of all academic output using the NDB data. Abstracts and titles were then reviewed. A manual search using the reference lists of the included studies was also conducted. A total of five papers [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]] were extracted (Table 1), of which three [15,17,18] were written in Japanese.

Table 1.

List of original papers dealing with dental formula information of the NDB in Japan.

| Authors | Year | Title | Journal | Volume: pages | Language | Subjects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Ishii T, Wada Y, Sugiyama S. | 2016 | Association between number of teeth and medical and dental care expenditure -analysis using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database in Japan-. | Jpn J Dent Pract Admin | 51: 136–42 | Japanese | Patients aged 40 or older diagnosed as having periodontitis | [15] |

| Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Okumura Y, Kato G, Ishii T, Sugiyama S, et al. | 2017 | Number of teeth and medical care expenditure. | Health Sci Health Care | 17: 36–7 | English | Patients aged 50-79 diagnosed as having periodontitis | [16] |

| Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Ishii T, Sato T, Yamaguchi T, Makino T. | 2017 | Association between number of teeth and medical visit due to aspiration pneumonia in older people using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database. | Jpn J Gerodontol | 32: 349–56 | Japanese | Patients aged 65 or older diagnosed as having periodontitis and missing teeth | [17] |

| Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Yamaguchi T. | 2019 | The presence of teeth by tooth type using the dental notation of periodontitis patients: a cross-sectional study using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database in Japan. | Jpn J Dent Pract Admin | 54: 184–90 | Japanese | Patients aged 20 or older diagnosed as having periodontitis | [18] |

| Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Yamaguchi T, Kodama T, Sato T. | 2021 | Association between number of teeth and Alzheimer’s disease using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. | PLoS ONE | 16: e0251056 | English | Patients aged 60 or older diagnosed as having periodontitis and missing teeth | [19] |

3. Research evidence using the dental formula from the NDB in Japan

3.1. Presence of teeth by tooth type and the number of teeth present using the dental formula of periodontitis patients

Because NDB data do not include information about the number of teeth present, the information about the dental formula of patients with the diagnosis of “periodontitis” was used. Patients who undergo periodontal treatment including supportive periodontal treatment or periodontal maintenance are diagnosed with periodontitis using the dental formula of all teeth present.

The validity of the presence rate of each tooth type and of the number of teeth present calculated from the dental formula of periodontitis patients registered in the NDB was examined by comparing the rate calculated from the Survey of Dental Diseases [18,20]. Data for sex, age group, and dental formula from 5,654,554 periodontitis patients in April 2016 in the NDB and data from the Survey of Dental Diseases in 2016 were used. The presence rate of each tooth type, excluding third molars, was calculated in each sex and age group of periodontitis patients aged 20 years or older. Moreover, the number of teeth present for each periodontitis patient was counted using the dental formula.

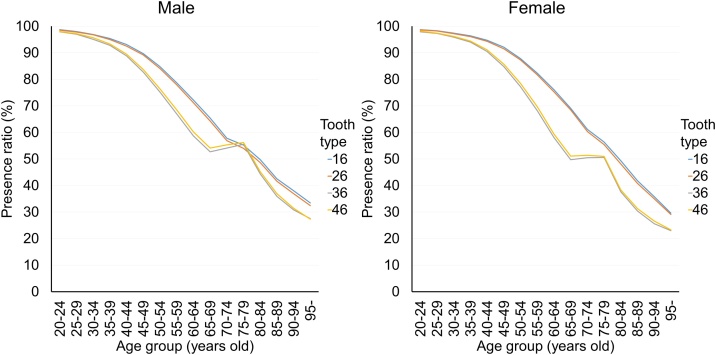

The shape of the graphs from the NDB was similar to and smoother than from the Survey of Dental Diseases (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). In addition, the number of intersections made by graphs depicting age groups from the NDB was smaller than from the Survey of Dental Diseases. In 20–69-year-olds, presence rates from the NDB were similar to those from the Survey of Dental Diseases.

Fig. 1.

Presence rate of each tooth type by age group in the NDB and the Survey of Dental Diseases (Male) (reproduced with permission from the original article [18]). NDB: 2,454,747 subjects aged 20 years or older diagnosed as having periodontitis. Survey of Dental Diseases: 1357 subjects aged 20–84 years old.

Fig. 2.

