Abstract

G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest superfamily of cell-surface proteins. However, the expression and function of majority of GPCRs remain unexplored in breast cancer (BC). We interrogated the expression and phosphorylation status of 398 non-sensory GPCRs using the landmark BC proteogenomics and phosphoproteomic dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Neuropeptide Y Receptor Y1 (NPY1R) gene and protein expression were significantly higher in Luminal A tumors versus other BC subtypes. The trend of NPY1R gene, protein, and phosphosite (NPY1R-S368s) expression was decreasing in the order of Luminal A, Luminal B, Basal, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) subtypes. NPY1R gene expression increased in response to estrogen and reduced with endocrine therapy in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) BC cells and xenograft models. Conversely, NPY1R expression decreased in ER+ BC cells resistant to endocrine therapies (estrogen deprivation, tamoxifen, and fulvestrant) in vitro and in vivo. NPY treatment reduced estradiol-stimulated cell growth, which was reversed by NPY1R antagonist (BIBP-3226) in ER+ BC cells. Higher NPY1R gene expression predicted better relapse-free survival and overall survival in ER+ BC. Our study demonstrates that NPY1R mediates the inhibitory action of NPY on estradiol-stimulated growth of ER+ BC cells, and its expression serves as a biomarker to predict endocrine sensitivity and survival in ER+ BC patients.

Subject terms: Cancer, Biomarkers

Introduction

Approximately 75–80% of breast cancer (BC) are estrogen receptor-positive (ER+)1, indicating their growth stimulation by estrogen. Endocrine therapies, which include tamoxifen (Tam), aromatase inhibitors, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptor agonists, and fulvestrant are the standard of care treatment options for ER+ BC2–5. The use of endocrine therapies significantly improves long-term outcomes in early- and advanced-stage ER+ BC. However, intrinsic or acquired resistance occur frequently with all endocrine therapies, resulting in disease relapse and poor survival6–9. Therefore, the development of biomarkers to predict endocrine resistance and effective drug targets to overcome endocrine resistance is of utmost importance in ER+ BC.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are highly ‘druggable’ targets. Nearly 30–50% of all Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs target various GPCRs or their pathways and are often used to treat various chronic diseases due to their excellent safety profile10–15. Several GPCRs and/or their ligands have been implicated in cancer cell biology playing a role in multiple cellular processes including cell growth, proliferation, survival, invasion, and migration16–23. But, GPCRs have not been systematically explored as biomarkers or drug targets in BC. While genetic aberrations in kinases and transcription factors are thought to contribute to cancer development24, these alterations are not very common in GPCRs. However, posttranslational modification such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which affects GPCR activity25–28, might be highly relevant for controlling various cellular processes important in cancer biology.

The goal of this study was to interrogate the altered expression and phosphorylation of various GPCRs in BC using provisional proteomic and phosphoproteomic data from National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (NCI-CPTAC). Previously, phosphoproteome profiling of breast cohort by Mertins et al. have identified a subgroup with differential GPCR activity and role in BC29. Here, we evaluated the proteome and phosphoproteome data of 398 non-sensory GPCRs [International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology/British Pharmacological Society (IUPHAR/BPS) Guide to Pharmacology, IUPHAR v1.0] using the landmark The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) BC proteogenomic dataset. We also assessed the expression of Neuropeptide Y Receptor Y1 (NPY1R), the topmost hypo-phosphorylated (at S368s) GPCR in BC patient samples. We found that NPY1R serves as a predictor of endocrine sensitivity and of long-term outcomes in ER+ BC.

Methods

Selection of proteomic and phosphoproteomic data

The published datasets from the TCGA BC proteogenomics analysis by Mertins et al. were used in this study29. The datasets included 77 primary breast tumors for which comprehensive, quantitative mass-spectrometry-based proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses were performed. The data were represented as protein-level or phosphosite-level log2-transformed iTRAQ (Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation) ratio. The iTRAQ ratio was calculated using the median of all PSM (peptide spectrum match) level ratios contributing to a protein subgroup or phosphosite29. The data were normalized where log-ratios centered around zero, and up- or down-regulated proteins or phosphosites were characterized in comparison to the reference (pooled samples). GPCRs from the proteomics data (18 identified proteins), and phosphoproteomics data (136 identified phosphosites) were selected for further analysis (The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology, IUPHAR v1.0; https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/).

RNA Expression data for BC patients and cell lines

The Firehose Genome Data Analysis Center (GDAC) portal was used to download processed TCGA RNA-Seq data (Illumina HiSeq)30. The Log2 transformed normalized RSEM count data for tumor samples (n = 1093) were extracted. The PAM50 annotation was used for samples with Luminal A (LumA) (n = 415), Luminal B (LumB) (n = 176), Basal (n = 136) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (n = 65) as previously described31. Further, the paired samples (tumor and normal) were extracted (n = 112) from the Illumina HiSeq dataset. NPY1R expression across TCGA cancer cohort was obtained from human protein atlas (HPA)32. BC subtype-specific expression of NPY1R was analyzed using the METABRIC dataset33. The Broad Institute Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database was used to analyze mRNA expression of NPY1R across BC cell lines of different molecular subtypes34.

NPY1R expression from published affymetrix microarray and RNA-seq data

NPY1R gene expression was assessed in the following publicly available datasets from our group: (i) time-dependent expression with estradiol-treatment in MCF7, T47D, and BT474 cells35–37; (ii) in response to various endocrine therapies in MCF7 and T47D cells; (iii) parental cells and their estrogen deprivation-resistant (EDR), Tam-resistant (TamR), and fulvestrant-resistant (FulR) derivatives of MCF7, T47D, and ZR75-1 BC cells grown in vitro38 and (iv) in xenograft tumors generated from MCF7 parental, EDR, TamR, and FulR derivatives in viv 36,37.

