Abstract

Background:

Despite potential harm that can result from polypharmacy, real-world data on polypharmacy in the setting of heart failure (HF) are limited. We sought to address this knowledge gap by studying older adults hospitalized for HF derived from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Methods:

We examined 558 older adults aged ≥65 years with adjudicated HF hospitalizations from 380 hospitals across the United States. We collected and examined data from the REGARDS baseline assessment, medical charts from HF-adjudicated hospitalizations, the American Hospital Association annual survey database, and Medicare’s Hospital Compare website. We counted the number of medications taken at hospital admission and discharge; and classified each medication as HF-related, non-HF cardiovascular-related, or non-cardiovascular-related.

Results:

The vast majority of participants (84% at admission and 95% at discharge) took ≥5 medications; and 42% at admission and 55% at discharge took ≥10 medications. The prevalence of taking ≥10 medications (polypharmacy) increased over the study period. As the number of total medications increased, the number of non-cardiovascular medications increased more rapidly than the number of HF-related or non-HF cardiovascular medications.

Conclusion:

Defining polypharmacy as taking ≥10 medications might be more ideal in the HF population as most patients already take ≥5 medications. Polypharmacy is common both at admission and hospital discharge, and its prevalence is rising over time. The majority of medications taken by older adults with HF are non-cardiovascular medications. There is a need to develop strategies that can mitigate the negative effects of polypharmacy among older adults with HF.

Keywords: polypharmacy, heart failure

Subject Term List: Heart Failure and Cardiac Disease, Heart Failure

Introduction

With an expanding armamentarium of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) to treat heart failure (HF), polypharmacy, broadly defined as the use of a high number of medications, has become increasingly relevant for older adults with HF. Indeed, with recent approval of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF),1 there are now 10 different classes of GDMT for HFrEF, many of which are recommended for concurrent use.2, 3 Older adults with HF also contend with multiple chronic conditions— over 60% of Medicare beneficiaries with HF have at least 5 other chronic medical conditions—which further contributes to their medication burden.4 Polypharmacy is important because it is associated with a myriad of adverse outcomes5, 6 including falls,7–9 disability,10–12 and hospitalizations.13, 14 This is especially relevant for older adults with HF, which is a population that is particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of polypharmacy due to age-related alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,15 changes in cardiovascular structure and function,16 and the coexistence of geriatric conditions like frailty17 and cognitive impairment.18

Despite the potential harm that can result from polypharmacy, real-world detailed information on polypharmacy in the setting of HF are limited. Characterizing medication patterns specifically around the time of a hospitalization is especially important because this is a period when medication errors and subsequent adverse drug events are common.19 We therefore sought to better understand polypharmacy in the context of a HF hospitalization by studying a cohort of older adults hospitalized for HF derived from the geographically-diverse Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Methods

Study Population:

We examined adjudicated HF hospitalizations of Medicare beneficiaries aged at least 65 years who were hospitalized between 2003 and 2014. The study sample was a subset of participants from the REGARDS study, which is a national population-based prospective observational cohort of 30,239 community-dwelling black and white men and women aged ≥45 years from all 48 contiguous states in the United States and the District of Columbia originally recruited from 2003–2007.20 The REGARDS study team used commercially-available lists of residents for recruitment. Baseline data collection included a 45-minute telephone interview followed approximately one month later by an in-home visit, when blood and urine samples as well as physiologic measures were obtained. For follow-up, participants received routine telephone calls every 6 months and reported if they had been hospitalized for a cardiovascular condition including HF. Two expert clinicians reviewed the hospitalization records of participants who reported a cardiovascular-related hospitalization to determine if the reason for hospitalization included a HF exacerbation, using a structured adjudication process. Adjudication was based on consideration of clinical presentation which included symptoms, physical exam findings, laboratory values, imaging, and medical treatments. In cases of disagreement, a committee made the final decision.

The medical records of participants hospitalized for HF were manually abstracted using a process previously described.21 We excluded participants who did not have medication data at both hospital admission and hospital discharge (N=132), and those who were referred to hospice at the time of discharge (N=25) (Supplemental Figure 1). Of note, prior work using this cohort has shown that there were few differences between individuals with medication data and those without medication data at both admission and discharge.21

All participants received information about the study and provided consent at the time of their enrollment. The REGARDS study previously had approvals from the Institutional Review Boards governing research in human subjects at the participating centers. Additionally, Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this ancillary study.

Data Sources:

For this study, we used data from the REGARDS baseline assessment, medical charts from adjudicated HF hospitalizations, the American Hospital Association annual survey database, and Medicare’s Hospital Compare website.

REGARDS baseline data included sex, race, education level, household income, and geriatric conditions. Geriatric conditions included functional impairment (defined as physical component summary score from the Short Form 12 as <30), cognitive impairment (defined as a six-item screener score of <5)22, history of falls (defined as having at least one self-reported fall), and hypoalbuminemia (which has been described as a marker of frailty and is defined as albumin level ≤3.3 grams/deciliter).23

Documents from each adjudicated HF hospitalization available for chart review included admission and progress notes, consultation notes, discharge summaries, medication reconciliation reports, laboratory and diagnostic testing reports, and nursing notes. For this study, we examined number of standing medications at admission and discharge (defining polypharmacy as taking at least 10 medications), echocardiogram parameters including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), intensive care unit (ICU) stay, inpatient cardiology consultation, length of stay, discharge to home, and discharge year.

We also stratified patients by LVEF and examined them in two groups—we defined heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) as those with an LVEF<50% (inclusive of those with a mid-range or borderline ejection fraction) and/or a qualitative description of abnormal systolic function;2, 3, 24 and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as those with LVEF ≥50% and/or a qualitative description of normal systolic function.2, 3

We classified medications according to the Multum Lexicon Drug Database,25 which then facilitated a broader classification scheme of three major medication groups—HF medications, non-HF cardiovascular medications, and non-cardiovascular medications. These classifications were based on direct indications. For example, supplemental potassium was considered a non-cardiovascular medication because it is indicated for hypokalemia, even though hypokalemia often results from the use of diuretics (a HF medication).

We also used the survey database of the American Hospital Association, which collects data annually on approximately 6500 hospitals and over 400 health systems across the United States, to examine teaching status and hospital size (small hospital size defined as <200 beds); and Medicare’s Hospital Compare website that includes data about the quality of care of over 4000 Medicare-certified hospitals to examine hospital rating (range of 1–5, with 3 being average and a higher score of 5 reflecting higher quality care) corresponding to the year of hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

We calculated medians and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for categorical variables to summarize participant and hospital characteristics, comparing participants taking <10 medications with those taking ≥10 medications at both admission and discharge. We compared participant and hospital characteristics using the Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Pearson chi-square for categorical variables. To assess for the unadjusted temporal trends of polypharmacy over the study period, we used Poisson regression with robust error variance.

We conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify the determinants of polypharmacy. We chose variables for the model based on published literature, prior knowledge, and clinical judgment; these included socio-demographics (age ≥75, sex, race, education, household income), heart failure subtype (HFpEF vs. HFrEF), geriatric conditions (functional impairment, cognitive impairment, history of falls, and hypoalbuminemia), a count of comorbid conditions, hospitalization factors (ICU stay, inpatient cardiology consultation, length of stay, discharge to home, and discharge year after 2010), and hospital characteristics (teaching status, hospital size, and Medicare hospital rating).

