Abstract

Background

We aimed to describe the prevalence of human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) and evaluate associations between HRSV subgroups and/or genotypes and epidemiologic characteristics and clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness (SRI).

Methods

Between January 2012 and December 2015, we enrolled patients of all ages admitted to two South African hospitals with SRI in prospective hospital‐based syndromic surveillance. We collected respiratory specimens and clinical and epidemiological data. Unconditional random effect multivariable logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with HRSV infection.

Results

HRSV was detected in 11.2% (772/6908) of enrolled patients of which 47.0% (363/772) were under the age of 6 months. There were no differences in clinical outcomes of HRSV subgroup A‐infected patients compared with HRSV subgroup B‐infected patients but among patients aged <5 years, children with HRSV subgroup A were more likely be coinfected with Streptococcus pneumoniae (23/208, 11.0% vs. 2/90, 2.0%; adjusted odds ratio 5.7). No significant associations of HRSV A genotypes NA1 and ON1 with specific clinical outcomes were observed.

Conclusions

While HRSV subgroup and genotype dominance shifted between seasons, we showed similar genotype diversity as noted worldwide. We found no association between clinical outcomes and HRSV subgroups or genotypes.

Keywords: human respiratory syncytial virus, severe respiratory illness, South Africa

1. BACKGROUND

In young children and infants, human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) is one of the predominant causes of acute respiratory tract illness. Globally, it was estimated that among children aged <5 years, 33.1 million episodes of HRSV‐associated severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) resulted in approximately 3.2 million (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.7–3.8 million) hospitalizations and 59,600 (95% CI 48,000–74,500) in‐hospital deaths in 2015; 99% of mortalities occurred in developing countries. 1 Among South African patients admitted to sentinel surveillance hospitals for SARI, HRSV detection rates of 27% (1157/4293) and 4% (329/7796) were reported for children aged <5 years (2010–2011) and adults aged >18 years (2009–2013), respectively. 2 , 3 Within these populations, HIV coinfection was found to negatively affect disease outcomes including increased odds of hospitalization. 2

HRSV is divided into two phylogenetically distinct subgroups (HRSV A and B), and these are further classified into multiple distinct genotypes based on sequence variability in the C‐terminus of the envelope glycoprotein G (G protein). 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Since 2002, novel genotype BA, and since 2009 novel genotype ON1, displaying 60‐ and 72‐nucleotide sequence duplications (HRSV subgroups B and A, respectively) within the second variable domain of the C‐terminus have emerged. 4 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 To date, these novel genotypes have disseminated globally, becoming the dominant genotypes in circulation. 4 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 14 Contrasting findings have found no clear consensus between HRSV subgroups/genotypes and clinical outcomes. 4 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 15 Inconsistencies observed between studies may be due to small sample sizes and geographic variances in population diversity and herd immunity, which could predispose to or protect individuals from adverse clinical outcomes.

While no HRSV vaccines are currently available, global HRSV surveillance aided the development of multiple vaccine candidates that are in various stages of evaluation. 16 The high degree of sequence variance and complex circulation patterns of HRSV resulted in challenges for development of an effective HRSV vaccine. 13 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 These challenges include global and regional gaps in knowledge of HRSV epidemiology, subgroup and genotype geographic circulation patterns, target patient demographics, and outcomes for HRSV‐associated clinical illness. 16 Regular updates of these knowledge gaps provide an information baseline that can be used to evaluate regional vaccine effectiveness when implemented and can inform vaccine formulation suitability and timing.

In this study, we aimed to describe the seasonal patterns and prevalence of HRSV subgroups and genotypes among hospitalized patients with severe respiratory illness (SRI) in South Africa, from 2012 through 2015. We also aimed to compare the associations of HRSV subgroups and genotypes with epidemiologic characteristics and clinical outcomes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and population

We enrolled participants in a prospective hospital‐based SRI surveillance program from 01 January 2012 through 31 December 2015 at Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong Hospitals situated in periurban areas in the subtropical KwaZulu‐Natal and temperate North West Provinces of South Africa, respectively. The SRI case definition included hospitalized individuals of any age with illness onset of any duration prior to admission meeting age‐specific inclusion criteria. Children aged 2 days to <3 months included any hospitalized patient with diagnosis of suspected sepsis or physician‐diagnosed lower respiratory tract infection. 20 Children aged 3 months to <5 years included any hospitalized patient with physician‐diagnosed lower respiratory tract infection, including bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and pleural effusion. 20 Individuals aged ≥5 years included any hospitalized patient presenting with lower respiratory tract infection with temperature ≥38°C or history of fever and cough. 20 A case investigation form that included clinical details (fever [≥38°C], cough, requirement for supplemental oxygen, prolonged hospitalization [≥5 days], in‐hospital death, admission to ICU, tachypnea, stridor) and underlying medical conditions (HIV infection, prematurity, heart disease, malnutrition, chronic lung disease, and asthma) was completed for all enrolled patients.

2.2. Sample collection

Respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal aspirates for children <5 years of age and combined nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs from individuals ≥5 years of age) were collected and placed in universal transport medium (Copan, California, USA), stored at 4°C–8°C and transported within 72 h of collection to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), Johannesburg, South Africa, for testing. 20 Whole blood samples (EDTA) were collected from consenting patients for the detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) by lytA polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

2.3. Determination of HIV status

HIV infection status was obtained from a combination of two sources: (i) patient clinical records and (ii) for consenting patients, dried blood spots that were tested by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for patients aged ≥18 months and PCR for children aged <18 months if the ELISA was reactive or exposure status was unknown.

2.4. Laboratory detection of HRSV

Samples collected from 2012 through 2014 were tested for the presence of HRSV and other respiratory viruses (influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza virus [PIV] types 1–3, adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, human metapneumovirus [hMPV], and enteroviruses) using an in‐house multiplex real‐time reverse transcription PCR (rt‐RTPCR) assay. 21 From 2015, a validated commercial one‐step multiplex rt‐RTPCR assay, FTD® Flu‐HRSV kit (FastTrack Diagnostics, Luxembourg), was used for the detection of HRSV and influenza A and B viruses. The 2015 samples were also tested for adenoviruses, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses (PIV) types 1–4, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), and rhinoviruses as before but now human bocaviruses and seasonal human coronaviruses types (NL63, 229E and OC43) were included in our testing panel using the Allplex one‐step rt‐RTPCR respiratory panels 2 and 3 (Seegene, Seoul, Korea).

