Abstract

Background and purpose

The Chiari osteotomy was a regular treatment for developmental hip dysplasia before it became mostly reserved as a salvage therapy. However, the long-term survival of the Chiari osteotomy has not been systematically investigated. We investigated the survival time of the Chiari osteotomy until conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA) in patients with primary hip dysplasia, and factors which correlated with survival, complications, and the improvement measured in radiographic parameters.

Patients and methods

Studies were included when describing patients (> 16 years) with primary hip dysplasia treated with a Chiari osteotomy procedure with 8 years’ follow-up. Data on patient characteristics, indications, complications, radiographic parameters, and survival time (endpoint: conversion to THA) were extracted.

Results

8 studies were included. The average postoperative center–edge angle, acetabular head index, and Sharp angle were generally restored within the target range. 3 studies reported Kaplan-Meier survival rates varying from 96% at 10 years to 72% at 20 years’ follow-up. Negative survival factors were high age at intervention and pre-existing advanced preoperative osteoarthritis. Moreover, reported complications ranged between 0% and 28.3 %.

Interpretation

The Chiari osteotomy has high reported survival rates and is capable of restoring radiographic hip parameters to healthy values. When carefully selected by young age, and a low osteoarthritis score, patients benefit from the Chiari osteotomy with satisfactory survival rates. The position of the Chiari osteotomy in relation to the periacetabular osteotomies should be further (re-)explored.

Patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) are prone to develop osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip at a young age (1). A variety of osteotomy procedures have been described to prevent secondary OA and to relieve pain, including the Chiari pelvic osteotomy, which distinctively augments the dysplastic acetabulum by transverse medial displacement made just proximal to the acetabular rim. The effective lateral displacement of the superior iliac fragment covers the femoral head, creating support for the capsule, increasing hip stability, enlarging the effective weightbearing surface, and increasing hip joint stability (2-4).

Chiari osteotomy historically has been considered a reasonable mainline treatment option for acetabular dysplasia (2). In recent decades, however, as powerful acetabular redirectional osteotomies and total hip replacements have proved effective, the Chiari osteotomy has become a salvage option, limited to use in very severe dysplasia or in hips with aspherical femoral heads (5). However, redirectional osteotomies can be quite invasive (6) and total hip replacements may need (multiple) revisions, especially when placed in young and active patients (7). Therefore, procedures that can postpone a total hip replacement, such as the Chiari osteotomy, should be reconsidered, though no recent joint survival analysis has been performed, as is done for other hip dysplasia treatment options, e.g., the “shelf arthroplasty” (8) and the “redirectional (peri-acetabular) osteotomy” (6), nor is there a clear consensus on indications for Chiari osteotomy (5,9).

Thus, the primary aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the long-term THA-free survival of Chiari pelvic osteotomy. The secondary aim was to evaluate reported factors that correlated with survival, the surgical indications, surgical approach, reported complications, and clinical and radiological parameters.

Patients and methods

For this systematic review, the databases Pubmed, Embase, and Cochrane were searched and queried until February 2021. The term “Chiari” was separately combined with the term “osteotomy’ including all known synonyms to minimize the chance of missing articles (see Supplementary data). Obtained articles were imported into a RefWorks database (https://refworks.proquest.com/). After removal of duplicates the abstracts were read and assessed as per MOOSE guidelines (10) for quality independently by 2 authors (MN, SS) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

From the 214 unique publications found in the systematic literature search, only 8 publications were eligible for this systematic review.

Inclusion criteria were studies in the English language, human subjects aged ≥ 16 years with primary or secondary hip dysplasia treated with Chiari procedure, and a minimum follow-up of 8 years. Studies concerning ≥ 50% patients with secondary hip dysplasia, e.g., due to Down syndrome, Trevor’s disease, Perthes disease, or cerebral palsy, were excluded. Studies in which ≥ 50% of the patients received a combined dysplasia treatment, e.g., additional osteotomies, were also excluded as we considered that in those cases the influence on the results of the Chiari osteotomy is not clear. Study inclusion was done by 3 reviewers (KW, MN, SS). Cross-references were made in the bibliographies of the included studies.

