Abstract

Flexible electrodes that allow electrical conductance to be maintained during mechanical deformation are required for the development of wearable electronics. However, flexible electrodes based on metal thin-films on elastomeric substrates can suffer from complete and unexpected electrical disconnection after the onset of mechanical fracture across the metal. Here we show that the strain-resilient electrical performance of thin-film metal electrodes under multimodal deformation can be enhanced by using a two-dimensional (2D) interlayer. Insertion of atomically-thin interlayers — graphene, molybdenum disulfide, or hexagonal boron nitride — induce continuous in-plane crack deflection in thin-film metal electrodes. This leads to unique electrical characteristics (termed electrical ductility) in which electrical resistance gradually increases with strain, creating extended regions of stable resistance. Our 2D-interlayer electrodes can maintain a low electrical resistance beyond a strain in which conventional metal electrodes would completely disconnect. We use the approach to create a flexible electroluminescent light emitting device with an augmented strain-resilient electrical functionality and an early-damage diagnosis capability.

Flexible electrodes are central to the development of flexible electronic devices, including implantable medical sensors, deformable displays, and wearable devices for monitoring cognitive or physical performance1–6. However, the implementation of practical flexible electronics has been hampered by a lack of robust flexible electrodes that can ensure reliable electrical conduction between the active electrical components under various deformation7. Ideally, flexible electrical conductors should offer both electrical conductivity and mechanical flexibility. Currently, electrodes based on thin metal films deposited on compliant substrates are commonly used due to their intrinsically high conductivity (>106 S m−1), ease of integration using conventional manufacturing processes, cost-effectiveness, and scalability8,9. Thin gold films on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), for example, enable flexible electronics applications such as sensitive electronic skins10, flexible interconnectors between active components on rigid-islands11, biocompatible microelectrodes for neural interfaces12,13, and soft robotics14. However, most electrodes based on thin-metal films fracture at small strains (<2%) with low cycles of fatigue failure15,16. Metal electrodes on flexible substrates often suffer from rapid surface crack development, and eventual interface fracture failure by debonding from the substrate. These sudden and unexpected mechanical fractures lead to electrical failure17, severely reducing the functional lifespan of flexible devices under various deformations.

After the onset of fracture in metal films, two modes of crack extension are possible: out-of-plane cracking where cracks extend vertically toward the interface, and in-plane cracking where cracks occur transversely across the film18. Existing approaches to increasing electrode resilience focus on perturbing out-of-plane cracking19–22, and the contribution of in-plane cracking has rarely been investigated. In-plane crack extension is the primary cause of catastrophic electrical failure due to complete disconnection across the entire film, which results in termination of electrical conductivity15. Thus, the ability to modify in-plane crack growth in large-area flexible metal electrodes offers a potential route to augment strain-resilient electrical functionality and the lifespan of flexible metal-based devices.

