Abstract

Objective:

Personalized normative feedback, in which a respondent’s perceived norms are contrasted with more accurate estimates of alcohol use, has been found to be an effective component in brief alcohol interventions. Less certain is how the impact of feedback as a mediator of behavior change may depend on, or be moderated by, gender. This study examined differences in mediation through two descriptive norms—the number of drinks consumed per occasion and frequency of drinking occasions—using data from the evaluation of a military web-based alcohol intervention.

Method:

Gender differences in mediation of the Drinker’s Check-Up’s effects through descriptive norms were examined with multiple group path models and were tested with Wald and bootstrap confidence intervals for significance.

Results:

Results varied by the type of descriptive norm. Mediation by perceived norms about the number of drinks peers consumed did not vary significantly by gender. In contrast, mediated effects through norms about how often peers drank differed significantly by gender for the number of days alcohol was consumed, the number of binge episodes, heavy drinker status, and the number of drinks consumed per drinking episode. Female military personnel showed a greater number of mediated effects through norms about drinking frequency than did males.

Conclusions:

Differences in mediation depend on the type of descriptive norm acting as mediator as well as the type of alcohol use outcome. Further research on these differences may enable tailoring of interventions to maximize the effectiveness of norms as agents of alcohol use change.

Alcohol misuse by military personnel and its consequences are perennial concerns for the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). Heavy alcohol use (defined as 5 [4 for women] or more drinks on one occasion) by military personnel has consistently been higher than in civilian counterparts, especially for men ages 18–25 (Bray et al., 2006, 2009; Meadows et al., 2018). Binge and heavy drinking have increased steadily in active-duty personnel since 1998 (Bray et al., 2006, 2013) and have remained elevated (Meadows et al., 2018). Misuse of alcohol has been linked to significant productivity loss and negative social- and service-related consequences that directly impinge on military readiness (Ames & Cunradi, 2004; Jonas et al., 2010; Mattiko et al., 2011; Waller et al., 2015).

The elevated rate of alcohol misuse and demands on active-duty personnel have led the DOD to adopt methods to address problem drinking that have wide reach and acceptability, low demands for personnel time, and the potential for changing alcohol use behaviors. All of these features have been touted as advantages of web- or computer-based interventions for problem drinkers and high-risk young adults such as military personnel or college students (Balhara & Verma, 2014; Cadigan et al., 2015; Smedslund et al., 2017). Several web-based programs have addressed alcohol in the military, the largest of which was The Program for Alcohol Training, Research, and Online Learning (PATROL; Pemberton et al., 2011). PATROL included two independent interventions. One intervention, Drinker’s Check-Up (DCU), significantly reduced multiple alcohol use behaviors at 1-and 6-month follow-up assessments. Although DCU targeted multiple mechanisms of behavior change, the intervention’s effects on alcohol use were primarily achieved through changes in two descriptive norms: the perceived number of drinks consumed on each drinking occasion and the perceived frequency of drinking by same-gender peers (Williams et al., 2009). Descriptive norms about peer drinking behavior have been consistently linked to personal drinking behavior in college students (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Perkins, 2002; Reid & Carey, 2015) as well as active-duty and veteran military personnel (Krieger et al., 2017; Poehlman et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2009). Both groups have been found to overestimate heavy drinking by peers as well as the degree of approval of heavy drinking and related problems (Neighbors et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2008; Pemberton et al., 2011). Feedback about one’s perceived norms regarding alcohol use compared with actual estimates of use has been a generally successful, theoretically based strategy for reducing heavy alcohol use (Dempsey et al., 2018; Larimer et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2010; Walters et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2009).

Although normative feedback has been found to be an effective intervention component, questions remain about the mechanisms and limitations of how norms affect drinking behavior, especially in military settings. Gender has been suggested as one factor that may play a role in treatment response to norms. However, prior studies of gender and norm-related changes in alcohol use have found relatively few differences in outcomes for gender-specific versus gender-neutral normative feedback (e.g., Lojewski et al., 2010; Lewis & Neighbors, 2007; Neighbors et al., 2010). Fewer studies have examined differences by gender on the mechanism or mediated pathway of behavior change. Lewis and Neighbors (2007) concluded that gender-specific norms were a significant mediator of a normative feedback-based intervention for women but not for men.

In addition to sparse research on gender moderation of norms as mediators, the existing research suffers from methodological limitations. Many previous studies have relied on causal steps methods and comparative model fit for evaluating mediation, approaches that are not optimal (MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon et al., 2002a). In addition, these methods are not amenable to testable comparisons of mediated effects across gender (Williams & MacKinnon, 2008) and do not address the null hypothesis that the difference in mediated effects through norms for men and women is not statistically different from zero.