Results

We examined 558 older adults hospitalized for HF at 380 different hospitals across the United States (Supplemental Figure 1). The median age of the sample was 76 (interquartile range 72–83), 44% were female, and 34% were black (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population and Hospital Characteristics, According to Polypharmacy (at least 10 medications) at Admission and Discharge

| At Admission | At Discharge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=558) | < 10 Medications (n=322) | ≥ 10 Medications (n=236) | P-value | < 10 Medications (n=252) | ≥ 10 Medications (n=306) | P-value | |

| SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS (%) | |||||||

| Age, median (±IQR) | 76.0 (72.0–82.0) | 76.5 (72.0–83.0) | 76.0 (71.0–82.0) | 0.27 | 76.0 (72.0–83.0) | 76.0 (71.0–82.0) | 0.48 |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 326 (58.4%) | 195 (60.6%) | 131 (55.5%) | 0.23 | 151 (59.9%) | 175 (57.2%) | 0.51 |

| Female | 243 (43.5%) | 138 (42.9%) | 105 (44.5%) | 0.70 | 104 (41.3%) | 139 (45.4%) | 0.32 |

| Black Race | 189 (33.9%) | 116 (36.0%) | 73 (30.9%) | 0.21 | 87 (34.5%) | 102 (33.3%) | 0.77 |

| Education high school or below | 292 (52.3%) | 167 (51.9%) | 125 (53.0%) | 0.91 | 135 (53.6%) | 157 (51.3%) | 0.92 |

| Household income <$20,000 | 156 (28.0%) | 96 (29.8%) | 60 (25.4%) | 0.48 | 147 (58.3%) | 185 (60.5%) | 0.36 |

| GERIATRIC CONDITIONS (%) | |||||||

| Functional Impairment | 117 (21.0%) | 56 (17.4%) | 61 (25.8%) | 0.02 | 47 (18.7%) | 70 (22.9%) | 0.32 |

| Cognitive Impairment | 90 (16.1%) | 54 (16.8%) | 36 (15.3%) | 0.38 | 46 (18.3%) | 44 (14.4%) | 0.12 |

| History of falls | 120 (21.5%) | 59 (18.3%) | 61 (25.8%) | 0.03 | 47 (18.7%) | 73 (23.9%) | 0.13 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 218 (39.1%) | 128 (39.8%) | 90 (38.1%) | 0.56 | 101 (40.1%) | 117 (38.2%) | 0.89 |

| CO-MORBIDITIES (%) | |||||||

| Comorbidity Count, median (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (3–6) | 6 (5–8) | <.0001 | 5 (3–6) | 6 (5–8) | <.0001 |

| HFpEF | 235 (42.1%) | 136 (42.2%) | 99 (41.9%) | 0.84 | 103 (40.9%) | 132 (43.1%) | 0.77 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 395 (70.8%) | 216 (67.1%) | 179 (75.8%) | 0.02 | 166 (65.9%) | 229 (74.8%) | 0.02 |

| History of Revascularization | 214 (38.4%) | 104 (32.3%) | 110 (46.6%) | <0.001 | 77 (30.6%) | 137 (44.8%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 235 (42.1%) | 126 (39.1%) | 109 (46.2%) | 0.10 | 106 (42.1%) | 129 (42.2%) | 0.98 |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | 46 (8.2%) | 27 (8.4%) | 19 (8.1%) | 0.89 | 16 (6.3%) | 30 (9.8%) | 0.14 |

| Hypertension | 431 (77.2%) | 243 (75.5%) | 188 (79.7%) | 0.27 | 185 (73.4%) | 246 (80.4%) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes | 258 (46.2%) | 126 (39.1%) | 132 (55.9%) | <0.001 | 97 (38.5%) | 161 (52.6%) | <0.001 |

| CVA/TIA | 102 (18.3%) | 53 (16.5%) | 49 (20.8%) | 0.19 | 37 (14.7%) | 65 (21.2%) | 0.05 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 108 (19.4%) | 50 (15.5%) | 58 (24.6%) | 0.008 | 41 (16.3%) | 67 (21.9%) | 0.09 |

| COPD | 186 (33.3%) | 91 (28.3%) | 95 (40.3%) | 0.003 | 67 (26.6%) | 119 (38.9%) | 0.002 |

| Asthma | 55 (9.9%) | 25 (7.8%) | 30 (12.7%) | 0.05 | 20 (7.9%) | 35 (11.4%) | 0.17 |

| Liver Disease | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.83 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.89 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 201 (36.0%) | 99 (30.7%) | 102 (43.2%) | 0.002 | 66 (26.2%) | 135 (44.1%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 86 (15.4%) | 52 (16.1%) | 34 (14.4%) | 0.57 | 42 (16.7%) | 44 (14.4%) | 0.46 |

| Anemia | 153 (27.4%) | 71 (22.0%) | 82 (34.7%) | <0.001 | 58 (23.0%) | 95 (31.0%) | 0.03 |

| Osteoarthritis | 148 (26.5%) | 82 (25.5%) | 66 (28.0%) | 0.51 | 71 (28.2%) | 77 (25.2%) | 0.42 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 61 (10.9%) | 29 (9.0%) | 32 (13.6%) | 0.09 | 22 (8.7%) | 39 (12.8%) | 0.13 |

| HOSPITALIZATION DATA (%) | |||||||

| Intensive Care Unit Stay | 116 (20.8%) | 73 (22.7%) | 43 (18.2%) | 0.20 | 47 (18.7%) | 69 (22.6%) | 0.26 |

| Cardiology Consultation | 391 (70.1%) | 231 (71.7%) | 160 (67.8%) | 0.32 | 175 (69.4%) | 216 (70.6%) | 0.77 |

| Length of Stay, median days (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 0.15 | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 0.88 |

| Discharge to Home | 456 (81.7%) | 264 (81.9%) | 192 (81.4%) | 0.39 | 217 (86.1%) | 239 (78.1%) | 0.01 |

| Discharge year (after 2010) | 137 (24.6%) | 62 (19.3%) | 75 (31.8%) | 0.001 | 44 (17.5%) | 93 (30.4%) | 0.0004 |

| HOSPITAL CHARACTERISTICS (%) | |||||||

| Teaching Hospital | 270 (48.4%) | 164 (50.9%) | 106 (44.9%) | 0.16 | 118 (46.8%) | 152 (49.7%) | 0.51 |

| Small Hospital size (<200 beds) | 135 (24.2%) | 77 (23.9%) | 58 (24.6%) | 0.85 | 71 (28.2%) | 64 (20.9%) | 0.05 |

| Hospital Rating below average (<3) | 179 (32.1%) | 112 (34.8%) | 67 (28.4%) | 0.08 | 82 (32.5%) | 97 (31.7%) | 0.63 |

COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; HFpEF, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IQR, Interquartile range; TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack

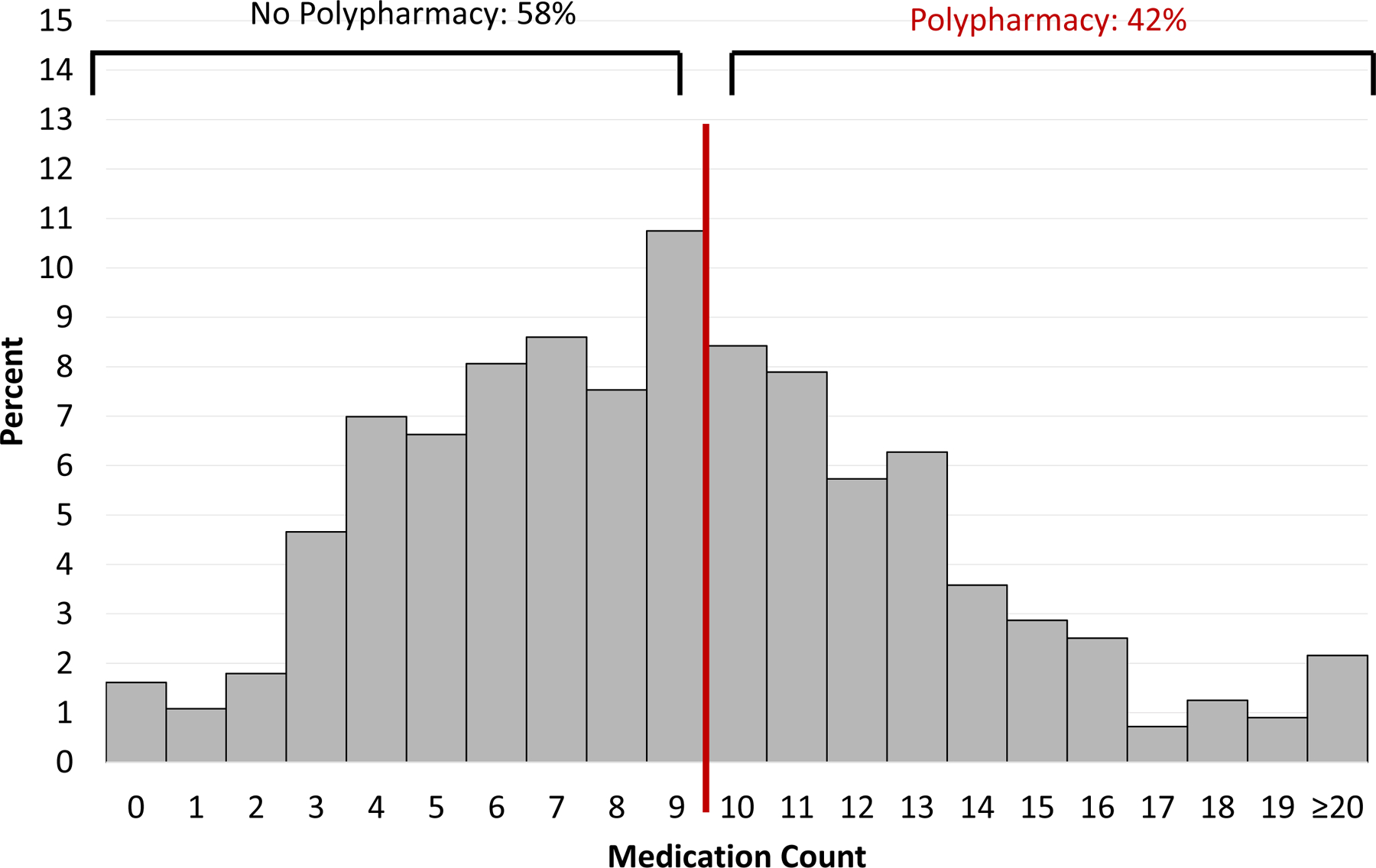

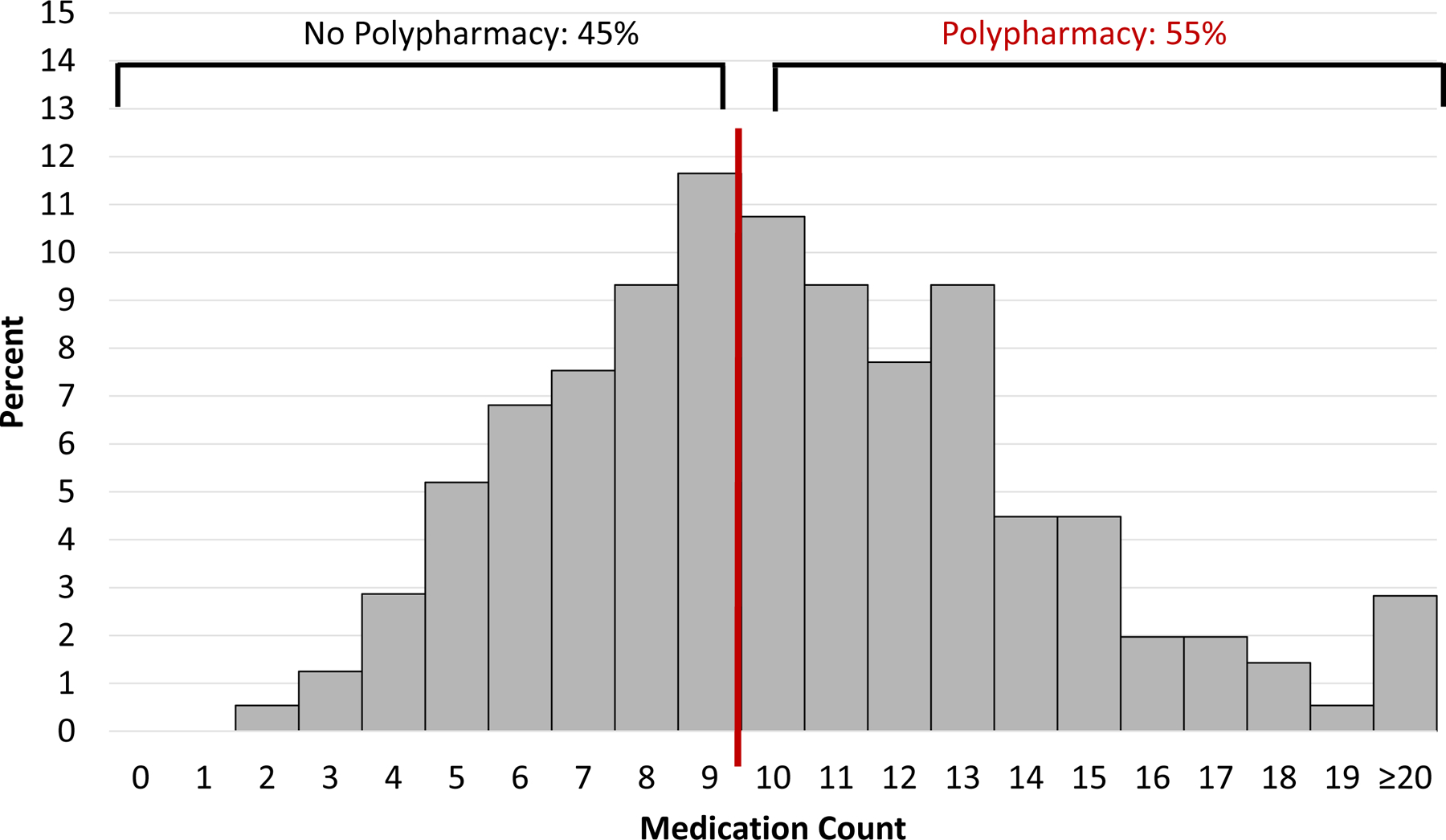

Histograms showing the frequency of medication counts at hospital admission and discharge are shown in Figure 1A and 1B. The vast majority of older adults with HF took at least 5 medications (84% at admission and 95% at discharge), and approximately half took at least 10 medications, which we define here as polypharmacy (42% at admission and 55% at discharge). These patterns were similar for those with HFrEF and HFpEF (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). The median number of medications taken by those with polypharmacy at admission was 12 (IQR 11–14) and at discharge was 12 (IQR 11–14); and the median number of medications taken by those without polypharmacy at admission was 6 (IQR 4–8) and at discharge was 7 (IQR 6–9). Those with polypharmacy had a higher median comorbidity count on both admission and discharge and higher prevalence of functional impairment upon admission. There were no significant differences in age, race, sex, education level, or household income between those with and without polypharmacy at either admission and discharge (Table 1). We found similar patterns for both HFrEF and HFpEF (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of medication count.

Polypharmacy, defined as the condition of taking at least 10 medications, occurred in 42% of adults with heart failure at hospital admission (A) and 55% at hospital discharge (B)