Each article was reviewed independently in full text (KW, MN, SS). Items reviewed included age, sex, number of patients and hips, study type, level of evidence, number of patients who were lost to follow-up, combination with other treatments, previous operations, preoperative OA (with scale), failure as defined by the authors (see below), survival rates (conversion to THA), complications, surgical indication, and the change in hip score (with scale). The preoperative and postoperative hip parameters (center–edge angle = CEA, Sharp angle = SA, and acetabular head index = AHI) were reviewed and visualized. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of each study and the average between the 2 scores of the independent observers (MN and NIH) was documented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Included studies, all retrospective

| Reference (ref. #) (year) | Type of procedure | Stratified for a | Analyzed hips/patients | Male/female | Mean age (range)/(SD) | Combination with other treatment n (%) | Previous hip operation n (%) | OA scale b | Preop. Advanced OA, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calvert et al. (15) (1987) | Chiari (30) | 49/45 | 7/38 | 20 (3-41) | NA | 28 (57) | Own | NA | |

| Kotz et al. (22) (2009) | Chiari (4) | 80/66 | 9/57 | 23 (2-50) | NA | NA | Tönnis | NA | |

| Migaud et al. (17) 2004 | Chiari (31) | 89/82 | NA | 34 (17-56) | NA | 9 (10) | MP | 67 (75) | |

| Nakano et al. (18) (2007) | Modified | Labrectomy (+) | 20/20 | 3/17 | 35 (16-54) | 5 (16) | 1 (3) | JOA | 4 (20) |

| Chiari (21) | Labrectomy (−) | 11/11 | 3/8 | 37 (21-52) | 6 (55) | ||||

| Nakata et al. (16) (2001) | Dome modified | 96/87 | 8/79 | 29 (16-55) | 48 (50) | 8 (8) | JOA | 23 (24) | |

| Chiari (32) | |||||||||

| Ohashi et al. (20) (2000) | Chiari (4) | POA | 86/78 | 12/66 | 18 (6-48) | 41(40) | 3 (3) | JOA | 0 (0) |

| AOA | 17/15 | 1/14 | 37 (11-54) | 17 (100) | |||||

| Rozkydal et al. (21) (2003) | Chiari (4) | 130/130 | 5/125 | 29 (15-52) | 10 (8) | NA | K-L | 10 (8) | |

| Yanagimoto et al. (19) (2005) | Chiari (4) | Total | 74/69 | 6/63 | 31 (6-64) | 12 (16) | NA | JOA | 38 (51) |

| Early, spherical | 16/NA | NA | 23 (14) | NA | NA | 0 | |||

| Early, flat | 20/NA | NA | 18 (6.7) | NA | NA | 0 | |||

| Advanced, spherical | 17/NA | NA | 43 (8.8) | NA | NA | 17 (100) | |||

| Advanced, flat | 21/NA | NA | 39 (7.5) | NA | NA | 21 (100) |

Table 1.

continued.

| Reference | NOS score c | Stratified for | Analyzed hips/patients | Follow-up years, mean (range) | Conversions to THA n (%) | Clinical outcome scale d | Pre. | Hip score mean (range)/(SD) Post. | At follow-up | Patients lost to follow-up, ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calvert et al. (15) | 7 | 49/45 | 14 (10–19) | 3 (6) | HHS | NA | NA | 76 (33–76) | 27/72 (38) | |

| Kotz et al. (22) | 6.5 | 80/66 | 32 (27-48) | 32 (40) | HHS | NA | NA | 79 (37-100) | 384/450 (8) | |

| Migaud et al. (17) | 8 | 89/82 | 14 (6-25) | 23 (26) | PMA | NA | NA | NA | 10/99 (10) | |

