Abstract

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has arrived and begun to change the landscape of clinical oncology, including for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Specifically, drugs targeting the programmed death 1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen pathways have demonstrated remarkable responses for patients in clinical trials. In this article, we review the most recent available data for immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with renal cell carcinoma. We discuss potential strategies for rational combination therapies in these patients, some of which are currently being studied, and address important future considerations for use of these novel agents in the years to come.

Keywords: : cytokine, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4, immune checkpoint blockade, programmed death 1, renal cell carcinoma, immunotherapy, VEGF

In 2015 alone, about 61,560 new cases of kidney cancer will be diagnosed in the USA, with an estimated 14,080 kidney-cancer related deaths [1]. These numbers largely reflect cases of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the most common primary cancer of the kidney. While many tumors are found early and can be cured surgically, approximately 20% present with de novo metastatic disease and about a third of patients diagnosed with localized RCC will ultimately develop metastases [2,3]. The management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has undergone substantial changes in the past decade, with novel systemic strategies fundamentally altering the approach to this disease.

Prior to 2005, treatment options for mRCC were limited, but evidence existed that RCC might be particularly sensitive to manipulations of the immune system. Everson and Cole were among the first to describe spontaneous remissions in patients with mRCC when they reported cases of tumors exhibiting shrinkage without any substantial treatment in the 1960s [4,5]. IL-2, a cytokine important for regulating circulating lymphocytes, was found to result in durable complete remissions in about 5–7% of clear cell mRCC patients, leading to the approval of aldesleukin by the US FDA for treatment of mRCC in 1992. Unfortunately, most patients did not respond and treatment was extremely toxic, limiting use to experienced, high volume centers and reserved for patients with a good performance status and acceptable comorbid conditions [6,7]. A second cytokine, IFN-α, was also used for this disease, with a modest response rate (RR) of approximately 15% as a single agent, but overall the initial era of immunotherapy for mRCC was characterized by low rates of disease control and high rates of toxicity.

Between 2005 and 2012, seven new drugs garnered approval for the treatment of mRCC. This ushered in the VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) era, reflecting an enhanced understanding of the biology of mRCC. With the exception of bevacizumab, these new agents are oral, small molecule TKIs targeting the VEGF. In addition, two drugs targeting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways to disrupt angiogenesis and intrinsic cell proliferation signals were also approved [8]. By interfering with systems essential for tumor growth and metastasis, combinations of these drugs used in sequence improved the overall survival of mRCC to >28 months [9]. Unfortunately, while initial RRs are encouraging, most patients ultimately develop resistance and few have durable disease control.

Consequently, the impetus to harness the immune system to combat this disease remained strong. A meta-analysis evaluating tumor response in patients receiving placebo in randomized trials revealed high rates of spontaneous remissions in RCC, validating this approach [10]. More recently, new agents known as immune checkpoint inhibitors that unlock the antitumor abilities of the immune system have entered the clinic with promising durable responses in patients across a variety of tumor types, including RCC. The term immune checkpoint refers to the idea that certain pathways inherent to the immune system regulate a sustained immune response and can be stimulated to shut down immune activation. This is in place to protect the host from overzealous immune activity that can result in harm after an insult (be it infectious, malignant or other) is recognized and dealt with. Many tumors have evolved the ability to exploit these pathways to evade immune recognition and maintain undisturbed growth and proliferation. Pharmacologic inhibition of these pathways can restore antitumor control in some patients. Two checkpoint pathways have been successfully targeted in Phase III oncology trials and have led to the approval of new drugs. The programmed death 1 (PD-1) pathway functions peripherally in the tumor microenvironment, while the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein (CTLA-4) pathway controls early T-cell activation [11]. In this review, we will discuss the agents being used to modify these pathways in the context of RCC, as well as other targets, combinations and strategies being explored to enhance efficacy and advance the treatment paradigm for RCC, commencing a new era of immunotherapy. We will focus on clear cell RCC (ccRCC), the predominant histologic subtype of this disease.

Programmed death 1 pathway blockade

PD-1 is an immunoinhibitory receptor that belongs to the CD28/CTLA-4 family and is inducibly expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells and monocytes within 24 hours from their immunological activation [12]. Usually, activated T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, dendritic cells (DCs) and monocytes express PD-1 in order to restrict autoimmunity during inflammatory states such as infections. However, tumors have evolved the ability to express the main PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) to exploit this mechanism, thus downregulating the antitumor T-cell response [13]. PD-L1 is not expressed on normal kidney tissues, but is expressed in a significant proportion of both primary and metastatic RCC specimens. [14] Therefore, inhibiting this pathway with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting either PD-1 or PD-L1 can reenergize exhausted T-cells downregulated by tumor-directed PD-L1 expression, culminating in innate antitumor detection and coordinated tumor cell death.

Releasing this restraint on the immune system is not without consequences. The PD-1 checkpoint protects the immune system from overactivation and precipitating autoimmunity. Thus, side effects from checkpoint blockade have been characterized by organ-specific inflammatory reactions such as dermatitis and colitis, clinically and pathologically mimicking site-specific autoimmune diseases, and termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Serious and unusual toxicities rarely seen with any other agents, such as endocrinopathies and autoimmune pneumonitis, have been described [15]. These toxicities have proven to be a class effect, with severe adverse events (AEs) occurring at a relatively consistent 10–20% rate across clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors regardless of tumor type. In the landmark Phase III trial evaluating the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab in patients with previously treated mRCC, grade 3–4 AEs occurred in 19% of patients, but not all of these would be considered irAEs [16]. None of the most common irAEs, such as diarrhea/colitis, occurred as grade 3 or higher in >1% of patients. Nearly all acute autoimmune events have been reversible with prompt initiation of corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive agents, and chronic endocrine deficiencies can be managed effectively with replacement therapy [15].

Immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy in mRCC

PD-1 blockade

The first immune checkpoint inhibitor to gain FDA approval for patients with mRCC was nivolumab (BMS-936558), a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) targeting PD-1. Nivolumab has also been FDA approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma and advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [17]. Preclinical work by Thompson et al. evaluated PD-L1 expression in ccRCC. In a series of 306 resected tumors, PD-L1 was expressed by 23.9% of the tumors analyzed. Patients whose tumors expressed PD-L1 had a significantly higher rate of metastatic cancer progression as well as death from RCC [18]. In 2012 results of a Phase I trial with nivolumab were first reported. The trial included patients with various tumor types, including 33 patients with mRCC who had failed conventional agents such as TKIs. There was a 27% objective response rate (ORR) in these patients [19]. Since then several trials studying checkpoint inhibitors specifically in RCC have been reported (Table 1). Notably, the Phase III CheckMate-025 trial demonstrated superior median overall survival (mOS) with nivolumab (n = 406) in patients with advanced RCC who progressed on antiangiogenic therapy compared with patients receiving everolimus (n = 397; 25 vs 19.6 months, respectively; HR: 0.73; p = 0.002) [16]. Nivolumab also showed a trend toward improved progression-free survival (PFS; HR: 0.88; p = 0.11) and fewer patients experienced grade ≥ 3 adverse events (19 vs 37%, respectively). Based on this trial, nivolumab earned approval by the FDA as a second-line therapy following antiangiogenic treatment failure in patients with advanced RCC [20].

