Abstract

Sepsis remains a significant cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity, especially in low and middle-income countries. Neonatal sepsis presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms that necessitate tests to confirm the diagnosis. Early and accurate diagnosis of infection will improve clinical outcomes and decrease overuse of antibiotics. Current diagnostic methods rely on conventional culture methods, which is time-consuming and may delay critical therapeutic decisions. Nonculture-based techniques including molecular methods and mass spectrometry may overcome some of the limitations seen with culture-based techniques. Biomarkers including hematological indices, cell adhesion molecules, interleukins and acute phase reactants have been used for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. In this review, we examine past and current microbiological techniques, hematological indices and inflammatory biomarkers that may aid sepsis diagnosis. The search for an ideal biomarker that has adequate diagnostic accuracy, early in sepsis is still ongoing. We discuss promising strategies for the future that are being developed and tested that may help us diagnose sepsis early and improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: neonate, sepsis, diagnosis, biomarkers, molecular, culture, future

MESH terms: Neonatal Sepsis, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Sepsis, Biomarkers, Early Diagnosis, Microbiological Techniques

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal sepsis is a clinical syndrome characterized by non-specific signs and symptoms caused by invasion by pathogens1,2. Sepsis is deemed culture-proven if confirmed by microbial growth on blood cultures or other sterile bodily fluids. Debate exists over the occurrence of culture-negative sepsis and whether antibiotics should be continued in culture-negative cases3. Sepsis is categorized as early-onset if diagnosed within the first 72 hours of life, which is due to perinatal risk factors, or late-onset if diagnosed after 72 hours and secondary to nosocomial risk factors. Neonatal sepsis is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality despite advances in neonatal medicine4. Incidence varies from 1–4 cases per 1000 live births in high-income countries but as high as 49–170 cases in low and middle-income countries with case fatality rate up to 24%5–8. Survivors of neonatal sepsis are at increased risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes including cerebral palsy, hearing loss, visual impairment and cognitive delays even in those whose cultures were negative but were treated with antibiotics9,10.

The diagnosis of confirmed sepsis relies on conventional microbiologic culture techniques, which can be time-consuming11. Despite the high sensitivity in detecting low bacterial loads (1–4 CFU/mL), many providers view negative blood cultures with skepticism when presented with a sick infant12. The diagnosis “culture-negative” sepsis or ‘clinical sepsis’ has led to a 10-fold increase in antibiotic use in neonates with evidence of unintended harm including increased risk for necrotizing enterocolitis, fungal infections, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and death12.

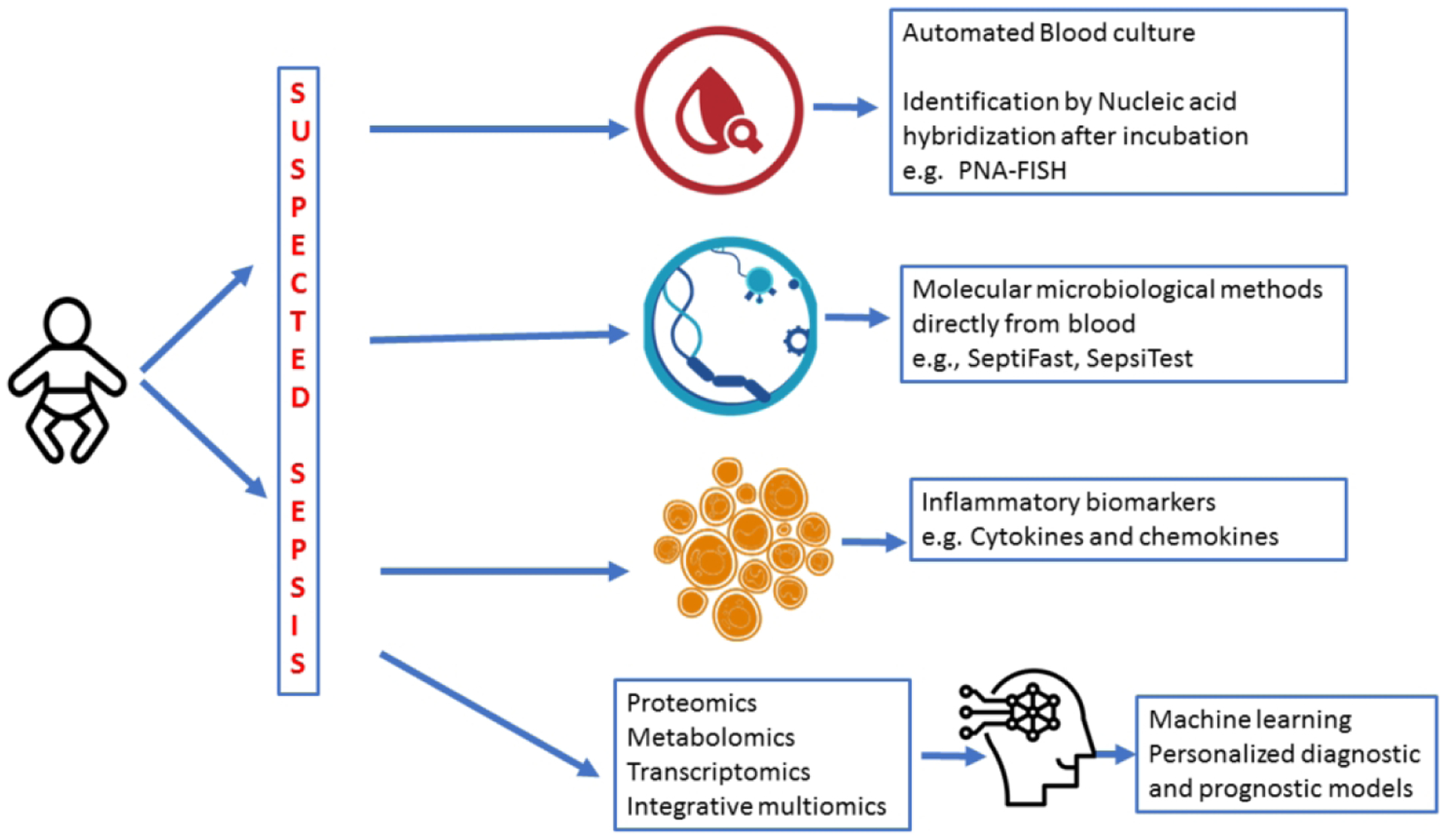

Advances in rapid culture techniques, antibiotic stewardship, and bundled approaches to prevent central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) have reduced morbidity and mortality from neonatal sepsis13,14. Newer molecular approaches and nonculture-based methods to assist in timely detection and accurate diagnosis of sepsis are needed. Current biomarkers and adjunct hematological indices used in routine clinical practice have limited value and are difficult to interpret due to low sensitivity and changing normal ranges during the neonatal period15,16. An ideal marker should have sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) approaching 100%; specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) over 85%17,18. None of the biomarkers or combination of biomarkers have adequate diagnostic accuracy to be used reliably in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis19. We aim to review the past and current diagnostic modalities and present some insight on future diagnostic strategies in neonatal sepsis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Schematic on the categories of diagnostic tests available for neonatal sepsis.

Traditional methods of blood cultures have changed to automated blood culture monitoring for bacterial growth by CO2 detection. Newer tests involve rapidly identifying organisms from positive cultures by fluorescent in situ hybridization techniques. Molecular microbiological diagnostics using PCR for bacterial and fungal genes can be applied directly to blood specimens. Inflammatory biomarkers including CRP, procalcitonin and cytokines are another category of adjunctive diagnostic tests. Multiomic technology enables us to scour genome wide gene expression, protein and metabolites for developing diagnostic tests and prognostic models.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NEONATAL SEPSIS

