Abstract

Previously used as part of salvage therapy, integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) have become part of the preferred antiretroviral therapy (ART) first-line regimen in most low- to middle-income countries. With the extensive use of dolutegravir in first-line ART, drug resistance mutations to INSTIs are inevitable. Therefore, active monitoring and surveillance of INSTI drug resistance is required. The aim of this study was to evaluate the genetic diversity of the integrase gene and determine pretreatment INSTI resistance in Harare, Zimbabwe. Forty-four HIV-1 Integrase sequences from 65 were obtained from treatment-naive individuals using a custom genotyping method. Drug resistance mutations were determined using the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Interpretation program. Viral subtyping was done by phylogenetic analysis and the REGA HIV subtyping tool determined recombinants. Natural polymorphisms were evaluated relative to the global subtype B and C consensus sequences. One hundred ninety-two sequences from the region were accessed from GenBank to assess differences between the Zimbabwean sequences and those from neighboring countries. No major INSTI resistance mutations were detected; however, the L74I polymorphism was detected in three sequences of the 44 (6.8%). There was little genetic variability in the Integrase gene, with a mean genetic distance range of 0.053015. The subtype C consensus was identical to the global subtype C consensus and varied from the global subtype B consensus at five major positions: T124A, V201I, T218I, D278A, and S283G. This study has provided baseline sequence data on the presence of HIV-1 subtype C Integrase gene drug resistance mutations from Harare, Zimbabwe.

Keywords: HIV-1 integrase gene, integrase strand transfer inhibitors, pretreatment drug resistance, natural polymorphisms, Zimbabwe

Introduction

The emergence and spread of HIV-1 drug resistance (HIVDR) mutations have been a major obstacle to the sustainable control of HIV using antiretroviral therapy (ART), especially in resource-limited settings (RLS) where antiretroviral drugs are limited.1 Before May 2019, most first-line ART regimens in Zimbabwe were based on two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), with protease inhibitors (PIs) and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) reserved for second-line and third-line ART in adult patients, respectively.2

Owing to the extensive use of PIs, NRTIs and NNRTIs for the past 25 years, most HIVDR data available are from the protease and reverse transcriptase genes. The INSTI, dolutegravir (DTG)'s reduced risk of resistance and adverse events, its efficacy and low cost,3,4 has made it the drug of choice relative to the NNRTIs and PIs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently recommended the use of DTG as part of first-line ART regimens,2 partly due to the increasing number of people with NNRTI resistance mutations before treatment initiation. There are currently two INSTIs registered for use in Zimbabwe, namely, DTG and raltegravir (RAL).5 The use of INSTIs has initiated the scrutiny of the prevalence of INSTI resistance mutations among ART-naive patients as a way of enhancing ART efficacy. Owing to the limited use of INSTIs in RLS, before 2019, there are a few reports on the prevalence of INSTI pretreatment drug resistance (PDR), and natural polymorphisms in INSTI-naive patients.6,7

With DTG now being a part of the preferred first-line ART regimens, it is predicted that viruses with the Q148K/R/H plus at least one additional mutation, however, may also affect susceptibility to DTG. There is, therefore, a critical need to evaluate and monitor INSTI resistance for both individual patient management and for epidemiological purposes in RLS, such as Zimbabwe. We thus assessed PDR, patterns of INSTI drug resistance, and HIV-1 integrase (IN) gene diversity in samples from INSTI-naive patients accessing care at an advanced ART clinical management center in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional retrospective study conducted between February 2019 and August 2020, at the University of Zimbabwe. The study with Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ), approval number MRCZ/B/1608, and Joint research and Ethics Committee (JREC) approval, JREC/282/18, was nested. Remnant plasma samples obtained from adults in the TENART Cohort study were used for this study. In summary, 65 plasma samples of HIV-1 infected ART-naive (11%) people and ART experienced, but INSTI-naive (89%) people, with viral loads of >1,000 copies/mL were obtained from Newlands Clinic, a private clinic offering comprehensive HIV care in partnership with the Ministry of Health and Child Care in Zimbabwe.8 Detailed information on study location and participants has been described previously.8

Laboratory methods

Viral RNA extraction

Stored plasma samples were retrieved from −80°C and left to thaw at room temperature before extraction. Viral RNA was extracted using a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. The tubes containing the extracted RNA were stored at −80°C before reverse transcription (RT).

