Abstract

Objectives

This study evaluated a novel early childhood development (ECD) programme integrated it into the primary healthcare system.

Setting

The intervention was implemented in a rural district of Lesotho from 2017 to 2018.

Participants

It targeted primary caregivers during routine postnatal care visits and through village health worker home visits.

Intervention

The hybrid care delivery model was adapted from a successful programme in Lima, Peru and focused on parent coaching for knowledge about child development, practicing contingent interaction with the child, parent social support and encouragement.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

We compared developmental outcomes and caregiving practices in a cohort of 130 caregiver–infant (ages 7–11 months old) dyads who received the ECD intervention, to a control group that did not receive the intervention (n=125) using a case–control study design. Developmental outcomes were evaluated using the Extended Ages and Stages Questionnaire (EASQ), and caregiving practices using two measure sets (ie, UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), Parent Ladder). Group comparisons were made using multivariable regression analyses, adjusting for caregiver-level, infant-level and household-level demographic characteristics.

Results

At completion, children in the intervention group scored meaningfully higher across all EASQ domains, compared with children in the control group: communication (δ=0.21, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.26), social development (δ=0.27, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.8) and motor development (δ=0.33, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.31). Caregivers in the intervention group also reported significantly higher adjusted odds of engaging in positive caregiving practices in four of six MICS domains, compared with caregivers in the control group—including book reading (adjusted OR (AOR): 3.77, 95% CI 1.94 to 7.29) and naming/counting (AOR: 2.05; 95% CI 1.24 to 3.71).

Conclusions

These results suggest that integrating an ECD intervention into a rural primary care platform, such as in the Lesothoan context, may be an effective and efficient way to promote ECD outcomes.

Keywords: paediatrics, public health, international health services, HIV & AIDS, mental health, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Unlike early childhood development (ECD) programmes adapted for lower resources settings from wealthier settings, this intervention was created and piloted in another rural low-income and middle-income country (Peru).

The study demonstrated feasibility of integration of an ECD intervention in primary healthcare in rural and low-resource settings.

The use of an extended version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire facilitated uptake but could introduce bias as it is a parent report tool.

While translations were done by a certified translator and then reviewed by study staff, the parenting measures, in particular the Parent Ladder, were not formally adapted and validated for this context.

We were unable to include patients in dissemination activities and in the future would extend patient involvement even further.

Introduction

The period from prenatal development to 3 years of age is one of the most critical stages of brain development.1 Malnutrition and stunting2 3 threaten to deny an estimated 250 million children under 5 (43%) with the opportunity to reach their full developmental potential.4 Social forces common in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as violence, abuse and neglect trigger the body’s stress response system that can remain chronically activated into adulthood, straining the cardiovascular and central nervous systems.5 6 The impact of the culmination of these forces may be irreversible and contribute to a cycle of poverty, inequality and social exclusion.7 8 For this reason, attention has been given to finetuning strategies to reach children living in poverty in LMICs through early childhood development (ECD) programmes.9–11 Many such programmes have improved ECD, however, particularly in rural LMICs, they are primarily clinic or centre-based interventions. Clinic-based studies such as that by Chang et als’ caregiving intervention in Jamaica demonstrate that clinic-based programmes are effective in promoting cognitive development for children up to 18 months old.12 This approach has the benefit of facilitating training and delivery for practitioners, but there may be shortcomings in terms of scale up and sustainability. Clinics in rural low-resource settings are routinely overwhelmed by the volume of patients presenting with physical health conditions and ECD screening is sidelined. The salary for a mental health professional in a clinical setting can be prohibitive when hospitals manage tight budgets and urgently needed personal and supplies are likely to be prioritised.

Caregivers of physically healthy children may have little incentive to attend clinics located long distances from their home and therefore participation may be low. Caregivers in Lesotho, for instance, walk up to 10 hours each way to reach a health centre. This may be why community-based and integrated clinic-community interventions are rapidly becoming the norm. Home-based and community-based programmes benefit from the low-cost of a community workforce.13 Likewise, in home-based or community -based visitation programmes, the family can participate. The family environment is widely accepted as a central focus for intervention, including social support and/or self-esteem building of the caregivers.14 Caregivers have the unique opportunity to engage in positive interactions with their children beginning at a very young age, a practice which has been proven to nourish and even reverse early delay.15–17 Community workers are experts in local knowledge and can be allies in adaptation of curricula to local contexts, an area of ECD interventions in LMICs that is receiving increasing attention from ECD scholars.18

For this study, the team in Lesotho developed a hybrid community-based/ clinic-based ECD intervention adapted from two ECD interventions which have shown impact in other rural LMICs. Village health workers (VHWs) delivered the home-based intervention as part of their routine activities, while leveraging postnatal care (PNC) visits—during which caregivers are already attending primary care facilities with their children for immunisations—for enrolment and ECD intervention initiation.19

