Abstract

The major antigenic protein 2 (MAP2) of Ehrlichia canis was cloned and expressed. The recombinant protein was characterized and tested in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format for potential application in the serodiagnosis of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. The recombinant protein, which contained a C-terminal polyhistidine tag, had a molecular mass of approximately 26 kDa. The antigen was clearly identified by Western immunoblotting using antihistidine antibody and immune serum from an experimentally infected dog. The recombinant MAP2 (rMAP2) was tested in an ELISA format using 141 serum samples from E. canis immunofluorescent antibody (IFA)-positive and IFA-negative dogs. Fifty-five of the serum samples were from dogs experimentally or naturally infected with E. canis and were previously demonstrated to contain antibodies reactive with E. canis by indirect immunofluorescence assays. The remaining 86 samples, 33 of which were from dogs infected with microorganisms other than E. canis, were seronegative. All of the samples from experimentally infected animals and 36 of the 37 samples from naturally infected animals were found to contain antibodies against rMAP2 of E. canis in the ELISA. Only 3 of 53 IFA-negative samples tested positive on the rMAP2 ELISA. There was 100% agreement among IFA-positive samples from experimentally infected animals, 97.3% agreement among IFA-positive samples from naturally infected animals, and 94.3% agreement among IFA-negative samples, resulting in a 97.2% overall agreement between the two assays. These data suggest that rMAP2 of E. canis could be used as a recombinant test antigen for the serodiagnosis of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis.

Ehrlichia canis is an obligate intracellular, gram-negative bacterium and the causative agent of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne rickettsial disease which is transmitted by the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (19). Interest in E. canis infection has heightened over the last decade, fueled by the recent discovery of a very closely related organism, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the causative agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (15). More recently, it has been shown that dogs are susceptible to experimental infection with E. chaffeensis (11), and natural infections with E. chaffeensis have also been identified in healthy and clinically ill dogs by PCR analysis (5, 11, 25, 29). This suggests that dogs may serve as an important reservoir for this human pathogen.

Sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA genes of E. canis and E. chaffeensis revealed that E. chaffeensis is more closely related to E. canis than to any other species (3). These organisms, along with Cowdria ruminantium, a rickettsial disease agent of cattle, are phylogenetically related and are all placed within the E. canis genogroup (13, 36, 48). There is considerable antigenic cross-reactivity between the Ehrlichia spp. and other closely related organisms, such as C. ruminantium (8, 9, 23, 30, 32). Serological assays able to distinguish between infections with E. canis and those with E. chaffeensis are presently not available. Breitschwerdt et al. showed by PCR analysis that dogs seropositive for E. canis could be infected with E. chaffeensis or any one of four Ehrlichia spp. (5). In addition, when assayed for both organisms by fluorescent-antibody testing, many dogs were serologically positive for E. canis and E. chaffeensis (11, 29).

Early diagnosis of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis is important because, even though E. canis can cause fatal disease, treatment with tetracycline antibiotics or tetracycline derivatives usually results in complete recovery, particularly when infections are identified during the acute stage of the disease (22). Failure to identify animals during the acute phase of the disease and progression to chronic ehrlichiosis could result in a less favorable response to therapy (16). The immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test is the most widely used serologic assay for the diagnosis of infection with E. canis (33). In dogs with evidence of clinical disease, a reciprocal titer of 40 or greater generally indicates infection (20, 21). This assay does, however, have major disadvantages—test results are sometimes subjective, relying on the absence of background fluorescence and the visual skills of the reader, and recent evidence indicates that a significant number of false-positive results occur with IFA, possibly related to the subjective nature of interpretation and/or cross-reactivity (35).

We recently reported the cloning and expression of the major antigenic protein 2 (MAP2) antigen from E. chaffeensis, which could be used in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format to detect antibodies to E. chaffeensis in sera from infected humans (1). This was the first report of an E. chaffeensis recombinant antigen for use in an ELISA format. The E. chaffeensis MAP2 gene is homologous to the map2 gene of C. ruminantium and the msp5 gene of Anaplasma marginale. Both map2 and msp5 genes have been shown to be conserved between various isolates of their respective organisms (4, 37). The recombinant products of these genes are presently being used in ELISAs to diagnose infections with these agents (24, 26). In this study, we report the cloning and expression of map2 from E. canis and examine the potential value of the recombinant MAP2 protein (rMAP2) for the rapid serodiagnosis of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of E. canis organisms and DNA.

