Abstract

Objectives:

While there is growing evidence of an association between depressive symptoms and postoperative delirium, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain unknown. The goal of this study was to explore the association between depression and postoperative delirium in hip fracture patients, and to examine Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology as a potential underlying mechanism linking depressive symptoms and delirium.

Methods:

Patients 65 years old or older (N = 199) who were undergoing hip fracture repair and enrolled in the study “A Strategy to Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients” completed the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) preoperatively. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was obtained during spinal anesthesia and assayed for amyloid-beta (Aβ) 40, 42, total tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated tau (p-tau)181.

Results:

For every one point increase in GDS-15, there was a 13% increase in odds of postoperative delirium, adjusted for baseline cognition (MMSE), age, sex, race, education and CSF AD biomarkers (OR = 1.13, 95%CI = 1.02–1.25). Both CSF A 42/t-tau (β = −1.52, 95%CI = −2.1 to −0.05) and A 42/p-tau181 (β = −0.29, 95%CI = −0.48 to −0.09) were inversely associated with higher GDS-15 scores, where lower ratios indicate greater AD pathology. In an analysis to identify the strongest predictors of delirium out of 18 variables, GDS-15 had the highest classification accuracy for postoperative delirium and was a stronger predictor of delirium than both cognition and AD biomarkers.

Conclusions:

In older adults undergoing hip fracture repair, depressive symptoms were associated with underlying AD pathology and postoperative delirium. Mild baseline depressive symptoms were the strongest predictor of postoperative delirium, and may represent a dementia prodrome

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, delirium, csf, amyloid, tau, depression, mild behavioral impairment, hip fracture, postoperative

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a syndrome defined by acute changes in attention and cognition1 that commonly occurs in hospitalized older adults after acute illness or surgery. Delirium is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, longer hospital stays, as well as physical and cognitive decline.2 The estimated annual health care costs associated with delirium and its downstream effects are over $164 billion dollars in the United States.3 Although delirium occurs in various clinical settings, the risk is especially high among older adults undergoing hip fracture surgery, with incidences ranging from 13% to 56%.4 In hip fracture studies with active screening, delirium is one of the most common postoperative complications, more common than urinary tract infection or pneumonia in some studies.5

Risk factors for postoperative delirium include cognitive impairment, older age, medical comorbidities, and neuropsychiatric conditions including depression.4,6 Associations between preoperative depression and postoperative delirium have been reported extensively in cardiac surgery populations.7 Similar associations have been reported in patients undergoing hip surgery.8–10 The latter studies, however, have been limited to clinically significant depression. Findings have been mixed in studies examining the association between mild depressive symptoms and postoperative delirium with reports that show positive11,12 or no association.13

While there is growing evidence of an association between depression and postoperative delirium, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this association and whether this association is driven by a common etiology remains unknown. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a risk factor for postoperative delirium, depression and other neuropsychiatric symptoms have been the focus of growing interest as early manifestations or prodromal symptoms of an underlying neurodegenerative disease process.14 Biomarkers of AD have been examined in relation to depression15,16 and to delirium,17–20 with mixed results. The goal of our study was to 1) explore the association between depression and postoperative delirium in a hip fracture population, and 2) to examine AD pathology as a potential mechanism accounting for associations between depressive symptoms and delirium.

METHODS

Participants

We analyzed data from a cohort of 199 consecutive hip fracture patients enrolled in the randomized clinical trial “A Strategy to Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients” (STRIDE) study who completed the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15)21 preoperatively. Details of STRIDE have been published elsewhere.22,23 Briefly, individuals ≥65 years old with a preoperative Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)24 score ≥15 who were undergoing emergency hip fracture repair with spinal anesthesia were included. Exclusion criteria included preoperative delirium, stage IV congestive heart failure, or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Informed consent was obtained from patients or legal representatives for patients unable to give informed consent. The trial was approved by a Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Study Procedures