Reverse transcription

RT was performed using a One Taq RT kit (New England Biolabs, Inc.) and the IN2: TCTCCTGTATGCAAACCCCAATAT (HXB2: 5244-5267) primer. The reaction mix for RT was prepared for a single reaction; 10 μL of M-MuLV reaction mix containing 2 μL of IN2 primer was added to 2 μL M-MuLV enzyme master mix to make a total volume of 12 μL of master mix. Six microliters of RNA was added to the respective PCR tubes and the RNA was denatured at 65°C for 5 min, after which the reaction was paused and 2 μL enzyme master mix was added to the denatured RNA. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was carried out at 45°C for 60 min and the enzyme was inactivated at 80°C for 5 min.

Nested PCR and gel electrophoresis

Nested PCR was done in the same tubes as cDNA synthesis using the OneTaq Hot start DNA polymerase enzyme (New England Biolabs, Inc.) and two sets of primers, with forward primer IN1: GGAATCATTCAAGCACAACCAGA (HXB2: 4059-4081) and the reverse primer IN2: TCTCCTGTATGCAAACCCCAATAT (HXB2: 5244-5267) in first-round PCR (PCR 1). PCR 1 master mix included 12.5 μL OneTaq Hot Start enzyme, 1 μL forward primer IN1 (5 μM), 1 μL reverse primer IN2 (5 μM), and 8.5 μL of nuclease-free water, making up a total volume of 23 μL. cDNA (2 μL) was added to each respective well and amplified using the following the conditions: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 68°C for 5 min, and then a hold step at 4°C before adding to second round (PCR 2).

PCR 2 had similar reagents to PCR 1, except that forward primer IN3: TCTACCTGTCATGGGTACCA (HXB2: 4141-4160) and the reverse primer IN4: CCTAATGGTATGTGTACTTCTGA (HXB2: 5197-5219) were used in PCR 2. PCR 1 amplicons (2 μL) were added to respective PCR 2 wells and amplified using the same conditions to PCR 1. One percent agarose gel was stained with gel green dye and run at 80 volts for 45 min, and viewed on an Azure Biosystems C200 gel imaging system to confirm amplification of an ∼1,078 bp amplicon.

PCR product cleanup and sequencing

Amplicon purification was performed using a PureLink PCR purification kit (Life Technologies). Purified amplicons were sequenced by Sanger sequencing on an ABI 3730xl Genetic Analyzer at Molecular Cloning Laboratories, in San Francisco, California. Seven sequencing primers were used, namely forward primers; HIVFORII: TCTACCTGGCATGGGTACCA (HXB2: 4141-416), 537F: CTCACTGACT AATTTATCTACTT (HXB2: 4189-4211), FGF46_F: GGATTCCCTACAATTCCCAAAG (HXB2: 4648-4669), and IN_F: TAGCAGGAAGATGGCCAGT (HXB2: 4540-4558), and reverse primers; INREVII: CCTAGTGGGATGTGTACTTCTGA (HXB2: 5197-5219), VIF_R: ATGTGTACTTCTGAACTT (HXB2: 5193-5210) and Inseq2R: CTGCCATTTGTACTGCTGTC (HXB2: 4748-4767).

Data analysis

HIV drug resistance mutation analysis

For each sample, the raw sequencing files (AB1 files) were processed and assembled to generate a consensus sequence using Geneious Prime Software 2020.1.1. Phylogenetic analysis and identity matrices were used for both intra- and inter-run quality assessment. Finally, HIVDR analysis was assessed using the calibrated population resistance for INSTI on the Stanford HIVDB (accessed on July 25, 2021) and significant drug resistance mutations were determined based on the 2019 International AIDS Society (IAS) mutation list9 Viral subtypes and recombination were determined using the REGA HIV subtyping tool.10

Analysis of the HIV-1 Integrase gene

HIV-1 integrase gene sequences were aligned using ClustalW in Geneious Prime Software 2020.1.1. A best-fitting nucleotide substitution model with generalized time reversible and gamma distribution (GTR+G) was estimated using MEGA software. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with the inferred model and 1,000 bootstraps for internal node support in Geneious Prime Software 2020.1.1.

