Abstract

Post-stroke depression (PSD) is the most common non-cognitive neuropsychiatric complication after stroke, and about a third of patients with stroke have depression. Although a great deal of effort has been made to treat PSD, the efficacy thereof has not been satisfactory, due to the complex pathological mechanism underlying PSD. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) theory, PSD is considered to be a combination of “stroke” and “Yu Zheng.” The holistic, multi-drug, and multi-objective nature of TCM is consistent with the treatment concept of systems medicine for PSD. TCM has a very long history of being used to treat depression, and various TCM prescriptions have been clinically proven to be effective in improving depression. Among the numerous prescriptions for treating depression, Shugan Jieyu capsule (SG) is one of the classic prescriptions. Additionally, clinical studies have increasingly confirmed that using SG alone or in combination with Western medicine can significantly improve the psychiatric symptoms of PSD patients. Here, we reviewed the mechanism of antidepressant action of SG and its targets in PSD pathologic systems. This review provides further insights into the pharmacological mechanism, drug interaction, and clinical application of TCM prescriptions, as well as a basis for the development of new drugs to treat PSD.

Keywords: Pharmacology, post-stroke depression, shugan jieyu capsule, traditional Chinese medicine, treatment

Introduction

Post-stroke depression (PSD) is a serious psychiatric condition that develops after stroke, and its prevalence is related to the time point after stroke. The cumulative incidence of PSD within 5 years after stroke is 39–52%, which usually occurs in the first month after stroke, and then gradually increases (Ayerbe et al., 2013).

The clinical manifestations of PSD are depression, guilt or low self-worth, sleep disturbances, fatigue, inattention, and suicidal tendencies (Das and Rajanikant, 2018). PSD has significant negative effects on physical, cognitive, and functional rehabilitation, and has become a serious human, social, and public health problem, reducing the survival rate and delaying the recovery of patients after stroke (Robinson and Jorge, 2016).

The pathophysiological mechanism of PSD is complex and multi-factorial (Ezema et al., 2019). Despite many clinical and basic studies, the pathophysiological mechanism of PSD remains incompletely elucidated. Currently, it is believed that the mechanism that may lead to PSD mainly include (i) dysregulation of the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal (HPA) axis (pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate the HPA axis to release glucocorticoids associated with PSD) (Otte et al., 2016; Robinson and Jorge, 2016); (ii) glutamate-mediated toxicity mechanism (in stroke patients, a higher serum glutamate level may be involved in PSD through cerebral infarction formation) (Cheng et al., 2014; Gruenbaum et al., 2020); (iii) monoamine transmissions (PSD may be associated with lower levels of biological monoamines, i.e., serotonin [5-HT], norepinephrine [NE], and dopamine [DA], in the central nervous system [CNS]); (iv) neurotrophic factor dysregulation (brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]-deficiency contributes to the pathophysiology of PSD) (Zhang and Liao, 2020); (v) increased inflammatory cytokine levels (interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, and interferon γ [IFN-γ]) are important factors leading to PSD (Li J. et al., 2014). In addition, intestinal microflora disorder, serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene polymorphism, and mitochondrial dysfunction may also be involved in the pathophysiology of PSD (Jiang et al., 2015; Bansal and Kuhad, 2016).

Clinically commonly used anti-PSD drugs include tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective 5-HT-reuptake inhibitors, 5-HT‒NE reuptake inhibitors, and specific serotonergic antidepressants. However, these CNS-orientated, single-target, and conventional antidepressants are insufficient and far from ideal for PSD therapy (Tao et al., 2021). On the other hand, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been used to treat depression for thousands of years. The holistic, multi-drug, and multi-objective nature of TCM is highly consistent with the treatment concept of systems medicine in PSD.

In our mini-review, we will explain the pathogenesis of PSD from the perspective of TCM theory, briefly review the TCM prescriptions for the treatment of PSD, introduce in detail the composition of the classic PSD prescription Shugan Jieyu capsule (SG) and its active ingredients, and consider the pathology of PSD, in order to provide a deeper understanding of the pharmacological mechanism, drug interaction, and clinical application of TCM prescriptions.

PSD According to TCM

PSD is a comorbidity of “stroke” and “Yu Zheng”. Based on the theory of “the identity of the collateral and vascular system,” it is concluded that cerebral collateral stasis (blood collateral stasis)/cerebral vascular occlusion-caused brain tissue loss is the key pathogenesis of stroke. Qi collaterals (络) are related to the neuroendocrine functions in modern medicine, and neuroendocrine functions are associated with the occurrence of depression. Therefore, it is speculated that there may also be correlation between qi collaterals and Yu Zheng. In the meridians, the “meridian qi” of the circulation around the body is disseminated to the whole body through qi collateral channels, which play the roles of nourishing the viscera, transmitting information, defense and protection, and regulating and controlling the function of the whole body.

The “meridian qi circulation system” is quite consistent with the neuroendocrine regulation system of Western medicine (Loubinoux et al., 2012). Yu Zheng patients have suffered an emotional injury, resulting in abnormal changes in qi, leading to stagnation of collateral qi, and inhibition of blood flow. Qi and blood deficiency of collaterals and loss of nourishment via brain collaterals result in emotional depression, lack of interest and/or pleasure, and other mental symptoms. PSD, as a “stroke” and “Yu Zheng” comorbidity, involves qi and collateral disorders, and blood and collateral obstruction. The main characteristics of the treatment of collateral diseases is “Activating meridians”, among which regulating the Zang-Fu organs is the fundamental treatment.

PSD is caused by the interaction of liver qi stagnation and blood stasis after stroke. On the basis of liver qi stagnation, PSD may combine with heart, spleen, kidney deficiency and phlegm stasis. Some scholars also believe that PSD is depression caused by stroke, which is based on deficiency of kidney essence, deficiency of qi, blood and Yin and Yang of Zang-Fu organs, and marked by qi stagnation, blood stasis and phlegm turbidity. The pathogenesis is liver qi stagnation, and the key is spleen failure. The pathogenesis can be transformed into each other, and is mixed with deficiency and reality.

TCM in PSD Treatment

The application of classical prescriptions of TCM to treat diseases has a long history. Ancient literature contains many therapeutic prescriptions of Yu Zheng. Modern doctors and scholars use classical prescriptions to treat PSD, and continue to perform clinical and scientific research to provide a basis for the development of syndrome differentiation and treatment by classical prescriptions.

Chaihu Shugan San (CSS) is a classic and effective antidepressant TCM that has been used in China for thousands of years. CSS plays an antidepressant role by regulating the BDNF/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway in the hippocampus and frontal cortex (Yan et al., 2020). Buyang Huanwu decoction ameliorates PSD by promoting neurotrophic pathway-mediated neuroprotection and neurogenesis (Luo et al., 2017). Xiaoyao formula (XYF) is a well-known Chinese herbal formula for treating “Liver Stagnation and Spleen Deficiency” syndrome. The beneficial effects of XYF on PSD with few adverse events have been shown by studies in China (Jin et al., 2018). Huanglian-Wendan decoction (HWD) has antidepressant activity with hepatoprotection in rat models of chronic, unpredictable, mild stress, which was associated with its anti-inflammation action both peripherally and centrally. The inhibitory modulation of NF-κB and nucleotide binding oligomerization domain 3-like receptor (NLRP3) inflammasome activation by HWD may mediate its antidepressant action (Jia et al., 2018). Chaihu Jia Longgu Muli decoction (CLMD) is widely used in the treatment of PSD in China. Current evidence suggests that CLMD is more effective and safer for the treatment of PSD than Western oral antidepressants (Wan et al., 2021). CLMD can regulate HPA axis dysfunction by preventing dopaminergic and serotonergic transmission in the prefrontal cortex (Wan et al., 2021) and upregulating BDNF expression to alleviate the depression-like state induced by chronic stress (Chen et al., 2020). Tongqiao Huoxue decoction (TQHXD) exerts an apparent protective effect on glutamate-damaged neurocytes in terms of proliferation activity and membrane permeability, which shows its potential to treat PSD (Wang et al., 2010). As the expression levels of BDNF is decreased in PSD, Yinao Jieyu recipe could inhibit the progress of PSD (Li et al., 2015a).

