Abstract

Objective:

In this study, we aimed to inform clinical practice by identifying distinct subgroups of U.S. veteran psychiatry inpatients on their alcohol and drug use severity, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and suicidal ideation over time.

Method:

Participants were 406 patients with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. A parallel latent growth trajectory model was used to characterize participants’ symptom severity across 15 months posttreatment intake.

Results:

Four distinct classes were identified: 47% “normative improvement,” 32% “high PTSD,” 11% “high drug use,” and 9% “high alcohol use.” Eighty percent of the sample had reduced their drinking and drug intake by half from baseline to 3 months, and those levels remained stable from 3 to 15 months. The High PTSD, High Drug Use, and High Alcohol Use classes all reported levels of PTSD symptomatology at baseline consistent with a clinical diagnosis, and symptom levels remained high and stable across all 15 months. The Normative Improvement class showed declining drug and alcohol intake and was the only class exhibiting reductions in PTSD symptomatology over time. High substance use classes showed initial declines in suicidal ideation, then an increase from 9 to 15 months.

Conclusions:

The reduction in frequency of drinking and drug use for 80% of the sample was substantial and supports the potential efficacy of current treatment approaches. However, the high and stable levels of PTSD for more than 50% of the sample, as well as the reemergence of suicidal ideation in a sizable subgroup, underscore the difficulty in finding and linking patients to effective interventions to decrease symptomatology over time.

Co-occurring substance use disorders (SUDs) and mental health disorders (MHDs) are evident among more than 9 million people in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020) and incur high healthcare costs (Painter et al., 2018; Whiteford et al., 2013). When these patients enter treatment, they often report more severe symptoms, longer stays, and poorer clinical outcomes than those with either condition alone (Jané-Llopis & Matytsina, 2006; Kranzler & Rosenthal, 2003; Rosenthal, 2003). To inform treatment services in this population, we aimed to examine change processes that characterized patients’ longitudinal substance use and mental health symptoms after a psychiatric hospital stay.

Co-occurring SUD-MHD is prevalent among veterans (Debell et al., 2014; Dworkin et al., 2018; Teeters et al., 2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is of particular concern because it is one of the most common postdeployment MHDs and is associated with many deleterious health conditions (Magruder et al., 2004) including SUD and risk for suicide (Marvasti & Wank, 2013). For example, 8.0% of veterans met criteria for PTSD (vs. 6.4% among the general population), and those with probable lifetime PTSD were approximately three times more likely than veterans without PTSD to have an SUD, and approximately 10 times more likely to have current suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] = 9.7) and a history of suicide attempt (OR = 11.8; Wisco et al., 2014). A study of four Veterans Health Administration patient groups—SUD only, co-occurring PTSD-SUD, cooccurring other Axis 1 disorder-SUD, and co-occurring other Axis 1 disorder-PTSD-SUD—found that the group with three co-occurring conditions had more severe psychiatric and life problems and more lifetime suicide attempts (Cac ciola et al., 2009). These findings point to the importance of studying PTSD and SUD in combination, and further, understanding how these co-occurring conditions may be related to suicidal ideation over time. These patterns are particularly salient during the period following inpatient psychiatric treatment because of the consistent finding that postinpatient discharge is a period of very high risk for suicidal behaviors in veterans (Britton et al., 2015; Valenstein et al., 2009).

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use an advanced modeling approach to examine the association among alcohol and drug consumption, PTSD symptomatology, and suicidal ideation patterns in veterans during the high-risk period following an episode of inpatient psychiatric treatment. It applies a person-centered modeling technique to determine latent classes of patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric treatment with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. Specifically, this study uses parallel growth mixture modeling to simultaneously assess the extent of daily alcohol and drug use, PTSD symptoms, and suicidal ideation trajectories after hospitalization. It makes a significant contribution to the literature by revealing latent (unobserved) patterns in longitudinal data to identify subgroups within this co-occurring SUD and MHD population and inform treatment approaches. Nearly a quarter of veterans with co-occurring SUD-MHD who received inpatient psychiatric care in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) were readmitted for additional psychiatric care within 90 days of discharge (Ilgen et al., 2008) with similar findings outside VA facilities (Mark et al., 2013; Reif et al., 2017). Thus, these findings have import for how inpatient psychiatric treatment services can best address the mental health treatment needs of patients with comorbid SUD and MHD to prevent psychiatric readmissions.

Method

Participants

Participants were 406 Veterans Health Administration patients with co-occurring SUD and MHD (i.e., had a diagnosis for both conditions documented in their medical record) entering inpatient psychiatric treatment. The longitudinal design assessed participants at baseline (intake to inpatient psychiatric unit) and 3, 9, and 15 months later (see Timko et al., 2019). The parent study in which patients were recruited sought generalizability to “real world” inpatient psychiatric settings in which patients have multiple disorders and complex clinical conditions. To qualify for study inclusion, participants had to (a) be diagnosed with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, specifically, have both a substance use (alcohol and/or drug use disorder) and at least one non–substance use mental health disorder diagnosis; (b) sufficiently understand study procedures; and (c) have access to a telephone for follow-up. The modal length of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization was 7 days (interquartile range: 5–13 days). Study protocols were Institutional Review Board compliant.