Baseline demographic data were collected from patients, informants, and medical records by trained research staff prior to surgery. MMSE and GDS-15 were administered by research staff prior to surgery. GDS-15 is a 15-question screening tool designed to assess depressive symptoms in older adults; a score >5 is often used as a cut-off for major depressive disorder.25 A consensus panel of two psychiatrists and one geriatrician blinded to the intervention scored the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), which is a modification of the previously published CDR (Morris et al., 1993; Oh et al., 2018). The CDR scoring was based on assessment of all available clinical cognitive data, the Short Form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (Short IQCODE)28 and other history collected from the patient and informant prior to surgery. A global score of 0 represents normal cognition, while scores of 1, 2, and 3 represent mild, moderate or severe dementia respectively. Medical comorbidities were quantified using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).29 Other baseline assessments included American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, fracture type, activities of daily living (ADL) scale, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale.

Procedures for CSF collection have been described in detail.27 Briefly, CSF was collected at the onset of routine spinal anesthesia. CSF samples were analyzed for amyloid-beta (A ) 40, A 42, total tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated tau (p-tau)181 at the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory of the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden. A 40 and A 42 were assayed using MSD electrochemiluminescence assay (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, USA), and t-tau and p-tau181 were assayed using INNOTEST enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium) according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

Postoperative delirium was diagnosed by a consensus diagnosis panel of experts from postoperative day 1 to 5 or hospital discharge. The diagnosis of delirium was made by a multidisciplinary consensus panel based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria using several data sources, including the confusion assessment method,30 the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R98),31 digit span, a review of medical records, and family/nursing staff interviews. Study team members involved in assessing delirium were blinded to GDS-15 scores.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographics were compared using Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for dichotomous variables and student t tests for continuous variables. Logistic regression models were estimated to examine associations between baseline GDS-15 score and incident postoperative delirium.

The association between GDS-15 and postoperative delirium was assessed using a series of 4 logistic regression models. Model 1 contained a regression equation for GDS-15 with incident postoperative delirium as the dependent variable. Model 2 added demographics (age, sex, race, and education), model 3 added baseline clinical measures (CCI and MMSE), and model 4 added CSF biomarkers of AD (A 42/p-tau181 ratio) to the equation (n = 151). A 42/p-tau181 ratio was selected over other CSF biomarkers due to its higher specificity for AD 32 and association with baseline depression in our own analysis (Table 1). Low A 42/p-tau181 ratios are found in individuals with clinical AD diagnosis.32 We also examined whether baseline CSF AD biomarkers were associated with depressive symptoms. Linear regression models were estimated to examine the association between baseline depressive symptoms and baseline CSF A 40, A 42, t-tau, p-tau181, A 42/t-tau, and A 42/p-tau181 in a subset of patients with available CSF data (n = 151). Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and Charlson comorbidity score (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Depression Status

| Characteristics | Total(N = 199) | GDS-15 ≤5(n = 169) | GDS-15 >5(n = 30) | X2 (df)/t(df) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 81.9 (7.7) | 81.7 (7.6) | 82.8 (8.3) | t197 = −0.70 | 0.49 |

| Female, No. (%) | 145 (72.9) | 123 (72.8) | 22 (73.3) | X21 = 0.004 | 0.95 |

| Race, White, No. (%) | 193 (97.0) | 164 (97.0) | 29 (96.7) | X21 = 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Education level, No. (%) | Fisher Exact | 0.27 | |||

| Less than high school | 76 (38.2) | 63 (37.3) | 13 (43.3) | ||

| High school | 76 (38.2) | 62 (36.7) | 14 (46.7) | ||

| Some college | 28 (14.1) | 26 (15.4) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| College or higher | 19 (9.5) | 18 (10.7) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.49 (1.73) | 1.49 (1.77) | 1.63 (1.73) | t197 = −0.41 | 0.68 |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 24.3 (3.68) | 24.5 (3.50) | 23.1 (4.52) | t197 = 1.98 | 0.05 |

| CDR-SB, mean (SD) | 1.47 (2.53) | 1.36 (2.47) | 2.19 (2.79) | t195 = −1.64 | 0.10 |

