Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the development trajectories of several world economies with India being no exception. The country presently is the second worst affected in terms of total infections despite inducing a nationwide lockdown in the initial stages. In addition to curtailing infection spread, ensuring food security during and post pandemic is a major concern for the country owing to the high percentage of stunting and undernourishment already present and a relatively high proportion of vulnerable workforce with no regular source of income amidst the lockdown. The present article therefore ascertains the impact of the pandemic on the food systems which can potentially affect food security in the country as well as the government introduced reforms and policy measures to tackle them. Following the analysis, we suggest measures like digitally enhancing connectivity of neighbourhood retail or ‘Kirana’ stores in urban and rural areas, distribution of therapeutic foods and immune supplements among the impoverished societal sections through existing government schemes and promotion of ‘planetary healthy diets’ for overcoming food-insecurity while increasing nutrition security and ensuring long term food sector sustainability.

Keywords: Agriculture, COVID-19 pandemic, Food systems, Food-security, Food supply chains, Sustainability

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Governments around the world presently are witnessing unprecedented socio-economic challenges as they attempt to contain the spread of the novel SARS-Cov-2 or COVID-19 (Mulvaney et al., 2020; Nicola et al., 2020). Although India faces the grim reality of being the second worst affected nation from the pandemic (www.covid19.who.int), the mortality rate remains extremely low (1.41%) and the overall infection spread has also started to decline with active cases forming only 1.51% of the total infections as on 2nd March 2021 (www.mohfw.gov.in). The country owing to a very high population density therefore stares at the daunting task of maintaining the declining trend of infection spread, ensuring adequate health facilities for the infected, providing livelihood options to migrant workers within rural and urban sectors as well as boosting economic resurgence (Kundu 2020; Paital et al., 2020).

Measures for containing the spread of the virus involved issuance of a nation-wide lockdown of 21 days effective from the 25th of March 2020 which was extended until May 2020 (MHA GoI, 2020a; 2020d). Additionally, based on total active and reported cases, all districts within the country were categorised under red, orange and green zones with the former being at maximum risk while containment zones were created within these districts wherever cases were confirmed (MHA GoI, 2020d). Several relaxations on movement and resumption of activities were gradually allowed by the government in areas outside containment zones through guidelines for phased re-opening in order to revive the national economy (MHA GoI, 2020e; 2020f, 2020g). Besides, national and state governments in the past months have been successful in spreading extensive awareness related to the virus transmission and necessary precautions in both urban and rural sectors (www.mohfw.gov.in; www.mygov.in). Efforts have also been made for domestic mass production of N95 masks, personal protection equipment (PPE) kits and ventilators (PIB 2020c). The government also advised alcohol based sanitizer manufactures to boost their production capacity and fixed the prices of sanitizers and surgical masks in order to ensure their unhindered availability (PIB 2020a; 2020b). Furthermore, as of 16th January 2021, the vaccination drive has also been initiated with 1,48,54,136 doses administered as of 2nd March 2021 (PIB 2021; www.mohfw.gov.in).

In addition to the economic and health concerns, ensuring availability of sufficient and nutritious food for all (Laborde et al., 2020) is another serious concerns as the pandemic impacted through various supply and demand side challenges such as non-operational manufacturing mills, disrupted transportation chains, labour-intensive farming systems and subsequent labour shortages owing to movement restrictions (ADB 2020; Reardon et al., 2020; Workie et al., 2020). The national economy was expected to shrunk by 4.0% in the Financial Year 2020 owing to trade barriers, reduced mobility and labour migrations (ADB 2020). Agriculture, a major influencer of the Indian economy contributed 3,047,187 Crore (30471870 million INR) to the national GVA (Gross Value Added) in the year 2019–20 (Economic Survey 2020b). Critical to the development of agriculture is the food processing sector which constituted 11.11% of the former's GVA in 2018–19 and plays a pivotal role in issues related to food security, employment, price regulation and provision of nutritious food (GoI MOFPI, 2020). Moreover, attaining nutritional security has always been critical to the country's progress as it grapples with a 14.5% PoU (Prevalence of Undernourishment) and 37.5% stunting in children under five (FAO 2019a).

The first lockdown period in India coincided with the peak harvest season of winter crops (NAAS 2020). However, the government subsequently included agriculture, fisheries and livestock farming under list of selected activities permitted during the second phase of lockdown in order to reduce grain loss and other negative impacts (GoI MHA GoI, 2020c). Agricultural produce distribution and marketing in India is a highly regulated process governed by a number of legislative measures related to procurement, storage and transportation at the Central and State level and involves a number of intermediaries (AGRICOOP 2014; AGRICOOP 2018). However, despite being a leading producer of several agricultural and food products and also having a well-structured institutional and statutory setup for distribution of food, several concerns in the form of hidden hunger and food losses remain pertinent which may become graver in the face of pandemic (GoI MOFPI, 2020; Mishra and Rampal 2020). Further augmenting COVID-19 induced disruption of agricultural systems is the impact of various climate change related concerns such as warming temperatures, environmental pollutants, falling groundwater levels and deteriorating air quality on crop yields (Rasul 2021) and several assessments have recognized the close association between agriculture, food systems, health and environment (Campbell et al., 2016; Lam et al., 2017; Pradhan et al., 2018). Based on modelling simulations, Daloz et al. (2021) concluded that the direct effects of climate change manifesting in the form of temperature and precipitation alterations can lead to wheat losses between −1% and −8% while indirect effects of climate change impacting water availability can cause even higher yield losses in the Indo-Gangetic plains. Similarly, Mukherjee et al. (2021) have further deduced wheat followed by mustard and rice to be the most sensitive towards ambient ozone concentrations in the troposphere. In this context, the present study was aimed to understand the (i) existing status of food security in the county and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on it, (ii) institutional reforms introduced by the Government of India for building the resilience of food sector and, henceforth provides (iii) science based policy recommendations for building resilience of food systems during and post COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and methods

In order to deal with the pandemic crisis, the Government of India has been issuing regular advisories and notifications regarding necessary precautions and guidelines to be followed, rate of infection spread, health infrastructure and strategic mitigation measures (relief packages, vaccine development) being adopted (www.mohfw.gov; www.mha.gov; www.mygov.in). Owing to its recent nature, in-depth scientific assessments exploring the impact of pandemic on various sectors influencing social security remain limited. The present study therefore attempts to bridge this gap by gauging the impact of the pandemic on the food sector and the institutional measures in place for its mitigation.

The first stage involved understanding the present condition of the nation's food sector with respect to food procurement, storage, processing and consumption. Thus, annual reports from the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare (MAFW), Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MOFPI) and Department of Food and Public Distribution (DFPD) were retrieved and studied (AGRICOOP 2014; 2018; CACP 2020; DFPD 2020; GoI MOFPI, 2020). Thereafter, government releases from the Press Information Bureau (PIB), the nodal agency responsible for disseminating information related to government policies and programmes (www.pib.gov.in) and monthly bulletins of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) (NFSA 2020a; 2020b) related to the food sector along with published research and opinions highlighting international (Arndt et al., 2020; Arouna et al., 2020; Garnett et al., 2020) and national (Alvi and Gupta 2020; Harris et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020) concerns related to the impact of the pandemic on the food supply chain were analysed. Subsequently, institutional and policy measures introduced by the government for shielding the food sector from risks posed by the pandemic were examined closely to understand their characteristic features. For this purpose, details of the economic and social relief packages were retrieved from the PIB and MAFW (www.pib.gov.in; Gazette of India, 2020a; b; c). Further, all administrative interventions were clubbed under the concerned areas they aimed to address as well as the relevant stage of the food supply chain they targeted.

Effectual policy-making is critical for addressing challenges arising from the pandemic and boosting institutional capacity with respect to food systems (Cardwell and Ghazalian 2020; IPES-Food 2020). Fulfilment of the first two objectives helped strengthen the third which involved suggesting relevant recommendations to build long term sustainability, resilience and adaptability of food systems against the present pandemic as well as in the event of a future crisis impacting public health and social security (Allen et al., 2017; Folke et al., 2010; Sperling et al., 2020). In order to build an insight for the same, existing policy briefs published by several international organisations such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (FAO 2019a; 2019b; 2020), Asian Development Bank (ADB) (ADB 2020), Food Security Information Network (FSIN) (FSIN 2020) as well as the reports published by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on food security and nutrition constituted to advice the Committee on World Food Security (HLPE 2014; 2017; 2020) dealing with food insecurity and strategies for overcoming it were consulted. Additionally, policy papers and briefs from the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NAAS), the academy of India dedicated to advancing agricultural research for national and societal welfare (NAAS 2017; 2019a; 2019b; 2020) along-with various research and review assessments dealing with agricultural sustainability (Bains 2020; Bhavani and Gopinath 2020; Waha et al., 2018) as well as importance of social protection programs (Hidrobo et al., 2020) and nutritional security (Galanakis 2020; Olaimat et al., 2020) were studied.

