Abstract

Since 2005 campylobacteriosis has been the most commonly reported gastrointestinal infection in humans in the European Union with more than 200,000 cases annually. Also Campylobacter is one of the most frequent cause of food-borne outbreaks with 319 outbreaks reported to EFSA, involving 1,254 cases of disease and 125 hospitalizations in EU in 2019. Importantly poultry meat is one of the most common source for the sporadic Campylobacter infections and for strong-evidence campylobacteriosis food-borne outbreaks in EU.

In present study, 429 fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin were collected from Estonian retail level and analyzed on a monthly basis between September 2018 and October 2019. Campylobacter spp. were isolated in 141 (32.9%) of 429 broiler chicken meat samples. Altogether 3 (1.8%), 49 (36.8%), and 89 (66.9%) of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin broiler chicken meat samples were positive for Campylobacter spp. Among Campylobacter-positive samples, 62 (14.5%) contained Campylobacter spp. below 100 CFU/g and in 28 (6.5%) samples the count of Campylobacter spp. exceeded 1,000 CFU/g. A high prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in fresh broiler chicken meat of Lithuanian and Latvian origin in Estonian retail was observed. Additionally, 22 different multilocus sequence types were identified among 55 genotyped isolates of broiler chicken meat and human origin, of which 45 were Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and 10 were Campylobacter coli (C. coli). The most prevalent multilocus sequence types among C. jejuni was ST2229 and among C. coli ST832, ST872. C. jejuni genotypes found in both broiler chicken meat and human origin samples were ST122, ST464, ST7355, and ST9882, which indicates that imported fresh broiler chicken meat is likely the cause of human campylobacteriosis in Estonia.

Key words: Campylobacter spp., prevalence, counts, MLST sequence types, fresh broiler chicken meat

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter is the most common cause of human bacterial gastroenteritis in the world and campylobacteriosis is commonly reported zoonosis in humans in European Union (EU) since 2005 (World Health Organization, 2013; European Food Safety Authority EFSA and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ECDC 2021). According to European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), there were 220,682 confirmed human cases in EU in 2019, with notification rate of 59.7 per 100,000 population on average. In Estonia, 348 confirmed cases of human campylobacteriosis were registered in 2019, with a notification rate of 26.4 per 100,000 inhabitant (Estonian Health, 2021). The human campylobacteriosis notification rate in Estonia is 2.3 times lower than the average in European Union. However, the true numbers of human campylobacteriosis may be higher than officially reported, because infectious diseases are often underestimated, under-ascertained, or underreported (Gibbons et al., 2014). Campylobacteriosis is a notifiable infectious disease and an important problem for the public health and food industry (Tumbarski, 2019). The two main Campylobacter species causing a disease in humans are C. jejuni and C. coli causing approximately 80% and 10% of campylobacteriosis cases (EFSA, 2018). Different studies have demonstrated that C. jejuni is the predominant species in poultry (Meremäe et al, 2010; Korsak et al., 2015; Rossler et al., 2019; Yushina et al., 2020). According to Mäesaar et al. (2020) poultry is the main source of C. jejuni human infections in the Baltic States. The source of human campylobacteriosis is primarily considered to be poultry, especially broiler chicken meat, but also other food sources such as raw milk, pork and untreated water (Mäesaar et al., 2020; European Food Safety Authority EFSA and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ECDC 2021). Campylobacter infection occurs often due to consumption of undercooked chicken meat, or other food cross-contaminated during preparation process (Rosner et al., 2017). Entire processing chain of broiler chicken meat has a major importance of transmitting Campylobacter from farm to fork (Skarp et al., 2016).

In many countries the seasonal peak in the number of human campylobacteriosis cases and in Campylobacter prevalence in poultry is in summer months (Bunevičienė et al., 2010; Meremäe et al., 2010; Kovalenko et al., 2013; Mäesaar et al., 2014; Jaakola et al., 2015; Nastasijevic et al., 2020). However according to EFSA (2018), there is also a small but distinct winter peak that has been apparent in the human campylobacteriosis cases in the past few years.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence, counts and genetic relatedness of Campylobacter spp. isolated from broiler chicken meat at retail level of Estonia and from Estonian human patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Collection

Altogether 429 fresh broiler chicken meat samples were collected on a monthly basis between September 2018 and October 2019 at Estonian retail level. The collection included 163, 133, and 133 fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin. Company packaged fresh broiler chicken meat products, mostly legs and half-legs, were obtained from the biggest food retail outlets representing the biggest broiler chicken meat sales turnover in Estonia. The samples were transported to the laboratory in a portable cooler kept at +2° to +6°C. All the analyses were carried out in the laboratory of the Chair of Food Hygiene and Veterinary Public Health of the Estonian University of Life Sciences.

