Abstract

Purpose of the Review:

This paper reviews the recent literature on menstrual cycle phase effects on outcomes relevant to anxiety and PTSD, discusses potential neurobiological mechanisms underlying these effects, and highlights methodological limitations impeding scientific advancement.

Recent Findings:

The menstrual cycle and its underlying hormones impact symptom expression among women with anxiety and PTSD, as well as psychophysiological and biological processes relevant to anxiety and PTSD.

Summary:

The most consistent findings are retrospective self-report of premenstrual exacerbation of anxiety symptoms and the protective effect of estradiol on recall of extinction learning among healthy women. Lack of rigorous methodology for assessing menstrual cycle phase and inconsistent menstrual cycle phase definitions likely contribute to other conflicting results. Further investigations that address these limitations and integrate complex interactions between menstrual cycle phase related hormones, genetics, and psychological vulnerabilities are needed to inform personalized prevention and intervention efforts for women.

Keywords: anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, menstrual cycle, extinction recall, CO2 challenge, premenstrual exacerbation

Introduction

Women are twice as likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than men [1,2]. Women with anxiety or PTSD are also more likely to have comorbid mental and physical health diagnoses and greater illness burden than men [3]. These differences suggest that there are gender- and/or sex-specific mechanisms involved in the etiology and/or maintenance of anxiety and PTSD. Understanding these mechanisms is critical to the development and enhancement of psychological and psychopharmacological intervention efforts for women.

The menstrual cycle, characterized by the cyclical rise and fall of estradiol, progesterone, and psychoactive metabolites of progesterone, likely contributes to the increased risk for anxiety disorders and PTSD in women. Menstrual cycle-related changes in affect are well documented. In healthy women, psychological and physical symptoms are often exacerbated during the late luteal/premenstrual and early follicular phases of the menstrual cycle when estradiol and progesterone are declining or low [4]. Furthermore, women have shown late luteal/premenstrual exacerbations across a range of mental health disorders [5].

In this article, we review: a) menstrual cycle phase exacerbations in symptoms among women with anxiety and PTSD, b) laboratory paradigms in clinical and non-clinical samples that capture underlying neurophysiological processes relevant to anxiety disorders and/or PTSD across the menstrual cycle (e.g., CO2 challenge, fear conditioning), c) potential neurobiological mechanisms underlying menstrual cycle phase effects, d) methodological limitations of past research and recommendations for future research, and e) clinical implications of this research.

The Menstrual Cycle

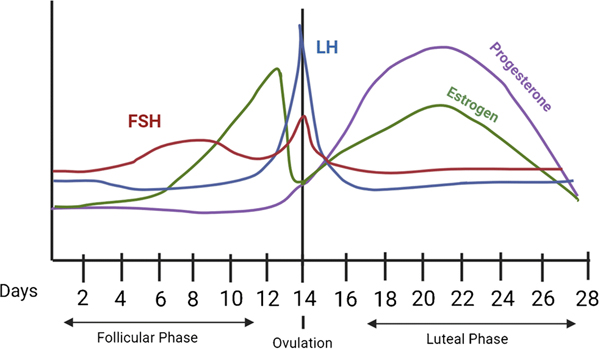

Typical menstrual cycles range between 21 and 35 days, with the majority of the variance in total menstrual cycle length occurring in the follicular phase vs. the more predictable 14-day luteal phase [6]. In a standard 28-day cycle (Fig. 1), menstruation begins on Day 1 and lasts for approximately 5 days. During the ‘early follicular’ or ‘menstrual’ phase of the cycle (Days 1–5), levels of 17β-estradiol and progesterone are at their lowest. In the mid to late follicular phase (Days 6–12), progesterone remains low and stable while estrogen rises to peak cycle levels. The following ovulatory phase (Days 13–15) is characterized by a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and decline of 17β-estradiol. Following ovulation, the early to mid-luteal phase is characterized by a steep rise and stabilization of progesterone along with a moderate rise and stabilization of 17β-estradiol. This is followed by the ‘late luteal’ or ‘premenstrual’ phase (Days 24–28), during which 17β-estradiol and progesterone levels decline rapidly before the onset of the next menses.

Figure 1.

Hormone Changes Across the Menstrual Cycle

Menstrual Cycle-Related Psychiatric Symptom Exacerbations Among Women with Anxiety and PTSD

A small body of literature documents symptom exacerbations in anxiety disorders and PTSD during specific menstrual cycle phases. Across disorders, increases in disorder-specific symptoms have been demonstrated in the premenstrual phase, but most of this research has been conducted in individuals with panic disorder (PD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). When assessed retrospectively, women with PD consistently report an increase in the frequency and severity of panic attacks, as well as an increase in anxiety and negative mood during the premenstrual phase (defined across studies as 5–8 days before the onset of menses) as compared to other menstrual phases [7–11]. Results are mixed, however, when panic and anxiety symptoms are assessed prospectively. In some studies using daily reports, women with PD reported increased panic attacks and anxiety during the premenstrual phase (within 8 days before menses) [10, 11]. In contrast, other prospective PD studies found no differences in anxiety or panic attack frequency between the premenstrual phase (within 5 days before menses) and other phases [8, 9, 12, 13]. The majority of studies did not examine or control for menstrual-cycle related symptoms (e.g., physical symptoms) in analyses. However, one recent study found no menstrual cycle phase and panic disorder group interaction on affective and physical symptoms [10]. Specifically, both women with and without panic disorder reported increased affective symptoms in the premenstrual phase as compared to the menstrual and follicular phase, and more physical symptoms in the menstrual phase as compared to the premenstrual and follicular phases [10].