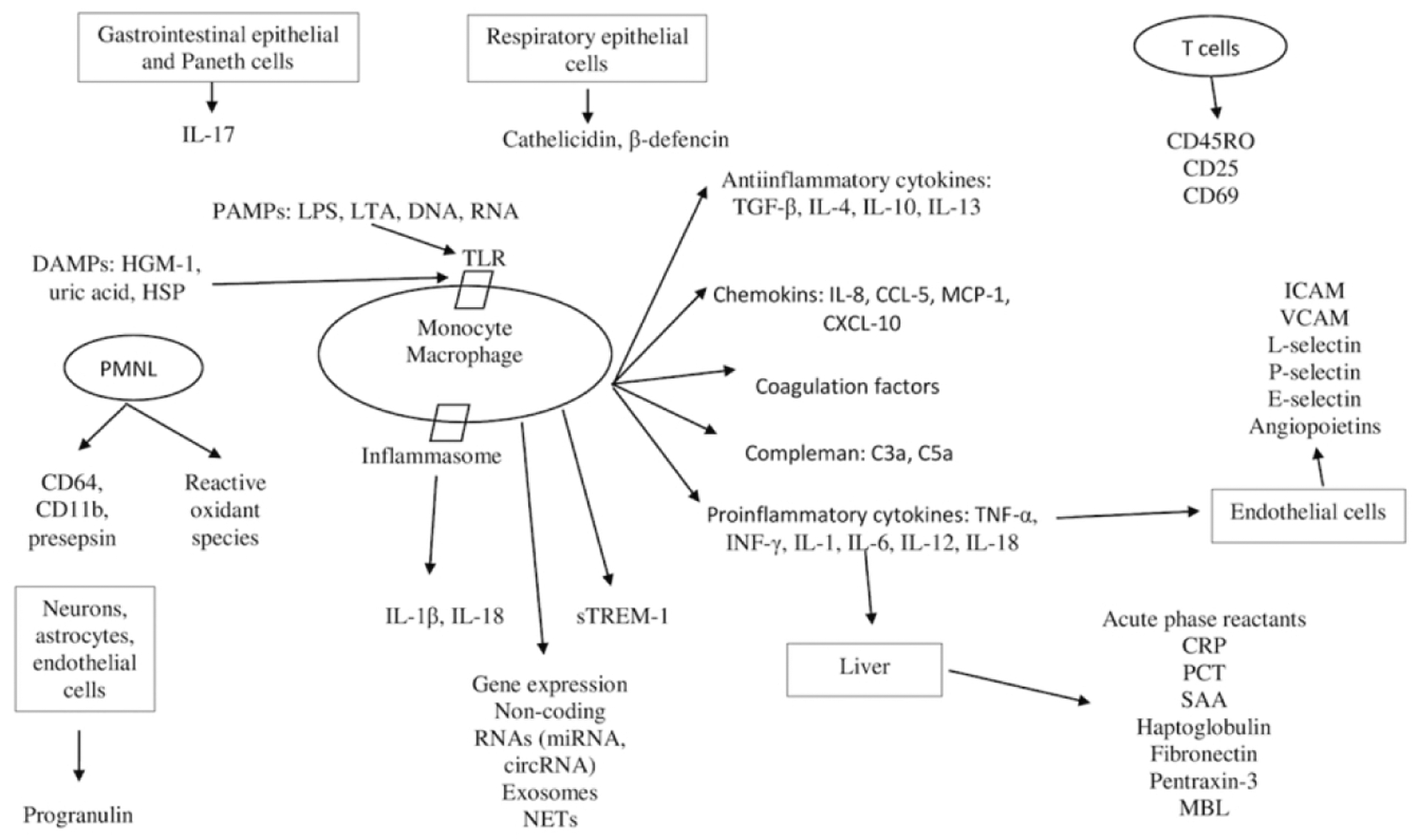

Host immune responses including cytokines and chemokines during neonatal sepsis may aid in the diagnosis and/or assessing the severity of sepsis. A summary of the biomarkers associated with host immune pathways that change during sepsis is depicted in Figure 2. Paneth cells and intestinal lymphoid cells produce interleukin-17 (IL-17), which has a role in local defense and development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome20. Respiratory epithelia secrete antimicrobial proteins and peptides including cathelicidin and β-defensins21. Gram positive microorganisms and their cell wall lipoteichoic acid signal through TLR-2 receptors while gram negative microorganisms and their secreted lipopolysaccharide (LPS) signal through TLR-4 receptors22. These signaling cascades are associated with production of nuclear factor κB (NFκB) dependent inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. NOD-like receptors lead to production of IL-1β and IL-18 by a protein complex called inflammasome23. Activation of pathogen recognition receptors (PRR) results in generation of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-18, interferon-γ (INF-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)24. Proinflammatory cytokines activate endothelial cells leading to increased expression of cell adhesion molecules such as soluble intercellular adhesion molecules, selectins, angiopoietins, CD11b, CD1825. Chemokines including CXCL10, CCL5 (RANTES), CCL3 and complement proteins such as, C3a, C5a cathelicidin and defensins are also stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines26. Damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs, alarmins) such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1), uric acid are released from damaged cells and induce cytokine production, coagulation cascade and regulate polymorphonuclear cell function27. Anti-inflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-4, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13) are expressed to control and balance inflammation28. Acute phase reactants (APRs) such as C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), serum amyloid A (SAA) are produced predominantly in the liver in response to complement activation, PAMPs activity and proinflammatory cytokine secretion.

Figure 2. The relationship between host immunity and biomarkers.

CD, cluster of differentiation; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; RNA, ribonucleic acid; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DAMPs, damage associated molecular patterns; HGM-1, high mobility group box 1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide,; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; TLR, toll-like receptor; HSP, Heat shock protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; INF-γ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; CXCL-10, chemokine ligand-10

CURRENT METHODS TO DIAGNOSE NEONATAL SEPSIS

1. Microbiological culture methods

Conventional culture techniques remain the “gold standard” to confirm the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. The introduction of automated systems that detect the presence of growth from bacterial CO2 production has reduced the time to organism detection to 24–48h29,30. Factors that may influence the recovery of pathogens from the blood include amount of blood volume obtained, timing of collection, and number of samples collected.

In neonates, the presence of low or intermittent bacteremia and maternal intrapartum antimicrobial exposure may decrease sensitivity of blood cultures12,31. The delay in pathogen identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing increases exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, which may lead to bacterial antibiotic resistance and delay in targeted antimicrobial therapy9,32,33. The volume of blood sampled for cultures is the single most important factor influencing the recovery of pathogens from blood cultures34. However, collection of optimal blood volume can be difficult in extremely preterm infants and repeated phlebotomy may increase the risk of requiring blood transfusions. Schleonka et al reported that a blood culture volume of 1mL injected into pediatric blood culture bottles had excellent sensitivity even if organisms were present at very low concentrations (< 4 colony forming units (CFU)/mL)31.

The need for obtaining anaerobic cultures in neonates before commencing antibiotics is unclear35. The overall incidence of clinically significant anaerobic isolates found in a neonatal population was 0.2% of all blood cultures performed36. Previous studies showed that use of anaerobic blood cultures led to increased identification of both aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria37. Créixems et al reported that among 10,024 paired blood cultures (aerobic and anaerobic), 19% of patients with bacteremia would have been missed if aerobic cultures alone were used, not including the 3 strictly anaerobic infections identified38. In contrast, Dunne et al found increased sensitivity in isolating aerobic and facultative anaerobic isolates from pediatric patients when 2 aerobic blood cultures were performed versus paired aerobic/anaerobic cultures39. It is unclear whether treating anaerobes in routine sepsis management in neonates improves clinical outcomes.

2. Rapid testing methods from positive blood cultures

Several diagnostic systems have been developed for rapid identification of organisms found in positive blood cultures and provide faster turn-around times when compared to conventional methods (Table 2)40. These FDA-cleared assays rapidly identify organisms growing in positive blood cultures but do not eliminate the time required for growth from these cultures. Peptide Nucleic Acid Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization Molecular Stains (PNA-FISH)41 is a well-validated method; the new QuickFISH system has reduced turnaround time to 20 minutes, enabling species identification results to be reported in the same time frame as Gram staining42. PCR-based methods, including GeneXpert (1 hour), FilmArray (1 hour), and Verigene (2.5 hours), are somewhat slower than QuickFISH but have little or no sample processing and include selected antibiotic resistance genes40. Rapid assays are gradually becoming less labor intensive and has led to improved clinical outcomes, shorter hospital stays, and dramatically lower healthcare costs43,44.

Table 2-.

Microbial identification from blood cultures and molecular non-culture techniques

| Technique | Target Pathogen | Resistance Typing | Turnaround time | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture based Technique | |||||

| Blood culture | All culturable microbes | Yes | 48–72 hours | - | - |

| Automated identification | All culturable microbes | Yes | 24–48 hours | - | - |

| Nucleic Acid-Based Identification | |||||

| PNA-FISH | Differentiates between Staphylococcus aureus and CoNS; Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus species; Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; and Candida species. | No | 1.5–3 hoursa | 96% – 100% | 96% – 100% |

| QuickFISH | S. aureus, CoNS, E. faecalis, other Enterococci, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa | No | <30 mina | 96% – 100% | 96% – 100% |

| MALDI-TOF | GP and GN bacteria, yeast, fungi, filamentous fungi, mycobacteria | In development | 10–30 mina | - | - |

| Gene Xpert MRSA/SA | S. aureus | mecA for methicillin resistance | <1 houra | 98.3% – 100% for MSSA and MRSA | 98.6% – 99.4% for MSSA and MRSA |

| Verigene gram-positive | Staphylococcus spp., S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. lugdunensis, Streptococcus spp., S.pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. anginosus group, S. pneumoniae, E. faecalis, E. faecium, and Listeria spp. | mecA for methicillin resistance and vanA/B genes for vancomycin resistance | 2.5 hoursa | 92.6% – 100% | 95.4% – 100% |

| Verigene gram-negative | 9 bacterial targets including E. coli, Shigela spp., K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, P. aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, Acinetobacter spp., Proteus spp., Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp. | KPC, NDM, CTX-M, VIM, IMP, OXA | 2 hoursa | 97.1% | 99.5% |

| FilmArray | 27 targets, including staphylococci, streptococci, Enterococcus, Listeria, Acinetobacter, Neisseria meningitidis, P. aeruginosa and members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, as well as Candida spp. | mecA, vanA/B, and K. pneumonia carbapenemase (KPC) genes | 1 houra | >90% | - |

| Culture-Independent Diagnostic Tests | |||||

| SeptiFast | 25 pathogens, (10 GN, 9 GP, 6 fungi) | - | 4–6 hours | 63–83% | 83–95% |

| SepsiTest | >345 pathogens, 13 fungi | - | 8–12 hours | 11–87% | 83–96% |

| T2 MR Candida | C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis | In development | 3–6 hours | 90% | 98% |

Turn-around times are after culture turns positive.

CONS-coagulase-negative staphylococci, GP- gram positive, GN- gram negative

Recent advances in molecular techniques enable amplification of microbial pathogens directly from whole blood samples in under 12 h without relying on initial microbial growth in blood cultures (Table 2)40. This provides the advantage of same-day identification and early targeted pathogen-specific antimicrobial therapy, especially in settings where there is pretreatment with antibiotics, low-density bacteremia, or where culture-negative sepsis is common. These molecular techniques predominantly rely on the amplification methods of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the bacterial 16S or 23S rRNA genes and the 18S rRNA gene of fungi. Diagnostic accuracy of systems such as SeptiFast, SepsiTest, and, most recently, detection of PCR amplified pathogen DNA from blood that is hybridized to capture probe-decorated nanoparticles detectable by a small portable T2 Magnetic Resonance (MR) platform have been reported45,46–48. The Roche Light Cycler SeptiFast system requires 100 μL blood and can detect 25 pathogens known to cause >90% of bloodstream infections, with a turnaround time of 6 hours. A competing commercial assay, SepsiTest is able to detect >300 pathogens, however, with a relatively slower turnaround time of 8–12 hours46. The T2 MR is an automated nanoparticle-based PCR assay that can detect as few as 1 CFU/mL of Candida spp. in the blood in approximately 3 hours46.