Additionally, in collaboration with the Estonian hospitals, 18 C. jejuni and 2 C. coli isolates related with human Campylobacter infections in Estonia were obtained during the study period in 2018–2019 for sequence typing.

Campylobacter spp. Isolation and Identification

Campylobacter spp. detection and enumeration from broiler chicken meat samples was performed according to the ISO 10272–1:2017 and ISO 10272-2:2017. For Campylobacter spp. detection, 10 g of skin aseptically taken from broiler chicken meat samples was transferred into 90 mL Preston enrichment broth and incubated in a microaerobic conditions at 41.5 ± 0.5°C for 24 h. Then, 10 µL loopful of Preston enrichment material was inoculated onto mCCD agar medium (Oxoid; Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK). For Campylobacter spp. enumeration, 10 g of skin aseptically taken from broiler chicken meat samples was placed into a sterile plastic bag and 90 mL buffered Peptone water was added. The samples were stomached for 60 s. Then, 0.1 mL of 10-fold dilution material was taken and carried onto the surface of 2 mCCD (Oxoid) agar plates. All plates were incubated in microaerobic conditions at 41.5°C ± 0.5°C for 48 h. Typical Campylobacter colonies on mCCDA plates were streaked on Columbia blood agar (Oxoid Ltd; ), which were incubated for 24 h at 41.5°C ± 0.5°C. Additional confirmation tests included Gram staining, motility analysis, oxidase, and catalase tests. Isolates confirmed as Campylobacter spp. were stored at –80°C in glycerol broth (20% [vol/vol] glycerol in 1% [wt/vol] proteose peptone) for further studies.

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Genotyping

DNA was extracted using GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The sequencing libraries were prepared with Illumina Nextera XT library preparation kit, according to manufacturer's protocol (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Libraries were pooled in equimolar concentrations and the sequencing was carried out on an Illumina NextSeq500 System using high output kit in paired end 2 × 151 bp mode. The library preparation and sequencing were conducted as follows in the Institute of Genomics Core Facility, University of Tartu, Estonia.

Quality of the raw reads was checked using FastQC v0.11.9 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.39 with default parameters for paired-end reads (Bolger et al., 2014). The reads were assembled using SPAdes v3.14.1 with single-cell mode and k-mer sizes 21, 33, 55, 77 (Bankevich et al., 2012). All assembled Campylobacter spp. genomes (n = 55) obtained from broiler chicken meat (n = 35) and human clinical cases (n = 20) were deposited and STs and CCs were assigned using the Campylobacter jejuni/coli multilocus sequence typing (MLST) database (pubMLST) (Supplementary Table 1; Jolley and Maiden, 2010).

Full minimum spanning tree (MST) of MLST allelic differences of 55 C. jejuni and C. coli isolates was constructed using goeBURST algorithm (Francisco et al., 2009) as implemented in PHYLOViZ v2.0 (Nascimento et al., 2017).

Statistical Analysis

Binomial Probability Confidence Interval (CI) at 95% confidence level in the prevalence and counts of the Campylobacter in the poultry meat products of different origin was calculated using the Clopper-Pearson (exact) method using R (R Core Team, 2021). Chi-square test was used to test for statistically significant associations between prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in fresh broiler chicken meat and sample origin (https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/chisquare2/default2.aspx). Results were considered statistically significant for P values of ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prevalence and Counts of Campylobacter spp