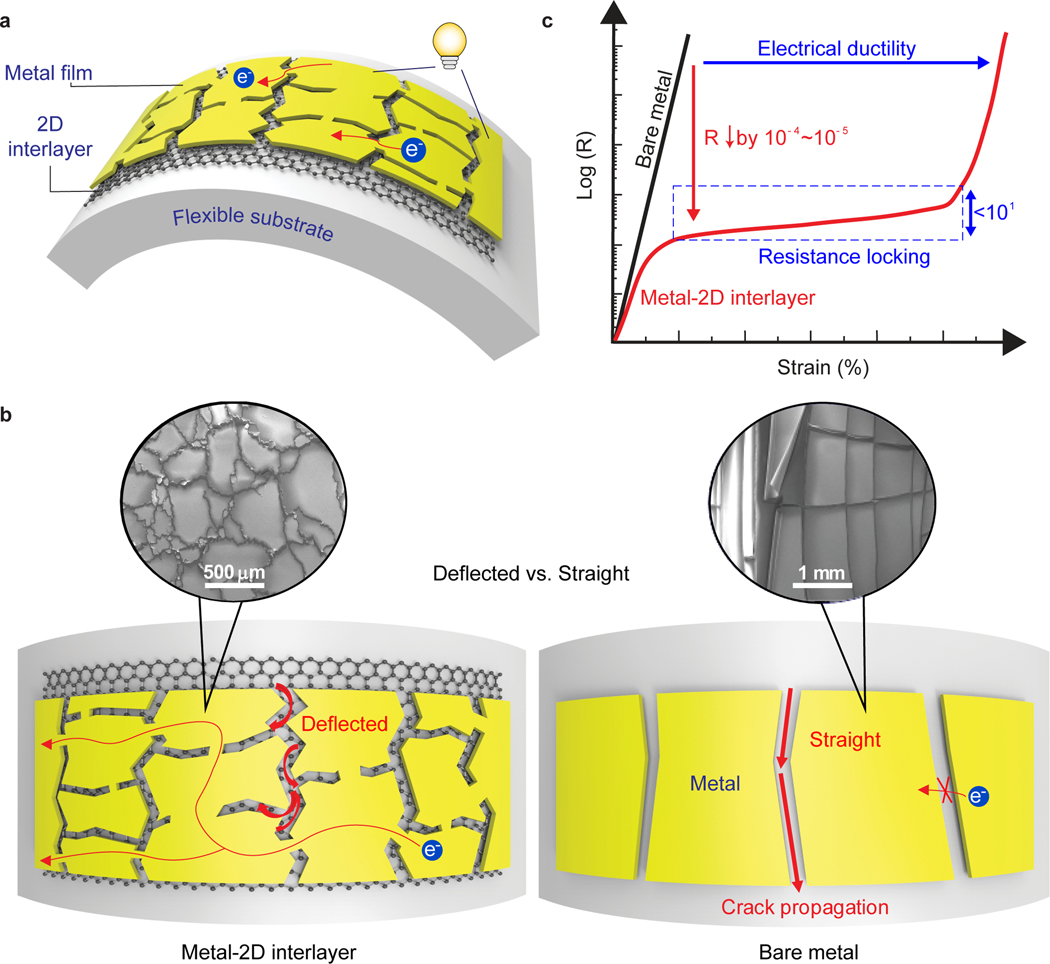

In this Article, we show that insertion of an atomically-thin interlayer of graphene, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) or hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) between a thin metal film and flexible elastomeric substrate can modulate in-plane facture modes and effectively resist crack extension, substantially improving the electrical robustness of gold and copper metal electrodes against mechanical deformation (Fig. 1a). In the presence of a 2D-interlayer, in-plane crack development of the metal thin film under bending is altered, leading to channelling and a large degree of irregular deflected cracks (left, Fig. 1b); with a conventional bare metal-based electrode, debonding and straight cracks occur (right, Fig. 1b). The metal-2D electrodes exhibit a slow increase in electrical resistance over a larger strain range, in contrast to conventional metal-based systems in which sudden rapid increases in electrical resistance occur followed eventually by abrupt electrical disconnection due to straight crack development15. This enables an elongation of the electrical conductance of the metal film with strain, which we term electrical ductility (in analogy to mechanical ductility, which describes elongation of deformation with strain), as well as resistance locking characteristics (Fig. 1c). Our metal-2D electrodes can thus maintain orders-of-magnitude lower electrical resistance under deformation than conventional electrodes. We illustrate the capabilities of these interconnects by using them to create a flexible electroluminescent light emitting device that exhibits a gradual decrease in luminous power with increasing applied strain.

Fig. 1. Flexible metal electrode achieved by insertion of an interlayer of 2D materials.

a, Schematic illustration of a flexible metal electrode with an interlayer of atomically-thin 2D material. b, Schematic illustrations (top view) of different crack propagation modes on a metal-2D interlayer electrode (left), and on a bare thin metal film electrode (right). Inset SEM images show dominant fracture modes of deflected/multiple cracking (left) compared to straight/debonding cracking (right). c, Conceptual plots of change in resistances (R) as a function of applied strain on bare metal electrodes (black) and on metal-2D interlayer electrodes (red).

In plane mechanical fracture modulation enabled by 2D interlayers

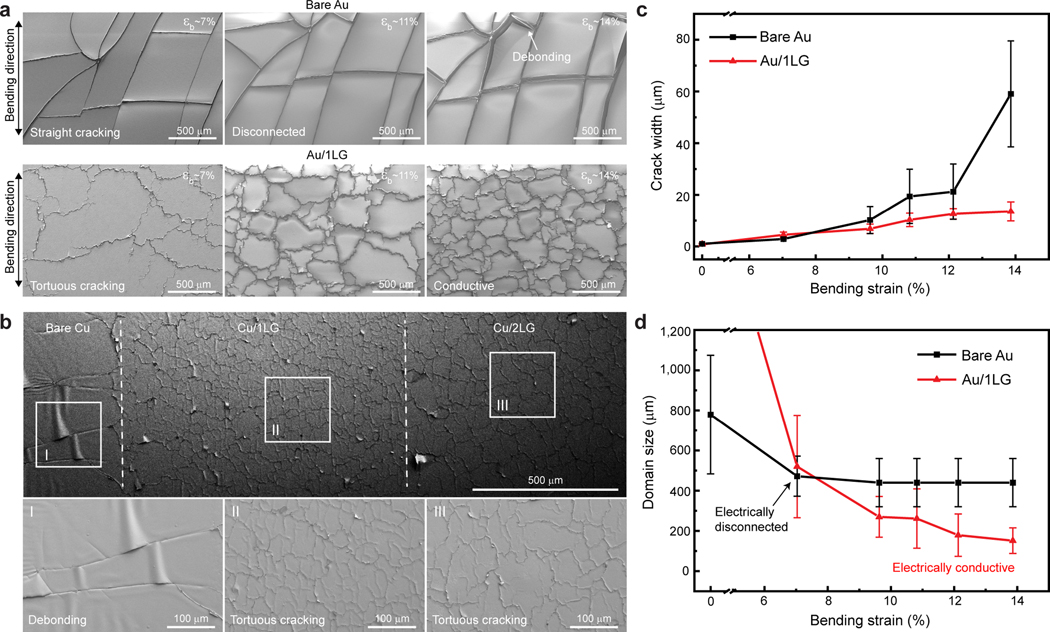

To study the effect of 2D-interlayer on the sustainability of electrical conductance under mechanical fracture in flexible thin-film metal electrodes, we first characterized fracture surfaces of gold (Au) thin films (with an adhesion layer of titanium, Ti) on PDMS substrates with and without a graphene-interlayer (see Methods). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of fracture surfaces on a conventional thin film Au/Ti electrode (Bare Au, Fig. 2a top) and a single-layer graphene integrated Au/Ti electrode (Au/1LG, Fig. 2a bottom) revealed distinct fracture behaviours. On bare Au electrodes, most cracks propagated along straight paths (Supplementary Video 1) eventually resulting in debonding fracture failure (Fig. 2a top). In contrast, on Au/1LG electrodes, cracks propagated with local-zigzag fluctuations (Fig. 2a bottom and Supplementary Video 2) along the crack growth direction. Crack deflection angles were between 35°–66° (Supplementary Fig. 1), analogous to the crack kinking angles under mixed-mode loading23. Continuous crack deflections led to tortuous crack extension, resulting in the formation of polygonal interconnected domains. To verify the capability to alter fracture modes with 2D-interlayer, we also investigated fracture behaviours of a copper (Cu) with the adhesion layer of Ti (Bare Cu), another commonly used metal in flexible electronics, with bare Cu, Cu/1LG, and Cu/2LG areas (Fig. 2b). Straight crack propagation appeared on bare Cu areas resulting in the film debonding, while multiple cracks with deflected crack edges developed on Cu/1LG and Cu/2LG areas. These distinct in-plane fracture modes were only apparent with the presence of underlying graphene-interlayer in metal-2D electrodes regardless of the presence of Ti adhesion layer (Supplementary Fig. 2). Our results clearly suggest that the underlying 2D-interlayer plays a key role in modifying the dominant in-plane fracture behaviours of metal thin films.