| CDR-Global, N. (%) | Fisher Exact | .20 | |||

| 0 | 81 (41.1) | 72 (42.9) | 9 (31.0) | ||

| 0.5 | 94 (47.7) | 80 (47.6) | 14 (48.3) | ||

| 1 | 16 (8.1) | 12(7.1) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| 2 | 6 (3.1) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (6.9) | ||

| CSF biomarkers, mean (SD) | |||||

| A 40 (pg/ml) | 5044.47 (1794.82) | 5084.02 (1836.82) | 4834.98 (1567.81) | t168 = 0.66 | 0.51 |

| A 42 (pg/ml) | 297.71 (162.19) | 304.05 (169.20) | 264.13 (115.04) | t168 = 1.17 | 0.24 |

| t-tau (pg/ml) | 495.30 (281.34) | 492.41 (292.70) | 510.60 (215.17) | t168 = −0.31 | 0.76 |

| p-tau (pg/ml) | 56.92 (25.36) | 55.74 (25.80) | 63.11 (22.33) | t167 = −1.39 | 0.17 |

| A 42/A 40 a | 0.58 (0.20) | 0.59 (0.20) | 0.56 (0.19) | t168 = 0.84 | 0.40 |

| A 42/t-tau | 0.71 (0.38) | 0.73 (0.38) | 0.60 (0.34) | t168 = 1.70 | 0.09 |

| A 42/p-tau181 | 5.73 (2.81) | 5.96 (2.88) | 4.50 (2.03) | t167 = 2.51 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; Aβ42, amyloid-beta 1–42; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes score (modified);27,48 CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GDS-15, Geriatrics Depression Scale-15 (short form)21 (15 items, max. score = 15 points; higher score = worse depression; cutoff score of >5 for depression); MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination24 (10 items, max. score = 30 points); No., Number; p-tau181, phosphorylated tau181; t-tau, total tau.

Baseline demographics were compared using Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for dichotomous variables and student t for continuous variables.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Linear Regression Models Examining the Association Between Baseline Continuous GDS-15 With CSF Biomarkers

| CSF Biomarkers | Estimate 95% CI) | t-Value | df | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| A 40 | −2.69 × 10−4 b | |||

| (−5.57 × 10−4, 3.69 × 10−5) | −1.74 | 163 | 0.08a | |

| A 42 | 2.89 × 10−3 b | |||

| (−6.30 × 10−3, 5.17 × 10−4) | −1.68 | 163 | 0.10a | |

| t-tau | 2.02 × 10−4 b | |||

| (−1.76 × 10−3, 2.16 × 10−3) | 0.20 | 163 | 0.84a | |

| p-tau181 | 0.01b | |||

| (−0.12-0.03) | 0.93 | 162 | 0.36a | |

| A 42/t-tau | −1.52 | |||

| (−2.10, −0.05) | −2.04 | 163 | 0.04 | |

| A 42/p-tau181 | −0.29 | |||

| (−0.48, −0.09) | −2.91 | 162 | 0.004 | |

p Value calculated by linear regression, adjusted for age, sex, race, education and Charlson comorbidity index. Change in CSF biomarker (pg/mL) per 1 point increase in GDS-15. Abbreviations: Aβ40, amyloid-beta 1–40; Aβ42, amyloid-beta 1–42; CI, Confidence Interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GDS-15, Geriatrics Depression Scale-15 (short form);21 p-tau181, phosphorylated tau181; t-tau, total tau.

On an exploratory basis, using machine learning program, KappaTree,33 an R adaptation of ROC4, a public domain program (http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/ROC.html), we conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses and computed weighted kappas to identify predictors of delirium out of a list of 18 variables (below). The KappaTree program implements a form of recursive partitioning in that it cycles through each possible cutoff of each candidate predictor variable and iteratively branches on the best cutoff for the best variable at each node as a function of weighted kappa. In our application, sensitivity and specificity were equally weighted, the program was constrained such that once a variable had been branched on, it would not branch on that same variable again. Variables considered: age, sex, race, education, MMSE, GDS-15 (continuous and dichotomized at ≤5 versus >5), CCI, vascular index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, activities of daily living (ADL) scale, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale, fracture type, APOE status, CDR global score, CDR-SB, A 42/t-tau, and A 42/p-tau181 ratio.