2.5. Determination of HRSV A/B subgroup by real‐time reverse transcription PCR

HRSV subgroup was determined on all subgrouped samples using an in‐house one‐step rt‐RTPCR designed for the detection of HRSV A and HRSV B using previously published methods. 22 , 23

2.6. Amplification and sequencing of the HRSV G protein gene

The complete HRSV G‐protein gene was PCR‐amplified following random primer cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A first round PCR utilized 5 μl of cDNA, the G1‐21 14 and F164 primers 24 with Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase system (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). The second round PCR utilized the G32A(HRSV A), G598A(HRSV A) /G32B(HRSV B), G604B(HRSV B) forward, or G665R and F1 reverse primers as described. 25 HRSV‐positive samples with insufficient volume or positives with cycle threshold (Ct)‐values of >35 were not PCR amplified for sequencing as they were unlikely to successfully amplify. PCR products were analyzed and viewed following gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and purified using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean‐Up System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Cycle sequencing was performed with the BigDye terminator 3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences were assembled using Sequencher® version 5 (Gene Codes Corporation, Michigan, USA). Sequences with the following accession numbers MN516831 to MN517111 were uploaded to GenBank.

2.7. Phylogenetic analysis of HRSV partial G protein genes

Unique HRSV A and HRSV B virus G‐gene nucleotide sequences representing the second variable domain (330 base pairs: nucleotides 5323–5652) were aligned separately using Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log Expectation (MUSCLE), along with unique international genotype reference sequences (accession numbers shown in Figure 3), downloaded from the GenBank sequence database, using default settings. 26 As the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) predominantly contains partial HRSV G protein gene sequences spanning the second variable domain; this was the gene region selected for partial sequence G‐protein alignments in this analysis. Phylogenies were determined by the construction of maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees using RaxML (Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, Heidelberg, Germany) with the GTR‐GAMMA nucleotide substitution model with branch support assessed with 100 bootstrap replicates. 27

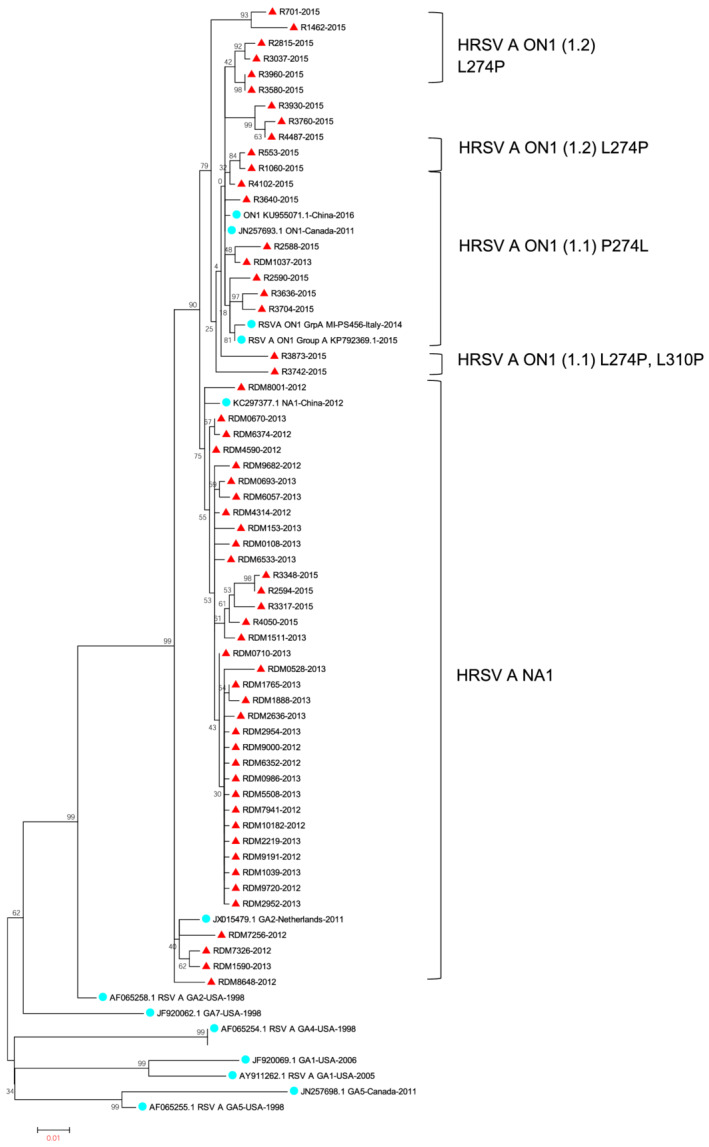

FIGURE 3.

Inferred phylogeny of human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) A G‐gene second variable domain of south African HRSV A isolates (red triangles) based on maximum likelihood model (Mega 5.0 under GTR GAMMA model of nucleotide evolution). Selected publicly available sequences global HRSV A sequences are represented by GenBank accession numbers (blue circles). Brackets indicate HRSV NA1 and ON1 (1.1, 1.2, and 1.3) lineages. Sample dates indicated by last 4 digits of sample names

2.8. Statistical analysis

Unconditional logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with HRSV‐positivity and factors associated with HRSV A and HRSV B‐positivity among individuals hospitalized with SRI aged <5 years and ≥5 years separately. We assessed factors associated with commonly identified genotypes, ON1 and NA1 among HRSV‐positive patients aged <5 years with available genotype results. We further assessed factors associated with presence of fever among HRSV‐positive patients of all ages. A random effect on admission facility was included for all analysis to account for potential differences in the service population. Variables for which the p value in univariate analysis was ≤0.2 were assessed in multivariable models by forward selection and statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05. The analysis was performed using STATA 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

2.9. Ethical considerations

The SRI surveillance protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC; protocol number M081042), the University of KwaZulu Natal, Human Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) protocol number BF157/08. This surveillance protocol was reviewed and deemed nonresearch (number 2012‐6197) by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, Georgia, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

From 2012 through 2015, we enrolled 6910 patients with SRI of which 6908 (>99.9%) had available laboratory test results and were included in the analysis. Of these, 36.3% (2509/6908) were children aged <5 years (Table 1) and 49.6% (3421/6897) were female. HIV results were available for 94.1% (6498/6908) of patients of whom 51.9% (3372/6498) were HIV infected. The HIV prevalence was lowest (10.1%; 143/1417) among infants aged <1 year and highest (90.5%; 1884/2081) among individuals aged 25–44 years.

TABLE 1.