Among women with OCD, 20–42% retrospectively reported an exacerbation of OCD symptoms during the premenstrual phase [within 7 days before menses; 14, 15]. Similarly, 54% of women with compulsive hair pulling retrospectively reported increased hair pulling frequency and intensity, and a decrease in perceived ability to control hair pulling during the premenstrual phase (within 7 days before onset of menses) compared to the early to mid-follicular phase (i.e., up to seven days from menses onset; [16]). We are aware of only one prospective study investigating OCD symptom expression across the menstrual cycle, which confirmed an increase in symptoms during the premenstrual phase (within 3 days before menses onset) compared to mid-cycle (12–15 days after menses onset) in women reporting premenstrual increases in OCD symptoms [17]).

Similar patterns have emerged among women with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD). Approximately 45% of women with generalized social anxiety retrospectively reported menstrual cycle influences on social anxiety and avoidance symptoms [18]. Among these women, social anxiety symptoms were more severe during the premenstrual phase (i.e., last week of the menstrual cycle). Women with comorbid GAD and premenstrual syndrome also prospectively reported more anxiety symptoms during the premenstrual phase (within 7 days before onset of menses) compared to the follicular phase (within 7 days following termination of menses) [19].

There is also some evidence for symptom exacerbations during the mid-luteal phase. For example, women with GAD, but not non-anxious controls, reported an increase in repetitive negative thinking and negative affect from the early follicular to mid-luteal phase [20]. Another study found no differences between the early follicular and mid-luteal phases in mental and physical fatigue among women with GAD, but an increase in mental fatigue in non-anxious women to levels equivalent to their GAD counterparts from the early follicular to mid-luteal phases [21].

There is limited research on the exacerbation of trauma-related symptoms across the menstrual cycle. One prospective study assessed a broad range of psychological symptoms in the early follicular and mid-luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in trauma-exposed women with and without PTSD. Women with PTSD reported more fear-related and avoidance symptoms during the premenstrual and menstrual phases than the early- to mid-luteal phases [22]. Bryant and colleagues [23], however, found that women reported more trauma-related flashbacks1–2 weeks after trauma exposure if the flashbacks were assessed during the mid-luteal phase (18–24 days after menses onset) vs. other menstrual cycle phases. Additionally, women exposed to a traumatic event in the mid-luteal phase reported more flashbacks when assessed 1–2 weeks later [23]. These findings are consistent with those of Ferree et al. [24] in a non-clinical sample showing an increase in spontaneous intrusive recollections of a violent and distressing film when viewed in the luteal phase (15–28 after menses onset) vs. the follicular phase (1–13 days after menses onset). These contradictory findings from the few studies evaluating menstrual phase effects in women with trauma exposure and/or PTSD suggest that intrusive flashbacks [23] may be exacerbated during different menstrual phases than more broadly defined fear and avoidance symptoms [22].

In summary, evidence supports the presence of menstrual phase-related fluctuations in symptoms among women with a range of anxiety disorders. However, these findings are most consistently demonstrated in studies using retrospective symptom reports. The findings from prospective studies are limited and more equivocal. Limited research also suggests that women with PTSD experience premenstrual and menstrual phase exacerbations of fear and avoidance symptoms. However, sensory-based intrusion symptoms (i.e., flashbacks) appear to be exacerbated during the mid-luteal phase, aligning with new research in women with GAD demonstrating mid-luteal exacerbation of repetitive negative thinking and negative affect.

Menstrual Cycle Effects in Laboratory Paradigms Relevant to Anxiety Disorders and PTSD

Several laboratory paradigms have been used to study mechanisms related to the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders. One widely used paradigm is ‘CO2 challenge’ in which CO2-enriched air is breathed for 3–5 minutes to evoke physiological symptoms of anxiety [25]. Reactivity to the CO2 challenge in non-clinical samples prospectively predicts anxiety-related pathology [26]. Women with clinically significant premenstrual symptoms (PMS) [27] or PD [28] experience increased panic symptoms in response to CO2 challenge during the premenstrual and menstrual phases as compared to other menstrual cycle phases. In contrast, women without psychopathology did not differ in their responses to CO2 challenge across the menstrual cycle. Women with PD also demonstrated increased panic, anxiety, and psychophysiological reactivity (e.g., skin conductance responses) while listening to provocative audiotapes during the premenstrual phase vs. other cycle phases; controls exhibited no menstrual phase-related effects in this paradigm [12].