3. Results and discussion

The sudden emergence and rapid spread of the present pandemic has thrown up numerous social and economic challenges in addition to the universal concern of boosting health-care systems and provision of equal health services to all individuals irrespective of their wealth status (Gopalan and Misra 2020; Tisdell 2020; United Nations 2020). Impact on food systems could likely result from restrictions or lockdowns imposed at national scales to contain the spread of the pandemic by disrupting trade flows and transportation chains, food price fluctuations, reducing buffer stocks of perishable food items along-with creating obstruction in labour supply (Farias and Araujo 2020; Garnett et al., 2020; Falkendal et al., 2021). Table (1) further depicts opinions and research world-wide dedicated to the cause of impact of COVID-19 on food and health.

Table 1.

Impact of COVID-19 on food security at the international stratum.

| Country | Focus | Conclusions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Impact of movement restrictions on food prices in 31 countries between January to May 2020 | More stringent stay-at-home restrictions witnessed increase in prices in March as compared to the initial months with meat, fish and seafood being more severely impacted as opposed to cereal, milk, eggs and oils. | Akter (2020) |

| Bangladesh | Development of indicators for monitoring food system disruptions resulting from pandemic | Labour, seed, fertilisers, resource supply, machinery, logistics, output market can serve as effectual monitoring indicators warning against food supply disruptions | Amjath-Babu et al. (2020) |

| South Africa | Impact of lockdown on income distribution and food security | Households depending majorly on labour income and low educational attainment are more vulnerable to the risks of food security posed by lockdown policies Government transfer payments can help shield the detrimental impacts | Arndt et al. (2020) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) | Effect of restrictions on planting of staple crops and farm inputs in various countries of SSA | Most SSA countries are vulnerable to movement restrictions owing to high reliance on imports and poverty incidence along-with delayed harvesting and reduced labour | Ayanlade and Radeny (2020) |

| West Africa | Resilience of domestic rice value chains | Recommendations for short- and long-term policy interventions to reduce impact of COVID19 on rice chains | Arouna et al. (2020) |

| Britain | Food provisioning services among vulnerable groups and weaknesses in government response | People from Black, Asian, minority ethnic and with existing health conditions were most at risk while the government's response was piecemeal and majorly reliant on the voluntary sector | Barker and Russell (2020) |

| Kakamega county, Western Kenya | Impact of farm storage on household food security | Improved farm storage through hermetic storage bags can limit food insecurity arising from COVID induced restrictions | Huss et al. (2021) |

| China | Impact of pandemic on vegetable production, marketing and farmer households | The degree of restriction measures was directly proportional to the losses incurred by farmers while reduction in sales and unpredictability in prices was the dominant cause for supply disruptions | Jie-hong et al. (2020) |

| Tehran | Relationship between socio-economic factors, food security and dietary diversity before and during pandemic | Food security within the sample population improved in the initial stages of the outbreak while the consumption of warm beverages and legumes increased | Pakravan-Charvadeh et al. (2021) |

| Singapore | Challenges faced by Small Island States in ensuring food supply during pandemic induced supply disruptions | Increase in GDP per capita strongly favours food security. Besides, food diversity ensures security during crisis by allowing food imports from various geographical sources | Teng (2020) |

| Arab Gulf countries | Ascertaining challenges affecting food accessibility further worsened by the pandemic | Nutritional security and ensuring food availability for migrant workers and other vulnerable sections are major priority concerns. Modern production technologies can enhance food security at sustainable rates | Woertz (2020) |

Even-though both developed and developing nations are witnessing an economic slowdown, lack of well-planned mitigation measures could further adversely affect the functioning of food systems and consequentially worsen the food and nutrition insecurity in regions already affected with these issues (Udmale et al., 2020; United Nations 2020).

3.1. State of food security and concerns arising from COVID-19

While India is relatively better sheltered from the key drivers of acute food insecurity (conflicts, extreme weather events and economic shocks) than several regions in Middle and East Asia as well as Africa, considerable proportion of the country's population still remains undernourished, lacking access to clean water and sanitation services and engaged in the informal sector (FSIN 2020; GoI MOSPI, 2020). The above factors affect overall immunity levels of individuals thereby increasing their risk of contracting COVID-19. Production, procurement, stock, storage, movement and distribution are some key terms associated with maintenance of food security and ensuring access of food for all. Understanding the present state of affairs with respect to these key parameters would therefore prove critical in discerning the impact of the pandemic and the resulting lockdown restrictions on the food sector of the country.

As evident from Table 2 a the country is self-sufficient as far as production, procurement and storage of staple food grains (rice, wheat and coarse-grains) is concerned . Additionally, the 3rd Advance Estimates of the Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare also estimates record production for oilseeds (33.50 million tonnes) and cotton (36.05 million bales) (PIB, 2020e). Meanwhile, the 2nd Advance Estimates for the horticulture sector reveal a 3.13% increase over previous year in terms of total production with increase in fruits, vegetables, aromatic and medicinal plants while decrease in plantation crops and spices (PIB, 2020i). However, as evident production in the horticulture sector and cold storage capacity still lags behind food grains (PIB 2020d). Consequently, Harris et al. (2020) estimated the impact of Covid-19 on vegetable producers of the country (telephonic survey of farmers in four states) during the early stages of the pandemic. The study concluded that majority of farmers experienced disruptions in production owing to lack of transport, inputs, labour or storage.

Table 2a.

Food availability and storage statistics for India.

| Food Availability and Storage | |

|---|---|

| All India production of food grains (cereals and pulses), 2019-20 | 296.65 million tonnes |

| 2020-21(for Kharif season only) | 144.52 million tonnes |

| All India procurement for cereals (rice, wheat and coarse grains), 2019-20 | 865.52 lakh tonnes |

| 2020–21 | 611.15 lakh tonnes |

| Per capita net availability of food grains (per annum) 2019(P) | (kilograms per year) |

|

69.1 |

|

65.2 |

|

17.5 |

| Per capita net availability of food grains (per day) 2019(P) | (grams per day) |

|

189.3 |

|

178.6 |

|

47.9 |

| Stock of Rice and Wheat (FCI and State Agencies), 2020 | 512.94 lakh tonnes |

| Allocation of food grains (Rice and Wheat), 2019-20 | 659.57 lakh tonnes |

| 2020–21 | 452.39 lakh tonnes |

| Offtake of food grains (Rice and Wheat), 2019-20 | 621.90 lakh tonnes |

| 2020–21 | 389.21 lakh tonnes |

| All India Storage capacity (FCI and State Agencies), October 2020 | 802.70 lakh metric tonnes |

| All India cold storage capacity (March 2018) | 36229675 metric tonnes |

P = Provisional; FCI = Food Corporation of India (nodal agency for procurement and storage of food grains), 1 lakh = 100,000; 10 lakh = 1 million.

Sources (GoI MAFW, 2020; NFSA 2020a).

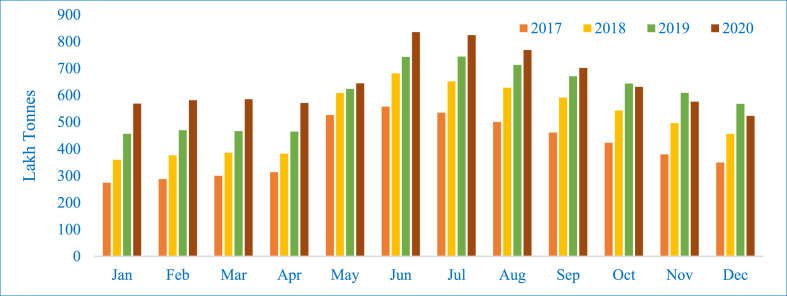

Another associated concern is the burgeoning food stocks (Fig. 1 ) in central pool which might rot and get wasted if not utilized in a timely manner. Rice stocks were 17.4% higher in March 2020 than the previous year when compared with the buffer norms. Increased allocation under NFSA and Other Welfare Schemes (OWS) as well as diversion of old stocks towards ethanol production and animal feeding have being suggested as some measures to reduce stocks and generate storage space (CACP 2020). Release of such excess stocks in open markets is likely to increase supply leading to price falls which could in turn reduce economic returns to farmers (Mahapatra 2020).

Fig. 1.

Stock of food grains in central pool (2017–2020) (NFSA 2020a).

Movement of food was another challenge encountered amidst the pandemic owing to lockdown restrictions and suspension of transportation services despite movement of essential goods being allowed (MHA GoI, 2020a; b). India, being less reliant on food imports (Table 2 b) primarily experienced disruptions in inter and intra state movement of food.

Table 2b.