Campylobacter spp. was isolated in 141 (32.9%) of 429 broiler chicken meat samples in 2018-2019 (Table 1). In total, 3 (1.8%, CI95 0–5.3%) of Estonian origin, 49 (36.8%, CI95 28.6–45.6%) of Latvian origin and 89 (66.9%, CI95 58.2%–74.8%) of Lithuanian origin fresh broiler chicken meat samples were positive for Campylobacter spp. The associations between prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in fresh broiler chicken meat and country of origin was statistically significant (P < 0.00001). Study conducted by Mäesaar et al. (2014) in 2012, found that the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in Estonian origin fresh broiler chicken meat products was significantly lower (P < 0.001) than in Latvian and Lithuanian fresh broiler chicken meat products. Bunevičienė et al. (2010) determined a high Campylobacter prevalence (46.5% of positive samples) in the Lithuanian fresh broiler chicken meat in 2009. Additionally, high proportion of Campylobacter contamination of broiler chicken meat at slaughterhouse and retail level was reported in Latvia by Kovalenko et al. (2013). Our studies have shown that the contamination of fresh chicken broiler meat of Estonian origin with Campylobacter spp. has decreased year by year. Contrary, fresh broiler chicken meat of Latvian and Lithuanian origin is often contaminated with Campylobacter spp. at the Estonian retail level (Table 2). In European countries the proportion of Campylobacter-positive poultry meat at retail level has been different, 73.3% in the UK (Jorgensen et al., 2015) and much lower in Finland and Denmark, respectively 11 and 12% (Skarp et al., 2016). High proportion of Campylobacter contaminated poultry meat at retail has been also reported in Austria (71), France (76), Spain (70), Slovenia (54), Poland (50), and Italy (34.1%) (Skarp et al., 2016; Stella et al., 2017). According to the EU zoonoses report the average occurrence of Campylobacter in the fresh broiler meat in EU was 38.6 and 29.6%, respectively in year 2018 and 2019 (European Food Safety Authority EFSA and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ECDC 2021). This indicates that compared to many other European countries the prevalence of Campylobacter in Estonia is very low. Changes over time in the prevalence and counts of Campylobacter spp. in fresh chicken meat samples of Estonian retail is shown in the Table 2. A comparison of our previous studies reveals the decrease of Campylobacter spp. prevalence in fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian origin from 15.8 to 1.8%. Since 2012, the prevalence of Latvian and Lithuanian Campylobacter spp. in fresh broiler chicken meat has increased, from 25.8 to 36.8% and from 10.6 to 66.9%, respectively. One possible explanation to the decreasing trend in Campylobacter prevalence of fresh broiler chicken meat of Estonian origin is that strict biosecurity and self-control measures at farm, slaughterhouse and meat industry level are applied, also risk assessment based control measures are implemented at all stages of production. It is known that the spread of Campylobacter at retail level could be related to the low effectiveness of biosecurity measures applied on farm and slaughterhouse level. Campylobacter is widespread in nature and there are many sources of infection through which Campylobacter is brought to the farm if biosecurity measures are not effective enough. Different stages in the poultry production for example, primary production at rearing farms, transport, slaughtering process, processing of chicken meat products, retailing, handling, and consumption of chicken meat, play an important role in the transmission of Campylobacter from farm to fork (Skarp et al., 2016). The same authors point out that the Campylobacter contamination and colonization at farm level reflect the Campylobacter contamination of carcasses and poultry meat. Several authors have emphasized the critical importance of defeathering and evisceration in poultry processing (Saleha et al., 1998; Sasaki et al., 2013; Gruntar et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin collected at the Estonian retail level in 2018–2019.

| Country of origin | No. of samples | No. of positive samples (%) |

CI 95% ofpositive %2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detectionmethod | Enumerationmethod1 | |||

| Estonia | 163 | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0–5.3 |

| Latvia | 133 | 49 (36.8) | 11 (8.3) | 28.6–45.6 |

| Lithuania | 133 | 89 (66.9) | 70 (52.3) | 58.2–74.8 |

| Total | 429 | 141 (32.9) | 81 (18.9) | 28.4–37.5 |

Samples with both positive detection and positive enumeration result, the threshold of 100 CFU/g.

Confidence interval is given for detection method results.

Table 2.

Campylobacter prevalence and counts in retail broiler chicken meat from different studies performed in Estonia in period 2000–2019.

| Period | Method | Country of origin |

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania | |||

| 2000–2002 | Detection | 44/279 (15.8) | NS | NS | Roasto et al., 2005 |

| 2002–2007 | Detection | 163/1,320 (12.3) | NS | NS | Meremäe et al., 2010 |

| 2012 | Detection | 22/149 (14.8) | 8/31 (25.8) | 19/180 (10.6) | Mäesaar et al., 2014 |

| Enumeration | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.2 | ||

| 2018–2019 | Detection | 3/163 (1.8) | 49/133 (36.8) | 89/133 (66.9) | Present study |

| Enumeration | 2.3* | 2.5 | 2.8 | ||

Detection: No. of positive broiler chicken meat samples/No. of samples (positive %).

