Summary

Lipids play important roles in various human diseases. Disease-associated lipid dysregulation and biomarkers could provide molecular clues for diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. This protocol provides a step-by-step workflow to investigate lipid dysregulation and discover biomarkers in human serum samples by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based lipidomics and machine learning analysis. The workflow includes project design, serum collection, sample preparation, data acquisition, data processing, and machine learning analysis.

For complete details on the use and execution of this profile, please refer to Hao et al. (2021).

Subject areas: Bioinformatics, Health Sciences, Clinical Protocol, Metabolism, Mass Spectrometry, Biotechnology and bioengineering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

LC-MS based lipidomics for large-scale profiling of human serum samples

-

•

Identification and quantitation of serum lipids based on MS-DIAL

-

•

An effective feature selection approach for discovery of biomarkers

Lipids play important roles in various human diseases. Disease-associated lipid dysregulation and biomarkers could provide molecular clues for diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. This protocol provides a step-by-step workflow to investigate lipid dysregulation and discover biomarkers in human serum samples by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based lipidomics and machine learning analysis. The workflow includes project design, serum collection, sample preparation, data acquisition, data processing, and machine learning analysis.

Before you begin

The general workflow for investigating lipidomic dysregulation and discovering lipid biomarkers in cohort study includes project design, sample collection, sample preparation, data acquisition and data analysis. Typically, the data quality of lipidomic analysis could be achieved by controlling the stability and reproducibility of the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analytical processes. However, the project design that determines the whole rationale of the study, and the quality and standardization of sample collection are more challenging in clinical study. In addition, the abundant data generated by MS-based untargeted lipidomics need the elaborate development of machine learning methods for data mining. Therefore, we must rationally consider these procedures before you start the project.

Project design

Timing: days to weeks

The project design for a given study depends on the biological questions and the expected outcomes of the research. This process often requires the joint participation and discussion of clinical biologists and analytical chemists. Compared with studies of model systems (e.g., in vitro cultured cells or animal models) which can be operated in a well-controlled experimental environment, individual diversity must be intensively considered for studies of human subjects, as a variety of physiological conditions and exogenous factors may lead to dynamic changes in lipidic content in blood. Large-scale epidemiological studies are required to provide statistical confidence. Factors that may result in bias in serum lipidome should be well matched in control samples compared to cases. These factors mainly include age, sex, body mass index (BMI), fasting and feeding, circadian rhythm, exercise and stress, drugs and nutritional supplements, and comorbidity. The minimum sample size should be estimated to conclude the statistical meaningful results by performing biostatistics analysis (e.g., power analysis by MetaboAnalyst (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/)). Besides, ethical approval from the local research ethics committee should be applied before the collection of any blood samples.

Serum collection and storage

Timing: weeks to months

The blood lipidome may experience highly dynamic and pronounced changes in vitro due to the high levels of active enzymes and the intrinsic instability of some lipids. Therefore, the sample collection and storage procedure must be strictly controlled to minimize these undesired alterations. We suggest drawing the blood samples from a suitable vein into proper serum collection tubes and allowing them to clot at 25°C for 30 min. Then separate serum from other components of blood immediately by centrifugation at 1,500 g for 10 min at 4°C. The separate serum should be divided into small aliquots immediately at 4°C and stored at −80°C until the sample preparation procedure begins.

Note: Considering the ease of operation and the need of repeated injections in case the LC-MS analysis procedure fails, we recommend using about 50 μL of serum for lipid extraction, so the minimum blood volume required is about 150 μL.

CRITICAL: To avoid potential infection risk with bloodborne pathogens especially for some certain infectious diseases, the sample collection process should comply with biological safety rules strictly, perform all work with appropriate personal protection equipment including laboratory coats, goggles, masks, and gloves.

CRITICAL: If a clotting time of 30 min is not realistic during the operation procedure, it should be kept consistent across all samples within 60 min (to avoid cell lysis) to avoid divergent variations of serum lipids by activated platelets and circulating enzymes between groups.

CRITICAL: Hemolytic samples should be excluded from study, as they may cause the release of intracellular components which will alter the lipid profile of serum.

CRITICAL: Repeated freeze–thaw cycles should be avoided.

Alternatives: Plasma samples are also widely used in lipidomic studies.

For more detailed information about the effects of pre-analytical processes on blood samples used in metabolomic studies, please refer to our paper (Yin et al., 2015).

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Water | Made in house by Millipore Direct-Q5 | Cat # ZRQS VP500 |

| Acetonitrile | Fisher chemical | Cat # A998-4 |

| Isopropanol | Fisher chemical | Cat # A451-4 |

| Ethanol | Fisher chemical | Cat # A995-4 |

| Formic acid | Aladdin | Cat # F112034-100mL |

| Ammonium formate | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent | Cat # 30011661 |

| Sodium hydroxide | Innochem | Cat # A36865-500g |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| DataAnalysis | Bruker | Cat # 1867357 |

| Analysis Base File Converter | Reifycs | http://www.reifycs.com/AbfConverter/index.html |

| CompassXtract (V 3.2.201) | Bruker | https://www.bruker.com/cn/service/support-upgrades/software-downloads/mass-spectrometry/compass-tools.html |

| MS-DIAL (version 4.24) | (Tsugawa et al., 2020) | http://prime.psc.riken.jp/compms/msdial/main.html |

| R (version 4.0.2) | R Foundation for Statistical Computing | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| Python (version 3.7.7) | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org/ |

| Scikit-learn (version 0.22.1) | Python community project | https://scikit-learn.org |

| Numpy (version 1.18.1) | Python community project | https://numpy.org/ |

| Pandas (version 1.0.5) | Sponsored Project of NumFOCUS | https://pandas.pydata.org/ |

| Matplotlib (version 3.1.3) | Sponsored Project of NumFOCUS | https://matplotlib.org/ |

| Compass Hystar | Bruker | Cat # 1850838 |

| Cytoscape | Cytoscape Consortium | https://cytoscape.org/ |

| Other | ||

| UltiMate 3000 UHPLC System | DIONEX, Thermo Fisher Scientific | n/a |

| TIMS-TOF mass spectrometer | Bruker | n/a |

| ACQUITY BEH C18 column, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm | Waters Corporation | Cat # 186008316 |

