Abstract

Significance.

Moderate to high uncorrected hyperopia in preschool children is associated with amblyopia, strabismus, reduced visual function, and reduced literacy. Detecting significant hyperopia during screening is important to allow children to be followed for development of amblyopia or strabismus and implementation of any needed ophthalmic or educational interventions.

Purpose.

To compare the sensitivity and specificity of two automated screening devices to identify preschool children with moderate to high hyperopia.

Methods.

Children in the Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) Study were screened with the Retinomax Autorefractor and Plusoptix Power Refractor II and examined by masked eyecare professionals to detect the targeted conditions of amblyopia, strabismus, or significant refractive error, and reduced visual acuity. Significant hyperopia (AAPOS definition of hyperopia as an amblyopia risk factor), based on cycloplegic retinoscopy, was >4.00 D for age 36 to 48 months and >3.50 D for age >48 months. Referral criteria from VIP for each device and from a distributor (PediaVision) for the Power Refractor II were applied to screening results.

Results.

Among 1,430 children, 132 children had significant hyperopia in ≥1 eye. Using VIP referral criteria, sensitivity for significant hyperopia was 80.3% for the Retinomax and 69.7% for the Power Refractor II (difference 10.6%, 95% CI (7.0%—20.5%); P=.04); specificity relative to any targeted condition was 89.9% and 89.1%, respectively. Using PediaVision referral criteria for the Power Refractor, sensitivity for significant hyperopia was 84.9%; however, specificity relative to any targeted condition was 78.3%, 11.6% lower than the specificity for the Retinomax. Analyses using the VIP definition of significant hyperopia yielded results similar to when the AAPOS definition was used.

Discussion.

When implementing vision screening programs for preschool children, the potential for automated devices that employ eccentric photorefraction to either miss detecting significant hyperopia or increase false positive referrals must be taken into consideration.

Screening of preschool children for hyperopia traditionally has been motivated by the fact that children with moderate to high hyperopia have an elevated risk of amblyopia and strabismus.1–4 However, recent studies of preschool children have also demonstrated that children with moderate uncorrected hyperopia are more likely to have lower preschool literacy, reduced near visual acuity, worse stereopsis, and less accurate accommodation than otherwise similar emmetropic children, even in the absence of strabismus, amblyopia, significant anisometropia or astigmatism.5–9 These risks increase with the magnitude of hyperopia. Early identification of children with moderate to high hyperopia is important so that children can be followed for development of amblyopia or strabismus and any needed ophthalmic or educational interventions can be implemented.

Over the past two decades, the use of automated devices for preschool vision screening has increased.10 Compared to traditional visual acuity screening methods based on the identification of optotypes, automated devices require less effort from the child and are faster. Similar to screening tests based on optotype identification, testing with automated devices can be administered by both eyecare professionals and lay people. The performance of automated devices, including autorefractors and photorefractors, has been examined by many different investigators.11–13 However, most of these investigations have involved only a low number of children with hyperopia, reported sensitivity for a combination of some or all of the targeted ocular disorders without reporting sensitivity for hyperopia alone, involved only children seen in pediatric eyecare practices, and/or evaluated the precision of the devices compared to cycloplegic refraction rather than their accuracy (e.g., sensitivity and specificity) in referral of preschoolers for further evaluation.11–13

The Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) Study was conducted to evaluate 11 preschool vision screening tests administered by licensed eyecare providers experienced in working with children. Previous publications from the VIP Study Group have assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the tests for a set of four targeted conditions (amblyopia, strabismus, significant refractive error, and reduced visual acuity) and have assessed other characteristics of the screening tests involving refraction such as whether use of eyecare professionals or lay people as screeners affects performance of the tests or whether reducing testing distance from 10 feet to 5 feet improves testing.14–17 The sensitivity of the Power Refractor II (Plusoptix, Nuremberg, Germany) for detecting hyperopia (i.e., yielding a referral when a certain level of hyperopia is present) was not evaluated directly in these VIP publications. The Power Refractor II employs eccentric photorefraction and has a stated measurement range of −7.00D to +5.00D. The Retinomax is an autorefractor (stated measurement range −18D to +23D) that has been shown previously to have high sensitivity (approximately 80% or more) for significant hyperopia with high specificity (approximately 80% or more).14–17,19,20 18 In this report using data from the VIP Study, we evaluated the sensitivity and specificity, particularly sensitivity for significant hyperopia, of the Power Refractor II in comparison to the Retinomax (Nikon, Inc., Melville, NY). Although the Power Refractor II has been replaced by later models (https://plusoptix.com/products), the analyses here were undertaken to understand how screening devices that employ the eccentric photorefraction approach impact the results of screening for significant hyperopic refractive errors.21–23

