Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to describe the cause of death and characteristics at the prehospital setting associated with care and rescue processes of non-survivors rescued in the mountain of Japan.

Design

Retrospective analysis.

Setting

Prehospital setting of mountain searches and rescues in Japan. A total of 10 prefectural police headquarters with >10 cases of mountain death from 2011 to 2015.

Participants

Data were generated from the existing records. Of the total 6159 rescued subjects, 548 mountain deaths were caused by recreational activities.

Results

Among the 548 mountain deaths, 83% were men, and major causes of death were trauma (49.1%), hypothermia (14.8%), cardiac death (13.1%) and avalanche-related death (6.6%). The alive rate at rescue team arrival in all non-survivors was 3.5%, with 1, 4 and 14 cases of cardiac, hypothermia and trauma, respectively. Cardiac deaths occurred in 93.1% (67/72) of men and individuals aged >41 years, and 88.7% (63/71) were found on mountain trails. In hypothermia, callouts were made between 17:00 and 6:00 at 49% (40/81) and by persons not on-site in 59.7% (46/77). People with >6 hours in trauma or >1 hour in cardiac death already died on rescue team arrival, but some with hypothermia after 6 hours were alive.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first large-scale retrospective analyses of prehospital non-survivors in mountain emergencies. The alive rate at rescue arrival in all mountain deaths was only 3.5%. These data showed that the circumstances related to onset and the process until the rescue team arrives have different characteristics, depending on the cause of death. Survival may be enhanced by targeting better use of the time before rescue team arrival and by providing further education, particularly mountain rescue-related medical problems to rescuers including bystanders.

Keywords: accident & emergency medicine, medical education & training, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is one of the first large-scale analyses of prehospital non-survivors who were rescued during recreational mountain activities.

This study provides the alive rate of deaths on rescue team arrival, and the care and rescue processes of the prehospital setting time are evaluated for enhancing survival for each major cause of death.

This research targeted the rescued people in Japan, and from a universal perspective of injury and illness, the results of this study can be generalised; however, the generalisation of the results may be limited since the topography, weather and rescue systems vary, depending on the country and mountain area.

Introduction

Numerous people visit mountainous areas for recreational activities; in the 2016 official statistics of Japan, 11.37 million people aged >10 years joined mountaineering in 2015.1 Considering the topographic features, weather conditions, activity duration, and heavy and/or inadequate equipment, mountain activities can be physically demanding and can lead to serious injuries or death. The mountain rescue team in Japan comprises police organisations. According to the National Police Agency report, the total callouts in 2015 were 3043, of which 11% died (335/3043). Considering this information, >300 people die in Japan’s mountainous areas annually.2 Mountain fatalities were retrospectively studied, and trauma, acute altitude illness (AAI), hypothermia, avalanche burial and sudden cardiac death (SCD) were the most common causes.3–6 However, few studies have examined the cause of death and the characteristics at the prehospital setting in recreational mountain activities internationally3 7 or in Japan. We conducted a large-scale analysis of non-survivors rescued in Japan between 2011 and 2015. We aimed to clarify the causes and frequency of mountain deaths and identify the onset and rescue response circumstances and the prehospital setting time course to develop possible measures to strengthen the response and enhance survival chances during emergency situations in the mountain.

Methods

Data source

After each mountain rescue mission, police officers record the event on the rescue report form, which is kept for the annual rescue report for 5 years. This report covers all rescued people in Japan. We collected such reports from police headquarters within all prefectures that had over 10 mountain death cases between January 2011 and December 2015 (the last 5 years in which records were kept as of 2016 when this study began). The head of police mountain rescue personnel in the included prefectures retrospectively obtained data from the documented information survey items, such as age; sex; date and time of six points (start of activity, onset, callout, rescue team arrival, hospital arrival and death confirmation); the mechanism; number of groups; person making the callout; presence or absence of any signs of life based on four points (at the onset, callout, rescue team arrival and hospital arrival); implementation and type of medical intervention on-site; trigger of accident; cause of death; coexistence findings; information of onset and the found site such as weather, altitude, terrain features; and mode of travel such as ascent, descent, ridge, rest, at the hut, sleeping, which did not contain individual-level identifying data. Any signs of life were considered ‘alive’. The National Police Agency and the competent authority of each prefectural police headquarters approved the use of the aforementioned information for this study and mailed it to us. All postmortem examinations were done by physicians or coroners. Autopsies were not conducted because no crime and/or trouble was suspected.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in designing, conducting, reporting or disseminating this research.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as median and IQR, whereas categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Proportions were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, and the continuous data were compared using one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis test. Furthermore, a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were stored using Excel V.2019 and analysed using EZR V.1.54 (Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) modified R commander.