| Vortex mixer | SCILOGEX | Cat # 821200059999 |

| Centrifuge | Sigma-Aldrich | D-37520 |

| Refrigerator (4°C) | Haier | HYC-650 |

| Freezer ( − 80°C) | Haier | DW-86L626 |

| 200 μL Pipet tips | Axygen | LOT # 13921233 |

| 1 mL Pipet tips | Axygen | LOT # 28620930 |

| 1 mL Pipette | Sartorius | LOT # 19078248 |

| 200 μL Pipette | Sartorius | LOT # 4539504473 |

| 1.5 mL Centrifugal tube | Axygen | LOT # 18921962 |

| 2 mL Screw Agilent HPLC Vials | Agilent | Cat #5182-0716 |

| 250 μL Glass insert, deactivated | Agilent | Cat #5181-8872 |

| Blue screw cap, pre-slit PTFE/sil septa | Agilent | Cat #5185-5865 |

Materials and equipment

10 mM Sodium Formate Solution for Mass Calibration

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Milli-Q water | n/a | 50 mL |

| Isopropanol | n/a | 50 mL |

| Formic acid | n/a | 100 μL |

| Sodium hydroxide | n/a | 400 mg |

Note: The solution was stable during the whole experimental process (1 month) by storing at 4°C in a glass vial.

CRITICAL: Sodium hydroxide should be added to the solvent after formic acid to prevent corrosion of the glass bottle by strong alkali.

CRITICAL: Isopropanol is toxic and highly flammable, and it should be handled in a fume hood. Formic acid is corrosive and volatile, and should be handled in a fume hood. Sodium hydroxide is corrosive. Laboratory coats, goggles, masks, and gloves should be worn when working with these materials.

10 M Ammonium Formate Stock Solution

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Milli-Q water | n/a | 10 mL |

| Ammonium formate | 10 M | 6.3 g |

Note: The solution should be freshly prepared just before use.

CRITICAL: Ammonium formate is considered as a skin, eye, and respiratory irritant. Laboratory coats, goggles, masks, and gloves should be worn when working with this material.

Solvent A for LC-MS analysis

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Milli-Q water | n/a | 1600 mL |

| Acetonitrile | n/a | 2400 mL |

| Formic acid | 0.1% (v%) | 4 mL |

| 10M Ammonium Formate Solution | 10 mM | 4 mL |

Note: Mix and degas the solvents by ultrasonic for 15 min. Prepare an adequate amount of solvent for the whole experimental procedure at one time to avoid retention time shift. The solution should be freshly prepared just before use.

CRITICAL: Acetonitrile is toxic and highly flammable and should be handled in a fume hood. Laboratory coats, goggles, masks, and gloves should be worn when working with this material.

Solvent B for LC-MS analysis

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | n/a | 400 mL |

| Isopropanol | n/a | 3600 mL |

| Formic acid | 0.1% (v%) | 4 mL |

| 10M Ammonium Formate Solution | 10 mM | 4 mL |

Note: Mix and degas the solvents by ultrasonic for 15 min. Prepare an adequate amount of solvent for the whole experimental procedure at one time to avoid retention time shift. The solution should be freshly prepared just before use.

CRITICAL: Do not use detergents and laboratory dishwasher to wash the solvent bottles.

LC-MS setup for untargeted lipidomic analysis

The lipidomics analysis was performed on an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC System (DIONEX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.S.A.) coupled with a TIMS-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) in both positive and negative ion modes, respectively. The MS parameters are listed in Table 1.

Note: 10 mM sodium formate solution was injected into the mass spectrometer at the beginning 0.5 min of each sample analysis process using a 1 mL syringe at a flow rate of 1 μL/min by a 6-port diverter valve for post-injection mass calibration.

Note: Dynamic exclusion was activated by excluding the precursor ions for MS/MS acquisition after they had been acquired 3 times and releasing them after 0.2 min. The precursor ion was reconsidered if its current intensity was 2-fold of the previous intensity.

Note: Default values were used for all other parameters that are not listed here.

Table 1.

MS parameters for untargeted lipidomic analysis

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Ionization | Electrospray ionization |

| Capillary | 4200 V |

| Nebulizer | 2.0 Bar |

| Dry Gas | 10.0 L/min |

| Dry Temperature | 200°C |

| Syringe Pump | Enabled |

| Diverter Valve | 6 Port |

| Stepping | Not Enabled |

| TIMS | Not Enabled |

| Scan Mode | Auto MS/MS (Data Dependent Acquisition) |

| Absolute Threshold (per 1000 sum) | 500 cts |

| MS1 and MS2 mass ranges | m/z 100–1000 |

| Scan Rates for MS1 and MS2 | 10 Hz |

| Cycle time | 0.5 s |

| Active Exclusion | Enabled |

| Collision energy (positive mode / negative mode) | +30/−30 eV |

| Reference List for Calibration | Na Formate |

The UHPLC separation was performed on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) at 35°C. ACN/H2O (6:4, v/v) and IPA/ACN (9:1, v/v), both containing 10 mM NH4COOH and 0.1% (v%) Formic acid (FA), were employed as mobile phase A and B, separately. 80% Methanol was used for syringe wash. Gradient elution was achieved with the following program in Table 2.

Note: 80% Methanol was used for syringe wash in our work considering its similar polarity with 75% ethanol extract of serum. However, for more classic lipid extraction method using chloroform-methanol or methyl tert-butyl ether–methanol as described in the “sample preparation for LC-MS analysis” part, we recommend solvents with lower polarity to wash the syringe to avoid residual and cross contamination, such as isopropanol. The ratio of mobile phase B should be further increased to 100% and maintained for about 5min for LC gradient elution to ensure effective elution of lipids with low polarity, such as triacylglycerol (TG).

Table 2.