Food processing and wastage statistics for India.

| Food Processing and Wastage | |

|---|---|

| GVA by food processing industries (2018–2019) | 2.08 Lakh Crore |

| GVA in agriculture per worker (2019–2020) | Rs 74044 |

| India's food export to the world (2018–2019) | US$ 35303.19 million |

| India's food import from the world (2018–2019) | US$ 19319.04 million |

| Percent loss (wastage) of major agriculture produce (2015) | |

|

4.65–5.99 |

|

6.36–8.41 |

|

4.58–15.88 |

|

3.08–9.96 |

|

0.92 |

| Registered Food Processing Industries (2016–2017) | 39740 |

| People employed in registered food processing sector (2017–18) | 19.33 Lakhs |

| People employed in un-registered food processing sector (2015–16) | 51.11 Lakhs |

GVA = economic value of goods and services produced by a sector contributing towards national economy.

1 Crore INR = 10 million INR.

Sources: (GoI MOFPI, 2020; GoI MOSPI, 2020).

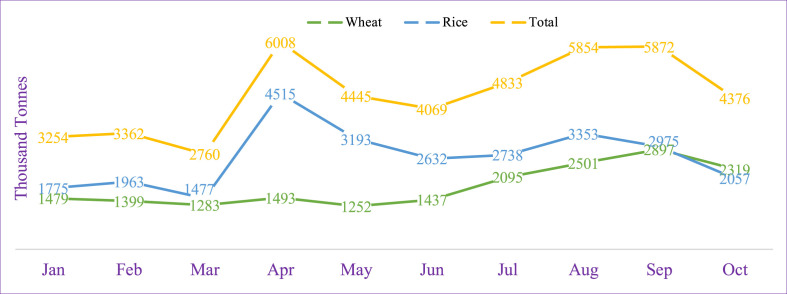

Figure (2) further depicts that movement was lowest in the month of March owing to the nation-wide lockdown and again witnessed a sharp rise in April owing to proper resumption of goods trains. Additionally, owing to disruptions in supply chains arrival of food commodities in markets witnessed a 64% decline as compared to the previous year in the first phase of lockdown (NAAS 2020). The country also experienced a decline in food exports (US$ 21260.91 million) and imports (US$ 13162.80 million) in 2019–20 (April–November) as compared to the previous year (Table 2b) (GoI MOFPI, 2020).

Fig. 2.

Movement of food grains (rice, wheat and total) by road and rail in 2020 (NFSA 2020a; 2020b).

Furthermore, reducing the amount of transit, storage and distribution losses is a major concern especially with regards to horticultural crops which account for the highest proportion of losses (Table 2b). Overall, the annual value of harvest and post-harvest agricultural losses was estimated at 92,651 Crores in 2015 (GoI MOFPI, 2020) with around 23 million tonnes of loss reported in grains (NAAS 2019a). While the losses in cereals are observed during farm level activities, fruit and vegetable losses occur owing to limited processing facilities, institutional gaps and below par utilization of existing capacity (GoI MOFPI, 2020; Sivaraman 2016). Such losses are likely to further increase during the pandemic owing to movement restrictions and labour shortage owing to migrations especially in states relying greatly on agricultural workforce like Punjab and Haryana (Chaba and Damodara 2020; Singh et al., 2020). Determining the effects at the state level, Kumar et al. (2021) elucidated the consequences of lockdown on farming systems in the agriculture dominant state of Uttar Pradesh. Differential availability of migrant labour, market closures and insufficient inputs were the major concerns affecting agricultural systems in the state during lockdown.

As regards food consumption, cereal intake forms a major source of energy and protein intake in both rural and urban sectors with contribution from non-cereal sources (milk, oils, fish and meat) increasing with a corresponding increase in income (GoI NSSO, 2014b). This highlights the dependence of the country's diet on plant-based food sources owing to their larger production and easier affordability (Economic Survey 2020a). Similarly, increase in average calorie and protein intake was observed to be positively correlated with rise in monthly per capita expenditure indicating the intricate relationship between household income and nutritional security (GoI NSSO, 2014b). Besides, the pattern of consumer expenditure (Table 2 c) indicates that the bulk proportion of income in rural India is spent on food procurement (GoI NSSO, 2014a).

Table 2c.

Food consumption in India.

| Food Consumption | Rural | Urban |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Intake of India (2011–12) | ||

|

2233 | 2206 |

|

60.7 | 60.3 |

|

46 | 58 |

| Pattern of Consumer Expenditure (2011–12) in rupees | ||

|

756 | 1121 |

|

673 | 1509 |

| Trends in percentage composition of Consumer Expenditure (2011–12) | ||

|

12.0 | 7.3 |

|

3.1 | 2.1 |

|

9.1 | 7.8 |

|

3.8 | 2.7 |

|

4.8 | 3.4 |

|

1.9 | 2.3 |

|

1.8 | 1.2 |

| Per capita consumption of different commodities (2011–12) per annum | ||

|

74.62 | 56.73 |

|

53.85 | 52.57 |

|

9.53 | 10.96 |

|

52.71 | 52.61 |

|

52.72 | 65.97 |

| Beneficiaries covered under the Food Security Act (2018–19) | 97.62% | |

| Beneficiaries under Integrated Child Development Scheme (2018–2019) | 87560671 | |

Sources: (GoI MOSPI, 2020; GoI NSSO, 2014a).

This already delicate balance between poverty, food security and agricultural productivity especially in the economically weaker sections of the society (Hajra and Ghosh 2018; Priyadarshini and Abhilash 2020) faces the risk of disruption since employment (reduction by 0.9% during November) and household incomes have witnessed a downward trend owing to the pandemic (CMIE 2020a). Another disturbing statistic is further fall in female workforce participation (accounted for 13.9% of job losses in April 2020) during the pandemic which is already heavily skewed in favour of men (CMIE 2020b) with quarterly average agricultural wages as of 2018 for women (172) also being below males (247) (GoI MOSPI, 2020). This could have major implications on household food security in the long run since women can contribute significantly in producing and provisioning food (Holland and Rammohan 2019; Rao et al., 2019a) and therefore need to be included within social protection schemes (Hidrobo et al., 2020). Besides, lockdown induced school closures are likely to negatively impact nutritional security of rural children and pregnant mothers since a vast majority depends on cooked meals provided by the government in all schools under the Mid-day Meal Program and Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) (Alvi and Gupta 2020). This could in turn lead to worsening of wasting and mortality ratios in children under five (Headey et al., 2020).

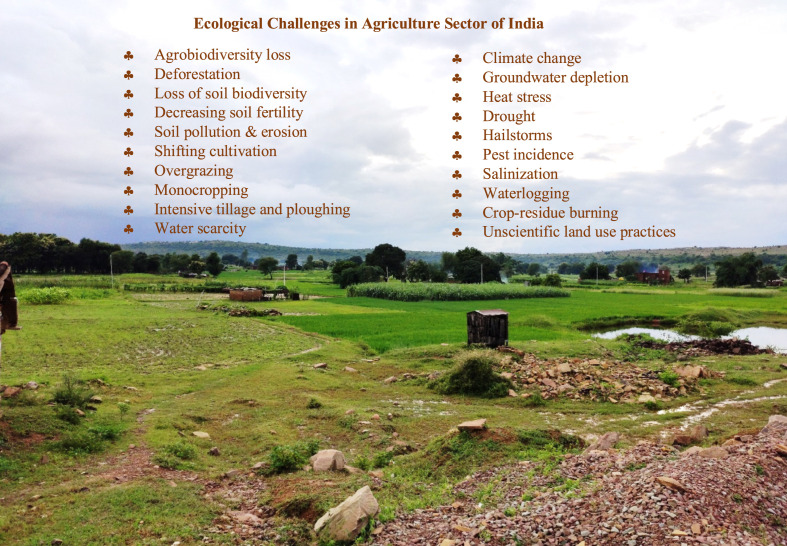

Simultaneously, percentage share of GVA (key indicator of a sector's economic performance) from Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing within India's total GVA has been on a declining trend (from 18.2% in 2014–15 to 16.5% in 2019–20) reflecting transformational changes in the economy (Economic Survey 2020b). This creates additional challenges for financial inclusion (access to financial services and institutional credit at affordable costs) of rural households, majority of which are engaged in agricultural and cultivation activities which is critical for their empowerment, growth and social inclusion (NABARD 2018; NAAS 2019b). The present pandemic therefore has the potential to increase the vulnerabilities of the informal labourers (Lele et al., 2020) as well as for marginal farmers with limited land holdings and digital literacy by reducing access to markets and institutions for input procurement, selling, investments and loans as concluded by several assessments (Arndt et al., 2020; HLPE 2020; Woertz 2020). In addition to the supply chain and social challenges, several ecological concerns are also closely linked with food security and agricultural systems (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

An indicative list of ecological challenges affecting agriculture in India.