The Trier Social Stress Test [TSST] is another well-validated laboratory paradigm that evaluates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (e.g., cortisol) and subjective anxiety responses to social evaluative threat [29]. Although menstrual cycle phase does not impact pre-TSST cortisol levels and subjective anxiety in healthy women, post-TSST cortisol levels differ by menstrual cycle phase [e.g., 30, 31]. The specific menstrual cycle phases assessed, along with the methods used to determine menstrual cycle phase, have varied across studies and make interpretation of the conflicting findings difficult. For example, one study found an increased cortisol response in the luteal phase (Days 18–26) compared to the follicular phase (Days 2–8) [31], while another found increased cortisol responses in the follicular (2–4 days after the onset of menses) compared to the luteal phase (8–10 days post LH surge) [30].

There is also work examining menstrual phase effects on acoustic startle reactivity and other psychophysiological indices. Some, but not all studies of healthy women demonstrated increased acoustic startle responses in the late luteal vs. early follicular phase [e.g., 32]. However, studies in trauma-exposed women with and without PTSD showed no differences in acoustic startle or prepulse inhibition in the midluteal phase compared to the early follicular phase [33].

As reviewed by Garcia, Walker, and Zoellner [34], as well as Ravi, Stevens, & Michopoulos [35], a growing collection of studies have investigated menstrual phase and hormone effects in laboratory-based fear conditioning, extinction, and extinction recall paradigms. Most of this research has focused on the effects of relatively high vs. low levels of 17β-estradiol on task performance, with a minority of studies also investigating progesterone. Few studies have investigated task performance in relationship to hormone levels across explicitly characterized menstrual cycle phases.

Notably, studies in community samples provide scant evidence for menstrual phase or hormone effects on conditioned fear acquisition and extinction learning [e.g., 36, 37]. One study of women without psychopathology demonstrated stronger conditioned fear acquisition in the luteal vs. follicular phase [38]. There is, however, robust support from studies in women without psychopathology for menstrual phase and hormone effects on extinction recall (i.e., the degree to which extinction learning is retained when tested in a separate session—often the next day). Specifically, women without psychopathology demonstrated better extinction recall when estradiol levels were relatively high based on a median split [e.g., 39, 40]. Women without psychopathology also showed best extinction recall during the mid-luteal phase when both estradiol and progesterone were high compared to the early follicular phase when both hormones were relatively low [41].

Only a few studies have investigated fear conditioning and extinction in women with psychopathology. Some support the protective effects of estradiol. Although there was no relationship between estradiol and extinction learning in women without PTSD, low estradiol levels were associated with deficits in extinction learning in women with PTSD [42]. In addition, women with and without spider phobia showed a positive relationship between estradiol levels and extinction recall [40]. In contrast, women with and without PTSD demonstrated different menstrual phase effects on extinction recall [41]. Whereas healthy women without PTSD demonstrated enhanced extinction recall in the mid-luteal vs. early follicular phase, women with PTSD showed deficits in extinction recall during the mid-luteal vs. early follicular phase [41]. Deficits in the conversion of progesterone into allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are more likely in women with PTSD than women without PTSD [43, 44] and were associated with poor extinction recall in women with PTSD during the mid-luteal phase when both progesterone and estradiol are relatively high [45]. The observation of mid-luteal phase deficits in extinction recall in women with PTSD thus may align with the findings of Bryant et al. [23], wherein increased flashbacks were reported by individuals who experienced trauma and/or were assessed during the mid-luteal phase.

Potential Mechanisms Underlying Menstrual Cycle Phase Differences in Anxiety and PTSD

Menstrual phase influences on symptoms of anxiety and PTSD occur in only a subpopulation of women—consistent with the biological heterogeneity of these conditions [46]. Here we address several hormone-related phenomena that may contribute to menstrual phase effects on anxiety and PTSD.

For example, several studies report an exacerbation of anxiety or PTSD symptoms in the premenstrual and menstrual phases of the menstrual cycle when levels of 17β-estradiol, progesterone, and progesterone metabolites that positively modulate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) effects GABAA receptors fall precipitously and stabilize at low levels characteristic of the early follicular phase. While low GABAergic neurosteroid levels may contribute directly to anxiety, abrupt reductions in progesterone and its metabolites also alter the subunit composition and anxiolytic profile of brain GABAA receptors [47]. Concomitantly, adrenal steroids such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) that facilitate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function while antagonizing GABAA receptor function may effectively compete with low levels of allopregnanolone present during the follicular phase to increase anxiety and PTSD symptoms.