Presence rate of each tooth type by age group in the NDB and the Survey of Dental Diseases (Female) (reproduced with permission from the original article [18]). NDB: 3,499,807 subjects aged 20 years or older diagnosed as having periodontitis. Survey of Dental Diseases: 1836 subjects aged 20–84 years old.

The mean number of teeth present using the NDB was 0.2–0.9 less than that using the Survey of Dental Diseases in 20–64-year-olds. The difference in the mean number of teeth present between the two databases increased in subjects aged 60 years or older, and in 85–89-year-olds, the difference was 4.8.

These results suggest that the NDB includes the data lacking in the Survey of Dental Diseases. One strength of the NDB is that it includes a complete survey conducted every month, which reflects real-world data on dental care. Therefore, increased use of the NDB is expected.

In the NDB, the presence rates of the mandibular first molars did not decrease with age for both males and females, but crossed over (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The presence rates of the mandibular first molars were higher in 75–79-year-olds than in 65–69-year-olds (Fig. 3). The main reason for this crossover in the presence rate was as follows. The people aged 75–79 years in 2016 had the lowest consumption of sugar and the lowest incidence of dental caries due to the Second World War, as the period when they were 5–6 years of age corresponded to 1942−1947. On the other hand, the period when they were 5–6 years of age for people aged 65–69 years corresponded to 1952–1957, when sugar consumption increased rapidly and dental caries also increased in incidence. For this reason, it is possible that the difference in caries incidence in the first molars may have affected the difference in the loss rate. This issue can be seen in the NDB data with a large number of subjects (n = 5,654,554), but not in the Survey of Dental Diseases (n = 3,329).

Fig. 3.

Presence rate of the first molars by age group and sex in the NDB (reproduced with permission from the original article [18]). NDB: 2,454,747 males and 3,499,807 females aged 20 years or older diagnosed as having periodontitis.

3.2. Association between number of teeth present and medical care expenditure

Many epidemiological studies have shown the association between tooth loss and diseases including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and dementia [21]. In addition, an association of the number of teeth present with medical care expenditure has been reported using national health insurance data with a relatively small number of subjects (n = 273) in Japan [22]. We examined the association of the number of teeth with medical and dental care expenditures using the NDB in Japan [15,16].

Dental prescription data with a diagnosis of periodontitis in April 2013 were combined with medical prescription data, including diagnosis procedure combination and pharmacy. Medical and dental expenditures were compared between the two groups by number of teeth (19 or less and 20 or more) in each sex and each 5-year age group from 40 years of age (Fig. 4). Subjects with 19 or less teeth had significantly higher medical care expenditures than those with 20 or more teeth in both sexes and all age groups, except 80 years or older in both sexes (p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U-test). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in both sexes and all age groups except for those 60–64 years of age and those 85 years of age or older in females.

Fig. 4.

Association between number of teeth present and median medical expenditure in each age group and each sex (graphs created using the data of the original article [15]). Black bar: subjects diagnosed as having periodontitis and having 19 or fewer teeth, 289,686 males and 414,226 females aged 40 years or older. Gray bar: subjects diagnosed as having periodontitis and having 20 or more teeth, 646,966 males and 881,105 females aged 40 years or older.

To identify associations between the number of teeth (independent variable) and medical expenditures (primary outcome) while controlling for sex, generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log-link function were constructed using maximum likelihood estimation. Since the likelihood ratio test for interaction between age groups and number of teeth was significant (p < 0.001), the models were constructed by age group. The models showed that medical care expenditures increased by 2.4% for each tooth lost in patients in their 50s (multiplicative effect, 0.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–0.98). The association was attenuated in patients in their 60s (multiplicative effect, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.98–0.99) and in those in their 70s (multiplicative effect, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99–0.99). These results confirmed that subjects having more teeth incur lower medical care expenditures.

3.3. Association between number of teeth and aspiration pneumonia in older people

The association of the number of teeth present and missing teeth with medical visits due to aspiration pneumonia in older people was analyzed using the NDB in Japan [17]. Data of dental care claims of patients aged 65 years or older having a diagnosis of periodontitis (n = 1,662,158) or missing teeth (n = 356,662) in April 2013 were combined with those of medical care claims with a diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia including outpatient care, inpatient care, and pharmacy. Numbers of teeth present and missing teeth were calculated using the dental formula in the claims for periodontitis and missing teeth, respectively, and categorized into three groups each.