E. canis (Oklahoma isolate) was kindly provided by Jacqueline E. Dawson and James G. Olsen, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga. Organisms were grown in the canine macrophage cell line DH82 in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 26 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 2 mM l-glutamine at 34°C. Cells were harvested when 90 to 100% of them were infected, and ehrlichiae were purified as described previously (10). Genomic DNA of E. canis was isolated by treatment of purified organisms with 5 mg of lysozyme per ml, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml, and 2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation (26).

Amplification of the map2 gene of E. canis

Primers, which corresponded to the sequences encoding the predicted mature protein of the map2 gene, were synthesized by Genosys Biotechnologies, Inc., The Woodlands, Tex. The forward primer, ARA5 (5′ GCAATATTTTTAGGGTATTCCTATATTACA 3′), and the reverse primer, ARA6 (5′ CAGATACTGCTTAACTAAAGATAGTAACTT 3′), were designed for in-frame insertion of amplicons into the pTrcHis2-TOPO vector (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.). The beginning of the predicted mature protein corresponds to nucleotide number 46 of the open reading frame. The nucleotide sequence of the map2 gene of E. canis has been reported previously (4) and was assigned the GenBank accession number AF117730. Amplification was performed with Taq DNA polymerase in order to produce amplicons with the necessary 3′ A overhangs needed for ligation into the TOPO vector. Briefly, genomic DNA (10 ng) was amplified with each of the primers ARA5 and ARA6 at 0.5 μM and with 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase in 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8)–50 mM KCl–1.5 mM MgCl2. PCR assays were performed at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 10 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 43°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 7 min. This was followed by 25 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 49°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 7 min. A final extension step at 72°C was performed for 7 min. Amplicons were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel in 1× TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, and 2 mM disodium EDTA).

Cloning and sequencing of E. canis map2.

Amplicons were inserted into the pTrcHis2-TOPO vector (Invitrogen Corporation) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Recombinant plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli (One Shot cells; Invitrogen Corporation), and transformants were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates in the presence of ampicillin (50 μg/ml). Colonies were selected and incubated in LB broth in the presence of ampicillin (50 μg/ml) overnight at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Plasmid DNA was extracted by a rapid miniprep method (39), reconstituted in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1.0 μg of DNase-free RNase per ml, and analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. Recombinant clones containing the map2 gene of E. canis were digested with restriction enzymes (NcoI and DraI) to ensure the correct orientation of the insert in the plasmid vector. Digested DNA was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. The DNA sequences of both strands of the 570-bp insert of pTrcHis2-TOPO 8a were determined by the DNA Sequencing Core Laboratory (ICBR, University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla.) with forward and reverse primers based on vector sequences in flanking regions.

E. canis rMAP2 production and purification.

Transformed cells containing the map2 gene homologs of E. canis were incubated with vigorous shaking at 37°C in LB broth containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. Protein production was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and cells were incubated with vigorous shaking at 37°C for an additional 5 h. Recombinant proteins were purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (ProBond resin; Invitrogen Corporation) and isolated under native, nondenaturing conditions with a pH elution buffer (pH 4.0) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, with the following exceptions. In order to inhibit nonspecific binding of E. coli proteins, 20 mM imidizole was added to the binding buffer and to the buffer used to equilibrate the chromatography columns. Fractions containing the rMAP2 homolog were identified by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and staining with Coomassie blue. rMAP2 contained a C-terminal polyhistidine tag for purification by affinity chromatography. The authenticity of the rMAP2 homolog of E. canis was evaluated by Western immunoblot analysis using a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antihistidine antibody (Invitrogen Corporation) and known E. canis-, IFA-positive canine serum from an experimentally infected animal.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The rMAP2 concentrations were determined by the Coomassie blue G dye-binding assay as described previously (31). Proteins were dissolved in 3× sample buffer containing 0.1 M Tris (pH 6.8), 5% (wt/vol) SDS, 50% glycerol, and 0.00125% bromophenol blue, either with or without 7.5% β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were heat denatured at 100°C for 3 min prior to electrophoresis on 10% (wt/vol) SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham International plc, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England) and fixed in 25 mM Tris–191.8 mM glycine–20% methanol as described previously (2).

Antibodies and antisera.