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA 16 software34 and R package KappaTree.35 Significance was set at two-sided p <0.05.

RESULTS

To assess for associations of depression with baseline variables, we compared those with more severe symptoms defined by GDS-15 >5 to those with GDS-15 ≤5 (Table 1). The two groups did not differ significantly on demographics. There were also no differences in baseline CSF A 40, A 42, t-tau, p-tau181, or A 42/t-tau with the exception of lower A 42/ptau181 ratios in the depressed group (Table 1). Seventy three (37%) of the overall cohort developed postoperative delirium. A greater proportion of those with GDS-15 >5 developed delirium compared to those with GDS-15 ≤5 (53.3 % versus 34.7%, Chi-square test: X2 = 4.22, df = 1, p = 0.04).

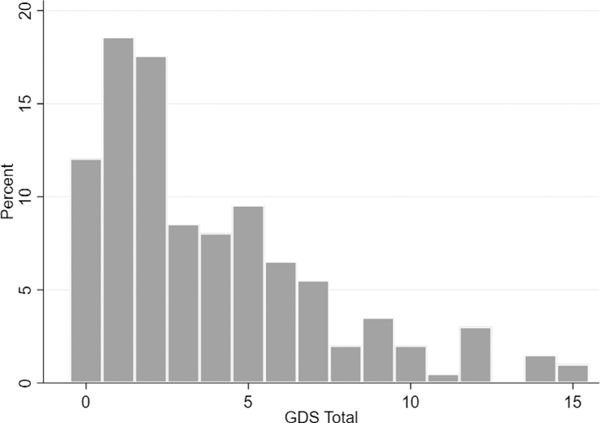

The distribution of GDS-15 scores across the cohort is in Figure 1. Both CSF A 42/t-tau and A 42/p-tau181 ratios were inversely associated with higher GDS-15 scores (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15) scores. GDS-15 >5 is clinically significant depression.25

Table 3 displays odds of incident postoperative delirium in relation to baseline characteristics. Higher GDS-15 and lower MMSE scores were associated with greater odds of postoperative delirium, even after adjusting for demographics, medical comorbidity, and AD biomarkers. Age, sex, race, education, CCI, CSF Aβ1–42/p-tau181 were not associated with odds of developing postoperative delirium. In a separate model with Aβ1–42/t-tau in lieu of Aβ1–42/p-tau181, Aβ1–42/t-tau was also not associated with odds of developing post-operative delirium (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model of Incident Postoperative Delirium in Relation to Baseline Characteristics

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| OR 95% CI | z | p Value | OR 95% CI | z | p Value | OR 95% CI | z | p Value | OR | z | p Value | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| GDS-15 | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) |

3.50 | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.06−1.28) |

3.32 | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.05−1.26) |

2.95 | 0.003 | 1.13 (1.02−1.25) |

2.43 | 0.02 |

| Age | - | - | - | 1.06 (1.01−1.10) |

2.52 | 0.01 | 1.04 (0.10−1.09) |

1.75 | 0.08 | 1.05 (0.99−1.10) |

1.91 | 0.06 |

| Female | - | - | - | 0.83 (0.42−1.64) |

−0.54 | 0.59 | 1.06 (0.51−2.18) |

0.15 | 0.88 | 1.08 (0.47−2.47) |

0.19 | 0.85 |

| Race | - | - | - | 4.17 (0.37−47.42) |

1.15 | 0.25 | 5.78 (0.49−1.66) |

1.39 | 0.16 | 6.49 (0.49−86.69) |

1.41 | 0.16 |

| Education level | - | - | - | 0.95 (0.46−1.96) |

−0.13 | 0.90 | 0.78 (0.36−1.66) |

−0.65 | 0.51 | 0.76 (0.34−1.17) |

−0.66 | 0.51 |

| CCI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.12 (0.93−1.34) |

1.21 | 0.23 | 1.11 (0.90−1.36) |

0.97 | 0.33 |

| MMSE | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.88 (0.79−0.97) |

−2.65 | 0.008 | 0.86 (0.77−0.96) |

−2.73 | 0.006 |

| A 42/p-tau181 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.01 (0.89−1.15) |