Percentages of subjects treated for aspiration pneumonia in those having 20–32, 10–19, and 1–9 teeth were 0.08%, 0.14%, and 0.25%, respectively. Percentages of subjects treated for aspiration pneumonia in those having 1–14, 15–27, and 28–32 missing teeth were 0.09%, 0.18%, and 0.43%, respectively. Logistic regression models using treatment of aspiration pneumonia as an outcome variable and adjusting for age and sex showed that odds ratios for those having 10–19 teeth and 1–9 teeth (reference: 20–32 teeth) were significant, at 1.20 and 1.53, respectively (Fig. 5). Logistic regression models using treatment of aspiration pneumonia as an outcome variable and adjusting for age and sex showed that odds ratios for those having 15–27 missing teeth and 28–32 missing teeth (reference: 1–14 missing teeth) were significant, at 1.67 and 3.14, respectively. In conclusion, older people having fewer teeth present and more missing teeth were more likely to visit medical doctors due to aspiration pneumonia among subjects who visited dentists due to periodontitis or missing teeth.

Fig. 5.

Association between numbers of teeth present and missing teeth and aspiration pneumonia (graphs created using the data of the original article [17]). The left graph shows the association between the number of teeth present and aspiration pneumonia using 1,662,158 subjects diagnosed as having periodontitis. The right graph shows the association between the number of missing teeth and aspiration pneumonia using 356,662 subjects diagnosed as having missing teeth.

Odds ratios adjusted for age and sex and the 95% confidence intervals.

3.4. Association between number of teeth and Alzheimer’s disease in older people

Associations of numbers of teeth present and of missing teeth with Alzheimer’s disease were cross-sectionally analyzed using the NDB in Japan [19]. Dental care claims data of patients aged 60 years or older diagnosed with periodontitis (n = 4,009,345) or missing teeth (n = 662,182) were used to obtain information about the numbers of teeth present and of missing teeth, respectively, and they were combined with medical care claims data including the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Numbers of teeth present and of missing teeth excluding third molars were calculated using the dental formula in the claims for periodontitis and missing teeth, respectively, and categorized into three groups each.

Percentages of subjects treated for Alzheimer’s disease with 20–28, 10–19, and 1–9 teeth present were 1.95%, 3.87%, and 6.86%, respectively, in patients diagnosed as having periodontitis, and those treated for Alzheimer’s disease with 1–13, 14–27, and 28 missing teeth were 2.67%, 5.51%, and 8.70%, respectively, in patients diagnosed as having missing teeth. Logistic regression models using treatment for Alzheimer’s disease as an outcome variable and adjusting for age and sex showed that odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for patients with 10–19 and 1–9 teeth (reference: 20–28 teeth) were 1.11 (1.10–1.13) and 1.34 (1.32–1.37), respectively, (p < 0.001), in patients diagnosed as having periodontitis, and odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for patients with 14–27 missing teeth and 28 missing teeth (reference: 1–13 missing teeth) were 1.40 (1.36–1.44) and 1.81 (1.74–1.89), respectively, (p < 0.001), in patients diagnosed as having missing teeth (Fig. 6). In conclusion, the results of the present study using Japanese dental claims data showed that older people visiting dental offices with fewer teeth present and a greater number of missing teeth are more likely to have Alzheimer’s disease.

Fig. 6.

Association between numbers of teeth present and missing teeth except the third molars and Alzheimer’s disease (graphs created using the data of the original article [19]). The left graph shows the association between the number of teeth present except the third molars and Alzheimer’s disease using 4,009,345 subjects diagnosed as having periodontitis. The right graph shows the association between the number of missing teeth except the third molars and Alzheimer’s disease using 662,182 subjects diagnosed as having missing teeth.

Odds ratios adjusted for age and sex and the 95% confidence intervals.

4. Limitation

We have focused on using the dental formula of the NDB because the number of teeth is one of the most important indicators for health science research in dentistry. The number of teeth present calculated using the dental formula of periodontitis patients was similar to that from the Survey of Dental Diseases in 20–69-year-olds. However, the difference was increased in patients aged 70 years or older. The increased difference might be due to the increase in the number of edentulous people among older people, because edentulous people are not diagnosed as having periodontitis.