Table 1. . Clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma with available efficacy results.

| Author (year) | Drug(s) | Phase | Setting and trial details | Total N treated (per arm) | Primary end point | Median OS | Median PFS | ORR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motzer, (2014) [66] | Nivolumab | II | Metastatic, second-line or beyond Three-arm randomization amongst three doses of nivolumab (0.3, 2 or 10 mg/kg) |

0.3 mg/kg arm: 60 2 mg/kg arm: 54 10 mg/kg arm: 54 |

Comparison of PFS across the three dose arms to assess a dose–response relationship | 18.2 mo 25.5 mo 24.7 mo |

2.7 mo 4.0 mo 4.2 mo |

20 22 20 |

| Motzer, (2015, Checkmate-025) [16] | Nivolumab vs Everolimus | III | Second- or third-line metastatic Two-arm, 1:1 randomization vs everolimus |

Nivo: 410 Everolimus: 411 |

Overall survival | Nivo: 25 mo Eve: 19.6 mo |

Nivo: 4.6 mo Eve: 4.4 mo |

Nivo: 25 Eve: 5 |

| Choueiri, (2015) [21] | Nivolumab | I | Three-arm, randomization amongst three doses (0.3, 2 or 10 mg/kg) | 91 (total across 3 arms) | Immunomodulatory activity | 0.3 mg/kg: 16.4 mo 2 mg/kg: NR 10 mg/kg: NR |

N/A | N/A |

| McDermott, (2016) [26] | Atezolizumab | I | Any line, metastatic | 63 (ccRCC cohort) | Safety and toxicity | 28.9 | 5.6 | 15 |

| Yang, (2007) [32] | Ipilimumab | II | Any line metastatic; 2 arms at either 3 mg/kg or 3 mg once followed by 1 mg/kg | 3→1 mg/kg: 21 3 mg/kg: 40 |

Response rate | N/A | N/A | Nivo: 4.7 Eve: 12.5 |

Although nivolumab displayed a respectable ORR of 25% in the Checkmate-025 trial, the majority of patients did not respond. There are currently no validated biomarkers for selection of patients who may benefit from nivolumab therapy, but secondary analyses in Checkmate-025 demonstrated that PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was prognostic but not predictive of benefit from checkpoint inhibition. Similarly, an exploratory Phase I study in patients with mRCC receiving three different doses of nivolumab analyzed potential biomarkers of response using four distinct methods: PD-L1 expression, soluble factors from peripheral blood, gene expression profiling and T-cell receptor sequencing [21]. As reported at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, median OS appeared longer in PD-L1 positive patients, but data were not yet mature and PD-L1 negative patients clearly showed responses. While this study suggested PD-L1 expression level may be associated with the probability of prolonged survival, it did not uncover a definitive predictive biomarker. Final efficacy and survival data from this study is expected in early 2016. On the other hand, a study by Sekar et al. showed no correlation between PD-1 expression and survival in patients with RCC [22].

Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) is a humanized IgG4 PD-1-blocking mAb that has received FDA approval for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma and advanced NSCLC after progression on platinum-based chemotherapy [23]. Pembrolizumab was investigated in a Phase I trial enrolling patients with advanced solid tumors, however no patients with mRCC were included [24]. Despite this, and given the robust activity of nivolumab in this disease, pembrolizumab is currently being studied further as a monotherapy in RCC in the neoadjuvant setting (Clinical Trial: NCT02212730) but has not been explored as a single agent in the metastatic setting. As discussed later in this review, pembrolizumab is being studied extensively in combination with other agents in RCC. Table 2 includes ongoing clinical trials of single agents for RCC.

Table 2. . Ongoing clinical trials with single agent checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma.

| Trial Number | Drug | Setting | Arms | Phase | Expected Completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02595918 | Nivolumab | Neoadjuvant, nonmetastatic | Single-arm | Pilot | September 2017 |

| NCT02446860 (ADAPTeR) | Nivolumab | Perioperative therapy, first-line metastatic | Single-arm | II | November 2016 |

| NCT02596035 (Checkmate 347) | Nivolumab | Second- to fourth-line, metastatic | Single-arm postmarketing | IIIB/IV | October 2017 |

| NCT02575222 | Nivolumab | Neoadjuvant, nonmetastatic | Single-arm | I | December 2017 |

| NCT02212730 | Pembrolizumab | First-line neoadjuvant Prior to cytoreductive nephrectomy |

Two arms, randomized to pembro or no presurgical treatment | I | February 2017 |

| NCT02599779 | Pembrolizumab | Second-line or above, metastatic | Pembrolizumab + SBRT given on progression vs SBRT with concurrent Pembro | II | January 2019 |

| NCT02626130 | Tremelimumab | First- or second-line, metastatic | Tremelimumab +/- cryoablation | Pilot | February 2021 |

| NCT01772004 | Avelumab | First-line metastatic | Single-arm dose escalation with RCC expansion cohort | I | April 2017 |

PD-L1 blockade

Given the direct interaction of PD-1 on immune effector cells with PD-L1 on tumor cells, both have proven to be viable targets for pharmacoinhibition. A Phase I trial of the PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-936559 was conducted in patients with varied tumor types, including mRCC, who had failed conventional agents. Seventeen patients with mRCC were enrolled. Objective response was seen in two (12%) and stable disease was seen in seven (41%) patients over 24 weeks [25]. Though this agent is not currently being studied further in mRCC, it demonstrated the potential of PD-L1 inhibition in RCC.

Atezolizumab (atezolizumab, MPDL3280A) is a humanized mAb targeting PD-L1, and results of an expansion cohort of patients with mRCC from its initial Phase I trial have been reported [26]. This trial predominantly enrolled previously treated (57% ≥ 2 prior lines) patients, and also included both clear cell and non-clear cell RCC (nccRCC). Amongst all ccRCC patients assessed for survival (n = 63), the mOS was 28.9 months and the mPFS was 5.6 months. The ORR (n = 62 for this outcome) was 15% amongst ccRCC patients, with no responses by RECIST in the patients with nccRCC (n = 7). Biomarker analysis found no clear association to PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and response. Grade 3 treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 17% of patients, which was comparable to similar studies of other agents.

