Abstract

Currently, gut microbiota living in the gastrointestinal tract, plays an important role in regulating host’s sleep and circadian rhythms. As a tool, gut microbiota has great potential for treating circadian disturbance and circadian insomnia. However, the relationship between gut microbiota and circadian rhythms is still unclear, and the mechanism of action has still been the focus of microbiome research. Therefore, this article summarizes the current evidences associating gut microbiota with factors that impact host circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder. Moreover, we discuss the changes to these systems in sleep disorder and the potential mechanism of intestinal microbiota in regulating circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder via microbial metabolites. Meanwhile, based on the role of intestinal flora, it is provided a novel insight into circadian related insomnia and will be benefit the dietary treatment of circadian disturbance and the circadian related insomnia.

Keywords: Circadian rhythm, Intestinal microbiota, Sleep disorder, Dietary treatment

Introduction

Circadian rhythms are daily oscillations of numerous of biological processes directed by endogenous clocks, which refer to important regulators of numerous functions and the change of life activity. Circadian biological timing system was composed of peripheral oscillators, which is closely related to the basic physiological functions and metabolism (Rachael et al., 2020). In general, the human body learning ability, efficiency and emotion all have the condition of circadian rhythm fluctuation. Recent years, according to the statistics of the World Health Organization, the global sleep disorder rate is 27%. With the advance of technology, circadian rhythms neurology sleep almost attribute to human’s work in shifts, stay up late, min-night social, anxiety and so forth. Generally, the difference between the endogenous biological clock and the exogenous social anxiety will lead to the circadian disturbance and sleepless. Once the circadian rhythm is destroyed, it will lead to a series of physical and psychological problems: loss of appetite, inability to concentrate, immunity decline, cardiovascular disease, obesity (Capers et al., 2015) and Alzheimer.

Recent studies show intestinal flora plays an important role in the regulation of circadian rhythm, and circadian rhythm changes can also alter both microbial community structure and metabolic activity. The lack of intestinal microflora and microbial metabolites will in turn affect the expression of circadian clock genes in the central and liver (Leone et al., 2015), thus regulating the circadian rhythm. Microbiota rhythms are regulated by diet and time of feeding, which can significantly impact host immune and metabolic function. About 60% of intestinal microbes in mice have circadian rhythm fluctuation, while 10% in human intestines, which indicates that the intestinal microflora also has its own biological clock, and it can perform its functions with a cyclical manner in 24-h circadian cycle. It is suggested that the circadian rhythm can be influenced by the biological clock of intestinal flora and dietary habits. In the case of a low-fat diet, the short chain fatty acids produced by beneficial bacteria in mammalian intestinal microbes can directly regulate the expression of circadian clock genes in liver cells (Leone et al., 2015). In addition, in vitro experiments conducted by Leone et al. also found that polysaccharide metabolites (sodium acetate and sodium butyrate and short chain fatty acids) related to intestinal flora metabolism, could significantly change the expression of bam11 and per2 clock genes in mouse hepatocytes.

Circadian rhythms align biological functions with regular and predictable internal environment intestinal flora to optimize function and health. However, it is unclear that the intestinal microbiome is regulated by circadian rhythms via intrinsic circadian clocks as well as via the host organism. In this review, we will cover the relationship between intestinal microbiota and brain in circadian rhythms, and the evidence linking the disruption of gut microbiota with specific circadian rhythms disorders, and then the corresponding regulation strategies are proposed based on the interaction between circadian rhythms and intestinal flora. Further and the potential of gut-microbiota-targeted strategies, such as dietary interventions and fecal microbiota transplantation, as promising therapies that help patients to maintain healthy circadian rhythms.

Circadian sleep rhythm disorders threaten human health

Circadian rhythm sleep disorder will destroy intestinal microbial homeostasis, cause intestinal flora imbalance and change the diversity (richness) of intestinal flora, eventually affecting the circadian rhythm (Parkar and Li 2019). Sleep deprivation can increase oxidation stress, reduce immunity and cause inflammation. Dietary foods, such as coffee, strong tea and garlic could cause clock dysregulation, sleep deprivation and shift experience, which alter the expression of clock genes and the structure of the microbial community, so interfering with sleep patterns in mice also alters the structure and diversity of intestinal flora. After sleep deprivation, DNA synthesis, circulating immune complex and natural killer cell (NK cell) activity, CD lymphocytes showed a decreasing trend. In addition, some sleep deficiency will affect the function of liver cells, affect the activity of liver cells, reduce the secretion of antibodies. Generally, sleep deprivation stimulates the release of CRF in the hypothalamus, which stimulates the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ATCH) cell in the pituitary to release ATCH. Acting on the adrenal gland, ATCH stimulates the vagus nerve and increases the release of corticosterone (CORT) by the adrenal cortical cells (AC cell). They act together to alter intestinal movement, immune function, permeability, and ultimately cause changes in intestinal flora (Gentile and Weir, 2018). Jet lag significantly increase body weight and blood glucose content by affecting the composition of human intestinal microbiome. When alternating day and night, the amount of Paraprevotella, Fusobacteria and Fusobacteriales would increase in their intestinal microflora. Whereafter the symptoms were improved by consumption of intestinal flora with antibiotics (Song et al., 2020a; 2020b).

