Abstract

O-antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are currently being generated to develop an O-serotyping scheme for the genus Acinetobacter and to provide potent tools to study the diversity of O-antigens among Acinetobacter strains. In this report, Acinetobacter baumannii strains from the Czech Republic and from two clonal groups identified in Northwestern Europe (termed clones I and II) were investigated for their reactivity with a panel of O-antigen-specific MAbs generated against Acinetobacter strains from various species. The bacteria were characterized for their ribotype, biotype, and antibiotic susceptibility and the presence of the 8.7-kb plasmid pAN1. By using the combination of these typing profiles, the Czech strains could be classified into four previously defined groups (A. Nemec, L. Janda, O. Melter, and L. Dijkshoorn, J. Med. Microbiol. 48:287–296, 1999): two relatively homogeneous groups of multiresistant strains (termed groups A and B), a heterogeneous group of other multiresistant strains, and a group of susceptible strains. O-antigen reactivity was observed primarily with MAbs generated against Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter baumannii strains. A comparison of reaction patterns confirmed the previously hypothesized clonal relationship between group A and clone I strains, which are also similar in other properties. The results show that there is limited O-antigen variability among strains with similar geno- and phenotypic characteristics and are suggestive of a high prevalence of certain A. baumannii serotypes in the clinical environment. It is also shown that O-antigen-specific MAbs are useful for the follow-up of strains causing outbreaks in hospitals.

The potential of members of the genus Acinetobacter to cause infection has been known for decades (7–9, 11, 18). However, only after improvement of species classification within the genus as a result of DNA-DNA hybridization studies (1, 3, 19) was it possible to gain insight into the ecology and clinical significance of individual Acinetobacter species (20). Of these, Acinetobacter baumannii (DNA group 2) has been isolated predominantly from clinical specimens of human origin and is clearly the main species associated with outbreaks of nosocomial infections (21). However, the reliable identification of this species in bacteriological laboratories is hampered by the close pheno- and genotypic relatedness of A. baumannii to three other species within the genus (5), two of which (unnamed DNA groups 3 and 13TU) (19) are known to also cause hospital-acquired infections (21). Due to the successful use of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) as taxonomic markers for a variety of gram-negative bacteria, we have decided to generate O-antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against the LPS of Acinetobacter strains, with the aim of developing an identification scheme for this group of bacteria based on the chemical and antigenic structure of the O-polysaccharide of their LPS.

In a previous study, the pheno- and genotypic similarities among A. baumannii strains isolated in the Czech Republic were analyzed (12). Based on the results, these isolates could be classified into four groups: two relatively homogeneous groups of predominantly multiresistant strains (termed groups A and B) comprising both sporadic and outbreak-associated isolates, a heterogeneous group of other multiresistant strains, and a group of mainly susceptible strains (12). The features of groups A and B were found to be highly similar to those of two outbreak-related A. baumannii clonal groups, clones I and II, which were identified among hospital isolates in Northwestern Europe (6). In this study, we analyzed the O-antigenic relationship among these Czech strains, in comparison to a number of clone I and II strains, by using O-antigen-specific MAbs. The aim of the study was to gain insight into the prevalence of putative Acinetobacter O-serotypes (i.e., the O-antigen diversity), within the Czech Republic in particular, but also within the general clinical environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

The Acinetobacter strains investigated in this study are listed in Table 1 (n = 65). They consisted of a selection of clinical isolates from the Czech Republic (n = 52) and Northwestern Europe (The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium, and Denmark [n = 13]). Most strains were originally isolated from burn wounds, sputum, or urine. Forty-two Czech strains were identified previously as A. baumannii by ribotyping and characterized by antibiotic susceptibility, biotype, and plasmid profile (12). These strains were selected for this study from a set of 77 A. baumannii isolates (12) to be as heterogeneous as possible in their properties, geographical origin, and time of isolation, thus excluding multiple isolates of the same strain from one locality. Ten previously uncharacterized strains were added to broaden the geographical heterogeneity of the strains from the Czech Republic. The 13 strains from Northwestern Europe (Table 1) were identified previously as A. baumannii by DNA-DNA hybridization (6). The geno- and phenotypic characteristics of two of these strains, RUH 875 and RUH 134, have been compared recently to those of clinical isolates from the Czech Republic (12). For the present study, the additional Northwestern European strains and the additionally selected Czech strains were characterized for their ribotype, biotype, and antibiotic susceptibility as described previously (12). The presence of an 8.7-kb-plasmid, termed pAN1, was determined with a digoxigenin-labeled probe prepared from pAN1 of A. baumannii NIPH 632 (12). All strains used in this study were preserved in glycerol stocks at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Geno- and phenotypic properties of A. baumannii strains investigated in this study, their reactivity with O-antigen-specific MAbs in dot and Western blots, and O-banding patterns following acid hydrolysis of membrane-bound LPS and immunostaining with MAb A6 for strains that did not react with any MAb

| Straina | Ribotypeb | pAN1c | Biotyped | Antibiotic resistancee | MAb reactivityf | Acid hydrolysis patterng | Strain isolationh

