Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are biomarkers and modifiers of human disease. EVs secreted by insulin-responsive tissues like skeletal muscle (SkM) and white adipose tissue (WAT) contribute to metabolic health and disease but the relative abundance of EVs from these tissues has not been directly examined. Human Protein Atlas data and directly measuring EV secretion in mouse SkM and WAT using an ex vivo tissue explant model confirmed that SkM tissue secretes more EVs than WAT. Differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT were not due to SkM contraction but may be explained by differences in tissue metabolic capacity. We next examined how many EVs secreted from SkM tissue ex vivo and in vivo are myofiber-derived. To do this, a SkM myofiber-specific dual fluorescent reporter mouse was created. Spectral flow cytometry revealed that SkM myofibers are a major source of SkM tissue-derived EVs ex vivo and EV immunocapture indicates that ∼5% of circulating tetraspanin-positive EVs are derived from SkM myofibers in vivo. Our findings demonstrate that 1) SkM secretes more EVs than WAT, 2) many SkM tissue EVs are derived from SkM myofibers, and 3) SkM myofiber-derived EVs reach the circulation in vivo. These findings advance our understanding of EV secretion between metabolically active tissues and provide direct evidence that SkM myofibers secrete EVs that can reach the circulation in vivo.

Keywords: adipose tissue, contraction, extracellular vesicle, myofiber, skeletal muscle

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a broad class of cell-secreted particles found in biofluids throughout the body. Circulating EVs are both biomarkers and contributors to human metabolic disease etiology (1). Skeletal muscle (SkM) and white adipose tissue (WAT) are the two largest organs (by mass) in the body and are central to the etiology of diseases like obesity and Type 2 diabetes. Their mass and disease relevance have led to studies investigating whether their EVs play a causal role in the development of insulin resistance, a component of the metabolic syndrome. High-fat feeding, a common method for causing insulin resistance in rodents and humans, causes an increase in EV secretion from cultured SkM tissue and WAT explants (2, 3). Furthermore, injecting EVs from SkM tissue or WAT explants of diet-induced obese mice into lean recipient mice promote insulin resistance (2, 4). These data suggest that SkM and WAT-derived EVs play a role in metabolic disease etiology. However, the relative contribution of SkM or WAT tissues to circulating EV abundance is not known.

SkM myofibers and adipocytes are nonvascular cells, meaning that there is interstitial space and the vascular endothelium between cells and the circulation. There is very little data demonstrating whether, and to what extent, EVs from nonvascular cells (aside from tumors) are able to reach the circulation. Most of this emerging knowledge comes from transgenic fluorescent reporter mice. For example, the “mT/mG” (referred to as mG/mT mice in the current report) conditional dual fluorescent reporter mouse has been used to demonstrate that bronchoalveolar epithelial cells secrete EVs that can be found in the lung but not serum (5). Studies using WAT transplantation suggest that adipocyte-derived EVs can transport micro RNAs (miRNAs) to distal organs and tissues (6), whereas studies using mice with adipocyte-specific expression of tdTomato suggest that adipocytes are not a major contributor to circulating EVs (3). To our knowledge, there are no published studies demonstrating the existence of SkM myofiber-derived EVs in blood circulation in vivo. Furthermore, the biophysical mechanism whereby EVs secreted from nonvascular cells travel from the local extracellular environment across the vascular endothelium into the blood has yet to be described.

EVs from SkM cells are principally understood based on monocultures of proliferating myocytes and, to a lesser extent, differentiated myotubes (7). Proliferating C2C12 myocytes secrete EVs that improve endothelial function in vitro (8). EV secretion from C2C12 myocytes is increased by the saturated fatty acid palmitate and these palmitate-induced C2C12 myocyte-derived EVs impair insulin signaling in recipient cells (9). Although these studies have improved our understanding of EV biology in SkM cells, proliferating myocytes do not necessarily behave like the terminally differentiated myofibers that dominate SkM tissues. Proliferating myocytes are primarily glycolytic, whereas SkM myofibers in tissues have a metabolic phenotype determined in large part by fiber type (i.e., fast vs. slow twitch). It is therefore unsurprising that EVs from proliferating SkM myocytes have a distinct composition compared with EVs secreted by differentiated SkM myotubes (10). These data demonstrate a putative role for SkM-derived EVs in intercellular and interorgan communication and suggest that oxidative metabolism may be a determinant of EV secretion.

Cell monocultures are a relatively simple system for studying SkM myocyte-derived EVs, but they lack the cellular heterogeneity and extracellular matrix characteristic of tissues. Ex vivo incubation of SkM tissue explants has been shown to be an alternative approach to study EVs (2, 8, 9, 11). This method yields EVs with a comparable size, morphology, and composition to EVs from cultured cells or blood (2). SkM tissue-derived EVs from obese mice increase expression of genes involved in regulating β-cell mass in lean recipient mice (9). SkM tissue-derived EVs from hind limb denervated mice alter adipocyte gene expression in a coculture system (11). In addition to SkM explants, WAT explants have also been studied. EVs consistent with a white adipocyte profile (i.e., adipokines and adipocyte-derived proteins) have been found in human plasma (12). In addition, the WAT explant model has been employed to characterize adipocyte-specific EV-like particles (4). These findings demonstrate the utility of tissue explants to measure EV secretion in specific tissues and to compare EV secretion between tissues.

In this report, we examined curated human protein and gene expression data and performed ex vivo measurements of EV secretion to test the hypothesis that SkM tissue secretes more EVs than WAT per unit of mass. We then generated a SkM myofiber-specific mG/mT mouse to test the hypothesis that SkM myofibers can secrete EVs ex vivo that can reach the circulation in vivo.

METHODS

Secondary Analysis of Data from the Human Protein Atlas

A retrospective analysis of publicly available protein and gene expression data from the Human Protein Atlas v. 19.3 was completed. Comparisons were made using immunohistochemistry (IHC) (skeletal muscle myocytes vs. white adipose tissue adipocytes) and RNA-Seq (skeletal muscle vs. adipose tissues) from the “Normal Tissue Data” and “RNA consensus tissue gene data” files, respectively. Specifically, we compared the 23 genes annotated in the “Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis” gene ontology cellular process (GO:0140112). IHC data are reported by HPA in four ordinal variables that were assigned numbers (Not Detected = 0, Low = 1, Medium = 2, and High Expression = 3). RNA data are reported as normalized expression, aggregating RNA-seq data processed using three different analytical workflows (HPA, GTEx, and FANTOM). All data for all genes are provided in Table 1. Because these data are not reported as replicates, no statistical comparisons were possible. Instead, ordinal IHC data were either greater in SkM, greater in WAT, or comparable. Continuous gene expression data were either greater in SkM or greater in WAT.

Table 1.

SkM is enriched in EV Biogenesis proteins compared with WAT based on IHC and RNA-Seq data from The Human Protein Atlas

| IHC in Cell Types |

RNA-Seq in Tissues |

IHC + RNA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein/Gene | Adipose Tissue Adipocyte | SkM Myocyte | Greater | White Adipose Tissue | SkM Tissue | Greater | |

| Arrdc1 | 0 | 3 | SkM | 8.4 | 9.1 | SkM | Yes |

| Arrdc4 | 1 | 3 | SkM | 9.2 | 10.1 | SkM | Yes |

| Atp13a2 | 0 | 2 | SkM | 9.6 | 7.5 | Adipose | No |

| Cd34 | 0 | 0 | Equal | 61.9 | 39.7 | Adipose | No |

| Chmp2a | 1 | 1 | Equal | 40.7 | 75.7 | SkM | No |

| Cops5 | 3 | 3 | Equal | 20.2 | 64 | SkM | No |

| Hgs | 0 | 2 | SkM | 26.8 | 36.3 | SkM | Yes |

| Myo5b | 0 | 0 | Equal | 2 | 0.6 | Adipose | No |

| Pdcd6ip | 0 | 2 | SkM | 39.1 | 29.5 | Adipose | No |

| Prkn | 0 | 2 | SkM | 6.8 | 41.8 | SkM | Yes |

| Rab7a | 2 | 2 | Equal | 61.5 | 146.3 | SkM | No |

| Rab11a | 0 | 1 | SkM | 43.3 | 27.3 | Adipose | No |

| Rab27a | 0 | 0 | Equal | 11.4 | 5.1 | Adipose | No |

| Sdc1 | 0 | 0 | Equal | 0.8 | 0.5 | Adipose | No |

| Sdc4 | 2 | 2 | Equal | 15.9 | 25.5 | SkM | No |

| Sdcbp | 0 | 0 | Equal | 106.2 | 22.5 | Adipose | No |

| Smpd3 | 0 | 0 | Equal | 3.5 | 1.8 | Adipose | No |

| Snf8 | 0 | 1 | SkM | 22.5 | 40.7 | SkM | Yes |

| Stam | 1 | 0 | Adipose | 13.5 | 26 | SkM | No |

| Steap3 | 2 | 1 | Adipose | 8.1 | 10.9 | SkM | No |

| Tsg101 | 0 | 2 | SkM | 24.7 | 44.5 | SkM | Yes |

| Vps4a | 1 | 1 | Equal | 20.2 | 81.6 | SkM | No |

| Vps4b | 0 | 0 | Equal | 16.8 | 9.9 | Adipose | No |

| SkM | 9 | SkM | 13 | Targets | |||

| Equal | 12 | WAT | 10 | 6 | |||

| WAT | 0 | ||||||

Data obtained from The Human Protein Atlas v. 19.3 (www.humanproteinatlas.org). IHC expression values were obtained from the “normal tissue data” file. Data were converted from text to ranked values (Not Detected = 0, Low = 1, Medium – 2 and High Expression = 3). RNA-Seq data were obtained from the “RNA consensus tissue gene data” file. These data are reported as normalized expression aggregated across three distinct RNA-Seq workflows (HPA, GTEx, and FANTOM). The specific genes analyzed comprise the gene ontology cellular process “EV Biogenesis” (GO:0140112) and include two genes (ARRDC1 and ARRDC4) involved in microvesicle secretion. IHC, immunohistochemistry; SkM, SkM, skeletal muscle; WAT, white adipose tissue.