At least two other PD-L1 inhibitors have been tested in Phase I studies of patients with advanced solid tumors and have included patients with mRCC, however, efficacy results in mRCC patients have not yet been made available. Recruitment is ongoing for a Phase I trial of the selective human IgG1 anti-PD-L1 mAb durvalumab (MEDI4736, NCT01693562). In this trial, patients with numerous tumor types, including mRCC, are being enrolled. This agent has reported single-agent activity in other tumors, but further studies specific to RCC are noted below with discussion of combination trials. Avelumab (MSB0010718C), a fully human mAb targeting PD-L1, had results of safety and pharmacokinetic data reported at the 2015 American Society of Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting [27,28]. Grade ≥3 AEs were reported in 12.3% of patients, with irAEs reported in 11.7%, both comparable to agents in other trials [28]. Further study of this agent in mRCC is currently limited to combination approaches.

Importantly, PD-1 actually has two main ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2 [29]. PD-L1 has been more extensively studied and appears to be more diffusely expressed in the immune environment, thus it has been extensively targeted in clinical trials. PD-L1 also binds CD-80 on activated immune cells to impart inhibitory signals, though the clinical relevance of this interaction remains unknown. PD-L2 similarly engages other targets with unclear clinical significance. As drugs inhibiting these targets on both sides of the pathway are tested, these important escape mechanisms need to be considered as sources of differential response kinetics, toxicities and resistance pathways.

CTLA-4 blockade

Another prominent immune checkpoint that is expressed on activated T-cells and has been targeted successfully with antineoplastic agents is CTLA-4. This type I transmembrane protein is upregulated on T-cells and functions largely in the lymphatic system as a physiologic safeguard against over activation of the immune system by outcompeting the T-cell co-stimulatory receptor CD-28 for its ligands CD80 and CD86 to dampen the overall immune response. However, like with PD-1/PD-L1, many tumor types have developed the ability to exploit this system to circumvent immunosurveillance and avoid a robust antitumor response [30].

Two CTLA-4 directed monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been assessed in clinical trials. Ipilimumab was the first immune checkpoint inhibitor made available for clinical use when it received FDA-approval for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma in 2011 based on demonstration of a survival benefit in a Phase III trial [31]. It has continued to be studied as a viable single agent in other cancer types, as well as in various combinations which will be covered later in this review. Published data are available from a Phase II trial that investigated two separate dosing schedules of ipilimumab as a single agent in patients with mRCC [32]. This study yielded an ORR of 12.5% in the higher dosed cohort, with six durable PRs reported across the dosing schedules. In a separate analysis of this study focusing on patients who developed enterocolitis as an irAE, the ORR in the mRCC cohort was 35% for patients who developed enterocolitis, compared with 2% in those who did not [33].

Tremelimumab is the other CTLA-4 inhibitor that has been tested in clinical trials, but it has not gained FDA-approval for commercial use, likely due to multiple factors engrained in the design of the definitive Phase III trial in melanoma patients (dosing schedule, criteria used for tumor assessments, patient selection, subsequent treatment options) which failed to meet its primary end point [34,35]. For patients with mRCC, tremelimumab has been evaluated in a Phase I trial in combination with the oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sunitinib [36]. The study enrolled 28 patients, but it was stopped due to excess toxicity (one death and four patients with renal failure) and this combination was aborted. Of 21 patients evaluable for response, 43% achieved a PR.

Although the data in mRCC is limited, it is clear from the melanoma population that CTLA-4 blockade yields a lower ORR and higher toxicity as compared with PD-1 pathway blockade. Thus, with nivolumab now available to patients, there is little experimental appetite for single agent CTLA-4 inhibitor studies to continue in mRCC. However, combinations of CTLA-4 inhibitors with PD-1 pathway blockers are leading the way in the nascent combination stage of immunotherapy for RCC.

Immunotherapy combinations

The capacity for achieving durable responses with checkpoint inhibitors is what drives much of the excitement surrounding these agents. However, the ORR of the nivolumab arm in the Phase III Checkmate 025 trial was a modest 25% [16]. Although ORR is an underestimation of the proportion of patients benefiting from these agents since it cannot account for pseudoprogression, a substantial proportion of mRCC patients do not attain a significant benefit from PD-1 inhibition. Therefore, strategies to increase the number of patients who benefit from checkpoint inhibition are being explored and rational combinations are viewed as the most viable path to success.

Dual checkpoint blockade

Again extrapolating from studies in the metastatic melanoma population, combined PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade set the bar for what is possible with immunotherapy. In a three arm, double-blind, Phase III trial, patients with metastatic melanoma were randomized to receive ipilimumab alone, nivolumab alone, or the combination [37]. The trial met its co-primary end point of improving PFS, which was 11.5 months in the combination arm, compared with 6.9 and 2.9 months, respectively, in the nivolumab and ipilimumab arms (p < 0.001). The ORR in the combination arm was an impressive 57.6%. Unfortunately, with the improved efficacy comes increased toxicity. The incidence of grade 3–4 adverse events was 55.0% in the combination arm, while in the single agent arms grade 3–4 events occurred in 16.3% (nivolumab) and 27.3% (ipilimumab) of patients. More than a third of patients discontinued combination therapy due to toxicity. Notably, responses were noted to endure after cessation of therapy. Accordingly, this combination has gained FDA-approval for patients with metastatic melanoma and is being evaluated in patients with other immunogenic tumors, including RCC.

Checkmate 016 is a Phase I study evaluating various combination regimens in patients with mRCC, including three dosing combinations of ipilimumab/nivolumab (arm I1: nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg; arm I3: nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg; arm IN-3: nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg). Both treatment naive and previously treated (cytokine therapy only) patients were eligible for enrollment. Updated results from the two arms that progressed to the expansion cohorts (arm IN-3 stopped for excess toxicity) were reported at the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting [38]. With 47 patients evaluable in each arm, the ORR ranged from 38–43%, with another 40% achieving stable disease (SD) in each arm, thus resulting in a disease control rate (complete and partial responses plus stable disease) approaching 80%. Grade 3–4 toxicities were comparable to those reported in the melanoma study, with 16% of patients discontinuing therapy. The rate of toxicity was highest in the arms with higher ipilimumab dosing. Based on these results, an open-label, randomized, Phase III trial (NCT02231749, Checkmate 214) comparing the ipilimumab/nivolumab combination to sunitinib for patients with previously untreated mRCC has completed accrual.

