Abstract

Introduction

Prospective evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of carbon-ion radiotherapy (C-ion RT) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains lacking. This prospective study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of hypofractionated C-ion RT in patients with HCC.

Methods

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathologically or clinically diagnosed HCC; (2) measurable tumor and tumor size ≤10 cm; (3) absence of major vascular invasion; (4) no extrahepatic metastasis; (5) the alimentary tract was not adjacent to the target lesion (>1 cm); (6) not suitable for or refusal to undergo surgery or local ablative therapies; (7) an interval ≥4 weeks from previous therapy; (8) no other intrahepatic lesion or at least 2 years after the previous curative therapy; (9) performance status score, 0–2; and (10) Child-Pugh score, 5–9. The prescribed C-ion RT dose was 52.8 Gy (relative biological effectiveness [RBE]) or 60.0 Gy (RBE) in 4 fractions.

Results

In total, 35 patients with HCC were enrolled between October 2010 and May 2016. The median follow-up durations in the survivor group (n = 23) and in the whole cohort were 55.1 and 49.0 months, respectively. The 2-, 3-, and 4-year overall survival rates were 82.8%, 76.7%, and 69.4%, respectively. The 2-, 3-, and 4-year local control (LC) rates were 92.6%, 76.5%, and 76.5%, respectively. The median time-to-progression was 25.6 months (95% confidence interval, 13.7–37.5 months). Grade 4 or 5 toxicities were not observed. Grade 3 acute and late toxicities were observed in 2 patients. There was no significant deterioration in serum albumin, bilirubin, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio, platelet count, or Child-Pugh score after C-ion RT.

Conclusion

Four fractions of C-ion RT for HCC did not yield serious adverse events and showed promising LC, thus making it a safe and effective modality for this type of malignancy.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Heavy ion radiotherapy, Carbon-ion radiotherapy, Prospective

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1, 2]. Although surgery and percutaneous ablation therapy are curative treatments, only limited patients are eligible for these treatments because most have a high tumor burden, poor hepatic function, comorbidities, and poor performance status (PS) and because of graft donor shortage [3, 4, 5]. Radiation therapy has been increasingly used in HCC treatment [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with X-rays shows excellent local control (LC) for small HCCs [11, 12, 13]. However, large tumors are challenging to treat because of dose limitations to the surrounding normal liver tissues [14]. Proton beam therapy (PBT), which has better dose distribution characteristics but has almost the same biological effects compared to X-rays, is the most widely used charged particle therapy. The number of institutions using PBT is rapidly increasing [7, 15]. Carbon-ion radiotherapy (C-ion RT) has an excellent dose distribution and higher biological effectiveness than X-rays due to its high linear energy transfer. Although it requires acceleration with a large cyclotron, C-ion RT is theoretically an ideal radiotherapy technique [16, 17, 18]. Furthermore, some previous studies have shown that C-ion RT could be performed with fewer fractions than proton beams [19, 20]. A short treatment duration also has the advantage of maintaining the patient's quality of life.

HCC not adjacent to organs at risk, such as the alimentary tract or porta hepatis, can be treated with a fractionation of 4 or less [9, 21, 22, 23]. Studies on the usefulness of C-ion RT for HCC have also reported promising results [9, 23, 24, 25]. However, most of these studies are retrospective, and robust evidence supporting the safety and efficacy in a prospective setting is still lacking. Only 2 prospective studies including the dose-fractionation investigation phase have been conducted to date, and these were conducted before February 2003 in the same institution specializing in radiation therapy [25, 26].

Gunma University Heavy-ion Medical Center (GHMC) is the first facility affiliated to a general hospital to offer C-ion RT since 2009 [27]. At GHMC, patients with HCC receive multimodal treatment involving hepatobiliary surgery, hepatology, interventional radiology, and radiation oncology. Here, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of hypofractionated C-ion RT in patients with HCC.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a single-arm, single-center prospective study registered in the clinical trial database; the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR, trial number: 000020571, http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm). This study was approved by the local institutional review board (approval No. 722) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all its amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the initiation of any protocol examination and procedures.

The participants were patients with HCC who met all of the following criteria: (1) pathologically proven or clinically diagnosed HCC based on the Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines [28]; (2) ability to be treated by single irradiated field including satellite nodules (daughter nodules); (3) measurable tumor and tumor size ≤10 cm; (4) no tumor invasion to the main branch of the portal vein, common hepatic duct, or inferior vena cava; (5) cN0M0 (according to the International Union Against Cancer TNM classification of malignant tumors seventh edition); (6) not suitable for or refusal to undergo surgery or local ablative therapies (the indication was decided by a multidisciplinary board of hepatobiliary surgeons, hepatologists, and interventional radiologists); (7) at least 4 weeks duration from the previous therapy (hepatectomy, local ablation therapy, or trans-arterial therapies); (8) no other intrahepatic lesion or an interval of at least 2 years between the previous curative therapy and the development of other intrahepatic lesions; (9) PS, 0–2; and (10) Child-Pugh score, 5–9 points. Patients were excluded if (1) they had a history of radiation therapy to the lesion of interest; (2) the alimentary tract was adjacent to the target lesion (<1 cm distance); (3) they had any other malignancies (excluding carcinoma in situ after curative treatment and cancers that have not recurred for >5 years); and (4) they had severe comorbidities. The patients were followed up and underwent dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 3 months after completing C-ion RT.

Simulation, Planning, and Treatment

Before treatment planning, a fiducial marker as the landmark for tumor location was implanted percutaneously near the tumor under image-guidance. Marker placement was omitted when there was a structure that could be used as a fiducial, such as dense lipiodol deposition, embolic coils, or surgical clips. Simulation and planning were based on respiratory-gated CT. The patients were immobilized using fixation cushions and thermoplastic shells of 3-mm thickness during the simulation CT and treatment. The gross tumor volume was contoured based on the fusion image of respiratory-gated CT and contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. A clinical target volume expansion of 5 mm in all directions was modified to exclude the digestive tract and major branch of the portal vein. The planning target volume (PTV) margin was decided based on the distance of internal movement during the respiratory-gating plus a 3-mm setup margin. The C-ion RT dose is described herein in Gy (relative biological effectiveness [RBE]); it was derived by multiplication of physical dose by the RBE of carbon-ion beams [29].

From June 2010 to January 2014, the initial prescribed dose was 52.8 Gy (RBE) delivered in 4 fractions. From February 2014, the protocol was revised, and the prescribed dose increased up to 60 Gy (RBE) in 4 fractions based on the results of a phase I clinical trial (UMIN-CTR, trial number: 000020344), which was conducted in parallel [22].

Carbon-ion beams were accelerated using a synchrotron at GHMC. The beam energies were 290, 380, and 400 MeV/μ, determined individually for each patient based on tumor depth. Normal tissue constraints were as follows: the liver volume receiving >20 Gy (RBE) (V20), the maximum alimentary tract (including the stomach, duodenum, small bowel, and large bowel) dose, the maximum skin dose, and the maximum portal hepatis (including the first branch of the portal vein and hepatic duct) dose should have been <35%, 42 Gy (RBE), 45 Gy (RBE), and 52.8 Gy (RBE), respectively.