Drugs

17β-estradiol (E2) (catalog #E2758) and Neuropeptide Y (NPY) human (catalog #N5017) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. BIBP-3226 trifluoroacetate (catalog #2707) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience.

Cell lines and establishment of resistant lines

The human BC cells MCF7 (MCF7L, originally from Dr. Marc Lippman’s lab) and T47D (purchased from ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin-Glutamine (PSG). The endocrine resistant derivatives, EDR of MCF7 and T47D cells were generated using a previously published method39. These cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% Charcoal stripped serum and 1% PSG.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

NPY1R gene expression was assessed in MCF7 and T47D cells grown in charcoal-stripped media were treated with E2, estrogen deprivation (ED), or ED + tamoxifen (Tam). qPCR analysis was performed as previously described40. NPY1R primers-probe (cat# 4448892, Assay ID: Hs00702150_s1, ThermoFisher) were used. The fold change data were plotted as relative quantification RQ (2(− ddct))41.

Immunoblotting

NPY1R protein expression was evaluated in parental and EDR derivatives of MCF7, T47D, and ZR75-1 cells by immunoblotting. Briefly, cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer (catalog# 9803S, Cell Signaling Technology) and cell membrane proteins were extracted using Mem-PER™ Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit (catalog #89842, ThermoFisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. NPY1R expression was detected using anti-NPY1R primary antibody (catalog #NBP1-59008, Novus Biologicals). Ponceau staining was used to assess equal loading of cell membrane proteins.

Cell proliferation assay

The cell growth and viability were assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay kit (catalog #30-1010K™, ATCC®). Briefly, MCF7 and T47D were grown with or without antagonist BIBP-3226 (1 µM) and plated in triplicates (10,000–15,000 cells/well) in 96-well tissue culture plates. After overnight attachment, the cells were treated with vehicle or E2 immediately followed by the addition of NPY (100 nM) in 15 min. The cell proliferation was determined after 72 h by following the MTT kit protocol.

Survival analysis

Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed using an online tool for meta-analysis of public microarray datasets42 (https://www.kmplot.com/analysis/). The impact of NPY1R expression on relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with ER+ and ER− tumors (defined by IHC) were analyzed by assessing the effects of 22,277 genes on survival in 2422 BC patients. METABRIC dataset was used to predict BC specific survival (BCSS) of LumA and LumB BC patients with high and low NPY1R expression.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses presented in the manuscript were performed using R version 3.4.043 (https://www.r-project.org/) and GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 (https://www.graphpad.com/). The t-test (paired) was used to compare paired samples otherwise stated. ANOVA analysis was performed on PAM50 subtype data and further post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s test. All analyses were presented with statistical p-value significance by appropriate methods. The probability of survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

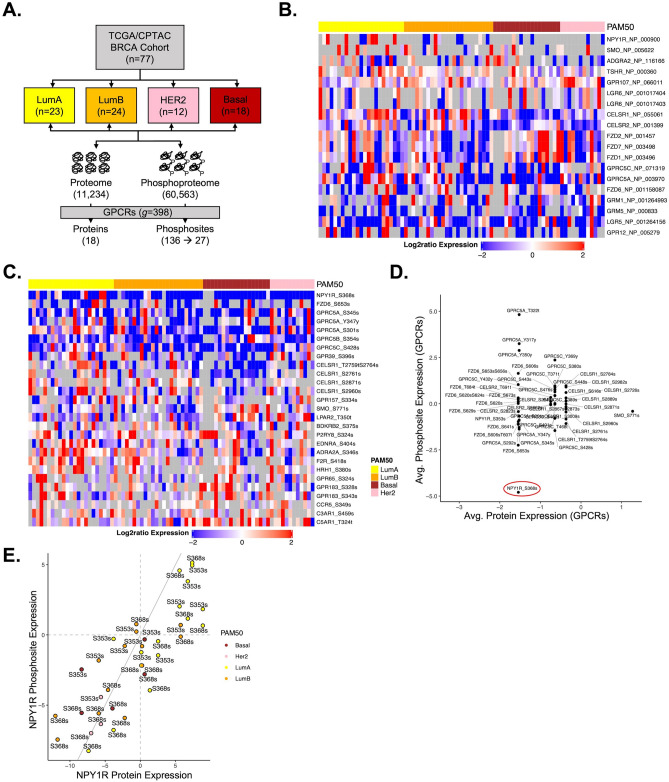

NPY1R is highly expressed and hyper-phosphorylated in LumA BC patients

To study GPCRs’ expression in BC, we used NCI-CPTAC’s proteomics and phosphoproteomics data29 which was previously characterized by TCGA with publicly available corresponding genomic data36. NCI-CPTAC breast cohort consisted of QC metrics qualified 77 patients, 23 LumA, 24 LumB, 12 HER2 (ERBB2)-enriched and 18 Basal-like tumors (Fig. 1A). In 77 samples, an isobaric peptide labeling approach (iTRAQ) identified a total 11,234 proteins and 60,563 phosphosites. Among them, we observed 18 GPCRs and 136 phosphosites overlapped with 398 GPCRs obtained from IUPHAR (The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology, IUPHAR v1.0). We selected 18 proteins and 27 sites with less than 50% missing value for subsequent analyses in this study. The following 18 GPCRs were quantified: NPY1R, SMO, ADGRA2, TSHR, GPR107, LGR5, LGR6, CELSR1, CELSR2, FZD1, FZD2, FZD6, FZD7, GPRC5A, GPRC5C, GRM1, GRM5, and GPR12 (Fig. 1B). The 21 GPCRs corresponding to 27 phosphosites were: NPY1R, FZD6, GPRC5A, GPRC5B, GPRC5C, GPR39, GPR65, GPR157, GPR183, CELSR1, SMO, LPAR2, BDKRB2, P2RY8, EDNRA, ADRA2A, F2R, HRH1, CCR5, C3AR1, and C5AR1 (Fig. 1C). Among 21 phosphoproteins, NPY1R (90%; n = 64/71) was largely hypo-phosphorylated followed by GPRC5A (84%; n = 60/71), GPRC5B (77%; n = 60/77), and GPRC5C (67%; n = 48/71) comparing across the sample cohort29. Average NPY1R protein and phosphosite expression showed greater hypophosphorylation at S368s in overall BC samples (Fig. 1D) but was hyperphosphorylated in LumA subtype samples (Fig. 1E). NPY1R expression was higher in BC compared to other 16 cancers across the TCGA cancer cohort obtained from HPA (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