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yr | City (country) | Specimen | |||||||

| Czech Republic | |||||||||

| Group A strains | |||||||||

| NIPH 7 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1991 | Praha | Burn |

| NIPH 15 | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1991 | Praha | Burn |

| NIPH 56 | I | + | 6 | S | S48-3-13 | ND | 1992 | Praha | Burn |

| NIPH 188 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1993 | Praha | Urine |

| NIPH 207 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1992 | Liberec | Urine |

| NIPH 281 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Příbram | Blood |

| NIPH 290 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Příbram | Urine |

| NIPH 307i | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Ostrava | Burn |

| NIPH 309 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Kladno | Urine |

| NIPH 321 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Tábor | Urine |

| NIPH 357 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Slaný | Sputum |

| NIPH 360 | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1994 | Plzeň | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 392 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1996 | Sedlčany | Decubitus |

| NIPH 408 | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1996 | Plzeň | Sputum |

| NIPH 409 | I | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1996 | Brno | Urine |

| NIPH 470 | I | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1997 | Č. Budějovice | Bronchial secretion |

| NIPH 654 | I | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1996 | Praha | Drainage fluid |

| NIPH 693i | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1997 | Vyšši Brod | Decubitus |

| NIPH 857i | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1997 | Havířov | Unknown |

| NIPH 878i | I | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1998 | Praha | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| NIPH 881i | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1998 | Cheb | Cannula |

| NIPH 921i | I | + | ng | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1997 | Ústí n. Labem | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 1150i | I | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1999 | Hořovice | Tracheostomy |

| Group B strains | |||||||||

| NIPH 24 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1991 | Praha | Urinary catheter |

| NIPH 141 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1993 | Praha | Intravenous cannula |

| NIPH 220 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1993 | Kladno | Lung dissection |

| NIPH 330 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1994 | Tábor | Pus |

| NIPH 455 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1996 | Jihlava | Blood culture |

| NIPH 471 | II | − | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1997 | Č. Budějovice | Bronchial secretion |

| NIPH 499i | II | + | 2 | R | S53-32 | ND | 1997 | Příbram | Sputum |

| Other multiresistant strains | |||||||||

| NIPH 10 | u | + | 6 | R | S51-3 | ND | 1991 | Praha | Blood culture |

| NIPH 47 | u | − | 6 | R | S48-3-17 | ND | 1991 | Praha | Burn |

| NIPH 301 | u | − | 6 | R | − | − | 1994 | Slaný | Sputum |

| NIPH 335 | u | − | 9 | R | − | B | 1994 | Tábor | Sputum |

| NIPH 657 | X | − | 2 | R | − | − | 1996 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 720i | X | − | 2 | R | − | − | 1997 | Č. Budějovice | Bronchial secretion |

| NIPH 732i | X | − | 2 | R | − | − | 1997 | Č. Krumlov | Bronchial secretion |

| Susceptible strains | |||||||||

| NIPH 4 | u | − | 5 | S | − | C | 1991 | Praha | Burn |

| NIPH 33 | u | − | 9 | S | − | A | 1991 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 45 | u | − | 6 | S | − | D | 1991 | Praha | Urinary catheter |

| NIPH 60 | u | − | 9 | S | − | − | 1992 | Praha | Sputum |

| NIPH 67 | u | − | 1 | S | − | − | 1992 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 70 | u | − | 9 | S | − | E | 1992 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 80 | u | − | 9 | S | S48-3-17 | ND | 1993 | Praha | Intravenous cannula |

| NIPH 81 | u | − | 6 | S | − | E | 1993 | Praha | Wound swab |

| NIPH 143 | u | − | 11 | S | S53-25 | ND | 1993 | Praha | Throat swab |

| NIPH 190 | u | − | 8 | S | − | − | 1993 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 201 | u | − | 6 | S | − | F | 1992 | Liberec | Nasal swab |