To generate the graph of mutation prevalence: The consensus sequence from our study samples was compared with the South Africa subtype C reference sequence (AY772699). It was also compared with the global HXB2 subtype B reference sequence (K03455), noting the differences in amino acids. Amino acid variations and frequency of occurrences from the global subtype B and C consensus relative to the Zimbabwean individual subtype C fasta files were noted and recorded as polymorphic or nonpolymorphic mutations. A table of mutation prevalence percentages was constructed. The data were used to construct a graph of the mutation prevalence with respect to the subtype C sequences from Harare, Zimbabwe.

Ethical considerations

The study samples were obtained from Newlands Clinic, Harare, Zimbabwe, for a study approved by the Newlands Clinic research team, the Joint Research and Ethics Committee for the University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences and Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals (approval No. JREC Ref; 218/18), and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (approval No. MRCZ/B/1608). Patients provided written informed consent before their samples were used in this study.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study population

Samples from 65 patients with no history of prior exposure to INSTIs were identified from Newlands Clinic. At the time of genotyping, 8 (12.3%) patients were on PI-based second-line therapy, 38 (58.5%) on NNRTI-based first-line therapy and 19 (29.2%) were treatment naive. This satisfied the study selection criteria that all participants should be INSTI naive, regardless of any other ART they were taking at the time of sample collection. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Population

| Variable | Overall (n = 65) | Failed genotyping (n = 21) | Successfully genotyped (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 32 (49) | 9 (43) | 23 (52) |

| Male | 32 (49) | 11 (52) | 21 (48) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | — |

| Median log10 VL (IQR), copies/mL | 4.88 (4.49–5.32) | 4.58 (3.79–4.99) | 4.99 (4.57–5.34) |

| Median cD4 cell count (IQR), cells/mL | 301 (138.5–501.5) | 234 (153.5–499.5) | 345 (129–506) |

| Median ART duration (IQR), months |

60 (11.1–96.125) | 87 (46.13–136.88) | 33 (4–84) |

N; B—All the study participants were INSTI naive.

Some of them were treatment experienced in terms of other regimens that were not INSTIs.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range; VL, viral load.

Table 2.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Treatment naive | NRTI-based regimen | PI-based regimen | p value for trend analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median log10 VL (IQR), copies/mL |

5.01 (4.35–5.45) | 4.84 (4.44–5.31) | 5.32 (5.89–5.78) | .279 |

| Median cD4 cell count (IQR), cells/mL |

116 (34–205) | 256 (150–516) | 409 (404–600) | .02 |

| INSTI median genetic distances (IQR) |

0.078 (0.065–0.087) | 0.079 (0.067–0.091) | 0.074 (0.054–0.083) | .146 |

NRTI-based regimens (TDF/3TC/EFV, TDF/3TC/NVP, AZT/3TC/EFV, AZT/3TC/NVP).

PI-based regimes (ATVr/TDF/3TC, ATV/r/ABC,3TC, LPVr/TDF,3TC, DRVr/TDF/EFV).

NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Genotyping results

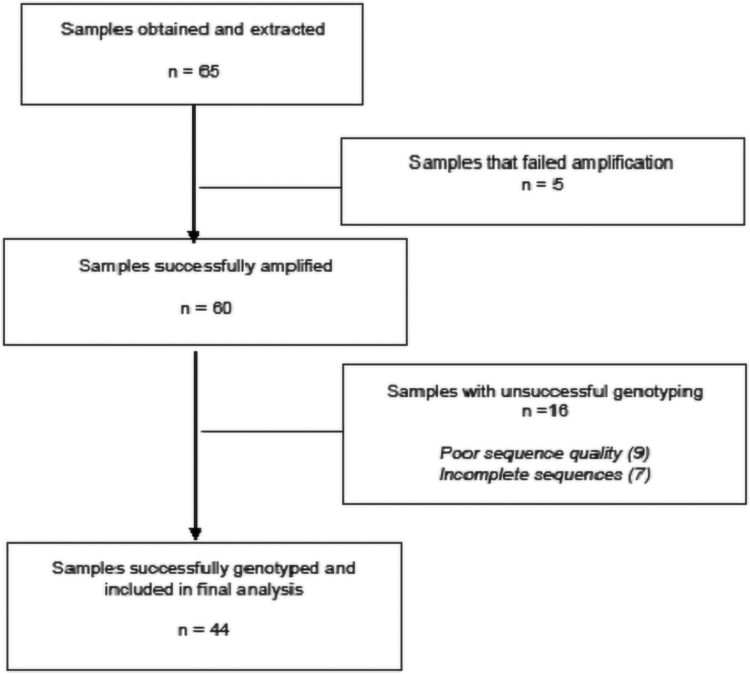

From the 65 patients included, INSTI genotypes were successfully obtained from 44 samples (68%). The flowchart of samples that were run are shown in Figure 1. There was no evidence of any major primary INSTI resistance from these patients and all the viral sequences were HIV-1 subtype C. The nonpolymorphic mutation L74V was detected in three samples (7%). The INSTI reference consensus sequence generated from these 44 samples was not significantly different from the global subtype C reference sequence. However, when compared with the HIV-1 Subtype B HXB2 reference sequences, significant differences were observed on codons 124, 201, 218, 278, and 283. These differences are not associated with any known drug resistance.11,12

FIG. 1.

The flowchart of samples from selection to analysis showing that 92% of the samples were successfully amplified. Complete and reliable HIV IN nucleotide sequences were obtained for (68%) of the samples on which genetic subtyping, phylogenetic analysis, and drug resistance analysis were performed.

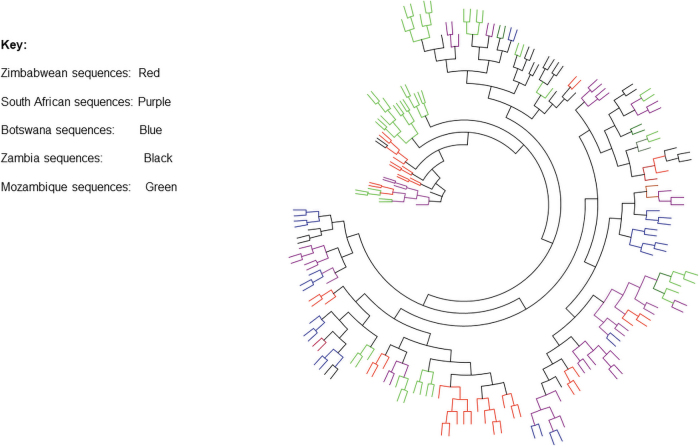

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of integrase sequences from Harare cohort and integrase sequences accessed from Los Alamos HIV database showed that integrase sequences obtained from Zimbabwe (red) clustered together and within regional sequences from Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zambia showing high similarity (Fig. 2). Homologous molecular HIV-1 integrase gene sequences across different countries showed a remarkable similarity due to their shared evolutionary history. These sequences might have evolved dependently of each other. Sequences generated from Zimbabwe were similar to those generated from other countries in the region.

FIG. 2.

A maximum likelihood tree of 192 sequences obtained from GenBank; accession numbers: JQ670790.1-JQ670845.1, MG694150.1-MG694184.1, MH161467.1-MH161528.1, and MN037428.1-MN037488.1. Integrase sequences obtained from Zimbabwe (red, mostly clustered among those from South Africa and Zambia with some clustering together with the sequences from Botswana, Color images are available online.