METHODS

The VIP Study was a multicenter, cross-sectional study. Data for this report were collected during two consecutive academic years (October 2001 to June 2003). Institutional Review Boards associated with each study site approved the protocol. This research was reviewed by independent ethical review boards associated with each center and conformed with the principles and applicable guidelines for the protection of human subjects in biomedical research. Parents or legal guardians of participating children provided written informed consent. The design and methods have been published previously; only the details relevant to the results presented below are included here.14

Participant Selection for the VIP Study

All VIP participants were enrolled in Head Start programs near the 5 VIP clinical centers (Berkeley, California; Boston, Massachusetts; Columbus, Ohio; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Tahlequah, Oklahoma). Children who were 36 to 59 months of age on September 1st of the academic year in which they were tested were eligible for study participation. All children who failed and a random sample (approximately 20%) of those who did not fail their local Head Start vision screening were invited for participation. The procedures used for the local Head Start screenings were chosen by the local Head Start program. The procedures varied among centers and included monocular visual acuity, cover test at distance and near, stereopsis and non-cycloplegic retinoscopy. This approach provided a study population that was enriched with children having ocular disorders.

Procedures for Administering VIP Screening Tests and Eye Examinations

Screening tests and a standardized comprehensive eye examination (completed at least one day after the screening; median 3 days, interquartile range (2,6)) were administered by optometrists and pediatric ophthalmologists who were experienced in the care of young children and who had completed a certification program in VIP study standardized procedures. The order of testing with the Retinomax and Power Refractor II was randomized. Those who performed eye examinations were masked to the results of the screening tests.

The Retinomax is a handheld autorefractor that measures refractive error monocularly along two meridians. For each eye, the screener placed the instrument’s headrest on the child’s forehead, encouraged the child to fixate the internal target, and focused the mire in the center of the pupil while ≥8 readings were taken automatically. The device displayed a reliability reading for each group of readings; if it was <8, the measurement was repeated up to two more times. When a reliable reading could not be obtained for each eye, the result was classified as “Unable” to perform the test.

The Power Refractor II (version 3.11.01.24.00) is a tabletop photorefractor that binocularly measures refractive error in eight meridians together with eye alignment. It uses an eccentric near-infrared light source and the eccentric photorefraction principle,18,19 with Purkinje image tracking for measuring eye alignment. The principle of eccentric photorefraction is based on an analysis of light that has entered the eye and then been reflected from the retina. A camera focused on the eye’s entrance pupil captures the reflected light to determine the spatial gradient of luminance in the pupil image. The slope of this light intensity profile across the pupil is converted to an estimate of the refractive state. When a child fixated on the red and green lights on the camera, the screener began the measurement and continued until a refractive error reading for each eye and an alignment measurement (“gaze deviation”) appeared in green on the display or until the instrument timed out. If the refractive error displayed for either eye was red, the measurement of the highlighted eye(s) was repeated once. When a green reading could not be obtained for each eye, the result was classified as “Unable” to perform the test.

The eye examination was conducted to establish the diagnoses of the four targeted conditions: amblyopia, strabismus, significant refractive error, and reduced visual acuity. Distance visual acuity was assessed with single crowded HOTV optotypes using an electronic visual acuity testing system administered according to the Amblyopia Treatment Study protocol.24–26 Children were retested on the same day after cycloplegic retinoscopy with their full cycloplegic refractive correction if their initial visual acuity scores placed them in a category other than normal (see “Ocular Conditions Targeted For Detection” below) and they had a refractive error in either eye of ≥0.50 diopters (D) of myopia, ≥2.00 D of hyperopia, or ≥1.00 D of astigmatism. Both a cover–uncover test and an alternating cover test were performed at distance (3 m) and near (40 cm). Cycloplegic retinoscopy was performed 30 to 40 minutes after instillation of one drop each of 1% cyclopentolate and 0.5% tropicamide.

Ocular Conditions Targeted for Detection by Screening

We used definitions from the VIP Study for the targeted conditions of amblyopia, strabismus, significant refractive error (including significant hyperopia), and reduced visual acuity. In addition, we used the AAPOS guidelines for significant hyperopia as a risk factor for amblyopia as an alternate definition for significant hyperopia. All definitions were based on the results of the comprehensive eye examination.

VIP Study Definitions of Ocular Conditions

Detailed definitions for the amblyopia, strabismus, significant refractive error, and reduced visual acuity used in the VIP Study have been published previously.14 In general terms, amblyopia was defined as unilateral (≥2-line interocular difference) or bilateral (one eye worse than 20/50, contralateral eye worse than 20/40 for age 3 years; one eye worse than 20/40, contralateral eye worse than 20/30 for age 4 or 5 years) and each required the presence of an amblyogenic factor. When visual acuity met these criteria but no amblyogenic factor was present, the child was classified as having reduced visual acuity. Strabismus was defined as any heterotropia in primary gaze at distance or near. The definitions of significant refractive errors, based on cycloplegic retinoscopy, were >2.00 D in any meridian for myopia, >1.50 D between principal meridians for astigmatism, >1.00 D interocular difference for anisometropia, and >3.25 D in any meridian for hyperopia. A child was considered as having significant myopia or significant hyperopia if either eye met the definition. Children without any of the targeted conditions were considered as normal.