To assess the position of the patient and the target, just before each treatment session, we acquired 2-directional X-ray images and matched the skeletal structure on digitally reconstructed radiography from treatment planning CT images. In case of a deviation of ≥3 mm between the skeletal structure and the fiducial marker, the treatment position was corrected based on the fiducial marker. Carbon-ion beams were delivered during the expiratory phase under the respiratory gating system (AZ-733 V with laser respiration sensor; Anzai Medical, Tokyo, Japan).

Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes

To evaluate the treatment effect of C-ion RT, the primary endpoint was the LC rate at 3 years. The secondary endpoints were the progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and acute and late toxicities. The LC rate was calculated from the initial treatment date of C-ion RT to the date of local recurrence. Local recurrence was defined as radiographic signs, in which the tumor size increased according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1), the appearance of a new early-enhancement area in the irradiated field, or continuous increase of alpha-fetoprotein following treatment without any radiographic disease progression outside the primary site. Definitive diagnosis was obtained by biopsy in case of doubtful radiological findings (i.e., increased early-enhancement without an increase in tumor size and AFP elevation). Recurrence outside the PTV was defined as out-field recurrence, and new appearances were judged to be disease progression. Deaths during the follow-up period without evidence of radiological progression were censored in the analysis of the LC rate. Overall survival was calculated from the initial treatment date of C-ion RT to the date of any-cause death. Patients alive at the end of the follow-up period were censored. PFS was calculated from the initial treatment date of C-ion RT to the date of local treatment failure, disease progression outside of the primary site, or death from any cause. Patients alive and without progression at the end of the follow-up period were censored.

Tumor response was evaluated by both RECISTv1.1 and modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (mRECIST) based on the consensus between radiation oncologists and at least one diagnostic radiologist. According to RECISTv1.1, tumor response was based on the measurement of the sum longest diameter of all lesions observed on contrast-enhanced CT/MRI or noncontrast MRI in patients who are contraindicated with contrast media. According to mRECIST, complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of any enhancement in all lesions; partial response (PR) was defined as at least 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of viable enhanced lesions; progressive disease was defined as an increase of ≥20% of the sum of diameter of viable enhanced lesions; and stable disease (SD) was defined as a tumor response between PR and progressive disease. Overall response was based on the combined assessment of responses for in-field and the appearance of new out-field lesions. Best treatment response of target lesions was defined as the maximum response recorded from the start of C-ion RT until local progression.

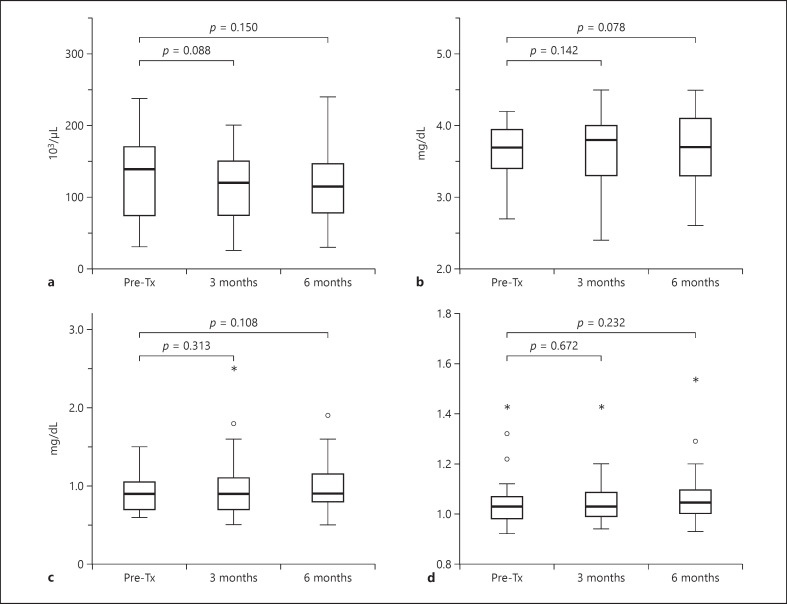

Treatment-related toxicity was evaluated according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. All appearance or exacerbation of symptoms within 90 days was defined as acute treatment-related toxicities. The appearance or exacerbation of symptoms suspected to have a causal relationship with C-ion RT after 91 days during the entire observation period was defined as late treatment-related toxicities. Tumor exacerbations and tumor-related symptoms or additional treatment for recurrent tumors were excluded from late treatment-related toxicities. The investigators checked patients every 3 months for skin changes, digestive and respiratory symptoms, ascites, jaundice, and other newly emerging subjective symptoms. The impact of C-ion RT on liver function was assessed according to the Child-Pugh score, platelet counts, serum albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), and albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score before and at the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits after C-ion RT completion.

Statistical Analysis

The LC, OS, and PFS rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The sample size was estimated to detect an increase in the 3-year LC rate from 50% to 80%, with a 2-sided alpha value of 0.05 and a power of 90% by using the method of Brookmeyer and Crowley. The 50% rate was based on historical data of trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) [30, 31], which is a standard treatment for HCC not amenable to surgery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and based on the previous reports of C-ion RT [24, 26]. The number of cases was estimated to be 29; considering dropout, we aimed to examine a total of 35 cases. If the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval [CI] for the 3-year LC rate of full analysis cases is >50%, the null hypothesis would be rejected, and C-ion RT would be sufficiently effective for further confirmatory trial. Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of the last contact. Patients who were alive on February 1, 2020, were censored for OS analysis. If TACE, or arterial/systemic chemotherapy, which can affect the LC of the C-ion RT, were performed for recurrent lesions outside the irradiation field while the irradiated lesion was under control, these cases were censored in the LC analysis. In univariate analysis, intergroup comparisons were analyzed by the log-rank test. To identify the independent factors associated with the LC and OS rates, a multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model with a backward stepwise procedure; p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All factors with a p value <0.15 on univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis. The Wilcoxon signed-rank and Friedman tests were used to analyze the changes in each laboratory data, Child-Pugh score, and ALBI score. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