HRP-labeled antihistidine antibody [Anti-His(C-term)- HRP; Invitrogen Corporation] was used as a positive control for the rMAP2 homolog on immunoblots. One hundred forty-one serum samples from the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C., and the College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla., were evaluated for antibodies to the rMAP2 homolog of E. canis. Fifty-five of the serum samples were previously demonstrated to contain antibodies reactive with E. canis (Oklahoma strain at the University of Florida; Florida strain at North Carolina State University) by IFA testing. The remaining 86 samples were IFA negative. Eighteen of the IFA-positive samples were obtained from animals experimentally infected with E. canis during previous studies conducted at North Carolina State University (6). One of these animals had a reciprocal IFA titer of 160, two had reciprocal titers of 320, and two had reciprocal titers of 640. The remaining 13 samples had reciprocal titers of 1,280 or greater. Samples were collected from animals as soon as 16 days and as late as 24 months postinfection. Thirty-seven of the IFA-positive samples were from naturally infected animals that presented with clinical signs consistent with canine ehrlichioses. Two of these samples had a reciprocal IFA titer of 40, two had titers of 80, two had titers of 160, four had titers of 320, four had titers of 640, and the remaining 23 samples had titers of 1,280 or greater. Samples with IFA titers of 20 or less were considered negative. Fifty-three of the IFA-negative samples were from clinically healthy individuals during well-patient visits or from preinfection sera from experimentally infected animals. Thirty-three of the E. canis-IFA-negative samples were from dogs infected with various microorganisms, including Babesia canis, Ehrlichia platys, Ehrlichia risticii, Ehrlichia ewingii, Rickettsia rickettsii, Bartonella vinsonii, Haemobartonella canis, and Neospora caninum. Three of the E. platys samples also had titers of antibodies to B. canis in the IFA. These sera were used to evaluate the specificity of the rMAP2 antigen of E. canis.

Western immunoblot analysis.

Nitrocellulose membranes containing electrophoretically transferred proteins were blocked for 1 h with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.25% Tween 20 and washed with 1% (wt/vol) milk in 1× PBS with 0.25% Tween 20 as described previously (2). Membranes were probed with either HRP-labeled antihistidine antibodies at a dilution of 1/5,000 or E. canis IFA-positive immune sera at dilutions of 1/100, 1/300, 1/1,000, and 1/3,000. As a negative control, noninfected canine serum was used at a dilution of 1/100 or 1/300. Membranes were then washed with 1% (wt/vol) milk in 1× PBS as described previously (2) and reacted with a secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-dog immunoglobulin G (whole molecule; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) at a dilution of 1/40,000. Membranes were processed for enhanced chemiluminescence with detection reagents containing luminol (SuperSignal Substrate; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as a substrate and were exposed to X-ray film (Hyperfilm-MP; Amersham International plc) to visualize the bound antibody.

Indirect ELISA.

Polystyrene microtiter plates (Maxi Sorp; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 100 μl of purified rMAP2 homolog of E. canis (4 μg/ml) per well in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6 (Sigma Chemical Co.), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were then washed four times with wash buffer containing 1× PBS and 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and blocked for 60 min at room temperature with 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1× PBS. Plates were washed four times as described above and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with test sera at 1:100, 1:300, 1:1,000, 1:3,000, and 1:10,000 dilutions in 1.0% (wt/vol) BSA in 1× PBS (100 μl). Wells were again washed (four times) and incubated at room temperature for 60 min in the presence of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-dog immunoglobulin G (whole molecule; Sigma Chemical Co.) at a dilution of 1:5,000 in 1% (wt/vol) BSA in 1× PBS. Wells were again washed (four times), and the substrate, p-nitrophenylphosphate (1 mg/ml), in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6 (Sigma Chemical Co.), was added at 100 μl per well and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured with a Tecan Rainbow plate reader (Tecan U.S. Inc., Durham, N.C.). Serum samples from five clinically healthy animals were used to establish the cutoff values for determining if a test sample was positive or negative. Negative controls were used each time an ELISA was performed. A test sample was considered positive if the absorbance reading was at least three standard deviations above the mean absorbance of the negative test sera at the comparable serum dilution.

RESULTS

Analysis of the predicted amino acid sequence of the rMAP2 homolog indicated that the recombinant protein differed from the previously reported predicted amino acid sequence of the native protein at three positions. Position 10 in the mature, native E. canis MAP2 contains the polar amino acid threonine, while the rMAP2 has a basic amino acid, arginine, at this position. A conserved amino acid substitution also occurred at position 103 of the reported sequence, where an aspartic acid was replaced with asparagine in the recombinant protein, and at position 187 the mature protein contains the basic amino acid lysine, while the rMAP2 has asparagine at this position. Both native and recombinant map2 sequences were derived from the Oklahoma strain of E. canis. We have not investigated whether these differences were the result of PCR amplification errors or whether these differences represent true polymorphism in regions of the gene.