AAPOS Definition of Significant Hyperopia as an Amblyopia Risk Factor

We also considered the sensitivity and specificity of the screening devices for detection of the degree of hyperopia by cycloplegic retinoscopy considered as an amblyopia risk factor by the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS). Their specification is >4.00 D in any meridian for children 48 months and younger and >3.50D in any meridian for children 49 months and older.2 A child was considered as having significant hyperopia if either eye met the definition.

Referral Criteria for Screening Tests

Children were classified as failing the screening test and needing referral for a comprehensive eye examination when one or both eyes met the referral criteria or when they were unable to perform the screening test (Table 1). The original VIP referral criteria for each screening test were developed by first setting the specificity for detecting one or more of the VIP targeted conditions (amblyopia, strabismus, significant refractive error, or reduced visual acuity) at 90% to limit over-referrals (false positives) to 10%.14 Referral criteria were selected to maximize the sensitivity for detecting any targeted condition (referred to as the overall sensitivity). In addition, the referral criteria recommended by PediaVision, a distributor of Plusoptix screening devices, were applied for the Power Refractor II (see Table 1). Singman et al reported that the PediaVision criteria were one of the 2 sets of criteria found to be best at maximizing sensitivity and specificity for all targeted conditions specified in the 2013 AAPOS guidelines for automated preschool vision screening.2,27

Table 1.

VIP and PediaVision referral criteria for each screening device and each type of significant refractive error.

| Device | Hyperopia* | Myopia* | Astigmatism | Anisometropia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinomax | ≥1.50 D | ≥2.75 D | ≥1.50 D | ≥1.75 D |

| VIP criteria | ||||

| Power Refractor II | ||||

| VIP criteria† | ≥3.50 D | ≥3.00 D | ≥2.00 D | ≥1.50 D |

| PediaVision criteria | ≥2.50 D | ≥1.50 D | ≥1.50 D | ≥1.00 D |

In any meridian in either eye

Includes inter-eye gaze difference of ≥9.50 PD

Data Analysis

The Power Refractor II was used only in the 2002 to 2003 academic year and only data from that year for both devices are included in the analyses for this report. Results from both screening devices also needed to be available in order for the child to be included in the analyses. Using both the AAPOS and VIP definitions of significant hyperopia, children were classified as having significant hyperopia when they had significant hyperopia in one or both eyes. Children who were unable to perform a screening test were considered as failing the screening test. Sensitivity for significant hyperopia was estimated as the percentage of children who failed the screening test among children diagnosed with significant hyperopia based on the subsequent eye examination. Overall specificity was estimated as the percentage of children who passed the screening test among children without any targeted condition. Because children who had failed the Head Start preschool vision screening were over-represented in the VIP Study population, a weighted estimate of specificity was used based on the proportion of children failing (1/6) or not failing (5/6) the Head Start screening.14

Tests of differences in sensitivity between the two screening devices and their 95% confidence intervals (CI’s) were based on logistic regression models using the generalized estimating equations approach to accommodate the correlation in results for children undergoing both screening methods. Locally-weighted smoothed (LOWESS) curves were superimposed on scatterplots of the power of the most hyperopic meridian from the device versus from cycloplegic retinoscopy.

RESULTS

Study Participants

During the 2002–2003 academic year, 1446 children were screened and received a standardized comprehensive eye examination. After excluding children missing results from the Retinomax only (N=5), the Power Refractor II only (N=8), or both (N=3), data from 1430 children were available for analysis. Demographic and clinical characteristics of these children are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children.

| Characteristics | All children (N=1430) |

|---|---|

| Age (months) | |

| 39–48 | 329 (23.0%) |

| 49–60 | 775 (54.2%) |

| 61–69 | 326 (22.8%) |

| Mean (SD) | 54.5 (6.8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 725 (50.7%) |

| Female | 705 (49.3%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 673 (47.1%) |

| White | 276 (19.3%) |

| Hispanic | 223 (15.6%) |

| American Indian | 148 (10.4%) |

| Asian | 41 (2.9%) |

| Other/unknown | 69 (4.8%) |

| Amblyopia | 88 (6.2%) |

| Strabismus | 62 (4.3%) |

| Myopia | 25 (1.8%) |

| Astigmatism | 154 (10.8%) |

| Anisometropia | 94 (6.6%) |

| Significant hyperopia – AAPOS definition† | |

| >4.00 D for 48 months and younger, | 132 (9.2%) |

| >3.50 D for 49 months and older | |

| Significant hyperopia – VIP definition† | |

| Hyperopia >3.25 D | 166 (11.6%) |

| Unable on Retinomax | 2 (0.1%) |

| With significant hyperopia, among unable | |

| By AAPOS definition | 1 (50.0%) |

| By VIP definition | 1 (50.0%) |

| Unable on Power Refractor II | 55 (3.8%) |

| With significant hyperopia, among unable | |

| By AAPOS definition | 18 (32.7%) |

| By VIP definition | 18 (32.7%) |

Based on the most positive meridian from cycloplegic retinoscopy in the more hyperopic eye.