Analysis of the HIV-1 IN gene

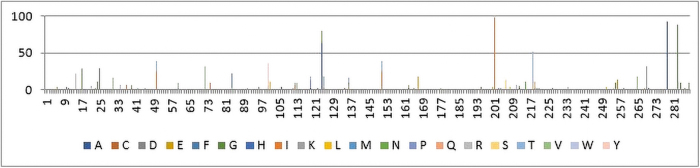

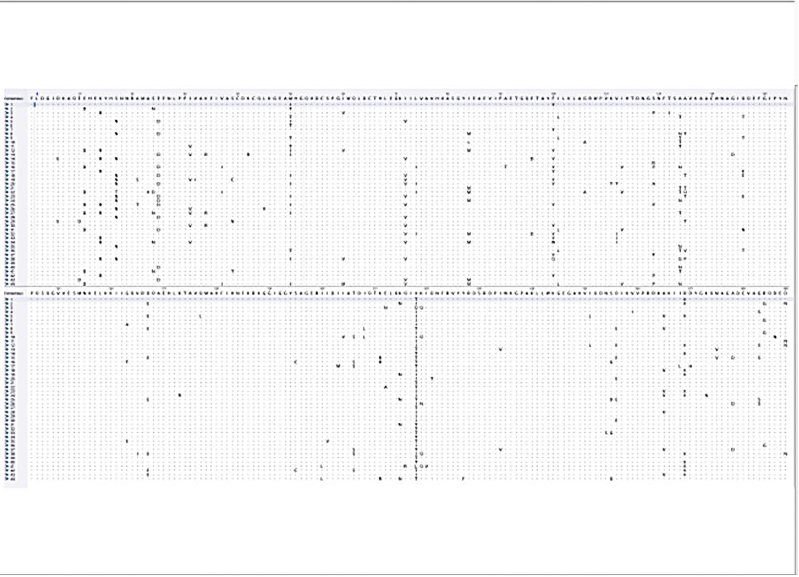

Additional HIV-1 Integrase sequences (subtype B and C) amplified from INSTI-naive individuals were retrieved from GenBank and included in the analysis. The total number of sequences analyzed were 468 subtype B and 556 subtype C sequences. The samples for these studies were collected during the period before introduction of INSTIs in sub-Saharan Africa starting from 2005 up to 2017. The graph shows the frequency of the natural nucleotide variants that were observed upon comparing the Zimbabwean sequences with subtype C and B reference sequence, respectively. The codons with the most significant differences were found at amino acid positions (124, 201, 218, 278, and 283) of the HIV-1 Integrase gene (Fig. 3). However, upon comparing the Zimbabwe consensus sequence with the regional subtype C, it was found to be similar and harboring no major mutations to the HIV-1 Integrase gene.

FIG. 3.

A mutation prevalence graph highlighting the results of a comparison between the Zimbabwean INSTI-naive sequences with the HIV-1 HXB2 reference sequences. The x-axis on the graph shows the codon positions as per the HXB2 HIV-1 Integrase gene. The y-axis shows the frequency of occurrence of the nucleotide variant. The colors are meant to depict different subtypes as per frequency difference of the nucleotide variant from the Zimbabwean sequences. INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor. Color images are available online.

Discussion

To address the rising levels of PDR, as of July 2019, the Zimbabwe National guidelines were revised to include the use of DTG as a preferred first-line ART for adults and adolescents.13 DTG is expected to address the rising levels of PDR and may minimize the emergence and transmission of HIVDR. This is the first report on primary integrase resistance from Zimbabwe. Although no evidence of major INSTI resistance was detected, this study provides the baseline of INSTI resistance surveillance and monitoring as the use of INSTIs in Zimbabwe is ramped up.

No major INSTI drug resistance mutations were detected. The only mutation of note that was detected was the L74I mutation, detected in three (6.8%) sequences. This is a polymorphic accessory mutation commonly selected by each of the INSTIs. This is consistent with existing data that show prevalence of L74I in ART-naive patients occurs at 3%–20% depending on subtype.14 Alone, L74M/I has minimal, if any, effect on INSTI susceptibility. However, they contribute reduced susceptibility to each of the INSTIs when they occur with major INSTI-resistance mutations.15,16

The absence of any major primary integrase HIVDR mutations in samples genotyped in this study and the less extensive use of INSTIs in our setting suggests that INSTI use in Zimbabwe is not likely to be hampered by PDR mutations. This is further supported by previous regional studies conducted in South Africa,17 Zambia,18 Botswana,19 and Mozambique,14 which showed little to no INSTI PDR, before the rollout of INSTIs .The similarities between regional and Zimbabwean subtype C sequences show that Zimbabwe can adopt drugs that are effectively working in other subtype C dominant countries in Africa and treatment is expected to be effective.

Moreover, considering current knowledge on high viral suppression rates with DTG, the drug will potentially play a key role toward achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 strategy to end AIDS by 2030 toward the control of the HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe.20 However, given recent findings from the ADVANCE trial showing inadequate viral suppression among patients on DTG-based first-line ART in a setting with high PDR (at 14%), vigilant monitoring of patients on INSTI-based ART is still required, despite low frequencies of INSTI PDR.21