Because the NDB is a healthcare claims database, there are other limitations. First, the severity of the disease is unknown, and information about socioeconomic status is not available. However, it also has the advantage of being able to be verified in the real world because it records the results of all insured medical and dental treatment. Second, the number of teeth with dental records of periodontitis was used as the number of present teeth; therefore, the number of permanent teeth and the number of deciduous teeth under 20 years of age cannot be calculated. Third, when using disease names (periodontitis, aspiration pneumonia, Alzheimer’s disease) in the analysis, the disease name codes with the largest numbers of patients must be used. Table 2 shows the example of variables that are available from the NDB. Fourth, the NDB includes only the data of patients who visited clinics and/or hospitals; therefore, it is impossible to obtain data from people who did not visit such institutions. For example, when looking at medical and dental collaboration, both medical and dental receipts must be available. In other words, only the data of people who visit both medical and dental institutions can be analyzed. Fifth, we have not conducted quality checks of data from the NDB. However, studies examined the validity of data from NDB in Japan using sensitivity analyses, and showed that the recorded medical and dental diagnoses and procedures were useful in research using the administrative data [[23], [24], [25]].

Table 2.

Example of codes for diagnosis and procedure of dental disease.

| Diagnosis | Codes |

|---|---|

| Dental caries | 8843836 |

| Pulpitis | 5220063 |

| Periapical periodontitis | 8833899 |

| Alveolar abscess | 5225006 |

| Root stump | 8834149 |

| Periodontitis | 5234009 |

| Gingivitis | 5231018 |

| Gingival abscess | 5233008 |

| Pericoronitis | 5233009 |

| Missing teeth | 5250001 |

| Procedure | Codes | |

|---|---|---|

| Caries treatment | 309000110 | |

| Atraumatic indirect pulp capping | 309001010 | |

| Direct pulp capping | 309001110 | |

| Pulpectomy | Number of root canal: 1 | 309002110 |

| Number of root canal: 2 | 309002210 | |

| Number of root canal: 3 or more | 309002310 | |

| Infected root canal treatment | Number of root canal: 1 | 309003010 |

| Number of root canal: 2 | 309003110 | |

| Number of root canal: 3 or more | 309003210 | |

| Condensation technique of root canal filling | Number of root canal: 1 | 309014310 |

| Number of root canal: 2 | 309014410 | |

| Number of root canal: 3 or more | 309014510 | |

| Initial preparation (scaling for sextant) | 309004810 | |

| Initial preparation (scaling and root planing) | Front tooth | 309005310 |

| Premolar | 309005410 | |

| Molar | 309005510 | |

| Tooth extraction | Deciduous tooth | 310000110 |

| Front tooth | 310000210 | |

| Molar or premolar | 310000310 | |

| Impacted tooth | 310000510 | |

| Setting of bridge | Number of abutment teeth and pontics: 5 or less | 313005010 |

| Number of abutment teeth and pontics: 6 or more | 313005110 | |

| Setting of full dentures | 313005510 | |

5. Conclusions

The number of publications using the NDB in Japan in the area of dentistry is still small, but it is gradually increasing with expanding research topics. For example, a retrospective cohort study showed that preoperative oral care by a dentist reduced postoperative complications in patients who underwent major cancer surgery [26]. Other studies showed greater tooth loss in patients with diabetes mellitus compared to those without diabetes mellitus [27], and diabetes patients with fewer teeth had higher medical expenditures [28].