Fig. 2. Fracture behaviours of thin film metal electrodes with 2D interlayers.

a, Crack progression at various bending strains (εb) in bare Au electrode (top) and Au/1LG electrode (bottom). A white arrow indicates Au film debonding from the PDMS substrate. b, Different fracture behaviours observed in bare Cu (I), Cu/1LG (II), and Cu/2LG (III) areas partitioned in one Cu-based electrode. c, Crack width on bare Au and Au/1LG electrodes as a function of bending stain. d, Fracture domain size on bare Au and Au/1LG electrodes as a function of bending stain.

Next, we quantitatively analysed crack growth upon bending and investigated the resultant sustainability of electrical conductance of metal electrodes. First, Figure 2c shows changes in crack width as a function of bending strain for both bare Au and Au/1LG electrodes. Crack width on the Au/1LG electrode gradually increased with strain whereas crack width on the bare Au electrode rapidly accelerated at high bending strains (Fig. 2c). Second, as the strain increased, we observed larger isolated-domains on bare Au compared to much smaller fracture domains with deflected crack edges on the Au/1LG electrode (Fig. 2d). The average saturated fracture domain size of Au/1LG electrodes was about (Supplementary Fig. 3). Straight cracking behaviour on the bare Au resulted in large isolated-domains while continuous deflected cracking on Au/1LG created much smaller fracture domains. Third, simultaneous monitoring of electrical conductance beyond the bending strain (~7%) where the bare Au electrode lost its electrical conductance showed that the Au/1LG electrode was still electrically connected (Fig. 2d). We attribute the resultant sustainability of electrical conductance to the presence of progressive cracking and crack bridging induced by 2D-interlayers. Smaller domains with many deflected, narrow-width cracks resulted from a hybrid of ductile (zig-zag) and brittle (straight) fracture behaviours on the Au/1LG are more conducive to creating effective conductive paths across the electrode via crack bridging24 between adjacent domains (Supplementary Fig. 4), which might be more effective with more intrinsically ductile metals. Moreover, early saturation of the domain size on bare Au suggests there was no further strain energy dissipation by cracking, whereas continuous decrease in the domain size of Au/1LG implies prolonged energy dissipation by progressive cracking. Thus, progressive tortuous cracking behaviour with crack bridging can contribute to maintaining the electrical conductivity beyond a failure strain where the bare Au electrode showed a complete electrical disconnection.

To unveil the underlying mechanism for unique in-plane fracture behaviours with 2D-interlayers, we carried out detailed characterizations of grain sizes, fracture surfaces and interfaces. First, we characterized grain sizes of Au thin film with and without graphene, and of a single graphene via high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Note: Grain size and metal film quality characterization). There was no strong/direct correlation between the grain size and fracture domain size where the measured grain sizes of bare Au ( and Au/1LG ( are both at least three orders-of-magnitude smaller than the average fracture domain size (~, Fig. 2d) of Au/1LG electrodes and the grain size of graphene () is at least an order-of-magnitude smaller than the average fracture domain. Next, we observed that heterogeneous buckle-network spontaneously formed on as-prepared Au/1LG electrodes, which was confirmed by cross-section SEM images and topographic atomic force microscopy scans (Supplementary Fig. 6). We observed uniform deposited Au film (~202 nm) over graphene on both flat and buckle-network areas on as-prepared Au/1LG electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 7). The decrease in the interfacial adhesion by van der Waals interaction of 2D-interlayers, which is confirmed by molecular dynamic (MD) simulation (Supplementary Fig. 8) and experimental adhesion test (Supplementary Table 1), as well as increase in film/substrate modulus ratio by 2D-interlayers (Supplementary Fig. 8) promote the formation of spontaneous buckle-network after the metal deposition process (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Note: Modification of mechanical properties of the metal film via the insertion of graphene-interlayers). We note that our 2D-interlayer engineering approach achieves the desired adhesion regime where we can improve the mechanical robustness and prevent a catastrophic fracture failure mode of film debonding from the substrate under strain.

