Abstract

Objectives: Clinical empathy is an important predictor of patient outcomes. Several factors affect physician’s empathy and client perceptions. We aimed to assess the association between physician and client perception of clinical empathy, accounting for client, physician, and health system factors. Methods: We conducted a hospital-based cross-sectional study in 3 departments (family medicine, internal medicine, and surgery) of King Saud Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We interviewed 30 physicians and 390 clients from 3 departments. Physicians completed the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) and the clients responded to the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy (JSPPPE). We used a hierarchical multilevel generalized structural equation approach to model factors associated with JSE and JSPPPE and their inter-relationship. Results: Mean (SD) score of client-rated physician empathy was 26.6 (6) and that of physician self-rated was 111 (12.8). We found no association between the 2 (b = 0.06; 95% confidence intervals CI: −0.1, 0.21), even after adjusting for client, physician, and health system factors. Physician's nationality (0.49; 0.12, 0.85), adequate consultation time (1.05; 0.72, 1.38), and trust (1.33; 0.9, 1.75) were positively associated whereas chronic disease (−0.32; −0.56, −0.07) and higher waiting times (−0.26; −0.47, −0.05) were negatively associated. Conclusion: A physician's self-assessed empathy does not correlate with clients’ perception. We recommend training and monitoring to enhance clinical empathy.

Keywords: clinical empathy, physician–patient relations, determinants, structural equation modeling

Introduction

Empathy, compassion, and communication skills are closely related to physician characteristics that have been shown to positively impact patient-centered outcomes (1–5). Physicians themselves also benefit from being empathetic. Empathetic physicians seem to perceive better patient outcomes and practices (6). Empathy in physicians also reduces the likelihood of litigations and violence on doctors (7).

Although empathy has a place in all areas of clinical practice, clinical empathy is especially important for conditions like chronic pain, where medications have a ceiling effect and the patient's overall quality of life becomes a major outcome (8). In developed countries where elderly citizens constitute a significant proportion of the population and suffer from a high burden of non-communicable diseases including joint pain and low backache, empathetic clinical practice becomes even more important (9).

While the case for increasing empathetic clinical practice is being argued, on the one hand, a general decline in empathetic practice has also been noted (10). With the modernization of medicine, the dynamics of a physician–patient relationship have become more impersonal and mechanized. Apart from adversely affecting patient outcomes, higher physician burnout has also been found to be a consequence of an inability to show care (11).

Physicians’ expression of empathy, its perception by clients, and the correlation between them are affected by socio-demographic background, language and culture, physician experiences, client experiences, and health-system related factors. These complicated inter-relationships are difficult to explain using common statistical methods. Studies that have explored the relationship between expression and perception of empathy in clinical encounters have not considered all associated factors (client, physician, and health system-related factors) in one comprehensive framework (12–14). In such situations, an advanced analytical framework like generalized structural equation modeling can prove useful.

Therefore, we carried out this study to determine the association between client and physician perception of clinical empathy during clinical encounters while adjusting for client, physician, and health system level characteristics in a tertiary care hospital setting.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a hospital-based cross-sectional study in 3 departments (family medicine, internal medicine, and surgery) of King Saud Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from 2018 to 2019. Physicians of any gender and nationality, who were employed in the hospital for >1 year and currently involved in out-patient clinics were eligible. Ten physicians were selected randomly from each department using a sampling frame of all eligible physicians. Physicians’ self-perception of their empathy was measured using the self-administered Health Professions (HP) version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) in a bilingual form (English and Arabic).

Adult clients (≥ 18 years) who attended the selected out-patient clinics were eligible to participate. The sample size was calculated with the following assumptions: standard deviation (SD) of 2.5, a confidence level of 95%, an acceptable error of 2, and a nonresponse rate of 20%, and design effect of 1.5 giving us the final sample size of 390 (13 patients interviewed for every physician). These patients were enrolled in a consecutive manner outside each physician's clinic (exit interview) till the required size was achieved. Patients were approached as they exited the clinic and asked to participate, and their eligibility was checked by the study staff. After the objectives of the study were explained to the patients, written informed consent was obtained from them, and they were then asked to complete the self-administered questionnaire. Clients (13 per physician) were recruited in a consecutive manner from within the 30 physicians’ clinics.