Results

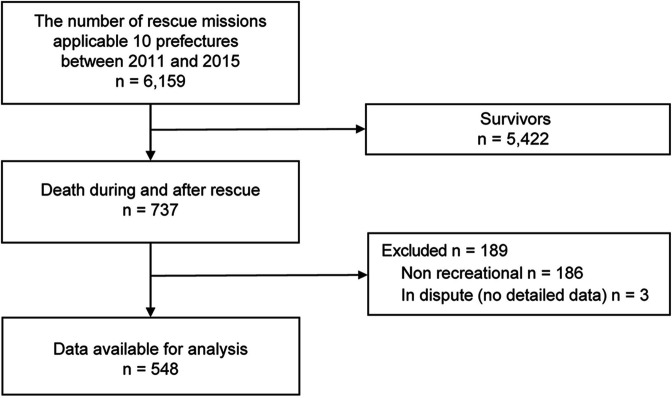

Figure 1 illustrates the process of inclusion and exclusion of cases. After exclusion, 548 cases were analysed, with 455 (83.0%) men and 95 (17.0%) women and a median age of 60 (46–68) years and 62 (53–68) years, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the inclusion and exclusion processes.

Causes of death and alive rate at rescue team arrival

The overall fatality rate (FR) (number of death/number of callouts) was 12.0% (737/6159).

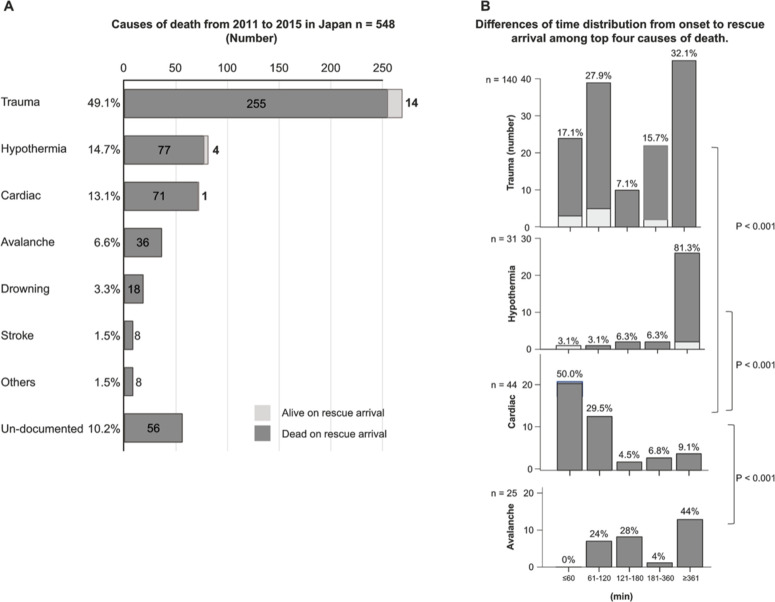

Figure 2A shows the cause of death and the number of alive victims during rescue team arrival. The causes of the majority of the deaths were the following: trauma (49.1%, 269), hypothermia (14.8%, 81), cardiac death (13.1%, 72) and avalanche-related death (6.6%, 36). During rescue team arrival, only 3.5% (19) were alive. Of these 19 alive cases, 14 (5.2% of 269), 4 (4.9% of 81) and 1 (1.4% of 71) exhibited trauma, hypothermia and cardiac death, respectively.

Figure 2.

Cause of death, time distribution until rescue arrival, and the number of alive subjects between 2011 and 2015 in Japan. (A) The overall number of deaths and the number of alive subjects during rescue team arrival according to cause (B) differences in time distribution and the number of alive subjects from the onset to rescue arrival between the top four causes of death.