The results of a clinical controlled study in China suggested that Jieyu Huoxue Decoction can not only relieve PSD, but also improve neurological impairment (Feng et al., 2004). Xingnao Jieyu (XNJY) decoction can treat PSD through multiple mechanisms (Fan et al., 2012). For example, XNJY promotes BDNF expression by regulating the BDNF/ERK/CREB signaling pathway (Li et al., 2018). In addition, XNJY upregulates synaptotagmin expression in hippocampi and exerts antidepressant effects (Yan et al., 2013). Peng et al. suggested that Wuling capsules have a certain antidepressant effect, and can be used as a treatment option for PSD (Peng et al., 2014).

SG is a TCM that is used to improve cognitive impairment and emotional disorders caused by PSD (Yao et al., 2020). Emerging studies have demonstrated that SG alone or combined with Western antidepressants has a satisfactory therapeutic effect on PSD, with no obvious adverse reactions. Below, we will elaborate on the active constituents of SG and the pharmacological mechanism of SG in treating PSD.

Molecular Mechanism of Action of SG Antidepressants

SG is mainly composed of Hypericum perforatum and Acanthopanax. Hypericum perforatum has the functions of clearing heat and detoxifying, soothing the mind, cooling the blood, and nourishing Yin. It has a long history of use in treating mental diseases and has been recognized in the modern Chinese medicine circle. Acanthopanax has the effect of replenishing qi and invigorating the brain. It is commonly used to treat depression, neurosis, and neurasthenia. In the treatment process, these two compounds cooperate to produce a calming and tranquilizing anti-depressant effect.

Hypericum perforatum is a perennial herb with erect stems and many branches, axillary branches, dense opposite leaves that are elliptic to linear, 1–2-cm long, and 3–9-mm wide. Flowers are born at the stem apex or branch tip, with cymes, five lanceolate sepals, and black glandular spots at the margin. Its taste is spicy and slightly bitter. The whole plant contains phenylpropane, flavonol derivatives, flavonoids (diflavones), proanthocyanidins, oxyxanthanone, phloroglactil (hypericin and its homologue pseudohypericin), hypericin and its derivatives, and some precursors (prohypericin, hypericin auxiliary dehydrodione). The content of hypericin is lower in young plants, higher in the flowering period, and lowest in the stems. It also contains anthraphenol compounds, such as emodin anthraphenol. Its flavonoid content is 3.35–7.4%, mainly hyperoside and rutin, but also quercetin, isoquercitrin, and miquelianin. In addition, a new antibacterial substance, novlimanin, which is a bicyclic tetraketone compound containing four isopentene chains, was isolated from an acetone extract of the plant (Cirak et al., 2010; Verjee et al., 2019).

Acanthopanax is a deciduous shrub that grows to 2 m tall and has stems that are usually dense, with slender barbs. Its medicinal ingredients mainly come from its roots, rhizomes, or stems and leaves. The rhizome is irregularly cylindrical, 1.4–4.2 cm in diameter. The root is cylindrical, 0.3–1.5 cm in diameter. It is slightly fragrant and tastes mildly spicy and bitter. Modern pharmacological studies have found that Acanthopanax contains glycosides, polysaccharide, fatty acids, quinones, amino acids and trace elements. The main glycosides are Acanthopanax glycosides A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Polysaccharides mainly include glucose, sucrose, alkali-soluble polysaccharide and water-soluble polysaccharide. Fatty acids and quinones mainly include methyl oleate, ethyl oleate, 10, -octadecadienoic acid, 10, -octadecadienoic acid, ethyl ester, mymyritic acid, palmitic acid, 9, 11-octadecadienoic acid, hexadecadienoic acid (Li et al., 2021).

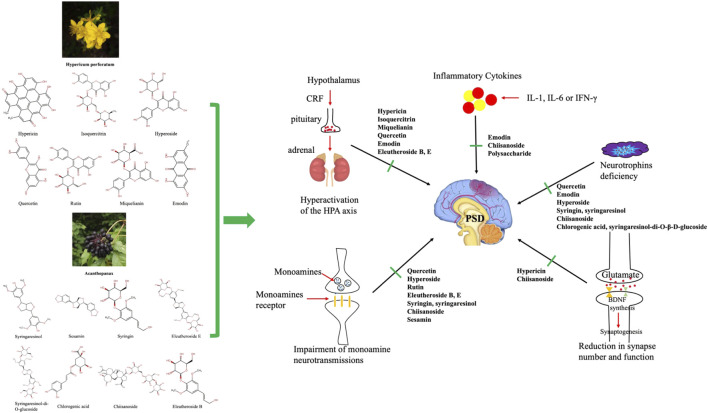

Through a literature review, we found that a variety of chemical components of the two TCMs may play a role in the treatment of PSD by regulating the HPA axis, glutamate transmission, monoamine transmission, BDNF, and other mechanisms (Table 1; Figure 1). Next, we explore the pharmacological mechanisms of the chemical components of these two compounds at the molecular level, from several pathogenically mechanisms involved in PSD.

TABLE 1.

Herbal constituents in Shugan Jieyu Capsule (SG) that produce antidepressant-like activities in animal models or cells.

| SC composition | Herbal constituents | Mechanism of action | Models | Administration dosage | Treatment time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypericum perforatum | Hypericin | HPA axis/Glutamate transmission | Male CD rats | 0.2 mg/kg | 8 weeks | Butterweck et al. (2001) |

| Isoquercitrin | HPA axis | Male CD rats | 0.6 mg/kg | 2 weeks | Butterweck et al. (2004) | |

| Miquelianin | HPA axis | Male CD rats | 0.6 mg/kg | 2 weeks | Butterweck et al. (2004) | |

| Quercetin | Monoamine transmissions/HPA/BDNF | Wistar rats | 10 mg/kg | 60 min | Herraiz and Guillén, 2018; Kawabata et al., 2010 | |

| Emodin | BDNF/the HPA axis | CUMS rats | 40 or 80 mg/kg | 6 weeks | Li et al., 2014b | |

| Anti-inflammatory response | CUMS rats | 80 mg/kg | 2 weeks | Zhang et al. (2021) | ||

| Hyperoside | BDNF | Male SD rats | 10 mg/kg | 34 days | Gong et al. (2017) | |

| Monoamine transmissions | CUMS rats | 3.75 mg/kg | 24 h | Orzelska-Górka et al. (2019) | ||

| Rutin | Monoamine transmissions | Male Swiss mice | 3.0 mg/kg | 4 days | Machado et al., 2008 | |