Enumeration: samples with both positive detection and positive enumeration result, Mean log10CFU/g.

Only one sample contained 2.3 log10CFU/g. NS, no samples.

A C. jejuni survival study in poultry processing plant environment revealed that some C. jejuni genotypes might survive the cleaning and disinfection procedures (García-Sánchez et al., 2017).

Present study was not aimed to seek for possible reasons for the higher prevalence of Campylobacter spp. among Latvian and Lithuanian origin fresh poultry meat at Estonian retail compare to Estonian products. Differently to Lithuania and Latvia, the only broiler chicken slaughterhouse and all broiler chicken farms in Estonia are belonging to one international meat company which has integrated food safety management systems at all production stages from feed production to final meat products.

According to Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs no food safety criteria has been established for Campylobacter spp. However, a very important change took place in 2017, when a process hygiene criterion was introduced for Campylobacter spp. on broiler carcasses. According to the regulation the limit of 1,000 CFU/g of Campylobacter spp. applies with the priority to the whole poultry carcases with the neck skin as sampling material. The distribution of Campylobacter counts of 141 broiler chicken meat samples is shown in Table 3. Among Campylobacter-positive samples, 62 (14.5%) contained Campylobacter spp. below 100 CFU/g. More than 1,000 CFU/g were determined from one (0.8%) Latvian and from 27 (20.3%) Lithuanian origin fresh broiler chicken meat samples. The highest count of Campylobacter (1,500 CFU/g) in Latvian origin samples was detected in February 2019. Among Campylobacter-positive samples of Lithuanian origin, the high counts of Campylobacter, ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 CFU/g, occurred throughout the year from October 2018 to August 2019. Several authors have reported the high prevalence of Campylobacter spp. at retail and the presence of heavily contaminated (>104 CFU/g) broiler meat and meat preparations (Humphrey et al., 2007; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2009). Campylobacter infections are likely to occur when eating undercooked broiler meat or cross-contaminated food (de Boer and Hahné, 1990).

Table 3.

Campylobacter enumeration data from fresh broiler chicken meat collected at Estonian retail level in 2018–2019.

| Origin |

Campylobacter counts (CFU/g) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0* | <100⁎⁎ | 100–499 | 500–1,000 | >1,000 | |

| Estonia | 160 (98.2) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latvia | 84 (63.2) | 39 (29.3) | 6 (4.5) | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Lithuania | 44 (33.1) | 21 (15.8) | 27 (20.3) | 14 (10.5) | 27 (20.3) |

| Total | 288 (67.1) | 62 (14.5) | 34 (25.6) | 17 (4.0) | 28 (6.5) |

Number of samples (percentage).

Negative detection and negative enumeration.

Negative enumeration and positive detection, the threshold.

Present study showed that Campylobacter counts in Estonian origin fresh broiler chicken meat were significantly (P < 0.00001) lower than in fresh broiler chicken meat products from Latvian and Lithuanian origin. It indicates that imported broiler chicken meat products may pose higher risk for human Campylobacter infections than Estonian broiler chicken meat. Also our previous study in 2012 found that Campylobacter counts in fresh broiler chicken meat was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in samples of Estonian origin compared to these originating from Latvia and Lithuania, which could pose the higher human campylobacteriosis risk (Mäesaar et al., 2014). High prevalence together with high counts of Campylobacter spp. in fresh chicken meat sold at retail level carries the campylobacteriosis risk, because it gives higher probability for Campylobacter cross-contamination at home kitchen level (Meremäe et al., 2010; Roasto et al., 2010). According to Keener et al. (2004) as few as 500 Campylobacter cells can cause an infection in human.

Campylobacter studies performed in Estonia show the decrease of Campylobacter spp. counts in fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin. In present study only one Estonian origin fresh chicken meat sample contained Campylobacter spp. 2.3 log10CFU/g. Other 2 chicken meat samples of Estonian origin that were Campylobacter-positive had Campylobacter counts below the quantification limit (100 CFU/g), and were not included in the calculation of the concentration averages.