Combined checkpoint blockade is not restricted to the ipilimumab/nivolumab combination. Several combinations of agents targeting PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 are being studied in RCC (see Table 3). Pembrolizumab is being evaluated in combination with ipilimumab or the cytokine pegylated IFN-α in a Phase I/II study in patients with mRCC and melanoma (NCT02089685). The dose escalation portion will establish recommended Phase II doses (RP2D) of pembrolizumab with each combination, followed by randomization to each combination or pembrolizumab alone. The PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab (MEDI4736) is being combined with tremelimumab in a Phase I study of patients with select, advanced solid tumors, including RCC (NCT01975831). Durvalumab is also being studied in combination with MEDI0680 (AMP-514), a PD-1-targeted mAb that also triggers internalization of PD-1 by contacted T-cells, in a Phase I study including all solid tumors (NCT02118337) [39].

Table 3. . Ongoing clinical trials with immune checkpoint combination therapies in renal cell carcinoma.

| Trial Number | Drug combination | Setting | Arms | Phase | Expected Completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02231749 | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | 1st line metastatic | 2 arms randomized vs Sunitinib | III | May 2019 |

| NCT01472081 | Nivolumab + (Ipilimumab or Sunitinib or Pazopanib) | 1st or 2nd line metastatic | 5 (Nivolumab with each combo and various dose combinations with ipi) | I | February 2016 |

| NCT02210117 | Nivolumab + Bevacizumab or Ipilimumab | Any line metastatic, perioperative cytoreductive nephrectomy treatment | 3 (Nivolumab alone and with each combo) | II | November 2018 |

| NCT02614456 | Nivolumab + Interferon-gamma | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | Single arm dose escalation with expansion RCC cohort | I | December 2017 |

| NCT01968109 | Nivolumab + BMS-986016 (anti-LAG-3) | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond (for RCC) | Single arm dose escalation | I | May 2018 |

| NCT02089685 | Pembrolizumab + Ipilimumab or Pegylated Interferon-alfa | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | 3 (Pembrolizumab alone or with each combo) | I/II | April 2017 |

| NCT02014636 | Pembrolizumab + Pazopanib | Metastatic 1st line | Single arm combo in Phase I; 3 arm randomization to each combo or single agent pazopanib Phase II | I/II | October 2018 |

| NCT02348008 | Pembrolizumab + Bevacizumab | Phase I: Metastatic 2nd line and beyond Phase II: Metastatic 1st Line |

Phase I dose escalation of combo, followed by Phase II expansion at MTD | I/II | March 2017 |

| NCT02133742 | Pembrolizumab + Axitinib | Metastatic 1st line | Single arm dose escalation | I | March 2017 |

| NCT02619253 | Pembrolizumab + Vorinostat | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | Phase I dose escalation of combo, followed by Phase II expansion at MTD | I/II | March 2018 |

| NCT02178722 | Pembrolizumab + INCB024360 (IDO1 inhibitor) | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | Phase I dose escalation of combo | I/II | May 2017 |

| NCT01975831 | Durvalumab + Tremelimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | Phase I dose escalation of combo | I | October 2017 |

| NCT02420821 | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Metastatic 1st line | Randomized versus sunitinib | III | June 2020 |

| NCT02174172 | Atezolizumab + IFN-alfa (Ipilimumab for NSCLC pts) | Metastatic 2nd line and beyond | Nonrandomized 2 arm trial combining atezolizumab with each combo | I | February 2018 |

| NCT02493751 | Avelumab + Axitinib | Metastatic 1st line | Phase I dose escalation of combo with dose expansion | I | March 2018 |

| NCT02684006 | Avelumab + Axitinib | Metastatic 1st line | Randomized versus sunitinib | III | February 2018 |

| NCT01441765 | Pidilizumab + DC-RCC fusion vaccine | Metastatic any line | Nonrandomized 2 arm trial with pidilizumab alone or the combo | II | Completed accrual |

Early studies have also begun exploring the inhibition of novel checkpoints in addition to the PD-1 pathway. One example of this is LAG-3, which is an immune checkpoint found on multiple immune cells, including CD8+ T-cells, and binds major histocompatibility complex class II to suppress T-cell proliferation and function [40]. IMP321 is a soluble LAG-3 fusion protein that was tested in a Phase I dose escalation study in patients with mRCC [41]. 21 patients were treated at varying doses, and the drug was well tolerated with grade 1 local reactions being the only clinical side effects and reduced tumor growth noted at higher doses. A Phase I study of the anti-LAG-3 drug BMS-986016 with or without nivolumab in patients with select solid tumors, including RCC, is currently recruiting patients (NCT01968109). Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) is not a true immune checkpoint, but is an intracellular enzyme that serves as the rate limiting step in the kynurenine/tryptophan degradation pathway and has been shown to play an important role in immune tolerance in the tumor microenvironment of many cancers [42,43]. Epacadostat (INCB024360) is an IDO1 inhibitor that is being studied in a Phase I/II study in combination with pembrolizumab in multiple advanced solid tumors (NCT0217822), including mRCC. Preliminary results reported have shown the combination to be well tolerated. Of 19 patients evaluable for response, 15 were reported to have reductions in tumor burden, including an ORR of 40% in the mRCC subset with a disease control rate of 80% [44].

Combinations of checkpoint inhibitors with VEGF receptor inhibitors

The standard of care for first-line treatment of mRCC for the better part of the past decade has been with oral TKIs that target the VEGFR, as well as other pathways, to inhibit angiogenesis and suppress tumor growth [9,45,46]. These drugs achieve about a 25–30% response rate in treatment naive patients, with a disease control rate >50%, but rarely result in durable responses, with median PFS ranging from 8.5–11 months [9,45,46]. The TKIs have a manageable and predictable safety profile, with little overlap with the checkpoint inhibitors, thus interest existed to combine approaches. The Checkmate 016 trial, in addition to combining nivolumab with ipilimumab as noted above, also included arms combining nivolumab with a TKI (either sunitinib or pazopanib) in both previously treated and treatment-naive patients. Data for these cohorts was most recently presented at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting [47]. In 20 previously treated patients in the nivolumab/pazopanib group, the ORR was 45%. However, 60% of patients experienced a grade 3–4 adverse event, and significant hepatotoxicity led to closure of the nivolumab/pazopanib arm after the first cohort. The nivolumab/sunitinib arms combined (varying by dose of nivolumab) included both previously treated and untreated patients and yielded an ORR of 52%. 73% of patients on this combination experienced a grade 3–4 AE, and though initially this combo showed less hepatotoxicity, effects on liver enzymes were prominent. The significant increase in toxicity of these regimens has discouraged further studies utilizing these combinations. Final results for both toxicity and efficacy are awaited to better understand the value of this combination. Whether altering the checkpoint inhibitor or the TKI will make a difference is still a source of interest. Pembrolizumab is being studied in combination with pazopanib in a Phase I/II study in patients with previously untreated patients with mRCC (NCT02014636). The design includes a standard dose, followed by a three arm, randomized Phase II portion looking at the combination versus either drug alone. In a Phase Ib dose finding study, pembrolizumab is also being combined with axitinib, a TKI associated with much less hepatotoxicity, in previously untreated patients (NCT02133742). Preliminary results of the first 11 patients were presented at the 2015 Kidney Cancer Symposium [48]. In regards to toxicity, two patients discontinued treatment due to related AEs and 73% of patients experienced grade 3 AEs, but most were reversible and no patients discontinued treatment due to hepatotoxicity. 6 patients had confirmed PRs and all 11 experienced at least some degree of tumor shrinkage. Enrollment of 55 total patients is now completed with results awaited. Other planned combination trials are listed in Table 3.

