Abstract

Background: The benefits of social support are often overlooked in common management components of cardiovascular diseases. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is self-administered and scores perceived social support (PSS). We sought to identify PSS among cardiovascular patients and the effects it may have on quality of life (QoL) and treatment compliance. Methods: A total of 96 patients were evaluated using the MSPSS in 3 categories: significant other (SO), family, and friends using a 7-point Likert scale. A supplemental lifestyle survey assessed various demographics, subjective QoL, and compliance with treatment plans. Results: Patients with high QoL reported a higher PSS Likert score in the family support category. Patients who were compliant with appointments and had high substance use avoidance (tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs) had a higher PSS Likert score in the friend support and higher PSS Likert score in support from SO and family categories, respectively. No difference in PSS was found in compliance with medications, diet, and exercise. Conclusion: Various social support categories are directly associated with higher QoL, adherence to appointments, and substance abuse avoidance.

Keywords: social support, cardiovascular disease, quality of life, treatment compliance

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States, encompassing a broad range of pathologies including coronary artery disease (CAD), arrhythmias, valvular disease, congenital disease, hypertension (HTN), peripheral artery disease (PAD), dyslipidemia (DLD), and heart failure (1). Cardiovascular conditions are dynamic and often overlapping with many patients having multiple cardiac diagnoses concurrently. In the United States, the cost of medical care associated with cardiovascular disease is approximately $363.4 billion per year (1). Management can include physical therapy, medications, nursing education, nutritional management, surgical intervention, and home health care. However, the benefits of sufficient social support and consequences associated with poor social support are often overlooked. Social support can generally be classified as either emotional or instrumental. Emotional social support refers to anything that bolsters self-worth perception, while instrumental social support provides tangible items such as transportation and financial resources (2). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is used as a self-administered measurement tool scoring perceived social support (PSS) in the categories of family, friends, and significant others (3).

The aspect of social and family support remains as a pillar determining quality of life (QoL). The practical results of having support along with the feeling of being supported contribute to patient wellbeing and emotional balance. A major psychological stressor for people is their physical health. Medical diagnoses carry with them enormous management responsibilities. Patients are expected to adhere to new lifestyle routines. Daily pharmacological regimens can be complicated and extensive. Numerous doctor appointments are a financial and scheduling burden. Dietary and physical restrictions take a toll on mental and emotional wellbeing. Studies have shown that the perception of support induces patients to better adjust emotionally to their diagnoses and this therefore manifests as increased motivation and adherence to treatment plans. This has been shown not just for cardiovascular health but also in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease (4–6).

Major medical conditions can often lead to depressive symptoms. This can be especially common in diseases that can lead to profound lifestyle limitations such as many cardiovascular disorders (ie, heart failure and CAD). A study from 2003 that looked at the prevalence of depression in patients with major comorbidities found that depression in patients with decreased cardiovascular health is over 2 to 3 times more common than that of the general population (7). One cause of this depression is an absence of PSS. In fact, lack of social support is significantly correlated with depression as evidenced by a study that concluded that early detection and treatment of depressive symptoms can help improve healthcare quality (8). What is also important to emphasize is that the quality of relationships can have a larger impact on PSS than the quantity, as shown in a meta-analysis of studies examining the effects that social isolation have on cardiovascular outcome (9). Previous studies such as MOTIVATE-HF used motivational interviewing to improve self-care in patients with heart failure. In the study, patients had an increase in reported self-care scores after the use of motivational interviewing (10). Therefore, the benefits of social support are likely multifactorial involving both personal and professional guidance.

Recent literature has highlighted the finding that social support has been shown to decrease hospital readmission, improve mortality, and decrease reported levels of depression in patients with heart failure (11). One study equates the mortality risk associated with a lack of social support to that of smoking (12). An essential aspect of multidisciplinary care is close involvement of a patient's family and social network outside of the medical facility (13). Cardiovascular conditions require strict adherence to specific dietary guidelines, physical activity regimens, medications, and appointment compliance. All of these can be taxing and require adequate social support. Positive lifestyle interventions including improvement in coping mechanisms combined with family support can lead to increased compliance and healthier outcomes (14).

