Abstract

Objective:

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) programs have been effective for moderate reductions of alcohol use among participants in universal settings. However, there has been limited evidence of effectiveness in referring individuals to specialty care, and the literature now often refers to screening and brief intervention (SBI). This study examines documentation of substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses in a low-income Medicaid population to evaluate the effect of universal SBIRT on healthcare system recognition of SUDs, a first step to obtaining a referral to treatment (RT) for individuals with SUDs.

Method:

SBI patient data from Wisconsin's Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles (WIPHL) were linked to Wisconsin Medicaid claims data. A comparison group of Medicaid beneficiaries was identified from a matched sample of non-SBIRT clinics (total study N = 14,856). Hierarchical generalized linear modeling was used to assess rates of SUD diagnosis in the 12 months following receipt of SBIRT in WIPHL clinics compared with rates in non-SBIRT clinics. Analysis controlled for clinic, individual patient's health status, demographics, and baseline substance use diagnoses.

Results:

SBIRT was associated with greater odds of being diagnosed with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), alcohol abuse or dependence as well as drug abuse or dependence over the 12 months subsequent to receipt of the screen. The overall diagnostic rate for any DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence was 9.9% at baseline and 12.2% during the follow-up year. SBIRT patients had 42% (p = .003) greater odds of being diagnosed with a substance use disorder within 12 months relative to comparison clinic patients. However, there were very few claims for specialty SUD services.

Conclusions:

The presence of SBIRT in a primary care clinic appears to increase the awareness and recognition of patients with SUDs and a greater willingness of healthcare providers to diagnose patients with an alcohol or drug use disorder on Medicaid claims. Further research is needed to determine if this increase in diagnosis reflects integrated care for SUDs or if it leads to improved access to specialty care, in which case abandonment of the RT component of SBIRT may be premature.

Amajor dilemma in the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) movement has been the “RT” (referral to treatment). Reducing the treatment gap between individuals in need of specialty substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and those who actually receive it (e.g., Grant et al., 2015) was originally one of the primary promises of implementing SBIRT in community, nonspecialty care settings (e.g., Babor et al., 2006, 2007). This is stated in an influential Institute of Medicine (1990) report:

It is the view of the committee that the appropriate location for the effort directed at mild and moderate problems lies not within the specialized treatment sector but within community agencies that provide general services to various populations. The specialized treatment sector most appropriately addresses itself to substantial or severe alcohol problems; thus a collaborative effort between community agencies and the specialized treatment sector is required in order to have a significant positive impact upon the broad spectrum of alcohol problems. In this effort the role of community agencies in the treatment of alcohol problems is threefold. First, it involves the identification of individuals with alcohol problems. Second, it involves the provision of therapeutic attention in the form of brief intervention to those with mild or moderate alcohol problems. Third, it involves the referral of those with substantial or severe problems, or those for whom brief intervention does not suffice, to the specialist sector for therapeutic attention. (p. 211)

Subsequently, with widespread implementation of SBIRT programs, research has shown that SBIRT is successful in identification and brief intervention with patients with risky alcohol use levels (Babor et al., 2006, 2007; Saitz et al., 2009). This is evident in a variety of settings—emergency departments, primary care, general hospitals, etc. (Barata et al., 2017; Bruguera et al., 2018; D’Onofrio & Degutis, 2002; Estee et al., 2010; Fahy et al., 2011; Jonas et al., 2012; Kaner et al., 2009; Pringle et al., 2018; Saitz et al., 2007; Simioni et al., 2015a & 2015b).

The literature increasingly refers to Screening and Brief Intervention (SBI), the initial portion of SBIRT (Brown et al., 2014; Saitz et al., 2010). SBI has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing levels of risky alcohol use in targeted adult populations and has become an evidence-based intervention (Bertholet et al., 2005; Jonas et al., 2012; Kaner et al., 2009; Wutzke et al., 2002) for risky alcohol use. The evidence is less conclusive regarding the effectiveness of SBI for reduction of use of drugs other than alcohol, with significant positive observational study findings (Aldridge et al., 2017b; Gmel et al., 2013; Madras et al; 2008; Young et al., 2014). However, two randomized trials (Roy-Byrne et al., 2014; Saitz et al., 2014) showed no significant impact on drug use among patients in primary care settings, whereas a randomized trial reported by Forray et al. (2019) found positive results for reduction of cigarette use and illicit drugs among women.

There is also evidence that SBIRT may reduce overall health care utilization and costs in the short run (Bray et al., 2011; Estee et al., 2010; Paltzer et al., 2017, 2019; Pringle et al., 2018; Sterling et al., 2019). Estee et al. (2010) found that SBIRT was associated with decreased health care costs ($366 per member per month) among Medicaid patients receiving care in emergency departments.

Although SBI does lead to a reduction in the amount and frequency of alcohol use among risky drinkers, there is little evidence that SBIRT, as a package of three services, (a) leads to increased admissions to substance use specialty care and (b) is efficacious for individuals with severe SUDs (Glass et al., 2015; Saitz et al., 2007, 2009; Simioni et al., 2015a, 2015b). According to the Glass et al. (2015) meta-analysis, there is no evidence that high-risk drinkers increase utilization of alcohol-related specialty care as a result of SBIRT. Similar conclusions are offered by Aldridge et al. (2017a), Saitz et al. (2009), and Simioni et al. (2015a, 2015b). Recently, Frost et al. (2020) found that among Veteran's Administration patients, participation in brief intervention for alcohol use was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving specialty SUD services.