LC gradient elution program for untargeted lipidomic analysis

| Time (min) | Flow rate (mL/min) | Gradient (% B) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.3 | 30 |

| 2.0 | 0.3 | 52 |

| 3.5 | 0.3 | 63 |

| 5.0 | 0.3 | 68 |

| 6.0 | 0.3 | 64 |

| 12.5 | 0.3 | 74.5 |

| 13.5 | 0.3 | 80 |

| 14.5 | 0.3 | 30 |

| 19.0 | 0.3 | 30 |

Step-by-step method details

An overview of the workflow of the protocol is summarized in Figure 1. The serum samples were slowly thawed at 4°C and then extracted by ethanol for lipids (steps 1–10). The extracts were injected into the LC-MS system for untargeted lipidomics (steps 11–19). The acquired data were imported to MS-DIAL 4 for identification and quantitation of serum lipids (steps 20–26). Statistical analysis including differential expression analysis and differential correlation analysis was performed to investigate the disease-related lipidomic dysregulations (steps 27–28). To investigate the potential of serum lipid dysregulation for clinical diagnosis of the studied disease, biomarkers discovery (steps 29–32) and machine learning were further performed (steps 33–37).

Figure 1.

An overview of the experimental and computational procedures of the protocol

Serum samples were extracted by ethanol. Quality control (QC) sample was generated by mixing equal volumes of each sample. Blank samples were prepared by extraction of Milli-Q water. These samples were injected for LC-MS analysis in the order as shown in the figure. The acquired data was imported to MS-DIAL for peak alignment, blank filter, lipid identification and quantification. The obtained peak area matrix of serum lipids was finally used for statistical analysis and machine learning for investigation of lipid dysregulation and discovery of lipid biomarkers.

Sample preparation for LC-MS analysis

Timing: 1–2 day for ∼300 samples

-

1.

Slowly thaw the serum samples (50 μL/sample) at 4°C.

-

2.

Add 150 μL ice-cold ethanol to each sample to make a final solution of 75% (v/v) ethanol.

Note: Ethanol was used as the extraction solvent for serum lipids in our study to ensure inactivation of viruses. It can sufficiently extract most classes of lipids including phosphatidylcholine (PC), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). However, its extraction efficiency was not satisfactory considering some highly hydrophobic lipids such as triacylglycerol. For extraction of total serum lipids, we suggest the Bligh and Dyer (1959) or Folch (Folch et al., 1957) method, or methyl tert-butyl ether−methanol (MTBE-MeOH) method (Matyash et al., 2008), which are the most commonly used methods.

Note: Use of internal standards can correct possible deviations from sample preparation to LC-MS analysis, making quantification more accurate and reliable. Readers can refer to (Wang et al., 2017) for suggestions for more accurate quantification using internal standards.

-

3.

Vortex the mixture vigorously for 5 min to ensure sufficient lipid extraction and protein precipitation.

-

4.

Centrifuge the mixture at 1,6200×g, 4°C for 5min and collect 150 μL of the supernatant to a new 1.5mL tube.

-

5.

Incubate the supernatant at −80°C for 12h to facilitate protein precipitation.

-

6.

Centrifuge the mixture again at 4°C, 1,6200×g for 10 min and collect the supernatant to a new 0.5mL tube carefully without disturbing the pellet for final LC-MS analysis.

Note: −80°C incubation and repeat centrifugation of the samples can remove the serum proteins more adequately and thus reduce the risk of clogging of the LC separation column in the subsequent analysis procedure.

-

7.

Prepare a pooled quality control (QC) sample by mixing equal volumes of each sample (10–20 μL depending on the sample size).

Note: The pooled QC sample contains all the lipid features of the biological samples under study. So, it can be used to measure the stability of the data acquisition procedure for all the detected features. Features with excessive shift in retention time, signal intensity and mass accuracy can be excluded for subsequent statistical analysis or be corrected before further analysis.

-

8.

Divide the QC samples into small aliquots of 50 μL/sample and transfer them into pre-labeled glass inserts assembled in glass vials respectively. Seal the vials with screw caps and tap the bottom of each vial to release air bubbles present at the bottom. Store the samples at −80°C until LC-MS analysis.

Note: Dividing the QC samples into small aliquots can avoid long-time placement of QC samples in the sampler at 4°C in the subsequent analysis procedure.

-

9.

Divide the rest of each sample into small aliquots of 20–30 μL/sample and transfer them into pre-labeled glass inserts assembled in glass vials respectively. Seal the vials with screw caps and tap the bottom of each vial to release air bubbles present at the bottom. Store the samples at −80°C until LC-MS analysis.

Note: Dividing the analysis samples into small aliquots can avoid repeated freezing and thawing in the subsequent analysis procedure, as freshly thawed aliquots can be separately used for positive and negative mode. The remained aliquots can be used in case re-analysis is required.

-

10.

Prepare blank samples by extraction of Milli-Q water using the same procedure as for serum and transfer them into pre-labeled glass inserts assembled in glass vials respectively. Seal the vials with screw caps and tap the bottom of each vial to release air bubbles present at the bottom. Store the samples at −80°C until LC-MS analysis.

CRITICAL: To avoid potential infection risk with bloodborne pathogens, perform all work with appropriate personal protection equipment.

Note: Sample preparation order should be randomized to avoid possible systematic biases.

Untargeted lipidomic analysis based on LC-TIMS-TOF/MS

Timing: 20 min/sample, 10 days for ∼300 samples in positive and negative ion mode

-

11.

Perform preventative instrument maintenance including cleaning and washing of the pipelines, electrospray needles and MS ion source according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

-

12.

Prepare mobile phase A, mobile phase B and sodium formate solution as described in the ‘‘materials and equipment’’ section.

-

13.

Install the HPLC solvent lines into the HPLC solvent reservoirs

-

14.

Purge the solvent lines A and B separately at a flow rate of 3 mL/min for 5 min.

-

15.

Equilibrate the LC and MS system for at least 0.5h using the parameters in Tables 1 and 2.

Note: Check the state of the LC-TIMS-TOF/MS system according to the manufacturer’s guidelines before sampling, mainly including column pressure, background noise, MS sensitivity, signal stability, etc. See troubleshooting 1 for the high back pressure of the system.

-

16.

Calibrate the MS system using the sodium formate solution by direct injection using a syringe.

-

17.

Take the samples out of the −80°C refrigerator followed by thawing at 4°C. Vortex the samples again to make a homogenous solution. Put them in the UPLC autosampler operating at 4°C.

Note: Take one QC sample and 60 analysis samples every one day for analysis, this allows a maximal exposure time of all samples at 4°C to be within 24 h, thus avoiding lipids’ deterioration during the long-time storage at 4°C.

-

18.

Create a batch table as shown in Figure 1. 5 Blank samples are injected at the start of the analytical batch followed by 10 QC samples. Then insert pooled QC samples once every nine analytical samples. The last sample in the batch should also be QC.