The current study was conducted to examine moderation of the perceived norms-mediated effects of DCU by gender (i.e., moderated mediation). The perceived number of drinks per occasion and perceived frequency of drinking occasions were previously found to be significant mediators of DCU on multiple alcohol use outcomes in PATROL. The mediated effects or pathways from DCU through both norms to a variety of alcohol use outcomes were tested for overall differences across male and female active-duty personnel.

Method

Sample and design

The PATROL intervention and evaluation was approved by RTI International’s Institutional Review Board and used a voluntary convenience sample obtained from eight U.S. military installations (two from each service branch). A total of 3,889 active-duty personnel enrolled and provided consent before participation. At 1-month follow-up, 1,369 personnel completed the survey (35.2%) and 913 personnel completed the 6-month follow-up survey (23.5%). Consistent with the overall population of military personnel, the majority of the baseline sample was male (83%), non-Hispanic Whites (66%), educated beyond high school (65%), and between ages 21 and 34 (63%). The analysis sample for this study included all personnel assigned to either the control condition (baseline n = 914) or the DCU treatment (baseline n = 1,470).

Treatment condition was assigned following a baseline assessment that included questions about alcohol use and potential mediators of behavior change. Participants were invited to complete the follow-up surveys at 1 and 6 months after baseline. After the 1-month follow-up, control participants were offered the opportunity to receive one of the interventions, determined randomly. A total of 291 controls chose to receive the intervention and were randomized to either DCU or the alternative intervention. Because of this further attenuation of the 6-month control group sample and because mediated effects with outcomes measured at 1 month and 6 months were largely consistent (Williams et al., 2009), only the baseline and 1-month data were used in this study.

Drinker’s Check-Up

The DCU is a brief motivational intervention (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) designed by behavior therapy associates to reduce problem drinking (e.g., heavy or binge drinking, alcohol dependence). DCU is based on social learning and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1978, 1986), the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock et al., 1988), and Prochaska and colleagues’ (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1986; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change. It was specifically designed for computer administration and builds on previous successful brief interventions that targeted alcohol use without face-to-face interviews (e.g., Agostinelli et al., 1995; Kypri et al., 2004). Readiness to change, perceived norms about alcohol use, and judgments and cognitions about the benefits and consequences of alcohol use were all implicated as mediators of DCU and were assessed in the PATROL evaluation. Participants were provided with feedback about their drinking quantity and frequency compared with adults of the same gender in the United States and in their particular service branch. Feedback about estimated peak blood alcohol concentration was also given. DCU has been found to be effective in reducing quantity and frequency of drinking in military and civilian samples (Hester et al., 2005; Pemberton et al., 2011). Layouts, graphics, and multimedia content were tailored to a military population for PATROL (e.g., uniformed personnel were present in vignettes about drinking instead of civilians). More adaptation details are found in Pemberton et al. (2011) and the supplemental material for this article.

Measures

Perceived norms

Two measures of perceived norms were included in the PATROL surveys. The perceived normative number of drinks per drinking occasion (quantity) was assessed with a single item (responses ranged from 0 to 25). A second single item measured the perceived normative number of drinking occasions in the past month for same-age peer personnel (frequency), with responses ranging from 0 to 30. Norms were gender personalized, asking about a “typical” military peer of the same age and gender as the respondent.

Outcomes

Multiple outcomes were used to reflect a variety of behaviors related to problematic drinking and were measured at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months. The time frame for all outcomes was the past 30 days and included the following.

(A) Average number of days that alcohol was used: Respondents indicated how often they had consumed alcohol in the past month, with seven response options ranging from “Didn’t drink any alcohol in the past 30 days” to “28–30 days (about every day).”

(B) Average number of drinks consumed per drinking occasion: A single item measured drink quantity, ranging from 0 to 22 drinks.

(C) Number of days perceived drunk: This outcome was a single item measuring the number of days per week in the past month that respondents perceived themselves to be drunk.

(D) Binge drinker status: Respondents were classified as binge drinkers if they reported drinking five (for men) or four (for women) or more drinks on one occasion (at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) in the past month.

(e) Binge drinking episodes: This item measured the frequency of binge drinking in the past month and ranged from 0 to 30 days (or every day).

(f) Heavy drinker status: Participants were classified as heavy drinkers if they reported four or more binge episodes in the past month (or an average of one or more binge episodes a week).

(G) Estimated peak blood alcohol concentration: Estimated peak blood alcohol concentration was calculated from respondents’ self-reported heaviest drinking episode, based on their sex, weight, ounces of ethanol consumed, and duration of the episode.