| Acanthopanax | Eleutheroside B, E | HPA axis | Male ICR mice | - | 14 days | Jung et al. (2013) |

| Monoamine transmissions | Male Kunming mice | 15 mg/kg | 21 days | Qi et al. (2020) | ||

| Syringin, syringaresinol | Monoamine transmissions | Male Kunming mice | − | 7 days | Jin et al. (2013) | |

| BDNF | PC12 cell | − | 12 h | Wu et al. (2013) | ||

| Chiisanoside | Monoamine transmissions/Anti-inflammatory response/BDNF/Glutamate transmission | Male ICR mice | 5.0 mg/kg | 7 days | Bian et al. (2018) | |

| Polysaccharide | Anti-inflammatory response | Male Kunming mice | 300 mg/kg | 14 days | Han et al., 2016 | |

| Chlorogenic acid, syringaresinol-di-O-β-D-glucoside | BDNF | Male Sprague Dawley rats | 40 mg/kg and 32 mg/kg | 7 days | Miyazaki et al. (2020) | |

| Sesamin | Monoamine transmissions | Male rats of the Lewis strain | 30 mg/kg | 14 days | Fujikawa et al., 2005 |

FIGURE 1.

Several divergent systems are involved in the pathophysiology of post-stroke depression. The active ingredients (the 2D structures on the left) in Shugan Jieyu capsules may act on the pathophysiological system of the central nervous system, including the hypothalamus‒pituitary‒adrenal axis, monoamine neurotransmission, neurotrophins, inflammatory factor release, and synapse number and function as shown.

HPA Axis

There is a neuro-hormone‒inflammatory interaction between the HPA axis and the CNS, endocrine system, or immune system, which forms an integrated network at the basis of PSD pathogenesis. Stress leads to activation of the HPA axis, which is typically manifested by high levels of glucocorticoids, leading to depressive symptoms by impairing neuronal survival and neurogenesis (Keller et al., 2017). Abnormal inflammatory responses and higher glucocorticoid levels are associated with PSD, and increased inflammation and dysregulation of the HPA may increase the risk of PSD through multiple mechanisms (Villa et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2018). Monoamine antidepressants not only reverse stress-induced hyperactivity of the HPA axis, but also attenuate the inflammatory response by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in activated microglia (Simões et al., 2019). Similarly, agents that eliminate inflammatory effects may exert antidepressant activity in animal models through the interaction between the immune system and the CNS (Zunszain et al., 2011). In addition, antidepressant agents directly acting on the HPA axis, such as glucocorticoid receptor antagonists, can also be effective as antidepressants by blocking the receptor activity and terminating the hormone over-secretion caused by stress-induced HPA axis hyperactivity (Menke, 2019).

The effect of hypericin (the active component of Hypericum perforatum) on gene expression may be involved in the regulation of the HPA axis. Butterweck et al. demonstrated that, after 8 weeks of intragastric administration of hypericin (0.2 mg/kg), corticotropin-releasing hormone and 5-HT receptor 1A receptor mRNA was significantly reduced in rats’ hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (Butterweck et al., 2001).

Flavonoids (isoquercitrin and miquelianin) are also active constituents of Hypericum perforatum that modulate HPA axis function. Isoquercitrin and miquelianin given daily by gavage for 2 weeks significantly down-regulated circulating plasma levels of adreno-corticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone in rats (Butterweck et al., 2004).

Eleutheroside B and E are ethanol extracts of Acanthopanax. In mice with stress-induced behavioral alterations, administration of eleutheroside B and E could potently activate the HPA axis to decrease the elevated corticosterone concentration and relieve major depressive disorder (Jung et al., 2013). Qi et al. (2020) also drew a similar conclusion in depression-model mice: eleutheroside could significantly shorten the tail suspension test, and improve the contents of DA, NE, and 5-HT in the brain of mice.

Glutamate Transmission

Changes in central glutamate neurotransmission are related to the pathophysiology of depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants (Duman et al., 2019). In stroke patients, the correlation between higher serum glutamate levels, infarct volume, and depression suggests that glutamate may be involved in PSD through stroke formation (Chen, 2014). N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor channel blockers and acetylcholine muscarinic receptor antagonists enhance glutamate transmission, and then increase BDNF release and synaptic function, so as to reverse stress-induced synaptic abnormalities rapidly (Burgdorf et al., 2013). Among them, ketamine, as an NMDA receptor antagonist, has been proven to produce rapid antidepressant effects (Murrough et al., 2013).

Inhibition of glutamate release is also one of the potential mechanisms of hypericin’s antidepressant effects. Hypericin has been reported to inhibit neuroglutamate release in the rat cortex by reducing voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx and mitogen-activated protein kinase activity (Chang and Wang, 2010).

Chiisanoside, a triterpenoid saponin extracted from Acanthopanax, may have antidepressant activity (Bian et al., 2018). In depression-model mice, it has been suggested that chiisanoside effectively increases the DA and γ-aminobutyric acid levels. Chiisanoside administration could also reduce serum IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels. Moreover, the changes in oxidative stress-related indicators were effectively improved. Additionally, chiisanoside inhibited TrkB, BDNF, and NF-κB in the hippocampus (Bian et al., 2018). Therefore, chiisanoside exhibited significant antidepressant-like effects via multiple pharmacological mechanisms.

Monoamine Transmissions

Monoamine neurotransmission injury may be involved in the pathological mechanism of PSD. Ischemic injury of amine-containing axons from the brainstem to the left cerebral cortex may lead to decreased 5-HT and NE synthesis in the frontal, temporal, and basal ganglia limbic regions, leading to PSD. Monoamine-reuptake transporters of 5-HT and NE are the main targets of antidepressant drugs. Monoamine-based inhibitors enhance 5-HT or NE transmission by different mechanisms, leading to altered discharge activity in the dorsal raphe nucleus or locus coeruleus, thereby improving PSD (Araragi et al., 2013).

Quercetin is one of the flavonoids in Hypericum perforatum. Herraiz et al. reported that quercetin and its glycosides can inhibit the activity of monoamine oxidase A, and could be a potential antidepressant for treating PSD through its antioxidant activity (Herraiz and Guillén, 2018). Quercetin also significantly inhibited the increase of plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels by inhibiting the expression of corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA (Kawabata et al., 2010). In a focal cerebral ischemia model, quercetin could activate the BDNF‒TrkB‒PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Therefore, quercetin’s antidepressant-like activity is related to its ability to modulate levels of BDNF (Yoshino et al., 2011).

The antidepressant activity of hyperoside was evaluated by Orzelska-Górka et al. They demonstrated that hyperoside was able to reverse depressive symptoms in the forced swimming test and sucrose-preference test in rats exposed to chronic mild stress. Further pharmacological studies suggested that this antidepressant effect may be mediated in part by regulation of the central monoamine neurotransmitter system and increased levels of BDNF (Cai et al., 2017). This result may facilitate further study of the antidepressant mechanism of this potential treatment option (Orzelska-Górka et al., 2019).

Rutin, a diglycoside flavonol, is extensively found in plants, including Hypericum perforatum. It has therapeutic potential for depression: on the one hand, rutin prevented the overexpression of inflammatory biomarkers, such as cyclooxygenase-2, IL-8, and inducible nitric oxide synthase, while on the other hand, it increased the availability of 5-HT, NE, and DA in the synaptic cleft (Pathak et al., 2013; Souza et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021).