The present article is based on analysis of data originally collected for a cost offset evaluation of Wisconsin's Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-funded SBIRT trial (Brown et al., 2014; see Bray et al., 2017 re. SAMHSA's program). Known as the Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles (WIPHL), this program used paraprofessional health educators to screen patients in 31 clinical (mostly primary care) sites. WIPHL's model was to screen universally in the participating clinics, and we estimated that 68% of all eligible patients participated (Brown et al., 2014). WIPHL program evaluation data yielded 33% positive for “risky” substance use, based on a positive response to one or more of the following brief/preliminary substance use screening (Brown et al., 2001; Canagasaby & Vinson, 2005) criteria:

“binge” drinking (>4/3 drinks for men/women on at least one occasion) in the past 3 months,

used more alcohol or drugs than meant to (past year),

felt a need to cut down on alcohol or drugs (past year), and

admitted to illicit drug use (past year).

Follow-up brief intervention protocols offered to those with a positive brief screen included a brief assessment using the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; Humeniuk et al., 2008). Of those positive on the brief screen, 63% participated in the brief assessment (Brown et al., 2014). Subsequently, a motivational interview was conducted with patients with “risky” (67% of those with assessment) or “harmful” (6%) levels of substance use. Referral to specialized assessment and treatment was recommended and facilitated by a treatment liaison for patients who were likely dependent (8%, or 1,855 patients). Anecdotal reports from specialty treatment providers included complaints about the lack of successful referrals to treatment given the large numbers (N = 113,642) screened. The data collected by WIPHL were inadequate to estimate successful referral to treatment, although the final evaluation report indicated that 452 patients were documented as “referred to treatment” and 183 as “admitted” to a treatment program (Lecoanet et al., 2012).

To assess potential cost offset due to WIPHL, we obtained de-identified matched claims and health maintenance organization (HMO) encounter data for all WIPHL patients covered by Medicaid and for a sex-matched sample of Medicaid patients from comparison non-WIPHL clinics (see Paltzer et al., 2017, 2019, for additional details). At the time of our data collection, approximately 20% of the total Wisconsin population was enrolled in Medicaid. We used Medicaid data because there were a number of Medicaid patients in WIPHL clinics and Medicaid had consistent administrative data across clinics stored in a central archive maintained by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. As the primary grantee organization for the overall SAMHSA demonstration program, the Department of Health Services facilitated extraction of the data set.

In the current secondary analysis of this data set, we examined documentation of SUD diagnoses to evaluate the effect of universal SBIRT on healthcare provider recognition of SUDs. Recognition of SUDs, evidenced by documentation of a diagnosis, is a first step to obtaining appropriate services for individuals with SUDs.

Thus, we sought to answer the following question: Does participation in universal SBIRT predict post-SBIRT Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), diagnosis in Medicaid claims data of (a) alcohol abuse or dependence, (b) drug abuse or dependence, and/or (c) combined SUD? The Null Hypothesis tested is that: Individuals receiving SBIRT will have the same likelihood (or odds) of an SUD diagnosis in the 12 months following SBIRT as do individuals from comparison clinics who did not receive SBIRT.

Method

A de-identified data set was created under the oversight of the University of Wisconsin's Health Sciences Institutional Review Board to ensure that HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), data use agreements, and human subjects protection guidelines were followed in order to protect the anonymity of all patient data. Medicaid fee-for-service claims and HMO encounter data were extracted from Wisconsin's Medicaid claims data set by the state's data processing vendor and a de-identified data set linked with matched SBIRT program data was produced, following requirements established by the institutional review board. Claims and encounter (for HMO-enrolled Medicaid patients) data were provided for the year before SBIRT screening and 2 years subsequent to SBIRT screening for SBIRT clients who were documented as having Medicaid coverage. The grant covered the years 2006–2011; the bulk of the SBIRT services were provided in 2009 and 2010.

Thirty-one WIPHL clinics participated in the program. However, 11 clinics were excluded from the analysis because of low numbers (<25) of Medicaid patients, resulting in a total of 20 WIPHL sites. A set of Wisconsin clinics with similar populations and service mix that did not participate in WIPHL (SBIRT) were selected as comparison sites, and a random sample of Medicaid clients matched by sex was pulled from those clinics. In drawing the comparison sample, any patients from the WIPHL clinics were removed from the potential pool of comparison clinic patients to minimize the influence of crossover.

Forty-four non-WIPHL clinics located in Wisconsin were initially identified and matched on clinic type, size, and rurality to the WIPHL clinics with an intended 2:1 clinic match. Comparison clinics were selected from the same geographical regions as WIPHL clinics to balance population characteristics. A sex-matched sample of comparison Medicaid beneficiaries was requested from each non-WIPHL clinic. Comparison clinics with less than 25 Medicaid beneficiaries were dropped from the analysis, resulting in a total of 20 WIPHL clinics and 32 comparison clinics.

SBIRT participation was defined as a completed substance use brief screen, regardless of screening result and subsequent services. The month the screen was completed by the WIPHL participant was considered the index month and excluded from the analysis. The median index month of the SBIRT group was used as the index month for the comparison patients to determine baseline and follow-up periods concordant with the SBIRT services.