In total, 35 patients with HCC were enrolled between October 2010 and May 2016. The patient and tumor characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median follow-up periods of the survivor group (n = 23) and the overall cohort were 55.1 (range, 19.9–97.1) months and 49.0 (range, 4.0–62.4) months, respectively. Based on Makuuchi's criteria of using indocyanine green retention rate test to evaluate liver function and tumor burden, 22 cases were not eligible for radical hepatectomy, including sub-segmentectomy, segmentectomy, lobectomy, or hemi-/extended hepatectomy [32]. Of the 13 patients who met the Makuuchi criteria for radical hepatectomy, 8 patients had poor PS (PS ≥ 1); 3 patients were judged to be resectable, and 5 patients were not amenable to surgery because of multiple comorbidities and/or very old age based on the evaluation by a multidisciplinary board that included experienced hepatobiliary surgeons. Thus, 27 of all 35 patients (77.1%) were not suitable for radical hepatectomy based on Makuuchi's criteria and European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines [32, 33]. Concerning RFA, 33 of 35 patients (94.3%) were judged to be unsuitable because of the tumor size (n = 22), invasive morphology (n = 10), location adjacent to or surrounded by large vessels (n = 17), invisible in ultrasound with contraindication for contrast media (n = 1), and other reasons (n = 5), including bleeding tendency due to low platelet count and/or antiplatelet or coagulant therapy that cannot be interrupted. The indication of RFA was judged by considering multiple factors on the multidisciplinary board that included experienced hepatologists and interventional radiologists.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 35)

| Characteristics | Patients, n (proportion, %) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| <75 | 16 (46) |

| ≥75 | 19 (59) |

| Median [range] | 75 [57–85] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (51) |

| Female | 17 (49) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 24 (68) |

| 1 | 10 (29) |

| 2 | 1 (3) |

| Child-Pugh score/class* | |

| 5/A | 20 (57) |

| 6/A | 9 (26) |

| 7/B | 5 (14) |

| 8/B | 1 (3) |

| ALBI grade | |

| 1 | 9 (26) |

| 2a | 11 (31) |

| 2b | 15 (43) |

| ICG retention rate at 15 min | |

| <10% | 3 (9) |

| 10–19.9% | 11 (31) |

| 20–29.9% | 10 (29) |

| 30–39.9% | 5 (14) |

| ≥40% | 6 (17) |

| Median [range] | 22.8 [2.3–62.2] |

| Viral marker | |

| HBs-Ag(+), HCV-Ab(−) | 2 (6) |

| HBs-Ag(−), HCV-Ab(+) | 27 (78) |

| HBs-Ag(−), HCV-Ab(−) | 6 (16) |

| Maximum tumor diameter, cm | |

| <3 | 13 (37) |

| 3–5 | 14 (40) |

| ≥5 | 8 (23) |

| Median [range] | 3.5 [1.2–7.7] |

| Tumors, n | |

| Solitary | 34 (97) |

| Multiple | 1 (3) |

| Serum AFP level, ng/mL | |

| <50 | 26 (74) |

| ≥50 | 9 (26) |

| Median [range] | 11.3 [1.6–21,147.8] |

| Previous treatment | |

| Naïve | 20 (57) |

| Recurrent | 15 (43) |

| Treatment protocols | |

| 52.8 Gy (RBE)/4 fractions | 17 (49) |

| 60.0 Gy (RBE)/4 fractions | 18 (51) |

CI, confidence interval; HBs-Ag, Hepatitis B Antigen; HCV-Ab, Hepatitis C virus antibody; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Classification; RBE, relative biological effectiveness.

One patient was unclassifiable because of anticoagulant therapy.

LC, PFC, and OS Rates

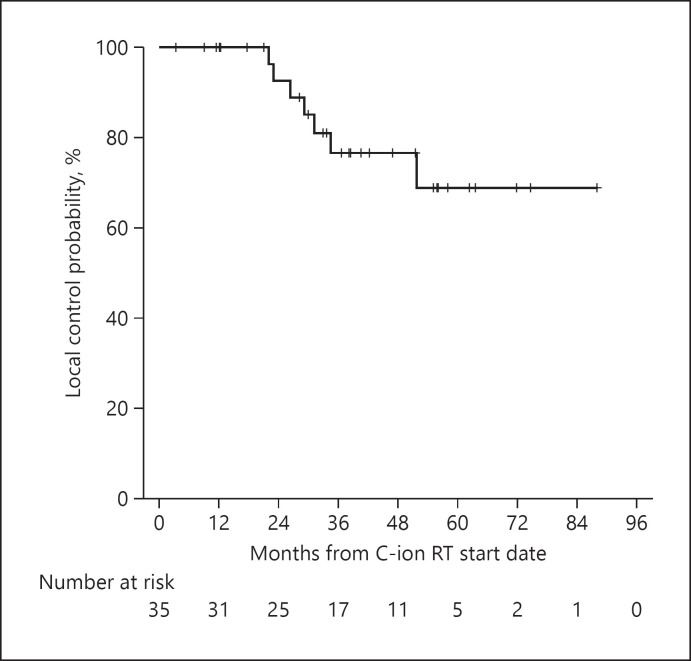

The 2-, 3-, and 4-year LC rates were 92.6% (95% CI, 82.8–100%), 76.5% (95% CI, 59.8–93.2%), and 76.5% (95% CI, 59.8–93.2%), respectively (Fig. 1). Local recurrence was observed in 7 patients (20.0%) during the entire follow-up period; 6 patients had central recurrence at the sites of irradiated tumors, and 1 patient had marginal recurrence around the margin of irradiated tumor. Local recurrences were diagnosed by biopsy in 3 patients, in which the judgment of recurrence by radiological findings was questionable and by radiological findings in 4 patients. In total, 12 cases were censored for LC within 3 years because of death from HCC (without progression in the irradiated field) of 4 patients, death from other diseases (cerebral hemorrhage, colorectal cancer, myocardial infarction, and unknown cause-related progressive Parkinsonism) of 4 patients, slight shortage of the observation days when the data were fixed for 2 patients, TACE to the recurrent lesion outside the irradiated field without local recurrence for 1 patient, and follow-up loss for 1 patient.

Fig. 1.

LC rates of the overall cohort. LC, local control.

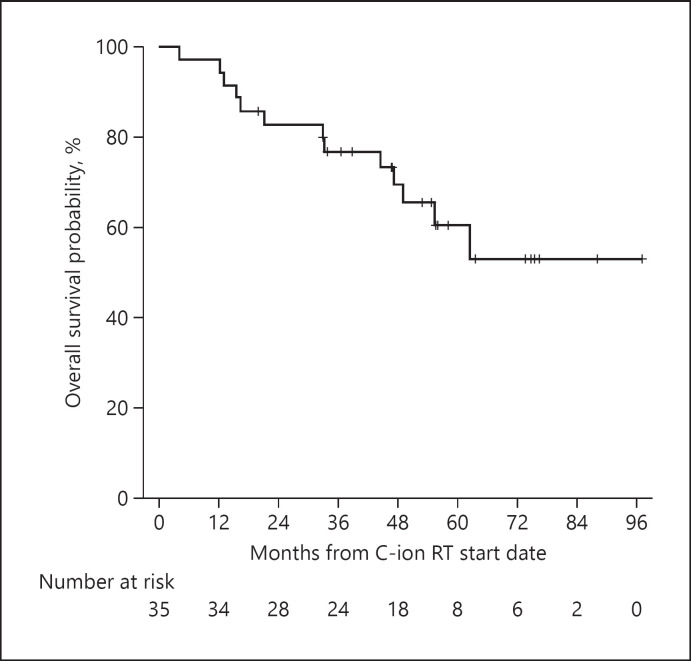

The OS rates are presented in Figure 2. The 2-, 3-, and 4-year OS rates were 82.8% (95% CI, 70.0–95.4%), 76.7% (95% CI, 62.6–90.8%), and 69.4% (95% CI, 53.3–85.4%), respectively. There were 13 patients (37.1%) who died during the follow-up period; among them, 9 patients died of disease progression, while 4 patients died of other diseases except liver disease.

Fig. 2.