Procedures

Case managers screened patients in consecutive order for eligibility. After receiving a study introduction, participants signed an informed consent form and completed the baseline interview; this procedure took place within 3 days of admission. Trained research assistants, blinded to participants’ condition assignment, collected self-report data. Participants received $25 for each completed assessment.

Participants were recruited from an inpatient psychiatric treatment program at one of two health care facilities within the same health care system. Patients were provided a multidisciplinary assessment by the third day of admission. Treatment used a biopsychosocial approach that involved stabilization. In addition to the comprehensive assessment, participants received psychopharmacology, individual and group psychotherapy, and other behavioral interventions. In addition, each participant had a daily meeting with the treatment team to evaluate progress, address concerns, and review the treatment plan. As part of discharge planning, all patients were referred to follow-up care. However, only 54% to 65% of participants reported attending any outpatient mental health care at follow-ups.

Measures

Baseline demographic characteristics were measured using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 2006). At baseline and each follow-up, the Timeline Follow-back procedure (Sobell et al., 1996) assessed the number of days the participant drank alcohol or ingested drugs in the past 90 days. The number of days drinking was extrapolated into percent days drinking. PTSD symptoms were measured using the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Weathers et al., 1993). The PCL has 17 items scored on a 1 to 5 scale and summed for a total score ranging from 17 to 85. Suicidal ideation was measured using the Sheehan Suicide Tracking Scale (STS; Coric et al., 2009), which contains eight items, each scored 0 to 4, providing a 0 to 32 severity score (higher scores indicate higher severity) when summed.

Data analyses

Demographic information and class probabilities were computed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The parallel latent class trajectory analyses and baseline covariate predictor analyses were computed in Mplus (Jung & Wickrama, 2008; Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The original trial was a prospective randomized trial to examine a telephone monitoring intervention compared to usual care. Because participants in both study conditions improved equally across time, data were collapsed across conditions. The statistical analyses consisted of three steps. First, we used latent class trajectory analysis to identify classes of participants with similar responding trajectories on PTSD, suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and drug use across the 15 months. In the second step, we used the data-derived latent classes to determine baseline characteristics of each class. In the third step, we used the R3STEP technique to examine significant differences between classes on baseline characteristics (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). Missing data were handled with a maximum likelihood estimator (MLR), robust to nonnormality in the data.

We tested successive models with up to six classes and determined the most parsimonious model. Linear and nonlinear models were evaluated. All of the variances in the model were set to zero. As each class was added to the model, we examined the intercepts and slopes, as well as the quadratic and cubic equations. If any of these outcomes were nonsignificant, we set them to zero and re-ran the revised models until the nonsignificant parameters were eliminated. We relied on multiple fit indices to guide our selection of optimal fit. As explained in Nagin (1999, 2014), global fit indices included the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), entropy, average class membership probability, percent of participants in each class, and the Lo–Mendell–Rubin test (LMR; Lo et al., 2001). Entropy and class membership probabilities range from 0 to 1 and are generally considered acceptable at values above .80. Although there is no set guideline regarding the percentage of individuals in a class, accounting for our sample size, classes containing less than 5% of the sample would have limited clinical relevance (Frankfurt et al., 2016). The results of the LMR compared the chosen model to a model with one less class. A significant p value indicates that the current estimated model performed better than a model with one less class (k − 1). Last, the interpretability of each class was evaluated (van der Nest et al., 2020).

Results

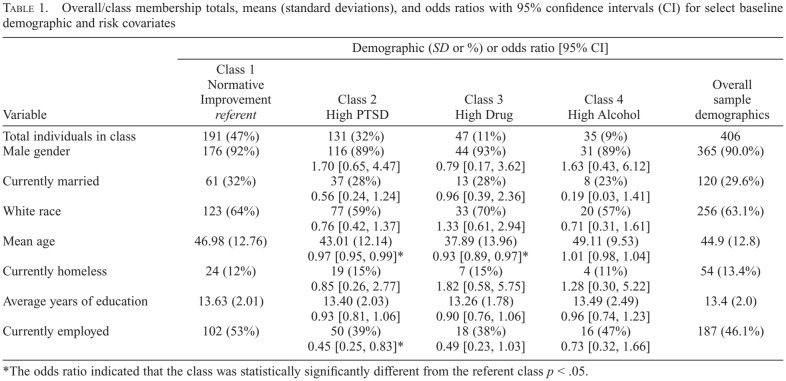

Sample demographics are reported in Table 1. At baseline, participants reported a mean of 27.61 (SD = 30.92) days of drinking alcohol in the past 90 days (31% of days) and a mean of 31.30 (SD = 35.22) days of ingesting drugs in the past 90 days (35% of days). PCL scores for this sample ranged from 17 to 85; M = 54.32, SD = 18.53, α = .95. PCL scores of 50 and above are consistent with clinical features of a PTSD diagnosis; 61% of the sample scored 50 or above (Ruggiero et al., 2003). STS scores of this sample ranged from 0 to 32; M = 8.31, SD = 7.43, α = .88.

