Abstract

The present study was designed to evaluate the use of variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) and IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses in combination as a two-step strategy for discrimination (as measured by the Hunter-Gaston Discrimination Index [HGDI]) of both high- and low-copy-number IS6110 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates compared to IS6110-RFLP alone with an unselected collection of isolates. Individually, IS6110-RFLP fingerprinting produced six clusters that accounted for 69% of the low-copy-number IS6110 isolates (five clusters) and 5% of the high-copy-number IS6110 isolates (one cluster). A total of 39% of all the isolates were clustered (HGDI = 0.97). VNTR analysis generated a total of 35 different VNTR allele profile sets from 93 isolates (HGDI = 0.938). Combining IS6110-RFLP analysis with VNTR analysis reduced the overall percentage of clustered isolates to 29% (HGDI = 0.988) and discriminated a further 27% of low-copy-number isolates that would have been clustered by IS6110-RFLP alone. The use of VNTR analysis as an initial typing strategy facilitates further analysis by IS6110-RFLP, and more importantly, VNTR analysis subdivides some IS6110-RFLP-defined clusters containing low- and single-copy IS6110 isolates.

The genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been shown to contain several polymorphic repetitive DNA elements that can be used to discriminate between isolates. Repetitive DNA elements which have been used in molecular typing studies include insertion sequences (IS), such as IS6110, the direct repeat elements (DR), the major polymorphic tandem repeat sequences (PGRS), the polymorphic GC-rich tandem repeat sequences (MPTR), (GTG)5, and exact tandem repeat (ETR) sequences (10, 13, 15, 27, 28, 35, 38). Studies have shown that combinations of molecular typing methods utilizing different repetitive elements may improve discrimination between M. tuberculosis isolates (4, 18, 35, 37).

The method which is used most commonly for investigating the epidemiology of infection by M. tuberculosis is IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (IS6110-RFLP) analysis (30). This method is based on the observation that RFLP patterns among non-epidemiologically related isolates show a high degree of variation (16, 21, 31). Patients infected by strains with identical IS6110-RFLP patterns (or one band difference) are considered epidemiologically related (24, 31). M. tuberculosis isolates having identical IS6110 fingerprints potentially represent the recent transmission of the isolate within a population and are likely to be part of a chain of transmission.

Different sites within the genome of M. tuberculosis have been reported as hot spots for the integration of IS6110. These include the DR locus, the ipl locus, the DK1 locus, and the dnaA-dnaN region (7, 9, 15, 19). This suggests that the integration of IS6110 is not a truly random event and the frequency of transposition is influenced by the site of insertion within the mycobacterial genome (22, 36). The identification of IS6110 insertion hot spots may complicate the interpretation of IS6110-RFLP data. For strains containing low copy numbers of IS6110, integration hotspots may produce “false” clusters which must be subdivided by a second typing method independent of IS6110 (3, 6, 12, 14, 26, 29, 35, 37, 40, 41).

Despite the widespread use of IS6110-RFLP, this method is both technically demanding and time consuming. The comparison of large numbers of RFLP fingerprints, even with the introduction of computerized gel documentation systems, can still be problematic. The ideal system for the documentation of typing data would be a simple typing method, which produces a digital profile. Variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis is one typing method which produces such data (10). VNTR analysis consists of the PCR amplification of five separate ETR sequences (ETR-A to ETR-E). These loci are polymorphic due to the addition or deletion of repeats. The size of PCR product produced at each locus corresponds to the number of repeats. A five-digit numerical allele profile is generated which can be simply stored in either a database or spreadsheet format.

VNTR analysis has been shown to be reproducible both within and between laboratories (11, 18; R. Frothingham, P. L. Strickland, K. A. Davis, A. J. Cobb, D. M. Gascoyne-Binzi, C. Sola, M. A. Behr, and K. Kremer, Tuberculosis: Past, Present and Future [meeting], abstr. 170, 2000). However, studies have shown that VNTR analysis does not offer the same degree of strain discrimination as methods based on IS6110 (18, 39). Since VNTR analysis detects polymorphisms in five independent genetic loci, it would be a useful method for subdividing isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110, which are poorly discriminated by IS6110-RFLP (18; Frothingham et al., Tuberculosis: Past, Present and Future [meeting], abstr. 170).