Agricultural sector in India is facing a multitude of ecological challenges such as agrobiodiversity loss, pollution, decreasing soil fertility and soil carbon pool, unscientific land use practices among others (Rao et al., 2019b; Sarkar et al., 2020a; Bhattacharya et al., 2020; Dubey et al., 2021). The sector is extremely vulnerable to climatic shocks manifested as rainfall-deficit or heat stress related episodes owing to dependence on rainfall, small farm holdings along-with financial and infrastructure constraints (Birthal et al., 2014; Birthal and Hazrana 2019). Besides, states leading in agricultural production such as Punjab and Haryana also experience severe depletion in groundwater levels (Suhag 2016). On the other hand, use of agrochemicals has also been increasing in the past two decades (from 17360 in 2001–02 to 27375 thousand tonnes in 2018–19) (GoI MAFW, 2020). Excessive use of fertilizers besides leading to loss of soil quality can increase toxin concentration in ground water as well as inflate overall food production costs (Tilman et al., 2002). Therefore, innovative farming practices based on ecological agriculture is essential for ensuring food security and ecological stability (Priyadarshini and Abhilash 2020). Simultaneously, incentives, policy regulations and government measures that focus on biodiversity and ecosystems is also required (McElwee et al., 2020).

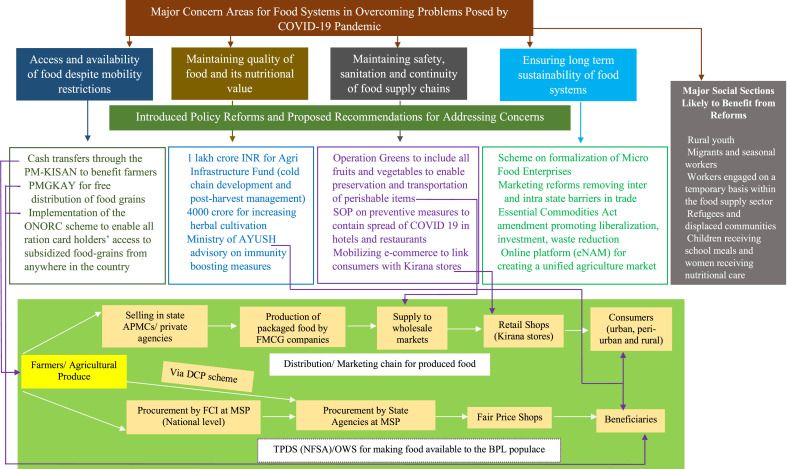

3.2. Institutional reforms introduced for ensuring resilience of food systems

The Central Government in order to mitigate the challenges affecting economic resurgence in wake of the pandemic has undertaken a tremendous initiative of recognising local initiatives and boosting self-reliance across sectors (Table 3 ) through the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (Self-reliant or Self-sufficient India) movement with an economic package of 20 lakh crore (INR) being allocated to it (PIB, 2020g). The third tranche of this package has been dedicated exclusively towards agricultural reforms and maintenance of food security. The breakup of reforms depicted in Fig. 4 display that the policymakers have made attempts in addressing various food security associated concerns. As a primary measure, free grain (wheat and rice) distribution was undertaken for eight months under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) through which 321.06 lakh tonnes of grain was allocated towards 81 crore beneficiaries covered under the NFSA (NFSA 2020a; PIB, 2020m).

Table 3.

Institutional reforms undertaken by the Government for ensuring Food and Agriculture sector stability.

| Scheme/Reform/Relief Packages | Salient Features |

|---|---|

| Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (Prime Minister's Poor Welfare Scheme) |

|

| The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 |

|

| The Farming Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 |

|

| The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 |

|

| Scheme for Formalisation of Micro food processing Enterprises (FME) |

|

| Central sector scheme for Agriculture Infrastructure Fund |

|

| Operation Greens |

|

| eNAM |

|

FPOs- Farmer Producer Organisation; NAFED- National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India, PACS- Primary Agricultural Credit Societies; SHGs- Self Help Groups Source: Gazette of India, 2020a, Gazette of India, 2020b, Gazette of India, 2020c; GoI MOFPI 2021; PIB, 2020f, PIB, 2020h, PIB, 2020j, PIB, 2020k, PIB, 2020l)

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the major thrust areas related to food systems that need to be addressed in wake of COVID-19 pandemic and the introduced institutional reforms against them with the Violet Arrows indicating the stages of the food supply chain the measures are likely to impact.

*APMC- Agricultural Produce Market Committee (market yards managed by State Governments for buying farmer produce); Ministry of AYUSH- Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy; DCP- Decentralised Procurement, eNAM- National Agriculture Market; BPL- Below Poverty Line; FMCG- Fast-moving Consumer Goods; MSP- Minimum Support Price, ONORC- One Nation One Ration Card OWS- Other Welfare Schemes, SOP- Standard Operating Procedure; TPDS- Targeted Public Distribution System (system of food distribution in India among the economically weaker

sections of society to enhance their food security). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

As evident from Fig. 4 food management in India is a three-pronged process involving food procurement from producers, distribution to vulnerable sections and maintenance of buffer stocks for ensuring security (Economic Survey 2020b). The DFPD under the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution is the nodal agency responsible for regulating the entire food supply chain (DFPD 2020). Primarily, food is provided at subsidized rates to the populace falling in the BPL (Below Poverty Line) category via the Public Distribution System (PDS) (George and McKay, 2019) while the rest purchase food-items and groceries from various retail outlets and super-markets as depicted in the lower panel of Fig. 4. This involves direct procurement from farmers by the national and state governments takes place at MSP (minimum price guaranteed for an agricultural commodity irrespective of existing stock, excess production or fall in market price) followed by food distribution to the beneficiaries (75% rural and 50% urban population) which are covered under the NFSA, while packaged food via FMCGs and other retail stores provides access to the other consumers (DFPD 2020; George and McKay, 2019).

.

Reforms and amendments aside several other measures also hold the potential of boosting food security. An example of this the Mega Food Park Scheme (MFPS) implemented by the MOFPI which through a cluster based approach aims at boosting infrastructure facilities with respect to farm, transportation, logistics and centralized processing in order to reduce wastage and increase processing of perishable commodities (GoI MOFPI, 2012). Presently 22 MFP projects are operational (www.mofpi.nic.in). Besides, separate funds have also been allocated towards animal husbandry, fisheries, herbal cultivation and bee keeping initiatives all of which would improve the resilience of food systems (PIB, 2020j). On the other hand, strengthening of the Integrated Cold Chain Network for storing of perishables and processing of harvest into value added products (PIB 2020d) as well as provision of increased interest subvention to dairy co-operatives for the year 2020–21 has also been undertaken since the demand of milk reduced during pandemic induced lockdown (PIB, 2020j). Simultaneously, providing due recognition towards maintenance of ecological sustainability for food security is the research and development sector of the country. A prominent example of this is the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) initiated programme on Marine, Microbial Resource, Secondary Agriculture and Food Processing which supports research projects related to bioresources (identification, characterization, conservation, utilization), sustainable bio-economy and value addition of useful bioresources (www.dbtindia.gov.in). Biotechnological advances are also being used for improvement in crop and nutritional quality for overcoming environmental stresses, development of climate and pest resilient varieties as well as for production of ethanol from agricultural residues (DBT 2021).

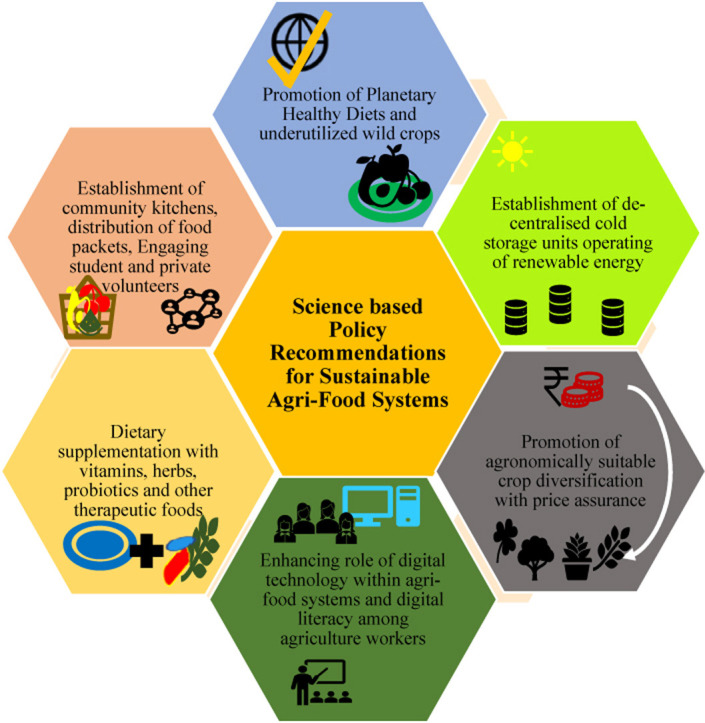

3.3. Recommendations for enhancing agri-food systems resilience

Results from the previous objectives reinstate that certain transformations in the supply chain architecture can ensure long term sustainability and build resilience of the agri-food sector (Sperling et al., 2020) against future outbreak of emerging infectious diseases (EID) similar to the present pandemic and yield additional benefits in the form of environmental preservation and public health protection (Marco et al., 2020). Social protection programs are critical to mitigate COVID-19 crisis and support vulnerable populations (Hidrobo et al., 2020). In addition to the PMGKAY, the state of Kerala initiated distribution of pre-prepared food kits via the TPDS through the Fair Price Shops (FPS). The food kits contain fixed quantities of 17 items such as flour, sugar, tea among others (Pothan 2020). The kits help in the distribution of equal amounts of essential food items to every poor household, prevent hoarding of goods and also limit crowding at the FPS. Another measure included establishing community kitchens for serving cooked food to the migrant labours and health-line workers (IPES-Food 2020; Pothan 2020). Uttar Pradesh even came up with the innovation of geo-tagging community kitchens for improved monitoring (PTI 2020). Additionally, student volunteers and non-government organisations could be tapped while private organisations could also be motivated by recognising ‘community kitchens’ under CSR (corporate social responsibility) activities during the pandemic.