GPCR proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis identified NPY1R as a potential GPCR target in luminal BC. (A) NCI-CPTAC breast cohort of 77 patients consisting of 23 LumA, 24 LumB, 12 HER2 and 18 basal-like tumors. The mass spectrometry based iTRAQ method identified a total 11,234 proteins and 60,563 phosphosites in 77 samples of which 18 proteins and 136 sites (27 sites with less than 50% missing value) overlapped with GPCRs. (B) The 18 proteins that were quantified: NPY1R, SMO, ADGRA2, TSHR, GPR107, LGR5, LGR6, CELSR1, CELSR2, FZD1, FZD2, FZD6, FZD7, GPRC5A, GPRC5C, GRM1, GRM5, and GPR12. (C) The 27 phosphosites corresponding to 21 proteins were NPY1R, FZD6, GPRC5A, GPRC5B, GPRC5C, GPR39, GPR65, GPR157, GPR183, CELSR1, SMO, LPAR2, BDKRB2, P2RY8, EDNRA, ADRA2A, F2R, HRH1, CCR5, C3AR1, and C5AR1. (D) Average NPY1R protein and phosphosite expression showed hypophosphorylation at S368s in overall samples but (E) hyperphosphorylation in lumA subtype. The expression values ranging from -2 to 2 (blue to red) indicate aggregated iTRAQ log-ratios for each sample, which are normalized by subtracting the mean of all values. Each row represents an individual GPCR and each column is a patient sample.

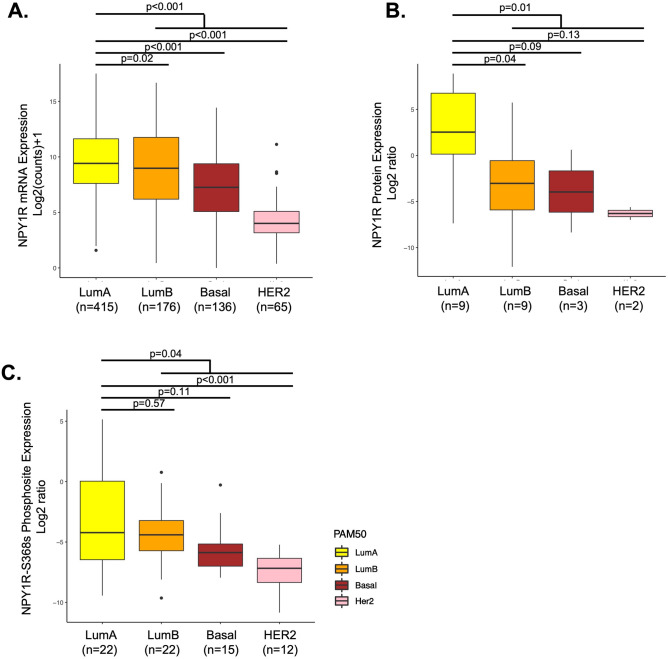

NPY1R gene and protein expression and phosphorylation status is subtype-specific in BC Patients

To explore the subtype-specific enrichment in BC, we compared the RNA, protein, and phosphosite expression of NPY1R across 4 BC subtypes (LumA, LumB, HER2, Basal). In TCGA-BRCA dataset (n = 817) with known PAM50 information31, we observed differential relative abundance of NPY1R gene transcripts in each of the BC subtypes. The trend was found to be decreasing in the order of LumA, LumB, Basal, and HER2 subtype. Both LumA and B showed a relatively high abundance of NPY1R gene transcripts (p < 0.001, Tukey test; Fig. 2A). In METABRIC dataset (n = 1758), NPY1R gene expression was significantly higher in LumA (n = 679) and LumB (N = 461) BC patients (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, in the CCLE dataset of BC cell lines, NPY1R gene expression was higher in LumA compared to other subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Protein expression data from matched patients revealed significantly higher levels of NPY1R (p = 0.01) only in LumA compared to all other subtypes combined, implying a specific up-regulation mechanism for the overexpression of NPY1R that is limited to LumA subtype tumors (Fig. 2B). NPY1R phosphorylation at S368 was higher in LumA subtype compared to combination of other subtypes (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2C) and the trend was found similar to that seen on RNA level. There was no significant difference in NPY1R protein and phospho-protein between LumA and other individual BC subtypes, likely due to smaller sample size.

Figure 2.

NPY1R expression at mRNA, protein and phosphosite level across BC subtype. (A) NPY1R RNA expression in TCGA breast cohort (n = 792), (B) protein expression in NCI-CPTAC samples (n = 23), and (C) NPY1R-S368s phosphosite expression in corresponding NCI-CPTAC dataset (n = 71). PAM50 subtypes were shown as LumA (yellow), LumB (orange), HER2 (pink) and Basal (brown). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey Test. *indicates p < 0.05.