Factors associated with HRSV infection among children aged <5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015

| Characteristic | HRSV positive n/N (%) | HRSV negative n/N (%) | Univariate odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Multivariable adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) ≤ 5 years | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 601/2509 (23.9) | 1908/2509 (76.1) | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| <3 months | 229/601 (38.1) | 360/1908 (18.9) | 4.8 (3.5–6.7) | <0.001 | 4.5 (3.0–6.9) | <0.001 |

| 3–5 months | 134/601 (22.3) | 306/1908 (16.0) | 3.3 (2.4–4.7) | <0.001 | 3.4 (2.2–5.2) | <0.001 |

| 6–11 months | 106/601 (17.6) | 404/1908 (21.2) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.3–3.1) | 0.001 |

| 12–23 months | 78/601 (13.0) | 427/1908 (22.4) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.083 | 1.6 (1.1–2.6) | 0.024 |

| 24–59 months | 54/601 (9.0) | 411/1908 (21.5) | Reference | Reference | ‐ | |

| Female | 256/600 (42.7) | 844/1907 (44.3) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.493 | ||

| Year | ||||||

| 2012 | 188/601 (31.3) | 521/1908 (27.3) | Reference | |||

| 2013 | 165/601 (27.5) | 590/1908 (30.9) | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) | 0.037 | ||

| 2014 | 133/601 (22.1) | 401/1908 (21.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.521 | ||

| 2015 | 115/601 (19.1) | 396/1908 (20.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.110 | ||

| Clinical presentation and course | ||||||

| Fever ≥38°C | 370/598 (61.9) | 1219/1896 (64.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.284 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.035 |

| Cough | 581/596 (97.5) | 1615/1890 (85.4) | 6.6 (3.9–11.2) | <0.001 | 7.6 (4.2–13.7) | <0.001 |

| Supplemental oxygen needed | 409/599 (68.3) | 1008/1889 (53.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.002 |

| Prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days) | 302/601 (50.2) | 913/1908 (47.9) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.305 | ||

| In‐hospital death | 4/597 (0.7) | 29/1883 (1.54) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.082 | ||

| Admitted to ICU | 24/598 (4.0) | 80/1887 (4.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.809 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.012 |

| Tachypnea | 335/595 (56.3) | 879/1880 (46.8) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Stridor | 121/595 (20.3) | 324/1878 (17.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.091 | ||

| Underlying medical conditions | ||||||

| HIV infection | 32/549 (5.8) | 246/1756 (14.0) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | <0.001 |

| Prematurity | 68/600 (11.3) | 257/1907 (13.5) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.167 | ||

| Heart disease | 1/600 (0.2) | 5/1906 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.07–5.44) | 0.663 | ||

| Malnutrition | 92/534 (17.2) | 469/1746 (26.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1/600 (0.2) | 3/1905 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.11–10.2) | 0.961 | ||

| Asthma | 7/600 (1.2) | 27/1906 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.9) | 0.639 | ||

| Coinfection | ||||||

| Tuberculosis | 6/150 (4) | 24/559 (4.3) | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) | 0.873 | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 35/404 (8.7) | 151/1348 (11.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.138 | ||

| Influenza A/B | 10/601 (1.7) | 130/1908 (6.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | <0.001 |

| Rhinovirus | 154/601 (25.6) | 763/1908 (40.0) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | <0.001 |

| Adenovirus | 93/601 (15.5) | 460/1908 (24.1) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Enterovirus | 35/601 (5.8) | 142/1908 (7.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.168 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | |

| Human metapneumovirus | 5/601 (0.8) | 115/1908 (6.0) | 0.1 (0.05–0.3) | <0.001 | 0.1 (0.04–0.3) | <0.001 |

| Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, 3 | 10/601 (1.7) | 168/1908 (8.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.003 |

Note: Bold emphasizes statistically significant variables.

CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; n/N = sample size/population size.

3.2. HRSV detection

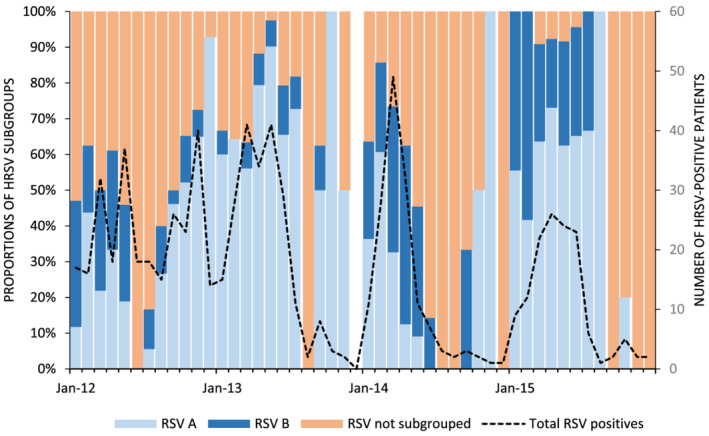

During the study period, HRSV was detected in 11.2% (772/6908) of samples, 24.0% (601/2509) among individuals aged <5 years and 3.9% (171/4399) among individuals ≥5 years of age. Of the 772 HRSV‐infected patients, 47.0%, (363/772) were <6 months of age. Year‐round HRSV activity was observed across the 4‐year observation period with a surge of HRSV activity observed each year between March and May (autumn) (2012–2015) resulting in a single peak per year (Figure 1). An apparent second peak or surge of HRSV activity was noted between September and December of 2012 (Spring–Summer). This second peak was only observed for patients admitted to Edendale Hospital located in the KwaZulu‐Natal Province of South Africa (Figure S1).

FIGURE 1.

Monthly number of human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV)‐positive patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015. The proportion of positives belonging to subgroup A, B and not typed is also indicated in the bar graph

3.3. Factors associated with HRSV‐positivity in patients hospitalized with SRI

On multivariable analysis considering clinical presentation, underlying medical conditions and coinfection variables among persons aged <5 years, a higher odds of HRSV infection was associated with younger age groups when compared to individuals aged 24–59 months (<3 months adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 4.5; 3–5 months aOR: 3.4; 6–11 months aOR: 2.0; 12–23 months aOR: 1.6). In addition, HRSV‐positive children were more likely to present with temperature ≥38°C (aOR: 1.3), have a cough (aOR: 7.6), and receive oxygen support during admission (aOR: 1.4) (Table 1). HRSV‐positive children were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) (aOR: 0.4), to be malnourished (aOR: 0.5), be HIV infected (aOR: 0.4), and be coinfected with influenza viruses (aOR: 0.2), rhinoviruses (aOR: 0.4), enteroviruses (aOR: 0.6), hMPV (aOR: 0.1), and PIV 1–3 (aOR: 0.2) than HRSV‐negative children (Table 1). HRSV positive persons aged <5 years, persons aged ≥3 months were more likely to present with fever when compared to those <3 months (3–5 months aOR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.7–2.8; 6–11 months aOR: 2.9, 95% CI: 2.3–3.8; 12–23 months aOR: 3.2, 95% CI: 2.4–4.1; 24–59 months aOR: 2.8, 95% CI: 2.2–3.7) (data not shown).