Some studies report a discordance between conventional culture and PCR methods during validation of molecular pathogen detection methods, which has led to continued uncertainty about the bacterial etiology of sepsis49,50. Furthermore, false positive results were seen with high cycle thresholds thus opening the possibility for nonspecific amplification and raising the questions about whether the bacteria present was the cause for the sepsis syndrome51. A systematic review concluded that molecular diagnostics had value as adjunctive tests with an overall sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96%52. Molecular assays are not readily available, may be expensive and have modest diagnostic accuracy. Hence, molecular assays are not ready to replace blood cultures as reference standards but are useful as adjunctive tests in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis.

3. Hematological Indices

Leukocyte (<5000 or ≥20000/mm3), absolute neutrophil (<1000 or ≥5000/mm3) and immature/total neutrophil counts (>0.2), and peripheral blood smear (toxic granulation, vacuolization and Dohle bodies) are traditionally used to aid the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis53.

White blood cell count (WBC)

Leukocyte count starts between 6000 and 30000/mm3 in the first day of life and decreases to 5000–20000 mm3 later. Neutrophil count tends to be lower at lower gestational ages (GA) and peaks 6–8 h after birth54. Clinical conditions such as maternal fever and hypertension, perinatal asphyxia, meconium aspiration syndrome, delivery route, intraventricular hemorrhage, hemolysis, pneumothorax, convulsion and even crying affects neutrophil count55. A literature review by Sharma et al reported that leucopenia (WBC count <5000/mm3) has a low sensitivity (29%) but high specificity (91%) for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis56. Additional studies highlighted that leucopenia is more predictive of sepsis than leukocytosis (WBCs > 20,000/mm3) at more than 4 h57. Neutrophil/lymphocyte (NLR) of 1.24 to 6.76 and platelet/lymphocyte (PLR) ratios of 57.7 to 94.05 may be diagnostic of neonatal sepsis58,59.

Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC)

Neutrophil counts are commonly evaluated in neonates with presumed sepsis but can be affected by maternal and infant risk factors54,55. Neutropenia (ANC <1,000/mm3 at ≥4 h) is considered more specific for early onset neonatal sepsis as opposed to neutrophilia (ANC ≥10,000/mm3)51,56,60. Interpretation of ANC, however, must take into consideration the neonate’s gestational and postnatal age as the lower limit of ANC decreases with lower GA. Furthermore, an analysis of 30,354 CBCs obtained in the first 72 h of life demonstrated that ANC peak later in early preterm neonates <28 weeks’ gestation as compared with neonates ≥28 weeks’ gestation (24 h of life vs 6–8 h, respectively)54. Mean neutrophil volume >157 arbitrary units had sensitivity and specificity as 79% and 82% while sensitivity and specificity of CRP were 72% and 99%, respectively61. In 141 neonates with neonatal sepsis, cut-off level of delta neutrophil index (DNI) was calculated as 4.6 with 85% sensitivity and 80% while CRP had 81% sensitivity and 82% specificity62.

Immature to Total Neutrophil (I:T) Ratio

Compared to other hematological markers, I:T ratio may be the most sensitive indicator of neonatal sepsis60, but this parameter also varies with GA and postnatal age. In healthy newborns, the I:T ratio peaks at 0.16 during the first 24 h and gradually declines over days. Gandhi et al., propose that I:T ratio > 0.27 in term newborns and > 0.22 in preterm neonates favor the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis60. Murphy et al. demonstrated that two normal I:T ratios correlated with a sterile blood culture had a maximum NPV of 100%63.

Red cell distribution width

Red cell distribution (RDW) width shows increased red blood cell production in inflammatory and infectious diseases. Elevated RDW has been shown to be associated with increased mortality from sepsis in both adult and neonates64,65. In neonates, RDW was significantly higher in sepsis and among non-survivors66. Cut-off levels as 16.3 and 19.5 had sensitivity (70–87%) and specificity (66.1–81%) in neonatal sepsis and gram-negative LOS, respectively64,67.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is associated with neonatal sepsis68. Platelet volume increases while being more active and associated with cytokines and inflammatory mediators. A meta-analysis that included 11 studies and 932 patients, reported that MPV was higher in neonatal sepsis with a cut-off level between 8.6–11.469–71.

4. Inflammatory Biomarkers

Acute phase reactants

Acute phase reactants are produced by the liver in response to cytokines, which are induced by infection and tissue injury. TNFα, CRP, PCT, fibronectin, haptoglobin, pro-adrenomedullin (pro-ADM) and SAA have been evaluated in neonatal sepsis.

a. C-reactive Protein

C-reactive protein (CRP) has been the most studied biomarker16. Serum CRP concentrations rise within 10 to 12 hours in response to bacterial infections and peak after 36–48 hours, with concentrations that correlate with illness severity72. Due to the delay in elevation, it is unreliable for early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis (low sensitivity)15. Furthermore, other non-infectious maternal and neonatal conditions may also result in elevated CRP levels, thus making it a nonspecific biomarker72,73. A systematic review of biomarkers for neonatal sepsis concluded that serial measurements of CRP at 24 to 48 hours after onset of symptoms has been shown to increase its sensitivity and negative predictive value and may be useful for monitoring response to treatment in infected neonates receiving antibiotics16. This suggests that CRP may be more useful for ruling out infection and discontinuing antibiotics when serial measurements are obtained.

Procalcitonin

Procalcitonin is synthesized in monocytes and hepatocytes as a prohormone of calcitonin in response to cytokine stimulation. After birth, it increases until postnatal day 2–474. PCT is downregulated by interferon-γ, a commonly produced cytokine in viral infections72,75,76. Thus, PCT has emerged as a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of bacterial infections that may be useful in discriminating between bacterial and viral etiologies. After exposure to bacterial endotoxin, PCT levels rapidly rise within 2–4 hours and peak within 6–8 hours, thus making it a more sensitive marker than CRP for early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis77. This increase often correlates with the severity of the disease and mortality. However, in early onset neonatal sepsis, PCT measurements at birth may initially be normal; a serial PCT measurement at 24 h of age may be more helpful for early diagnosis78. Furthermore, serial PCT determinations allow to shorten the duration of antibiotic therapy in term and near-term infants with suspected early-onset sepsis79. However, before this PCT-guided strategy can be recommended, its safety and reliability must be confirmed in a larger cohort of neonates.

In a meta-analysis with 1959 patients, sensitivity and specificity of PCT were reported to be 81% (95%CI: 74–87%) and 79% (95% CI: 69–87%), respectively80. Studies in the meta-analysis used different cut-off thresholds (0.8–2.4 μg/L). Positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLR and NLR) were 7.7 and 0.11 for LOS while 3.2 and 0.3 for EOS indicating that diagnostic accuracy is better in LOS81. Cord blood PCT >0.7 μg/L in the diagnosis of sepsis showed 69% sensitivity and 70% specificity and PCT has been used in combination with other biomarkers in EOS82. Canpolat et al. reported that PCT (>1.74 ng/ml) and CRP (>0.72 mg/dL) had 76% and 58% sensitivity and 58% and 85% specificity respectively on the 3rd day of life in neonates with preterm premature rupture of membranes83. Eschborn et al. evaluated 29 studies comparing PCT with CRP and found that mean sensitivity for EOS, LOS and EOS+LOS was 73.6%, 88.9% and 76.5% for PCT; 65.6%, 77.4% and 66.4% for CRP while mean specificity for EOS, LOS and EOS+LOS was 82.8%, 75.6% and 80.4% for PCT; 82.7%, 81.7% and 91.3% for CRP, respectively72. Authors concluded that performance of both biomarkers will be better with serial measurements, and correlation with clinical findings is needed for decision making.

Serum Amyloid A

Serum Amyloid A (SAA) is another acute phase reactant synthesized by hepatocytes, monocytes, endothelial and smooth muscle cells in 8–24 h after bacterial exposure and is regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. SAA levels increase with age, with the lowest levels seen in umbilical cord blood and highest levels seen in the old age84. In response to infection or injury, SAA levels rapidly increase up to 1000 times higher than baseline but can be significantly influenced by the patient’s hepatic function and nutritional status85. In a study by Arnon et al, when compared with healthy infants at 0, 8, and 24 hours, SAA levels in septic infants were significantly higher (p < .01) at all time points53. When compared with CRP, SAA had an overall better diagnostic accuracy for predicting EOS. Cetinkaya et al. also determined that SAA concentrations had better sensitivity and area under the curve when compared with CRP and PCT, though the difference was not statistically significant86. Different cut-off points between 1–68 mg/L were reported with a pooled 78% sensitivity and 92% specificity87.

Proadrenomedullin is a stable precursor of ADM, which modulates circulation, has antimicrobial properties and protects against organ damage88. High sensitivity (86.8%), specificity (100%), PPV (100%) and NPV (83.9%) with a cut-off value 3.9 nmol/L of pro-ADM were observed in 76 neonates with neonatal sepsis89. Higher pro-ADM levels were associated with increased sepsis severity and mortality90.