Note: Sample analysis order should be randomized and different from sample preparation order to avoid possible systematic biases.

Note: Blank samples should not be inserted in the subsequent analysis procedure to avoid disturbance of the equilibrium state of the system.

Note: QC samples should be inserted at least once every fifteen analytical samples. More frequent data acquisition of QC samples may increase the accuracy of subsequent corrections of MS signals, if needed.

-

19.

Analyze samples in positive and negative ion mode separately. Chromatographic separations and MS detection are performed as described in the ‘‘materials and equipment’’ section.

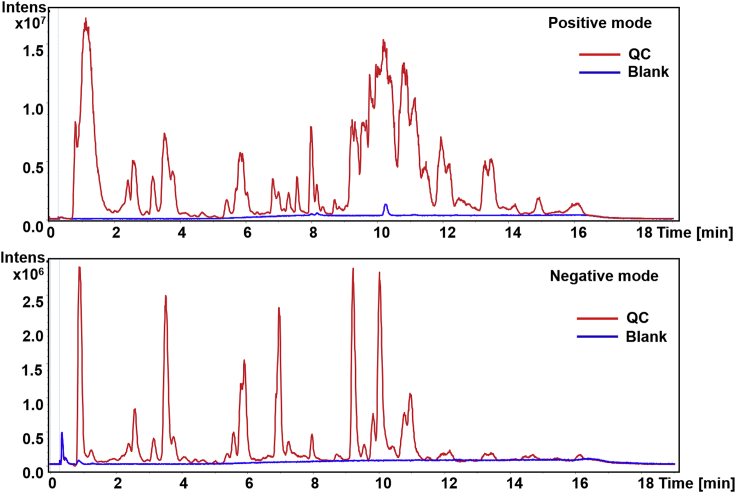

Note: Perform pre-experiments to check the possibility of carry over, this can be realized by injection of blank samples after a continuous analysis of real samples. Ensure that no peaks of lipids are observed in the total ion chromatography (TIC) of blank samples or no lipids can be identified by MS-DIAL. If this problem occurs, wash the column with 100% mobile phase B for about 5 min at the end of each separation process before being balanced to the initial mobile phase ratio. In our previous work, the TIC of QC and blank are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

TIC of QC and blank samples (after sample injection) in positive and negative mode

Note: Injection volume was set as 5 μl for positive ion mode and 10μl for negative ion mode due to the low sensitivity of negative ion mode.

Note: All samples were first analyzed in positive ion mode. Then switch the polarity of the MS to negative and repeat step 11–18 for analysis in negative ion mode.

Note: Check the signal of the blank samples to ensure that the LC-MS system is free of contamination. See troubleshooting 2 for high background signals in blank samples.

Note: The continuous injection of multiple QC samples at the beginning of the analysis process is carried out for two reasons. The first is to equilibrate the LC-MS system with the sample matrix to block the active sites after preventative maintenance. It has been reported that the first eight injections for LC-MS are not reproducible (Zelena et al., 2009). The second is to check the stability of the LC-MS system.

Note: The direct contact of sample components with many parts of the LC-MS system may cause contamination of the instrument, which may lead to bias of the analytical result. So, we must check the stability of the data acquisition process frequently. This can be realized by analyzing the drift of retention time, accurate mass, and peak area of the detected features in QC samples during the analysis process. In general, the retention time shift within 0.15 min across all QC samples indicates good reproducibility of the LC separation procedure. 70% of the detected features across all QC samples with coefficient variation of less than 30% indicate good stability of the MS signal (Want et al., 2010). For TIMS-TOF/MS used in our study, the mass shift within 10 ppm across all QC samples indicates good mass accuracy. Figure 3 shows the drift of retention time, peak area, and mass accuracy of a lipid feature in QC samples with the order of analysis in our study.

Figure 3.

An example of the TIMS-TOF/MS system’s stability during continuous analysis of serum extracts from Hao et al. (2021)

33 QC samples were injected throughout a series of 267 samples. PC 16:1_18:1 was chosen as an example here. (A) Variation in peak area of PC 16:1_18:2 in QC versus analysis order, expressed as percentage deviation from the mean intensity (coefficient of variation = 4.3%; n = 33. (B) Retention time drift during analyses, expressed in seconds deviation from the mean retention time (9.264 min ± 0.6 s; n = 33). (C) Variation in accurate mass measurement, in ppm deviation from the mean of accurate masses.

See troubleshooting 3, 4, 5 if the obtained data are not of good quality.

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of lipids by MS-DIAL

Timing: 1 day for ∼300 samples

Untargeted lipidomic data are processed by MS-DIAL following the guidelines of the tutorial online (https://mtbinfo-team.github.io/mtbinfo.github.io/MS-DIAL/tutorial).

-

20.

Perform post-run mass calibration for each sample using signal of the sodium formate cluster ions by the DataAnalysis software (Bruker) to improve mass accuracy.

Note: For mass calibration of a large number of samples, it is recommended to use script files for batch analysis according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

-

21.

Convert the resulting data files (.d format) to ABF format using Reifycs file converter and CompassXtract (Bruker).

Note: The size of the original .d data file is commonly 230 MB for positive ion mode and 120 MB for negative ion mode, and the resulting abf file is about 11 MB for positive ion mode and 3.5 MB for negative ion mode.

-

22.

Import the .abf files into MS-DIAL (version 4.24) for data processing including peak extraction, alignment and annotation using the parameters in Table 3.

Note: Set the retention time tolerance to 100 min and uncheck “Use retention time for scoring and filtering options” in the identification tab unless an identical LC condition is used.

-

23.

Export the alignment result including raw data matrix (Area), retention time matrix and m/z matrix.

Note: Filter the result by the ion abundances of blank samples. Replace zero values with 1/10 minimum peak height over all samples. See troubleshooting 6 for a low number of chromatographic peaks.

Note: The alignment result can be used to check retention time shifts, intensity drifts and mass accuracy of detected features in QC or all samples.

-

24.

Exclude the peak features with relative standard deviations (RSDs) of over 30% in the QC samples.

-

25.

Check and correct the annotation results of lipids manually by comparing the experimental MS/MS spectrum with reference on the graphical user interface of MS-DIAL to reduce false positive annotations.