A. At Hospital Admission

B. At Hospital Discharge

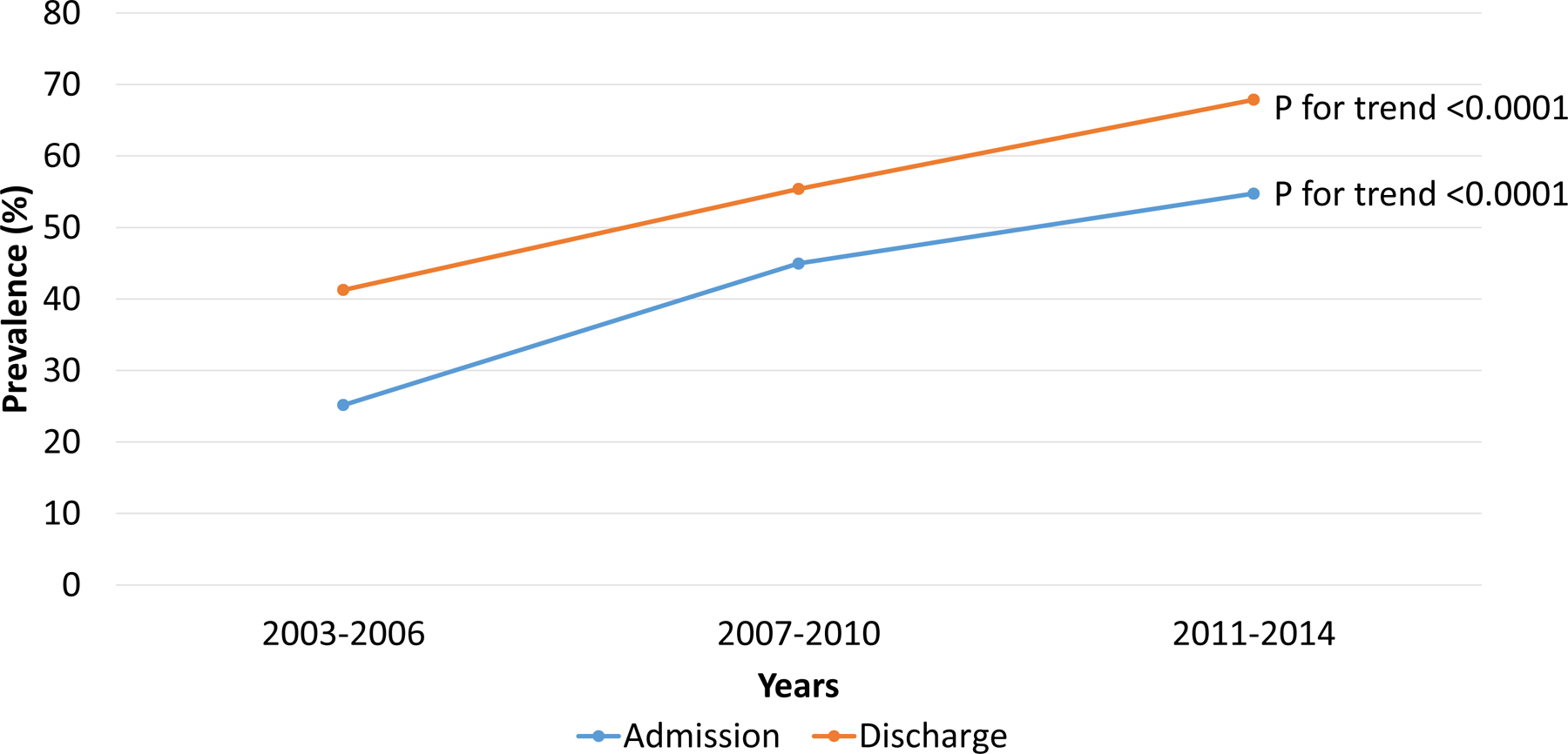

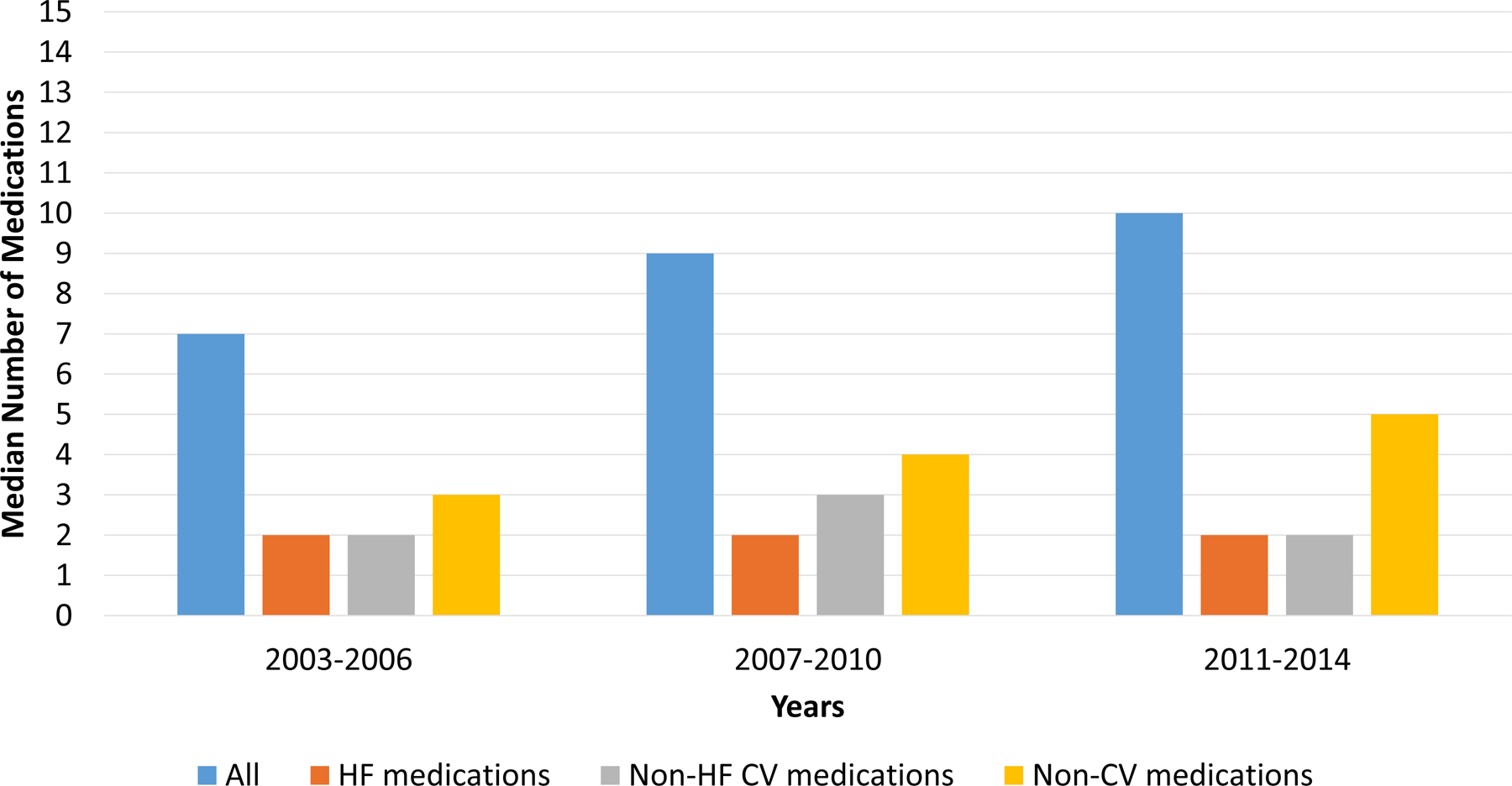

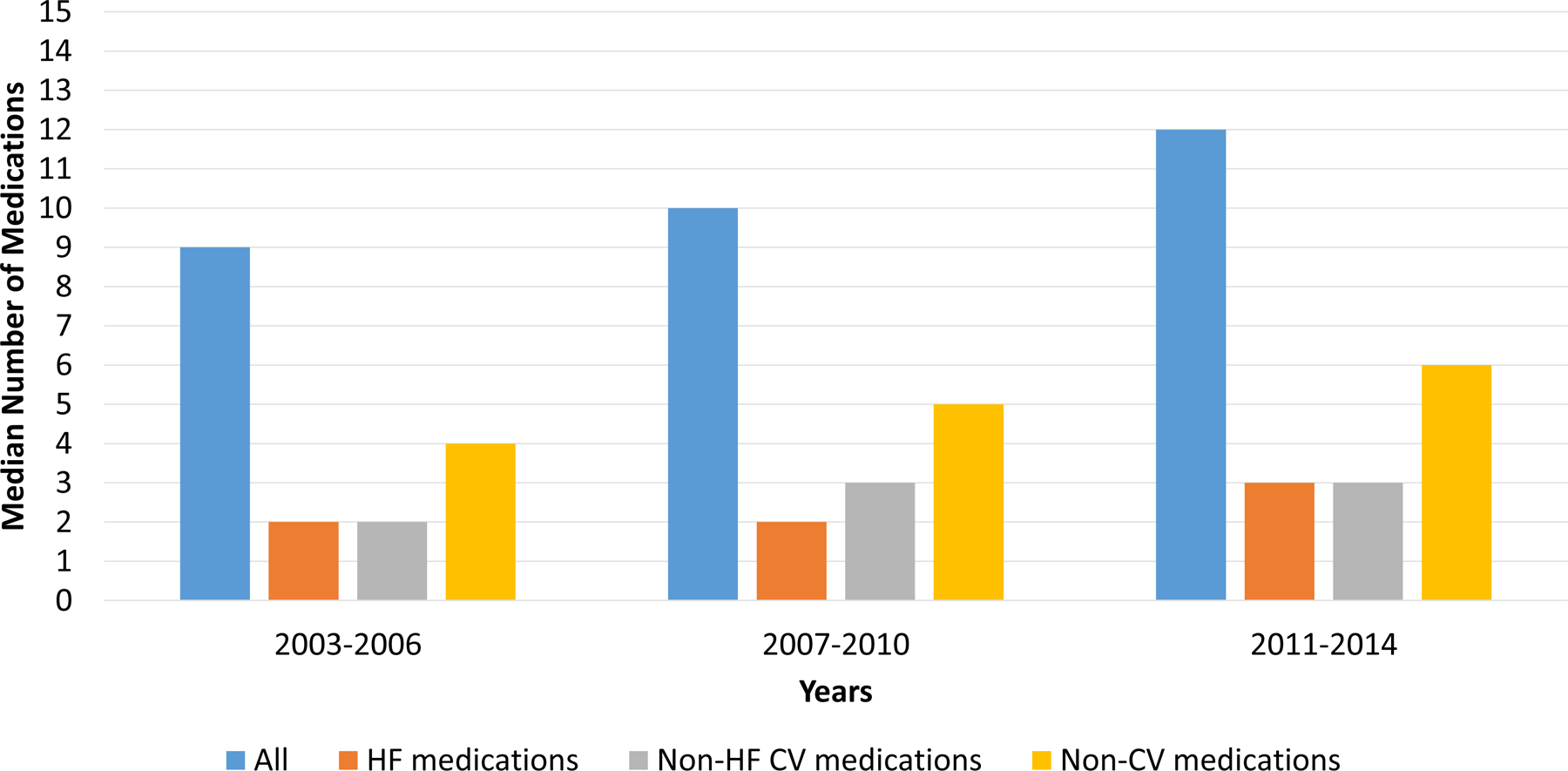

The prevalence of polypharmacy at hospital admission increased from 25% in 2003–2006 to 55% in 2011–2014 (p for trend<0.0001), and at hospital discharge increased from 41% in 2003–2006 to 68% in 2011–2014 (p for trend<0.0001) (Figure 2). Similar trends were observed when HFrEF and HFpEF participants were analyzed separately, with a higher numerical increase among those with HFpEF (Supplemental Figure 4). The increase in medication count over time was greatest among non-cardiovascular medications at both admission (Figure 3A) and discharge (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Temporal Trends of Polypharmacy.

Polypharmacy, defined as the condition of taking at least 10 medications, at both admission and discharge increased in prevalence between the 2003–2006 period and 2011–2014 period.

Figure 3. Median Number of Medications by Medication Classes Over Time.

The median number of medications increased over time. This increase was most notable among non-cardiovascular (non-CV) medications. Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; Non-CV, Non-cardiovascular

A. At Hospital Admission

B. At Hospital Discharge

