Abstract

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; previously known as vulvovaginal atrophy or atrophic vaginitis) involves symptoms of vaginal dryness, burning, and itching as well as dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary urgency, and recurrent urinary tract infections. It is estimated that nearly 60% of women in menopause experience GSM but the majority of these women do not bring up this concern with their health care provider. Studies also show that only 7% of health care providers ask women about this condition. This may be due to embarrassment or thinking this is a normal part of aging, both by patients and health care providers. This condition is progressive and may affect many aspects of a woman’s physical, emotional, and sexual health. This article is intended to address the signs, symptoms, and significant impact this condition can have for women and help health care providers be more comfortable knowing how to ask about GSM, diagnosis it, and review the various treatment options that are available.

Keywords: atrophic vaginitis, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, vulvovaginal atrophy

INTRODUCTION

It has been called vulvovaginal atrophy or atrophic vaginitis. The newer term, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), was introduced by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) in 2014. GSM is defined as “a collection of signs and symptoms associated with estrogen deficiency that can involve changes to the labia, introitus, vagina, clitoris, bladder and urethra.”1

WHAT IS GSM AND WHY SHOULD WE CARE?

What GSM means clinically is that the vaginal and vulvar tissue becomes thin and dry, which often leads to a burning sensation, itching, and pain and dryness during sex. Sometimes these symptoms are so bad that women are unable to have sex (penile/vaginal intercourse), which of course can contribute to low sex drive. As I discuss with my patients, most women do not look forward to sex if it hurts! (Note: Although this article is primarily addressed to GSM in heterosexual women, this condition can affect women regardless of sexual preference or practices.)

GSM is caused by decreased estrogen. Estrogen helps the tissue stay lubricated and elastic. As women age and enter menopause, they have decreased estrogen and the vaginal and vulvar tissue starts to thin and weaken and has less elasticity and lubrication. Even the length of the vagina can shorten and the entrance to the vagina (introitus) narrows, often causing pain or difficulty with intercourse. This can also happen prior to natural menopause due to other hypoestrogenic conditions (eg, when a woman is breastfeeding or has had surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy affecting her ovaries) or as a result of certain medical conditions (eg, primary ovarian insufficiency, hypothalamic amenorrhea) or medications (eg, tamoxifen, leuprolide, danazol, medroxyprogesterone acetate, aromatase inhibitors).

It may sound like GSM just causes vaginal dryness and discomfort, but it can actually affect many aspects of a woman’s health, not only physically but psychologically and sexually. In my gynecologic practice, I frequently see women who have entered menopause and may have made it past the hot flashes and night sweats but are now noticing more dryness and pain with intercourse. When we talk about it, some of my patients admit to avoiding any intimate contact with their partner because they worry that this may lead to sex. Eventually, their partner often starts to feel rejected and the relationship itself suffers.

Unfortunately, even medical providers with training in women’s health and gynecology often do not get much education on the vulva and usually even less on sexual health. Although we may ask women as they age about hot flashes or night sweats, we are often guilty of not asking important questions such as “Are you noticing any vaginal dryness or trouble lubricating during sex?” or inquiring if these changes are affecting a woman’s sexual relationship. One study of more than 3,000 women with symptoms of GSM showed that only 7% of providers asked about these changes.2

It is estimated that although nearly 60% of women in menopause experience GSM, the majority of these women do not discuss this concern with their health care provider.3 This may be due to embarrassment, cultural reasons, or even thinking that this is a normal part of aging and nothing can be done. We, as providers, may even overlook these changes or possibly also think they are a normal part of aging.

In addition to pain with sex that in turn affects a woman’s sex drive, GSM can cause discomfort to the point where a woman may stop being as physically active, affecting her physical and emotional health. GSM can contribute to more frequent vaginal and urinary tract infections due to an increase in vaginal pH and changes in the vaginal microflora. The underlying connective tissue also thins and is more susceptible to inflammation or infection. Pelvic organ prolapse with urinary retention and/or urinary incontinence may also occur.4

A diagnosis of GSM should include obtaining a thorough patient history. Ask the patient about onset, duration, prior treatment, potential vulvar irritants (Table 1), other medical conditions or medications, and previous surgery, including prior cancer or cancer treatments. Vaginal infections should be ruled out and sexually transmitted infections should also be considered.