Demographic and military control measures

Several demographic and military-related measures assessed at baseline were included as control items related to alcohol use based on past research (e.g., Bray et al., 2013; Mattiko et al., 2011). These were service branch (Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force), gender, age, minority status, family status (married with spouse present or living as married with partner present vs. divorced, separated, widowed, single, never married, or married with nonpresent spouse), and rank (enlisted personnel vs. officers). More problematic drinking, heavy drinking in particular, has been associated with personnel who are male, younger, not racial/ethnic minorities, single, and enlisted. Sample characteristics at baseline and 1-month follow-up are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics at baseline and 1-month follow-up

| Drinker’s Check-Up | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristic | Baseline (n = 1,470) % | 1-month follow-up (n = 386) % | Baseline (n = 914) % | 1-month follow-up (n = 637) % |

| Service | ||||

| Army | 1.8 | 2.3 | 9.4 | 7.9 |

| Navy | 52.1 | 40.9 | 43.5 | 31.1 |

| Marine Corps | 14.4 | 10.4 | 16.2 | 14.2 |

| Air Force | 31.7 | 46.4 | 30.9 | 46.9 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 83.3 | 78.8 | 82.2 | 80.7 |

| Female | 16.7 | 21.2 | 17.8 | 19.4 |

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 27.9 | 31.1 | 28.5 | 30.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Minority | 36.7 | 30.8 | 35.2 | 27.6 |

| Not minority | 63.3 | 69.2 | 64.8 | 72.4 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or living as married | 57.3 | 64.0 | 59.9 | 67.3 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed, | ||||

| single, never married | 42.7 | 36.0 | 40.2 | 32.7 |

| Enlisted | 90.3 | 88.3 | 89.9 | 86.7 |

Analysis

A multiple-group multiple-mediator/multiple-outcome model was used to examine the hypothesized gender moderation of DCU’s mediated effects through norms. Contrasts of gender-specific mediated effects were estimated and were evaluated for statistically significant differences. Unlike many moderated mediation models, these models specifically test the null hypothesis of no difference in the mediated effect as compared with a difference in individual paths that compose the indirect effect (MacKinnon, 2000; Williams & MacKinnon, 2008). A simplified version of this model with only a single outcome and mediator is shown in Figure 1. Mediated effects were estimated as the product of two variables, a (the path coefficient from program to mediator), and b (the path coefficient from mediator to an outcome). Subscripts denote the gender-specific mediated effects, aMbM for men and aFbF for women. The remaining, unmediated by norms, portion of the program effect is represented by the c path coefficients. Male and female models were estimated simultaneously with no equality constraints across groups. In the full model, both norms mediators at 1 month were included and were predicted by their baseline values, their treatment group status, and the control variables. All alcohol outcomes at 1 month were included and were predicted by the control variables, outcomes at baseline, program group status, and mediators at 1 month.

Figure 1.

Multiple group mediation model. DCU = Drinker’s Check-Up.

Unlike outdated causal steps methods for mediation, significant direct paths (c in Figure 1) were not a prerequisite for estimating indirect effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Examining mediated effects and the a and b component paths—especially as part of the evaluation of prevention programs with multiple mediators—not only provides valuable information on how behavioral change was achieved but also may suggest reasons change did not occur (Chen, 1990). This rationale extends to analyses of contrasts of mediated effects. When a significant difference across aMbM and aFbF is found, it is likely informative to examine the gender-specific a and b paths to explain the difference (e.g., the program affects the mediator for men but not for women, the mediator was not significantly related to alcohol use for women). Conversely, it may also be useful to examine the paths that make up the indirect effect when there is no difference. For example, differences in program impact on the mediator in one group may be offset by a greater association between that mediator and the outcome in the same group. These differences play an important role in understanding how programs do or do not achieve behavior change and may suggest refinements or changes.

Gender differences in mediation were examined with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the point estimate of the difference between aMbM and aFbF. One single-sample method—Wald CI—and two resampling methods—percentile and bias-corrected percentile bootstrapped CI (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993)—were used. CIs containing zero indicated a non–statistically significant difference. Bootstrap methods have superior statistical properties for testing contrasts of mediated effects (Williams & MacKinnon, 2008). Models were estimated in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017) with 1,000 bootstrap resamples for percentile and bias-corrected bootstrap CIs.