This pilot study evaluates the impact of this hybrid delivery model on ECD outcomes and caregiving practices by comparing a cohort of caregiver–infant (7–11 months old) dyads who received the intervention, to a comparable cohort that did not receive the intervention. We hypothesised that the delivery model would successfully engage parent–child dyads, and that the intervention would increase developmentally supportive parenting practices in turn improving developmental outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a prospective case control pilot study to test the impact of an early intervention with a hybrid delivery model on (1) improved ECD outcomes, (2) caregiver–child interaction and (3) developmentally supportive caregiving practices. The latter two were chosen as they have been shown to be mediators between ECD interventions focused on parent coaching and ECD outcomes.

Study setting

This study took place within the catchment area of Nkau Health Center in the district of Mohale’s Hoek District, Lesotho. Nkau Health Center is a rural clinic in Lesotho’s mountainous southwestern region, with an estimated catchment population of 15 000 persons as of 2016 (Lesotho Ministry of Health and ICF International, 2016). The health centre is a public government clinic supported by the medical NGO Partners In Health. Two types of VHWs are integrated into primary healthcare teams across all villages in the catchment area, with one VHW cadre focused on HIV and TB, and the other focused on maternal and child health.

Intervention

This programme was developed from an existing programme called CASITA which showed positive impact at scale in rural LMIC settings.20 A community-based ECD intervention in Carabayllo, a low-resource community outside of Lima, Peru, CASITA was developed by our sister organisation Socios En Salud (Partners In Health Succursal Peru) and is now scaling up to over 3455 children. CASITA, adapted for use from the SPARK Centre’s ECD programme for children living in poverty at Boston Medical Center, involves four featured components of ECD training sessions: (1) knowledge sharing about child development and child observation; (2) demonstration and initiation of social interaction activities tailored to the child’s development; (3) caregiver encouragement on caregiving behaviour and development interactions and (4) caregiver social support and reassurance. In the pilot study, children ages 6–24 months who screened at risk of delay received either individual home visits or group sessions with this curriculum, along with nutritional supplements. Those in the intervention group improved ECD significantly compared with the control group in all areas of delay.11 Caregivers and community health representatives widely agreed that individual home visits and group gatherings in local community centres outside of the clinic was central to its success.11 We borrowed the curricula and session structure and spacing from CASITA (table 1A, B).

Table 1.

(A) Group session activity agendas and (B) session activity agendas

| Activity | Time (minutes) | Name | Description |

| (A) | |||

| Activity 1 | 10 | Programme introductions Introductions Ice breaker |

Facilitator introduces the programme Dyad introduction In a box, collect items that symbolise ideas and activities: toys, hygiene item, object that can be used as a toy, nursing item, info on vaccines, picture of mom playing with baby, picture of baby clapping, etc. Each participant picks out an object and they describe how they think it relates to the overall topic of the project. This will allow introduction of the project content and allow caregivers to express their understanding of pertinent project items. |

| Activity 2 | 5 | Group norms | Confidentiality, importance of learning from each other, agenda for the day, etc… |

| Activity 3 | 5 | Tips | Tip related to child health and hygiene: (1) washing hands; (2) skin care for the baby (umbilical cord care); (3) perinatal care/ caring for the body after birth Provide a handout with information. |

| Activity 4 | 30 | ‘Serve and return’ concepts and practice | Play and Communication Activities: refer to activity guide Free play in small groups: Caregivers can choose the game and groups as small as two dyads practice ‘serve and return’. Facilitator and assistant give suggestions/congratulations to each group; flip charts can give ideas if needed. |

| Activity 5 | 30 | Home experience/social support and problem solving | Each mom shares experiences or ideas of stimulation and playing games in the home. If not first session, practice since the last session Open conversation: Reflect on and offer examples of barriers to stimulation in the home and/or frustrations related to their child’s development. Reach out to the group to brainstorm solutions and ideas on how to better integrate lessons learnt from the group to daily life. |

| Activity 6 | 15 | Close | Reflection on the session and suggestions and tips shared between caregivers. The facilitator and assistant will encourage caregivers’ enthusiasm. End with the same song every session to allow for another exercise to engage the caregiver and infant. |

| (B) | |||

| Activity 1 | 5 | Village Health Worker (VHW) Introduction Family Introductions |

I would like to spend some time understanding how the family is getting on with the play and communication activities recommended from the group sessions at the clinic on early childhood development. |

| Activity 2 | 30 | Home experience and problem solving | Talk to mom about experiences of stimulation and playing games in the home. Ask about progress since group session. Ask to see an example of an activity that the caregiver does with the child. Ask caregiver to reflect on and offer examples of barriers to stimulation in the home and/or frustrations related to their child’s development Remember to praise and encourage caregiver and reassure caregiver. |

| Activity 3 | 30 | ‘Serve and return’ concepts and practice | Play and Communication Activities: refer to individual session activity guide With mom and any additional family member pick one play activity and one communication activity per visit to observe with caregiver. |

| Activity 4 | 15 | Close | Ask caregiver if they have any questions and/or concerns Reiterate concepts and importance of play and communication activities Plan for next visit. |