Regional differences in mortality outcomes

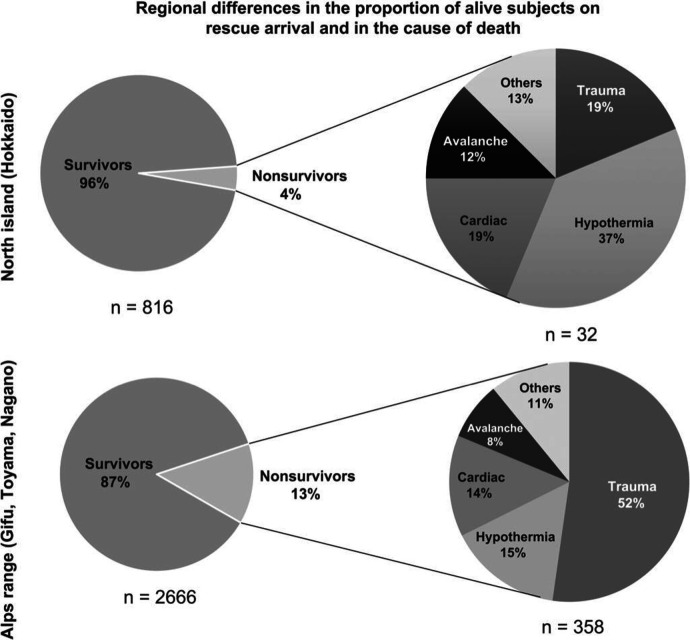

Figure 3 shows the differences between the north island (Hokkaido) and Japanese Alps range (Nagano, Toyama, Gifu) in terms of the cause of death, its frequency and FR. The major cause of death was hypothermia in Hokkaido (FR: 4.1%, 32/784) and trauma in the Alps range (FR: 15.5%, 358/2308).

Figure 3.

Regional differences in the proportion of alive subjects on rescue arrival and in the cause of death.

Table 1 summarises the characteristics stratified by the top four causes of death, namely, trauma, hypothermia, cardiac death and avalanche, in 458 subjects. In cardiac death, the percentage of male victims was high (93.1%, 67/72), and all victims were >41 years of age (p<0.001). Meanwhile, those who had avalanche-related deaths were the youngest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of four major causes of death in Japan from 2011 to 2015

| Trauma | Hypothermia | Cardiac death | Avalanche-related | P value | |

| n | 269 | 81 | 72 | 36 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 213 (79.2) | 70 (86.4) | 67 (93.1) | 32 (88.9) | 0.022 |

| Female | 56 (20.8) | 11 (13.6) | 5 (6.9) | 4 (11.1) | 0.022 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 60 (47–67) | 59 (43–68) | 64.5 (58.8–71) | 48 (39–58.3) | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| ≤20 | 5 (1.9) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.29 |

| 21–40 | 44 (16.4) | 15 (18.5) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (30.6) | <0.001 |

| 41–60 | 98 (36.4) | 26 (32.1) | 29 (40.3) | 18 (50.0) | 0.286 |

| 61–80 | 119 (44.2) | 37 (45.7) | 43 (59.7) | 7 (19.4) | 0.001 |

| ≥81 | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.548 |

| Caller | |||||

| By oneself | 3 (1.1) | 4 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.177 |

| Accompanied | 91 (34.7) | 18 (23.4) | 26 (37.1) | 17 (48.6) | 0.194 |

| Passerby | 77 (29.4) | 9 (11.7) | 27 (38.6) | 9 (25.7) | 0.015 |

| Not on-site | 91 (34.7) | 46 (59.7) | 17 (24.3) | 9 (25.7) | 0.001 |

| Group size | |||||

| Solo | 130 (48.3) | 44 (54.3) | 21 (29.2) | 6 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Group | 139 (51.7) | 36 (44.4) | 51 (70.8) | 30 (83.3) | <0.001 |

| Contact location | |||||

| On trail (multiple choices) | 87 (41.0) | 35 (49.3) | 63 (88.7) | 1 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Hazardous | 126 (59.2) | 38 (53.5) | 6 (8.5) | 35 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Done | 18 (6.7) | 7 (8.6) | 24 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