OS rates of the overall cohort. OS, overall survival.

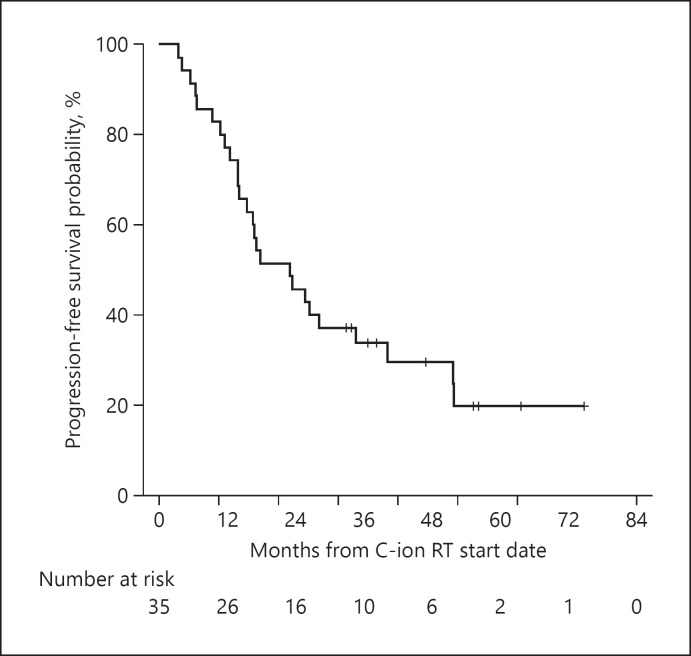

The 2- and 3-, 4-year PFS rates were 45.7% (95% CI, 29.2–62.2%), 33.8% (95% CI, 17.9–49.7%), and 29.5% (95% CI, 13.6–45.4%), respectively (Fig. 3). The median time-to-progression was 25.6 months (95% CI, 13.7–37.5). Overall, 23 patients (65.7%) experienced recurrence. Regarding the initial recurrence sites, 4 (11.4%) patients had local recurrence while 19 (54.2%) patients had intrahepatic recurrence outside the PTV (solitary lesion and multiple lesions in 8 and 11 patients, respectively), including 1 patient with distant metastasis. The treatment modalities used for initial recurrence were TACE, RFA with or without TACE, C-ion RT, SBRT, and combination of C-ion RT for local recurrence and resection for lung metastasis in 15, 3, 3, 1, and 1 patient, respectively. At the end of the follow-up period, disease-free survival had been accomplished in 6 of 23 recurrent patients with multidisciplinary treatment to recurrent lesions. The minimum and median times to local recurrence were both 22 months. There was no significant difference between the presence and absence of local recurrence in survival (p = 0.950). The median survival time was 62.4 months (95% CI, 42.6–82.2) for patients who experienced out-field recurrence, and not reached for those who did not. There was no significant difference in survival with or without out-field recurrence (p = 0.362).

Fig. 3.

PFS rates of the overall cohort. PFS, progression-free survival.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of univariate and multivariate analyses for OS and LC, respectively. In the univariate analysis, Child-Pugh class and modified-ALBI (mALBI) grade showed statistical significance for OS, and previous treatment for LC and total radiation dose for OS, which showed borderline significance. The maximum tumor diameter was not a significant prognostic factor in the univariate analysis for LC and OS. To eliminate multicollinearity, the Child-Pugh class and the mALBI grade were separately put into the Cox proportional regression model. A multivariate analysis revealed that the mALBI grade was the only independent significant prognostic factor for OS. In another trial of multivariate analysis where the mALBI grade was replaced by the Child-Pugh class, Child-Pugh class B was the independent poor prognostic factor for OS (hazard ratio, 3.95; 95% CI, 1.32–11.7; p = 0.014).

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of LC and OS

| Variables | n | 2-yr LC | p value | 2-yr OS | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||||

| <75 | 16 | 84.5 | 0.193 | 93.3 | 0.777 |

| ≥75 | 19 | 100 | 73.7 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 18 | 100 | 0.829 | 77.4 | 0.986 |

| Female | 17 | 86.7 | 88.2 | ||

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0 | 24 | 95.0 | 0.752 | 87.5 | 0.313 |

| 1–2 | 11 | 85.7 | 72.7 | ||

| Child-Pugh class | |||||

| A | 28 | 100 | 0.023* | 85.7 | 0.005* |

| B | 6 | 66.7 | 66.7 | ||

| mALBI grade | |||||

| 1–2a | 20 | 100 | 0.055* | 95.0 | <0.001 * |

| 2b | 15 | 89.5 | 66.7 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter, cm | |||||

| <5 | 27 | 95.5 | 0.754 | 85.2 | 0.706 |

| ≥5 | 8 | 80.0 | 72.9 | ||

| Serum AFP level, ng/mL | |||||

| <50 | 26 | 90.0 | 0.430 | 84.4 | 0.767 |

| ≥50 | 9 | 100 | 77.8 | ||

| Previous treatment | |||||

| Naïve | 20 | 87.5 | 0.115* | 90.0 | 0.263 |

| Recurrent | 15 | 100 | 73.3 | ||

| Total dose | |||||

| 52.8 Gy (RBE)/4 fractions | 17 | 84.6 | 0.590 | 76.5 | 0.099* |

| 60.0 Gy (RBE)/4 fractions | 18 | 100 | 88.9 |

The table shows results of univariate analysis of LC and OS analyzed by clinical characteristics. 2-yr LC, 2-year local control rate; 2-yr OS, 2-year overall survival rate; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; mALBI grade, modified albumin-bilirubin grade; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; RBE, relative biological effectiveness; LC, local control; OS, overall survival.

Included into multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors

| Variables | Multivariate for LC rate |

Multivariate for OS rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| mALBI grade (2b vs. 1–2a) | 5.88 | 1.18–29.4 | 0.031* | 21.50 | 2.79–165.95 | 0.003* |

| Previous treatment (naïve vs. recurrent) | 7.16 | 0.79–65.0 | 0.081 | − | − | − |

| Total dose (52.8 vs. 60.0 Gy [RBE]) | − | −q | − | 0.95 | 0.792–1.144 | 0.596 |

The table shows results of multivariate analysis of risk factors related to LC and OS. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; mALBI grade, modified albumin-bilirubin grade; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; RBE, relative biological effectiveness; LC, local control; OS, overall survival.

p values <0.05.