During bending, multiple cracks preferentially initiated at the buckle crests and propagated along the heterogeneous buckle-network on Au/1LG electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 10). Our MD simulation results showed cracks occur first on the top metal thin film and the underlying graphene fractures subsequently at a higher strain (Supplementary Fig. 11). The fracture of underlying graphene along the metal crack paths was characterized via scanning electron microscopy imaging during bending and the after removal of the top Au/Ti layer (Supplementary Fig. 12). Intersection and interaction between multiple cracks further delayed the complete fracture across the entire metal surface (Supplementary Fig. 10), resulting in macroscopically ductile fractures. In contrast, cracks on bare Au electrodes propagated straight perpendicular to the bending direction without perturbation by densely packed homogeneous conformal wrinkles prominent on thinner bare Au electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 13), and resulted in macroscopically brittle fractures25 (Supplementary Fig. 14). We observed the crack deflection and the resultant tortuous fracture behaviours on Au/2LG electrodes with different thicknesses where it showed a higher degree of crack deflection and the resultant smaller fracture domain sizes on the thicker Au/2LG relative to the thinner Au/2LG electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 15), analogous to the length scale effect of film thickness dependent fracture behaviours26,27. Moreover, our MD simulation results (Supplementary Fig. 9) showed our in-plane crack deflection mechanism (i.e., buckle-guided fracture mechanism) is caused by the buckle-network induced by 2D-interlayer. Our results indicate that discrete buckles can effectively guide crack paths by providing low-energy stress-relief routes due to the localized built-in strain at the crest (buckle-guided fracture) and further perturb in-plane crack development (Supplementary Note: Crack growth perturbation by buckles vs. conformal wrinkles). Altogether, the 2D-interlayer not only enhances intrinsic toughness (Supplementary Fig. 8), which is effective to resist fracture development by absorbing energy under strain, but also introduces extrinsic toughening mechanisms of crack perturbation/deflection that is effective to reduce the stress/strain experienced at the crack tip. The continuous crack perturbation with crack bridging led by 2D-interlayer is further effective in resisting crack extension to a complete disconnection, allowing the sustainability of electrical conductance of flexible metal electrodes even with the presence of progressive fractures as opposed to the immediate loss of electrical conductance after the onset of surface fracture in conventional metal electrodes.

Strain resilient electrical functionality

To further investigate how the unique fracture characteristics imposed by 2D-interlayers affect the electrical behaviours, we characterized the electrical resistance as a function of bending strain. Electrical resistance of metal-2D interlayer electrodes increased gradually upon bending (electrical ductility) as opposed to the abrupt, many orders-of-magnitude increase of resistance observed in bare metal electrodes (Fig. 3a). Moreover, insertion of additional 2D-interlayers further reduced the magnitude of resistance change with strain and delayed complete electrical failure of electrodes. At ~7% strain (Fig. 3a), where the resistance of bare Au electrodes increased more than five orders-of-magnitude (~100 kΩ), the Au/1LG maintained 104 times lower electrical resistance (~10 Ω, blue), and the Au/4LG further showed 105 times lower electrical resistance (~few Ω, green) than that of the bare Au electrodes. Furthermore, the electrical failure strain of Au/4LG electrode (εelectrical failure ~24%, green curve) showed about 400% of the electrical failure strain of bare Au electrode (εelectrical failure ~6%, red curve). Electrical failure strains dependence on the number of 2D-interlayers is summarized in Figure 3b. This dependence of electrical failure strain on the number of 2D-interlayers is also apparent on Cu-based electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 16). The transformation from abrupt to gradual increase in resistance due to 2D-interlayers is analogous to brittle-to-ductile transition of mechanical properties due to temperature. In particular, the extended plateau region with added 2D-interlayer showcases enhanced ‘plasticity’ of resistance, allowing resistance locking with extended regions of stable resistance. This unique strain-resilient electrical functionality is attributed to 2D-interlayer induced fracture behaviours of continuous crack deflection and crack bridging which maintain conductivity at high strain.

Fig. 3. Strain-resilient electrical performance with 2D interlayers.

a, Electrically ductile behaviours of multilayer-graphene integrated electrodes in response to bending deformation. Scale bar, 10 mm. b, Dependence of electrical failure strains under bending on the number of 2D-interlayers. c, Electrically ductile behaviours of multilayer-graphene integrated electrodes in response to twist deformation. Scale bar, 10 mm. d, Fatigue test of the Au/2LG electrode upon repeated bending strain (εb ~11%) up to 10,000 cycles.

To capture the mechanism behind strain-resilient electrical functionality (electrical ductility), we employed the strain-dependent electrical resistance analytical model, which is a function of fracture state with the assumption of the existence of effective conductive paths across cracks28. The model relates the progressive increase in the number of cracks to the normalized electrical resistance change:

| (1) |

where is the electrical resistance of the crack-free surface, R is the electrical resistance with the number of cracks () in the material at a given strain, is the saturated number of cracks, is a scaling factor which relates the crack opening to the applied strain, and is an electrical ductility parameter which is a function of several quantities (Supplementary Note: Analytical model of electrical ductility). We utilized the model with our experimental inputs to reproduce the experimental electrical ductility behaviour (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 17). Based on the fit, we observed the electrical ductility parameter (C) increases as the number of 2D-interlayers increases. The C parameter for Au/4LG increased more than an order-of-magnitude compared to that of bare Au (Supplementary Fig. 17). The increase in the value of C indicates that the number of cracks that the materials can withstand before failure becomes higher as 2D-interlayers are added (Supplementary Note: Analytical model of electrical ductility). Our observation that larger fracture domains on the Cu/2LG areas compared to Cu/1LG areas at a given strain (Fig. 2b) along with the strain-dependent domain size characteristics (Fig. 2d) suggests delayed crack saturation and more gradual crack development as the number of 2D-interlayers increases, which eventually results in higher electrical ductility (increase in C). Insertion of additional 2D-interlayers increases the intrinsic fracture toughness (Supplementary Fig. 8) resulting in the delayed crack extension by absorbing more strain energy as the number of 2D-interlayer increases and further reduces the magnitude of resistance change with strain compared to bare metals. We also note that there could be minor contributing factors including an additional energy dissipation resulting from a potential interlayer-sliding between 2D-interlayers29 under strain. We observed de-adhesion was preferably occurred between graphene/graphene interface on Au/2LG electrode after the experimental adhesion test (Supplementary Fig. 18), which can reduce the effective strain energy via interfacial sliding when under strain.