| Nakano et al. (18) | 5 | Labrectomy (+) | 20/20 | 16 (10-23) | 1 (5) | JOA | 72 | NA | 83 | 3/34 (9) |

| Labrectomy (−) | 11/11 | 15 (10- 21) | 0 | |||||||

| Nakata et al. (16) | 96/87 | 13 (10-18) | 4 (4) | PMA | 14 | NA | 17 | 35/122 (29) | ||

| Ohashi et al. (20) | 7 | POA | 86/78 | 17 (4-37) | 1 (1) | JOA | 79 (8) | NA | 89 (13) | 20/113 (18) |

| AOA | 17/15 | 16 (1-27) | 4 (24) | 63 (8) | NA | 84 (12) | ||||

| Rozkydal et al. (21) | 7 | 130/130 | 22 (15-30) | 50 (38) | HHS | 42 (36-55) | NA | 68 | 100/230 (43) | |

| Yanagimoto et al. (19) | 5.5 | Total | 74/69 | 13 (10-20) | 2 (3) | JOA | 72 | NA | 87 | 33/102 (32) |

| Early, spherical | 16/NA | NA | NA | JOA | 79 | NA | 95 | NA | ||

| Early, flat | 20/NA | NA | NA | JOA | 81 | NA | 96 | NA | ||

| Advanced, spherical | 17/NA | NA | NA | JOA | 66 | NA | 71 | NA | ||

| Advanced, flat | 21/NA | NA | NA | JOA | 61 | NA | 84 | NA |

Preoperative OA was recorded and dichotomized between mild and advanced OA because different scales were used: the Tönnis (11), De Mourges and Patte (DMP) (12), Japanese Orthopedic Association (13), and Kellgren–Lawrence (K–L) (14). Therefore, in every scale the level that corresponds to advanced OA was identified, after which the number of patients who were in an advanced state of OA were identified (Table 1). Differences in extracted information were discussed between the reviewers and consensus was reached at all times regarding the aspect in question. Authors of included studies were not contacted in the event of missing data.

No statistics were used due to the heterogenous data available.

Funding and potential conflicts of interest

KW and HW have received research grants from the European Government through the Prosperos project by Interreg VA Flanders—The Netherlands program, CCI grant no. 2014TC16RFCB046; and KW, HW, PS from the Dutch government through the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO; Applied and Engineering Sciences research programme, project number 15479) in relation to the submitted work. HW has also received a research grant from the Dutch Arthritis Foundation outside the submitted work. PS has owner shares in MRIguidance B.V. not related to the submitted work. MN, SS, NIH, BW, and RS declare no competing interests.

The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

180 studies were identified, of which 8 remained after inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Results are summarized in Table 1. All included studies were of observational retrospective cohort design (level IV evidence), without the use of a control group.

In all cases, the osteotomy was extracapsular, located just superior to the hip joint. The osteotomy was specified as straight in 1 study (15), while in 3 other studies it was specified as curved (16-18), and in 4 studies the shape of the osteotomy was not stated (19-22). The osteotomy height was performed at 5.5–9.0 mm height from the articular surface (15,16,18,19). Furthermore, the osteosynthesis was fixated by a plate in 1 study (17), and with Steinman pins in a second study (15). 2 studies specified the usage of graft material (17,19), while 1 other study only used graft material following complications of non-union (20). 5 studies combined the Chiari procedure with a varus or valgus osteotomy of the proximal femur (3.1–25%) (16,18-21), and 2 studies combined the Chiari procedure with a trochanter osteotomy (1.3–1.9%) (19,20).