Syringin and syringaresinol are the main active ingredients of Acanthopanax. Jin et al. suggested that syringin and syringaresinol could significantly elevate the levels of 5-HT, NE, and DA in the whole brain of mice. In addition, levels of CREB protein expression were also upregulated by syringin and syringaresinol pre-treatment of depression-model mice. Therefore, the antidepressant mechanism of syringin and syringaresinol may be mediated via the central monoaminergic neurotransmitter system and CREB protein expression. Administration of syringin and syringaresinol may be beneficial for patients with depressive disorders (Jin et al., 2013). In terms of corticosterone-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells, syringin and syringaresinol could increase BDNF mRNA levels and CREB protein expression, and increased PC12 cell viability, which may be mechanisms accounting for the in vivo antidepressant activity of Acanthopanax (Wu et al., 2013).

Neurotrophins

BDNF is the most abundant and widely distributed neurotrophic factor in the CNS. It plays a crucial role in the growth and differentiation of the nervous system. The level of BDNF decreased in both the brain of patients with depression and in animal models of depression (Luo et al., 2013). In addition, increasing clinical and experimental evidence has shown that changes in BDNF levels are associated with beneficial therapeutic activities of antidepressants (Thompson Ray et al., 2011). Therefore, BDNF is considered a possible target for antidepressants.

Emodin is one of the active chemical constituents of Hypericum perforatum. Previous studies have shown that emodin can protect the brain from the excitatory toxicity of glutamate by reducing its release (Bonaterra et al., 2020). Emodin has recently been reported to oppose chronic, unpredictable, mild stress-induced depressive-like behavior in mice by upregulating the levels of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor and BDNF (Li M. et al., 2014).

In addition, emodin also had anti-inflammatory activities: it prevented depressive behaviors in DeS rats by inhibiting microglial activation, down-regulating IL-1β, TNF-α, and 5-lipoxygenase expression (Wang et al., 2018). Moreover. Zhang et al. demonstrated that emodin inhibited excess inflammatory response by targeting miR-139-5p/5-lipoxygenase (Zhang et al., 2021). Hyperoside increased the expression of BDNF in the hippocampus of CUMS rats, but it did not affect the level of plasma corticosterone (CORT), so it may be one of the potential reasons for the antidepressant effect of Hypericum perforatum (Gong et al., 2017).

Recent studies have identified chlorogenic acid and syringaresinol-di-O-β-D-glucoside (SYG) as bioactive components of Acanthopanax. Chlorogenic acid and SYG increases hippocampal BDNF protein levels, activates hippocampal BDNF signaling, therefore, the anti-depressive effects of Acanthopanax may be through the regulation of BDNF expression and its downstream signaling (Miyazaki et al., 2020).

Sesamin is an active integrant of Acanthopanax and has been identified as a new anti-metalloproteinases inhibitor (Załuski et al., 2016). In rotenone-induced Parkinsonian rats, Baluchnejadmojarad et al. demonstrated that sesamin could provide cytoprotective effects on DA cells in the substantia nigra and relieve depression in Parkinson disease (Baluchnejadmojarad et al., 2017).

Inflammatory Cytokines

A large number of studies have shown that cytokines are involved in both the inflammatory response of acute ischemic stroke and in depression, and thus may play a role in the occurrence of PSD. Inflammatory factors, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IFN-γ are important factors leading to postmenopausal depression (Wang et al., 2013). In addition, other inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-8, IL-18, and hypersensitive-C-reactive protein have also been found to play an important role in the pathogenesis of PSD (Cheng et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020).

Polysaccharides, derived as the aqueous extract of Acanthopanax, are its major active ingredient. Previous studies have shown that polysaccharides have immune regulatory activity and inflammation inhibitory activity in animal models (Chen et al., 2011). Polysaccharides could decrease lipopolysaccharide-induced secretion of inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α and NF-κB (Han et al., 2014), demonstrating the potential of polysaccharides to treat PSD through anti-inflammatory actions.

Clinical Application of SG in the Treatment of PSD

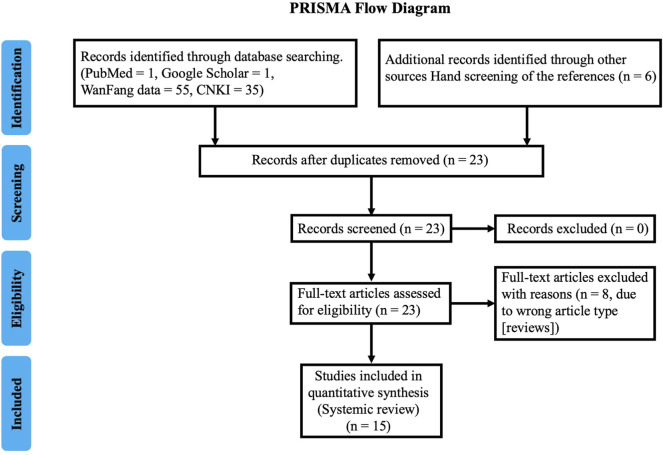

A systemic literature search was performed for articles using PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane, CNKI (https://www.cnki.net/), Weipu (http://www.cqvip.com/), and Wanfang (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/index.html) database for the period 1990–2021. The search term “Shugan Jieyu Capsule” and “Post-Stroke Depression” were used. The quality of the added cases was assessed by two reviewers independently (ZB and XD) using the Joanna Briggs Institute case report appraisal checklist for inclusion in systematic reviews (Munn et al., 2020). We found 809 case of PSD in 15 publications (Figure 2; Table 2). All studies suggested SG have obvious therapeutic effect on PSD patients. In addition, much evidence has confirmed the efficacy of SG combined with Western medicine in the treatment of PSD (Table 3). Zeng et al. suggested that PSD treatment with SG for 6 weeks had a higher overall effectivity rate than paroxetine (78.0 vs. 56.2%) and a lower incidence of side effects (7.3 vs. 24.4%) (Zeng et al., 2014). In addition, SG can be combined with a variety of classic Western antidepressant drugs to treat PSD and has achieved an ideal therapeutic effect. For example, SG can be combined with venlafaxine, paroxetine, and citalopram. Compared with PSD patients using Western drugs alone, SG showed better efficacy and provided patients with a safer treatment experience (Zhang and Xu, 2013; Zheng et al., 2014). Moreover, compared with agomelatine alone, SG combined with agomelatine significantly improved the metabolic levels of neurocytokines and monoamine transmitters in PSD patients, further proving the effectiveness of SG from a pathogenesis perspective (Fu and Wang, 2019).

FIGURE 2.