Type of trauma and avalanche-related death

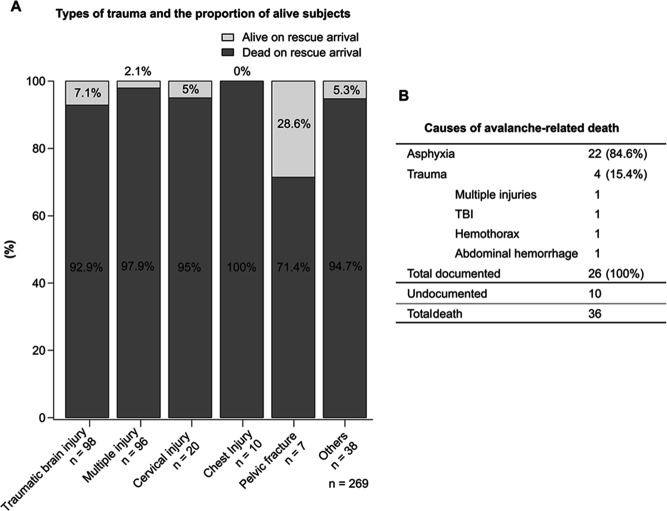

Figure 4 shows the trauma types, avalanche-related death and alive victim proportion during rescue arrival. The types of trauma included traumatic brain injury (TBI) (36.4%, 98/269), multiple injuries (35.7%, 96/269), cervical spine injury (7.4%, 20/269), chest injury (3.7%, 10/269), pelvic fracture (2.6%, 7/269) and others/undocumented (14.1%, 38/269), but only 7.1% (7/98), 2.1% (2/96), 5.0% (1/20), 0% (0/10) and 28.6% (2/7) were alive at rescue arrival, respectively.

Figure 4.

(A) Types of trauma and the proportion of alive subjects. (B) Causes of avalanche-related death. TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Avalanche-related death was mainly caused by asphyxia (84.6%, 22/26) followed by trauma (15.4%, 4/22). Unfortunately, none were alive when the rescue team arrived.

Characteristics at the time of occurrence

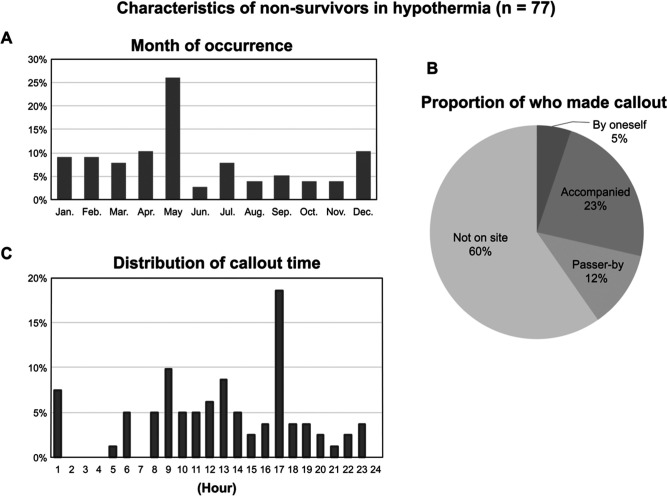

In trauma death, the mechanisms of injury (excluding the undocumented) were fall (94%, 222/236) and falling rocks (3.0%, 7/236). The predominant injury was blunt trauma. Meanwhile, figure 5 shows the characteristics of hypothermia. Hypothermia deaths were recorded every month and most frequently in May (26%, 20/81), followed by April (10.4%, 8/81), both spring months, and then in December (10.4%, 8/81), which is the winter month. The callout time peaked at 17:00 and was between 17:00 and 6:00 at 49% (40/81); those made by themselves and persons not on-site accounted for 5.2% (4/77) and 59.7% (46/77), respectively. Regarding cardiac death, the callout time peaked at 11:00 and was 7:00–13:00 in 70.8%. In addition, 88.7% (63/71) of cardiac death cases were found on mountain trails (p<0.001), while 59.2% (126/223) of trauma cases and 53.5% (38/71) of hypothermia cases were found at the hazardous areas such as snow, rock and ice (p<0.001) (table 1).

Figure 5.

Characteristics of non-survivors in hypothermia. (A) Month of occurrence. (B) Proportion of people who made the callout. (C) Distribution of callout time.

Figure 2B shows the differences of time distribution from onset to rescue arrival between the top four causes. The proportion of within 1 hour from the onset to rescue arrival was 17.1% (24/140) for trauma, 3.1% (2/67) for hypothermia, 50.0% (22/44) for cardiac death and 0% in avalanche.

On-site treatment

On-site treatment was done in 31.1% (59/190) of documented cases. The most applied treatment was cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) followed by automated external defibrillators (AEDs) (applied with or without record of shock), rewarming, bleeding control, immobilisation and oxygen therapy (44, 7, 6, 4, 1 and 1, respectively). Of the 44 CPRs, 22, 11, 2 and 1 were cases of cardiac death, trauma, stroke and drowning, respectively. In cardiac death, 75.9% (22/29) underwent CPR, and 6.8% (5/7), including a bystander, underwent AED. However, the CPR initiation and duration time, presence or absence of shock and return of spontaneous circulation achievement were not specified in the record. Meanwhile, rewarming was provided in six hypothermia cases (three were initiated by bystanders) and zero trauma cases.