During the late follicular phase, 17β-estradiol levels rise and may account for the apparent protective effects of this phase. As previously reviewed [47], 17β-estradiol activates intra-neuronal receptors with antidepressant effects, as well as receptors embedded in external neuronal membranes that traffic estradiol to nuclear hormone response elements in the promoters of a variety of genes. Activation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in the amygdala is anxiogenic, while activation of ERβ (expressed at highest levels in hippocampus, but also in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex) is anxiolytic and facilitates extinction consolidation and recall [48]. ERβ receptor signaling thus may contribute to the enhanced extinction recall observed in healthy women when estradiol levels are highest. In turn, deficient 17β-estradiol or ERβ signaling in individuals with anxiety disorders or PTSD may contribute to symptom worsening or deficits in extinction recall during the mid-luteal phase. Women also have shown an association between PTSD risk and a single nucleotide polymorphism in an ERα-sensitive gene for the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) type I receptor (PAC1). This polymorphism also conferred poor safety cue discrimination in a differential fear-conditioning paradigm [49]—suggesting that deficient ERα activation also may contribute to increases in anxiety and PTSD symptoms.

A PTSD-related failure to adequately metabolize progesterone into its potent GABAergic metabolites (e.g., allopregnanolone) is also associated with PTSD symptom severity [43, 44] and poor extinction recall during the luteal phase when allopregnanolone synthesis may be pushed to its limit [45]. In female rodents, 17β-estradiol upregulates expression of hippocampal 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [50], the enzyme at which the synthesis of GABAergic neuroactive steroids appears to be blocked in women with PTSD [43, 44]. Therefore, a failure to upregulate this enzyme during the luteal phase may contribute to the 8-fold increase in risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) associated with PTSD [51]. Indeed, some studies have shown low allopregnanolone to be associated with PMDD—and many symptoms of PTSD and PMDD overlap. However, high allopregnanolone levels also have been associated with PMDD, and PMDD symptoms in healthy women without other mental health disorders were reduced by treatment with a steroid that antagonizes allopregnanolone effects on GABAA receptor function [52]. Together these studies suggest that PMDD may be biologically heterogenous. A role for high, as well as low 17β-estradiol levels in the pathophysiology of luteal phase-related increases in anxiety and PTSD symptoms (i.e., flashbacks) also might be considered in this context. 17β-estradiol upregulates brain serotonin (5HT)2A receptors in association with increases in impulsive aggression in women, men and dogs [53, 54], while 5HT2A agonists can increase sensory hallucinations. Together, these studies suggest that a high estradiol/high allopregnanolone/high 5HT2A receptor endophenotype, as well as a low estradiol/low allopregnanolone endophenotypes should be considered in menstrual phase-related exacerbations of anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms.

Limitations of the Extant Literature and Menstrual Cycle Measurement Considerations

Although in its infancy, the extant literature implicates the menstrual cycle in the expression of anxiety disorder and PTSD symptoms, as well as performance in laboratory paradigms tapping mechanisms relevant to these diagnoses. As noted, however, methodological limitations may contribute to variable and equivocal findings in this area of research. A consensus regarding best practices is, therefore, critical to move this research ahead.

First, many studies do not exclude women using hormonal birth control, which prevents ovulation and changes hormone levels and patterns of hormone fluctuation. Similarly, studies that focus on estradiol or progesterone levels rather than menstrual cycle phase often do not exclude women who are peri- or post-menopausal. Many studies also have not excluded women on psychotropic medications. This introduces an important confound, given that these medications alter the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis [e.g., 55], as well as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [56], and even the synthesis of GABAergic neurosteroids.

Compounding these limitations are methodologies that contribute to measurement error. As noted above, there is a heavy reliance on retrospective report of symptoms, which is subject to recall bias [57]. This may be particularly important when assessing symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Beliefs or cultural stereotypes related to the premenstrual phase and menstruation may influence recall of symptom reports. To this end, research suggests that women may over-report premenstrual symptoms when assessed retrospectively vs. prospectively [57]. In addition, measurement of menstrual cycle phase often lacks methodologic rigor. The majority of studies using prospective symptom reports verified menstrual cycle phase solely by day count, which shows only 50% agreement with menstrual phase determined by progesterone and 17β-estradiol assay results [58]. We therefore must emphasize the importance of using at-home luteinizing hormone (LH) and ovulation test kits to establish the presence of normal menstrual cyclicity and a clear transition between the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle. Utilizing LH surge testing, day count, and progesterone and estradiol levels should be regarded as best practice for studies aiming to schedule women for testing during specific menstrual phases. Basal body temperature (BBT) measurement is an alternative to LH surge testing, depending on cost, feasibility, and participant burden considerations. However, this approach would only be appropriate for studies that are not dependent on prospective determination of menstrual cycle phase or when retrospective categorization of menstrual cycle phase is sufficient to test the study aims [59].