Preoperative indications and negative survival factors varied widely among all 8 studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for the Chiari procedure and negative survival predictors as suggested by the authors

| Reference Inclusion criteria | Significant negative survival factors |

|---|---|

| Calvert et al. (15) Congenital hip dislocation Acetabular dysplasia |

None reported |

| Kotz et al. (22) High-grade dysplasia without signs of OA |

Age at the time of operation |

| Migaud et al. (17) Acetabular dysplasia Preoperative stage of OA and CEA > 0° |

Age before operation |

| Nakano et al. (18) OA secondary to congenital subluxation or acetabular dysplasia |

Reduced volume of the interposed soft tissues: capsule and the remaining labrum. Presence of labrum interposed between the new acetabular roof and the femoral head |

| Nakata et al. (16) Pain and disability attributable to OA |

Preoperative stage of OA |

| Ohashi et al. (20) Subluxation of the hip and OA |

None reported |

| Rozkydal et al. (21) DDH |

Level of osteotomy (high or low). Severe deformity of femoral head |

| Yanagimoto et al. (19) DDH |

Advanced DDH. Spherical femoral head |

CEA = center–edge angle, DDH = developmental dysplasia of the hip, OA = osteoarthritis.

All studies documented radiological angles and all studies that documented both preoperative and postoperative values found a postoperative increase in average CEA and AHI, while the SA decreased postoperatively (Figure 2). Migaud et al. (17) reported a positive relation between improved radiographic scores and postoperative function and Nakata et al. (16) reported that hips with lower angles subsequently correlated with progression to terminal OA, whereas Calvert et al. (15) reported no correlation between achieved postoperative CEA and hip score.

Figure 2.

Displays the average preoperative and postoperative radiological values. (A) Center–edge (CE) angle: (B) Acetabular head index (AHI), and (C) Sharp angle. Green areas display the operative target values.

All articles reported the number of conversions to THA in regard to average follow-up, ranging from 1% conversions in 17 years to 40% conversions in 32 years (Table 1).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with radiological progression of OA as endpoint was documented in 3 studies using the Japanese Orthopedic Association scale (16,18,20). Ohashi et al. (20) analyzed 62 hips with Chiari osteotomy alone, and recorded a 84% survival rate at 10 years and 69% at 20 years. The survival rate for 24 hips using a combined Chiari procedure with a varus or valgus osteotomy was 82% and 44% at 10 and 20 years, respectively.

Nakata et al. (16) reported survival rates in 56 patients (63 hips) at 10 and 15 years follow-up of 92% and 78%. Respectively, Nakano et al. (18) analyzed 20 patients (20 hips) with labrectomy, and 11 patients (11 hips) without labrectomy at a mean age of 35 years. Survival rates for the labrectomy group were 80% at 10 years’ and 67% at 15 years’ follow-up. For the group without labrectomy this was 100% and 83%, respectively.