Note: This step requires the participation of a skilled MS specialist and may take several days to complete.

Note: An ideal MS/MS spectrum for lipid identification should contain abundant diagnostic ions and few interfering ions (Figure 4A). However, the experimental MS/MS spectrum of a lipid is often contaminated by the co-elute lipids with the same m/z due to the large number of isomers in lipid species (Figure 4B). Besides, if the Δ m/z is within 2 between the interferential lipids and the target lipid, both will be isolated for acquisition of the MS/MS spectrum, which may also confuse characterization (Figure 4C). So, attention must be paid to these confusions to avoid false-negative as well as false-positive results.

Table 3.

Parameter settings for MS-DIAL

| Section | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | MS1 mass tolerance | 0.01 Da |

| MS2 mass tolerance | 0.05 Da | |

| RT begin | 2 min | |

| RT end | 17 min | |

| Mass range begin to end (MS1) | 200–1000 Da | |

| Mass range begin to end (MS2) | 100–1000 Da | |

| Number of threads | 1 | |

| Peak detection | Minimum peak height | 1000 and 700 amplitudes for positive and negative ion mode, respectively |

| Mass slice width | 0.1 Da | |

| Smoothing method | Linear weighted moving average | |

| Smoothing level | 3 scans | |

| Minimum peak width | 10 scans | |

| Adduct | Adduct ion setting | [M+H]+, [M+NH4]+, [M+Na]+ [M+H−H2O]+ for positive ion mode; [M−H]−, [M−H2O−H]−, [M+FA−H]− for negative ion mode |

| Identification | Retention time tolerance | 100 min |

| MS1 mass tolerance | 0.01 Da | |

| MS2 mass tolerance | 0.05 Da | |

| Identification score cutoff | 30% | |

| Retention time for scoring | False | |

| Retention time for filtering | False | |

| Alignment | Retention time tolerance | 0.15 min |

| MS1 mass tolerance | 0.01 Da | |

| Retention time factor | 0.5 | |

| MS1 factor | 0.5 | |

| Peak count filter | 30% | |

| N% detected in at least one group | 30% | |

| Remove features based on blank information | TRUE | |

| Sample max/blank average | 5-fold | |

| Gap filling by compulsion | TRUE |

Figure 4.

An example of MS/MS spectrum match of the experimental spectrum (black) with reference (red) from Hao et al. (2021)

(A) MS/MS spectrum of PC 32:2 (16:0_18:2) with abundant diagnostic ions and few interfering ions that were favorable for identification.

(B) MS/MS spectrum of DG 32:1 consisting of two isomers as DG 16:0_16:1 and DG 14:0_18:1 that were co-eluted on the C18 column.

(C) MS/MS spectrum of PC 36:6 (14:0_22:6) contaminated by the co-eluted PC 36:5 (18:2_18:3).

Note: For the identification of fatty acids, diagnosis ions are often not sufficiently obtained in the MS/MS spectrum. So, retention time comparison with standards is needed for structure characterization. Besides, the retention time of fatty acids on C18 is linearly related to carbon atom numbers and unsaturation degrees, which can be used as another criterion for identification.

Note: For the identification of PC and PE, identification in negative ion mode is preferred due to the informative MS/MS spectrum with high-intensity diagnosis ions of acyl chains. Besides, PC is commonly identified in the form of [M+HCOO]- in negative ion mode, while PE is commonly identified in the form of [M−H]−, thus reducing the confusion between them.

-

26.

Integrate the lipidomics data in positive and negative ion mode to generate a matrix containing lipid name and peak area information of all samples. The peak area matrix is saved to a ‘.xlsx’ file as shown in Table S1.

Note: The same lipid can be detected and identified in multiple ion forms such as [M+H]+, [M+NH4]+, [M+Na]+ (positive ion mode) or [M−H]−, [M+HCOO]− (negative ion mode). Choose one form for further analysis according to their peak intensity and reliability of MS/MS spectra match.

For more details about the use of MS-DIAL, see the online tutorial (https://mtbinfo-team.github.io/mtbinfo.github.io/MS-DIAL/tutorial).

Statistical analysis

Timing: 3 h

Statistical analysis combined with visual images can better help us to further investigate the molecular basis of diseases. Here, we use hypothesis testing combined with heatmap and differential correlation analysis combined with networking.

-

27.Construct heatmap for significant differential lipids:

-

a.Calculate the p-value of each lipid between asymptomatic and healthy groups by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

-

b.Correct p-value by Benjamini & Hochberg (BH) correction to get adjusted p-value.

-

c.Calculate log2 fold-change (log2 FC) by log2-scaling the ratio of mean peak area in asymptomatic and healthy groups for each lipid.

-

d.Select the significant differential expressed lipids which are defined using the criteria of adjusted p-value less than 0.05 and absolute log2 FC larger than 0.25.

- e.

-

a.

Note: In our previous work (Hao et al., 2021), the scripts and example data of calculating adjusted p-value and log2 FC were saved in the file named ‘FC&p-value.R’ and ‘432_lipid.csv’. The script and example data of heatmap were saved in the file named ‘heatmap.R’, ‘area_matrix.csv’ and ‘annotation.csv’. These script files and example data can be found in github (https://github.com/Chen-micslab/Covid19_TIMS/tree/main/R).

-

28.

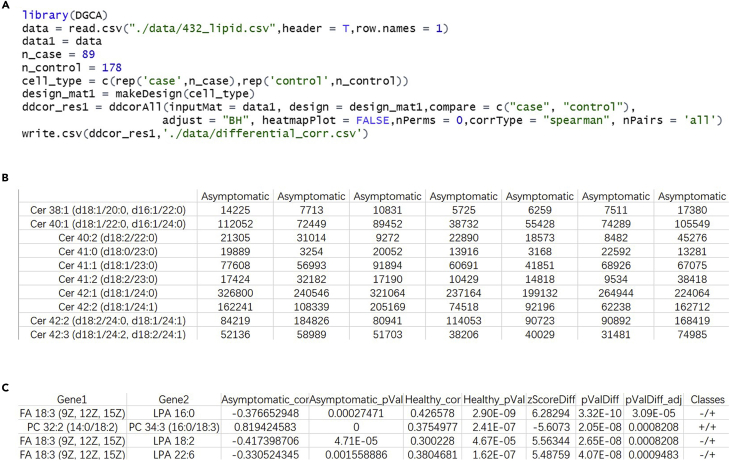

Build Networking for differential correlation:

Changes in lipid-lipid correlation patterns between disease and healthy groups may reveal pathologically related metabolic disorders.-

a.Calculate the differential correlation of lipid pairs.The number of the lipid pairs was calculated based on the number of the identified lipids (typically > 400) multiplied by the number of the subjects. The differential correlation of a lipid pair in asymptomatic and healthy groups is calculated through the package DGCA in R (Figure 6A). The input data (Figure 6B) is directly put into the function ‘ddcorAll’ in DGCA, and the ‘corrType’ is set to ‘Spearman’ and the ‘adjust’ is set to ‘BH’. All lipid pairs with adjusted P values less than 0.05 were retained. The output data is saved to a ‘.csv’ file (Figure 6C).Note: In our previous work, the scripts and example data of calculating differential correlation were saved in the file named ‘differential correlation.R’ and ‘432_lipid.csv’, and can be found in github (https://github.com/Chen-micslab/Covid19_TIMS/tree/main/R).

-

b.Visualize the networking in the Cytoscape program.

-

a.

Figure 5.

The screenshot of the R code and two input data for heatmap

(A) The screenshot of the R code.

(B) The screenshot of input data 1. The row, column and value represent lipid name, sample number and peak area.

(C) The screenshot of input data 2. Three columns represent sample type, sex and age of each sample.

Figure 6.

The screenshot of the R code, input data and output data for calculating differential correlation

(A) The screenshot of the R code.

(B) The screenshot of input data. The row and column represent lipid name and sample type. The value is peak intensity.

(C) The screenshot of output data.

The column ‘Gene1’, ‘Gene2’ and ‘Classes’ in the output data of step a are extracted and saved to a ‘.txt’ file. Click ‘‘File’’ -> ‘‘Import’’ -> ‘‘Network from file…’’ -> choose the ‘.txt’ file generated by step 28-a. Names of lipids are set as nodes and classes of lipid pairs are set as edges.

Discovery of lipid biomarkers

Timing: <1 d

The presence of hundreds of lipids would be challenging for clinical diagnosis. To improve the feasibility of detection and enhance the training speed of machine learning, it is necessary to perform feature selection to find out the lipids that are crucial for classification. Here, we developed a unique feature selection method for our untargeted lipidomics data (Figure 7).

-

29.

Calculate the average feature importance of each lipid of 100 random forest models (Svetnik et al., 2003).

Note: The feature importance is calculated based on the average variation of the feature’s Gini index. Here, all the hyperparameters of the random forest model are fixed (n_estimators are set to 100 and other parameters are the default values), except for the random_state. The feature importance is calculated respectively in 100 different random_state.

Alternatives: Other tree-based models can also be used as alternatives, such as XGBoost (Torlay et al., 2017).

-

30.

Choose the top X important lipids according to the average feature importance.

Note: In our previous work, the top 60 important lipids are selected from all 432 lipids. The number of selected top important features can be changed according to the actual situation of the experimental data.

-

31.

Divide the lipids into N sets according to their belonging subclasses.

Note: In our previous work, the top 60 important lipids are divided into 12 sets.

-

32.

Select one lipid randomly from the top 3 important lipids of each set to build a panel containing N lipids.

-

33.

Repeat step 32 until all the possible panels are generated.

-

34.

Evaluate these panels by the average accuracy of 20 repeated five-fold cross-validations in random forest models (n_estimators is set to 100 and other parameters are the default values) and choose the panel with the highest average accuracy as the initial panel.

Alternatives: The construction of the initial panel can be a time-consuming process. If your computer has limited computing power, you could change top 3 to top 2 or 1 in step 32, and you could also reduce the number of repetitions of five-fold cross-validation.

-

35.

Add remaining lipids to panel:

Figure 7.

The workflow of discovering lipid biomarkers

When the current panel containing H lipids, each of the remaining lipids in the H lipids are added into the current panel respectively to get (X – H) new panels containing (H + 1) lipids, and evaluate these panels by the average accuracy of 20 repeated five-fold cross-validations in random forest models and choose the panel with the highest average accuracy as the new panel.

-

36.

Repeat step 35 until the accuracy of all new panels is lower than the current panel. These lipids in the current panel will be the final panel for subsequent machine learning.

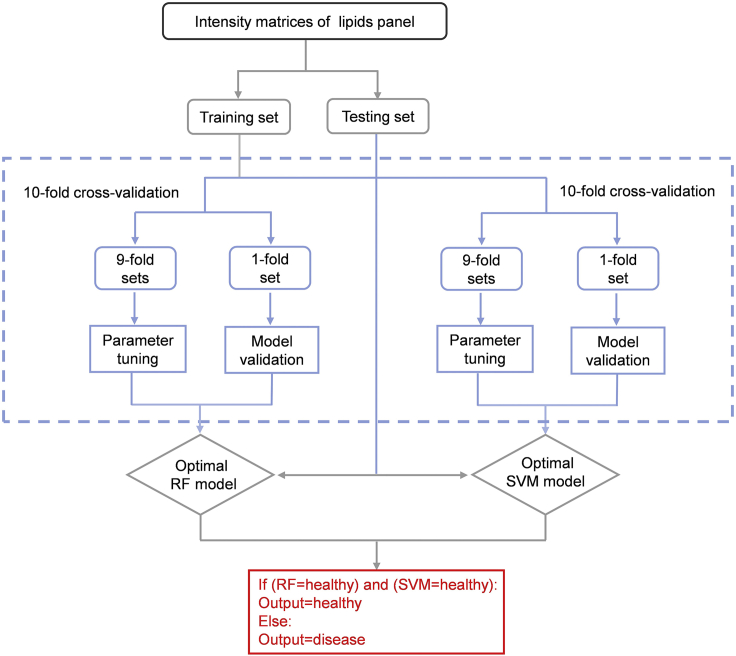

Machine learning for clinical diagnosis

Timing: ∼1 d

Considering the significant importance of sensitivity in clinical diagnosis, here, we propose an ensemble learning model based on a voting algorithm to improve sensitivity of the model. This part contains model selection, model training, model ensemble and model evaluation. To avoid wasting much computing time, we recommend that your computer should be equipped with at least 2.4 GHz CPU Clock Speed and at least 8 G memory. In our previous work, machine learning codes are all based on Python and the package ‘Scikit-learn’.