AAPOS is American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus

Results of Application of Referral Criteria

The results from application of the referral criteria for each device (Table 1) to the screening results of 1430 children are displayed in Table 3. Sensitivity for detection of significant hyperopia based on the AAPOS and VIP definitions of significant hyperopia and overall specificity are shown.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity for each screening device among children based on AAPOS and VIP definitions of significant hyperopia (N=1430).

| AAPOS significant hyperopia definition# | VIP significant hyperopia definition## | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperopia present (n=132) |

Hyperopia absent (n=1298) |

Hyperopia present (n=166) |

Hyperopia absent (n=1264) |

Overall specificity† (n=1024) |

|

| Fail (%) | Pass (%) | Fail (%) | Pass (%) | ||

| VIP referral criteria | Sensitivity | Specificity** | Sensitivity | Specificity** | |

| Retinomax | 106 (80.3%) |

1017 (78.4%) |

129 (77.7%) |

1006 (79.6%) |

89.9% |

| Power Refractor II | 92 (69.7%) |

1046 (80.6%) |

109 (65.7%) |

1029 (81.4%) |

89.1% |

| P-value* | .04 | .07 | .009 | .15 | |

| PediaVision referral criteria | |||||

| Power Refractor II | 112 (84.9%) |

885 (68.2%) |

136 (81.9%) |

875 (69.2%) |

78.3% |

| P-value* | .32 | <.001 | 0.30 | <.001 | |

AAPOS definition of significant hyperopia: >+4.00 D in any meridian for children 48 months and younger and >+3.50D in any meridian for children 49 months and older

VIP definition of significant hyperopia: >+3.25 D in any meridian

P-value* comparing Retinomax to Power Refractor II

Based on children without hyperopia who were classified as Pass

Based on children without any VIP targeted condition who were classified as Pass

Detection of Significant Hyperopia - AAPOS Definition of Significant Hyperopia (>4.00 D for ≤ 48 Months and >3.50D for ≥49 Months Based on Cycloplegic Retinoscopy)

There were 132 children with significant hyperopia according to the AAPOS definition of significant hyperopia. When VIP screening referral criteria were applied for the Retinomax and Power Refractor II, the percentage failing the screening among children with significant hyperopia (i.e., sensitivity for significant hyperopia) was 80.3% for the Retinomax and 69.7% for the Power Refractor II (difference 10.6%, 95% CI (7.0%—20.5%); P=.04). Among the 132 children with significant hyperopia, there were 18 children who failed the screening with the Power Refractor II because of an Unable result, composing 19.6% of the 92 children failing according to VIP referral criteria. These 18 children with significant hyperopia having an Unable result comprised 32.7% of the total 55 children who were classified as unable. Two (0.1%) of the 1430 children were classified as unable with the Retinomax. The specificity relative to all VIP targeted conditions was close to 90% for both the Retinomax and Power Refractor II when VIP referral criteria were applied.

When the PediaVision referral criteria were applied for the Power Refractor II, the sensitivity for significant hyperopia (84.9%) was not significantly different from the sensitivity of the Retinomax (80.3%) (difference 4.5%; 95% CI (−4.3% to +13.4%); P=.32). The specificity for the Power Refractor II was 78.3%, or 11.6% lower than for the Retinomax (89.9%). Among the 132 children with significant hyperopia, the 18 children with an Unable result on the Power Refractor II composed 16.1% of the 112 children failing according to PediaVision referral criteria.

Detection of Significant Hyperopia – VIP Definition of Significant Hyperopia (>3.25 D Based on Cycloplegic Retinoscopy)

There were 166 children with significant hyperopia according to the VIP definition of significant hyperopia. The sensitivity for significant hyperopia was 77.7% for the Retinomax and 65.7% for the Power Refractor II when VIP referral criteria were used (difference 12.0%, 95% CI (3.2%—20.9%); P=.009). The 18 children who had an Unable result with the Power Refractor II composed 16.5% of the 109 children failing according to VIP referral criteria (see Table 2).

When the PediaVision referral criteria for the Power Refractor II were applied, the sensitivity of the Power Refractor II for detecting hyperopia (81.9%) was not significantly different from the sensitivity of the Retinomax (77.7%) (difference 4.2%; 95% CI (−3.7% to +12.1%); P=.30). The specificity of the Power Refractor II was 78.3%, which was 11.6% lower than for the Retinomax. The 18 children who had an Unable result with the Power Refractor II composed 13.2% of the 136 children failing according to PediaVision referral criteria (see Table 2).