Table 1.

Vulvar hygiene

| Things to avoid |

| Tight-fitting clothing |

| Synthetic underwear |

| Scented soaps, body wash, and bubble bath |

| Scented detergents |

| Laundry softener, dryer sheets |

| Baby wipes, flushable wipes |

| Feminine hygiene sprays, douches, and wipes |

| Dyed/colored toilet paper |

| Constant use of pantiliners |

| Washcloths, scrubbies, and loofahs |

| Try instead |

| Loose-fitting clothing |

| Cotton underwear in daytime |

| No underwear at night |

| Fragrance-free pH-neutral soaps/detergents |

| Tub bath without additives and at comfortable temperature |

| Use fingertips for gentle vulvar washing ideally with water only |

| Try a sport water bottle, perineal bottle, or bidet |

| Gently pat vulva dry |

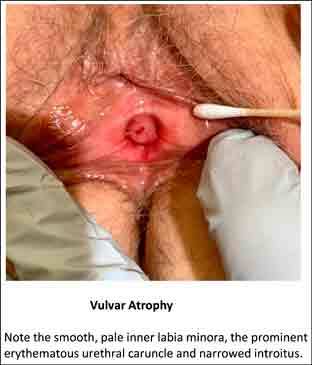

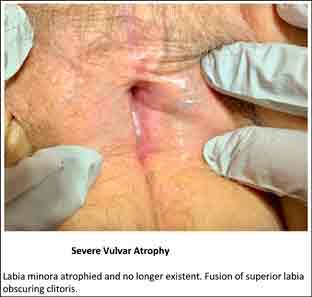

Clinically, the external genitalia may appear pale and thin. With inflammation, sometimes the tissue can be erythematous with excoriations. In severe cases, the labia minora may be essentially nonexistent, having fused to the labia majora. The introitus may narrow and a urethral caruncle is often seen. There is loss of vaginal rugae and decreased elasticity of the vagina, which can make distention of the vagina with a speculum very painful for many women. The cervix may sometimes be difficult to visualize not only due to pain with opening of the speculum, but it also may become flush with the vaginal wall and the cervical os itself may become stenotic. At times, an increased yellow or brown, sometimes malodorous, discharge is present.

Nitrazine paper applied to the introitus can help confirm a diagnosis of vaginal atrophy. A normal well-estrogenized vagina will have a pH ranging from 3.5 to 5.0. In the absence of infection (eg, bacterial vaginosis) or semen from recent intercourse, a pH of 5.5 or higher is seen with vaginal atrophy.5

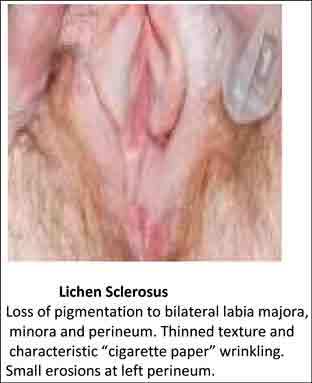

Other vulvar disease may include some of the same patient complaints such as external irritation, burning, or itching and possibly pain with intercourse. For example, lichen sclerosis usually appears as white skin changes that tend to affect the labia minora and/or majora and often the perineum or perianal region (Figure 1). Other disorders could include lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, dermatitis, vitiligo, or mucous membrane pemphigoid; thus, biopsies are recommended to confirm diagnosis of any suspected vulvar disorder or any lesion of the vulva that does not respond to treatment.

Figure 1.

Loss of pigmentation to bilateral labia majora, minora, and perineum. Thinned texture and characteristic “cigarette paper” wrinkling. Small erosions at left perineum.