To demonstrate the robustness of metal-2D interlayer electrodes to deformation modes beyond bending, we characterized electrical behaviour under twisting and fatigue cycling. Consistent with the bending results, metal-2D interlayer electrodes during twisting (Fig. 3c) showed enhanced strain-resilient electrical functionality dependent on the number of 2D-interlayers. Bare Au resistance abruptly increased by three orders-of-magnitude at a 40° twist angle. However, the resistance of Au/1LG electrodes increased by less than one order-of-magnitude at twist angles up to 90°. Furthermore, Au/4LG electrode tolerated twist angles up to 160° with resistance locking and remaining in the 10s of Ω range, representing an approximately 400% twist resilient performance relative to the bare Au. Next, we investigated robustness of metal-2D electrodes to fatigue. We measured electrical resistance of Au/2LG electrodes while subjecting the electrode to 10,000 cycles of bending to half of the electrical failure strain (εb ~11%) as shown in Figure 3d. Our Au/2LG electrode showed reliable electrical performance with resistance increased by twice of its initial resistance remaining in the ~10s Ω range over all cycles.

In order to explore the generality of our 2D-interlayer approach, we used alternative 2D-interlayers including chemical vapour deposition synthesized semiconducting MoS2 and insulating hBN. We observed a similar strain-resilient electrical behaviour (electrically ductility) which depended on the number of 2D-interlayers under bending. The electrical failure strain of Au/4L-MoS2 electrode exhibited more than 300%, and the electrical failure strain of Au/4L-hBN electrode showed more than 240% of the electrical failure strain of bare Au electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 16). Our analytical fit where the exponential decay model showed a good agreement to our experimental observation of various metal-2D electrodes up to 4 interlayers suggests the electrical failure strain is expected to be saturated above 7 interlayers (Supplementary Fig. 19). Moreover, there was no significant difference on the initial electrical resistance of as-prepared electrodes with various 2D-interlayers (Supplementary Fig. 20), indicating underlying 2D materials do not impact on the quality of the subsequent deposited metal films. These results indicate that high strength mechanical properties and the modulated adhesion offered by the 2D materials play a critical role on the strain-resilient electrical performance, not primarily due to the electrical conductivity difference from the underlying 2D-interlayers. In-plane fracture alteration led by the 2D-interlayer is the principal mechanism responsible for the strain-resilient electrical characteristic. We attribute different levels of enhancement of strain-resilient electrical functionality of Au/MoS2 and Au/hBN, compared to Au/Graphene, to different mechanical properties of 2D-interlayers, including reduced effective modulus and toughness30 as well as electrical conductivity. Overall results suggest that our 2D-interlayer approach can be used with a various combination of metals and 2D-atomic layers including mixed type of 2D materials which can broaden the general applicability of our 2D-interlayer approach.

Applications to flexible electronics

Finally, we applied our metal-2D interlayer approach to the conducting interconnector in a flexible electroluminescent light emitting device and measured strain-dependent luminous power (Supplementary Fig. 21) to demonstrate the utility of metal-2D interlayers in flexible electronics. The electromechanical robustness of our device allowed a high degree of multimodal deformation including bending (Fig. 4a) and twisting (Fig. 4b) without the low-cycle fatigue failure (Supplementary Fig. 22) which occurred with the conventional metal-based interconnectors (Supplementary Video 3). Bending strain dependent luminous power measurements on flexible light emitting device with a conventional metal-based interconnector showed a sudden drop in luminous power at low bending strains (Fig. 4c). In stark contrast, luminous power of a flexible light emitting device with a metal-2D interconnector gradually decreased as the applied strain increased. Moreover, the device failure strain, at which the flexible light emitting device becomes unreadable, increased more than 400% with the metal-2D interconnector (Fig. 4d). Enhancement of device failure strain agrees well with our previous results (Fig. 3) and substantiates the utility of our metal-2D interlayer approach in broad flexible electronics. In addition, gradual luminous power reduction can be used to diagnose the potential device failure. For instance, a 40%-decrease in luminous power of the device (Fig. 4c) can be taken as a pre-alert for partial maintenance or replacement. The unique features of our early failure diagnosis due to strain-resilient electrical functionality and augmented electrical performance under multimodal deformation could offer advanced electromechanical characteristics to the next-generation of wearable/flexible electronics including bio-implantable electrodes31 and human body sensor-network32 where the applications require not only bending, but also folding and twisting modes of deformation.

Fig. 4. Flexible light emitting device integrated with an electromechanically robust metal-2D interconnector.

a, Functionality of a flexible light emitting device integrated with an Au/2LG based-interconnector under bending deformation modes of tension (left) and compression (right). b, Device functionality under a twisting deformation mode. Scale bars, 2 cm. c, Normalized luminous power of flexible light emitting devices integrated with a conventional thin film metal and a metal-2D interconnector as a function of bending strain. d, Device failure strains with the conventional thin film metal interconnector and the metal-2D interconnector.