Prisma flowchart with details of the article screening process.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and findings in clinical studies reviewed.

| Authors, years | Study type | Country location | Study group | Age (years); sex | Therapeutic intervention | Treatment course | Main efficacy evaluation index | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. (2014) | RS | China | 30 P | 55.2 ± 9.3; 17 male, 13 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | TER, HAMD | Improve |

| Pang, (2019) | RS | China | 50 P | 68.1 ± 5.5; 32 male, 18 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 4 weeks | SDS | Improve |

| Zeng et al. (2014) | RS | China | 80 P | 62.3 ± 9.2; 44 male, 38 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | SDS, ADR | Improve |

| Li et al. (2015b) | RS | China | 157 P | 32–52, 75 male, 82 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Cheng, (2012) | RS | China | 50 P | 52.0 ± 8.0; 29 male, 21 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | TER, HAMD | Improve |

| Xiong and Li, (2015) | RS | China | 30 P | 46.3 ± 5.2; 18 male, 12 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | NIHSS, BI, HAMD | Improve |

| Li, 2019slu | RS | China | 41 P | 67.2 ± 5.8; 22 male, 19 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Zhao and Wu, (2013) | RS | China | 64 P | 42–77; 29 male, 35 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Chen, (2014) | RS | China | 58 P | 58.5 ± 5.7; 29 male, 28 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Lu and Gu, (2019) | RS | China | 41 P | 67.2 ± 5.8; 22 male, 19 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Liu et al., 2019 | RS | China | 59 P | 67.2 ± 5.8; 35 male, 19 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 4 weeks | SDS, HAMD, ADL, NFDS | Improve |

| Zheng et al. (2017) | RS | China | 40 P | 59.3 ± 4.0; 23 male, 17 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 12 weeks | BI, HAMD | Improve |

| Yao et al. (2020) | RS | China | 15 P | 64.1 ± 6.0; 8 male, 7 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 8 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Wang et al. (2016) | RS | China | 34 P | 66.5 ± 4.9; 18 male, 16 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 6 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

| Mao and Luo, (2016) | RS | China | 60 P | 62.5 ± 3.8; 32 male, 28 female | SG 720mg, Bid | 8 weeks | HAMD | Improve |

ADL, activity of daily living scale; ADR, adverse drug reactions; BI, Barthel Index; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; NFDS, neural function defect score; NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale; P, patients; TER, total effective rate; RS, retrospective study; SDS, Self-rating depression scale; SG, Shugan Jieyu capsule.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics and Findings in efficacy of SG combined with Western medicine in the treatment of PSD.

| Number of patients | Degree of depression | Therapeutic intervention | Treatment course | Main efficacy evaluation index | Key findings | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | Control group | |||||||

| P 41: C 41 | Mild-moderate | SG | Paroxetine | 6 weeks | SDS | SG could effectively improve depression symptoms in PSD patients with high security | Zeng et al. (2014) | |

| P 35: C 35 | Moderate-severe | SG + Venlafaxine | Venlafaxine | 6 weeks | HAMD | Venlafaxine combined with SC is effective and safe in the treatment of moderate to severe PSD | Zhang and Xu, 2013 | |

| P 32: C 32 | Mild-moderate | SG + Paroxetine | Paroxetine | 6 weeks | HAMD | SG combined with Paroxetine in treatment of PSD clinical efficacy with fewer adverse reactions | Zheng et al. (2014) | |

| P 47: C 47 | Mild-moderate | SG + Agomelatine | Agomelatine | 6 weeks | HAMD | SG combined with agomelatine can improve the levels of neurocytokines and monoamine transmitter metabolism in PSD patients | Fu and Wang, (2019) | |

| P 30: C 30 | Mild-moderate | SG + Citalopram | Citalopram | 6 weeks | HAMD, NIHSS | Citalopram combined with SG is effective and safe in the treatment of PSD | Xiong and Li, (2015) | |

| P 48: C 48 | Mild-moderate | SG + Venlafaxine | Venlafaxine | 6 weeks | HAMD, NIHSS | SG increases neurotransmitter transmission, alleviates negative emotions and promotes the recovery of neurological function, with high safety | Wang et al. (2021) | |

| P 30: C 21 | Mild-moderate | SG | − | 8 weeks | MoCA, HAMD | SG may improve the cognitive function of PSD patients through alteration of brain dynamics | Yao et al. (2020) | |

| P 40: C 40 | Mild-moderate | SG | − | 6–12 weeks | HAMD, Barthel | SG therapy for PSD is effective and also improve the ability of daily life | Zheng et al. (2017) | |

Degree of depression: mild-moderate: 17 ≤ HAMD17 ≤ 28; moderate-severe 24 ≤ HAMD17.

HAMD, HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health stroke scale; PSD, post-stroke depression; SDS, self-rating depression scale; P, patients; C, controls.

For PSD patients with motor symptoms, SG also showed advantages. SG increased neurotransmission, alleviated negative emotions, and promoted the recovery of neurological function, with high safety (Wang et al., 2021). Zheng et al. also concluded that SG therapy for PSD is effective and improved the abilities of daily living (Zheng et al., 2017). PSD may be accompanied by dynamic changes in brain function, thereby impairing the cognitive function of patients. The research results of Yao et al. suggested that SG may improve the cognitive function of PSD patients by changing brain dynamics, which lays a foundation for exploring the neurobiological mechanism of SG by improving the symptoms of PSD patients (Yao et al., 2020).

In summary, these clinical studies have shown that SG has obvious advantages in the treatment of PSD. In addition to improving the depressive symptoms of PSD patients, SG can also alleviate the physical dysfunction of PSD patients, increase their quality of life, and possibly improve their cognitive function. However, most of the current studies on the treatment of PSD by SG are limited to Chinese patients, and the number of patients included in the studies is small. Future large-scale randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of SG against PSD.

Discussion

Using modern pharmacological research methods to explore the molecular mechanism of TCM components or single molecules can facilitate an understanding of the systematic mechanism behind TCM prescriptions. Systems pharmacology studies the effective components, drug targets, and effects of TCM at the systemic level, revealing all the responses of different biological systems to the pharmacological effects of the drugs (Li and Zhang, 2013). Therefore, systems pharmacology is an important approach for gaining understanding of the systemic mechanisms of TCM prescriptions. In addition, with the development of TCM prescription research, increasing numbers of TCM monomers have been discovered. Through in vivo, in vitro, animal, and human pharmacology studies, it has been found that there are many effective components in TCM for treating diseases, and these active components may play a synergistic role through various mechanisms.

Although single TCM molecules have been shown to have powerful effects in the treatment of PSD, compound TCM prescriptions, rather than single forms, are used clinically. In clinical practice, TCM prescriptions are more effective and safer than single drugs, probably due to their synergistic and mutual detoxification. SG is a TCM prescription that can be explained by systems pharmacological studies of the interactions between TCM molecules that may be triggered by the synergistic effects of two or more herbs.

However, research into the pharmacological mechanism of TCM prescriptions is still in its infancy, and the ratio and molecular interaction of various drugs in the prescriptions have not been clearly elucidated. At present, studies on pharmacological mechanisms can only prove the effectiveness of the active ingredients in TCM, and the synergistic effects of various active ingredients need to be explored further and confirmed. The effective way to solve this problem is to establish a complete database (Xie et al., 2015), including the pharmacological action of various drug monomers, the synergistic action of various monomers, and their interaction with various diseases. Such a database will facilitate advancement of research from the molecular level to the system level, and thereby promote the TCM treatment of PSD.

In conclusion, the combination of system level and molecular level research not only represents a trend in TCM research, but also promotes our understanding of the mechanism of the TCM prescription system. With the development of neurobiology and systems pharmacology, research into SG will help to develop appropriate drugs or methods for the effective and safe treatment of PSD in future.