Mouse Models and Studies

All studies were approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol No.: 18–7858 A). All mice were on the C57BL/6J background and originally purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Wild-type mice were allowed a 2-wk acclimation period before commencing studies. A colony of “mT/mG” (referred to as SkM-mG/mT mice in this report) fluorescent reporter mice was established using [B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J – Stock No.: 007676] mice. These mice express membrane-targeted tandem dimer Tomato (mT) in all cells in the absence of Cre recombinase. In cells expressing Cre recombinase, the mT gene construct is excised so a membrane-targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein (mG) (13) is expressed instead. For our experiments, mice with expression of SkM myofiber-specific expression of mG were desired. This was achieved by crossing mG/mT mice with human skeletal actin (HSA)-Cre79 [B6.Cg-Tg(ACTA1-cre)79Jme/J – Stock No.: 006149] mice and the progeny of those mice (+/− Cre, +/− mG/mT) bred back to homozygous (+/+) mG/mT mice. Tail snip or ear punch DNA was analyzed via PCR to verify the mG/mT and Cre alleles. Male mice with homozygous expression of the “mG/mT” allele were bred to female mice homozygous for the mG/mT allele and heterozygous for HSA-Cre. Progeny were either Cre negative and termed “mT mice” or Cre positive and termed “SkM-mG/mT mice.”

For plasma and tissue collection, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Whole blood was transferred into EDTA-coated tubes and immediately centrifuged at 5,000 g at 4°C for 10 min to remove cells and debris. Plasma was collected by centrifugation at 18,000 g at 4°C for 30 min and stored at −80°C. Vastus medialis and epididymal adipose tissue were subsequently collected and stored in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) until dissection.

The following cohorts of mice were studied in this report:

Cohort 1: Male WT (n = 3, mT (n = 3) and SkM-mG/mT (n = 3) at ∼20 wk of age. Results from these mice are described in Fig. 1, B–E, and Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

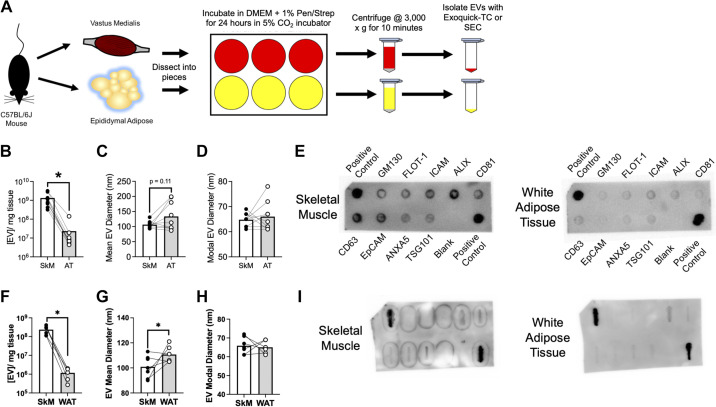

Figure 1.

SkM secretes more EVs than WAT ex vivo. A: assay workflow for measuring ex vivo EV secretion in mouse vastus medialis skeletal muscle (SkM) and epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT). Additional experimental details are provided in the METHODS. B: abundance of Exoquick-TC isolated SkM and WAT particles measured by NTA. n = 3 WT, n = 3 mT, and n = 3 SkM-mG/mT mice were studied; n = 9 total mice. P < 0.05 using paired Student’s t test. C: mean EV diameter from Exoquick-TC isolated particles. D: modal diameter of Exocheck-TC isolated particles. E: representative ExoCheck blot using 25 μg of protein from Exoquick TC-isolated SkM and WAT-derived EVs. F: abundance of SEC-isolated SkM and WAT particles measured by NTA. n = 6 SkM mG/mT mice. P < 0.05 using paired Student’s t test. G: mean diameter of SEC-isolated particles. H: modal diameter of SEC-isolated particles. I: abundance of EV-associated proteins from 25 μg of protein from SEC-isolated SkM and WAT-derived EVs. EVs, extracellular vesicles; mG, membrane targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein; mT, membrane targeted tdTomato; WT, wild type.

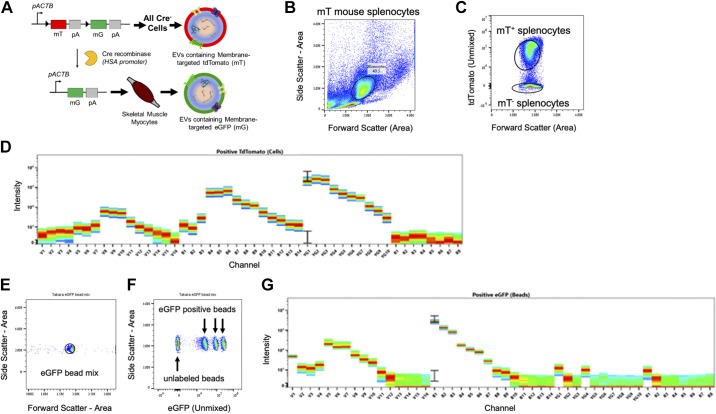

Figure 3.

Spectral unmixing of tdTomato and eGFP fluorophores. A: gene editing approach predicting the secretion of tdTomato or eGFP-expressing EVs. B: monocytes were isolated from mT mice using differential centrifugation and analyzed in a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer. Monocytes were identified using SSC-Area vs. FSC-Area. C: monocyte populations were distinguished by gating on compensated tdTomato. D: fluorescence spectra of tdTomato+ monocytes across 48 detection channels. E: eGFP-labeled beads were identified by plotting SSC-Area vs. FSC-Area. F: eGFP+ and eGFP− beads were distinguished using compensated eGFP. G: fluorescence spectra for eGFP+ beads across 48 detection channels. eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; EVs, extracellular vesicles.

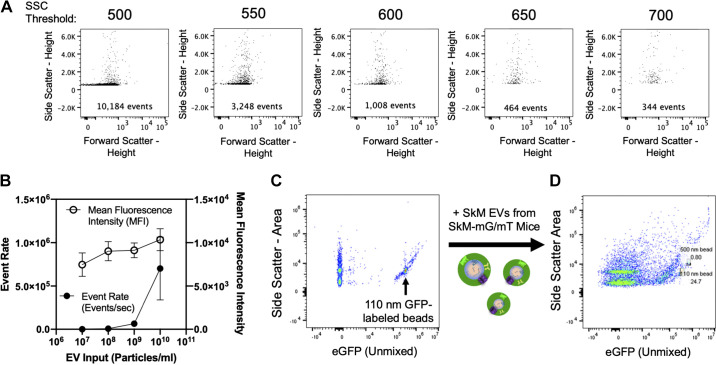

Figure 4.

Detection of EV-sized particles using spectral flow cytometry. A: side scatter threshold stepping using 0.1-μM filtered PBS was performed to minimize instrument noise. Inlaid units are events/s. B: serial dilution of SkM tissue derived EVs from mT mice measuring mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) as a function of event rate (events/min). C: detection of a mixture of Apogee beads containing both unlabeled silica and GFP-labeled polystyrene beads. D: detection of Apogee beads spiked with SkM-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice. EV, extracellular vesicle; GFP, green fluorescent protein; mG, membrane targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein; mT, membrane targeted tdTomato; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; SkM, skeletal muscle.

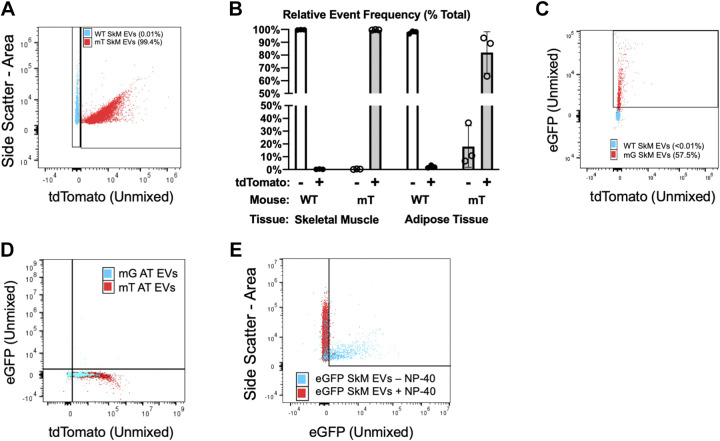

Figure 5.