There are a variety of different treatment options for GSM. The choice of treatment may depend on the severity of symptoms and should include a discussion of risks, benefits, and effectiveness, address a patient’s preference, and review any concerns she may have regarding hormonal treatment. I begin by discussing nonhormonal options (Table 2), such as vaginal lubricants and moisturizers, with my patients, but I also give them information regarding vaginal estrogen and other prescription therapies.

Table 2.

Nonhormonal options for genitourinary syndrome of menopause

| Lubricants |

| Water based |

| KY |

| Astroglide |

| Good Clean Love |

| Sylk |

| Pjur |

| YES |

| Silicone based |

| Uberlube |

| Eros |

| Pink |

| ID Millennium |

| Wet Platinum |

| Pjurmed Premium Glide |

| Oil based |

| Elegance Women’s Lubricants |

| Oils (olive, coconut, avocado, vitamin E, Crisco) |

| Moisturizers |

| Replens |

| RepHresh |

| Luvena |

| Lubrigyn |

| Sylk natural intimate moisturizer |

| Yes vaginal moisturizer |

| Canestima |

| Femallay Moisturizing Suppositories |

Many women find that using lubricants with intercourse helps make sex more comfortable. The brands commonly found over the counter are usually water-based lubricants. Many menopausal and perimenopausal women find that these absorb fairly quickly and do not provide enough comfort. Silicone-based lubricants tend to last longer and provide more lubrication. Coconut, vitamin E, avocado, or olive oils work well but any oil-based lubricant should not be used with condoms, as they weaken latex and some women find they may be more prone to vaginal infections with these lubricants.

There are also nonhormonal products called vaginal moisturizers. As women age, most of us notice that our skin gets thinner and dryer and needs more moisture. Such changes also happen to the vagina and vulva. Just like women may use a daily moisturizer on other areas of the body, they can also use a vaginal moisturizer either daily or 2 to 3 times per week. Many of these products contain ingredients like those found in facial products such as hyaluronic acid, which helps tissue retain moisture and stay lubricated.6

There are a variety of prescription treatments available for GSM (Table 3). Low-dose vaginal estrogen is the gold standard treatment for GSM but women (and their health care providers) can still be reluctant to consider this option. It does not help that the product information has to list possible risks including cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and dementia. NAMS has suggested that this “black box warning” be removed from vaginal estrogen products, as the amount of hormone absorbed into the body when used vaginally is very low and does not have the same potential health risks as systemic estrogen.7

Table 3.

Prescription treatments for genitourinary syndrome of menopause

| Product |

| Vaginal estrogen ring |

| Estring (7.5 µg of estradiol released once a day): inserted by patient or clinician every 90 d |

| Vaginal estrogen insert |

| Vagifem/Yuvafem (10 µg of estradiol): insert 1 tablet vaginally every night for 2 wk, then twice weekly |

| Imvexxy (4 µg and 10 µg of estradiol): insert vaginally every night for 2 wk, then twice weekly |

| Vaginal estrogen cream |

| Estrace (100 µg of estradiol/g): insert 0.5-1 g vaginally every night for 2 wk, then twice a week |

| Premarin (0.625 mg of conjugated estrogen/g): insert 0.5-1 g vaginally every night for 2 wk, then twice a week |

| Other |

| Ospemifene (Osphena; 60 mg daily oral tablet), selective estrogen receptor modulator |

| Prasterone (Intrarosa; 6.5 mg nightly intravaginal suppository), dehydroepiandrosterone |

Even women taking systemic estrogen for vasomotor symptoms of menopause may still experience GSM and benefit from local treatment. If a woman’s primary concern is GSM, local rather than systemic estrogen is recommended, as it has been shown to be more effective for GSM and to have lower risks.8 Vaginal estrogen has also been shown to be more effective in the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections9 and improvement of incontinence, while systemic estrogen may actually worsen incontinence.10

Vaginal estrogen is available in various prescription forms, including creams, intravaginal tablets or inserts, and a vaginal ring. In general, it is recommended to treat daily for the first 2 weeks, then decrease administration to twice weekly. It can often take 4 to 6 weeks, and sometimes longer, to notice an improvement.