Conclusion

We have shown that a 2D-interlayer can improve the durability of electromechanical functionality of metal-based flexible electronics. The addition of an atomically-thin interlayer between a metal thin film and flexible substrate results in unique strain-resilient electrical characteristics — electrical ductility — through the modulation of in-plane fracture modes of metal thin-films from unperturbed straight fractures with brittle behaviour to progressive tortuous fractures with ductile behaviour via buckle-guided fracture mechanism. The 2D-interlayer electrodes maintain electrical conductivity beyond the failure strain of conventional metal electrodes and further augment the strain-resilient electrical performance with resistance locking characteristics. To illustrate the capabilities of our 2D-interlayer approach in flexible electronics, we created a flexible electroluminescent light emitting device integrated with metal-2D interlayers. The device exhibits strain-resilient electrical performance under a high degree of multimodal deformation and an early damage diagnosis capability. Our approach is not limited to specific combinations of metals and 2D materials, and could be incorporated into industrial applications that use multilayer-laminated structures for flexible and wearable electronics, including conformable and implantable bioelectrodes and foldable/rollable personal electronic devices.

Methods

Sample preparation

Single-layer graphene was synthesized on catalytic 25 μm-thick copper (Cu) foil (Alfa Aesar, MA) using our chemical vapour deposition (CVD) system (Rocky Mountain Vacuum Tech Inc., CO). CVD-grown single-layer graphene on Cu foil was directly stamped on a flexible elastomeric substrate of 4 mm-thick PDMS and immersed in ferric chloride (FeCl3) etchant solution (CE100, Transene Inc.) to etch away the Cu foil. For multilayer graphene-interlayers, we repeated this laminating transfer method multiple times to artificially stack graphene layers followed by a complete etching of Cu foil and multiple rinsing/cleaning steps with deionized water. The quality of transferred multilayer graphene was evaluated via two non-destructive optical characterization of UV-Vis and Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 23 and Supplementary Note: Characterization of multilayer configuration) to ensure there was no significant defects and chemical residues that may induce undesired fracture behaviours. Then, a 20 nm-thick adhesion layer of titanium and a 200 nm-thick gold layer were deposited on top of the transferred graphene on a PDMS substrate via the electron beam evaporation. We chose gold as it is one of the most widely used metals with high electrical conductivity. Samples were also fabricated with CVD-grown hBN on a 25-μm Cu foil purchased from Grolltex Inc. following the same sample preparation procedures for Au/hBN samples. CVD-grown MoS2 on a silicon oxide/silicon wafer was also used to fabricate Au/MoS2 samples following the same sample preparation procedures with a modification where MoS2 layers were transferred on PDMS substrates using the water-assisted lift-off transfer method33.

Characterization of fracture surfaces

To investigate fracture surfaces of both bare Au and Au/1LG electrodes, we recorded crack development upon bending strains in bare Au (Supplementary Video 1) and in Au/1LG (Supplementary Video 2) electrodes via optical microscope. Crack deflection angle was measured on fractured surfaces of Au/1LG electrodes from captured images of the fracture video. Statistical results (Supplementary Fig. 1) showed that crack deflection occurred between 35° and 66° with a mean of 52° and a standard deviation (SD) of 9.58° extracted by the Lorentzian fitting. We further conducted quasi-static bending test with environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM, FEI Quanta FEG 450 ESEM). The crack development in response to varying bending strain was qualitatively characterized (Fig. 2a and 2b, and Supplementary Figs. 2, 4, 10, 14, and 15) and quantitatively analysed (Fig. 2c and 2d). Twenty different cracks on both bare Au (Au/Ti) and Au/1LG (Au/Ti/1LG) electrodes were continuously monitored with an increase of bending strain (0–14%) to quantitatively analyse the crack width growth (Fig. 2c). Crack width in Figure 2c is defined as the average distance separating adjacent crack domains. The average domain size (Fig. 2d) was estimated as the root mean square of the diagonal lengths of all the domains34 presented in ESEM images by using image analysis tools (e.g., ImageJ). We note that there were a few cracks/domains pre-existed on as-prepared (εb=0) bare Au electrodes due to the residual stress after metal deposition (Fig. 2d). We have analysed fracture domain size development with strain on Au/1LG electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Control experiments without a Ti adhesion layer further verified that the 2D-interlayer plays a key role of modulating in-plane facture modes of metals (Supplementary Fig. 2). A combination of high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope and focused ion beam (FEI Helios 600i) sectioning was used to characterize the cross section of buckles spontaneously formed on the Au/1LG electrodes (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Atomic force microscopy (Asylum MFP-3D AFM) was used for topography scans (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 13).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

We performed MD simulation to theoretically explore the mechanical properties of bare metal and metal-2D-interlayers upon bending. Although MD is limited to nanoscale domains due to the computational complexity, MD simulations have shown the ability to produce and explain the mechanical properties of polycrystalline graphene in a good agreement with experiment even when the domain length scale in MD is much smaller than the one in experiment35,36. The simulation model structures of Gold/Graphene/PDMS electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 8) are about 13.2 nm long in x-direction and 7.1 nm wide in y-direction. Polycrystalline graphene with different grain sizes is constructed and used for the graphene-interlayers inserted between gold and PDMS. The initial amorphous PDMS structure with height of 7.2 nm is generated with a density of 0.92 g cc-1. The interaction between C/C atoms in graphene is described by an Adaptive Intermolecular Reactive Empirical Bond Order (AIREBO) potential37. The interaction between Au/Au atoms is described by a ReaxFF reactive forcefield38. The interaction between Mo/S atoms is described by the reactive many-body potential39. For the interaction between C/Au atoms, a 6–12 Lennard-Jones potential is used with ε of 0.01273 eV and σ of 2.9943 Å. For the interactions between atoms in the PDMS, the Condensed-phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies (COMPASS) potential is employed40. The COMPASS potential was optimized from ab-initio results and has been used for the investigation of mechanical and thermal properties of PDMS. All MD simulations were performed using the LAMMPS package. The Velocity-Verlet algorithm was used to integrate the equations of motion. A time step of 0.1 fs was chosen. Periodic boundary conditions were applied along the y-axis (transverse direction) and free boundary conditions were applied along the other two directions. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat was employed to control the temperature. All molecular systems were relaxed with NPT (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature) ensemble for 200 ps. Constant pressure (1 atm) and temperature (300 K) were employed during this process. After the NPT relaxation, the system was relaxed with an NVE (constant volume without a thermostat) ensemble for 200 ps. The total energy and temperature of the whole system were monitored during this stage to ensure that the system reached the equilibrium state. At equilibrium state, a stable structure of Gold/Graphene/PDMS electrode was obtained as shown in Supplementary Figure 8. First, we looked into the adhesion energy of Au/PDMS (interaction energy between Au and PDMS) and Au/Ti/PDMS (interaction energy between Ti and PDMS), and Au/Ti/graphene/PDMS (interaction between Au/Ti/graphene and PDMS). The adhesion energy is calculated by Equation (2)41,