Table 1.

Overall/class membership totals, means (standard deviations), and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for select baseline demographic and risk covariates

| Variable | Demographic (SD or %) or odds ratio [95% CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 Normative Improvement referent | Class 2 High PTSD | Class 3 High Drug | Class 4 High Alcohol | Overall sample demographics | |

| Total individuals in class | 191 (47%) | 131 (32%) | 47 (11%) | 35 (9%) | 406 |

| Male gender | 176 (92%) | 116 (89%) | 44 (93%) | 31 (89%) | 365 (90.0%) |

| 1.70 [0.65, 4.47] | 0.79 [0.17, 3.62] | 1.63 [0.43, 6.12] | |||

| Currently married | 61 (32%) | 37 (28%) | 13 (28%) | 8 (23%) | 120 (29.6%) |

| 0.56 [0.24, 1.24] | 0.96 [0.39, 2.36] | 0.19 [0.03, 1.41] | |||

| White race | 123 (64%) | 77 (59%) | 33 (70%) | 20 (57%) | 256 (63.1%) |

| 0.76 [0.42, 1.37] | 1.33 [0.61, 2.94] | 0.71 [0.31, 1.61] | |||

| Mean age | 46.98 (12.76) | 43.01 (12.14) | 37.89 (13.96) | 49.11 (9.53) | 44.9 (12.8) |

| 0.97 [0.95, 0.99]* | 0.93 [0.89, 0.97]* | 1.01 [0.98, 1.04] | |||

| Currently homeless | 24 (12%) | 19 (15%) | 7 (15%) | 4(11%) | 54 (13.4%) |

| 0.85 [0.26, 2.77] | 1.82 [0.58, 5.75] | 1.28 [0.30, 5.22] | |||

| Average years of education | 13.63 (2.01) | 13.40 (2.03) | 13.26 (1.78) | 13.49 (2.49) | 13.4(2.0) |

| 0.93 [0.81, 1.06] | 0.90 [0.76, 1.06] | 0.96 [0.74, 1.23] | |||

| Currently employed | 102 (53%) | 50 (39%) | 18 (38%) | 16 (47%) | 187 (46.1%) |

| 0.45 [0.25, 0.83]* | 0.49 [0.23, 1.03] | 0.73 [0.32, 1.66] | |||

The odds ratio indicated that the class was statistically significantly different from the referent class p < .05.

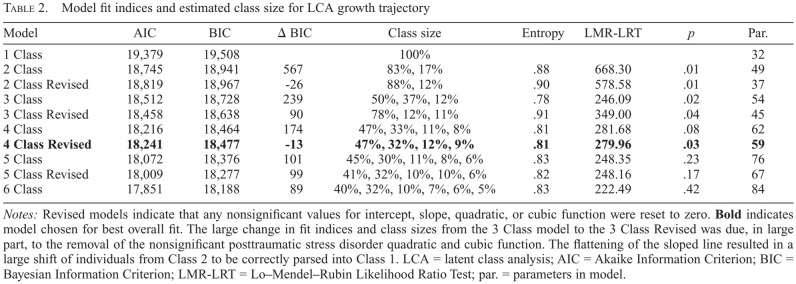

The model fit indices for 1–6 latent class solutions indicated that the 4-class revised solution was the best-performing model (Table 2). The final model comrpised 59 parameters, the LMR was significant at 279.96 (at 5 classes the LMR moved to a nonsignificant value), entropy was acceptable at 0.81, and the classes were all within an acceptable size range (>9% of the sample) and clinically relevant. Average latent class probabilities of inclusion in the 4-class solution were all high and above .85 (Class 1 = .91, Class 2 = .90, Class 3 = .91, and Class 4 = .86). This meant that, for example, there was a 91% probability on average of an individual being correctly classified to Class 1.

Table 2.