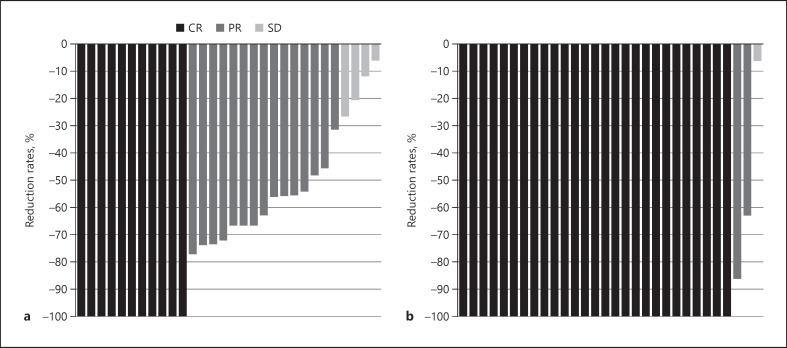

Objective Response Rates of Target and Overall Lesions

The responses of target (in-field) lesions and overall responses are presented in Table 4. The in-field CR, PR, and SD rates at 6 months after C-ion RT were 6.1%, 66.6%, and 27.3%, respectively, according to the RECIST criteria, and 50.0%, 38.5%, and 11.5%, respectively, according to the mRECIST criteria. At 12 months after C-ion RT, the in-field and overall CR rates were 22.6% and 19.4%, respectively, according to the RECIST criteria and 82.1% and 71.4%, respectively, according to the mRECIST criteria. The best treatment response of target lesions among patients who were assessed by both RECIST and mRECIST for at least 6 months is presented in Figure 4. Five patients were not evaluated by mRECIST because of contraindication of contrast media, such as history of severe allergic reaction (n = 2), renal insufficiency (n = 2), and death from myocardial infarction (n = 1). Interestingly, 27 (90.0%) and 11 (36.7%) patients achieved CR after undergoing evaluation using the mRECIST and RECIST criteria.

Table 4.

A continuum of treatment responses to C-ion RT evaluated by RECIST and mRECIST criteria

| Criteria evaluation time after C-ion RT | RECIST 3 m (n = 34) | 6 m (n = 33) | 12 m (n = 31) | mRECIST 3 m (n = 32) | 6 m (n = 26) | 12 m (n = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-field CR rates, % (n) | 2.9 (1) | 6.1 (2) | 22.6 (7) | 21.9 (7) | 50.0 (13) | 82.1 (23) |

| In-field ORR, % (n) | 44.1 (15)- | 72.7 (24) | 77.4 (24) | 59.6 (19)- | 88.5 (23) | 96.4 (27) |

| In-field DCR, % (n) | 100 (34) | 100 (33) | 100 (31) | 100 (32) | 100 (26) | 100 (28) |

| Overall CR rates, % (n) | 2.9 (1) | 6.1 (2) | 19.4 (6) | 21.9 (7) | 38.5 (10) | 71.4 (20) |

| Overall ORR, % (n) | 44.1 (15)- | 69.7 (23) | 67.7 (21) | 59.6 (19)- | 80.8 (21) | 85.7 (24) |

| Overall DCR, % (n) | 100 (34) | 93.9 (31) | 87.1 (27) | 100 (32) | 92.3 (24) | 89.3 (25) |

RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; mRECIST, modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; CR, complete response; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; C-ion RT, carbon-ion radiotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Waterfall plots demonstrating the best treatment response of the target lesions among patients (n = 30) who assessed by both RECIST (a) and mRECIST (b) for at least 6 months. RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; mRECIST, modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors.

Acute and Late Toxicities of Carbon-Ion RT

All patients completed the treatment course without interruption. All nonhematological toxicities during the follow-up period are presented in Table 5. Within 90 days after C-ion RT, acute toxicities, including skin erythema, fatigue, pneumonitis, and pleural effusion, were transient and easily manageable. Except for 1 patient who experienced grade 2 ascites, grade ≥2 severe acute toxicity was not observed within 90 days. Apart from transient changes in laboratory test values, 4 (11.4%) of the 35 patients experienced grade 2 or 3 rate toxicities, grade 2 ascites, grade 3 hepatic encephalopathy, and grade 3 acute cholecystitis. No patient developed grade 4 or 5 toxicities.

Table 5.

Acute and late toxicity of C-ion RT

| Toxicities | Acute (within 3 months) | Late (after 3 months) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 0/1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0/1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Skin/chest wall | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ascites | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis/pleuritis | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatobiliary | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Laboratory investigation | 33 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 3* | 0 | 0 |

| Elevation of AST | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Elevation of ALT | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

The table shows the nonhematological toxicity profile of carbon-ion radiation therapy, with details of grade, location, and onset period. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; C-ion RT, carbon-ion radiotherapy.

One patient experienced both AST and ALT elevation.

Impact of Carbon-Ion RT on Liver Function

There was no significant difference in the Child-Pugh score assessed before and at 3- and 6-month follow-up visits after the completion of C-ion RT (p = 0.19, Friedman test). In total, 4 (11.4%) of the 35 patients and 2 (6.0%) of the 33 patients had worse Child-Pugh scores at 3 and 6 months, respectively. The Child-Pugh score of 1 patient increased by 3 points at 6 months after C-ion RT. This patient also experienced progressive multiple intrahepatic metastases.

The changes in laboratory values related to liver function before and after C-ion RT are presented in Figure 5. The median baseline values of platelet counts, serum albumin, total bilirubin, and PT-INR were 140 (range, 31–238) × 103/μL, 3.7 (range, 2.7–4.2) mg/dL, 0.9 (range, 0.6–1.5) mg/dL, and 1.03 (range, 0.92–1.43), respectively. There were no significant differences in platelet counts, serum albumin, bilirubin, and PT-INR between before treatment and at the 3- or 6-month period after C-ion RT. The median ALBI scores before C-ion RT at 3 and 6 months after C-ion RT were −2.36 (range, −2.82 to −1.51), −2.48 (range, −3.08 to −1.17), and −2.39 (range, −2.96 to −1.32), respectively. There was no significant decrease in the ALBI score before and after C-ion RT (p = 0.31, Friedman test).

Fig. 5.

Impact of C-ion RT on liver function as assessed using the following laboratory parameters. Platelet count (a); serum albumin (b); serum bilirubin (c); PT-INR (d). PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; RT, radiotherapy. C-ion RT, carbon-ion radiotherapy.

Discussion/Conclusion

Prospective evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of C-ion RT for HCC is still lacking to date. This study confirmed that short-course C-ion RT using 4 fractions is a safe treatment with a high LC rate for HCC in the prospective setting. Further, our data showed that C-ion RT had minimal adverse impact on liver function. Although the study population was relatively small, the sample size was statistically designed with the goal of becoming a rational for randomized controlled trial comparing C-ion RT with standard therapies in patients with HCC not amenable to surgery and RFA. To our knowledge, no previous studies designed for same purpose have been reported.