Detection of endogenously fluorescent EVs using spectral flow cytometry. A: representative plot showing side scatter (y-axis) and tdTomato fluorescence (x-axis) in SkM EVs from WT (blue) and mT (red) mice measured at 108 EVs/mL. B: summary data for tdTomato+ events in EVs from SkM or WAT of WT or mT mice. C: representative plot showing tdTomato (y-axis) and eGFP (x-axis) in SkM EVs from WT (blue) and SkM-mG/mT (red) mice. D: representative plot showing tdTomato (y-axis) and eGFP (x-axis) in AT EVs from mT (blue) and SkM-mG/mT (red) mice showing no detectable presence of mG. E: representative data showing that lysing EVs with 0.5% NP-40 for 30 min at RT (red) cause the disappearance of eGFP (x-axis) in SkM EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice. All data representative of three biological replicates per experiment. eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; EV, extracellular vesicle; mG, membrane targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein; mT, membrane targeted tdTomato; SkM, skeletal muscle; WAT, white adipose tissue; WT, wild type.

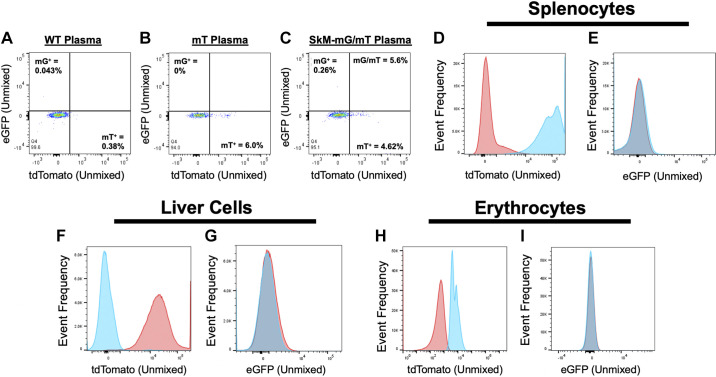

Figure 6.

Evidence for systemic distribution of SkM myofiber-specific EVs in vivo using spectral flow cytometry. Plasma EVs from WT (A), mT (B), and SkM-mG/mT (C) mice were isolated using Exoquick-TC and analyzed at 1 × 1011 using spectral flow cytometry. Data are representative of EVs isolated with ExoQuick-TC (shown), ExoQuick Plasma or size exclusion chromatography (SEC). D: frequency histogram of tdTomato from splenocytes isolated from WT mice (red) or SkM-mG/mT mice (blue). E: frequency histogram of eGFP from splenocytes isolated from WT (red) or SkM-mG/mT mice (blue). F: frequency histogram of tdTomato in liver cells isolated from WT (blue) or SkM-mG/mT mice (red). G: frequency histogram of eGFP in liver cells isolated from WT (blue) or SkM-mG/mT mice (red). H: frequency histogram of tdTomato in erythrocytes isolated from WT (red) or SkM-mG/mT mice (blue). I: frequency histogram of eGFP in erythrocytes isolated from WT (blue) or SkM-mG/mT mice (red). eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; EV, extracellular vesicle; mG, membrane targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein; mT, membrane targeted tdTomato; SkM, skeletal muscle; WT, wild type.

Cohort 2: Male WT mice (n = 6) at ∼18 wk of age. Results from these mice are described in Fig. 2, A–C.

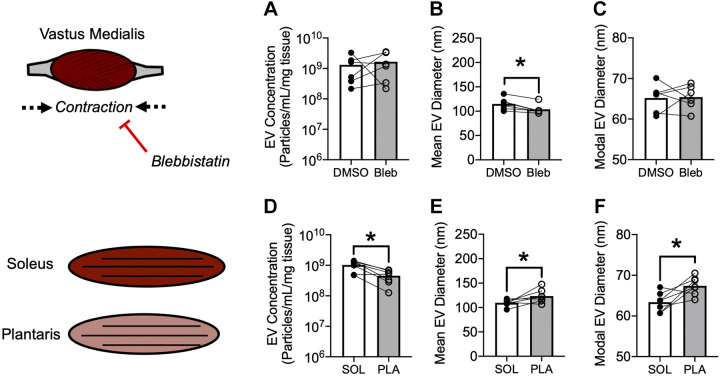

Figure 2.

Ex vivo EV secretion is determined by metabolic capacity but not spontaneous contraction. A–C: comparison of EVs secreted by vastus medialis skeletal muscle of male WT mice in the absence or presence of 10 μM blebbistatin or DMSO vehicle for 24 h. (A) Mass-adjusted EV secretion. B: mean EV diameter. C: modal EV diameter. n = 6 mice. *P < 0.01 using paired Student’s t test. D–F: comparison of EVs secreted by oxidative (soleus) or glycolytic (plantaris) skeletal muscle from female mT mice. D: mass-adjusted EV secretion. E: mean EV diameter. F: modal EV diameter. n = 7 mice. *P < 0.01 using paired Student’s t test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EV, extracellular vesicle; mT, membrane targeted tdTomato; WT, wild type.

Cohort 3: Female mT mice (n = 6) at ∼18 wk of age. Results from these mice are described in Fig. 2, D–F.

Cohort 4: Male SkM-mG/mT mice (n = 8) at 21 wk of age. Results from these mice are shown in Fig. 1, F–I, and Fig. 7.

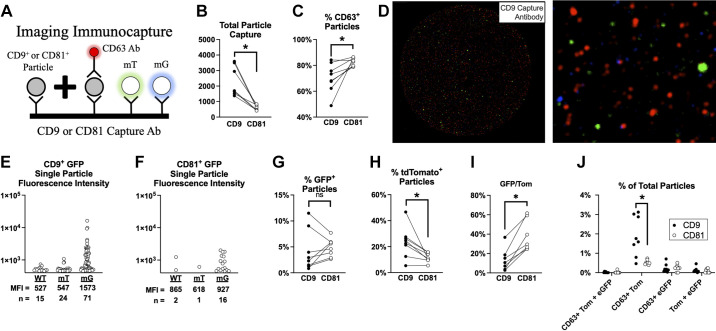

Figure 7.

SkM myofibers secrete EVs that can reach the circulation in mice. A: illustration of immunocapture and fluorescence imaging of plasma EVs. B: total capture of CD9+ or CD81+ plasma EVs. C: percent (%) of CD9+ (closed circles) or CD81+ particles (open circles) that coexpress CD63. D: representative image of CD9 immunocapture experiment using plasma from a SkM-mG/mT mice. Single particle eGFP fluorescence in plasma of a wild-type (WT), mT, and mG mouse with CD9 (E) or CD81 (F) capture. G: percentage of particles that coexpress CD9/CD81 and eGFP. H: percentage of particles that coexpress CD9/CD81 and tdTomato (Tom). I: fraction of fluorescent particles that express eGFP relative to Tom. J: percentage of particles that coexpress CD9/CD81 and at least two fluorescent markers (eGFP, Tom, or CD63). N = 8 SkM-mG/mT mice were studied. P < 0.05 using paired Student’s two-way t test. eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; EV, extracellular vesicle; mG, membrane targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein; mT, membrane-targeted tdTomato; SkM, skeletal muscle.

Cohort 5: Male WT mice (n = 12) between 8 and 12 wk of age. Methods and results from these mice are shown in Supplemental Materials (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17198510.v1).

Ex Vivo EV Secretion Assay

This method was adapted from Aswad et al. (2) with our specific approach illustrated in Fig. 1. Vastus medialis SkM and epididymal WAT were dissected into ∼5 mg pieces in ice-cold PBS. Approximately 50 mg of SkM tissue was placed in each well. Because of low EV yield from WAT, ∼250 mg of WAT was used in each well. Tissue was cultured in poly-l-lysine-coated six-well plates (Corning Inc.) containing 2 mL of serum-free DMEM (Sigma D1145: 4.5 g/L d-Glucose and sodium bicarbonate, without l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, or phenol red) and was supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cultured tissue was incubated for 24 h in a 95% O2-5% CO2-supplemented incubator at 37°C. SkM and WAT tissues were collected from each well, weighed, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C. EV-rich conditioned media was collected via centrifugation at 3,000 g for 15 min, to clear cells and debris, and stored at −80°C until EV isolation.

Because of the smaller masses of soleus and plantaris compared with vastus, 12-wells plates with 0.75 mL of media per well were used to study these tissues. In all other respects, tissues were handled exactly the same as aforementioned.