Model fit indices and estimated class size for LCA growth trajectory

| Model | AIC | BIC | Δ BIC | Class size | Entropy | LMR-LRT | p | Par. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Class | 19,379 | 19,508 | 100% | 32 | ||||

| 2 Class | 18,745 | 18,941 | 567 | 83%, 17% | .88 | 668.30 | .01 | 49 |

| 2 Class Revised | 18,819 | 18,967 | −26 | 88%, 12% | .90 | 578.58 | .01 | 37 |

| 3 Class | 18,512 | 18,728 | 239 | 50%, 37%, 12% | .78 | 246.09 | .02 | 54 |

| 3 Class Revised | 18,458 | 18,638 | 90 | 78%, 12%, 11% | .91 | 349.00 | .04 | 45 |

| 4 Class | 18,216 | 18,464 | 174 | 47%, 33%, 11%, 8% | .81 | 281.68 | .08 | 62 |

| 4 Class Revised | 18,241 | 18,477 | -13 | 47%, 32%, 12%, 9% | .81 | 279.96 | .03 | 59 |

| 5 Class | 18,072 | 18,376 | 101 | 45%, 30%, 11%, 8%, 6% | .83 | 248.35 | .23 | 76 |

| 5 Class Revised | 18,009 | 18,277 | 99 | 41%, 32%, 10%, 10%, 6% | .82 | 248.16 | .17 | 67 |

| 6 Class | 17,851 | 18,188 | 89 | 40%, 32%, 10%, 7%, 6%, 5% | .83 | 222.49 | .42 | 84 |

Notes: Revised models indicate that any nonsignificant values for intercept, slope, quadratic, or cubic function were reset to zero. Bold indicates model chosen for best overall fit. The large change in fit indices and class sizes from the 3 Class model to the 3 Class Revised was due, in large part, to the removal of the nonsignificant posttraumatic stress disorder quadratic and cubic function. The flattening of the sloped line resulted in a large shift of individuals from Class 2 to be correctly parsed into Class 1. LCA = latent class analysis; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendel-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test; par. = parameters in model.

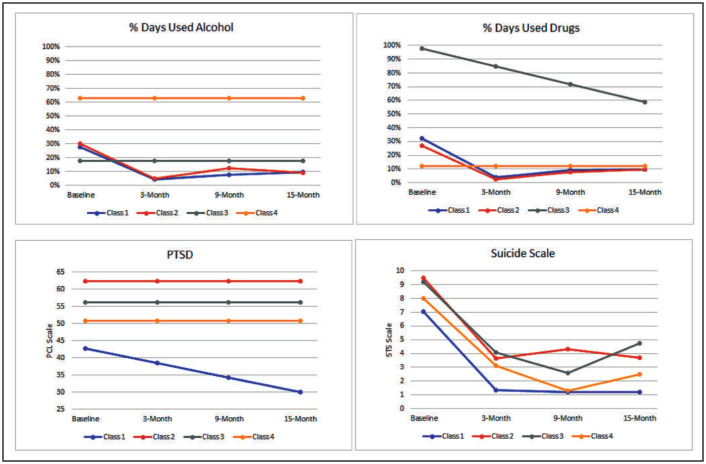

Figure 1 represents a graphical illustration of the four classes over time.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the simultaneous latent class trajectories for percent days used alcohol, percent days used drugs, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicidal ideation across the 15-month study timeline. Class 1 = Normative Improvement (47%), Class 2 = High PTSD (32%), Class 3 = High Drug Use (11%), and Class 4 = High Alcohol (9%). PCL = PTSD Checklist; STS = Sheehan Suicide Tracking Scale.

PTSD symptomatology, which improved across time. The class also had the lowest level of suicidal ideation, which decreased from baseline to 3 months and then stabilized at 9 and 15 months. Similarly, alcohol and drug use decreased in a comparable trajectory from baseline to 3 months, rebounded slightly from 3 to 6 months, and then stabilized throughout the remaining time points of the study. The term normative is used to define this class to suggest that it is the most populous class and that the symptom indicators (PTSD and SUD) changed across time in a pattern consistent with improvement, from a public health perspective.

Class 2—The High PTSD class (33%, magenta lines in Figure 1)—is distinguished by its extremely high and stable PTSD symptomatology across all 15 months of follow-up. The suicidal ideation scores for this class were more than two points (20%) higher at each time point when compared with Class 1. The drug and alcohol use trajectories followed a similar pattern as for Class 1—an initial decline from baseline to 3 months and a leveling off from 3 to 15 months.

Class 3—The High Drug Use class (11%, green lines in Figure 1)—is characterized by an extremely high frequency of drug use at treatment intake that declined gradually over the postdischarge period, yet remained substantially higher than the other classes. Alcohol use was low (18% of days in the past 90 days) and remained stable across time. PTSD symptom level was high and unchanged from treatment intake through follow-up. Suicidal ideation was highest at treatment intake and decreased from baseline to 9 months. However, suicidal ideation increased from 9 months to 15 months.

Class 4—The High Alcohol class (9%, red lines in Figure 1)—is notable for a very high frequency of alcohol use (63% of days in the past 90 days), which remained stable across all 15 months of follow-up. Drug use in this class was very low and remained stable across time. PTSD scores were stable across time at an estimated mean score of 51, which is just above the clinical cutoff score of 50 for a likely diagnosis of PTSD. Suicidal ideation was moderate at baseline compared with the other classes and followed a similar trajectory to the High Drug Use class in that the trajectory decreased from baseline to 9 months, and then increased slightly from 9 to 15 months.