Discussion

In Japan, the major cause of mountain deaths during the designated period was trauma followed by hypothermia, cardiac death and then avalanche-related death. In our study, the alive rate of all non-survivors on rescue team arrival was only 3.5%. In a mountainous prehospital setting, on-site physicians and technical support such as cardiac monitoring, which confirms death, are generally unavailable in Japan. Confirming death by the absence of vital signs is unreliable; hence, correctly recognising death immediately after death is extremely difficult.8 The classification of being alive can still be uncertain, thereby possibly affecting the number of alive subjects on rescue arrival. In addition, although all deaths were confirmed by physicians or coroners, autopsy was not performed for all, which may influence the cause of death of an unwitnessed cardiac arrest. Highly frequented regions such as Nagano, and victims who were found skeletonised more than a few months later might also have influenced the results. However, our 5-year data showed no hitting peaks or troughs of fluctuating trends by year, and many factors affected the length of interval from callout to recovery. Factors such as terrain, weather and search technique can greatly affect the outcome of mountain rescue. Thus, our results can be considered valid for the overall picture of mountain death in Japan for 5 years. The cause of death reported by international research varies by region. In Denali, between 1903 and 2006, the main cause of death among the 96 included cases was trauma followed by hypothermia, AAI and cardiac death (43, 44.8%; 16, 16.7%; 7, 7.3%; and 1, 1%, respectively).5 In Aconcagua Provincial Park, between 2001 and 2012, death in 33 included cases was also mainly caused by trauma but followed by AAI, hypothermia and cardiac death (9, 27.2%; 7, 21.2%; 5, 15.2%; and 4, 12.1%, respectively).6 In our study, trauma and hypothermia showed similar trends, but no AAI deaths were noted. The incidence of high-altitude pulmonary oedema, which is fatal, is reportedly 0.3% at 3500 m altitude.9 However, our study showed that Japan’s mountains are not high enough to cause altitude-related deaths often. Even in Japan, the causes and frequency of death and the FR differed by region. In the present study, the FR was not the mortality rate for the number of mountaineers because such number remains uncertain. This study intended to consider enhancing the survival by focusing on people who need rescue. The FR was clearly lower in the north island than in the Alps range (figure 3). In contrast to trauma and cardiac death, hypothermia gradually developed and progressed, which allowed survival for a longer time until rescue. This notion could be one of the reasons causing the regional differences in FR in Japan. Previously, the alive rate of all non-survivors on rescue team arrival was 7% (4/57) in Scottish mountain,10 and 85% of rural trauma victims died at the prehospital setting in Norway,11 with 2 years of observation period. Our 5-year results support that in remote environments, most deaths occur on the site before rescue team arrival.

According to previous studies, the main mechanism of injury associated with trauma in the mountains is a fall (59.6%).5 10 12 In our study, 95% of trauma deaths were caused due to falls. Therefore, falls are the major cause of death and the major mechanism of trauma. The larger the fall distance, the higher the risk of fatality3; however, we could not obtain data regarding the fall height for most of the victims; these data could enhance our study’s contributions to the field. Recently, the incidences of major trauma have increased in the elderly, and the main mechanism is a fall from a height of >2 m.13 The pathophysiological response to trauma, anatomical and physiological fragility, and potential higher serious comorbidities in older individuals can increase the probability of major trauma from low-velocity mechanisms in this age group, which leads to a higher FR and early death than those in younger people.14 15 These findings potentially impact the low alive rate at rescue arrival in the current study. The occurrence of cardiac death was higher in men aged >41 years; this was similar to previous reports focusing on the European Alps, in which 90%–95% were men, all were >34 years of age.4 In our study, the time of collapse in an unwitnessed arrest was impossible to estimate, but at least 48.8% of the cases resulted in death within 1 hour of onset, which corresponded to SCD.16 Ageing is a strong risk predictor of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), which increases after the age of 35 years. Moreover, SCD is more common among men rather than women in all age groups.17 The prevalence of SCD in mountain fatalities can be attributed to such finding. Additionally, the incidence of sudden death is several times higher during exercise than at other times.18 Unfortunately, in Japan, where many mountaineers are already in middle age, SCD will continue to occur, according to previous findings.