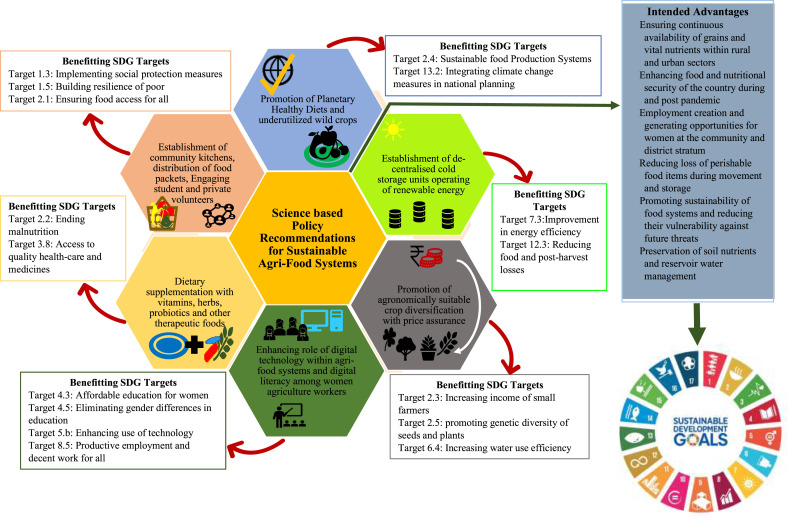

As evident from Figure (5) , ensuring resilience within present food systems against EID requires transformations at every stage of the supply chain as through adoption of long-term adaption and mitigation measures similar to the strategy used for dealing with climate change related issues as opposed to only post outbreak measures (Allen et al., 2017; Pike et al., 2014).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of proposed recommendations for strengthening agri-food systems along-with SDG targets (NITI Aayog, 2016) likely to benefit from their successful implementation.

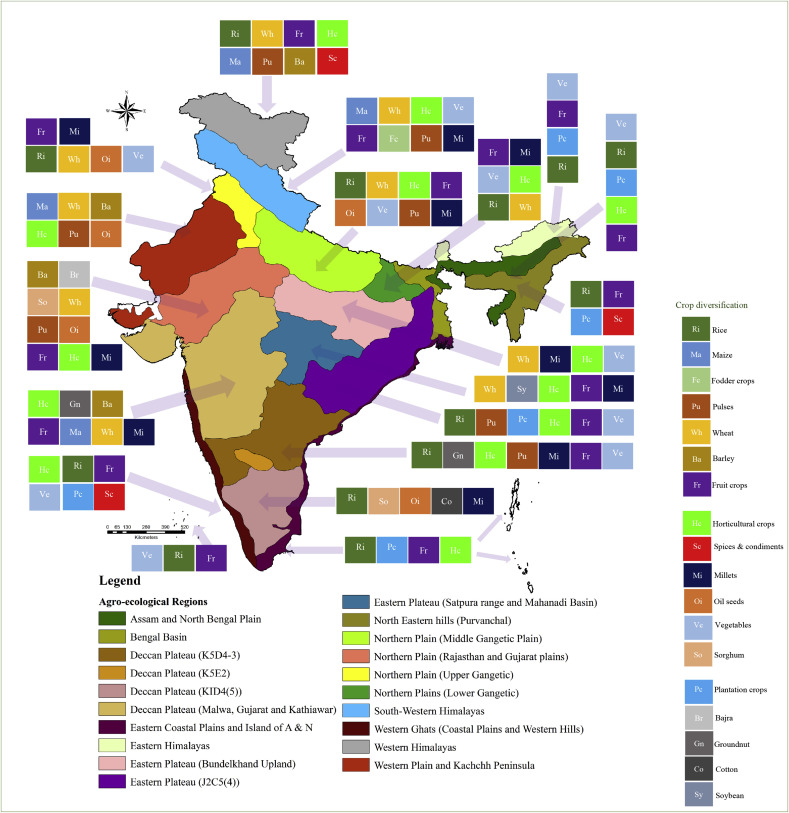

A shift towards agrarian sustainability through promotion of plant agrobiodiversity and crop diversification strategies can enhance food security as well as enhance financial security of farmers (Leyva and Iores 2018; Waha et al., 2018; Dubey et al., 2019). Presently, most farmers prefer paddy and wheat cultivation since these crops fetch an assured price (MSP). Even though MSP exists for other crops (jowar, bajra, maize, sunflower, soyabean and several pulses) it is the former two which are procured in the maximum quantities by the government and are therefore capable of yielding maximum benefits to farmers (DFPD 2020). Furthermore, coverage of rice farmers under the procurement process is not uniform as Punjab (95%) and Haryana (70%) account for maximum coverage while states like Uttar Pradesh (3.6%) and Bihar (1.7%) with maximum proportion of marginal farmers account for least (CACP 2020). Several assessments have also concluded that agricultural markets in India are disorganised, less accessible to smallholder framers and offer limited trading opportunities for High Value Crops including fruits and vegetables thereby hindering economically vulnerable farmers from cultivating them (Meenakshi and Banerji 2005; Negi et al., 2018; Birthal et al. 2019, 2020). Birthal and Hazrana (2019) further concluded that adoption of diversification strategies favours resilience of agricultural systems from climatic shocks. Therefore, regularization and universalisation of input subsidies and loan waivers based on economic state and regional concerns of farmers as well as direct income support for diversification of farming systems might encourage more farmers to adopt such practices (NAAS 2019b). Successful implementation of crop diversification strategies based on soil characteristics and agro-climatic requirements as depicted in Fig. 6 could also help relieve buffer cereal stocks along-with alleviation of environmental concerns such as depleting water reservoirs and soil nutrients (Bains 2020; NAAS 2020) Similarly, syncing farm diversification with exploration and cultivation of underutilized wild crops can also cater towards nutritional security and climate resilient agriculture (Singh et al., 2019). Two other major avenues which can be tapped for attainment of food security and sovereignty along-with agro-ecological conservation is India's immense biocultural diversity and traditional knowledge systems (Loh and Harmon, 2005; Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019; Priyadarshini and Abhilash 2019; Resler and Hagolani-Albov 2021). Fostering nexus development between cultural practices of communities, traditional knowledge related to agricultural systems and crop cultivation can progressively shield the nation from disruptions related to food access and distribution.

Fig. 6.

Existing as well as proposed crop diversification patterns for various agro-ecological regions of the India. Crop diversification is not only essential for ensuring food security by dietary diversification, but also imperative for conferring resilience and agroecosystem stability while enhancing farmer's income. Since India is one of the Vavilovian centres of crop diversity, climate resilient, nutritionally rich, and wild edibles must be utilized for crop diversification for a planet healthy diet.

Another concept integrating the dual targets of environmental sustainability and ensuring nutritious diets at the production stage of the agri-food systems is the Farm-Systems-for-Nutrition (FSN) approach since it aims at identifying the prevailing nutrition deficiencies in the location where the farming system is being situated and then overcoming them through cultivation of targeted crop varieties and farming practices (Bhavani and Gopinath 2020). This approach is important in building resilience as it promotes local crop varieties, decentralisation of food value chains and community capacity-building all of which are the working tenets of the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat Scheme’. Integrating other sustainable agricultural practices like mulching, intercropping, organic farming, mixed farming, crop rotation etc with the FSN approach would not only help alleviate food insecurity but also reduce agricultural emissions (Wollenberg et al., 2016).