All dyads in the intervention group were invited to participate in seven caregiver education sessions of 4–6 dyads each. Sessions at weeks 6, 10, 14 and 18 took place at Nkau Health Center and were conducted by a trained ECD nurse in a group setting. These dates corresponded to Lesotho’s national immunisation schedule, so families did not have to travel to the clinic for additional visits. Caregivers who either could not make group sessions due to scheduling or missed sessions were targeted for individual outreach by VHWs. Of the 119 participating dyads, 100% completed sessions at 6, 10 and 14 weeks, and 83 (70%) completed the final session at 18 weeks. The remaining three sessions (8, 12 and 16 weeks) were conducted by maternal health VHWs in dyads’ households. Of those, 88 (74%) completed the 8-week session, 75 (63%) completed the 12-week session and 85 (71%) completed the 16-week session. VHWs were charged with leading these sessions as they work primarily in the community, whereas ECD nurses are based in the clinic. The ECD nurse conducted unannounced spot checks of VHWs to ensure they were conducting the intervention as intended. An assessment form was completed by the ECD nurse indicating whether each activity was completed as intended. She met with the VHW after the visit and reviewed the assessment. VHWs were given an additional individual training session if one part of the session was not completed accurately. After the seven sessions were completed, VHWs continued to conduct regular home visits focused on maternal and child health.

There were two deviations from the original programme design: while the intervention was based on group sessions at health centres, flooding and scheduling challenges within villages required unanticipated one-on-one sessions by VHWs. Caregivers who missed sessions required targeted outreach, including additional VHW visitations to homes to ensure all caregivers received the complete intervention.

Training

One researcher involved in creating and piloting CASITA travelled to Lesotho and trained 80 VHWs together with the head ECD nurse, who in turn coached caregivers while modelling positive caregiving behaviours. Training took place at the Nkau Health Centre over 3 days and all VHWs travelled to the clinic to attend. Training involved lecture-style sessions in English with video examples of key concepts, translated into Sesotho, didactic small-group discussions and practice with individualised feedback. Refresher trainings for the VHWs were conducted on monthly basis (four total) during the VHWs regular meetings at the clinic. During this meeting, all 80 VHWs practised delivering home sessions for which they received feedback and the opportunity to clarify questions arising in the field. The ECD nurse reviewed the home visit agenda at each meeting and focused on problem areas observed during her unannounced fidelity visits. Refresher trainings lasted approximately 2–3 hours each.

Patient and public involvement

During adaptation, each aspect of the Lesothoan curricula was reviewed with the CASITA researcher (AKN) and the ECD nurse (RL) at the village health centre in May 2017. Draft adaptations were noted on all curricula materials and then discussed with one VHW and one local mother. Final changes were made on consensus with the on-site principal investigator (MN) and Maternal and Child Health Programme Manager (JM). Two to three patients were involved in the adaptation of the intervention. Women received the intervention in a draft phase and were asked about their reactions. Opinions were incorporated into the intervention design. Care was taken to consider local childrearing practices, of particular importance given increased concern about the cultural relevance of ECD interventions being transposed to LMICs from other contexts.18 Findings from this study will not be formally shared with study participants, however, health professionals at the clinic will be presented with the findings at a staff meeting and invited to respond to patients’ questions during clinical visits.

Study sample

Recruitment for the control and intervention groups started in May and July 2017, respectively. For the intervention group, dyads with children ages 0–6 weeks receiving PNC services at clinics in Mohale’s Hoek were recruited and offered enrolment in the intervention. Children who were born more than 2 weeks prematurely and with severe developmental delays were excluded.

As a control comparison, we identified a cohort of caregiver-infant dyads residing in the same catchment area, among whom infants were already 7–11 months old, and therefore, not eligible for the intervention. Comparison dyads were assessed with the same set of measures as the intervention group, solely during the intervention group’s baseline period. As such, the comparison of interest was between the intervention group at end line (when infants were 7–11 months old) vs the control group at baseline (when infants were 7–11 months old). The comparisons were adjusted using all demographic information and covariates.