Results

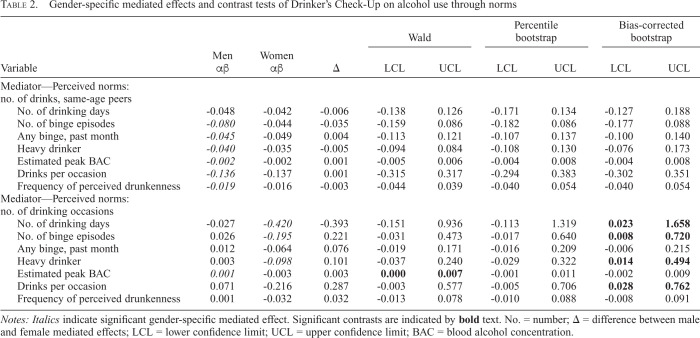

Table 2 displays the confidence intervals for the Wald and bootstrap tests of mediated effect contrasts. There were no significant gender differences for any of the mediated effects through perceived norms about number of drinks. Mediation of DCU by this norm was not conditional on gender for any alcohol use outcome.

Table 2.

Gender-specific mediated effects and contrast tests of Drinker’s Check-Up on alcohol use through norms

| Wald | Percentile bootstrap | Bias-corrected bootstrap | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Men αβ | Women αβ | Δ | LCL | UCL | LCL | UCL | LCL | UCL |

| Mediator—Perceived norms: no. of drinks, same-age peers | |||||||||

| No. of drinking days | -0.048 | -0.042 | -0.006 | -0.138 | 0.126 | -0.171 | 0.134 | -0.127 | 0.188 |

| No. of binge episodes | -0.080 | -0.044 | -0.035 | -0.159 | 0.086 | -0.182 | 0.086 | -0.177 | 0.088 |

| Any binge, past month | -0.045 | -0.049 | 0.004 | -0.113 | 0.121 | -0.107 | 0.137 | -0.100 | 0.140 |

| Heavy drinker | -0.040 | -0.035 | -0.005 | -0.094 | 0.084 | -0.108 | 0.130 | -0.076 | 0.173 |

| Estimated peak BAC | -0.002 | -0.002 | 0.001 | -0.005 | 0.006 | -0.004 | 0.008 | -0.004 | 0.008 |

| Drinks per occasion | -0.136 | -0.137 | 0.001 | -0.315 | 0.317 | -0.294 | 0.383 | -0.302 | 0.351 |

| Frequency of perceived drunkenness | -0.019 | -0.016 | -0.003 | -0.044 | 0.039 | -0.040 | 0.054 | -0.040 | 0.054 |

| Mediator—Perceived norms: no. of drinking occasions | |||||||||

| No. of drinking days | -0.027 | -0.420 | -0.393 | -0.151 | 0.936 | -0.113 | 1.319 | 0.023 | 1.658 |

| No. of binge episodes | 0.026 | -0.195 | 0.221 | -0.031 | 0.473 | -0.017 | 0.640 | 0.008 | 0.720 |

| Any binge, past month | 0.012 | -0.064 | 0.076 | -0.019 | 0.171 | -0.016 | 0.209 | -0.006 | 0.215 |

| Heavy drinker | 0.003 | -0.098 | 0.101 | -0.037 | 0.240 | -0.029 | 0.322 | 0.014 | 0.494 |

| Estimated peak BAC | 0.001 | -0.003 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.007 | -0.001 | 0.011 | -0.002 | 0.009 |

| Drinks per occasion | 0.071 | -0.216 | 0.287 | -0.003 | 0.577 | -0.005 | 0.706 | 0.028 | 0.762 |

| Frequency of perceived drunkenness | 0.001 | -0.032 | 0.032 | -0.013 | 0.078 | -0.010 | 0.088 | -0.008 | 0.091 |

Notes: Italics indicate significant gender-specific mediated effect. Significant contrasts are indicated by boldtext. No. = number; Δ = difference between male and female mediated effects; LCL = lower confidence limit; UCL = upper confidence limit; BAC = blood alcohol concentration.

In contrast, several mediated effects through norms about drinking frequency showed a difference by gender. The Wald CI indicated that the mediated effect on estimated peak blood alcohol concentration through this norm differed significantly between men and women. This result was incongruous with the bootstrap CI tests, which both indicated that there was not a significant gender difference in this effect. Because the bootstrap methods have superior statistical properties for mediation contrasts, this difference should be interpreted with caution, if at all. The bias-corrected bootstrap, the most statistically powerful method, suggested significant differences for four mediated effects. Male and female personnel differed significantly for their indirect effects on the number of drinking days, binge frequency, heavy drinker status, and drinks per occasion. For the first outcome, drinking days, men and women both showed negative mediated effects. This effect was nonsignificant for men, however, indicating that DCU did not change the number of days in which alcohol was used for male personnel. In contrast, the female-specific indirect effect was much greater in magnitude and was significant at p < .05. For the other three outcomes, men and women showed mediated effects that differed in direction. Two of these, the number of binge episodes and heavy drinking, were significant for women only, indicating that DCU decreased these alcohol behaviors in women through changes in perceived norms about the frequency of drinking occasions.