This retrospective study was designed to compare VNTR analysis, as an initial typing step in a combined strategy to discriminate both high- and low-copy-number IS6110 M. tuberculosis isolates, with IS6110-RFLP alone. The level of discrimination for each typing method was calculated using the Hunter-Gaston Discriminatory Index (HGDI) (17). The HGDI is a mathematical model based on the probability of two strains in a test population being characterized as unrelated by the typing method in question and may be used to compare typing methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA from 93 cultures of M. tuberculosis isolated from an unselected population from Tanzania were obtained as previously described (12). Each DNA sample had been analyzed previously by IS6110-RFLP as described by van Soolingen (12, 33). Isolates which generated five or fewer bands were defined as low IS6100 copy number, and those with nine or more bands were considered high copy number. Forty-eight isolates were identified as having a low copy number of IS6110 (of which 19 possessed a single copy of IS6110), and 42 were identified as high-copy-number IS6110 isolates. IS6110-RFLP data was unavailable for three isolates due to their nonviability (12). In this study, an IS6110-RFLP cluster was defined as a collection of isolates that shared 100% fingerprint identity.

VNTR analysis.

VNTR analysis was performed using the primers for the five loci ETR-A to ETR-E as described by Frothingham and Meeker-O'Connell (10) (Table 1). Each PCR was carried out in a final volume of 25 μl containing 25 pmol of the appropriate primer pair, 2.5 μl of GeneAmp PCR Buffer II (PE Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP mix (Amersham), 4% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.2 U of AmpliTaq Gold (PE Applied Biosystems), and 1 ng of template DNA. Following an initial denaturation at 95°C for 12 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min were performed. The PCR was completed by a final extension phase of 72°C for 5 min.

TABLE 1.

Summary of PCR primers used for VNTR analysis and ETR repeat sizes

| Locus designation | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Repeat size in H37RV (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| ETR-A | AAATCGGTCCCATCACCTTCTTAT | 75 |

| CGAAGCCTGGGGTGCCCGCGATTT | ||

| ETR-B | GCGAACACCAGGACAGCATCATG | 57 |

| GGCATGCCGGTGATCGAGTGG | ||

| ETR-C | GTGAGTCGCTGCAGAACCTGCAG | 58 |

| GGCGTCTTGACCTCCACGAGTG | ||

| ETR-D | CAGGTCACAACGAGAGGAAGAGC | 77 |

| GCGGATCGGCCAGCGACTCCTC | ||

| ETR-E | CTTCGGCGTCGAAGAGAGCCTC | 53 |

| CGGAACGCTGGTCACCACCTAAG |

Amplicons were separated through a 2% Metaphor Agarose (Flowgen, Ashby de la Zouch, United Kingdom) gel in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. The number of repeats for each VNTR locus was calculated from the size of the PCR amplicon (10).

Cluster analysis.

For VNTR analysis, the number of repeats for each VNTR locus was recorded as a five-digit allele profile which was stored and sorted using an Access database (version 2.0; Microsoft). A VNTR profile set was defined as a collection of isolates that shared identical VNTR allele profiles. A single step transition in the number of repeats at any given VNTR locus was calculated to reduce VNTR profile similarity by 5%.

Once VNTR profile sets had been identified, IS6110 fingerprints for the appropriate isolates were compared against each other using the GelCompar software (version 4.0; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Cluster analysis was performed by the calculation of the Dice coefficient, and similarity (as defined by the Dice coefficient) was calculated using the parameter settings at 0.8% band position tolerance (12). A combined cluster was defined as a series of isolates that had both the same VNTR allele profile and 100% IS6110 fingerprint identity. The isolate clustering data obtained by combining IS6110-RFLP and VNTR analyses for both high and low copy numbers of IS6110 were compared to those produced by IS6110-RFLP alone.

Statistical analysis.

The HGDI (17) was calculated using the following formula:

|

where D is the numerical index of discrimination, N is the total number of strains in the typing scheme, s is the total number of different strain types, and nj is the number of strains belonging to the jth type.