There are a number of scoring systems used to evaluate social support. MSPSS has been proven to be a valid and reliable metric for PSS in patients with heart failure (10). This scale measures social support by assessing the PSS from family, friends, and significant others of the patient (2, 3). Little research has been performed to investigate the impacts of the subjective perception of social support on QoL and cardiovascular treatment adherence, as these factors tend to play a central role in overall patient outcomes. We sought to evaluate patients’ PSS with the intention of better understanding direct factors that play a role in cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods

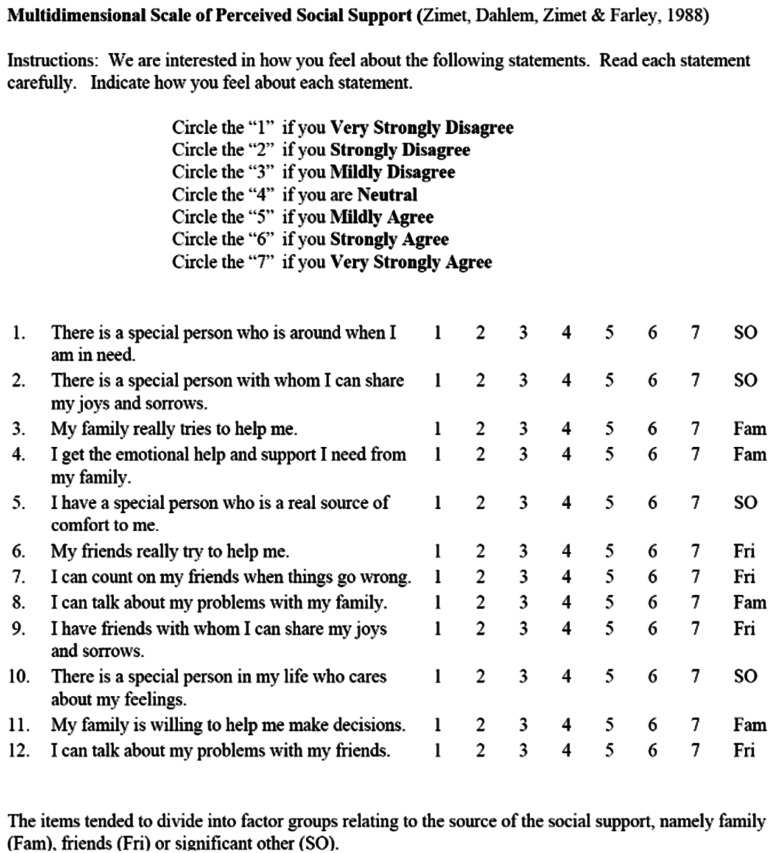

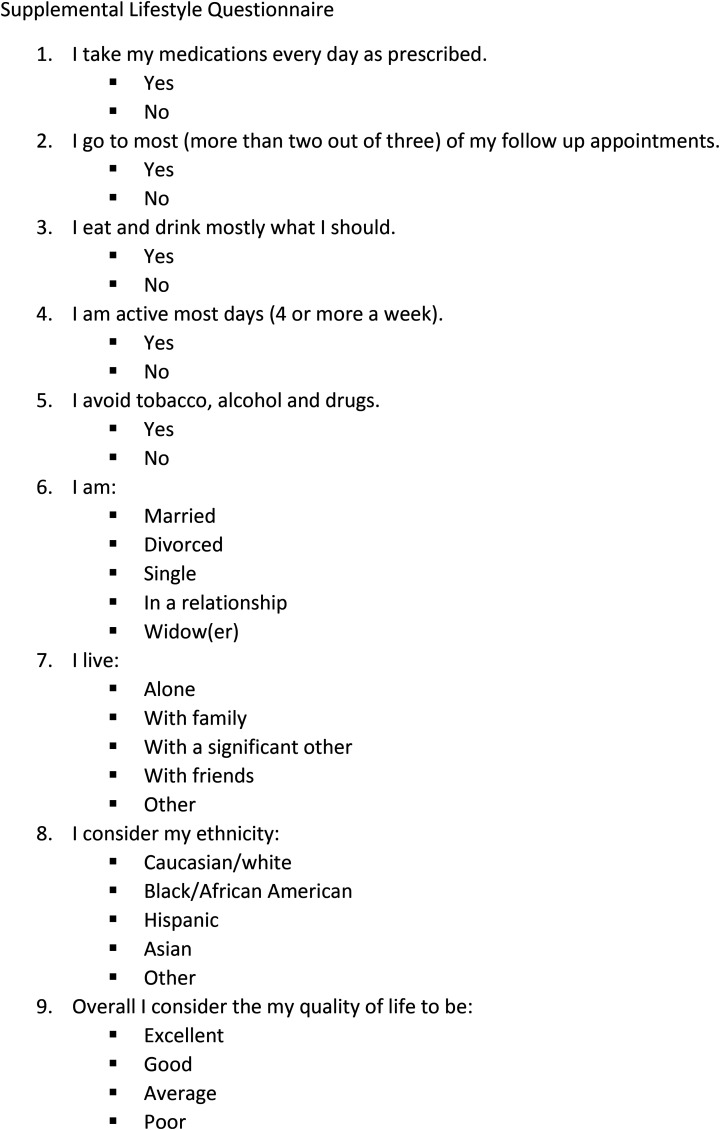

Permission was granted for utilization of the MSPSS by its creators to all researchers to utilize in their studies (3). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for our study. Ninety-six consecutive patients chosen at random for this observational study who agreed to take the MSPSS were evaluated from 1/27/2020 to 3/16/2020 either in the cardiology outpatient setting or inpatient telemetry service. These patients all carried a diagnosis of HTN, heart failure, CAD, or chronic arrhythmia. Patients who were excluded were new visits without a formal diagnosis of cardiovascular disease. The MSPSS was designed to measure PSS from 3 sources: family, friends, and a significant other, with 4 items each (Figure 1) (3). The MSPSS has demonstrated both reliability and validity in measuring PSS in patients with heart failure and has also been applied to a wide variety of other health conditions (11, 15). It has shown good to excellent internal consistency and test–retest reliability (with Cronbach's α .81 to .98 in nonclinical samples and .92 to .94 in clinical samples) (11). Our developed supplemental lifestyle questionnaire was devised to assess compliance to medications and lifestyle interventions, as well as marital status, living situation, ethnicity, and subjective QOL (Figure 2). Patients consented to participate before administration of the 2 surveys, which took place minutes before clinical outpatient visits and in the afternoon for telemetry inpatients. Participants completed the surveys by hand or by verbally responding to survey questions administered by study team members. Once collected, survey data were collated in a spreadsheet with associated patient information from the electronic medical record, including age, sex, cardiovascular diagnoses, other past medical history, number of prescribed medications, and hospitalizations within the past 5 years. For each subgroup, analysis of variance was used. The mean PSS along with standard deviation was compared between groups. Our hypothesis when this study was devised is that patients with high MSPSS will have greater QoL scores and better treatment plan compliance. We do not hypothesize that there will be a significant difference in PSS between various racial groups or specific cardiovascular diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS).

Figure 2.

Supplemental lifestyle questionnaire.