Simultaneously, emerging practices relevant to the field of ecological and environmental sustainability include the concepts of urban and peri-urban agriculture, urban farming and urban gardening all of which involve production of food on urban lands using diverse methods and bears major positive implications on varied aspects linked to urban sustainability such as food security, biodiversity and job creation (Borysiak et al., 2017; Caputo et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2015). Langemeyer et al., (2021) while acknowledging the neglect urban agriculture (UA) is presently facing owing to more lucrative market avenues in the urban sector such as housing and transport also ascertain the critical role UA can play in building urban resilience by ensuring food supply for sustenance of local communities when external supply chains are disrupted such as during the pandemic induced lockdown. Furthermore, UA and urban gardens also have the potential to enhance food and nutrition literacy by better connecting urban consumers with food production processes thereby fostering behavioural changes towards sustainable and low carbon footprint food choices (Mitchell et al., 2019; Petrovic et al., 2019; Puigdueta et al., 2021). Likewise, crop cultivation on polluted or degraded lands is another approach that can aid several sustainability targets related to biofortification, land resource conservation and restoration and also address the dual challenges of food insecurity and scarcity of arable lands (Abhilash et al., 2016). Several field based trials have been undertaken for various crops such as Maize (Meers et al., 2010), Rice (Yu et al., 2014); Bitter gourd (Ismail et al., 2014) and Onion (Stasinos and Zabetakis 2013) demonstrating their growth in contaminated lands along-with the accumulation of various pollutants in their edible parts.

Lack of proper cold chain network which helps in interim storage of fruits and vegetables during the course of distribution can be a major cause for food wastage and impact resilience of the horticulture sector (Balaji and Arshinder 2016; Raut et al., 2019). Unfortunately, in India around 18% horticultural losses are incurred annually owing to limited post-harvest storage infrastructure leading to supply-demand gaps and malnutrition (GoI MOFPI, 2020; Sivaraman 2016). The government has formulated the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund to ameliorate the financial constraints associated with post-harvest infrastructure (PIB, 2020l). However, complimenting this measure with establishment of decentralised cold storage units operating on either solar or biomass energy within rural districts and villages thoroughly deprived of storage facilities (southern and north eastern states) would further reduce food losses, generate employment at the local scale, regulate price volatility and tremendously benefit small-scale farmers (Mishra et al., 2020; Sivaraman 2016). On the other hand, encouraging investments and awareness about electricity independent storage options such as evaporative coolers (maintain high relative humidity and lower temperatures as compared to field conditions) can also solve the problem of horticultural losses and storage (HLPE 2014).

The pandemic has also witnessed a change in consumption patterns and consumer behaviour with rise in purchase of packaged foods and grocery supplies owing to the ‘stay-at-home’ mandate (Cariappa et al., 2020; Loxton et al., 2020; Workie et al., 2020). Therefore, efforts can be undertaken by the state administration to prepare an inventory of existing neighbourhood retail shops (Kirana stores) at the district, sub-district and block levels. States could also outsource this activity to private organisations. B2B (business to business) and e-commerce companies could then be targeted for ensuring continued maintenance of supplies within these retail stores during the lockdown (Gavin et al., 2020; Mishra and Chanchani 2020; NAAS 2020). Since Kirana stores in India are numerous in number and well distributed within residential communities keeping them well stocked might lead to limited commutation by people for procurement of essential foods which is a major parameter to contain spread of the virus (Sarkar et al., 2020b).

Nutritional security is a critical component of ensuring food security with the National Nutrition Mission (POSHAN Abhiyaan) of the Government targeting attainment of the same among children and women through inter-sectoral collaborations and appropriate use of technology (www.poshanabhiyaan.gov.in). Additionally, efforts targeting dietary supplementation with elements such as vitamin C and zinc, medicinal herbs, legumes and other bioactive ingredients with documented effect on enhancing immunity (Galanakis 2020; Pakravan-Charvadeh et al., 2021) could shield masses from micro-nutrient deficiencies and foster transition towards robust food distribution and public health systems (HLPE 2017). This could involve distribution of pre-made or ready to use packets of therapeutic foods among the impoverished sections of the society through existing schemes such as the NFSA and the ICDS (United Nations 2020). Olaimat et al., (2020) have also presented clinical evidences of probiotics boosting immunity by reducing severity of respiratory tract infections. Besides, the Ministry of AYUSH has already recommended several alternate systems (Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani and Homeopathy) based approaches for the preventive, prophylactic and symptom management of COVID-19 like illnesses, the popularization of which could be useful in boosting immunity against various respiratory ailments in general (GoI AYUSH, 2020).

On the other hand, compromised hygiene and close contact between humans and animals in wet markets has been recognized as a major factor behind zoonotic transmissions (WWF 2020). While the Health Ministry of India has issued protocols for restaurants in order to ensure safety during food consumption (GoI MoHFW, 2020), a gradual but steady shift towards Planetary Healthy Diets (increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes as opposed to red meat and sugar) could significantly reduce the future risk of virus transmissions and ensure sustainability (EAT 2019). Dietary diversification through increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes and underutilized crops within diets would lead to the dual benefits of health improvement and environment conservation (Berners-Lee et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). An ideal healthy plate comprises of 50% fruits and vegetables with the other half comprising of plant protein sources and oils as well as moderate amounts of animal proteins (EAT 2019). Existing trends favouring progress towards Planetary Healthy Diets include shifting consumption preferences in India towards fruits, vegetables and pulses subject to rising urbanisation (Goyal et al., 2017) and increase in affordability of vegetarian plate by 29% from 2006 to 07 to 2018–19 (Economic Survey, 2020a). Furethermore, utilizing available emerging UA and micro-agriculture models (vertical hydroponic farming, rooftop agriculture, office and school gardens) (Herve՜;-Gruyer 2019; Gentry 2019; Lawson 2016) for cultivation of fruits, leafy vegetables, legumes and traditional crop varieties can serve multiple benefits such as boosting food and nutritional security, promoting judicious land use, reducing ecological footprint of urban settlements and stress on agroecosystems as well as diminishing reliance on food distribution chains by localizing production systems (Dubey et al., 2021). Such innovative measures would not only lead to the propagation of Planetary Healthy Diets but also better shield communities from supply chain related disruptions which was a major concern during the present pandemic.

Lastly, initiation of a targeted approach for the influx of digital innovations and technologies within farm and food systems is significant for better linking producers and intermediaries with consumers and fostering long term resilience and sustainability (HLPE 2020; NAAS 2017; Nielsen 2020). Integration of digital (Blockchain, Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence among others) and geospatial technologies could lead to improved data synthesis regarding soil and environmental resources at the farm scale which could in turn lead to efficient crop and fertilizer management (Basso and Antle 2020; FAO 2019b). Meanwhile, since agriculture in India primarily involves a rural workforce, increasing digital literacy and skill-set combined with enhancing digital infrastructure are pre-requisites for the digital transformation of agri-food systems (Boettiger and Sanghvi 2019; FAO 2019b). Education can especially benefit women farmers by edifying them about useful agricultural practices, their rights and value of nutritious crops in household food security (HLPE 2017; Savari et al., 2020).