Although the vaginal estrogen inserts or ring have been shown to have the least systemic absorption,11 I find (Figures 2 and 3) that these forms of vaginal estrogen may initially not be adequate for my patients with significant atrophy. I often start their treatment course with vaginal estrogen cream. Even though the systemic absorption may be a bit higher, it is still quite low and the cream may be applied to the vulva as well. I prefer using the more bioidentical estradiol cream (Estrace) but find that the amount recommended by the manufacturer is usually too much (2-4 g) and may have higher systemic absorption. I start with 0.5 to 1 g for most of my patients; as in systemic hormone therapy, the lowest effective dose is recommended. Some women may need to start with slightly higher doses, then decrease the amount as the vulvovaginal tissue health improves or transition to the vaginal inserts or ring. (Somewhat confusingly, there is also a vaginal ring called Femring that provides systemic estrogen to help treat hot flashes and also works locally to treat GSM, but the ring used for GSM [Estring] has very minimal absorption.)

Figure 2.

Note the smooth, pale inner labia minora, the prominent erythematous urethral caruncle, and narrowed introitus.

Figure 3.

Labia minora atrophied and no longer existent. Fusion of superior labia obscuring clitoris.

Some women may be uncomfortable or physically unable to insert the cream, tablets, or suppositories. In this case, the Estring may be used and changed by the provider every 3 months in the office.

Systemic estrogen can increase the thickness of a woman’s uterine lining (the endometrium) and potentially lead to uterine cancer or a precancerous thickening (hyperplasia). If a woman is taking systemic estrogen (and still has her uterus), she also needs to take progesterone to help prevent the uterine lining from getting too thick. When a woman is using only low-dose vaginal estrogen, she does not also need to take progesterone because the amount of estrogen absorbed into the body is extremely low and does not appear to increase the risk of uterine cancer (although endometrial safety has not been studied beyond 12 months of use). NAMS has suggested removing the boxed warning on vaginal estrogen but cautions that women are still advised to call their provider if they do have any bleeding, as this can potentially be a warning sign of uterine cancer or hyperplasia.

Side effects of local estrogen may include vaginal discharge, vulvovaginal candidiasis, breast tenderness, and vaginal bleeding, although these appear to be dose related and may vary with the formulation. As above, any vaginal bleeding needs to be investigated and a woman with undiagnosed vaginal/uterine bleeding should not be started on vaginal estrogen until a thorough evaluation has been performed. Some patients may also feel that the cream is too messy, while others may like the lubricating affect it may have and the option to apply a small amount externally to the vulva.

Even women with a history of breast cancer or other potential contraindications to systemic estrogen may consider using low-dose vaginal estrogen. It is still recommended to try nonhormonal options first, but for many women this is just not enough. In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued an opinion stating that vaginal estrogen could be considered for women currently undergoing breast cancer treatment or for women with a personal history of breast cancer who are unresponsive to nonhormonal treatment and the data do not show an increased risk of cancer recurrence.12 Although some women are understandably still worried about the potential risk, other women may feel that this is a quality-of-life issue and are relieved to know that this is a treatment option. If vaginal estrogen is considered, it is often advised to consider the vaginal estradiol inserts or the low-dose estradiol ring due to the fixed amount of medication and the lack of significant systemic absorption. The Imvexxy vaginal inserts come in a very low-dose form of 4 µg, which may be preferable if there is concern about systemic absorption. It is usually advised to discuss this first with a woman’s oncologist or primary care provider.