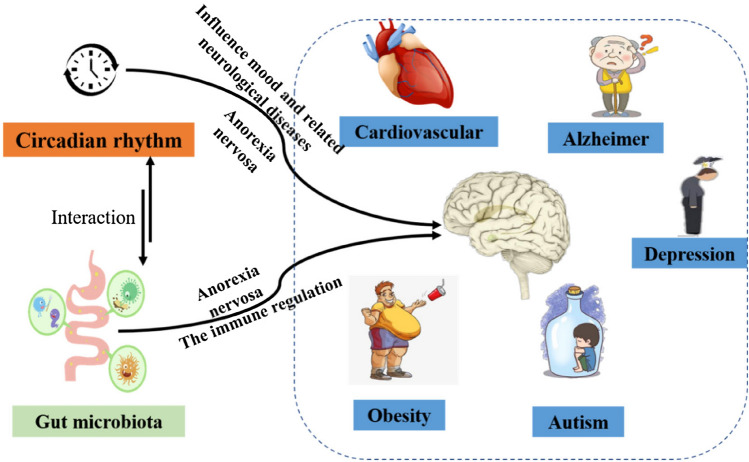

Accumulating research show the incidence of some metabolic pathway of intestinal microbes was decreased after the subjects had normal sleep time, comparing with the beginning of the sleep time shift (Liu et al., 2020). In general, purine metabolism increased during the acute circadian rhythm changes. After the shift of sleep time in the morning, the ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose (ADP-l,d-Hep) biosynthesis, allantoin degradation IV (anaerobic), acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) fermentation to butanoate II, acetylene degradation, and the super pathway for purine deoxyribonucleoside degradation was significantly enriched. Previous studies have shown that purine metabolism is likely to lead to colitis (Chiaro et al., 2017), autism spectrum disorders, Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Liu et al., 2020) and other diseases (Fig. 1). In addition, after the sleep time shift, it can be seen that the acetyl CoA fermentation to butyrate II pathway, related with the metabolism of SCFA of diet intestinal metabolites by microorganisms, is significantly increased (Liu et al., 2020). In the study, after two nights of partial sleep deprivation, the abundance of families Coriobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae increased, while the abundance of Tenerictes decreased. Circadian insomnia will influence ecology of intestinal flora, neurotransmitter, the host's energy metabolism (Hu et al., 2018), inflammation (Li et al., 2018) and psychological functions (Dalile et al., 2019). It’s reported that these bacteria related-circadian rhythm are related to dietary food metabolic disturbance in animals or human body. At the same time, sleep deprived subjects had lower insulin sensitivity on fasting and postprandial (Benedict et al., 2016). In short, circadian rhythm and intestinal flora interact with each other, and result in circadian rhythm disorders and human healthy.

Fig. 1.

A crosstalk between intestinal flora and circadian rhythms related diseases via gut microbiota-brain acting on circadian related diseases

The hazards of insomnia caused by circadian rhythm disorders

Although several hypotheses for insomnia have been proposed, including neurotransmitter depletion, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, neuroimmune activation, and neurotrophic factor dysfunction. No single hypothesis can explain the complex mechanisms observed in the field of neuropsychiatric research (Cheng et al., 2020).

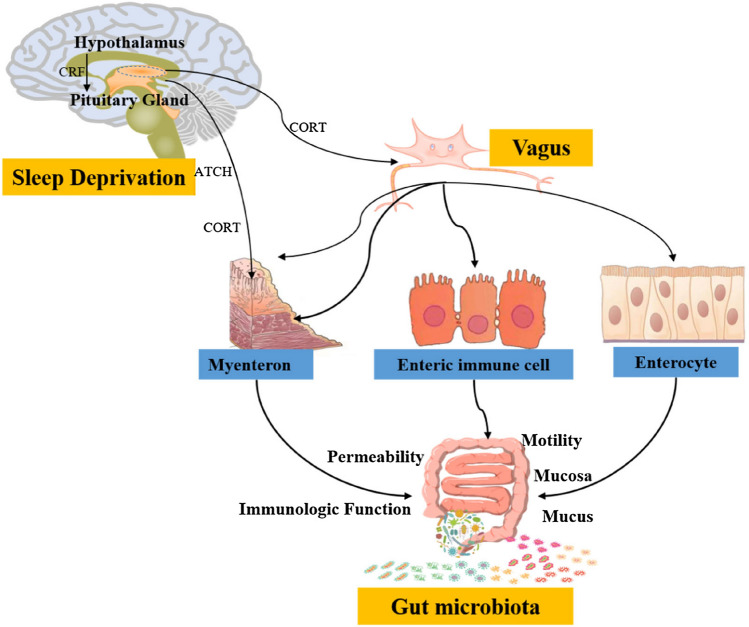

Abnormal of the HPA axis to be related a range of affective and stress-related disorders. Intestinal microbiota regulates circadian rhythm disorder and sleep deprivation via gut multiple microbiota-brain ways (Fig. 2). The dysregulation of HPA axis caused by psychological or physiological stress (such as overtime work, insomnia and other stress) can disrupt the balance of intestinal flora by increasing intestinal mucosal permeability and activating intestinal immunity. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) acts on the intestinal plexus in a master-cell-dependent manner, leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction (Gentile and Weir, 2018). When intestinal permeability changes, the immune cell surface toll-like receptor (TLR) recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS), leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors that trigger an inflammatory response. Inflammation and pathogen infection are the pathological basis of various mental disorders, which can lead to anxiety, depression or circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorders. The clock gene regulates the rhythmic production of cortisol in intestinal epithelial cells, independent of the HPA axis. Dysgenicity of microbial communities not only destroy expression of circadian rhythm gene, but also affect periodic production of ileal corticosterone, leading to sustained high levels of cortisol (Melinda et al., 2015).