HRSV‐positive individuals ≥5 years were more likely to be HIV infected (aOR: 1.6) and to be coinfected with enteroviruses (aOR: 7.3) than HRSV‐negatives children aged <5 years (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with HRSV infection among patients aged ≥5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015

| Characteristic | HRSV positive n/N (%) (N = 171) | HRSV negative n/N (%) | Univariate odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Multivariable adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) years | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 171/4399 (3.9) | 4228/4399 (96.1) | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 5–24 years | 38/171 (22.2) | 562/4228 (13.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 25–44 years | 82/171 (48.0) | 2094/4228 (49.5) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.007 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.008 |

| 45–64 years | 39/171 (22.8) | 1226/4228 (29.0) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.001 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.010 |

| 65 + years | 12/171 (7.0) | 346/4228 (8.2) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.048 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.606 |

| Female | 102/170 (60) | 2219/4220 (52.6) | 1.4 (0.9–1.8) | 0.060 | ||

| Year | ||||||

| 2012 | 86/171 (50.3) | 1487/4230 (35.2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2013 | 49/171 (28.7) | 1128/4230 (26.7) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.118 | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.160 |

| 2014 | 17/171 (9.9) | 836/4230 (19.8) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | <0.001 |

| 2015 | 19/171 (11.1) | 779/4230 (18.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 0.001 | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.009 |

| Clinical presentation and course | ||||||

| Fever ≥38°C | 69/169 (40.8) | 1688/4197 (40.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.874 | ||

| Cough | 128/148 (86.5) | 3503/3833 (91.4) 333 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.053 | ||

| Supplemental oxygen needed | 74/170 (43.5) | 1562/4147 (37.7) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 0.126 | ||

| Prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days) | 117/171 (68.4) | 2848/4230 (67.3) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.765 | ||

| In‐hospital death | 19/162 (11.7) | 485/4106 (11.8) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 0.974 | ||

| Admitted to ICU | 1/169 (0.6) | 21/4144 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.2–8.7) | 0.882 | ||

| Tachypnea | 2/4 (50) | 6/22 (27.3) | 2.7 (0.3–23.4) | 0.380 | ||

| Stridor | 0/4 (0) | 3/22 (13.6) | ||||

| Underlying medical conditions | ||||||

| HIV infection | 125/156 (80.1) | 2943/3966 (74.2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.088 | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.033 |

| Heart disease | 3/170 (1.8) | 72/4222 (1.7) | 1.0 (0.3–3.3) | 0.954 | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 0/170 (0) | 28/4222 (0.7) | ||||

| Asthma | 7/170 (4.1) | 142/4222 (3.4) | 1.2 (0.6–2.7) | 0.606 | ||

| Coinfection | ||||||

| Tuberculosis | 18/101 (17.8) | 653/2706 (24.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.132 | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 21/162 (13.0) | 465/3965 (11.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.637 | ||

| Influenza | 7/171 (4.1) | 185/4230 (4.4) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.859 | ||

| Rhinovirus | 33/171 (19.3) | 693/4230 (16.4) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.324 | ||

| Adenovirus | 27/171 (15.8) | 296/4230 (7.0) | 2.5 (1.6–3.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Enterovirus | 10/171 (5.8) | 35/4230 (0.8) | 7.4 (3.6–15.3) | <0.001 | 7.3 (3.4–15.7) | <0.001 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 2/171 (1.2) | 46/4230 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.3–4.5) | 0.920 | ||

| Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, 3 | 1/171 (0.6) | 86/4230 (2.0) | 0.3 (0.04–2.04) | 0.119 | ||

Note: Bold emphasizes statistically significant variables.

CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; n/N = sample size/population size.

3.4. HRSV subgroup detection and factors associated with HRSV subgroups among HRSV‐positive patients hospitalized with SRI

About two thirds, 67.2% (519/772) of HRSV‐positive samples, were subgrouped, of which 71.1% (369/519) were HRSV A. HRSV A was the predominate subgroup across all years except 2014 (2012: 68.8%, 2013: 90.3%, and 2015: 67.5%) (Figure 1). Similar proportions of HRSV A (45.8%, 44/96) and HRSV B (54.2%, 52/96) were seen in 2014. HRSV A positive patients <5 years were more likely to be coinfected with S. pneumoniae (aOR: 5.7), but there were no clinical differences (Table 3). No statistically significant differences were found between HRSV A and HRSV B positive individuals aged ≥5 years (Table S1).

TABLE 3.

Factors associated with HRSV subgroups among children aged <5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015

| HRSV A subgroup | HRSV B subgroup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HRSV subgrouped n/N (%) | Samples positive/samples tested (%) | Samples positive/samples tested (%) | Univariate odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Multivariable adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) < 5 years | p value |

| Total | 449/601 (74.7) | 319/449 (71.0) | 130/449 (29.0) | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| <3 months | 165/449 (36.7) | 115/319 (36.1) | 50/130 (38.5) | Reference | |||

| 3–5 months | 105/449 (23.4) | 76/319 (23.8) | 29/130 (22.3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 0.637 | ||

| 6–11 months | 77/449 (17.1) | 60/319 (18.8) | 17/130 (13.1) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 0.185 | ||

| 12–23 months | 52/449 (11.6) | 44/319 (13.8) | 18/130 (13.8) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 0.852 | ||

| 24–59 months | 40/449 (8.9) | 24/319 (7.5) | 16/130 (12.3) | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) | 0.241 | ||

| Female | 198/449 (44.1) | 137/319 (42.9) | 61/130 (46.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.442 | ||

| Year | |||||||

| 2012 | 122/449 (27.2) | 87/319 (27.3) | 35/130 (26.9) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2013 | 139/449 (31.0) | 125/319 (39.2) | 14/130 (10.8) | 3.6 (1.8–7.1) | <0.001 | 5.2 (2.0–13.3) | 0.001 |

| 2014 | 86/449 (19.2) | 40/319 (12.5) | 46/130 (35.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 0.027 |

| 2015 | 102/449 (22.7) | 67/319 (21.0) | 35/130 (26.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.366 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.535 |

| Clinical presentation and course | |||||||

| Fever ≥38°C | 275/448 (61.4) | 192/319 (60.2) | 83/129 (64.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.412 | ||

| Cough | 439/447 (98.2) | 311/317 (98.1) | 128/130 (98.5) | 0.8 (0.2–4.1) | 0.795 | ||

| Supplemental oxygen needed | 310/449 (69.0) | 222/319 (69.6) | 88/130 (67.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.694 | ||

| Prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days) | 226/449 (50.3) | 162/319 (50.8) | 64/130 (49.2) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.765 | ||

| In‐hospital death | 3/448 (0.7) | 3/318 (0.9) | 0/130 (0) | ||||

| Admitted to ICU | 16/449 (3.6) | 8/319 (2.5) | 8/130 (6.2) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.072 | ||