4. Conclusion

Provision of nutritious and sufficient food to all during times when most of the financial resources of the country are directed towards strengthening health-care facilities for tackling the pandemic is a major challenge. The challenges mainly arise owing to the existing prevalence of undernourishment, lockdown induced movement restrictions and labour shortage along-with losses during transit and storage. Addressing these concerns requires effective policy formulation and its robust implementation by the national government as well as addressing state specific concerns in the agri-food sector. Furthermore, encouraging shift towards nutritious and eco-friendly diets and encouraging interconnectedness between various stakeholders of the supply chain will promote future sustainability of food systems.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Abhilash P.C., Tripathi V., Edrisi S.A., Dubey R.K., Bakshi M., Dubey P.K., Singh H.B., Ebbs S.D. Sustainability of crop production from polluted lands. Energy, Ecology and Environment. 2016;1(1):54–65. doi: 10.1007/s40974-016-0007-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ADB . Asian Development Bank; Manilla: 2020. Asia Development Outlook Supplement 2020: Lockdown, Loosening, and Asia's Growth Prospects.https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/612261/ado-supplement-june-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- AGRICOOP . Department of Agriculture Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India; 2014. Integrated Scheme for Agricultural Marketing, Operational Guidelines.http://agricoop.nic.in/sites/default/files/finalopguidelines_0.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- AGRICOOP . Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India; 2018. Annual Report 2017-18.http://agricoop.nic.in/sites/default/files/Krishi%20AR%202017-18-1%20for%20web.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Akter S. The impact of COVID-19 related ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Security. 2020;12:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T., Murray K., A, Zambrana-Torrelio C., et al. Global hotspots and corelates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1124. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvi M., Gupta M. Learning in times of lockdown: how Covid-19 is affecting education and food security in India. Food Security. 2020;12:793–796. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amjath-Babu T.S., Krupnik T.J., Thilsted S.H., MacDonald A.J. Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Security. 2020;12:761–768. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt C., Davies R., Gabriel S., Harris L., Makrelov K., Robinson S., Levy S., Simbanegavi W., Seventer D.V., Anderson L. Covid-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security: an analysis for South Africa. Global Food Security. 2020;26:100410. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arouna A., Soullier G., del Villar P.M., Demont P. Policy options for mitigating impacts of COVID-19 on domestic rice value chains and food security in West Africa. Global Food Security. 2020;26:100405. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanlade A., Radeny M. COVID-19 and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa: implications of lockdown during agricultural planting seasons. Npj Sci Food. 2020;4:13. doi: 10.1038/s41538-020-00073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains D.S. Hindustan Times; Opinion: 2020. Managing Flood of Food-Grains Is the Nations' Problem Today.https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/managing-flood-of-foodgrains-is-the-nation-s-problem-today/story-kYLEMkb6hMsTfskvpHSI9H.html Published on: 3rd November, 2020. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji M., Arshinder K. Modelling the causes of food wastage in Indian perishable food supply chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016;114:153–167. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker M., Russell J. Feeding the food insecure in Britain: learning from the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. Food Security. 2020;12:865–870. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01080-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso B., Antle J. Digital agriculture to design sustainable agriculture systems. Nature Sustainability. 2020;3:254–256. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0510-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee M., Kennelly C., Watson R., Hewitt C.N. Current global food production is sufficient to meet human nutritional needs in 2050 provided there is radical societal adaptation. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2018;6:52. doi: 10.1525/elementa.310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P., Maity P.P., Mowrer J., Maity A., Ray M., Das S., Chakrabarti B., Ghosh T., Krishnan P. Assessment of soil health parameters and application of the sustainability index to fields under conservation agriculture for 3, 6, and 9 years in India. Heliyon. 2020;6(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavani R.V., Gopinath R. vol. 12. Springer Food Security; 2020. pp. 881–884. (The COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis and the Relevance of a Farm-System-For –nutrition Approach). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birthal P.S., Hazrana J. Crop diversification and resilience of agriculture to climatic shock: evidence from India. Agric. Syst. 2019;173:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2019.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birthal P.S., Negi D.S., Kumar S., Agarwal S., Suresh A., Khan M.T. How sensitive is Indian agriculture to climate change? Indian J. Agric. Econ. 2014;69(4):474–487. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.229948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birthal P.S., Negi D.S., Hazrana J. Trade-off between risks and farmers' choice of crops? Evidence from India. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2019;32(1):11–23. doi: 10.5958/0974-0279.2019.00002.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birthal P.S., Hazrana J., Negi D.S. Diversification in Indian agriculture towards high value crops: multilevel determinants and policy implications. Land Use Pol. 2020;91:104427. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger S., Sanghvi S. McKinsey & Company; 2019. How Digital Innovation Is Transforming Agriculture: Lessons from India.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/how-digital-innovation-is-transforming-agriculture-lessons-from-india Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Borysiak J., Mizgajski A., Speak A. Floral biodiversity of allotment gardens and its contribution to urban green infrastructure. Urban Ecosyst. 2017;20(2):323–335. doi: 10.1007/s11252-016-0595-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater P., Rotherham I.D. A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People and Nature. 2019;1:291–304. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CACP Price policy for kharif crops, the marketing season 2020-21. Commission for agricultural costs and prices, Ministry of agriculture and farmers' welfare, government of India. 2020. http://cacp.dacnet.nic.in/ViewQuestionare.aspx?Input=2&DocId=1&PageId=42&KeyId=700 Available at.

- Campbell B.M., Vermeulen S.J., Aggarwal P.K. Reducing risks to food security from climate change. Global Food Security. 2016;11:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo S., Schoen V., Specht K., et al. Applying the food-energy-water-nexus approach to urban agriculture: from FEW to FEWP (Food-Energy-Water-People) Urban For. Urban Green. 2021;58:126934. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell R., Ghazalian P.L. COVID-19 and International Food Assistance: policy proposals to keep food flowing. World Dev. 2020;135:105059. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariappa A.G., Acharya K.K., Adhav C.A., Sendhil R., Ramasundaram P. 2020. Pandemic Led Food Price Anomalies and Supply Chain Disruption: Evidence from COVID-19 Incidence in India. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaba A.A., Damodara H. The Indian Express; 2020. 2020. The Covid Nudge: Labour Shortage makes Punjab, Haryana Farmers Switch from Paddy to Cotton.https://indianexpress.com/article/india/covid-19-punjab-haryana-farmers-paddy-cotton-6385600/ (2020, April 30) [Google Scholar]

- CMIE . Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt Ltd; 2020. Consumer Sentiments Decline in November.https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-12-10%2015:11:53&msec=790 Dated 10th December, 2020. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- CMIE . Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt Ltd; 2020. Female Workforce Shrinks in Economic Shocks.https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-12-14%2012:48:29&msec=703 Dated 14th December, 2020. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Daloz A.Z., Rydsaa J., Hodnebrog Ø., et al. Direct and indirect impacts of climate change on wheat yield in the Indo-Gangetic plain in India. J. of Agriculture and Food Research. 2021:100132. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DBT . Department of Biotechnology; 2021. Annual Report 2020-2021.http://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/Final%20English%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India. Available at. Last accessed on: 01/03/2021. [Google Scholar]

- http://dbtindia.gov.in/Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India. Last accessed on: 01/03/2021.

- DFPD Annual report 2019-20. Department of food and public distribution, Ministry of consumer affairs, food and public distribution, government of India. 2020. https://dfpd.gov.in/E-Book/examples/pdf/AnnualReport.html?PTH=/1sGbO2W68mUlunCgKmpnLF5WHm/Ar2020.pdf#book/ Available at.

- Dubey P.K., Singh G.S., Abhilash P.C. Springer Nature Switzerland, Springer Brief in Environmental Science; 2019. Adaptive Agricultural Practices: Building Resilience under Changing Climate. ISBN 978-3-030-15518-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey P.K., Singh A., Raghubanshi A., Abhilash P.C. Steering the restoration of degraded agroecosystems during the united nations decade on ecosystem restoration. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;280:111798. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EAT Food planet health: healthy diets from sustainable food systems, summary report of the EAT-lancet commission. 2019. https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/01/EAT-Lancet_Commission_Summary_Report.pdf Available at.

- Economic Survey . Ministry of Finance, Government of India; 2020. Economic Survey 2019-20 Volume 1, Chapter 11: Thalinomics: The Economics of a Plate of Food in India.https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/vol1chapter/echap11_Vol1.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Survey . Ministry of finance, government of India; 2020. Economic survey 2019-20 volume 2, chapter 7: agriculture and food management.https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/vol2chapter/echap07_vol2.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Falkendal T., Otto C., Schewe J., et al. Grain export restrictions during COVID-19 risk food insecurity in many low- and middle- income countries. Nature Food. 2021;2:11–14. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Food and Agriculture Organisation; 2019. The state of food security and nutrition in the world: Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns.http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . In: Digital Technologies in Agriculture and Rural Areas: Briefing Paper by. Trendov N.M., Varas S., Zeng M., editors. Food and Agriculture Organisation; United Nations: 2019. http://www.fao.org/3/ca4887en/ca4887en.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- FAO COVID-19: channels of transmission to food and agriculture by schmidhuber, J., pound, J., qiao, B. Food and agriculture organisation, united nations. 2020. http://www.fao.org/3/ca8430en/CA8430EN.pdf Available at.

- Farias D.P., Araujo F.F. Will COVID-19 affect food supply in distribution centres of Brazilian regions affected by the pandemic? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Folke C., Carpenter S.R., Walker B., Scheffer F., Chapin T., Rockstorm J. Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010;15(4):20. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/ [Google Scholar]

- FSIN . Food Security Information Network; 2020. 2020 Global Report on Food Crisis: Joint Analysis for Better Decisions.https://www.wfp.org/publications/2020-global-report-food-crises Global Network against Food Crisis. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis C.M. The food systems in the era of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic crisis. MDPI Foods. 2020;9:523. doi: 10.3390/foods9040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett P., Doherty B., Heron T. Vulnerability of United Kingdom's food supply chains exposed by COVID-19. Nature Food. 2020;1:315–318. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin R., Harrison L., Plotkin C.L., Spillecke D., Stanley J. Mckinsey and Company; 2020. The B2B Digital Inflection Point: How Sales Have Changes during COVID-19.https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/the-b2b-digital-inflection-point-how-sales-have-changed-during-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Gazette of India The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020. Published on: 27/09/2020. Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 2020. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2020/222038.pdf Available at.

- Gazette of India The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020. Published on: 27/09/2020. Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 2020. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2020/222040.pdf Available at.

- Gazette of India The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020. Published on: 27/09/2020.Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 2020. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2020/222039.pdf Available at.

- Gentry M. Local heat, local food: integrating vertical hydroponic farming with district heating in Sweden. Energy. 2019;174:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.02.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George N.A., McKay F.H. The public distribution system and food security in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16:3221. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GoI AYUSH Advisory from the Ministry of AYUSH for meeting the challenge arising out of spread of corona virus (COVID-19) in India. Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, sowa-rigpa and Homeopathy, government of India. 2020. https://www.ayush.gov.in/docs/125.pdf Available at.