Inhibition of Spontaneous SkM Contraction

To examine the role of spontaneous SkM contraction using the myosin ATPase inhibitor blebbistatin, 12-well plates with 0.75 mL of media were used. Then, 10 µM blebbistatin or vehicle (DMSO) was added to each well to inhibit spontaneous SkM contraction as we have previously demonstrated (14). Tissues and media were subsequently handled in an identical fashion to the procedure aforementioned.

EV Isolation

From mice in Cohort 1, EVs were isolated using Exoquick-TC according to the manufacturer’s instructions, or size exclusion chromatography (SEC) as previously described (15). To isolate EVs from conditioned media with Exoquick, we combined media with Exoquick-TC at a 5:1 ratio (i.e., 500 µL of media and 100 µL of Exoquick-TC) and incubated for 12 h at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 1,500 g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant discarded, and EVs were resuspended in 100 µL of 0.1 µM filtered PBS. From mice in cohort 2, EVs were isolated from conditioned media via SEC using Captocore 700 (1.5 mL conditioned media diluted to 5 mL in 0.1 µM filtered PBS and passed over 1 mL of Captocore 700) and processed as previously described (15). Isolated EVs were stored at −20°C for subsequent analyses.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was performed on a three laser ViewSizer 3000 (Horiba Instruments). Then 0.1 µM filtered H2O was used as diluent and all EV concentrations were subtracted from a diluent file created specifically for samples run and analyzed that day. Focus was optimized for each individual sample immediately before recording. The following recording settings were used: Frame Rate = 30 fps, Exposure = 15 ms, Gain = 30 dB, Stir time between videos = 5 s, Wait time between videos = 3 s, Blue Laser Power = 210 mW, Green Laser Power = 12 mW, Red Laser Power = 8 mW, Frames per video = 300, Videos Recorded = 25, Temperature = 22°C. Videos were processed using ViewSizer software using the following settings as recommended by the manufacturer: Detection Threshold Type = Manual, Detection Threshold = 0.8, AutoThreshold = Disabled, Feature Radius = 40 pixels, Drift Correction = 0%. To avoid over or underestimation of particle concentration or size, samples were diluted in the same 0.1 µM filtered H2O as used to generate the diluent file to reach 120–150 tracks per frame as recommended by the manufacturer. EV concentration obtained from NTA was adjusted for dilution factor and then normalized to tissue mass. Therefore, EV concentration is reported as particles/mL/mg tissue.

Protein Quantification

Protein from isolated EVs was analyzed using a micro BCA assay (Bio-Rad) in polystyrene 96-well plates according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices Inc.) or Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 562 nm absorbance.

Exocheck Antibody Array

The Exocheck Antibody Array (Systems Biosciences) was used to determine the presence of EV-associated proteins (CD63, CD81, ALIX, FLOT1, ICAM1, EpCam, ANXA5, and TSG101) and cellular contamination (GM130) in EVs isolated from conditioned media with Exoquick-TC or SEC. Due to low protein yield from WAT-derived EVs, 25 µg of protein measured using a micro BCA assay was used for both SkM and WAT-derived EVs. To image blots, the PVDF membranes were incubated for 2 min in SuperSignal West Pico Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) ECL reagent then imaged on a FluorChem E imager (Bio-Techne). Note that Exocheck blots on Exoquick-TC isolated EVs were generated from tissues (SkM and WAT) of one mouse, whereas a different mouse was used for Exocheck blots from SkM and wAT EVs isolated with SEC. Also note the different blot design (circles vs. lines, different blot dimensions) from the two sets of Exocheck blots.

Flow Cytometry

Flow experiments were performed using a four laser (405, 488, 562, and 640 nm excitation) Aurora spectral flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences) in the Colorado State University Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting facility. EV detection and optimization were conducted in accordance with MISEV and MIFlowCyt guidelines (16, 17). Before each analysis, the cytometer was warmed up by running 0.2 µM filtered water for 45 min. Quality control was performed using SpectroFlo Cytometer QC Beads (Cytek Biosciences, bead lot 2002) to normalize sensor gain as recommended by the manufacturer. In addition, a clean flow cell procedure was conducted before sample analysis to minimize EV carryover. The flow cell was confirmed to be clean based on a low event rate (< 25–30 events/s) while running 0.1 µM filtered PBS. Side scatter was measured using the 405 nm violet laser for improved detection of small EVs (18) and a side scatter threshold of 700 was applied unless otherwise noted. Finally, samples were run at a low flow rate (∼15 µL/min), to minimize swarming and improve signal:noise. Additional optimization and validation experiments are described in RESULTS. Data were collected in SpectroFlo and .fcs files were exported and further analyzed using FlowJo Version 10.6. To confirm that EV-associated fluorescence was from lipid vesicles, we compared isolated EVs analyzed as aforementioned before and after detergent lysis via 0.1% NP-40 for 30 min at room temperature.

Isolation of Mouse Splenocytes and Liver Cells

Splenocytes were isolated and purified as described on the R&D systems website (https://www.rndsystems.com/resources/protocols/leukocyte-preparation-protocol). Liver cells were isolated in an identical fashion but excluding the erythrocyte lysis step. Splenocytes and liver cells were resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry.

Isolation of Mouse Erythrocytes

Mouse erythrocytes were isolated and resuspended as previously described (19). Whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture in heparinized tubes, centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed three times in “cell wash buffer” at 37°C (pH = 7.4) containing (in mM): 4.7 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 140.5 NaCl, 21.0 Tris-base, 5.5 glucose, and 0.5% BSA. Erythrocytes were resuspended in bicarbonate-based buffer containing (in mM): 4.7 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 140.5 NaCl, 11.1 D-glucose, 23.8 NaHCO3, and 0.5% BSA for flow cytometry.

EV Immunocapture Imaging

To measure single particle fluorescence of mG and mT in plasma, we used the Exoview R-200 instrument platform. Platelet-free plasma was diluted 1:2 in Incubation Solution (a proprietary formulation without Tween-20) and 50 µL of the sample was incubated for 16 h at RT on ExoView Mouse Tetraspanin chips (EV-TETRA M, NanoView Biosciences). The chips contained spots printed with anti-mouse CD9 (clone MZ3) or anti-mouse CD81 (clone EAT2) for EV population characterization, or hamster IgG or rat IgG antibodies used as a control for nonspecific binding of EVs. Chips were washed according to the EV_TETRA_V0 protocol on the NanoView Chip Washer 100 (NanoView Biosciences). Samples were stained with anti-mouse CD63-CF647 (clone NVG2), and left unstained in the green and blue detection channels for detection of endogenous mTomato (green) and GFP (blue) in the captured EV populations. After the washing protocol chips were imaged using the ExoView R200 scanner with ExoView Scanner 3.0 acquisition software. Data were analyzed using the ExoView Analyzer 3.0 software program. For a preliminary set of samples (Fig. 7, C and D), the detection thresholds for GFP were set to (400 au), mTomato/set to (280 au), and CD63 set to (300 au) and detection range for Interference Microscopy set to 50–200 nm. A subsequent analysis of cohort 4 (n = 8 SkM-mG/mT mice) was analyzed using an increased GFP threshold set to 500 au to further reduce detection of autofluorescence. The signal level recorded on the isotype control spot was used to set the detection and the settings were the same for all experiments except for the adjustment of GFP threshold noted above.

Mean fluorescence intensity of mG in individual CD9+ or CD81+ particles was assessed using the “ParticleCounts” output from the ExoView Analyzer software. Abundance of each EV population captured (CD9 vs. CD81) was determined using interference microscopy measurements obtained from the “ColocalizationAnalysis” output. Individual CD9+ or CD81+ particles were then further examined for the coexpression of mG, mT, and/or CD63. Because we detected more CD9+ particles than CD81+ particles, all subsequently analyses are presented as relative values. Data are shown as dots for individual mice.

Data Analysis

For all experiments, EV abundance and size are shown as dots for each individual mouse studied. Statistical comparisons were performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad). Comparisons of EV abundance and diameter between tissues or in response to blebbistatin were made using paired Student’s t test. Statistical comparisons were not possible for Human Protein Atlas data since replicate values are not provided.

RESULTS

SkM is Enriched in Proteins Involved in EV Biogenesis Compared with WAT in Humans

We first tested the hypothesis that SkM has a greater capacity for EV secretion than WAT by performing a retrospective analysis of publicly available protein and gene expression data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) v. 19.3. IHC and RNA-Seq data for the 23 genes from the “Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis” gene ontology cellular process (GO:0140112) are provided in Table 1. Comparing IHC of SkM myofibers to WAT adipocytes revealed nine distinct proteins with greater relative expression in SkM myofibers. The remaining 12 proteins were comparable in expression; no proteins were greater in WAT adipocytes than SkM myofibers. RNA-Seq data revealed a total of 13 genes more abundantly expressed in SkM, with the remaining 10 genes expressed to a greater extent in WAT than SkM. Combining results together revealed six EV biogenesis genes (Arrdc1, Arrdc4, Hgs, Parkin, Snf8, and TSG101) with greater protein and transcript in SkM compared with WAT. Overall, this secondary analysis of public data support the hypothesis that EV secretion is greater in SkM compared with WAT.