| NIPH 329 | u | − | 2 | S | S53-32 | ND | 1994 | Tábor | Tracheostomy |

| NIPH 410 | u | − | 11 | S | S53-32 | ND | 1996 | Brno | Cannula |

| NIPH 601 | u | − | 13 | S | − | D | 1993 | Praha | Urine |

| NIPH 615 | u | − | 15 | S | − | D | 1994 | Praha | Tracheostomy |

| Northwestern Europe | |||||||||

| Clone I strains | |||||||||

| RUH 436 | I | + | 6j | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1984 | Utrecht (NL) | Sputum |

| RUH 510 | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1984 | Nijmegen (NL) | Bronchus |

| RUH 875 | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1984 | Dordrecht (NL) | Urine |

| RUH 2037 | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1986 | Venlo (NL) | Sputum |

| GNU 1084 (RUH 3238) | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1987 | Sheffield (UK) | Burn wound |

| GNU 1083 (RUH 3239) | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1985–1988 | London (UK) | Urine |

| GNU 1082 (RUH 3242) | uk | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1989 | Basildon (UK) | Burn wound |

| GNU 1078 (RUH 3247) | I | + | 6 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1990 | Leuven (B) | Rectal mucosa |

| GNU 1079 (RUH 3282) | I | + | 11 | R | S48-3-13 | ND | 1990 | Salford (UK) | Tracheostomy |

| Clone II strains | |||||||||

| RUH 134 | II | − | 1 | R | S48-3-17 | ND | 1982 | Rotterdam (NL) | Urine |

| PGS 189 (RUH 3422) | II | − | 2 | S | S48-3-17 | ND | 1984 | Odense (DK) | Ulcer |

| GNU 1086 (RUH 3240) | u | − | 2 | R | − | B | 1989 | Newcastle (UK) | Respiratory tract |

| GNU 1080 (RUH 3245) | II | + | 9 | R | S48-3-17 | ND | 1989 | Salisbury (UK) | Urinary catheter |

Strain designation as published previously (6, 12). NIPH, National Institute of Public Health (culture collection of A. Nemec); RUH, Rotterdam University Hospital (culture collection of L. Dijkshoorn).

EcoRI ribotypes were designated according to Nemec et al. (12). u, unique ribotype pattern.

Presence (+) or absence (−) of plasmid pAN1 (8.7 kb).

Biotypes were designated according to Bouvet and Grimont (2). ng, strain did not grow on mineral media.

Antibiotic resistance was determined with the following antibiotics: ampicillin plus sulbactam (combined), ceftazidime, imipenem, ticarcillin, cotrimoxazole, gentamicin, tobramycin, ofloxacin, and amikacin. R, resistant to at least two of eight antibiotics; S, susceptible to at least eight antibiotics.

−, no MAb reactivity observed.

O-banding patterns obtained after acid hydrolysis were labeled alphabetically. ND, not determined; −, no banding pattern observed.

B, Belgium; NL, The Netherlands; UK, United Kingdom; DK, Denmark.

Czech strains additionally selected for this study. Strain designations in parentheses indicate strain numbers as presented in the culture collection of L. Dijkshoorn.

This strain was found to belong to biotype 6 instead of biotype 19 (6).

Repeated testing showed that the ribotype pattern of this strain is slightly different (position of one weak band) from that observed for the other clone I strains.

Whole-cell lysates and proteinase K digestion.

Preparation of whole-cell lysates and proteinase K treatment of these lysates were performed as described in another study (14). They were stored at −20°C and heated (100°C, 5 min) prior to use.

MAbs.

The MAbs used in this study are shown in Table 2. Their generation and serological characterization have been described in detail in other studies (15–17; R. Pantophlet, J. A. Severin, A. Nemec, L. Brade, L. Dijkshoorn, and H. Brade, submitted for publication; R. Pantophlet, L. Brade, and H. Brade, submitted for publication). They included MAbs against strains from the clinically more important species such as A. baumannii, DNA group 3, and DNA group 13TU, as well as MAbs against other species within the genus. All antibodies were stored at −20°C when not in use.

TABLE 2.