Women taking aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment are often advised not to use vaginal estrogen. However, a 2019 meta-analysis of 8 studies showed no increase in serum estradiol levels after 8 weeks of local hormone treatment in women taking aromatase inhibitors, which appears reassuring.13

The risk of venous thromboembolism was not increased with local estrogen therapy based on observational studies.14

A newer product called prasterone (Intrarosa) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016. Prasterone is a nightly vaginal insert that is plant derived and appears very effective in the treatment of vaginal dryness and painful intercourse. Through intracellular steroidogenesis, prasterone is converted into estrogen and testosterone in the cells of the vagina. It appears to be very low risk in terms of low to no absorption of hormones into the bloodstream and may eventually be found to be a good option for women who have contraindications to systemic estrogen; however, the FDA currently still requires the warning that it has not been studied in women with breast cancer and, as with vaginal estrogen preparations, should not be used in women with undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding.15

Ospemifene (Osphena) is an oral, nonhormonal method to treat moderate to severe dyspareunia associated with vulvovaginal atrophy. It is a selective estrogen receptor modulator and is taken daily. Ospemifene is not an actual hormone; rather, it is an estrogen agonist/antagonist, acting on estrogen receptors in the vagina to treat vaginal dryness and subsequent pain with intercourse. It may be helpful in women who are either unwilling or unable to use vaginal estrogen. Side effects include hot flashes/night sweats and ospemifene may increase the risk for thromboembolic complications. Ospemifene may theoretically increase the risk of uterine cancer as well; however, as with the vaginal estrogen studies, it appears to be safe in studies up to 1 year of use. It appears to have antiestrogenic effects on the breast but is not approved for women with breast cancer.16,17

Other nonhormonal options for GSM now include physical procedures such as laser therapy, which are reported to help vaginal dryness by causing microabrasions in the vaginal tissue to stimulate neovascularization and promote increased collagen production. While these procedures may be promising, they are currently not FDA approved, are costly, and usually require more than 1 treatment with a possible need for retreatment in the future.

In addition to dyspareunia, vaginal and bladder infections, prolapse, and incontinence, women with GSM often notice significant pain with pelvic examinations and pap smears. Insertion of the speculum can be quite painful, especially if the vaginal introitus has narrowed significantly. The actual opening of the speculum may be even more painful, especially if a woman is no longer sexually active. The vaginal tissue is thin and loses elasticity. It is important to understand these changes and do our best to help a woman be more comfortable so she does not avoid coming to see us.

Helpful techniques include using a lubricated narrow Pedersen or a pediatric speculum if necessary. I sometimes will apply topical lidocaine jelly to the introitus and/or speculum first. I also may use only one gloved, lubricated finger for the pelvic examination. If a woman is very anxious or visibly contracting her pelvic floor muscles, I will ask her to squeeze as hard as she can around my gloved finger, then ask her to breathe and relax as I gently insert my finger a bit more. I always tell my patient to let me know if I am causing her pain and that I will stop at any time if she tells me to. This may help her relax, allowing a more thorough examination and giving her some control over an often uncomfortable and intimidating procedure.

In a woman with very severe atrophy who is unable to tolerate any examination or any attempt at penile insertion, it is often helpful to try treating with vaginal estrogen for 4 to 6 weeks as well as have her work with a vaginal dilator to assist in gently stretching the tissue. There are many companies that sell graduated vaginal dilators. There is also the Milli, which is a patient-controlled dilator that expands 1 mm at a time (Table 4). It can be helpful to refer a patient to a good pelvic floor physical therapist if she would like additional instruction and assistance with dilator use and relaxation.

Table 4.

Dilator resources

| Resource |

| Website |

| Vaginismus.com (www.vaginismus.com) |

| Soul Source (www.soulsource.com) |

| MiddlesexMD (https://middlesexmd.com) |

| Cooper Surgical (www.coopersurgical.com) |

| CMT Medical (www.cmtmedical.com) |

| Other dilator options |

| Milli expanding dilator (www.millimedical.com) |

| FeMani vibrating massage wand (https://femaniwellness.com) |

My motivation for writing this article was to help women and their health care providers become more familiar with GSM and the treatment options available. This is a progressive condition and unfortunately is not often addressed by us or our patients until it becomes severe. We, as medical providers, need to be aware that this is an issue for many women and understand the impact it may have on a woman’s overall health as well as her sexual health and quality of life. We need to look for it, ask about it, and be familiar with options that can help. It can greatly relieve a woman to know that although these can be normal changes associated with aging, she does not have to live with them or be embarrassed to ask for treatment options (Table 5 includes a list of retail websites where women may purchase lubricants, moisturizers, or vibrators). I hope this article will help us, as providers, realize the extent that this condition can affect a woman’s life and empower us to know we can offer her some relief.