Regarding the time factors, the major causes of death were significantly different from the onset to rescue arrival (figure 2B). Concerning the time from the onset to callout, if signal is available, callout can be made in a short time in trauma-related, cardiac death-related and avalanche-related accidents with apparent onset. In hypothermia, approximately half of the callout was made after around twilight. Previously, hypothermia deaths tended to occur as a result of injury.5 In our study, secondary to trauma by 17.5% (14/81); thus, most of the hypothermia cases were primary because of prolonged exposure to heat loss, bad weather, and fasting. When hypothermia progresses to stage ≥2, the victims lose their judgement because of the decreased level of consciousness. Moreover, lone subjects were mostly men, and the onset of hypothermia was unclear. Consequently, making callouts on the site becomes impossible once the stage progresses. These views are the reasons why 59.7% of the callout was from a person who was not at the site, such as a family member, after recognising that the casualty had not returned home. Therefore, the dispatch of the rescue team was delayed, and the hypothermia stage had further progressed. Additionally, most cardiac deaths occurred on a mountain trail, which shortened the required time to search and locate casualties. Conversely, searching for fall (trauma) and hypothermic casualties in places that require a technical rescue process was more time consuming. Regarding the time from the onset to rescue team arrival, our results revealed that at least 83% of trauma deaths took >60 min to be rescued, and no alive cases were rescued in >6 hours. In previous studies, an out-of-hospital time (OHT) exceeding 60 min was observed in 84% and 67% of mountain trauma and helicopter rescue cases, respectively,12 19 which led to an increased mortality rate in seriously injured patients.20 Meanwhile, mountain rescue operations have a longer OHT (mean: 117.4±142.9 min) associated with a prolonged treatment-free interval (TFI) than rescue operations in non-alpine areas (68.7±28.6 min), but there was no difference in the hospital mortality.12 Moreover, the mortality within the first hour of injury was high, between 70% and 80% regardless of rurality.11 In our study, though some casualties possibly had life-threatening injuries, we found alive cases even with a prolonged OHT. Factors that can contribute to survival other than a short OHT should be specified.

In the cardiac death group (non-survivors), only one victim was alive when the rescue team arrived, despite an increased rate of rescue team arrival within 1 hour. Survival from SCA is inversely correlated with the interval from collapse to definitive care,21 22 and in SCD, the best outcome reported was from the occurrence site with a publicly recognisable advanced emergency response system.23 In the present study, 52.1% (38/73) of callouts were made by a companion or a passerby and at least 24.7% (18/73) of cardiac arrest incidences were witnessed. However, the current emergency response system in the mountains has to overcome various hurdles before better outcomes can be achieved.

Considering on-site treatment, the number of on-site interventions was greater than that of the alive subjects. Given that some cases had undetectable vital signs, death could hardly be confirmed.

With correct implementation of first aid in blunt trauma, mortality potentially decreased by 4.5%.24 In the present study, 28.6% (2/7) had pelvic fracture, and 7.1% (7/98) had TBI death after rescue arrival. Early diagnosis and treatment may prevent death caused by pelvic exsanguination.25 Pelvic binders were 70% effective in stabilising the pelvis.26 In severe TBI, basic airway management with oxygen administration obtained a better outcome than endotracheal intubation with oxygen administration for hypoxia prevention (SaO2 ≤94%).27 28 Despite the fact that our results do not demonstrate statistical significance, they encourage the implementation of and training on these procedures for life-saving in remote environments, considering the background of reported evidence. For hypothermia, on-site rewarming is safe and effective,29 but the implementation rate on rescue arrival is low. Appropriate rewarming with mountain equipment showed good recovery at the site by non-medical persons when casualty transportation was difficult during bad weather or at night.30 In this study, even after 6 hours from callout, alive cases were found. Early callout, first-aid skill education and dispatcher-assisted rewarming contribute to a shortened TFI and increase the chances of survival. In our study, CPR interventions were highest in cardiac death. Most SCAs were found on busy mountain trails where a bystander is likely to be present. However, the quality of chest compressions apparently decreases in 5–10 min at an altitude of 3454 m.31 CPR implementation in the mountains is restricted by various technical issues, including chest compression quality, AED availability, ventilation requirement and human resources, as well as the safety of rescuers, such as the bystander’s advanced age, the terrain, the longer interval from onset to rescue arrival, and the weather. Moreover, dispatcher-assisted CPR is effective in treating out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.32 When heart attack is suspected, prompt callouts should be made to use dispatch-assisted CPR instructions. The decisions to implement, hold and terminate CPR should be supported.