O-antigen-specific MAbs used in this study and their corresponding immunogens

| MAb | Immunogena | Isotype |

|---|---|---|

| S48-3-13 | 24b (2) | IgG3c |

| S48-3-17 | 34b (2) | IgG3 |

| S48-13 | 108b (13TU) | IgG3 |

| S48-19-14 | 57b (4) | IgG2b |

| S48-26 | 44b (3) | IgG3 |

| S48-30-5 | 57b (4) | IgG2a |

| S48-31-18 | 61b (4) | IgG1 |

| S50-6-14 | 61b (4) | IgG2b |

| S51-3 | 7b (1) | IgG1 |

| S53-1 | ATCC 23055 (1) | IgG3 |

| S53-10 | ATCC 17977 (4) | IgG2a |

| S53-11 | ATCC 17903 (13TU) | IgG1 |

| S53-13 | ATCC 15308 (2) | IgG3 |

| S53-16 | ATCC 43998 (12) | IgG1 |

| S53-19 | ATCC 9957 (9) | IgG2b |

| S53-20 | ATCC 17909 (7) | IgG3 |

| S53-23-3 | ATCC 17979 (6) | IgG3 |

| S53-23-6 | ATCC 11171 (11) | IgG3 |

| S53-25 | ATCC 17988 (16) | IgG1 |

| S53-32 | NCTC 10303 (2) | IgG3 |

MAbs were generated by immunizing BALB/c mice with heat-killed bacteria. ATCC, American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). DNA groups are indicated in parentheses.

Strain designation as used by Dijkshoorn et al. (4).

IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Serological assays.

Dot blotting and Western blotting were performed as described previously (15) with proteinase K-treated bacterial lysates as antigens. Acid hydrolysis of membrane-bound LPS and detection of its lipid A moiety with antibody were performed as described elsewhere (13) with 1% acetic acid and MAb A6 against bisphosphoryl lipid A (10).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

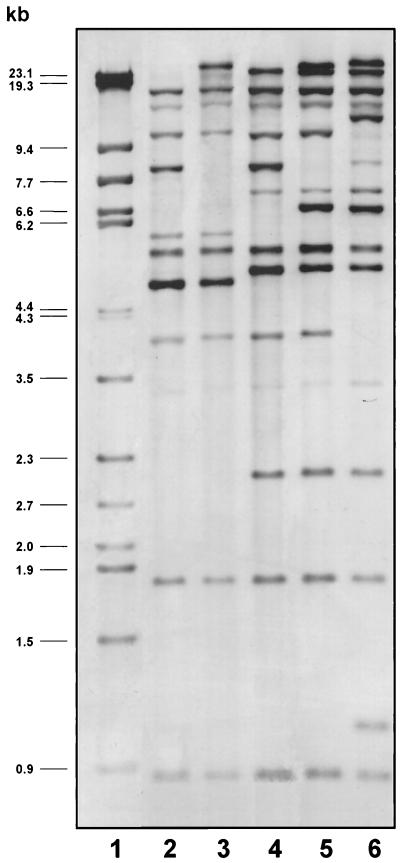

The properties and epidemiological data of the 65 strains are shown in Table 1. Examples of EcoRI ribotypes are shown in Fig. 1. According to their ribotypes, all 10 additonally selected Czech strains were identified as A. baumannii. These strains were all resistant to at least three of nine antibiotics tested. Based on their EcoRI ribotypes and biotypes, seven of these strains (ribotype I, biotype 6 or 11) could be allocated to group A, and one strain (ribotype II, biotype 2) could be allocated to group B. The remaining two strains (ribotype X, biotype 2) were placed in the third group of multiresistant strains. A plasmid with a size of approximately 8.7 kb, termed pAN1 (12), was present in all of the additionally selected strains, which were placed in group A, as well as in the strain allocated to group B.

FIG. 1.

Examples of EcoRI ribotypes observed for A. baumannii strains isolated in the Czech Republic. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (phage λ DNA digested with HindIII and StyI); 2, strain NIPH 7; 3, strain NIPH 10; 4, strain NIPH 24; 5, strain NIPH 60; 6, strain NIPH 615. Strains NIPH 7 and NIPH 24 are representative of isolates allocated to groups A and B, respectively.