Fig. 2.

Molecular mechanisms of gut microbiota regulate sleep deprivation via gut multiple microbiota-brain ways

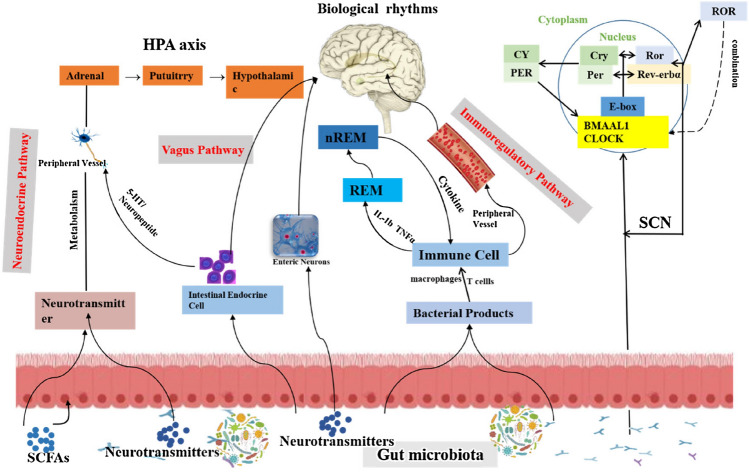

The accumulated literatures prove that the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the regulatory center of circadian rhythm by neural projecting and endocrine transmitter diffusing (Song et al., 2020a; 2020b). For example, pineal gland, one of the endocrine glands in thalamus, secrets melatonin to promote the occurrence of sleep, improve the quality of sleep, and regulate the circadian rhythm. Melatonin is eventually metabolized in the liver, so the damage of hepatocytes also can affect circadian rhythm. The gut flora has a crucial effect on the brain through a mechanism known as the gut microbiota—enteric nervous system (ENS)—vagus nerve—brain pathway, which affects the rest of life. In addition, intestinal flora interacts with biological genes to regulate biological rhythms. Poor sleep schedules and inappropriate strong external stimuli also affect the gut flora, which in turn affects circadian rhythms (Bass, 2012).

Therefore, it is necessary to study the influence of intestinal flora on sleep to study its influence on the brain, especially the area of the brain that controls biological rest and rest. The related pathways and mechanisms of intestinal flora's involvement in sleep regulation will be further studied to provide new ideas for the treatment of circadian disturbance. The underlying mechanisms of gut flora interacts with the nervous system can help us understand neurological insomnia and find meaningfully suitable treatment strategies.

The underlying mechanisms of gut microbiota interacts with the nervous system

The vast majority of bacteria plays an important role in multiple host functions neuropathic disease and biological clock function (Song et al., 2019; Parkar and Li 2019). There is growing evidence that neurotransmitters produced by gut bacteria affect host physiology. The beneficial bacteria perform vital protective functions essential to the preservation of causing inflammation in the body and the brain. This results in digestive, immune and endocrine functions as well as neurotransmission.

Intestinal flora can produce hormones and neurotransmitters, acting on the activation or inhibition of corresponding neurons, therefore promoting circadian rhythm sleep via the afferent of vagus nervous system (Lyte, 2014; Timothy et al., 2015). Intestinal flora can also promote the secretion of CRH and glucocorticoid (GC) to regulate the secretion of intestinal endocrine cells, exchange of information between brain and gastrointestinal tract, increase the body's response to exogenous stress factor, activation of the amygdala receptors, promotion the release of CRH, eventually reduce slow wave sleep (Hakim et al., 2015; Liao et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2017; Kitamura et al., 2016). The lack of certain intestinal microorganisms increases the permeability of the blood brain barrier causing substances and changes in the morphology and number of neurons. Additionally, symbiotic metabolites produced by intestinal flora can drive chronic inflammation, thus affect brain functions, such as stress response and sleep structure. For example, short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), as the most abundant microbiome derived metabolites in the intestinal cavity, has a strong ability to inhibit intestinal inflammation. In general, it can prevent pathogen invasion and maintain barrier integrity, mainly by activating G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) or inducing their inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) to further affect gene expression. Microbial-derived tryptophan (TRP) metabolites, secondary bile acids, and succinic acids also act as coordinators of host metabolic stability.

In addition, some intestinal microbial metabolites (e.g.: 5-hudroxytryptamine (5-HT), Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and dopamine (DA)) can act on the brain through the blood–brain barrier and affect circadian rhythm (Cenit et al., 2014). Intestinal flora directly affects the secretion of 5-HT. The levels of 5-HT and DA increased in the striatum of rats with gastric mucosal injury, which inhibited sleep-promoting neurons, thus reducing the intestinal pain threshold and shortening the circadian sleep time. The reduction of intestinal pain threshold due to injury was positively correlated with sleep duration (Krueger et al., 2001; Yano et al., 2015). LPS is an intestinal endotoxin, and PLA 2-II with bactericidal function has been found to be upregulated by platelet activator (PAF), inflammatory mediators and LPS. Rats with a reduced intestinal flora were more susceptible to LPS-induced injury, preventing PAF-induced shock, PLA 2-II activation, and intestinal injury.