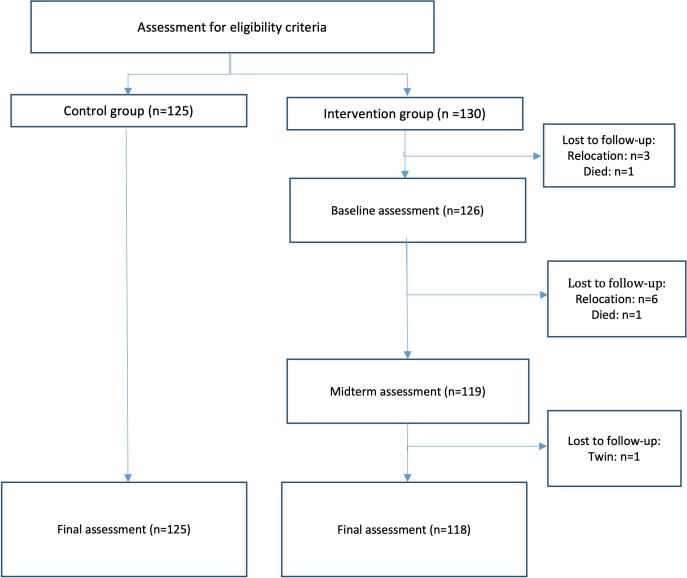

A total of 259 dyads were screened. Of these 259 dyads, 255 were enrolled: 125 dyads in the control group and 130 dyads in the intervention group. No families refused participation. Three children were born prematurely, and one child was found to have mild to severe developmental delays and thus, were excluded from the sample. At the point of analysis within the intervention group, nine dyads withdrew from the study, two were deceased, and one of a set of twins was removed from analysis to prevent bias occurring from including multiple children within a single household (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. The control group comprised caregiver–infant dyads in which infants were 7–11 months old in May–July 2017, the recruitment period. Caregiver–infant dyads in the control group were assessed immediately on study enrolment only. The intervention group comprised caregiver–infant dyads in which infants were 0–2 months in May–July 2017. Caregiver–infant dyads in the intervention group were assessed three times (baseline, midterm, final assessment), with baseline assessment conducted immediately on study enrolment and final assessment conducted an average of 8 months later, when infants were 7–11 months old.

Measures

ECD Measures. ECD was assessed using the Extended Ages and Stages Questionnaire (EASQ), an adapted version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ),21 with the same questions presented in continuous format, allowing for prescore and postscore comparison across ages.11 22 It screens for developmental risk with three domains: communication (eg, ‘If you repeat the sounds your baby makes, does s/he repeat them again after you?’), social/personal development (eg, ‘When you reach out your hand to ask for a toy, does baby hand it to you?’), and motor development (eg, ‘When your baby is lying face down, can he stretch his arms and lift his chest off the bed or floor?’). Response options are yes, sometimes, and no. A few words on the EASQ were changed for applicability in Sesotho. For instance, on the 4–6 Month item #25.7.10 which reads, ‘Does your baby make rounds like ‘ma,’ ‘da,’ “ga,’ ‘ca’ and ‘ba’?’, the team removed ‘ga’ and ‘ca’ and added ‘aaa’ and ‘na’ to mimick early sounds in Sesotho. The ASQ is widely used internationally and its psychometric properties among South African and Zambian children are consistent with other populations.23

Caregiver measures. Caregiver engagement was measured using the self-report Parent Ladder,24 an omnibus measure of caregiver engagement designed to measure knowledge, skills and behaviour. This scale contains 12 items on a seven-point ordinal scale ranging from 0 (lowest) to 6 (highest) with questions such as ‘Knowledge of how my child is growing and developing?’ and ‘Ability to identify my child’s needs?’. The global score was used to measure caregiver engagement. Second, six questions from UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey: for Children Under Five25 were selected to measure in-home caregiver-child interaction. Questions contain four multiple-response options (‘mother’, ‘father’, ‘other’, ‘no one’), and questions such as: ‘In the past 3 days, did you or any household member engage in any of the following activities with your baby: (1) Read books or looked at a picture books with baby?’ and ‘(2) …sang songs to baby, including lullabies?’.

All measures were translated into Sesotho by a certified translator and checked with the ECD nurse fluent in English, then double-checked with the site PI and MCH programme manager to ensure meaning was correct. All questions regarding meaning were discussed with a Boston-based ECD researcher.

Caregiver socioeconomic status was measured by educational attainment and household assets. Depressive symptoms were measured using the PHQ-9.26 Other covariates such as sex, age, height/length and weight, were recorded for each child at every data collection point.

Data were collected on tablets and site supervisors attended 10% of data collection events in which they completed the assessment simultaneously and discussed discrepancies with the data collector. Changes were made and the site supervisor recorded discordant questions as a percent. Follow-up training was done if 20% or more questions were discordant.