The limitation of this study lies in its retrospective nature; analyses were performed based on data extracted from the information recorded in each regional format. Police record formats are unified by region but not nationwide. Although the facts of field activities by rescue teams are recorded, the emergency setting in the mountain that has restricted circumstances can hinder the recording of accurate prehospital time-stamped patient data. For this reason, some data were missing. Future research needs to construct a standardised data collection system to reduce missing data in collaboration with the dispatcher centre and hospitals and to collate with other topographical areas, considering the limited number of deaths.

In conclusion, the leading causes of death in the mountains in Japan are trauma, hypothermia, SCD and avalanche-related deaths. The alive rate on rescue arrival in non-survivors was only 3.5%. No survival was observed in >6 hours in trauma and >1 hour in cardiac death cases, but a longer survival time was observed in cases of hypothermia. Early intervention into pelvic fracture and TBI, which have higher alive rate on rescue arrival, and major improvement in early recognition leading to early callout and initiation of effective rewarming in hypothermia cases can possibly enhance survival by shortening TFI. Heart attack cases mostly correspond to SCD; however, due to the obvious onset, occurrence on mountain trail, probable early callout and easy locating, the time until rescue arrival can be better used for survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the following organisations in collecting the data: National Police Agency, Hokkaido, Aomori, Yamagata, Fukushima, Niigata, Gunma, Nagano, Toyama, Gifu and Shizuoka Prefectural Polices. The authors also thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KazueOshiro

Contributors: KO contributed to the acquisition and analysis and drafted the manuscript. KO and TM contributed to the conception and design, critically revised the manuscript, contributed to interpretation, gave the final approval, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure integrity and accuracy, and read and agreed to the publication of the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. KO is the guarantor of the work and accepts full responsibility for the presented content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. All data provided were from the National Police Agency and the competent authority of each prefectural police headquarters, which approved the use for this study by the authors. National Police Agency +813-3581-0141Hokkaido Prefectural Police +8111-251-0110Aomori Prefectural Police +8117-723-4211 Yamagata Prefectural Police +8123-626-0110Fukushima Prefectural Police +8124-522-2151 Niigata Prefectural Police +8125-285-0110 Gunma Prefectural Police +817-243-0110 Nagano Prefectural Police +8126-233-0110Toyama Prefectural Police +8176-441-2211Gifu Prefectural Police +8158-271-2424Shizuoka Prefectural Police +8154-271-0110

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities . Survey on time use and leisure activities questionnaire a results on leisure activities summary table 3 participation rate and average days for participation in sports by sex and age | file | browse statistics | portal site of official statistics of Japan, 2016. Available: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200533&tstat=000001095335&cycle=0&tclass1=000001095377&tclass2=000001095378&tclass3=000001095379&stat_infid=000031577972&tclass4val=0 [Accessed 31 Jan 2021].

- 2.Overview of mountain accidents during 2015, 2016. Available: https://www.jma-sangaku.or.jp/tozan/document/17320160706h27_sangakusounan.pdf