Refractive Error from Screening Devices and Cycloplegic Refraction

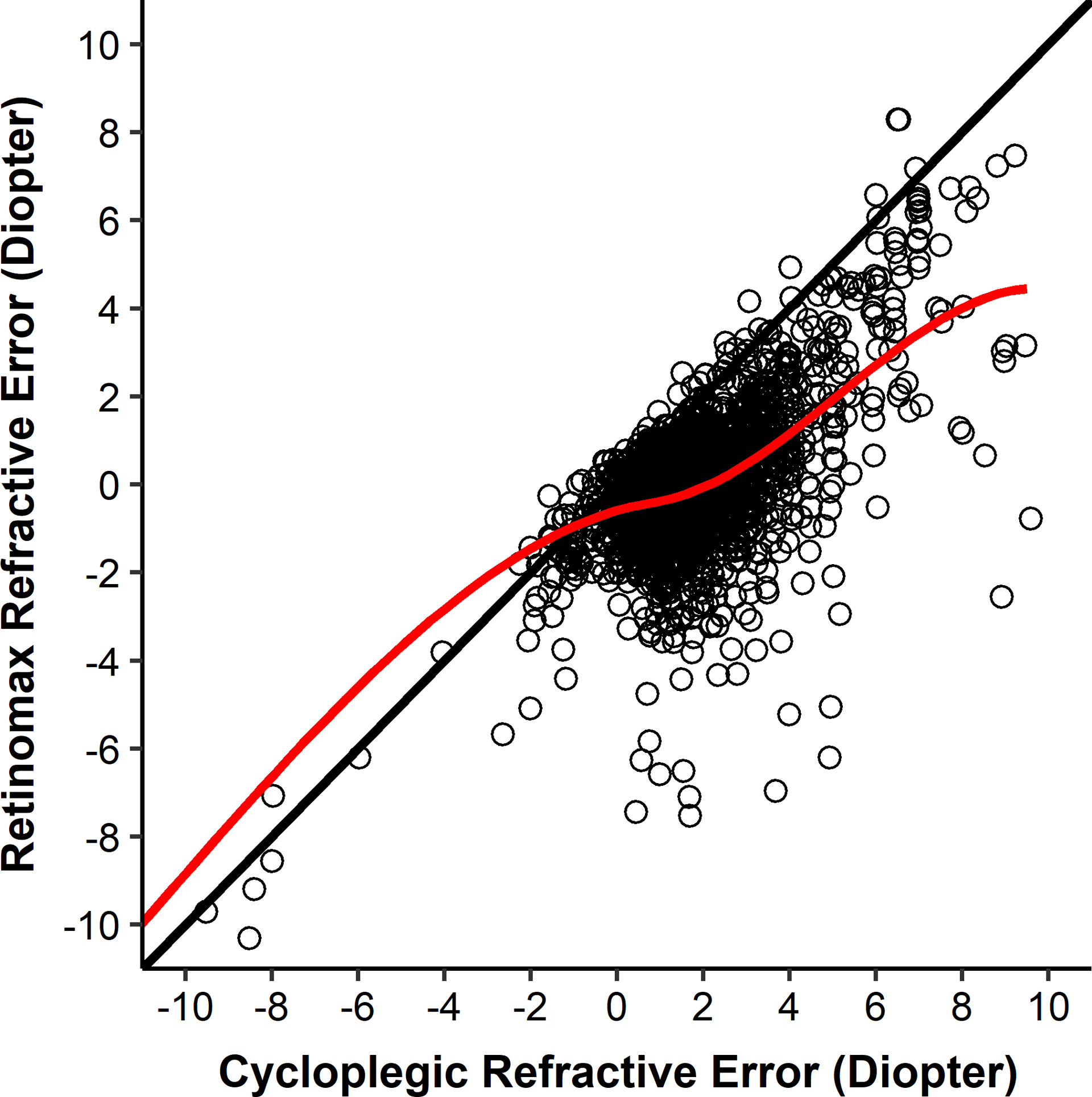

The magnitude of the sphere (most positive meridian) from each of the screening devices were compared to the magnitude of the sphere from cycloplegic refraction for each eye of the full group of 1430 children. The sphere magnitudes from the Retinomax on the LOWESS curve (red curve, Figure 1) were approximately 1.75 D less hyperopic than the magnitudes from cycloplegic refraction when the magnitude was >1.00 D from cycloplegic refraction.

Figure 1.

Sphere (most positive meridian) values from the Retinomax and cycloplegic retinoscopy. The line of equality is black. The LOWESS curve is red.