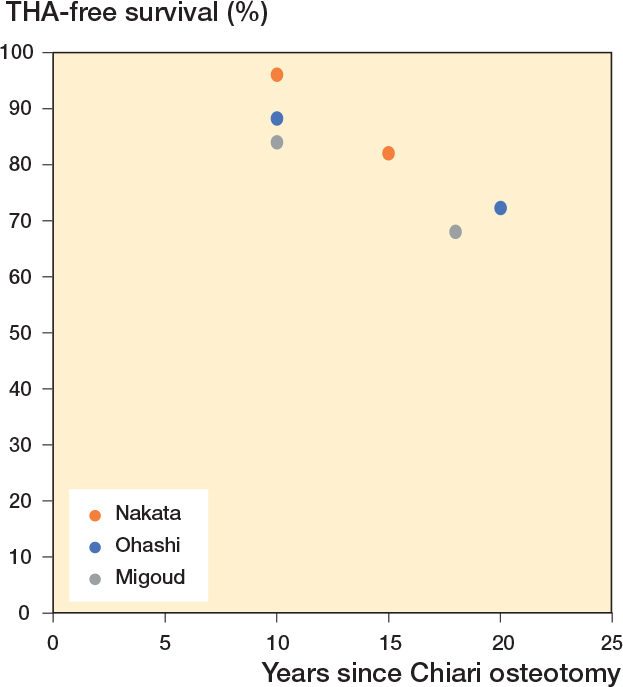

Kaplan Meier survival analysis with conversion to THA as endpoint (Figure 3) were documented by 3 studies (16,17,20). First, Ohashi et al. (20) reported THA as endpoint in the advanced OA group, which consisted of 17 hips in 15 patients with a mean age of 39 (range 11–54). The survival rate after 10 years was 88%, and 72% at 20 years. Second, Nakata et al. (16) analyzed 96 hips from 87 patients with an average age of 29 (range 16–55). Of these, 96% lasted 10 years, and 82% survived 15 years until conversion to THA. Third, Migaud et al. (17) analyzed 99 hips in 92 patients with an average age of 34 (SD 11) and found a survival rate of 84% at 10 years’ and 68% at 18 years’ follow-up. The survival rates for DMP grade 2, 3, and 4 OA were documented as 94%, 74%, and 54% at 18 years. Additionally, severe arthrosis (DMP grade 3 and 4) in combination with a positive preoperative CEA (> 0°) was significantly (p < 0.05) associated with a higher conversion to THA. 2 other studies reported non-Kaplan–Meier survival percentages with THA as failure definition. Survival ranged from 55% to 60% with a mean time interval between 17.6 and 26.0 years (21,22).

Figure 3.

Survival of Chiari osteotomy with years to THA as endpoint. The data for these Kaplan–Meier survival analysis results was extracted from the articles.

Rehabilitation outcomes and postoperative weightbearing were documented in 4 studies Postoperatively, non-weightbearing was done with a hip spica cast (16,18,21) or with crutches (21,22). Partial weightbearing started at 6 weeks (16,18,22), and full weightbearing after 12 weeks postoperatively (16,18,21).

The complication rate and the background information on the complications were reported by all articles, except for Nakano et al. (18) and Kotz et al. (22) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications for the Chiari procedure

| Reference | Hips/patients | No of complications | Complications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| major | minor | n | |||

| Calvert et al. (15) | 49/45 | 3 | 31 | 25 | Thigh numbness * |

| 3 | Superficial infection | ||||

| 2 | Plaster sores | ||||

| 1 | Dislocation of hip | ||||

| 1 | Stiffness (needing manipulation under anesthesia) | ||||

| 1 | Screw protruding into pelvis | ||||

| 1 | Chronic infection | ||||

| Kotz et al. (22) | 80/66 | Not specified | |||

| Migaud et al. (17) | 89/82 | Not specified | |||

| Nakata et al. (16) | 96/87 | 3 | 0 | 2 | Perforation of an oscillating saw into the joint space |

| 1 | Trochanteric bursitis | ||||

| Nakano et al. (18) | 31/31 | 0 | 0 | − | No complications reported |

| Ohashi et al. (20) | 103/93 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Injury to the external iliac artery during surgery + nonunion |

| 1 | Superficial wound infection | ||||

| Rozkydal et al. (21) | 130/130 | 5 | 0 | 3 | Extreme medialization with no contact between the fragments (overlapping) requiring a revision |

| 2 | Nonunion | ||||

| Yanagimoto et al. (19) | 74/69 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Rapid progression of osteoarthritis and femoral head migration |

Discussion

This study reviews survival rates after the Chiari procedure and aimed to evaluate factors that influence survival, and reported indications, complications, and functional and radiological parameters. The included studies with a minimal follow-up of at least 8 years showed good survival outcomes after surgery varying between 68% at 18 years’ and 86% at 30 years’ follow-up. Furthermore, the Chiari procedure may also be able to increase hip scores and restore radiological angles within normal ranges, with minimal occurrences of major complications.