To measure client's perception of their physician's empathy, the Arabic version of the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy (JSPPPE) questionnaire was used. Clients were approached and asked to participate in the study as they exited the clinics and they completed the self-administered study questionnaire. Both JSE and JSPPPE have been translated according to the guidelines of the original author and validated in previous studies. Neither the physicians nor their clients were explicitly told about the involvement of the other in the study. Data from the clients and their respective physicians were collected within 2 days of each other.

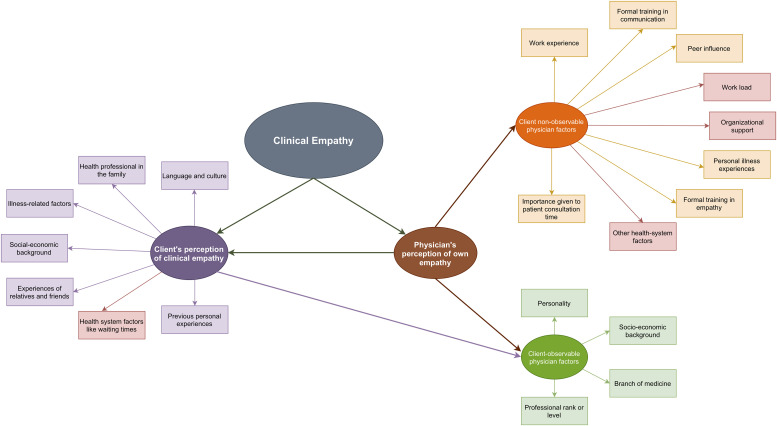

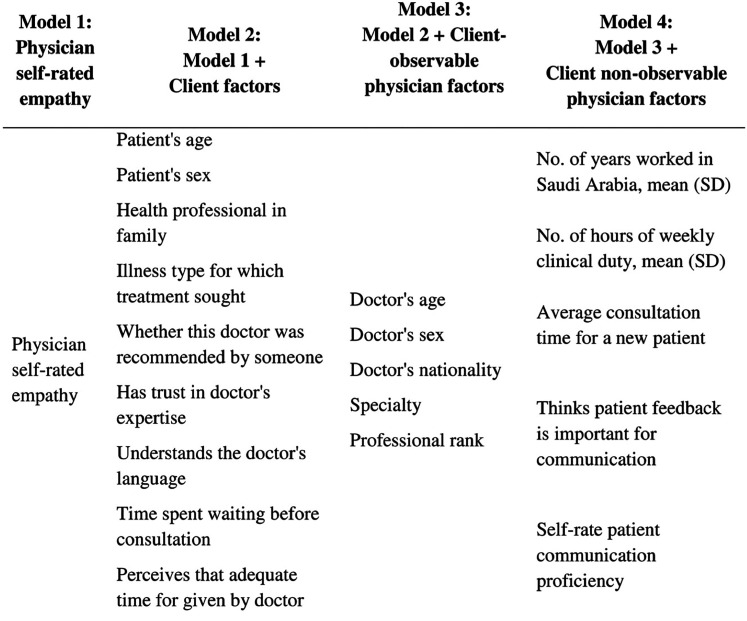

The theoretical framework that guided the study hypotheses and data collection (socio-demographic details, illness-related information, and health system factors, among others) is presented in Figure 1. The framework provides a visualization of the plethora of potential factors that influence clinical empathy (the true empathy) during a clinical encounter. Physician as the provider of clinical service exudes empathy via verbal and non-verbal means which is then captured and assimilated by the client. The client's version of this empathy is modified by his/her background, illness, peers, cultural milieu, past experiences, health system, and certain observable physician traits such as age, sex, department, and professional rank. The physician also has a self-assessment of his/her own empathy, which is modified by factors such as socio-demographic background, work, personal experiences, training, patient characteristics, and health system. The factors have been added in the model at each step under the labels - physician self-rated empathy score, client factors (factors related to the client characteristics), client-observable physician factors (those physician-related characteristics which can be easily judged by the client), and client non-observable physician factors (those physician-related characteristics that are in apparent to the client) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the factors affecting client and physician self-perception of physician empathy during physician–client interactions.

Figure 2.

List of models and variables added at each step of the hierarchical model for the association between client-rated and self-rated physician empathy.