| Tachypnea | 249/447 (55.7) | 173/317 (54.6) | 76/130 (58.5) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.452 | ||

| Stridor | 88/447 (19.7) | 63/317 (19.9) | 25/130 (19.2) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.876 | ||

| Underlying medical conditions | |||||||

| HIV infection | 21/417 (5.0) | 12/297 (4.0) | 9/120 (7.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.158 | ||

| Prematurity | 52/449 (11.6) | 40/319 (12.5) | 12/130 (9.2) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.311 | ||

| Heart disease | 1/449 (0.2) | 0/319 (0) | 1/130 (0.8) | ||||

| Malnutrition | 70/405 (17.3) | 52/297 (17.5) | 18/108 (16.7) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.843 | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 1/449 (0.22) | 0/319 (0) | 1/130 (0.8) | ||||

| Asthma | 3/449 (0.7) | 3/319 (0.9) | 0/130 (0) | ||||

| Coinfection | |||||||

| Tuberculosis | 4/121 (3.3) | 4/93 (4.3) | 0/28 (0) | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 25/298 (8.4) | 23/208 (11.1) | 2/90 (2.2) | 5.5 (1.3–23.7) | 0.005 | 5.7 (1.3–25.6) | 0.024 |

| Influenza | 7/449 (1.6) | 5/319 (1.6) | 2/130 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.2–5.3) | 0.982 | ||

| Rhinovirus | 113/449 (25.2) | 79/319 (24.8) | 34/130 (26.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.759 | ||

| Adenovirus | 64/449 (14.3) | 48/319 (15.0) | 16/130 (12.3) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.446 | ||

| Enterovirus | 20/449 (4.5) | 16/319 (5.0) | 4/130 (3.1) | 1.7 (0.5–5.1) | 0.350 | ||

| Human metapneumovirus | 5/449 (1.1) | 5/319 (1.6) | 0/130 (0) | ||||

| Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, 3 | 8/449 (1.8) | 7/319 (2.2) | 1/130 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.4–23.8) | 0.263 | ||

Note: Bold emphasizes statistically significant variables.

CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; n/N = sample size/population size.

3.5. HRSV genotype prevalence and factors associated with HRSV genotypes among HRSV‐positive patients hospitalized with SRI

Among the 519 HRSV A/B‐subgrouped specimens, 33.7% (175/519) of HRSV positives (A: 82.3% [144/175]; B: 17.7% [31/175]) were sequenced and included for phylogenetic analysis. A total of 18.7% (144/519) and 30.1% (156/519) were excluded from G‐protein amplification and sequencing due to low nucleic acid concentration (Ct value >35) and insufficient specimen volume, respectively, whereas 8.5% (44/519) of specimens yielded low quality, unusable sequence data.

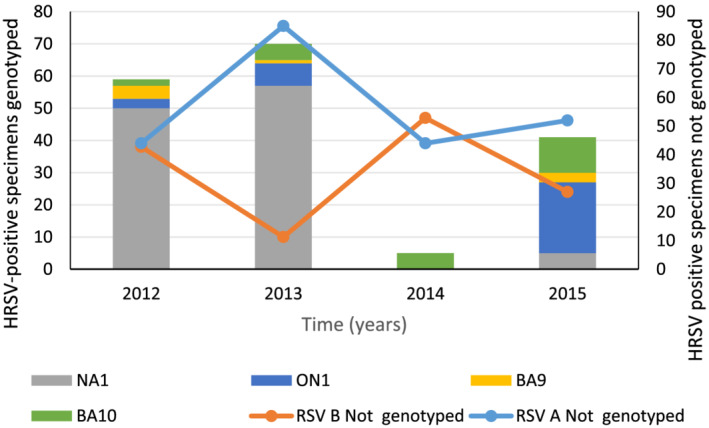

The HRSV A genotype NA1 predominated in 2012 (94% [50/53]) and 2013 (89% [57/64]), and ON1 in 2015 (81% [22/27]) (Figure 2). HRSV B genotypes BA9 and BA10 circulated concurrently with HRSV A genotypes in 2012–2015. Five HRSV B positives genotyped in 2014 were all genotype BA10. HRSV A ON1 lineages 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 were circulating in 2015 (Figure 3); 77% (135/175) of samples genotyped were from the <5 years age category. In this age category, HRSV A genotypes NA1 and ON1 showed associations with year and prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days) but these did not remain significant in the multivariable model (Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) genotypes detected among patients of any age, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015

TABLE 4.

Factors associated with HRSV A genotypes among patients aged <5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015

| NA1 genotype | ON1 genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HRSV genotyped n/N (%) | Samples positive/samples tested (%) | Samples positive/samples tested (%) | Univariate odds ratio (95% CI) | p value |

| Total | 135/319 (42.3) | 104/135 (77.0) | 31/135 (23.0) | ||

| Age | |||||

| <3 months | 53/135 (39.3) | 41/104 (39.4) | 12/31 (38.7) | Reference | |

| 3–5 months | 35/135 (25.9) | 28/104 (26.9) | 7/31 (22.6) | 0.8 (0.3–2.4) | 0.768 |

| 6–11 months | 23/135 (17.0) | 18/104 (17.3) | 5/31 (16.1) | 0.9 (0.3–3.1) | 0.931 |

| 12–23 months | 14/135 (10.4) | 10/104 (9.6) | 4/31 (12.9) | 1.4 (0.4–5.2) | 0.644 |

| 24–59 months | 10/135 (7.4) | 7/104 (6.7) | 3/31 (9.7) | 1.5 (0.3–6.6) | 0.618 |

| Female | 62/135 (45.9) | 52/104 (50.0) | 10/31 (32.3) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.079 |

| Year | |||||

| 2012 | 50/135 (37.0) | 47/104 (45.2) | 3/31 (9.7) | Reference | |

| 2013 | 61/135 (45.2) | 54/104 (51.9) | 7/31 (22.6) | 2.0 (0.5–8.3) | 0.324 |

| 2015 | 24/135 (17.8) | 3/104 (2.9) | 21/31 (67.7) | 109.7 (20.4–588.9) | <0.001 |

| Clinical presentation and course | |||||

| Fever ≥38°C | 82/135 (60.7) | 63/104 (60.6) | 19/31 (61.3) | 1.0 (0.5–2.3) | 0.943 |

| Cough | 132/134 (98.5) | 102/103 (99.0) | 30/31 (96.8) | 0.3 (0.2–4.8) | 0.405 |

| Supplemental oxygen needed | 91/134 (67.9) | 72/103 (69.9) | 19/31 (61.3) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.373 |

| Prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days) | 73/135 (54.1) | 62/104 (59.6) | 11/31 (35.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.018 |

| In‐hospital death | 2/133 (1.5) | 1/102 (0.98) | 1/31 (3.2) | 3.4 (0.2–55.5) | 0.408 |

| Admitted to ICU | 1/134 (0.75) | 1/103 (0.97) | 0/31 (0) | ||

| Tachypnea | 79/134 (59.0) | 60/103 (58.3) | 19/31 (61.3) | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 0.762 |

| Stridor | 29/134 (21.6) | 26/103 (25.2) | 3/31 (9.7) | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.049 |

| Underlying medical conditions | |||||

| HIV infection | 5/123 (4.1) | 5/94 (5.3) | 0/29 (0) | ||

| Prematurity | 14/135 (10.4) | 12/104 (11.5) | 2/31 (6.5) | 0.5 (0.1–2.5) | 0.392 |

| Heart disease | 0/135 (0) | ||||

| Malnutrition | 25/132 (18.9) | 21/101 (20.8) | 4/31 (12.9) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.311 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0/135 (0) | ||||

| Asthma | 1/135 (0.7) | 0/104 (0) | 1/31 (3.2) | ||

| Coinfection | |||||

| Tuberculosis | 1/35 (2.9) | 1/27 (3.7) | 0/8 (0) | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 8/83 (9.6) | 6/66 (9.1) | 2/17 (11.8) | 1.3 (0.2–7.3) | 0.745 |

| Influenza | 1/135 (0.7) | 1/104 (1.0) | 0/31 (0) | ||

| Rhinovirus | 39/135 (28.9) | 32/104 (30.8) | 7/31 (22.6) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 0.369 |

| Adenovirus | 22/135 (16.3) | 21/104 (20.2) | 1/31 (3.2) | 0.1 (0.02–1.02) | 0.010 |

| Enterovirus | 5/135 (3.7) | 4/104 (3.8) | 1/31 (3.2) | 0.8 (0.1–7.7) | 0.871 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 1/135 (0.7) | 1/104 (1.0) | 0/31 (0) | ||

| Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, 3 | 1/135 (0.7) | 0/104 (0) | 1/31 (3.2) | ||

Note: CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; n/N = sample size/population size.

4. DISCUSSION

Similar to previous studies conducted in South Africa and other temperate climates, low levels of HRSV activity occurred year‐round in individuals admitted for SRI over the 4‐year surveillance period with peaks of activity occurring between the autumn and early winter months. 2 , 3 , 28 , 29 In 2012, higher year‐round as well as an additional peak of HRSV activity during the September–December period (Spring–Summer) was observed at Edendale Hospital, which is in the subtropical climate of the KwaZulu‐Natal Province. This is consistent with previous observations in tropical and subtropical climates, which demonstrate year round activity with some seasonal peaks, which may not be consistent over consecutive years. 29

In patients with SRI, prevalence of HRSV‐associated illness was 23.9% (601/2509) and 3.9% (171/4399), respectively, in patients aged <5 and ≥5 years showing trends consistent with previous South African SARI studies (27% and 4% prevalence in children [<5 years] and adults [>18 years], respectively 2 , 3 ). Among children aged <5 years, HRSV‐infected patients were more likely to have fever (≥38° C), cough, and the requirement for supplemental oxygen but were less likely to be malnourished, HIV‐infected, admitted to ICU, or have respiratory virus coinfections. Within the <5 years age group, we also showed that HRSV‐infected children aged ≥3 months were more likely to present with fever when compared to children aged <3 months. This corroborates previous findings that inclusion of fever in the SARI/SRI case definition could limit HRSV case detection among young children hospitalized with lower respiratory tract infection. 30 Moderate to late preterm infants born at 33–35 weeks gestational age have previously also been shown to require supplemental oxygen during HRSV infection and admission to the ICU. 31 The decreased likelihood of ICU admission for HRSV‐positive patients aged <5 years observed in this study seems counterintuitive but studies that have shown an increased likelihood have done so in populations with a high prevalence of underlying disorders. 32 Previous studies from South Africa reported that respiratory virus coinfection in children aged <5 years with HRSV‐associated SRI was unlikely. 33 , 34 Individuals in the ≥5‐year age group with HRSV‐associated SRI, on the contrary, were more likely to be HIV infected, consistent with higher HIV prevalence in these age groups. As both humoral and cellular immunity are required to control acute HRSV infections, an increased likelihood of HRSV infection in ≥5 year HIV‐infected individuals may stem from an HIV‐directed impairment of host immunity, while in the <5 year age group, it is likely that HRSV infection is driven by HRSV‐naïve immune systems. 35 , 36 , 37 Moyes et al. showed that HRSV‐infected patients (<5 years) with SARI who were HIV‐infected demonstrate a threefold to fivefold increased odds of hospitalization, higher odds of death, and increased length of hospitalization when compared with HIV‐negative children. 2

Similar to previous studies, we demonstrated dynamic HRSV subgroup prevalence characterized by the cocirculation and year‐on‐year changes in the prevalence of each subgroup but favoring HRSV A (2012: 69%, 2013: 90%, 2014: 46%, and 2015: 68%) as the most dominant subgroup in most years. While some studies have shown a trend toward HRSV A causing more severe clinical outcomes when compared with HRSV B, there is currently no consensus. 15 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 In our study, most clinical presentations or outcomes, underlying medical conditions, and coinfection variables demonstrated no statistically significant association with the detection of HRSV subgroups in patients. In our study, persons aged <5 years with HRSV A‐related illness were more likely be coinfected with S. pneumoniae when compared with HRSV B. While the literature does not report on an association between S. pneumoniae and HRSV subgroup‐specific infection, children hospitalized with HRSV infection and S. pneumoniae codetection in the nasopharynx have demonstrated worse clinical severity than those infected with HRSV only. 46 , 47 , 48

We identified four circulating HRSV genotypes over the observation period, HRSV A: NA1 and ON1 and HRSV B: BA9 and BA10. Following global trends, the emergent HRSV A genotype, ON1, showed a gradual increase in prevalence from 5.6% (3/53) in 2012 to 81.5% (22/27) in 2015. 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 49 A complete replacement of the previously dominant HRSV A, NA1 genotype was not found as noted in several studies. 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 Three separate lineages of the ON1 genotype 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 are circulating, and studies have suggested that the 1.1 lineage emerged prior to the other lineages. Circulation of the 1.1 lineage was also previously observed in South Africa in 2011–2012. 10 , 12 Here, we demonstrated the cocirculation of all three ON1 lineages in South Africa, as observed in most other countries that have conducted HRSV surveillance over two consecutive seasons since ON1 emergence. 12 As with HRSV subgroups, prior studies have shown a spectrum of clinical outcomes associated with ON1 genotype infection. 4 , 8 , 15 , 38 , 44 We found no association with clinical outcomes when comparing NA1 with ON1 genotypes. HRSV B genotype BA10 showed a gradual shift in prevalence from 33.3% (2/6) in 2012 to 78.6% (11/14) in 2015, albeit using limited study numbers.