Careful selection of patients is important for the success of any surgery. However, the outcomes between the included studies were difficult to compare, because of heterogeneous patient characteristics due to differences in inclusion (Tables 1 and 2), ranging from pain, and/or dysplasia with and without concurrent OA, to avascular necrosis of the femoral head and with a negative or positive preoperative CEA. Migaud et al. (17) recommend that the Chiari osteotomy should be done in patients with severe arthrosis and low CEA regardless of present subluxation or the loss of congruency. However, higher levels of arthrosis by itself are again a negative survival factor (Table 2) (16,19). Moreover, patients with deformities of the femoral head were reported to be more vulnerable to the progression of OA (19,21), as it can be associated with bone atrophy, poor repair, or the presence of acetabular labral tears (19). Yet again, the Chiari osteotomy is preferred over the peri-acetabular osteotomy (PAO) in hips with dysplasia where pelvic remodeling is restricted due to extreme dysplasia or aspheric femoral heads (5,9,23). This lack of consensus makes it difficult to appraise the Chiari osteotomy in relation to other procedures.

In the included studies, often a combination was made between the Chiari osteotomy and, e.g., a femoral osteotomy, making it difficult to ascribe the success of the survival time solely to the value of the Chiari osteotomy, and differences in the THA conversion endpoints amplify this effect. However, in 1 study by Ito et al. (24), 87% of all Chiari procedures were combined with a varus osteotomy, they did not find a significant difference between the group with or without femur osteotomy, and survival was also negatively affected by high age and the stage of OA (16,24).

Nonetheless, the Chiari procedure shows surprisingly high survival rates, in the four studies that reported Kaplan–Meier analysis with THA conversion as endpoint (Figure 2). Taking into account the high survival rates, complication rates, and radiological and functional improvements, this raises the question as to whether the Chiari osteotomy should be reconsidered in the palette of treatment options for developmental hip dysplasia.

The number of reported complications ranged from 0% to 28%, when excluding the number of patients with “thigh numbness” reported by Calvert et al. (15), which may be regarded as a direct and inevitable result of iatrogenic injury to the cutaneous nerves. It should be noted that after the Chiari osteotomy there is a potential decrease in pelvis diameter and if this (transverse mid-pelvic) diameter is < 9.5 cm the likelihood of a Caesarean section is increased (25). Moreover, despite it not being scored as a complication, some patients keep a persisting limp after the Chiari osteotomy. These factors should be explained to the patient when the Chiari procedure is considered as a treatment method. When the Chiari osteotomy is performed but needs to be converted to a THA it is good to mention that the salvage THA has comparable results to a primary THA (26).

The reviewed literature showed considerable limitations. First, all included articles were of level IV evidence with retrospective design and relatively small numbers, no control groups were present, and therefore it was difficult to make a comparison with a nonoperative, PAO, or shelf treatment. Moreover, evaluation time points in relation to the surgery or the number of patients per evaluation were often not reported. Second, the research population largely included females, but none of the included studies stratified for sex, which could have influenced results, and this could limit generalization to a male population, although the incidence of hip dysplasia is higher in women.

Nevertheless, in this era of advanced technology (27) and complex acetabular osteotomies (28,29), it may be useful to reassess the role of historical procedures such as the Chiari osteotomy, which may still have a role in selected clinical situations. Moreover, due to technological progression, additive manufacturing techniques are also being considered to treat hip dysplasia (28,30,31) and might help in planning and evaluating to increase the success of the Chiari osteotomy (29).

Conclusion

Chiari osteotomy has often yielded long-term hip preservation rates, can improve hip coverage, and hip functional parameters to near-normal values, and has a relatively low reported major complication rate. Moreover, when carefully selected for patients of young age, or minimal preoperative OA, patients may benefit from the Chiari osteotomy with satisfactory survival rates.

Acknowledgments

Conceptualization: KW, BW; methodology: KW, MN, SS, NH; data curation: KW, MN, SS, NH; validation: KW, RS, BW, HW; supervision: KW, RS, HW, BW; writing, review, and editing: all authors.