Many studies have reported a seasonal peak in the number of human campylobacteriosis cases and higher Campylobacter prevalence in poultry during the summer months (Bunevičienė et al., 2010; Meremäe et al., 2010; Kovalenko et al., 2013; Mäesaar et al., 2014; Jaakola et al., 2015; Nastasijevic et al., 2020). According to Djennad et al. (2019), it was found that 33.3% of expected human campylobacteriosis cases are temperature dependent in England and Wales. Kovanen et al. (2014) found that the seasonal peak for Campylobacter human infections in summer months is related to different summer activities such as barbecuing, drinking well water, swimming in natural waters, and being more contact with animals and soil. Also, differences in seasonality of Campylobacter colonization in broilers can be affected by the farm management, the presence of different vectors and the survival mechanisms of Campylobacter spp. in the environment and in the host (Newell and Fearnley, 2003).

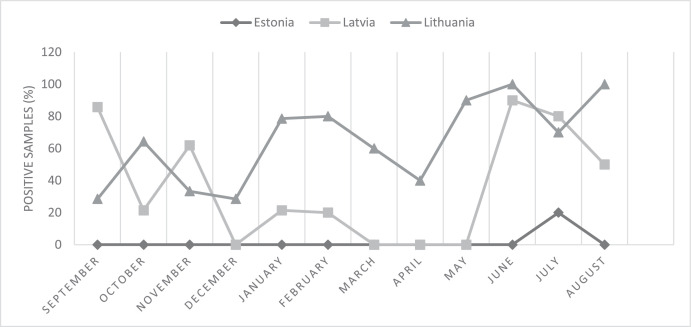

An earlier Estonian study by Mäesaar et al. (2014) found seasonal variation in the proportions of Campylobacter-positive fresh broiler chicken meat samples with a seasonal peak in the warm summer months. In present study the only positive samples (n = 3) among Estonian products were found in July. However, a distinct seasonal difference in Campylobacter contamination of broiler chicken meat samples at Estonian retail level was not found in present study (Figure 1). The proportion of Campylobacter spp. positive fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Lithuanian origin was consistently high during the whole study period. Similarly EFSA (2018) has reported a small but distinct winter peak for human campylobacteriosis in the past few years indicating the presence of Campylobacter contamination of food also in the cold months.

Figure 1.

The proportion of Campylobacter spp. positive fresh broiler chicken meat samples of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian origin in September 2018 to August 2019.

Sequencing Analyses

Altogether 55 Campylobacter isolates were sequenced and genotyped using for MLST to determine the genetic similarities of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian broiler chicken meat origin Campylobacter spp. with isolates from Estonian human patients.

The STs distribution among Campylobacter spp. isolated from fresh broiler chicken meat and from humans is shown in Table 4. Among 55 Campylobacter spp. isolates, 22 sequence types were determined. Nine sequence types were only found in human, 4 ST-s were found both for human and broiler chicken meat isolates, and the remaining ten ST-s were related only with broiler chicken meat.

Table 4.

Distribution of sequence types among the Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from Baltic broiler chicken meat and Estonian human patients.

| Source⁎⁎ | Sequence type, ST | Total No. of isolates | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | 10,997(1) | 1 | |||||||||||||

| LV | 356(1) | 832*(2) | 2,229(7) | 10 | |||||||||||

| LT | 19(4) | 354(3) | 614(2) | 832*(2) | 872*(4) | 6,461(1) | 122(2) | 464(2) | 7,355(1) | 9,882(3) | 24 | ||||

| H | 22(2) | 50(2) | 353(1) | 429(1) | 572(3) | 824(1) | 122(2) | 464(2) | 7,355(2) | 9,882(1) | 1,595*(1) | 1,624*(1) | 11,001(1) | 20 | |

Bold is indicating Campylobacter spp. sequence types of broiler chicken meat origin also found from Estonian human patients. (No)Number of C. jejuni or C. coli* strains.

C. coli MLST genotypes.

Source of isolates: EST; Estonia; LV, Latvia; LT, Lithuania; H, human.

The most commonly isolated sequence types for C. jejuni (n = 45) were ST2229 (n = 7; 16%), ST19 (n = 4; 9%), ST122 (n = 4; 9%), ST464 (n = 4; 9%), ST9882 (n = 4; 9%), ST354 (n = 3; 7%), ST572 (n = 3; 7%), and ST7355 (n = 3; 7%). Most prevalent genotypes for C. coli (n = 10) were ST832 (n = 4; 40%), ST872 (n = 4; 40%).