0.14 | 0.89 |

Model 1 contains univariable regression for GDS-15 and delirium. Model 2 adds demographic variables. Model 3 adds MMSE and CCI variables. Model 4 adds the CSF A 42/p-tau181 variable. Z and p values calculated by linear regression, adjusted for covariates as indicated for each model.

Abbreviations: Aβ42/p-tau181 = CSF amyloid-beta 1–42 to phosphorylated tau181 ratio; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index;29 CI, Confidence Interval; Geriatrics Depression Scale-15 (short form)21 (15 items, max. score = 15 points; higher score = worse depression; cut-off score of >5 for depression); MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination24 (10 items, max. score = 30 points).

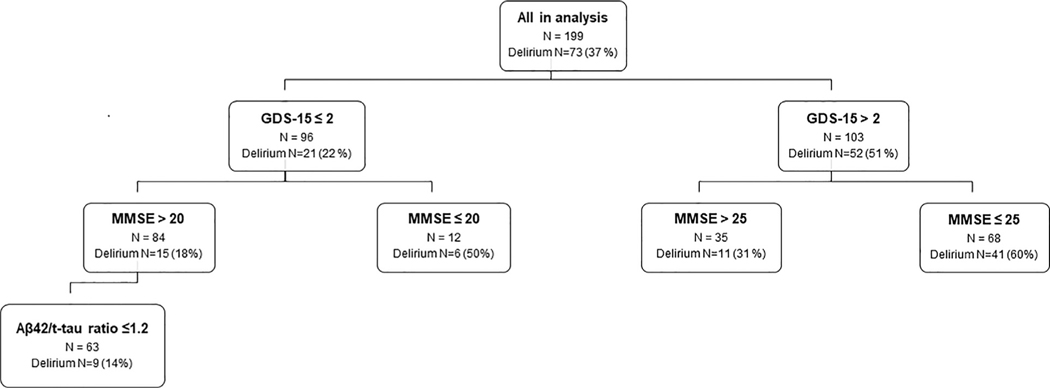

In KappaTree analyses (Fig. 2), out of 18 factors, GDS-15 had the highest classification accuracy for delirium (Kappa = 0.28). Fifty-two patients (71%) among those who developed delirium had pre-operative GDS >2. In the GDS-15 >2 group who developed delirium, 41 (78%) had MMSE ≤25. Six (29%) individuals who developed delirium and had GDS-15 ≤2 also had MMSE ≤20. In those with GDS-15 ≤2 and MMSE >20 who developed delirium, 9 (60%) had Aβ1–42/t-tau ratio ≤1.2. Thus, of those who developed delirium 41 (56%) had mild or more severe depressive symptoms plus cognitive impairment, 11 (15%) had at least mild depression, 9 (12%) had abnormal CSF but neither depression nor cognitive impairment, and another 6 (8%) had cognitive impairment alone.

FIGURE 2.

KappaTree analysis. Using receiver operating characteristic analyses and computation of weighted kappa, KappaTree analysis was used to identify factors with the highest classification accuracy for delirium. Abbreviations: Aβ42/t-tau= CSF β-amyloid 1–42 to total tau ratio; GDS-15, Geriatrics Depression Scale-15 (short form)21 (15 items, max. score = 15 points; higher score = worse depression; cut-off score of >5 for depression); MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination24 (10 items, max. score = 30 points.