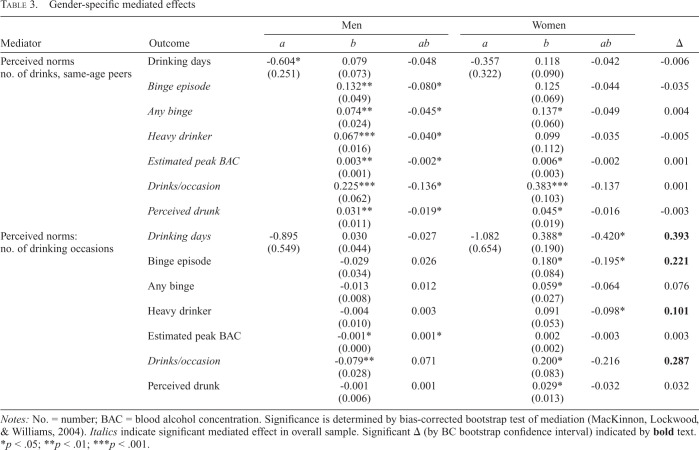

Table 3 displays the gender-specific mediated effects, their component a and b paths, and the difference in each mediated effect across gender (Δ). A greater number of significant mediated effects was found for male personnel—seven versus three for women. For male personnel, DCU changed alcohol behavior by first decreasing perceptions about how many drinks same-age peers consumed. Male perceptions of how frequently peers drank also changed more than those of female peers, but this path was not statistically significant. Female personnel showed less change in alcohol use and fewer mediated effects through perceived descriptive norms. Unlike their male counterparts, female personnel had significant mediated effects largely through perceptions about how often peers drank instead of norms about how much peers consumed.

Table 3.

Gender-specific mediated effects

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Outcome | a | b | ab | a | b | ab | Δ |

| Perceived norms no. of drinks, same-age peers | Drinking days | -0.604* (0.251) |

0.079 (0.073) |

-0.048 | -0.357 (0.322) |

0.118 (0.090) |

-0.042 | -0.006 |

| Binge episode | 0.132** (0.049) |

-0.080* | 0.125 (0.069) |

-0.044 | -0.035 | |||

| Any binge | 0.074** (0.024) |

-0.045* | 0.137* (0.060) |

-0.049 | 0.004 | |||

| Heavy drinker | 0.067*** (0.016) |

-0.040* | 0.099 (0.112) |

-0.035 | -0.005 | |||

| Estimated peak BAC | 0.003** (0.001) |

-0.002* | 0.006* (0.003) |

-0.002 | 0.001 | |||

| Drinks/occasion | 0.225*** (0.062) |

-0.136* | 0.383*** (0.103) |

-0.137 | 0.001 | |||

| Perceived drunk | 0.031** (0.011) |

-0.019* | 0.045* (0.019) |

-0.016 | -0.003 | |||

| Perceived norms: no. of drinking occasions | Drinking days | -0.895 (0.549) |

0.030 (0.044) |

-0.027 | -1.082 (0.654) |

0.388* (0.190) |

-0.420* | 0.393 |

| Binge episode | -0.029 (0.034) |

0.026 | 0.180* (0.084) |

-0.195* | 0.221 | |||

| Any binge | -0.013 (0.008) |

0.012 | 0.059* (0.027) |

-0.064 | 0.076 | |||

| Heavy drinker | -0.004 (0.010) |

0.003 | 0.091 (0.053) |

-0.098* | 0.101 | |||

| Estimated peak BAC | -0.001* (0.000) |

0.001* | 0.002 (0.002) |

-0.003 | 0.003 | |||

| Drinks/occasion | -0.079** (0.028) |

0.071 | 0.200* (0.083) |

-0.216 | 0.287 | |||

| Perceived drunk | -0.001 (0.006) |

0.001 | 0.029* (0.013) |

-0.032 | 0.032 | |||

Notes: No. = number; BAC = blood alcohol concentration. Significance is determined by bias-corrected bootstrap test of mediation (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Italics indicate significant mediated effect in overall sample. Significant Δ (by BC bootstrap confidence interval) indicated by boldtext.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

In addition to the gender-specific mediated effects, Table 3 shows the component paths from treatment condition to mediator and from mediator to alcohol outcome. These results are useful for examining the possible causes for any differences in mediated effects noted above or for the overall sample. Gender differences are apparent in the action theory of the intervention mechanism. DCU was successful in decreasing perceived norms about how many drinks same-age peers consumed per occasion but only for male personnel. The estimated change for female personnel was substantially lower and showed greater variability. In contrast, perceptions about how often same-age peers drank was unaffected in men but showed a marginally significant decrease in women.