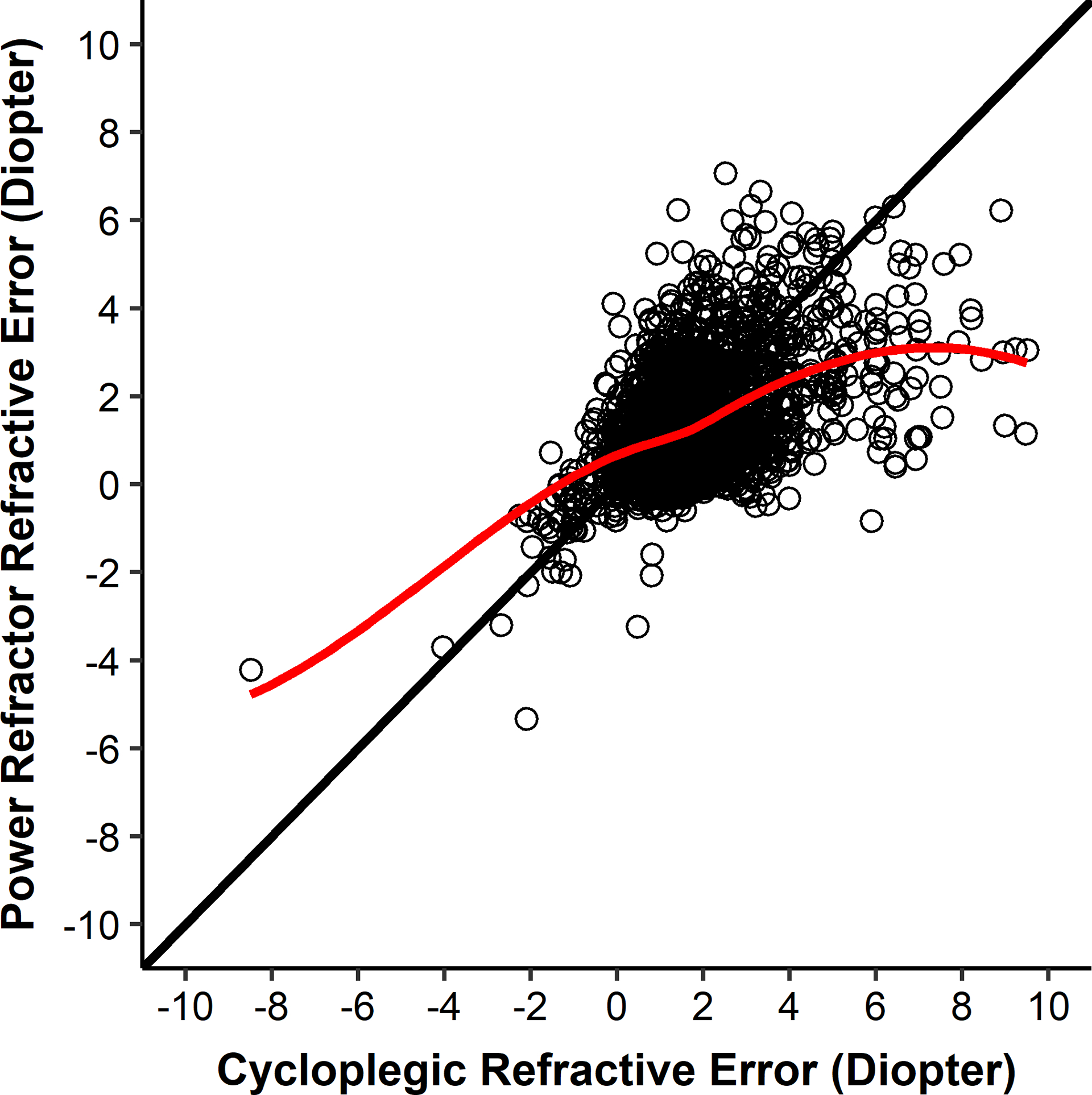

Sphere magnitudes on the LOWESS curve from the Power Refractor II were similar to the magnitudes from cycloplegic refraction up to approximately 4.00 D (Figure 2). When the sphere magnitude from cycloplegic refraction was greater than approximately 4.00 D, the sphere magnitudes from the Power Refractor II on the LOWESS curve plateaued at approximately 3.50 D.

Figure 2.

Sphere (most positive meridian) values from the Power Refractor II and cycloplegic retinoscopy. The line of equality is black. The LOWESS curve is red.