Proteinase K-digested lysates of all strains were then tested by dot blotting with the O-antigen-specific MAbs listed in Table 2. Strains giving positive reactions were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting to confirm the reactivity observed in the dot blot with the respective MAb. O-antigen-reactivity was observed to be nearly exclusively with MAbs generated against A. calcoacetius and A. baumannii strains (Table 1). Group A isolates reacted with MAbs S48-3-13 (n = 17) and S51-3 (n = 5), generated against the O-antigens of an A. baumannii strain and an A. calcoaceticus strain, respectively. It is interesting in this context that clone I strains also reacted with MAb S48-3-13. Moreover, in both group A and clone I strains, plasmid pAN1 was found. Together with the previously noted similarities between group A and clone I reference strain RUH 875 (12), this finding strongly supports the hypothesis that group A and clone I strains are clonally related. The five remaining group A strains that reacted with MAb S51-3 may represent a subclonal group, judging from the similarities in their ribotypes and biotypes and the presence of plasmid pAN1 with the other group A strains. Only one other strain (NIPH 10, in the third group of multiresistant Czech strains) also reacted with MAb S51-3. Interestingly, plasmid pAN1 was also found in this strain, and its ribotype was highly similar to the EcoRI ribotype observed for group A and clone I strains (only one band position difference; Fig. 1). Plasmid pAN1 was originally isolated from A. baumannii strain NIPH 632 (12). Although its function and encoded properties are not known, it has been found in all (geographically highly diverse) strains with the EcoRI ribotype specific to clone I strains from Northwestern Europe, but rarely in other A. baumannii strains. This plasmid may thus serve as a clonal marker; however, further studies are needed to assess its role, if any, in the epidemicity of A. baumannii strains. Group B strains reacted exclusively with MAb S53-32, whereas clone II strains reacted primarily with MAb S48-3-17. A clonal relationship between these two groups of strains therefore seems unlikely. However, it must be noted here that clone II strains were originally delineated based primarily on their amplified fragment length polymorphism profile (6); two different EcoRI ribotype patterns were observed among these strains (Table 1) which were similar to the EcoRI ribotypes observed for two other outbreak-related strains that could not be allocated unambiguously to either clone I or II (6). Thus, the possibility of variants or subclones within this particular clonal group cannot be excluded. MAb reactivity with the other Czech strains included in this study was sporadic: two strains reacted with MAb S53-32, two reacted with MAb S48-3-17, and one reacted with MAb S53-25. The latter antibody was generated against the O-antigen of a strain belonging to genomic species 16, and its reactivity with A. baumannii strains would appear to be unusual at first glance. However, we have shown recently (14) that certain O-antigenic determinants may occur in different genomic species. This seems to be true as well for the epitope recognized by MAb S53-25. The generation of more O-antigen-specific antibodies against structurally defined epitopes of the O-polysaccharide chains will help clarify which epitopes determine species specificity and which do not. The high degree of reactivity among the homogeneous groups of multiresistant strains indicates limited O-antigen variation and supports the view that such strains are of a common clonal origin.

By using a method to visualize any LPS via its lipid A moiety with antibody in a Western blot following acid hydrolysis of the membrane-bound antigen (13), it was possible to define the putative O-serotypes of some strains that had not reacted with any of the MAbs used in the present study. Six novel banding patterns (labeled 1 to 6) were observed among 10 of the 17 strains, which did not react with any of the O-antigen-specific MAbs used in this study (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The lack of observation of a pattern for all strains has been noted in other studies (15, 16) and is probably because these strains have a reduced level of O-antigen expression or produce LPS that lacks an O-antigen. This is also an example how such antibodies may help analytical biochemists select those LPS that are worth being analyzed structurally.

FIG. 2.

Representative Western blot of A. baumannii strains that did not react with any of the O-antigen-specific MAbs used in this study following acid hydrolysis (1 h in 1% acetic acid at 100°C) of membrane-bound LPS and immunostaining with lipid A-specific MAb A6. Bacteria are, from left to right, strain NIPH 33 (lane 1), strain NIPH 335 (lane 2), strain NIPH 4 (lane 3), strain NIPH 45 (lane 4), strain NIPH 70 (lane 5), and strain NIPH 201 (lane 6).

The findings presented above suggest that certain A. baumannii serotypes may be more prevalent than others in hospital settings. In the Czech Republic, these would appear to be primarily the serotypes defined by MAbs S48-3-13, S53-32, and S51-3. In Northwestern Europe, the serotypes defined by MAbs S48-3-13 and S48-3-17 would appear to be most prevalent. Recent screening studies (R. Pantophlet, J. A. Severin, A. Nemec, L. Brade, L. Dijkshoorn, and H. Brade, submitted for publication) have shown that the serotypes defined by the MAbs mentioned above are also present in other Eastern European countries, such as Hungary, Bulgaria, and Poland. In Hungary and Bulgaria, the S51-3 serotype was found, whereas in Poland, the serotypes defined by MAbs S48-3-17 and S53-32 were identified among a number of strains tested. The serotypes defined by these three MAbs were also found in Italy. In Germany, the serotypes defined by MAbs S48-3-13 and S53-32 appear to be more common, whereas the S48-3-17 and S51-3 serotypes are found only sporadically. However, a large-scale study will be necessary to depict more precisely the prevalence and geographical spread of these and other serotypes. Thus, with the generation of more O-antigen-specific MAbs, it will be possible not only to complete a serotyping scheme for Acinetobacter, but also to further define the prevalence of Acinetobacter serotypes in clinical settings worldwide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of M. Willen is gratefully acknowledged.