Finally, greater consensus and rigor is needed regarding the definition of menstrual cycle phase, the comparison of more than two menstrual cycle phases within the menstrual cycle, and (when possible) the use of within-person designs. Studies vary with regard to menstrual phases assessed and typically compare only two cycle phases, making it difficult to understand unique influences across the full cycle. Many past studies have combined hormonally different phases into a single, overlapping phase (e.g., follicular vs. luteal). Given the unique hormonal events in each phase, aggregating distinct phases may mask important menstrual cycle effects, and limit the potential validity and replicability of results. In an effort to increase comparability across studies and increase the methodologic rigor of research aimed at investigating menstrual phase effects, Schmalenberger et al. [59] recently proposed best methods and practices for assessment of menstrual cycle. Recommendations included: a) within-subject assessment of outcomes across menstrual cycle phases when possible, b) capturing outcome data across at least 3 menstrual cycle phases in order to appropriately model change across the menstrual cycle, c) characterizing reproductive status to ensure participants are naturally-cycling and not pregnant or too close to puberty or menopause, and d) using LH surge or BBT, day count, and progesterone and estradiol levels to determine cycle phase. They also made recommendations for definition of menstrual cycle phases to study: mid-luteal phase (6–10 days post LH surge/9–5 days before menses onset), perimenstrual phase (3 days before to 2 days after menses onset), mid-follicular phase (4–7 days after menses onset or 7–3 days before the LH surge), and periovulatory phase (2 days before to 1 day after the LH surge or 15 to 12 days before menses onset). These proposed recommendations align with discrete hormonal events and if used would increase consistency across studies. It should be noted, however, that there also needs to be some flexibility in these guidelines as certain research questions may be best answered by use of other phase definitions (e.g., early-mid follicular phase (days 3–7 days after menses onset when both estradiol and progesterone levels are low).

Clinical Implications

There is a small and growing body of research investigating the impact of estradiol and progesterone on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral treatment for anxiety and PTSD. Most of these studies do not focus on the menstrual cycle per se. However, research on the association between endogenous or exogenously administered hormones and treatment outcomes suggest how the menstrual cycle might impact treatment. For example, there may be times during the menstrual cycle where interventions may be more or less effective for a subpopulation of women based on what is occurring hormonally. Given the robust support for enhancing effects of estradiol on extinction recall in healthy populations and women with spider phobia, Li & Graham [60] conducted a study assessing the association between endogenous 17β-estradiol levels and the efficacy of an empirically supported one-day exposure treatment for spider phobia. Three groups of women participated in the study including: women on hormonal contraceptives (n=30) and two groups of naturally cycling women divided into a high estradiol group (n=30) and low estradiol group (n=30). Menstrual cycle phase was not rigorously assessed in this study. Across the entire sample, low estradiol was associated with greater self-reported fear and behavioral avoidance post-treatment. However, these effects appear to be primarily driven by the low estradiol levels among women in the hormonal contraceptive group [40], an interesting observation given the concomitant suppressive effects of hormonal contraceptives on progesterone and allopregnanolone. Complementing this work, there is an ongoing clinical trial examining the potential of adjunctive administration of estradiol to enhance Prolonged Exposure outcomes in women with PTSD [clinical_trials.gov identifier: NCT04192266].

Similar findings emerge when examining the impact of hormones on cognitive restructuring for anxiety. In a study of naturally cycling healthy women engaged in a one-session cognitive restructuring intervention after completing a fear conditioning task [60], those with relatively high estradiol levels had greater decreases in skin conductance responses to the previously conditioned CS+ stimuli than women with low estradiol. There were no significant effects for progesterone, but allopregnanolone was not measured. A second study used a similar one-session cognitive restructuring intervention aimed at reducing fear of spiders in naturally cycling women with primary diagnoses of spider phobia. Women with relatively high progesterone levels showed decreased behavioral avoidance of spiders post-treatment compared to women with relatively low progesterone. In contrast to the study by Li & Graham [61], there were no significant effects of estradiol.

Together these studies suggest that sex-related hormones, and possibly menstrual cycle phase, may impact both cognitive and exposure-based interventions. However, there are several important limitations that highlight the need for more research before firm conclusions can be drawn. These include: a) the small number of studies on this topic, b) the lack of focus on menstrual cycle phase, and c) conflicting findings regarding the relative importance of estradiol and progesterone as mechanisms of treatment efficacy, as well as failure to measure the psychoactive GABAergic metabolites of progesterone [46]. Indeed, research into the potential use of allopregnanolone as an adjunct to cognitive or exposure-based interventions is now possible given the recent FDA approval of an intravenous allopregnanolone formulation (brexanolone) for the treatment of postpartum depression.