The interacts between intestinal flora and the intestinal cells regulate the secretion and transmission of neurotransmitters (in Fig. 3). Briefly, the upper part of the human hypothalamic optic chiasm has specialized nerve nucleus, namely suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is the timing controller of life activities. They affect surrounding organs and tissues through neurotransmitter endocrine and body fluid pathways, control and regulate sleep, wakefulness, and endocrine. The rhythm is controlled by the main clock in the upper eyelid nucleus in the hypothalamus. It strictly regulates the neurotransmitters by transcription, translation and expression of interlocking feedback and feedforward circuits (Bass and Takahashi, 2010). In this case, the e-box sequence and the two molecules of the BMAL-1/CLOCK is dimer and inhibitions of the BMAL-1/CLOCK in the nucleus will limit the transcription of downstream genes (including itself), forming the negative of the circadian rhythm clock. The orphan receptor gene associated with retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and the Rev-ERBα gene encoding the nuclear receptor regulates the host's intestinal circadian rhythm (Mohawk et al., 2012). Intestinal cells not only transcribe central clock genes but also translate central clock proteins with diurnal cycles that are different from those of SCN (Pardini et al., 2005). Thus, intestinal cells can regulate many intestinal functions, such as nutrient absorption, xenogenetic and endophytic detoxification, and colon motility, independently of the SCN. This peripheral biological clock is also fed back to the SCN through humoral or metabolic cues.

Fig. 3.

A network of the communication between gut microbiota and circadian rhythms

Researchers have found that the level of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the plasma of patients with anxiety and depression was significantly increased, and zonulin and fatty acid binding proteins 2 (FABP2) could increase intestinal barrier permeability, which can act as biomarkers for intestinal disorders. The biomarkers show an obvious increase, thus suggesting that anxiety and depression related to intestinal disorders and impaired intestinal barrier integrity (Kubota et al., 2001). Simultaneously, cortisol can inhibit the synthesis of immune cells of these cytokines. When the low levels of immune cells are exposed to cytokines caused by the formation of bacterial cell walls (Cermakian et al., 2013), high levels of cytokines can lead to sleep disruption, ultimately affecting the circadian rhythm (Marshall and Born, 2002; Gentile and Weir, 2018). Microbial information alters the circadian rhythm of the intestinal flora via the vagus nerve transmitting signals to the brain. In contrast to sleep-deprived mice, levels of the metabolites 5-HT and dopamine were elevated in parts of the brain in normal mice, suggesting that sleep deprivation treatment mitigated the stress-induced drop in the density of 5-hydroxytryptamine-positive and dopamine-positive cells. 5-HT is synthesized directly by releasing 5-HT3 receptors in intestinal endocrine cells (EEC) and directly targets brain peptide YY through the vagus nerve (Strader and Woods, 2005). In summary, disturbances of the biological clock can lead to changes in the flora, which can also change the intestinal cell density. The damage of the intestinal barrier (intestinal microbes and intestinal cells) can lead to biological anxiety, depression, and severely affect physiological activities.

Regulation of gut microbiome for the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorder

The effect of sleep disorder on intestinal microflora is mainly affecting its circadian rhythm, disrupting the homeostasis of intestinal microflora, thus changing the richness of intestinal flora. Poroyko et al. used 16S rRNA diversity analysis to detect the intestinal flora of chronic fragmented sleep model mice, and found significant changes in intestinal flora at the level of phylum, family, order and genus (Poroyko et al., 2016). The results showed the highly dominant growth of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae and the reversible changes of Lactobacillaceae. In addition, Some researchers detected intestinal flora by fluorescence quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and found that escherichia coli, Bacteroides, beneficial bacteria bifidobacteria and lactobacillus decreased and harmful Clostridium perfringens increased in rats with sleep disorder (Crumeyrolle-Arias et al., 2014). Compared with normal sleep, the proportion of intestinal bacteria firmicutes/Bacteroides in stool of people tested for sleep disorders was significantly higher. Based on novel bioinformatics techniques and 16S rDNA sequencing technology, the differences of intestinal microbiota between patients with sleep disorders and healthy subjects were illustrated. It was found that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in insomnia disorder group was significantly up-regulated, while that of Phylum Firmicutes and Proteobacteria was down-regulated. Else people with insomnia disorder had more gram-negative bacteria and significantly more potential pathogenicity.

The oscillation of host circadian rhythm will affect the composition and function of intestinal microbiota, meanwhile, the normal operation of host circadian clock depends on the diurnal changes of intestinal microbiota. Both sleep and intestinal flora have circadian rhythm phenomenon, and the influence of sleep disturbance on intestinal flora is mainly to affect its circadian rhythm, destroy intestinal microbial homeostasis, and cause the imbalance of intestinal flora. In a complex intestinal microecology, different eating habits have different effects on specific intestinal microorganisms. Diet is one of the most important factors affecting the diversity and richness of gut microbes, and its functional factors tend to interact with intestinal flora to produce some metabolites. Both functional factors and metabolites can rapidly change the composition and metabolic activity of intestinal flora. Dietary recommendations tailored to individual circumstances will play an important role in the regulation of circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder.