Data were captured electronically using Epicollect 5 (Imperial College, London, UK) and analyzed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive analysis was performed - all categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages and all quantitative variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD). Association between client and physician scores was explored using a hierarchical multilevel structural equation modeling (SEM) framework. Clustering of clients within the physicians was handled by performing a multilevel analysis and to verify the theoretical framework, the model was built in a hierarchical fashion with sets of variables entered at each step—model 1 had physician self-rated empathy score, model 2 had model 1 plus client factors, model 3 had model 2 plus client-observable physician factors, and finally, model 4 included model 3 plus client non-observable physician factors (Figure 2). The client level characteristics were selected based on a previous generalized mixed-effects linear regression exercise (15), whereas the physician level characteristics were selected based on theory/literature review. The number of factors in the overall model was dictated by the sample size requirements and the model convergence potential.

Model performance was assessed by means of log-likelihood values, likelihood ratio tests, and information criteria statistics. A P value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Client Profile

A total of 30 physicians and 390 clients (13 per physician) participated in this study. Among the clients, 51.5% were females and 48.5% were males and they had a mean (SD) age of 40.5 (13.6) years. A vast majority had visited the hospital for a consultation about their chronic illness (82.1%). The mean (SD) score given by the clients to their consulting physicians using the JSPPPE (max possible score was 35) was 26.6 (6.0) (Table 1). The majority reported that they trusted the doctor's expertise (96.2%), understood the doctor's language (96.7%), and got adequate time for consultation (93.8%).

Table 1.

Background Characteristics of the Clients (n = 390) and Their Physicians (n = 30).

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Client factors | |||

| Client's age, mean (SD) | 40.5 | 13.6 | |

| Client's sex | Female | 201 | 51.5% |

| Male | 189 | 48.5% | |

| Health professional in family | No | 288 | 73.8% |

| Yes | 102 | 26.2% | |

| Illness type for which treatment sought | Acute disease | 70 | 17.9% |

| Chronic disease | 320 | 82.1% | |

| Whether this doctor was recommended by someone | No | 347 | 89.0% |

| Yes | 43 | 11.0% | |

| Has trust in doctor's expertise | No | 15 | 3.8% |

| Yes | 375 | 96.2% | |

| Understands the doctor's language | No | 13 | 3.3% |

| Yes | 377 | 96.7% | |

| Time spent waiting before consultation | <10 min | 128 | 32.8% |

| 10-30 min | 152 | 39.0% | |

| >30 min | 110 | 28.2% | |

| Perceives that adequate time was given by doctor | No | 24 | 6.2% |

| Yes | 366 | 93.8% | |

| Client's rating of physician empathy, mean (SD) | 26.6 | 6.0 | |

| Physician factors | |||

| Physician's age, mean (SD) | 40.9 | 10.5 | |

| Physician's sex | Female | 9 | 30.0% |

| Male | 21 | 70.0% | |

| Physician's nationality | Expat | 12 | 40.0% |

| Native | 18 | 60.0% | |

| Specialty | Family medicine | 10 | 33.3% |

| Internal medicine | 10 | 33.3% | |

| Surgery | 10 | 33.3% | |

| Professional rank | GP or below | 12 | 40.0% |

| Registrar or above | 18 | 60.0% | |

| No. of years worked in Saudi Arabia, mean (SD) | 11.3 | 8.8 | |

| No. of hours of weekly clinical duty, mean (SD) | 37.2 | 15.7 | |

| Average consultation time for a new patient, mean (SD) | 14.7 | 4.0 | |

| Thinks patient feedback is important for communication | No | 14 | 46.7% |

| Yes | 16 | 53.3% | |

| Self-rated patient communication proficiency | Basic or intermediate | 11 | 36.6% |

| Advanced or expert | 19 | 63.4% | |

| Self-rated physician empathy, mean (SD) | 111.0 | 12.8 | |

Physician Profile

Mean (SD) age of the physicians was 40.9 (10.5) years with 70% being males and 60% being native of Saudi Arabia. Their mean (SD) work experience in Saudi Arabia was 11.3 (8.8) years. They had an average of 37.2 weekly duty hours and spent a mean (SD) of 14.7 (4.0) min for new client consultation. The mean (SD) self-rated empathy score using the JSE (max possible score was 210) was 111.0 (12.8) (Table 1). Slightly more than half considered patient feedback to be important for communication and 63.4% thought that they had advanced or expert level proficiency in communication skills.