Bevacizumab, a mAb that also works to inhibit angiogenesis via inhibition of the circulating ligand VEGF-A, is approved for use in mRCC combined with interferon-alfa based on data from Phase III trials [49,50]. Bevacizumab is not known to be hepatotoxic, so given the initial experience combining the oral TKIs with nivolumab, this combination is attractive. Bevacizumab was investigated in combination with the anti-PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab in a Phase I trial with a cohort of patients with mRCC [51]. As presented at the 2015 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, 12 patients were evaluable for toxicity, 10 for response, with 83% of patients receiving this combination as their first line of systemic therapy in the metastatic setting. No grade 3–4 AEs were attributed to atezolizumab. The ORR was 40%. Currently, atezolizumab is being studied in combination with bevacizumab as an initial treatment for patients with mRCC in Phase II and Phase III studies. In a three-armed, randomized Phase II study, treatment naive patients will receive atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab, or sunitinib as a single agent, until disease progression, with the option to crossover to the combination arm for patients progressing after sunitinib (NCT01984242). This trial has completed accrual with analysis ongoing. A randomized Phase III trial comparing the combination of atezolizumab/bevacizumab to sunitinib is currently open and recruiting (NCT02420821). Combining bevacizumab with pembrolizumab is also currently being tested for safety in patients with mRCC in a Phase I/II trial (NCT02348008).

Checkpoint blockade along with bevacizumab is being explored in a presurgical setting combined with nivolumab. For some patients with mRCC, a cytoreductive nephrectomy is performed based on data from the pre-TKI era demonstrating an overall survival benefit for patients receiving surgery prior to systemic therapy with IFN-α [52,53]. While the utility of this intervention is unproven during the TKI era (prospective trials ongoing), interest may be further re-energized with the emergence of checkpoint inhibition. A three-arm, randomized, Phase II study is currently accruing patients to evaluate the role of nivolumab with or without bevacizumab or ipilimumab prior to planned cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients surgically eligible (NCT02210117).

Combinations of checkpoint inhibitors with cytokines & vaccines

Given the dynamic nature of the immune system, there is interest in exploring exogenous ways of priming or manipulating the immune milieu to favor a synergistic response when combined with checkpoint inhibition. One strategy being explored in multiple studies harks back to a previous iteration of treatments for mRCC. IFN-α is a type I cytokine previously in wide use for systemic therapy in patients with mRCC; however, its role has largely been replaced by the TKIs, and now by newer immunotherapies as well. IFN-α has been evaluated in several large trials for patients with mRCC and as a single agent yields an ORR ranging from 7.5–16% [54–56]. This cytokine has also been shown to play an integral role in recruitment and immune recognition during the antitumor response [57]. IFN-γ, the only type II interferon, has a less triumphant role as an anticancer agent, failing to improve survival as a single agent in randomized Phase III trials for various malignancies [58,59]. Nonetheless, its importance in the antitumor immune response is well studied. Dunn and colleagues outlined its many important functions in fostering immunosurveillance in their description of the cancer immunoediting process [60]. Notably, IFN-γ is also known to be a key regulator of PD-L1 expression, and Taube and colleagues have demonstrated that IFN-γ is an essential component of highly PD-L1 enriched tumors [61]. Consequently, combinations of these cytokines with PD-1 pathway inhibitors offer intriguing opportunities to prime the tumor microenvironment and potentially work synergistically to increase efficacy.

As mentioned previously, pembrolizumab is being combined with pegylated-IFN-α or ipilimumab in a randomized Phase I/II study of patients with mRCC or melanoma (NCT02089685). This study is closed to accrual, but not yet reported in RCC. Atezolizumab is being studied combined with conventional IFN-α in a Phase I dose-finding study (NCT02174172). While this study also includes other tumor types and a combined atezolizumab/ipilimumab arm, the mRCC patients will only be accrued to the arm including IFN-α, and accrual is ongoing. One study is underway utilizing IFN-γ in combination with nivolumab (NCT02614456). This is a Phase I dose-finding study exploring a short course of IFN-γ as induction, followed by combination therapy, in select, advanced tumors with an expansion cohort for patients with mRCC.

Another strategy being employed to prime the immune system includes the use of various cell and vector-based vaccines that attempt to sensitize the immune response to a specific tumor antigen and generate a targeted antitumor response [62]. One current combination involves pidilizumab (CT-011), a mAb against PD-1 derived using an IgG1 base to enable antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, along with a dendritic cell-RCC (DC-RCC) fusion vaccine. DCs function as potent antigen presenting cells and play an integral role in stimulating a primary immune response. The vaccine is generated by fusing autologous tumor cells with host DCs to create a population of DCs that express the entire tumor antigen repertoire, as opposed to one antigen which can more easily be downregulated by the tumor as a defense mechanism [63]. This combination and the PD-1 inhibitor alone are being assessed in a Phase II trial in patients with mRCC during any line of therapy (NCT01441765). The study has completed accrual, but has not yet reported results.

Adjuvant & neoadjuvant settings

Most of the trials discussed thus far have been evaluating patients with mRCC. While the durability of responses seen in some patients in this setting is encouraging, there is little expectation that most, if any, of these patients will be truly ‘cured’ of their cancer. On the other hand, the potential to apply the theories of checkpoint inhibition to the setting of early stage disease, with the goal of initiating and maintaining a lifelong antitumor response after resection of a localized mass, is intriguing as a strategy to increase the cure fraction among patients with localized high-risk RCC.

Currently, no FDA-approved therapy exists for the adjuvant treatment of patients with early stage RCC. Despite their success in the metastatic setting, the efficacy of oral TKIs has not translated to improved outcomes when administered after primary surgery, most notably highlighted by the disappointing results of the ASSURE trial evaluating adjuvant sorafenib and sunitinib [64]. With the advent of checkpoint inhibitors, the logical next step is to determine whether these agents could have a role in this setting. However, there are important biological implications to consider. First, the mechanism of action with checkpoint inhibition relies on the presence of tumor antigens to be recognized and targeted by immune cells. After a resection of a primary tumor mass, there may be little, if any, tumor antigen remaining, which may subject patients to the toxicity of therapy without a clear mechanism for benefit. Furthermore, there is evidence that after surgical resection of a kidney tumor, PD-1 expression on immune cells is rapidly and significantly reduced, potentially eliminating the target of a PD-1 inhibitor [65]. These issues have created uncertainty regarding the optimal design of purely adjuvant studies using checkpoint inhibitors, and thus far none have been opened for accrual.