RESULTS

VNTR analysis.

VNTR allele profiles were generated for all 93 isolates including nonviable cultures. A total of 35 different profile sets were identified which were coded alphabetically following the numerical order of the VNTR profiles. Table 2 summarizes the VNTR profiles obtained and the number of isolates represented by each profile. VNTR analysis clustered 78% (73 of 93) of the isolates investigated, with clusters ranging in size from 2 to 17 isolates. The remaining 22% of isolates (20 of 93) generated unique VNTR allele profiles.

TABLE 2.

Summary of VNTR allele profile sets generated from 93 M. tuberculosis isolates

| No. of isolates in set | No. of VNTR profile sets | VNTR profile setsa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 21434 (D), 42236 (S), 22233 (E), 42443 (T), 23433 (H), 44466 (U), 32233 (I), 54466 (V), 32235 (J), 64366 (X), 32332 (K), 64446 (Y), 32434 (N), 65465 (Ae), 33332 (O), 65466 (Af), 34455 (P), 93454 (Ag), 42233 (Q), 94265 (Ah) |

| 2 | 7 | 12431 (A), 64464 (Ab), 22234 (F), 64467 (Ad), 32333 (L), 94465 (Ai), 61455 (W) |

| 3 | 2 | 12432 (B), 64456 (Aa) |

| 5 | 1 | 22433 (G) |

| 6 | 1 | 42234 (R) |

| 7 | 1 | 64455 (Z) |

| 9 | 2 | 21433 (C), 32433 (M) |

| 17 | 1 | 64466 (Ac) |

VNTR profile set codes in parentheses.

IS6110-RFLP.

Of the 90 samples with IS6110-RFLP fingerprint data available (42 high-copy-number and 48 low-copy-number isolates), six clusters were identified, which contained 35 isolates (39%) in total. Of these, two clusters contained all of the single-copy IS6110 isolates (Table 3, clusters 4 and 5), three clusters contained between 2 and 12 low-copy-number IS6110 isolates (Table 3, clusters 1, 2, and 3), and one cluster contained two high-copy-number isolates. Sixty-nine percent (33 of 48) of the low-copy-number isolates formed five clusters, whereas only 5% (2 of 42) of the high-copy-number isolates were clustered (Table 3, cluster 6).

TABLE 3.

Summary of the IS6110-RFLP clusters subdivided by VNTR analysis

| IS6110-RFLP cluster designation | No. of isolates in cluster | VNTR allele profile setsa | % VNTR profile similarity within cluster |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1d | 8 | U (1), 44466e | |

| Y (1), 64446e | 80–90 | ||

| Ac (6), 64466 | |||

| Cluster 2d | 4 | X (1), 64366e | |

| Ac (1), 64466e | 90–95 | ||

| Ad (2), 64467 | |||

| Cluster 3d | 2 | Ac (1), 64466e | 95 |

| Af (1), 65466e | |||

| Cluster 4b | 12 | P (1), 34455e | |

| W (1), 61455e | |||

| Z (5), 64455 | 55–85 | ||

| Aa (2), 64456 | |||

| Ah (1), 94265e | |||

| Ai (2), 94465 | |||

| Cluster 5b | 7 | M (7), 32433 | 100 |

| Cluster 6c | 2 | A (2), 12431 | 100 |

Number of isolates within VNTR profile in parentheses.

All isolates contained only a single copy of IS6110.

Isolates had a high copy number of IS6110.

All isolates contained five or fewer copies of IS6110.

These isolates were not clustered when VNTR analysis was applied before IS6110-RFLP.

IS6110-RFLP and VNTR analysis combined.