Adipokines are released from adipose tissue and may initiate secretion of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Visfatin (>10 ng/mL) and resistin (>8 ng/mL) had sensitivity and specificity over 90% in 62 septic neonates91. Subsequent studies reported lower sensitivity and specificity for resistin, but levels were positively correlated with IL-6 and CRP92,93. Hepcidin, progranulin, stromal cell-derived factor 1, endocan and pentraxin-3 are less studied APRs which have a role in inflammation, chemoattraction, complement activation, angiogenesis and future studies are needed to evaluate diagnostic accuracy of these markers94–98

Vascular Endothelium

Vascular endothelium interacts with leukocytes, soluble mediators, PAMPs and DAMPs, which have a role in sepsis pathogenesis. E-selectin, L-selectin, sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 and angiopoietin 1–2 were studied in diagnosis of neonatal sepsis99. But limitation of these markers includes no normative data in neonates, physiological increase in the first month of life and lack of large studies.

Interleukins

IL-6 increases immediately after exposure to pathogens and normalizes in 24 h100. IL6 has a proinflammatory effect inducing CRP, fibronectin and SAA release from liver, T cell differentiation and B cell maturation101. IL-6 has been studied more than other cytokines and found to be increased in neonates with EOS and LOS, and various cut-off levels between 18 and 300 pg/mL were reported in 31 studies with 1448 septic neonates102. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of IL-6 were 88% and 82% while PLR and NLR were 7.03 and 0.2, respectively. Combination of IL-6 with other markers such as CRP, pro-ADM, PCT showed better diagnostic accuracy19,89,103.

Cortes et al. evaluated diagnostic accuracy of IL-6 and CRP in EOS and LOS104. Authors concluded that IL-6 (>17.75 pg/mL) showed greater accuracy in EOS while CRP (>0.53 mg/dL) was more accurate in LOS. Kurul et al. showed that IL-6 (>580 pg/mL) and PCT (>0.94 ng/mL) were associated with 7-day mortality while CRP was not105.

Ye et al. evaluated utility of cytokines in 420 neonates with neonatal sepsis106. Interleukin-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and INF-γ were measured and compared with CRP. Interleukin-6 (>12.5 pg/mL) and IL-6/IL-10 ratio (>3.5) were found as valuable as CRP while most sensitive and specific ILs were IL-6 (94.1%) and IL-6/IL-10 ratio (100%), respectively. Celik et al. observed that a cut-off level of 202 pg/mL for IL-6 differentiated gram negative (n=73) from gram positive (n=82) sepsis with 68% sensitivity and 58% specificity107. In a later study, IL-6 (>400 pg/mL) alone or combination with TNF-α (>32 pg/mL), IL-8 (>200 pg/mL), G-CSF (>1000 pg/mL) had 100% sensitivity, specificity, NPV and 38 to 69% PPV to differentiate gram negative neonatal sepsis108.

IL-8 is another proinflammatory cytokine promoting chemotaxis and activation of granulocytes and increases within 1–3 h with a half-life <4 h. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated in a meta-analysis with 8 studies, 548 neonates (cut-off levels between 0.65 and 300 pg/mL), which reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 78% and 84% similar to CRP109.

TNF-α is secreted from natural killer cells by IL-2 to induce T cell proliferation, vasodilatation and neutrophil adhesion110. In a systematic review, (where TNF-α cut-off values was ranged from 1.7 to 70 pg/mL) at a mean cut-off value of 18.94 pg/m/L, the sensitivity was 79% and specificity was 81% and better accuracy in LOS than EOS111. Meta-analyses of data from neonates show variable sensitivity and specificity for of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α with only moderate accuracy in diagnosing neonatal sepsis16,109,111. However, when combined with other cytokines or late proinflammatory markers, such as CRP, sensitivity and specificity increase106,112,113. Currently, measuring cytokines for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis may not be practical or cost-effective because enzyme immunoassays are expensive and time consuming.

CELL ADHESION MOLECULES

Leukocyte antigens are upregulated after bacterial exposure and can be quantified by flow cytometry114,115. These markers increase in minutes after infection and levels were not affected by GA, timing of sepsis onset, type of microorganism or non-infectious diseases116,117. Limitation of these markers are need of high technology and non-standardized normal ranges.

Cluster differentiation molecule-64 (CD64) expressed from neutrophils and monocytes facilities phagocytosis and intracellular killing of opsonized microorganisms. Increased levels can be detected in 1 hour and stable for 24 hours. Shi et al. performed a meta-analysis of CD64 levels from 17 studies including 3478 neonates and found that pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 77%, 74%, 3.58 and 0.29, respectively118. Serial measurements and combination with other markers have been reported with varying diagnostic accuracy119,120. Increased CD11b expression was found both in EOS and LOS with high sensitivity and specificity up to 100%112. In a recent meta-analysis including 9 studies with 843 neonates showed that CD11b is a promising biomarker with sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR as 82%, 93%, 11.51 and 0.19, respectively121.

Soluble CD14 fragment (presepsin) is a specific and high affinity receptor complexes of lipopolysaccharides and activates TLR to proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Both meta-analysis revealed that presepsin was as accurate as PCT and CRP in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis77,122.

Gram negative infections lead to higher sCD14 levels123. Cord blood presepsin levels were evaluated in 288 preterm infants with premature rupture of membranes for EOS and a cut-off level ≥1370 pg/mL yielded a odds ratio of 12.6 (95% CL 2.5–28.1)124. Presepsin, PCT, IL-6 and IL-8 were compared in diagnosis of EOS and presepsin was found as the most accurate biomarker with 88.9% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity125.

Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM1) regulates the innate immune system and inflammation by promoting the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Increased levels were found in neonatal sepsis with a cut-off value of 310 pg/mL although higher levels were reported in culture proven sepsis126. Urine sTREM-1 >78.5 pg/mL had 90% sensitivity, 78% specificity, 68% PPV and 94% NPV in 62 neonates with sepsis, respectively127. A meta-analysis including 8 studies with 667 neonates reported that sensitivity and specificity of sTREM-1 were 95% and 87%, respectively128. Limitations include small number of studies and different cut-off levels between 77.5 and 1707 pg/mL128.

The challenge of biomarker identification is reflected by the fact that over 3000 sepsis biomarker studies have been published with almost 200 candidate biomarkers evaluated129. However, there is not a single biomarker that has sufficient diagnostic accuracy for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. Combination of biomarkers or their serial measurements may be strategies to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Combination of IL-6, sTREM-1, and PCT has been suggested, as each biomarker represents a different component in the pathophysiology of sepsis130. Others propose that early- and mid-phase markers such as neutrophil CD64 and procalcitonin should be combined with the late-phase biomarker CRP for maximal diagnostic benefit40. A recent literature review summarizes the utility of combining both early and late biomarkers for neonatal sepsis130.

5. Strategies for the future

Mass spectrometry for identification of pathogens from blood culture specimens

Matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization/time -of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectroscopy is a relatively new approach that can identify microorganisms within 30 min after blood culture positivity131.Meta-analyses have found that use of MALDI-TOF for diagnosis of infection from culture bottles has acceptable sensitivity and specificity132 and with higher sensitivity in gram negative infections compared to gram-positive infections133.

Point-of-care devices for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis

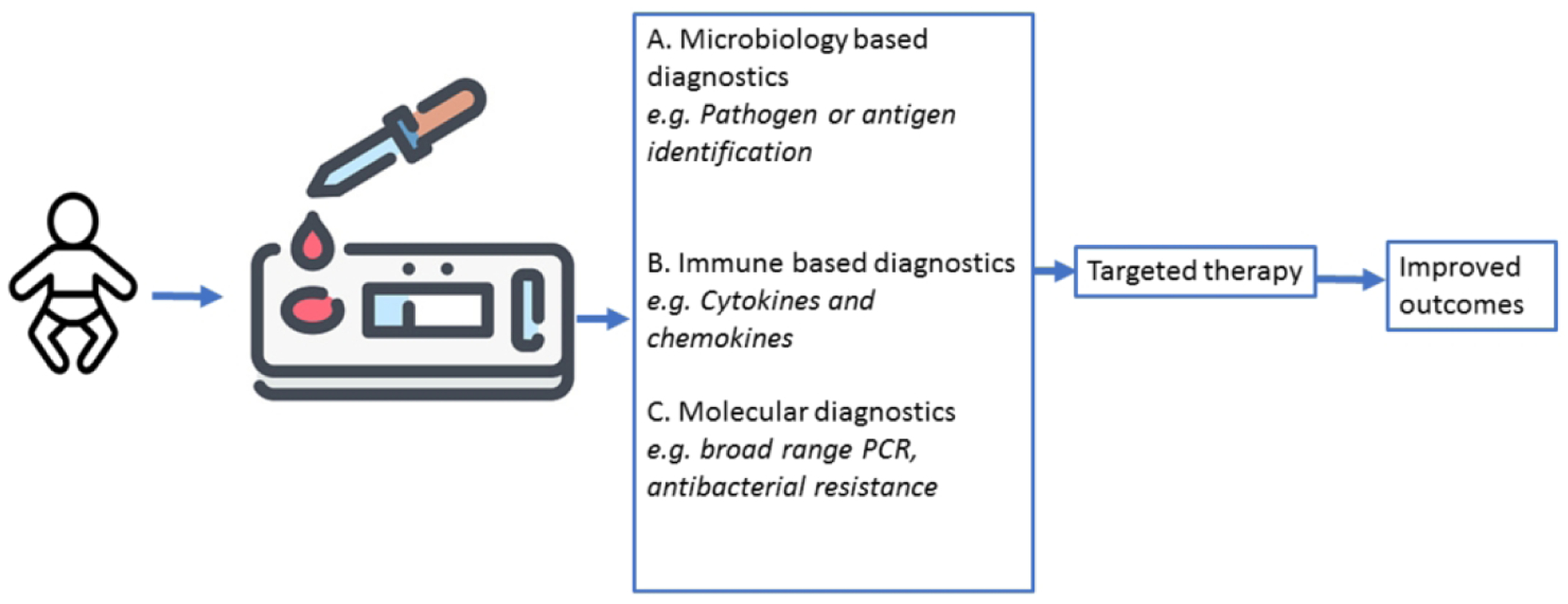

Rapid tests done at the bedside that could confirm diagnosis or provide prognostic information have the potential to improve patient outcomes and decrease healthcare costs (Figure 3). Novel techniques such as analysis of volatile organic compounds in the breath has been demonstrated to be reasonably sensitive and specific134 and capable of distinguishing sepsis from inflammation in rat models135, yet to be validated in human studies. Point-of-care (POC) devices using a variety of biomarkers including blood plasma protein quantification and leukocyte monitoring are being evaluated for the diagnosis of sepsis136.