Table 1 shows the most likely class membership on key baseline demographic variables. All of the tests for significant difference used the Normative Improvement class as the referent. The referent class was older than the High PTSD and the High Drug Use classes. Additionally, the referent class was 2.2 times more likely to have current employment than the High PTSD class.

Discussion

We implemented a person-centered statistical approach to examine distinct patient subgroups on outcomes of substance use, PTSD, and suicidal ideation in a large sample of VA psychiatry inpatients followed over 15 months. We found four distinct clusters (classes) of trajectories that warrant attention for their clinical relevance. Nearly half of the sample (47%) was characterized by a Normative Improvement class trajectory, with improving substance use and suicidal ideation and relatively low PTSD symptoms over time. One third of the sample was in the High PTSD class, which was characterized by extremely high and stable PTSD symptom severity, but consistently low substance use, and initially decreasing and then stable suicidal ideation. The remaining 20% of participants were split almost evenly into two classes, both with sharply decreasing and then slightly increasing levels of suicidal ideation and sustained high PTSD symptoms. The High Drug Use class had an extremely high frequency of drug use at baseline, which declined gradually across time but remained relatively high. The High Alcohol class comprised participants who drank alcohol on two thirds of the previous 90 days at baseline and maintained this frequency of alcohol intake across all 15 months after hospital discharge.

Nearly 80% of the patients in the study reduced the frequency of drinking and drug use by more than 50% from their baseline levels. Specifically, the Normative Improvement and High PTSD classes experienced declines in daily drinking and drug intake from approximately 3 out of 10 days (in the past 90 days) to approximately 1 out of 10 days in the same period. Although the Normative Improvement class as a whole did not reach 100% abstinence, the high average level of change within it suggests that some of its members attained abstinence, and others had large and functionally significant decreases in substance use. Health benefits may be experienced by individuals reducing substance use even if they do not become fully abstinent (Mann et al., 2017). Likewise, the reduction in suicidal ideation among all classes during the first 3 months of follow-up is consistent with findings as to the effectiveness of inpatient psychiatric care combined with ongoing outpatient psychiatric treatment after discharge for treating mental health symptoms (Rosen et al., 2013, 2017).

Of note, from a clinical perspective, the level of reported PTSD symptomatology exceeded clinical cutoffs for PTSD diagnosis and did not improve across time for more than half of the sample. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with previous research among survivors of the World Trade Center bombing (Welch et al., 2016) and survivors of trauma in an inner-city urban community (Lowe et al., 2014), for whom PTSD symptoms improved over time. However, these prior studies reflected symptom changes in individuals with relatively recent exposure to violence and/or recent onset of PTSD. PTSD is likely to be more chronic and stable across time among veterans, especially those with co-occurring SUD and sufficient acuity to receive treatment in inpatient psychiatric care. The more harmful and stable PTSD symptomatology in this population may be partially attributed to the deleterious effects of chronic substance use. Indeed, veterans in the High Drug Use and High Alcohol classes were particularly likely to demonstrate persistent and clinically significant levels of PTSD symptomatology during the 15 months following inpatient psychiatric care, possibly because individuals with co-occurring PTSD and SUD commonly use substances in an attempt to mitigate PTSD symptoms (Leeies et al., 2010). Substance use, however, can exacerbate or perpetuate PTSD symptoms (Leeies et al., 2010). Chronic SUD and PTSD can lead to increased suicidal behavior (Ronzitti et al., 2019), as was evident among veterans in the High Drug Use and High Alcohol classes during the follow-up from the initial hospital stay.

Veterans in these high substance use latent classes may require specialized forms of treatment to be used in inpatient and outpatient settings. Patients with PTSD and SUD can tolerate and benefit from evidence-based trauma-focused PTSD treatment such as Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy (Reisman, 2016). These treatments have been shown to reduce PTSD symptoms but not SUD symptoms (Flanagan et al., 2016). To address the needs of this population more directly, integrated psychosocial treatments for PTSD-SUD, such as Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and SUDs using Prolonged Exposure (COPE; Back et al., 2014, 2019), and combined psychosocial and pharmacological approaches, such as Seeking Safety, a non–exposure-based psychosocial intervention, coupled with sertraline, an anti-depressant medication, have recently been developed. Traditional 12-step mutual help groups also have evidence of benefiting this population (Ouimette et al., 2001). Randomized controlled trials have shown that COPE was effective in reducing PTSD and SUD symptoms (Flanagan et al., 2016). Relatedly, Seeking Safety combined with sertraline resulted in significant reductions in PTSD symptoms maintained one year later, although this treatment did not affect alcohol use (Flanagan et al., 2016). These approaches to treating the complex presentation of SUD and PTSD, sometimes also with suicidal ideation, are promising but need replication in future studies (Flanagan et al., 2016). Existing studies examining these approaches have often excluded patients with acute suicidality (e.g., Norman et al., 2019). Thus, more work is needed to test and adapt these approaches to meet the needs of patients with suicidality, PTSD, and SUD.