Comparison beneficiaries must have received services at one of the pre-selected clinics and be between 18 and 64 years of age during the study period. SBIRT and comparison beneficiaries who had at least 1 month of Medicaid coverage in each 12-month period (baseline: months 1–12; follow-up: months 14–25 and 26–37) were included in the analytic data set. Only the baseline and 1-year follow-up (months 14–25) periods were used in this analysis. The total study sample was 14,856 working-age Medicaid beneficiaries (treatment n = 7,192; comparison n = 7,644) clustered in a total of 20 WIPHL and 32 non-WIPHL clinic units.

The effects of SBIRT on the likelihood of being diagnosed with DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence in the 12 months following receipt of an SBIRT screen were analyzed. The three outcomes analyzed were alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis (ICD-9 codes: 303.0, 303.9, 305.0), drug abuse or dependence diagnosis (ICD-9 codes: 305.3-305.9, 304.*), and combined alcohol or drug abuse or dependence diagnosis. Hierarchical generalized linear models (GLMs) were estimated, with the clinic from which the individual was identified as the random effect variable. The models were specified with the Bernoulli family, logit link, and robust standard errors. Fixed effects covariates in the model were as follows: SBIRT participant (primary independent variable), age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years), sex, race/ethnicity, supplemental security income (SSI) status at baseline, heart disease diagnosis at baseline, diabetes diagnosis at baseline, hypertension diagnosis at baseline, substance abuse/dependence (DSM-IV) diagnosis pre-existing at baseline, any healthcare utilization at baseline, mental health diagnosis at baseline, tobacco diagnosis at baseline, months of Medicaid eligibility in the 12 months after SBIRT (89% were eligible all 12 months), and Sex × Pregnancy (interaction term).

An alternative model was estimated using a mixed effects logit model assessing whether, among those patients with no pre-existing alcohol or drug use diagnosis at baseline, there was a new SUD diagnosis occurring during the 1 year after the SBIRT index month. In keeping with Frost et al. (2020), the same model was run to assess continuation of preexisting SUD diagnoses. We also estimated the raw number of new SUD diagnoses resulting from the SBIRT screen and the number of cases where there was a coded SUD specialty treatment in the 12 months subsequent to SBIRT.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the SBIRT and comparison samples are provided in Table 1. Relatively small but significant differences between groups were noted for several variables, which were subsequently controlled for in the analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Variable | SBIRT (n = 7,192) | Comparison (n = 7,664) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion female | 0.76 | 0.72 | *** |

| Age, M (SD) | 36.1 (12.0) | 37.8(11.5) | *** |

| % White | 38.8 | 57.6 | *** |

| % Black | 43.8 | 25.4 | *** |

| % Other | 6.3 | 8.1 | |

| % Missing race | 11.1 | 9.0 | *** |

| Proportion alcohol-related | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.06 | 0.05 | .001 |

| Proportion drug-related | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.08 | 0.05 | *** |

| Proportion mental health | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.45 | 0.43 | .017 |

| Proportion tobacco | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.19 | 0.17 | .001 |

| Proportion hypertension | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.21 | 0.20 | .176 |

| Proportion diabetes | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.10 | 0.10 | .099 |

| Proportion heart disease | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.05 | 0.05 | .546 |

| Proportion COPD | |||

| diagnosis-baseline | 0.05 | 0.06 | .043 |

| Proportion SSI eligible | 0.30 | 0.29 | .222 |

| Outpatient days (pmpm), M (SD) | 1.48 (2.67) | 1.34(2.28) | .002 |

| Inpatient days (pmpm), M (SD) | 0.13 (0.84) | 0.13 (1.19) | .955 |

| Inpatient admissions (pmpm), M (SD) | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.07) | .016 |

| ED admissions (pmpm), M (SD) | 0.13 (0.28) | 0.09 (0.21) | *** |

| Medicaid eligibility, months (SD) | 10.7 (2.8) | 10.5 (2.9) | .005 |

Notes: Statistics are unadjusted. Health status indicators identified using ICD-9 codes. ED = emergency department; SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; SSI = Supplemental Security Income; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; pmpm = per member per month.

p < .001.

Hierarchical GLMs indicate that SBIRT was associated with significantly greater odds of being diagnosed with alcohol or drug use disorders during the 12 months following SBIRT, when we controlled for demographic and prior-year health characteristics. When we controlled for baseline diagnosis and other variables, SBIRT was associated with 44% (odds ratio [OR] = 1.44, p = .004) greater odds of being diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder (Table 2). We also found 31% (OR = 1.31, p = .002) greater odds of diagnosis with a drug use disorder (Table 3) relative to those in the comparison clinics (where SBIRT was not implemented).

Table 2.

Effect of SBIRT on subsequent alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence) diagnosis in Medicaid claims during 1 year following SBIRT screening (n = 13,370)*

| Variable | Exp (B) | SE | p | [95% CI], Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBIRT | 1.437 | .179 | .004 | [1.126, 1.835] |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | |||

| 25-34 | 1.246 | .166 | .098 | [0.960, 1.618] |

| 35-44 | 1.533 | .235 | .005 | [1.135, 2.072] |

| 45-54 | 2.111 | .341 | .000 | [1.538, 2.900] |

| 55-64 | 1.352 | .218 | .062 | [0.985, 1.856] |

| Female | 0.512 | .045 | .000 | [0.431, 0.610] |

| Race | ||||

| White (including Hispanic) | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.741 | .077 | .004 | [0.605, 0.907] |

| Other | 1.581 | .284 | .011 | [1.112, 2.247] |

| Alcohol or drug use diagnosis-baseline | 7.578 | .714 | .000 | [6.299, 9.115] |

| Mental health diagnosis-baseline | 1.277 | .132 | .018 | [1.043, 1.565] |

| Tobacco use diagnosis-baseline | 1.130 | .121 | .254 | [0.916, 1.394] |

Notes: Result of hierarchical generalized linear model. Additional covariates were clinic, months of Medicaid eligibility at baseline, baseline Medicaid utilization, Supplemental Security Income status, chronic disease diagnoses, and Pregnancy by Sex interaction. SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3.