SkM Tissue Secretes Exponentially More EVs than WAT per Unit of Mass Ex Vivo

With evidence that SkM is enriched in EV biogenesis proteins relative to WAT, we directly compared EV secretion from SkM (vastus medialis) and WAT (epididymal visceral fat) of C57BL/6J mice using the ex vivo approach outlined in Fig. 1A.

First, we compared EV abundance in the conditioned media from SkM tissue and WAT after isolation with Exoquick-TC. EV abundance in conditioned media was ∼100-fold greater in SkM compared with WAT after normalizing for tissue mass (Fig. 1B). There was no difference in mean (Fig. 1C) or modal EV diameter (Fig. 1D) between SkM and WAT-derived EVs. Dot blots of EVs isolated from SkM and WAT conditioned media (Fig. 1E) show the presence of EV-associated proteins, but also the intracellular Golgi protein GM130. To verify our observation that SkM tissue secretes more EVs than WAT, we studied additional SkM and WAT samples from a separate cohort of mice where EVs were isolated via SEC. Consistent with our first cohort, we observed greater EV abundance in SkM versus WAT (Fig. 1F). In this cohort, we also observed a significantly greater mean EV diameter (Fig. 1G) but no difference in modal diameter (Fig. 1H). Dot blots confirm the presence of EV-associated proteins but GM130 was not detectable in these samples (Fig. 1I).

Contraction Does Not Increase EV Secretion from SkM Tissue Ex Vivo

SkM is unique from most other tissues, including WAT, in its ability to contract. SkM contraction is thought to explain, at least in part, the increased abundance of circulating EVs observed during exercise (20, 21). SkM explants contract ex vivo but this can be prevented by the addition of 10 µM blebbistatin (14), a myosin ATPase inhibitor. We hypothesized that spontaneous contraction could explain the differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT measured ex vivo. To test this hypothesis, we compared EV secretion from SkM explants in the presence of blebbistatin (10 µM) or an equal volume of DMSO vehicle. Contrary to our hypothesis, blebbistatin did not decrease SkM EV secretion (Fig. 2A). However, blebbistatin did cause a decrease in mean (Fig. 2B), but not modal (Fig. 2C) EV diameter. These data indicate that greater EV secretion from SkM compared with WAT is not explained by artifactual spontaneous contraction of SkM.

To further address this question, we measured the abundance of EVs from conditioned media following electrical stimulation of extensor digitorum longus muscle. The methods and results for this experiment are provided in Supplemental Materials. Under these exercise-mimicking conditions, EV abundance was not increased by contraction. These findings further support our conclusion above that SkM contraction does not explain differences in EV abundance between SkM and WAT.

Metabolic Activity is Related to SkM EV Secretion Ex Vivo

Since differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT were not explained by contraction, we hypothesized that the intrinsic metabolic activity of tissues might determine EV secretion. To test this hypothesis, we compared soleus, a highly oxidative muscle, to plantaris, a more glycolytic muscle. Consistent with our hypothesis, soleus secreted more EVs than plantaris per unit of mass (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, soleus secreted EVs that were smaller both in mean (Fig. 2E) and modal (Fig. 2F) diameter compared with plantaris. These data suggest that metabolic activity might explain differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT, but additional experiments are needed to define the specific mechanism(s) involved.

Spectral Unmixing of Enhanced GFP and Tandem Dimer Tomato

SkM tissue is a robust source of EVs, but it is not known to what extent specific cell types within SkM tissue secrete EVs. We developed a cell-specific dual fluorescent reporter mouse to determine the contribution of SkM myofibers to SkM tissue-derived EV secretion. In Fig. 3A, we illustrate the genetic construct used to generate mice with ubiquitous expression of membrane-targeted tdTomato (Ex 554 nm/Em 581 nm) termed, “mT.” We then bred that line with mice expressing HSA-Cre, which have Cre recombinase expression specifically in SkM myofibers. The resulting mice have SkM myofiber-specific expression of membrane-targeted enhanced GFP (Ex 488 nm/Em 507 nm) termed, “mG” and mT expression in all other cells. To detect mG and mT in individual particles, we used the spectral unmixing algorithm supplied in the SpectroFlo software to unmix eGFP, tdTomato, and autofluorescence. Within this analysis, 48 detection channels collect data simultaneously and generate a spectral signature for each unique fluorophore. Spectral unmixing applies a modified least squares algorithm to not only extract autofluorescence, but also distinguish between fluorophores with and without overlapping spectra. Conventionally, stained and unstained-control cells are the required input to accomplish spectral unmixing. To unmix the spectra of tdTomato, splenocytes isolated from mT mice were used as the stained (fluorophore positive) population, and splenocytes from a WT mouse were used as an unstained-control (fluorophore negative) population. Splenocytes were gated first on forward scatter (FSC)-Area versus side scatter (SSC)-Area (Fig. 3B) then on the presence of tdTomato (Fig. 3C). The fluorescent spectral signature used for unmixing for tdTomato is shown in Fig. 3D. To unmix eGFP, commercially available eGFP-labeled flow cytometer calibration beads (Takara Biosciences) and unstained beads (Thermo Fisher) were used. Beads were first gated based on FSC-Area versus SSC-Area (Fig. 3E) then on the presence of eGFP (Fig. 3F). The spectral signature for eGFP is shown in Fig. 3G. All subsequent fluorescence data report tdTomato and eGFP (unmixed) signals.

Detecting EV-Sized Particles Using Spectral Flow Cytometry

With the ability to discriminate between mT (tdTomato) and mG (eGFP) positive populations, the cellular origin of EVs derived from SkM tissue was determined. An optimized flow cytometry-based approach to detect EV populations based on side scatter using the 405-nm laser of a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer was established. First, a side scatter threshold stepping analysis was performed using 0.1 µM filtered PBS (Fig. 4A). This analysis was performed to identify a threshold that eliminates the majority of instrument noise, thereby increasing the likelihood that detected events are biological particles like EVs.

Next, coincident detection (aka swarming) of particles was addressed. To increase the likelihood that mT+ or mG+ events represented single particles, serial dilutions of EVs were analyzed based on EV concentrations determined by NTA. Experiments began with 1010 EVs/mL. EVs were diluted an order of magnitude at each step. Swarming was considered minimal when the event rate decreased as a function of dilution, whereas mean fluorescent intensity remained stable. Figure 4B summarizes a set of serial dilution experiments (n = 3 mice) performed with SkM-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice. Based on these results, it was determined that an EV concentration of 1×109/mL or less was sufficient to minimize swarming. This concentration is consistent with previous flow studies using different flow cytometric instruments and particle compositions (22, 23).

Next, we tested whether SkM-derived EVs from our fluorescent reporter mice could be detected using these established settings. To do this, we first confirmed the ability to detect a heterogenous mixture of small (110 nm diameter; indicated with arrow) GFP-labeled polystyrene beads (refractive index = 1.59) and similarly sized unlabeled silica beads (refractive index = 1.43) (Fig. 4C). SkM-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice were then added to the bead mixture and reanalyzed with the same settings. Shown in Fig. 4D, SkM-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice had similar side scatter properties to small GFP-labeled and unlabeled beads. In addition, eGFP was detected across a range of side scatter intensities, suggesting the presence of fluorescently labeled EVs. Fluorescent EVs are further explored in Figs. 5 and 6. These data demonstrate that both unlabeled and fluorescent EVs can be detected using spectral flow cytometry.

Endogenous Fluorescent Proteins Are Incorporated into SkM Tissue-Derived EVs Secreted Ex Vivo

Equipped with the ability to detect EV-sized particles and independently resolve eGFP and tdTomato, we next measured the abundance of fluorescently labeled EVs secreted by SkM at 109 particles/mL. For these experiments, we used WT C57BL/6J mice (no fluorescence), mT mice (ubiquitous mT expression), or SkM-mG/mT mice (mG in SkM myocytes/myofibers, mT in all other cells). We first compared SkM EVs between WT and mT mice. As predicted, EVs isolated from WT SkM tissue lacked mT, whereas nearly all EVs from mT mice (>98%) were mT+. An overlay of representative data from each genotype is provided in Fig. 5A. Similar distributions were found in WAT analyzed at 107 particles/mL due to the lower yield noted in Fig. 1G. Summary data for these experiments are provided in Fig. 5B. These results suggest that mT is incorporated into tissue-derived EVs secreted ex vivo.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that mG is incorporated into EVs in a SkM myofiber-specific fashion. On average, less than 0.1% of SkM tissue-derived EVs from either WT or mT mice were mG positive. By contrast, SkM tissue-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice consistently displayed eGFP expression (30.54 ± 18.4% of events). An overlay of representative experiments from WT and SkM-mG/mT mice is shown in Fig. 5C. In addition to single positive mG events, SkM tissue-derived EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice also had on average 14.28 ± 6.2% dual positive (mG and mT) events but only 1.38 ± 0.4% single positive (mT only) events. To confirm that mG-containing EVs are specifically secreted by SkM myofibers, we also measured tdTomato and eGFP in WAT-derived EVs. mG was not detected in EVs secreted by WAT of SkM-mG/mT mice (Fig. 5D). Finally, detergent lysis of EVs from SkM-mG/mT mice with 0.1% NP-40 eliminated fluorescence thus confirming the presence of endogenous fluorescent proteins in EVs secreted ex vivo (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these data suggest that SkM myofibers account for a significant proportion of SkM tissue-derived EVs secreted ex vivo.