A rational strategy to circumvent some of these concerns is neoadjuvant administration instead of, or in addition to, adjuvant use. This design allows for increased tumor antigen burden at the initiation of treatment to maximize desired immune recognition. It enables a more objective measure of response radiologically, while also enriching pathologic assessments pre and post treatment to support correlative biomarker exploration. Accordingly, multiple trials are currently planned using this design. Nivolumab is being evaluated in two separate, small, single arm trials in slightly different patient populations (NCT02575222, NCT02595918). Pembrolizumab is also being studied in one trial in the neoadjuvant setting, and this trial has begun accruing patients (NCT02212730). Data from these trials will be mostly explorative and hypothesis-generating to support further randomized designs as questions clearly remain. Some of these include the optimal number of doses and time planned preoperatively, whether postoperative treatment should be offered, and whether it could be administered in a brief or extended maintenance fashion. However, since (neo)adjuvant trials take a long time to produce results, the combined Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ECOG-ACRIN, EA) is in the final stages of planning a large, multicenter, two-armed, randomized, Phase III perioperative trial, The EA8143 (PROSPER trial) has been granted National Cancer Institute approval and will compare two doses of nivolumab followed by surgery and post-op nivolumab for nine months, versus surgery followed by observation alone, in high-risk RCC patients.

Future perspective & questions

While the FDA-approval of nivolumab marks the beginning of what may prove to be the new immunotherapy era in the treatment of mRCC, it does inject some uncertainty into the evolving treatment dogma. The approval of nivolumab in mRCC is in the second-line metastatic setting, after progression on a first line TKI. This establishes a new standard of care for most patients with mRCC to receive either sunitinib or pazopanib as their initial treatment, followed by nivolumab in the second line, as it has demonstrated a clear OS benefit compared with everolimus in this setting [16]. Based on the path of prior oncologic agents, one might expect the next logical step would be a comparison of nivolumab against a TKI in the first line setting. However, that study has not been planned. Instead, the dual checkpoint blockade combination of ipilimumab/nivolumab is currently the immunotherapy regimen being evaluated in comparison to sunitinib for treatment-naive patients. If this study meets its primary endpoint, where does that leave us? Does ipilimumab/nivolumab become the de facto treatment of choice for all patients in the first line setting? Importantly, we know from the preliminary results from the Checkmate 016 trial, as well as from the melanoma population, that ipilimumab/nivolumab significantly increases the toxicity compared with PD-1 inhibition alone. How much excess toxicity are we willing to accept in the name of improved ORR, especially when some patients may achieve similar benefit, at a fraction of the risk, with single agent nivolumab?

This is where biomarkers may truly become indispensable. Early hope was high that PD-L1 expression on tumors would identify tumors that would respond to PD-1 inhibition, but subsequent studies have clearly demonstrated that PD-L1 expression, whether on the tumor or stromal cells, is not by itself sufficient to predict benefit from PD-1 inhibition in RCC. RCC trials to date have consistently illustrated that while high PD-L1 expression can enhance the likelihood of response, PD-L1 deficient tumors can still respond to treatment. In fact, the Checkmate 025 trial was the first immunotherapy trial to find no difference in efficacy between the PD-L1 positive and negative populations. While much of the focus of biomarker discovery in modern immunotherapy trials has focused on correlating with response, the true power may come from being able to predict which patients can derive benefit from PD-1 pathway inhibition alone, and which patients need combination therapy. Additionally, as it is likely that several combination strategies will demonstrate some clinical benefit, meticulous and rational biomarker assessments embedded in ongoing trials is crucial to be able to categorize patients by the strategy most likely to benefit them. It is our opinion that both single agent and dual checkpoint blockade strategies will ultimately develop a niche in this disease, with biomarkers utilized to help identify patients that can 'get away with' single agent therapy versus those that require dual therapy and the associated increased toxicity risks. The progress of some of the alternative combination strategies discussed may further segregate the current homogeneity of the mRCC patients towards more personalized approaches based on biomarkers and tumor and/or host immune biology.