Although patients in all classes experienced initial reductions in suicidal ideation, those in the High Alcohol and High Drug Use classes experienced increases in suicidal ideation beginning at 9 months after discharge. Therefore, regular and long-term outpatient mental health treatment after inpatient psychiatric care may be crucial in maintaining patients’ safety from suicidal ideation (Stanley et al., 2018). Despite the importance of such treatment for these patients, the transition from inpatient to outpatient care is challenging, with many patients failing to keep their outpatient appointments and, thus, entering a cycle of repeated psychiatric admissions (i.e., the “revolving door patient”; Juven-Wetzler et al., 2012). Strategies that can help such patients initiate and remain engaged in outpatient treatment include the assignment of a case manager, involvement with outpatient programs while still an inpatient, and family involvement in discharge planning (Boyer et al., 2000; Juven-Wetzler et al., 2012). In addition, continuity-of-care models (patients retain the same clinicians across different levels of care) may be considered because they have been shown to reduce hospital re-admissions and are preferred by staff and patients (Omer et al., 2015). Overall, these findings speak to the purpose and importance of inpatient psychiatric care, namely addressing acute patient needs while providing a warm handoff to continuing services and care. For instance, a warm handoff could include staff-engaged referrals to outpatient services (e.g., primary care, medications for alcohol or opioid use disorder, housing) that include a peer specialist or other staff member initially accompanying the patient to the referred service, or other types of coordinated transfer to care that results in a higher likelihood of care engagement (Taylor & Minkovitz, 2021). Further, our findings underscore that inpatient services alone do not provide a resolution for PTSD or SUD, but rather should ensure patients’ safety and a connection to more prolonged care and monitoring (Wray et al., 2019).

These findings have additional import for clinical treatment. In light of this study's evidence that veterans with comorbid SUD, PTSD, and suicidal ideation have differing and fluctuating clinical presentations following inpatient psychiatric care, providers should develop individualized follow-up care plans that address the unique needs of this patient population. Younger age is one potential indicator that providers can use to help identify a patient's higher-risk clinical trajectory following an inpatient psychiatric stay; that is, patients in the High PTSD and High Drug Use classes were the youngest in the sample. In addition, patients in the High PTSD class were less likely than those in the Normative Improvement class to be employed. Other studies have also found an association of trauma with poorer work functioning and suggested that treatment for co-occurring SUD-PTSD may facilitate better employment-related outcomes (Davis et al., 2012; Jason et al., 2011; Sienkiewicz et al., 2020). Future research should focus on examining additional health and demographic characteristics that can assist providers with differentiating the patient subgroups identified in this study.

Limitations and conclusions

This study's findings should be considered in light of some limitations. Participants were all veterans treated in the Veterans Health Administration, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. We focused on changes in PTSD, substance use, and suicidal ideation in this study, and other relevant variables were not included in the model such as the number of deployments, trauma type, and mutual-help involvement. In addition, there is currently no “gold-standard” regarding global fit indices of latent class analyses, such that the interpretation by our research team may not be definitive. However, this limitation is common to all latent class studies. The findings represent a first step in identifying relevant clinical subgroups based on substance use, PTSD, and suicidal ideation. Further research is needed to examine whether the classes identified in this study are evident in other SUD-MHD populations.

Even with these limitations, this study extends existing research in three critical ways. First, the analytic approach allowed examination of the influence of PTSD and suicidal ideation on substance use simultaneously over time. Second, this study used the person-centered approach of growth trajectory modeling, instead of an a priori method of assigning predetermined categories, to examine drug and alcohol use across time. Hence, the modeling allowed the data to uncover the relevant patient classes based on substance use, PTSD, and suicidal ideation; determine whether there was meaningful heterogeneity in the trajectory classes; and assess how the trajectory clusters differed in terms of baseline characteristics. Third, this study informs clinical practice by suggesting that there are still critical treatment gaps for patients who are admitted to inpatient psychiatric settings with relatively severe alcohol, drug use, and PTSD symptoms, to facilitate their improved functioning after discharge. Specific gaps include understanding how to best treat the High PTSD, High Alcohol, and High Drug Use classes, and why suicidal ideation increased among patients in the high substance use classes. Last, these findings suggest that integrated treatments of longer duration (Richardson et al., 2020) during the posthospital period along with effective linkage interventions for engaging patients in these treatments may be needed for individuals with high substance use and high treatment dropout to achieve and maintain good mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrea Finlay, Ph.D., for her thoughtful suggestions and guidance in the early design of the statistical model, and Mai Chee Lor, M.P.H., for help with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Noel Vest was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32DA035165. In addition, this research was supported by an Investigator Initiated Research project (IAC 09-055 to Christine Timko and Mark Ilgen as Multiple Principal Investigators), Senior Research Career Scientist Awards (RCS 00-001 to Christine Timko; RCS 14-141 to Keith Humphreys), and Research Career Scientist Awards (RCS 14-232 to Dr. Harris and RCS 19-333 to Mark Ilgen) by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service. This study was also supported in part by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations and HSR&D Service Research funds (Fernanda Rossi). The views expressed are the authors’and do not necessarily reflect the official position of any government agency.