This study was limited by only including individuals that were admitted to two sentinel SRI surveillance sites in the KwaZulu‐Natal and North‐West Provinces of South Africa. It is therefore possible that our study may not be an accurate representation of the general South African population or HRSV subgroup and genotype prevalence. In addition, only 23% (175/772) of the HRSV‐positive samples were genotyped. We therefore may not have shown the full diversity of HRSV genotypes circulating within the country. Furthermore, when we reviewed subgroup/genotype prevalence data available from other South African surveillance programs, the dominance patterns were the same (data not shown). Restricted study sampling may also have limited our ability to find statistically significant associations between measured variables and HRSV genotypes in all age groups and with HRSV subgroups in the ≥5‐year age group. It is therefore recommended that future studies in South Africa continue to follow HRSV prevalence and diversity trends in all age groups to ascertain the target populations for candidate vaccines. In these studies, a greater emphasis should be placed on sampling broadly across the population and genotyping a larger proportion of the HRSV‐positive samples.

5. CONCLUSION

This study builds upon our understanding of the clinical and epidemiological relevance of HRSV, its subgroups, and genotypes among patients hospitalized with SRI in South Africa. Changes in HRSV diversity over the study period demonstrated the presence and dominance of similar subgroups and genotypes found elsewhere in the world. This may suggest that no region‐specific considerations will be required when selecting appropriate vaccine target strains. Furthermore, we showed that the youngest age group (<6 months), which demonstrated the highest HRSV infection prevalence (47%) would benefit most from HRSV vaccine implementation, similar to findings from previous studies from South Africa (55%). 2 , 50 While no significant differences were found between the clinical outcomes and underlying illnesses associated with HRSV A and B infection or between HRSV A genotypes NA1 and ON1, a statistically significant association between HRSV A and S. pneumoniae coinfection in young children warrants further investigation of disease outcomes.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Cheryl Cohen has received funding to her institution from Sanofi Pasteur, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, and has received funding to attend a meeting from Parexel. Dr. Dawood reports personal fees from Pfizer‐South Africa and conference attendance sponsorship from MSD‐South Africa, Pfizer‐South Africa, and Biomiereux‐South Africa.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ziyaad Valley‐Omar: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources. Stefano Tempia: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision. Orienka Hellferscee: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; project administration. Sibongile Walaza: Conceptualization; project administration. Ebrahim Variava: Conceptualization. Halima Dawood: Conceptualization; project administration. Kathleen Kahn: Conceptualization; project administration. Meredith McMorrow: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; supervision. Marthi Pretorius: Conceptualization; methodology. Senzo Mtshali: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration. Ernest Mamorobela: Investigation. Nicole Wolter: Conceptualization; project administration. Marietjie Venter: Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; supervision. Anne von Gottberg: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration; supervision. Cheryl Cohen: Conceptualization; project administration; resources; supervision.

PRESENTATION OF DATA

Data from this study were presented as a poster at the 11th International Respiratory Syncytial Virus Symposium, November 2018, Ashville, NC, USA (Abstract number: ARSVA0113).

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/irv.12905.

Supporting information

Table S1. Factors associated with HRSV subgroups among patients aged ≥5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong Hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015.

Figure S1. Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) seasonality in South Africa, 2012–2015. Bar graph showing monthly proportions of HRSV‐positive patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the SRI surveillance teams in Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong Hospitals for their contributions to this study. This work was supported by funds from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia; cooperative agreements 5U19GH000622 and 5U51IP000528.

Valley‐Omar Z, Tempia S, Hellferscee O, et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus diversity and epidemiology among patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness in South Africa, 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2022;16(2):222-235. doi: 10.1111/irv.12905

Funding information Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Grant/Award Numbers: 5U19GH000622, 5U51IP000528

Contributor Information

Ziyaad Valley‐Omar, Email: z.valley-omar@uct.ac.za.