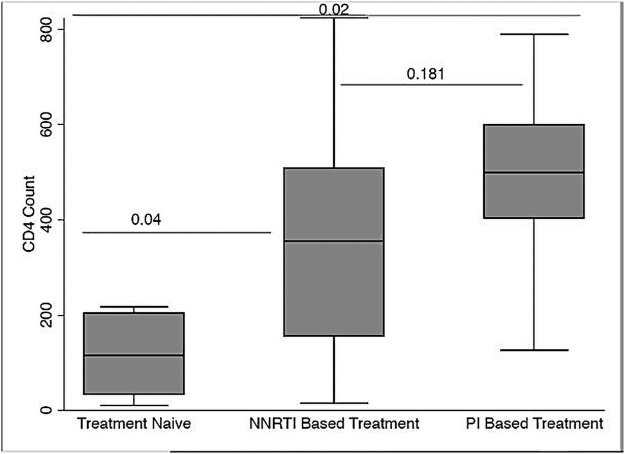

Figure 4 above shows a comparison of the p-values between the treatment naive to the NNRTI based participants to the PI based participants. All the generated sequences were subtype C, confirming the dominance of this subtype in Southern Africa as has been reported by other studies.17 These sequences are similar to those reported from within the region (Northeastern South Africa, Cape Town, and Mozambique),9–12 in terms of subtype distribution and drug resistance profiles. It has been proposed that the dominance of subtype C in sub-Saharan Africa is the result of its increased transmission efficiency compared with other HIV-1 subtypes.22

FIG. 4.

A comparison of cD4 cell counts with respect to drug regimen the participants were taking. These drugs were divided into nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor based and PIs. There were also ART-naive participants whose cD4 counts were also compared to show the trend from ART-naive to participants on PI-based regimens. ART, antiretroviral therapy; PI, protease inhibitor.

When the subtype C sequences from Zimbabwe were compared against the global subtype B consensus, many natural variants were discovered as is shown on Figure 5. Nevertheless, mutations have no link to INSTI susceptibility,11,12 unless combined with other mutations; therefore, use of INSTIs as part of the preferred first-line ART is bound to be effective in our Zimbabwean population.

FIG. 5.

A Dot Alignment conservation plot showing regions of high variability and highly conserved regions from the alignment of the 44 subtype C amino acid sequences and the global consensus sequence. Color images are available online.

The phylogenetic tree constructed out of the sequences showed that all the sequences were independent and did not show any evidence of contamination. The Zimbabwean sequences clustered with the South African sequences as well as other regional sequence signifying the population movement in the region and consequently the spread of HIV.

These results should be interpreted with consideration of the following limitations. The relatively small number of samples obtained for our analysis limits our ability to definitively provide frequency analysis of INSTI resistance mutations. However, given the limited use of INSTIs in our setting, we believe our findings provide a strong estimate of what would be observed in a larger population of patients. The design of this study only used samples from Harare, which is not a good representation of the Zimbabwean population. Use of a larger sample size, which is more representative of the Zimbabwean population, is recommended to fully assess patterns of INSTI resistance in the country and to evaluate the genetic diversity of the HIV-1 integrase gene.

This will enable researchers to clarify the chances that spontaneously generated INSTI-resistant mutants could be circulating as minority variants and be missed by routine population sequencing approaches. The genotyping rate in this study was very low (i.e., 68%). We recommend future studies to consider rescue primers in both PCR and sequencing for samples that are difficult to generate amplicon and sequence data. Increasing the genotyping rate to ≥95% would be ideal for use of the method in clinical practice.

Conclusion

This study has provided baseline sequence data on the presence of HIV-1 subtype C Integrase gene mutations from Harare, Zimbabwe. It is the first report of Integrase gene mutations in Zimbabwe. The data also suggest the absence of major RAL, Elvitegravir, and DTG mutations in the study population. In addition, the results point to the need for regular monitoring for the presence of INSTI mutation, which may render INSTIs ineffective, given they are now a part of first-line ART.

Sequence Data

HIVDR sequence data are available on GenBank.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and patients at Newlands Clinic for providing the samples and understanding the scope of this study. Our deepest gratitude goes to Prof David Katzenstein (now deceased) for providing laboratory reagents for this study.

Authors' Contributions

A.M., J.M., D.K., and B.C. conceived the study. T.S. identified participants, obtained clinical and laboratory information, and provided samples for genotyping. V.K., J.M., D.K., and A.M supervised data collection. A.M., T.W., and V.K. performed laboratory testing. A.M., J.M., and V.K. performed data analysis. M.D., T.S., T.W., B.C., J.M, and V.K. critically reviewed and finalized the article. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts, reviewed, and approved the final article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was not funded, it was made possible through the CBART sequencing project at the Biomedical Research and Training Institute in Zimbabwe. T.W., V.K., D.K., and J.M. were supported by grant number: 5D43TWO11326 from the Fogarty International Centre, NIH.