Although the NDB has these limitations, it also has many advantages, as we have discussed. We hope that research in this field will continue to expand in the future.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This work did not receive any grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Matsuda S. Health policy in Japan — current situation and future challenges. JMA J. 2019;2:1–10. doi: 10.31662/jmaj.2018-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato G. History of the secondary use of National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) Trans Jpn Soc Med Biol Eng. 2017;55:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirose N., Ishimaru M., Morita K., Yasunaga H. A review of studies using the Japanese National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups. Ann Clin Epidemiol. 2020;2:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden T.R. Evidence for health decision making — beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:465–475. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1614394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson E.K., Nelson C.P. Values and pitfalls of the use of administrative databases for outcomes assessment. J Urol. 2013;190:17–18. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasseh K., Vujicic M., Glick M. The relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization. Evidence from an Integrated Dental, Medical, and Pharmacy Commercial Claims Database. Health Econ. 2017;26:519–527. doi: 10.1002/hec.3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S.J., Liu C.J., Chao T.F., Wang K.L., Chen T.J., Chou P., et al. Dental scaling and atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2300–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y.L., Hu H.Y., Yang N.P., Chou P., Chu D. Dental prophylaxis decreases the risk of esophageal cancer in males; a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y.L., Hu H.Y., Huang L.Y., Chou P., Chu D. Periodontal disease associated with higher risk of dementia: population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1975–1980. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C.K., Huang J.Y., Wu Y.T., Chang Y.C. Dental scaling decreases the risk of Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide population-based nested case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1587. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu C.L., Lin W.S., Lin C.H., Liu J. The effect of professional fluoride application program for preschool children in Taiwan: an analysis using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) J Dent Sci. 2018;13:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh Y.T., Wang B.Y., Lin C.W., Yang S.F., Ho S.W., Yeh H.W., et al. Periodontitis and dental scaling associated with pyogenic liver abscess: a population-based case-control study. J Periodontal Res. 2018;53:785–792. doi: 10.1111/jre.12567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin H.W., Chen C.M., Yeh Y.C., Chen Y.Y., Guo R.Y., Lin Y.P., et al. Dental treatment procedures for periodontal disease and the subsequent risk of ischaemic stroke: a retrospective population-based cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46:642–649. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radnaabaatar M., Kim Y.E., Go D.S., Jung Y., Jung J., Yoon S.J. Burden of dental caries and periodontal disease in South Korea: an analysis using the national health insurance claims database. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019;47:513–519. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuneishi M., Yamamoto T., Ishii T., Wada Y., Sugiyama S. Association between number of teeth and medical and dental care expenditure -analysis using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database in Japan. Jpn J Dent Pract Admin. 2016;51:136–142. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuneishi M., Yamamoto T., Okumura Y., Kato G., Ishii T., Sugiyama S., et al. Number of teeth and medical care expenditure. Health Sci Health Care. 2017;17:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuneishi M., Yamamoto T., Ishii T., Sato T., Yamaguchi T., Makino T. Association between number of teeth and medical visit due to aspiration pneumonia in older people using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database. Jpn J Gerodontol. 2017;32:349–356. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuneishi M., Yamamoto T., Yamaguchi T. The presence of teeth by tooth type using the dental notation of periodontitis patients: a cross-sectional study using the Receipt and Health Checkup Information Database in Japan. Jpn J Dent Pract Admin. 2019;54:184–190. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuneishi M., Yamamoto T., Yamaguchi T., Kodama T., Sato T. Association between number of teeth and Alzheimer’s disease using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health and Labour and Welfare. Survey of Dental Diseases: Summary of Results. Available online 25 September 2021 from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/62-17b.html.

- 21.Seitz M.W., Listl S., Bartols A., Schubert I., Blaschke K., Haux C., et al. Current knowledge on correlations between highly prevalent dental conditions and chronic diseases: an umbrella review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E132. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwasaki M., Sato M., Yoshihara A., Ansai T., Miyazaki H. Association between tooth loss and medical costs related to stroke in healthy older adults aged over 75 years in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:202–210. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamana H., Moriwaki M., Horiguchi H., Kodan M., Fushimi K., Yasunaga H. Validity of diagnoses, procedures, and laboratory data in Japanese administrative data. J Epidemiol. 2017;27(10):476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara K., Tomio J., Svensson T., Ohkuma R., Svensson A.K., Yamazaki T. Association measures of claims-based algorithms for common chronic conditions were assessed using regularly collected data in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono S., Ishimaru M., Ida Y., Yamana H., Ono Y., Hoshi K., et al. Validity of diagnoses and procedures in Japanese dental claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1116. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishimaru M., Matsui H., Ono S., Hagiwara Y., Morita K., Yasunaga H. Preoperative oral care and effect on postoperative complications after major cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1688–1696. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki S., Noda T., Nishioka Y., Imamura T., Kamijo H., Sugihara N. Evaluation of tooth loss among patients with diabetes mellitus using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. Int Dent J. 2020;70:308–315. doi: 10.1111/idj.12561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki S., Noda T., Nishioka Y., Myojin T., Kubo S., Imamura T., et al. Evaluation of public health expenditure by number of teeth among outpatients with diabetes mellitus. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2021;62:55–60. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.2020-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]