Between hospital admission and hospital discharge, the prevalence of polypharmacy increased from 42% to 55% (p<0.001). Between admission and discharge, the median number of all medications increased from 9.0 to 10.0 (p<.0001), the median number of HF medications increased from 2 to 2.5 (p<.0001), the median number of non-HF cardiovascular medications increased from 2 to 3 (p<.0001), and the median number of non-cardiovascular medications increased from 4 to 4.5 (p<.0001). The most commonly initiated medications are shown in Table 2. As shown, loop diuretics, beta-blockers, aspirin, and electrolyte supplements were the most commonly initiated medications between admission and discharge. These patterns were similar for both HFrEF and HFpEF (Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 5).

Table 2.

Most Common Medications Initiated Between Admission and Discharge

| Medication | Number (Percentage)* | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loop Diuretics | 149 (27%) |

| 2 | Beta-blockers | 116 (21%) |

| 3 | Aspirin | 105 (19%) |

| 4 | Electrolyte Supplements | 97 (17%) |

| 5 | ACE inhibitors | 95 (17%) |

| 6 | Quinolones | 67 (12%) |

| 7 | Anticoagulation | 67 (12%) |

| 8 | Proton Pump Inhibitors | 64 (11%) |

| 9 | Statins | 61 (11%) |

| 10 | P2Y12 inhibitors | 57 (10%) |

| 11 | Adrenergic Bronchodilators | 54 (10%) |

| 12 | Multivitamins | 46 (8%) |

| 13 | Nitrates | 44 (8%) |

| 14 | Anti-arrhythmic | 44 (8%) |

| 15 | MRA | 36 (6%) |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme

MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

Percentages calculated by using total number of patients (N=558)