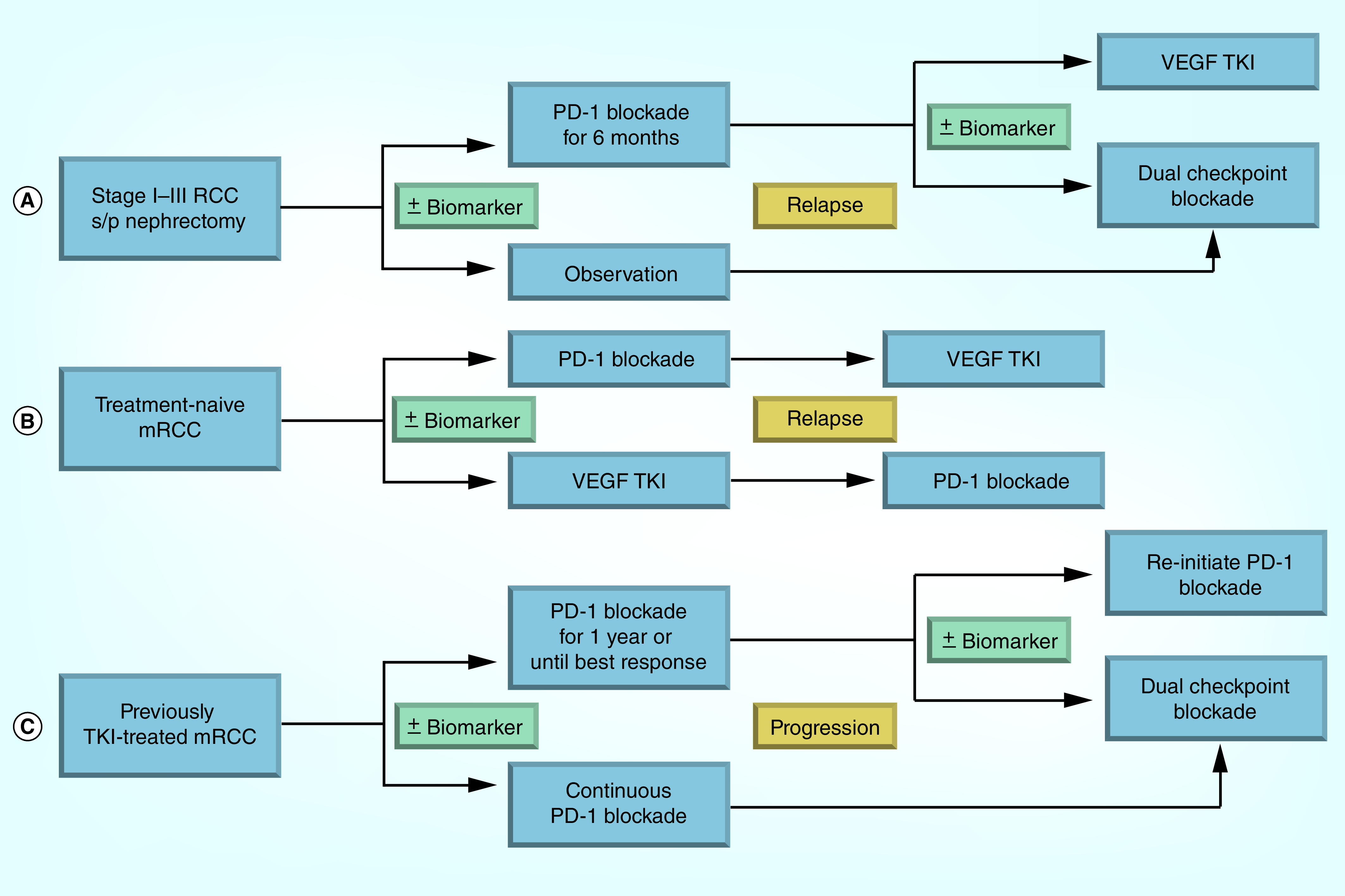

As more checkpoint inhibitors yield benefits in patients, both alone and in combination, having more options for patients is undoubtedly an advantage. But questions regarding sequencing, optimal dosing, duration and treatment schedules, maintenance versus intermittent treatment strategies, and patient selection remain. The potential emergence of checkpoint inhibition in early stage disease may have a trickle-down effect as well. If neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy demonstrates clinical benefit, what options will we have for those that do relapse? Will they still respond to immunotherapy upon retreatment in a recurrent metastatic setting, or will they need a “boost” from another agent? What if a patient develops a significant irAE in the adjuvant setting necessitating treatment discontinuation? Are they forever excluded from potentially life-altering therapy upon relapse, or can they be rechallenged? These are difficult questions without clear answers at this early stage, but ones that need to be considered and addressed. Supporting innovative clinical trial designs may be needed to help answer some of these, and many other, important questions. These could include sequential therapy trials, designs comparing adjuvant immunotherapy versus immunotherapy upon relapse, continuous versus intermittent PD-1 blockade with redosing at relapse, and rechallenging responders who stop drugs for toxicity and later relapse. Schematic examples of some of these designs are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. . Schematic examples of potential future clinical trial designs to investigate emerging issues with checkpoint blockade in renal cell carcinoma.

(A) Adjuvant study where patients are randomized to checkpoint blockade or observation. At relapse, the observation patients receive dual checkpoint blockade, while the patients who received checkpoint blockade postoperatively are randomized to dual blockade or a TKI. (B) Sequencing study for patients with previously untreated mRCC to investigate checkpoint blockade before and after TKI. (C) Study of continuous versus finite checkpoint blockade in mRCC, with dual checkpoint blockade added at relapse.

mRCC: Metastatic RCC; PD-1: Programmed death 1; RCC: Renal cell carcinoma; TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Summary & conclusion

Checkpoint inhibition has made its mark in the treatment of RCC and the future is bright. Nivolumab is now FDA-approved and available to patients as a standard of care, with more drugs undoubtedly on the way. PD-1 inhibitors offer the chance for durable remissions in a meaningful subset of patients and with a generally manageable toxicity profile. However, the majority of patients still do not achieve a clinical response and more work needs to be done for this resistant/refractory group. Rational combination approaches with TKIs, novel checkpoint inhibitors, and other immune modulators, offer some hope for improved efficacy. Additionally, extending the benefits we have begun to see in the metastatic setting to early stage disease presents a new opportunity for possible cures. We must continue to support clinical trials in mRCC, particularly those with strong preclinical foundations, and we must safely incorporate high yield correlatives when possible to maximize our knowledge for future trial designs and biomarker candidates. It is an exciting time to study and treat RCC, but the excitement may have really just begun.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Dr Zibelman has received institutionally directed clinical trial support from Horizon Pharma. Dr Geynisman has served on advisory boards for Pfizer, Novartis and Prometheus, and has received institutionally directed clinical trial support from Millennium and Pfizer. Dr Plimack has served on advisory boards and as consultant for Novartis, Acceleron, Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb and has received institutionally directed clinical trial support from Acceleron, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf

- 2. Flanigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, Picken MM. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. . 2003;4(5):385–390. doi: 10.1007/s11864-003-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SEER stat facts sheet: kidney and renal pelvis cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html

- 4. Wh C, Tc E. Spontaneous Regression of Cancer. . 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cancer ETSROCPC. Spontaneous regression of cancer. Prog. Clin. Cancer . 1967;3:79–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, Fyfe G. Long-term survival update for high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cancer J. Sci. Am. . 2000;6(Suppl. 1):S55–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fyfe G, Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, Sznol M, Parkinson DR, Louie AC. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. . 1995;13(3):688–696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas JS, Kabbinavar F. Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of current therapies and novel immunotherapies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. . 2015;96(3):527–533. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2013;369(8):722–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghatalia P, Morgan CJ, Sonpavde G. Meta-analysis of regression of advanced solid tumors in patients receiving placebo or no anti-cancer therapy in prospective trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. . 2015;98:122–136. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer . 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article represents a comprehensive overview of the role of immune checkpoints in cancer and how pharmacologically targeting these checkpoints can fundamentally alter the management of cancer.

- 12. Keir ME, Francisco LM, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in T-cell immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. . 2007;19(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Massari F, Santoni M, Ciccarese C, et al. PD-1 blockade therapy in renal cell carcinoma: current studies and future promises. Cancer Treat. Rev. . 2015;41(2):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jilaveanu LB, Shuch B, Zito CR, et al. PD-L1 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: an analysis of nephrectomy and sites of metastases. J. Cancer . 2014;5(3):166–172. doi: 10.7150/jca.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pham A, Ye DW, Pal S. Overview and management of toxicities associated with systemic therapies for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. . 2015;33(12):517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Mcdermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Landmark paper that established the role of the PD-1 inihibitor nivolumab in the treatment paradigm for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

- 17.Squibb B-M. Nivolumab full prescribing information. 2015. http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_opdivo.pdf

- 18. Thompson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer Res. . 2006;66(7):3381–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Food and Drug Administration. www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm436566.htm Nivolumab.