Western immunoblot analysis was done to evaluate each of the five fractions obtained after elution of the rMAP2 protein from the affinity chromatography column with the pH elution buffer. HRP-labeled antihistidine antibody was used to identify the C-terminal histidine tag on the rMAP2 protein. A single protein with a molecular mass of approximately 26 kDa was identified in fractions 2 and 3 (data not shown). The fusion peptide increases the size of the recombinant protein seen on immunoblots. Based on the amino acid sequence, the calculated mass of the rMAP2 is approximately 21 kDa.

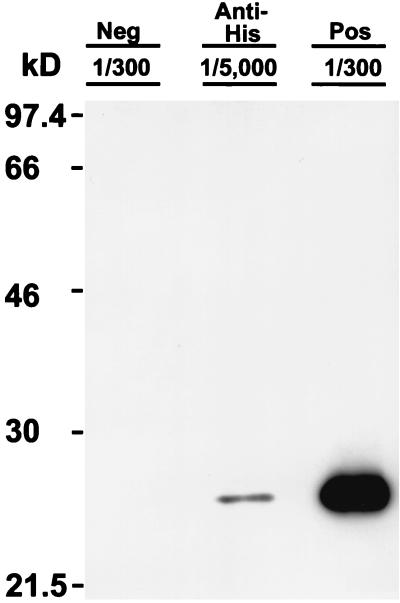

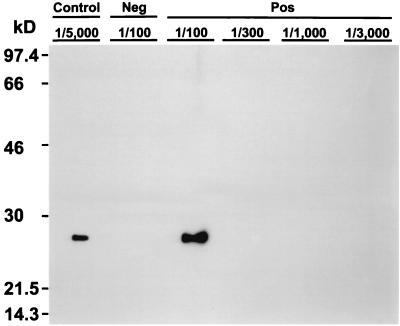

Western immunoblot analysis was also done to evaluate reactivity of the rMAP2 homolog with immune serum from a seropositive dog, experimentally infected with E. canis. In these experiments, purified recombinant proteins were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. Normal canine serum was used as a negative control on immunoblots, and HRP-labeled antihistidine antibody was used as a positive control for detection of the recombinant protein. The 26-kDa recombinant protein was clearly identified with the antihistidine antibody. A protein with an identical molecular mass was recognized by the immune serum from an experimentally infected dog (Fig. 1). Similarly, the rMAP2 antigen was used in Western immunoblot assays to determine the ability of this assay to detect antibodies in various dilutions of immune sera. The recombinant was recognized only when immune serum from a naturally infected dog was used at high concentrations (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot of rMAP2 homolog of E. canis reacted with normal canine serum from a noninfected animal (Neg), antihistidine antibodies (Anti-His-Ab), or E. canis-IFA-positive immune serum from an experimentally infected dog, Shep 35 (Pos). The fractions (1/300 and 1/5,000) indicate the dilutions of antibody or serum used. Molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are given on the left.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot of rMAP2 homolog of E. canis reacted with antihistidine antibodies (Control), normal canine serum from a noninfected animal (Neg), or E. canis-IFA-positive immune serum from a naturally infected dog, CN137787 (Pos). The fractions indicate the dilutions of antibody or serum used. Molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are given on the left.

ELISAs were performed on 141 serum samples which had been evaluated previously for antibodies against E. canis by IFA testing. Eighteen samples were from animals experimentally infected with E. canis during previous studies. Each sample was shown to contain antibodies to E. canis by IFA testing. Antibodies were also detected in all 18 samples in the rMAP2 ELISA (Table 1). Thirty-seven of the IFA-positive samples from naturally infected animals were also tested by rMAP2 ELISA (Table 2). Only 1 of 37 IFA-positive samples tested negative on the rMAP2 ELISA. In samples that were positive by both assays, the rMAP2 ELISA was usually able to detect antibodies at a similar or higher dilution of serum (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of rMAP2 ELISA results with 18 E. canis IFA-positive samples from experimentally infected dogs

| No. of samplesa | rMAP2 ELISA titerb | E. canis IFA titerc |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 300 | 160 |

| 1 | 300 | 320 |

| 2 | 300 | ≥2,560 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 640 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 1,280 |

| 1 | ≥3,000 | 320 |

| 1 | ≥3,000 | 640 |

| 1 | ≥3,000 | 1,280 |

| 9 | ≥3,000 | ≥2,560 |

Samples were collected from animals from 16 days to 24 months postinfection.