- 3.Windsor JS, Firth PG, Grocott MP, et al. Mountain mortality: a review of deaths that occur during recreational activities in the mountains. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:316–21. 10.1136/pgmj.2009.078824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtscher M, Ponchia A. The risk of cardiovascular events during leisure time activities at altitude. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;52:507–11. 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh SE, Campbell AD, Dow J, et al. Mountaineering fatalities on Denali. High Alt Med Biol 2008;9:89–95. 10.1089/ham.2008.1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westensee J, Rogé I, Van Roo JD, et al. Mountaineering fatalities on Aconcagua: 2001-2012. High Alt Med Biol 2013;14:298–303. 10.1089/ham.2013.1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell G. Mountain rescue transport. Injury 1975;6:306–8. 10.1016/0020-1383(75)90178-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schön CA, Gordon L, Hölzl N, et al. Determination of death in mountain rescue: recommendations of the International Commission for mountain emergency medicine (ICAR MedCom). Wilderness Environ Med 2020;31:506–20. 10.1016/j.wem.2020.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purkayastha SS, Ray US, Arora BS, et al. Acclimatization at high altitude in gradual and acute induction. J Appl Physiol 1995;79:487–92. 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.2.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hearns S. The Scottish mountain rescue casualty study. Emerg Med J 2003;20:281–4. 10.1136/emj.20.3.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakke HK, Steinvik T, Eidissen S-I, et al. Bystander first aid in trauma - prevalence and quality: a prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015;59:1187–93. 10.1111/aas.12561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauch S, Dal Cappello T, Strapazzon G, et al. Pre-hospital times and clinical characteristics of severe trauma patients: a comparison between mountain and urban/suburban areas. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:1749–53. 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehoe A, Smith JE, Edwards A, et al. The changing face of major trauma in the UK. Emerg Med J 2015;32:911–5. 10.1136/emermed-2015-205265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruijns SR, Guly HR, Bouamra O, et al. The value of traditional vital signs, shock index, and age-based markers in predicting trauma mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1432–7. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829246c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayoung-Chee P, McIntyre L, Ebel BE, et al. Long-term outcomes of ground-level falls in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:498–503. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myerburg RJ CA. Cardiac arrest and sudden death. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders, 1997: 742–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myerburg RJ. Sudden cardiac death: exploring the limits of our knowledge. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12:369–81. 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vuori I. The cardiovascular risks of physical activity. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1986;711:205–14. 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb08951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietsch U, Strapazzon G, Ambühl D, et al. Challenges of helicopter mountain rescue missions by human external cargo: need for physicians onsite and comprehensive training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2019;27:17. 10.1186/s13049-019-0598-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampalis JS, Lavoie A, Williams JI, et al. Impact of on-site care, prehospital time, and level of in-hospital care on survival in severely injured patients. J Trauma 1993;34:252–61. 10.1097/00005373-199302000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasunaga H, Miyata H, Horiguchi H, et al. Population density, call-response interval, and survival of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Int J Health Geogr 2011;10:26. 10.1186/1476-072X-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koike S, Ogawa T, Tanabe S, et al. Collapse-to-emergency medical service cardiopulmonary resuscitation interval and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest: a nationwide observational study. Crit Care 2011;15:R120. 10.1186/cc10219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malta Hansen C, Kragholm K, Pearson DA, et al. Association of bystander and first-responder intervention with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in North Carolina, 2010-2013. JAMA 2015;314:255–64. 10.1001/jama.2015.7938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashour A, Cameron P, Bernard S, et al. Could bystander first-aid prevent trauma deaths at the scene of injury? Emerg Med Australas 2007;19:163–8. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Søreide K, Krüger AJ, Vårdal AL, et al. Epidemiology and contemporary patterns of trauma deaths: changing place, similar PACE, older face. World J Surg 2007;31:2092–103. 10.1007/s00268-007-9226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Höch A, Zeidler S, Pieroh P, et al. Trends and efficacy of external emergency stabilization of pelvic ring fractures: results from the German pelvic trauma registry. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2021;47:523–31. 10.1007/s00068-019-01155-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumann G, Moens D, Brink B, et al. Multiple trauma management in mountain environments - a scoping review : Evidence based guidelines of the International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine (ICAR MedCom). Intended for physicians and other advanced life support personnel. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2020;28:117. 10.1186/s13049-020-00790-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pakkanen T, Kämäräinen A, Huhtala H, et al. Physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical service has a beneficial impact on the incidence of prehospital hypoxia and secured airways on patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:94. 10.1186/s13049-017-0438-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haverkamp FJC, Giesbrecht GG, Tan ECTH,. The prehospital management of hypothermia - An up-to-date overview. Injury 2018;49:149–64. 10.1016/j.injury.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshiro K, Murakami T, Nishimura K. Hokkaido Police’s hypothermia wrapping method: The reducing effect of heat loss and successful cases in mountain rescues. Jpn J Mt Med 2015;35:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger A, Niederer M, Tscherny K, et al. Influence of physical strain at high altitude on the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2020;28:19. 10.1186/s13049-020-0717-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohm K, Vaillancourt C, Charette ML, et al. In patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, does the provision of dispatch cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructions as opposed to NO instructions improve outcome: a systematic review of the literature. Resuscitation 2011;82:1490–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. All data provided were from the National Police Agency and the competent authority of each prefectural police headquarters, which approved the use for this study by the authors. National Police Agency +813-3581-0141Hokkaido Prefectural Police +8111-251-0110Aomori Prefectural Police +8117-723-4211 Yamagata Prefectural Police +8123-626-0110Fukushima Prefectural Police +8124-522-2151 Niigata Prefectural Police +8125-285-0110 Gunma Prefectural Police +817-243-0110 Nagano Prefectural Police +8126-233-0110Toyama Prefectural Police +8176-441-2211Gifu Prefectural Police +8158-271-2424Shizuoka Prefectural Police +8154-271-0110