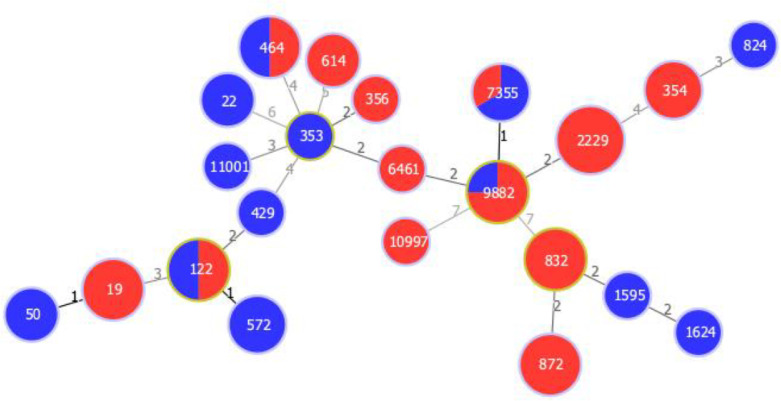

C. jejuni ST10997 was only present in one Estonian origin of sample. ST356 and ST2229 were present in Latvian origin of C. jejuni samples. ST19, ST354, ST614, ST6461, ST122, ST464, ST7355, and ST9882 were present in Lithuanian origin of C. jejuni and ST872 in C. coli samples. ST832 was detected in samples of both Latvian and Lithuanian origin C. coli isolates. In our study genotypes ST122, ST464, ST7355, and ST9882 were obtained from both fresh chicken meat and from human Campylobacter isolates (Figure 2). However, no common genotypes for isolates originating from all 3 countries were found in present study.

Figure 2.

Full minimum spanning tree (MST) of 55 Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli MLST allelic profiles. Nodes are named after STs and color-coded according to isolate sources: chicken (red) and human (blue). Links are labelled with number of allelic differences.

Mäesaar et al. (2018) observed ST353 as the most prevalent genotype from human clinical C. jejuni isolates and ST5, ST45, and ST50 as the most prevalent STs from poultry chicken meat isolates. In current study Campylobacter spp. isolates from human patients (n = 20) were assigned to 2 species C. jejuni (n = 18) and C. coli (n = 2). In combined 13 different STs were detected, where the most prevalent STs were C. jejuni ST572 (n = 3; 15%), ST22 (n = 2; 10%), ST50 (n = 2; 10%), ST122 (n = 2; 10%), ST464 (n = 2; 10%), and ST7355 (n = 2; 10%). The isolates from broiler chicken meat (n = 35) were similarly assigned to 2 species 27 C. jejuni and 8 C. coli. Additionally, 13 different STs were assigned and the most prevalent STs for C. jejuni were ST2229 (n = 7; 26%), ST19 (n = 4; 15%) and for C. coli ST832 (n = 4; 50%) and ST872 (n = 4; 50%). Very few persistent Campylobacter genotypes were observed between mentioned studies performed in Estonia.

Meistere et al. (2019) found genotype ST464 to be present in one C. jejuni human isolate in their Campylobacter species prevalence study conducted in Latvia. According to Aksomaitiene et al. (2019) the majority of C. jejuni strains from broiler products in Lithuania were assigned to genotype ST464. Similarly in the Polish study the ST464 was one of the most common genotype detected both from chickens and humans (Wieczorek et al., 2020). In present study the genotype ST464 was also present both in human and chicken meat Campylobacter isolates, which indicates poultry as a potential reservoir and source of human Campylobacter infections.

Further research is needed to study other possible sources (pig, cattle, sheep, and pet animal) of Campylobacter human infections in Estonia. Limited sample size regarding genotyping analyses should be taken into account while interpreting the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Present study found that Campylobacter prevalence and counts in fresh broiler chicken meat was significantly lower in samples of Estonian origin compared to these originating from Latvia and Lithuania and sold at Estonian retail level. Imported fresh broiler chicken meat carries higher human campylobacteriosis risk in Estonia compare to fresh broiler chicken meat produced in Estonia. High genotype diversity among Campylobacter isolates from fresh retail chicken meat in Estonia was found. Only isolates originating from Lithuanian broiler chicken meat products were overlapping with isolates obtained from human patients of Estonia. Genotyping indicated associations between imported fresh broiler chicken products with campylobacteriosis cases in Estonia. Campylobacter counts in Estonian and imported products decreased compared with earlier study periods. Over time significant decrease in the prevalence and concentration of Campylobacter in Estonian broiler chicken meat indicates the possibility to reduce Campylobacter contamination by application of effective biosafety and other control measures within entire meat production chain.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the Health Board of Estonia for providing clinical Campylobacter isolates. We thank Viorel Revenco for laboratory assistance. This study was supported by the Estonian University of Life Sciences basic financing project P180279VLTR (MR) and by the WORLDCOM project of the One Health European Joint Programme (OHEJP) consortium and received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme [grant number 773830] (VK)