Results

The average patient age was 61.7 years old. There were 38 (40%) men and 58 (60%) women. A total of 37 patients (38.9%) were in long-term relationships and 19 (20%) lived alone. Out of the population, 87% of patients had EF (ejection fraction) <40%, 77% had HTN, 67% DLD, 28% CAD, and 16% with atrial fibrillation (afib; Table 1). QOL originally being ordinal with 4 levels (poor; average; good; excellent) was dichotomized to be low (poor or average) or high (good or excellent) to study the different mean Likert scale scores of PSS between those of low versus high QOL. The mean sub-score of PSS by family is significantly different between those of high versus low QoL (6.3 [1.5]) than those who answered their QOL as being low (5.5 [2.0]) with P = .033 (Table 2). Patient compliance with their treatment plan was stratified into medication compliance, follow-up appointments, adherence to diet and exercise regimens, and avoidance of substance abuse. Those that attend their medical appointments had significantly higher mean Likert scale PSS sub-score in the friend category than those who did not (5.3 [2.0] vs 2.3 [1.2] P = .003). Patients who were compliant with substance use recommendations (avoiding tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs) had higher mean Likert scale PSS sub-score in the significant others category (6.3 [1.4] vs 5.2 [2.3] P = .049) and in the family category (6.2 [1.4] vs 5.1 [2.3] P = .047) (Table 3). The mean PSS sub-score by the friend category is significantly different between those who have CAD and those who do not. Those who have CAD showed a higher mean sub-score of friends (6.0 [1.6] vs 4.9 [2.2] P = .007) (Table 4).

Table 1.

Total Population Demographics (n = 95).

| Age | 61.7 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 57 |

| Male | 38 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 40 |

| Hispanic | 28 |

| Asian | 3 |

| Health conditions | |

| Hypertension | 74 |

| Dyslipidemia | 64 |

| CAD | 27 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 15 |

| HFrEF | 83 |

| HFmrEF | 2 |

| HFpEF | 10 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 30 |

| Divorced | 15 |

| Single | 24 |

| In a relationship | 7 |

| Widow(er) | 19 |

| Household | |

| I live alone | 19 |

| With family | 57 |

| With a significant other | 10 |

| With friends | 2 |

| Other | 7 |

Table 2.

Mean Likert Score for PSS Categorized by Quality of Life.

| Mean Likert score for PSS categories | QoL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | P-value | |

| N | 60 | 35 | |

| Significant others (SD) | 6.1(1.7) | 6.0 (1.7) | 0.61 |

| Family (SD) | 6.3(1.5) | 5.5(2.0) | 0.033 |

| Friends (SD) | 5.4(2.0) | 4.9(2.2) | 0.25 |

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

Table 3.

Mean Likert Score for PSS Categories Categorized by Adherence to Treatment Plan.

| Mean Likert score for PSS categories | Medication | Appointment | Diet | Increased exercise | Substance use avoidance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | |

| N | 76 | 19 | 91 | 4 | 66 | 29 | 75 | 20 | 74 | 21 | |||||

| Significant others (SD) | 6.2 (1.5) | 5.4 (2.2) | 0.14 | 6.2 (1.6) | 3.8 (3.2) | 0.23 | 6.3 (1.6) | 5.6 (2.0) | 0.09 | 6.2 (1.6) | 5.5 (2.1) | 0.07 | 6.3 (1.4) | 5.2 (2.3) | 0.049 |

| Family (SD) | 6.2 (1.5) | 5.4 (2.4) | 0.19 | 6.1 (1.6) | 3.6 (3.0) | 0.19 | 6.1 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.9) | 0.37 | 6.1 (1.6) | 5.7 (1.8) | 0.37 | 6.2 (1.4) | 5.1 (2.3) | 0.047 |

| Friends (SD) | 5.4 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.3) | 0.12 | 5.3 (2.0) | 2.3 (1.2) | 0.003 | 5.2 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.1) | 0.99 | 5.4 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.3) | 0.09 | 5.4 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.3) | 0.16 |

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

Table 4.