Dietary interventions

The regulation of dietary structure has been found to improve circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder through intestinal flora, among which dietary polysaccharide, polyphenols and peptides have a good effect in regulating the intestinal microbiota (Table 1) (Wu et al., 2019). Recent studies have confirmed that these polysaccharide, polyphenols and peptides can regulate the intestinal micro-ecological balance to some extent. Researchers have found that the level of polysaccharides in the plasma of patients with anxiety and depression is significantly increased, and zonulin and fatty acid binding proteins 2 (FABP2), which can act as biomarkers for intestinal disorders and increased intestinal barrier permeability. Studies have reported that during chronic or intermittent dietary fiber deficiency, the gut microbiota resorts to host-secreted mucus glycoproteins as a nutrient source, leading to erosion of the colonic mucus barrier, resulting in dysfunction of the intestinal barrier. Polysaccharides are difficult to be digested by the body's own enzymes and need to be degraded by intestinal microorganisms. In turn, the selective digestion of polysaccharides by different kinds of intestinal microorganisms also affects the colonization and reproduction of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract. Plant polysaccharides are converted into SCFAs by the intestinal flora, which not only provide energy for intestinal epithelial cells, promote their proliferation, and maintain the intestinal barrier function, but also maintain intestinal homeostasis and improve immune tolerance. Peptides can also regulate the secretion of some cytokines, interleukins and intestinal hormones, as well as reduce the serum level of diamine oxidase, thereby improving the intestinal immune function and circadian rhythm disorders.

Table 1.

The dietary interventions, their metabolites and the potential effects of circadian rhythm

| Food intervention | Metabolites | Animal model | Result | Flora | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypeptide | Amino acid | Chronic REM sleep deprivation in the elderly | The expression of PPARy and its coactivator PGC-1α↓, interleukin↓ | Bacteroidetes, Clostridia, Lachnospiraceae abundance ↑ | |

| Indole | Sleep deprivation | Malondialdehyde (MDA) ↓superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) ↑and cell apoptosis↓ | |||

| Polyphenol | Catechin | Sleep restriction (SR) | Mitochondrial oxphos-related gene ↑ and SIRT1 and PGC-1A protein ↑, AMPK↑ | Bifidobacterium, Desulfovibrio abundance ↑ | Broussard et al. (2016) |

| Benzoic acid | Periodic oscillations | Expression levels of PGC-1A, NRF-1, ERRa and TFAM genes in mitochondrial biosynthesis ↑ | Xiao et al. (2018) | ||

| Polysaccharide | Beta glucan | Variation of light wave | Reverse weight ↑, liver weight to body weight ratio ↑, fasting plasma insulin content ↓ plasma leptin and remission of glucose intolerance ↓ | Abundance of Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae ↑ | Cheng et al. (2021) |

| β-2, 1-fructose polymer | Light wave | Abundance of Lachnospiraceae ↑ | |||

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | High fat fed mouse model | Intestinal endocrine cells hormones↑ lipid metabolism↑ | SCFAs stimulates the expression of G-protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) and GPR41 | Lu et al. (2016) | |

| Flavone | Flavonoids (ADME) | Obesity and insulin resistance | A high-fat diet negatively affects ↓, inflammation ↓, and improves metabolic function | Ackermania ↑ | Roopchand et al. (2015) |

| Long-term dark environment | weight ↓and intestinal microflora disorders ↓ | Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria↑, Firmicutes↓ | |||

| Probiotics | Short chain fatty acids | Tail vein injection of SCFsA | Acetic acid and propionic acid concentrations in blood ↑,number of SCFs related flora ↑ | Lachnospiraceae, Streptococcus and Lachnoclostridium ↑ | Derrien et al. (2015) |

| Bacteriocin | Healthy 4-day-old yellow-feathered broiler | Daily feed intake ↑,the growth of pathogenic bacteria ↓, and the SIgA content of duodenal mucosa ↑ | Firmicutes abundance ↑,and the abundance of beneficial bacteria such as enterostreptococcus and UCG 013↑ | Liu et al. (2012) | |

| Niacinamide | NAD | Intestinal homeostasis disorder | Intestinal mucin 2(MUC2)↑, and factor -κB (NF-κB) ↑ | Number of lactobacillus intestinalis↑, The number and abundance of intestinal flora ↑ | Ridlon et al. (2014) |

| Nicotinamide ribose | Alcoholic depression | BDNF and TrkB protein expression ↑, Akt/GSK3β/β -catenin protein ↑ | Akkermansia ↑, abundance of Prevotella, Barnesiella ↓ | Hamity et al. (2017) |

Song et al. studied the regulatory effect of cyclocarya paliurus flavonoids (CPF) on circadian mice, and the results showed that CPF improved intestinal microbial structure imbalance caused by circadian rhythm disorder (Song et al., 2020a; 2020b). In addition, Cheng. et al. showed that glucan and inulin regulate the expression of clock genes, suggesting that probiotics supplementation could be a new dietary approach to alleviate circadian dysregulation (Cheng et al., 2020). The intake and variety of polysaccharides will affect the structure and function of human intestinal flora via its metabolites, and the diurnal differences of metabolites will affect intestinal microecology and clock (Gentile and Weir, 2018; St-Onge et al., 2015). Evidence showed improving the distribution of gut microbes can significantly improve sleep disorders and mood (Melinda et al., 2015), by regulating the composition of intestinal flora and decrease of excitatory related to circadian nervous insomnia.