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2022.101703.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Aksomaitiene J., Ramonaite S., Tamuleviciene E., Novoslavskij A., Alter T., Malakauskas M. Overlap of antibiotic resistant Campylobacter jejuni MLST genotypes isolated from humans, broiler products, dairy cattle and wild birds in Lithuania. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1377. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., Pyshkin A.V. Spades: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunevičienė J., Kudirkienė E., Ramonaitė S., Malakauskas M. Occurrence and numbers of Campylobacter spp. on wings and drumsticks of broiler chickens at the retail level in Lithuania. Vet. Zootech. 2010;72:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E.N.N.E., Hahné M. Cross-contamination with Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella spp. from raw chicken products during food preparation. J. Food Prot. 1990;53:1067–1068. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.12.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djennad A., Iacono G.L., Sarran C., Lane C., Elson R., Höser C., Lake I.R., Colón-González F.J., Kovats S., Semenza J.C., Bailey T.C. Seasonality and the effects of weather on Campylobacter infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3840-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018;16:e05500. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estonian Health Board. (2021). Communicable disease bulletins. Accessed Jan. 2022. https://www.terviseamet.ee/en/communicable-diseases/communicable-disease-bulletins.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) The European Union one health 2019 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2021;19:e06406. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco A.P., Bugalho M., Ramirez M., Carriço J.A. Global optimal eBURST analysis of multilocus typing data using a graphic matroid approach. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez L., Melero B., Jaime I., Hänninen M.L., Rossi M., Rovira J. Campylobacter jejuni survival in a poultry processing plant environment. Food Microbiol. 2017;65:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons C.L., Mangen M.J.J., Plass D., Havelaar A.H., Brooke R.J., Kramarz P., Peterson K.L., Stuurman A.L., Cassini A., Fèvre E.M., Kretzschmar M.E. Measuring underreporting and under-ascertainment in infectious disease datasets: a comparison of methods. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntar I., Biasizzo M., Kušar D., Pate M., Ocepek M. Campylobacter jejuni contamination of broiler carcasses: population dynamics and genetic profiles at slaughterhouse level. Food Microbiol. 2015;50:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T., O'Brien S., Madsen M. Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;117:237–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola, S., O. Lyytikäinen, S. Huusko, S. Salmenlinna, J. Pirhonen, C. Savolainen-Kopra, K. Liitsola, J. Jalava, M. Toropainen, H. Nohynek, M. Virtanen. 2015.. Infectious diseases in Finland 2014, National Institute of Health and Welfare, 14:1–70. Accessed Jan. 2022. https://www.terviseamet.ee/en/communicable-diseases/communicable-disease-bulletins.