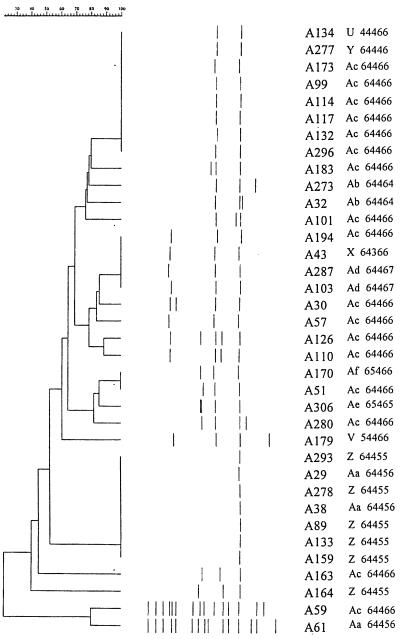

In total there were 90 samples available for combined analysis by IS6110-RFLP and VNTR. Table 3 is a summary of IS6110-RFLP-defined clusters subdivided by VNTR analysis. Seventy percent (14 of 20) of samples that had a unique VNTR allele profile also had unique IS6110-RFLP fingerprints. Those VNTR profile sets which contained two or more isolates and which carried a high copy number of IS6110 were not clustered by IS6110-RFLP (Fig. 1) except in one case (VNTR allele profile set A). This cluster contained only two high-copy-number IS6110 isolates that had both the same VNTR allele profile and identical RFLP patterns. For the 48 low-copy-number isolates (including those that contained a single copy of IS6110), the percentage of clustered isolates fell from 69% (33 of 48) when analyzed by IS6110-RFLP alone to 50% (24 of 48) when both typing systems were used. Dendrograms constructed by Gelcompar for selected VNTR profile sets are shown in Fig. 1 and 2; dendrograms for the remaining VNTR profile sets can be obtained upon request from S.H.G.

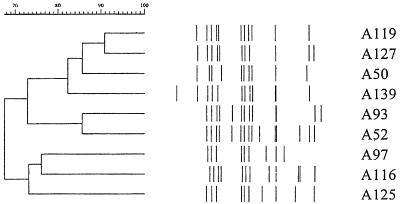

FIG. 1.

IS6110-RFLP patterns of VNTR profile set C (21433). Designations of isolates are shown at right. Numbers at the top indicate percent similarities of IS6110-RFLP patterns.

FIG. 2.

IS6110-RFLP analysis of VNTR set Ac (64466) and isolates with 90% or greater VNTR profile similarity. Designations of isolates, VNTR profile sets, and set codes are shown at right. Numbers at the top indicate percent similarities of IS6110-RFLP patterns.

Statistical analysis.

The HGDI was calculated for IS6110-RFLP, VNTR analysis, and for the two methods combined to determine the discriminatory indices for each (Table 4). When the HGDI for IS6110-RFLP analysis of low-copy-number isolates (0.892) was compared to the HGDI for the combined typing strategy (0.957), an increase in the level of discrimination was observed.

TABLE 4.

Discrimination index values (HGDI) for each typing method

| Method | HGDI value for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-copy-number isolatesa | High-copy-number isolates | Total isolates | |

| IS6110-RFLP | 0.892 | 0.999 | 0.97 |

| VNTR | N/Ab | N/A | 0.938 |

| IS6110-RFLP + VNTR | 0.957 | 0.999 | 0.988 |

Includes single-copy isolates.

N/A, not applicable (VNTR analysis does not distinguish between low and high copy numbers of IS6110).

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to evaluate the use of VNTR analysis and IS6110-RFLP in combination as a two-step strategy to discriminate unselected M. tuberculosis isolates, compared with IS6110-RFLP alone. The ability of the combined approach to subdivide isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110 (i.e., five or fewer copies) was also examined.

Individually, IS6110-RFLP fingerprinting clustered 69% (five clusters) of the low-copy-number and 5% (one cluster) of the high-copy-number IS6110 isolate. A total of 39% (35 of 90) of all the isolates were clustered (HGDI = 0.97). A total of 35 different VNTR allele profile sets were identified from 93 isolates (HGDI = 0.938), and these profiles shared between 15 and 95% VNTR profile similarity. This level of discrimination was greater than that found by Filliol et al., who identified only 12 VNTR profiles from 66 M. tuberculosis isolates (HGDI = 0.863) (8). In that study, between 75 and 95% VNTR allele profile similarity was observed between isolates. This suggests that the level of discrimination of VNTR analysis is population dependent and emphasizes the requirement of a second typing method to further define VNTR profile sets.