Cheryl Cohen, Email: cherylc@nicd.ac.za.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Sequences with the following accession numbers MN516831 to MN517111 were uploaded to GenBank.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shi T, McAllister DA, O'Brien KL, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):946‐958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moyes J, Cohen C, Pretorius M, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus‐associated acute lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations among HIV‐infected and HIV‐uninfected South African children, 2010‐2011. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(Suppl 3):S217‐S226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moyes J, Walaza S, Pretorius M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in adults with severe acute respiratory illness in a high HIV prevalence setting. J Infect. 2017;75(4):346‐355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eshaghi A, Duvvuri VR, Lai R, et al. Genetic variability of human respiratory syncytial virus A strains circulating in Ontario: a novel genotype with a 72 nucleotide G gene duplication. PloS One. 2012;7(3):e32807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khor CS, Sam IC, Hooi PS, Chan YF. Displacement of predominant respiratory syncytial virus genotypes in Malaysia between 1989 and 2011. Infection, Genetics and Evolution: Journal of Molecular Epidemiology and Evolutionary Genetics in Infectious Diseases. 2013;14:357‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peret TC, Hall CB, Hammond GW, et al. Circulation patterns of group A and B human respiratory syncytial virus genotypes in 5 communities in North America. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(6):1891‐1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trento A, Casas I, Calderón A, et al. Ten years of global evolution of the human respiratory syncytial virus BA genotype with a 60‐nucleotide duplication in the G protein gene. J Virol. 2010;84(15):7500‐7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agoti CN, Otieno JR, Gitahi CW, Cane PA, Nokes DJ. Rapid spread and diversification of respiratory syncytial virus genotype ON1, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(6):950‐959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirano E, Kobayashi M, Tsukagoshi H, et al. Molecular evolution of human respiratory syncytial virus attachment glycoprotein (G) gene of new genotype ON1 and ancestor NA1. Infection, Genetics and Evolution: Journal of Molecular Epidemiology and Evolutionary Genetics in Infectious Diseases. 2014;28:183‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valley‐Omar Z, Muloiwa R, Hu NC, Eley B, Hsiao NY. Novel respiratory syncytial virus subtype ON1 among children, Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(4):668‐670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoshihara K, le MN, Nagasawa K, et al. Molecular evolution of respiratory syncytial virus subgroup A genotype NA1 and ON1 attachment glycoprotein (G) gene in central Vietnam. Infection, Genetics and Evolution: Journal of Molecular Epidemiology and Evolutionary Genetics in Infectious Diseases. 2016;45:437‐446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duvvuri VR, Granados A, Rosenfeld P, Bahl J, Eshaghi A, Gubbay JB. Genetic diversity and evolutionary insights of respiratory syncytial virus A ON1 genotype: global and local transmission dynamics. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):14268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Esposito S, Piralla A, Zampiero A, et al. Characteristics and their clinical relevance of respiratory syncytial virus types and genotypes circulating in northern Italy in five consecutive winter seasons. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0129369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trento A, Viegas M, Galiano M, et al. Natural history of human respiratory syncytial virus inferred from phylogenetic analysis of the attachment (G) glycoprotein with a 60‐nucleotide duplication. J Virol. 2006;80(2):975‐984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Midulla F, Nenna R, Scagnolari C, et al. How respiratory syncytial virus genotypes influence the clinical course in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2019;219(4):526‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mejias A, Rodriguez‐Fernandez R, Peeples ME, Ramilo O. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccines: are we making progress? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(10):e266‐e269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Niekerk S, Venter M. Replacement of previously circulating respiratory syncytial virus subtype B strains with the BA genotype in South Africa. J Virol. 2011;85(17):8789‐8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reiche J, Schweiger B. Genetic variability of group A human respiratory syncytial virus strains circulating in Germany from 1998 to 2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1800‐1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pretorius MA, van Niekerk S, Tempia S, et al. Replacement and positive evolution of subtype A and B respiratory syncytial virus G‐protein genotypes from 1997‐2012 in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(Suppl 3):S227‐S237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tempia S, Walaza S, Moyes J, et al. The effects of the attributable fraction and the duration of symptoms on burden estimates of influenza‐associated respiratory illnesses in a high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2013–2015. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2018;12(3):360‐373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pretorius MA, Madhi SA, Cohen C, et al. Respiratory viral coinfections identified by a 10‐plex real‐time reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction assay in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory illness—South Africa, 2009–2010. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(Suppl 1):S159‐S165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu A, Colella M, Tam JS, Rappaport R, Cheng SM. Simultaneous detection, subgrouping, and quantitation of respiratory syncytial virus A and B by real‐time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(1):149‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van de Pol AC, Wolfs TF, van Loon AM, et al. Molecular quantification of respiratory syncytial virus in respiratory samples: reliable detection during the initial phase of infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(10):3569‐3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sullender WM, Sun L, Anderson LJ. Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus genetic variability with amplified cDNAs. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(5):1224‐1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peret TC, Hall CB, Schnabel KC, Golub JA, Anderson LJ. Circulation patterns of genetically distinct group A and B strains of human respiratory syncytial virus in a community. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 9):2221‐2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792‐1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post‐analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312‐1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Welliver RC Sr. Temperature, humidity, and ultraviolet B radiation predict community respiratory syncytial virus activity. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(11 Suppl):S29‐S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lam TT, Tang JW, Lai FY, et al. Comparative global epidemiology of influenza, respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza viruses, 2010–2015. J Infect. 2019;79(4):373‐382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rha B, Dahl RM, Moyes J, et al. Performance of surveillance case definitions in detecting respiratory syncytial virus infection among young children hospitalized with severe respiratory illness—South Africa, 2009–2014. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2019;8(4):325‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Anderson EJ, Carbonell‐Estrany X, Blanken M, et al. Burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus disease among 33–35 weeks' gestational age infants born during multiple respiratory syncytial virus seasons. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(2):160‐167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vizcarra‐Ugalde S, Rico‐Hernández M, Monjarás‐Ávila C, et al. Intensive care unit admission and death rates of infants admitted with respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(11):1199‐1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mazur NI, Bont L, Cohen AL, et al. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection with viral coinfection in HIV‐uninfected children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(4):443‐450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pretorius MA, Tempia S, Walaza S, et al. The role of influenza, RSV and other common respiratory viruses in severe acute respiratory infections and influenza‐like illness in a population with a high HIV sero‐prevalence, South Africa 2012–2015. Journal of Clinical Virology: The Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2016;75:21‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Varga SM, Braciale TJ. The adaptive immune response to respiratory syncytial virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;372:155‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sriskandan S, Shaunak S. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in an adult with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(6):1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murphy D, Rose RC 3rd. Respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia in a human immunodeficiency virus‐infected man. Jama. 1989;261(8):1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fodha I, Vabret A, Ghedira L, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in hospitalized infants: association between viral load, virus subgroup, and disease severity. J Med Virol. 2007;79(12):1951‐1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hornsleth A, Klug B, Nir M, et al. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus disease related to type and genotype of virus and to cytokine values in nasopharyngeal secretions. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(12):1114‐1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laham FR, Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, et al. Clinical profiles of respiratory syncytial virus subtypes A and B among children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(8):808‐810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martinello RA, Chen MD, Weibel C, Kahn JS. Correlation between respiratory syncytial virus genotype and severity of illness. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(6):839‐842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McConnochie KM, Hall CB, Walsh EE, Roghmann KJ. Variation in severity of respiratory syncytial virus infections with subtype. J Pediatr. 1990;117(1 Pt 1):52‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McIntosh ED, De Silva LM, Oates RK. Clinical severity of respiratory syncytial virus group A and B infection in Sydney, Australia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12(10):815‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Papadopoulos NG, Gourgiotis D, Javadyan A, et al. Does respiratory syncytial virus subtype influences the severity of acute bronchiolitis in hospitalized infants? Respir Med. 2004;98(9):879‐882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Walsh EE, McConnochie KM, Long CE, Hall CB. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection is related to virus strain. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(4):814‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brealey JC, Chappell KJ, Galbraith S, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization of the nasopharynx is associated with increased severity during respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. Respirology. 2018;23(2):220‐227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith CM, Sandrini S, Datta S, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus increases the virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae by binding to penicillin binding protein 1a. A new paradigm in respiratory infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(2):196‐207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weinberger DM, Klugman KP, Steiner CA, Simonsen L, Viboud C. Association between respiratory syncytial virus activity and pneumococcal disease in infants: a time series analysis of US hospitalization data. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abadom TR, Smith AD, Tempia S, Madhi SA, Cohen C, Cohen AL. Risk factors associated with hospitalisation for influenza‐associated severe acute respiratory illness in South Africa: a case‐population study. Vaccine. 2016;34(46):5649‐5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588‐598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Factors associated with HRSV subgroups among patients aged ≥5 years, hospitalized with severe respiratory illness, Edendale and Klerksdorp‐Tshepong Hospitals, South Africa, 2012–2015.

Figure S1. Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) seasonality in South Africa, 2012–2015. Bar graph showing monthly proportions of HRSV‐positive patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences with the following accession numbers MN516831 to MN517111 were uploaded to GenBank.