Discussion

This study extends knowledge of pathways to alcohol behavior change through changes in descriptive norms and moderation of those pathways by gender. Overall, results were equivocal, with no significant differences in mediation through norms about drinking quantity and multiple significant contrasts (as evaluated by the bias-corrected bootstrap) by gender for effects with perceived drinking frequency as the mediator. Female personnel showed markedly less change in descriptive norms about the number of drinks consumed but also showed a slightly greater change in norms about drinking frequency than their male counterparts.

The results suggest several conclusions about gender moderation of indirect effects on alcohol use through perceived norms. First, changes in drinking as a result of changes to the perceived normative number of drinks does not appear to be impacted by gender. None of the mediated effect contrasts were significant by any method. Although the gender-specific mediated effects revealed significant mediation by norms about the number of drinks for men only, the magnitude of the male and female indirect effects through this norm were overall quite comparable. Despite a lack of significant contrasts, inspection of the individual a and b paths gives some support for differences in how men and women respond to norms about the number of drinks consumed. DCU had a much smaller impact on women’s perceptions about the normative number of drinks consumed, but this impact was offset by stronger links from the norm to the alcohol outcomes (the b paths) for female personnel, leading to very comparable mediated effect estimates for men and women.

A second conclusion is that gender does appear to moderate the mediation of alcohol use through norms about how often personnel drink. This type of normative feedback was relevant only for women. Third, gender-specific mediated effects indicated that women showed significant reductions in the number of drinking days, the frequency of binge drinking, and heavy drinking as a result of decreases in how often they perceived that peers drank. A fourth outcome, the number of drinks per occasion, showed a nonsignificant decrease through frequency norms, but this was significantly different from the (also nonsignificant) positive indirect effect in men. Unlike mediated effects through norms about the number of drinks consumed, the gender-specific indirect effects through this descriptive norm were quite different in magnitude, suggesting real gender differences in how this mechanism of behavior change functions.

This study exhibits several strengths not evident in many other examinations of web-based alcohol interventions and the role of normative feedback in how these interventions achieve behavior change. First, this study used state-of-theart methods for mediation analysis. Many earlier evaluations of mediation of drinking by norms (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2010; Lewis & Neighbors, 2007; Neighbors et al., 2004) relied on causal steps methods (e.g., the Baron & Kenny [1986] approach) of testing mediation. Those methods are underpowered compared with tests such as the bootstrap methods used in this study (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Wil liams & MacKinnon, 2008). In addition, this study examined moderated mediation with methods that explicitly tested the null that aMbM = aFbF. Past research on gender differences in mediation of interventions through norms (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2010; Lewis & Neighbors, 2007) has relied on mediation analysis that does not yield a point estimate of gender-specific indirect effects and has based its conclusions on essentially “eyeball” tests about the differences in mediation along gender lines. In contrast, this study rigorously compared estimates of mediated effects by gender using state-of-the-art statistical methods.

The sample for this study was also advantageous for extending the generalizability of previous research beyond college populations. Military personnel are a similar high-risk population (especially younger or more-junior-pay-grade personnel) but with significantly different roles and environments. Web-based interventions maximize the ease and uniformity of delivery as well as confidentiality for this group just as they do for college students (Kypri et al., 2003; Pemberton et al., 2011). The PATROL sample size was also much larger than those in similar studies, even after accounting for the attrition rate.

Although innovative and widening the knowledge base about web-based interventions in general and the role of normative feedback specifically, this study is not without limitations. The PATROL study had a large amount of attrition—approximately 61% at the 1-month follow-up. This amount of attrition is unfortunately not uncommon in either military or web-based studies (Linke et al., 2007; Ryan et al., 2007; Verheijden et al., 2007) and likely reflects factors such as war-time deployments, personnel mobility, and lack of incentives provided by installations following the initial assessment. As reported in previous PATROL studies (Pemberton et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2009), extensive exploratory analyses revealed no relationship between attrition and either treatment condition or alcohol use. Crucial to this study, dropouts did not vary by gender. These exploratory analyses suggest that methods appropriate for data missing at random (MAR), as used here, would still produce unbiased and efficient estimates (Little & Rubin, 2002). Another possible limitation related to sparse 6-month follow-up data is the use of only two waves of data for the mediation models.