Statistical analysis

It was determined that 250 participants must be enrolled in order to detect statistical significance of alpha=0.05 with a power of 0.80 for the primary outcome variables. This study enrolled 255 participants. As a preliminary review of the data, correlations between the outcome variables and covariates were inspected using Pearson coefficients. Bivariate analyses then examined individual relationships between independent variables (see above) and outcomes of interest. Based on these preliminary analyses, we identified a consistent pattern of expected associations, indicating acceptable concurrent validity, and did not identify any correlations that were so strong (r>0.70) they may be indicative of collinearity in statistical models.

Following preliminary review, the intervention and control groups were compared using univariate and multivariable regression analysis: multivariable linear regression for continuous outcomes such as child EASQ scores, and multivariable logistic regression for binary outcomes, such as caregiving behaviours, documented in the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) survey. These comparisons examined child development outcomes and caregiving outcomes between groups, adjusting for covariates in order to safeguard against omitted variable bias. Analyses used STATA 16’s xtreg command to account for autocorrelation and clustering of multiple data points within individuals over time (StataCorp).

EASQ analysis was stratified by the test age group (7–9 months vs 10–11 months), and then merged with a dummy variable to represent test type. To ensure appropriateness of intervention and control group comparisons, dyads were compared when infants were within the same age group: namely, 7–11 months old.

Results

Of the 119 intervention dyads, 100% completed 14 weeks and 83 (70%) completed all 18 weeks. All those completing 14 sessions were included in final analysis, with the exception of one twin who was removed to prevent family bias. In the end, 243 participants had final outcome data.

Of the final sample, mean age of caregiver was 24.8 years and 64% had finished primary school. Mean parity was 2.12 and almost 10% had their last child at home. Slightly more than half (57%) of the infants. Some children showed signs of wasting (15%) and stunting (5%) at 9 months (table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of intervention and control groups

| Demographic measures: binary | Control group N (%) |

Intervention group N (%) |

| Caregiver | ||

| Female | 124 (99) | 117 (99) |

| Primary school complete | 71 (57) | 84 (71)* |

| Birth at home | 10 (8) | 13 (11) |

| Infant | ||

| Female | 73 (58) | 65 (55) |

| Evidence of wasting | 14 (11) | 22 (18)* |

| Evidence of stunting | 5 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Underweight | 7 (6) | 10 (8)* |

| Fully Immunised at 9 months | 125 (100) | 112 (95) |

| Demographic measures: continuous | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Caregiver | ||

| Age (years) | 26.01 (7.18) | 23.50 (6.32)* |

| Parity | 2.18 (1.56) | 2.06 (1.50) |

| Gravida | 2.27 (1.64) | 2.21 (1.68) |

| Pregnancy weeks at birth | 38.82 (1.72) | 38.79 (1.50) |

| ANC visits | 3.03 (1.16) | 3.35 (1.04)* |

| Household members | 5.92 (2.12) | 5.75 (2.19) |

| Depression score | 2.98 (3.08) | 5.18 (5.18)* |

| Infant | ||

| Age (months) | 9.40 (0.32) | 9.30 (0.31)* |

| Weight for height | −0.44 (1.45) | −1.03 (1.22)* |

| Length for age | 0.75 (2.08) | 0.69 (1.63)* |

| Weight for age | 0.12 (1.22) | −0.60 (1.02)* |

*Difference between control and intervention groups p<0.05.

ANC, antenatal care.

The control and intervention groups were similar across most demographic characteristics, including immunisation completion rates and percentage of clinic-based deliveries. Caregivers in the intervention were slightly more educated and younger, and scored modestly higher on the PHQ-9 depression score at endline, as well as reporting more frequent antenatal care visits. Children of caregivers in the intervention group were slightly younger and had lower anthropomorphic z-scores. Table 2 contains detailed demographic indicators. All covariates were incorporated in final multivariable regression models, regardless of statistical significance, as we determined relevance of covariates a priori based on evidence in child development literature.

Early child development outcomes

Adjusting for covariates, at endline, children in the intervention group scored higher on EASQ measures across all domains: total score, communication, social and motor development. Moreover, these results were consistent regardless of whether the age range was restricted to 7–9 months at endline, 10–11 months at endline or pooled, with the one exception being communication in the 7–9 months group, for which the intervention group observed non-significantly higher scores (p=0.08). An overview of results, measured in terms of SD improvements from baseline to endline, is presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Early child development outcomes on EASQ—difference by group