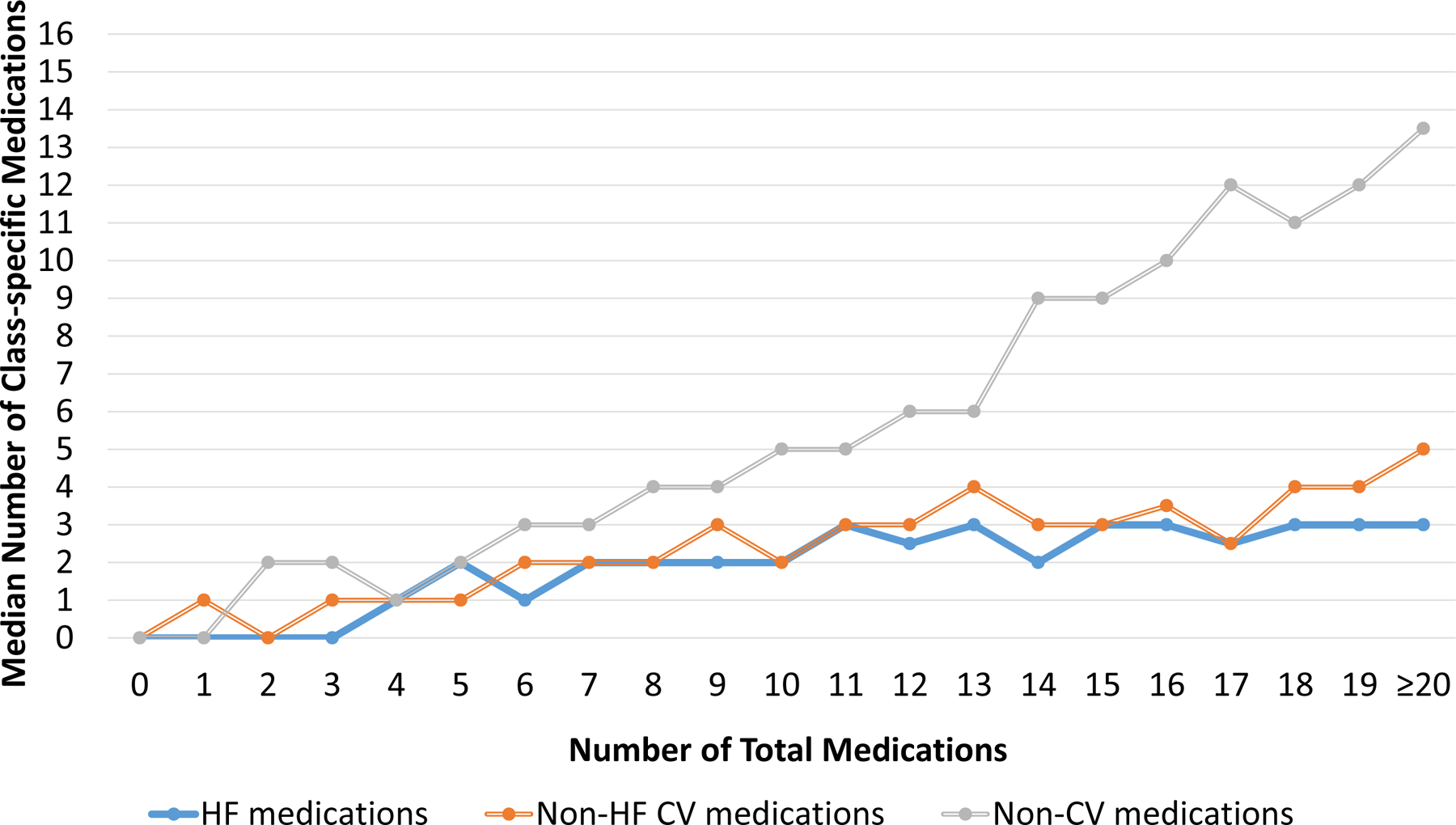

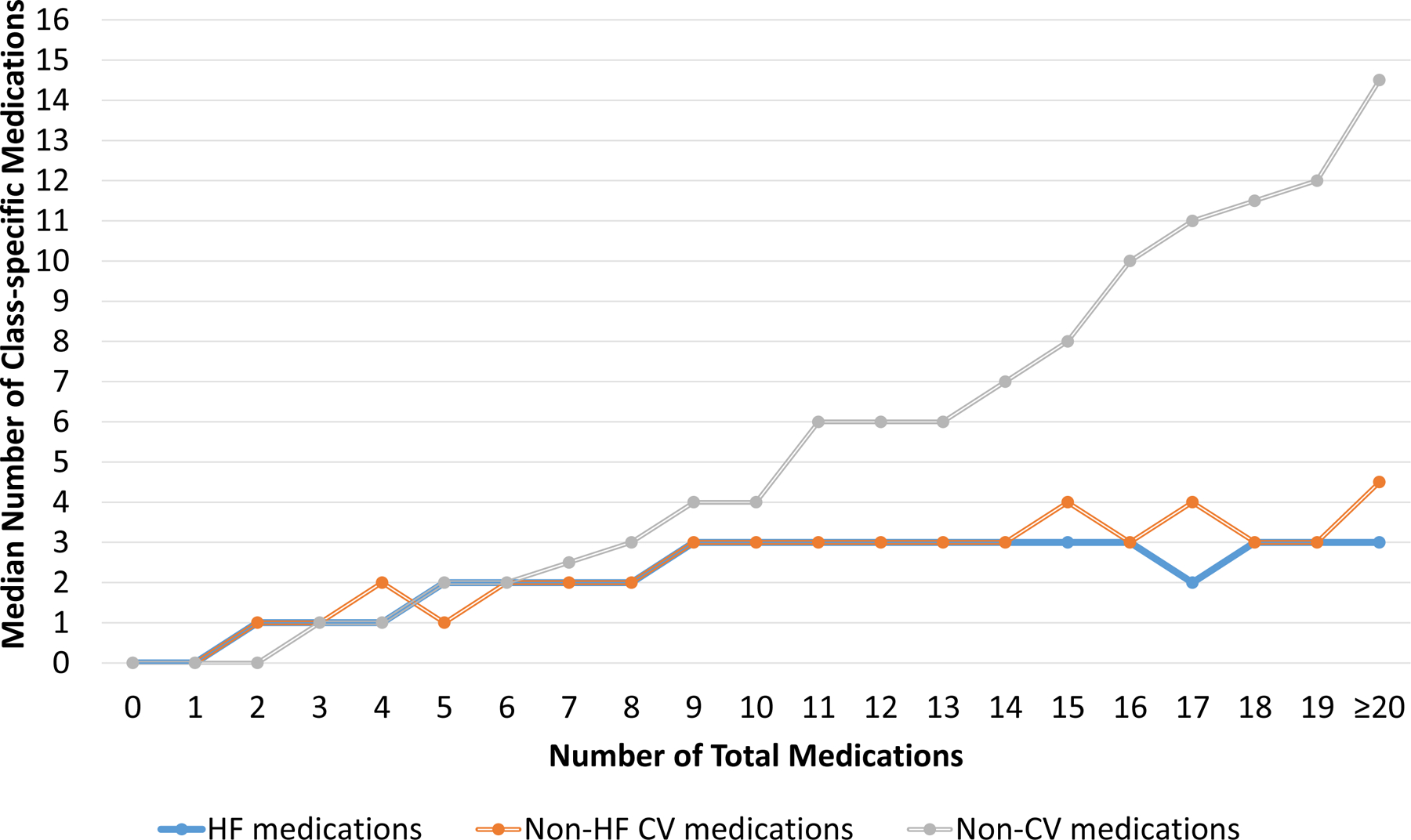

The most common class of medications at both admission and discharge were non-cardiovascular medications. Upon admission, non-cardiovascular medications comprised a median of 50.0% (IQR 33.3–66.7%) of medications, while HF medications comprised a median of 20.0% (IQR 11.1–30.8%) and other non-HF cardiovascular medications comprised a median of 25.0% (16.7–36.4%). At discharge, non-cardiovascular medications comprised a median of 46.7% (IQR 33.3–60%) of medications, while HF medications comprised a median of 25.0% (IQR 16.7–33.3%) and other non-HF cardiovascular medications comprised a median of 26.7% (IQR 17.6–36.4%). These patterns were similar for both HFrEF and HFpEF (Supplemental Figure 5). As the total medications at both admission and discharge increased, the number of non-cardiovascular medications increased at a faster rate than the number of either HF medications or non-HF cardiovascular medications at both admission and discharge (Figure 4). This was consistent for both HFrEF (Supplemental Figure 6) and HFpEF (Supplemental Figure 7). Table 3 shows the most common HF medications, non-HF cardiovascular medications, and non-cardiovascular medications taken at admission and discharge. As shown, beta-blockers were the most common HF medications; aspirin and statins were the most common non-HF cardiovascular medications; and proton pump inhibitors, electrolyte supplements, and multivitamins were the most common non-cardiovascular medications taken. These patterns were consistent for both HFrEF and HFpEF (Supplemental Table 3). Although not among the top 5 most common HF medications, it was notable that mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists were prescribed to 38 (6.8%) patients on admission and 64 (11.5%) patients on discharge.

Figure 4. Medication Class Counts According to Total Medication Count.

As the number of total medications increased, the number of non-cardiovascular (non-CV) medications increased more rapidly compared to either heart failure (HF) medications or non-HF cardiovascular (CV) medications at both admission (A) and discharge (B). Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; Non-CV, Non-cardiovascular

A. At Hospital Admission

B. At Hospital Discharge

Table 3.

Most Common Medications Prescribed at Admission and at Discharge, Stratified by Medication Class

| HF* | Non-HF Cardiovascular* | Non-Cardiovascular* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | Discharge | Admission | Discharge | Admission | Discharge | |||||||||

| 1 | Beta-blocker | 333 (60%) | Beta-blocker | 411 (74%) | 1 | Aspirin | 277 (50%) | Aspirin | 349 (63%) | 1 | PPI | 177 (32%) | PPI | 218 (39%) |

| 2 | Loop Diuretic | 264 (47%) | Loop Diuretic | 372 (67%) | 2 | Statin | 275 (49%) | Statin | 306 (55%) | 2 | Electrolyte Supplements | 152 (27%) | Electrolyte Supplements | 213 (38%) |

| 3 | ACE Inhibitor | 186 (33%) | ACE Inhibitor | 233 (42%) | 3 | CCB | 171 (31%) | CCB | 155 (28%) | 3 | Multi-vitamin | 151 (27%) | Multi-vitamin | 152 (27%) |

| 4 | ARB | 108 (19%) | Nitrate | 119 (21%) | 4 | A/C | 134 (24%) | A/C | 175 (27%) | 4 | Thyroid Hormone | 105 (19%) | Adrenergic Bronchodilator | 108 (19%) |

| 5 | Nitrate | 85 (15%) | ARB | 98 (18%) | 5 | P2Y12 Inhibitors | 99 (18%) | P2Y12 Inhibitors |

140 (25%) | 5 | SSRI | 82 (15%) | Thyroid Hormone | 102 (18%) |

Percentages calculated by using total number of patients (N=558)

A/C, Anticoagulation; ACE, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; ARB, Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; CCB, Calcium Channel Blocker; HF, Heart Failure; PPI, Proton Pump Inhibitors; SSRI, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

In the multivariable regression analysis identifying determinants of polypharmacy at discharge, each additional comorbid condition increased the relative risk of taking at least 10 medications at discharge by 13% (RR: 1.13 per comorbid condition, 95% CI [1.08, 1.19]) (Table 4). Interestingly, geriatric conditions including functional impairment (RR: 1.00, 95% CI [0.75, 1.32]), cognitive impairment (RR: 0.85, 95% CI [0.60, 1.18]), history of falls (RR: 1.15, 95% CI [0.88–1.51]) and hypoalbuminemia (RR: 0.92, 95% CI [0.71–1.18]) were not independently associated with polypharmacy.

Table 4.