A sample was considered positive in the rMAP2 ELISA when the absorbance reading of the test serum at a specific dilution was at least three standard deviations above the mean absorbance reading of identical dilutions of standard negative control sera. All results presented here were considered positive.

A titer of ≥40 was considered positive in the IFA test.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of rMAP2 ELISA results with 37 E. canis IFA-positive samples from naturally infected dogs.

| No. of samples | rMAP2 ELISA titera | E. canis IFA titer |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Negativeb | 320 |

| 1 | 300 | 80 |

| 2 | 300 | 320 |

| 2 | 300 | 640 |

| 1 | 300 | 1,280 |

| 3 | 300 | ≥2,560 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 40 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 80 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 160 |

| 1 | 1,000 | 320 |

| 2 | 1,000 | 640 |

| 2 | 1,000 | 1,280 |

| 2 | 1,000 | ≥2,560 |

| 1 | ≥3,000 | 40 |

| 1 | ≥3,000 | 160 |

| 4 | ≥3,000 | 1,280 |

| 11 | ≥3,000 | ≥2,560 |

A sample was considered positive in the rMAP2 ELISA when the absorbance reading of the test serum at a specific dilution was at least three standard deviations above the mean absorbance reading of identical dilutions of standard negative control sera.

A negative ELISA result indicates a titer of <100.

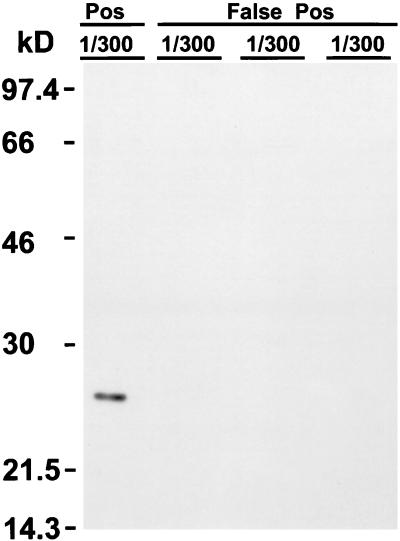

Fifty of the 53 IFA-negative samples from clinically healthy dogs tested negative in the rMAP2 ELISA. One sample was positive at a reciprocal dilution of 100, and the other two were seropositive at a reciprocal dilution of 1,000 (data not shown). Repeated IFA testing and rMAP2 ELISA using these samples confirmed the results. However, in the Western immunoblot assay, none of the false-positive samples recognized the rMAP2 antigen (Fig. 3). Therefore, there was 100% agreement when IFA-positive samples from experimentally infected animals were used, 97.3% agreement when IFA-positive samples from naturally infected animals were used, and 94.3% agreement when IFA-negative samples were used, resulting in 97.2% overall agreement between the two assays.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of rMAP2 homolog of E. canis reacted with E. canis-IFA-positive immune serum from an experimentally infected dog, Shep 35 (Pos) and normal canine serum from three IFA-negative, noninfected animals that were positive using rMAP2 ELISA (False Pos). The fraction 1/300 indicates the dilution of antibody or serum used. Molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are given on the left.

Thirty-three E. canis-IFA-negative samples, from dogs infected with various microorganisms known to infect the canine species, were tested with the E. canis rMAP2 ELISA to evaluate potential cross-reactivity (Table 3). Antibodies cross-reactive with the rMAP2 protein were not observed in serum samples from dogs infected with any of the organisms tested.

TABLE 3.

rMAP2 ELISA results using sera from dogs infected with related organisms

| No. of samples | rMAP2 ELISA titera | Organism / IFA titer |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Negativeb | Babesia canis / 40 |

| 2 | Negative | Babesia canis / 80 |

| 4 | Negative | Babesia canis / 160 |

| 3 | Negative | Babesia canis / 320 |

| 1 | Negative | Ehrlichia risticii / 160 |

| 6 | Negative | Ehrlichia platys / 40 |

| 1 | Negative | Ehrlichia platys / 80 |

| 2 | Negative | Ehrlichia ewingiic / NAe |

| 1 | Negative | Rickettsia rickettsii / 64 |

| 1 | Negative | Rickettsia rickettsii 256 |

| 3 | Negative | Haemobartonella canisd / NA |

| 1 | Negative | Bartonella vinsonii / 1,024 |

| 4 | Negative | Bartonella vinsonii / 2,048 |

| 1 | Negative | Bartonella vinsonii / 4,096 |

| 1 | Negative | Neospora caninum / 100 |

A sample was considered positive in the rMAP2 ELISA when the absorbance reading of the test serum at a specific dilution was at least three standard deviations above the mean absorbance reading of identical dilutions of standard negative control sera.