Author Contributions

This manuscript was primarily written by MZ and XB. Figures were produced by MZ. XB contributed to the editing and revision of the review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Araragi N., Mlinar B., Baccini G., Gutknecht L., Lesch K. P., Corradetti R. (2013). Conservation of 5-HT1A Receptor-Mediated Autoinhibition of Serotonin (5-HT) Neurons in Mice with Altered 5-HT Homeostasis. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 97. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayerbe L., Ayis S., Wolfe C. D., Rudd A. G. (2013). Natural History, Predictors and Outcomes of Depression after Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 14–21. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluchnejadmojarad T., Mansouri M., Ghalami J., Mokhtari Z., Roghani M. (2017). Sesamin Imparts Neuroprotection against Intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine Toxicity by Inhibition of Astroglial Activation, Apoptosis, and Oxidative Stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 88, 754–761. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal Y., Kuhad A. (2016). Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol 14, 610–618. 10.2174/1570159x14666160229114755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian X., Liu X., Liu J., Zhao Y., Li H., Cai E., et al. (2018). Study on Antidepressant Activity of Chiisanoside in Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol 57, 33–42. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaterra G. A., Mierau O., Hofmann J., Schwarzbach H., Aziz-Kalbhenn H., Kolb C., et al. (2020). In Vitro Effects of St. John's Wort Extract against Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress and in the Phagocytic and Migratory Activity of Mouse SIM-A9 Microglia. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 603575. 10.3389/fphar.2020.603575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J., Zhang X. L., Nicholson K. L., Balster R. L., Leander J. D., Stanton P. K., et al. (2013). GLYX-13, a NMDA Receptor Glycine-Site Functional Partial Agonist, Induces Antidepressant-like Effects without Ketamine-like Side Effects. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 729–742. 10.1038/npp.2012.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterweck V., Hegger M., Winterhoff H. (2004). Flavonoids of St. John's Wort Reduce HPA axis Function in the Rat. Planta Med. 70, 1008–1011. 10.1055/s-2004-832631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterweck V., Winterhoff H., Herkenham M. (2001). St John's Wort, Hypericin, and Imipramine: a Comparative Analysis of mRNA Levels in Brain Areas Involved in HPA axis Control Following Short-Term and Long-Term Administration in normal and Stressed Rats. Mol. Psychiatry 6, 547–564. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. D., Tao W. W., Su S. L., Guo S., Zhu Y., Guo J. M., et al. (2017). Antidepressant Activity of Flavonoid Ethanol Extract of Abelmoschus Manihot corolla with BDNF Up-Regulation in the hippocampus. Yao Xue Xue Bao 52, 222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Wang S. J. (2010). Hypericin, the Active Component of St. John's Wort, Inhibits Glutamate Release in the Rat Cerebrocortical Synaptosomes via a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-dependent Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 634, 53–61. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Dong Y., Liu F., Gao C., Ji C., Dang Y., et al. (2020). A Study of Antidepressant Effect and Mechanism on Intranasal Delivery of BDNF-Ha2tat/AAV to Rats with Post-Stroke Depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 637–649. 10.2147/NDT.S227598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Liu Z., Zhao J., Chen R., Meng F., Zhang M., et al. (2011). Antioxidant and Immunobiological Activity of Water-Soluble Polysaccharide Fractions Purified from Acanthopanax Senticosu. Food Chem. 127, 434–440. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. (2014). Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on 58 Cases of post-stroke Depression. Med. Theor. Pract. 15, 2005–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L. S., Tu W. J., Shen Y., Zhang L. J., Ji K. (2018). Combination of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Homocysteine Predicts the Post-Stroke Depression in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 2952–2958. 10.1007/s12035-017-0549-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S. Y., Zhao Y. D., Li J., Chen X. Y., Wang R. D., Zeng J. W. (2014). Plasma Levels of Glutamate during Stroke Is Associated with Development of post-stroke Depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 47, 126–135. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. Q. (2012). Shugan Jieyu Capsule Treatment of post-stroke Depression 50 Case. J. Mod. Integrated Chin. West. Med. 21, 304. [Google Scholar]