Effect of SBIRT on subsequent drug use disorder (DSM-IV drug abuse or dependence) diagnosis in Medicaid claims during 1 year following SBIRT screening (n = 13,370)*

| Variable | Exp (B) | SE | p | [95% CI], Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBIRT | 1.310 | .113 | .002 | [1.105, 1.552] |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | |||

| 25-34 | 0.941 | .087 | .513 | [0.784, 1.129] |

| 35-44 | 0.852 | .099 | .169 | [0.678, 1.070] |

| 45-54 | 0.874 | .120 | .326 | [0.667, 1.144] |

| 55-64 | 0.509 | .110 | .002 | [0.333, 0.778] |

| Female | 0.787 | .076 | .014 | [0.651, 0.952] |

| Race | ||||

| White (including Hispanic) | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.790 | .080 | .020 | [0.648, 0.964] |

| Other | 0.751 | .109 | .048 | [0.565, 0.998] |

| Alcohol or drug use diagnosis-baseline | 8.327 | .880 | .000 | [6.769, 10.242] |

| Mental health diagnosis-baseline | 2.194 | .249 | .000 | [1.757, 2.741] |

| Tobacco use diagnosis-baseline | 1.267 | .107 | .005 | [1.072, 1.496] |

Notes: Result of hierarchical generalized linear model. Additional covariates were clinic, months of Medicaid eligibility at baseline, baseline Medicaid utilization, Supplemental Security Income status, chronic disease diagnoses, and Pregnancy by Sex interaction. SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CI = confidence interval.

The combined model showed 42% (p = .001) greater odds of being diagnosed with any SUD (DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence) among those who had received SBIRT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of SBIRT on subsequent substance use disorder diagnosis (alcohol or drug) in Medicaid claims during 1 year following SBIRT screening (n = 13,370)*

| Variable | Exp (B) | SE | p | [95% CI], Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBIRT | 1.420 | .155 | .001 | [1.146, 1.760] |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | |||

| 25-34 | 1.054 | .100 | .580 | [0.875, 1.270] |

| 35-44 | 1.186 | .113 | .073 | [0.984, 1.429] |

| 45-54 | 1.385 | .153 | .003 | [1.116, 1.719] |

| 55-64 | 0.847 | .114 | .220 | [0.650, 1.104] |

| Female | 0.642 | .044 | .000 | [0.561, 0.733] |

| Race | ||||

| White (including Hispanic) | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.737 | .073 | .002 | [0.606, 0.896] |

| Other | 1.099 | .182 | .566 | [0.795, 1.521] |

| Alcohol or drug use diagnosis-baseline | 9.662 | .982 | .000 | [7.916, 11.792] |

| Mental health diagnosis-baseline | 1.745 | .140 | .000 | [1.490, 2.043] |

| Tobacco use diagnosis-baseline | 1.233 | .092 | .005 | [1.065, 1.428] |

Notes:Result of hierarchical generalized linear model. Additional covariates were clinic, months of Medicaid eligibility at baseline, baseline Medicaid utilization, Supplemental Security Income status, chronic disease diagnoses, and Pregnancy by Sex interaction. SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; CI = confidence interval.

The covariates in these models are of substantive interest. Pre-existing (baseline) diagnoses of alcohol or drug use disorders were the strongest predictor of a subsequent diagnosis during the follow-up year. Diagnosis of SUDs after SBIRT increased with patient age for alcohol but decreased with age for other drugs, was lower for Black than White patients, and was significantly lower among females. Those with a diagnosed mental health disorder and those with a tobacco diagnosis at baseline were more likely to have a subsequent SUD diagnosis. Other chronic health conditions did not affect the likelihood of an SUD diagnosis.

An alternative analysis (Table 5) examined only those patients who did not have an existing SUD in their claims data at the baseline index date. The results confirm the impact of SBIRT in generating new SUD diagnoses (OR = 1.46, p = .003). In this model, which excludes all cases with an existing SUD diagnosis, SBIRT increased the chance of a new diagnosis by 46%, when the other variables in the model were controlled for.

Table 5.