DISCUSSION

In this study of older adults who presented with hip fracture requiring surgery, higher GDS-15 scores were associated with greater odds of postoperative delirium, even after adjusting for baseline cognitive function, age, sex, race, education and CSF AD biomarkers. Additionally, findings from KappaTree analysis suggest that the presence of even mild depressive symptoms (with an optimal cutoff of GDS-15 >2) is a strong predictor of postoperative delirium, beyond both cognition (measured by MMSE) and AD biomarkers (CSF A 42/t-tau). Taken together, these findings suggest that depressive symptoms, even at a low severity, may be a useful predictor of postoperative delirium in hip fracture patients.

Our findings build on previous studies examining the relationship between depression and postoperative delirium in the hip fracture population that have found significant associations between depression8,9 or clinically significant depressive symptoms10 and postoperative delirium. Postoperative delirium has also been identified as a risk factor for depression following hip fracture.36 The latter studies focused only on clinical depression as opposed to mild depressive symptoms, which have been of increasing interest in the field of AD and are far more prevalent in outpatient populations.

Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI) is a construct that describes a syndrome of late-life neuropsychiatric symptoms of any severity, including depression, not attributable to another current psychiatric disorder, occurring with or without concurrent Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).14 Late-life mild depressive symptoms, a form of MBI, are risk factors for progression to MCI or all-cause dementia.37–40 Hence, depressive symptoms in late-life may represent early noncognitive manifestations of dementia with a shared neurodegenerative etiology. This is supported by our finding that even very mild depressive symptoms predicted post-operative delirium, while increasing severity of depressive symptoms was inversely associated with both CSF A 42/t-tau and A 42/p-tau181 ratios, patterns suggestive of brain AD pathology.41 Thus, we propose that mild depressive symptoms can be a dementia prodrome that place older adults at risk for delirium after a hip fracture.

In examining the relationship between AD CSF biomarkers and delirium, our findings were mixed. These biomarkers were not associated with postoperative delirium after adjusting for covariates but were a stronger predictor of delirium than most other patient characteristics in the KappaTree analysis. In a study of hip fracture patients that excluded individuals with dementia, no association between baseline CSF Aβ42, tau or p-tau levels and postoperative delirium was observed.19 In another study of hip fracture patients with and without dementia, CSF Aβ42, t-tau, Aβ40/t-tau and Aβ42/p-tau (but not p-tau) were associated with postoperative delirium after adjusting for age, sex, and premorbid cognition.18 In individuals with dementia, however, CSF biomarker levels did not differ between those with and without delirium. In studies of elective hip and knee surgery patients, postoperative delirium has been associated with low CSF Aβ42,17 Aβ40/t-tau and Aβ42/p-tau ratios.17,20 Some of these differences may be accounted for by the significantly older age of hip fracture versus elective orthopedic patients, as well as by variability of brain pathology across study populations. Even though AD brain pathology is highly prevalent in older adults 65 and older,42 with increasing age other neuropathological processes become common.44 Based on our findings we propose an additional reason for the mixed associations between CSF biomarkers, cognition, and delirium: the presence or absence of noncognitive manifestations of AD and other neurodegenerative disease (MBI), in this case depressive symptoms. Fifty-two of 73 (71%) of patients who developed delirium had mild or more severe depression. Added together the presence of MBI (depression), cognitive impairment (MMSE ≤20), or abnormal CSF AD biomarkers accounted for 67/73 (92%) cases of delirium.

Strengths of this study include examination of CSF AD biomarker profile in a relatively large, well-characterized cohort of hip fracture patients. In addition, GDS-15 was completed before surgery, and would not have been influenced by symptoms of delirium as individuals with preoperative delirium were excluded from the study. Our study should, however, be interpreted within the context of its limitations. This was a relatively small secondary analysis of a single-site clinical trial, which may limit findings to individuals motivated to participate in a clinical trial. Patients on oral anticoagulants and congestive heart failure were excluded, which may have excluded individuals with cognitive deficits related to vascular causes. Our findings, therefore, may not be generalizable to older patients with hip fracture and significant cardiovascular disease. Further study is required in this subpopulation. The GDS-15 has been validated for assessment of depression in mild-to-moderate dementia, with good correlation45 to the Cornell Scale of Depression in Dementia,46 and diagnosis of depression using DSM-IV criteria.47 While it has not been validated in severe dementia, our cohort consisted only of 6 participants with severe dementia (CDR = 2). Future studies should also assess for neuropsychiatric symptoms outside of depression.