Client Factors Associated With Perceived Empathy

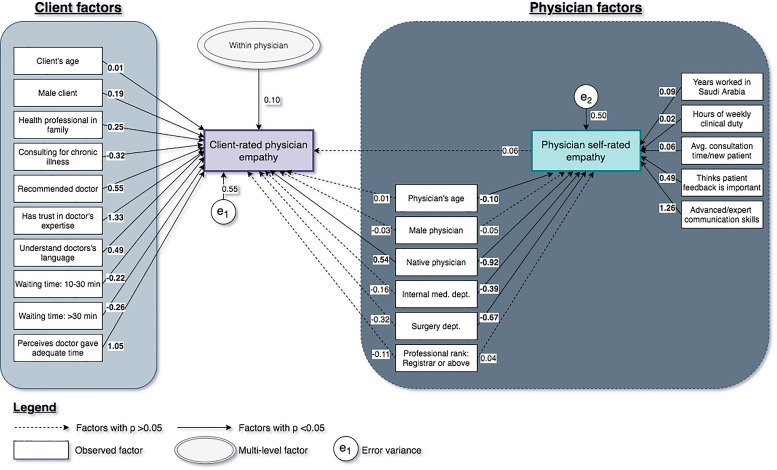

All the investigated client factors were significantly associated with client-rated scores across models 2 to 4. Higher age (b = 0.01; 95% CI: 0, 0.01), male sex (0.19; 0.03, 0.35), and having a health professional in the family (0.25; 0.07, 0.43) were positively associated with higher client scores but the strongest and most significant positive associations were seen for “physician being recommended by friends/relatives” (0.55; 0.29, 0.81), “having trust is the doctor's expertise” (1.33; 0.9, 1.75), “perceiving that the doctor gave adequate time” (1.05; 0.72, 1.38). Clients consulting for chronic diseases (−0.32; −0.56, −0.07) and those who waited longer (−0.26; −0.47, −0.05) gave lower scores (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Table 2.

Client and Physician Level Predictors of Client-Rated Empathy Score of Physicians—Hierarchical Multilevel Generalized Structural Equation Modeling.

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 CI) | Model 4 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician self-rated empathy | 0.03 (−0.15, 0.21) | 0.06 (−0.1, 0.22) | 0.06 (−0.1, 0.21) | 0.06 (−0.1, 0.21) |

| Client factors | ||||

| Patient's age | 0.01 (0, 0.01)** | 0.01 (0, 0.01)** | 0.01 (0, 0.01)** | |

| Patient's sex: male | 0.17 (0.01, 0.33)* | 0.19 (0.03, 0.35)* | 0.19 (0.03, 0.35)* | |

| Health professional in family | 0.24 (0.07, 0.42)** | 0.25 (0.07, 0.43)** | 0.25 (0.07, 0.43)** | |

| Illness type for which treatment sought | ||||

| Acute disease | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Chronic disease | −0.29 (−0.53, −0.06)* | −0.32 (−0.56, −0.07)* | −0.32 (-0.56, −0.07)* | |

| Whether this doctor was recommended by someone | 0.55 (0.3, 0.81)*** | 0.55 (0.29, 0.81)*** | 0.55 (0.29, 0.81)*** | |

| Has trust in doctor's expertise | 1.35 (0.93, 1.78)*** | 1.33 (0.9, 1.75)*** | 1.33 (0.9, 1.75)*** | |

| Understands the doctor's language | 0.48 (0.04, 0.91)* | 0.49 (0.06, 0.92)* | 0.49 (0.06, 0.92)* | |

| Time spent waiting before consultation | ||||

| <10 min | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 10-30 min | −0.22 (−0.41, −0.04)* | −0.23 (−0.41, −0.04)* | −0.23 (−0.41, −0.04)* | |

| >30 min | −0.28 (−0.49, −0.07)** | −0.26 (−0.47, −0.05)* | −0.26 (−0.47, −0.05)* | |

| Perceives that adequate time for given by doctor | 1.04 (0.7, 1.37)*** | 1.05 (0.72, 1.38)*** | 1.05 (0.72, 1.38)*** | |