Determinants of Polypharmacy at Discharge

| Variable | Univariable Model | Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | P-value | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Population Characteristics | ||||

| Age ≥75 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.11) | 0.51 | 0.98 (0.78, 1.24) | 0.88 |

| Female | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) | 0.32 | 1.17 (0.91, 1.50) | 0.23 |

| Black Race | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) | 0.77 | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 0.71 |

| Education (High School or below) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) | 0.60 | 1.03 (0.80, 1.32) | 0.82 |

| Household Income (<$20,000) | 0.92 (0.77, 1.10) | 0.37 | 0.90 (0.67, 1.20) | 0.47 |

| Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction | 1.03 (0.89, 1.21) | 0.67 | 1.00 (0.79, 1.28) | 0.97 |

| Functional Impairment | 1.10 (0.92, 1.30) | 0.31 | 1.00 (0.75, 1.32) | 0.98 |

| Cognitive Impairment | 0.84 (0.67, 1.06) | 0.14 | 0.85 (0.60, 1.18) | 0.33 |

| History of Falls | 1.15 (0.97, 1.36) | 0.11 | 1.15 (0.88, 1.51) | 0.31 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0.99 (0.83, 1.18) | 0.88 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.18) | 0.50 |

| Comorbidity Count | 1.14 (1.10, 1.17) | <0.0001 | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) | <.0001 |

| Intensive Care Unit Stay | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32) | 0.24 | 1.04 (0.78, 1.38) | 0.79 |

| Cardiology Consultation | 1.03 (0.87 1.21) | 0.77 | 0.91 (0.70, 1.18) | 0.48 |

| Length of Stay (per day) | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | <0.0001 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.66 |

| Discharge to home | 0.77 (0.66, 0.91) | 0.002 | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.35 |

| Discharge year (after 2010) | 1.34 (1.16, 1.56) | 0.0001 | 1.26 (0.98, 1.63) | 0.07 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||

| Teaching Hospital | 1.05 (0.91, 1.22) | 0.51 | 0.95 (0.74, 1.23) | 0.70 |

| Small Hospital Size (<200 beds) | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) | 0.06 | 1.25 (0.92, 1.70) | 0.15 |

| Hospital Rating Below Average (<3) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.09) | 0.33 | 0.96 (0.73, 1.25) | 0.74 |

Discussion

During an era when the armamentarium for managing HF continues to expand, the issue of polypharmacy is becoming increasingly relevant for older adults with HF. In this real-world study of medication patterns in older adults hospitalized with HF, there were several important findings. First, we found that almost everyone took at least 5 medications and over half took at least 10 medications, underscoring the high prevalence of polypharmacy in this population. Second, we found that the prevalence of polypharmacy has increased over time, reflecting an urgent need to develop new strategies for managing high medication burden. Finally, we found that the majority of medications prescribed to older adults with HF were non-cardiovascular in nature, supporting the need for processes that can optimize prescribing practices for this subset of medications.

Polypharmacy is broadly defined as the condition of taking a high number of medications. A cutoff of 5 has been arbitrarily chosen to differentiate those with polypharmacy and those without polypharmacy.26, 27 This cutoff is logical for the broader population because there is evidence that the number of adverse events increases beyond 5 medications.14 In our study, we found that the vast majority of older adults with HF took at least 5 medications. This is important because this suggests that older adults with HF are inherently at risk for adverse drug events, and reinforces the idea that polypharmacy should routinely be considered when caring for older adults with HF.28, 29 It also suggests that using a cutoff of 5 medications to risk-stratify older adults with HF for the potential harms of a high medication burden may not be optimal in this population. Given our observation that about 50% of older adults with HF take at least 10 medications coupled with the known link between this extreme version of polypharmacy30–32 and an incrementally increased risk of adverse events,12, 14, 33 it may be reasonable to use a cutoff of 10 medications to define polypharmacy in older adults with HF, which can identify individuals at highest risk for adverse events related to high medication burden.

Using a cutoff of 10 medications, we found that the prevalence of polypharmacy in this population at both hospital admission and hospital discharge has risen significantly between the early period of the REGARDS study (2003–2006) and later period (2011–2014). While this could represent better guideline-concordant therapy for the many medical conditions that older adults contend with (comorbidity burden was the only factor in our analysis that was independently associated with polypharmacy), this is also potentially concerning because a high medication burden contributes to an increased risk for adverse drug reactions,14 and is associated with a number of adverse outcomes including falls,7–9 disability,10–12 and hospitalizations.13, 14 High medication burden is also associated with treatment burden,34, 35 reduced medication adherence,36 and low quality of life.37 Issues like therapeutic competition, defined as the clinical situation where a medication that treats one condition is harmful for another condition,38 and competing health priorities39 further complicate optimizing medication regimens in older adults with HF, and support the need to develop evidence-based patient-centered strategies for managing patients with polypharmacy and, relatedly, multiple chronic conditions. Tinetti et al recently outlined a framework and formal process that can be used when caring for older adults with multiple chronic conditions (and polypharmacy) called Patient Priorities Care40 which involves identifying, communicating, and providing care consistent with patients’ health priorities. This approach has shown some promise for addressing challenges in decision-making faced by older adults with multiple chronic conditions (and polypharmacy) when competing priorities are present. Whether this model can be applied to older adults with HF is unknown and warrants further investigation.

Irrespective of the total medication count, we found that non-cardiovascular medications comprised the majority of medications taken by older adults with HF. This directly reflects the significant comorbidity burden that most older adults with HF contend with; approximately 90% of older adults with HF have at least 3 other medical conditions, and over 60% have at least 5 other medical conditions.4 It may be hard to argue that the risks of polypharmacy outweigh the benefits of guideline-based care for conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and/or diabetes which frequently require multiple pharmacologic agents. Accordingly, continuing or starting medications that directly treat these conditions may be reasonable, and moreover support the development of medications that can concurrently treat multiple conditions such as SGLT-2 inhibitors which can treat both diabetes and HF.1, 41, 42 On the other hand, the value of starting and/or continuing proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and multivitamins, which we found represented two of the top three most common non-cardiovascular medications taken at admission and discharge, is debatable. Indeed, PPIs have been described as one of the most over-prescribed medications for older adults;43 and the data supporting the use of multivitamins are limited.44 Thus, to address polypharmacy in this population, it may be reasonable to consider eliminating these agents in the absence of compelling indications. In addition to reducing medication burden, eliminating agents with limited benefit may have important implications on the use of GDMT for HF, which has persistently been underutilized in the United States and requires novel strategies to improve its uptake.45 Indeed, polypharmacy has been described as an important physician-reported barrier to initiating GDMT,46 is associated with underprescribing,47 and is an important predictor of reduced adherence.36 Whether eliminating non-cardiovascular medications with limited benefit can improve prescribing rates of GDMT and/or improve patient adherence by reducing medication burden is unknown and warrants further investigation.

We also found that electrolyte supplements represented one of the top 3 most common non-cardiovascular medications at both admission and discharge. Electrolyte supplements like potassium are often used to treat hypokalemia, a well-known effect of diuretic therapy that is associated with adverse outcomes.48 This observation highlights yet another potential opportunity to improve GDMT. For individuals requiring potassium supplements, initiation of a mineralocorticoid antagonist, which is considered a part of GDMT for HF, could provide an alternative strategy to combat hypokalemia. Consistent with prior studies, the use of mineralocorticoid antagonists in our study was low,49 despite their potential to improve mortality in HFrEF and reduce hospitalizations (and possibly mortality) in HFpEF.2, 3 Future study is thus warranted to explore whether increased focus on managing non-cardiovascular medications (discontinuing potassium supplementation) can improve rates of GDMT and thereby improve outcomes in HF.

There are several strengths to this study. REGARDS is a national sample that includes participants and hospitals from all regions of the contiguous 48 United States and thus has a high degree of generalizability to the United States population.50 Another strength was the availability of chart-level medical record data for each hospitalization which allowed detailed data collection of medications and comorbid conditions. There are also some important limitations to our study. This study was observational in nature and thus precluded establishing a causal relationship between variables. This study examined older adults with Medicare, and may not be generalizable to younger individuals and those without Medicare. While medication data were obtained at the time of the hospitalization, some participant characteristics including geriatric conditions were obtained at the time of study enrollment which are subject to change by the time of their hospitalization. The number of medications did not account for multiple pharmacologically-active ingredients in a single pill (e.g. combination pills), and did not account for pill burden (multiple pills of the same medication). We also did not account for dosages or the schedule for medications. All of these aspects can contribute further to medication burden and regimen complexity, and thus warrant future investigation. Finally, this study was conducted prior to the approval of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors, ivabradine, and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Consequently, the prevalence of polypharmacy and the contribution of HF medications to polypharmacy are likely even more substantial today than shown in this study.