| (2) |

where is the total energy of the isolated gold, is the total energy of the isolated PDMS with or without graphene, is the total energy of the relaxed Gold–PDMS with or without graphene, and A is the area of the interface. All the energies are calculated by averaging the total energy over 50,000 steps after steady state is reached. The overall adhesion energy results are plotted in Supplementary Figure 8. Next, the bending test on the electrode was performed under deformation-control method which is widely used to investigate the bending deformation of 1D and 2D materials42. The strain increment is applied to the structure every 10,000 steps. Stress-strain curves obtained from this simulation and toughness which is the area under the stress-strain curve are plotted in Supplementary Figure 8.

Electrical characterization

In order to investigate the electrical behaviour of bare metal and metal-2D electrodes, we measured electrical resistance as a function of bending strain (Fig. 3a). Bending strain was applied to electrodes by using our homemade linear translation stage (an inset of Fig. 3a) with a change of the translation distance43. An increase in translation distance leads to a decrease in the radius of curvature. The radius of curvature (r) was determined by image analysis (via ImageJ) and the resultant bending strain was determined based on the analytical formula of εb ~ t/2r44, where t is a total thickness. We defined an electrical failure strain (εelectrical failure) as the strain at which resistance increased by 3 orders-of-magnitude (>103 Ω) relative to the unstrained resistance value (i.e., initial resistance R0~4 Ω for all electrodes). The three orders-of-magnitude increase was chosen because this is when the resistance of graphene, which is initially in the range of a few kΩ, might primarily contribute to the overall resistance, indicating the metal layer has failed. We note that when the applied bending strain is less than 2%, the increase in electrical resistance is negligible, ranging between 0.01 and 0.04 Ω. Change in electrical resistance is normalized by R0 when there was no applied bending strain. We analysed electrical failure strain from more than 5 sets of Au-graphene electrodes (Fig. 3b). Electrical behaviours of Cu-graphene interlayers, Au-MoS2 interlayers, and Au-hBN interlayers electrodes were also characterized under bending using the same method (Supplementary Fig. 16). Electrical behaviours under twist deformation were characterized by measuring electrical resistance during twisting with our homemade twisting stage (an inset of Fig. 3c). Lastly, we used an automatic linear translation stage (Thorlabs Inc.) to investigate mechanical robustness under cyclic mechanical loading. Electrical resistance of the Au/2LG electrode was monitored as a function of the number of bending-relaxation cycles up to 10,000 cycles. Displacement was applied with a maximum velocity of 2.4 mm s−1 and the acceleration of 1.5 mm s-2.

Luminous power measurement

Flexible electroluminescent light emitting layer consists of a large monolithic sheet of electroluminescent phosphor layer sandwiched by two dielectric layers of flexible polyvinyl chloride (PVC) polymer between top and bottom electrodes with a total thickness of 500 μm. Metal-2D interconnector layer is conformally assembled on top of the flexible light emitting layer (Fig. 4a,b, and Supplementary Fig. 21) where both components deform together under bending. We note that our main focus of this demonstration was to show the electromechanical robustness of the interconnector instead of the light emitting layer itself. To demonstrate electromechanical robustness of our metal-2D interconnector, the interconnector layer was purposely designed to have a thicker substrate (4 mm) to induce a higher strain compared to the light emitting layer (0.5 mm) upon bending. We measured luminous power of electroluminescent, flexible light emitting devices equipped a conventional thin film metal based interconnector and a metal-2D-interlalyer based interconnector as a function of the bending strain as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 21. Normal force was exerted on one end of the mounted flexible light emitting device to induce bending deformation. A photodiode power sensor (Thorlabs, S120C and PM100USB) was placed on top of the fixed area (on the opposite end of the mounted flexible light emitting device) to minimize any bending-induced fluctuation of luminous power during the measurement. The measured luminous power during bending was normalized by the unstrained luminous power value.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge support from NSF (MRSEC DMR-1720633, ECCS-1935775, DMR-1708852, and CMMI-1554019), AFOSR (FA2386-17-1-4071), NASA ECF (NNX16AR56G), ONR YIP (N00014-17-1-2830), and LLNL (B622092). C.C. acknowledges support from NASA Space Technology Research Fellow grant no. 80NSSC17K0149. The simulations were performed using the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) (supported by NSF Grant No. OCI1053575), Blue Waters (supported by NSF awards OCI-0725070, ACI-1238993 and the state of Illinois, and as of December, 2019, supported by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency), and Frontera computing project at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (supported by NSF Grant No. OAC-1818253). This research was primarily supported by the NSF through the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Materials Research Science and Engineering Center DMR-1720633.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S. Nam.