Mean Likert Score for PSS Categories Categorized by Prevalence of Cardiovascular Health Problems.

| Mean Likert score for PSS categories | Hypertension | Dyslipidemia | CAD | Atrial fibrillation | Heart failure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | HFrEF | HFmrEF | HFpEF | |

| N | 74 | 21 | 64 | 31 | 27 | 68 | 15 | 80 | 83 | 2 | 10 | ||||

| Significant others (SD) | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.2 (1.8) | 0.61 | 6.1 (1.8) | 6.0 (1.6) | 0.90 | 6.5 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.8) | 0.08 | 5.7 (2.2) | 6.1 (1.6) | 0.34 | 6.1 (1.6) | 2.6 (2.3) | 6.2 (1.7) |

| Family (SD) | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.0 (1.6) | 0.91 | 6.1 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.7) | 0.33 | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.0 (1.8) | 0.79 | 5.4 (2.2) | 6.1 (1.6) | 0.28 | 6.1 (1.7) | 3.5 (3.5) | 5.6 (1.6) |

| Friends (SD) | 5.3 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.2) | 0.18 | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.3 (1.9) | 0.82 | 6.0 (1.6) | 4.9 (2.2) | 0.007 | 4.5 (2.5) | 5.3 (2.0) | 0.26 | 5.2 (2.0) | 4.0 (3.2) | 5.1 (2.4) |

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

Discussion

There is overwhelming literature to stress the benefit of social and family support in patients suffering from cardiovascular disease. Our aim was to determine the factors that can affect PSS and additionally investigate if correlation of PSS with patient reported QOL exists. We determined that a significant other could help to increase perceived support. Patients who identified as married or in a relationship rated higher overall PSS. Additionally, those who live in the same household as their significant other had the highest PSS scores in every category except support from friends. Similar results were found in a study which found correlation with long-term outcomes status post coronary artery bypass grafting and perceived support from spouses (16). Our data also demonstrated racial differences. The PSS by family and significant others was significantly higher for our Hispanic population.

Debilitating medical diseases require structure of support for people of all ages. We found no significant difference in the amount of support perceived based on age. However, it is worth noting that most of the population surveyed were in the 5th or 6th decades of life. We did not find a significant difference in the PSS between patients with and without diagnosis of specific cardiovascular diseases for most ailments aside from CAD (increased PSS by friends in those with CAD than those without); however, it is important to remember that all patients surveyed were from either the cardiovascular clinic or the inpatient telemetry unit. It would therefore be interesting to compare the PSS of control patients with those of our cardiovascular disease population.

Social support from all sources can help patients adhere to treatment regimens. There was a statistically significant increase in PSS by friends in those patients who regularly attend their doctor appointments. There was also a significant increase in PSS by significant others and family in those patients who avoided unhealthy substance use such as tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs. While not statistically significant, there was shown to be an increase in total PSS as well by family, significant others, and friends in patients who are compliant with medications, doctor appointments, diet, exercise, and harmful substance abstinence. A large takeaway from our research is the profound benefit that having a proper support system can be for our patients. Often, as medical professionals, the struggle to get our patients to adhere to treatment plans can be frustrating. What our research highlights is that ensuring patients have a strong foundation of support whether it be from friends, family, or significant others can tremendously aid in the motivation to stay disciplined with global treatments for cardiovascular conditions. Healthcare workers are overburdened with an excess number of patients, need for meticulous documentation of patient encounters, and increasingly complex patients with multi-organ pathologies. Unfortunately, this could potentially lead to depersonalization and inadequate patient care that can further limit patient participation and motivation to treatment (17, 18). Taking the time to inquire with patients regarding their support system outside of the medical setting will benefit both the patient and the provider. One approach is to encourage a member of a patient's support team to attend appointments and be simultaneously educated with the patient on treatment modalities, lifestyle regimens, and how to identify complications (19).

Study Limitations

Our study was limited by multiple factors. The patient population surveyed was limited to the cardiology inpatient unit and outpatient clinic and it was of relatively small size. It would be beneficial to compare the results of cardiovascular patients with the PSS of healthy control patients, or patients with disorders of other organ systems. The study was also limited by the subjectivity of patient response. Patients may differ in their perception of adjectives such as good/bad or high/low. While Likert scales may not be the most ideal way to quantify effect, they are generally an optimal way to make it easier for patients to complete the surveys we distributed to them to allow for a level quantification of the effect as opposed to a simple binary quantification. There may also be differences in the significance of these descriptors between different languages and cultural backgrounds. Several of the patients in this study did not consider English to be their first language (most of these patients spoke Spanish as their first language) and this may have subjectively affected their responses.