Evidence for SkM-Derived EVs in Plasma and non-SkM Cells In Vivo

With evidence that mT and SkM myofiber-derived mG can be incorporated into EVs secreted ex vivo, we next wanted to examine to what extent SkM myofiber-derived EVs reach blood plasma in vivo. To address this question, we isolated EVs from plasma of WT, mT, or SkM-mG/mT mice using SEC, Exoquick plasma kit, or Exoquick-TC (to match our ex vivo isolation conditions) and performed spectral flow cytometry. Similar results were obtained using all three methods; the results shown here are representative experiments from plasma EVs isolated using SEC or Exoquick-TC. In WT plasma (Fig. 6A), less than 0.5% of events were positive for mT or mG. In mT plasma (Fig. 6B), 6.0% of events were mT positive but no mG positive events were detected. Finally, events from SEC-isolated plasma EVs of SkM-mG/mT mice contained 4.6% mT positive events and 0.26% mG positive events (Fig. 6C).

Since the abundance of mG+ EVs was quite low in plasma, we isolated splenocytes, whole liver cells, and erythrocytes to determine the extent to which SkM myofiber-derived mG might incorporate into distant tissues. As shown in Fig. 6D, splenocytes robustly express mT as expected. Furthermore, mG does appear to be present, albeit at very low levels in splenocytes (Fig. 6E). We confirmed the same robust presence of mT (Fig. 6F) but modest presence of mG (Fig. 6G) in whole liver cell preparations. Finally, erythrocytes also expressed mT (Fig. 6H) but not mG (Fig. 6I). These data suggest that SkM myofiber-derived mG may reach the plasma and distal tissues like the spleen and liver but are not taken up by circulating erythrocytes. Collectively, these data provide little evidence to demonstrate that SkM myofiber-derived EVs are abundant in circulation.

EVs like exosomes are known to express tetraspanins like CD9, CD63, and CD81, so we examined whether individual tetraspanin-expressing particles from SkM-mG/mT mouse plasma coexpress mG and mT. This analysis was performed on a cohort (n = 8 mice) of male 21-wk-old SkM-mG/mT mice. Figure 7A illustrates the markers and corresponding colors detected. Overall, CD9+ EVs were more abundant than CD81+ EVs in plasma of SkM-mG/mT mice (Fig. 7B). We found that CD63 was coexpressed more often on CD81 EVs relative to CD9 EVs (Fig. 7C). A representative image of CD9 captured plasma EVs from a SkM-mG/mT mouse is provided in Fig. 7D. In the magnified image, distinct mT (green) and mG (blue)-expressing EVs can be observed. Single particle fluorescence intensity measurements confirm an abundance of eGFP+ particles coexpressing CD9+ (Fig. 7E) and CD81+ (Fig. 7F) in SkM-mG/mT mice compared with mT and WT mice.

Next, we measured the abundance of mG-expressing CD9+ and CD81+ EVs in plasma. Both CD9 and CD81 EVs contain mG (Fig. 7G), with 4.2 ± 3.9% of CD9 EVs and 4.9 ± 1.7% of CD81 EVs coexpressing mG, respectively. We found that tdTomato was more frequently expressed in CD9 EVs than CD81 EVs (Fig. 7H), with 23.3 ± 12.1% of CD9 and 11.5 ± 3.5% of CD81 EVs coexpressing mT, respectively. Comparing mG and mT expression revealed that CD81 EVs have greater relative enrichment of mG compared with CD9+ EVs (Fig. 7I). Examining EVs with multiple markers, we found that CD63 was coexpressed with mT more often than mG regardless of CD9 or CD81 expression (Fig. 7J). Furthermore, mT and CD63 are coexpressed to a greater extent in CD9 EVs relative to CD81 EVs. These data clearly demonstrate the existence of SkM myofiber EVs in circulation and estimate that they account for 4%–5% of circulating tetraspanin-expressing EVs in mice under free living conditions.

The mechanism responsible for trafficking EVs from nonvascular cells into the blood is not known. We hypothesized that if SkM myofiber EVs are trafficked through the endothelial cell via active transport by clathrin or caveolin-mediated pathways, then mG and mT might be coexpressed in the same EV. We found that fewer than 1% of CD9 or CD81 EVs coexpress both mG and mT in the same EV (Fig. 7I). This finding suggests that SkM myofiber EVs may reach the circulation without physically interacting with the endothelial cell membrane, but it is not yet known how this might occur. Public link of data supplements: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17198510.v1.

DISCUSSION

Defining the origin, abundance, and function of EVs from specific cells and tissues is vital for using EVs as biomarkers and engineered therapies. There are a number of factors that dictate how much a given cell type will contribute to circulating EV abundance, including tissue mass, tissue EV secretion capacity, EV access to circulation and EV clearance. None of these factors have been well defined, emphasizing the need for targeted approaches and novel methodologies. SkM and WAT are, by mass, two of the largest tissues in the body and would therefore be predicted to be major contributors to circulating EV abundance. Using both curated human data and an ex vivo tissue culture assay, we demonstrate that, on a per mass basis, SkM tissue secretes more EVs than WAT. We show that tissue metabolic activity is related to SkM EV secretion capacity and may explain differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT. Using spectral flow cytometry, we demonstrate that SkM tissue-derived EVs secreted ex vivo originate, at least in part, from SkM myofibers. Despite the robust ability of SkM myofibers to secrete EVs ex vivo, we detected very few SkM myofiber-derived EVs in blood plasma or distal organs using spectral flow cytometry. However, using targeted immunocapture of tetraspanin-expressing particles, we estimate that fluorescently labeled SkM myofiber EVs account for 4%–5% of circulating EVs under free living conditions. Our findings provide compelling evidence that SkM myofiber EVs secreted in vivo reach the circulation and could, therefore, contribute to systemic physiological functions in distant cells and tissues.

Some of the data described in this report was obtained with an ex vivo EV secretion assay using mouse tissue explants. There is precedent for the use of similar approaches in both SkM (2, 8) and WAT (24). For the studies described here, there were multiple advantages to using this ex vivo approach. First, this method allowed us to directly compare EV secretion between tissues of individual mice. The within-subject design used here eliminated the contribution of variance between animals and permitted the use of pair-wise statistical comparisons. Second, the quality of the data presented here was strengthened by normalizing EV secretion to tissue mass, which allowed us to directly compare EV secretion capacity while eliminating the variance associated with differences in tissue input. Third, this method allowed for the study of EV secretion from cells existing in their native extracellular environment. This is important because EVs are known to respond to and interact with the extracellular matrix (25), which serves not only as a scaffold but also a communication interface that is inextricably linked to cell signaling and metabolism (26). Finally, by studying SkM tissue instead of cell monocultures, the contribution of SkM myofibers to EV secretion relative to other tissue resident cells could be assessed. This is important since resident SkM progenitor cells and fibroblasts are also known to secrete EVs (27, 28). Although we contend that our tissue-based approach was the best available model for the questions addressed here, the limitations should also be noted. For example, dissection of SkM tissue damages myofibers and increases the risk of cellular contamination. Indeed, we did detect GM130, a Golgi-associated protein, in both SkM and WAT-derived EVs (Fig. 1E) in our Exoquick-TC isolated EVs. However, subsequent SEC isolation eliminated GM130 without changing the relative abundance of SkM and WAT EVs (Fig. 1I). It is unclear to what extent cellular contamination may affect our results, but mean (Fig. 1H and Fig. 2, B and E) and modal (Fig. 1I and Fig. 2, C and F) EV diameters determined with NTA in four different datasets demonstrate that the vast majority of particles in our samples are “small” EVs (< 200 nm diameter) as defined by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) (16). Although it is apparent that tissue explant-derived EVs present challenges with regard to EV purity, the methods described here represent an important advance in this underdeveloped area of research.