Oral probiotics and faecal microbiota transplantation

Probiotics play an important role in intestinal mucosal immunity, permeability and bacteriostasis. Oral probiotics can significantly improve the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients, and significantly increase the number of intestinal beneficial bacteria (i.e. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus) (Rao et al., 2009). Sukiyaki Koyomi found that heat-killed SBC8803 regulated circadian behavior and sleep homeostasis significantly, increasing nighttime exercise activity and wake time (Miyazaki et al., 2014). Probiotics can directly supplement the intestinal probiotics in the body to ensure the balance of intestinal flora and promote the normal expression of cytokines (Li et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2020).

Some probiotics also improve circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder by targeting the microbiome–gut–brain axis (MGBA). Lin Alexander investigated the effect of psychobarbital fermentation lactobacillus PS150TM on sleep improvement and found that pentobarbital orally administered PS150TM significantly reduced the sleep latency and increased the sleep duration in mice (Lin et al., 2019). Probiotics could be used to restore the normal intestinal flora in the study on the effect of probiotics on the intestinal flora disorder caused by antibiotics. Among them, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium infantile and Enterococcus faecalis were found to be normal intestinal cocci in healthy human body. After taking oral probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation, it can suppress some pathogenic bacteria in the intestinal tract, make the intestinal normal peristalsis, and regulate the balance of intestinal flora. In addition, intestinal flora can produce certain hormones and neurotransmitters, such as lactobacillus producing acetylcholine (Ach), Escherichia coli and Enterococcus producing 5-HT, and Bacillus producing DA, promoting sleep–wake conversion (Thaiss et al., 2014), thus affecting the circadian rhythm disorder.

Future research direction

It is now unclear that the effects of the intestinal flora influence the function and structure of the intestinal barrier under physiological conditions. Therefore, adjusting intestinal flora and its associated flora—gut—brain—axis may be a new clue for strategies improving circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder and circadian disturbance, then there will be some correlation research need to discuss: (1) the neuroendocrine—HPA axis pathways and intestinal flora metabolism pathways. (2) The effects on structure and function of the intestinal mucosal barrier by intestinal flora.

In this review, we focus on the interaction between host circadian rhythms and intestinal flora. The HPA axis, the main neuroendocrine system that responds adequately to stress, entero-peptide receptors expressed by vagal afferent neurons and the mechanism have been studied, which be helpful for our understanding of the relationship between intestinal flora and circadian rhythms neurology sleep disorder metabolism. Therefore, this review puts forward a new strategy of nutrition intervention to prevent circadian disturbance by regulating intestinal micro-ecological balance. At the same time, diversified diet may bring better curative effect, which deserves further discussion.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2019A610433).

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo Municipality (Grant No. 2019A610433).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ruilin Zhang, Email: ruilin_zhang92@163.com.

Laiyou Wang, Email: laiyouwang@hotmail.com.