| Client-observable physician factors: direct effects | ||||

| Doctor's age | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | ||

| Doctor's sex: male | −0.03 (−0.42, 0.36) | −0.03 (−0.42, 0.36) | ||

| Doctor's nationality | ||||

| Expat | 1 | 1 | ||

| Native | 0.54 (0.19, 0.89)** | 0.54 (0.19, 0.89)** | ||

| Specialty | ||||

| Family medicine | 1 | 1 | ||

| Internal medicine | −0.16 (−0.55, 0.23) | −0.16 (−0.55, 0.23) | ||

| Surgery | −0.32 (−0.76, 0.13) | −0.32 (−0.76, 0.13) | ||

| Professional rank | ||||

| GP or below | 1 | 1 | ||

| Registrar or above | −0.11 (−0.46, 0.23) | −0.11 (−0.46, 0.23) | ||

| Client-observable physician factors: indirect effects | ||||

| Doctor's age | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | −0.1 (−0.13, −0.07)*** | ||

| Doctor's sex: male | −0.05 (−0.29, 0.2) | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | ||

| Doctor's nationality | ||||

| Expat | 1 | 1 | ||

| Native | −0.19 (−0.41, 0.03) | −0.92 (−1.19, −0.64)*** | ||

| Specialty | ||||

| Family medicine | ||||

| Internal medicine | −0.55 (−0.79, −0.31)*** | −0.39 (−0.62, −0.16)** | ||

| Surgery | −0.96 (−1.23, −0.7)*** | −0.67 (−0.89, −0.44)*** | ||

| Professional rank | ||||

| GP or below | 1 | 1 | ||

| Registrar or above | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.13)** | 0.04 (−0.18, 0.26) | ||

| Client-observable physician factors: total effects | ||||

| Doctor's age | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | ||

| Doctor's sex: male | −0.03 (−0.42, 0.35) | −0.03 (−0.42, 0.35) | ||

| Doctor's nationality | ||||

| Expat | 1 | 1 | ||

| Native | 0.53 (0.18, 0.88)** | 0.49 (0.12, 0.85)** | ||

| Specialty | ||||

| Family medicine | 1 | 1 | ||

| Internal medicine | −0.19 (−0.57, 0.19) | −0.18 (−0.57, 0.2) | ||

| Surgery | −0.37 (−0.79, 0.05) | −0.36 (−0.78, 0.07) | ||

| Professional rank | ||||

| GP or below | 1 | 1 | ||

| Registrar or above | −0.13 (−0.47, 0.21) | −0.11 (−0.46, 0.24) | ||

| Client non-observable physician factors | ||||

| No. of years worked in Saudi Arabia, mean (SD) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.12)*** | |||

| No. of hours of weekly clinical duty, mean (SD) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.02)*** | |||

| Average consultation time for a new patient | 0.06 (0.04, 0.09)*** | |||

| Thinks patient feedback is important for communication | 0.49 (0.29, 0.69)*** | |||

| Self-rate patient communication proficiency | ||||

| Basic or intermediate | 1 | |||

| Advanced or expert | 1.26 (1.04, 1.48)*** | |||

| Log Likelihood | −532.7 | −457.5 | −950.6 | −872.9 |

| AIC | 1073.4 | 943.1 | 1957.2 | 1811.9 |

| BIC | 1089.2 | 998.6 | 2068.2 | 1942.8 |

| LR test | chi = 150.3, P <.001 | chi = 155.2, P < .001 | ||

Note: model 1—physician self-rated score only, model 2—model 1 + client factors, model 3—model 2 + physician-level, directly and indirectly, acting factors, model 4—model 3 + physician-level only indirectly acting factors; p value * 0.05 - 0.01, ** 0.01 - 0.001, *** < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Multilevel generalized structural equation model for the association between client-rated and self-rated physician empathy.

Physician Factors Associated With Self-Assessed Empathy

Among the physician factors, age and sex had no influence. Internal medicine and surgery departments were negatively associated with self-rated scores only but did not influence client scores. Native physicians rated themselves poorer than expats after adjusting for work experience and work-load but higher scores were assigned by clients to them regardless of work experience and work-load. Higher-ranked physicians rated themselves lower but this association disappeared after adjusting for work experience and work-load. Rank was not associated with client scores, directly or via physician scores. Among physician-level indirect factors, “importance given to patient feedback” and “higher self-rated proficiency in communication” were strongly associated with self-rated empathy (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Self-Assessed Empathy Versus Client Perception

The hierarchical multilevel SEM modeling revealed that the standardized client-rated scores were not associated with physician self-rated standardized scores even after adjusting for all possible client-level and physician-level factors (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Model Performance

Among models where only one dependent variable (client-rated empathy) was assessed, model 2 performed better than model 1 (LR-test chi-square 150.3, P < .001). In models where 2 dependent variables were assessed (client- and physician-rated empathy) final model 4 performed better than model 3 as denoted by a significant likelihood ratio test (chi-square = 155.2, P < .001) and lower AIC (1811.9 vs 1957.2) and BIC values (1942.8 vs 2068.2).