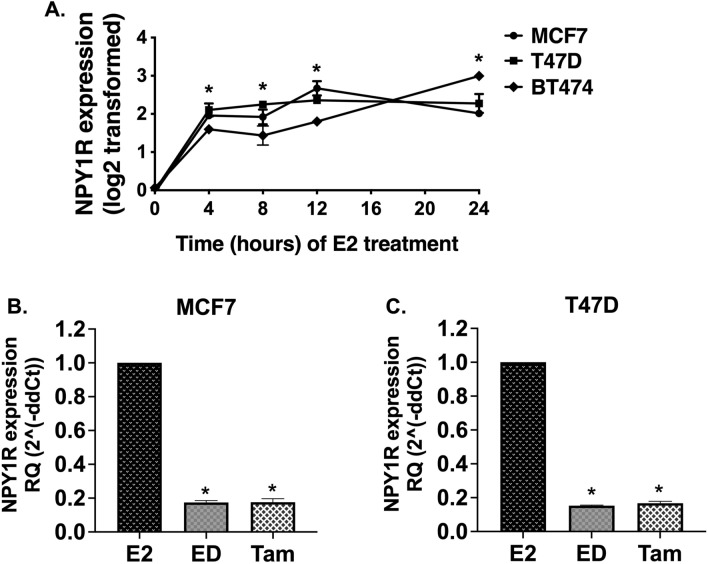

NPY1R is an estrogen-responsive gene

Next, we evaluated NPY1R expression using our available datasets from BC cell line models in response to estrogen and endocrine therapy35–37. NPY1R gene expression was significantly upregulated in all 3 BC cells (MCF7, T47D, and BT474) in response to E2 treatment in a time-dependent manner (0–24 h) (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Dunnett test) (Fig. 3A). Conversely, NPY1R gene expression was reduced after estrogen deprivation (ED) or with ED plus Tam in MCF7 and T47D cell models in RNA-seq analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4) as well as by qPCR (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Dunnett test) (Fig. 3B,C).

Figure 3:

17β-Estradiol (E2) treatment induces NPY1R gene expression in a time-dependent manner and endocrine therapy downregulates NPY1R gene expression in ER+ BC cells. (A) Data presented is derived from microarray-based gene expression profiles from three ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines (MCF7, T47D and BT474) stimulated by (E2) in vitro over a time course 0–24 h. RNA was isolated, and the gene expression profiles were determined using Affymetrix Genechip Arrays. Arrays were normalized and compared using DNA-Chip Analyzer software (dChip), (http://www.dchip.org/) (GEO: GSE3834)35. Gene expression values were log-transformed. NPY1R probe: 205440_s_at. Each data point represents the mean of duplicates (BT474 at 12 h is an individual value). Error bars show the SD (automatically calculated by GraphPad prism). (B) MCF7 and (C) T47D cells grown in charcoal-stripped media were treated with E2, estrogen deprivation (ED), or ED + tamoxifen (Tam). Total RNA was extracted for qPCR analysis and the fold change data were plotted as RQ (2(− ddct)). *indicates statistically significant difference compared to 0 h time point or E2; *indicates p < 0.05 by One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s test (n = 3).

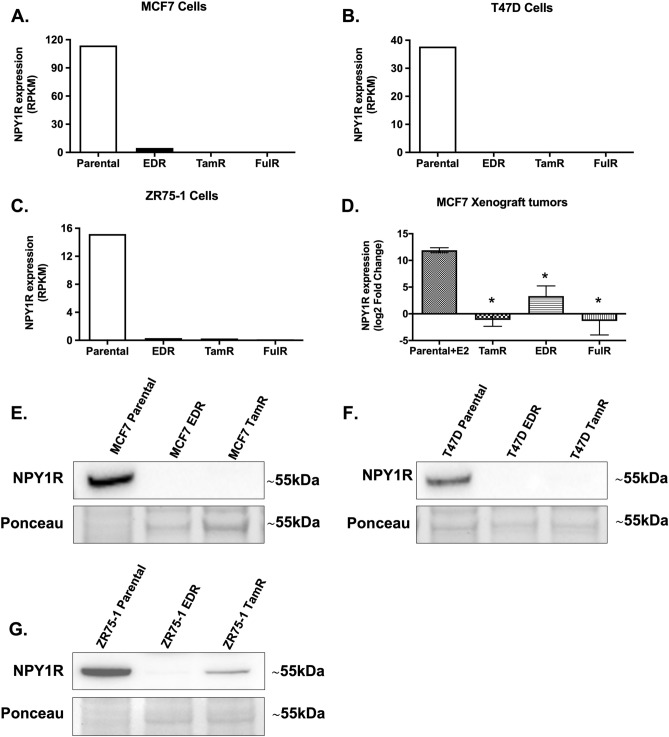

NPY1R expression is downregulated in endocrine-resistant BC

We also evaluated NPY1R expression in our available datasets from in vitro and in vivo BC models of endocrine resistance36–38. NPY1R gene expression was significantly reduced in EDR, TamR, and FulR derivatives of MCF7 (Fig. 4A), T47D (Fig. 4B), and ZR75-1 (Fig. 4C) ER+ BC cell line models compared to the parental cells (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Tukey test). Similarly, NPY1R gene expression was downregulated in TamR, EDR, and FulR MCF7 xenograft tumors compared to parental MCF7 xenografts grown with continued E2 supplementation (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s test) (Fig. 4D). Next, we compared the NPY1R protein expression on plasma membrane in MCF7, T47D, and ZR75-1 parental cells to their EDR and TamR derivatives. We found that NPY1R protein expression was diminished in EDR and TamR derivatives compared to their parental cells of MCF7 (Fig. 4E), T47D (Fig. 4F) and ZR75-1 (Fig. 4G) cell line models. The band at ~ 55 kDa was considered to be NPY1R, which was the prominent band in MCF7, T47D, and ZR75-1 parental cells, as reported before44,45. The full-length blots and the densitometric quantitation of the relative intensity of NPY1R to parental cells (from three independent experiments) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Figure 4.