This study was able to contrast mediation in men and women only for the models in Williams et al. (2009) with the mediators and outcome at the 1-month follow-up. Because of attrition, multiple group models to estimate contrasts with outcomes measured at the 6-month follow-up did not have sufficient nonmissing data to engage the EM algorithm and use MAR-appropriate estimation.

The causal hypothesis of a mediated effect includes a strong temporal requirement, leading some to argue that mediation is truly testable only with data with three or more assessments. However, three waves of assessment will not always ensure proper order, and it is often useful to explore indirect effects with fewer waves if temporal ordering can reasonably be assumed to be “nested” within a measurement occasion (i.e., the mediator is believed to change immediately after intervention although follow-up assessment of mediator and outcome occurs later; MacKinnon et al., 2002b).

Other possible limitations are measurement based. Perhaps most salient of these is the lack of measurement of gender identity. Past research suggests that gender identity and its importance can moderate the impact of norms received (Lewis & Neighbors, 2007). Increased identification may not only increase differences in outcomes associated with norms but also moderate the mediated effects through them. Another potential measurement limitation is the inclusion of only two descriptive norms. Although the norms included align well with the feedback from DCU, it is possible that other normative perceptions—such as the frequency of drunkenness or binge drinking prevalence—could mediate effects and differ by gender.

Last, some research has found that the impact of norms may be further mediated by personal attitudes or injunctive norms (Krieger et al., 2017). Injunctive norms were measured as a mediator in PATROL, but, consistent with prior research, this construct was not found to be an independent pathway to behavior change (Krieger et al., 2016). Further work is needed to examine a more complex mediation pathway that includes both types of norms and whether these paths differ by gender.

The current results suggest that further research is needed to clarify gender differences in how perceived norms affect interventions. This study found gender differences for one descriptive norm but not another. Several alcohol outcomes showed mediated effects for DCU through perceived number of drinking occasions only for women, and a number of these mediated effects were significantly different by gender. The much smaller number of female personnel in the military and the PATROL sample may account for the lack of overall effectiveness of norms about drinking frequency as a mechanism of behavior change since its impact seems largely confined to women. Future research with military and other noncollege samples is needed to put these findings into context.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Michael Pemberton, Sara Calvin, and Janice Brown for their thoughtful reviews and comments on previous drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R03DA029216 awarded to the author. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States Government.

References

- Agostinelli G., Brown J. M., Miller W. R. Effects of normative feedback on consumption among heavy drinking college students. Journal of Drug Education. 1995;25:31–40. doi: 10.2190/XD56-D6WR-7195-EAL3. doi:10.2190/XD56-D6WR-7195-EAL3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames G., Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Balhara Y., Verma R. A review of web based interventions focusing on alcohol use. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 2014;4:472–480. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.139272. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.139272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1978;1:139–161. doi:10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (Vol. 1) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Carey K. B. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray R. M., Brown J. M., Williams J. Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:799–810. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.796990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray R. M., Pemberton M. R., Hourani L. L., Witt M., Rae Olmsted K. L., Brown J. M., Bradshaw M. R.2008 Department of Defense survey of health related behaviors among active duty military personnel. 2009. Report prepared for TRICARE Management Activity, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs) and U.S. Coast Guard.

- Bray R. M., Hourani L. L., Rae Olmsted K. L., Witt M., Brown J. M., Pemberton M. R., Vandermaas-Peeler R.2005 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel. 2006. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235111853_2005_Department_of_Defense_Survey_of_Health_Related_Behaviors_Among_Active_Duty_Military_Personnel.