-

37.

Divide data set randomly into training set and testing set.

CRITICAL: The testing set cannot be used in any process of model training.

Note: In clinical diagnosis, it will be better if you can get another independent cohort collected at different times or areas as the testing set. In our previous work, we did not have anindependent cohort. We used five-fold cross-validation which means the testing set contains 20% of the whole data set.

-

38.

List candidate models, such as SVM (Support vector machine) (Cortes and Vapnik, 1995), RF (random forest), LG (logistic regression) (Pregibon, 1981), MLP (multi-layer perceptron) (Gardner and Dorling, 1998).

-

39.

Select models by nested cross-validation (Krstajic et al., 2014):

For subsequent ensemble learning, two models that perform best on our data need to be selected from the candidate models. Here, nested cross-validation is used to optimize parameters and measure performance of each model (Figure 8).-

a.Divide the training set into five-fold.

-

b.Using each one-fold as the testing set of the outer loop and the other four-fold as the inner loop.

-

c.Optimize the parameters of each model in the inner loop by the average accuracy of 10 repeated ten-fold cross validation.

-

d.Evaluate the performance of each model’s optimized parameters on the testing set of the outer loop by accuracy.

-

e.Repeat step a, b, c, d 20 times with different random states of step a in each time.

-

f.Calculate the average accuracy of each model in step e.

-

g.Select two models with highest average accuracy.Notes: Different models have different parameters, such as the gamma and C of SVM, the hidden_layer_sizes of MLP. The parameters of each model are optimized by grid search, for example, in SVM, C = [0.5, 5, 50, 500], gamma = [0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5], the best group of parameters which could get the highest average accuracy in the 10 repeated ten-fold cross-validation will be selected from 20 random combinations of two parameters.Alternatives: The repeated k-fold cross-validation is not fixed. You can choose an appropriate k-fold based on your data, and we recommend more than 4-fold and at least ten repetitions.Alternatives: Here we choose two models to construct an ensemble model. In your experiment, you could try more models to find out the most suitable number of models.

-

a.

Figure 8.

The diagram of nested cross-validation

See troubleshooting 7 for the poor performance of individual models.

-

40.

Train model by 20 repeated ten-fold cross-validation based on training set:

Notes: Grid search is used to select the best group of parameters for each model.

Alternatives: The 20 repeated ten-fold cross-validation used in the inner loop is also not fixed. You can choose k-fold based on your data, and we recommend more than ten repetitions.

-

41.

Model ensemble:

The method of ensemble learning used here is based on the stacking method (Li et al., 2019). We replace the meta-learner of the stacking method with a voting algorithm. The algorithm follows the rule below:

If (model_1 = healthy) and (model_2 = healthy):

Ensemble_output = healthy

Else:

Ensemble_output = disease

A sample will be predicted as healthy by the ensemble model only when the outputs of the two models are healthy. If the output of one model is disease, the final output of the ensemble model will be disease.

Figure 9 shows the workflow of model training and model ensemble.

Alternatives: Here we choose two models to construct an ensemble model. In your experiment, you can try more models to find out the most suitable number of models. You can also design other voting algorithms according to your task requirements.

-

42.

Evaluate model on testing set:

The final ensemble model will be tested on the testing set which was not used in any previous step. These indicators are used to evaluate the performance of the model: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, ROC curve and PR curve. All these indicators could be calculated from the confusion matrix (Figure 10A). For the binary classification model, the confusion matrix is composed of TP (true positive), TN (true negative), FP (false positive) and FN (false negative).-

a.

-

b.

-

c.(Figure 10B) shows an example of the three results adopted from our previous study for the diagnosis of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients (Hao et al., 2021).

-

d.ROC curve:The abscissa of the ROC curve represents (1-specificity) and the ordinate represents sensitivity. Each point on the ROC curve is the sensitivity and (1-specificity) of the model on different classification cutoff values (Figure 10C).Note: In our previous work, we used the default cutoff of each model in scikit-learn. Readers can also set the cutoff value according to their own situation.

-

e.PR curve:The abscissa of the PR curve represents recall (equal to sensitivity) and the ordinate represents precision . Each point on the PR curve is the recall and precision of the model on different classification cutoff values (Figure 10D).

-

a.

Figure 9.

The workflow of model training and model ensemble

Figure 10.

An example of models’ indicators from Hao et al. (2021)

(A) The confusion matrix.

(B) Accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of individual models and the ensemble model.

(C) ROC curve of ensemble model.

(D) PR curve of ensemble model.

Expected outcomes

In our protocol, take the analysis of 267 serum samples collected from healthy controls and COVID-19 patients as an example (Hao et al., 2021), 1800 and 781 features were detected in positive and negative ion mode, respectively. After excluding features with RSDs > 30%, 432 lipids including 19 subclasses were finally identified and relatively quantified (Table S1). By statistical analysis of the obtained area matrix, the disease-related differential lipids can be found out, and disease-related lipids dysregulation can be revealed. In our study, a total of 124 lipids were found to be differentially expressed (Table S2). Among them, 41 lipids were up-regulated, which mainly include phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine and diacylglycerols. While 83 lipids were found to be down-regulated, which mainly include lysophospholipids, ether lipids, sphingomyelins and fatty acids. Machine learning was further applied for the discovery of biomarkers and to investigate the potential of serum lipids for clinical diagnosis.

Limitations

The ethanol extraction used in our study was not suitable for some highly hydrophobic lipids such as triacylglycerol, as mentioned in “sample preparation for LC-MS analysis” section. Although all the samples can be analyzed at one time without compromised performance of the LC-MS system, the analysis strategy may need to be adjusted for studies of larger sample sizes. It may be necessary to inject samples in batches. Cleaning and maintenance of the LC-MS system may be needed between batches to keep the instrument in good condition. Readers can refer to (Dunn et al., 2011) for suggestions for long-term and large-scale omic studies.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

High back pressure of the system. (Step 15)

Potential solution

There may be a blockage in the injection system, pipelines or column of the UPLC system, or in the electrospray needle of the MS system. Find out the blockage site step-by-step. For example, we can confirm whether the LC column was blocked by comparing the system pressure with and without installing a LC column. First, try to rinse the blockage site with solvents of different polarities. The electrospray needle or sampling needle can also be washed by ultrasonic with 50% MeOH followed by MeOH. If these don’t work, replace the pipelines, sampling or electrospray needles or LC column that was blocked with a spare one.