In summary, we found that in older individuals undergoing surgery for traumatic hip fracture, baseline depressive symptoms (a form of MBI) were the strongest predictor of postoperative delirium, and that symptoms of depression were associated with underlying AD pathology. Assessment for depressive symptoms may be a useful addition to the standard clinical assessment in identifying individuals at risk of postoperative delirium.

Acknowledgments

UNCITED REFERENCES

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards for Denali, Roche Diagnostics, Wave, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Pinteon Therapeutics and CogRx, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Fujirebio, Alzecure and Biogen, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. KB reports serving as a consultant, at advisory boards, or at data monitoring committees for Abcam, Axon, Biogen, JOMDD/Shimadzu. Julius Clinical, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. CL is a consultant for Astellas, Roche, Karuna, SVB Leerink, Maplight, Axsome, and has a research grant from Functional Neuromodulation Ltd, outside the submitted work.

Research reported in this publication was supported by 5KL2RR025006 [Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number UL1 TR 001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)] (EO, NW), K23AG043504 (NIA/NIH) (EO), R01AG057725 (NIA/NIH) (EO), R01 AG033615 (NIA/NIH) (FS, KN, NW), P50 AG005146 (CL), R24AG054259 (NIA/NIH) (SKI), P01AG031720 (NIA/NIH) (SKI), K24AG035075 (ERM), and the Roberts Gift Fund (EO). Hjärnfonden, Sweden, #FO2017–0243 (KB), Swedish Research Council #2017–00915 (KB), Swedish and European Research Councils (HZ), UK Dementia Research Institute (HZ), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (HZ), and Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement #ALFGBG-715986 (KB). HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

This study was supported by 5KL2RR025006 [Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number UL1 TR 001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)] (EO), K23AG043504 (NIA/NIH) (EO, NW), R01AG057725 (EO), R01 AG033615 (NIA/NIH) (FS, KN, NW), P50 AG005146 (CL), R24AG054259 (NIA/NIH) (SKI), K24AG035075 (ERM), P01AG031720 (NIA/NIH) (SKI), and the Roberts Gift Fund (EO). Hjärnfonden, Sweden, #FO2017–0243 (KB), Swedish Research Council #2017–00915 (KB), Swedish and European Research Councils (HZ), UK Dementia Research Institute (HZ), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (HZ), and Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement #ALFGBG-715986 (KB). HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS: Delirium in elderly people. Lancet Lond Engl 2014; 383:911–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. : One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh ES, Li M, Fafowora TM, et al. : Preoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium following hip fracture repair: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30:900–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flikweert ER, Wendt KW, Diercks RL, et al. : Complications after hip fracture surgery: are they preventable? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg Off Publ Eur Trauma Soc 2018; 44:573–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenning KJ, Deiner SG: Postoperative delirium in the geriatric patient. Anesthesiol Clin 2015; 33:505–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sockalingam S, Parekh N, Bogoch II, et al. : Delirium in the postoperative cardiac patient: a review. J Card Surg 2005; 20:560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berggren D, Gustafson Y, Eriksson B, et al. : Postoperative confusion after anesthesia in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures. Anesth Analg 1987; 66:497–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edlund A, Lundström M, Lundström G, et al. : Clinical profile of delirium in patients treated for femoral neck fractures. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10:325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galanakis P, Bickel H, Gradinger R, et al. : Acute confusional state in the elderly following hip surgery: incidence, risk factors and complications. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benoit AG, Campbell BI, Tanner JR, et al. : Risk factors and prevalence of perioperative cognitive dysfunction in abdominal aneurysm patients. J Vasc Surg 2005; 42:884–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider F, Böhner H, Habel U, et al. : Risk factors for postoperative delirium in vascular surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24:28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryson GL, Wyand A, Wozny D, et al. : A prospective cohort study evaluating associations among delirium, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and apolipoprotein E genotype following open aortic repair. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth 2011; 58:246–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, et al. : Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 12:195–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.do Silva KP, Malloy-Diniz LF, et al. : Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β levels in late-life depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2015; 69:35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EE, Iwata Y, Chung JK, et al. : Tau in late-life depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 54:615–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham EL, McGuinness B, McAuley DF, et al. : CSF beta-amyloid 1–42 concentration predicts delirium following elective arthroplasty surgery in an observational cohort study. Ann Surg 2019; 269:1200–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idland A-V, Wyller TB, Støen R, et al. : Preclinical amyloid-β and axonal degeneration pathology in delirium. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 55:371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witlox J, Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, et al. : Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid and tau are not associated with risk of delirium: a prospective cohort study in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:1260–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Z, Swain CA, Ward SA, et al. : Preoperative cerebrospinal fluid β-Amyloid/Tau ratio and postoperative delirium. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2014; 1:319–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol J Aging Ment Health 1986