Table 5.

Retail websites

| Website |

| MiddlesexMD (www.middlesex.md) |

| Good Vibrations (www.goodvibes.com) |

| Eve’s Garden (www.evesgarden.com) |

| Adam and Eve (www.adamandeve.com) |

| Babeland (www.babeland.com) |

| Target (www.target.com; sexual health) |

| Walgreens (www.walgreens.com; sexual lubricants) |

| CVS (www.cvs.com; sexual health) |

| Sexuality Resource Center (www.sexualityresources.com) |

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions: Kelly Jo Peters, DO, conceived of the presented idea, developed the tables, and wrote the final manuscript. The author has given final approval to the manuscript.

Financial Support: No funding was supplied by outside sources.

References

- 1.North American Menopause Society . Menopause practice: A clinician’s guide, 6th ed. Pepper Pike, OH: North American Menopause Society; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman, ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: Findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med 2013 Jul;10(7):1790-9. DOI: 10.1111/jsm.12190, PMID:23679050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine KB, Williams RE, Hartmann KE. Vulvovaginal atrophy is strongly associated with female sexual dysfunction among sexually active postmenopausal women. Menopause 2008 Jul-Aug;15(4 Pt 1):661-6. DOI: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31815a5168, PMID:18698279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dessole S, Rubattu G, Ambrosini G, et al. Efficacy of low-dose intravaginal estriol on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2004 Jan-Feb;11(1):49-56. DOI: 10.1097/01.GME.0000077620.13164.62, PMID:14716182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson K, Risberg B, Heimer G. The vaginal epithelium in the postmenopause--Cytology, histology and pH as methods of assessment. Maturitas 1995 Jan;21(1):51-56. DOI: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)00863-3, PMID:7731384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krychman ML, Dweck A, Kingsberg S, Larkin L. The role of moisturizers and lubricants in genitourinary syndrome of menopause and beyond. OBG Management; 2017. April:SS1-SS10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinkerton J, Liu J, Santoro NF, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women; commentary from the North American Menopause Society on low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy labeling. Menopause 2020 Jun;27(6):611-3. DOI: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long CY, Liu CM, Hsu SC, Wu CH, Wang CL, Tsai EM. A randomized comparative study of the effects of oral and topical estrogen therapy on the vaginal vascularization and sexual function in hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Menopause 2006 Sep-Oct;13(5):737-43. DOI: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227401.98933.0b, PMID:16946685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Apr 16;(2):CD005131 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2, PMID:18425910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grady D, Brown JS, Vittinghoff E, Applegate W, Varner E, Snyder T; HERS Research Group . Postmenopausal hormones and incontinence: The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. Obstet Gynecol 2001 Jan;97(1):116-20. DOI: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01115-7, PMID:11152919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 Aug;(8);CD001500. DOI: https://doi.org/110.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub3, PMID:27577677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell R; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice . ACOG committee opinion no. 659: The use of vaginal estrogen in women with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2016 Mar;127(3):e93-6. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlovic RT, Jankovic SM, Milovanovic JR, et al. . The safety of local hormonal treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy in women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer who are on adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy: Meta-analysis. Clin Breast Canc 2019 Dec;19:e731-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.clbc.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North American Menopause Society (NAMS) . The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2020 Sep;27(9):976-92. DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millicent Pharma. Prasterone (Intrarosa) product website. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://intrarosahcp.com/

- 16.Duchesnay. Ospemifene (Osphena) product website. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://hcp.osphena.com/

- 17.Soe LH, Wurz GT, Kao CJ, Degregorio MW. Ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: Potential benefits in bone and breast. Int J Womens Health 2013 Sep;5:605-11. DOI: 10.2147/IJWH.S39146, PMID:24109197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]