DISCUSSION

Our results from the VIP Study showed that at 90% specificity, the sensitivity of the Power Refractor II for detecting significant hyperopia was approximately 10% less than the sensitivity (approximately 80%) by the Retinomax. This difference was observed when using both the AAPOS and VIP definitions of significant hyperopia. The sensitivity of the Power Refractor II for detecting significant hyperopia was similar to the sensitivity of the Retinomax when referral criteria recommended by PediaVision were used; however, specificity for the Power Refractor II was approximately 10% lower than the 90% for the Retinomax. A decrease in specificity from 90% to 80% doubles the number of false positives and decreases the positive predictive value for the Power Refractor II from approximately 60% to 43% (data not shown), assuming a prevalence of 20% for all targeted conditions combined.10,28

Although the Plusoptix Power Refractor II model is no longer commercially available, later Plusoptix models and other devices using the eccentric photorefraction technology are available for purchase. Our data demonstrate the impact of limitations resulting from the underlying optical principle of eccentric photorefraction.18–20 The analyses presented here reiterate the need for users of the devices to be aware of the manufacturers’ stated measurement range when performing vision screenings.21,22 When screening preschool children, the potential for an eccentric photorefractor to miss larger amounts of hyperopic defocus, as a result of the underlying sensitivity of the optical approach, must be taken into consideration. The SPOT Vision Screener (Welch Allyn Inc, Skaneateles Falls, New York) also uses the eccentric photorefraction approach. Inaccurate estimation of spherical refractive error with these devices has been reported for children of various ages in studies with smaller numbers of hyperopic children and/or with a more limited range of hyperopia.11,29–31

Retinomax findings were consistently about 1.75 D less hyperopic than cycloplegic retinoscopy when hyperopia was >1.00 D on cycloplegic retinoscopy. This constant difference between the Retinomax reading and the magnitude of hyperopia by cycloplegic refraction allows referral criteria to be set to detect most children with significant hyperopia without an excessive number of false positives. In order to have similar sensitivity as the Retinomax, the Power Refractor’s referral criterion for significant hyperopia must be set at a value lower than the plateau value in Figure 2. This lower referral criterion results in substantially more false positives, approximately 10%. A higher percentage of false positives (lower specificity) has important implications for screening programs in schools and other community settings. Because the prevalence of targeted conditions in most screening populations is low, relatively small changes in the false positive rate can increase substantially the number of children referred for examination. For example, if 1000 children were screened and the percentage of children with VIP targeted conditions were 10%, the number of children referred who did not have a targeted condition (false negatives) would be 90 for the Retinomax and 195 for the Power Refractor II (Table 3 - PediaVision referral criteria), an increase of 100. Each would refer less than 100 with a targeted condition. Because the costs of arranging for and carrying out an eye examination are relatively high, such an increase in the proportion of referred children who are normal increases the cost of the screening program without referring more children who actually have a condition.

The manufacturers’ stated upper limits of reliable readings for hyperopia for devices using eccentric photorefraction technology are +5.00 D (Plusoptix models) to +7.50 D (SPOT Vision Screener). We found that, approximately 15% of the readings among children with significant hyperopia were classified as Unable while approximately 3% of readings among non-hyperopic children were classified as Unable. Considering children classified as Unable as screening failures is therefore an important component contributing to the sensitivity of the Power Refractor (approximately one-third of children with an Unable result had significant hyperopia). Aside from refractive errors that are out of the device’s range, inadequate pupil size and lack of cooperation by the child also can result in an Unable classification. Changes in later Plusoptix models may lead to lower rates of Unable because of improvements in the fixation target (from the camera front only to the addition of a smiling face) and in the ease of positioning the camera by screening personnel.

This study has some limitations. The participating children were all attending preschool and were all enrolled in Head Start, a program for low-income families. Therefore, these results may not apply to other age groups or income groups. While our overall sample size was large and enriched with children who had failed a preschool vision screening prior to enrollment in the VIP study, there were only 132 or 166 (depending on definition of significant hyperopia) with moderate to high hyperopia. This is, however, the largest reported cohort to date of moderate to highly hyperopic children evaluated with photorefraction.