- 22.Li T, Wieland LS, Oh E, et al. : Design considerations of a randomized controlled trial of sedation level during hip fracture repair surgery: a strategy to reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients. Clin Trials 2017; 14:299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sieber FE, Neufeld KJ, Gottschalk A, et al. : Effect of Depth of sedation in older patients undergoing hip fracture repair on postoperative delirium: The STRIDE Randomized Clinical. Trial JAMA Surg 2018; 153:987–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pocklington C, Gilbody S, Manea L, et al. : The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 31:837–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris JC: The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Oh ES, Blennow K, Bigelow GE, et al. : Abnormal CSF amyloid-β42 and tau levels in hip fracture patients without dementia. PloS One 2018; 13:e0204695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorm A, Jacomb P: The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med 1989; 19:1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. : A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. : Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, et al. : Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skillbäck T, Farahmand BY, Rosén C, et al. : Cerebrospinal fluid tau and amyloid-β1–42 in patients with dementia. Brain 2015; 138:2716–2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petras H, Buckley JA, Leoutsakos J-MS, et al. : The use of multiple versus single assessment time points to improve screening accuracy in identifying children at risk for later serious antisocial behavior. Prev Sci 2013; 14:423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 16 College Station, TX, StataCorp LLC. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leoutsakos J: Kappa Tree User’s Manual. Available at www.jhsph.edu/prevention/publications/index

- 36.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER, et al. : Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan CK, Soldan A, Pettigrew C, et al. : Depressive symptoms in relation to clinical symptom onset of mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr 2019; 31:561–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Appleby BS, et al. : The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:685–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Xue Q-L, et al. : Depressive symptoms predict incident cognitive impairment in cognitive healthy older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18:204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wise EA, Rosenberg PB, Lyketsos CG, et al. : Time course of neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive diagnosis in National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers volunteers. Alzheimers Dement Amst Neth 2019; 11:333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sunderland T, Linker G, Mirza N, et al. : Decreased β-amyloid1–42 and increased tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer disease. Jama 2003; 289:2094–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alzheimer’s Association: 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc March 2020

- 43.Rahimi J, Kovacs GG: Prevalence of mixed pathologies in the aging brain Alzheimer’s. Res Ther 2014; 6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kørner A, Lauritzen L, Abelskov K, et al. : The Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in dementia. A validity study. Nord J Psychiatry 2006; 60:360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al. : Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 23:271–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lach HW, Chang YP, Edwards D: Can older adults with dementia accurately report depression using brief forms? Reliability and validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Gerontol Nurs 2010; 36:30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris JC: The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Hansson M, Chotai J, Nordstöm A, et al. : Comparison of two self-rating scales to detect depression: HADS and PHQ-9. Br J Gen Pract 2009; 59:e283–e288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]