C-ion RT for HCC was initiated in 1995 at the Hospital of the National Institute of Radiological Sciences (NIRS) in Japan, and the results of the first prospective study were reported by Kato et al. [26]. Kasuya et al. [25] recently analyzed data from 2 prospective trials that used 12, 8, or 4 fractions C-ion RT at NIRS and reported promising outcomes. The 3-year LC and OS rates were 91.4% and 50%, respectively [25]. In these studies, equivalent doses in 2 Gy fractions (α/β = 10 Gy) ranged from 65.3 to 102.1 Gy, which were less than or equivalent to those of this study (102.1–125.0 Gy). Shibuya et al. [9] reported the results of hypofractionated C-ion RT for HCC in a multicenter retrospective setting. The 3-year LC and OS rates were 81.0% and 73.3%, respectively [9]. The outcomes related to effectiveness, such as LC and OS rates in this study, were consistent with these previous studies. The treatment response could not be sufficiently confirmed on the follow-up images for both RECIST and mRECIST as early as 3 months after C-ion RT, and it was considered that it would take at least 6 months to determine the objective response. In RECIST, most cases did not develop CR even after 12 months. Conversely, in mRECIST, the in-field CR and ORR rates at 12 months were 82.1% and 96.4%, respectively, and CR was achieved in 90% of cases within the entire observation period. Two of the 3 patients whose best response was PR on the mRECIST criteria showed no local recurrence at the 52- and 88-month follow-up. One patient was not evaluated with contrast medium after 12 months due to poor renal function. In the other patient with PR, a tiny early-enhancement in the irradiation field was observed; it did not increase in size for 88 months. In 1 patient whose best response was SD, local recurrence was confirmed by biopsy, which was performed based on a slightly increased contrast enhancement and tumor size 22 months after C-ion RT. Two patients with PR had survived at the end of the follow-up periods, and 1 patient who experienced local recurrence died due to HCC progression 55 months after C-ion RT. These findings are consistent with the high LC rate of C-ion RT. Understanding this delayed response appeared to be important for avoiding excessive treatment and managing HCC appropriately.

The indication of conventional radiation therapy for HCC has traditionally been limited by inadequate dose to the tumor because it compromises the surrounding liver tissues. Given that the majority of these patients have an underlying chronic liver disease that weakens resistance to radiation, more precise radiation delivery techniques are essential to preserve posttreatment liver function. Based on these considerations, high-precision radiation therapy, such as SBRT, PBT, and C-ion RT, is increasingly used for HCC. Some prospective and observational studies also showed that X-ray-based ablative radiotherapy using the SBRT technique for HCC achieves good local tumor control, with 71.4–97.0% local tumor control rates at 2 or 3 years [12, 34, 35]. Although SBRT is not listed as a recommended treatment for HCCs in major guidelines, recent evidence shows that SBRT provides equal or better LC rates than RFA, which is one of the established first-line treatments for small-sized HCC [36]. Meanwhile, SBRT for large tumors is usually challenging because of the damage to the normal liver tissues. In the review of 5 prospective studies on SBRT published at this time, the 2- and 3-year OS rates were reported to be 69–96% and 67–78%, respectively, and the maximum tumor diameter ranged from 1.3 to 2.8 cm (weighted mean value by the number of cases, 2.2 cm) [35, 37, 38, 39, 40]. The OS rates in our study were almost equivalent to the best reported outcome among these studies; nevertheless, the tumor size (median, 3.5 cm) was obviously larger. Even with a long-term follow-up duration >3 years, there was a slight decrease in OS. Although almost half of recurrent patients had multiple lesions as initial recurrence and majority of patients were treated by TACE, median survival time for patients who experienced out-field recurrence was relatively long (62.4 months). The unique property of C-ion RT is the steep dose distribution, and it is thought that the small impact on hepatic function may lead to good survival rates without interfering with additional liver-oriented treatment to out-field recurrence.

Charged particle therapy, including PBT and C-ion RT, has superior dose distribution than X-ray-based radiotherapy. This physical property can reduce the irradiated dose to the normal liver parenchyma; thus, charged particle therapy can be applied to larger lesions than SBRT. Previous studies of PBT and C-ion RT in patients with HCC have shown promising LC rates and minimal toxicity [7]. However, the treatment duration for PBT is generally longer than that for C-ion RT in previous reports (i.e., 10–35 fractions). To our knowledge, the concept of ablative radiotherapy using 4 or less fractionated schedules of <10 fractions has not been applied to PBT.

Here, the 2- and 3-year OS rates were 82.8% and 76.7%, respectively. These results are encouraging considering that our study population included a high percentage of patients not eligible for surgery because of risk factors related to poor prognosis, such as old age, poor liver function, and impaired PS. In a recent Japanese nationwide survey, the 3-year OS rate for hepatectomy, which is the first-line treatment for localized HCC, was 75.3%; meanwhile, RFA, another curative treatment option for small-sized HCC, had a 3-year OS rate of 75.0% [41]. Despite our study including patients not eligible for surgery or RFA, the outcomes were comparable to those in curative treatments. Considering its minimally invasive nature, C-ion RT may be a beneficial alternative modality to hepatectomy or RFA.

Here, the multivariate analysis revealed that mALBI grade 2a or better was a significant prognostic factor for OS. Although many reports have highlighted the usefulness of ALBI/mALBI grade for the prognosis of HCC, no report mentioned the impact of ALBI/mALBI grade on the outcomes after charged-particle therapies. This result was consistent with the findings of previous reports, which showed that the Child-Pugh score was a prognostic factor after charged-particle therapies [25, 42]. As the mALBI grade components do not include subjective variables, such as ascites and encephalopathy contrary to the Child-Pugh score, the mALBI grade may provide more objective evaluation of liver function reserve before charged-particle therapies. No other clinical factors, including age, ECOG-PS, maximum tumor diameter, and the presence or absence of previous treatment, influenced LC or OS. Although no definitive conclusion could be drawn because of the small sample size, C-ion RT can be applied to patients with fragility and recurrent or large tumors. The outcomes of the patients treated with 60 Gy (EBE) appeared slightly better at 2 years after C-ion RT; however, no statistically significant difference was observed. The impact of these factors on outcomes should be verified in larger studies.

Except for 1 patient who experienced ascites controllable with diuretics, no grade 2 or greater treatment-related toxicities occurred in the acute phase. Unlike other treatments for HCC, such as surgery, RFA, or TACE, there were no adverse events that required intervention in the acute phase after C-ion RT. The minimally invasive nature of C-ion RT may help maintain the patients' quality of life and social life. Grade 2 or higher ascites and hepatobiliary complications were observed in 3 patients in the late phase, which was considered acceptable considering the background of these patients (elderly, etiology, pretreatment liver function). From a clinical standpoint, it is an important result that the minimal impact on liver function of C-ion RT was objectively proven in a prospective study. In this study, no apparent deterioration of liver function was observed after C-ion RT, as assessed based on laboratory data, including the platelet count, serum albumin, total bilirubin, PT-INR, and ALBI score, as well as on hepatobiliary adverse events and the Child-Pugh classification. As HCC commonly requires repeated treatment, it is essential to select a curative treatment with minimal adverse impact on liver function. Although this study included patients with relatively larger tumors compared to previous reports in SBRT, the results may be plausible because C-ion RT was clearly superior to X-ray-based radiotherapy concerning dose distribution to the normal liver tissues.

Although the 3-year LC rate as the primary endpoint was slightly below the expected value, the lower limit of 95% CI exceeded the threshold value, and the 2-year LC rate in this study was favorable at 92.6%. The most important clinical advantage of C-ion RT is its effectiveness even in cases where resection and RFA are difficult to apply and can accomplish good LC. C-ion RT can also apply to tumors that are refractory or not amenable to TACE. Furthermore, this study showed better PFS rates compared to those of previous studies of TACE for a similar population, probably because of the good LC rate [6, 43].