Problem 2

High background noise in blank samples. (Step 19)

Potential solution

Re-prepare the mobile phase, rinse the HPLC system, and wash the MS ion source. If these don’t work, replace the pipelines, sampling or electrospray needles or LC column.

Problem 3

Poor chromatographic peak shape, reduced chromatographic resolution or shifted retention times. (Step 19)

Potential solution

This is usually caused by column contamination or degradation and can be confirmed by analysis of standards. Replace the column with a new one.

Problem 4

Gradual sensitivity decreases. (Step 19)

Potential solution

This is usually caused by contamination of the ion source. Wash the electrospray needle, spray shield and capillary cap of the ion source by ultrasonic with 50% MeOH followed by MeOH. Wipe the spray chamber with 50% MeOH followed by MeOH. If this doesn’t work, contact the engineer of manufacturer for suggestions.

If the remaining samples are not enough for reanalysis, perform signal correction based on QC using different algorithms, such as LOESS (Dunn et al., 2011), or MetNormalizer (Shen et al., 2016).

Problem 5

Precision mass shifts. (Step 19)

Potential solution

Recalibrate the MS system using the sodium formate solution.

Problem 6

Low number of chromatographic peaks or identified lipids. (Step 23)

Potential solution

Increase the injection volume, lower the threshold of peak intensity for peak extraction, and use all samples instead of QC for lipid identification.

Problem 7

Poor performance of individual models. (Step 39)

Problem solution

Before being imported to the model, the peak area matrix should be preprocessed using different methods. Here, Zero-mean normalization coupled with PCA (n_components = 0.99) is used for SVM. Without normalization, the performance of SVM would be so bad. Single zero-mean normalization is used for MLP and LR. RF uses the original peak area matrix without preprocessing. For different data, the preprocessing methods of each model are not fixed, you can test different methods to find out which is suitable for your model. If your model’s performance is very poor, pay attention to whether there is no data preprocessing or the data processing method is inappropriate.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact Suming Chen (sm.chen@whu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC2700700) and National Science Foundation of China (22074111, 22004093, 22004092). We also thank the support of the start-up funds of Wuhan University and the National Youth Talents Plan of China." by the start-up funds of Wuhan University and the National Youth Talents Plan of China.

Author contributions

M.R.C. and Y.H.H. organized the protocol design. Y.H.H. wrote the sample preparation, LC-MS analysis and MS-DIAL analysis protocol. M.R.C. wrote the statistical analysis and machine learning protocol. S.M.C. revised the whole protocol and supervised the overall research.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101125.

Contributor Information

Moran Chen, Email: mr_chen@whu.edu.cn.

Suming Chen, Email: sm.chen@whu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The lipidomics data are deposited in ProteomeXchange Consortium: PXD024410. https://www.iprox.org/ The project data analysis codes are deposited in GitHub: https://github.com/Chen-micslab/Covid19_TIMS.

References

- Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C., Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995;20:273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W.B., Broadhurst D., Begley P., Zelena E., Francis-McIntyre S., Anderson N., Brown M., Knowles J.D., Halsall A., Haselden J.N., et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:1060–1083. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M.W., Dorling S.R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—a review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 1998;32:2627–2636. [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Zhang Z., Feng G., Chen M., Wan Q., Lin J., Wu L., Nie W., Chen S. Distinct lipid metabolic dysregulation in asymptomatic COVID-19. iScience. 2021;24:102974. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstajic D., Buturovic L.J., Leahy D.E., Thomas S. Cross-validation pitfalls when selecting and assessing regression and classification models. J. Cheminform. 2014;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Miao W., Cui J., Fang C., Su S., Li H., Hu L., Lu Y., Chen G. Efficient corrections for DFT noncovalent interactions based on ensemble learning models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019;59:1849–1857. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyash V., Liebisch G., Kurzchalia T.V., Shevchenko A., Schwudke D. Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:1137–1146. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D700041-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregibon D. Logistic regression diagnostics. Ann. Statist. 1981;9:705–724. [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Gong X., Cai Y., Guo Y., Tu J., Li H., Zhang T., Wang J., Xue F., Zhu Z.-J. Normalization and integration of large-scale metabolomics data using support vector regression. Metabolomics. 2016;12:89. [Google Scholar]

- Svetnik V., Liaw A., Tong C., Culberson J.C., Sheridan R.P., Feuston B.P. Random forest: a classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43:1947–1958. doi: 10.1021/ci034160g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torlay L., Perrone-Bertolotti M., Thomas E., Baciu M. Machine learning–XGBoost analysis of language networks to classify patients with epilepsy. Brain Inf. 2017;4:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s40708-017-0065-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H., Ikeda K., Takahashi M., Satoh A., Mori Y., Uchino H., Okahashi N., Yamada Y., Tada I., Bonini P., et al. A lipidome atlas in MS-DIAL 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1159–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang C., Han X. Selection of internal standards for accurate quantification of complex lipid species in biological extracts by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry-What, how and why? Mass Spec. Rev. 2017;36:693–714. doi: 10.1002/mas.21492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Want E.J., Wilson I.D., Gika H., Theodoridis G., Plumb R.S., Shockcor J., Holmes E., Nicholson J.K. Global metabolic profiling procedures for urine using UPLC–MS. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:1005–1018. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P., Lehmann R., Xu G. Effects of pre-analytical processes on blood samples used in metabolomics studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:4879–4892. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8565-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelena E., Dunn W.B., Broadhurst D., Francis-McIntyre S., Carroll K.M., Begley P., O’Hagan S., Knowles J.D., Halsall A., HUSERMET Consortium. Wilson I.D., Kell D.B. Development of a robust and repeatable UPLC−MS method for the long-term metabolomic study of human serum. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:1357–1364. doi: 10.1021/ac8019366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The lipidomics data are deposited in ProteomeXchange Consortium: PXD024410. https://www.iprox.org/ The project data analysis codes are deposited in GitHub: https://github.com/Chen-micslab/Covid19_TIMS.