- Cadigan J. M., Haeny A. M., Martens M. P., Weaver C. C., Takamatsu S. K., Arterberry B. J. Personalized drinking feedback: A meta-analysis of in-person versus computer-delivered interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:430–437. doi: 10.1037/a0038394. doi:10.1037/a0038394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-T. Theory-driven evaluations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey R. C., McAlaney J., Bewick B. M. A critical appraisal of the social norms approach as an interventional strategy for health-related behavior and attitude change. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:2180. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02180. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B., Tibshirani R. J. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hester R. K., Squires D. D., Delaney H. D. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas W. B., O’Connor F. G., Deuster P., Peck J. C., Shake C., Frost S. S. Why Total Force Fitness? Military Medicine. 2010;175:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger H., Neighbors C., Lewis M. A., LaBrie J. W., Foster D. W., Larimer M. E. Injunctive norms and alcohol consumption: A revised conceptualization. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:1083–1092. doi: 10.1111/acer.13037. doi:10.1111/acer.13037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger H., Pedersen E. R., Neighbors C. The impact of normative perceptions on alcohol consumption in military veterans. Addiction. 2017;112:1765–1772. doi: 10.1111/add.13879. doi:10.1111/add.13879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K., Saunders J. B., Gallagher S. J. Acceptability of various brief intervention approaches for hazardous drinking among university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003;38:626–628. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg121. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K., Saunders J. B., Williams S. M., McGee R. O., Langley J. D., Cashell-Smith M. L., Gallagher S. J. Web-based screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2004;99:1410–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00847.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer M. E., Lee C. M., Kilmer J. R., Fabiano P. M., Stark C. B., Geisner I. M., Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. A., Neighbors C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:228–237. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke S., Murray E., Butler C., Wallace P. Internet-based interactive health intervention for the promotion of sensible drinking: Patterns of use and potential impact on members of the general public. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2007;9:e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e10. doi:10.2196/jmir.9.2.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R. J. A., Rubin D. B. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lojewski R., Rotunda R. J., Arruda J. E. Personalized normative feedback to reduce drinking among college students: A social norms intervention examining gender-based versus standard feedback. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2010;54:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose J., Chassin L., Presson C. C., Sherman S. J., editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research. London, England: Psychology Press; 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Hoffman J. M., West S. G., Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002a;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Taborga M. P., Morgan-Lopez A. A. Mediation designs for tobacco prevention research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68, Supplement. 2002b;1:S69–S83. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00216-8. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiko M. J., Olmsted K. L. R., Brown J. M., Bray R. M. Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.023. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows S. O., Engel C. C., Collins R. L., Beckman R. L., Cefalu M., Hawes-Dawson J., et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) Rand Health Quarterly. 2018;8(2):5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Larimer M. E., Lewis M. A. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Lewis M. A., Atkins D. C., Jensen M. M., Walter T., Fossos N., Larimer M. E. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. doi:10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Walker D., Rodriguez L., Walton T., Mbilinyi L., Kaysen D., Roffman R. Normative misperceptions of alcohol use among substance abusing army personnel. Military Behavioral Health. 2014;2:203–209. doi:10.1080/21635781.2014.890883. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen E. R., LaBrie J. W., Lac A. Assessment of perceived and actual alcohol norms in varying contexts: Exploring Social Impact Theory among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:552–564. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton M. R., Williams J., Herman-Stahl M., Calvin S. L., Bradshaw M. R., Bray R. M., Mitchell G. M. Evaluation of two web-based alcohol interventions in the U.S. military. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:480–489. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.480. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins H. W. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement 14. 2002:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman J. A., Schwerin M. J., Pemberton M. R., Isenberg K., Lane M. E., Aspinwall K. Socio-cultural factors that foster use and abuse of alcohol among a sample of enlisted personnel at four Navy and Marine Corps installations. Military Medicine. 2011;176:397–401. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00240. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., DiClemente C. C. Toward a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller W. R., Heather N., editors. Treating addictive behaviors (Vol. 110, pp. 3–27) New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., Velicer W. F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid A. E., Carey K. B. Interventions to reduce college student drinking: State of the evidence for mechanisms of behavior change. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock I. M., Strecher V. J., Becker M. H. Social learning theory and the Health BModel. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. doi:10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M. A. K., Smith T. C., Smith B., Amoroso P., Boyko E. J., Gray G. C., Hooper T. I. Millennium Cohort: Enrollment begins a 21-year contribution to understanding the impact of military service. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.05.009. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P. E., Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedslund G., Wollscheid S., Fang L., Nilsen W., Steiro A., Larun L.Effect of early, computerized brief interventions on risky alcohol use and risky cannabis use among young people. 2017. Oslo, Norway. Retrieved from https://campbellcollaboration.org/library/computerisedinteventions-youth-alcohol-cannabis-use.html.

- Verheijden M. W., Jans M. P., Hildebrandt V. H., Hopman-Rock M. Rates and determinants of repeated participation in a web-based behavior change program for healthy body weight and healthy lifestyle. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2007;9:e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.1.e1. doi:10.2196/jmir.9.1.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller M., McGuire A. C., Dobson A. J. Alcohol use in the military: Associations with health and wellbeing. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2015;10:27. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0023-4. doi:10.1186/s13011-015-0023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters S. T., Vader A. M., Harris T. R. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prevention Science. 2007;8:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. doi:10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J., Herman-Stahl M., Calvin S. L., Pemberton M., Bradshaw M. Mediating mechanisms of a military Web-based alcohol intervention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J., MacKinnon D. P. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2008;15:23–51. doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166. doi:10.1080/10705510701758166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]