Figure 3. Point of care testing for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis.

Blood samples are drawn on suspicion of infection on laboratory chips that are microbiology, immune, or molecular based diagnostics. The results enable us to initiate targeted therapy. The rapid results and targeted therapy will improve clinical outcomes.

Omics technologies and personalized medicine

Omics technologies provide data on genome-wide gene expression, protein translation and metabolite production that are differentially regulated in neonatal sepsis137,138. Proteomics measures protein components released after infection or inflammation. Cord blood and amniotic fluid proteomics have provided information regarding the fetal response to intra-amniotic inflammation and have successfully predicted EOS with >92% accuracy139,140. Proteomics including neutrophil defensin 1–2, cathelicidin, S100A12, S100A8, pro-apolipoprotein C2, apolipoprotein A-E-H, β-2 microglobulin, haptoglobin, desarginin from amniotic fluid, cord blood, plasma were found to be valuable in diagnosis of EOS and LOS141–143.

Metabolomics by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMR) and mass spectrometry (GC-MS) has also been investigated in adult sepsis with favorable results144. Urinary metabolomics profile of adult pneumococcal pneumonia, for example, has been found to be distinctly different from viral and other bacterial causes of pneumonia145. This indicates that evaluation of urinary metabolite profiles may be useful for effective diagnosis and lead to faster targeted antibiotic treatment. Urine samples of neonates with sepsis were evaluated with H-NMR and GC-MS showed increase in glucose, maltose, lactate, acetate, ketone bodies, D-serine and also normalization of variations with treatment146.

A prospective observational study comparing genome-wide expression profiles of 17 VLBW infants with bacterial sepsis identified distinct clusters of gene expression patterns in gram-positive and gram-negative sepsis when compared with controls147. Genomic analysis may determine sepsis risk, treatment response and prognosis while evaluating gene variants responsible for PRPs, signaling molecules and cytokines143,148.

Machine Learning

Machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly used to sort transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic data for biomarker screening, developing prognostication models and for identifying the right patients for specific therapies (personalized medicine). One example is the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE), which was developed and validated as a prognostic enrichment tool for pediatric septic shock and in predicting mortality138,149. Ongoing research is investigating the application of the PERSEVERE model in neonatal sepsis prognostication150.

Reduced heart rate variability and transient decelerations were detected in hours to days before diagnosis of sepsis151,152. In these studies, early diagnosis of sepsis and reduced mortality has been reported. Recently predictive models using machine learning were developed. These models use the vital signs, clinical and laboratory features of patients. Mithal et al. calculated a triggering score ≥5 by using heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, desaturation and bradycardia events. Authors found that LOS was diagnosed 43.1±79 h before culture positivity with 81% sensitivity, 80% specificity, 57% PPV and 93% NPV in 72 patients153. Clinical findings such as birth weight, gender, catheter use and laboratory findings such as blood gas parameters, CBC were also integrated into prediction models and found valuable in diagnosis of sepsis154,155.

New Genetic Techniques

Non-coding RNAs (transcriptomics) including microRNAs (miRNA), circular RNAs (circRNAs) regulate many cell signaling pathways including cell proliferation, differentiation, development, metabolism, apoptosis and proinflammatory cytokine production156. Both increased (miRNA 15-16a-23b-451) and decreased (miRNA 25-129-132-181a-223) expression were reported while 80–89% sensitivity and 79–98% specificity were found in diagnosis of neonatal sepsis157,158. Exosomes and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) released during inflammation may be therapeutic targets in the future.

Conclusions

Identification of an ideal biomarker to diagnose neonatal sepsis is still the holy grail but advances in technology have given us a glimpse of the promising tests for the future. Inflammatory markers such as CRP and PCT as well as other hematological indices used currently have limited value in neonates. Serial measurements of an ideal combination of biomarkers have shown to increase diagnostic accuracy but remain expensive and cumbersome for clinical practice. Molecular diagnostic tools such as PCR and sequencing, and mass spectrometry offer promise for more rapid and sensitive detection of disease. Omics technology and machine learning may provide us diagnostic and prognostic models that could be personalized for the future.

Table 1.

Most studied and promising biomarkers in diagnosis of neonatal sepsis

| Biomarker | Patient characteristics | Performance | Comments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | PLR | NLR | ||||

| Complete blood cell count51 | ||||||||||

| WBC | EOS LOS |

- | 0.3–18 0.1–23 |

79–99 80–99 |

36 13–100 |

94->99.8 74–96 |

- | - | Leukocyte (<5000, ≥20000) and absolute neutrophil count (<1000, ≥5000) were traditionally used parameters. But these parameters are affected by gestational age, postnatal hours and days and clinical conditions such as maternal hypertension, perinatal asphyxia, intraventricula hemorrhage, etc. | |

| ANC | EOS LOS |

- | 8–68 | 95–99 | 14–21 | 74–96 | - | - | ||

| I/T ratio | EOS LOS |

22–62 33–54 |

74–96 62–100 |

2.5 12–100 |

99 66–96 |

- | - | The I/T ratio has better sensitivity than WBC and ANC. Disadvantage of this ratio is the interreader difference. The ratio >0.2 has been traditionally used. | ||

| Platelet count | EOS LOS |

0.8–4 8–48 |

97–99 89–98 |

13–14 99 |

- 94 |

- | - | Low platelet count can be found in neonatal sepsis, especially gram negative and fungal sepsis but often remain decreased during sepsis process. | ||

| MNV, MNC, MNS | 76 proven, 126 clinical sepsis, 98 control All gestations (mean 30±5 w), early and late onset sepsis61 |

>157 au <159 au <127.5 au |

79 66 60 |

82 64 65 |

90 80 21 |

65 47 55 |

- | - | No statistical difference between early and late onset sepsis; proven and clinical sepsis. Combination with IL-6 and CRP gave better diagnostic performance. Levels normalized with treatment. | |

| DNI | 110 proven, 31 clinical sepsis, 87 control All gestations (median 30 (23–41) w), early and late onset sepsis62 |

4.6 | 85 | 80 | 87 | 77 | - | - | DNI was insignificantly higher in late onset sepsis. Proven sepsis had significantly higher DNI levels. Levels normalized with treatment. Mortality was predicted with DNI. | |

| CD64 | Meta-analysis of 17 studies including 3478 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis118 | 1.8–4.3 CD64 index; 1010–6010 $ | 21–100 | 59–100 | 9–96.2 | 73–100 | 1.84–47.1 | 0.06–0.48 | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 77%, 74%, 3.58 and 0.29, respectively. The pooled DOR was 15.18 (95 % CI: 9.75–23.62). Proven sepsis group had better diagnostic performance than clinical sepsis group. Term infants had higher sensitivity, specificity, PLR and DOR. | |

| CD11b | Meta-analysis of 9 sudies including 843 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis121 | 12.6–600 MFI | 65–100 | 56–100 | 50–100 | 61–100 | 2.1–156 | 0.01–0.49 | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 82%, 93%, 11.51 and 0.19, respectively. The pooled DOR was 59.50 (95% CI 4.65 to 761.58). The diagnostic accuracy of was higher in early-onset sepsis. | |

| Presepsin | Meta-analysis of 11 studies including 793 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis122 | ≤ 650 650–850 ≥ 850 |

91 91 90 |

85 97 86 |

- | - | - | - | The pooled DOR: 71.78 (7.46–690.56) 542.72 (156.62–1880.60) 75.60 (8.32–686.53) |

|

| Meta-analysis of 28 sudies including 2661 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis77 | 67–98 | 75–100 | - | - | - | - | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 85%, 98%, 50.8 and 0.06, respectively. The pooled DOR was 864. | |||

| sTREM-1 | Meta-analysis of 8 studies including 667 neonates, all gestations but mostly term infants, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis128 | 77.5–1707.35 pg/mL | 70–100 | 48–100 | 34–93.3 | 62–90 | 1.6–9.33 | 0.07–0.48 | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 95%, 87%, 7 and 0.05, respectively. The pooled DOR was 132.49 (95% CI 6.85–2560.70). | |

| IL-6 | Meta-analysis of 31 studies including 1448 septic neonates101 | 3.6–300 pg/mL | 54–100 | 45–100 | - | - | 1.63–88.79 | 0.03–0.50 | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 88%, 82%, 7.03 and 0.2, respectively. The pooled DOR was 29.54 (95%CI:18.56–47.04) | |

| IL-8 | Meta-analysis of 8 studies including 548 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis108 | 0.65–100 pg/mL | 34–94 | 66–100 | 64–100 | 59–95 | 2.22–80.49 | 006–0.76 | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 78%, 84%, 4.58 and 0.25, respectively. The pooled DOR was 21.64 (95% CI: 7.37 to 63.54). | |