Conclusions

There is growing evidence that the menstrual cycle and its underlying hormones impact symptom expression, as well as psychophysiological and biological processes relevant to anxiety and PTSD. The growing interest in this nascent research area has fueled a push for more research, as well as greater methodologic rigor and creativity regarding potential clinical applications. For example, more research is needed to disentangle the complex menstrual cycle effects on mood and biological processes. While anxiety, fear and avoidance symptoms in women with anxiety and PTSD tend to increase during phases when estradiol and progesterone are declining or low (i.e., perimenstrual phase), flashbacks appear to be increased when estradiol and progesterone are both high (i.e., mid-luteal phase). Furthermore, the phase at which extinction recall is negatively impacted differs for women with and without PTSD. Collectively, these findings suggest that there is not a universal “at-risk” menstrual cycle phase. Instead, points of hormone dysregulation likely vary in their impact on neural processes and confer different clinical phenotypes. Identifying specific points of dysfunction in the synthesis of hormones and their metabolites or their receptors will therefore be important to development of targeted and personalized interventions for women. There are also gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms by which hormonal contraceptives impact psychological and cognitive processes. Approximately 24% U. S. women age 15–44 are currently using either an oral hormonal contraceptive pill or long-acting reversible contraception (intrauterine device or contraceptive implant; [62]). Therefore, understanding how hormonal contraception may impact these outcomes is vital. In addition, while there has been some initial exciting work in augmenting cognitive behavioral treatments with administration of estradiol, allopregnanolone and its precursors might also represent promising adjunctive treatments yet to be explored. More work is also needed on non-pharmacological approaches, such as targeting interventions to specific menstrual cycle phases. Finally, more rigorous and consistent definitions of menstrual cycle phases and methodologies used to characterize them is needed in order to align findings across studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994:51(1):8–19. Doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull 2006:132(6):959–992. Doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 2011:45(8):1027–1035.Doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonda X, Telek T, Juhász G, Lazary J, Vargha A, Bagdy G. Patterns of mood changes throughout the reproductive cycle in healthy women without premenstrual dysphoric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2008:32(8):1782–1788. Doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Burt VK. Course of Psychiatric Disorders across the Menstrual Cycle. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1996:4(4):200–207, Doi: 10.3109/10673229609030544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fehring RJ, Schneider M, Raviele K. Variability in the Phases of the Menstrual Cycle. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006:35(3):376–384. Doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breier A, Charney DS, Heninger GR. Agoraphobia With Panic Attacks: Development, Diagnostic Stability, and Course of Illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986:43(11):1029–1036. Doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800110015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron OG, Kuttesch D, McPhee K, Curtis GC. Menstrual fluctuation in the symptoms of panic anxiety. J Affect Disord 1988:15(2):169–174. Doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook BL, Russell N, Garvey MJ, Beach V, Sobotka J, Chaudhry D. Anxiety and the menstrual cycle in panic disorder. J Affect Disord 1990:19(3):221–226. Doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90095-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haigh EAP, Craner JR, Sigmon ST, et al. Symptom Attributions Across the Menstrual Cycle in Women with Panic Disorder. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 2018:36:320–332. Doi: 10.1007/s10942-018-0288-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaspi SP, Otto MW, Pollack MH, Eppinger S, Rosenbaum JF. Premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms in women with panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1994:8(2):131–138. Doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(94)90011-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigmon ST, Dorhofer DM, Rohan KJ, Boulard NE. The Impact of Anxiety Sensitivity, Bodily Expectations, and Cultural Beliefs on Menstrual Symptom Reporting: A Test of the Menstrual Reactivity Hypothesis. J Anxiety Disord 2000:14(6):615–633. Doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein MB, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR, Uhde TW. Panic disorder and the menstrual cycle: panic disorder patients, healthy control subjects, and patients with premenstrual syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1989:146(10):1299–303. Doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.10.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labad J, Menchón JM, Alonso P, Segalàs C, Jiménez S, Vallejo J. Female reproductive cycle and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005:66(4):428–35. Doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams KE, Koran LM. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnancy, the puerperium, and the premenstruum. J Clin Psychiatry 1997:58(7):330–4; quiz 335–6. Doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keuthen NJ, O’Sullivan RL, Hayday CF, Peets KE, Jenike MA, Baer L. The Relationship of Menstrual Cycle and Pregnancy to Compulsive Hairpulling. Psychother psychosom 1997:66:33–37. Doi: 10.1159/000289103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vulink NCC, Denys D, Bus L, Westenberg HGM. Female hormones affect symptom severity in obsessive–compulsive disorder, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006:21(3):171–175. Doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000199454.62423.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Veen JF, Jonker BW, Van Vliet IM, Zitman FG. The Effects of Female Reproductive Hormones in Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med 2009:39(3):283–295. Doi: 10.2190/PM.39.3.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod DR, Hoehn Saric R, Foster GV, Hipsley PA. The influence of premenstrual syndrome on ratings of anxiety in women with generalized anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993:88:248–251. Doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SH, Graham BM. Progesterone levels predict reductions in behavioral avoidance following cognitive restructuring in women with spider phobia. J Affect Disord 2020:270:1–8. Doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li SH, Lloyd AR, Graham BM. Physical and mental fatigue across the menstrual cycle in women with and without generalised anxiety disorder. Horm Behav 2020:118:104667. Doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2019.104667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nillni YI, Pineles SL, Patton SC, Rouse MH, Sawyer AT, Rasmusson AM. Menstrual Cycle Effects on Psychological Symptoms in Women With PTSD. J Trauma Stress 2015:28:1–7. Doi: 10.1002/jts.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant RA, Felmingham KL, Silove D, Creamer M, O’Donnell M, McFarlane AC. The association between menstrual cycle and traumatic memories. J Affect Disord 2011:131(1–3):398–401. Doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferree NK, Kamat R, Cahill L. Influences of menstrual cycle position and sex hormone levels on spontaneous intrusive recollections following emotional stimuli. Consciousness and cognition 2011:20(4):1154–62. Doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JJW, Ein N, Gervasio J, Vickers K. The efficacy of stress reappraisal interventions on stress responsivity: A meta-analysis and systematic review of existing evidence. PLoS One 2019:27;14(2):e0212854. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity and CO2 challenge reactivity as unique and interactive prospective predictors of anxiety pathology. Depress. Anxiety 2007:24:527–536. Doi: 10.1002/da.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nillni YI, Pineles SL, Rohan KJ, Zvolensky MJ, Rasmusson AM. The influence of the menstrual cycle on reactivity to a CO2 challenge among women with and without premenstrual symptoms. Cogn Behav Ther 2016:46:3:239–249. Doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1236286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perna G, Brambilla F, Arancio C, Bellodi L. Menstrual cycle-related sensitivity to 35% CO2 in panic patients. Biol Psychiatry 1995:37(8):528–32. Doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00154-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28(1–2):76–81. Doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maki PM, Mordecai KL, Rubin LH, Sundermann E, Savarese A, Eatough E, Drogos L. Menstrual cycle effects on cortisol responsivity and emotional retrieval following a psychosocial stressor. Horm Behav 2015:74:201–8. Doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montero-López E, Santos-Ruiz A, García-Ríos MC, Rodríguez-Blázquez M, Rogers HL, Peralta-Ramírez MI. The relationship between the menstrual cycle and cortisol secretion: Daily and stress-invoked cortisol patterns. Int J Psychophysiol 2018:131:67–72. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armbruster D, Grage T, Kirschbaum C, Strobel A. Processing emotions: Effects of menstrual cycle phase and premenstrual symptoms on the startle reflex, facial EMG and heart rate. Behav Brain Res 2018:351:178–87. Doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pineles SL, Blumenthal TD, Curreri AJ, Nillni YI, Putnam KM, Resick PA, Rasmusson AM, Orr SP. Prepulse inhibition deficits in women with PTSD. Psychophysiology 2016:53(9):1377–85. Doi: 10.1111/psyp.12679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia NM, Walker RS, Zoellner LA. Estrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle: A systematic review of fear learning, intrusive memories, and PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev 2018:66:80–96. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravi M, Stevens JS, Michopoulos V. Neuroendocrine pathways underlying risk and resilience to PTSD in women. Front Neuroendocrinol 2019:55. Doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Milad MR, Goldstein JM, Orr SP, Wedig MM, Klibanski A, Pitman RK, Rauch SL. Fear conditioning and extinction: influence of sex and menstrual cycle in healthy humans. Behav Neurosci 2006:120(6):1196. Doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1196.17201462 ** This is the first study to examine the influence of menstrual cycle phase on fear conditioning and extinction.