References

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: A 3-step approach using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2014;21:329–341. doi:10.1080/10705511.2014.915181. [Google Scholar]

- Back S. E., Foa E. B., Killeen T. K., Mills K. L., Teesson M., Cotton B. D., Brady K. T. Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Substance Use Disorders Using Prolonged Exposure (COPE) Patient Workbook. 2014 doi:10.1093/med:psych/9780199334513.001.0001. [Google Scholar]

- Back S. E., Killeen T., Badour C. L., Flanagan J. C., Allan N. P., Santa Ana E., Brady K. T. Concurrent treatment of substance use disorders and PTSD using prolonged exposure: A randomized clinical trial in military veterans. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;90:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.032. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer C. A., McAlpine D. D., Pottick K. J., Olfson M. Identifying risk factors and key strategies in linkage to outpatient psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1592–1598. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1592. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton P. C., Stephens B., Wu J., Kane C., Gallegos A., Ashrafioun L., Conner K. R. Comorbid depression and alcohol use disorders and prospective risk for suicide attempt in the year following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;187:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.029. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola J. S., Koppenhaver J. M., Alterman A. I., McKay J. R. Posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychopathology in substance abusing patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.018. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric V., Stock E. G., Pultz J., Marcus R., Sheehan D. V. Sheehan suicidality tracking scale (Sheehan-STS): Preliminary results from a multicenter clinical trial in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry. 2009;6(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L. L., Leon A. C., Toscano R., Drebing C. E., Ward L. C., Parker P. E., Drake R. E. A randomized controlled trial of supported employment among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63:464–470. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100340. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debell F., Fear N. T., Head M., Batt-Rawden S., Greenberg N., Wessely S., Goodwin L. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49:1401–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin E. R., Bergman H. E., Walton T. O., Walker D. D., Kaysen D. L. Co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder in U.S. military and veteran populations. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2018;39:161–169. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v39.2.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J. C., Korte K. J., Killeen T. K., Back S. E. Concurrent treatment of substance use and PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2016;18 doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0709-y. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt S., Frazier P., Syed M., Jung K. R. Using group-based trajectory and growth mixture modeling to identify classes of change trajectories. Counseling Psychologist. 2016;44:622–660. doi:10.1177/0011000016658097. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen M. A., Hu K. U., Moos R. H., McKellar J. Continuing care after inpatient psychiatric treatment for patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:982–988. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.982. doi:10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Llopis E., Matytsina I.2006Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: A review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs Drug and Alcohol Review 25515–536.doi:10.1080/09595230600944461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason L. A., Mileviciute I., Aase D. M., Stevens E., DiGangi J., Contreras R., Ferrari J. R. How type of treatment and presence of PTSD affect employment, self-regulation, and abstinence. North American Journal of Psychology. 2011;13:175–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T., Wickrama K. A. S. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x. [Google Scholar]