Discussion

Empathy is a complex psychosocial construct that requires a nuanced analytical approach to understand the inter-relationships among a multitude of factors. This comprehensive examination of factors affecting clinical empathy that transpires during a client-physician encounter using a multilevel generalized structural equation modeling approach has given several other important insights. Our hospital-based cross-sectional study of 390 clients consulting with 30 physicians revealed a lack of association between physicians’ self-assessment and clients’ perception of empathy in clinical encounters.

Lack of correlation between physician and client rating of empathy: The lack of correlation between physician and client rating of empathy was also reported in previous studies which had used different scales (such as Toronto Composite Empathy Scale, Consultation and Relational Empathy) to measure empathy (14,16). Although, one particular study found an inverse relationship between empathy rated by internal medicine physicians and their patients (12). Surprisingly, the correlation did not turn significant even after accounting for a host of other plausible factors. A number of reasons may be at play here. Firstly, physicians who are really empathetic might rate themselves lower on account of being humbler (13) leading to an inverse or weaker relation. Secondly, the apparent lack of a correlation could be due to variations in the emotional skills of clients. In a study among cancer patients, it was found that in regular follow-up consultations, patients with high emotional skills did not benefit from physician empathy unlike patients with low emotional skills (17). Thirdly, it might be explained by the physician's inability to fulfil the patient's unmet need for supportive care, even though they might be empathetic as such (18).

Physician factors: It is expected that physician characteristics such as age, sex, rank, and department which are observable by the client will influence the perceived empathy. However, we found that only physician nationality was associated with client scores directly or indirectly via physician self-rated scores. A native physician was perceived as being more empathetic as compared to an expat physician, adjusting for background characters. It stands to reason that clients would connect more to a physician who represents their own culture and language and perceive greater empathy (19). Evidence shows that female physicians are in general more empathetic and are perceived as being more empathetic by clients (14,20). Although the same was found in this study, the relationship was not statistically significant. Older, more experienced physicians and those who have more patient interactions were found to rate themselves higher in the current and previous studies (21,22). Also, we confirmed previous findings that physicians who spend more time during consultation also rated themselves higher on the empathy scale (23,24). With more experience and interaction, physicians gain a certain insight that allows them to look into illness more holistically. For an experienced physician, the burden of diagnosis is lesser and as a result, they tend to focus more on the human element. Also, senior physicians attend fewer patients that require special attention as compared to younger colleagues who see more patients per capita. The specialty has an important effect on physician empathy (25). In the current study, the surgery department had lower empathy than nonsurgical departments, as was confirmed by previous studies (14,26). Specialty embodies a lot of factors like workstyle, free time, workload, night-calls, duty hours, theatre duties, peer influence, the closeness of interaction with patients, and level of job satisfaction. These factors play out to varying degrees in deciding whether clinical empathy is desired or not. Among the client nonobservable physician factors, physicians who thought patient feedback was important and rated themselves higher on communication also tended to consider themselves more empathetic. Being open to constructive client feedback and having good communication skills enable the physician to interact with clients with a broader mindset and listen more intently to the clients, which are elements of the physician’s empathy (27).

Client factors: Perceived empathy was strongly influenced by the client's trust in doctor, the doctor being recommended by a friend/relative, and understanding the doctor's language. These are factors that come into play before the client begins the consultation. Therefore, it would seem that a lot of the decision about the physician's empathy happens pre-consultation. It also seems that a halo effect may be in play, where the client decides a priori that the physician must be good and overlooks shortcomings (28). As described above, a common language increases the conductivity of empathy in client–physician interactions.