- 21. Choueiri T, Fishman M, Escudier B, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of nivolumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): association of biomarkers with clinical outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2015;33 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2839. Abstract 4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sekar R, Dimarco M, Patil D, Osunkoya A, Pollack B. PD-1 expression and its impact on survival in localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2016;34(Suppl. 2S) Abstract 568. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merck and Co. I. KEYTRUDA package insert. 2015. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf

- 24. Patnaik A, Kang SP, Rasco D, et al. Phase I study of pembrolizumab (MK-3475; anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer. Res. . 2015;21(19):4286–4293. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mcdermott DF, Sosman JA, Sznol M, et al. Atezolizumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: long-term safety, clinical activity, and immune correlates from a Phase Ia study. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2016;34(8):833–842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heery CR, O'sullivan Coyne GH, Marte JL, et al. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015. Chicago, IL, USA: 29 May – 2 June 2015. Pharmacokinetic profile and receptor occupancy of avelumab (MSB0010718C), an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, in a Phase I, open-label, dose escalation trial in patients with advanced solid tumors. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly K, Patel MR, Infante JR, et al. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015. Chicago, IL, USA: 29 May – 2 June 2015. Avelumab (MSB0010718C), an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors: assessment of safety and tolerability in a Phase I, open-label expansion study. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell . 2015;27(4):450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O'day SJ, Hamid O, Urba WJ. Targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) Cancer . 2007;110(12):2614–2627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hodi FS, O'day SJ, Mcdermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Landmark paper that provided the first evidence that immune checkpoint blockade, in this case with CTLA-4 inhibition, could improve survival for the management of cancer in the setting of metastatic melanoma.

- 32. Yang JC, Hughes M, Kammula U, et al. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J. Immunother. . 2007;30(8):825–830. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318156e47e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2006;24(15):2283–2289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ribas A, Kefford R, Marshall MA, et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing tremelimumab with standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2013;31(5):616–622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seetharamu N, Ott PA, Pavlick AC. Novel therapeutics for melanoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. . 2009;9(6):839–849. doi: 10.1586/era.09.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rini BI, Stein M, Shannon P, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation trial of tremelimumab plus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer . 2011;117(4):758–767. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Landmark paper that first reported the promising efficacy of dual check-point blockade in a melanoma population.

- 38.Hammers HJ, Plimack ER, Infante JR, et al. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015. Chicago, IL, USA: 29 May – 2 June 2015. Expanded cohort results from CheckMate 016: a Phase I study of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Infante JR, Goel S, Tavakkoli F, et al. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015. Chicago, IL, USA: 29 May – 2 June 2015. A Phase I, multicenter, open-label, first-in-human study to evaluate MEDI0680, an anti-programmed cell death-1 antibody, in patients with advanced malignancies. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grosso JF, Kelleher CC, Harris TJ, et al. LAG-3 regulates CD8+ T cell accumulation and effector function in murine self- and tumor-tolerance systems. J. Clin. Invest. . 2007;117(11):3383–3392. doi: 10.1172/JCI31184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brignone C, Escudier B, Grygar C, Marcu M, Triebel F. A Phase I pharmacokinetic and biological correlative study of IMP321, a novel MHC class II agonist, in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer. Res. . 2009;15(19):6225–6231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moon YW, Hajjar J, Hwu P, Naing A. Targeting the indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase pathway in cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer . 2015;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0094-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat. Rev. Cancer . 2005;5(4):263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gangadhar TC, Hamid O, Smith DC, et al. Preliminary results from a Phase I/II study of epacadostat (incb024360) in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with selected advanced cancers. J. Immunother. Cancer . 2015;3(Suppl. 2):O7. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized Phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2010;28(6):1061–1068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Amin A, Plimack ER, Infante JR, et al. Nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in combination with sunitinib or pazopanib in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) J. Clin. Oncol. (Meeting Abstracts) . 2014;32(Suppl. 15):5010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choueiri T, Plimack ER, Gupta S, et al. 14th International Kidney Cancer Symposium. Miami, FL, USA: 6–7 November 2015. Phase Ib dose-finding study of axitinib plus pembrolizumab in treatment-naive patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Escudier B, Bellmunt J, Négrier S, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (AVOREN): final analysis of overall survival. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2010;28(13):2144–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa versus interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results of CALGB 90206. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2010;28(13):2137–2143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sznol M, Mcdermott DF, Jones SF, et al. Phase Ib evaluation of MPDL3280A (anti-PDL1) in combination with bevacizumab (bev) in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) ASCO Meeting Abstracts . 2015;33(Suppl. 7):410. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. . 2001;345(23):1655–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mickisch G, Garin A, Van Poppel H, De Prijck L, Sylvester R. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet . 2001;358(9286):966–970. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Collaborators MRCRC. Interferon-α and survival in metastatic renal carcinoma: early results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet . 1999;353(9146):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Minasian LM, Motzer RJ, Gluck L, Mazumdar M, Vlamis V, Krown SE. Interferon alfa-2a in advanced renal cell carcinoma: treatment results and survival in 159 patients with long-term follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. . 1993;11(7):1368–1375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.7.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Negrier S, Escudier B, Lasset C, et al. Recombinant human interleukin-2, recombinant human interferon alfa-2a, or both in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 1998;338(18):1272–1278. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fuertes MB, Kacha AK, Kline J, et al. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8α+ dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. . 2011;208(10):2005–2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gleave ME, Elhilali M, Fradet Y, et al. Interferon gamma-1b compared with placebo in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. . 1998;338(18):1265–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kleeberg U, Suciu S, Bröcker E, et al. Final results of the EORTC 18871/DKG 80–1 randomised Phase III trial: rIFN-α2b versus rIFN-γ versus ISCADOR M® versus observation after surgery in melanoma patients with either high-risk primary (thickness >3 mm) or regional lymph node metastasis. Eur. J. Cancer . 2004;40(3):390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Phase IGP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat. Immunol. . 2002;3(11):991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Landmark paper establishing the concept of the three phases of immunosurveillance in the control of cancer in the human host.

- 61. Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci. Transl. Med. . 2012;4(127):127ra137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Berzofsky JA, Terabe M, Wood LV. Strategies to use immune modulators in therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Semin. Oncol. . 2012;39(3):348–357. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Avigan DE, Vasir B, George DJ, et al. Phase I/II study of vaccination with electrofused allogeneic dendritic cells/autologous tumor-derived cells in patients with stage IV renal cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. . 2007;30(7):749–761. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3180de4ce8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Initial results from ASSURE (E2805): adjuvant sorafenib or sunitinib for unfavorable renal carcinoma, an ECOG-ACRIN-led, NCTN Phase III trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts . 2015;33(Suppl. 7):403. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Macfarlane AWT, Jillab M, Plimack ER, et al. PD-1 expression on peripheral blood cells increases with stage in renal cell carcinoma patients and is rapidly reduced after surgical tumor resection. Cancer Immunol. Res. . 2014;2(4):320–331. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Motzer R, Rini B, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized Phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. . 2015;33(13):1430–1437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]