In conclusion, our study showed that polypharmacy (defined as at least 10 medications) is common among hospitalized HF patients and its prevalence is rising over time, supporting the use of ≥10 medications as a marker for high risk in this population. Our study also showed that the majority of medications taken by older adults with HF are non-cardiovascular medications, some of which may have limited benefit. Taken together, our findings support the need to develop strategies to mitigate the negative effects of polypharmacy among older adults with HF, potentially starting with formalized processes that can improve prescribing practices for non-cardiovascular medications.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Implications.

What is new?

Polypharmacy, defined as taking ≥10 medications here, is common in older patients hospitalized for heart failure.

The prevalence of polypharmacy increases after a hospitalization for heart failure; and has increased between 2003 and 2014.

The majority of medications prescribed to older adults with heart failure are non-cardiovascular medications.

What are the Clinical Implications?

A cutoff of 10 medications to identify polypharmacy may be optimal for identifying older adults with heart failure at greatest risk for harms related to high medication burden

Strategies are needed to mitigate the potential negative effects of polypharmacy in older adults with heart failure.

Reconciliation and optimization of non-cardiovascular medications could help reduce medication burden, and indirectly impact the use of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research project is supported by cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIA. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at: https://www.uab.edu/soph/regardsstudy/

Sources of Funding:

This research project was additionally supported by R01HL8077 (PI: Safford) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and R03AG056446 (PI: Goyal) from the National Institute on Aging. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Institute on Aging had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosures:

Dr. Goyal is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant R03AG056446, an NIA loan repayment award, and American Heart Association grant 18IPA34170185. Dr. Levitan has received research support from Amgen and has served on Amgen advisory boards and as a consultant for a research project funded by Novartis. Dr. Safford has received research support from Amgen.

Footnotes

References:

- 1.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Belohlavek J, Bohm M, Chiang CE, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukat A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O’Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjostrand M, Langkilde AM, Committees D-HT and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ and Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW and Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/Chartbook_Charts.html Accessed February 18, 2019.

- 5.Maher RL, Hanlon J and Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C and Mandl KD. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeland KN, Thompson AN, Zhao Y, Leal JE, Mauldin PD and Moran WP. Medication use and associated risk of falling in a geriatric outpatient population. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima T, Akishita M, Nakamura T, Nomura K, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Eto M and Ouchi Y. Polypharmacy as a risk for fall occurrence in geriatric outpatients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziere G, Dieleman JP, Hofman A, Pols HA, van der Cammen TJ and Stricker BH. Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:218–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magaziner J and Cadigan DA. Community resources and mental health of older women living alone. J Aging Health. 1989;1:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crentsil V, Ricks MO, Xue QL and Fried LP. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of community-dwelling, disabled older women: Factors associated with medication use. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R and Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A and Tsutani K. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:146–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, Aspinall SL, Handler SM, Ruby CM and Pugh MJ. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangoni AA and Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai X, Hummel SL, Salazar JB, Taffet GE, Zieman S and Schwartz JB. Cardiovascular physiology in the older adults. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, Sloane RJ, Lindblad CI, Ruby CM and Schmader KE. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson EB, Kukull WA, Buchner D and Reifler BV. Adverse drug reactions associated with global cognitive impairment in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parameswaran Nair N, Chalmers L, Peterson GM, Bereznicki BJ, Castelino RL and Bereznicki LR. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions -the need for a prediction tool. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS and Howard G. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal P, Kneifati-Hayek J, Archambault A, Mehta K, Levitan EB, Chen L, Diaz I, Hollenberg J, Hanlon JT, Lachs MS, Maurer MS and Safford MM. Prescribing Patterns of Heart Failure-Exacerbating Medications Following a Heart Failure Hospitalization. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ and Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, Maurer MS, Green P, Allen LA, Popma JJ, Ferrucci L and Forman DE. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler J, Anker SD and Packer M. Redefining Heart Failure With a Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Documentation and Codebook, Drug Information. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHs/nhanes/nhanes3/2A/rxq_drug.pdf Updated June 2009. Accessed January 27, 2017

- 26.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P and Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:2867–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rich MW. Pharmacotherapy of heart failure in the elderly: adverse events. Heart Fail Rev. 2012;17:589–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorodeski EZ, Goyal P, Hummel SL, Krishnaswami A, Goodlin SJ, Hart LL, Forman DE, Wenger NK, Kirkpatrick JN, Alexander KP and Geriatric Cardiology Section Leadership Council ACoC. Domain Management Approach to Heart Failure in the Geriatric Patient: Present and Future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1921–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goyal P, Gorodeski EZ, Flint KM, Goldwater DS, Dodson JA, Afilalo J, Maurer MS, Rich MW, Alexander KP and Hummel SL. Perspectives on Implementing a Multidomain Approach to Caring for Older Adults With Heart Failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2593–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Runganga M, Peel NM and Hubbard RE. Multiple medication use in older patients in post-acute transitional care: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1453–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishtala PS and Salahudeen MS. Temporal Trends in Polypharmacy and Hyperpolypharmacy in Older New Zealanders over a 9-Year Period: 2005–2013. Gerontology. 2015;61:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennel PJ, Kneifati-Hayek J, Bryan J, Banerjee S, Sobol I, Lachs MS, Safford MM and Goyal P. Prevalence and determinants of Hyperpolypharmacy in adults with heart failure: an observational study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez C, Vega-Quiroga S, Bermejo-Pareja F, Medrano MJ, Louis ED and Benito-Leon J. Polypharmacy in the Elderly: A Marker of Increased Risk of Mortality in a Population-Based Prospective Study (NEDICES). Gerontology. 2015;61:301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L and Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eton DT, Ramalho de Oliveira D, Egginton JS, Ridgeway JL, Odell L, May CR and Montori VM. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapman RH, Benner JS, Petrilla AA, Tierce JC, Collins SR, Battleman DS and Schwartz JS. Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montiel-Luque A, Nunez-Montenegro AJ, Martin-Aurioles E, Canca-Sanchez JC, Toro-Toro MC, Gonzalez-Correa JA and Polipresact Research G. Medication-related factors associated with health-related quality of life in patients older than 65 years with polypharmacy. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorgunpai SJ, Grammas M, Lee DS, McAvay G, Charpentier P and Tinetti ME. Potential therapeutic competition in community-living older adults in the U.S.: use of medications that may adversely affect a coexisting condition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV and Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, Costello DM, Esterson J, Geda M, Rosen J, Hernandez-Bigos K, Smith CD, Ouellet GM, Kang G, Lee Y and Blaum C. Association of Patient Priorities-Aligned Decision-Making With Patient Outcomes and Ambulatory Health Care Burden Among Older Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam CSP, Chandramouli C, Ahooja V and Verma S. SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure: Current Management, Unmet Needs, and Therapeutic Prospects. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goyal P, Kneifati-Hayek J, Archambault A, Mehta K, Levitan EB, Chen L, Diaz I, Hollenberg J, Hanlon JT, Lachs MS, Maurer MS and Safford MM. Reply: Toward Improved Understanding of Potential Harm in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:247–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schepisi R, Fusco S, Sganga F, Falcone B, Vetrano DL, Abbatecola A, Corica F, Maggio M, Ruggiero C, Fabbietti P, Corsonello A, Onder G and Lattanzio F. Inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors in elderly patients discharged from acute care hospitals. Journal of Nutrition Health & Aging. 2016;20:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J, Choi J, Kwon SY, McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, Guallar E, Zhao D and Michos ED. Association of Multivitamin and Mineral Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Duffy CI, Hill CL, McCague K, Mi X, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Thomas L, Williams FB, Hernandez AF and Fonarow GC. Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: The CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levitan EB, Van Dyke MK, Loop MS, O’Beirne R and Safford MM. Barriers to Beta-Blocker Use and Up-Titration Among Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Cardiovasc Drug Ther. 2017;31:559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuijpers MA, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, Jansen PA and Group OS. Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:130–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savarese G, Xu H, Trevisan M, Dahlstrom U, Rossignol P, Pitt B, Lund LH and Carrero JJ. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcome Associations of Dyskalemia in Heart Failure With Preserved, Mid-Range, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Vaduganathan M, Albert NM, Duffy CI, Hill CL, McCague K, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Thomas L, Williams FB, Hernandez AF and Butler J. Titration of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2365–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie F, Colantonio LD, Curtis JR, Safford MM, Levitan EB, Howard G and Muntner P. Linkage of a Population-Based Cohort With Primary Data Collection to Medicare Claims: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:532–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.