- 37.Lonsdorf TB, Haaker J, Schümann D, Sommer T, Bayer J, Brassen S, Bunzeck N, Gamer M, Kalisch R. Sex differences in conditioned stimulus discrimination during context-dependent fear learning and its retrieval in humans: the role of biological sex, contraceptives and menstrual cycle phases. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015:40(6):368. Doi: 10.1503/140336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glover EM, Mercer KB, Norrholm SD, Davis M, Duncan E, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Jovanovic T. Inhibition of fear is differentially associated with cycling estrogen levels in women. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2013:38(5):341. Doi: 10.1503/jpn.120129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milad MR, Zeidan MA, Contero A, Pitman RK, Klibanski A, Rauch SL, Goldstein JM. The influence of gonadal hormones on conditioned fear extinction in healthy humans. Neurosci 2010:168(3):652–8. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Graham BM. Estradiol is associated with altered cognitive and physiological responses during fear conditioning and extinction in healthy and spider phobic women. Behav Neurosci 2016:130(6):614. Doi: 10.1037/bne0000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pineles SL, Nillni YI, King MW, Patton SC, Bauer MR, Mostoufi SM, Gerber MR, Hauger R, Resick PA, Rasmusson AM, Orr SP. Extinction retention and the menstrual cycle: Different associations for women with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2016:125(3):349. Doi: 10.1037/abn0000138.26866677 ** This study was the first to show that trauma-exposed healthy women and trauma-exposed women with PTSD show opposite menstrual cycle effects on extinction recall.