- Juven-Wetzler A., Bar-Ziv D., Cwikel-Hamzany S., Abudy A., Peri N., Zohar J. A pilot study of the “Continuation of Care” model in “revolving-door” patients. European Psychiatry. 2012;27:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler H. R., Rosenthal R. N. Dual diagnosis: Alcoholism and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12:s26–s40. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00494.x. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeies M., Pagura J., Sareen J., Bolton J. M. The use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:731–736. doi: 10.1002/da.20677. doi:10.1002/da.20677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y., Mendell N. R., Rubin D. B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. doi:10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S. R., Galea S., Uddin M., Koenen K. C. Trajectories of posttraumatic stress among urban residents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;53:159–172. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9634-6. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder K. M., Frueh B. C., Knapp R. G., Johnson M. R., Vaughan J. A., Carson T. C., Hebert R. PTSD symptoms, demographic characteristics, and functional status among veterans treated in VA primary care clinics. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:293–301. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038477.47249.c8. doi:10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038477.47249.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K., Aubin H. J., Witkiewitz K. Reduced drinking in alcohol dependence treatment, what is the evidence? European Addiction Research. 2017;23:219–230. doi: 10.1159/000481348. doi:10.1159/000481348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark T., Tomic K. S., Kowlessar N., Chu B. C., Vandivort-Warren R., Smith S. Hospital readmission among Medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2013;40:207–221. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9323-5. doi:10.1007/s11414-013-9323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvasti J. A., Wank A. A. Suicide in U.S. veterans. American Journal of Forensic Psychology. 2013;31:27–54. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Cacciola J. C., Alterman A. I., Rikoon S. H., Carise D. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: Origins, contributions and transitions. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:113–124. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. doi:10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2017. Mplus user's guide. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01711.x. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S. Group-based trajectory modeling: An overview. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2014;65:205–210. doi: 10.1159/000360229. doi:10.1159/000360229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S. B., Trim R., Haller M., Davis B. C., Myers U. S., Colvonen P. J., Mayes T. Efficacy of integrated exposure therapy vs integrated coping skills therapy for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:791–799. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0638. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer S., Priebe S., Giacco D. Continuity across inpatient and outpatient mental health care or specialisation of teams? A systematic review. European Psychiatry. 2015;30:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.08.002. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P., Humphreys K., Moos R. H., Finney J. W., Cronkite R., Federman B. Self-help group participation among substance use disorder patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00150-1. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J. M., Malte C. A., Rubinsky A. D., Campellone T. R., Gilmore A. K., Baer J. S., Hawkins E. J. High inpatient utilization among Veterans Health Administration patients with substance-use disorders and co-occurring mental health conditions. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44:386–394. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1381701. doi:10.1080/00952990.2017.1381701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif S., Acevedo A., Garnick D. W., Fullerton C. A. Reducing behavioral health inpatient readmissions for people with substance use disorders: Do follow-up services matter? Psychiatric Services. 2017;68:810–818. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600339. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201600339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman M. PTSD treatment for veterans: What's working, what's new, and what's next. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2016;41:623–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A., Richard L., Gunter K., Cunningham R., Hamer H., Lockett H., Derrett S. A systematic scoping review of interventions to integrate physical and mental healthcare for people with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;128:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.021. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronzitti S., Loree A. M., Potenza M. N., Decker S. E., Wilson S. M., Abel E. A., Goulet J. L. Gender differences in suicide and self-directed violence risk among veterans with post-traumatic stress and substance use disorders. Women's Health Issues. 2019;29:S94–S102. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen C. S., Azevedo K. J., Tiet Q. Q., Greene C. J., Wood A. E., Calhoun P., Schnurr P. P. An RCT of effects of telephone care management on treatment adherence and clinical outcomes among veterans with PTSD. Psychiatric Services. 2017;68:151–158. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen C. S., Tiet Q. Q., Harris A. H. S., Julian T. F., McKay J. R., Moore W. M., Schnurr P. P. Telephone monitoring and support after discharge from residential PTSD treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64:13–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200142. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. N. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003. Dual diagnosis. doi:10.4324/9780203486320. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero K. J., Del Ben K., Scotti J. R., Rabalais A. E. Psycho-metric properties of the PTSD Checklist - Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. doi:10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz M. E., Amalathas A., Iverson K. M., Smith B. N., Mitchell K. S. Examining the association between trauma exposure and work-related outcomes in women veterans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124585. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Brown J., Leo G. I., Sobell M. B. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B., Brown G. K., Brenner L. A., Galfalvy H. C., Currier G. W., Knox K. L., Green K. L. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55) Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. M., Minkovitz C. S. Warm handoffs for improving client receipt of services: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2021;25:528–541. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03057-4. doi:10.1007/s10995-020-03057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters J., Lancaster C., Brown D., Back S. Substance use disorders in military veterans: Prevalence and treatment challenges. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2017;8:69–77. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S116720. doi:10.2147/sar.s116720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C., Harris A. H. S., Jannausch M., Ilgen M. Randomized controlled trial of telephone monitoring with psychiatry inpatients with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;194:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.010. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein M., Kim H. M., Ganoczy D., McCarthy J. F., Zivin K., Austin K. L., Olfson M. Higher-risk periods for suicide among VA patients receiving depression treatment: Prioritizing suicide prevention efforts. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;112:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.020. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Nest G., Passos V. L., Candel M. J., van Breukelen G. J. An overview of mixture modelling for latent evolutions in longitudinal data: Modelling approaches, fit statistics and software. Advances in Life Course Research. 2020;43:100323. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2019.100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Herman D. S., Huska J. A., Keane T. M.The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies,; San Antonio, TX. October, 1993; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Welch A. E., Caramanica K., Maslow C. B., Brackbill R. M., Stellman S. D., Farfel M. R. Trajectories of PTSD among Lower Manhattan residents and area workers following the 2001 World Trade Center disaster, 2003-2012. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2016;29:158–166. doi: 10.1002/jts.22090. doi10.1002/jts.22090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford H. A., Degenhardt L., Rehm J., Baxter A. J., Ferrari A. J., Erskine H. E., Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382:1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco B. E., Marx B. P., Wolf E. J., Miller M. W., Southwick S. M., Pietrzak R. H. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the US veteran population: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2014;75:1338–1346. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09328. doi:10.4088/JCP.14m09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray A. M., Hoyt T., Welch S., Civetti S., Anthony N., Ballester E., Tandon R. Veterans Engaged in Treatment, Skills, and Transitions for Enhancing Psychiatric Safety (VETSTEPS) Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2019;42:277–283. doi: 10.1037/prj0000360. doi:10.1037/prj0000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]