A negative ELISA result indicates a titer of <100.

Sera obtained from experimentally infected animals.

Sera obtained from defined clinical cases in which organisms were visualized in the peripheral blood of the patients.

NA, not available.

DISCUSSION

We have successfully cloned the map2 gene from E. canis and have purified rMAP2 translated from the open reading frame encoding the predicted mature protein. The predicted amino acid sequence of the MAP2 homolog of E. canis has significant homology with that of the 21-kDa MAP2 protein of C. ruminantium (4) and that of the 19-kDa MSP5 protein of A. marginale (37). Genes encoding both the MAP2 protein of C. ruminantium and the MSP5 protein of A. marginale were found to be single-copy genes that were highly conserved between various isolates of organisms within their respective species. Recombinant proteins developed from these genes have been used as diagnostic antigens to identify infected animals (4, 24, 26, 37).

Immune serum from a dog experimentally infected with E. canis was able to recognize rMAP2 in Western immunoblot assays. Interestingly, the antigenic epitopes of rMAP2 of E. chaffeensis were sensitive to heat denaturation or reduction with β-mercaptoethanol and therefore did not react with immune sera in immunoblot assays (1). Although rMAP2 of E. canis did react with immune sera, antibodies could be detected only at a reciprocal dilution of 300 or lower (Fig. 2 and 3), whereas the same samples tested positive in the ELISA at a reciprocal dilution of 3,000 or higher and IFA titers at a reciprocal dilution of 1,280 or higher. This indicates that, like E. chaffeensis rMAP2 (1) and A. marginale MSP5 (28), rMAP2 of E. canis may contain conformationally dependent epitopes.

ELISAs performed with the rMAP2 of E. canis were in 100% agreement with IFA test results when IFA-positive serum samples from experimentally infected dogs were evaluated. There was 97.3% agreement between these two assays when E. canis IFA-positive samples from naturally infected animals were used. Differences in reactivity between the ELISA and IFA tests in naturally infected animals could be explained by the use of a single recombinant protein versus the cultured, whole organisms used in the IFA test. This could cause false-negative results in the rMAP2 ELISA. Alternately, IFA testing can produce false-positive results due to the difficulty in distinguishing true- positive reactions from nonspecific antibody binding and/or an increased likelihood of cross-reactive surface antigens (35). In samples that were positive by both assays, the rMAP2 ELISA was usually able to detect antibodies at a similar or higher dilution of serum.

There was 94.3% agreement between the two assays when IFA-negative samples from clinically healthy dogs were used. Three of 53 IFA-negative samples tested positive with the rMAP2 ELISA. Interestingly, these false-positive samples did not react with the rMAP2 on Western immunoblots (Fig. 3). The samples may contain antibodies that recognized contaminating E. coli proteins that were in concentrations too small to be identified as a single band on Western immunoblot assays. Alternatively, they may have contained antibodies cross-reactive with rMAP2 but directed against epitopes that were conformationally dependent.

In cross-reactivity experiments, serum samples from animals infected with B. canis, E. platys, E. risticii, E. ewingii, R. rickettsii, B. vinsonii, H. canis, or N. caninum did not contain antibodies that recognized rMAP2 of E. canis. Previous reports have indicated that there is considerable cross-reactivity between certain Ehrlichia spp. (8, 9, 30, 32). However, samples collected from animals infected with E. platys, E. risticii, or E. ewingii did not test positive in the rMAP2 ELISA. Previous work has indicated that there is not significant cross-reactivity between E. platys and E. canis (17) and that sera from E. ewingii-infected dogs are only weakly positive for E. canis by IFA using whole antigen (32). Similarly, there does not appear to be significant cross-reactivity between E. canis and E. risticii by the IFA test, although some cross-reactive antigens have been identified by Western immunoblot assays (7, 34, 35). Although only a limited number of samples were used in our study, it appears that, at least in some cases, the rMAP2 ELISA may be able to distinguish between infections with E. canis and infections with one of these other Ehrlichia spp. Additionally, there is considered to be little if any cross-reactivity between E. canis and R. rickettsii (18) or E. canis and B. vinsonii, although coinfection with the latter two organisms may be common in certain areas of endemicity (5). B. canis and N. caninum are protozoal infectious agents of dogs, and H. canis is suspected to be in the mycoplasmal group of organisms. These species are not closely related to the ehrlichiae, and significant cross-reactivity was not expected. However, as with B. vinsonii and E. canis, dual infections with B. canis and E. canis may be common in certain areas of endemicity (14, 27).