| TNF-α | Meta-analysis of 15 studies including 1201 neonates111 | 0.18–180 (20000 in 2 studies) | 21–100 | 43–100 | - | - | - | - | Pooled sensitivity, specificity were 66%, 76%, , respectively. The pooled DOR was 7.43 (95%CI 3.47–15.90). Diagnostic accuracy was found slightly better in LOS than EOS. | |

| CRP | Review of 27 studies including 4996 neonates112 | 2.5–100 mg/L | 22–100 | 59–100 | 31–100 | 38–96 | - | - | ||

| PCT | Meta-analysis of 16 studies including 1959 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis80 | 0.5–5.75 μg/L | 57–100 | 50–100 | 19–100 | 56–100 | - | - | Pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR were 81%, 79%, 3.9 and 0.24, respectively. The pooled DOR was 16 (95% CI 8–32). Diagnostic accuracy was better in LOS than EOS. | |

| SAA | Meta-analysis of 9 studies including 823 neonates, all gestations, EOS and/or LOS, proven and/or clinical sepsis87 | 1–68 mg/L | 23–100 | 33–100 | 57–100 | 57–100 | - | - | Pooled sensitivity, specificity were 84%, 89%, respectively. The pooled DOR was 91.84 (95% CI, 16.78–502.80). CRP has higher pooled sensitivity and DOR than SAA. | |

| Pro-ADM | 31 proven, 41 clinical sepsis and 52 control, preterm and term infants, EOS and/or LOS89 | 3.9 nmol/L | 86 | 100 | 100 | 83 | - | - | Diagnostic accuracy of pro-ADM was similar with IL-6 and CRP. Higher pro-ADM levels was found in gram negative sepsis. | |

| Hepcidin | 27 neonates with LOS and 17 control, VLBW infants94 | 92.2 mg/dL | 76 | 100 | 100 | 87 | - | - | Diagnostic performance was better than CRP and combination with CRP did not give better performance than hepcidin alone | |

| Progranulin | 2 studies: Neonates >34 w at risk of EOS, proven and clinical sepsis (n:152), (n:121)95 | 1.39–37.86 ng/ml | 67–94 | 80–51 | 76–61 | 67–91 | 3.4–1.95 | 0.16–0.11 | Progranulin was found efficient to predict EOS. Combination with CRP, PCT, IL-6 gave better diagnostic performance. | |

| Vascular endothelium | 74 infected, 118 non-infected samples of 149 neonates, preterm and term infants with EOS or LOS99 | sICAM-1 sE-Selectin SAA | 228 ng/mL 132 mg/L 1 mg/L |

76 54 23 |

75 82 92 |

66 66 66 |

83 73 66 |

- | - | LOS group had higher sICAM-1 and SAA while lower sE- Selectin levels. Combination of these biomarkers with hsCRP alltogether gave sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV as 90%, 67%, 64% and 91%, respectively. |

| Molecular assays (Meta-analysis52) | All molecular tests (35 studies) Broad range PCR (9 studies) Real-time PCR (9 studies) Post-PCR processing (5 studies) Multiplex PCR (6 studies) LOS (10 studies) EOS and LOS (23 studies) Preterm (5 studies) Preterm and term (30 studies) |

90 (38–100) 97 86 97 76 79 94 89 90 |

93 (32–100) 93 94 96 81 84 92 87 94 |

- | - | - | - | Molecular tests have the advantage of rapid results and can be used as add-on tests. Molecular assays, including PCR and hybridization methods and have rapid detection times compared to blood cultures (6–8 h vs 20–36 h). Costs, availability of equipment and need for technical skills are disadvantages. | ||

| Future | ||||||||||

| Omics approach | Metabolomics: sugars, lipids, small peptides, vitamins including glucose, maltase, lactate, acetate, ketone bodies, D-serine, acylcarnitines, acetoacetate, creatine146 | |||||||||

| Proteomics: neutrophil defensin 1–2, cathelicidin, S100A12, S100A8, proapolipoprotein C2, apolipoprotein A-E-H, β-2 microglobulin, haptoglobin, desarginin141, 142 | ||||||||||

| Nanotechnology | Magnetic, gold, fluorescent and lipid based nanoparticles for contrast agents and biosensors45,46 | |||||||||

| Machine learning | ||||||||||

| Heart rate variability | Reduced heart rate variability and transient deceleratons were associated with early diagnosis of sepsis in 633 neonates152 while reduced mortality due to different clinical problems including sepsis was reported in 2989 VLBW infants151 | |||||||||

| Vital signs | Heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, desaturations, bradycardias of 155 neonates between 23–32 w with LOS153 | Triggering score ≥5 | 81 | 80 | 57 | 93 | - | - | LOS was diagnosed 43.1±79 h before culture positivity | |

| Clinical findings | Fever, apneas, platelet counts, gender, bradypnea, band cells, catheter use, birth weight and maternal age, cervicovaginitis in 238 neonates154 | - | 93 | 80 | 82 | 92 | - | - | 25 potential maternal and neonatal features were studied. Predictive model was created with combination of clinical, laboratory and demographic features. | |

| Blood pressure, temperature and saturation wer found vital candidate markers out of heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure,diastolic blood pressure in 7870 neonates155 | ||||||||||

| New genetic techniques | Non-coding RNA’s: miRNA, circRNA, | miRNA-181a157 miRNA-16a158 miRNA-451158 |

0.625 3.1 1.2 |

83 88 64 |

84 98 60 |

- 95 61 |

- 88 62 |

- | - | Study groups included term infants, both EOS and LOS, proven and clinical sepsis. miRNA levels were correlated with WBC, CRP and respiratory discomfort. |

WBC, White blood cell count; EOS, early onset neonatal sepsis; LOS; late onset neonatal sepsis; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; I/T ratio, immature/total neutrophil count ratio; MNV, mean neutrophil volume; MNC, mean neutrophil conductivity; MNS, mean neutrophil scatter; DNI, delta neutrophil index; CD, cluster of diferentiation; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; IL, interlukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; SAA, serum amyloid A; pro-ADM, proadrenomedullin; sICAM-1, Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; sE-Selectin, Soluble endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule-1; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; VLBW, very low birth weight infants; RNA, ribonucleic acid; miRNA, micro RNA; circRNA, circular RNA; NET, neutrophil extracellular traps; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; $ cAntibody-phycoerythrin molecules bound per cell; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity

Impact.

Reviews the clinical relevance of currently available diagnostic tests for sepsis

Summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of novel biomarkers for neonatal sepsis

Outlines future strategies including the use of omics technology, personalized medicine and point of care tests.

Statement of financial support.

MP is funded by NIH grants, R03HD098482 and R21HD091718 not related to this review and funders had no role in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: No conflicts of interest or other disclosures