The most common recurrence pattern after C-ion RT is out-field intrahepatic recurrence. Regarding RFA, Ng et al. [44] reported that 70.8% and 14.5% of patients experienced intrahepatic recurrence and local recurrence at RFA sites during the follow-up period (median, 26 months), respectively. Okuwaki et al. [45] also described that intrahepatic distant recurrence was observed in 48.9% of patients after RFA for small single HCC (median maximum tumor diameter, 2.0 cm) during the 19.6-month median follow-up period. Yoon et al. [40] reported that intrahepatic recurrence was the main cause of failure (33 of 50 patients) after SBRT during the 47.8-month median follow-up period. In these previous studies, the most frequent recurrence pattern after local therapies was intrahepatic distant recurrence, similar to that of this study, which was probably because of the similar, less invasive treatment characteristics of RFA, SBRT, and C-ion RT. The cumulative recurrence rates after RFA for 2-3-cm HCC were reported to be 53.5% and 66.8% for 2 and 3 years, respectively [46]. The 2- and 3-year PFS after SBRT for small-sized HCC (median tumor size, 1.3–2.4 cm) were reported to be 48–59% and 36–52% in recent prospective trials, respectively [37, 38, 39]. Although the tumor size after C-ion RT was larger than those of these previous studies and our sample included patients not amenable to RFA or SBRT, the outcomes; the median TTP was 25.6 months, and the 2- and 3-year PFS rates were 45.7% and 33.8%, respectively, were comparable to those of RFA and SBRT. Given the cost-effectiveness and accessibility of the facilities, C-ion RT should be considered for populations with relatively large tumors for which the safety and efficacy of RFA and SBRT have not been established.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the primary endpoint of this study was the LC rate, which is not a hard endpoint and has the disadvantage of being less objective than the OS rate. However, as C-ion RT is mainly indicated for patients who are difficult or refractory to other local therapies, it includes patients from various backgrounds with many complications, and it is considered difficult to make comparisons based on the OS rate. Thus, the LC rate is set as the primary endpoint in this study protocol to evaluate the treatment effect of C-ion RT. While LC is a simple endpoint defined by one type of event, censoring can affect the robustness of the results. Here, patients' deaths were the main cause of censoring for 3 years, for which local recurrence had not been observed. Censoring because of the additional treatment for recurrent lesions outside of the irradiation field without local recurrence also occurred in some cases, especially after 3 years. As there was only 1 case of censoring because of follow-up loss within 3 years, it was unlikely to affect the considerable impact on the conclusions of this work; however, the long-term result of LC may not be robust. Future confirmatory studies should evaluate the outcomes in a shorter period to reduce the impact of censoring or have robust endpoints, such as the PFS or OS rate. More favorable LC rates have been reported in some studies for SBRT and charged particle therapies. However, the target lesions in most SBRT studies were relatively small, usually <3 cm, and there were few prospective studies with sufficient follow-up periods for PBT and C-ion RT. In this study, there were short-term censors for OS, and it may be meaningful to confirm a favorable survival rate under a prospective trial with a relatively long-term observation period. Second, because the Japanese public healthcare insurance system does not currently cover C-ion RT, there might be a potential selection bias that may have affected the prognosis based on the socio-economic status (i.e., economic bias). This bias should be considered when comparing our results to historical data pertaining to other treatment modalities that are more economically affordable. Third, we could not evaluate the safety of C-ion RT for lesions adjacent to the alimentary tract because these patients were not included in this study, according to the exclusion criteria. The biological effects of carbon-ion beams differ from those of X-rays, and the adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract were not established at the beginning of this study. Thus, lesions close to the digestive tract were excluded from this study and had been planned to be evaluated in another trial (UMIN-CTR trial number: 000020436, http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm). Further studies are required to determine the optimal dose and fractionation schedule of C-ion RT for gastrointestinal adjacent lesions.

In conclusion, 4-fractionated C-ion RT is safe and effective for the treatment of HCC. Compared to the reported outcomes of RFA and SBRT, there were no apparent differences in the recurrence pattern in the study population with relatively large lesions for which these local therapies were difficult to adapt. C-ion RT is less invasive, and thus has minimal adverse effects on liver function, as confirmed using laboratory test findings, the Child-Pugh score, and the ALBI score.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the local institutional review board (approval No. 722) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all its amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the initiation of any protocol examination and procedures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The work received no external sources of funding.