Effect of SBIRT on subsequent alcohol or drug diagnosis in Medicaid claims during 1 year following SBIRT screening among those without substance use disorder diagnosis at baseline (n = 12,120)*

| Variable | Exp (B) | SE | p | [95% CI], Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBIRT | 1.461 | .189 | .003 | [1.134, 1.884] |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | |||

| 25-34 | 0.948 | .091 | .577 | [0.785, 1.145] |

| 35-44 | 1.139 | .121 | .221 | [0.925, 1.402] |

| 45-54 | 1.389 | .181 | .012 | [1.076, 1.793] |

| 55-64 | 0.697 | .126 | .046 | [0.489, 0.994] |

| Female | 0.537 | .043 | .000 | [0.459, 0.627] |

| Race | ||||

| White (including Hispanic) | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.856 | .102 | .192 | [0.677, 1.082] |

| Other | 1.304 | .248 | .162 | [0.899, 1.892] |

| Mental health diagnosis-baseline | 1.729 | .141 | .000 | [1.472, 2.029] |

| Tobacco use diagnosis-baseline | 1.328 | .122 | .002 | [1.108, 1.591] |

Notes: Result of hierarchical generalized linear model. Additional covariates were clinic, months of Medicaid eligibility at baseline, baseline Medicaid utilization, Supplemental Security Income status, chronic disease diagnoses, and Pregnancy by Sex interaction. SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; CI = confidence interval.

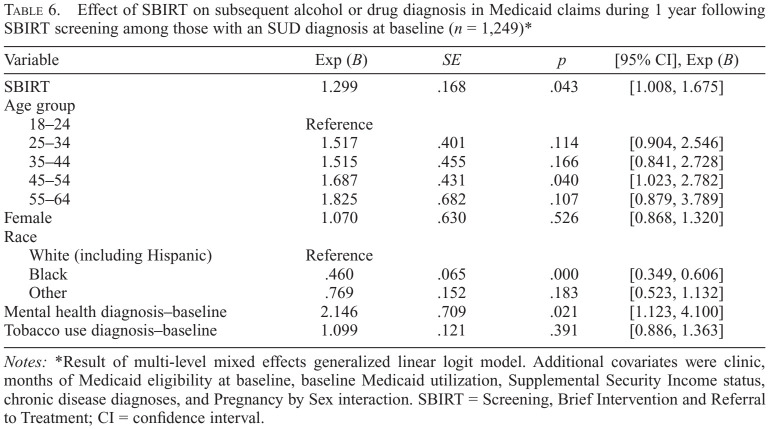

Using the same model, we also assessed the likelihood of continuation of an existing SUD diagnosis (Table 6). Among the 1,249 patients with a prior (past-year) SUD diagnosis, those in SBIRT clinics were significantly more likely than those in comparison clinics to have a subsequent/continued SUD diagnosis (OR = 1.30, p = .04).

Table 6.

Effect of SBIRT on subsequent alcohol or drug diagnosis in Medicaid claims during 1 year following SBIRT screening among those with an SUD diagnosis at baseline (n = 1,249)*

| Variable | Exp (B) | SE | p | [95% CI], Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBIRT | 1.299 | .168 | .043 | [1.008, 1.675] |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | |||

| 25-34 | 1.517 | .401 | .114 | [0.904, 2.546] |

| 35-44 | 1.515 | .455 | .166 | [0.841, 2.728] |

| 45-54 | 1.687 | .431 | .040 | [1.023, 2.782] |

| 55-64 | 1.825 | .682 | .107 | [0.879, 3.789] |

| Female | 1.070 | .630 | .526 | [0.868, 1.320] |

| Race | ||||

| White (including Hispanic) | Reference | |||

| Black | .460 | .065 | .000 | [0.677, 1.082] |

| Other | .769 | .152 | .183 | [0.523, 1.132] |

| Mental health diagnosis-baseline | 2.146 | .709 | .021 | [1.123, 4.100] |

| Tobacco use diagnosis-baseline | 1.099 | .121 | .391 | [0.886, 1.363] |

Notes: Result of multi-level mixed effects generalized linear logit model. Additional covariates were clinic, months of Medicaid eligibility at baseline, baseline Medicaid utilization, Supplemental Security Income status, chronic disease diagnoses, and Pregnancy by Sex interaction. SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment; CI = confidence interval.

We calculated cross-tabulations of the relationship between positive SBIRT screening and new diagnoses of SUDs. These results indicated that of 2,719 positively screened SBIRT cases (37.8% of 7,192 total SBIRT cases), 18% already had an SUD diagnosis in their Medicaid records at baseline; an additional 113 cases were documented with a new SUD within the following year, bringing the total to 22% of those who screened positive.

When we first conceptualized this study, we planned to test whether there was an increase in documented receipt of specialty SUD treatment as a result of SBIRT. Examination of overall frequencies in the data set precluded this—at baseline only 71 (0.5%) cases and at 12 months only 88 (0.6%) patients (of 14,856) had a claim coded for specialty SUD treatment in their Medicaid claims data. Among the 1,475 patients (10.0% of our total sample) with an SUD diagnosis at baseline, only 70 (4.8% of those with a diagnosis) had procedure codes specifically for substance use specialty treatment in their records.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that SBIRT does significantly increase the recognition of SUDs in clinical settings, as documented by diagnostic codes in Medicaid claims and HMO encounter data. Comparing Medicaid-insured patients in clinics with universal SBIRT to similar patients in comparison clinics without SBIRT, the odds of any SUD diagnosis being entered into Medicaid claims or HMO encounter data during the year subsequent to SBIRT services were 42% greater. This finding is consistent for both new and continued SUD diagnoses. Although the difference in odds is substantial and significant at p = .001, the actual number of cases this represents is modest, with only 113 new SUD cases (in an SBIRT population of 7,192 patients) documented via a diagnosis. Notably, this is likely a conservative estimate given that, following Estee et al. (2010), data from the month of SBIRT participation were (irretrievably) excluded from the data set for the original cost-offset analysis (Paltzer et al., 2019).