Several studies have indicated that E. canis and E. chaffeensis are very closely related, with significant immunologic cross-reactivity between a number of antigens (3, 8, 9, 12, 32). Additionally, there is significant sequence homology between the MAP2 homologs of these two organisms (4), and unpublished data from our laboratory have shown that animals experimentally infected with E. canis contain antibodies that react to the rMAP2 of E. chaffeensis. Both organisms may infect dogs, but the clinical disease and prognosis associated with infection with these organisms can vary (5). This, coupled with increasing evidence that dogs may serve as a natural reservoir for E. chaffeensis (5, 11), indicates that a serologic assay that could distinguish between these two infectious agents would be a valuable tool for diagnosis, prognosis, and epidemiological studies.

A serological assay that can distinguish between infections with E. canis and E. chaffeensis is presently not available. The MSP5 antigen of A. marginale, an antigen homologous to MAP2 of E. canis and E. chaffeensis, is being used in a competitive ELISA using a monoclonal antibody against MSP5 (24, 37). This assay is capable of detecting both acutely and persistently infected cattle, and the MSP5 ELISA did not cross-react with sera from cattle infected with very closely related organisms (24, 37). It may be possible to design a competitive ELISA using the MAP2 homolog of E. canis similar to the assay developed using MSP5 of A. marginale. An assay such as this would provide a convenient and cost-effective way to analyze serum samples for clinical cases and epidemiologic studies. Additional studies to target antigenic differences between the MAP2 proteins of E. chaffeensis and E. canis should also be considered in an attempt to design a serologic assay that could distinguish between these two infectious agents in dogs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant from the University of Florida, Division of Sponsored Research, Project UPN# 98062369.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman A R, Barbet A F, Bowie M V, Sorenson H L, Wong S J, Bélanger M. Expression of a gene encoding the major antigenic protein 2 homolog of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and potential application for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3705–3709. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3705-3709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alleman A R, Barbet A F. Evaluation of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 3 (MSP3) as a diagnostic test antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:270–276. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.270-276.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson B E, Dawson J E, Jones D C, Wilson K H. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2838-2842.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowie M V, Reddy G R, Semu S M, Mahan S M, Barbet A F. Potential value of major antigenic protein 2 for serological diagnosis of heartwater and related ehrlichial infections. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:209–215. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.2.209-215.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Hancock S J. Sequential evaluation of dogs naturally infected with Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia ewingii, or Bartonella vinsonii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2645–2651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2645-2651.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Hancock S I. Doxycycline hyclate treatment of experimental canine ehrlichiosis followed by challenge inoculation with two Ehrlichia canis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:362–368. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouqui P, Dumler J S, Raoult D, Walker D H. Antigenic characterization of ehrlichiae: protein immunoblotting of Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia sennetsu, and Ehrlichia risticii. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1062–1066. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1062-1066.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S M, Dumler J S, Feng H M, Walker D H. Identification of the antigenic constituents of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S M, Cullman L C, Walker D H. Western immunoblotting analysis of antibody responses of patients with human monocytotrophic ehrlichiosis to different strains of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:731–735. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.731-735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S M, Popov V L, Feng H M, Walker D H. Analysis and ultrastructural localization of Ehrlichia chaffeensis proteins with monoclonal antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:405–412. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson J E, Biggie K L, Warner C K, Cookson K, Jenkins S, Levine J, Olson J G. Polymerase chain reaction evidence of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, an etiologic agent of human ehrlichiosis, in dogs from southeast Virginia. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1175–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson J E, Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fishbein D B. Serologic diagnosis of human ehrlichiosis using two Ehrlichia canis isolates. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:564–567. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumler J S, Asanovich K M, Baken J S, Richter P, Kimsey R, Madigan J E. Serologic cross-reactions among Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia phagocytophila, and human granulocytic ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1098–1103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1098-1103.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Plessis J L, Fourie N, Nel P W, Evezard D N. Concurrent babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in the dog: blood smear examination supplemented by the indirect fluorescent antibody test, using Cowdria ruminantium as antigen. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1990;57:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishbein D B, Sawterm L A, Holland C J, Hayes E B, Okoroanyanwu W, Williams D, Sikes R K, Ristic M, McDade J E. Unexplained febrile illness after exposure to ticks: infection with an Ehrlichia? JAMA. 1987;257:3100–3104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank J R, Breitschwerdt E B. A. retrospective study of ehrlichiosis in 62 dogs from North Carolina and Virginia. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13:194–201. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(1999)013<0194:arsoei>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.French T W, Harvey J W. Serologic diagnosis of infectious cyclic thrombocytopenia in dogs using an indirect fluorescent antibody test. Am J Vet Res. 1983;44:2407–2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene C E, Burgdorfer W, Cavagnolo R, Philip R N, Peacock M G. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in dogs and its differentiation from canine ehrlichiosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groves M G, Dennis G L, Amys H L, Huxsoll D L. Transmission of Ehrlichia canis to dogs by ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:937–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrus S, Bark H, Waner T. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: an update. Compend Contin Educ. 1997;19:431–444. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrus S, Kass P H, Klement E, Waner T. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: a retrospective study of 100 cases, and an epidemiological investigation of prognostic indicators of disease. Vet Rec. 1997;141:360–363. doi: 10.1136/vr.141.14.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iqbal Z, Chaichanasiriwithaya W, Rikihisa Y. Comparison of PCR with other tests for early diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1658–1662. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1658-1662.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly P J, Matthewman L A, Mahan S M, Semu S, Peter T, Mason P R, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Serological evidence for antigenic relationships between Ehrlichia canis and Cowdria ruminantium. Res Vet Sci. 1994;56:170–174. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles D P, Torioni de Echaide S, Palmer G H, McQuire T C, Stiller D, McElwain T. Antibody against an Anaplasma marginale MSP5 epitope common to tick and erythrocyte stages identifies persistently infected cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2225–2230. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2225-2230.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kordick S K, Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Southwick K L, Colitz C M, Hancock S I, Bradely J M, Rumbough R, McPherson J T, MacCormack J N. Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a Walker hound kennel in North Carolina. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2631–2638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2631-2638.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahan S M, McGuire T C, Semu S M, Bowie M V, Jongejan F, Rurangirwa F R, Barbet A F. Molecular cloning of a gene encoding the immunogenic 21 kDa protein of Cowdria ruminantium. Microbiology. 1994;140:2135–2142. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthewman L A, Kelly P J, Bobade P A, Tagwira M, Mason P R, Majok A, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Infections with Babesia canis and Ehrlichia canis in dogs in Zimbabwe. Vet Rec. 1993;133:344–346. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.14.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munodzana D, McElwain T F, Knowles D P, Palmer G H. Conformational dependence of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 5 surface-exposed B-cell epitopes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2619–2624. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2619-2624.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy G L, Ewing S A, Whitworth L C, Fox J C, Kocan A A. Molecular and serologic survey of Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and E. ewingii in dogs and ticks from Oklahoma. Vet Parasitol. 1998;79:325–339. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(98)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyindo M, Kakoma I, Hansen R. Antigenic analysis of four species of the genus Ehrlichia by use of protein immunoblots. J Am Vet Res. 1991;52:1225–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Read S M, Northcote D H. Minimization of variation in the response to different proteins of the Coomassie blue G dye-binding assay for protein. Anal Biochem. 1981;116:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fox J C. Western immunoblot analysis of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. canis or E. ewingii infections in dogs and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2107–2112. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2107-2112.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ristic M, Huxsoll D L, Weisiger R M, Hildebrandt P K, Nyindo M B A. Serologic diagnosis of tropical canine pancytopenia by indirect immunofluorescence. Infect Immun. 1972;6:226–231. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.3.226-231.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankarappa B, Dutta S K, Mattingly-Napier B L. Antigenic and genomic relatedness among Ehrlichia risticii, Ehrlichia sennetsu, and Ehrlichia canis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:127–132. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suksawat J, Hegarty B C, Breitschwerdt E B. Seroprevalence of Ehrlichia canis. Ehrlichia equi, and Ehrlichia risticii in sick dogs from North Carolina and Virginia. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:50–55. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2000)014<0050:socear>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Vliet A H M, Jongejan F, Van Der Zeijst B A M. Phylogenetic position of Cowdria ruminantium (Rickettsiales) determined by analysis of amplified 16S ribosomal DNA sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:494–498. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser E S, McGuire T C, Palmer G H, Davis W C, Shkap V, Pipano E, Knowles D P., Jr The Anaplasma marginale msp5 gene encodes a 19-kilodalton protein conserved in all recognized Anaplasma species. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5139–5144. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5139-5144.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Emergence of ehrlichioses as human health problems. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:18–29. doi: 10.3201/eid0201.960102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou C, Yang Y, Jong A Y. MiniPrep in ten minutes. BioTechniques. 1990;8:172–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]