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim F, Polin RA & Hooven TA Neonatal Sepsis. Bmj 371, m3672 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shane AL, Sánchez PJ & Stoll BJ Neonatal Sepsis. Lancet 390, 1770–1780 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantey JB & Baird SD Ending the Culture of Culture-Negative Sepsis in the Neonatal Icu. Pediatrics 140 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaidi AK et al. Effect of Case Management on Neonatal Mortality Due to Sepsis and Pneumonia. BMC Public Health 11 Suppl 3, S13 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoll BJ & Shane AL in Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics Vol. 20 (Kliegman R, Stanton B, St Geme J, Schor N & Behrman R eds.) Ch. 109, 794 (Elsevier, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weston EJ et al. The Burden of Invasive Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis in the United States, 2005–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30, 937–941 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osrin D, Vergnano S & Costello A Serious Bacterial Infections in Newborn Infants in Developing Countries. Curr Opin Infect Dis 17, 217–224 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oza S, Lawn JE, Hogan DR, Mathers C & Cousens SN Neonatal Cause-of-Death Estimates for the Early and Late Neonatal Periods for 194 Countries: 2000–2013. Bull World Health Organ 93, 19–28 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukhopadhyay S et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Following Neonatal Late-Onset Sepsis and Blood Culture-Negative Conditions. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukhopadhyay S et al. Impact of Early-Onset Sepsis and Antibiotic Use on Death or Survival with Neurodevelopmental Impairment at 2 years of Age among Extremely Preterm Infants. J Pediatr 221, 39–46.e35 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jardine L, Davies MW & Faoagali J Incubation Time Required for Neonatal Blood Cultures to Become Positive. J Paediatr Child Health 42, 797–802 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar S, Bhagat I, DeCristofaro JD, Wiswell TE & Spitzer AR A Study of the Role of Multiple Site Blood Cultures in the Evaluation of Neonatal Sepsis. J Perinatol 26, 18–22 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhopadhyay S, Sengupta S & Puopolo KM Challenges and Opportunities for Antibiotic Stewardship among Preterm Infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 104, F327–f332 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor JE et al. A Quality Improvement Initiative to Reduce Central Line Infection in Neonates Using Checklists. Eur J Pediatr 176, 639–646 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JVE, Meader N, Wright K, Cleminson J & McGuire W Assessment of C-Reactive Protein Diagnostic Test Accuracy for Late-Onset Infection in Newborn Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA pediatrics 174, 260–268 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedegaard SS, Wisborg K & Hvas AM Diagnostic Utility of Biomarkers for Neonatal Sepsis--a Systematic Review. Infectious diseases (London, England) 47, 117–124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng PC, Ma TP & Lam HS The Use of Laboratory Biomarkers for Surveillance, Diagnosis and Prediction of Clinical Outcomes in Neonatal Sepsis and Necrotising Enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 100, F448–452 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mussap M, Noto A, Cibecchini F & Fanos V The Importance of Biomarkers in Neonatology. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 18, 56–64 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celik IH et al. What Are the Cut-Off Levels for Il-6 and Crp in Neonatal Sepsis? J Clin Lab Anal 24, 407–412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deshmukh HS et al. The Microbiota Regulates Neutrophil Homeostasis and Host Resistance to Escherichia Coli K1 Sepsis in Neonatal Mice. Nat Med 20, 524–530 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starner TD, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH & McCray PB Jr. Expression and Activity of Beta-Defensins and Ll-37 in the Developing Human Lung. J Immunol 174, 1608–1615 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang JP, Chen C & Yang Y [Changes and Clinical Significance of Toll-Like Receptor 2 and 4 Expression in Neonatal Infections]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 45, 130–133 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leaphart CL et al. A Critical Role for Tlr4 in the Pathogenesis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis by Modulating Intestinal Injury and Repair. J Immunol 179, 4808–4820 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornell TT, Wynn J, Shanley TP, Wheeler DS & Wong HR Mechanisms and Regulation of the Gene-Expression Response to Sepsis. Pediatrics 125, 1248–1258 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figueras-Aloy J et al. Serum Soluble Icam-1, Vcam-1, L-Selectin, and P-Selectin Levels as Markers of Infection and Their Relation to Clinical Severity in Neonatal Sepsis. Am J Perinatol 24, 331–338 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kingsmore SF et al. Identification of Diagnostic Biomarkers for Infection in Premature Neonates. Mol Cell Proteomics 7, 1863–1875 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zoelen MA et al. Role of Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4, and the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products in High-Mobility Group Box 1-Induced Inflammation in Vivo. Shock 31, 280–284 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sikora JP, Chlebna-Sokol D & Krzyzanska-Oberbek A Proinflammatory Cytokines (Il-6, Il-8), Cytokine Inhibitors (Il-6sr, Stnfrii) and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines (Il-10, Il-13) in the Pathogenesis of Sepsis in Newborns and Infants. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 49, 399–404 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cockerill FR 3rd. Application of Rapid-Cycle Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction for Diagnostic Testing in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med 127, 1112–1120 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang AH, Yan JJ & Wu JJ Comparison of Five Days Versus Seven Days of Incubation for Detection of Positive Blood Cultures by the Bactec 9240 System. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 17, 637–641 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schelonka RL et al. Volume of Blood Required to Detect Common Neonatal Pathogens. J Pediatr 129, 275–278 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotten CM Adverse Consequences of Neonatal Antibiotic Exposure. Current opinion in pediatrics 28, 141–149 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenberg RG et al. Prolonged Duration of Early Antibiotic Therapy in Extremely Premature Infants. Pediatr Res 85, 994–1000 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouza E, Sousa D, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Lechuz JG & Muñoz P Is the Volume of Blood Cultured Still a Significant Factor in the Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections? J Clin Microbiol 45, 2765–2769 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukhopadhyay S & Puopolo KM Relevance of Neonatal Anaerobic Blood Cultures: New Information for an Old Question. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 7, e126–e127 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Messbarger N & Neemann K Role of Anaerobic Blood Cultures in Neonatal Bacteremia. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 7, e65–e69 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaacobi N, Bar-Meir M, Shchors I & Bromiker R A Prospective Controlled Trial of the Optimal Volume for Neonatal Blood Cultures. Pediatr Infect Dis J 34, 351–354 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Créixems MR et al. Use of Anaerobically Incubated Media to Increase Yield of Positive Blood Cultures in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 21, 443–446 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunne WM Jr., Tillman J & Havens PL Assessing the Need for Anaerobic Medium for the Recovery of Clinically Significant Blood Culture Isolates in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 13, 203–206 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kothari A, Morgan M & Haake DA Emerging Technologies for Rapid Identification of Bloodstream Pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 59, 272–278 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calderaro A et al. Comparison of Peptide Nucleic Acid Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization Assays with Culture-Based Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry for the Identification of Bacteria and Yeasts from Blood Cultures and Cerebrospinal Fluid Cultures. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20, O468–O475 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deck MK et al. Multicenter Evaluation of the Staphylococcus Quickfish Method for Simultaneous Identification of Staphylococcus Aureus and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Directly from Blood Culture Bottles in Less Than 30 Minutes. J Clin Microbiol 50, 1994–1998 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forrest GN et al. Impact of Rapid in Situ Hybridization Testing on Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Positive Blood Cultures. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 58, 154–158 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ly T, Gulia J, Pyrgos V, Waga M & Shoham S Impact Upon Clinical Outcomes of Translation of Pna Fish-Generated Laboratory Data from the Clinical Microbiology Bench to Bedside in Real Time. Therapeutics and clinical risk management 4, 637–640 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neely LA et al. T2 Magnetic Resonance Enables Nanoparticle-Mediated Rapid Detection of Candidemia in Whole Blood. Sci Transl Med 5, 182ra154 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mancini N et al. The Era of Molecular and Other Non-Culture-Based Methods in Diagnosis of Sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev 23, 235–251 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haag H, Locher F & Nolte O Molecular Diagnosis of Microbial Aetiologies Using Sepsitest™ in the Daily Routine of a Diagnostic Laboratory. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 76, 413–418 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straub J et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Roche Septifast Pcr System for the Rapid Detection of Blood Pathogens in Neonatal Sepsis-a Prospective Clinical Trial. PloS one 12, e0187688 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu CL et al. Comparison of 16s Rrna Gene Pcr and Blood Culture for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. Archives de Pediatrie 21, 162–169 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reier-Nilsen T, Farstad T, Nakstad B, Lauvrak V & Steinbakk M Comparison of Broad Range 16s Rdna Pcr and Conventional Blood Culture for Diagnosis of Sepsis in the Newborn: A Case Control Study. BMC Pediatr 9, 5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iroh Tam PY & Bendel CM Diagnostics for Neonatal Sepsis: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Pediatr Res 82, 574–583 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pammi M, Flores A, Versalovic J & Leeflang MM Molecular Assays for the Diagnosis of Sepsis in Neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2, CD011926 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnon S & Litmanovitz I Diagnostic Tests in Neonatal Sepsis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 21, 223–227 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmutz N, Henry E, Jopling J & Christensen RD Expected Ranges for Blood Neutrophil Concentrations of Neonates: The Manroe and Mouzinho Charts Revisited. J Perinatol 28, 275–281 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manroe BL, Weinberg AG, Rosenfeld CR & Browne R The Neonatal Blood Count in Health and Disease. I. Reference Values for Neutrophilic Cells. J Pediatr 95, 89–98 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma D, Farahbakhsh N, Shastri S & Sharma P Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis: A Literature Review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 31, 1646–1659 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman TB, Puopolo KM, Wi S, Draper D & Escobar GJ Interpreting Complete Blood Counts Soon after Birth in Newborns at Risk for Sepsis. Pediatrics 126, 903–909 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Can E, Hamilcikan S & Can C The Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio for Detecting Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 40, e229–e232 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arcagok BC & Karabulut B Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio in Neonates: A Predictor of Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 11, e2019055 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gandhi P & Kondekar S A Review of the Different Haematological Parameters and Biomarkers Used for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. EMJ Hematol 7, 85–92 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Celik IH et al. Automated Determination of Neutrophil Vcs Parameters in Diagnosis and Treatment Efficacy of Neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Res 71, 121–125 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Celik IH et al. The Value of Delta Neutrophil Index in Neonatal Sepsis Diagnosis, Follow-up and Mortality Prediction. Early Hum Dev 131, 6–9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murphy K & Weiner J Use of Leukocyte Counts in Evaluation of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31, 16–19 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ellahony DM, El-Mekkawy MS & Farag MM A Study of Red Cell Distribution Width in Neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Emerg Care 36, 378–383 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han YQ et al. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width Predicts Long-Term Outcomes in Sepsis Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Chim Acta 487, 112–116 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin SL et al. Red Cell Distribution Width and Its Association with Mortality in Neonatal Sepsis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 32, 1925–1930 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dogan P & Guney Varal I Red Cell Distribution Width as a Predictor of Late-Onset Gram-Negative Sepsis. Pediatr Int 62, 341–346 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spector SA, Ticknor W & Grossman M Study of the Usefulness of Clinical and Hematologic Findings in the Diagnosis of Neonatal Bacterial Infections. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 20, 385–392 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang J et al. Diagnostic Value of Mean Platelet Volume for Neonatal Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 99, e21649 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oncel MY et al. Mean Platelet Volume in Neonatal Sepsis. J Clin Lab Anal 26, 493–496 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aydemir C, Aydemir H, Kokturk F, Kulah C & Mungan AG The Cut-Off Levels of Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein and the Kinetics of Mean Platelet Volume in Preterm Neonates with Sepsis. BMC Pediatr 18, 253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eschborn S & Weitkamp JH Procalcitonin Versus C-Reactive Protein: Review of Kinetics and Performance for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. J Perinatol 39, 893–903 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Celik IH, Demirel G, Canpolat FE, Erdeve O & Dilmen U Inflammatory Responses to Hepatitis B Virus Vaccine in Healthy Term Infants. Eur J Pediatr 172, 839–842 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stocker M, Hop WC & van Rossum AM Neonatal Procalcitonin Intervention Study (Neopins): Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided Decision Making on Duration of Antibiotic Therapy in Suspected Neonatal Early-Onset Sepsis: A Multi-Centre Randomized Superiority and Non-Inferiority Intervention Study. BMC Pediatr 10, 89 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balog A, Ocsovszki I & Mándi Y Flow Cytometric Analysis of Procalcitonin Expression in Human Monocytes and Granulocytes. Immunol Lett 84, 199–203 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christ-Crain M & Müller B Procalcitonin in Bacterial Infections--Hype, Hope, More or Less? Swiss Med Wkly 135, 451–460 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ruan L et al. The Combination of Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein or Presepsin Alone Improves the Accuracy of Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Crit Care 22, 316 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Altunhan H, Annagür A, Örs R & Mehmetoğlu I Procalcitonin Measurement at 24 Hours of Age May Be Helpful in the Prompt Diagnosis of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 15, e854–858 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stocker M et al. Procalcitonin-Guided Decision Making for Duration of Antibiotic Therapy in Neonates with Suspected Early-Onset Sepsis: A Multicentre, Randomised Controlled Trial (Neopins). Lancet 390, 871–881 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vouloumanou EK, Plessa E, Karageorgopoulos DE, Mantadakis E & Falagas ME Serum Procalcitonin as a Diagnostic Marker for Neonatal Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intensive Care Med 37, 747–762 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aloisio E, Dolci A & Panteghini M Procalcitonin: Between Evidence and Critical Issues. Clin Chim Acta 496, 7–12 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frerot A et al. Cord Blood Procalcitonin Level and Early-Onset Sepsis in Extremely Preterm Infants. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 38, 1651–1657 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Canpolat FE, Yigit S, Korkmaz A, Yurdakok M & Tekinalp G Procalcitonin Versus Crp as an Early Indicator of Fetal Infection in Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes. Turk J Pediatr 53, 180–186 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lannergård A, Friman G, Ewald U, Lind L & Larsson A Serum Amyloid a (Saa) Protein and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (Hscrp) in Healthy Newborn Infants and Healthy Young through Elderly Adults. Acta Paediatr 94, 1198–1202 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chauhan N, Tiwari S & Jain U Potential Biomarkers for Effective Screening of Neonatal Sepsis Infections: An Overview. Microb Pathog 107, 234–242 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cetinkaya M, Ozkan H, Köksal N, Celebi S & Hacimustafaoğlu M Comparison of Serum Amyloid a Concentrations with Those of C-Reactive Protein and Procalcitonin in Diagnosis and Follow-up of Neonatal Sepsis in Premature Infants. J Perinatol 29, 225–231 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yuan H et al. Diagnosis Value of the Serum Amyloid a Test in Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2013, 520294 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hinson JP, Kapas S & Smith DM Adrenomedullin, a Multifunctional Regulatory Peptide. Endocr Rev 21, 138–167 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oncel MY et al. Proadrenomedullin as a Prognostic Marker in Neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Res 72, 507–512 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fahmey SS, Mostafa H, Elhafeez NA & Hussain H Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Proadrenomedullin in Neonatal Sepsis. Korean J Pediatr 61, 156–159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cekmez F et al. Diagnostic Value of Resistin and Visfatin, in Comparison with C-Reactive Protein, Procalcitonin and Interleukin-6 in Neonatal Sepsis. Eur Cytokine Netw 22, 113–117 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aliefendioglu D, Gursoy T, Caglayan O, Aktas A & Ovali F Can Resistin Be a New Indicator of Neonatal Sepsis? Pediatr Neonatol 55, 53–57 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khattab AA, El-Mekkawy MS, Helwa MA & Omar ES Utility of Serum Resistin in the Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis and Prediction of Disease Severity in Term and Late Preterm Infants. J Perinat Med 46, 919–925 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu TW et al. The Utility of Serum Hepcidin as a Biomarker for Late-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. J Pediatr 162, 67–71 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rao L et al. Progranulin as a Novel Biomarker in Diagnosis of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Cytokine 128, 155000 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Badr HS, El-Gendy FM & Helwa MA Serum Stromal-Derived-Factor-1 (Cxcl12) and Its Alpha Chemokine Receptor (Cxcr4) as Biomarkers in Neonatal Sepsis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 31, 2209–2215 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zonda GI et al. Endocan - a Potential Diagnostic Marker for Early Onset Sepsis in Neonates. J Infect Dev Ctries 13, 311–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fahmey SS & Mostafa N Pentraxin 3 as a Novel Diagnostic Marker in Neonatal Sepsis. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 12, 437–442 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Edgar JD, Gabriel V, Gallimore JR, McMillan SA & Grant J A Prospective Study of the Sensitivity, Specificity and Diagnostic Performance of Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, Highly Sensitive C-Reactive Protein, Soluble E-Selectin and Serum Amyloid a in the Diagnosis of Neonatal Infection. BMC Pediatr 10, 22 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Machado JR et al. Neonatal Sepsis and Inflammatory Mediators. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 269681 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buck C, Bundschu J, Gallati H, Bartmann P & Pohlandt F Interleukin-6: A Sensitive Parameter for the Early Diagnosis of Neonatal Bacterial Infection. Pediatrics 93, 54–58 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sun B et al. A Meta-Analysis of Interleukin-6 as a Valid and Accurate Index in Diagnosing Early Neonatal Sepsis. Int Wound J 16, 527–533 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bender L et al. Early and Late Markers for the Detection of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Dan Med Bull 55, 219–223 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cortes JS et al. Interleukin-6 as a Biomarker of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Am J Perinatol (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kurul S et al. Association of Inflammatory Biomarkers with Subsequent Clinical Course in Suspected Late Onset Sepsis in Preterm Neonates. Crit Care 25, 12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ye Q, Du LZ, Shao WX & Shang SQ Utility of Cytokines to Predict Neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Res 81, 616–621 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Celik IH et al. [the Role of Serum Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive Protein Levels for Differentiating Aetiology of Neonatal Sepsis]. Arch Argent Pediatr 113, 534–537 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Raynor LL et al. Cytokine Screening Identifies Nicu Patients with Gram-Negative Bacteremia. Pediatr Res 71, 261–266 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhou M, Cheng S, Yu J & Lu Q Interleukin-8 for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. PloS one 10, e0127170 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Beutler BA, Milsark IW & Cerami A Cachectin/Tumor Necrosis Factor: Production, Distribution, and Metabolic Fate in Vivo. J Immunol 135, 3972–3977 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lv B et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha as a Diagnostic Marker for Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 471463 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Delanghe JR & Speeckaert MM Translational Research and Biomarkers in Neonatal Sepsis. Clin Chim Acta 451, 46–64 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ganesan P, Shanmugam P, Sattar SB & Shankar SL Evaluation of Il-6, Crp and Hs-Crp as Early Markers of Neonatal Sepsis. J Clin Diagn Res 10, Dc13–17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Venet F, Lepape A & Monneret G Clinical Review: Flow Cytometry Perspectives in the Icu - from Diagnosis of Infection to Monitoring of Injury-Induced Immune Dysfunctions. Crit Care 15, 231 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mazzucchelli I et al. Diagnostic Performance of Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1 and Cd64 Index as Markers of Sepsis in Preterm Newborns. Pediatr Crit Care Med 14, 178–182 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Du J et al. Diagnostic Utility of Neutrophil Cd64 as a Marker for Early-Onset Sepsis in Preterm Neonates. PLoS One 9, e102647 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pugni L et al. Presepsin (Soluble Cd14 Subtype): Reference Ranges of a New Sepsis Marker in Term and Preterm Neonates. PLoS One 10, e0146020 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shi J, Tang J & Chen D Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy of Neutrophil Cd64 for Neonatal Sepsis. Ital J Pediatr 42, 57 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dilli D, Oguz SS, Dilmen U, Koker MY & Kizilgun M Predictive Values of Neutrophil Cd64 Expression Compared with Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive Protein in Early Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. J Clin Lab Anal 24, 363–370 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Streimish I et al. Neutrophil Cd64 with Hematologic Criteria for Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. Am J Perinatol 31, 21–30 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Qiu X et al. Is Neutrophil Cd11b a Special Marker for the Early Diagnosis of Sepsis in Neonates? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 9, e025222 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bellos I et al. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Presepsin in Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Eur J Pediatr 177, 625–632 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Blanco A et al. Serum Levels of Cd14 in Neonatal Sepsis by Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Acta Paediatr 85, 728–732 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Seliem W & Sultan AM Presepsin as a Predictor of Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis in the Umbilical Cord Blood of Premature Infants with Premature Rupture of Membranes. Pediatr Int 60, 428–432 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ahmed AM et al. Serum Biomarkers for the Early Detection of the Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis: A Single-Center Prospective Study. Adv Neonatal Care 19, E26–E32 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Adly AA, Ismail EA, Andrawes NG & El-Saadany MA Circulating Soluble Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1 (Strem-1) as Diagnostic and Prognostic Marker in Neonatal Sepsis. Cytokine 65, 184–191 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Alkan Ozdemir S, Ozer EA, Ilhan O, Sutcuoglu S & Tatli M Diagnostic Value of Urine Soluble Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells (Strem-1) for Late-Onset Neonatal Sepsis in Infected Preterm Neonates. J Int Med Res 46, 1606–1616 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bellos I et al. Soluble Trem-1 as a Predictive Factor of Neonatal Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Inflamm Res 67, 571–578 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dolin HH, Papadimos TJ, Stepkowski S, Chen X & Pan ZK A Novel Combination of Biomarkers to Herald the Onset of Sepsis Prior to the Manifestation of Symptoms. Shock 49, 364–370 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gilfillan M & Bhandari V Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis and Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Clinical Practice Guidelines. Early Hum Dev 105, 25–33 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Luethy PM & Johnson JK The Use of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (Maldi-Tof Ms) for the Identification of Pathogens Causing Sepsis. J Appl Lab Med 3, 675–685 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Scott JS, Sterling SA, To H, Seals SR & Jones AE Diagnostic Performance of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionisation Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry in Blood Bacterial Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infectious diseases (London, England) 48, 530–536 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ruiz-Aragón J et al. Direct Bacterial Identification from Positive Blood Cultures Using Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight (Maldi-Tof) Mass Spectrometry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 36, 484–492 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Guamán AV et al. Rapid Detection of Sepsis in Rats through Volatile Organic Compounds in Breath. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 881–882, 76–82 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]