NPY1R gene and protein expression is impaired in endocrine-resistant derivatives of ER+ BC cells in vitro and downregulated in tamoxifen-resistant xenograft tumors in vivo. RNA-Seq data of parental and their estrogen deprivation-resistant (EDR), tamoxifen-resistant (TamR), and fulvestrant-resistant (FulR) derivatives of (A) MCF7, (B) T47D, and (C) ZR75-1 cells were interrogated38. Data were plotted as Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (RPKM). (D) U133plus2 Affymetrix Chip array data from MCF-7 tumors derivatives of EDR, TamR, and FulR, alongside parental tumors in presence of continued estrogen supplementation (E2) was evaluated and plotted as RNA Express-calculated signal intensity (log2 transformed fold change)36,37. *indicates p < 0.05 by One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s test (n = 3–4). The protein expression of NPY1R was compared in MCF7, T47D and ZR75-1 parental cells to their EDR and TamR derivatives. Representative immunoblotting images showing the protein expression of NPY1R in (E) MCF7, (F) T47D and (G) ZR75-1 parental cells and their EDR and TamR derivatives. Ponceau staining was used to assess equal protein loading for visual assessment. The densitometric quantitation of the relative intensity of NPY1R to parental cells (from three independent experiments) is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

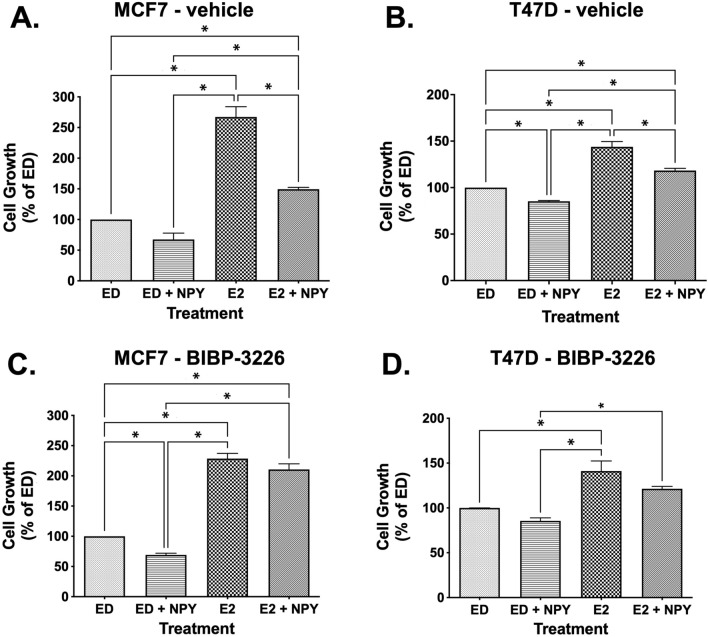

Inhibition of E2-stimulated cell growth by NPY is mediated via NPY1R

NPY significantly inhibited E2-stimulated cell growth in MCF7 and T47D cells (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Tukey test) (Fig. 5A and 5B). The inhibitory effect of NPY on E2-stimulated cell growth was reversed by treatment with BIBP-3226, a selective non-peptide antagonist of NPY1R46–50, in MCF7 and T47D cells (Fig. 5C and 5D). Notably, BIBP-3226 had no significant effects on non-E2-stimulated cell growth in MCF7 and T47D cells (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

NPY-mediated inhibition of estradiol-stimulated cell growth is reversed by NPY1R antagonist BIBP-3226 in ER+ BC cells. MCF7 and T47D cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) (A, B) or 1 µM BIBP-3226 (C, D) and then plated in 96-well plates. After overnight attachments, the cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% ethanol), 100 nM neuropeptide Y, 1 nM estradiol, or 100 nM NPY + 1 nM estradiol. The cell proliferation was determined using MTT assay after 72 h. *indicates p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Tukey test.