| EASQ category | Mean difference | 95% CI | Standardised coefficient |

95% CI | Adj R2 | Obs. |

| Communication | ||||||

| EASQ 7–9 months | 0.11 | 0.03 to 0.18 | 0.09 | −0.03 to 0.14 | 0.08 | 184 |

| EASQ 10–11 months | 0.50* | 0.23 to 0.76 | 0.34* | 0.14 to 0.62 | 0.41 | 59 |

| Combined | 0.27* | 0.00 to 0.18 | 0.21* | 0.07 to 0.26 | 0.22 | 243 |

| Social development | ||||||

| EASQ 7–9 months | 0.11* | 0.03 to 0.19 | 0.15* | 0.01 to 0.17 | 0.07 | 184 |

| EASQ 10–11 months | 0.49* | 0.26 to 0.73 | 0.42* | 0.20 to 0.63 | 0.42 | 59 |

| Combined | 0.27 * | 0.19 to 0.36 | 0.27* | 0.11 to 0.28 | 0.26 | 243 |

| Motor development | ||||||

| EASQ 7–9 months | 0.14* | 0.07 to 0.21 | 0.26* | 0.07 to 0.24 | 0.05 | 184 |

| EASQ 10–11 months | 0.46* | 0.20 to 0.71 | 0.46* | 0.23 to 0.75 | 0.19 | 59 |

| Combined | 0.22* | 0.16 to 0.32 | 0.33* | 0.14 to 0.31 | 0.12 | 243 |

| Total score | ||||||

| EASQ 7–9 months | 0.12* | 0.06 to 0.18 | 0.21* | 0.03 to 0.17 | 0.06 | 184 |

| EASQ 10–11 months | 0.48* | 0.30 to 0.66 | 0.51* | 0.26 to 0.60 | 0.48 | 59 |

| Combined | 0.24* | 0.20 to 0.33 | 0.32* | 0.13 to 0.27 | 0.26 | 243 |

Adjusted multivariable regression included child sex and age, as well as caregiver education, socioeconomic status and fixed effects for research staff members conducting the assessment.

*P<0.05.

EASQ, Extended Ages and Stages Questionnaire.

Caregiver outcomes

Results also indicated marked improvement on the Parent Ladder in the intervention group compared with the control group. Caregivers in the intervention group were 17 points higher at endline (44%), compared with the control group (δ=1.57, p<0.001). Differences remained significant (δ=0.56, p<0.05) after adjusting for covariates in the context of multivariate regression.

Similarly, the intervention was associated with greater odds of affirmative responses on all but one MICS items (table 4). MICS results suggested that caregivers in the intervention group were: 38 times more likely to read a book to their child in the past 3 days, 13.8 times more likely to tell stories, 2.3 times more likely to sing songs, 2.8 times more likely to engage in play, and 2.1 times more likely to name, count or draw with their child.

Table 4.

Caregiver engagement—difference by group

| MICS measure | Adj. OR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 |

| 1. Read book | 3.77* | 1.94 to 7.29 | 0.14 |

| 2. Told stories | 13.75* | 6.32 to 29.90 | 0.27 |

| 3. Sang songs | 2.29* | 1.09 to 4.83 | 0.08 |

| 4. Took outside | 1.49 | 0.76 to 2.90 | 0.05 |

| 5. Actively played | 2.83 | 0.86 to 9.21 | 0.12 |

| 6. Named/counted | 2.05* | 1.24 to 3.71 | 0.07 |

Adjusted multivariable regression included child sex and age, as well as caregiver education, socioeconomic status and fixed effects for research staff members conducting the assessment.

*P<0.05.

Adj. OR, adjusted OR; MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

Discussion

We implemented an ECD intervention in the Nkau Health Center catchment area of Mohale’s Hoek, Lesotho, one of the more rural, remote regions of the country. A total of 130 dyads were enrolled in the intervention over a 6-month period, representing the vast majority of new mothers (>90%) attending the clinic. As such, our findings suggest acceptability and feasibility for broad implementation in similar rural settings, including other districts of Lesotho. More importantly, the intervention indicated marked positive impacts on both children and caregivers enrolled.

Children whose caregivers participated in the ECD intervention observed significantly greater improvements in all developmental domains compared with a control group of the same age range. Associated effect sizes were also clinically meaningful—particularly in the older age range of 9–11 months old infants, where group standardised mean differences ranged from 0.30 to 0.50 after adjusting for covariates. We found that caregivers in the intervention group significantly improved their caregiving skills, knowledge and confidence, relative to those in the control group and were more likely engage in interactions with children following receipt of the intervention.

While several studies have shown ECD improvements through caregiver interventions,27–29 most interventions in LMICs have targeted children older than 1 year.30 One study, conducted in another rural region of Lesotho still underway, is engaging children ages 1–5 and their caregivers in eight sessions that included HIV and nutritional education and an ECD component involving book sharing to encourage caregiver-child engagement.31 Likewise, a community-based caregiver intervention by Singla et al in Uganda resulted in cognitive improvements among children aged 12–36 months.32 Evidence from high-resource settings indicates that ECD interventions targeted at this first year of child development may be particularly beneficial,17 33 as the impacts on caregiving behaviours and developmental outcomes are likely to carry forward over the course of childhood. Our study shows this may also be true in settings of poverty within LMICs.