Acta thanks Jan Erik Madsen and Michael Brian Millis for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary data

PUBMED Search Search terms

# 1 = Chiari*[Title/Abstract] OR Dome (Title/Abstract)

# 2 = (((((((((arthroplast*[Title/Abstract]) OR procedure[Title/Abstract]) OR surgery[Title/Abstract]) OR operation[Title/Abstract]) OR acetabuloplast*[Title/Abstract]) OR hip[Title/Abstract]) OR osteotom*[Title/Abstract]))

# 3 = #1 AND #2

# 4 = ((((Hip[Title/Abstract]) OR Coxa[Title/Abstract]) OR Hips[Title/Abstract]))

# 5 = (dysplas*[Title/Abstract])

# 6 = # 3 AND # 4 AND # 5

EMBASE Search Search terms

# 1 = Chiari*:ab,ti OR Dome:ab,ti

# 2 = (arthroplast*:ab,ti OR procedure:ab,ti OR surgery:ab,ti OR operation:ab,ti OR acetabuloplast*:ab,ti OR hip:ab,ti OR osteotom*:ab,ti)

# 3 = #1 AND #2

# 4 = (hip:ab,ti OR coxa:ab,ti OR hips:ab,ti)

# 5 = dysplas*:ab,ti

# 6 = # 3 AND # 4 AND # 5

COCHRANE Search Search terms

# 1 = ‘’Chiari*’’:ti,ab,kw or ‘’Dome’’:ti,ab,kw

# 2 = (‘’arthroplast*’’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘’procedure’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’surgery’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’operation’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’acetabuloplast*’’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘’hip’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’osteotom*’’:ti,ab,kw)