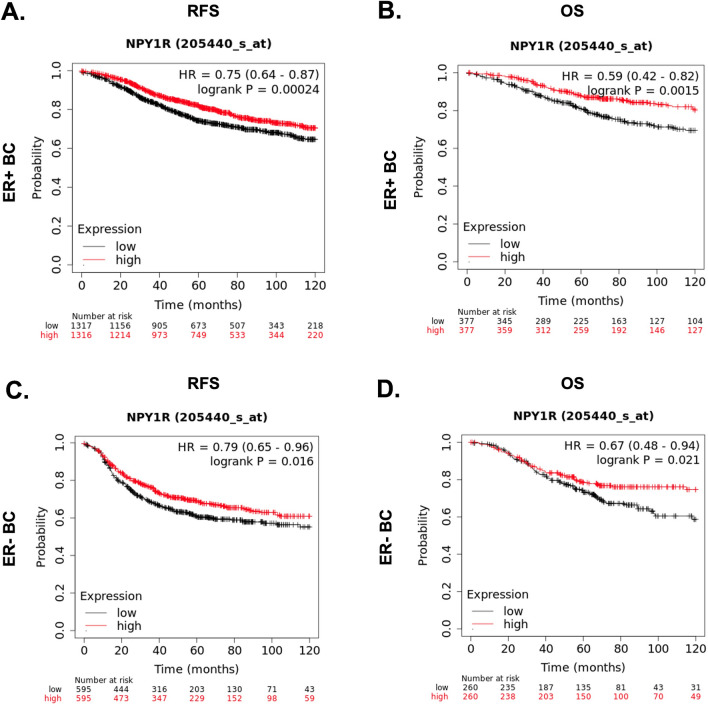

NPY1R is a prognostic marker in ER+ and LumA BC

Higher NPY1R gene expression in ER+ BC patients regardless of HER2 status predicted longer RFS [HR = 0.8 (range: 0.68–0.94, logrank P = 0.0072)] (Fig. 6A) and OS [HR = 0.62 (range: 0.43–0.89, logrank P = 0.009)] (Fig. 6B). In ER− BC patients, higher NPY1R gene expression was not predictive of RFS [(HR = 0.8 (range: 0.64–1.01, logrank P = 0.055) (Fig. 6C) but was associated with better OS [(HR = 0.61 (range: 0.38–0.97, logrank P = 0.034)] (Fig. 6D). In METABRIC dataset, high NPY1R expression predicted significantly longer BCSS in LumA (n = 678, logrank P = 0.0147) tumors but not in Lum B tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

NPY1R expression predicts better relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in ER+ BC patients. The impact of NPY1R expression on RFS (A, C) and OS (B, D) in ER+ (A, B) and ER− (C, D) BC patients was plotted using KMplotter, which assessed the effects of 22,277 genes on survival in 2422 BC patients. Red line: higher than median NPY1R expression; black line: lower than median NPY1R expression. HR hazard ratio. Log-rank P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we have evaluated the proteome and phosphoproteome data of 398 non-sensory GPCRs using the landmark TCGA BC proteogenomics dataset. NPY1R was the topmost hypo-phosphorylated (at S368s) GPCR in more than 90% of the samples tested. Among tumor samples, the LumA subtype had significantly higher NPY1R expression than all other BC subtypes. Interestingly, the trend of NPY1R gene and protein expression as well as phosphorylation at S368s were decreasing in the order of LumA, LumB, Basal, and HER2 subtypes. The up- and down-regulation of NPY1R gene expression in ER+ BC cells upon treatment with E2 and Tam or ED, respectively, confirmed NPY1R as an estrogen-responsive gene. In endocrine-resistant (TamR, EDR, and FulR) derivatives of ER+ BC cell line models, NPY1R expression remained significantly lower compared to the parental cells both in vitro and in vivo. In the publicly available dataset, higher NPY1R expression predicted better OS and RFS in ER+ and LumA BC patients. NPY treatment significantly reduced E2-stimulated cell growth in ER+ BC cells, which was reversed by NPY1R antagonist, BIBP-3226, suggesting that the effects of NPY are mediated by NPY1R.

NPY, which is the most abundant neuropeptide in the mammalian brain mediates numerous physiological functions, including: orexigenic (increasing appetite) effect, neuroendocrine regulation, reducing anxiety, stress and pain perception, affecting the circadian rhythm and memory, lowering blood pressure, and controlling epileptic seizures51–61. The circulatory levels of NPY are reported to be elevated in hypertensive subjects, obesity, preeclampsia, and in some malignancies such as neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma due to high neuropeptide synthesis within tumor tissues62–66. NPY exerts most of its actions through at least five different GPCRs, NPYY1-567. Among them, NPY1R is the only receptor with a high incidence in human breast carcinomas, however it is unclear whether the NPY is locally synthesized in breast tissue or endogenously expressed by breast cancer cells. NPY1R has been reported to be expressed in 85% of the primary human BC compared to normal breast tissue which only expresses the NPY2R receptor subtype68. Because of the high NPY1R expression in BC, it has been explored as a promising probe in cancer diagnosis68. Radiotracers for NPY1R-targeted BC imaging have been synthesized and used in several studies68–71. However, our studies find that NPY1R expression is high only in LumA BC but not in other subtypes. Furthermore, its expression is downregulated in the endocrine-resistance setting. Therefore, our results suggest that NPY1R may not be a good probe for cancer diagnostics, but rather to predict endocrine sensitivity and treatment response.

The significance of hyperphosphorylated status of NPY1R in LumA BC and its hypophosphorylation in other BC subtypes is not clear at this point but needs further evaluation. For class A GPCRs like NPY1R, agonist binding exerts the downstream signaling via the receptor coupling to G proteins72. This transient signaling is followed by desensitization of the GPCR by phosphorylation by GPCR kinases (commonly known as GRKs) followed by endocytosis73. In most cases, GPCRs are dephosphorylated and recycled back to the plasma membrane ready to bind to available agonist74. In this sense, hyperphosphorylation of NPY1R in LumA may indicate the presence of functional receptor. Because NPY1R mediates action of NPY on reducing E2-stimulated growth in ER+ BC cells, presence of functional receptor may indicate favorable outcome in patients. However, whether phosphorylation status of NPY1R predicts endocrine sensitivity needs to be assessed in future studies.

A functional interplay between estrogen and NPY1R has been shown in the ER+ BC cell line, where estrogen has been found to increase NPY1R expression, which in turn negatively regulated E2-stimulated cell proliferation75. Our results showing the inhibitory effects of NPY on E2-stimuated cell growth in ER+ BC cells is also consistent with a previous report75. These results also explain why higher expression of NPY1R is a favorable predictor of outcomes in ER+ BC. A higher expression of NPY1R should allow circulating NPY to inhibit E2-stimulated cell growth in tumors. However, it is not known how these effects can be leveraged to develop new therapeutics to improve efficacy of endocrine therapy in patients.