Our study employed a strategic hybrid delivery model. As such, integrating ECD interventions into PNC services, as modelled in our study, offers a convenient way for caregivers to learn about cognitive development and child stimulation techniques while already in attendance at clinics, at a very early stage in the child’s life. Lessons provided at clinics can then be reinforced through VHWs who are operating in community-based settings, further reducing the onus that might otherwise be placed on caregivers to attend educational sessions. Several new studies are enrolling participants using a similar integrated model in other LMICs such as Bangladesh.9

Even still, ECD interventions in low-resource settings may be forgone because scarce resources limit government capacity to equip clinics and train healthcare workers.34 35 These trade-offs are inherent in many budgetary decisions, where maternal and child health are underfunded relative to other clinical care domains.36 37 Furthermore, rural communities often lack information provided through the internet and other e-learning platforms that might otherwise educate physicians, healthcare professionals and caregivers on how to encourage children’s cognitive and physical development.38 39 In such context, enhanced caregiver knowledge through ECD interventions based in the community may be introduced at low cost by building off of existing primary healthcare infrastructure. The framework outlined in this study offers a successful illustration of this.

A few study limitations should be mentioned. There is a potential for unmeasured differences between the intervention and control groups, which could account for some level of difference in ECD outcomes. We attempted to mitigate this possibility by gathering a wide range of covariates. Likewise, magnitude of the observed impact of the intervention was sizeable, making a type 1 error relatively unlikely.

A third consideration is participant response bias. Measures were dependent on self-reports of caregivers and repeated administration of tests. It is possible, for example, that those in the intervention group believed survey administrators wanted to hear that caregiving behaviour and ECD outcomes improved over time. This could overestimate the impact of the intervention on ECD. The fact that this intervention was adapted from a mixed urban and rural setting in Peru may suggest the external validity of the programme. However, its use in other African settings would depend on the similarity of the culture and setting and the careful adaptation of the content.

Further research calls on qualitative data such as focus groups to understand what aspects of the intervention were useful and how the caregivers believed their practices changed in response to the sessions.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated significant effects of an ECD intervention on ECD, as well as caregiver knowledge and skills. The intervention was implemented with few resources by leveraging existing human resources and health system infrastructure. Based on this, we are hopeful to scale the intervention more broadly in districts throughout rural Lesotho.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors reviewed manuscript drafts and consented to the final submitted version. MN is the principal investigator for this study and responsible for the work as the guarantor of the study. He is wrote the grant, securing funding, representing the study at international conferences, and interfacing with the ethics committee and US-based investigators. He oversaw on-site study activities and managed Lesotho site staff. RM is the US-based study lead who joined in the analysis phase. He was in charge of coordinating co-investigators, supervising data analysis, and cowriting the manuscript. CW conducted all data management and analysis with the help of ACM. RL, the study coordinator, reviewed translated assessment and intervention materials, translated during village health worker trainings, consulted on adaptations, conducted fidelity checks on interventions, and collected data for analysis. JMa, the then Maternal and Child Health Program Manager at Partners In Health, Lesotho managed the study coordinator and participated in adaptation of materials and training of village health workers. MC was in charge of donor compliance and study design. JC developed the study design with MC. EB developed data collection instruments, consulted on data components of the study design, analysis and review of the manuscript. SSt is a pediatrician and coinvestigator on this grant with experience working in Lesotho. She delivered expertise in the field of early child development and pediatrics. ACM is the epidemiologist responsible for data analysis for the CASITA project. She provided analytical for this study guidance to CW, specifically for the EASQ, including coding for score standardisation. SSh is the senior researcher for the CASITA project and provided high level mentorship to AKN in the adaptation of the study intervention and training of village health workers. NR is the site leader of the CASITA project and provided field-level consultation during the adaptation and training in Lesotho. JMu was the senior clinician in charge of overseeing the clinical components of the study. AKN, Principal Investigator of the pilot CASITA study, facilitated intervention and measurement tool translation and adaptation for this study. She traveled to Lesotho to train JMa, the study coordinator, and the village health workers in the intervention. She cowrote the manuscript and was in charge of submission and correspondence.