Combining IS6110-RFLP with VNTR analysis reduced the overall percentage of clustered isolates to 29% (26 of 90; HGDI = 0.988). For isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110, the degree of clustering decreased from 69% (33 of 48; HGDI = 0.892) to 50% (24 of 48; HGDI = 0.957). This value is comparable to a combination of spoligotyping and IS6110-RFLP, which clustered 55% of similar isolates (2). Only two high-copy-number isolates had 100% identity by IS6110-RFLP typing and VNTR analysis (VNTR profile set A, 12431). These isolates may represent recent transmission within the community.

The Haarlem and Beijing families of strains of M. tuberculosis have specific genetic markers, which include characteristic VNTR profiles (18, 32). Strains of the Haarlem family of M. tuberculosis have the VNTR allele profile 32333 and have been isolated in Asia, Europe, and the Americas (18). Among the isolates investigated in this study, only 2 out of 93 (2%) were identified with the Haarlem VNTR profile, compared to 36% (24 of 66) of isolates from the French Caribbean (8). This suggests that the Haarlem VNTR profile is not a predominant VNTR genotype in Tanzania.

The Beijing family of strains has been identified infrequently in Africa, although it is common in parts of the world, especially Asia (25, 32). Beijing strains have the VNTR profile 42435, although variation may be shown in the number of repeats at a single locus (18). Assuming these strains share 85% or greater VNTR profile similarity, five isolates (5%; 5 of 93) from this study were identified as having a Beijing VNTR profile. Spoligotyping and IS6110-RFLP analysis of isolates from Tanzania have previously produced a similar percentage of Beijing isolates (4.5%; 4 of 88) (32).

When a single repeat difference between VNTR profiles was identified (i.e., 5% difference in VNTR similarity), the isolates within these groups generally showed a relatively high degree of similarity by IS6110-RFLP analysis. For example, profiles A (12431) and B (12432) were found to have 78% similarity by IS6110-RFLP; profiles C (21433) and D (21434) showed 98% IS6110-RFLP pattern similarity. This may represent the relatively recent development of these VNTR profiles from common genetic ancestors. Conversely, VNTR profiles that had a low degree of similarity also had reduced IS6110-RFLP relatedness. For example, profile sets A (12431) and Ai (94465) showed 15% VNTR similarity and 35% IS6110 relatedness.

The most common VNTR profile set identified (Ac, 64466) accounted for 18% (17 of 93) of all the isolates analyzed. Interestingly, 71% (34 of 48) of the low-copy IS6110 isolates in the study either had the VNTR profile Ac or showed a 90% or greater VNTR profile similarity to Ac (Fig. 2). This may reflect the VNTR allele profile development of particular clones of M. tuberculosis in Tanzania. A similar pattern was noted in the French Caribbean, where 73% (48 of 66) of M. tuberculosis isolates were clustered into 12 VNTR profile sets (8). Thirty-three percent (24 of 66) of all isolates examined had the Haarlem VNTR profile (32333), and a further 27% (18 of 66) isolates showed 90% or greater VNTR profile similarity (8). This suggests that there is a predominance of M. tuberculosis isolates with similar VNTR profiles within discrete geographical areas and that evolution of these strains is being reflected by the VNTR profiles in the community. This supports the hypothesis that evolution of strains may be studied using VNTR analysis (8).

The stability of VNTR allele profiles in M. tuberculosis has not been determined to date. M. tuberculosis H37 was isolated in 1905, and the two variants H37Rv and H37Ra were identified during the 1930s. These variants show different IS6110-RFLP profiles but still share the same VNTR profile (10, 18, 20, 30). The estimated minimum time for a single step transition at a VNTR locus is 65 years, slower than the predicted rate of change for an IS6110-RFLP pattern (1, 5, 23, 24, 34, 42). It has been suggested that IS6110-RFLP fingerprints in documented transmission chains show a higher degree of stability than that observed for serial patient-derived isolates (24). Since VNTR allele profiles are stable over long periods of time, it is likely that the VNTR allele profiles of serial patient-derived and epidemiologically related isolates will remain constant over time, unlike IS6110-RFLP fingerprints, which are reported to vary by one to two bands.