References

- Ahmad A, Helen O, Moi CC. High-glycemic-index carbohydrate meals shorten sleep onset. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(2):426–430. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansoleaga B, Jove M, Schluter A, Garcia-Esparcia P, Moreno J, Pujol A, Pamplona R, Portero-Otin M, Ferrer I. Deregulation of purine metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2015;36(1):68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J. Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491(7424):348–356. doi: 10.1038/nature11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010;330(6009):1349–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict C, Vogel H, Jonas W, Woting A, Blaut M, Schurmann A, Cedernaes J. Gut microbiota and glucometabolic alterations in response to recurrent partial sleep deprivation in normal-weight young individuals. Molecular Metabolism. 2016;5(12):1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central gaba receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(38):16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard JL, Eve Van Cauter. Disturbances of sleep and circadian rhythms: novel risk factors for obesity. Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity. 23: 353–359 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Capers PL, Fobian AD, Kaiser KA, Borah R, Allison DB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the impact of sleep duration on adiposity and components of energy balance. Obesity Reviews. 2015;16(9):771–782. doi: 10.1111/obr.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenit MC, Matzaraki V, Tigchelaar EF, Zhernakova A. Rapidly expanding knowledge on the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1842: 1981–1992 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cermakian N, Lange T, Golombek D, Sarkar D, Nakao A, Shibata S, Mazzoccoli G. Crosstalk between the circadian clock circuitry and the immune system. Chronobiology International. 2013;30(7):870–888. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.782315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WY, Lam KL, Li XJ, Kong Alice PS, Cheung PC. Circadian disruption-induced metabolic syndrome in mice is ameliorated by oat β-glucan mediated by gut microbiota. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2021;118216:267. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WY, Lam KL, Kong PS, Cheung CK. Prebiotic supplementation (beta-glucan and inulin) attenuates circadian misalignment induced by shifted light-dark cycle in mice by modulating circadian gene expression. Food Research International. 137: 109437 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chiaro TR, Soto R, Stephens WZ, Kubinak JL, Petersen C, Gogokhia L, Bell R, Delgado JC, Cox J, Voth W. A member of the gut mycobiota modulates host purine metabolism exacerbating colitis in mice. Science Translational Medicine. 9: eaaf9044 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crumeyrolle-Arias M, Jaglin M, Bruneau A, Vancassel S, Cardona A, V Da ugé, Naudon L, Rabot S. Absence of the gut microbiota enhances anxiety-like behavior and neuroendocrine response to acute stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 42: 207–217 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(10):701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota - gut - brain communication. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;16(8):461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien M,van HV, Johan ET. Fate, activity and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiology. 23: 354–366 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362(6416):776–780. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevi F, Zolla L, Gabriele S, Persico AM. Urinary metabolomics of young Italian autistic children supports abnormal tryptophan and purine metabolism. Molecular Autism. 2016;7:47. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenwright AJ, Pothula KR, Bhamidimarri SP, Chorev DS, Basle A, Firbank SJ, Zheng HJ, Robinson CV, Winterhalter M, Kleinekathofer U, Bolam DN, van den Berg B. Structural basis for nutrient acquisition by dominant members of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 541: 407 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan K, MacSharry J, Casey PG, Shanahan F, Joyce SA, Gahan, CGM. Unconjugated bile acids influence expression of circadian genes: A potential mechanism for microbe-host crosstalk. PloS One. 11: e0167319 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hakim F, Wang Y, Carreras A, Hirotsu C, Zhang J, Peris E, Gozal D. Chronic sleep fragmentation during the sleep period induces hypothalamic endoplasmic reticulum stress and PTP1b-mediated leptin resistance in male mice. Sleep. 2015;38(1):31–U367. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamity MV, White SR, Walder RY, Schmidt MS, Brenner C, Hammond DL. Nicotinamide riboside, a form of vitamin B3 and NAD+ precursor, relieves the nociceptive and aversive dimensions of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in female rats. Pain Volume. 2017;158(5):962–972. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JM, Lin SL, Zheng BD, Cheung PK. Short-chain fatty acids in control of energy metabolism. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2018;58(8):1243–1249. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1245650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek JL, Musaad SM, Holscher HD. Time of day and eating behaviors are associated with the composition and function of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017;106(5):1220–1231. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.156380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Katayose Y, Nakazaki K, Motomura Y, Oba K, Katsunuma R, Terasawa Y, Enomoto M, Moriguchi Y, Hida A, Mishima K. Estimating individual optimal sleep duration and potential sleep debt. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:35812. doi: 10.1038/srep35812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger JM, Obal F, Fang JD, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;933(1):211–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Z, Wang YH, Li Y, Ye CQ, Ruhn KA, Behrendt CL, Olson EN, Hooper LV. The intestinal microbiota programs diurnal rhythms in host metabolism through histone deacetylase 3. Science. 365: 1428 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kubota T, Fang JD, Brown RA, Krueger JM. Interleukin-18 promotes sleep in rabbits and rats. AJP Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2001;281(3):R828–R838. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone V, Gibbons SM, Martinez K, Hutchison AL, Huang EY, Cham CM, Pierre JF, Heneghan AF, Nadimpalli A, Hubert N, Zale E, Wang Y, Huang Y, Theriault B, Dinner AR, Musch MW, Kudsk KA, Prendergast BJ, Gilbert JA, Chang EB. Effects of diurnal variation of gut microbes and high-fat feeding on host circadian clock function and metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Niu Q, Wei Q, Zhang YQ, Ma X, Kim SW, Lin M, Huang R. Microbial shifts in the porcine distal gut in response to diets supplemented with enterococcus faecalis as alternatives to antibiotics. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):41395. doi: 10.1038/srep41395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, van Esch B, Wagenaar G, Garssen J, Folkerts G, Henricks P. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2018;831:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li LQ, Long HP, Liu J, Liu JK. Xylarinaps a–e, five pairs of naphthalenone derivatives with neuroprotective activities from xylaria nigripes. Phytochemistry. 186: 112729 (2021) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liang X, Bushman FD, Fitz-Gerald GA. Rhythmicity of the intestinal microbiota is regulated by gender and the host circadian clock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(33):10479–10484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501305112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao F, Zhang TJ, Mahan TE, Jiang H, Holtzman DM. Effects of growth hormone–releasing hormone on sleep and brain interstitial fluid amyloid-beta in an APP transgenic mouse model. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2015;47:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Shih CT, Huang CL, Wu CC, Lin CT. Hypnotic effects of lactobacillus fermentum ps150tm on pentobarbital-induced sleep in mice. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2409. doi: 10.3390/nu11102409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YY, Fatheree NY, Mangalat N, Rhoads JM. Lactobacillus reuteri strains reduce incidence and severity of experimental necrotizing enterocolitis via modulation of TLR4 and NF-κB signaling in the intestine. AJP-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2012;302(6):608–617. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00266.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Wei ZY, Chen JY., Chen K, Mao XH, Liu QS, Dan Z. Acute sleep-wake cycle shift results in community alteration of human gut microbiome. mSphere. 5: e00914–19 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lu YY, Fan CN, Li P, Lu YF, Chang XL, Qi KM. Short Chain Fatty Acids Prevent High-fat-diet-induced Obesity in Mice by Regulating G Protein-coupled Receptors and Gut Microbiota. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:37589. doi: 10.1038/srep37589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyte M. Microbial endocrinology: Host-microbiota neuroendocrine interactions influencing brain and behavior. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(3):381–389. doi: 10.4161/gmic.28682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Born J. Brain-immune interactions in sleep. International Review of Neurobiology. 2002;52:93–131. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(02)52007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melinda LJ, Henry B, Michelle B, Donald PL, Dorothy B. Sleep quality and the treatment of intestinal microbiota imbalance in chronic fatigue syndrome: a pilot study. Sleep Science. 2015;8(3):124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming O, Kevin H, Ted A, Thomas SA. Adrenergic signaling plays a critical role in the maintenance of waking and in the regulation of REM sleep. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92(4):2071–2082. doi: 10.1152/jn.00226.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, Itoh N, Yamamoto S, Higo-Yamamoto S, Nakakita Y, Kaneda H, Shigyo T, Oishi K. Dietary heat-killed Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 promotes voluntary wheel-running and affects sleep rhythms in mice. Life Sciences. 2014;111(1–2):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2012;35:445–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer Disease. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2015;47:3. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini L, Kaeffer B, Trubuil A, Bourreille A, Galmiche JP. Human intestinal circadian clock: Expression of clock genes in colonocytes lining the Crypt. Chronobiology International. 2005;22(6):951–961. doi: 10.1080/07420520500395011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkar SG, Kalsbeek A, Cheeseman JF. Potential role for the gut microbiota in modulating host circadian rhythms and metabolic health. Microorganisms. 2019;7(2):41. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng MF, Lee SH, Rahaman SO, Biswas D. Dietary probiotic and metabolites improve intestinal homeostasis and prevent colorectal cancer. Food and Function. 2020;11(12):10724–10735. doi: 10.1039/d0fo02652b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poroyko VA, Carreras A, Khalyfa A, Khalyfa AA, Leone V, Peris E. Chronic sleep disruption alters gut microbiota, induces systemic and adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in mice. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:35405. doi: 10.1038/srep35405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachael MK, Jacinta F, Ultan H, Dervla G, Séamus S, John HM, Andrew NC. Greater social jetlag associates with higher HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes: a cross sectional study. Sleep Medicine. 2020;66:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao AV, Bested AC, Beaulne TM, Katzman MA, Iorio C, Berardi JM, Logan AC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Gut Pathogens. 2009;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2014;30(3):332–338. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopchand DE, Carmody RN, Kuhn P, Moskal K, Rojas-Silva P, Turnbaugh PJ, Raskin I. Dietary polyphenols promote growth of the gut bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and attenuate high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2015;64:847–858. doi: 10.2337/db14-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song ZW, Cai YY, Lao XZ, Wang X, Lin XX, Cui YY, Kalavagunta PK, Liao J, Jin L, Shang J, Li J. Taxonomic profiling and populational patterns of bacterial bile salt hydrolase (BSH) genes based on worldwide human gut microbiome. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0628-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Yang SC, Zhang X, Wang Y. The relationship between host circadian rhythms and intestinal microbiota: A new cue to improve health by tea polyphenols. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;61(1):139–148. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1719473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Ho CT, Zhang X, Wu ZF, Cao JX. Modulatory effect of cyclocarya paliurus flavonoids on the intestinal microbiota and liver clock genes of circadian rhythm disorder mice model. Food Research International. 138(Pt A): 109769 (2020a) [DOI] [PubMed]