Since provision of health care services generally follows diagnosis, we expected to see an increase in procedure or service codes for SUD specialty services. In general, providers do not code diagnoses unless they are needed to justify a claim for services. However, this was not apparent in the data set, where only 4.8% of the patients with an SUD diagnosis in their records had a code for corresponding specialty SUD treatment.

Further research is needed to better understand these findings. Alternative hypotheses for further study regarding the minimal coding for SUD specialty services in spite of documented diagnoses include the possibility that SUD treatment is increasingly integrated in primary care for Medicaid patients (Aletraris et al., 2017; Padwa et al., 2012). A strong argument for integration of behavioral health services within and beyond primary health care is made by Willenbring (2020) in his commentary on Frost et al. (2020).

There may also be a preference for assigning mental health diagnoses and treatment over coding for SUD. Our analyses show a strong relationship between existing mental health diagnoses and subsequent substance use diagnoses. Krupski et al. (2012) found that mental health status influences SBIRT outcomes. Notably, nearly half of the Medicaid patients in our sample have pre-existing mental health diagnoses. Integrated treatment could in these cases be coded as a mental health rather than an SUD service, masking the initiation of specialty SUD treatment.

When these data were collected, the Wisconsin Medicaid program covered services for mental health and SUD treatment without differentiating the type of behavioral health condition, so there was no financial advantage to providers to select a mental health services coding over substance use specialty codes. However, to the extent that mental health and substance use services were integrated, there could be a professional bias toward coding for mental health services. Further, public sector services for residential treatment and much of the specialty day treatment and outpatient care in Wisconsin were (and continue to be) reimbursed using federal block grant allocations to county agencies. Medicaid covered behavioral health care under medical supervision, outpatient and day treatment, but no residential services. Thus, a great deal of treatment for SUDs likely occurred outside of the Medicaid system.

In a study of Veterans Administration (VA) patients, Harris et al. (2009, p. 191) found that “25% of initiation and 40% of engagement occurred outside of SUD specialty care.” As in the VA system, treatment for SUDs among Medicaid patients may often occur outside of SUD specialty settings. WIPHL patients may have participated in SUD services integrated with and coded as mental health services or in services outside the auspices of the Medicaid program, such as 12-step self-help programs, privately funded services, clergy counseling, or public programs covered by other funding streams such as block grant funding (Kepple et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2003).

Another explanation of our results is that there may be greater recognition and documentation of SUDs but a failure to treat in this population. Glass et al. (2015) provide some discussion on this—suggesting that SBI is implemented in settings with lower rates of individuals with SUDs and providers in these settings tend to see individuals with risky substance use who are not dependent on alcohol or other drugs. Glass et al. also discuss the reality that many SBIRT studies are not designed to measure success of treatment referral. Studies in large integrated health care settings are able to better track specialty care initiation. Several of these studies have found that behavioral health clinician screening can significantly increase initiation of specialty treatment for adolescents (Sterling et al., 2017) and adults (Harris et al., 2009; Krupski et al., 2010; Yarborough et al., 2018). However, the recent VA study by Frost et al. (2020) failed to find a treatment initiation effect of brief intervention. Notably, this study did not consider services outside of the VA system (see Harris et al., 2009), but, similar to our study, did find higher specialty care utilization for patients without a previous documented alcohol use disorder (Frost et al., 2020).

A failure to treat could be related to patient refusal to accept treatment recommendations (McLellan, 2004), as well as systemic issues that may impede treatment entry. These include a failure to consider patient-centered care, difficulties in hand-offs, limited availability, waiting list impediments, strict eligibility criteria, lack of providers, and policy limitations on the use of Medicaid funds (Davis et al., 2020; Lecoanet et al., 2014).

Limitations of this research, beyond its quasi-experimental nature, include reliance on coding in claims and encounter data. These administrative data reflect only services provided under the auspices of the Medicaid program, and only the diagnostic codes that the providers chose to include in a claim. Specific information on the content of a clinical encounter is lacking. A timeliness limitation is that Wisconsin Medicaid reimbursement rates and policies have changed since these data were collected, including the addition of coding and reimbursement for SBIRT screening and increased specificity of diagnostic and procedure coding.

As a result, specific policy for mental health versus substance use treatment has been developed. On the other hand, there has been further development of county-administered psycho-social rehabilitation services partially funded by Medicaid for dually diagnosed patients. For these services, the distinction between mental health and SUD services is blurred because of the use of a single billing code across a range of 14 integrated services. Another limitation is that the generalizability of our findings may be limited to Medicaid patients in Wisconsin and to the WIPHL model of universal SBIRT implementation using paraprofessional health educators as the primary staff. Clinics self-selected into SBIRT and may have differed in unknown and unadjusted ways from the comparison clinics. The higher proportion of Black patients in the SBIRT sample than the comparison sample possibly reflects clinic selection into WIPHL or bias within clinics of who was screened, in spite of the universal screening intent of WIPHL. Finally, the discussion of covariates should be considered speculative and interpretive, since we did not adjust for the multiple comparisons; the findings based on the covariates are incidental to the main focus of the analysis.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size and a pragmatic real-world (rather than research) implementation of a replicable and sustainable SBIRT model. We included an entire population, rather than relying on data only from individuals consenting to research involvement. Our focus on diagnostic outcomes provides an intermediary way to examine the potential referral to treatment effectiveness of SBIRT. The results we report are likely conservative, since claims data from the specific month of the SBIRT encounter were not included in the outcome assessment period.