# 3 = #1 AND #2

# 4 = (‘’hip’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’coxa’’: ti,ab,kw OR ‘’hips’’: ti,ab,kw)

# 5 = ‘’dysplas*’’:ti,ab,kw

# 6 = # 3 AND # 4 AND # 5

References

- 1.Weinstein S L. Natural history and treatment outcomes of childhood hip disorders. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; (344): 227-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds D A. Chiari innominate osteotomy in adults: technique, indications and contra-indications. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1986; 68(1): 45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiari K. Results of pelvic osteotomy as of the shelf method acetabular roof plastic. Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und ihre Grenzgebiete 1955; 87(1): 14-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiari K. Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1974; (98): 55-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otani T, Kawaguchi Y, Fujii H, Hayama T, Marumo K. Indications for shelf acetabuloplasty and rotational acetabular osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of the hip. In: Revival of shelf acetabuloplasty. Dordrecht: Springer; 2018. p. 83-96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clohisy J C, Schutz A L, John L S, Schoenecker P L, Wright R W. Periacetabular osteotomy: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(8): 2041-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papachristou G, Hatzigrigoris P, Panousis K, Plessas S, Sourlas J, Levidiotis C, et al. Total hip arthroplasty for developmental hip dysplasia. Int Orthop 2006; 30(1): 21-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willemsen K, Doelman C J, Sam A S Y, Seevinck P R, Sakkers R J B, Weinans H, et al. Long-term outcomes of the hip shelf arthroplasty in adolescents and adults with residual hip dysplasia: a systematic review. Acta Orthop 2020; 91(4): 383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turgeon T R, Phillips W, Kantor S R, Santore R F. The role of acetabular and femoral osteotomies in reconstructive surgery of the hip: 2005 and beyond. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; 441: 188-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C, Olkin I, Williamson G D, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 2000; 283(15): 2008-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tönnis D, Heinecke A. Current concepts review: Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81(12): 1747-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Mourgues G, Patte D. Résultats, après au moins 10 ans, des ostéotomies d’orientation du col du fémur dans les coxarthroses secondaires peu évoluées chez l’adulte: symposium. Rev Chir Orthop 1978; 64(7): 525-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takatori Y, Ito K, Sofue M, Hirota Y, Itoman M, Matsumoto T, et al. Analysis of interobserver reliability for radiographic staging of coxar-throsis and indexes of acetabular dysplasia: a preliminary study. J Orthop Sci 2010; 15(1): 14-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellgren J H, Lawrence J. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Theum Dis 1957; 16(4): 494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert P T, August A C, Albert J S, Kemp H B, Catterall A. The Chiari pelvic osteotomy: a review of the long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987; 69(4): 551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakata K, Masuhara K, Sugano N, Sakai T, Haraguchi K, Ohzono K. Dome (modified Chiari) pelvic osteotomy: 10- to 18-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (389): 102-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (418): 81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano S, Nishisyo T, Hamada D, Kosaka H, Yukata K, Oba K, et al. Treatment of dysplastic osteoarthritis with labral tear by Chiari pelvic osteotomy: outcomes after more than 10 years follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008; 128(1): 103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagimoto S, Hotta H, Izumida R, Sakamaki T. Long-term results of Chiari pelvic osteotomy in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: indications for Chiari pelvic osteotomy according to disease stage and femoral head shape. J Orthop Sci 2005; 10(6): 557-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi H, Hirohashi K, Yamano Y. Factors influencing the outcome of Chiari pelvic osteotomy: a long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82(4): 517-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozkydal Z, Kovanda M. Chiari pelvic osteotomy in the management of developmental hip dysplasia: a long term follow-up. Bratislavske lekarske listy 2003; 104(1): 7-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotz R, Chiari C, Hofstaetter J G, Lunzer A, Peloschek P. Long-term experience with Chiari’s osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(9): 2215-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lack W, Windhager R, Kutschera H P, Engel A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy for osteoarthritis secondary to hip dysplasia. Indications and longterm results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73(2): 229-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, Nakamura T, Minami A, Matsuno T. The Chiari pelvic osteotomy for patients with dysplastic hips and poor joint congruency: long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(6): 726-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loder R T. The long-term effect of pelvic osteotomy on birth canal size. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122(1): 29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider E, Stamm T, Schinhan M, Peloschek P, Windhager R, Chiari C. Total hip arthroplasty after previous Chiari pelvic osteotomy: a retrospective study of 301 dysplastic hips. J Arthroplasty 2020; 35(12): 3638-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willemsen K, Nizak R, Noordmans H J, Castelein R M, Weinans H, Kruyt M C. Challenges in the design and regulatory approval of 3D-printed surgical implants: a two-case series. Lancet Digit Health 2019; 1(4): e163-e171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Liu S, Peng J, Zhu Z, Zhang L, Guan J, et al. Development of a novel customized cutting and rotating template for Bernese periace-tabular osteotomy. J Orthop Surg Res 2019; 14(1): 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otsuki B, Takemoto M, Kawanabe K, Awa Y, Akiyama H, Fujibayashi S, et al. Developing a novel custom cutting guide for curved peri-acetabular osteotomy. Int Orthop 2013; 37(6): doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1873-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willemsen K, Tryfonidou M, Sakkers R, Castelein R M, Zadpoor A A, Seevinck P, et al. Patient–specific 3D–printed shelf implant for the treatment of hip dysplasia: snatomical and biomechanical outcomes in a canine model. J Orthop Res 2021. Jun 30. doi: 10.1002/jor.25133. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golafshan N, Willemsen K, Kadumudi F B, Vorndran E, Dolatshahi–Pirouz A, Weinans H, et al. 3D–printed regenerative magnesium phosphate implant ensures stability and restoration of hip dysplasia. Adv Healthc Mater 2021; 10(21): e2101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda H, Kamogawa J, Sakayama K, Kamada K, Tanaka S, Yamamoto H. Evaluation of clinical prognosis and activities of daily living using functional independence measure in patients with hip fractures. J Orthop Sci 2006; 11(6): 584-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka S. Surface replacement of the hip joint. Clin Ortho Relat Res 1978; (134): 75-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]