- St-Onge MP, Roberts A, Shechter A, Choudhury AR. Fiber and saturated fat are associated with sleep arousals and slow wave sleep. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2015;12(1):19–24. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader AD, Woods SC. Gastrointestinal hormones and food intake. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):175–191. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Levy M, Zilberman SG, Tengeler A, Abramson L, Korem, Zmora, Kuperman, Biton, Gilad, Harmelin, Shapiro, Halpern, Segal, Elinav. Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell. 159: 514–529 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Timothy G, Dinan Roman M, Stilling, Catherine, Stanton, John, F, Cryan. Collective unconscious: How gut microbes shape human behavior. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 63: 1–9 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Green SJ, Ece M, Phillip E, Vitaterna MH. Circadian disorganization alters intestinal microbiota. Plos One. 9: e97500 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, MacDonald TT, Troost F, Cani P.D, Theodorou V, Dekker J, Meheust A, de Vos WM, Mercenier A, Nauta A, Garcia-Rodenas CL. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 312: G171–G193 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wu Y, Wan J, Choe U, Pham Q, Schoene NW, He Q, Li B, Yu L, Wang Thomas TY. Interactions between food and gut microbiota: Impact on human health. Annual Review Food Science and Technology. 2019;10(25):389–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-032818-121303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M, Zheng WX, Jiang GP. Bifurcation and Oscillatory Dynamics of Delayed Cyclic Gene Networks Including Small RNAs. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics. 2018;49(3):883–896. doi: 10.1109/TCYB.2017.2789331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, Nagler CR, Ismagilov RF, Mazmanian SK, Hsiao EY. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161(2):264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]