- Cirak C., Radusiene J., Janulis V., Ivanauskas L. (2010). Secondary Metabolites of Hypericum Confertum and Their Possible Chemotaxonomic Significance. Nat. Prod. Commun. 5, 897–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J., G K R. (2018). Post Stroke Depression: The Sequelae of Cerebral Stroke. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 90, 104–114. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R. S., Sanacora G., Krystal J. H. (2019). Altered Connectivity in Depression: GABA and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 102, 75–90. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezema C. I., Akusoba P. C., Nweke M. C., Uchewoke C. U., Agono J., Usoro G. (2019). Influence of Post-Stroke Depression on Functional Independence in Activities of Daily Living. Ethiop J. Health Sci. 29, 841–846. 10.4314/ejhs.v29i1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Wang Q., Yan Y. (2012). Influence of Xingnao Jieyu Capsule on Hippocampal and Frontal Lobe Neuronal Growth in a Rat Model of post-stroke Depression. Neural Regen. Res. 7, 187–190. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B. L., Wang Q. C., Li Z. Y. (2004). Influence of Jieyu Huoxue Decoction on Rehabilitation of Patients with Depression after Cerebral Infarction. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao 2, 182–184. 10.3736/jcim20040309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Wang J. (2019). Clinical Study on Shugan Jieyu Capsule Combined with Agomelatine in Treating Post-stroke Depression. World Latest Med. Inf. 19, 233–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa T., Kanada N., Shimada A., Ogata M., Suzuki I., Hayashi I., et al. (2005). Effect of Sesamin in Acanthopanax senticosus HARMS on Behavioral Dysfunction in Rotenone-Induced Parkinsonian Rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 28, 169–172. 10.1248/bpb.28.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Yang Y., Chen X., Yang M., Huang D., Yang R., et al. (2017). Hyperoside Protects against Chronic Mild Stress-Induced Learning and Memory Deficits. Biomed. Pharmacother. 91, 831–840. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum B. F., Kutz R., Zlotnik A., Boyko M. (2020). Blood Glutamate Scavenging as a Novel Glutamate-Based Therapeutic Approach for post-stroke Depression. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 10, 2045125320903951. 10.1177/2045125320903951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Bian L., Liu X., Zhang F., Zhang Y., Yu N. (2014). Effects of Acanthopanax Senticosus Polysaccharide Supplementation on Growth Performance, Immunity, Blood Parameters and Expression of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines Genes in Challenged Weaned Piglets. Asian-australas J. Anim. Sci. 27, 1035–1043. 10.5713/ajas.2013.13659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Liu L., Yu N., Chen J., Liu B., Yang D., et al. (2016). Polysaccharides from Acanthopanax senticosus Enhances Intestinal Integrity Through Inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathways in Lipopolysaccharide-Challenged Mice. Anim Sci J. 87, 1011–1018. 10.1111/asj.12528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz T., Guillén H. (2018). Monoamine Oxidase-A Inhibition and Associated Antioxidant Activity in Plant Extracts with Potential Antidepressant Actions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 4810394. 10.1155/2018/4810394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K. K., Ding H., Yu H. W., Dong T. J., Pan Y., Kong L. D. (2018). Huanglian-Wendan Decoction Inhibits NF-Κb/nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation in Liver and Brain of Rats Exposed to Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 3093516. 10.1155/2018/3093516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Ling Z., Zhang Y., Mao H., Ma Z., Yin Y., et al. (2015). Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 48, 186–194. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Wu F., Li X., Li H., Du C., Jiang Q., et al. (2013). Anti-depressant Effects of Aqueous Extract from Acanthopanax Senticosus in Mice. Phytother Res. 27, 1829–1833. 10.1002/ptr.4938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Jiang M., Gong D., Chen Y., Fan Y. (2018). Efficacy and Safety of Xiaoyao Formula as an Adjuvant Treatment for Post-Stroke Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Explore (NY) 14, 224–229. 10.1016/j.explore.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. M., Park S. J., Lee Y. W., Lee H. E., Hong S. I., Lew J. H., et al. (2013). The Effects of a Standardized Acanthopanax Koreanum Extract on Stress-Induced Behavioral Alterations in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol 148, 826–834. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata K., Kawai Y., Terao J. (2010). Suppressive Effect of Quercetin on Acute Stress-Induced Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis Response in Wistar Rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 21, 374–380. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J., Gomez R., Williams G., Lembke A., Lazzeroni L., Murphy G. M., Jr., et al. (2017). HPA axis in Major Depression: Cortisol, Clinical Symptomatology and Genetic Variation Predict Cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 527–536. 10.1038/mp.2016.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. M., Tang Q. S., Zhao R. Z., Li X. L., Wang G., Yang X. K. (2015a). Effect of Yinao Jieyu Recipe on Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor of the Limbic System in Post-Stroke Model Rats. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 35, 988–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhao Y. D., Zeng J. W., Chen X. Y., Wang R. D., Cheng S. Y. (2014a). Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in post-stroke Depression. J. Affect Disord. 168, 373–379. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Fu Q., Li Y., Li S., Xue J., Ma S. (2014b). Emodin Opposes Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Induced Depressive-like Behavior in Mice by Upregulating the Levels of Hippocampal Glucocorticoid Receptor and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Fitoterapia 98, 1–10. 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Q., Luo J., Liu X. Q., Kwon D. Y., Kang O. H. (2021). Eleutheroside K Isolated from Acanthopanax Henryi (Oliv.) Harms Suppresses Methicillin Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus . Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 72, 669–676. 10.1111/lam.13389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Zhang B. (2013). Traditional Chinese Medicine Network Pharmacology: Theory, Methodology and Application. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 11, 110–120. 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60037-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Wang D., Zhao B., Yan Y. (2018). Xingnao Jieyu Decoction Ameliorates Poststroke Depression through the BDNF/ERK/CREB Pathway in Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2018, 5403045. 10.1155/2018/5403045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. R. (2019). Evaluation of Early Intervention Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on Patients with post-stroke Depression. World Latest Med. Inf. (Electronic Version) 19, 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. X., Shen Y., He W. T., Wang W., Gao H. M. (2015b). Clinical Observation of Shugan Jieyu Capsule in the Treatment of Depression after First Stroke. Ningxia Med. J. 37, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. Q., Zhang L. N., Yuan C. (2019). Clinical Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on the Level of Norepinephrine and 5-hydroxytryptamine in Patients with post-stroke Depression. World Chin. Med. 14, 1784–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang Z., Wang C., Si H., Yu H., Li L., et al. (2021). Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis and Sedative-Hypnotic Activity of Two Acanthopanax Species Leaves. Food Funct. 12, 2292–2311. 10.1039/d0fo02814b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loubinoux I., Kronenberg G., Endres M., Schumann-Bard P., Freret T., Filipkowski R. K., et al. (2012). Post-stroke Depression: Mechanisms, Translation and Therapy. J. Cell Mol Med 16, 1961–1969. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01555.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Gu Y. (2019). Effect and Safety of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on Improving Emotional State of Patients with post-stroke Depression. Smart Healthc. 5, 179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Zhang L., Ning N., Jiang H., Yu S. Y. (2013). Neotrofin Reverses the Effects of Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress on Behavior via Regulating BDNF, PSD-95 and Synaptophysin Expression in Rat. Behav. Brain Res. 253, 48–53. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Deng S., Yi J., Zhou S., She Y., Liu B. (2017). Buyang Huanwu Decoction Ameliorates Poststroke Depression via Promoting Neurotrophic Pathway Mediated Neuroprotection and Neurogenesis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2017, 4072658. 10.1155/2017/4072658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado D. G., Bettio L. E., Cunha M. P., Santos A. R., Pizzolatti M. G., Brighente I. M., et al. (2008). Antidepressant-Like Effect of Rutin Isolated from the Ethanolic Extract from Schinus molle L. in Mice: Evidence for the Involvement of the Serotonergic and Noradrenergic Systems. Eur J Pharmacol. 587, 163–168. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao S. L., Luo S. (2016). Clinical Study of Shugan Jieyu Capsule in the Treatment of post-stroke Depression. Clin. Medication J. 14, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Menke A. (2019). Is the HPA Axis as Target for Depression Outdated, or Is There a New Hope? Front. Psychiatry 10, 101. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S., Fujita Y., Oikawa H., Takekoshi H., Soya H., Ogata M., et al. (2020). Combination of Syringaresinol-Di-O-β-D-Glucoside and Chlorogenic Acid Shows Behavioral Pharmacological Anxiolytic Activity and Activation of Hippocampal BDNF-TrkB Signaling. Sci. Rep. 10, 18177. 10.1038/s41598-020-74866-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Barker T. H., Moola S., Tufanaru C., Stern C., Mcarthur A., et al. (2020). Methodological Quality of Case Series Studies: an Introduction to the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 18, 2127–2133. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough J. W., Iosifescu D. V., Chang L. C., Al Jurdi R. K., Green C. E., Perez A. M., et al. (2013). Antidepressant Efficacy of Ketamine in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression: a Two-Site Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 1134–1142. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzelska-Górka J., Szewczyk K., Gawrońska-Grzywacz M., Kędzierska E., Głowacka E., Herbet M., et al. (2019). Monoaminergic System Is Implicated in the Antidepressant-like Effect of Hyperoside and Protocatechuic Acid Isolated from Impatiens Glandulifera Royle in Mice. Neurochem. Int. 128, 206–214. 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C., Gold S. M., Penninx B. W., Pariante C. M., Etkin A., Fava M., et al. (2016). Major Depressive Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16065. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Y. (2019). Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on Mild to Moderate Depression after Ischemic Stroke. Contemp. Med. Symp. 17, 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak L., Agrawal Y., Dhir A. (2013). Natural Polyphenols in the Management of Major Depression. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 22, 863–880. 10.1517/13543784.2013.794783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Zhang X., Kang D. Y., Liu X. T., Hong Q. (2014). Effectiveness and Safety of Wuling Capsule for post Stroke Depression: a Systematic Review. Complement. Ther. Med. 22, 549–566. 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y., Zhang H., Liang S., Chen J., Yan X., Duan Z., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the Antidepressant Effect of the Functional Beverage Containing Active Peptides, Menthol and Eleutheroside and Investigation of its Mechanism of Action in Mice. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 58, 295–302. 10.17113/ftb.58.03.20.6568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. G., Jorge R. E. (2016). Post-stroke Depression: A Review. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 221–231. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões L. R., Netto S., Generoso J. S., Ceretta R. A., Valim R. F., Dominguini D., et al. (2019). Imipramine Treatment Reverses Depressive- and Anxiety-like Behaviors, Normalize Adrenocorticotropic Hormone, and Reduces Interleukin-1β in the Brain of Rats Subjected to Experimental Periapical Lesion. Pharmacol. Rep. 71, 24–31. 10.1016/j.pharep.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza D. O., Dos Santos Sales V., De Souza Rodrigues C. K., De Oliveira L. R., Santiago Lemos I. C., de Araújo Delmondes G., et al. (2018). Phytochemical Analysis and Central Effects of Annona Muricata Linnaeus: Possible Involvement of the Gabaergic and Monoaminergic Systems. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 17, 1306–1317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J., Kong L., Fang M., Zhu Q., Zhang S., Zhang S., et al. (2021). The Efficacy of Tuina with Herbal Ointment for Patients with post-stroke Depression: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 22, 504. 10.1186/s13063-021-05469-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Ray M., Weickert C. S., Wyatt E., Webster M. J. (2011). Decreased BDNF, trkB-Tk+ and GAD67 mRNA Expression in the hippocampus of Individuals with Schizophrenia and Mood Disorders. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 36, 195–203. 10.1503/jpn.100048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verjee S., Kelber O., Kolb C., Abdel-Aziz H., Butterweck V. (2019). Permeation Characteristics of Hypericin across Caco-2 Monolayers in the Presence of Single Flavonoids, Defined Flavonoid Mixtures or Hypericum Extract Matrix. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 71, 58–69. 10.1111/jphp.12717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa R. F., Ferrari F., Moretti A. (2018). Post-stroke Depression: Mechanisms and Pharmacological Treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 184, 131–144. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan R., Song R., Fan Y., Li L., Zhang J., Zhang B., et al. (2021). Efficacy and Safety of Chaihu Jia Longgu Muli Decoction in the Treatment of Poststroke Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021, 7604537. 10.1155/2021/7604537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Deng Y., He Q., Li Q., Peng D., Duan J. (2010). Neuroprotective Effects of Serum with Tongqiao Huoxue Decoction (TQHXD) against Glutamate-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 35, 1307–1310. 10.4268/cjcmm20101019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. S., Wang Y. G., Chen H. Y., Wu Z. P., Xie H. G. (2013). Expression of Genes Encoding Cytokines and Corticotropin Releasing Factor Are Altered by Citalopram in the Hypothalamus of post-stroke Depression Rats. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 34, 773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Dong H., Ji S., Jin X. (2021). Clinical Effect of Venlafaxine Combined with Shugan Jieyu Capsule on Depression after Cerebral Infarction. J. Clin. Psychosomatic Dis. 27, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. X., Xu H. X., Liu X. X., Zhang F. J., Guo F., Shang H. X. (2016). Clinical Efficacy of the Shugan Jieyu Capsules on Minor Depression Following Stroke in the Elderly. Clin. Study Chin. Med. 8, 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L., Han Q. Q., Gong W. Q., Pan D. H., Wang L. Z., Hu W., et al. (2018). Microglial Activation Mediates Chronic Mild Stress-Induced Depressive- and Anxiety-like Behavior in Adult Rats. J. Neuroinflammation 15, 21. 10.1186/s12974-018-1054-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H., Weymann K. B., Wood L., Wang Q. M. (2018). Inflammatory Signaling in Post-Stroke Fatigue and Depression. Eur. Neurol. 80, 138–148. 10.1159/000494988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Zhang G., Zhao C., Yang Y., Miao Z., Xu X. (2020). Interleukin-18 from Neurons and Microglia Mediates Depressive Behaviors in Mice with post-stroke Depression. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 411–420. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Li H., Zhao L., Li X., You J., Jiang Q., et al. (2013). Protective Effects of Aqueous Extract from Acanthopanax Senticosus against Corticosterone-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. J. Ethnopharmacol 148, 861–868. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. C., Yang B., Luo C. F., Yang C., Cao G. X., Tan X. L. (2014). Analysis of 30 Cases of post-stroke Depression Treated by Shugan Jieyu Capsule Combined with Comprehensive Psychological Intervention. Chongqing Med. J. 43, 419–420. [Google Scholar]