Because of the association of moderate to high hyperopia with amblyopia, strabismus, lower preschool literacy, reduced near visual acuity, worse stereopsis, and inaccurate accommodation, detecting children with moderate to high hyperopia is important. When developing a vision screening program, the potential for automated devices that employ eccentric photorefraction to miss significant hyperopia or to increase false positive referrals must be taken into consideration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services by grants R01EY021141, U10EY12534, U10EY12545, U10EY12547, U10EY12550, U10EY12644, U10EY12647, and U10EY12648.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cotter SA, Varma R, Tarczy-Hornoch K, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Childhood Strabismus: The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease And Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies. Ophthalmology 2011;118:2251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donahue SP, Arthur B, Neely DE, et al. Guidelines for Automated Preschool Vision Screening: A 10-Year, Evidence-Based Update. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2013;17:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascual M, Huang J, Maguire MG, et al. Risk Factor for Amblyopia in the Vision In Preschoolers (VIP) Study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:622–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Ophthalmology Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Preferred Practice Panel. Pediatric Eye Evaluations Preferred Practice Pattern. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2017. Available at: https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/pediatric-eye-evaluations-ppp-2017. Accessed September 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar S, Evans MA, Bobier WR. Hyperopia and Emergent Literacy of Young Children: Pilot Study. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:1031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarczy-Hornoch K, Varma R, Cotter SA, et al. Risk Factors for Decreased Visual Acuity in Preschool Children: The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies. Ophthalmology 201;118:2262–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The VIP-HIP Study Group. Uncorrected Hyperopia and Preschool Early Literacy. Ophthalmology 2016; 123:681–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciner EB, Kulp MT, Maguire MG, et al. Visual Function Of Moderately Hyperopic 4- and 5-Year-Old Children in the Vision In Preschoolers-Hyperopia In Preschoolers Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;170:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulp MT, Dobson V, Peskin E, et al. The Electronic Visual Acuity Tester: Testability in Preschool Children. Optom Vis Sci 2004;81:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein E, Donahue SP. Preschool Vision Screening: Where We Have Been and Where Are We Going. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;194:xviii–xxiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paff T, Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Wolterbeek R, et al. Screening for Refractive Errors in Children: The Plusoptix S08 and the Retinomax K-Plus2 Performed by a Lay Screener Compared to Cycloplegic Retinoscopy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2010;14:478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez I, Ortiz-Toquero S, Martin R, de Juan V. Advantages, Limitations, and Diagnostic Accuracy of Photoscreeners in Early Detection of Amblyopia: A Review. Clinical Ophthalmology 2016:10 1365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Wang J, Li Y, Jiang B. Diagnostic Test Accuracy of Spot And Plusoptix Photoscreeners in Detecting Amblyogenic Risk Factors in Children: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2019;39:260–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vision In Preschoolers (VIP) Study Group. Comparison of Preschool Vision Screening Tests as Administered by Licensed Eye Care Professionals in the Vision In Preschoolers (VIP) Study. Ophthalmology 2004;111:637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vision In Preschoolers (VIP) Study Group. Preschool Vision Screening Tests Administered by Nurse Screeners Compared to Lay Screeners in the Vision In Preschoolers Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46:2639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying GS, Maguire M, Quinn G, Kulp MT, Cyert L, Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) Study Group. ROC Analysis of the Accuracy of Noncycloplegic Retinoscopy, Retinomax Autorefractor and Suresight Vision Screener for Preschool Vision Screening. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:9658–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulp MT, Ying G-S, Huang J, et al. Accuracy of Noncycloplegic Retinoscopy, Retinomax Autorefractor and Suresight Vision Screener for Detecting Significant Refractive Errors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:1378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plusoptix, Inc. Device Comparison. Available at: https://Plusoptix.com/fileadmin/Images/Products/Vision-Screening/Comparison/1904_Plusoptix_GV_SCR_USA_Letter_L2.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2020.

- 19.Nikon, Inc. Nikon Auto Refract-Keratometer Retinomax K-plus 2 Instructions. http://www.eyetech-optical.com/pdf/Nikon_Retinomax_KPlus-2.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2020.

- 20.Erdurmus M, Yagci R, Karadag R, Durmus M. A Comparison of Photorefraction and Retinoscopy in Children. J AAPOS 2007;11:606–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaeffel F, Hagel G, Eikermann J, Collett T. Lower-field Myopia and Astigmatism in Amphibians and Chickens. J Opt Soc Am (A) 1994;11:487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roorda A, Campbell MC, Bobier WR. Slope-based Eccentric Photorefraction: Theoretical Analysis of Different Light Source Configurations and Effects of Ocular Aberrations. J Opt Soc Am (A) 1997;14:2547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Thibos LN, Candy TR. Two-dimensional Simulation of Eccentric Photorefraction Images for Ametropes: Factors Influencing the Measurement. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2018;38:432–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes JM, Beck RW, Repka MX, et al. The Amblyopia Treatment Study Visual Acuity Testing Protocol. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulp MT, Ying GS, Huang J, et al. Associations between Hyperopia and Other Vision and Refractive Error Characteristics. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91:383–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drover JR, Felius J, Cheng CS, et al. Normative Pediatric Visual Acuity Using Single Surrounded HOTV Optotypes on the Electronic Visual Acuity Tester Following the Amblyopia Treatment Study Protocol. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2008;12:145–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singman E, Matta N, Tian J, Silbert D. A Comparison of Referral Criteria Used by the Plusoptix Photoscreener. Strabismus 2013;21:190–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinori M, Molina I, Hernandez EO, et al. The Plusoptix Photoscreener and the Retinomax Autorefractor as Community-Based Screening Devices for Preschool Children. Curr Eye Res. 2018;43:654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman S, Peterseim MM, Trivedi RH, et al. Detecting High Hyperopia: The Plus Lens Test and the Spot Vision Screener. J Pediat Ophth Strab 2017;54:163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan G, Russo D, Taylor C, et al. Validity of the Spot Vision Screener in Detecting Vision Disorders in Children 6 Months to 36 Months of Age. J AAPOS 2019;23:278–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaiser H, Moore B, Srinivasan G, et al. Detection of Amblyogenic Refractive Error Using the Spot Vision Screener in Children. Optom Vis Sci 2020;97:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]