Conclusion

Using the self-reported MSPSS questionnaire, we found that differences in support exist between races, age, and in some cases specific cardiovascular diagnoses. What is most profound however is the correlation that PSS has with compliance with all aspects of a treatment plan including medications, appointment attendance, unhealthy substance avoidance, diet, and exercise. Follow-up investigations are necessary to look at differences in PSS between healthy patients and patients with cardiovascular disease, as well as the difference between various other organ system disease processes. We show that various social support categories are directly associated with higher QoL, adherence to appointments, and substance use avoidance. Taking the time to inquire about support systems and possible community referrals may benefit adherence and therefore overall outcomes.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: IRB approval was granted to our observational study as an expedited protocol by our Institutional Review Board (IRB# 19: 252; 1/13/2020).

ORCID iDs: Peter Wenn https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2170-945X

Daniel Meshoyrer https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0003-5425

Amgad N. Makaryus https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2104-7230

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This survey was anonymized and patient identifiers are not published relating to any patient.

Statement of Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained as the patient completed the survey.

References

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report From the American heart association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254‐743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teresa Seeman in collaboration with the Psychosocial Working Group. Support & Social Conflict: Section One - Social Support Teresa Last revised April 2008.

- 3.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton C, Effing TW, Cafarella P. Social support and social networks in COPD: a scoping review. COPD. 2015;12(6):690‐702. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1008691. Epub 2015 Aug 11. PMID: 26263036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usta YY. Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):3569‐72. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.8.3569. PMID: 23098436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamp KJ, West P, Holmstrom A, Luo Z, Wyatt G, Given B. Systematic review of social support on psychological symptoms and self-management behaviors Among adults With inflammatory bowel disease. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51(4):380‐9. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12487. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31119856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. Wang PS; national comorbidity survey replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095‐105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. PMID: 12813115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su SF, Chang MY, He CP. Social support, unstable angina, and stroke as predictors of depression in patients With coronary heart disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(2):179‐86. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000419. Erratum in: J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018 May/Jun;33(3):201. PMID: 28489724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gronewold J, Engels M, van de Velde S, Cudjoe TKM, Duman EE, Jokisch M, et al. Effects of life events and social isolation on stroke and coronary heart disease. Stroke. 2021:STROKEAHA120032070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032070. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33445957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vellone E Paturzo M Dagostino F. . et al. MOTIVATional interviewing to improve self-care in Heart Failure patients (MOTIVATE-HF): Study protocol of a three-arm multicenter randomized controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Shumaker SC, Frazier SK, Moser DK, Chung ML. Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in patient With heart failure. J Nurs Meas. 2017;25(1):90‐102. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.25.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.House J, Landis K, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540‐5. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orth-Gomér K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(1):37‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L Wang H Wang Y. . et al. Path analysis for key factors influencing long-term quality of life of patients following a percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janevic MR, Piette JD, Ratz DP, Kim HM, Rosland AM. Correlates of family involvement before and during medical visits among older adults with high-risk diabetes. Diabet Med. 2016;33(8):1140‐8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13045. Epub 2016 Jan 5. PMID: 26642179; PMCID: PMC4896854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King KB, Reis HT, Porter LA, Norsen LH. Social support and long-term recovery from coronary artery surgery: effects on patients and spouses. Health Psychol. 1993;12(1):56‐63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.1.56. PMID: 8462500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors related to physician burnout and Its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(11):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balakumar P, Maung-U K, Jagadeesh G. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113(Pt A):600‐9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.040. Epub 2016 Sep 30. PMID: 27697647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabriel AC, Bell CN, Bowie JV, LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ. Jr. The role of social support in moderating the relationship between race and hypertension in a Low-income, urban, racially integrated community. J Urban Health. 2020;97(2):250‐9. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00421-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]