Author Contributions

The followings are the authors' contribution to this study: study concept and design: K. Shibuya, Y. Koyama, T. Ohno, and S. Kakizaki; acquisition of data: K. Shibuya, Y. Koyama, H. Katoh, S. Shiba, S. Okazaki, and M. Okamoto; analysis and interpretation of data: K. Shibuya, H. Katoh, S. Kakizaki, K. Araki, and T. Ohno; drafting of the manuscript: K. Shibuya; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: K. Shibuya; statistical analysis: K. Shibuya and T. Ohno; and study supervision: K. Shirabe and T. Ohno. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. Based on the consent of the research participants, an additional ethical review may be required depending on the purpose of use.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Mar;65((2)):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, et al. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Dec;3((12)):1683–91. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulier S, Ni Y, Jamart J, Ruers T, Marchal G, Michel L. Local recurrence after hepatic radiofrequency coagulation: multivariate meta-analysis and review of contributing factors. Ann Surg. 2005 Aug;242((2)):158–71. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171032.99149.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam VW, Ng KK, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Yuen J, Tung H, et al. Risk factors and prognostic factors of local recurrence after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 Jul;207((1)):20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orcutt ST, Anaya DA. Liver resection and surgical strategies for management of primary liver cancer. Cancer Control. 2018 Jan–Mar;25((1)):1073274817744621. doi: 10.1177/1073274817744621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush DA, Smith JC, Slater JD, Volk ML, Reeves ME, Cheng J, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing proton beam radiation therapy with transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of an interim analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016 May;95((1)):477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igaki H, Mizumoto M, Okumura T, Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Sakurai H. A systematic review of publications on charged particle therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jun;23((3)):423–33. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajyaguru DJ, Borgert AJ, Smith AL, Thomes RM, Conway PD, Halfdanarson TR, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized hepatocellular carcinoma in nonsurgically managed patients: analysis of the national cancer database. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Feb;36((6)):600–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibuya K, Ohno T, Terashima K, Toyama S, Yasuda S, Tsuji H, et al. Short-course carbon-ion radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Liver Int. 2018 Dec;38((12)):2239–47. doi: 10.1111/liv.13969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim N, Cheng J, Jung I, Liang J, Shih YL, Huang WY, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy vs. radiofrequency ablation in Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020 Jul;73((1)):121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda Y, Kimura T, Aikata H, Kobayashi T, Fukuhara T, Masaki K, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Mar;28((3)):530–6. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura T, Aikata H, Takahashi S, Takahashi I, Nishibuchi I, Doi Y, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma ineligible for resection or ablation therapies. Hepatol Res. 2015 Apr;45((4)):378–86. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng ZC, Seong J, Yoon SM, Cheng JC, Lam KO, Lee AS, et al. Consensus on stereotactic body radiation therapy for small-sized hepatocellular carcinoma at the 7th Asia-Pacific primary liver cancer expert meeting. Liver Cancer. 2017 Nov;6((4)):264–74. doi: 10.1159/000475768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe T, Saitoh J, Kobayashi D, Shibuya K, Koyama Y, Shimada H, et al. Dosimetric comparison of carbon ion radiotherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy with photon beams for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:187. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toramatsu C, Katoh N, Shimizu S, Nihongi H, Matsuura T, Takao S, et al. What is the appropriate size criterion for proton radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma? A dosimetric comparison of spot-scanning proton therapy versus intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2013 Mar;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando K, Kase Y. Biological characteristics of carbon-ion therapy. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009 Sep;85((9)):715–28. doi: 10.1080/09553000903072470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui X, Oonishi K, Tsujii H, Yasuda T, Matsumoto Y, Furusawa Y, et al. Effects of carbon ion beam on putative colon cancer stem cells and its comparison with X-rays. Cancer Res. 2011 May;71((10)):3676–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhl M, Herfarth K, Debus J. Comparing the use of protons and carbon ions for treatment. Cancer J. 2014 Nov–Dec;20((6)):433–9. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorin Y, Ikeda K, Kawamura Y, Fujiyama S, Kobayashi M, Hosaka T, et al. Effectiveness of particle radiotherapy in various stages of hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study. Liver Cancer. 2018 Oct;7((4)):323–34. doi: 10.1159/000487311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spychalski P, Kobiela J, Antoszewska M, Błażyńska-Spychalska A, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Høyer M. Patient specific outcomes of charged particle therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and quantitative analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2019 Mar;132:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imada H, Kato H, Yasuda S, Yamada S, Yanagi T, Kishimoto R, et al. Comparison of efficacy and toxicity of short-course carbon ion radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma depending on their proximity to the porta hepatis. Radiother Oncol. 2010 Aug;96((2)):231–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibuya K, Ohno T, Katoh H, Okamoto M, Shiba S, Koyama Y, et al. A feasibility study of high-dose hypofractionated carbon ion radiation therapy using four fractions for localized hepatocellular carcinoma measuring 3 cm or larger. Radiother Oncol. 2019 Mar;132:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda S, Kato H, Imada H, Isozaki Y, Kasuya G, Makishima H, et al. Long-term results of high-dose 2-fraction carbon ion radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Mar–Apr;5((2)):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsu S, Fukumoto T, Demizu Y, Miyawaki D, Terashima K, Sasaki R, et al. Clinical results and risk factors of proton and carbon ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2011 Nov;117((21)):4890–904. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasuya G, Kato H, Yasuda S, Tsuji H, Yamada S, Haruyama Y, et al. Progressive hypofractionated carbon-ion radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: combined analyses of 2 prospective trials. Cancer. 2017 Oct;123((20)):3955–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato H, Tsujii H, Miyamoto T, Mizoe JE, Kamada T, Tsuji H, et al. Results of the first prospective study of carbon ion radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with liver cirrhosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004 Aug;59((5)):1468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno T, Kanai T, Yamada S, Yusa K, Tashiro M, Shimada H, et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy at the Gunma University Heavy Ion Medical Center: new facility set-up. Cancers. 2011;3((4)):4046–60. doi: 10.3390/cancers3044046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, Matsui O, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: consensus-based clinical practice guidelines proposed by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) 2010 updated version. Dig Dis. 2011;29((3)):339–64. doi: 10.1159/000327577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanai T, Endo M, Minohara S, Miyahara N, Koyama-ito H, Tomura H, et al. Biophysical characteristics of HIMAC clinical irradiation system for heavy-ion radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 Apr;44((1)):201–10. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyayama S, Matsui O, Yamashiro M, Ryu Y, Kaito K, Ozaki K, et al. Ultraselective transcatheter arterial chemoembolization with a 2-f tip microcatheter for small hepatocellular carcinomas: relationship between local tumor recurrence and visualization of the portal vein with iodized oil. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007 Mar;18((3)):365–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, Pilleul F, Denys A, Watkinson A, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010 Feb;33((1)):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makuuchi M, Kosuge T, Takayama T, Yamazaki S, Kakazu T, Miyagawa S, et al. Surgery for small liver cancers. Semin Surg Oncol. 1993 Jul–Aug;9((4)):298–304. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980090404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018 Jul;69((1)):182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang WI, Kim MS, Bae SH, Cho CK, Yoo HJ, Seo YS, et al. High-dose stereotactic body radiotherapy correlates increased local control and overall survival in patients with inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:250. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda A, Sanuki N, Tsurugai Y, Iwabuchi S, Matsunaga K, Ebinuma H, et al. Phase 2 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and optional transarterial chemoembolization for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to resection and radiofrequency ablation. Cancer. 2016 Jul;122((13)):2041–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim N, Cheng J, Jung I, Liang J, Shih YL, Huang WY, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy vs. radiofrequency ablation in Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020 Jul;73((1)):121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durand-Labrunie J, Baumann AS, Ayav A, Laurent V, Boleslawski E, Cattan S, et al. Curative irradiation treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter phase 2 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020 May 1;107((1)):116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang WI, Bae SH, Kim MS, Han CJ, Park SC, Kim SB, et al. A phase 2 multicenter study of stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: safety and efficacy. Cancer. 2020 Jan;126((2)):363–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimura T, Takeda A, Sanuki N, Ariyoshi K, Yamaguchi T, Imagumbai T, et al. Multicenter prospective study of stereotactic body radiotherapy for previously untreated solitary primary hepatocellular carcinoma: the STRSPH study. Hepatol Res. 2021 Apr;51((4)):461–71. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon SM, Kim SY, Lim YS, Kim KM, Shim JH, Lee D, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for small (≤5 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to curative treatment: results of a single-arm, phase II clinical trial. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020 Oct;26((4)):506–15. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2020.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kudo M, Izumi N, Kubo S, Kokudo N, Sakamoto M, Shiina S, et al. Report of the 20th Nationwide follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2020 Jan;50((1)):15–46. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizumoto M, Okumura T, Hashimoto T, Fukuda K, Oshiro Y, Fukumitsu N, et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison of three treatment protocols. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Nov;81((4)):1039–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiba S, Shibuya K, Katoh H, Kaminuma T, Miyazaki M, Kakizaki S, et al. A comparison of carbon ion radiotherapy and transarterial chemoembolization treatment outcomes for single hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. Radiat Oncol. 2019 Aug;14((1)):137. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1347-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng KK, Poon RT, Lo CM, Yuen J, Tso WK, Fan ST. Analysis of recurrence pattern and its influence on survival outcome after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 Jan;12((1)):183–91. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okuwaki Y, Nakazawa T, Shibuya A, Ono K, Hidaka H, Watanabe M, et al. Intrahepatic distant recurrence after radiofrequency ablation for a single small hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors and patterns. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43((1)):71–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tateishi R, Shiina S, Yoshida H, Teratani T, Obi S, Yamashiki N, et al. Prediction of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative ablation using three tumor markers. Hepatology. 2006 Dec;44((6)):1518–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. Based on the consent of the research participants, an additional ethical review may be required depending on the purpose of use.