- Jolley K.A., Maiden M.C. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen F., Madden R.H., Arnold E., Charlett A., Elviss N.C. Food Standards Agency; London, UK: 2015. FSA Project fs241044-Survey Report-A Microbiological Survey of Campylobacter Contamination in Fresh Whole UK Produced Chilled Chickens at Retail Sale (2014-15)https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/Final%20Report%20for%20FS241044%20Campylobacter%20Retail%20survey.pdf Accessed Jan. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keener K.M., Bashor M.P., Curtis P.A., Sheldon B.W., Kathariou S. Comprehensive review of Campylobacter and poultry processing. Compreh. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2004;3:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2004.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsak D., Maćkiw E., Rożynek E., Żyłowska M. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail chicken, turkey, pork, and beef meat in Poland between 2009 and 2013. J. Food Prot. 2015;78:1024–1028. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanen S.M., Kivistö R.I., Rossi M., Schott T., Kärkkäinen U.M., Tuuminen T., Uksila J., Rautelin H., Hänninen M.L. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and whole-genome MLST of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from human infections in three districts during a seasonal peak in Finland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:4147–4154. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01959-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko K., Roasto M., Liepinš E., Mäesaar M., Hörman A. High occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in Latvian broiler chicken production. Food Control. 2013;29:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- Meistere I., Ķibilds J., Eglīte L., Alksne L., Avsejenko J., Cibrovska A., Makarova S., Streikiša M., Grantiņa-Ieviņa L., Bērziņš A. Campylobacter species prevalence, characterisation of antimicrobial resistance and analysis of whole-genome sequence of isolates from livestock and humans, Latvia, 2008 to 2016. Eurosurveillance. 2019;24 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.31.1800357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meremäe K., Elias P., Tamme T., Kramarenko T., Lillenberg M., Karus A., Hänninen M.L., Roasto M. The occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in Estonian broiler chicken production in 2002–2007. Food Control. 2010;21:272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mäesaar M., Meremäe K., Ivanova M., Roasto M. Antimicrobial resistance and multilocus sequence types of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from Baltic broiler chicken meat and Estonian human patients. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:3645–3651. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäesaar M., Praakle K., Meremäe K., Kramarenko T., Sõgel J., Viltrop A., Muutra K., Kovalenko K., Matt D., Hörman A., Hänninen M.L. Prevalence and counts of Campylobacter spp. in poultry meat at retail level in Estonia. Food Control. 2014;44:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mäesaar M., Tedersoo T., Meremäe K., Roasto M. The source attribution analysis revealed the prevalent role of poultry over cattle and wild birds in human campylobacteriosis cases in the Baltic States. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento M., Sousa A., Ramirez M., Francisco A.P., Carriço J.A., Vaz C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: providing scalable data integration and visualization for multiple phylogenetic inference methods. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:128–129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastasijevic I., Proscia F., Boskovic M., Glisic M., Blagojevic B., Sorgentone S., Kirbis A., Ferri M. The European Union control strategy for Campylobacter spp. in the broiler meat chain. J. Food Saf. 2020;40:e12819. [Google Scholar]

- Newell D.G., Fearnley C.J.A.E.M. Sources of Campylobacter colonization in broiler chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4343–4351. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4343-4351.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2021. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing.https://www.R-project.org/ Accessed Jan. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roasto M., Kovalenko K., Praakle-Amin K., Meremäe K., Tamme T., Kramarenko T. Review of the contamination and health risks related to Campylobacter spp. and Listeria monocytogenes in the food supply with special reference to Estonia and Latvia. Agronomy Res. 2010;8:333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Roasto M., Praakle K., Korkeala H., Elias P., Hanninen M. Prevalence of Campylobacter in raw chicken meat of Estonian origin. Archiv fur Lebensmittelhygiene. 2005;56:61. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B.M., Schielke A., Didelot X., Kops F., Breidenbach J., Willrich N., Gölz G., Alter T., Stingl K., Josenhans C., Suerbaum S. A combined case-control and molecular source attribution study of human Campylobacter infections in Germany, 2011–2014. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossler E., Signorini M.L., Romero-Scharpen A., Soto L.P., Berisvil A., Zimmermann J.A., Fusari M.L., Olivero C., Zbrun M.V., Frizzo L.S. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of thermotolerant Campylobacter in food-producing animals worldwide. Zoonoses Public Health. 2019;66:359–369. doi: 10.1111/zph.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleha A.A., Mead G.C., Ibrahim A.L. Campylobacter jejuni in poultry production and processing in relation to public health. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 1998;54:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y., Maruyama N., Zou B., Haruna M., Kusukawa M., Murakami M., Asai T., Tsujiyama Y., Yamada Y. Campylobacter cross-contamination of chicken products at an abattoir. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013;60:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarp C.P.A., Hänninen M.L., Rautelin H.I.K. Campylobacteriosis: the role of poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella S., Soncini G., Ziino G., Panebianco A., Pedonese F., Nuvoloni R., Di Giannatale E., Colavita G., Alberghini L., Giaccone V. Prevalence and quantification of thermophilic Campylobacter spp. in Italian retail poultry meat: analysis of influencing factors. Food Microbiol. 2017;62:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Yamamoto S. Campylobacter contamination in retail poultry meats and by-products in the world: a literature survey. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009;71:255–261. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarski Y. Epidemiology and prevalence of Campylobacter infections in the European Union and Bulgaria between 2010 and 2017 (A Review) Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2019;22:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). The global view of campylobacteriosis: report of an expert consultation, Utrecht, Netherlands, 9-11 July 2012.

- Wieczorek K., Wołkowicz T., Osek J. MLST-based genetic relatedness of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chickens and humans in Poland. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yushina Y., Bataeva D., Makhova A., Zayko E. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in a poultry and pork processing plants. Slovak. J. Food Sci. 2020;14:815–820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.