In ER+ BC, endocrine therapy is the most effective treatment option, but its effectiveness is limited by high rates of de novo resistance and resistance acquired during treatment76. Our studies highlighted the previously unknown role of NPY1R as a biomarker in the endocrine resistance setting where the receptor is downregulated. NPY1R gene expression was also found to be downregulated in patients resistant to aromatase inhibitors compared to responders77. These clinical data confirm our findings in preclinical models of endocrine resistance. More recently, cyclin D/cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) have shown to be effective in overcoming endocrine resistance and are used in combination with endocrine therapy to increase the survival advantage of metastatic ER+ BC patients78. Despite having better clinical outcomes, acquired resistance to CDK4/6i presents a major clinical challenge78–80. The role of NPY1R as a biomarker of resistance to the combination of endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors is unknown and should be investigated in the future.

Conclusions

In summary, we have found NPY1R to be highly expressed and hyperphosphorylated GPCR in LumA breast tumors of patients. Our results demonstrate NPY1R expression as a predictor of endocrine sensitivity ER+ BC and long-term outcomes in patients. Future studies targeting NPY1R will further elucidate the role of NPY1R as a novel drug target in ER+ BC.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

R.B., H.T., and N.M.A. performed the experiments and/or drafted the manuscript. L.B., M.L.C., and S.N. performed and/or assisted with the experiments. S.V., C.D.A., and B.Z. participated in or supervised bioinformatics analysis and data interpretation. C.D.A., X.F., and R.S. contributed to manuscript editing. M.V.T. conceived, designed and coordinated all the experiments and supervised the analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in parts by Department of Defense BCRP Grants W81XWH-14-1-0340 and W81XWH-14-1-0341; Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF-18-145 and 19-145 Grants); and NIH grants CA125123, P50 CA058183 and CA186784-01. None of the funding agencies had any role in the design, analysis, or reporting of the analyses.

Competing interests

Rachel Schiff receives/has received research funding from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Puma, Biotechnology Inc., and Gilead Sciences (to the institution); she has been a past ad hoc advisory committee member for Eli Lilly; she is a consulting/advisory committee member for Macrogenics; and she has other financial interests: UpToDate Royalties. Carmine De Angelis has served as consultant/advisory board member for Eli Lilly, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer. Carmine De Angelis has received research support from Novartis. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Raksha Bhat and Hariprasad Thangavel.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-05949-7.

References

- 1.Clark GM, Osborne CK, McGuire WL. Correlations between estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and patient characteristics in human breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1984;2:1102–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA. 2019;321:288–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis PA, et al. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:436–446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: Patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: A most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2003;2:205–213. doi: 10.1038/nrd1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanker AB, Sudhan DR, Arteaga CL. Overcoming endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:496–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke R, Tyson JJ, Dixon JM. Endocrine resistance in breast cancer: An overview and update. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;418(Pt 3):220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuliano M, Schifp R, Osborne CK, Trivedi MV. Biological mechanisms and clinical implications of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Breast. 2011;20(Suppl 3):S42–49. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ring A, Dowsett M. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2004;11:643–658. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rask-Andersen M, Almen MS, Schioth HB. Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rask-Andersen M, Masuram S, Schioth HB. The druggable genome: Evaluation of drug targets in clinical trials suggests major shifts in molecular class and indication. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014;54:9–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schioth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: New agents, targets and indications. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagerstrom MC, Schioth HB. Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:339–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young D, Waitches G, Birchmeier C, Fasano O, Wigler M. Isolation and characterization of a new cellular oncogene encoding a protein with multiple potential transmembrane domains. Cell. 1986;45:711–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pebay A, et al. Essential roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate and platelet-derived growth factor in the maintenance of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1541–1548. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi NR, Hawes SM, Crook JM, Pebay A. G-protein coupled receptors in stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Stem. Cell Rev. 2010;6:351–366. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura K, Salomonis N, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S, Conklin BR. G(i)-coupled GPCR signaling controls the formation and organization of human pluripotent colonies. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA. GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265–266:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu B, et al. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science. 2010;330:1066–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu V, et al. Illuminating the Onco-GPCRome: Novel G protein-coupled receptor-driven oncocrine networks and targets for cancer immunotherapy. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:11062–11086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.005601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nag JK, et al. Cancer driver G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) induced beta-catenin nuclear localization: The transcriptional junction. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018;37:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9711-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darnell JE., Jr Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:740–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobin AB. G-protein-coupled receptor phosphorylation: Where, when and by whom. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S167–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woerner BM, et al. Suppression of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 expression is a feature of classical GBM that is required for maximal growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012;10:156–166. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latorraca NR, et al. How GPCR phosphorylation patterns orchestrate arrestin-mediated signaling. Cell. 2020;183:1813–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liggett SB. Phosphorylation barcoding as a mechanism of directing GPCR signaling. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mertins P, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;534:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature18003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broad Institute TCGA Genome Data Analysis Center Firehose version stddata__2016_01_28. Broad Inst. MIT Harvard. 2016 doi: 10.7908/C11G0KM9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciriello G, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell. 2015;163:506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhlen M, et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. 2017;357:6327. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira B, et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barretina J, et al. The cancer cell line encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creighton CJ, et al. Genes regulated by estrogen in breast tumor cells in vitro are similarly regulated in vivo in tumor xenografts and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creighton CJ, et al. Development of resistance to targeted therapies transforms the clinically associated molecular profile subtype of breast tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7493–7501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massarweh S, et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res. 2008;68:826–833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Angelis C, et al. Activation of the IFN signaling pathway is associated with resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and immune checkpoint activation in ER-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison G, et al. Therapeutic potential of the dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor AZD8931 in circumventing endocrine resistance. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;144:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdulkareem NM, et al. A novel role of ADGRF1 (GPR110) in promoting cellular quiescence and chemoresistance in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. FASEB J. 2021;35:e21719. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100070R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhat RR, et al. GPCRs profiling and identification of GPR110 as a potential new target in HER2+ breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018;170:279–292. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4751-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gyorffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing v. 3.4.0 https://www.R-project.org (2020).