References

- 1. Manasa J, Siva D, Sureshnee P, et al. : An affordable HIV-1 drug resistance monitoring method for resource limited settings. J Vis Exp 2014;85:3–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach. Available at www.deslibris.ca/ID/10089566 (2016), accessed August 27, 2018. [PubMed]

- 3. Venter WDF, Kaiser B, Pillay Y, et al. : Cutting the cost of South African antiretroviral therapy using newer, safer drugs. SAMJ 2017;107:28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pialoux G, Marcelin A, Despiégel A, et al. : Cost-effectiveness of dolutegravir in HIV-1 treatment-experienced (TE) patients in France. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Medicine and Therapeutics Policy Advisory Committee & The AIDS and TB Directorate, Ministry of Health and Child. Guidelines for antiretroviral therapy for the prevention and treatment of HIV in Zimbabwe. Available at 88dps@mohcc.gov.zw (2019), accessed August 27, 2018.

- 6. Orta-Resendiz A, Rodriguez-Diaz RA, ngulo-Medina LA, Hernandez-Flores M, Soto-Ramirez LE: HIV-1 acquired drug resistance to integrase inhibitors in a cohort of antiretroviral therapy multi-experienced Mexican patients failing to raltegravir: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther 2020;17:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Codoñer FM, Pou C, Thielen A, et al. : Dynamic escape of pre-existing raltegravir-resistant HIV-1 from raltegravir selection pressure. Antiviral Res 2010;88:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shamu T, Chimbetete C, Shawarira-Bote S, Mudzviti T, Luthy R: Outcomes of an HIV cohort after a decade of comprehensive care at Newlands Clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe: TENART cohort. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wensing AM, Calvez V, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, et al.: 2019. update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top Antivir Med 2019:27:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pineda-Peña A-C, Faria NR, Imbrechts S, et al. : Automated subtyping of HIV-1 genetic sequences for clinical and surveillance purposes: Performance evaluation of the new REGA version 3 and seven other tools. Infect Genet Evol 2013;19:337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Low A, Prada N, Topper M, et al. : Natural polymorphisms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and inherent susceptibilities to a panel of integrase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:4275–4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. da Silva D, Wesenbeeck LV, Breilh D, et al. : HIV-1 resistance patterns to integrase inhibitors in antiretroviral-experienced patients with virological failure on raltegravir-containing regimens. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1262–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Addendum to the 2016 guidelines for antiretroviral therapy for the prevention and treatment of HIV in Zimbabwe. Available at https://www.mycpdzw.org/clinical-tools/4 (2018).

- 14. Oliveira MF, Ramalho DB, Abreu CM, et al. : Genetic diversity and naturally polymorphisms in HIV type 1 integrase isolates from Maputo, Mozambique: Implications for integrase inhibitors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012;28:1788–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. liu T, Shafer RW: Web resources for HIV type 1 genotypic-resistance test interpretation. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1608–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rhee S-Y, Kantor R, Katzenstein DA, et al. : HIV-1 pol mutation frequency by subtype and treatment experience: Extension of the HIVseq program to seven non-B subtypes. AIDS 2006;20:643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bessong PO, Nwobegahay J: Genetic analysis of HIV-1 integrase sequences from treatment naive individuals in Northeastern South Africa. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:5013–5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inzaule S, Hamers RL, Noguera-Julian M, et al. : Primary resistance to integrase strand transfer inhibitors in patients infected with diverse HIV-1 subtypes in sub-Saharan Africa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:1167–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seatla KK, Choga WT, Mogwele M, et al. : Comparison of an in-house ‘home-brew’ and commercial ViroSeq integrase genotyping assays on HIV-1 subtype C samples. PLoS One 2019;14, e0224292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/909090 (2014), accessed October 21, 2020.

- 21. Siedner MJ. Moorhouse MA, Simmons B, et al. : Reduced efficacy of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors in patients with drug resistance mutations in reverse transcriptase. Nat Commun 2020;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ariën KK, Abraha A, Quin˜ones-Mateu ME, et al. : The replicative fitness of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M, HIV-1 group O, and HIV-2 isolates. J Virol 2005;79:8979–8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]