These results suggest that SBIRT does have the potential to increase referral to treatment in the Medicaid setting, at least to the extent of a significant increase in documented SUD diagnoses in claims and encounter data subsequent to SBIRT screening. Further examination of the link between documented diagnostic coding and actual involvement of patients in some form of SUD treatment is needed to understand the natural process by which assignment of a diagnosis may lead to relevant services. These data, as well as results from Sterling et al. (2017), Yarborough et al. (2018), and Harris et al. (2009), suggest that it may be premature to abandon the “RT” component of SBIRT, as the literature increasingly is doing, as the field moves toward the concept of SBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors particularly thank Joyce Allen and Richard L. Brown for their leadership of the WIPHL program, and Marguerite Burns for her advice regarding analysis of Medicaid data. We also acknowledge the assistance of Pam Lano and the staff of the Behavioral Health Policy Section of the Wisconsin Division of Medicaid Services in clarifying Medicaid policies and services.

Footnotes

The research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Award Number R03 AA025196. The data were collected under Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Grant UT79 TI018309. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aldridge A., Dowd W., Bray J. The relative impact of brief treatment versus brief intervention in primary health-care screening programs for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2017a;112(Supplement 2):54–64. doi: 10.1111/add.13653. doi:10.1111/add.13653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge A., Linford R., Bray J. Substance use outcomes of patients served by a large US implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Addiction. 2017b;112(Supplement 2):43–53. doi: 10.1111/add.13651. doi:10.1111/add.13651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletraris L., Roman P. M., Pruett J. Integration of care in the implementation of the Affordable Care Act: Changes in treatment services in a national sample of centers treating substance use disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49:132–140. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2017.1299263. doi:10.1080/02791072.2017.1299263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T. F., Higgins-Biddle J. C., Dauser D., Burleson J. A., Zarkin G. A., Bray J. Brief interventions for at-risk drinking: Patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness in managed care organizations. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41:624–631. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl078. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T. F., McRee B. G., Kassebaum P. A., Grimaldi P. L., Ahmed K., Bray J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): Toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Substance Abuse. 2007;28:7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. doi:10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barata I. A., Shandro J. R., Montgomery M., Polansky R., Sachs C. J., Duber H. C., Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Effectiveness of SBIRT for alcohol use disorders in the emergency department: A systematic review. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;18:1143–1152. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.7.34373. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.7.34373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N., Daeppen J.B., Weitlisbach V., Fleming M., Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:986–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J., Cowell A., Hinde J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of health care utilization outcomes in alcohol screening and brief intervention trials. Medical Care. 2011;49:287. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318203624f. doi:10.1097/mlr.0b013e318203624f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. W., Del Boca F.K., McRee B. G., Hayashi S. W., Babor T. F. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): Rationale, program overview and cross-site evaluation. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 2):3–11. doi: 10.1111/add.13676. doi:10.1111/add.13676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. L., Leonard T., Saunders L. A., Papasouliotis O. A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2001;14:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. L., Moberg D. P., Allen J., Peterson C. T., Saunders L. A., Croyle M. D., Caldwell S. B. A team approach to systematic behavioral screening and intervention. American Journal of Managed Care. 2014;20:e113–e121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruguera P., Barrio P., Oliveras C., Braddick F., Gavotti C., Bruguera C., Gual A. Effectiveness of a specialized brief intervention for at-risk drinkers in an emergency department: Short-term results of a randomized controlled trial. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018;25:517–525. doi: 10.1111/acem.13384. doi:10.1111/acem.13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canagasaby A., Vinson D. C. Screening for hazardous or harmful drinking using one or two quantity-frequency questions. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2005;40:208–213. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh156. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E. L., Kelly P. J., Deane F. P., Baker A. L., Buckingham M., Degan T., Adams S. The relationship between patient-centered care and outcomes in specialist drug and alcohol treatment: A systematic literature review. Substance Abuse. 2020;41:216–231. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1671940. doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1671940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G., Degutis L. C. Preventive care in the emergency department: Screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems in the emergency department: A systematic review. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002;9:627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02304.x. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estee S., Wickizer T., He L., Shah M. F., Mancuso D. Evaluation of the Washington state Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment project: Cost outcomes for Medicaid patients screened in hospital emergency departments. Medical Care. 2010;48:18–24. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd498f. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd498f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy P., Croton G., Voogt S. Embedding routine alcohol screening and brief interventions in a rural general hospital. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00195.x. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forray A., Martino S., Gilstad-Hayden K., Kershaw T., Ondersma S. J., Olmstead T. A., Yonkers K. A. Assessment of an electronic and clinician-delivered brief intervention on cigarette, alcohol and illicit drug use among women in a reproductive healthcare clinic. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;96:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost M. C., Glass J. E., Bradley K. A., Williams E. A. Documented brief intervention associated with reduced linkage to specialty addictions treatment in a national sample of VA patients with unhealthy alcohol use with and without alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2020;115:668–678. doi: 10.1111/add.14836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J. E., Hamilton A. M., Powell B. J., Perron B. E., Brown R. T., Ilgen M. A. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2015;110:1404–1415. doi: 10.1111/add.12950. doi:10.1111/add.12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G., Gaume J., Bertholet N., Flückiger J., Daeppen J. B. Effectiveness of a brief integrative multiple substance use intervention among young men with and without booster sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Saha T. D., Chou S. P., Jung J., Zhang H., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. H., Bowe T., Finney J. W., Humphreys K. HEDIS initiation and engagement quality measures of substance use disorder care: Impact of setting and health care specialty. Population Health Management. 2009;12:191–196. doi: 10.1089/pop.2008.0028. doi:10.1089/pop.2008.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R., Ali R., Babor T. F., Farrell M., Formigoni M. L., Jittiwutikarn J., Simon S. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1990. Broadening the base of treatment for alcohol problems. doi:10.17226/1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas D. E., Garbutt J. C., Amick H. R., Brown J. M., Brown-ley K. A., Council C. L., Harris R. P. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157:645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner E. F., Dickinson H. O., Beyer F., Pienaar E., Schlesinger C., Campbell F., Heather N. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:301–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepple N. J., Parker A., Whitmore S., Comtois M. Nowhere to go? Examining facility acceptance levels for serving individuals using medications for opioid used disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;104:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.004. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski A., Sears J. M., Joesch J. M., Estee S., He L., Dunn C., Ries R. Impact of brief interventions and brief treatment on admissions to chemical dependency treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.018. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski A., Sears J. M., Joesch J. M., Estee S., He L., Huber A., Ries R. Self-reported alcohol and drug use six months after brief intervention: Do changes in reported use vary by mental-health status? Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2012;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-24. doi:10.1186/1940-0640-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecoanet R., Linnan S., Moberg D. P. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2012. Screening, brief intervention and referral to Treatment: Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles; Final program evaluation of the implementation and operation of WIPHL in Wisconsin clinical settings. Retrieved from https://uwmadison.app.box.com/s/hnh9ejjqr61o5biuy7akmk6×9actnhl8. [Google Scholar]