Health system factors: System-level factors that are beyond the control of the physician or client, but nevertheless influence the clinical encounter, such as waiting times, time available for consultation, recruitment of experienced physicians, and physician weekly duty hours were also found to influence perceived empathy (19,29). Unsurprisingly, we found that higher waiting times were associated with lower perceived empathy by the clients. Other health system factors such as duty hours of physicians, workload, and recruitment of experienced physicians were weakly associated with physician self-assessment.

Empathy-Satisfaction-Outcomes cycle: A cycle of benefits for the client, physician, and health system is likely to operate, starting with an empathetic physician. Perceiving the physician to be empathetic is a major component of client satisfaction (25,30,31). Clients may give less importance to poor system-related factors such as waiting times or lack of facilities available if they perceive the physicians to be empathetic towards them. In that way, it is important for a healthcare manager to train physicians on providing an empathetic clinical experience for the clients. This can be seen as a short-term intervention to improve overall client satisfaction until major structural changes to the system can take effect. This client satisfaction will lead to better treatment compliance and higher retention rates, which in turn will improve treatment outcomes and lead to further client satisfaction.

On the other side of the equation, physicians also stand to benefit from being empathetic in terms of better job satisfaction, lesser emotional exhaustion, lesser depersonalization, and higher personal accomplishment from seeing their clients maintaining good compliance, achieving better outcomes, getting recommended to other clients and getting good ratings via feedback channels (32). Such satisfied physicians will tend to display higher empathy in clinical encounters, leading to further client satisfaction (6). Health systems, also tend to benefit from satisfied physicians who stay longer with the current employer reducing staff turnover, and from satisfied clients who tend to recommend the facility to relatives and friends.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has explored client, physician, and health system-level factors for physician empathy in one comprehensive analytical framework. The cluster design of the study enabled us to correlate the client's rating with the actual physician who they consulted by using a multilevel model. In addition to confirming that apparent lack of correlation between client and physician rating of empathy, we have explored many possible factors that could explain the phenomenon using an SEM framework, which has been sparingly done previously.

A few limitations have to be borne in mind while interpreting the results. The findings are applicable only to public sector hospitals in high-income countries. Further, only 3 of the OPD departments were included in the sample, precluding any generalization across other departments and in-patient/emergency settings. We collected data on variables besides those presented here but they were not included in the model either due to lack of variability or model convergence issues.

Conclusions

Clinical empathy as perceived by clients does not correlate with physician's self-assessment, even after adjusting for many possible explanatory factors. This may impact the success of the clinical encounter, client satisfaction, and treatment outcomes. Across the world, medical curricula do not incorporate empathy training in a major way (23). Even where patient communication skills are taught or emphasized, specific training on empathy is largely missing. Empathy is a skill that can be taught. Empathy training in medical schools and continuing medical practice is justified by the strong evidence of its benefits to the client, physician, and health system (33,34). Curricular changes, training programs, monitoring, and feedback have been recommended to increase empathetic clinical practice (19). Evidence suggests that it is possible to train physicians to enhance their empathy and compassion by following rules such as sitting while consulting, detecting nonverbal cues, responding aptly to opportunities for compassion, maintaining eye contact, and verbally showing validation (35). Also, physicians could be trained in workshops that focus on interpersonal reactivity, better patient communication, delivering bad news, and representing the illness in plain language (27).

Health system managers must realize that improving physician empathy involves client–physician communication, real-time client feedback, incorporating empathy as an employee appraisal component, an empathy enabling health care environment, and workplace culture. These measures will help align physician care with the client’s expectations.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: RSA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. DV: Software, Data curation, Writing—Original draft, Supervision. JK: Software, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. ZAZ: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Review & Editing. KSK: Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. RJ: Software, Writing—Review & Editing.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of King Salman Hospital (Approval letter no. H1RE-Aug18-01).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of King Salman Hospital-approved protocols.