- GoI MAFW Agriculture statistics at a glance 2019. Ministry of agriculture and farmers' welfare, department of agriculture, cooperation and farmers welfare, government of India. 2020. https://eands.dacnet.nic.in/PDF/At%20a%20Glance%202019%20Eng.pdf Available at.

- GoI MOFPI Mega food parks scheme (MFPS) guidelines. 2012. https://mofpi.nic.in/sites/default/files/consolidated_guidelines_mfps_011012_0_0.pdf Available at.

- GoI MOFPI Annual report 2019-20. Ministry of food processing Industries, government of India. 2020. https://mofpi.nic.in/sites/default/files/english_2019-20_1.pdf Available at.

- GoI MOFPI F.No.M-15/1/2018-MFP. Amendment in operation guidelines for the scheme for “operation greens”, dated 04/03/2021. 2021. https://mofpi.nic.in/sites/default/files/5th_amendement_sg_0.pdf Available at.

- GoI MoHFW SOP on preventive measures in restaurants to contain spread of COVID-19. Posted on: 04/06/2020, Ministry of health and family welfare, government of India. 2020. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/3SoPstobefollowedinRestaurants.pdf Available at.

- GoI MOSPI Sustainable development goals national indicator framework progress report 2020 (version 2.1). Ministry of statistics and programme implementation, government of India. 2020. http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/SDGProgressReport2020.pdf Available at.

- GoI NSSO Household Consumption of Various Goods and Services in India 2011-12, NSS 68th round. National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. 2014. http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Report_no558_rou68_30june14.pdf Available at.

- GoI NSSO Nutritional Intake in India, 2011-12. NSS 68th round, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, National Statistical Organisation, National Sample Survey Office, Government of India. 2014. http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/nss_report_560_19dec14.pdf Available at.

- Gopalan H.S., Misra A. COVID-19 pandemic and challenges for socio-economic issues, healthcare and National Health Programs in India. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clin. Res. Rev. 2020;14(5):757–759. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Rajagopalan C., Goedde L., Nathani N. McKinsey & Company, Inc; 2017. Harvesting Golden Opportunities in Indian Agriculture: from Food Security to Farmers' Income by 2025.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/harvesting-golden-opportunities-in-indian-agriculture Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Hajra R., Ghosh T. Agricultural productivity, household poverty and migration in the Indian Sundarban Delta. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2018;6:3. doi: 10.1525/elementa.196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J., Depenbusch L., Pal A.A., Nair R.M., Ramasamy S. Food system disruption: initial livelihood and dietary effects of COVID-19 on vegetable producers in India. Food Security. 2020;12:841–851. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01064-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey D., Heidkamp R., Osendarp S., et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):519–521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31647-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé-Gruyer C. Permaculture and bio-intensive micro-agriculture: the Bec Hellouin farm model. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2019;20:74–77. https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5748 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Hidrobo M., Kumar N., Palermo T., Peterman A., Roy S. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Brief; 2020. Gender-sensitive social protection. A critical component of the COVID-19 response in low- and middle-income countries.https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133701/filename/133912.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems. A report by the high level panel of Experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security, rome. 2014. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3901e.pdf Available at.

- HLPE Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of Experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security, rome. 2017. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7846e.pdf Available at.

- HLPE Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the high level panel of Experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security, rome. 2020. http://www.fao.org/3/ca9733en/ca9733en.pdf Available at.

- Holland C., Rammohan A. Rural women's empowerment and children's food and nutrition security in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2019;124:104648. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huss M., Brander M., Kassie M., Ehlert U., Bernauer T. Improved storage mitigates vulnerability to food supply shocks in smallholder agriculture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Food Security. 2021;28:100468. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPES-Food COVID-19 and the crisis in food systems: symptoms, causes and potential solutions. International panel of Experts on sustainable food systems. 2020. http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/COVID-19_CommuniqueEN.pdf Available at.

- Ismail A., Riaz M., Akhtar S., Ismail T., Amir M., Zafar-ul-Hye M. Heavy metals in vegetables and respective soils irrigated by canal, municipal waste and tube well water. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2014;7(3):213–219. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2014.888783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Singh S.S., Pandey A.K., Singh R.K., Srivastava P.K., Kumar M., Dubay S.K., Sah U., Nandan R., Singh S.K., Agrawal P., Kushwaha A., Rani M., Biswas J.K., Drews M. Multi-level impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on agricultural systems in India: the case of Uttar Pradesh. Agric. Syst. 2021;187:103027. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu A. Lockdown, containing COVID-19 and dealing with interstate migrants. RIS Diary. 2020;16(2):5–6. https://www.ris.org.in/sites/default/files/RIS_Diary%20Covid%2019_0.pdf Special Issue on COVID-19 (April 2020) Research and Information System for Developing Countries. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde D., Martin W., Swinnen J., Vos R. COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science. 2020;369(6503):500–502. doi: 10.1126/science.abc4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S., Pham G., Nguyen-Viet H. Emerging health risks from agricultural intensification in South East Asia: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 2017;23(3):250–260. doi: 10.1080/10773525.2018.1450923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langemeyer J., Madrid-Lopez C., Beltran A.M., Mendez G.V. Urban agriculture- A necessary pathway towards urban resilience and global sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plann. 2021;210:104055. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson L. Agriculture: sowing the city. Nature. 2016;540:522–523. doi: 10.1038/540522a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele U., Bansal S., Meenakshet J.V. Health and nutrition of India's labour force and COVID-19 challenges. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2020;55(21) [Google Scholar]

- Leyva A., Iores A. Accessing agroecosystem sustainability in Cuba: a new agrobiodiversity index. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2018;6:80. doi: 10.1525/elementa.336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loh J., Harmon D. A global index of biocultural diversity. Ecol. Indicat. 2005;5(3):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton M., Truskett R., Scarf B., Sindone L., Baldry G., Zhao Y. Consumer behaviour during crises: preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020;13(8):166. doi: 10.3390/jrfm13080166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra R. Bumper kharif amid excess stock? Is India staring at hard agri decisions. Down To Earth: Agriculture. 2020. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/bumper-kharif-amid-excess-stock-is-india-staring-at-hard-agri-decisions-73491 Published 22nd September, 2020. Available at.

- Marco M.D., Baker M.L., Daszak P., et al. Opinion: sustainable development must account for pandemic risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2020;117(8):3888–3892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001655117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee P., Turnout E., Chiroleu-Assouline M., et al. Ensuring a post-COVID economic agenda tackles global biodiversity loss. One Earth. 2020;3(4):448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenakshi J.V., Banerji A. The unsupportable support price: an analysis of collusion and government intervention in paddy auction markets in north India. J. Dev. Econ. 2005;76(2):377–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meers E., Van Slycken S., Adriaensen K., et al. The use of bioenergy crops (Zea mays) for ‘‘phytoattenuation’’ of heavy metals on moderately contaminated soils: a field experiment. Chemosphere. 2010;78:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 24th March, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHAorder%20copy_0.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI Annexure to ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 24th March, 2020.Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/Guidelines_0.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A), dated 15th April, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHA%20order%20dt%2015.04.2020%2C%20with%20Revised%20Consolidated%20Guidelines_compressed%20%283%29.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 1st may, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHA%20Order%20Dt.%201.5.2020%20to%20extend%20Lockdown%20period%20for%202%20weeks%20w.e.f.%204.5.2020%20with%20new%20guidelines.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A), dated 30th may, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHAOrderDt_30052020.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 29th June, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHAOrder_29062020.pdf Available at.

- MHA GoI ORDER No. 40-3/2020-DM-I(A), dated 29th July, 2020. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2020. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unlock3_29072020.pdf Available at.

- Mishra D., Chanchani M. 2020. Kirana supplying B2B companies see orders rise by 60%. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/kirana-supplying-b2b-cos-see-orders-rise-60/articleshow/75089203.cms Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra K., Rampal J. The COVID-19 pandemic and food insecurity: a viewpoint on India. World Dev. 2020;135:105068. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R., Chaulya S.K., Prasad G.M., Mandal S.K., Banerjee G. Design of a low cost, smart and stand-alone PV cold storage system using a domestic split air conditioner. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020;89:101720. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2020.101720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M., Goldsworthy N., Roth A., Gonzalez-Avram C. Unique in-school garden and nutrition intervention improves vegetable preference and food literacy in two independently conducted evaluations (P16-040-19) Current Developments in Nutrition. 2019;3(1) doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz050.p16-040-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Yadav D.S., Agrawal S.B., Agrawal M. Ozone a persistent challenge to food security in India: current status and policy implications. Current Opinion in Env Sc and Health. 2021;19:100220. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]