Funding: This study was funded by Grand Challenges Canada’s Saving Brains grant # SB-1707-09146.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data analysis was conducted by Collin Whelley of Parters In Health. He has all of the data which are deidentified. He is happy to share the data on request. His email is collinwhelley@gmail.com.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Lesotho National Ethics Committee, approval reference #ID51-2017. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Sea P. Brain matter matters: should we intervene well before preschool? Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev 1994;65:296–318. 10.2307/1131385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Onis M, Branca F, Onis MdaB F. Childhood stunting: a global perspective. Matern Child Nutr 2016;12 Suppl 1:12–26. 10.1111/mcn.12231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Early childhood development series Steering Committee: early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017;389:77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair C, Cybele Raver C, Granger D. Family life project key Investigators: allostasis and allostatic load in the context of poverty in early childhood. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:845–57. 10.1017/S0954579411000344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park C, Rosenblat JD, Brietzke E, et al. Stress, epigenetics and depression: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;102:139–52. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Kogali S, Krafft C. Expanding opportunities for the next generation : early childhood development in the Middle East and North Africa. The World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamadani JD, Mehrin SF, Tofail F, et al. Integrating an early childhood development programme into Bangladeshi primary health-care services: an open-label, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e366–75. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30535-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladstone M, Phuka J, Thindwa R, et al. Care for child development in rural Malawi: a model feasibility and pilot study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1419:102–19. 10.1111/nyas.13725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson AK, Miller AC, Munoz M, et al. CASITA: a controlled pilot study of community-based family coaching to stimulate early child development in Lima, Peru. BMJ Paediatr Open 2018;2:e000268. 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor SM, Powell CA, et al. Integrating a parenting intervention with routine primary health care: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015;136:272–80. 10.1542/peds.2015-0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brinkman SA, Hasan A, Jung H, et al. The impact of expanding access to early childhood education services in rural Indonesia. J Labor Econ 2017;35:S305–35. 10.1086/691278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black MM, Dewey KG. Promoting equity through integrated early child development and nutrition interventions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1308:1–10. 10.1111/nyas.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Wolff MS, van Ijzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: a meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Dev 1997;68:571–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanska G, Forman DR, Aksan N, et al. Pathways to conscience: early mother-child mutually responsive orientation and children's moral emotion, conduct, and cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005;46:19–34. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Academies of Sciences . Parenting matters: supporting parents of children ages 0-8. Washington DC, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morelli G, Bard K, Chaudhary N, et al. Bringing the real world into developmental science: a commentary on Weber, Fernald, and Diop (2017). Child Dev 2018;89:e594–603. 10.1111/cdev.13115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OaY P. Promoting care for child development in community health services. New York, NY: UNICEF, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AC, Rumaldo N, Soplapuco G, et al. Success at scale: outcomes of community-based neurodevelopment intervention (CASITA) for children ages 6-20 months with risk of delay in Lima, Peru. Child Dev 2021;92:e1275–89. 10.1111/cdev.13602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bricker DSJ. Ages and stages questionnaires: a parent completed, child monitoring system. 2nd edn. Baltimore, MD, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lia C, Fernald H, Kariger P, et al. Development gradients in low-income countries. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences. 109. National Academy of Sciences, 2012: 17273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao C, Richter L, Makusha T, et al. Use of the ages and stages questionnaire adapted for South Africa and Zambia. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:59–66. 10.1111/cch.12413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaklee HaD D. Survey of parenting practice: tool kit. Idaho Uo eds. Moscow, Idaho, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNICEF . Multiple indicator cluster survey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cates CB, Weisleder A, Mendelsohn AL. Mitigating the effects of family poverty on early child development through parenting interventions in primary care. Acad Pediatr 2016;16:S112–20. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah R, Kennedy S, Clark MD, et al. Primary care-based interventions to promote positive parenting behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137. 10.1542/peds.2015-3393. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Apr 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peacock-Chambers E, Ivy K, Bair-Merritt M. Primary care interventions for early childhood development: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20171661. 10.1542/peds.2017-1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.FEaY A, AK. Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: disease control priorities. 2. 3rd edn. Washington D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomlinson M, Skeen S, Marlow M, Cluver L, et al. Improving early childhood care and development, HIV-testing, treatment and support, and nutrition in Mokhotlong, Lesotho: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:538. 10.1186/s13063-016-1658-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singla DR, Kumbakumba E, Aboud FE. Effects of a parenting intervention to address maternal psychological wellbeing and child development and growth in rural Uganda: a community-based, cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e458–69. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00099-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rayce SB, Rasmussen IS, Klest SK, SBea: R, et al. Effects of parenting interventions for at-risk parents with infants: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015707. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schieber GJ, Gottret P, Fleisher LK, et al. Financing global health: mission unaccomplished. Health Aff 2007;26:921–34. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dieleman J, Campbell M, Chapin A, et al. Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995–2014: development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet 2017;389:1981–2004. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30874-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dua T, Tomlinson M, Tablante E, Tea: D, et al. Global research priorities to accelerate early child development in the sustainable development era. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e887–9. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30218-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hea C. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet 2020;395:605–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pea: M. Barriers and gaps affecting mHealth in low and middle-income countries: policy white paper. New York, NY: Columbia University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frehywot S, Vovides Y, Talib Z, et al. E-Learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:4. 10.1186/1478-4491-11-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data analysis was conducted by Collin Whelley of Parters In Health. He has all of the data which are deidentified. He is happy to share the data on request. His email is collinwhelley@gmail.com.