Statement of Informed Consent: Electronic written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Rizwan Suliankatchi Abdulkader https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3140-2614

References

- 1.Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76-84. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237-51. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SS, Park BK. Patient-perceived communication styles of physicians in rehabilitation: the effect on patient satisfaction and compliance in Korea. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(12):998-1005. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318186babf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen R. Empirical research on empathy in medicine—a critical review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(3):307-22. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, Sultan S. A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care. Psychooncology. 2012;21(12):1255-64. doi: 10.1002/pon.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robieux L, Karsenti L, Pocard M, Flahault C. Let's talk about empathy! Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(1):59-66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DD, Kellar J, Walters EL, et al. Does emergency physician empathy reduce thoughts of litigation? A randomised trial . Emerg Med J. 2016;33(8):548–552. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche J, Harmon D. Exploring the facets of empathy and pain in clinical practice: a review. Pain Pract . 2017;17(8):1089-96. doi: 10.1111/papr.12563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banja JD. Empathy in the Physician's Pain practice: benefits, barriers, and recommendations. Pain Med. 2006;7(3):265-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNally PJ, Charlton R, Ratnapalan M, Dambha-Miller H. Empathy, transference and compassion. J R Soc Med. 2019;112(10):420-3. doi: 10.1177/0141076819875112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwenk TL. Physician well-being and the regenerative power of caring. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1543-4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsari V, Tyritidou A, Domeyer P-R. Physicians’ self-assessed empathy and patients’ perceptions of physicians’ empathy: validation of the Greek Jefferson scale of patient perception of physician empathy. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020 (Special issue):9379756. doi: 10.1155/2020/9379756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arellano M, Marques L de A, Meylan C. Humility and empathy in the foreground. Krankenpfl Soins Infirm . 2015;108(2):61-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernardo MO, Cecílio-Fernandes D, Costa P, et al. Physicians’ self-assessed empathy levels do not correlate with patients’ assessments. PloS One. 2018;13(5):e0198488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alzayer ZM, Abdulkader RS, Jeyashree K, Alselihem A. Patient-rated physicians’ empathy and its determinants in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med . 2019;26(3):199-205. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_66_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermans L, Hartman TO, Dielissen PW. Differences between GP perception of delivered empathy and patient-perceived empathy: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(674):e621-6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X698381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lelorain S, Cattan S, Lordick F, et al. In which context is physician empathy associated with cancer patient quality of life? Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(7):1216-22. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lelorain S Brédart A Dolbeault S, Cano A, Bonnaud-Antignac A, Cousson-Gélie F, et al. How does a physician's accurate understanding of a cancer patient's unmet needs contribute to patient perception of physician empathy? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(6):734-41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haider SI, Riaz Q, Gill RC. Empathy in clinical practice: a qualitative study of early medical practitioners and educators. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(1):116-22. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.14408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howick J, Steinkopf L, Ulyte A, et al. How empathic is your healthcare practitioner? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0967-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Kline JA, Jackson BE, et al. Association between emergency physician self-reported empathy and patient satisfaction. PloS One. 2018;13(9):e0204113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park C, Lee YJ, Hong M, et al. A multicenter study investigating empathy and burnout characteristics in medical residents with various specialties. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(4):590-7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.4.590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahrweiler F, Neumann M, Goldblatt H, et al. Determinants of physician empathy during medical education: hypothetical conclusions from an exploratory qualitative survey of practicing physicians. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lelorain S, Sultan S, Zenasni F, et al. Empathic concern and professional characteristics associated with clinical empathy in French general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2013;19(1):23-8. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2012.709842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaitoff A Sun B Windover A, Bokar D, Featherall J, Rothberg MB, et al. Associations between physician empathy, physician characteristics, and standardized measures of patient experience. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1464-71. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walocha E, Tomaszewska IM, Mizia E. Empathy level differences between polish surgeons and physicians. Folia Med Cracov. 2013;53(1):47-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada Y, Fujimori M, Shirai Y, et al. Changes in Physicians’ intrapersonal empathy after a communication skills training in Japan. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1821-6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvester J, Patterson F, Koczwara A, Ferguson E. “Trust me…”: psychological and behavioral predictors of perceived physician empathy. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):519-27. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Passalacqua SA, Segrin C. The effect of resident physician stress, burnout, and empathy on patient-centered communication during the long-call shift. Health Commun. 2012;27(5):449-56. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.606527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh S, O’Neill A, Hannigan A, Harmon D. Patient-rated physician empathy and patient satisfaction during pain clinic consultations. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188(4):1379-84. doi: 10.1007/s11845-019-01999-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menendez ME, Chen NC, Mudgal CS, et al. Physician empathy as a driver of hand surgery patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Br. 2015;40(9):1860-5.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.06.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK, Feudtner C. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):219. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffrey D, Downie R. Empathy—can it be taught? J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2016;46(2):107-12. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2016.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, et al. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PloS One. 2019;14(8):e0221412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]