This study was supported in part by research grant 310/98/1602 of the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouvet P J M, Grimont P A D. Taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter with recognition of Acinetobacter baumannii sp. nov., Acinetobacter haemolyticus sp. nov., Acinetobacter johnsonii sp. nov., and Acinetobacter junii sp. nov., and emended descriptions of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter lwoffii. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36:228–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouvet P J M, Grimont P A D. Identification and biotyping of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1987;138:569–578. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet P J M, Jeanjean S. Delineation of new proteolytic genomic species in the genus Acinetobacter. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:291–299. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkshoorn L, Tjernberg I, Pot B, Michel M F, Ursing J, Kersters K. Numerical analysis of cell envelope protein profiles of Acinetobacter strains classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:338–344. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkshoorn L. Acinetobacter—microbiology. In: Bergogne-Bérézin E, Joly-Guillou M L, Towner K J, editors. Acinetobacter: microbiology, epidemiology, infections, management. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijkshoorn L, Aucken H, Gerner-Smidt P, Janssen P, Kaufmann M E, Garaizar J, Ursing J, Pitt T L. Comparison of outbreak and nonoutbreak Acinetobacter baumannii strains by genotypic and phenotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1519–1525. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1519-1525.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glew R H, Moellering R C, Kunz L J. Infections with Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Herellea vaginicola): clinical and laboratory studies. Medicine. 1977;56:79–96. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppe M, Potel J, Malottke R. Clinical importance of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus isolations from blood cultures and venecatheters. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1983;256:80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juni E. Genus III. Acinetobacter Brisou and Prévot 1954, 727AL. In: Krieg N R, editor. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn H M, Brade L, Appelmelk B J, Kusumoto S, Rietschel E T, Brade H. Characterization of the epitope specificity of murine monoclonal antibodies directed against lipid A. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2201–2210. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2201-2210.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lautrop H. Acinetobacter Brisou and Prévot 1954. In: Buchanan R E, Gibbons N E, editors. Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology. 8th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1974. pp. 436–438. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemec A, Janda L, Melter O, Dijkshoorn L. Genotypic and phenotypic similarity of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the Czech Republic. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:287–296. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-3-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantophlet R, Brade L, Brade H. Detection of lipid A by monoclonal antibodies in S-form lipopolysaccharide after acidic treatment of immobilized LPS on Western blot. J Endotoxin Res. 1997;4:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pantophlet R, Brade L, Dijkshoorn L, Brade H. Specificity of rabbit antisera against lipopolysaccharide of Acinetobacter. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1245–1250. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1245-1250.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantophlet R, Brade L, Brade H. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii strains with monoclonal antibodies against the O antigens of their lipopolysaccharides. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:323–329. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.323-329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantophlet R, Brade L, Brade H. Use of a murine O-antigen-specific monoclonal antibody to identify Acinetobacter strains of unnamed genomic species 13 Sensu Tjernberg and Ursing. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1693–1698. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1693-1698.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pantophlet R, Haseley S R, Vinogradov E V, Brade L, Holst O, Brade H. Chemical and antigenic structure of the O-polysaccharide of the lipopolysaccharide from two Acinetobacter haemolyticus strains differing only in the anomeric configuration of one glycosyl residue in their O-antigen. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:587–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taplin D, Rebell G, Zaias N. The human skin as a source of Mima-Herellea infections. JAMA. 1963;186:166–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.63710100030023a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjernberg I, Ursing J. Clinical strains of Acinetobacter classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. APMIS. 1989;97:595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Towner K J, Bergogne-Bérézin E, Fewson C A. Acinetobacter: portrait of a genus. In: Towner K J, Bergogne-Bérézin E, Fewson C A, editors. The biology of Acinetobacter: taxonomy, clinical importance, molecular biology, physiology, industrial relevance. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Towner K J. Clinical importance and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:721–746. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-9-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]