We found using publicly available human tissue and cell data that human SkM and myofibers contain more of the molecular machinery needed to synthesize EVs than WAT and white adipocytes (Table 1). Consistent with this observation, we found that EV secretion capacity is greater in the mixed vastus medialis SkM compared with epididymal WAT ex vivo (Fig. 1G). There are a few distinguishing features between SkM and WAT that could explain the greater rate of EV secretion in SkM compared with WAT. We examined two of these possibilities in this report. First, we demonstrated that spontaneous SkM contraction, which we inhibited with blebbistatin, did not explain greater EV secretion in SkM compared with WAT (Fig. 2A). The blebbistatin concentration used in this study (10 µM) was chosen because we have shown it to be sufficient to prevent contraction in mouse and human SkM explants in previous studies (14). The lack of a decrease in EV abundance is intriguing in part because, at higher concentrations, blebbistatin has been shown to inhibit EV secretion from tumor cells (at 50 µM) (29) and inhibit the release of small (∼30 nm) cholesterol-rich particles from macrophages (at 30 µM) (30). These previous studies suggest that blebbistatin might decrease SkM EV secretion at higher doses, but since this was observed in noncontracting cells, the effect would likely be independent of SkM contraction. Another possibility to explain these tissue-specific differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT is metabolic activity. SkM is a far more metabolically active tissue compared with WAT so we hypothesized that tissues with greater metabolic activity have a greater capacity for EV secretion. Previous work indicated that oxidative SkM secretes more EV protein than glycolytic SkM (8); however, this study determined EV quantity based on acetylcholinesterase which may not be a suitable index of EV abundance (31). Here, we confirmed this hypothesis (and those previous findings) using NTA to directly compare EV secretion between soleus, a highly oxidative muscle, and plantaris, which is more glycolytic (Fig. 2D). It is worth noting that human SkM tissue contains ∼50 times more protein than WAT per unit of mass (32), further suggesting that the metabolic activity of the tissue may determine EV secretion rates. Our data collectively demonstrate that SkM has a higher capacity to secrete EVs than WAT, metabolic activity predicts SkM EV secretion capacity ex vivo and this may explain differences in EV secretion between SkM and WAT.

Using spectral flow cytometry, we observed an abundance of fluorescently labeled EVs (mT and/or mG) in SkM and WAT ex vivo (Fig. 5) but very few in blood plasma of the same mice (Fig. 6). However, using targeted immunocapture of tetraspanin-expressing EVs, we provide evidence that SkM myofiber EVs are present in circulation (Fig. 7). To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative detection of SkM myofiber-derived EVs in circulation. There are at least two previous reports that used fluorescent reporter mice to examine the abundance of other nonvascular cell-derived EVs in circulation. Pua et al. (5) generated mG/mT mice where eGFP was expressed specifically in pulmonary epithelial cells. Using differential ultracentrifugation, the authors detected an abundance of mT and mG-labeled EVs in brochoalveolar lavage fluid but fluorescent EVs were absent in serum. Flaherty et al. used an adipocyte-specific mT mouse to detect adipose-derived EVs using Western blotting, but did not attempt to quantify the relative abundance of adipocyte EVs in circulation. The findings described here (plasma EVs isolated using precipitation or SEC), by Pua et al. (serum EVs isolated using differential ultracentrifugation) (5) and Flaherty et al. (ultrafiltration and size exclusion chromatography) (3) support two complementary and emerging paradigms. First, the results of these studies are consistent with previous work showing that EVs represent only a small fraction of EV-sized particles found in plasma (33, 34). Immunocapture of tetraspanin-expressing EVs improved our ability to detect SkM myofiber EVs in plasma (Fig. 7) compared with spectral flow (Fig. 6). Since cell-specific fluorescent EVs can be detected in abundance ex vivo, our results suggest that EVs secreted by nonvascular cells like SkM myofibers represent a minority of circulating EVs. The recent discovery and characterization of matrix-bound nanovesicles in pig urinary bladder and dermis (35, 36) suggest that other tissues (i.e., SkM and WAT) may also have EVs embedded in the extracellular matrix. Future studies might use the SkM-mG/mT mouse or other endogenous fluorescent reporter mouse models to determine the extent to which SkM myofiber-derived EVs secreted in vivo exist in distinct extracellular compartments.

We found little evidence for SkM myofiber EVs in plasma using spectral flow cytometry (Fig. 6). However, targeted immunocapture of tetraspanin-expressing particles confirmed that SkM myofiber EVs reach the circulation in mice (Fig. 7). We suspect that coisolation of lipoproteins and/or protein aggregates in common EV isolation procedures (33, 34) resulted in poor detection using spectral flow cytometry. Future studies using this mouse model would benefit from the use of targeted immunocapture to enrich for EVs and then subsequently detect endogenous fluorescent proteins.

Our finding that SkM myofiber EVs reach the circulation is intriguing in part because there is no established biophysical mechanism to explain their movement across the endothelium. Although there are reports of EVs being taken up by endothelial cells (37), to our knowledge, there are no reports of basal-to-apical flux of EVs through endothelial cells or the gap junctions that perforate the endothelium. Small EVs like exosomes (50–200 nm diameter) are much larger than gap junctions (2–3 nm diameter), suggesting that their transport is more likely to occur through endothelial cells rather than via gap junctions. We hypothesized that if SkM myofiber EVs traveled through the endothelial cells that they might express both mG from SkM and mT from other cells due to mixing of the endothelial plasma membrane with the EV membrane. However, we found that fewer than 1% of circulating tetraspanin-expressing EVs express both mG and mT, instead suggesting that SkM myofiber EVs may reach the circulation independent of transendothelial trafficking. Future studies should explore the mechanism(s) responsible for SkM EV flux from tissues to the circulation.

Monocytes like macrophages may selectively extract and/or modify EVs in the circulation. There is some evidence for monocytic handling of EVs in blood (38) that is consistent with their role in detoxification. Monocytes also exist in most other tissue compartments (including SkM and WAT) but do not appear to preclude the detection of fluorescent EVs in our ex vivo experiments or those by Flaherty et al. (3). To what extent EVs may be modified traveling through the endothelium or following uptake by monocytes is unknown but could be addressed in future studies. The continued development and application of fluorescent reporter mice like the mG/mT mouse and others [i.e., conditional CD63-GFP mouse (39)] will further elucidate the distribution of cell-specific EVs in vivo.

An improved understanding of EV secretion by different tissues and their biodistribution in vivo is needed to realize the full potential of EVs as biomarkers and therapeutics. Here, we demonstrate that SkM tissue secretes more than WAT per unit of mass. Future studies could examine whether this relationship is true within tissues (i.e., white vs. brown adipose) and across skeletal muscle fiber types. Finally, for the first time, we were able to detect and quantify the abundance of SkM myofiber EVs in circulation using the dual fluorescent mG/mT mouse, laying the foundation for future studies to establish whether, and to what extent, SkM myofibers secrete EVs in response to stressors like exercise and how those EVs impact organ systems.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental figures: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17198510.v1.

GRANTS

American Heart Association provided extramural support through an Innovative Project Award (IPA1834110052 to D.S.L.). This study was also supported by National Insititutes of Health Grant R01AR066660 (to E.E.S.).