In conclusion, for isolates that contained a high copy number of IS6110, VNTR analysis produced large clusters that were subdivided further by IS6110-RFLP. For isolates containing a single copy or low copy numbers of IS6110, combined VNTR and IS6110-RFLP analysis distinguished a further 27% (9 of 33) that would have been clustered by IS6110-RFLP alone. The use of VNTR analysis as an initial typing strategy produces small, manageable collections of isolates, facilitating further investigations by more discriminatory typing techniques, such as IS6110-RFLP. More importantly, VNTR analysis may provide additional discrimination for typing of isolates that contain a single copy or a low copy number of IS6110.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Wellcome grant number 054885).

We thank R. Frothingham (Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, N.C.) for helpful discussions and advice regarding VNTR analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alito A, Morcilli N, Scipioni S, Dolmann A, Romano M I, Cataldi A, van Soolingen D. The IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism in particular multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains may evolve too fast for reliable use in outbreak investigation. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:788–791. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.788-791.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer J, Andersen A B, Kremer K, Miorner H. Usefulness of spoligotyping to discriminate IS6110 low-copy-number Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains cultured in Denmark. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2602–2606. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2602-2606.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burman W J, Reves R R, Hawkes A P, Rietmeijer C A, Yang Z H, el Hajj H, Bates J H, Cave M D. DNA fingerprinting with two probes decreases clustering of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1140–1146. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaves F, Yang Z, El Hajj H, Alonso M, Burman W J, Eisenach K D, Dronda F, Bates J H, Cave M D. Usefulness of the secondary probe pTBN12 in DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1118–1123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1118-1123.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Boer A S, Borgdorff M W, de Haas P E W, Nagelkerke N J D, van Embden J D A, van Soolingen D. Analysis of rate of change of IS6110 RFLP patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on serial patient isolates. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1238–1244. doi: 10.1086/314979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De la Salmoniere Y O G, Li H M, Torrea G, Bunschoten A, van Embden J D A, Gicquel B. Evaluation of spoligotyping in a study of the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2210–2214. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2210-2214.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang Z, Forbes K J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 preferential locus (ipl) for insertion into the genome. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:479–481. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.479-481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filliol I, Ferdinand S, Negroni L, Sola C, Rastogi N. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on variable number of tandem repeats used alone and in association with spoligotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2520–2524. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2520-2524.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fomukong N, Beggs M, el Hajj H, Templeton G, Eisenach K, Cave M D. Differences in the prevalence of IS6110 insertion sites in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains: low and high copy number of IS6110. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;78:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frothingham R, Meeker-O'Connell W A. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable number tandem repeats. Microbiology. 1998;144:1189–1196. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gascoyne-Binzi D M, Barlow R E L, Frothingham R, Robinson G, Collyns T A, Gelletlie R, Hawkey P. Rapid identification of laboratory contamination with Mycobacterium tuberculosis using variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:69–74. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.69-74.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillespie S H, Dickens A, McHugh T D. False molecular clusters due to nonrandom association of IS6110 with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2081–2086. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2081-2086.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal M, Young D, Zhang Z, Jenkins P A, Shaw R J. PCR amplification of variable sequences upstream of katG gene to subdivide strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3070–3071. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3070-3071.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyal M, Saunders N A, van Embden J D A, Young D B, Shaw R J. Differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates by spoligotyping and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:647–651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.647-651.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermans P W M, van Soolingen D, Bik E M, de Haas P E W, Dale J W, van Embden J D A. The insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2695-2705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermans P W M, van Soolingen D, Dale J W, Schuitema A R J, McAdam R A, Catty D, van Embden J D A. Insertion element IS986 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a useful tool for the diagnosis and epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2051–2058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2051-2058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter P R, Gaston M A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer K, van Soolingen D, Frothingham R, Haas W H, Hermans P W M, Martin C, Palittapongarnpim P, Plikaytis B B, Riley L W, Yakrus M A, Musser J M, van Embden J D A. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2607–2618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2607-2618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kupepina N E, Sreevatsan S, Plikaytis B B, Bifani P J, Connell N D, Donnelly R J, van Soolingen D, Musser J M, Kreiswirth B N. Characterization of the phylogenetic distribution and chromosomal insertion sites of five IS6110 elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: non-random integration in the dnaA-dnaN region. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:31–42. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lari N, Rindi L, Lami C, Garzelli C. IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and H37Ra. Microb Pathog. 1999;26:281–286. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazurek G H, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Wallace R J, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Chromosomal DNA fingerprint patterns produced with IS6110 as strain-specific markers for epidemiologic study of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2030–2033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.2030-2033.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHugh T D, Gillespie S H. Nonrandom association of IS6110 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for molecular epidemiological studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1410–1413. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1410-1413.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niemann S, Richter E, Rusch Gerdes S. Stability of IS6110 restriction length polymorphism patterns of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3078-3079.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niemann S, Rüsch-Gerdes, Richter E, Thielen H, Heykes-Uden H, Diel R. Stability of IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in actual chains of transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2563–2567. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2563-2567.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park Y, Bai G, Kim S. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from countries in the Western Pacific region. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:191–197. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.191-197.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portugal I, Maia S, Moniz-Pereira J. Discrimination of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 fingerprint subclusters by rpoB gene mutations. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3022–3024. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3022-3024.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross B C, Raios K, Jackson K, Dwyer B. Molecular cloning of a highly repetitive DNA element from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its use as an epidemiological tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:942–946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.942-946.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thierry D, Brisson-Noel A, Vincent-Levy-Frebault V, Nguyen S, Guesdon J, Gicquel B. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence, IS6110, and its application in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2668–2673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2668-2673.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torrea G, Levee G, Grimont P, Martin C, Chanteau S, Gicquel B. Chromosomal DNA fingerprint analysis using the insertion sequence IS6110 and the repetitive element DR as strain-specific markers for epidemiological study of tuberculosis in French Polynesia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1899–1904. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1899-1904.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M. Epidemiology of tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(Suppl. 20):649s–656s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Soolingen D, Qian L, de Haas P E W, Douglas J T, Traore H, Portaels F, Zi Qing H, Enkhsaikan D, Nymadawa P, van Embden J D A. Predominance of a single genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in countries of East Asia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3234–3238. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3234-3238.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Hermans P W M, van Embden J D A. DNA-fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:196–205. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Hass P E W, Soll D R, van Embden J D A. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Hermans P W, Groenen P M A, van Embden J D A. Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1987–1995. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.1987-1995.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wall S, Ghanekar K, McFadden J, Dale J W. Context-sensitive transposition of IS6110 in mycobacteria. Microbiology. 1999;145:3169–3176. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warren R, Richardson M, Sampson S, Hauman J H, Beyers N, Donald P R, van Helden P D. Genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with additional markers enhances accuracy in epidemiological studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2219–2224. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2219-2224.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiid I J F, Werely C, Beyers N, Donald P, van Helden P D. Oligonucleotide (GTG)5 as a marker for strain identification in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1318–1321. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1318-1321.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaganehdoost A, Graviss E A, Ross M W, Adams G J, Ramaswamy S, Wanger A, Frothingham R, Soini H, Musser J M. Complex transmission dynamics of clonally related virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with barhopping by predominantly human immunodeficiency virus-positive gay men. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1245–1251. doi: 10.1086/314991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z, Barnes P F, Chaves F, Eisenach K D, Weis S E, Bates J H, Cave M D. Diversity of DNA fingerprints of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1003–1007. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1003-1007.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Z, Chaves F, Barnes P F, Burman W J, Koehler J, Eisenach K D, Bates J H, Cave M D. Evaluation of a method for secondary DNA typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with pTBN12 in the epidemiological study of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3044–3048. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3044-3048.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeh R W, Ponce de Leon A, Agasino C B, Hahn J A, Daley C L, Hopewell P C, Small P M. Stability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA genotypes. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1107–1111. doi: 10.1086/517406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]