References

- 1.Gao W, Ota H, Kiriya D, Takei K. & Javey A. Flexible Electronics toward Wearable Sensing. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 523–533 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinwande D, Petrone N. & Hone J. Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 5678 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong G. & Lieber CM Novel electrode technologies for neural recordings. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 330–345 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray TR et al. Bio-integrated wearable systems: A comprehensive review. Chem. Rev. 119, 5461–5533 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang C, Lee C. & Suh K. Recent Advances in Flexible Sensors for Wearable and Implantable Devices. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 130, 1429–1441 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh A. et al. A soft, wearable microfluidic device for the capture, storage, and colorimetric sensing of sweat. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 366ra165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson AP, Minev I, Graz IM & Lacour SP Microstructured silicone substrate for printable and stretchable metallic films. Langmuir 27, 4279–4284 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan A. et al. Flexible electronics: The next ubiquitous platform. Proc. IEEE 100, 1486–1517 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graudejus O, Go P. & Wagner S. Controlling the Morphology of Gold Films on Poly(dimethysiloxane). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 1927–1933 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerratt AP, Michaud HO & Lacour SP Elastomeric electronic skin for prosthetic tactile sensation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 2287–2295 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JA, Someya T. & Huang Y. Materials and mechanics for stretchable electronics. Science 327, 1603–1607 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decataldo F. et al. Stretchable Low Impedance Electrodes for Bioelectronic Recording from Small Peripheral Nerves. Sci. Rep. 9, 10598 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song E. et al. Flexible electronic/optoelectronic microsystems with scalable designs for chronic biointegration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 15398–15406 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu N. & Kim D. Flexible and Stretchable Electronics Paving the Way for Soft Robotics. Soft Robot. 1, 53–62 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacour SP, Wagner S, Huang Z. & Suo Z. Stretchable gold conductors on elastomeric substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 2404–2406 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu N, Wang X, Suo Z. & Vlassak J. Metal films on polymer substrates stretched beyond 50%. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 221909 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baëtens T, Pallecchi E, Thomy V. & Arscott S. Cracking effects in squashable and stretchable thin metal films on PDMS for flexible microsystems and electronics. Sci Rep 8, 9492 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beuth JL Cracking of thin bonded films in residual tension. Int. J. Solids Struct. 29, 1657–1675 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Cheng Q. & Tang Z. Layered nanocomposites inspired by the structure and mechanical properties of nacre. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1111–1129 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin Z, Hannard F. & Barthelat F. Impact-resistant nacre-like transparent materials. Science 364, 1260–1263 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y. et al. Strengthening effect of single-atomic-layer graphene in metal-graphene nanolayered composites. Nat. Commun. 4, 2114 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh SH, Ryu S. & Han SM Role of Graphene in Reducing Fatigue Damage in Cu/Gr Nanolayered Composite. Nano Lett. 17, 4740–4745 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchinson JW & Suo Z. Mixed Mode Cracking in Layered Materials. Adv. Appl. Mech. 29, 63–191 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruzic JJ, Nalla RK, Kinney JH & Ritchie RO Crack blunting, crack bridging and resistance-curve fracture mechanics in dentin : effect of hydration. Biomaterials 24, 5209–5221 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chowdhury P. & Sehitoglu H. Mechanisms of fatigue crack growth - A critical digest of theoretical developments. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 39, 652–674 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh YD et al. Random nanocrack, assisted metal nanowire-bundled network fabrication for a highly flexible and transparent conductor. RSC Adv. 6, 57434–57440 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam KH, Park IH & Ko SH Patterning by controlled cracking. Nature 485, 221–224 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leterrier Y, Pinyol A, Rougier L, Waller JH & Mnson JAE Electrofragmentation modeling of conductive coatings on polymer substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 113508 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, Ma T, Erdemir A. & Li Q. Tribology of two-dimensional materials: From mechanisms to modulating strategies. Mater. Today 26, 67–86 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess P. Prediction of mechanical properties of 2D solids with related bonding configuration. RSC Adv. 7, 29786–29793 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polikov VS, Tresco PA & Reichert WM Response of brain tissue to chronically implanted neural electrodes. J. Neurosci. Methods 148, 1–18 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu S. et al. A wireless body area sensor network based on stretchable passive tags. Nat. Electron. 2, 361–368 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia H. et al. Single- and few-layer transfer-printed CVD MoS2 nanomechanical resonators with enhancement by thermal annealing. 2016 IEEE Int. Freq. Control Symp. IFCS Proc. 1–3 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X. et al. Growth of Continuous Monolayer Graphene with Millimeter-sized Domains Using Industrially Safe Conditions. Sci. Rep. 6, 2–8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao C. et al. Nonlinear fracture toughness measurement and crack propagation resistance of functionalized graphene multilayers. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao7202 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P. et al. Fracture toughness of graphene. Nat. Commun. 5, 3782 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuart SJ, Tutein AB & Harrison JA A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 6472–6486 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Duin ACT, Dasgupta S, Lorant F. & Goddard WA ReaxFF: A reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 9396–9409 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang T, Phillpot SR & Sinnott SB Parametrization of a reactive many-body potential for Mo-S systems. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 79, 245110 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun H. Compass: An ab initio force-field optimized for condensed-phase applications - Overview with details on alkane and benzene compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 7338–7364 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fonseca AF et al. Graphene-Titanium Interfaces from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 33288–33297 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong S. & Cao G. Bending response of single layer MoS2. Nanotechnology 27, 105701 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen H, Lu B-W, Lin Y. & Feng X. Interfacial Failure in Flexible Electronic Devices. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 35, 132134 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bae S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 574–578 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.