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Clayton Deighan is employed by Nanoview Biosciences who markets the Exoview R-200, which was used to generate data in this paper. Dr. Deighan performed these experiments as a contract service for the corresponding author and Nanoview did not provide any funding or have any influence on the experiments performed, data reported or the conclusions drawn in this paper. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L.E., E.E.S., and D.S.L. conceived and designed research; A.L.E., Z.J.V., G.H., A.J.A., N.S.W., N.P.B., C.D., E.E.S., and D.S.L. performed experiments; A.L.E., Z.J.V., G.H., A.J.A., N.S.W., N.P.B., C.D., C.P.A., and D.S.L. analyzed data; A.L.E., Z.J.V., C.P.A., E.E.S., N.A.K.-G., and D.S.L. interpreted results of experiments; A.L.E. and D.S.L. prepared figures; A.L.E. and D.S.L. drafted manuscript; A.L.E., Z.J.V., G.H., C.P.A., N.A.K.-G., and D.S.L. edited and revised manuscript; A.L.E., Z.J.V., G.H., A.J.A., N.S.W., N.P.B., C.D., C.P.A., E.E.S., N.A.K.-G., and D.S.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following sources: Colorado State University Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility for their help in method development, optimization, and sample analysis, and American Heart Association for extramural support through an Innovative Project Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noren Hooten N, Evans MK. Extracellular vesicles as signaling mediators in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318: C1189–C1199, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00536.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aswad H, Forterre A, Wiklander OP, Vial G, Danty-Berger E, Jalabert A, Lamazière A, Meugnier E, Pesenti S, Ott C, Chikh K, El-Andaloussi S, Vidal H, Lefai E, Rieusset J, Rome S. Exosomes participate in the alteration of muscle homeostasis during lipid-induced insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia 57: 2155–2164, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3337-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flaherty SE 3rd, Grijalva A, Xu X, Ables E, Nomani A, Ferrante AW Jr.. A lipase-independent pathway of lipid release and immune modulation by adipocytes. Science 363: 989–993, 2019. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng ZB, Poliakov A, Hardy RW, Clements R, Liu C, Liu Y, Wang J, Xiang X, Zhang S, Zhuang X, Shah SV, Sun D, Michalek S, Grizzle WE, Garvey T, Mobley J, Zhang HG. Adipose tissue exosome-like vesicles mediate activation of macrophage-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 58: 2498–2505, 2009. doi: 10.2337/db09-0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pua HH, Happ HC, Gray CJ, Mar DJ, Chiou NT, Hesse LE, Ansel KM. Increased hematopoietic extracellular RNAs and vesicles in the lung during allergic airway responses. Cell Rep 26: 933–944.e4, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, Gorden P, Kahn CR. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature 542: 450–455, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rome S, Forterre A, Mizgier ML, Bouzakri K. Skeletal muscle-released extracellular vesicles: state of the art. Front Physiol 10: 929, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie Y, Sato Y, Garner RT, Kargl C, Wang C, Kuang S, Gilpin CJ, Gavin TP. Skeletal muscle-derived exosomes regulate endothelial cell functions via reactive oxygen species-activated nuclear factor-κB signalling. Exp Physiol 104: 1262–1273, 2019. doi: 10.1113/EP087396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalabert A, Vial G, Guay C, Wiklander OP, Nordin JZ, Aswad H, Forterre A, Meugnier E, Pesenti S, Regazzi R, Danty-Berger E, Ducreux S, Vidal H, El-Andaloussi S, Rieusset J, Rome S. Exosome-like vesicles released from lipid-induced insulin-resistant muscles modulate gene expression and proliferation of beta recipient cells in mice. Diabetologia 59: 1049–1058, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forterre A, Jalabert A, Berger E, Baudet M, Chikh K, Errazuriz E, De Larichaudy J, Chanon S, Weiss-Gayet M, Hesse AM, Record M, Geloen A, Lefai E, Vidal H, Couté Y, Rome S. Proteomic analysis of C2C12 myoblast and myotube exosome-like vesicles: a new paradigm for myoblast-myotube cross talk? PLoS One 9: e84153, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Gasperi R, Hamidi S, Harlow LM, Ksiezak-Reding H, Bauman WA, Cardozo CP. Denervation-related alterations and biological activity of miRNAs contained in exosomes released by skeletal muscle fibers. Sci Rep 7: 12888, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13105-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly KD, Wadey RM, Mathew D, Johnson E, Rees DA, James PE. Evidence for adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles in the human circulation. Endocrinology 159: 3259–3267, 2018. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45: 593–605, 2007. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry CG, Kane DA, Lin CT, Kozy R, Cathey BL, Lark DS, Kane CL, Brophy PM, Gavin TP, Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Inhibiting myosin-ATPase reveals a dynamic range of mitochondrial respiratory control in skeletal muscle. Biochem J 437: 215–222, 2011. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz G, Bridges C, Lucas M, Cheng Y, Schorey JS, Dobos KM, Kruh-Garcia NA. Protein digestion, ultrafiltration, and size exclusion chromatography to optimize the isolation of exosomes from human blood plasma and serum. J Vis Exp 134: 57467, 2018. doi: 10.3791/57467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 7: 1535750, 2018. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh JA, Van Der Pol E, Arkesteijn GJA, Bremer M, Brisson A, Coumans F, Dignat-George F, Duggan E, Ghiran I, Giebel B, Görgens A, Hendrix A, Lacroix R, Lannigan J, Libregts SFWM, Lozano-Andrés E, Morales-Kastresana A, Robert S, De Rond L, Tertel T, Tigges J, De Wever O, Yan X, Nieuwland R, Wauben MHM, Nolan JP, Jones JC. MIFlowCyt-EV: a framework for standardized reporting of extracellular vesicle flow cytometry experiments. J Extracell Vesicles 9: 1713526, 2020. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1713526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McVey MJ, Spring CM, Kuebler WM. Improved resolution in extracellular vesicle populations using 405 instead of 488 nm side scatter. J Extracell Vesicles 7: 1454776, 2018. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1454776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Racine ML, Dinenno FA. Reduced deformability contributes to impaired deoxygenation-induced ATP release from red blood cells of older adult humans. J Physiol 597: 4503–4519, 2019. doi: 10.1113/JP278338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frühbeis C, Helmig S, Tug S, Simon P, Krämer-Albers E-M. Physical exercise induces rapid release of small extracellular vesicles into the circulation. J Extracell Vesicles 4: 28239, 2015. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.28239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitham M, Parker BL, Friedrichsen M, Hingst JR, Hjorth M, Hughes WE, Egan CL, Cron L, Watt KI, Kuchel RP, Jayasooriah N, Estevez E, Petzold T, Suter CM, Gregorevic P, Kiens B, Richter EA, James DE, Wojtaszewski JFP, Febbraio MA. Extracellular vesicles provide a means for tissue crosstalk during exercise. Cell Metab 27: 237–251.e4, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groot Kormelink T, Arkesteijn GJ, Nauwelaers FA, van den Engh G, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Wauben MH. Prerequisites for the analysis and sorting of extracellular vesicle subpopulations by high-resolution flow cytometry. Cytometry A 89: 135–147, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Pol E, van Gemert MJ, Sturk A, Nieuwland R, van Leeuwen TG. Single vs. swarm detection of microparticles and exosomes by flow cytometry. J Thromb Haemost 10: 919–930, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Z, Wang X, Liu X, Du H, Sun C, Shao X, Tian J, Gu X, Wang H, Tian J, Yu B. Adipose-derived exosomes exert proatherogenic effects by regulating macrophage foam cell formation and polarization. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e007442, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 527: 329–335, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lark DS, Wasserman DH. Meta-fibrosis links positive energy balance and mitochondrial metabolism to insulin resistance. F1000Res 6: 1758, 2017. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11653.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fry CS, Kirby TJ, Kosmac K, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Myogenic progenitor cells control extracellular matrix production by fibroblasts during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Stem Cell 20: 56–69, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murach KA, Vechetti IJ Jr, Van Pelt DW, Crow SE, Dungan CM, Figueiredo VC, Kosmac K, Fu X, Richards CI, Fry CS, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Fusion-independent satellite cell communication to muscle fibers during load-induced hypertrophy. Function (Oxf) 1: zqaa009, 2020. doi: 10.1093/function/zqaa009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brassart B, Da Silva J, Donet M, Seurat E, Hague F, Terryn C, Velard F, Michel J, Ouadid-Ahidouch H, Monboisse JC, Hinek A, Maquart FX, Ramont L, Brassart-Pasco S. Tumour cell blebbing and extracellular vesicle shedding: key role of matrikines and ribosomal protein SA. Br J Cancer 120: 453–465, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X, Weston TA, He C, Jung RS, Heizer PJ, Young BD, Tu Y, Tontonoz P, Wohlschlegel JA, Jiang H, Young SG, Fong LG. Release of cholesterol-rich particles from the macrophage plasma membrane during movement of filopodia and lamellipodia. eLife 8: e50321, 2019. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao Z, Jaular LM, Soueidi E, Jouve M, Muth DC, Schøyen TH, Seale T, Haughey NJ, Ostrowski M, Théry C, Witwer KW. Acetylcholinesterase is not a generic marker of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 8: 1628592, 2019. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1628592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroh AM, Lynch CE, Lester BE, Minchev K, Chambers TL, Montenegro CF, Chavez C, Fountain WA, Trappe TA, Trappe SW. Human adipose and skeletal muscle tissue DNA, RNA, and protein content. J Appl Physiol (1985) 131: 1370–1379, 2021. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00343.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.György B, Módos K, Pállinger E, Pálóczi K, Pásztói M, Misják P, Deli MA, Sipos A, Szalai A, Voszka I, Polgár A, Tóth K, Csete M, Nagy G, Gay S, Falus A, Kittel A, Buzás EI. Detection and isolation of cell-derived microparticles are compromised by protein complexes resulting from shared biophysical parameters. Blood 117: e39–e48, 2011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Borg EGF, Liaci AM, Vos HR, Stoorvogel W. A novel three step protocol to isolate extracellular vesicles from plasma or cell culture medium with both high yield and purity. J Extracell Vesicles 9: 1791450, 2020. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1791450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huleihel L, Hussey GS, Naranjo JD, Zhang L, Dziki JL, Turner NJ, Stolz DB, Badylak SF. Matrix-bound nanovesicles within ECM bioscaffolds. Sci Adv 2: e1600502, 2016. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hussey GS, Pineda Molina C, Cramer MC, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Lee YC, El-Mossier SO, Murdock MH, Timashev PS, Kagan VE, Badylak SF. Lipidomics and RNA sequencing reveal a novel subpopulation of nanovesicle within extracellular matrix biomaterials. Sci Adv 6: eaay4361, 2020. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu SF, Noren Hooten N, Freeman DW, Mode NA, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Extracellular vesicles in diabetes mellitus induce alterations in endothelial cell morphology and migration. J Transl Med 18: 230, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02398-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imai T, Takahashi Y, Nishikawa M, Kato K, Morishita M, Yamashita T, Matsumoto A, Charoenviriyakul C, Takakura Y. Macrophage-dependent clearance of systemically administered B16BL6-derived exosomes from the blood circulation in mice. J Extracell Vesicles 4: 26238, 2015. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Men Y, Yelick J, Jin S, Tian Y, Chiang MSR, Higashimori H, Brown E, Jarvis R, Yang Y. Exosome reporter mice reveal the involvement of exosomes in mediating neuron to astroglia communication in the CNS. Nat Commun 10: 4136, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11534-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figures: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17198510.v1.