- 42.Glover EM, Jovanovic T, Mercer KB, Kerley K, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Norrholm SD. Estrogen levels are associated with extinction deficits in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2012:72(1):19–24. Doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasmusson AM, Pinna G, Paliwal P, Weisman D, Gottschalk C, Charney D, Krystal J, Guidotti A. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2006:60(7):704–13. Doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pineles SL, Nillni YI, Pinna G, Irvine J, Webb A, Hall KA, Hauger R, Miller MW, Resick PA, Orr SP, Rasmusson AM. PTSD in women is associated with a block in conversion of progesterone to the GABAergic neurosteroids allopregnanolone and pregnanolone measured in plasma. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018:93:133–41. Doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pineles SL, Nillni YI, Pinna G, Webb A, Hall KA, Fonda JR, Irvine J, King MW, Hauger RL, Resick PA, Orr SP. Associations between PTSD-Related extinction retention deficits in women and plasma steroids that modulate brain GABAA and NMDA receptor activity. Neurobiology of Stress 2020:13:100225. Doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rasmusson AM, Pineles SL. Neurotransmitter, peptide, and steroid hormone abnormalities in PTSD: biological endophenotypes relevant to treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2018:20(7):52. Doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0908-9.30019147 * The review summarizes the literature on PTSD-related neurotransmitter, peptide, and neurohormone abnormalities that may be relevant to the development of novel psychopharmacological treatments for PTSD.

- 47.Rasmusson AM, Marx CE, Pineles SL, Locci A, Scioli-Salter ER, Nillni YI, Liang JJ, Pinna G. Neuroactive steroids and PTSD treatment. Neurosci Lett 2017:649:156–63. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lebron-Milad K, Milad MR. Sex differences, gonadal hormones and the fear extinction network: implications for anxiety disorders. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 2012:2(1):3. Doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ressler KJ, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Jovanovic T, Mahan A, Kerley K, Norrholm SD, Kilaru V, Smith AK, Myers AJ, Ramirez M. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor. Nature 2011:470(7335):492–7. Doi: 10.1038/nature09856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitev YA, Darwish M, Wolf SS, Holsboer F, Almeida OF, Patchev VK. Gender differences in the regulation of 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in rat brain and sensitivity to neurosteroid-mediated stress protection. Neurosci 2003:120(2):541–9. Doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pilver CE, Levy BR, Libby DJ, Desai RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma characteristics are correlates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health 2001:14:383–393. Doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bixo M, Ekberg K, Poromaa IS, Hirschberg AL, Jonasson AF, Andréen L, Timby E, Wulff M, Ehrenborg A, Bäckström T. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with the GABAA receptor modulating steroid antagonist Sepranolone (UC1010)—A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017:80:46–55. Doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vermeire S, Audenaert K, De Meester R, Vandermeulen E, Waelbers T, De Spiegeleer B, Eersels J, Dobbeleir A, Peremans K. Neuro-imaging the serotonin 2A receptor as a valid biomarker for canine behavioural disorders. Res Vet Sci 2011:91(3):465–72. Doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosell DR, Thompson JL, Slifstein M, Xu X, Frankle WG, New AS, Goodman M, Weinstein SR, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, Siever LJ. Increased serotonin 2A receptor availability in the orbitofrontal cortex of physically aggressive personality disordered patients. Biol Psychiatry 2010:67(12):1154–62. Doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casilla-Lennon MM, Meltzer-Brody S, Steiner AZ. The effect of antidepressants on fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016:215(3):314-e1. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasmusson AM, Vythilingam M, Morgan CA. The neuroendocrinology of posttraumatic stress disorder: new directions. CNS spectrums 2003:8(9):651–67. Doi: 10.1017/S1092852900008841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marván ML, Cortés-Iniestra S. Women’s beliefs about the prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and biases in recall of premenstrual changes. Health Psychol 2001:20(4):276. Doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shirtcliff EA, Reavis R, Overman WH, Granger DA. Measurement of gonadal hormones in dried blood spots versus serum: verification of menstrual cycle phase. Horm Behav 2001: (4):258–66. Doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schmalenberger KM, Tauseef HA., Barone JC, Owen SA, Lieberman L, Jarczok MN, et al. How to study the menstrual cycle: Practical tools and recommendations. Psychoneuroendocrinology in press. * This paper outlines methodological recommendation for studying menstrual cycle phase effects on outcomes.

- 60.Graham BM, Ash C, Den ML. High endogenous estradiol is associated with enhanced cognitive emotion regulation of physiological conditioned fear responses in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017:80:7–14. Doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li SH, Denson TF, Graham BM. Women With Generalized Anxiety Disorder Show Increased Repetitive Negative Thinking During the Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle. Clin Psychol Sci 2020. Doi: 10.1177/2167702620929635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Contraceptive Use. Source: Key Statistics from the National Survey of Family Growth (data 2011–2015). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/contraceptive.htm