- Xie T., Song S., Li S., Ouyang L., Xia L., Huang J. (2015). Review of Natural Product Databases. Cell Prolif 48, 398–404. 10.1111/cpr.12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong A. L., Li Z. P. (2015). Shugan Jieyu Capsule Combined with Psychological Intervention to Treat post-stroke Depression. Joumal Changchua Univ. Chin. Med. 31, 751–752. [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Xu X., He Z., Wang S., Zhao L., Qiu J., et al. (2020). Antidepressant-Like Effects and Cognitive Enhancement of Coadministration of Chaihu Shugan San and Fluoxetine: Dependent on the BDNF-ERK-CREB Signaling Pathway in the Hippocampus and Frontal Cortex. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2794263. 10.1155/2020/2794263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Fan W., Liu L., Yang R., Yang W. (2013). The Effects of Xingnao Jieyu Capsules on post-stroke Depression Are Similar to Those of Fluoxetine. Neural Regen. Res. 8, 1765–1772. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.19.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G., Li J., Wang J., Liu S., Li X., Cao X., et al. (2020). Improved Resting-State Functional Dynamics in Post-stroke Depressive Patients after Shugan Jieyu Capsule Treatment. Front. Neurosci. 14, 297. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino S., Hara A., Sakakibara H., Kawabata K., Tokumura A., Ishisaka A., et al. (2011). Effect of Quercetin and Glucuronide Metabolites on the Monoamine Oxidase-A Reaction in Mouse Brain Mitochondria. Nutrition 27, 847–852. 10.1016/j.nut.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Załuski D., Mendyk E., Smolarz H. D. (2016). Identification of MMP-1 and MMP-9 Inhibitors from the Roots of Eleutherococcus Divaricatus, and the PAMPA Test. Nat. Prod. Res. 30, 595–599. 10.1080/14786419.2015.1027891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X. L., Yang B., Li Y. M., Zhuang W. Y., Cuo S. (2014). Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on post-stroke Depression. China Mod. Med. 21, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E., Liao P. (2020). Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor and post-stroke Depression. J. Neurosci. Res. 98, 537–548. 10.1002/jnr.24510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Yang C., Chu J., Ning L. N., Zeng P., Wang X. M., et al. (2021). Emodin Prevented Depression in Chronic Unpredicted Mild Stress-Exposed Rats by Targeting miR-139-5p/5-Lipoxygenase. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 696619. 10.3389/fcell.2021.696619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xu B. (2013). Effect of Venlafaxine Sustained-Release Tablet Combined with Shugan Jieyu Capsule in the Treatment of post-stroke Depression. Chin. J. Prim. Med. Pharm. 20, 3074–3076. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L. A., Wu Q. Y. (2013). Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on 64 Cases of Depression after Ischemic Stroke. Health Vis. 21, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng A., Zhao F., Zheng S. (2014). Shugan Jieyu Capsule Combined with Paroxetine to Observe the Curative Effect in the Treatment of Post-stroke Depression. Guide China Med. 12, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X. D., Li J., Yi F. (2017). Effect of Shugan Jieyu Capsule on Patients with post-stroke Depression and Daily Living Activities. J. Stroke Neurol. Dis. 34, 446–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zunszain P. A., Anacker C., Cattaneo A., Carvalho L. A., Pariante C. M. (2011). Glucocorticoids, Cytokines and Brain Abnormalities in Depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 35, 722–729. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]