- Madras B. K., Compton W. M., Avula D., Stegbauer T., Stein J. B., Clark H. W. Screening, Brief Interventions, Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: Comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;99:280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: A review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;15:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwa H., Urada D., Antonini V. P., Ober A., Crevecoeur-MacPhail D. A., Rawson R. A. Integrating substance use disorder services with primary care: The experience in California. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44:299–306. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.718643. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.718643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltzer J., Brown R. L., Burns M., Moberg D. P., Mullahy J., Sethi A. K., Weimer D. Substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment among Medicaid patients in Wisconsin: Impacts on healthcare utilization and costs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2017;44:102–112. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9510-2. doi:10.1007/s11414-016-9510-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltzer J., Moberg D. P., Burns M., Brown R. L. Health care utilization after paraprofessional-administered substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment: A multilevel cost-offset analysis. Medical Care. 2019;57:673–679. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001162. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle J. L., Kelley D. K., Kearney S. M., Aldridge A., Dowd W., Johnjulio W., Lovelace J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment in the emergency department: An examination of health care utilization and costs. Medical Care. 2018;56:146–152. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000859. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P., Bumgardner K., Krupski A., Dunn C., Ries R., Donovan D., Zarkin G. A. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:492–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7860. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R., Alford D. P., Bernstein J., Cheng D. M., Samet J., Palfai T. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: Randomized clinical trials are needed. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2010;4:123–130. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181db6b67. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181db6b67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R., Palfai T. P., Cheng D. M., Alford D. P., Bernstein J. A., Lloyd-Travaglini C. A., Samet J. H. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: The ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R., Palfai T. P., Cheng D. M., Horton N. J., Dukes K., Kraemer K. L., Samet J. H. Some medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use may benefit from brief intervention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:426–435. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.426. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R., Palfai T. P., Cheng D. M., Horton N. J., Freedner N., Dukes K., Samet J. H. Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146:167–176. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simioni N., Cottencin O., Rolland B. Interventions for increasing subsequent alcohol treatment utilisation among patients with alcohol use disorders from somatic inpatient settings: A systematic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015a;50:420–429. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv017. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simioni N., Rolland B., Cottencin O. Interventions for increasing alcohol treatment utilization among patients with alcohol use disorders from emergency departments: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015b;58:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S., Kline-Simon A. H., Jones A., Hartman L., Saba K., Weisner C., Parthasarathy S. Health care use over 3 years after adolescent SBIRT. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20182803. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2803. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S., Kline-Simon A. H., Jones A., Satre D. D., Parthasarathy S., Weisner C. Specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment initiation and engagement: Results from an SBIRT randomized trial in pediatrics. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2017;82:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. S., Berglund P. A., Kessler R. C. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research. 2003;38:647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring M. Commentary on Frost et al. The end of SBIRT and a new continuum of care. Addiction. 2020;2020;115:679–680. doi: 10.1111/add.14960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutzke S. E., Conigrave K. M., Saunders J. B., Hall W. D. The long-term effectiveness of brief interventions for unsafe alcohol consumption: A 10-year follow-up. Addiction. 2002;97:665–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00080.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough B., Chi F. W., Green C. A., Hinman A., Mertens J., Beck A., Campbell C. I. Patient and system characteristics associated with performance on the HEDIS measures of alcohol and other drug treatment initiation and engagement. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12:278–286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000399. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. M., Stevens A., Galipeau J., Pirie T., Garritty C., Singh K., Moher D. Effectiveness of brief interventions as part of the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model for reducing the nonmedical use of psychoactive substances: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2014;3:50. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-50. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]