- 44.Kang X, et al. Neuropeptide y acts directly on cartilage homeostasis and exacerbates progression of osteoarthritis through NPY2R. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020;35:1375–1384. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundy FT, El Karim IA, Linden GJ. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and NPY Y1 receptor in periodontal health and disease. Arch. Oral Biol. 2009;54:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Lundberg JM, Thoren P. The effect of a neuropeptide Y antagonist, BIBP 3226, on short-term arterial pressure control in conscious unrestrained rats with congestive heart failure. Life Sci. 1999;65:1839–1844. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00435-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah SH, et al. Neuropeptide Y gene polymorphisms confer risk of early-onset atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masliuko PM, et al. NPY1 receptors participate in the regulation of myocardial contractility in rats. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017;162:418–420. doi: 10.1007/s10517-017-3629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doods HN, et al. BIBP 3226, the first selective neuropeptide Y1 receptor antagonist: A review of its pharmacological properties. Regul. Pept. 1996;65:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(96)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudolf K, et al. The first highly potent and selective non-peptide neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist: BIBP3226. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;271:R11–13. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tatemoto, K. Neuropeptide y and related peptides. in Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 2–15 (Springer, 2012).

- 52.Everitt, B. J. H. The coexistence of neuropeptide Y with other peptides and amines in the central nervous system. Neuropeptide Y, 61–72 (Raven, 1989).

- 53.Kuo LE, et al. Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nat. Med. 2007;13:803–811. doi: 10.1038/nm1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krysiak R, Obuchowicz E, Herman ZS. The role of neuropeptide Y in anxiety. Psychiatr. Pol. 2001;35:731–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heilig M, Thorsell A. Brain neuropeptide Y (NPY) in stress and alcohol dependence. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;13:85–94. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2002.13.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diaz-delCastillo M, Woldbye DPD, Heegaard AM. Neuropeptide Y and its involvement in chronic pain. Neuroscience. 2018;387:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan CMJ, et al. The role of neuropeptide Y in cardiovascular health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:1281. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gotzsche CR, Woldbye DP. The role of NPY in learning and memory. Neuropeptides. 2016;55:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michel MC, Rascher W. Neuropeptide Y: A possible role in hypertension? J. Hypertens. 1995;13:385–395. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colmers WF, El Bahh B. Neuropeptide Y and epilepsy. Epilepsy. Curr. 2003;3:53–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1535-7597.2003.03208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crowley, W. R. in xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference (eds S. J. Enna & David B. Bylund) 1–4 (Elsevier, 2007).

- 62.Howe PR, Rogers PF, Morris MJ, Chalmers JP, Smith RM. Plasma catecholamines and neuropeptide-Y as indices of sympathetic nerve activity in normotensive and stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1986;8:1113–1121. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang HN, et al. Higher serum neuropeptide Y levels are associated with metabolically unhealthy obesity in obese chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020:7903140. doi: 10.1155/2020/7903140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paiva SP, et al. Elevated levels of neuropeptide Y in preeclampsia: A pilot study implicating a role for stress in pathogenesis of the disease. Neuropeptides. 2016;55:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dotsch J, Christiansen H, Hanze J, Lampert F, Rascher W. Plasma neuropeptide Y of children with neuroblastoma in relation to stage, age and prognosis, and tissue neuropeptide Y. Regul. Pept. 1998;75–76:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tilan JU, et al. Systemic levels of neuropeptide Y and dipeptidyl peptidase activity in patients with Ewing sarcoma-associations with tumor phenotype and survival. Cancer. 2015;121:697–707. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balasubramaniam AA. Neuropeptide Y family of hormones: Receptor subtypes and antagonists. Peptides. 1997;18:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(96)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reubi JC, Gugger M, Waser B, Schaer JC. Y(1)-mediated effect of neuropeptide Y in cancer: Breast carcinomas as targets. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4636–4641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgat C, et al. Targeting neuropeptide receptors for cancer imaging and therapy: Perspectives with bombesin, neurotensin, and neuropeptide-Y receptors. J. Nucl. Med. 2014;55:1650–1657. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.142000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khan IU, et al. Breast-cancer diagnosis by neuropeptide Y analogues: From synthesis to clinical application. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:1155–1158. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofmann S, Maschauer S, Kuwert T, Beck-Sickinger AG, Prante O. Synthesis and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of an (18)F-labeled neuropeptide Y analogue for imaging of breast cancer by PET. Mol. Pharm. 2015;12:1121–1130. doi: 10.1021/mp500601z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013;494:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gurevich EV, Tesmer JJ, Mushegian A, Gurevich VV. G protein-coupled receptor kinases: More than just kinases and not only for GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;133:40–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marchese A, Paing MM, Temple BR, Trejo J. G protein-coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008;48:601–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amlal H, Faroqui S, Balasubramaniam A, Sheriff S. Estrogen up-regulates neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor expression in a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3706–3714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Osborne CK, Schiff R. Mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011;62:233–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070909-182917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller CA, et al. Aromatase inhibition remodels the clonal architecture of estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12498. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pernas S, Tolaney SM, Winer EP, Goel S. CDK4/6 inhibition in breast cancer: Current practice and future directions. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918786451. doi: 10.1177/1758835918786451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herrera-Abreu MT, et al. Early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2301–2313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Portman N, et al. Overcoming CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in ER positive breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2018 doi: 10.1530/ERC-18-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.